Aperture's Blog, page 101

May 17, 2018

Queer Looking, Queer Being

How can photography transform representations of non-binary and transgender bodies?

By Rowan Renee and Arno Mokros

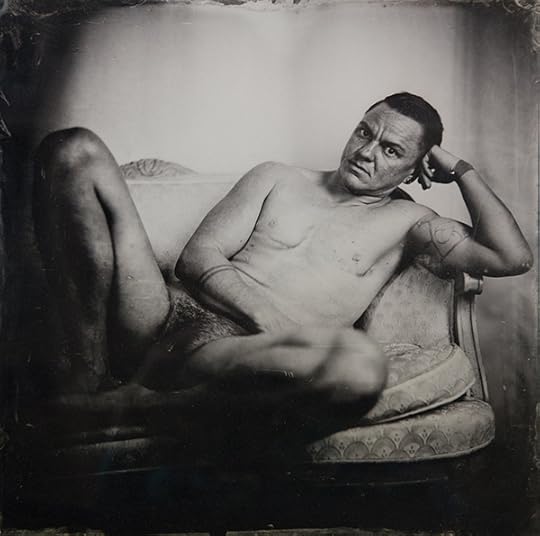

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

This conversation is excerpted from a much longer dialogue between artist Rowan Renee and critical viewer Arno Mokros. Our conversation has spanned over two years, fifty written pages, and many hours of recorded audio. We first met in 2015, during an open studio at Pioneer Works, where Rowan presented work as an artist in residence. The photographs on view were from Z, a series of nude ambrotypes dealing with gender ambiguity across a spectrum of trans, cis and gender-nonconforming identities. Arno’s first encounter with Renee’s photographic work at Pioneer Works sparked an initial conversation, which then expanded into an ongoing dialogue.

Rowan Renee: Do you have an image that stands out in your mind? When I met you during the open studio, I remember watching you look at the images and thinking that I could tell that they were making an impact on you. I wonder if there was an image you saw on that visit that particularly struck you?

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Arno Mokros: I think the image pictured above was in your studio the first time I was there. If you’re someone who’s familiar with the trans community, there’s a series of symbols or signifiers attached to trans male bodies that are very recognizable. One of them is chest scars, top surgery scars. They are so visible in this image. I have an immediate recognition of that signifier because of my own trans identity and internalization of what trans men look like. Actually, I consider that to be part of the process of initiation to being trans: learning what it means to live a trans experience on a bodily level. That aspect of initiation has involved me studying what the body is “supposed” to look like as a trans man.

Renee: What do you mean when you say what a trans man is supposed to look like? Are you talking about assimilating to conventional representations of masculinity?

Mokros: What trans men look like as a type. What an attractive trans man looks like. What is acceptable for that body. I read this model’s body as masculine for particular reasons, in response to certain signifiers, which all operate to facilitate “passing” as one gender or another. I think there’s a distinction between recognizing a body as masculine-of-center, as opposed to discerning “maleness” and “femaleness” in terms of sex. This image puts on display the intersection of masculinity and female-embodiedness. Something I always say is that “I’m a queer-bodied person.” And that’s because queerness is always visible on my body if it is exposed. So I see a specifically queer body in this image, a representation of an expression of trans masculinity, in both an embodied and performative sense. As a viewer, I don’t actually know this person’s identity, but the judgments and determinations through my own perception are inseparable from my queer subjectivity. I acknowledge that I project a lot of myself onto that image, onto what I’m arguing that this image puts forth. In part, my insecurities about maleness/masculinity, femaleness/femininity, bodies, sex, and gender are on display through my own reading of this image.

Renee: The queer embodiment in this image is legible to you as a trans man.

Mokros: Yes, but I know the signifiers. Like being able to recognize chest scars as part of the trans body—that’s legible to me.

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Renee: In the experience of talking to different people who have seen this image, there are a lot of people who don’t know the signifiers, and read it in a very confused way. In the “trapped in the wrong body” narrative that is so widespread in the mainstream understanding of trans identities, I think there’s an underlying feeling that there is a contradiction present if the genitals don’t match what is assumed to be biologically essential to gender. Like that all men have penises.

Mokros: Really? I can’t even fathom that level of unfamiliarity anymore, but that just shows how invisible trans bodies are, really. The first time I saw this in your studio I didn’t have a context for your work and I didn’t have any assumptions about the content of your work, or who your work would represent. So I walked in and I was honestly quite pleasantly surprised to see bodies like mine. In my own life, I seek out images of trans bodies for a variety of reasons, but they’re usually not presented to me spontaneously. Seeing your work was a moment of realizing someone else was on the same wavelength. I don’t mean that I felt a connection to this person because he is also trans, but rather that I could recognize that you considered some of the same questions that I did in the process of documenting, in considering other trans bodies. It introduced me to an immediate sense of trust with you. Probably if I hadn’t seen this image I wouldn’t have talked to you at all. As much as I would have liked your work anyway, it would have been really different. I might not have been as curious.

Renee: Am I projecting if I say that you connect to this image because you are able to empathize with the sitter, and that you recognize in him a vulnerable visibility of the body that you relate to?

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Mokros: I think it evokes the potential, the possibility (and maybe even the risk) that my own body will be made visible. I think about how other people read me every day. It is part of my routine to be sure I pass as male whenever possible. I avoid situations in which I am forced to explain my gender history. I don’t often—or really ever—present my body to other people on its own terms. I don’t know what it feels like to have everything on display. I think some people are confused by the bodies in these photographs or trans bodies in general because they are simply ignorant of the diversity of bodies in this world. I spend time wondering: twenty years from now, will the general population recognize that trans bodies are not anomalous, but rather just some of many possible forms? Will we be at a place when people no longer assume bodies are either male or female? Personally, I don’t know what it would feel like to occupy space in my body on its own terms, to not try to be seen as a cisgender male to the outside world. But this image is visible to the outside world now, and it isn’t about being seen as a cisgender male.

Renee: It’s about showing that you’ re not.

Mokros: So often, and I would say too often, images of trans people have been about—especially in erotic or porn settings—gender expression as a trick. As if a person’s genitalia reveals that you’ve been fooled and “this is really a man” or “really a woman.” I was attracted to your work because I felt that you were doing something more than “documenting” trans and gender-nonconforming bodies as curiosities to be fetishized or as human interest pieces. The models in this body of work are vulnerable as nude subjects before the camera, and yet I feel they are safe within your frame, and that you resist and protect your models from being fetishized and misunderstood because of how you capture them. When I came in contact with your work, I felt that you were contributing to the representation of queer and trans bodies, but also thinking beyond representation—perhaps even navigating your own relationship to gender. It’s often assumed that trans people are subjects, while photographers occupy an objective, masculinist, cisgender perspective. As an artist, I think you make clear that you are a part of the community you photograph, and that you are immersed in the same questions about queer identification, representation, and self-determination.

Renee: Yes, I think you’re touching on the myth of objectivity in documentary work. I wasn’t following a proper documentary photographic practice. I didn’t see myself as an outside observer while making Z, but I also didn’t yet see how I fit into the conversation. I was searching for a language and a community that gave form to feelings that otherwise seemed illegitimate in a heteronormative (and homonormative) society. I was learning how to be queer. I worry that it sounds narcissistic to shift the focus of a portraiture project to my own inner landscape, but I also think the motivations of the photographer are relevant and inevitably affect the work. I’ve been thinking a lot about how queer knowledge is transmitted through dynamics of interpersonal relationships between queer people. How a queer education often plays out in relationships rather than within institutions.

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Mokros: I actually think your work creates a queer space, and it sounds like you’re saying that the photographic process itself was a creation of queer space in which queer knowledge passed between you and the models you worked with.

Renee: Yes! That’s it. Part of the process of making Z was to fight against power dynamics of model-photographer relationships. But, I don’t want to sound overly naive about power or my role as a photographer. There’s a reason why queer spaces often radically challenge systemic power structures, and part of that is an underlying recognition of how power does not necessarily have to be wielded as an absolute. I thought of my role as a photographer as a constant negotiation of the terms and boundaries of the artist-model relationship, which implies that consent isn’t fixed or absolute. It’s in flux and always on the table for renegotiation. There were aspects of my process that were about surrendering control, both in how I worked with people and the technical limitations of the wet-plate collodion process. For me, this helped me understand why I seek out queer images: to access queer possibilities for being in the world. It is especially important as a genderqueer person, because this is still a contested area without legal recognition in most places.

Mokros: It seems to me that, in your practice, seeking out queer images also involves producing queer images. They are disseminated to all your viewers, but might especially resonate with a viewer like me, or other queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming folks. You’re queering our sense of possibility.

Rowan Renee is a lens-based artist working with dynamics of gender and power.

Arno Mokros is a writer and print-based artist and the coeditor of Little Pharma.SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

The post Queer Looking, Queer Being appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 9, 2018

The ’90s are Back

Six artists on the photobook at the end of the millennium.

It was the age of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Friends, grungy flannel shirts and supermodels in Calvin Klein underwear, dial-up modems and fruity-colored iMacs, Lady Di and Tony Blair’s Britain, Bill Clinton’s White House, and the moment when Americans learned what the definition of is is. The fin-de-millennium decade of the 1990s—that “bridge to the twenty-first century”—marked a moment of immense cultural change, most notably with the arrival of the internet and the wired information landscape, the rapid rise of Photoshop, and desktop publishing. The ’90s was also an uncertain moment in photography. Would Kodak and Polaroid survive the leap to digital imaging? Would Corbis and Getty Images control the future of image distribution? Would the interactive CD-ROM become the preferred delivery system for photographers?

In the 1990s, the photobook juggernaut as we know it today was in embryonic form. Its DNA was in place: digital layout, type, and printing techniques were chipping away at the barriers to entry of traditional publishing models. Gerhard Steidl was cutting his teeth as a printer, and working closely with Walter Keller’s Scalo, which made critical contributions to the photobook as a medium. Scalo improved upon traditional models with new titles by Nan Goldin (The Other Side, 1993), Paul Graham (Empty Heaven, 1995; End of an Age, 1999), and Michael Schmidt (U-ni-ty, 1996), as well as with expansive contributions, such the first major monograph on Seydou Keïta (Seydou Keïta, 1997), which remains a touchstone in the world of African photography. Japanese photobooks had begun to reclaim their international stature with titles like Nobuyoshi Araki’s Tokyo Lucky Hole (1990) and Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Suburbia (1998). By the 2000s, advancements in technology allowed for far superior printing and reproduction quality, and DIY publishing became easier than ever. With the saturation of smartphones worldwide and the popularity of tablets and e-readers, the photobook—an object to be held, placed on a shelf, and shared hand-to-hand—may have become all the more valuable, an artwork in itself. Looking back at the decade that began with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, and ended amid the inconvenient truth of the 2000 US presidential election, what did the photobooks from that era mean to photographers coming of age in the 1990s and early 2000s? —Lesley A. Martin and Brendan Embser

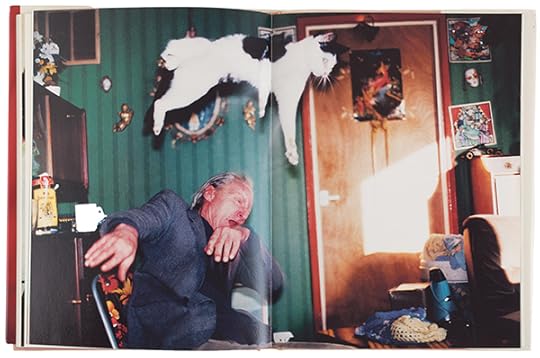

Richard Billingham, Ray’s a Laugh, Scalo, New York, 1996

Laia Abril on Richard Billingham, Ray’s a Laugh

I perfectly recall the first time I saw this book. I remember something ripping through me as I stepped inside Richard’s father Ray’s house, as if I could smell the dampness of the carpet mixed with the sweet-sour taste of overripe fruit, the acidity of alcohol infused with his mother Elizabeth’s tobacco roughness. I remember the intensity of the colors, the overwhelming composition, the stifling layout. I remember turning the pages as if moving through the corridors, facing their unfiltered, raw intimacy and dancing between the hate-love of a tedious routine frozen in time. I remember empathizing with Richard’s frustration, with his own photographic catharsis.

Laia Abril is a multidisciplinary artist.

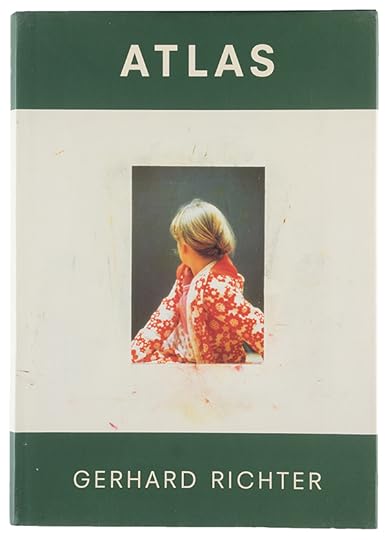

Gerhard Richter, Atlas, Distributed Art Publishers, New York, 1997

Hannah Whitaker on Gerhard Richter, Atlas

Flipping through Gerhard Richter’s Atlas now is different than it was in the ’90s: the gridded image archive lacked the strong association with the digital milieu. Reissued in 1997, it was the time before the proliferation of writing on the proliferation of images. Then, it seemed to say something about negotiating the personal and the universal, apparently a preoccupation of many twentieth-century Germans. Now, its prescience is overwhelming. What has remained constant in looking at Atlas is its defiance of a photograph’s habitual instrumentation—that is, to show, sell, or remember something. Its seemingly endless grids of iterative images show that photographs can also be mute. They can be blunt objects, incapable of meaningful operation outside of a system, like a neuron without a brain.

Hannah Whitaker is a Brooklyn-based photographer.

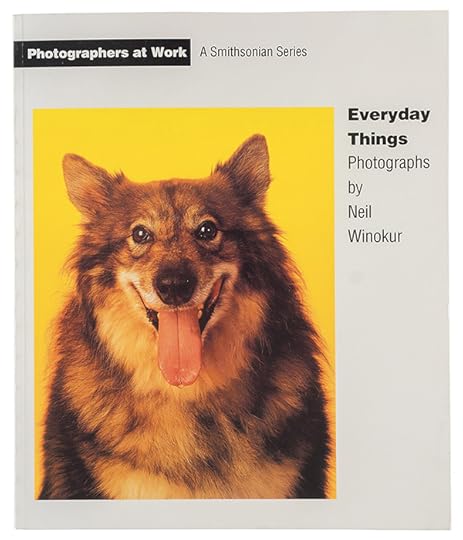

Neil Winokur, Everyday Things, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 1994

Matthew Leifheit on Neil Winokur, Everyday Things

The Smithsonian Institution’s seminal Photographers at Work series published Everyday Things, Neil Winokur’s only monograph to date, in 1994. With an essay by Vince Aletti, the slim paperback abridged Winokur’s vast archive, showing the democratic treatment he continues to give to all objects, people, and animals that cross in front of his camera. In the book’s sequence of images, a portrait of Andy Warhol sits between a close-up of a woman’s shoe and a study of an ear of corn standing on end. They are followed by a toy gun, then a picture of an Irish setter named Doc. A few pages later, one of my favorite photographs of all time is reproduced: a blue, full-frame still life of a cold glass of water, ripe with condensation. All are given the same semi-glamorous, semi-weird isolated treatment against an atmospherically neon-hued background. It’s somewhat like a commercial studio, but less slick, purposefully nodding to the genre of amateur photography, to family snapshots, to the things that actually matter in peoples’ lives. Winokur’s this-equals-that approach to both public and private representation set a precedent for the quasi-commercial work of photographers such as Roe Etheridge, as well as for the torrent of brightly colored still lifes common on websites like Tumblr since the early 2010s.

Matthew Leifheit is a photographer, curator, publisher, and interviewer.

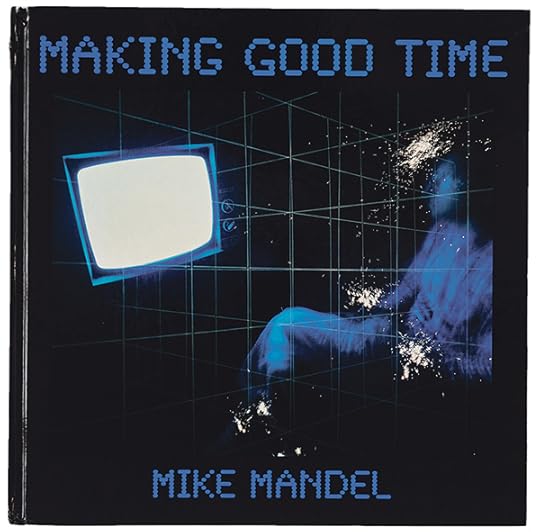

Mike Mandel, Making Good Time, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1989

Clare Strand on Mike Mandel, Making Good Time

Mike Mandel’s Making Good Time currently travels in the trunk of my car. I’ve been driving around with it for the past four years or so, and it has transferred through at least one change of car. I’m an advocate of driving books around and keeping them close. I think of the phrase “book osmosis”—the idea being that one doesn’t necessarily have to read books, but can consume them through close proximity.

Making Good Time is an awkward book. It doesn’t fit well on a shelf—another reason it’s in my boot—and with its glossy, hardback cover, it has the object quality of a withdrawn local-library book that has been sold off in a charity store. This is partly why I like it.

I bought Making Good Time in 2004, when I was researching a new work, The Betterment Room: Devices for Measuring Achievement, which referenced the savvy American husband-and-wife team Lillian and Frank Gilbreth. I attached a homemade set of lights to my hands and recorded the act of making a photograph—the intangible rendered tangible, or perhaps the tangible made intangible; I’m still working out if there is a difference when it comes to photography. Ideas and propositions seem central to Mandel’s work—making photographs for the stomach, which then direct the eye. Mandel’s oeuvre, for me, rejects visual repetition and “styles” in favor of the need to understand the photographic medium, and, more important, the idiosyncratic nature of life. With its absurdist aims and disco lighting, Making Good Time is a perfect example.

Clare Strand is a British conceptual photographic artist based in Brighton, England.

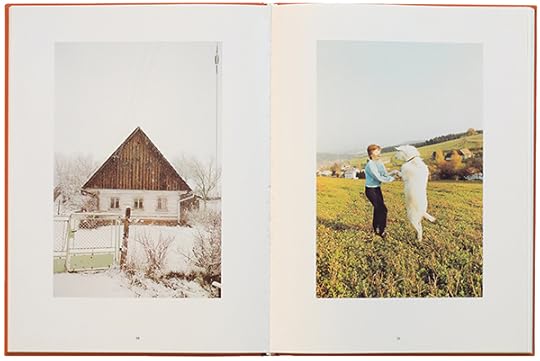

Jita Hanzlovà, Rokytnik, Museum Schloss Hardenberg, Velbert, Germany, 1997

Gregory Halpern on Jitka Hanzlová, Rokytnik

One of the great, underrated photobooks of all time, Rokytník consists of pictures Jitka Hanzlová made in her hometown, Rokytník, Czech Republic, in the early 1990s. Between 1982 and 1990, Hanzlová lived in Germany, in exile from the Communist regime that had taken power in her homeland. When Communism fell, she returned to Rokytník and began this work, photographing old acquaintances, neighbors, and other people known to her family. The passage of time—and its losses—are ever-present in the work: the book opens with a clothesline in summer and ends with the same clothesline in snow. She disproportionately photographs children and old people, and she does so with a kindness and sensitivity that steers clear of romanticism. Her photographs of children are particularly profound, as they manage to describe the vulnerability of childhood as well as its pleasures and wonders. A direct, powerful work that never tries too hard, Rokytník’s power lies in the visual glory of what simply is. Unlike any other, this book reminds me that simplicity—in style, form, and concept—is powerful when the content is good.

Gregory Halpern is a photographer who published five photobooks of his work, including ZZYZX (MACK, 2016).

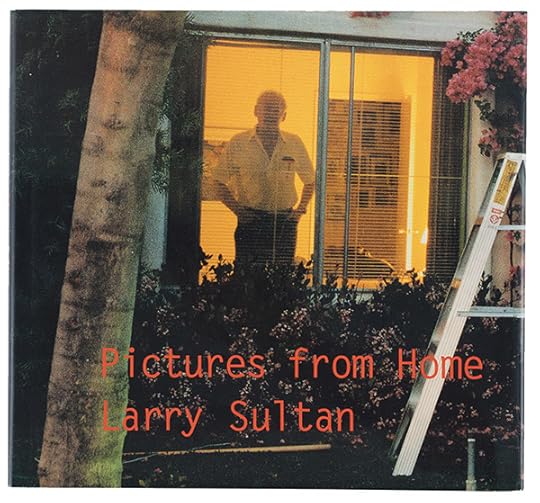

Larry Sultan, Pictures from Home, Abrams, New York, 1992

Hank Willis Thomas on Larry Sultan, Pictures from Home

When I was a student at NYU, I was a library monitor, so I sat in a room full of photobooks and had nothing else to do because there was no internet. I looked through photobooks all day throughout my shift and that was really what gave me an encyclopedic knowledge of ’80s and ’90s photobooks. Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home was in a lot of ways inspiration for my book Pitch Blackness, about my cousin’s murder and my family’s—and my own—response to that. Larry’s book made the personal and private, public. It showed a level of vulnerability of the artist, and his family members as collaborators in the making of the work. I think Pictures from Home really helped me to see how a photographic project can actually translate beyond just what happens in the camera, and what’s presented in a book, through the use of text, interviews, and archival images as well as the photographs that Larry took. I think it really taught me a lot about how multifaceted a photobook can be.

Later, I went to go see Larry give a talk about his work and collaborations with Mike Mandel; that, and also seeing Jim Goldberg talk about Rich and Poorand Raised by Wolves, led to my going to the California College of the Arts and to Larry’s becoming my mentor and friend.

Hank Willis Thomas is a conceptual artist based in Brooklyn.

The post The ’90s are Back appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

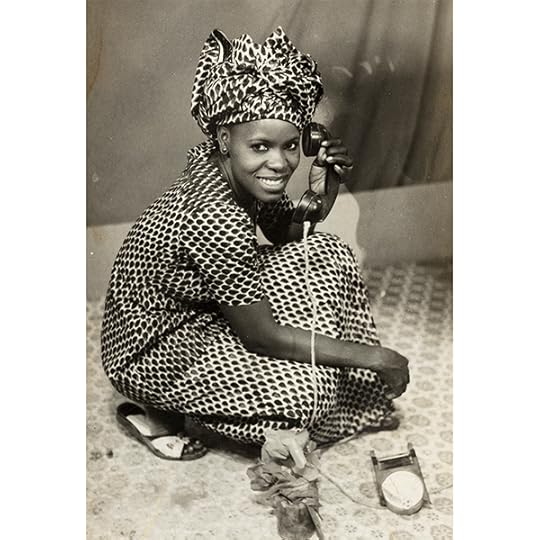

Starring Sanlé Sory

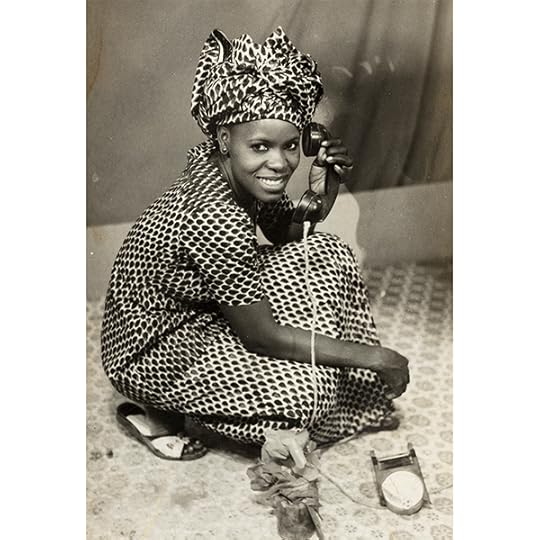

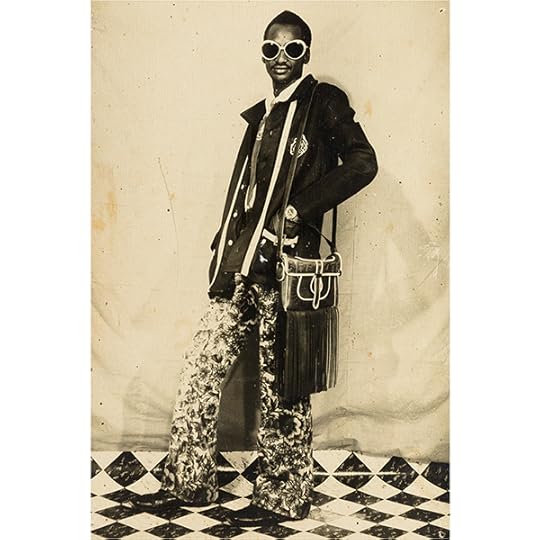

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, Untitled, 1965/75

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni

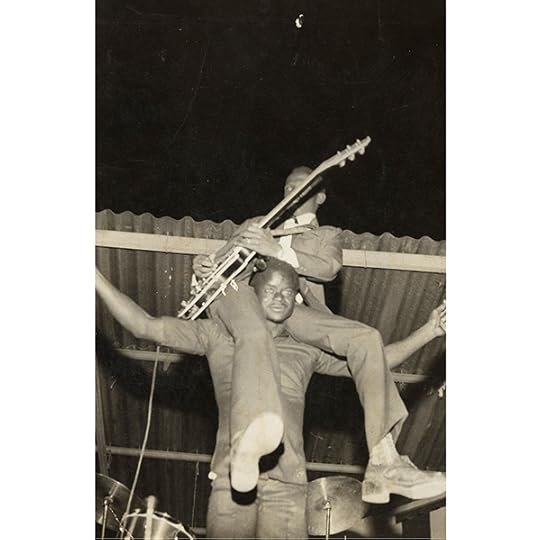

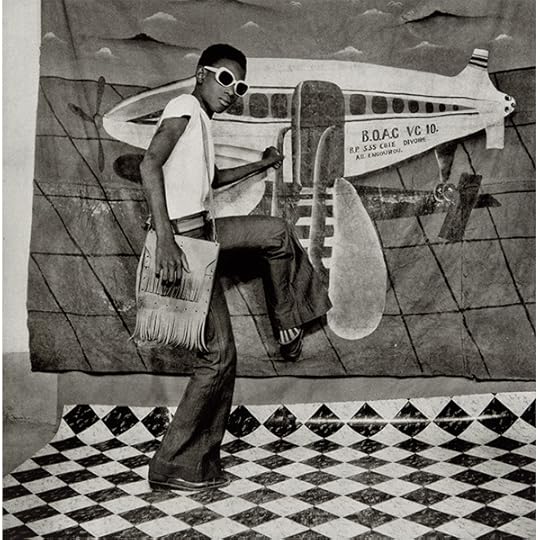

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, Tiamodjan, the lead guitarist for Echo del Africa Nacional, 1965/75

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni

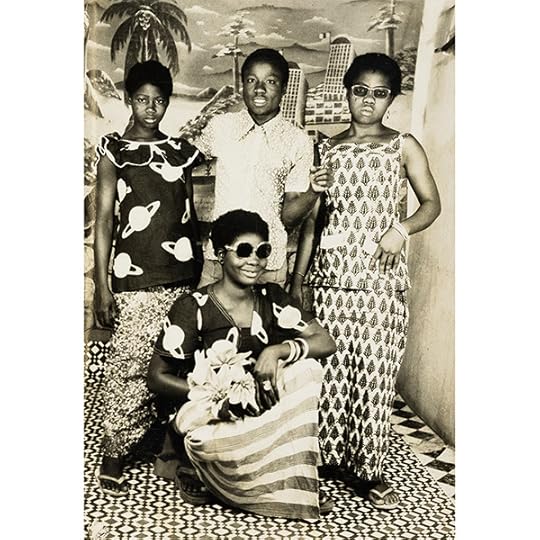

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, Untitled, 1965/75

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni

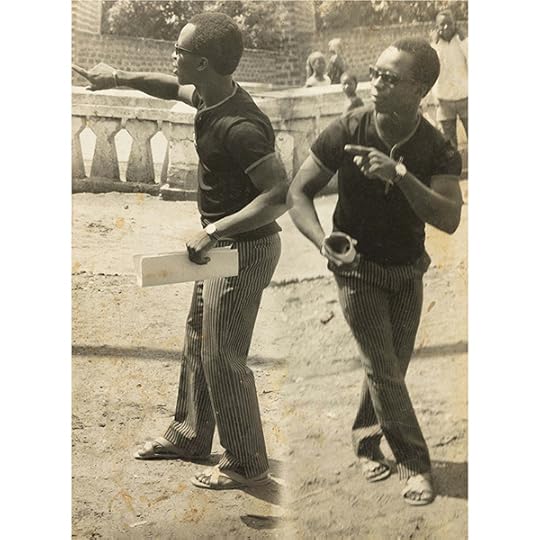

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, Double-exposure self-portrait in Place du Paysan Noir (Black Farmer Square), ca. 1970

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni.

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, A Fula man, 1970/80

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, Untitled, 1965/75

© the artist and courtesy Florent Mazzoleni

The full title of the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition Volta Photo: Starring Sanlé Sory and the People of Bobo-Dioulasso in the Small but Musically Mighty Country of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) speaks to the depths of the relationship between Ibrahima Sanlé Sory and the communities he photographs. Customers flocked to the portrait studio Sory opened in the style-conscious city of Bobo-Dioulasso around 1960, the year the West African Republic of Upper Volta gained independence from France. Volta Photo gathers approximately eighty, mostly vintage photographs of the 1960s and 1970s, together with photographic album covers from the era. The exhibition also includes Sory’s signature painted backdrop, along with studio lamps and props that he still uses today. As Sory says, in his studio “religious people, artists, musicians, and everyone could become a hero.”

Volta Photo is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through August 19, 2018.

The post Starring Sanlé Sory appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 3, 2018

Man Ray as You Don’t Know Him

Rediscovering the surrealist artist’s Unconcerned Photographs.

By Simon Baker

Man Ray, Unconcerned Photograph, 1959

© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London

In 1960, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) held The Sense of Abstraction, its second show on the relationship between photography and abstract art in under ten years. Following Abstraction in Photography, in 1951, which mixed scientific and fine art photographs, The Sense of Abstraction shifted direction, redefining the topic at hand. The curatorial approach of the 1960 show was bolstered by the international profile of Abstract Expressionism, particularly the posthumous celebrity of its fastest burning star, Jackson Pollock. MoMA curator Grace Mayer brought together three hundred works by over seventy artists, with many names that one would expect at this time, such as Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, and Frederick Sommer, but also with a look back to the generation of László Moholy-Nagy, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Weston.

Recently, while researching in MoMA’s collection, I was not surprised to find Man Ray on this list of artists, but the body of work appearing with his name, Unconcerned Photographs (1959), was unfamiliar to me. In response to Mayer’s invitation to contribute to The Sense of Abstraction, Man Ray sent MoMA a group of Polaroids produced by swinging the camera around on its strap in his Paris studio. He indicated very minimal cropping instructions and suggested that they be reproduced as gelatin-silver prints. The museum then ordered seven Masonite-mounted enlargements for the exhibition, so that, as objects, they would sit happily alongside the works of Man Ray’s contemporaries.

Man Ray, Unconcerned Photograph, 1959

© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London

It’s interesting, however, to reflect on the fact that both the process and title of Man Ray’s contribution ran counter to the prevailing values of most of the photographers celebrated in The Sense of Abstraction, for whom painstaking composition and exceptional printing were de rigueur. Could it be that Man Ray’s Unconcerned Photographs were offered to MoMA with more than a hint of an ex-Dadaist’s wink? And that the relative lack of concern, since 1960, for this body of work suggests a deeper poetry in Man Ray’s sense of abstraction than even he might have dreamed possible? With the inclusion, more than fifty years later, of Unconcerned Photographs in the 2018 Tate Modern exhibition Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art, Man Ray finally finds himself in the company not just of photographers, but of the painters and sculptors who contributed to the invention of abstract art.

Simon Baker is Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), Tate.

Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art is on view at Tate Modern, London, May 2–October 14, 2018.

The post Man Ray as You Don’t Know Him appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 2, 2018

Southern Futures

Mark Steinmetz’s project on the Atlanta Airport portrays the American South in all its complexity and contradiction.

By Izzy Leung

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

The most recent iteration of the High Museum of Art’s Picturing the South series features the work of Mark Steinmetz, originally from Athens, Georgia, who focused his project on Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. In one of the world’s most heavily trafficked airports, Steinmetz explores the paradox of the space as the crossroads of Southern identity, both in the mainstream and on the periphery. The sixty hazy, black-and-white photographs featured in the exhibition imagine the South in a new light, and ask questions about the future of southern photography. I recently spoke with Gregory Harris, the High Museum’s assistant curator of photography, about the show.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Izzy Leung: Can you tell us about the history behind the Picturing the South series?

Gregory Harris: The Picturing the South project was initiated in 1996 to coincide with a major survey of southern photography in order to bring some new, fresh work into the exhibition. The first artists commissioned were Sally Mann, Dawoud Bey, and Alex Webb, and the the project has continued to roll from there. The South has had a fairly significant role in the history of photography, with the photographs that Walker Evans and William Christenberry both made in Hale County, Alabama, the photography of the civil rights movement, being some notable examples. At the High, we try to emphasize the South’s place within the history of photography as a subject that has been compelling to people who are natives of the region, but also for people from other parts of the country and the world. The commissions are a way we can add to that ongoing conversation.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: So, in order to properly picture the South, why did the High Museum choose photography, rather than a different medium?

Harris: Photography may not seem like an obvious answer, but I can’t think of a medium that’s better suited for telling stories and representing the region. A lot of the work that has come out of this commission has been documentary in nature. Richard Misrach’s long-term examination of “Cancer Alley” along the Mississippi River is a great example. There have been some artists who have taken a more experimental approach, like Sally Mann, who started seriously investing in the collodion process in relation to the Southern landscape. Abelardo Morell made pictures using mirrors and frames set in some of the natural environs around Atlanta. But, for the most part, it’s been a representational documentary project. Photography gives artists a way to articulate a distinct vision and a distinct approach to whatever subject matter they happen to be dealing with.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: How are Mark Steinmetz’s images representative of the South? What about the Atlanta airport conveys something greater about the South?

Harris: Mark’s pictures position Atlanta as a global hub. The Atlanta airport is the busiest airport in the world—you can get basically anywhere from Atlanta. By digging into that idea, he’s looking at a contemporary South that is a player on a global stage. Between the music, film, and art scenes, which are all definitely becoming more robust, Atlanta has developed an outsized cultural presence. Despite the fact that it’s a relatively small city, Atlanta is a major hub for a lot of activity on a national and global scale, and the airport is in some ways a mechanism and also a metaphor for that activity. Mark presents the airport as a paradox, contrasting the human-made with the natural world, the public with the private. That kind of complexity and contradiction are emblematic of a region as large and varied as the South.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: The title of Steinmetz’s series, Terminus (2018), positions the city as the end of the line or the terminating point, yet, as you said, maintains Atlanta as an intersection of culture and transit. How do you think the word terminus fits into the vision of his project and the cultural history of Atlanta at large?

Harris: Terminus comes from the original name of the city when it was built at the intersection of two railroad lines. Since its founding in the 1830s, Atlanta has been this intersection for various kinds of transportation, moving people and goods around the region and country.

One of the things that interested Mark about the airport is that it is a liminal place where people are leaving one place behind and going off to another. Thinking more broadly or metaphorically, they could be leaving one chapter of their life behind and starting off on a new adventure. A lot of Mark’s work looks at people and places on the margins of the mainstream, and the edges of cities. He takes a lot of pictures on the road, particularly on highways. The highway becomes a metaphor for transition and a way of expressing a longing for something. The airport fits in perfectly—it is literally at the edge of the city; it’s something that despite its size and how busy it is, it’s still peripheral to our everyday thinking. The airport is so outside normal, everyday life for many people that they have a different kind of experience in the airport. In the pictures that Mark took of people, they’re almost completely lost in thought, often alone, or if they’re near other people, they are gazing out a window, or looking at their phone. They are lost in their own world, disconnected and lost in contemplation.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: When Mark was taking the photographs, was he in the midst of traveling, or did he make special trips to shoot?

Harris: For the most part, Mark made the photographs during his normal travel. He would arrive at the airport early or stay late after a flight and make pictures while he was waiting. He also didn’t get any special access for anything he was shooting. There are no pictures of security checkpoints or behind-the-scenes areas. Everything he photographed is open and accessible to the public. He didn’t make many special trips, with the exception of the times he went to shoot in the neighborhood at the edges of the airport that are completely overgrown by kudzu and trees. There are also several pictures he made at night from a hotel that is located along the runway. He would get a room that overlooked the runways, set up a tripod, and make long-exposure pictures of the planes taking off and landing.

Mark tends to make his work wherever he happens to be, and out of whatever is happening around him. There’s no staging or setup—it’s intuitive and improvised. He’s very much an old-school photographer in that vein.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: What can we expect to see from the next two Picturing the South exhibitions, featuring Debbie Caffery and Alex Harris?

Harris: Those commissions are both still ongoing. Debbie is pretty close to completing her commission. She photographed agricultural communities in the Mississippi Delta that, over the last twenty to thirty years, have rapidly been losing population as the economies have shifted and people have moved into urban centers. Debbie’s work is very emotionally charged and evocative. She shoots in black and white and has an amazing sense of light and tonality that creates a mood that give the pictures an edge.

Alex Harris has been photographing on independent film sets throughout the South. He is really interested in how the South is portrayed in cinema. He was the set photographer for Steven Soderbergh’s film about Che Guevara and that sparked his interest in shooting on film sets. Alex has been photographing in ways that reveal the artifice of the production while also photographing the scenes themselves as they’re being acted out in such a way that you might never know he was on a film set. Some of these pictures clearly have a melodramatic quality that almost look like a Jeff Wall. It’s clear that something is being played up for an audience of one kind or another. The ways that he’s playing with narrative and artifice is really exciting.

Mark Steinmetz, Untitled, 2015

© the artist and courtesy Jackson Fine Art, Atlanta, Georgia

Leung: The two upcoming photographers are distinctly from the South, whereas previously commissioned photographers, such as Martin Parr, Richard Misrach, and Alex Webb, are not. How does this change the project?

Harris: There had been a lot of discussion amongst the photography community here in Atlanta, in which people asked, “Why have there not been more southern photographers who have received this commission? Why aren’t we celebrating and highlighting the talent that is here in the region?” So with this group, there was a conscious choice made to commission artists who are from the South. But, historically, our curators have used the projects as a way to collaborate with some of the most prominent and promising contemporary photographers and give them an avenue to create new bodies of work and try out something new, whether that’s a new process or a new subject. The commission is a way to open up possibilities and present opportunities for artists to engage with the southern landscape and culture.

I think one of the things that the High’s photography program has done really well over the years is to look closely at the South, but to do so in a way that isn’t provincial. We show work from all over the country and across the world, and place that in conversation with the unique, complicated history and culture that is characteristic of the South. To embrace the region, but not at the expense of everything else that is going on in the wider world.

Izzy Leung is the editorial work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Mark Steinmetz: Terminus is on view at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, through June 3, 2018.

The post Southern Futures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 30, 2018

Behind the Scenes at Foam Talent

During a private tour at Red Hook Labs, Aperture Members learned the about up-and-coming photographers taking the field by storm.

On Saturday, March 24, Aperture Patrons and Members met at Red Hook Labs for a private viewing of the annual Foam Talent exhibition, hosted by the Amsterdam-based, internationally operating photography museum. Since 2007, Foam has organized a yearly scout for “exceptional talent,” which includes a traveling exhibition, a dedicated magazine issue, and the possibility of entering the Deutsche Börse collection. The call has, in artistic deputy director Marcel Feil’s words, a very simple premise: “If you are a photographer and you think you have talent, let us know, share your work!”

Feil began by presenting the organization and its vocation of being an “open house for photographers and photography.” Feil also stressed that one of their foremost concerns is to display a broad range of work covering diverse subjects, areas, and styles so as to better grasp the state of photography today, while highlighting current trends. After describing the process of narrowing down the submissions, Feil presented each of the featured artists. Some photographers are absolute newcomers, such as Weronika Gęsicka, whose playful and surreal collages comment on the constructed role-playing in the television-mediated image of suburban baby boomer lives, and Wang Nan, who photographs her young pupils’ uncanny imagination as a means of helping them unleash their potential in a repressive school system.

Others, like Vasantha Yogananthan and Erik Madigan Heck, have enjoyed their fair share of online and festival attention. Yogananthan’s ambitious project A Myth of Two Souls(2013–ongoing) reinterprets the epic poem The Ramayana’s prevalence in contemporary Indian culture, while Heck’s futuristic and minimalistic fashion images explore ideas of beauty in an industry both influenced and burdened by art history. Feil provided insightful keys for engaging with the projects and explained why Foam decided to bring these artists to wider art-world attention. Despite the intention not to constrain the exhibition to a particular genre, Feil noted a tendency among some of these emerging photographers to channel our society’s topical concerns in an engaged and almost activist way.

At the end of the tour, each Patron and Member received a copy of the current issue of Foam and enjoyed snacks and wine. Participants were able to ask questions, talk about photography and the work they’d had the chance to discover with Feil, and chat with each other in an informal and convivial atmosphere.

The Photographers Selected for Foam Talent 2018:

Sushant Chhabria (India), David De Beyter (France), Mark Dorf (USA), Alinka Echeverría (Mexico/UK), Weronika Gęsicka (Poland), Wang Juyan (China), Thomas Kuijpers (The Netherlands), Quentin Lacombe (France), Clément Lambelet (Switzerland), Namsa Leuba (Switzerland/Guinea), Erik Madigan Heck (USA), Alix Marie (France), Martin Errichiello and Filippo Menichetti (Italy), Wang Nan (China), Kai Oh (South Korea), Viacheslav Poliakov (Ukraine), Ben Schonberger (USA), Sadegh Souri (Iran), Harit Srikhao (Thailand), and Vasantha Yogananthan (France).

Click here to join Aperture’s membership program or contact our membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post Behind the Scenes at Foam Talent appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 26, 2018

The Photographer’s Hand in a Digital World

An exhibition at the Getty deconstructs an identity crisis in contemporary photography.

By Travis Diehl

Matt Lipps, Models, 2016

© the artist

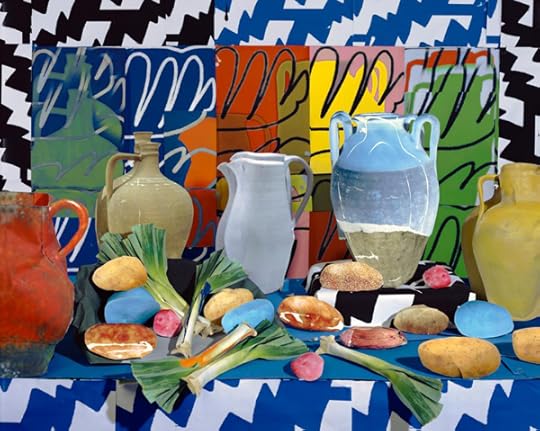

The J. Paul Getty Museum’s exhibition Cut! Paper Play in Contemporary Photography gathers together six artists whose work over the past decade is coping with an identity crisis in photography. In the nineteenth century, the daguerreotype offered jewel-like uniqueness to match that of painted portraits, while today, artists’ attention to (and even assault of) C-prints pits another sort of physicality against the mass dissolution hastened by digital process. Each of the six artists of Cut! leverages their handiwork against the anonymity of the apparatus. See, for instance, Photographers (2013), a large-format image by Matt Lipps: lining glass shelves like paper dolls are cutouts from the work of the great auteurs—a nude by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, a twisted tree by Edward Weston, a skull made of nude women by Philippe Halsman. The work glorifies the paper-ness of photography at a time when paper is less and less a factor. Nostalgia and appreciation intermingle, and Lipps’s mastery of color lighting and color printing techniques—the figures floating like crisp grayscale ghosts above an aquamarine wash—constitute less a deconstruction of and more an homage to the “straight photograph.” Likewise, Daniel Gordon’s still lifes of “fruit” and “vegetables” collaged into the round from chopped-up color photos inflate the medium into brilliant, volumetric space, only to collapse it again.

Daniel Gordon, Potatoes and Leeks, 2016

© the artist and courtesy M+B Gallery, Los Angeles

In this self-aware spirit, the photographers of Cut! uphold the medium’s investment in the significance/signification of even minor things. In a 2012 series shot in the Getty Research Institute’s archive, Thomas Demand zooms in on paper-and-plastic models by the architect John Lautner, making lush abstractions of their rust-red, dusty planes. Similarly, his impressively lush and fine-grained Landscape (2013) appears to glorify the sheer mundanity of a patch of ground cover. Yet what the image actually depicts—an intricate, life-size paper diorama—brings with it the untold work hours of Demand and his assistants, cutting and folding all those shades of green.

Soo Kim, Midnight Reykjavík #5, 2005

© the artist

Where the subject itself isn’t hand-rendered, the artist’s hand embellishes the mechanical result. Soo Kim creates intricate latticeworks from layered photographs of cities and wharves by making incisions according to the logic of the image—for instance, in Midnight Reykjavík #5 (2007), by excising the flat planes of walls and roofs. This subtractive collage thus maintains a relationship to the subject’s geometry, while rendering the glass a window; Kim’s landscapes are as aware of the wall as they are the frame, folding the structures they depict into the structures on which they hang. In comparison, optically ambiguous, geometric 3-D collages of cut photographs by Christiane Feser pop both visually and physically into space. Where this (faux) tromp l’oeil becomes its own virtue, clever formalism is given undue substance by calling it “play.”

Christopher Russell, Budget Decadence, 2008

© the artist

Indeed, it’s no great revelation on its own that the photographic process is plastic and fungible at all points. While many of these artists leverage the objecthood of the photograph to reach smart new territory, others seem to slash out blindly for a novel approach. Among a series of five prints of an interior window by Christopher Russell, variously augmented with razor points, dirt, and semen (only three are on view), is Budget Decadence (2008), an “Ultrachrome print hacked with meat cleaver.” Russell’s other selections nod to the artifacts of the medium, such as Explosion #31 (2014), in which he scratched tattered arabesques into a print of a lens flare, and Mountain XXIX (2017), where a cloth veil draped over a perfectly configured, high-end lens produced a gossamer blur. It’s hard to get excited about a photographer’s efforts to frustrate their own equipment, but worth noting that, even so, they keep making photographs.

Travis Diehl is a critic based in Los Angeles.

Cut! Paper Play in Contemporary Photography is on view at the Getty, Los Angeles, through May 27, 2018.

The post The Photographer’s Hand in a Digital World appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Abbas (1944–2018)

Aperture remembers the legendary photographer.

By Chris Boot

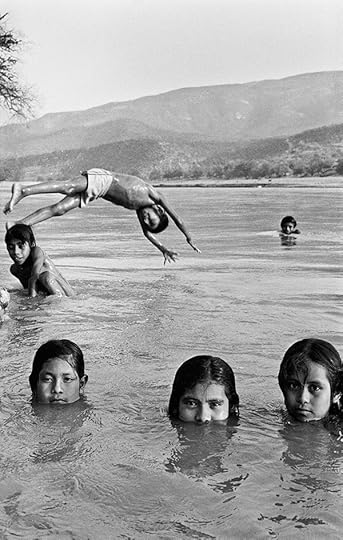

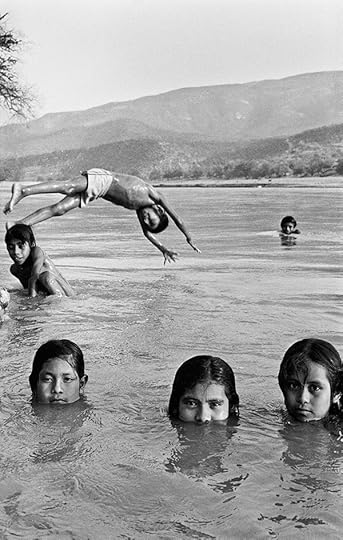

A. Abbas, Children bathe and play in the Rio Balsas, Village of San Augustin de Oapan, Mexico, 1985

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Abbas’s practice as a photographer was forged on the frontlines of war and revolution during the 1970s, when he was working as part of the Sipa and Gamma news picture agencies, which were then at the peak of their influence and economic power. After ten years as one of the most successful agency photographers of his generation, Abbas sought the kind of independence and scope for visual authorship that Magnum could offer. Master of the picture story format, he made tight, singular, and particularly useful icons of conflict and society that made his pictures among the most reproduced of the Magnum group during the 1990s. He simultaneously pursued his own visual poetry, particularly in Mexico, and drew on his experience of war to pursue a comprehensive documentary account of the world’s religions over thirty years. Take any single picture or story from this major work, and one assumes Abbas both detached and neutral. But take the body of work as a whole, and one sees Abbas treat religious fury not only as one of the great themes of our time, loaded with visual opportunity, but instead as cause for much of the world’s suffering. Abbas was larger than life, a unique character among Magnum’s larger-than-life roster. One of its leaders, one pictures him at Magnum meetings stroking his beard, gravely, while pondering the path ahead. Photography will miss him.

Chris Boot is the executive director of Aperture Foundation.

The post Abbas (1944–2018) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A. Abbas (1944–2018)

Aperture remembers the legendary photographer.

By Chris Boot

A. Abbas, Children bathe and play in the Rio Balsas, Village of San Augustin de Oapan, Mexico, 1985

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Abbas’s practice as a photographer was forged on the frontlines of war and revolution during the 1970s, when he was working as part of the Sipa and Gamma news picture agencies, which were then at the peak of their influence and economic power. After ten years as one of the most successful agency photographers of his generation, Abbas sought the kind of independence and scope for visual authorship that Magnum could offer. Master of the picture story format, he made tight, singular, and particularly useful icons of conflict and society that made his pictures among the most reproduced of the Magnum group during the 1990s. He simultaneously pursued his own visual poetry, particularly in Mexico, and drew on his experience of war to pursue a comprehensive documentary account of the world’s religions over thirty years. Take any single picture or story from this major work, and one assumes Abbas both detached and neutral. But take the body of work as a whole, and one sees Abbas treat religious fury not only as one of the great themes of our time, loaded with visual opportunity, but instead as cause for much of the world’s suffering. Abbas was larger than life, a unique character among Magnum’s larger-than-life roster. One of its leaders, one pictures him at Magnum meetings stroking his beard, gravely, while pondering the path ahead. Photography will miss him.

Chris Boot is the executive director of Aperture Foundation.

The post A. Abbas (1944–2018) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

From Gaza to Florida

At Aperture’s gallery, Palestinian photographer Taysir Batniji discusses his new book and exhibition, Home Away from Home.

Taysir Batniji, Cathy Kaplan, Chris Boot

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Catherine Tsekenis, Taysir Batniji, Sophie Jaulmes-Batniji, Peter Malachi

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Catherine Tsekenis, Taysir Batniji, Sam Stourdzé, Chris Boot

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Safa Batniji, Vanessa Leiva Santos

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Yazam Khalili, unknown, Rima Abdul-Malak, Taysir Batniji, Sophie Jaulmes- Batniji

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

Omar Batniji, Kamal Batniji, Turkya Batniji, Safa Batniji, Taysir Batniji, Sophie Jaulmes Batniji, Saleem Batniji

Madison Reid © Aperture Foundation

On March 17, 2018, Aperture Foundation and the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès presented a talk with Aperture’s executive director Chris Boot and photographer Taysir Batniji about his new book and exhibition, Home Away from Home. Guests congregated in Aperture’s Chelsea gallery for the third and final installment of Immersion, a French American Photography Commission, a joint project by Aperture and Hermès.

Home Away from Home is a singular and intimate portrait of Batniji’s own familial diaspora. Born in Gaza, Batniji now lives and works in France. His most recent work explores the idea of home through visits with several family members who have relocated to the U.S. In the book and exhibit, he brings together photographs, documents, drawings based on his memories, videos from interviews, and selections from his family’s archives to explore a sense of dislocation and a state of “between-ness,” both culturally and geographically. The resulting body of work questions what it means to share a history—even among relative strangers—and what happens to the sense of past and of belonging when opting for new identities and homes.

Boot and Batniji’s conversation began with a philosophical discussion on the state of photography—authorship, methods of presentation, technicalities, and appropriation. Batniji then spoke about his photographs of Israeli military watchtowers, taken along the edge of Gaza and formatted into a grid-like sequence, which references Bernd and Hilla Becher, in particular Water Towers (1972–2009). After the watchtowers series, Batniji photographed the war-torn and uninhabitable homes in Gaza following the 2008–9 Israeli attacks. Borrowing from the commercial language of the real-estate industry, Batniji pairs photographs of rubble-strewn homes with descriptions such as, “living room, dining room, kitchen, 2 bathrooms/wc. 900m2orchard of olive trees, fig trees, vines, and a fountain. Garage in the garden. Unrestricted sea view. Inhabitants: 5 families (23 people).”

Batniji describes his work as dealing with life and with people. Politics and conflict exist in, but are not illuminated by, his images; his work doesn’t masquerade as political speech. Batniji notes, “Walls and suffering, they are inescapably there, but juxtaposed to this is life. Even in the middle of conflict is modernity.”

Taysir Batniji (born in Gaza, 1966) trained as a painter at An-Najah National University, Nablus, prior to continuing his studies in France at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Art de Bourges, and the École Supérieure d’Art et de Design Marseille-Méditerranée. His work incorporates drawing, video, photography, and installation, and has been shown widely in Europe and the Middle East, including at the Venice Biennale; Jeu de Paume, Paris; Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; Kunsthalle Wien; and Witte de With, Rotterdam.

Home Away from Home is copublished by Aperture and the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès on the occasion of Immersion, a French American Photography Commission. Taysir Batniji: Home Away from Homeis on view at Aperture Gallery through May 10, 2018.

Click here to join Aperture’s membership program, or contact our membership office at 212.946.7108 or membership@aperture.org.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post From Gaza to Florida appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers