Aperture's Blog, page 102

April 25, 2018

Truth and Reconciliation

What does it mean to confront the history of racial violence in the United States? In a wide-ranging conversation, Bryan Stevenson and Sarah Lewis discuss images, power, and justice.

Bryan Stevenson at the office of the Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, Alabama, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

A visionary legal thinker, Bryan Stevenson has protected the rights of the vulnerable through his work as a death-row lawyer. With the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an organization he founded in 1994, Stevenson has made strides to end mass incarceration and challenge racial and economic injustice. He has argued cases before the Supreme Court, recently winning a watershed ruling that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for children seventeen and under are unconstitutional. Stevenson’s 2014 memoir, Just Mercy, recounts his experiences navigating an unfair criminal justice system.

But his work extends beyond the legal realm—Stevenson is invested in shifting cultural narratives and making history visible. This is work to which Harvard professor and art historian Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture’s 2016 “Vision & Justice” issue, is uniquely attuned. Lewis has written at length on the urgent role of art in social justice, on the corrective function of images and how they enable us to reimagine ourselves. Last October, Lewis visited Stevenson at his office in Montgomery, Alabama, for an extended conversation. Central to their discussion were Stevenson’s next projects: on April 26, 2018, he will open the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, which will honor the lives of thousands of African Americans lynched in acts of racial terrorism in the United States, and the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, which will trace a historical line between slavery, lynching, segregation, and mass incarceration. Of his work, Stevenson remarks, acts of truth telling have a visual component. “If we just go to the public square and people say some words, it doesn’t have the same power.”

Sarah Lewis: It’s a rare privilege to be able to talk with someone doing work in the realm of justice who understands the role of culture for shifting our narratives regarding racial inequality. I want to have a conversation about how culture, specifically photography, has shifted national narratives on rights and race-based justice in the United States.

Bryan Stevenson: Yes.

Lewis: To begin, I would say that we must consider the journey from 1790 with the Naturalization Act, when citizenship was defined as being white, male, and able to hold property, to the present-day definition of citizenship. The question becomes: Is this journey a legal narrative or is it also a cultural one?

Stevenson: Absolutely.

Lewis: You’ve spent a lot of time dealing with this history as it relates to emancipation and slavery, up until the current day. How did you arrive at a place of seeing the importance of culture for getting people to understand this work?

Stevenson: When I first started going to death row in the 1980s, I was constantly seeing things that communicated really important truths about the experience of the men and women I was meeting in these desperate places. You would see people interact with each other, constantly sharing gestures of compassion and love and support. You’d witness people acting in ways that were so human. And yet they were being condemned, in large part, because there was a judgment about their absence of humanity.

To counter the unforgiving judgment, I wanted other people to see what I saw. And, if anything, it was through the experience of being in jails and prisons, year after year—seeing this rich humanity and the redemption and transformation of individuals, despite the harshness of the environments—that I became persuaded that if other people could see what I see, they would think differently about the issues presented in my work. So, in the 1990s, when we first started representing our work in a modest way, images became an important part. In our first report we used a picture of the Scottsboro Boys. And we also used a picture of a client with compelling features who had been on death row for twenty years. For me, it has always been clear that there is a way in which photography can illuminate what we believe and what we know and what we understand.

It led me to increasingly use imagery to try to help tell the story of our clients. After twenty years of doing that work—and we had a lot of success, but we also saw the limits—I became aware that the rights framework, the insistence on the rule of law was still going to be constrained by the metanarratives that push judges to stop at a certain point: the environment outside the court. That’s what pushed me to think more critically about narrative, not just within a brief, within a case, within an action, but more broadly. And when it comes to narrative struggle, there is nothing that has been more confounding than racial inequality.

Soil from Alabama lynching sites, collected as part of EJI’s Community Remembrance Project, Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, Alabama, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

Lewis: There’s much work happening in the arts around the nexus of art, justice, and culture. But you’re doing the work of having this become more understood in the wider realm. It’s so crucial. Something that I asked myself as I began this work was: What is the connection between culture and justice? This piece about “narrative” is what unlocks that.

Stevenson: That’s absolutely true for me. Because in many ways, our inattention to narrative is what has sustained the problems we’ve tried to overcome.

Lewis: Yes. Inattention and also unconscious conditioning by it.

Stevenson: Absolutely. So if we think differently about what happened when white settlers came to this country with regard to native populations, if we actually identify what happened to millions of native people as a genocide, the word genocide introduces something into the narrative that is quite disruptive. We’ve been hesitant to use the word genocide, because the narrative would shift in really powerful ways if we understood the violence and exploitation of native people through that lens.

I think the same is true when you look at the African American experience in this country. I’ve gotten to the point where I believe that the North won the Civil War, but the South won the narrative war. They were able to hold on to the ideology of white supremacy and the narrative of racial difference that sustained slavery and shaped social, economic, and political conditions in America. And because the South won the narrative war, it didn’t take very long for them to reassert the same racial hierarchy that stained the soul of this nation during slavery and replicate the violence and racial oppression that existed before the great insurrection.

It’s the narrative of racial difference that condemns African Americans to one hundred years of segregation, exclusion, and terror, following emancipation. Had we paid more attention to the narrative, we would not have seen the U.S. Supreme Court strike down all of those acts by Congress in the 1870s that were designed to protect emancipated black people and create racial equality. But the Supreme Court embraced the narrative that basically maintained that black lives are not worth risking further alienation of the South. It wasn’t about law for the court. The law said that we were all equal, but the narrative allowed the court to accommodate inequality and racial terror.

Narrative struggle is where we have to pay attention if we want to avoid replicating these dynamics as we continue to face the same problem of racial divide.

Memorial plaque to the Montgomery slave trade, placed by the Equal Justice Initiative, October 2017

Photograph by John Edmonds for Aperture

Lewis: On this point about looking at the ways in which whiteness became conflated with nation through narrative, there are a number of things to mention. But just to get back to the Native American piece and the criminalization of rights-based action, it was, in large part, photography that legitimated acts of genocide. Edward Curtis’s photographs, for example, naturalized and supported the genocide.

Stevenson: That’s right. Because if you can create the idea that these native people are savages and you can create a visual record that supports that idea, then people don’t view the abuse and victimization as they ought to.

What’s interesting to me about some of that early art and visual work is that it’s really about perpetuating the politics of fear and anger. And fear and anger are the essential ingredients of oppression. Art is complicit in creating these narratives that then allow our policymakers to perpetrate acts of injustice, decade after decade, generation after generation.

Lewis: Absolutely. But before we get more to the current day, I think there is a framework here that we should acknowledge, and a thinker who did the courageous work at the time, during the Civil War, to put out this idea about narrative—and that is Frederick Douglass. He gave a speech during the Civil War that he called “Pictures and Progress.” He confused his audience at the time by speaking about what seemed like a trifle during this nation-severing conflict. Something seemingly as small as a picture, he argued, could have as much force as a political action, as a law. It’s a fascinating speech. He was interested in what he called “thought pictures.” This was his gesture toward narrative; he used this term to describe the ways in which culture, what we consume daily through pictures, can shift our notion of the world. That is what he thought would effect the change. Douglass was the most photographed American man in the nineteenth century, for good reason. He believed in this idea.

Stevenson: It’s a really powerful insight, that he could appreciate how getting people to see his humanness was critical for them to understand the inhumanity and degradation of slavery. In many ways, Dr. King had that same insight.

Lewis: Yes.

Stevenson: He understood that the spectacle of nonviolent resistance to white, armed, military repression could create a consciousness about the African American struggle in the South that could not be created any other way.

As we’ve been working on our Legacy Museum, which explores slavery and the human suffering created by the domestic slave trade, it’s been frustrating, because there is so little photography or imagery that exposes the inhumanity of enslavement. It’s almost as if there was a real effort to avoid visual documentation that might have implicated us and revealed our complicity in facilitating such great suffering.

I have found in the published narratives of enslaved people this unbelievably rich source of content, not visual in the sense of photography or art, but visual in terms of language. They tell stories. They use the narrative form to create a very intimate picture of what it was like on the day when their children were taken away on the auction block, or when they lost their loved ones. In our museum, we’re using technology and video to give animation to these words through performance. I’m really excited about it because it creates a kind of intimacy, it paints the kind of picture that Douglass tried to achieve.

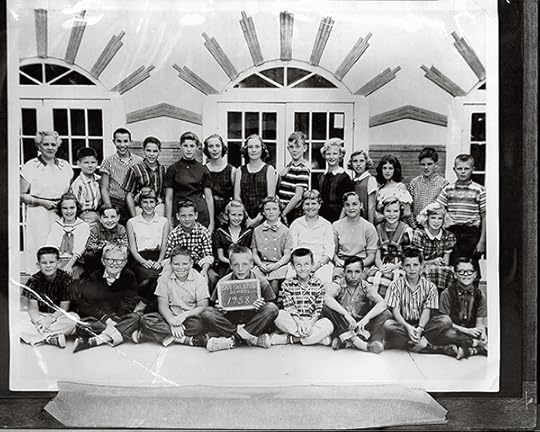

Charles Moore, Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested for loitering outside a courtroom where his friend Ralph Albernathy is appearing for trial, Montgomery, Alabama, 1958

Courtesy Charles Moore Estate and Steven Kasher Gallery

Lewis: We’re sitting here in a building in Montgomery that functions as a kind of narrative correction. Is that right?

Stevenson: Yes. We’re a few blocks from Dr. King’s church and from where Rosa Parks started the modern civil rights movement. However, what we didn’t appreciate until we began our racial justice project is that we were also in the epicenter of the domestic slave trade. That part of the historical narrative of this community had largely been ignored. But it became clearer to us that this street, Commerce Street, was one of the most active slave-trading spaces in America. Tens of thousands of enslaved people were brought here.

Lewis: Hence the name.

Stevenson: Yes, that’s right, hence the name. Thousands of black people were trafficked here by rail and by boat. Montgomery had the only continuous rail line to the Upper South in the 1850s.

So this knowledge made me reimagine how this space could contribute to a more honest American identity. And the marker project was the first thing we did locally, to try to create awareness of this past. If you come to Montgomery, there are fifty-nine markers and monuments to the Confederacy in this city. They are everywhere. “The First White House of the Confederacy” is the sign you pass when you drive into town. Our two largest high schools are Robert E. Lee High and Jefferson Davis High. But not a word about slavery. So putting up these markers that introduced facts about the Montgomery slave trade and the domestic slave trade and the slave warehouses and the slave depots that shaped this city, which were avoided by local historians, was really important.

Lewis: You talked about the need to shift our cultural infrastructure in the United States because of the deliberate silence about racial terror, and, of course, this connects to mass incarceration. But can you talk about the shifts that you’re hoping will occur in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the museum in Montgomery?

Stevenson: I do think we have to make our history of racial inequality visible. We have been so inundated with these narratives of American greatness and how wonderful things have been in this country that it’s going to take cultural work that disrupts the narrative in a visual way to force a more honest accounting of our past. People take great pride in the Confederacy because they actually don’t associate it with the abuse and victimization of millions of enslaved black people. So that has to be disrupted.

What appeals to me about the markers is that they are public; everyone encounters them. We can create a museum. We can create indoor spaces that try to express and deal with these issues. But a lot of the people who need this education are never going to step inside those places. Public markers, however, can’t be ignored, and we have continued that effort with our work on lynching. Our goal is to mark as many of the lynching sites in America as possible. We use the words racial terrorism on each one of the markers. We name the victims. We give a narrative that contextualizes the brutality and torture black people endured. I do think that’s important, to challenge the public landscape, which has been complicit in sustaining these narratives of white supremacy and racial inequality. That’s another way in which acts of truth telling have a visual component. If we just go to the public square and people say some words, it doesn’t have the same power as permanent symbols of collective memory.

We are opening the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, which will acknowledge over four thousand victims of lynchings and identify over eight hundred counties in America where racial terrorism took place. Hundreds of six-foot monuments will be on the site, including sculptures created by artists who contextualize lynching within an understanding of slavery, segregation, and contemporary police violence. Deeper exploration of these issues is then possible in the museum, and all of this, for me, is really exciting. Particularly in these political times where you’ve seen the retreat and obfuscation of historical truth. It was a shock to me in 2008 how quick people were to assert that we now live in a postracial society; that was obviously incredibly naive.

Photographer unknown, An airman pauses to examine the “Colored Waiting Room” sign at

Atlanta’s Terminal Station, January 1956

© Bettmann/Getty Images

Lewis: It occurs to me, and I wonder if this is correct, that you focused on your own experience of needing narrative to communicate what you were seeing with your clients—how racial terror and lynching have structured the criminal justice system and the landscape of racial inequality.

Stevenson: Yes, absolutely. It’s not a surprise that after emancipation, people went from being called “slaves” to being called “criminals.” Convict leasing and lynching were about criminalizing black people. Rosa Parks makes her stand, and she’s immediately criminalized. Those women who fought for equality on buses here in Montgomery, what they were being threatened with was a formal designation as criminals: Claudette Colvin, Mary Louise Smith, all of these women.

The notion that resistance to racial inequality makes you a dangerous criminal has always been there. So, then, it’s not a surprise that after the success of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, prosecutors begin focusing on “voter fraud” in the black community, followed by this new War on Drugs, which then leads to the United States having the largest incarcerated population in the world. The rate of incarceration is just unprecedented.

I think that the criminalization of black people, and now brown people who are deemed illegal because of their state of national origin, is very much a part of the American story, and it’s been present with us in ways that we just haven’t acknowledged. We criminalized Japanese Americans during World War II and put them in concentration camps, but were unconcerned about Italian Americans and German Americans.

Lewis: One of the interventions of the civil rights movement, it seems, is to reframe criminality and rights-based behavior as actually a positive, an act of citizenship.

Stevenson: Right.

Lewis: Or as an indicator of such. The 1958 image that Charles Moore took of Dr. King is probably iconic in that regard.

Stevenson: Right. We used that for one of our calendars. I think the images we often see of Dr. King are with him poised, speaking in front of thousands of people in these esteemed spaces, where his leadership is what’s being highlighted. What’s powerful to me about this image is that here he is being criminalized. He’s being brutalized by law enforcement. And there is some fear in his eyes, because there is the uncertainty of what will happen. Because the long history of black struggle is that once you are put in this criminal status your survival is not guaranteed, your safety is certainly not guaranteed. And yet, he persists, and he continues. I love the way Coretta Scott King is witnessing his abuse with such dignity and confidence. It just says a lot about the kind of courage that is needed to fight a fight like this.

Rosa Parks is also so powerful in that regard. One of the first people we want to honor in our memorial garden is Thomas Edward Brooks, a black World War II veteran who shaped Rosa Parks’s activism on the buses.

In 1950, Mr. Brooks returned home to Montgomery, in his uniform. The segregation protocol on the bus was, of course, that you get on at the front of the bus, you put your dime in, then you get off the bus, and you walk to the back door, and get back on, and head to the back. Mr. Brooks gets on, puts his dime in, but he doesn’t get off the bus. He walks down the center aisle to the back. The bus driver is screaming at him and calls the police. The police officer comes on the bus, and Mr. Brooks is in his military uniform in a defiant posture, according to witnesses. The police officer just goes up and hits him in the head with the club, knocks him down, rattles him, and he starts dragging him toward the front of the bus, and when he gets to the front of the bus, the black soldier gathers himself and jumps up and shoves the police officer and starts running, and the officer takes out his gun and shoots him in the back, and kills him.

Two years later, the same thing happens to another black soldier. Rosa Parks was the person who was documenting these tragedies, as a secretary to the NAACP. And that sense of violent repression and menace—the understanding that police officers could kill a black soldier, shoot him in the back—took her commitment to change conditions to a whole other level. It was no longer just insult and subordination. It was lethal, which makes her protest all the more inspiring.

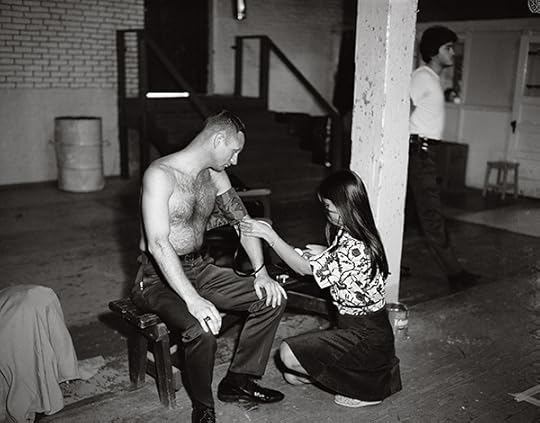

Chandra McCormick, Young Man, Angola Prison, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Lewis: Your work allows us to understand the narrative of black veterans and the way they were targeted and subjugated to racial terror. It’s a feature of the landscape that we need to understand.

Stevenson: Well, it’s an important part of the story, because, you know, W. E. B. Du Bois and others said, We go fight for this country; let’s save this country, and then they will save us. And it didn’t happen after World War I. In fact, it was the opposite. They were targeted and victimized for their military service. It complicated the idea of black inferiority to have black soldiers go to Paris, France, and be triumphant and successful. That’s why, in some ways, the lynchings increase during this time, in 1919, 1920, 1921, when black soldiers are returning home and creating a new identity. The same thing happens after World War II; you see this increased racial violence in the 1940s targeting black veterans.

My dad just passed away. He was born in 1929, and he fought in the Korean War. He was very active in the church, and he talked about his faith all the time, but he never talked about his military service. For economic reasons he wanted to be buried at the veterans cemetery, and there you see all of these U.S. flags, and there’s all of that symbolism of nationalism and American pride. When I got to his grave site, they put on the little plate, “Howard C. Stevenson, Corporal, U.S. Army, Korean War,” and a flag. But it wasn’t completely true. He served in a racially segregated unit and was denied most of the rewards white veterans received for their military service; his rank and service were diminished by racial bigotry. And there is no acknowledgment of that. I believe his willingness to serve despite racism should be recognized. For me, this highlights how much work we still need to do in this country around truth telling. I believe that truth and reconciliation are sequential. You have to tell the truth first. You have to create a consciousness around the truth before you can have any hopes of reconciliation. And reconciliation may not come, but truth must come. That’s the condition.

Lewis: If someone were to say that we’re having a conversation about culture and mass incarceration or racial inequality, they might think that it’s about the portrayal of that specific group that has been terrorized or dehumanized by these actions. But, in fact, it’s also about the opposite, the way in which the presence of racial terror has also conditioned the entire population.

Stevenson: Absolutely. That point is so critical. Terrorism, the violence of lynching, is critical for understanding how you could have decades of Jim Crow. No one would have accepted drinking out of the inferior water fountain or going into the less desirable “colored” bathroom unless violence could be exercised against you for noncompliance with segregation with impunity.

Racial-terror lynching propelled the massive displacement of black people in the twentieth century. The idea that black people went to Cleveland and Chicago and Detroit and LA and Oakland as immigrants, looking for economic opportunities, is really misguided. You have to understand that they went there as refugees and exiles from terror and lynching.

Today we have generational poverty and distress in urban communities in the North and West, and black people are criticized for not solving these problems, and most people don’t understand how the legacy of racial terror shaped the structural problems we continue to face. That’s what provokes me when people come up to me and they talk about problems in the black family. I’m thinking children and their husbands and their parents by white slave owners, and the commerce of slavery. During the lynching era, black women had to send away spouses and children who were threatened with mob violence for something trivial. We haven’t addressed the devastation and trauma to black family life created by this history.

Chandra McCormick, Line Boss, Angola Prison, 2004

Courtesy the artist

Lewis: I’m looking at the EJI report “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The photographs demonstrate that watching a lynching was a family activity for some white Americans.

Stevenson: That’s exactly right. And this effort to acculturate white people to accept and embrace the torture, brutalization, and violence they see black people around them experience … it’s a tragic infection that afflicts our society. Nelson Mandela says, in effect, “No one is born hating someone else; you have to be taught.” The way in which we have taught racial violence and white supremacy is intricate, and devastating. It won’t go away without treatment.

Lewis: Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun’s work Slavery: The Prison Industrial Complex, begun in the early 1980s and ongoing to this day, shows the continuation of this violence through photographs of life at Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Stevenson: We represent lots of people who are at Angola now. Angola has one of the largest populations of children sentenced to life imprisonment without parole in the country. We have clients who received write-ups for not picking cotton fast enough in the 1980s when prisoners were forced to toil in the fields. Now these men are parole-eligible, and we have to explain to the parole board why refusing to pick cotton thirty years ago is not something they should hold against this person when they were sentenced to die in prison. You still have officers on horseback down there, riding around. You still see men going out into the fields. It is a former plantation.

So I think images are really important. The narrative of putting imprisoned, largely black people out in the fields to hoe and pick cotton, which you would think would be just unconscionable to a society trying to recover from slavery, is actually exciting to a lot of people. It’s like the chain gangs they brought back to Alabama twenty years ago. Some people loved the visual of mostly black men in striped uniforms chained together along the roadside and being forced to work. The optics are so important, and it sort of reminds me of those images around lynching. It’s the same thing: Let’s use this imagery to excite the masses so that we can recover something that has been lost, restore something that has been taken from us, and allow us to reclaim an identity that replicates the good old days of racial hierarchy in precisely the same ways. It’s why the phrase “Make America Great Again” is provocative to many of us, and why our indifference to mass incarceration is so unacceptable. I’m persuaded we are still in a struggle for basic equality and there is much work still to be done.

Sarah Lewis is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University and the author of The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery (2015).

Read more from Aperture Issue 230 “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Truth and Reconciliation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 20, 2018

India Takes Houston

From colonial legacies to gender politics, FotoFest tackles photography from the country and its diaspora.

By Michael Famighetti

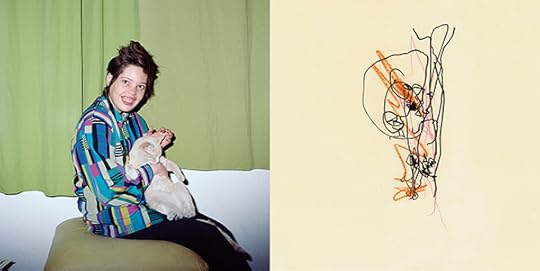

Anoop Ray, Untitled, October 2011, from the series Friends and Their Friends, 2010–15

Courtesy the artist

Founded in 1983, Houston’s FotoFest has since offered global takes on contemporary and historical photography. Its globetrotting founders, Wendy Watriss and Frederick Baldwin loosely modeled the festival on the Rencontres d’Arles, the venerable, rosé-soaked photography festival and “meeting place” held annually in the idylls of southern France. By contrast, FotoFest set up shop in energy-rich, zoning-free Houston (the only French here might be the concept of laissez-faire) and established itself by taking deep dives into capacious themes: a recent edition took on the environment, while past iterations have delved into the photographic cultures of particular geographies—such as Latin America, Russia, and the Middle East and North Africa—to highlight image makers unknown in the United States.

This year’s edition, curated by photographer Sunil Gupta alongside Steven Evans, the festival’s current executive director, takes an expansive look at recent photography from India and its diasporic communities. The festival, titled India: Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, features forty-seven artists and is staged across multiple venues throughout the sprawling city, which is home to a number of top-flight arts institutions (notably the Menil Collection and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which is concurrently staging a Raghubir Singh retrospective). One standout venue is a monumental converted rice packaging facility, recently converted to artist studios, with soaring eighty-three-foot-tall silos that bear the word “Success” in colossal lettering. Another group exhibition is installed at the elegant Asia Society Texas Center, designed by architect Yoshio Taniguchi.

Sandip Kuriakose, Untitled, 2017, from the series It has the Appearance of a Deliberate Transgression

Courtesy the artist

While some artists might resist having their worked framed by geography, curator Sunil Gupta, in his catalogue essay, lays out the open-ended motivating questions that underpin his selection of works: “How do contemporary photographers and artists of Indian origin imagine the diverse and complicated subjectivities of Indian-ness regardless of where they live? How do they talk back to photographic history that has remained Eurocentric for over a century and a half? How do they absorb the legacy of colonial anthropological photography where the photographs depict their own ancestors?” Gupta also questions what it means to speak of Indian photo history versus global photo history. Is there a need for separate regional histories? Or do global histories—usually written from a blinkered Western vantage—need to do more work to recognize that other histories of photography exist? Both, of course, are necessary. Also challenging for the country’s contemporary photographic culture, Gupta notes, is the dearth of institutions teaching photography, building archives, and creating a critical framework for thinking about pictures.

Even so, through a range of photographic styles and media (all work is made post-2000), the featured photographers delve into a host of ideas—legacies of colonialism, gender politics, identity performance, the caste system, environmental degradation, ethnic violence, growing inequality, and life in the diaspora—and make clear that representations of India, the second most populous country in the world, must reflect the immense diversity and complexity of the place itself.

Rishi Singhal, Farrukhabad 01, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2007, from the series A River Story

Courtesy the artist

Rishi Singhal

For more than a decade, Rishi Singhal has photographed along the Ganga (Ganges) River. His aim has been to capture life in the communities along the banks of the river. Framed by sublime views of the majestic Himalayan mountains and the Bay of Bengal, his images capture the tension between human settlements and the natural world.

Pushpamala N. with Studio Harcourt, The Slave and her Slave (After Ingres), 2009, from the series The Harcourt Set

Pushpamala N.

Among the most internationally recognized artists on view is Pushpamala N. Her project The Harcourt Set (2009) was commissioned for a show at the Centre Pompidou, Paris. For this work, the artist collaborated with the famous Studio Harcourt—known for its polished photographs of film stars—to recreate iconic images from nineteenth-century France.

Tenzing Dakpa, Arrival, 2016, from the series The Hotel

Courtesy the artist

Tenzing Dakpa

Tenzing Dakpa’s series The Hotel, shot in high-contrast black and white, is based on his family’s own hotel and his hometown of Gangtok, Sikkim. Playing on themes of cultural displacement—Dakpa is a second-generation Tibetan who moved to New Delhi and then to the United States, where he studied at the Rhode Island School of Design—he enacts an oblique narrative of his family as they move through the daily motions of hotel upkeep, performing memories of what the artist describes as a “temporal existence introducedby migration.”

Sandip Kuriakose, Interested, 2017, from the series NPNR

Courtesy the artist

Sandip Kuriakose

Kuriakose’s work takes on photography as it operates in digital space, delving into the language of images posted to gay dating sites, which become both a means of communication and a performance of identity.

Vidisha Saini, Mr. Shekar House, 2012, from the series Mr. Shekar

Courtesy the artist

Vidisha Saini

A highlight of the festival is Vidisha Saini’s installation of inkjet prints on newspaper, which have the subtle palette of watercolor. The project, You Like Mr. Shekhar, hones in on the story of Hampi, a village in the state of Karnataka. Once the capital of the largest Hindu Empire, the village eventually became abandoned, before becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the 1980s. More recently, families living there have been relocated from the location to conserve the architecture. Saini’s installation—with vitrines of castaway objects, presumably from the families who have left—amounts to a form of archaeology on the part of the artist.

Gauri Gill, Untitled, 1999–2007, from the series Jannat

Courtesy the artist

Gauri Gill

Gauri Gill is celebrated for her 2012 photobook, BalikaMela, composed of deceptively simple yet poignant portraits of young girls at a fair in Rajasthan, Western India. At FotoFest, Gill’s series of forty-four gelatin-silver prints, installed sequentially in cinematic storyboard fashion, focus on the daily life of a young girl living in a Muslim settlement in a stark desert environment.

Anoop Ray, Untitled, March 2012, from the series Friends and Their Friends, 2010–15

Courtesy the Artist

Anoop Ray

Anoop Ray adds to photography’s longstanding diaristic tradition of dissolving barriers and turning the camera on those in one’s immediate circle—in this case, the intimate moments of his friend group.

Sohrab Hura, Pam “Oprah of the South” Chatman, the First Female African-American News Director in the State of Mississippi, Greenville, Mississippi, 2016, from the series The Levee

Courtesy the artist, Pier 24, San Francisco, and Postcards from America

Sohrab Hura

Sohrab Hura, who is based in New Delhi, traveled throughout the American South to make this body of work. He was originally motivated by images his father had made in the region, earlier on, when he had been employed as a sailor on a commercial ship. Hura plays with the idea of being an outsider, wandering a geography that is haunted by history and local stereotypes that he encountered on the other side of the world.

Michael Famighetti is the editor of Aperture magazine.

India: Contemporary Photography and New Media Art is on view in Houston, Texas, through April 22, 2018. Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, through June 3, 2018.

The post India Takes Houston appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 18, 2018

If Photographs Could Talk

How has an experimental platform for photographers created a new form of image making?

By Max Campbell

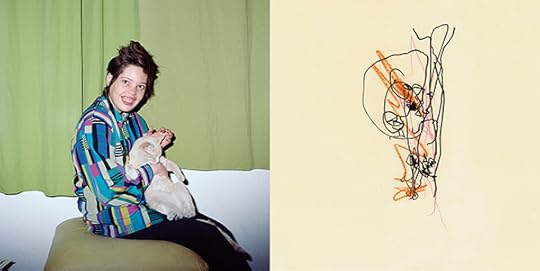

Eric Ruby (in conversation with Damien Maloney), February 17, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Damien Maloney (in conversation with Eric Ruby), March 20, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Peter Happel Christian (in conversation with Joy Drury Cox), October 23, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Joy Drury Cox (in conversation with Peter Happel Christian), November 8, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Jenia Fridyland (in conversation with Aya Fujioka), January 5, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Aya Fujioka (in conversation with Jenia Fridyland), January 31, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Arthur Ou (in conversation with Grant Yarolin), September 20, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Grant Yarolin (in conversation with Arthur Ou), October 5, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Corey Olsen (in conversation with David Brandon Geeting), September 15, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

David Brandon Geeting (in conversation with Corey Olsen), September 17, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Caroline Tompkins (in conversation with Ryan Lowry), September 20, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Ryan Lowry (in conversation with Caroline Tompkins), September 25, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Tag Christof (in conversation with Maggie Shannon), May 16, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Maggie Shannon (in conversation with Tag Christof), May 22, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Irina Rozovsky (in conversation with Mark Steinmetz), January 18, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Mark Steinmetz (in conversation with Irina Rozovsky), January 25, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

What does it mean to talk in photographs? In 2014, the photographers Ben Alper and Nat Ward started an image-based conversation, and they haven’t stopped talking since. A lot has come up in that time, and, through alternating contributions, their exchange has covered topics such as violence, fantasy, patriotism, nature, and death. The dialogue formed as an open-ended experiment, but they have stuck to the same format throughout: a photograph from one, a photograph from the other, repeat.

“It’s like an ‘exquisite corpse’ exercise, or the sequencing of a book of photographs,” Ward said recently. “The visual content has to talk from one image to the next, making and augmenting a legible kind of meaning along the way.” It didn’t take long for a compelling rhythm to emerge in Alper and Ward’s give-and-take, which stirred up curiosity about how other photographers might use pictures to talk. They invited friends to start conversations of their own and the project expanded outward from there. Today, A New Nothing, the website Alper and Ward created to house these exchanges, has over one hundred active contributors.

Mark Steinmetz, January 25, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

The parameters of the project are simple, but A New Nothing is full of layered and provocative interactions. A column of paired names works as the table of contents on the website, each pair cueing a gallery containing the back-and-forth between two photographers. Images are accompanied only by bare-bones captions that list the date the post went up and the contributing photographer’s initials. There are no statements or bios, and each exchange moves at its own pace (in some, weeks pass between posts).

The pattern of alternating posts established in Alper and Ward’s founding interaction unites the conversations. Otherwise, each duo develops the tone and guiding principles organically, as their discussion unfolds. “Those impulses and decisions remain largely hidden or unverbalized,” Alper said. If photographers decide they no longer want to continue participating the contributed work remains online in archived conversations (some of which Alper and Ward plan to release in book form in the future), but such end points are never established up front. Context and intention here are meant to evolve publicly.

Eric Ruby, February 17, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Sometimes, it’s easy to make out the connective tissue between individual photographs in the conversations. “Talking” often means making playful turns to echo and invert colors and shapes between pictures. In a photograph by Eric Ruby, someone has slung a friend over their shoulder to carry them down the beach. As a response, Damien Maloney shows us a snail atop a green melon; the tie-dyed striping on a T-shirt in Ruby’s picture has jumped to the melon’s skin in Maloney’s scene. When images are enlisted as responses and rebuttals, compositional elements might be mimicked repeatedly, until the original form dissolves, like an object fading into its own reflection between two mirrors, or a message getting garbled in that children’s game “telephone.” Certain subjects will appear and then travel between frames. In a conversation between Joy Drury Cox and Peter Happel Christian, we see flowers, wrapped and ready to be bought, then backlit on a windowsill, and, before the motif is abandoned, placed in vases affixed to headstones.

Peter Happel Christian, October 23, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

As subject matter and form are batted back and forth between two photographers, as if over a tennis net, stylistic choices take on a gestural quality. Because photographers get to choose whether to recognize, reject, or repeat elements in their partner’s picture, their aesthetic inclinations look a bit like character traits. Tracking the patterns, or the flowers, or the range of greens that bridge from a pack of pickles sprawled on a painted surface to a tree-shaped car air-freshener floating in some sludge, we see lots of clever ways to shift expectations.

We also see how talking in pictures, like any sort of conversation, reveals the interlocutors’ dispositions. Photographers whose work pulls from too expansive a palette, either aesthetically or in terms of subject matter, might seem scattered or ineloquent. On the other hand, sticking too closely to a subject, like when Arthur Ou posted only photographs of tree trunks in his conversation with Grant Yarolin, might make you look stubborn or obsessed.

Corey Olsen, September 15, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Many photographers appear liberated by the purpose (or purposelessness) of the format, which encourages a particular sort of uninhibited expression. Humor often results. One of Irina Rozovsky’s photographs was shot from the driver’s seat of a car on a snowy day. On the camera’s side of the windshield, a hand is pinching a hard-boiled egg between thumb and forefinger. A bite is missing from the egg and, outside in the slush, a bundled man is in the middle of the crosswalk. In response, Mark Steinmetz shows us a line of chickens crossing the road. Why? Because of the driver’s snack.

Grant Yarolin, October 5, 2016

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

“It’s this sort of prism of different places, different things, linked by something unspoken,” Rozovsky said of her conversation with Steinmetz. Their exchange began with two photographs of the same scene, taken in Athens, Georgia, in 2014, while Rozovsky was visiting Steinmetz. They were friends then and have since moved in together and had a child, continuing the conversation throughout. The exchange “loses a little bit of energy when you’re together, seeing the same things,” she said. “But it’s really fascinating when you’re in different parts of the world. The resonance of the echo across the divide is really exciting.” Methods for these visual interactions—the flipping, the mirroring, the inversion of ideas—have a give-and-take quality good for shaping everything from visual puns to the bridging Rozovsky describes.

Mark Steinmetz, January 18, 2017

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Divorcing these images from traditional sequence editing, accompanying text, and layout decisions creates a spare, fluid atmosphere where subjectivity swells. At the same time, there is this unspoken but apparent etiquette in each conversation on A New Nothing, and the tension between those aspects is part of what makes the project such an engaging trove. Messaging here rides entirely on the form and content within the frame, and the capacity of individual photographs expands in unlikely ways. We watch as it happens, guessing at what will be said next. All of this makes scrolling through the conversations feel like listening in on friends talking in the codes of inside jokes reserved for private spaces, or, as Ward said, “like reading the body language between two people at the other end of a bar.” The playfulness, the humor, and the challenges the conversations present have a way of deflating—rather refreshingly—the objective authority photographs so often assume.

Max Campbell is a writer and photographer based in New York.

The post If Photographs Could Talk appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Myth of Brazil’s Racial Democracy

In a new exhibition, Jonathas de Andrade confronts his country’s complicated past and present.

By Amelia Rina

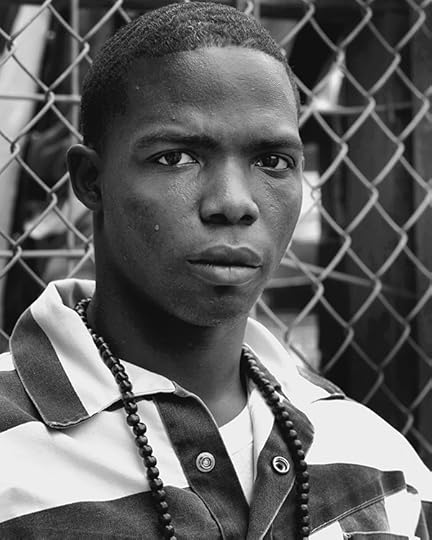

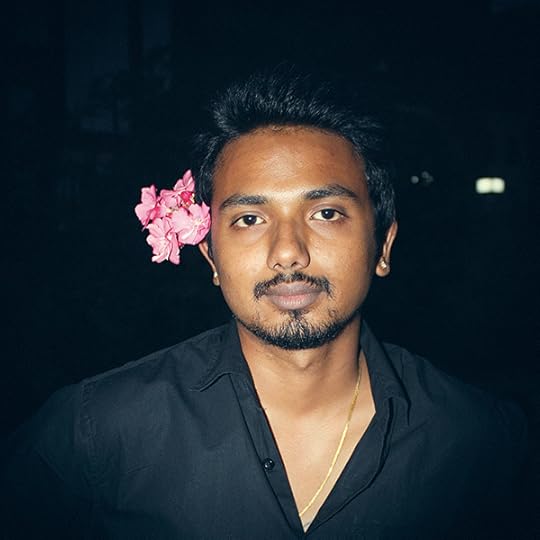

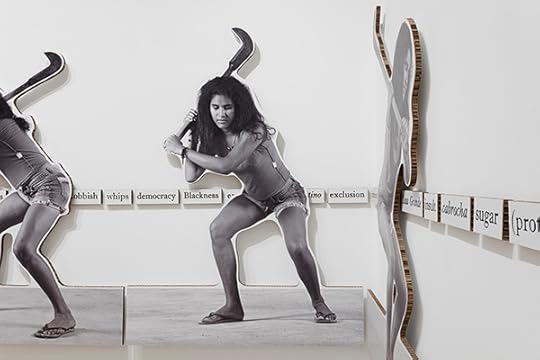

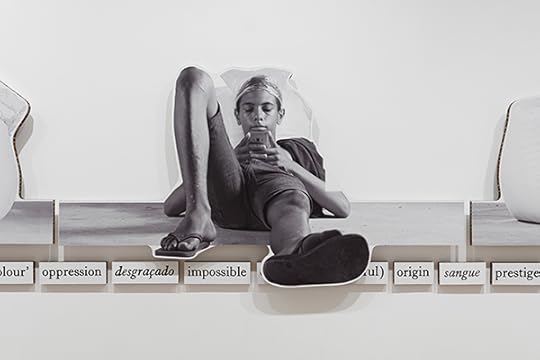

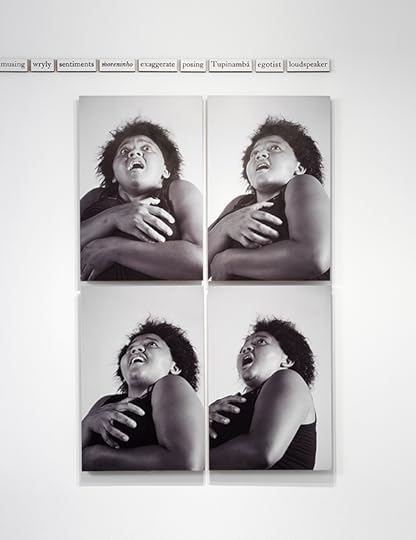

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

“Brazil is renowned in the world for its racial democracy,” begins anthropologist Charles Wagley in the 1952 study Race and Class in Rural Brazil. Produced by Columbia University and UNESCO, the text describes ethnographic studies performed by Wagley and his colleagues in four regions of Brazil. In each region, men and women from what they determined to be the four major racial groups—caboclo (indigenous and Afro-Brazilian), preto (Afro-Brazilian), mulato (Afro-Brazilian and white European), and branco (white European)—were shown photographs of other Brazilians from these categories and then asked to assign them different traits, such as most/least attractive, best/worst worker, most/least honest, most/least wealthy, et cetera. This binary restriction was one of the study’s major flaws that first intrigued Brazilian artist Jonathas de Andrade, and inspired his recent project, Eu, mestiço, currently on view at Alexander and Bonin.

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

The introduction quickly reveals the study’s extreme outdatedness and the internalized racism and discrimination of the supposedly neutral scientists. Wagley goes on to support his hypothesis of racial tolerance by citing that “the Portuguese colonizer of Brazil was as compared with many Europeans, singularly lacking in race prejudice, and in fact the Portuguese male colonist seemed to have felt a rather strong attraction to the darker Amerind and Negro women.” By categorizing their subjects in such a way, the scientists confirmed their biases. Instead of being able to spontaneously describe the individuals in the photographs, they confined the subjects to this polarizing language.

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

“The study used a methodology, based on photographs, to tease participants into being racists, and invited them to judge the characters in the photographs,” de Andrade told me recently. The final publication also omits the original images used, effectively leaving the reader with an elaborate list of racist expressions and stereotypes, but no context. For his photographic series Eu, mestiço (Me, mestizo) (2018), de Andrade also provides an incomplete narrative—with one major difference. Unlike the scientists before him, de Andrade flips the observer/observed, active/passive relationship by giving agency back to those who would otherwise be powerless subjects. De Andrade traveled to several cities in Brazil and presented people with the UNESCO study, then invited them to physically perform their interpretation of the social types described in the text. The resulting photographs provide both a critique of the colonialist quantifying and categorizing of human bodies, and a self-aware critique of race and class stereotypes that have perpetuated through the decades.

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Within moments of walking into the spacious Alexander and Bonin gallery, the observer takes in an exhibition that begins as an exercise in free association, but quickly becomes uncomfortable. Large black-and-white halftone images of people printed on falconboard, a material typical of mass-produced signboards in Brazil, float throughout the gallery in grids and linear sequences. Some of the images are rectangular, while others are presented as cutouts tracing the subjects’ contours. A steady line of individually mounted words taken from Race and Class in Rural Brazil sits like a horizon around and behind the images. De Andrade forces viewers to confront their associations with words like “whips,” “escuro” (“dark”), “sugar,” “sophistication,” “carcass,” “criminal,” “rich,” “nordestino” (“northeastern”), and “mixed,” and the images of people of various races performing various actions.

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Yet, as though to indicate that no experience can ever be condensed to simply one word and one image, each person appears from at least three different angles or expressions. In one sequence, a young woman grabs her chest and leans back in shock or fear. In another, a woman with short white hair faces away from the camera, revealing the elegant lace decorating the back of her blouse. In yet another, a lanky young man gazes into and away from the camera, as it captures his casually angular repose from different viewpoints. The images, some glamorous and some absurd, also prompt speculation about which stereotype each person was performing, which further elicits the viewer’s internalized bias. Is the man carrying the apparently heavy sack a hard worker or lazy? Are the two young girls staring confidently into the camera poised or haughty? The text in combination with the almost stop-motion aesthetic of the multiple images creates a continuous yet nonsensical narrative of discrimination and hijacked identities.

Jonathas de Andrade, Eu, mestiço, 2017–18

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Instead of a didactic text that might do little to challenge the author or reader, de Andrade has facilitated a heuristic experience that reveals viewers’ opinions to themselves. The text and images force viewers to confront their immediate associations and internalized judgements. By referencing, not replicating, the original photographs, the pairing also breaks down the assumed veracity of documentary photographs in scientific studies, and challenges the historical credibility of the photographic object. In Eu, mestiço, de Andrade presents a direct satire of the UNESCO study, especially its declaration of Brazil’s supposed racial democracy, which de Andrade says is a “dangerous myth”: “The concept of racial democracy . . . has been used to diminish the presence of racism as it is absorbed in many layers of daily life.” In today’s current tumultuous political climate, Eu, mestiço will resonate with those coming together to fight against authoritarianism and other forms of oppression by encouraging the indispensable act of critical introspection.

Amelia Rina is a writer based in New York.

Jonathas de Andrade: Eu, mestiço is on view at Alexander and Bonin, New York, through April 21, 2018.

The post The Myth of Brazil’s Racial Democracy appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 11, 2018

Inside Aperture’s 2018 Spring Party

Dr. Ruth Oratz, host Martha Stewart, and Dr. Albert Knapp

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Regina DeLuise, sponsor Stuart Cooper, and Susan Belsinger

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Angela Dimayuga and Spike Jonze

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Zsela

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Gabrielle and Andrea D'Avack

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Martha Stewart and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Ian Wardropper and host Sarah Anne McNear

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

The Aperture Spring Party at PUBLIC ARTS

Michelle Kim © Aperture

Zsela and Angela Dimayuga

Michelle Kim © Aperture

Dr. Ruth Oratz and Jessica Nagle

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Samuel Lawson, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, and Brett Allen

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Alix Brown

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Andre Akpan and Adrienne Collatos

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Dianna Cohen and Alexander Hurst

Madison Reid © Aperture

Floral arrangement by Saipua

Michelle Kim © Aperture

Jessica Nagle, Hemant Kanakia, and Dr. Sonalde Desai

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Elizabeth Ann Kahane and Lindsay McCrum

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Emma Bowen and Tina Barney

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Florian Koenigsberger and Victoria Schorsch

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Aperture executive director Chris Boot and Dawoud Bey

Madison Reid © Aperture

Hemant Kanakia, Dr. Sonalde Desai, Dr. Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas, Sr., and Elaine Goldman

Madison Reid © Aperture

George Rabot, Zoe Suna, and Liz Grover

Madison Reid © Aperture

Lisa Rosenblum and Nina Celebic

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Louise Lui and Colton Klein

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Tim Doody and Lisa Corinne Davis

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Host Stephen Shore and Anne Stark Locher

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Neil Lester and Filip Vurdelja

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Zsela

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Alex Berggruen and host Martha Stewart

Madison Reid © Aperture

Host Sarah Anne McNear and Darius Himes

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Nina Rosenblum and Dan Allentuck

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Yasufumi Nakamori, Lesley A. Martin, and Elena Dorfman

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Michelle Kim © Aperture

Anne Stark Locher, Whit Williams, and Kate Cordsen

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Alex Berggruen

Madison Reid © Aperture

Aperture executive director Chris Boot, Susan Gutfreund, host Sarah Anne McNear, and Tony WhiteMichelle Kim © Aperture

Allan Chapin, Anna Rachminov, Lisa Corinne Davis, and Jonathan Gould

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Michelle Kim © Aperture

Tina Barney and Emma Bowen

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Amy Hood, Callie Roth, and Bode

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Marx Goldberg and Ethan James Green

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Missy O'Shaughnessy, Allan Chapin, Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan, and Emily Grillo

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Aperture Spring Party guests Madison Reid © Aperture

Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan and Darlene Kaplan

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Darius Himes, host Stephen Shore, Aperture executive director Chris Boot, and Tom Schiff

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Elizabeth Ann Kahane and Mariane Ibrahim

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Kellie McLaughlin, Hank Thomas, Sr., and Dr. Deborah Willis

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Leonard Lauder and Judy Glickman Lauder

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Host Martha Stewart with cupcakes by Brooklyn Floral Delight

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Michael Hoeh and Aperture executive director Chris Boot

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Roland Hartley-Urquhart, Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan, and Renwick Martin

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Susan Gutfreund, Lucky, and Judy Glickman Lauder

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Zsela

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Sharon Core

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Dr. Sonalde Desai and Kurt LocherPatrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Matt Lucero and Priyanka Pulijal

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Susan Belsinger and sponsor Rebecca Besson

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Liz Grover, April Havranek, Michelle Gladd, and Lori Grover

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Hosts Martha Stewart and Sarah Anne McNear, Leonard Lauder, Judy Glickman Lauder, and Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullanPatrick McMullan/PMC

David and Sally Park with Nathaniel Stein

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Christina Swilley

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Zsela

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Esther Zuckerman and Denise Wolff

Patrick McMullan/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Sean Zanni/PMC © Patrick McMullan

The 2018 Aperture Spring Party, held on April 6, was a much-anticipated happening for photography enthusiasts in New York during The Photography Show presented by AIPAD. Guests were decked out in vibrant floral patterns inspired by blooms—on dresses, skirts, blazers, and jumpsuits. Celebrating the pre-launch of Aperture’s forthcoming book The Photographer in the Garden, the nearly three hundred guests who attended enjoyed an evening of food, music, and dancing with Garden’s coauthors Sarah Anne McNear and Jamie M. Allen. The event was sponsored by Sb Cooper and R. L. Besson, Besson/Cooper Fund, and cohosted by McNear, along with Martha Stewart and Ginger and Stephen Shore. Event and auction proceeds support Aperture serving the art, story, and community of photography through publications and educational programs with the world’s leading photographers, artists, scholars, and authors.

A familial pre-party dinner with approximately one hundred of Aperture’s closest friends took place on the seventeenth floor of the Public Hotel with panoramic views of Manhattan. Guests were seated with Garden contributors, including McNear, Shore, Allen, and photographers Tina Barney and Sharon Core. Barney and Core, along with Daniel Gordon, contributed prints to a live auction conducted by Alex Berggruen of Christie’s. Dinner guests received gratis copies of Martha’s Flowers and The Photographer in the Garden, gifted by Martha Stewart and Aperture trustee Michael Hoeh.

The Spring Party, held at Public Arts, was hosted by Aperture’s Connect Member group of young leaders and other individuals. Guests sipped on cucumber and mint cocktails courtesy of VDKA 6100 and posed around the photo set powered by HYPNO, with a vibrant floral installation by Saipua and a neon Aperture sign. Among the mix of guests who attended were Darius Himes, Dr. Deborah Willis, Spike Jonze, Angela Dimayuga, Andrea and Gabrielle d’Avack, Leonard Lauder and Judy Glickman Lauder, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Ethan James Green, Alex and Rebecca Webb, John Chiara, Mitch Epstein, and Penelope Umbrico. The highlight of the night was an enchanting performance by Brooklyn native singer-songwriter Zsela, accompanied by Daniel Aged on piano. (Zsela is currently working on a debut release for later this year.) Alix Brown wrapped up the night with sets that inspired a lively dance party until after midnight.

Courtesy of Patrick McMullan Company, click here to view photos from the event. Additionally, view the HYPNO booth photos by clicking here.

Aperture wishes to thank cohosts Martha Stewart, Ginger and Stephen Shore, and Sarah Anne McNear; sponsors Sb Cooper and R. L. Besson, Besson/Cooper Fund; George Eastman Museum’s Jamie M. Allen; all of the contributing Garden photographers; Christie’s; photograph magazine; Saipua; VDKA 6100; Zsela; Daniel Aged; and Alix Brown.

Additional thanks goes to the Leaders, the Host and the Spring Party Committees, and to all of the Aperture staff, work scholars, volunteers, and ambassadors for their time and dedication.

Sponsors

Sb Cooper and R. L. Besson, Besson/Cooper Fund

Leaders

Allan Chapin and Anna Rachminov

Anonymous

Bill and Victoria Cherry

Cathy M. Kaplan

Elaine Goldman and John Benis

Nion McEvoy

Thomas R. Schiff

Host Committee

Anne and Kurt Locher

Anonymous

Betsy Evans Hunt and Christopher Hunt

Darius Himes, Christie’s

Darlene Kaplan and Steve Zuckerman

Dr. Albert Knapp and Dr. Ruth Oratz

Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Hemant Kanakia and Sonalde Desai

Howard Greenberg

Jessica Nagle and Roland Hartley-Urquhart

Kate Cordsen

L.C. Wisnewski

Leonard and Judy Lauder

Malú Alvarez

Mark and Elizabeth Levine

Martha Stewart

Michael Hoeh

Missy and Jim O’Shaughnessy

Mrs. John (Susan) Gutfreund

M&T Charitable Foundation

Peter Barbur and Tim Doody

Rita Anthoine

Sarah McNear and Ian Wardropper

Victoria Schorsch

Whit Williams

Willard Taylor and Virginia Davies

Spring Party Committee

Alexander Hurst

Angela Dimayuga

Dianna Cohen

Liz Grover

Liz Higgins

Michael Sbabo

Paula Naughton

Sam Pritzker

Sarah F. Haimes

Tanya and David Wells

Tim Matusch

Todd Wiener

The post Inside Aperture’s 2018 Spring Party appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In Marrakech, African Photography on Its Own Terms

A new museum in Morocco becomes a destination for contemporary art.

By Sean O’Toole

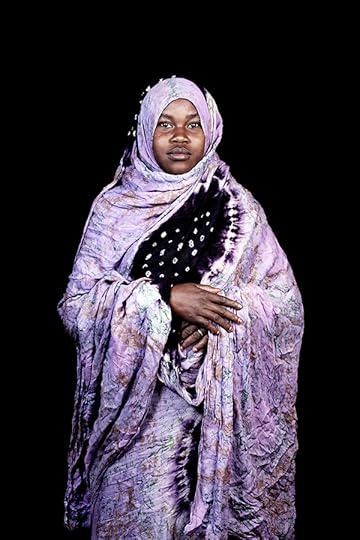

Leila Alaoui, Khamlia, Sud du Maroc #1, 2014, from the series The Moroccans

© Fondation Leila Alaoui

The life and work of Leila Alaoui, the celebrated Moroccan documentary photographer, looms large over Marrakech’s newest art institution. Alaoui, who at age thirty-three was shot and killed during an al-Qaeda attack in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, was a close friend of Othman Lazraq, the photography-enthused president of the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), a privately owned art foundation on the southeastern outskirts of this walled city at the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. MACAAL’s inaugural photography exhibition, Africa Is No Island, bears the subtle imprint of Alaoui’s influence.

Speaking during a weekend of festivities in late February that included a boutique edition of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair to mark the international launch of MACAAL, Lazraq cited his friendship with Paris-born Alaoui, an accomplished editorial photographer and portraitist who grew up in Marrakech, for sparking his interest in photography. The two met in New York, where Alaoui studied photography, and quickly struck up a friendship. Lazraq’s first photography purchase was a work by Alaoui, who also guided him on his early acquisitions—Lazraq’s home in Casablanca includes works by Araki, Peter Beard, Malick Sidibé, and the emerging South African Phumzile Khanyile.

Africa Is No Island. Installation at Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden. Photograph by Saad Alami

© MACAAL

“I was very young, only twenty, when I started buying photography with Leila,” said Lazraq, twenty-nine, who, like his father—Alami Lazraq, a Moroccan property tycoon and one of Africa’s wealthiest businessmen—is an architect by training. Speaking with characteristic brio, MACAAL’s youthful leader told an audience at the museum’s opening how Alaoui introduced him to her motivating ideas as a portraitist, of “facing” the real and “fixing a moment of history.” Alaoui’s sway, however, extends even further: she introduced Lazraq to Jeanne Mercier and Baptiste de Ville d’Avray, of the photography platform Afrique in Visu, who MACAAL later invited to curate Africa Is No Island.

The exhibition features a total of twenty-two individual photographers and one collective, many from the African continent, others—like Paris-based Italian photographer Nicola Lo Calzo and New Jersey-born Ayana V. Jackson—deeply occupied by its social life and connectedness to the wider world. Fittingly, the exhibition includes an image by Alaoui: a life-size portrait of a young Gnawa woman in violet-colored Mauritanian dress, photographed in 2014 in southern Morocco. Installed in an alcove with two speakers playing ambient sounds recorded in Marrakech by Italian artist Anna Raimondo, the work is excerpted from Alaoui’s The Moroccans (2010–14), a roaming project descriptive of the country’s disappearing cultural traditions and diverse racial makeup.

Nicola Lo Calzo, Portrait de David Godonou-Dossou, riche marchand et fondateur de la dinastie Godonou-Dossou, 2011

© the artist

“We chose someone who doesn’t look like a Moroccan,” said Mercier during a walkthrough of the exhibition in reference to Alaoui’s striking portrait. Although Moroccan, the swaddled Gnawa woman’s ancestry is linked to enslaved West Africans brought to the region by Arab and Berber traffickers. Africa Is No Island is mindful of the historical forces that have wracked the African continent. The exhibition includes five portraits from Lo Calzo’s ambitious multicountry project Cham (2007–16), about the embodied legacy of the African slave trade. In 2015, New Yorker critic Hilton Als praised Lo Calzo for bringing “disappeared bodies” back to life “by their living and breathing descendants.” Aalaoui’s portrait achieves much the same.

The team of Afrique in Visu invited French curator Madeleine de Colnet to assist them in their selections, with Lazraq offering additional input—notably a prohibition on wall captions and texts for the individual works on show. “I am really driven by emotions,” said Lazraq about his philosophy as a collector and curator. The lack of explanatory texts at MACAAL is nonetheless a hindrance, especially given the preponderance of documentary and conceptually applied photography on offer. For instance, French Moroccan photographer Mustapha Azeroual’s interest in uniqueness and preindustrial modes of photography—explored in Arbre #2 (2011), a ceiling-hung installation of two hundred porcelain plates featuring one-off images of trees made with a gum bichromate printing process—is hardly self-evident.

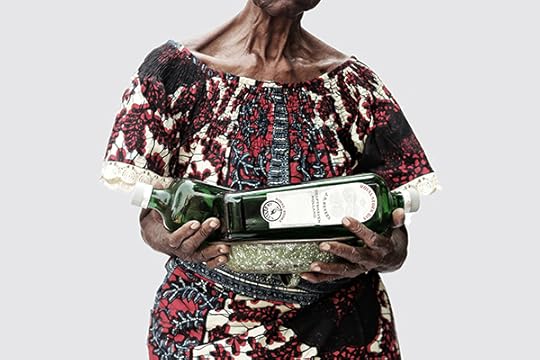

Ishola Akpo, L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux, 2014

© the artist

Roughly half the work gathered in Africa Is No Island is drawn from MACAAL’s private collection, the balance sourced through Afrique in Visu’s vast network, which is visually signaled at the ground-floor entrance to the exhibition in a wall-scale collage of photographs featured on the platform’s website and exhibitions. Africa Is No Island properly begins with three color images by Beninese photographer Ishola Akpo, from his series L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux (Essence is invisible to the eye, 2014), matter-of-fact descriptions of dowry objects—like an enamel plate and bottle of gin—that belonged to his recently deceased grandmother. The gently melancholic note registered by this work recurs throughout Africa Is No Island, even in the photographs of Walid Layadi-Marfouk and Lebohang Kganye, the show’s youngest exhibitors.

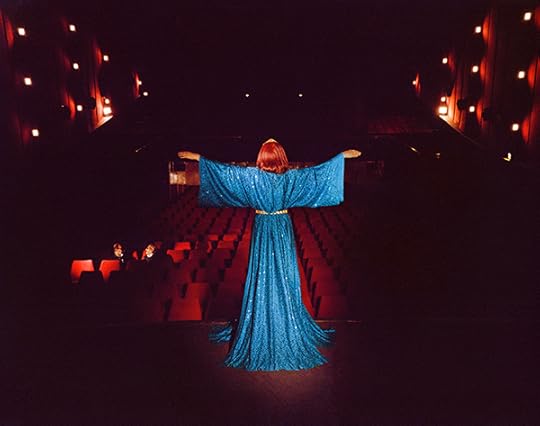

Along with Alaoui and Hicham Gardaf—a Tangier-born photographer whose series The Red Square (2014–17) offers an economical insight into Morocco’s rapid urban development in a style redolent of Lewis Baltz and Angolan photographer Edson Chagas—Layadi-Marfouk represents the vanguard of young Moroccan photography. His Riad series (2017–ongoing) is largely set in his family home in Marrakech and portrays his kin, notably an aunt, involved in choreographed actions. An outlier in the series, Haya Jat (Starfixion), presents this aunt in a blue evening gown, arms outstretched, facing an audience of two from the stage of Marrakech’s Le Colisée, an Art Deco cinema acquired by the Layadi family in 1971.

Walid Layadi-Marfouk, Haya Jat (Starifixion), 2017

© the artist

“The idea of the series came when I moved to the US,” said Layadi-Marfouk, who studied math at Princeton before changing to photography. “The visual representation [in the US] of my culture was completely separate and other from the way I had internalized, sublimed, and fantasized it growing up in Morocco. They were just black-and-white images of violent submission, pain, and extremism.”

Similar to Layadi-Marfouk, South African–born Kganye also uses portraiture to affirm her identity and explore intergenerational relations in her breakout 2013 series, Ke Lefa Laka (My heritage). Kganye’s photographic tableaux, which effortlessly blur the line between playful fantasy and sober document, present her in comical poses wearing her grandmother’s clothes and interacting with figures and settings photocopied from various family albums gathered during a research trip in 2012. “Photographs are more than just a memory of moments passed, or people no more, or a reassurance of an existence,” noted Kganye when she first exhibited her work at the Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg, in 2013, adding that they were also evidence of “a constructed life.”

Lebohang Kganye, Pied Piper, 2013, from the series, Ke Lefa Laka

© the artist and courtesy Afronova Gallery, Johannesburg

Kganye is adroitly paired in the exhibition with Sammy Baloji. The Congolese photographer is represented by three photographs, one depicting a Chinese pagoda built by dictator Mobutu Sese Seko at his ruined palace complex in Gbadolite overlaid with a black-and-white image of a bare-breasted Congolese woman photographed in 1935 by Belgian tropical medicine expert Dr. J. A. Fourche. Both photographers use collage techniques to overlay visual memories of the past, some personal, others collectively experienced, on the present day—the burden of history is palpable.

Namsa Leuba, Statuette Kafigeledio Prince, Guinea, 2011, from the series, Ya Kala Ben

© the artist and courtesy Art Twenty One Gallery, Lagos

The exhibition is noteworthy for its strong showing of performance-inflected portraiture, with exemplary works by Joana Choumali, Maïmouna Guerresi, Ayana V. Jackson, and Namsa Leuba, whose cryptic frontal portrait of an anonymous figure wrapped in synthetic material posed in an industrial site, Statuette Kafigeledio Prince, Guinea (2011), forms the cover image of the exhibition catalogue. Choumali’s portraits from her series Hââbré: The Last Generation (2013–14) were a clear favorite with visitors. The images explore the waning practice of facial scarification in West Africa, and feature sitters photographed in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, from both frontal and posterior views.

Like Jackson, whose self-portraits explore the photographic representation of blackness, Choumali’s stylized work is informed by anthropological codes of picturing otherness. The Photography Museum of Marrakech, which opened in 2009, offers ample evidence of this earlier photography; its holdings include pictorial, ethnographic, and colonial photography dating from the colonial occupation of Morocco that ended in 1956. The museum’s displays include a selection of prints by Hungarian photographer Nicolás Muller, who died in 2000 and was the subject of a survey at Jeu de Paume, Paris, in 2014. His confidently modernist portrait of a Tangier youth, photographed in 1941 in three-quarter pose, chimes with the work of Choumali, and even Alaoui—at least stylistically.

Joana Choumali, Mme Djeneba, 2013–14, from the series Haabré: The Last Generation

© the artist and courtesy 50 Golborne Gallery, London

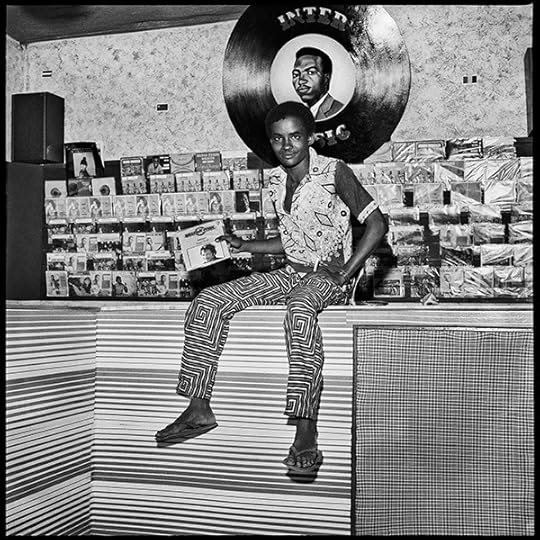

But style is an unreliable point of entry into contemporary African portraiture; rather it is an interest in photography’s hazy ethics and a common cause between subject and maker that compels many contemporary portraitists. That portraiture is now the genre du jour across the continent was clear from the selection at MACAAL, and also the offerings at the inaugural Marrakech version of 1-54, held in the sumptuous La Mamounia Hotel. Of the artists on show at MACAAL, Leuba, Choumali, François-Xavier Gbré, and Hicham Benohoud all had work on sale at 1-54. One of the highlights of the fair was New York dealer Yossi Milo’s presentation of five gelatin-silver prints by Sanlé Sory from his Volta Photo portrait studio, opened in 1965 in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second-largest city. The selection included a striking side-view portrait of a youth in a white vest and cap, thumb propping his chin, eyes appraising the camera—he oozes swagger. Last year, Sanlé told The Guardian, “Fun was central to my work.”

Sanlé Sory, Chez Inter Music, 1976

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

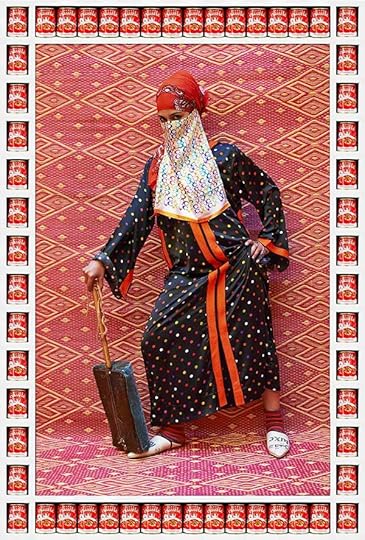

Fun also remains essential to the work of Hassan Hajjaj, a Moroccan pop artist who took up photography in 1989. Best known for his vivid and playfully garish street portraits of Moroccan youth, Hajjaj’s photography is a flip, urban counterpoint to Alaoui’s respectful portraits, and is on permanent view at Riad Yima, a boutique and tearoom in the medina that also includes a gallery. As part of the festivities around MACAAL’s opening, Hajjaj invited Yoriyas Yassine Alaoui to exhibit his street photographs of ball players, sunbathers, and worshippers from the series Casablanca Not the Movie (2015–ongoing).

Hajjaj’s initiative lent a biennial-like feel to the weekend of MACAAL’s opening, as did writer and translator Omar Berrada’s thoughtfully curated program of talks on the subject of decolonization at the fair, including a fascinating performance-lecture by the Black Athena Collective (photographers Dawit L. Petros and Heba Y. Amin) on pharaonic-era trade along the Red Sea.

Hassan Hajjaj, Marmouche, 2012

Courtesy the artist

In recent years, Marrakech has emerged as an important art destination in North Africa. This legacy is partly founded on the successes of the Marrakech Biennale, an unapologetically progressive showcase of Mediterranean—rather than exclusively African—art, founded in 2005. The 2009 edition, for instance, included a picnic hosted by Tangier-based photographer and artist Yto Barrada, and British artist Shezad Dawood’s Make It Big (Blow Up), hoax stills from a Pakistani remake of Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow–Up (1966). However, the withdrawal of sponsorship last year led to the cancellation of the 2018 biennial, which would have coincided with MACAAL’s opening.

Private collectors like the Lazraq family and Nabil El Mallouki, whose Museum of Art and Culture of Marrakech opened in early 2016, offer an alternative approach to sponsor-led events like the biennial. These new private museums also slot into a growing network of cultural venues in Marrakech: some are modest, like the photography museum and Hajjaj’s Riad Yima; others—like the Yves Saint Laurent Museum, opened last year opposite a garden that was created by artist Jacques Majorelle and later acquired by the late French fashion designer—cater to Marrakech’s new class of culture tourists.

“The role of a museum is to engage and educate people, to somehow bring a small touch of light and hope,” said Lazraq before proudly ushering journalists into Africa Is No Island. “I think Morocco needs it, Africa needs it, we all need it.” Part of that education, he added, involves reframing perceptions of photography. Lazraq jovially recalled his father’s befuddlement at his preference for photography, video, and installation art, saying he enjoyed the pushback. It helped reinforce a central article of faith: “Photography is a medium I love and care for.” The eccentricities characterizing MACAAL’s debut photography exhibition design and approach to information notwithstanding, Africa Is No Island is a confident expression of Lazraq’s passion for the medium and ebullient vision to make his North African museum a destination for photography enthusiasts.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and editor based in Cape Town.

Africa Is No Island is on view at MACAAL, Marrakech, through August 24, 2018.

The post In Marrakech, African Photography on Its Own Terms appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 10, 2018

2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Fabiola Cedillo, Untitled, 2016; from the series Los mundos de TITA

Philip Cheung, Weapon maintenance, Kandahar Airfield, 2010; from the series The Thing About Remembering

Dylan Hausthor & P. Guilmoth, Untitled, 2018; from the series Sleep Creek

Eduardo L Rivera, A Seat at the Table, 2016; from the series Over Dry Lands

Ka-Man Tse, Untitled, 2017; from the series Narrow Distances

We’re pleased to announce the five finalists for the 2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an international photography competition whose goal is to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition:

Fabiola Cedillo

Philip Cheung

Dylan Hausthor & P. Guilmoth

Eduardo L Rivera

Ka-Man Tse

This year, Aperture’s staff reviewed more than 900 portfolios. Our challenge is to select one winner and four honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. One finalist will be selected as the winner and will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition in New York.

We are delighted to welcome these five finalists to our ranks of illustrious past winners and finalists, joining such artists as Natalie Krick, Eli Durst, Drew Nikonowicz, Amy Elkins, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Alexander Gronsky, Sarah Palmer, Louie Palu, Bryan Schutmaat, and many others. The winner of the 2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced later this month, and the finalists’ portfolios and statements will be featured on aperture.org.

The post 2018 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 4, 2018

A Startling Discovery at San Quentin

Ear Hustle podcast creator Nigel Poor uncovers a trove of photographs at California’s most infamous prison.

By Rebecca Bengal

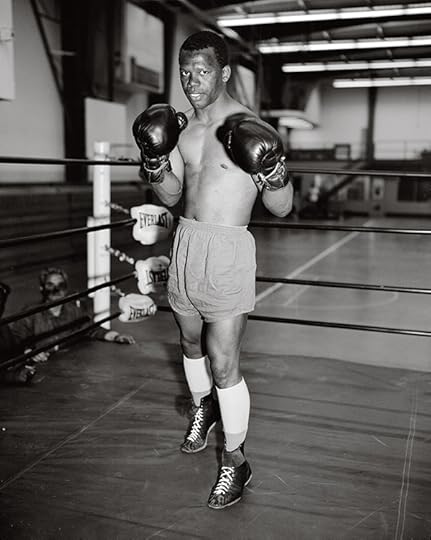

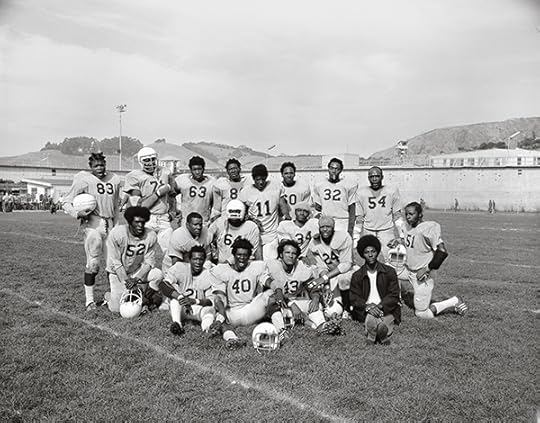

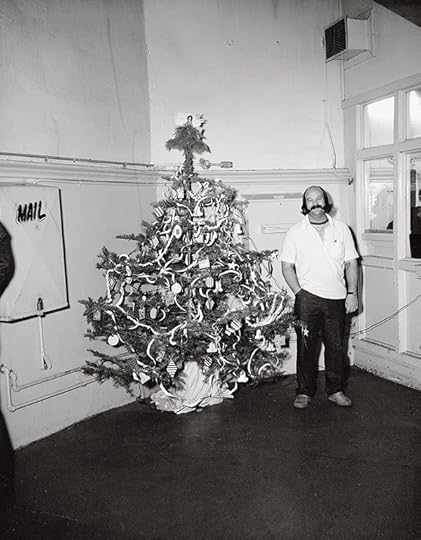

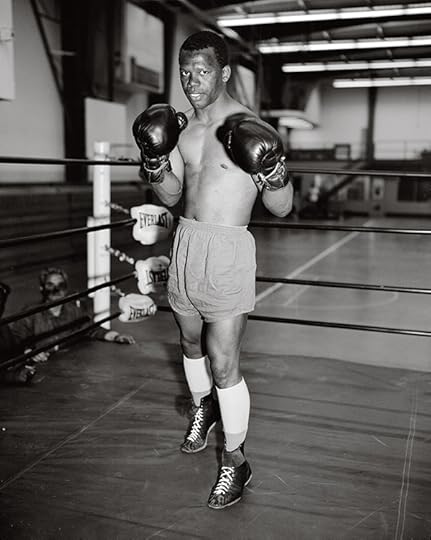

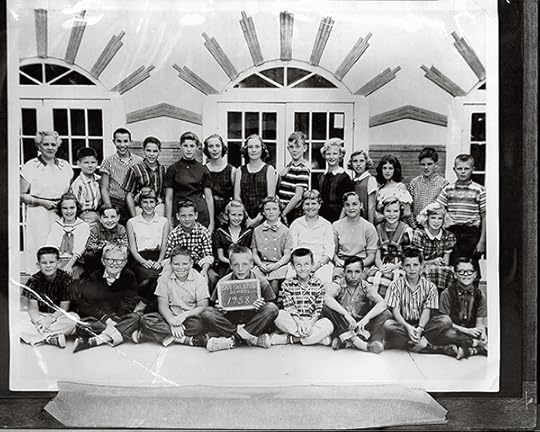

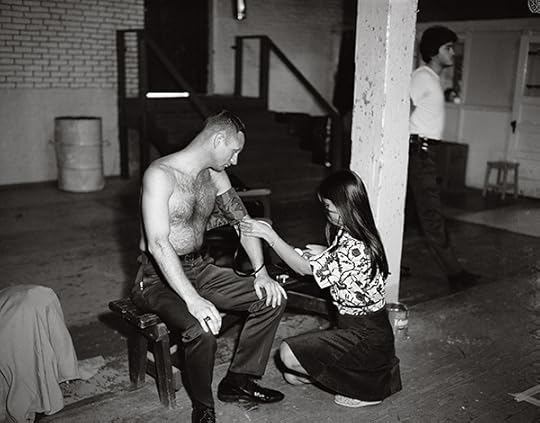

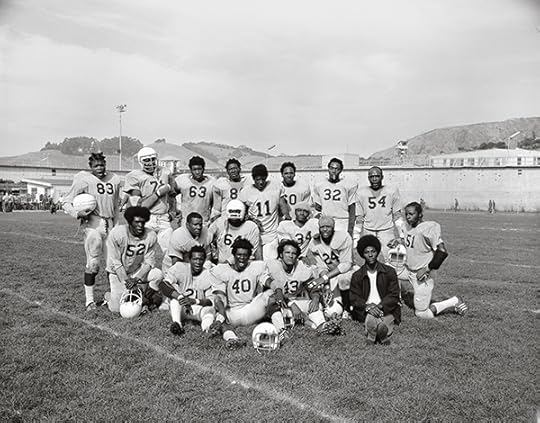

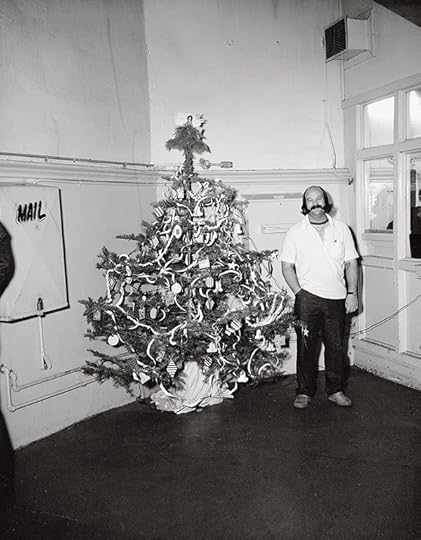

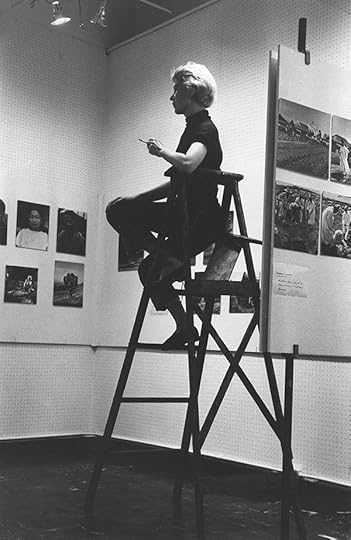

Photographer unknown, WH Woodside, CO Fight, April 8, 1961

Courtesy Nigel Poor, San Quentin Archive, and Haines Gallery, San Francisco