Aperture's Blog, page 104

March 1, 2018

Black is Brilliant

From Accra to Harlem, the photographs in an exhibition curated by David Hartt expand the field of representation.

By Oluremi C. Onabanjo

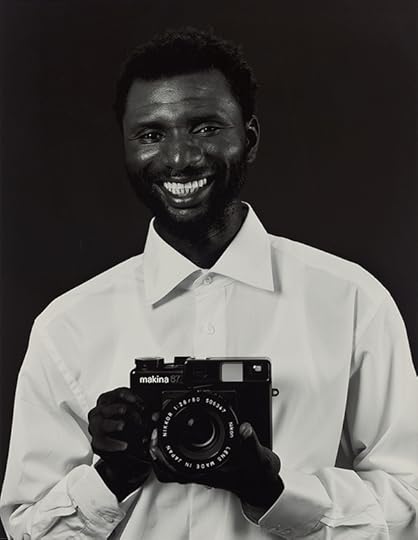

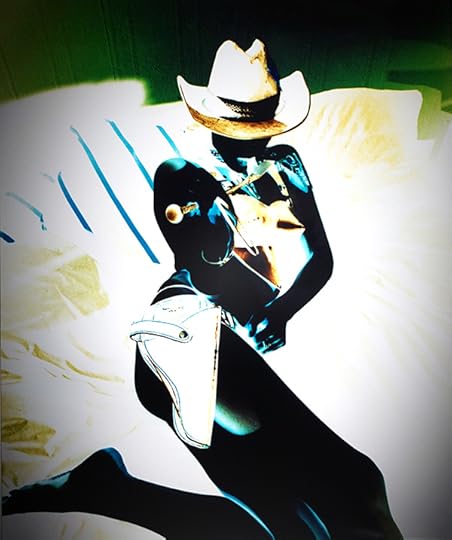

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1964

© the artist, courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

What are the images that encapsulate the moments, spaces, communities, and myriad experiences of blackness across the globe? What are the gestures, the glances, the ways of being that illustrate “a crisis of borders, a fold in time, a rupture in space. An assertion of gradience”?

This Synthetic Moment, a group exhibition curated by Canadian artist David Hartt, currently on view at David Nolan Gallery in New York, grapples with such questions, deftly incorporating the work of Russian Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur, Ghanaian photographer James Barnor, and American photographers Kwame Brathwaite, Zoe Leonard, and Christopher Williams alongside Hartt’s own work. A polyphonic, essayistic installation, the exhibition crisscrosses varied geographies and temporalities, highlighting visions of beauty and style alongside quotidian, melancholic scenes. Spanning six decades, and locations from Accra to Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, London to New York, it gestures toward an embodied network of visual relations about black identity and subjectivity. Formally, there is a persistent elegance across all images, a grace to the recurring profiles, concealed gazes, open grins, abandoned seascapes. These photographers’ respective pictures are packed with intention, and often signal means of circulation and image making not contingent upon the gallery space. Yet united there, they seem to take a collective breath anew. In dialogue, these works go beyond offering varied visual forms and compositions, and perhaps urge us toward a more iterative, expansive mode of considering black identity and its renderings photographically.

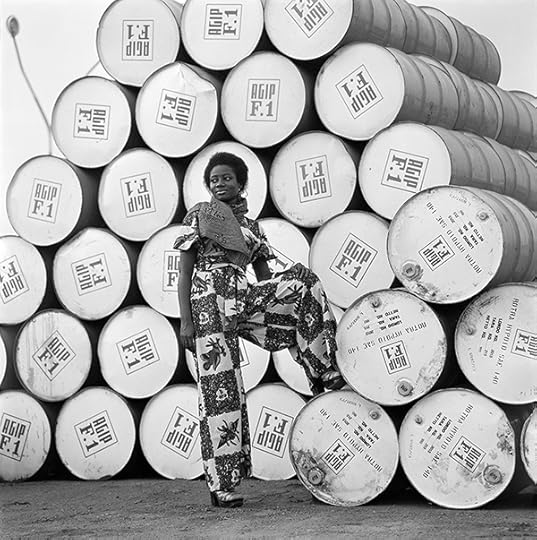

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Sikolo with Carolee Prince Designs), 1968

© the artist, courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: This Synthetic Moment seems to have been borne of a series of conversations and exchanges, but also equally operated as a site of inquiry when you were at a loss for words. I wonder if you could revisit your conversation with Thomas J. Lax, associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, which you’ve stated provided you with the seeds of the exhibition’s title?

David Hartt: When I was speaking with Thomas, we were discussing Unfinished Conversations (2017), an exhibition at MoMA that he had worked on and which was on view at the time. I was interested in the show’s proposition, which contained an expanded notion of black identity, beyond national constructs. The exhibition incorporated black voices from a variety of different backgrounds—Black British artists, African American artists, those from the African continent. For me it created a complex understanding of black identity, one that was expansive and complementary. At the moment that I happened upon Unfinished Conversations, I was initially at the museum to see Martine Syms’s Projects 106 (2017) installation. Through viewing her work, a two-hour feature-length film, and then John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation (2012), I began to recognize not only the conversation that was happening between the two pieces specifically, but also how these images provided a kind of synthesis, in terms of two generations of artists working with film. The concept took root across geography, but also in terms of temporalities.

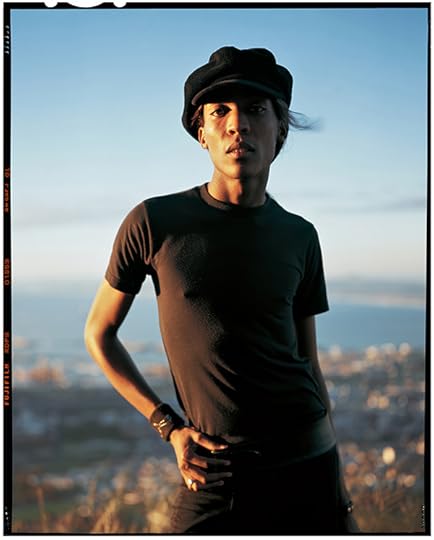

James Barnor, AGIP Calendar Model, 1974

Courtesy the artist and October Gallery, London

In my own practice, I was also coming to terms with a piece I had just finished, The Last Poet (2017). It’s a film I shot via drone, where I looked at the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. For the film’s narration, I spent two days at Stanford University interviewing Francis Fukuyama, considering the current state of our liberal democracy, and perhaps its decay. Throughout the course of our conversations, the language that he was using was uncompromising and terrifying. It was a very sober, poignant analysis of what we are experiencing. I didn’t know how I would react in the face of this account, but there was a complexity to the emotion that I began to feel, in giving agency to a voice that I wouldn’t necessarily agree with in its entirety. As the piece unfolded, I began to trust myself, and the viewer, knowing that they would be able to use their own values to process the commentary. From there, one thought that endured was the different forms of crisis that we’re experiencing—whether that’s class or race, but also along the lines of unstable borders and shifting political allegiances.

So in combining this experience vested in crisis and the moments of resonance across those two exhibitions, Thomas and I talked through these ideas, trying to find a word to describe them—these permeable boundaries present all around us. Out of that came the “synthetic.”

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 2016

© and courtesy the artist and courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York

Onabanjo: From the start, This Synthetic Moment has been intertextual, with these manifold references and allusions circling one another, informing its overall structure. This lyrical quality is writ large with the visual rhymes and echoes, but also with regard to the photographers’ biographies, which feed into one another in a manner that is quite organic and fluid. How did you arrive at the various bodies of work that populate the exhibition?

Hartt: The spine of the exhibition is Liz Johnson Artur. I first encountered her work when I was featured in an exhibition with her in Munich, and I remember falling in love with the work as it was presented. I already had her monograph, but it wasn’t until I saw the work presented that I realized its strength. You know, when you put work on display in an exhibition context, it can be quite cold and cut off from the life and the experience of the artist, but with her work, there was a strange, empathetic connection that was sustained. There is this central importance of generosity to her mode of presentation, in which she wants to be able to share, and explore with the viewer as they move through the work. There’s a kind of haptic quality to everything that she does.

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 2016

© and courtesy the artist and courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York

From there, everything else followed. I was interested in trying to find different voices that could expand on this notion of interrelationships through time, through space, through modes of subjectivity. Christopher Williams and Zoe Leonard came to mind quickly. With Leonard, I was reminded of one of my favorite photographs, Rear View (Geoffrey Beene Fashion Show) (1990), because of its immediacy and its confrontational qualities. So that led me toward an exploration of that body of work, and then I was reintroduced to One Woman Looking at Another (Carolyne Roehm Fashion Show) (1990), and that became another really important image that other lines of inquiry or thinking hinged upon.

Zoe Leonard, One Woman Looking at Another, 1990

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York and Galerie Gisela Capitan, Germany

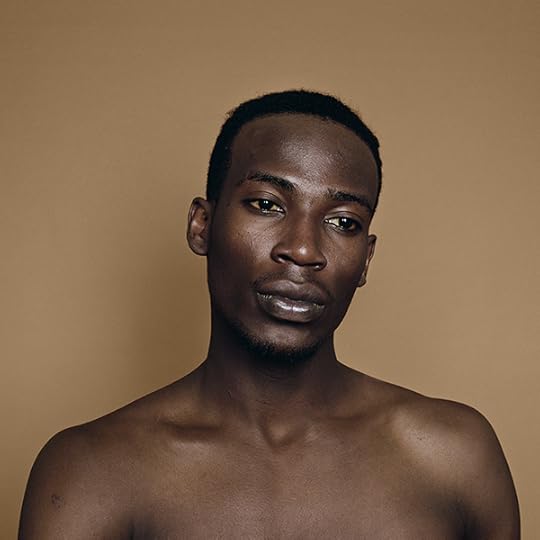

With regards to Williams, I was thinking about the photographs of Mustafa Kinte (2007), and in a conversation with Hamza Walker, he introduced me to the work of James Barnor and Kwame Brathwaite. I wasn’t familiar with either of them, but I realized immediately that they allowed me to speak in terms of an expanded geography, as well as an expanded concept of temporality and representation. With Barnor, there was a particular image of a beautiful Ghanaian model surrounded by Agfa chemistry containers, which just rang as a proto-Willliams, especially considering Williams’s darkroom images. The self-portrait of Brathwaite also related very nicely, again as a kind of proto-Williams. So it became a process of going back and forth, each image becoming contingent on another one.

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled, 1966

© the artist, courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Onabanjo: I’m interested in the different contexts from which these images arrive. Take Kwame Brathwaite and his work with the Grandassa Models and the popularizing of the phrase “Black Is Beautiful,” but also James Barnor’s legacy as the first Ghanaian photographer to use color, photographing Kwame Nkrumah and also working for Drum magazine in London, taking images of these gorgeous cover girls. So having those kinds of fashion and editorial visual vocabularies informing their practices, as well as in the work of Zoe Leonard and Liz Johnson Artur, I wonder how that shapes your understanding of these works living beyond the milieu within which they had circulated, and entering the gallery space together.

Hartt: I interpret these works through the lens of my own education and practice, a photographic one that came at a moment when conceptualism was prioritized. With that, I think what could happen, at least initially, is a sort of instrumentation in terms of how I’m contextualizing Brathwaite and Barnor, because what you’re saying in terms of the origins of their respective practices, and what their agendas were, is definitely outside of this kind of gallery context. So at first, I’m looking through the lens of a Williams or a Leonard, or even myself, in terms of how I understand their work coming together. That being said, I think it’s important to note that the images by Barnor and Brathwaite stand their ground. They change the reading of other images, especially Williams’s portraits of Mustafa Kinte (2007).

Christopher Williams, Mustafa Kinte (Gambia), 2008

© and courtesy the artist and courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Williams himself has said those images have been difficult to contextualize and that there is a kind of pressure in terms of addressing how they perform. Therefore, I feel there is a generosity, if you will, by having such portraits then juxtaposed with images by Barnor and Brathwaite. It’s precisely this space where the halo that they grant to Williams’s work is quite important—all of a sudden, the work begins to address subjectivity in a way that is within Williams’s intention, but as a white artist, is perhaps more difficult to make those kinds of requests. So while I recognize the very different kinds of realms in which they operate or were formed in, when brought together here, we begin to kind of appreciate the resonances that these artists’ works share, and grant one another. In having those pieces kind of coexist in the same kind of space, I think, electively, they all benefit.

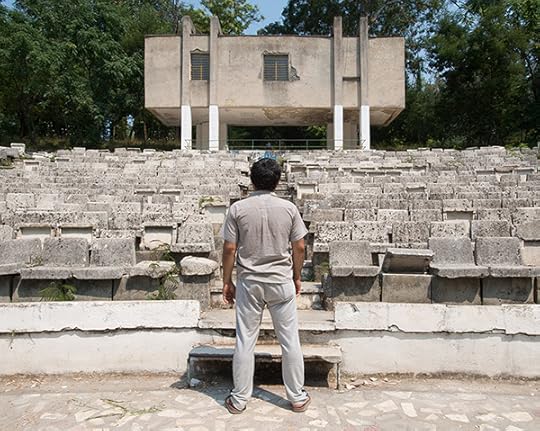

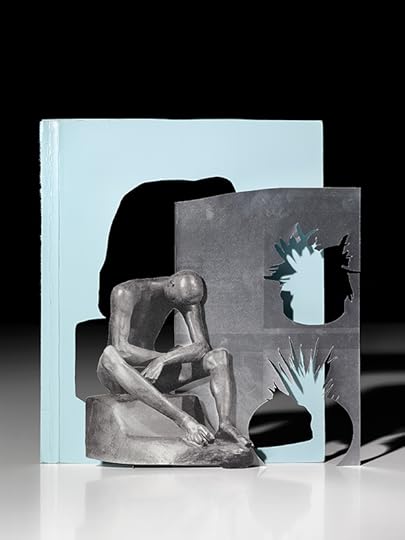

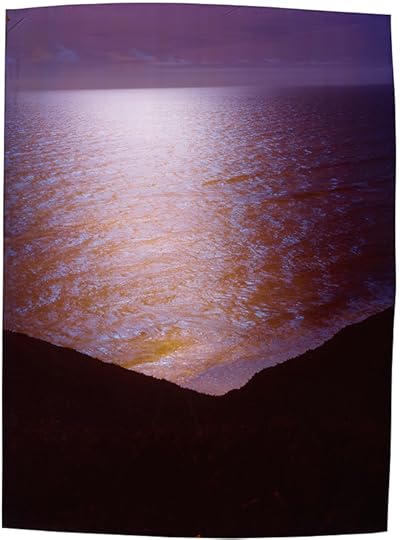

David Hartt, Interval XIII, 2014

© and courtesy the artist and David Nolan Gallery, New York

Onabanjo: You mentioned in a 2015 interview that “Our understanding of ourselves is deeply rooted in the spaces we occupy.” How do you consider your own work within these associative networks, and within the exhibition?

Hartt: I think that in terms of my own practice, the role that race plays is not immediately apparent. This notion of subjectivity, it’s implicit rather than explicit—perhaps except in the case of Stray Light (2011)—so dealing with the concept of race within the work was something that quite selfishly I wanted to engage. For me, the idea of blackness in my work has everything to do with my ability as a black artist to travel into different communities and cultural expressions, and to represent them in some other way, something typically the domain of white artists. There’s this kind of cultural colonialism that they’ve been able to enjoy, and this sets up a bizarre dichotomy in terms of representation: it’s either the perspective of the white colonizer, or a member of the culture that is being colonized attempting to recognize and depict themselves.

However, I am of the belief that in order for us to understand and learn more about these different positions, they have to be dimensionalized, and by “dimensionalized” I mean that they need to be depicted by more than one, or two—or however many have you—modes of analysis. So simply by my being a black artist engaging with these cultural experiences, I’m adding another dimension in terms of trying to understand what’s present there.

David Hartt, Interval I, 2014

© and courtesy the artist and courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York

Onabanjo: So there’s a refusal on your part, then. Rather than this being a linear or structured means of outlining representation, you’re offering something more associative, something freer and modular. The viewer can engage with these modes of documentation beyond just straightforward celebration, or just straightforward interrogation.

Hartt: Yes, this notion of subjectivity that we’re talking about has to do with looking at the act of photography and its relationship with these different kinds of subjects in a more complex way. It has to do with providing a latitude in terms of how the photographer operates, and what the photograph can do and what it can say. In that sense, with This Synthetic Moment, it’s vitally important to have somebody like Williams interrogate the idea of black representation, just as it is for Leonard, just as it is for Barnor or Brathwaite, or Johnson Artur. I think what we’re all doing is beginning to expand the fields of representation of this idea of black identity.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is Director of Exhibitions and Collections at The Walther Collection.

This Synthetic Moment is on view at David Nolan Gallery, New York, through March 10, 2018.

The post Black is Brilliant appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Behind the Scenes of Peter Hujar’s Bohemia

Aperture members met with curator Joel Smith to hear the stories behind Peter Hujar’s radical work.

On Wednesday, January 31, Aperture Patrons and Trustees met at The Morgan Library & Museum for an intimate after-hours tour of Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, led by Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography Joel Smith. The exhibition features more than 140 of Hujar’s photographs and contact sheets, which portray avant-garde pockets of New York City from the 1970s and ’80s. Along with a book of the same name, published by Aperture this past year, the exhibition follows Hujar’s career, divided thematically into sections. Smith described the sequence of the exhibition as: “Every image is a fresh thought, so you have the chance to see the work as interrelated and yet a puzzle.” Throughout the tour, Smith helped decipher this puzzle of Hujar’s complicated life for Aperture members.

A highlight of the exhibition is the photograph Daisy Aldan (1955) of Hujar’s high school teacher, who deeply inspired the artist as a youth. Smith shared many stories behind the images, including photographs of celebrities like Susan Sontag, Hujar’s lovers, and communities, such as drag queens, that historically haven’t been featured on museum walls. Hujar was obsessed with conveying “what makes an individual truly fascinating”—as befitted an artist who was so fascinating himself.

The tour offered great insight into Hujar’s life and work, and meditated on the message he was never able to fully articulate during his lifetime.

Peter Hujar (1934–1987) died of AIDS at age fifty-three, leaving behind a complex and profound body of photographs. A leading figure in the cultural scene of downtown New York in the 1970s and ’80s, Hujar was admired for his portraits of people, animals, and landscapes. Since his death, his work has been the subject of major retrospectives at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland, and he is included in permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

Click here to join Aperture’s membership program or contact our membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post Behind the Scenes of Peter Hujar’s Bohemia appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 27, 2018

Lola Flash is Ready for Her Moment

In her first retrospective, Lola Flash celebrates queer legacies through vibrant portraiture.

By Jessica Lynne

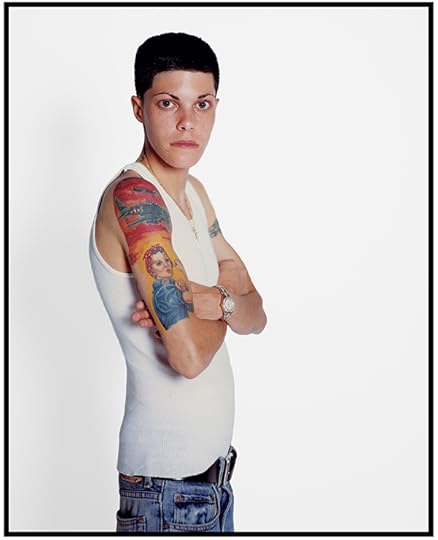

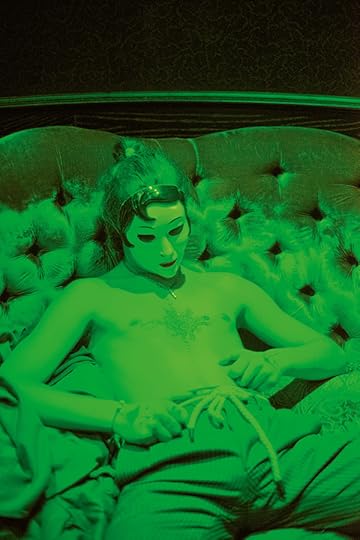

Lola Flash, karisse, 2003, from the series [sur]passing

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lola Flash has spent her career documenting and celebrating the lives of queer people of color through photography. Entering into the field in the 1980s as the HIV/AIDS epidemic began to take hold, Flash became an ardent activist through her image making as she told stories of queer life in New York City during a time of change. A core member of ACT UP, Flash was deeply entrenched in the work of caring for a generation that was reckoning, at the time, with a new disease that transformed the LGBT community; as a result, her art and activism were intimately connected. Today, Flash’s germinal bodies of work—such as SALT, an intimate portrait series of women over the age of seventy, or surmise, which explores gender perception and (mis)representation—continue to serve as an important touchstone for any student of photography, and certainly the lineage of art produced by black, queer women. On the occasion of the opening of her first retrospective at Pen + Brush, I spoke with the critically acclaimed photographer about what it means to reflect on a career of activism and art.

Lola Flash, tanya, 2008, from the series surmise

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Jessica Lynne: Organizing a show of this scale requires you to think about how you’ve evolved as an artist, formally and technically, which must also bring up so many memories. What does it mean to be in this moment of reflection?

Lola Flash: It is very emotional. It’s great to be working with a gallery, although, to be honest with you, I never really wanted gallery representation. My focus as a photographer is really just to say to my beautiful subjects, “Lola Flash thinks you’re beautiful. She’s going to drag her big old camera over and take a portrait of you.” But it’s been great working with the gallery. I really trust Parker Daley and Dawn Delikat at Pen + Brush. As art historians, they saw how my older work, the cross-color work, led to what I’m doing now. In hindsight, I did not really see the connection.

All last year, I was just driving myself crazy. I was thinking, “I’m invisible.” I was making all these posts saying, “Do you see me?” And continuously—it’s nothing new—I’ve been going to galleries and museums forever and feeling invisible. So, thanks to this exhibition, I’m finally getting the recognition that is long overdue.

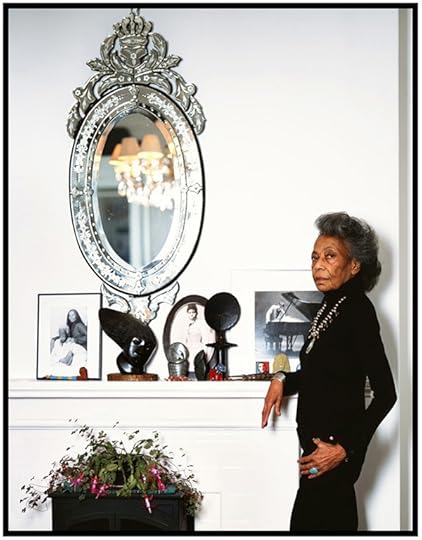

Lola Flash, Murray, 2016, from the series LEGENDS

Courtesy the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Why do you think that’s happening now? What feels different for you about this moment versus a year, five, ten years ago?

Flash: So much has changed: the Obama era, the outstanding folks like Deborah Willis, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and even artists such as Carrie Mae Weems and Kerry James Marshall. These people have helped create a different and positive model of the African American experience and I am riding that wave. And, of course, I am terribly thankful to Pen + Brush for seeing me and promoting my work in such a gorgeously professional manner.

Lola Flash, toni (Toni Parks), 2011, from the series SALT

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: What does it mean to celebrate and think critically about the lives of gay, lesbian, and queer black folks and other queer people of color, and also recognize that sometimes those people may not find their way into these kinds of art institutions—that the infrastructures are often set up to not allow that in the first place?

Flash: Right. That is why I never really wanted gallery representation. For years, when I was younger, I used to show in pubs or restaurants, because I wanted the people who I was photographing to be part of the conversation. One of my friends, Arnie Charnick, he used to do—he still does—a lot of amazing murals in the East Village. He was one of the artists I really started to admire early on, and he never really wanted a big show. He was just really happy with making his murals.

But it wasn’t until I saw the Kerry James Marshall retrospective at the Met Breuer and noticed the way that people were looking at his paintings that I thought to myself, Maybe there is value in exposing my work to audiences that I am not particularly concerned with, thematically speaking. I think it opened up my mind to a subject that I was really kind of against for so long. Of course, I want my work at the Met, of course I want my work at some of these big places. But it’s definitely not the root of why I do what I do.

Lola Flash, Vickster, 1999, from the series Cross-Color

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Was there a moment when you realized that photography was the tool that you wanted to use as you reckoned with all of these larger, complex concerns about identity?

Flash: When I was a child, the camera was a toy that brought me hours of fun. Once I became a photography major at MICA, I created a process which I coined “cross-color.” This process was before Photoshop, and was a comment on the notion of perfect “Kodak days”—in reverse. I was known for this process; it was my signature style. The colors were so vibrant and all hues were reversed. Blue became red and white became black. I was consumed by the psychological meanings of what colors were supposed to mean. My work continues to focus on issues around race, gender, and sexism, but in a more direct way.

thato, 2017, from the series [sur]passing

Courtsey the artist and Pen + Brush

Lynne: Now that you are in this moment of reflection, what’s coming next for you, Lola? How do you think about the futurity of your work and practice, your self-sustainability, and legacy?

Flash: Legacy is a very important part of my drive. I think about all the people who stood up for our rights—my ancestors—I feel like I have a commitment to them, and I’ve been given the tools. I have a presentation about legacy that I show the kids I teach in the first days of the school year. I say to them, “If you don’t feel like you have a legacy, then maybe it’s you who’s going to start it.” And so, for me, I want to make sure the work is contextualized properly, alongside the work of my peers, so that people can see the validity of my photography.

Jessica Lynne is the coeditor of ARTS.BLACK.

Lola Flash: 1986–Present is on view at Pen + Brush, New York, through March 27, 2018.

The post Lola Flash is Ready for Her Moment appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 21, 2018

Roaming Without End

A group exhibition in Paris navigates documentary strategies in a directionless world.

By Wilco Versteeg

Henk Wildschut, Ville de Calais, 2016

© the artist

Everything about In Between (En suspens) is understated—except its politics. This group exhibition at LE BAL in Paris presents an outstanding slice of regionally diverse contemporary documentary projects. The show forgoes facile conclusions about the state of our visual culture, our politics, our failings and blind spots. Instead, it opts for a poetic, peripatetic tour without beginning or end.

Featuring thirteen artists from the United States, Africa, and Europe, In Between is a willingly unfinished and incomplete cartography of the most burning issues in documentary aesthetics today: the place of fiction in a medium feeding on reality; the place and function of the museum; the use of computer-generated imagery; the relevance of old-school photojournalism; and the overall political impotence of film and photography in an age that is oversaturated not only with images but also with autonomous image-making technologies. In Between lacks a central curatorial narrative; instead, it activates the visitor to forge links between the individual works. The catalogue, through its black-and-white reproductions and softcover binding, lacks the authoritative appearance and tone of the usual weighty tome accompanying shows. Instead, this ephemeral quality contributes to the ambiance of open-endedness of the exhibition.

Debi Cornwall, Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay, from the series Beyond Gitmo, 2017

© the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

The exhibition spaces have been filled to capacity with photography, video, and prints, but nowhere does it feel overcrowded. Politics hover constantly above the artworks; In Between provides a map of post-9/11 conflict from a western as well as eastern perspective. Debi Cornwall’s impressive Beyond Gitmo shows former prisoners of the Guantánamo Bay detention center. Her large photographs are supplemented with short texts factually but tragically informing us how long they have been detained. Cornwall’s work maps ruined lives in times of perpetual war and failing international politics. Kurdish artist Hiwa K, in View from Above, shows the inhumanity of bureaucracy confronting asylum-seekers. Using computer-generated imagery based on the real-life statements of “M,” Hiwa K reconstructs a war zone, detailing a city “M” claims to be from to obtain refugee status. Fact and fiction entangle in a manner that leaves visitors wondering what the limits of both are in the context of documentary photography.

Hiwa K, still from View From Above, 2017

© the artist, KOW, Berlin and Prometeo Gallery di Ida Pisani, Milan

Henk Wildschut’s Ville de Calais perfectly illustrates the understated yet highly political nature of In Between. Wildschut photographs the subsequent construction, dilapidation, and removal of a refugee encampment in the dunes of Calais, a French border city. The improvised camp, deemed a symbol of the failure of European immigration policy and an affront to the supposed humanism of the European Union, harbored a handful of immigrants wishing to cross the channel to England in 2015, but reached thousands of inhabitants by the time it was dismantled at the end of 2016. Wildschut’s series, of which only a small selection is presented, shows the rise and fall of this micro-civilization: from early, primitive dwellings to a community with churches, mosques, grocery stores, and various competing neighborhoods. Between the appearance and disappearance of the camp, as if it were a natural process, we must imagine the lives of the people living in this landscape of decay.

Mélanie Pavy, still from Go Get Lost, 2018

© the artist

One important theme of In Between is surveillance and control. What is the role of visual artists vis-à-vis commercial and state apparatuses doing part of the artist’s job: mapping, showing, representing, and interpreting? Former Magnum photographer Luc Delahaye’s video installation Eyal Checkpoint was made with a smartphone filming a seemingly endless stream of Palestinians crossing into Israel to work. The mechanical sound of the turnstiles combined with the flux of fast-appearing and disappearing faces becomes unbearable if we consider the politics behind this seemingly quotidian event. Another work, a promotional video for a Chinese company, shows the state-of-the-art application of fully automated mining in a plethora of databases coupled with real-time facial recognition, thus entering into a dialogue with Delahaye’s more observational use of surveillance. Human agency seems to be rarer in today’s world, humans instead becoming the targets of the technology we invented.

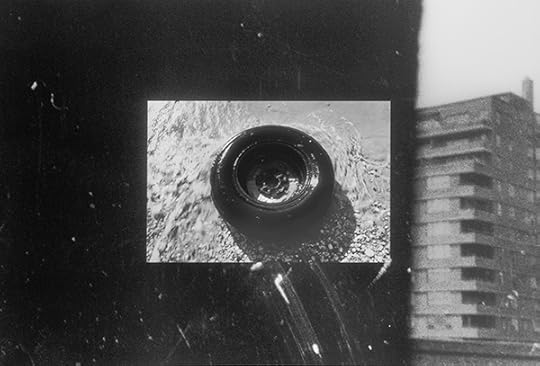

Sebastian Stumpf, still from Puddles, 2013

© the artist and Galerie Thomas Fischer, Berlin

In Between walks in step with our time: our love-hate relationships with states of in-betweenness, with not knowing who we are, where we are going, and where our culture is headed. In short, in a time that is profoundly felt to be without direction, In Between does not provide answers but instead shows diverse routes in documentary practices that shed light on our culture at the crossroads. Our task is to actively engage with and navigate through this brave new world.

Wilco Versteeg is a researcher in visual culture and war photography at Université Paris Diderot.

In Between (En suspens) is on view at LE BAL, Paris, through May 13, 2018.

The post Roaming Without End appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Robert Gober’s Willful Revision

The sculptor’s rarely seen photographic series reveals the power of memory.

By Alex Jen

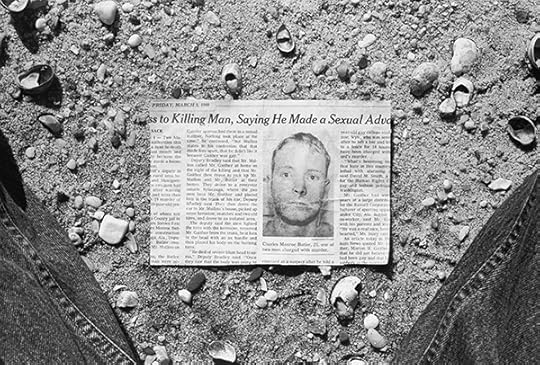

Robert Gober, Untitled, from the series 1978–2000, 1978–2000

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

In 1978, the artist Robert Gober made photographs on a drive from Manhattan to Jones Beach on Long Island, printed them, and forgot about them. Twenty-two years later, in 2000, while making a group of photographs of washed-up litter near his studio in Peconic, Long Island, he recalled the images, but could only find the contact sheets. Gober rephotographed the contact sheets, leaving some as they were and digitally insetting the new photographs in others, snapping these memories together with a harsh, redacted precision. The result, 1978–2000 (1978–2000), originally compiled as an artist’s book for Gober’s presentation at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001, and currently on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (ICA), frames moments of loss connected by place but obscured by time.

Robert Gober, Untitled, from the series 1978–2000, 1978–2000

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

Gober does not privilege a numbering or sequence for 1978–2000. In one frame, the inset image of a glistening, greasy wheel blocks some fading apartments, interrupting the breezy drive like a bad memory. Once useful, the wheel now lingers as a gaping cavity; waves froth around it viciously, but it doesn’t budge. Another frame centers a putrid, bulging pack of Kraft Mayo against a forest haze of strange, jerky branches, while yet another shows two pale, hairy legs that lead into a tangled, billowing plastic bag, natural light suffusing the condensation built up on the inside. Both the mayo and the bag blister, waiting to be punctured, their contents bodily and overripe. 1978–2000 holds you precariously, the blur and grain in each photograph threatening to dissolve into smog.

Robert Gober, Untitled, from the series 1978–2000, 1978–2000

Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

In its layers of both time and image, in the rephotographing and reprinting, 1978–2000 implicates the decay and willful revision of memory. If you can remember memories differently, should you? This question hits an emotional center as the installation directs viewers into a corner. There, in one photograph, framed by the inner thighs of a subject’s heavy denim jeans, is a clipping from the March 5, 1999 issue of the New York Times, which details the homophobic torture, killing, and burning of Billy Jack Gaither in rural Alabama by Steven Eric Mullins and Charles Monroe Butler, Jr. Gober has cut out only a fragment of the article, however; the lack of the full story heightens the abruptness of our imagined violence of the crime. The adjacent photograph in the installation builds on this composition, as Gober’s hand blocks the clipping, gently holding a letter to the editor that demands “Orthodox Jews, conservative Christians and others” should have the right to oppose homosexuality without being seen as bigots. Gober believes in freedom of speech, even when it hurts.

Robert Gober, Untitled, 1994

Courtesy the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

At the ICA, 1978–2000 is balanced out by Untitled, which sits at the center of the gallery and doesn’t, at first glance, take up much physical space. The sculpture consists of a bronze grate in the ground that leads down a bricked hole to reveal the bare, beeswax chest of a man. A chrome-plated drain is lodged where his heart should be, and a shallow film of water gurgles over him, swaying the human hairs on his body. The grate and drain are both walls and holes, blocking but letting us look through; they pull all the dregs toward them, to be sucked in and never seen again. Untitled frames the body and makes it the center of attention, but then blocks it—like 1978–2000 does with its photographs of once-used debris that obstruct memory. You can see your reflection in the water, a specter beside the sculpted body, whose wax torso appears alive; it heaves somewhere between peace and distress. You don’t want to leave, but eventually you have to. Neither you nor anyone else can help that trapped body anyway.

Alex Jen is a writer and curator based in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Robert Gober is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, through February 24, 2019.

The post Robert Gober’s Willful Revision appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 20, 2018

Photofairs Comes to San Francisco

Erica Deeman, Asaba, 2015. © the artist and courtesy Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco

Matt Lipps, Act IV (silver), 2016. © the artist and courtesy Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

Hai Bo, South series, No. 28, 2012. © and courtesy the artist

Gohar Dashti, Home, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Robert Klein Gallery, Boston

John Chiara, Westline Drive at Mussel Rock, Variation 2, 2017. ©the artist and Courtesy Haines Gallery, San Francisco

Noémie Goudal, Telluris, 2017. © the artist and courtesy Les Filles du Calvaire, Parie

Sophie Clements, still from How We Fall, 2017. © and courtesy the artist

Tammy Rae Carland, Smoke Screen, 2013. © the artist and courtesy Jessical Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

Klea McKenna, still from Untitled, 2018. © the artist and courtesy Euqinom Projects, San Francisco

Wolfgang Tillmans, Paranal ESO, sky and ocean, 2012. © the artist and courtesy Sage, Paris

Erica Deeman titled her breakout spring 2017 solo show at San Francisco’s Anthony Meier Fine Arts Brown. Deeman, who was born in the UK and now lives in California, presented a series of portraits of men from the African diaspora, set against a backdrop the shade of Deeman’s own skin. The portraits drew comparison to the work of Rineke Dijkstra and Dawoud Bey, and announced a new talent in contemporary photography. Deeman’s powerful work, together with photographs by Tammy Rae Carland, John Chiara, Noémie Goudal, Matt Lipps, Alec Soth, and Wolfgang Tillmans, is among the many highlights to be found at Photofairs | San Francisco, which will also feature public conversations with artists David Benjamin Sherry and curators Virginia Heckert and Sarah Meister.

Photofairs | San Francisco will take place at the Festival Pavilion, Fort Mason Center, San Francisco, from February 23–25, 2018.

The post Photofairs Comes to San Francisco appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 15, 2018

Between Dusk and Dawn

Tobias Zielony captures the colors and moods of Ukraine’s queer nightlife.

By Camila McHugh

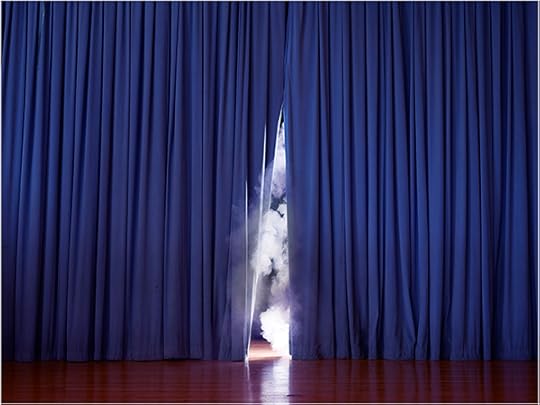

Tobias Zielony, Shed, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

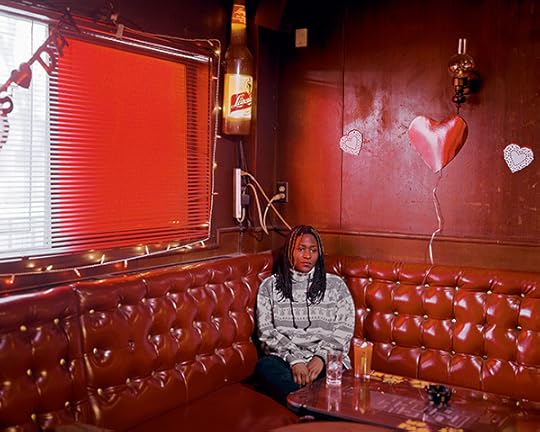

Tobias Zielony’s work offers a lingering, sidelong view at communities at the edges of society. His images blur boundaries between documentary and fine-art photography, offering ambiguous, often fragmented scenes. Standing apart from documentary photography, Zielony, who was born in 1973 in Wuppertal, Germany, nevertheless directs his gaze at the apparatus of that form of storytelling. In Maskirovka (2016–17), a recent project made in Kiev (also spelled Kyiv), Zielony photographed the LGBT community living in the wake of the 2014 revolution. Maskirovka recalls Zielony’s early projects depicting youth, but it has a strong political undercurrent, as working in Ukraine allowed him to examine the current state of Europe. The project also became a mode of exploring the remaining possibility of underground culture, in an age where social media offers illusions of connectedness.

Zielony is a talker: He is informed and gets involved, often spending significant time with his subjects. He integrated himself into Kiev’s LGBT scene with the help of Tasia, an activist who is also part of the techno scene, whom he met at a workshop in Germany. In the monograph of Maskriovka, published last year, Zielony included extensive interviews as a companion to his shadowy photographs of these isolated figures with gazes askance, peering into a mobile phone, smoking a glowing cigarette, or standing on a threshold. He is interested in stretching the space between reality and the way it is depicted, communicating other forms of truth. I recently spoke with Zielony at his studio near Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin.

Tobias Zielony, Make Up, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

Camila McHugh: In your recent Maskirovka project in Ukraine, as well as subsequent projects in Latvia and in your hometown of Wuppertal, you’ve returned to photographing youth culture. You have photographed many young communities, often on the fringes of society, in the past—in Winnipeg, Canada, in 2009 and in rural California in 2008, for instance. What was it like returning to this sort of work?

Tobias Zielony: Well, the project in Ukraine was looking more attentively at political issues, but it is true that I hadn’t done a project on youth or underground culture for some time. So it was interesting to go back and see how much youth culture had changed, particularly in terms of fashion and social media. After photographing in Kiev, I photographed in Riga and Wuppertal, and it was so surprising how similar a lot of things are, especially the fashion. I was struck by how quickly this kind of mirroring is happening because of social media. There was something particular to Kiev, a sort of remaining underground feeling, which I don’t think you find many places anymore. We haven’t had it in Berlin for a long time. I think it is because in somewhere like Kiev, the community is politically and culturally isolated from normative society. Somewhere like Berlin, the boundaries have been blurred for a long time. It also felt like this culture hadn’t been commercialized yet in Kiev, at least during the moment when I was there. The underground community was more of a necessity or a matter of political resistance, so that felt very unique, and also quite warm, in terms of a sense of bonding and solidarity. But it may have begun to change already; I haven’t been back.

McHugh: How do you feel about documenting youth culture now that you’ve noticed this mirroring and other ways in which social media has affected young people?

Zielony: These shifts will inevitably affect the sort of work I am interested in making. Looking at youth culture wasn’t the main purpose of my work in Kiev, but it did make me think about what my role as photographer really is. It is an interesting dynamic, when people like my photos, but they aren’t perfect Instagram material or don’t quite fit the mold of what they consider cool. I often gift my photographs, and twenty years ago people would put them on their wall, but now they put them on Instagram the same night. And so their reaction is more immediate—you see what images people choose to post or like. And then people also started putting filters on the images. There was a guy in Riga who put this analog filter on my digital image with dust specks and everything. But instead of getting mad, I actually think it’s interesting. Or people crop or whatever, saturate the colors. But still I think—if I’m not really doing the coolest or most fashionable thing, it’s probably because I have a different role. You could say I transport a kind of aesthetics or political or cultural situation into a different context, like the art world, but I don’t know how different those contexts are anymore. The context of the art space and the social media space and the actual club—I don’t think it is so easy to distinguish between those spaces anymore. So I think it’s more about seeing connections and communicating my own experience. Or looking at something very specific, like the ideas of masks, which I focused on in Kiev. And then there is also the question of what audience I have in mind. Do my images from Kiev somehow make sense on some level to an audience in London or New York or Berlin?

Tobias Zielony, Shine, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: There is a nostalgic click on some level for people in Berlin, like a yearning for what they imagine Berlin used to be. Or in London, as well, for the ’90s of early Wolfgang Tillmans, for example.

Zielony: I think that’s happening. There is a sort of desire in both directions. People all over the world, though maybe especially in Ukraine and Russia, are looking at this ’90s club culture and aesthetic and they’re copying it. Berlin is kind of the ultimate desire and ultimate cool for them. And then here in Berlin, people feel like things have changed so much and they want to return to the sense of community and wildness of a real underground scene, like the one in Kiev, for example. So there are different perspectives or forms of nostalgia at play. My work ends up positioned between those yearnings.

McHugh: As you mentioned, your work in Kiev also directly addresses the political situation there after the 2014 Ukrainian revolution. You titled the work Maskirovka, a term for a Russian military tactic of deception. How did you begin to think about the situation in Ukraine, and your work, in conversation with the term?

Zielony: Maskirovka is a term I was aware of even before the project began, but I came across it again in some research I was doing about masks in Ukraine. Tasia, one of the women who appears in the photographs and who I also interviewed for the project, noticed my interest in masks and began telling me how prevalent masks are in the Kiev party scene. I looked into it further and found that during the so-called Maidan revolution, people were wearing masks most of the time for protection from tear gas, smoke, and so on. And some people were even wearing fancier or funny masks, like medieval helmets and stuff. These masks became sort of a weird, popular, Pop art kind of thing in the face of violence. So in noticing this phenomenon of disguise, I began thinking about the word maskirovka. It’s a Russian term and there are lots of famous examples, like the disruption of the Prague Spring of ’68 and more recently the occupation of Crimea, which began in 2014. When Russia occupied Crimea, they sent special forces in green uniforms without any Russian insignia. Despite the lack of identifiers, it soon became evident that this was a Russian intervention, but by the time there was enough consciousness of what was going on to react, it was already done. This was followed by the conflict in eastern Ukraine, a proxy war that had not been declared. People also use maskirovka to refer to this hybrid state of undeclared, but evident, war or occupation.

Tobias Zielony, Cover, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Titling your project Maskirovka draws attention in part to the phenomenon of the masks: a few of your subjects appear in the masks that Tasia mentioned are popular clubbing accessories. What significance does this notion of a hybrid state have with regard to the work, or Kiev’s LGBT community?

Zielony: I suppose I’m playing with the possibilities of the term as a metaphor of sorts, but this hybrid state of undeclared war is also an everyday reality for the subjects of my photographs and for everyone in Kiev. Everybody is somehow involved in the war—as a volunteer soldier or a medic, or like Vicky, who I interviewed—she is a therapist who deals with people who have been traumatized. And then obviously everybody has someone close to them who was hurt or killed. Kiev is hugely affected, the wound of the war is present, the signifiers of tanks and people in uniform are there, but people hardly seemed to speak about it and no actual fighting is taking place. And it’s not clear when or how anything will change. If you look at the queer community specifically, it is also a strange situation, as Ukrainian leadership has made some moves toward tolerance: the police were protecting Kiev Pride instead of beating up participants this year, for instance. But then it’s dangerous to kiss or act out in the street. This creates a situation where people cautiously move between openness and hiding. A mask becomes an apt metaphor there, too.

Tobias Zielony, Apartment, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Your work is presented in an art context, but requires significant understanding of a political and cultural situation. You published a series of interviews with some of your subjects as a companion to the photographs, and the project took place in the wake of mass media coverage of Ukraine. You also studied both documentary and fine-art photography. Do you see your work as a hybrid of the two?

Zielony: Well, first it is important to say that the same photograph can have a different meaning depending on the context it is seen in. As you said, my work is intended for an art context, but also occasionally is presented editorially, like this work in the pages of Aperture. My strategy does have roots in something perhaps more editorial, that sort of storytelling. I’m kind of exploring that tradition—more like investigating the possibilities and limitations of that form of documentation, rather than really participating in it. It is kind of a referencing, in a sense.

McHugh: I noticed a similar motion in your interviews as well. By interviewing a fixer, for instance, you utilize a mode of sort of turning the lens toward the journalistic apparatus, as opposed to participating in it.

Zielony: Right—I am definitely not a journalist. There are a lot of journalistic standards that I’m not interested in participating in: I don’t feel obliged to tell the real story or the whole story or, on some level, even the truth. But there has to be another kind of truth in my work or, like, a lot of different truths. It’s not that I want to lie; the image has to be connected to my experience and the experience of the people around me.

Tobias Zielony, Line, from the series Maskirovka, 2016–17

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

McHugh: Right, I noticed that—similar to the sense of a glimpse into the edges or periphery of a world that I get from your photographs—your interviews also give space to narratives that remain outside of typical news media documentation. Like when Vicky spoke about exhaustion as a major effect of revolution, for instance.

Zielony: It’s so difficult to understand what’s going on and find the right pictures or the right words for it or whatever, so it’s interesting that everybody has their own theory. But I do think it is important to find words or images or characters, because otherwise you leave the higher powers to do the defining, whether it’s Russia or the Ukrainian government, and you don’t want to let them do their thing without any room for being able to describe or criticize what is going on.

McHugh: How do you see the role of photography in facilitating that form of definition?

Zielony: There is a relationship between reality and what comes out of it on an image level. And it’s all about this relationship basically, what’s happening in between, and what role photography or the camera plays in that process. At the moment, with the advent of Instagram and so on, what’s happening in “reality” and what photography is, are increasingly fixed together. I’m interested in what photography can do while maintaining some sort of space or distance from reality. That disconnect, almost. So when people ask me, it’s easier to say I’m a photographer, because it’s an easier way for them to understand what I’m going to do—I’m going to take photographs—but the way I think and build my life is more the life of an artist. I find that I am in kind of an in-between position, between the art and photography worlds, and it’s not very comfortable, but I think that is what photography is about. Or can be about.

Camila McHugh, a curator and art critic based in Berlin, is the cofounder and director of the project space East of Elsewhere.

Tobias Zielony’s work was featured in Aperture issue 229, “Future Gender.” His photobook Maskirovka was published by Mousse in 2017.

The post Between Dusk and Dawn appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 13, 2018

The Many Worlds of Susan Meiselas

A comprehensive exhibition celebrates the photographer’s unique approach to storytelling.

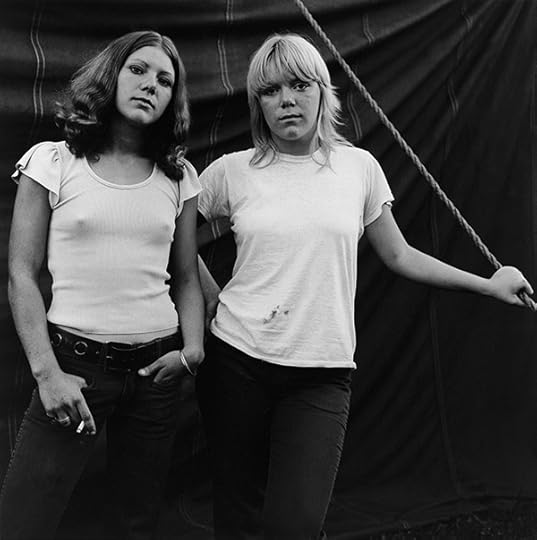

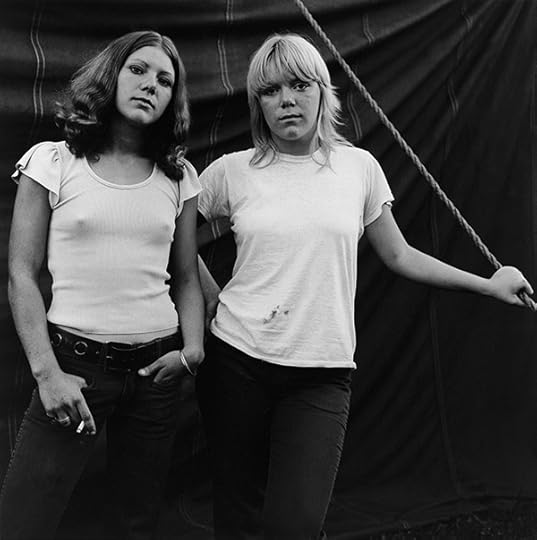

Susan Meiselas, Debbie et Renee, Rockland, Maine, 1972, from the series, Carnival Strippers, 1972-1975. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Returning home, Masaya, Nicaragua, 1978. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Searching everyone traveling by car, truck, bus or foot, Ciudad Sandino, Nicaragua, 1978. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Road to Aguilares, El Salvador, 1983. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Concrete blocks mark the mass grave in Koreme, Northern Iraq, 1992. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Mistresses Solitaire and Delilah I, the Dressing Room, 1995, from the series Pandora's Box. © the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas, Janet, Room 9, Black Country, United Kingdom, 2015, from the series, A Room of Their Own. © the artist/Magnum Photos

The current retrospective of Susan Meiselas’s work, a coproduction of Jeu de Paume, Paris, and Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, curated by Carles Guerra and Pia Viewing, spans four decades of photographs, up to her recent collaboration with women in domestic violence shelters in the U.K. “Trying to understand my relationship as a photographer to the subject as, or to, a community is consistently the preoccupation that has guided my work,” says Meiselas. The exhibition is a testament to the way Meiselas has continually asked herself that question over the years. Her photographs depict worlds as divergent as American carnival strippers, teenage girls in New York, and the peoples of Nicaragua, Kurdistan, and El Salvador.

Susan Meiselas is on view at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, through May 20, 2018.

The post The Many Worlds of Susan Meiselas appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

How to Witness Nothing (and Everything)

Photographer Edmund Clark and historian Crofton Black trace a network of black-site prisons.

By Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark, Bagram Airbase, from the old Soviet control tower, from the book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Flowers Gallery, New York

In principle, to testify—not being a witness but testifying, attesting, ‘bearing witness’—is always to render public. The value of publicity, that is of broad daylight (phenomenality, openness, popularity, res publica and politics) seems associated in some essential way with that of testimony. The idea of a secret testimony seems thus a contradiction in terms. Especially when the experience of the secret itself implies some inner witness, some third party in oneself that one calls to witness. —Jacques Derrida

A giant cross stands on a mountaintop overlooking the city, outlined at night in bright white neon. A German citizen saw this view, twelve years ago, from a hotel room in Skopje, Macedonia. The American embassy is nearby, across the park, past the zoo. He was passed to the CIA after 23 days of interrogation in this room, by Macedonian government personnel. The layout fits my copy of his hand-drawn plan: top floor opposite the lift. His description of the view matches too; the cross, a broken chimney. Other details of his testimony differ from what is here now: the hotel has fewer floors; blue venetian blinds replace curtains; a smaller table. Have any of the three star fixtures and fittings been touched by us both? Do we share the same bed?

Edmund Clark, Room 11, Skopski Merak hotel, Skopje, Macedonia, from the book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Flowers Gallery, New York

These words are written in room 11 of this side street hotel. I am trying to make sense of four years spent tracking and photographing sites of extraordinary rendition. I have witnessed nothing during this time, but the making of these photographs has become an act of testimony. It was not possible to see the secret journeys of extraordinary rendition or the interrogations that punctuated them, but it has been possible to glimpse the places and networks that circled them.

The photographs in this project show only surfaces of these events through detectable traces and liminal sites or objects: unremarkable streets, facades, furnishings, ornaments and detritus. It is the opacity of these images that reveals something of the condition of extraordinary rendition. Look at them and they show nothing. Look into them and they are charged with significance. They are veneers of the everyday under which the purveyors of detention and interrogation operated in plain sight. This is the banal complicity of today’s global war; the everyday absurdity and dread of Kafka’s world made real.

Edmund Clark, Richmor Aviation’s office at Columbia County Airport, New York, from the book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Flowers Gallery, New York

*

Assembling a large format camera and tripod in a remote car park on the edge of Fayetteville airport, North Carolina, a man approaches from the low white building to enquire as to my purpose. We both know there is only one reason for my being there. I explain that I am photographing locations associated with extraordinary rendition and that his company has been mentioned in that context. He denies any involvement but acknowledges that I have the right to be there, requesting only that I don’t photograph his employees. I agree. Minutes later he returns with a point-and-shoot camera and says that he has the right to photograph me too, taking several shots of me and the number plate of my hire car. As I drive away, a police car appears and follows me to the airport perimeter.

Looking for meaning in unexpected areas began with the weak points of business accountability: the traceable bureaucracy of invoices, documents of incorporation and billing reconciliations from companies using the familiar paths and carriages of executive travel and global exchange. Pieces of paper bearing the traces of small-town and Small and Medium Enterprise America, seeking profit from the outsourcing of detainee transportation. Visually compelling and eloquent, as well as sources of evidence, they are the product of a circuitous journey by researcher Crofton Black, working for lawyers on behalf of the transported, to find links and join dots; to see through the bureaucratic and circumstantial to the forensic. The structure of this book is an evocation of this network, with a system of cross-referencing to suggest alternative paths through the forest of documents and images; an experience that by turns sheds light on the process and acknowledges its impenetrability.

Edmund Clark, A room formerly used for interrogations in the Libyan intelligence service facility at Tajoura, Tripoli, from the book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Flowers Gallery, New York

Equally cogent are the documents and reports that seek to define the scale and experiences of extraordinary rendition. These include police files, human rights reports, national and transnational inquiries and internal secret service investigations. It is here that testimony of those caught up in the so-called Global War on Terror can be found and is reproduced, in fragments, in this book. So too can the counter-forensics of secrecy, censorship and obfuscation that shade the paths to accountability.

*

The documents and photographs in this project are archaeological. These are artefacts of research; things made by man; excavated, extracted, revealed. As traces of absence, or evidence, or that which makes anything evident (videre—to see—at its heart), their purpose is as part of a present forensic process into the procedure of extraordinary rendition. The existing narrative—where it can be seen at all—is easily obscured by denial and secrecy. It is perhaps as a record of such negative evidence—and as a document of negative publicity—that this work may form part of a future discourse and future history.

Edmund Clark is an artist based in London. This feature is adapted from the Aperture book Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition.

The post How to Witness Nothing (and Everything) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 8, 2018

Alec Soth Revisits His Legendary First Book

How the American photographer fell in love with photography.

By Aaron Schuman

In 2004, Alec Soth published his seminal monograph Sleeping by the Mississippi to widespread critical acclaim, helping to establish both his own and the book’s place firmly within twenty-first-century photographic culture. After being out of print for nearly a decade, a new edition of Sleeping by the Mississippi was released by MACK earlier this autumn. Although it bears a striking resemblance to the original first edition, it also contains a number of subtle and revealing tweaks, and once again affirms the book’s remarkable power, relevance, and long-lasting resonance.

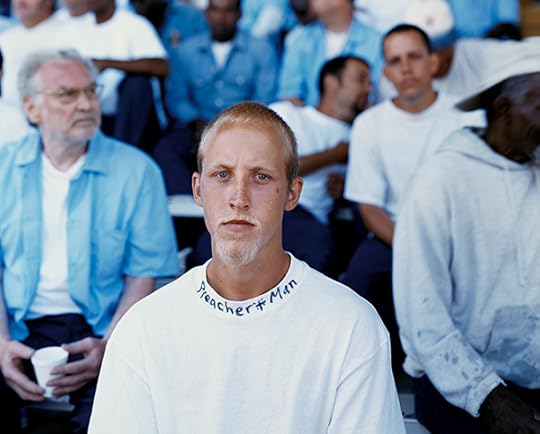

Alec Soth, Patrick, Palm Sunday, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Aaron Schuman: To start, what’s it like for you to revisit Sleeping by the Mississippi today, thirteen years after it was first published?

Alec Soth: I’ve been in the process of looking back for some time now—not just to Sleeping by the Mississippi, but to my original motivations for getting into photography. As I’ve gotten older, and also as commerce has come into play, my relationship to the medium has changed; it’s so easy to get jaded. So, recently, I’ve been investigating those primal feelings that I had at the start. Reprinting this book made me think about the time when I first fell in love with the medium, but had also reached a certain level of competence; that’s the sweet spot. I’ve talked with many people about photographers’ first books—I think that what often makes them so strong is the photographer’s newness mixed with a certain amount of attained skill, but still without knowing too much. For a long time after making Sleeping by the Mississippi, I didn’t look at it because I just saw its flaws. But now I get that the flaws—or its naïveté—were essential to my passion at the time.

Schuman: Could you talk me through an example of a “naïve flaw” within Sleeping by the Mississippi?

Soth: As you can imagine, I’m still reluctant to point flaws out, but there are all sorts of things. For example, there’s one image of a hospital bed in a house, and too many things are perfectly placed within it. I had a tendency to fill up the picture and overdo it. That particular photo was made in a peculiar little town. I saw this amazing house, and then I saw the eerie hospital bed. It was one of those magical experiences that speaks to that primal feeling of photographers when they’re starting out, to the adventure of it. At the time, I didn’t have a career or this big identity as a photographer, so I was almost making sculptures and then photographing them; I was moving stuff around, playing in that space; there was a joyousness to it. But as a picture that eventually became part of a photobook with a quasi-documentary vibe, it’s kind of problematic. I wouldn’t do it that way now; maybe I’d strip things away and leave the bed itself. Also, beneath the bed in that picture there’s a hole in the floor; I love that. Today I might let that hole exist on its own.

Alec Soth, Kym, Polish Palace, Minneapolis, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Obviously you can’t change the photographs themselves, but in reprinting a book there’s the opportunity to revise or “remaster” it in various ways, retrospectively. Yet in the new MACK edition, you’ve remained relatively true to the original.

Soth: This book has a peculiar little history. The first edition was done with Steidl; I loved the cover and everything else—it was perfect. We thought about reprinting it as a soft-cover trade edition, but for whatever reason we moved back to hardcover, and put a more commercial picture on the front—the one of Charles holding the airplanes—which in retrospect was a mistake. Nevertheless, that sold out quickly so we decided to do a third edition, but by then it felt like cheating to go back to the first cover, so I figured we should keep using different images on the cover. Then that edition sold out, things kind of stalled, I moved on to a different publisher, and the book stopped being reprinted. Years passed, and I occasionally thought about reprinting it again, but felt that it should probably coincide with the twentieth anniversary or whatever. Then last year, Michael Mack suggested we do it again, and I thought, Why not—let’s just do it and make it available. But there wasn’t any particular reason to do it, so I figured we could finally reprint it like the first edition: same essays, sequence, no changes. Then gradually, tiny little tweaks happened. At some point I decided to put one new picture in, at the beginning of the book. Originally, I’d made some photographs at the headwaters of the Mississippi, but even in 2004 I didn’t like them, and using one of those would have been a very obvious way to start the book. When I looked at my pictures again recently, I stumbled across a photo that’s not of the headwaters but looks like what the Mississippi might have been before mankind. In 2004, that picture wasn’t usable, because the first edition was made entirely from contact prints, and this particular image had vignetting in the sky. But today I can take the vignetting out digitally, so I introduced it into the new edition, before the title, and it really changes the feeling of the book. I liked the idea of starting the book with this very primal picture.

Alec Soth, Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, 2004, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: You’ve also made a slight change to the back cover of the new edition, incorporating a picture that depicts the Mississippi River. In the past, you’ve explained that you were reluctant for the book to be interpreted as a project literally about the Mississippi—the river was one underlying thread that tied it all together, but it wasn’t the focus. So it’s intriguing that both the newly added image—the “primal” landscape—and also the back cover are introducing the river back into the work.

Soth: It’s true. After Sleeping by the Mississippi I did Niagara (Steidl, 2006), and in that book I showed Niagara Falls a number of times. I’ve thought that if I did Sleeping by the Mississippi now I’d probably make more river-related pictures, which totally contradicts what I often say about it not being about the river, but I just think I’d have that impulse.

Schuman: You’ve added another new image at the end of the book—a picture of a large ball of twine in the corner of a room that’s been roughly stripped of its wallpaper.

Soth: I really love that picture, and regretted not including it in the first edition. But there’s always the page-count situation, which is something many readers may not consider: because of the way the signatures work within a book, you can only have a certain number of pages. Practical things like this came into the process of editing back then as well. But I have a real affinity for that picture. To me, so much of Sleeping by the Mississippi is about being creative in a modest way. I love thinking about someone collecting string, making this ball, and getting creative satisfaction from wrapping it larger and larger.

Alec Soth, Green Island, Iowa (Ball of String), 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: You just mentioned how the practicalities of bookmaking often come into play when making various creative decisions. In returning to this book, what other aspects of this were you reminded of?

Soth: What was crazy about the first edition of Sleeping by the Mississippi was how fast so many major decisions were made. Originally, there were spreads with two pictures on facing pages, and at the very last minute I changed my mind, deciding to go with one image per spread; the original cover was decided upon very quickly; and so on. All those little decisions affected the book, so that’s something that I’ve kept in mind with other projects. It’s dangerous to work something to death, and sometimes—like when you make spontaneous choices photographing—you have to make spontaneous decisions when it comes to the edit and design of a book, in order to give it energy. That can be risky, and you make mistakes. I’ve made many mistakes in the past. But even with something relatively minor, like the addition of two pictures—I could fret over it for months, and ask hundreds of people if it works or not. But sometimes it’s fun to roll the dice and see what happens. Every decision comes into play. In the new edition, the color of the endpapers is different than in the original, and even something as seemingly minor as endpapers really helps give feeling to the book.

Schuman: The new edition’s endpapers are burnt orange, rather than the original white.

Soth: Exactly. An endpaper can give you this splash of color that introduces a subtle mood. One of the things that I learned early on as a photographer was that I knew nothing about design. So when it comes to a decision like that, I’ll ask them to suggest options. That burnt orange was one of the colors that MACK suggested, and it sets the mood perfectly. I haven’t lived with it very long, but I can already tell that it’s affecting my feeling for this edition: it’s like when filmmakers tint their film slightly amber, or how the music that plays while the credits are rolling subtly affects the feelings you carry with you when you leave a movie theater. The endpaper, in this very subtle way, gives this suggestion of feeling.

Alec Soth, Mother and daughter, Davenport, Iowa, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Speaking of tint, when I looked at the first edition and new edition side-by-side, I noticed that there was a hint of warmth in the printing of the first edition, whereas the photographs in the new edition have a slightly crisper, more neutral feel.

Soth: There are a couple of factors there. Firstly, the paper has shifted; the original paper had whiteners in it that gave it more pop, but these yellow over time, particularly on the edges. To be honest, I can’t really tell how much of it is yellowing versus the tone of the original printing anymore—but yes, in the new edition we did try to correct this, and the pictures probably look a bit cooler overall. Plus, I see color differently now and have a better sense of printing. Also, the technology has changed in epic ways. I’m not an expert in printing by any means, but technological changes always come into play—even that stuff about optical whiteners, which I don’t really understand, keeps changing. And of course, there have been nine billion changes in terms of scanning and so on. So I mean, if Stephen Shore makes a new print of a 1970s image today, is he going to make it super-yellow? No. Don’t get me wrong—I might love the first edition of Robert Adams’s Summer Nights, and originally fall in love with the richness of all of the blacks; and then it gets reprinted, and all of a sudden it’s on nicer paper, and there are new details in the shadows. I still love the first one because my heart fell in love with it, but I also know how the new one is better. So, I would never reprint something poorly on purpose—and by no means am I saying the Sleeping by the Mississippi was poorly printed in the first case, which it definitely wasn’t—but changes happen, and like everyone I roll with them.

Schuman: When Sleeping by the Mississippi was released, it rapidly gained momentum and quickly became an established part of the “canon” of both photobooks and photography at large. What was that experience like for you?

Soth: It was totally unexpected, and I still don’t think it makes any sense. There was just no reason for it to become such a big thing. In a funny way, if it were to be published for the first time right now—because of Trump, Middle America, and all that—I could see why it might resonate. But back then there was no particular reason for it to become so huge; it still seems arbitrary and baffling. That said, I’m really happy that it was that book, because it is so profoundly connected to my basic impulses. Like the picture of Charles holding the airplanes—I’m so glad that’s my best-known photograph, firstly because I like it, and secondly because it’s about all of the things I’m still interested in.

Alec Soth, Charles, Vasa, Minnesota, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: Given the current issues in America that you mention—Trump, Middle America, etc.—do you feel like this book has taken on new meanings, or could evoke a sense of nostalgia?

Soth: The problematic part of talking about politics in relationship to this book is that I’ve always been a big defender of Middle America, saying that it’s far more interesting and complicated than people give it credit for. But I’ve become a little skeptical, sometimes thinking, Was I an idiot? Was I super naïve? Partly it’s because I haven’t been traveling in that part of the world very much in the last year, so I’m out of touch with real human lives, and am getting too much information from TV and media coverage. In terms of “nostalgia,” 9/11 is the ultimate turning point in terms of “before” and “after” in my life, and I’m genuinely nostalgic for pre-9/11. A lot of the pictures in Sleeping by the Mississippi were made before 9/11, and many were taken after, so it crosses that threshold. It’s not so much that I’m nostalgic for that time in history, but as a photographer it was exciting to be making something back then, and in making this new edition I’m able to feel it all again.

Schuman: Speaking of which, you’ve removed only one picture from the original edit—a snapshot of you standing on a ladder behind an 8-by-10 camera, with your head buried underneath a dark cloth, in the midst of a snowy field.

Soth: That picture was made at the beginning of my biggest trip for that project, probably around 2001, and was taken with a very early digital camera. Someone was driving by and they pulled over, wondering what was happening. So I went up and talked to them, and then said, “Hey, would you mind taking a picture of me with this camera?” and they took that picture. But the original digital file is long gone, so part of the issue with reprinting it was that we couldn’t find the file.

Alec Soth, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2002, from the book Sleeping by the Mississippi

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Schuman: But surely you could have scanned it from one of the book’s earlier editions?

Soth: Okay—as you well know, I’ve always been kind of embarrassed about that picture. But in my defense, there were two points to it. First, in a lot of photobooks from the 1970s you’d have this page where the photographer would list all of their technical information—what kind of camera they used, what film, what lens, etc.—and for a young photographer it’s the best, because you get all of that technical information, and you also get to imagine what it’s actually like to take the pictures. Second, there’s that picture of Joel Meyerowitz on the back of Cape Light, where he’s standing next to his 8-by-10 camera with his shirt off—I love that picture. So I think that’s what I was trying to do with that picture in the original version of Sleeping by the Mississippi. I could have kept it in this time around, but I couldn’t stomach it. I was self-conscious about putting it in again thirteen years later; I guess not being able to find the original file provided a good enough excuse to get rid of it.

Schuman: Considering all that’s happened to you since Sleeping by the Mississippi was first published, is it strange for you to look back at that anonymous, “naïve,” “passionate” kid standing on a ladder in the cold, entirely focused on trying to make a good picture?

Soth: That’s the thing about the release of this new edition—I’m currently in the thick of thinking about my earliest photographic impulses, and have been consciously trying to get back into that headspace. So the timing is quite good. When I was first making Sleeping by the Mississippi, I’d reached a point where I thought, No one cares—I can just do what I want, and it doesn’t matter. And lately, I’ve taken a period of time to just do whatever I want, even if that means making sculptures or doing sound pieces. They may never see the light of day, but I’ve given myself the space nonetheless. That’s the feeling I’m after, and that’s what Sleeping by the Mississippi represents to me. Apart from how it got out into the world, the actual shooting of that book had this incredible fairy dust all over it; it was magical and filled with the best luck. I now know that photography isn’t always like that, so this book is still a very special thing.

Aaron Schuman is a photographer, writer, lecturer, and curator. He is the author of FALLING (2017) and FOLK (2016), senior lecturer at the University of Brighton, and course leader of MA Photography at UWE, Bristol.

The post Alec Soth Revisits His Legendary First Book appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers