Aperture's Blog, page 106

January 10, 2018

The PhotoBook as a Literary Form

Teju Cole’s first photobook unfolds the possibilities of text and image.

By Rick Moody

Is there not a formidable hybridization going on these days that conjoins literature and photography?

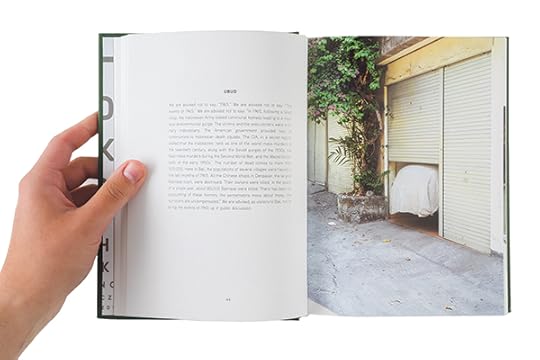

Teju Cole’s Blind Spot, a moving and playful fusion of text and image, would appear to be a solid contribution to this emerging hybrid activity (whose origins perhaps lie in books like Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by James Agee and Walker Evans, or in the novels of W. G. Sebald). Its structure is as follows: an image on recto, usually a lightly abstracted image, almost always an image without a face (that is, not a portrait), and only occasionally an image with a figure, often an image that contains landscape, often an image that contains drapery, sometimes an image that contains some portion of an automobile, often an image of Northern Europe, though some-times of Africa and the United States of America, Beirut, São Paulo, etc.

Teju Cole, New York City, May 2015

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

And on the verso, there is text. The text is usually slugged to a subhead of place-names. “Poughkeepsie,” for example, or “Lagos,” or “Berlin.” (There is quite a bit of Berlin.) Beneath each sub-head is a short meditation, which comments on the photograph on the recto. Usually, it’s fair to say, the text depends upon the image and enlarges the signifying field of the image.

Sometimes the images turn up twice, as if they have yet to be fully described, as if the book is circling back to certain images. The writing, generally, is allusive, and accomplishes its mission via implication, discretely, as opposed to the kind of accumulation that we would call a story, which is to say a development of preordained meanings in time. There is a diaristic accumulation of the first person here, but it’s by no means certain that the first person is Teju Cole, the author. It could be a constructed Teju Cole, a refraction of the actual Teju Cole, especially given the author’s past as a writer of fiction. Because the book concerns itself with travel, or at least with the appearances of an apprehensible global field of destinations, assembled fragmentarily, it feels most relevant to think of the first-person narrator simply as a traveler. Or: the one who both travels and gazes upon.

Teju Cole, Blind Spot, Penguin Random House

New York, 2017

Sometimes the texts feel philosophical in ambition, and the clearest layer of influence would seem to be, e.g., the Roland Barthes of A Lover’s Discourse (1977) or Camera Lucida (1980). There are also emanations of Adorno and Nietzsche. Sometimes the texts feel like prose poems, or flash fictions. Perhaps, inevitably, there is the trace of Calvino’s celebrated novel Invisible Cities (1972), another genre-less work of literature that can be read in nearly any order and in which there is little conventional character work.

As with Calvino’s revolutionary text, Blind Spot makes possible improvised reading. In this way, the work feels musical, or, perhaps, it is structured like the Internet is structured. It encourages alternative engagements, impulsivities, lateral associations. The photographs flourish in this engagement. They inhabit multiple spaces and meanings. My one-year-old son, for example, took a great interest in Blind Spot, because of its heavy photo paper and handsome green exterior. I found him paging through the book repeatedly. On at least one occasion, however, he was reading it upside down. Is it the case that this approach to consuming the book was entirely out of line? We should travel in the book, as the book travels in the world.

Formally, then, Blind Spot is ingenious, conceptually rich, and original. You might make the distinction here that the texts, no matter how amiable, how casually brilliant, are art-historical texts, in that they are often concerned with illuminating or contextualizing the images. Or would that be another way to consign this work to taxonomy? And yet: its deconstructing of literary genre (is it a travel book, or a book of essays, or a book of prose poetry?) is like Achille Mbembe’s Critique of Black Reason (2017), wherein he writes: “The demotion of Europe opens up possibilities for critical thought.” The blurring of genres feels, in Blind Spot, like a restatement about how meaning is generated. It is both evidence of an unfolding of possibilities with respect to meaning, and about the relatedness of polysemic literature and image making.

Teju Cole, Capri, June 2015

Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

“Losing myself in the city during those aimless walks,” Cole says in a chapter entitled “Brooklyn,” “I encounter chimeras made of lexical fore parts and material hind parts.” This would seem to be an allegory for the book itself. Blind Spot is an aimless walk (that is, organized in discrete and fragmentary sections), and it does mix “lexical” engagements on the left with “material” engagements on the right, though as usual in postmodernity, any oppositional arrangement is provisional and subject to change.

In a way what I imagine Cole is saying in “Brooklyn” is that these chimeras, though perhaps exotic at first blush, might be more aptly fitted together than anyone would have hitherto guessed back at the dawn of the camera obscura.

Rick Moody is the author of five novels, an award-winning memoir, and collections of short stories. His second novel, The Ice Storm (Little, Brown and Company, 1994), was adapted for the screen in 1997. His most recent published work is the novel Hotels of North America (Serpent’s Tail, 2017).

Teju Cole’s Blind Spot was shortlisted as part of the 2017 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. The exhibition of all shortlisted books is on view at Aperture Gallery from December 9, 2017 – February 2018.

The post The PhotoBook as a Literary Form appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

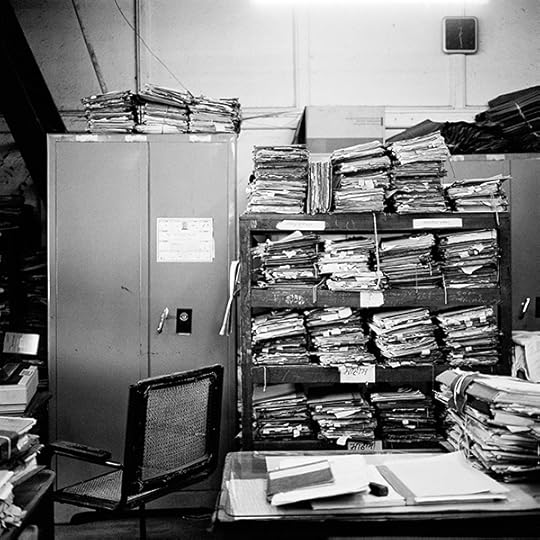

How Can Images Tell the Story of Mass Incarceration in the US?

Aperture Magazine Announces “Prison Nation” Issue, Exhibition, and Public Engagement Series

Most prisons and jails across the United States do not allow prisoners to have access to cameras. At a moment when 2.2 million people are incarcerated in the US, 3.8 million people are on probation, and 870,000 former prisoners are on parole, how can images tell the story of mass incarceration when the imprisoned don’t have control over their own representation? How can photographs visualize a reality that disproportionately affects people of color, and, for many, remains outside of view?

This spring, Aperture magazine will release “Prison Nation,” addressing the unique role photography plays in creating a visual record of this national crisis. Organized with the scholar Nicole R. Fleetwood, this landmark issue will be accompanied by a related exhibition from February 7 through March 7, 2018, as well as a series of six public programs—featuring speakers such as Nigel Poor, Jamel Shabazz, Deborah Luster, Bruce Jackson, Jesse Krimes, Sable Elyse Smith, Joseph Rodriguez, and more—all to take place at Aperture Foundation’s gallery.

Incarceration impacts all of us. “Americans, even those who have never been to a prison or had a relative in prison, need to realize that we are all implicated in a form of governance that uses prison as a solution to many social, economic, and political problems,” Fleetwood notes. Empathy and political awareness are essential to creating systemic change—and through Aperture magazine, and the accompanying exhibition and public programming, “Prison Nation” may provoke us to see parts of ourselves in the lives of those on the inside.

Prison Nation: Public Programs

In a six-part series of programs, photographers, writers, historians, and activists discuss the unique role photography, art, and storytelling play in understanding and creating a dialogue around the crisis of mass incarceration in the United States.

Nigel Poor, Prison Rock Band, June 26, 1975

Courtesy the artist and Haines Gallery, San Francisco

Narratives from Inside

Wednesday, February 7, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Panelists: Nigel Poor, Virginia Grise, Vee Bravo, Russell Craig

How can storytelling convey the experience of incarceration? Be it photographs, podcasts, or fiction workshops, these panelists deploy various modes of narrative strategy to bring stories of incarceration beyond prison walls.

Moderated by Shani Jamila, managing director of the Urban Justice Center

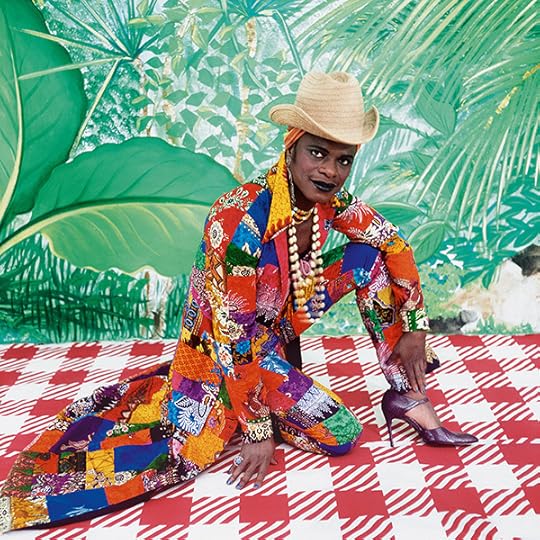

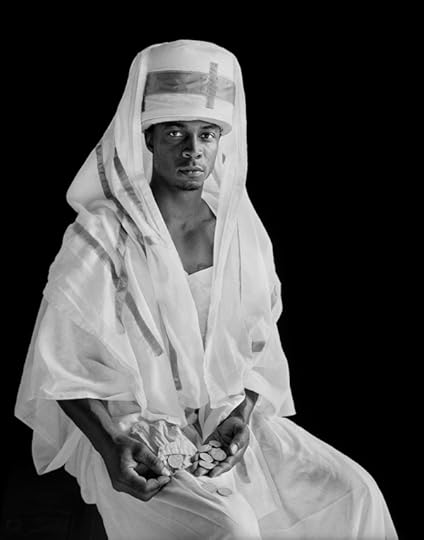

Deborah Luster, Layla “Roach” Roberts (Inquisitor), fromthe series Passion Play, 2012–13

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Seeing Angola

Wednesday, February 14, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Panelists: Deborah Luster, Zachary Lazar, Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick

Louisiana’s State Penitentiary, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, is also known as “Angola,” as it sits on the site of a former plantation with a slave population originating from Angola, Africa. This panel convenes three photographers and one writer who have made work about the notorious prison in a state that has the highest rate of incarceration of any place in the world.

Moderated by Makeda Best, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Harvard Art Museums

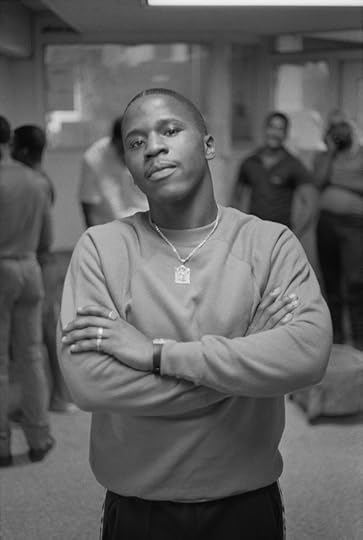

Jamel Shabazz, A detainee from Brooklyn poses in the corridor of his housing area, Rikers Island, 1986

Courtesy the artist

Inside Rikers Island

Wednesday, February 21, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Panelists: Jamel Shabazz, Lorenzo Steele Jr., Katherine Cheairs

A movement to close New York’s Rikers Island jail facility is gaining momentum. This panel brings together two former corrections officers/photographers who worked at the facility in the 1980s and ’90s, as well as a documentary filmmaker who taught filmmaking to incarcerated women at Rikers, to discuss their work around the facility and criminal justice reform.

Moderated by Brandon J. Holmes, NYC Campaign Coordinator at JustLeadershipUSA

Joseph Rodriguez, At Walden House FOTEP (Female Offender Treatment Employment Program),

a young mother holds her son. El Monte, California, 2008

© the artist

Art & Incarceration

Wednesday, February 28, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Panelists: Lisette Oblitas-Cruz, Aliya Hana Hussain, Jesse Krimes, Joseph Rodriguez

How does incarceration impact art making for incarcerated artists and non-incarcerated artists concerned with the criminal justice system? This panel brings together a range of artists and figures who facilitate art projects with incarcerated individuals.

Moderated by Nicole R. Fleetwood, contributing editor of Aperture’s “Prison Nation” issue

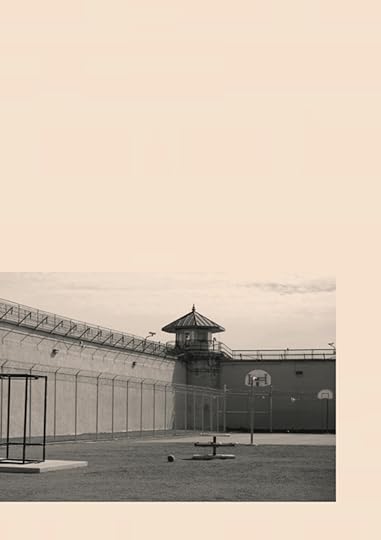

Stephen Tourlentes, Wyoming State Death House Prison, Rawlins, Wyoming, 2000

Courtesy the artist and Carroll and Sons, Boston

Architecture of Confinement

Wednesday, March 7, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Panelists: Bruce Jackson, Stephen Tourlentes, and Laurie Jo Reynolds.

This panel considers incarceration from an architectural perspective and how photographers engage with prisons as omnipresent structures in the American landscape. Moderated by educator and activist, Shana Agid.

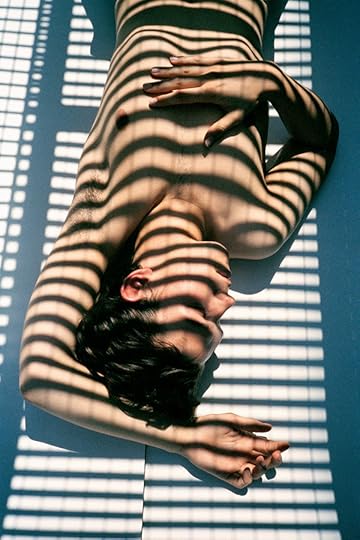

Sable Elyse Smith, from the book Landscapes & Playgrounds (San Francisco: Sming Sming Books, 2017)

© and courtesy the artist

Artist Talk: Sable Elyse Smith

Tuesday, March 27, 2018 at 7:00 p.m.

Aperture Foundation Gallery, New York

Known for her work across photography, video, poetry, and performance, Sable Elyse Smith is interested in the personal consequences of mass incarceration in the United States. Her recent artist’s book Landscapes & Playgrounds (2017), featured in Aperture’s “Prison Nation” issue, is a meditation on the relationship between an incarcerated father and a daughter, and a form of communication that is embedded in surveillance. Smith’s work has been presented most recently in Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon at the New Museum and in the solo exhibition Ordinary Violence at the Queens Museum in New York. She is a 2018 artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Aperture magazine’s “Prison Nation” issue and the related exhibition and programs are funded, in part, with generous lead support from the Ford Foundation, as well as funding from the Reba Judith Sandler Foundation. Additional funding is provided by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Grace Jones Richardson Trust, and the Board of Trustees and Members of Aperture Foundation. Additional public funds are from the National Endowment for the Arts, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

The post How Can Images Tell the Story of Mass Incarceration in the US? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 9, 2018

Beauty in the Eye of the Storm

Inside the ACLU, two trans artists stage a secret photo shoot—and question the attitudes of liberal institutions.

By Jenna Wortham

Amos Mac and Juliana Huxtable, Liberty, 2013

Courtesy the artists

“Creepy, exciting, and a little weird” is how Amos Mac, a Los Angeles photographer, describes slinking into the American Civil Liberties Union offices in Manhattan late one night in 2013 to shoot the artist and musician Juliana Huxtable, who worked there at the time. Over the course of several evenings, the two snuck in suitcases of clothing, light kits, and equipment.

As an artist and a creative, Mac centers on reclaiming trans bodies in his work. In 2009, he founded Original Plumbing, a quarterly magazine focusing on the experience of trans male culture. “I started documenting other trans artists because I was tired of seeing disembodied body parts and scars hanging on the walls in museums and galleries and feeling like shit when I saw it,” Mac said. “There’s more to this, to us. These people are human beings. We are human beings.”

Amos Mac and Juliana Huxtable, Rest, 2013

Courtesy the artists

Mac and Huxtable first crossed paths in 2011, at a house party in Bushwick. They soon met up for coffee and, shortly after, collaborated on several photographs of Huxtable in her home, as part of Mac’s ongoing Bedroom Series, which began in 2011 and features queer artists and writers in their personal spaces. Two years later, they agreed to work together on another series. During a brainstorming session, Huxtable told Mac about some of the disturbing, traumatic, racist, and transphobic attitudes she encountered at her job at the ACLU, where she worked as a legal assistant with the racial justice program.

Mac was shocked by her story but not surprised. “These organizations are large and they don’t always encompass the issues they’re fighting for,” he said. Huxtable also revealed that she planned to quit soon, and the two seized on the idea of reclaiming the space that oppressed her during the daylight hours. As she stated in a 2013 interview with Mac about their collaboration, most of Huxtable’s challenges came from adjusting to the corporate, nine-to-five routine, and she “felt restricted by the gap between the politics of people who, despite their best and most liberal intentions, saw me as a problem.”

Amos Mac and Juliana Huxtable, Table, 2013

Courtesy the artists

The ACLU, like other U.S. institutions, is facing criticism and scrutiny on a national scale for defending the right of white supremacists to march in Trump’s America, forcing many to reexamine the infrastructure that governs our country, as well as raising questions about who they are serving and at what cost. This awakening has come slower to others—while some, like Huxtable, have spent their lives calling for this inevitable revolution of thought and policy.

The photographs from those nighttime shoots show Huxtable in repose around the ACLU offices: in the bathroom, atop mail room shelves, near an enormous poster of the Statue of Liberty. Her regal face is quiet, contemplative. Her beauty rests at the eye of the storm. The nondescript corporate background disappears behind her—the eye cannot focus on anything but her. She looks poised, undefeated. Ready for action.

Jenna Wortham is a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine and cohost of the podcast Still Processing.

Read more from Aperture Issue 229, “Future Gender,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Beauty in the Eye of the Storm appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 5, 2018

The Offset Artist

From Dayanita Singh, a portable museum in book form.

By Lesley A. Martin

In July of last year, before the Museum Bhavan had been shortlisted for the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, and well in advance of the book having been selected as the winning PhotoBook of the Year, I was delighted to catch Dayanita Singh in Tokyo on the occasion of her exhibition Museum Bhavan, curated by Michiko Kasahara, on view at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (May 20 through July 17, 2017). In the weeks and months since, Singh has taken to the road with two bespoke suitcases full of multipatterned Museum Bhavan book sets, the evolution of her earlier Suitcase Museum—a luggage set designed to function as both delivery system and display case, an enactment of her idea that the museums of the future should be “small and portable.” In fact, the museum of the future might just be a set of books, open and installed for all who visit your dining room table. Like an itinerant salesperson, she has had a jacket specially tailored and outfitted with nine pockets, one for every leporello volume enclosed within each set. Singh is quite serious about getting her work—which she defines, in large part, as her offset-printed images—into the world and into your hands, not just onto the traditional white-box space of the gallery wall.

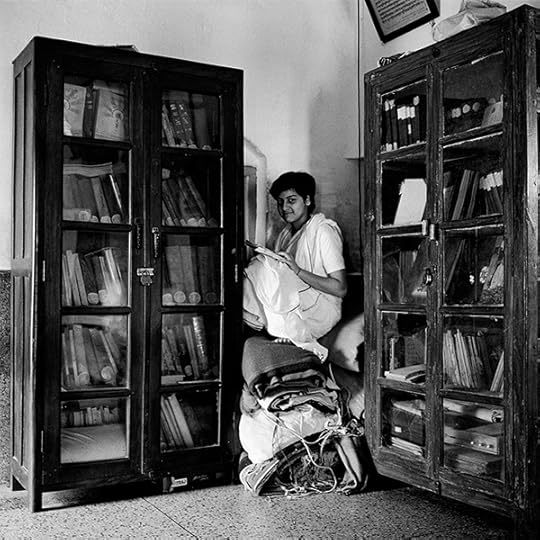

Dayanita Singh, from “Little Ladies Museum,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

Lesley A. Martin: In terms of artists who embrace the book as an essential part of their practice, you have really taken this to heart as central to your work. I love the “snout-to-tail” approach that you bring—you find a use for everything, every part of the book: the pages, the outside and cover of the book, the architecture of the book. You really engage with it as a form.

Dayanita Singh: I can no longer separate the images from the paper, the structure, the exhibition that it will become, and then the book becomes the exhibition, and the catalogue of that exhibition. I want the book to be an object, and a very desirable object. When you buy a book, I want it to be the same as if you acquire a sculpture. Of course, it’s a book, and I would never want to dislodge the bookness of it. But I want it to be more. I think I managed to do that with Museum Bhavan (Steidl, 2017). Inside they are all the same book(s), but each of the three thousand copies is enclosed in a box bound with a different type of cloth. The cloth used is called achaada, the under-cloth used in block printing. The residue of the ink collects in different places in different ways, and they usually throw that away once it becomes all coated with ink. Some of the boxes still have drops of paint, which you can peel off. So, I made this very desirable object, it’s mass-produced, and yet it’s unique. Now my question to you: What do you call it? Is it a book? Is it a museum? Is it an exhibition? A multiple, or a unique object?

Dayanita Singh, from “Godrej Museum,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

LAM: I like your use of the term “book object” as a description for what you produce.

DS: Yes, I always wanted the mass-produced book to be unique. People like to make a distinction between artists’ books and mass-produced books. I say I make mass-produced artist books. Wealthier collectors will come and say, “Well, Dayanita, I’m not going to buy your little offset book object. I’m going to buy a print.” And I say, “I’m really sorry, but there are no prints. This is it.”

LAM: Ed Ruscha always said that he wanted to make mass-produced books for mass distribution. He wasn’t interested in the handmade, one-of-a-kind book. You’ve found a way to do both. Each of the individual seven offset-printed volumes within your previous book, Sent a Letter (Steidl, 2007), and the nine in Museum Bhavan are packaged together inside a box. Each volume can be viewed by turning the pages in the traditional manner, or displayed individually as a mini-exhibition, either in a gallery or in one’s own home, as you discuss with Aveek Sen in “Conversation Chambers.” You also call the Museum Bhavan a “pocket museum.”

DS: Yes. I even have a jacket that holds nine museums in its pockets, to wear at my openings. But it is such a privilege to be in people’s homes. It falls in line with other traditional forms of disseminating the photograph—like giving people family portraits that still hang in their homes. First Sent a Letter, and now Museum Bhavan will exist in personal archives of their homes. And it is an invitation to you, the reader, to become the curator of my work if you like. Whenever I attended an exhibition of my work, I always felt bad that the book wasn’t there, you know? I want the viewer to know that there’s a sequence to this work. I’m not making single images. The organizers always said, “Dayanita, a book is a book, and an exhibition is an exhibition.” That stayed in my head. I asked myself, “So, what is it going to take for my book to be in the exhibition?” The answer is that it has to be in a format in which it can be exhibited. Hence the idea of the Museum Bhavan and the book objects, the suitcase museum, and the book cases.

Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan, 2017. Installation at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Courtesy the artist

LAM: At the Venice Biennale in 2013, your part of the installation at the German Pavillion consisted entirely of a line of framed books; then you launched the book in a little pop-up shop along some side alley, like a Venetian book vendor. In the exhibited set of framed books, are they offset images or did you tip gelatin-silver prints onto the book case?

DS: They’re all offset. I love offset. I prefer to call myself an offset artist because “book artist” and “artist book” is getting confused within the photobook world.

LAM: Tell me a little bit about Spontaneous Books and the Kochi Box (2017).

DS: I am Spontaneous Books. I made the Kochi Box on my own. Inside the wooden frame are thirty image cards, printed offset in India. It was only available at the Malabar House Hotel during the Kochi Biennale. There was no publicity. It was about finding it by chance, and realizing then that you could acquire it. Once you acquire it, you can become the curator of my works, deciding willy-nilly which image you wanted to display. The viewer becomes part of my process. Depending on what order you place them in, it’s a different book.

LAM: This is another way to combine or confuse—very productively—the idea of exhibition and book. One thing that has struck me is the incredibly coherent and consistent approach to all of the sculptural objects you make—frames, box structures, desks, installation pieces—they all feel of a piece. Your ability to do so is integral, ensuring that these efforts never feel random or chaotic. All of your objects feel quite modular, as though they will and can fit together in the end.

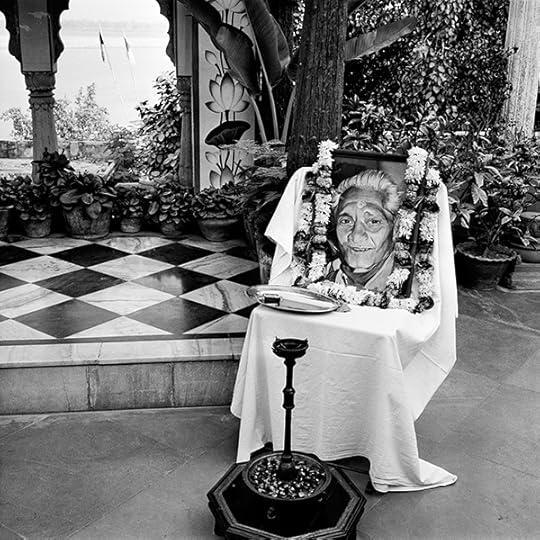

Dayanita Singh, from “Museum of Men,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

DS: I would love it to be a little chaotic, but I’m just incapable of it.

LAM: There’s a little chaos in the Kochi Box, don’t you think?

DS: Absolutely. But it’s controlled disorder.

LAM: Isn’t that what bookmaking is to some degree?

DS: I think it’s trying to make order, but not too much order. Leave it to the reader to work out the relationships, and leave room to bring their conversations into the work.

LAM: On the other hand, the idea of the book object as the combination of the book space and the exhibition space, as you describe it, also seems a way to preserve your directed view through the work—a way to ensure that the edit and the sequence remain intact. Tell me about how you approach the editing process. Do you think it can be learned, to know how to edit properly?

DS: I wish I could teach that, because that is what I find is missing from a lot of the photobooks that I see. Photographs are just the raw material. The key is editing. And with the editing, a sequence builds up. That’s the stage at which the material starts to demand how it wants to be gathered. What form will it take? You have to be prepared for it, because it could be, and I suspect this is going to happen with the next book I want to make, that it demands to be a projection and not a book at all. That it demands to be a box of cards, for example. For me, editing has just as much to do with other questions: What’s the smell of this book going to be? What will the sound of the paper be? The feel of the cloth on the cover? What’s going to stay with you?

Dayanita Singh, from “Little Ladies Museum,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

LAM: So it’s the edit and sequence working in combination with the physical experience?

DS: Yes, the tactile, sensual experience of the book. When I start, I don’t know how that book will be, what size, shape, or feel it’ll have, but I trust the editing process. All I need is about three weeks of being able to shut everything out to get to zero, where I can start the process. A piece of music helps me a lot. Depending on the music, or whom I’ve been in conversation with, or not, or what book I’m reading—all of this sets up a tune in my head for the editing.

LAM: In your writing, you’ve used music as a metaphor for editing.

DS: Yes. I’ve traveled so much with classical musicians that for me the idea of a raag is very present. In a raag you have an alap, or an introductory section, an inventory of the notes you have to work with. Following that, you’re elaborating on those notes and setting up the larger raag from them. Then there’s what is called the silent note, the khaali, which in photobook language we would call the empty page, which is crucial. I edit with my ears and not strictly with my eyes. I’m looking at the image, but I also want to be able to hear it, and to understand the resonance that the image leaves with me.

Dayanita Singh, from “Museum of Photography,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

LAM: You mean where is the crescendo to a sequence and where does one need to pause? I find that people tend to clump things together in their editing instead of weaving them through—the arc of a narrative needs to be complicated and textured.

DS: Exactly. I don’t expect anyone to immediately say, “Ah, got it.” That would be a tremendous failure on my part. I feel like many mistakes made in editing books are often a holdover from photojournalism, from thinking about pictures in magazines. Magazine sequencing is one thing, and you can’t apply that to a book, or God forbid, to an exhibition. Of course, it’s the same boys who did the big magazine photo-essays who shaped the photo discourse. And I think unfortunately the photobook, too, has become somewhat of a boys’ club. When you talk to artists who work with photography, it’s such a relief, because they don’t have any of that baggage.

LAM: Perhaps they feel less of a feeling of obligation to who, what, where, when, why. You’ve said that “we need to get past the established forms of analogue photography as our language.” Is that what you’re talking about here? That the modes of storytelling or the established forms of editing and assembling images have become overly structured and didactic?

DS: Yes. It has to be more organic. The form has to be much more organic, fluid, and allow for waxing and waning. And it has to have a resonance. It doesn’t matter how beautiful your image is if there’s no resonance.

LAM: Resonance implies that something is bouncing off another object, another person, another ear, another set of eyes. There is an implied reader or recipient.

DS: If you’re putting work out into the world, then have some respect for the person who is going to see it, and their intelligence.

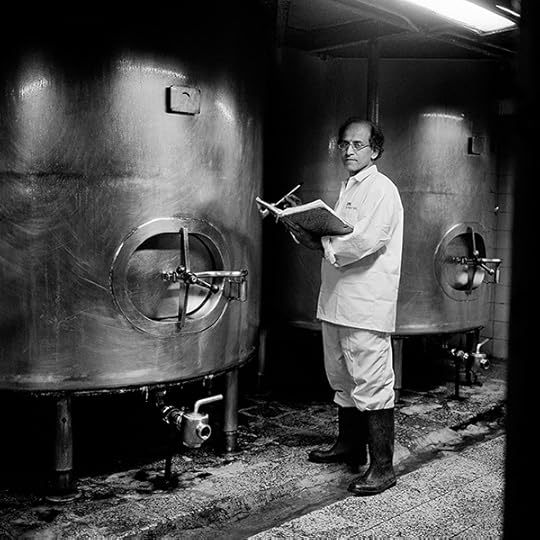

Dayanita Singh, from “Museum of Machines,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

LAM: Do you think about the audience when you are making your books and your edit?

DS: I never have an audience in mind, but there’s always an addressee. Naoya Hatakeyama wrote a great piece about my work called, “Who is that Someone, the addressee?” that you can find on my blog. He asks a crucial question: who are we photographing for, and who is the addressee of the work? Often, my writer friends have been the addressees, because I’ve gone with them to all these incredible places. They’ve opened all these doors (in my mind), and then I want to respond to them, so I’ll make a book for them by cutting up my medium-format contact sheets and pasting them into accordion-fold Moleskines. That was the start of Sent a Letter, actually. For all my work, there is one or maybe two addressees, never more.

LAM: You seem to use written language frequently in your installations, but you generally don’t rely heavily on texts or language in your books.

DS: I have that very romantic idea that a photograph can really go where there are no words. If you could explain an image to yourself in words, you wouldn’t need the image. But if it leaves you with something, whether it’s annoying or pleasant or whatever, that cannot be put into words, it has resonance with you. And that’s the magic of photography.

LAM: One of the metaphors that people use with your work is literature, as if it were something along the lines of a photo novel or visual literature.

DS: House of Love (Radius, 2011) is a book that I called photo fiction, in which I tried to create a set of short stories. (I think all bookstores should have a section called photo fiction.) It’s slightly tongue-in-cheek when I say, I’ll make a photo novel, or, Can a photograph be poetry. But it’s intended to tease people a bit, to get them to understand that a photograph or photobook can actually do something quite distinct from other forms.

Dayanita Singh, from “Museum of Vitrines,” in the book Museum Bhavan (Steidl 2017)

Courtesy the artist

LAM: The idea of a distinct visual literacy of the photograph is so important.

DS: And so much of that visual literacy has to do with the sequence, no? What happens when you break up the sequence? Museum of Chance, as a book, has eighty-eight covers. It’s a book and it’s bound to a sequence. But when I frame the covers and reinstall it, I break the sequence. There are endless possibilities. I wrote about this recently in my short story on an Instagram post of a photographer who becomes a photograph. I’ll probably disappear into one of those little—

LAM: [laughs] Into the folds.

DS: Yes! I’m going to become that little creature who gets lost in her own book.

LAM: The idea that you are consciously creating this new space, I hope, will provide a way for other artists to think a little more about how to engage with these ideas.

DS: Absolutely, because we can’t rely on galleries and museums. You can’t say that I can only be an artist if I’m shown in a gallery. We need to think about dissemination. This is the one thing that I really imbibed from photojournalism: the importance of the dissemination of the image. And if I can’t do anything else, if no one wanted to show or publish my work, I could project my images from this hotel room onto those clouds and put my work out there. There is always a way, once you step out of the box that photography often can be.

Dayanita Singh’s work and writings can be found at dayanitasingh.net.

The post The Offset Artist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 3, 2018

Walker Evans, Hero of the Vernacular Style

A landmark exhibition argues that the photographer’s approach to image making goes far beyond documentary.

By Sarah M. Miller

Walker Evans, Resort Photographer at Work, 1941

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Last fall, shortly after the opening of Walker Evans at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, curator Clément Cheroux and I sat down for a conversation about the massive retrospective, which he originally organized for the Centre Pompidou. We spoke about the organizing thematics of “vernacular as subject” and “vernacular as method,” Evans as a proto-conceptualist, and the risks of including objects from Evans’s own collection of weird and grisly photographs.

Sarah M. Miller: Framing Evans’s work through the vernacular allowed you to sidestep the thorny question of what documentary is, and what our expectations of it are, while also presenting to American audiences a less familiar history of documentary: the avant-garde’s. Could you expound on that framework? How did you choose it?

Clément Chéroux: The challenge was to show the work of Walker Evans, including his iconic photographs, but also to build something new in the approach. Especially in Europe, Evans is mostly known as a documentary photographer. I’ve been thinking about this question of the documentary style, and the question of the vernacular.

The two larger categories we have in photography are art and non-art. On one side, you have the art photographer, and on the other side, the vernacular. Everything that is not art is vernacular photography: documents, snapshots, architecture photographs, postcards, photographs of tools for catalogs, et cetera. Evans used the term “documentary style.” Documentary photography is only part of a larger category known as the vernacular. This is the reason why I proposed the concept of a “vernacular style.”

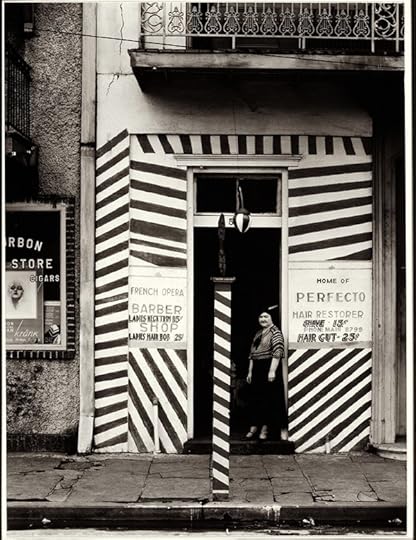

Walker Evans, Sidewalk and Shopfront, New Orleans, 1935

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: What you’re saying is that you don’t accept this common division that puts documentary in opposition to art. It makes more sense to put vernacular in opposition to art, and to see documentary as that which bridges or deliberately brings the vernacular into art?

Chéroux: No, for me, documentary is part of the vernacular. In twentieth-century photography, the line is between what is art and what is not art. What is not art is the vernacular, which includes documentary photography, amateur photography, scientific photography, everything. For me, documentary photography is a small part of vernacular photography.

Miller: So, style is the bridge. As someone who also works on the history of documentary photography, I always stress that artists associated with “documentary style” chose the form or the look of information, rather than the function of actually transmitting information, and deployed those forms in order to change what kind of art photography could be. The aesthetic of information allowed artists to play with the deadpan, and to reject the overtly expressive. I saw that argument played out in the show, which I loved.

Chéroux: The fact that Evans was recognized as a photographer using the documentary style is a historical phenomenon. When Evans became more recognized in the 1980s and ’90s, especially in Europe, he became the hero of the documentary style. Most of the photographers were working in this style—the whole Düsseldorf school, the Bechers, Ruff, Gursky. Contemporary photographers need predecessors.

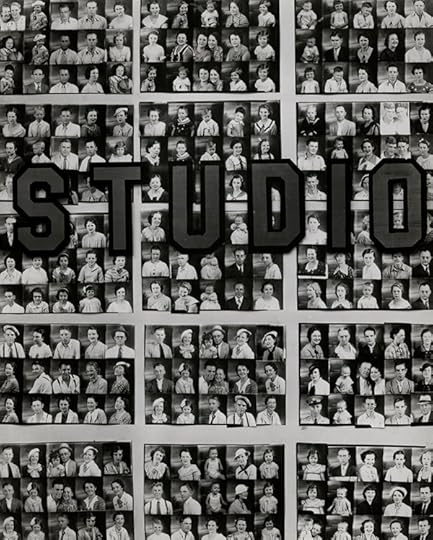

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: How did you divide the ideas of “vernacular as subject” and “vernacular as method” to structure the two parts of the exhibition?

Chéroux: Almost everybody who has written about Evans says he was trying to define the essence of American culture through the vernacular. But the word “vernacular” is never very well defined.

Miller: You give it a historically and linguistically specific definition in your catalogue essay.

Chéroux: The etymology was useful to understand the definition of vernacular: it brings us back to the Roman Empire where the Latin word for slave was verna, so the vernacular is something that is useful. Vernaculus means a slave that is born in the house, so vernacular means something that is domestic. Along with the domestic comes the idea of the local, and throughout history the meaning of the local has extended to the village, to the town, to the region, and to the whole country. According to the Roman civil code, the slave is at the bottom of the hierarchy. So, the vernacular is always something that is low.

Walker Evans, Main Street, Saratoga Springs, New York, 1931

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: It’s easy to see how the utilitarian and culturally low are manifest in Evans’s subjects. But how does this understanding of the vernacular translate to method?

Chéroux: The first part of the exhibition is about what is in front of the lens, and the second is about what is behind the lens. The second part is really about the method with which Evans chose to photograph the vernacular. I realized that Evans, when he was choosing a subject, approached it by mimicking a style of photography, which was that of an applied photographer. For example, when he was taking photographs of the small-town Main Street, he was choosing the vantage point and the cropping of a postcard photographer. When he was taking shots of doorways or wooden churches, he photographed them as if he were an architecture photographer or a survey photographer. Some series he made are related to studio portrait photography; others are related to architectural photography, postcard photography, snapshot photography, et cetera.

What’s the best way to photograph a tool? Stieglitz would photograph it one way, Man Ray another way. Evans decides to do it as if he were a catalogue photographer: no shadows, no angles, no distortions, very straight. Every time Evans was interested in a subject, he would choose a way to depict it that was related to a certain kind of vernacular photography. The vernacular as a subject, plus vernacular as a method, combine to make the vernacular as a style. That’s really the idea I would like to demonstrate through this exhibition.

What’s the reason why Evans chooses not to play the artist? Stieglitz, for example, was really playing the artist. Evans was hiding himself as an artist by mimicking vernacular photography. And that’s quite difficult to explain to the public. He is an artist, but an artist who is not playing the artist; and on the contrary, he is playing the non-artist. This is the reason why I think that Evans is a conceptual photographer. The vernacular as a subject explains why Evans is perceived as a precursor of Pop Art. Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Lichtenstein also chose the vernacular as a subject. But if you think about the vernacular as a method, it explains why Evans was perceived by many photographers of the 1970s—“artists using photography” like Dan Graham—as a kind of precursor.

Walker Evans, Chain-Nose Pliers, 1955

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: Part of what’s so difficult about Evans is that he comes with a controlling mythology. It’s all about impersonality and removing the artist from the picture. But critics recognized as early as the ’30s that Evans was creating another form of auteurism. Many of the reviews of American Photographs (1938) noted that he could appropriate any subject at all into “an Evans.” In the ’70s, that idea was taken to extremes and used against him by critics, namely Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula. But will it ever be possible to address that idea in a museum context? Will it ever be possible to mount an exhibition that doesn’t proceed from Evans’s self-definition as an artist, his posture of self-suppression?

Chéroux: Maybe a way to answer your question is by raising the issue of the political in Evans work. When I started working on this Evans retrospective, I was almost sure I would find some connection with the Left. Evans was friends with a lot of people who were leftist, people like artist Ben Shahn. But after reading letters and texts, and going through his photographs, I quickly understood that Evans was not interested in politics. The fact that he was interested in the sharecroppers, the fact that he was photographing the effects of consumerism, the effects of industrialization, all of these things, was not a political approach. That was an aesthetic approach. It’s a Baudelairean approach.

Miller: I’ve always thought of Evans as an astute cultural critic, but one who would refuse to call himself a political critic. His cultural criticism comes from a political viewpoint, to be sure. But there is no political agenda, only a political viewpoint.

Chéroux: Yes, that’s it. In French we say “la politique” and “le politique.” So, the first one is being engaged in politics, and the second one, just by changing the pronoun, is being concerned, but not part of the movement.

Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938–41

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: When you played out the argument about vernacular as method through the exhibition, did you have any worry that it could flatten the distinctions between different kinds of assignments—for example, Evans’s work for the Museum of Modern Art on African masks, or for Fortune—versus a highly individual project like the subway photographs?

Chéroux: The only one that I would really consider as a commission is the African masks. All of the projects for Fortune were his own ideas. I mean, there was no editor saying to him, “Please make a project about tools,” or “Please make a project about taking photographs from the train.” He was choosing the subject, he was taking the photographs, but then also cropping the photographs, doing the layout, and writing the text. We should not consider the projects for Fortune as commissioned. It’s totally different from what Cartier-Bresson was doing for the press. When Cartier-Bresson was sent on assignment, he was taking the photographs and then sending everything to his agency. He was not editing. Evans was really in control of everything.

Miller: So for you, it’s a way to demonstrate not only that he’s a conceptual photographer, but also that there’s a conceptual continuity to projects that otherwise might look like very different parts of his career and different frameworks for making and distributing.

Chéroux: Yes, the magazine projects were another way to make art. He was doing that since the ’40s. Again it makes him a precursor to conceptual artists of the ’60s and ’70s, people like Dan Graham, or other artists who were treating the magazine as the best way to disseminate their ideas. So, for me, if it’s not commissioned, it’s a piece of art in itself. That is why I wanted to have the magazines on the wall, and not in the middle of the room in a vitrine.

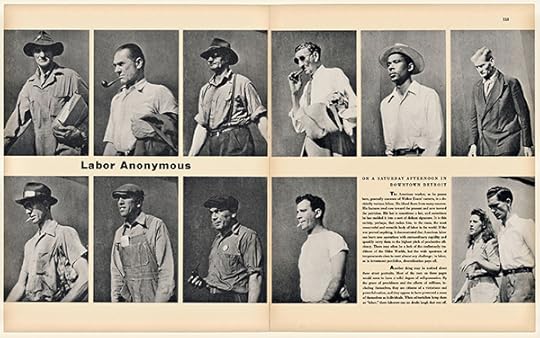

Walker Evans, “Labor Anonymous,” Fortune 34, no. 5, November 1946

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: You’re emphasizing that the magazine really is the art; it’s Evans’s chosen presentation of the art.

Chéroux: If you think about the ’40s through ’60s, he was doing more projects for Fortune than exhibitions. In a way, it was more important to show the magazines than to show American Photographs. There were a lot of strong choices in planning this exhibition. American Photographs is a great book, but the magazine work is as important. American Photographs is for me a kind of Bible of the vernacular. But I really didn’t want to reduce the whole exhibition through the book.

Miller: In the first week of the show, I raised concerns about the inclusion of a lynching photograph in the exhibition. I would have been alarmed no matter what, but I suppose I was on heightened alert because I was preparing to bring my students. Were you surprised that it could elicit such a strong reaction?

Chéroux: Yes, that was a bit of a surprise for me, and that’s a cultural difference between the United States and France, where the exhibition originated and was presented for the first time. You know, I’ve only been here nine months, and I’m learning every day about these questions. The newspaper photograph that you mentioned is among the press material that Evans clipped from papers and kept in a scrapbook titled Pictures of the Time: 1925–1935. He collected these images as a young man, when he was developing his visual style and sourcing thousands of references including fine art images, news images, vernacular and applied photography, postcards, street photography, and graphic design. We don’t know exactly why he kept these images, he never expressed himself about that, but we believe that they are an important part of Evans’s artistic process. We have included a label alerting visitors that there is challenging content in one gallery. For me, the question is why he was so interested by disturbing graphic images—not only that one, but also the electric chair, the people who were assassinated in Cuba.

Walker Evans, Street Debris, New York City, 1968

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Miller: I understood that context. I had already talked with my students about how the interest in the document of the ’20s was, in some cases, as Pierre Mac Orlan said, the notion that a photographic knowledge of the world is cruel. Evans was fascinated by the weird and barbaric insight that photography inadvertently provided into modern life, and collected images that his generation would have called documents for that reason. But it’s a hard line to walk here, where the work of racial terrorism those lynching photographs were manufactured to carry out can feel very alive. Especially in a season where we’re debating Civil War memorials and people are voicing the right not to be attacked by acts of white supremacism in public—no matter what historical context they were erected in or published in.

Chéroux: I perfectly understand this sensitivity, but for me, the problem would be to hide this photograph because of it. Or to hide the fact that Evans was collecting these photographs, or to hide the fact that he was photographing Confederate monuments. Throughout my career, I’ve been dealing with these questions. I’ve published a book on the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. I curated an exhibition and published a book on photography and the Holocaust. I’ve always chosen to show the photograph with, of course, an explanation or with some attention to the way it was displayed in a museum.

In this case it’s a bit different, because that’s not really the subject: this room is not about lynching, it’s about Evans’s own collection. I always take the position that the image is a good way to talk about these questions, and that we should use the image to debate these subjects. The worst thing for me is to hide the images, and the questions that the images raise.

Sarah M. Miller is an independent scholar, teacher, and critic based in Oakland, California.

Walker Evans is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through February 4, 2018.

The post Walker Evans, Hero of the Vernacular Style appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 18, 2017

Gender Is a Playground

From Aperture’s “Future Gender” issue, Zackary Drucker and Kate Bornstein discuss pioneers, politics, and the next frontier in gender expression.

Zackary Drucker and Kate Bornstein, Brooklyn, 2017

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger for Aperture

Kate Bornstein is a gender outlaw. Decades before Caitlyn Jenner graced the cover of Vanity Fair, Bornstein was pushing for a radical vision of gender beyond the binary. In 1989, with daytime talk shows among the only mainstream arenas to address nonnormative identities, she appeared on Geraldo in a segment titled “Transsexual Regrets: Who’s Sorry Now?” The show was meant to sensationalize Bornstein, a transgender lesbian, but she wasn’t having it. “I was the one who wasn’t sorry,” she later said. In her performances and plays, such as Hidden: A Gender (1989), and in her groundbreaking, genre-defying 1994 book Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us, Bornstein writes with characteristic wit, candor, and generosity about topics from gender confirmation surgery to trans activism. Throughout her life and career, Bornstein has defied the rules. For Aperture’s “Future Gender” issue, Bornstein spoke with guest editor Zackary Drucker about trans pioneers, the thrill of pornography, and the young photographers envisioning the next frontier in gender expression.

Hobbes Ginsberg, Self-Portrait, Seattle, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Zackary Drucker: I wanted to start by telling the story of how I found my way to you and your writing as a fourteen-year-old queer youth. It was the mid-’90s and I’d recently discovered the word queer. There I was, in the LGBT and women’s studies section at the bookstore. I don’t know what possessed me, but I shoplifted a copy of Gender Outlaw, and discovered the word transgender, and found myself in your words and in your experience in a way that I had never felt reflected before. It was a Bible of sorts. It was a Talmud, rather. I still have this copy of Gender Outlaw, and it’s creased and worn, and has notes in it—my little fourteen-year-old self, writing notes in the margins. It has a rainbow sticker on the front [laughs]. You were such a gender pioneer for me personally, and for countless others—I think an entire nation, really. Who are your gender pioneers, and who were they when you were transitioning in the 1980s?

Kate Bornstein: First off, allow me to say that when we first met, you stole my heart, and it’s lovely to hear that you also stole my fucking book. I’m so proud of that!

Drucker: I’ll pay you back for it.

Bornstein: It’s a gift now. Oh! I cherish that story.

My pioneers. Well, there weren’t many. There were, of course, the mainstream big hitters: There was Christine Jorgensen. There was Renée Richards. But I didn’t identify really with any of those. There was Wendy Carlos. She was the first trans person to graduate from Brown University. I was the second—that we know of. But honestly, my real hero, who I wanted to grow up and be like, was Tula.

Photographer unknown, Modeling shot of Tula, ca. 1970s–’80s

Courtesy Caroline Cossey

Drucker: Caroline Cossey.

Bornstein: Yes. But she was Tula, and that’s all she was known as, and she wrote the book I am a Woman (1982). What got me was her liminal beauty. She was a beautiful boy and a beautiful girl all at the same time—and I wanted to be pretty! She was the first trans woman I saw who embraced beauty. She went right into being “girl.” But she lived “boy.” That sang to me. She was my earliest hero.

Much later, Lou Sullivan was a hero of mine. We lived near each other in the Mission District in San Francisco in the late ’80s and early ’90s before he died. He was a complete maverick. I was one of the earliest trans women who came out as lesbian. He may have been the first trans man who came out openly as a gay man. So, we spoke about the entanglement of sexuality and gender. I have lots of heroes today, and you’re one of them.

Mariette Pathy Allen, Lou Sullivan, at home, San Francisco, 1990

© the artist

Drucker: Oh, my goodness.

Bornstein: You are.

Drucker: You’re making me blush now. I have so many questions. First, I was thinking about your relationship to postmodernism, and how hard it must have been to conceptualize this binary—that of Christine Jorgensen and the writer Jan Morris, and the antiquated narrative of being a woman trapped in a man’s body. It must have been reductive to you because you were so much more interested in complicating meaning and adding layers. That’s why you’re my gender pioneer, because you were presenting a way of being that was not a simple, reduced, “I am one way, but I should have been the other.” That feels like a very black-and-white way of thinking.

When I found your book, you were way ahead of the curve of where we are today, with people acknowledging that gender is a spectrum like everything else. How did the conditions of the 1980s and your understanding of postmodernism influence your sense of self, or was it completely self-made?

Bornstein: I didn’t know about postmodernism until I got invited to an academic women’s theater conference in 1987. These were not women who were making theater; these were women who were critiquing theater. They invited me to come perform, and told me that what I was doing, performing three genders, was postmodern. Postmodernism runs so against the grain of either/or, which is the basis of America; but that basis proved to be a veneer for a deeper truth that everything—including gender—is relative to context and point of view. And in the 1980s and early ’90s, that made the most sense to me. The word binary didn’t exist in relation to gender. Or, if it did, I didn’t know it. We called it “the two-gender system.” Actually, in the first edition of Gender Outlaw I called it “the bipolar gender system.”

Drucker: That’s so accurate.

Bornstein: Postmodern theory gave me the permission to define myself as “not man, not woman.” We didn’t have words for what we were, but we could definitely state what we were not. The Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis said that way before I did. “I am not a man and I am not a woman.” Many of the queens of the day, in the late ’60s and through the ’70s, were actually embracing and living nonbinary lives.

There’s intense polarization on many levels within the trans community these days—one of them is between drag queens and transgender women, who claim that drag queens hold on to male privilege. But, my guess is that none of these transgender women has met a drag queen out of drag. For the most part, they are highly effeminate men, sometimes just flaming fags. They have no privilege out in the world. And they are wonderfully nonbinary. Drag is a “queer” identity. Female impersonation is a “straight” identity. So, female impersonation is what transgender women might be objecting to. Out of their female clothes, those men retain male privilege.

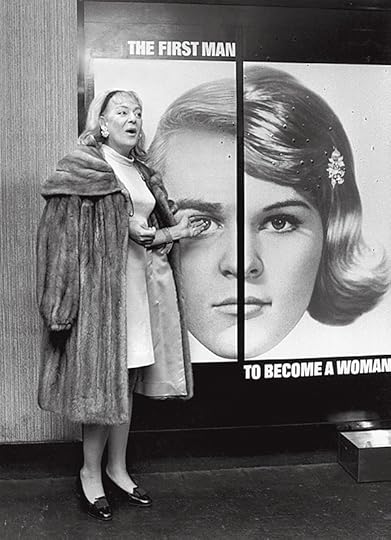

Photographer unknown, Former soldier Christine Jorgensen at a press reception in London to launch the film The Christine Jorgensen Story, September 14, 1970

© Wesley/Getty Images

Drucker: I couldn’t agree with you more. Female impersonation has been used as a tool of misogyny, especially in television and film, and has too often been conflated with trans identity. I think much of the time homophobia is really rooted in a discomfort with gender, with gender roles, and with people performing outside of their gender roles. It’s not about two masculine men holding hands walking down the street—though, of course, that can be cause for violence, too. I think it’s actually swishy queens and butch women that bear the brunt of what we call homophobia, which we can just as easily situate in the realm of transphobia or trans misogyny.

Bornstein: Bingo.

Drucker: Moving from people to images—to film, television, and photographs—who were your pioneers in image making? What images of trans life informed your imagination or your sense of yourself? How did you arrive at a trans identity through culture at large?

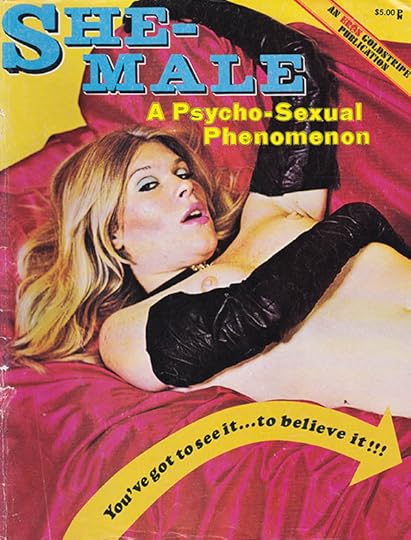

Bornstein: In the 1970s and through into the ’80s, and even today, the images of trans porn inspire me, light me on fire. I think it’s so fucking beautiful!

In April, Laverne Cox told Elle magazine that trans people are beautiful and shouldn’t have to “blend in.” I retweeted that, but I was quickly reminded that sometimes you have to pass for safety’s sake. Absolutely. That takes priority. But the beauty inherent in the blend—porn was the only place I could find it. And there were wonderful porn magazines. Chicks With Dicks. She-Male. They weren’t trying to be women. They were beautiful not-men, not-women.

Janell Shirtcliff, Laverne Cox, 2016

Courtesy Form Artists Inc.

Drucker: Yes! I’ve been collecting all the trans woman magazines that I can get my hands on. They go back to the early ’60s. It’s a rare glimpse at our history, and it provides documentation of people who are not really documented elsewhere. Our history is in those magazines, and it’s embedded into a history of sexual exploitation, and maybe in the history of sexual pleasure, too. We often forget to recognize how empowering it can feel to be photographed and to be represented. And that’s continued today. Trans pornography is a category of pornography that’s growing faster than any other category. So, it’s interesting how our relationship to pornography, as a community, is so fraught. We have existed there, and it has provided a rare economic opportunity, where we were typically shut out of other economies.

Bornstein: For decades, porn was the only place we were allowed to be sexy, where people were allowed to be attracted to trans bodies. And today, you can’t be attracted to a trans body. You have to be attracted to a woman’s body. You’re allowed to be attracted to a woman who transitioned out of being a man. You’re allowed to be attracted to a man who transitioned out of being a woman. You’re not allowed to be attracted to those of us who blend.

Cover of She-Male, 1974

Courtesy Zackary Drucker

Drucker: What do you think about the wave of visibility that trans folks have had over the past several years? How has that amplified platform helped us, and where has it hurt us?

Bornstein: In the ’60s and ’70s, when transsexuals first became known to the mainstream, we were the cultural butts of jokes. When transsexual—a binary-identified man or woman who had transitioned out of another gender—became transgender, it was a big step because transgender is now understood not to depend on biology, so that’s good. But what’s visible again is only the binary. The people who took the place of trans as the butt of the jokes are now the genderqueer folk, the gender fluid, the nonbinary, the gender nonconforming.

If you google genderqueer you will find very objectifying visibility. Whereas transgender visibility is more and more inclusive, more and more, “Oh yes, they’re just like us.” So, there are two levels of visibility going on here. But the flood of trans everywhere is specifically binary-identified trans people.

Drucker: Absolutely. To your previous point about Jackie Curtis, when Holly Woodlawn was interviewed by Gay Power newspaper in the late 1960s, they asked her, “Do you live your life as a transvestite completely?” and she said, “There is only one Holly Woodlawn. I know what I am.”

Bornstein: [applause]

Drucker: For the 1960s, that was so forward-thinking. It was kind of like, “Fuck you; there are more than two ways of being.”

How do you think this kind of pluralistic range of identities today has established new barriers and obstacles between us? The right thinks that the left is fetishistic about identity, and even the moderate left has been critical of the trans rights movement for pushing the conversation too far out of people’s comfort zones. How do we rush the gates instead of backing down, and how do we push the conversation ahead and lean into a backlash, instead of losing momentum with these sorts of increasing legislative setbacks?

Bornstein: When gender is a binary, it’s a battlefield. When you get rid of the binary, gender becomes a playground. All kinds of ways of looking at gender can peacefully coexist. Of course, there are playground bullies. But whereas the activism of any kind of binary politic is struggle, and opposition, and gaining ground at the expense of someone else, the activism of a playground is cooperation and coalition. And that’s not really being tried. Caitlyn Jenner is doing it—in the weirdest way. She is forging a coalition within the right. Good for her. I couldn’t do that. I am trying to forge a coalition within the left.

How about you? In art and photography, what do you see?

Leah James, Macy, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Drucker: I love looking to the horizon of young trans and genderqueer visualizers, like Lia Clay, Hobbes Ginsberg, Leah James, and Wynne Neilly, each of whom incorporate disparate elements of culture seamlessly, connecting fashion, performance, auto-ethnography, social media, and more. Being around long enough to identify a new wave of talent cresting is so exciting—it makes the future feel limitless. These image makers are imagining future gender in their own way, and it looks like nothing that’s come before.

Moving into the future, how do you think gender will be regulated by technology? Or do you think binaries will be more or less entrenched? Do you think there’s always going to be an “us” and a “them,” a dominant versus a subjugated? Or do you think medicine and science will veer us away from fixed states of being altogether into this sort of proverbial playground that you so gloriously illuminated? We might be the most visible generation of trans people, but medicine and science could actually reduce our visibility in the future, and yet this also speaks to the growing class divide. If it’s only people with affl uence and status who have access to procedures that reduce their visibility, will there be a sort of rebel class of gender warriors, of people who are resisting the binary?

Bornstein: Way into the future, I see the dissolution of binary thinking. This is the basis of postmodern theory. This is the basis of all Eastern philosophies. This is the basis of quantum mechanics. Relativity. Nondualism. The acknowledgment that things are unpredictable, that things are going to change. Gender is a continuum. Identity is a continuum. And that, I think, is the future, not only of gender, but of the world.

Lia Clay, Pierce, 2017, from the series What It Means to Be Trans/GNC & at the Beach in America

Courtesy the artist and Refinery29

Drucker: You just performed On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us at La MaMa in New York. How have you noticed the change in your audiences since you started performing in the ’80s? What have you learned from the younger generations in the past thirty years?

Bornstein: When I first started performing, with Hidden: A Gender and my solo shows The Opposite Sex Is Neither (1992) and Virtually Yours (1994), everything was a revelation to my audience. No one was going “Me, too.” Or, if they were going “Me, too,” they were really quiet about it. What is still new about what I’m performing is the notion of “not man, not woman.” That still knocks some people over. But now, there are more and more audience members who go, “Yeah, yeah.” When I see your generation embracing the possibility of a third, embracing the notion of fluidity, it gives me hope for the world I’m going to be reborn into.

Drucker: You’re an incredible visionary and a futurist. What do you think are the most significant changes you’ve witnessed in your lifetime, and where do you see gender heading in future societies?

Bornstein: I grew up in the 1950s in the “great America” everyone wants us to be again! But the fact that, today, people are motivated by a wish for inclusion, a wish for cooperation, a wish for breaking down barriers—that never existed when I was growing up.

Where do I see gender going in the future? Which future? One hundred years from now? Two thousand years from now?

Drucker: Either.

Hobbes Ginsberg, Self-Portrait, Los Angeles, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Bornstein: There’s a Star Trek movie, Star Trek: Nemesis (2002), that starts with a great big dinner party, and all the Federation officers are in dress uniform, and it’s a fancy do, and Commander Data is welcoming people, and he says, “Ladies and gentlemen, and invited transgendered species.”

Drucker: Really?!

Bornstein: Oh, yes. They are some of the first words of the movie. When I saw that, I was rocked to my core. That made me think, “Okay, I exist in a future of Star Trek.” What’s more, in 2002, transgender was an inclusive word. Transsexual was the binary word. He didn’t say “transsexual species.” He was talking nonbinary. So, I see the future of gender as being included as neither-nor, just being acknowledged. That will be gender. It won’t be worldwide. But my God, Gender Outlaw has been published in China, Korea. People are thinking about this shit.

Drucker: I think that people will continue reading Gender Outlaw two thousand years ahead. Star Trek time in the future.

Bornstein: Let’s hope for favorable rebirth in a universe that’s still exploring gender. That would be swell.

Read more from Aperture Issue 229, “Future Gender,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Gender Is a Playground appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 16, 2017

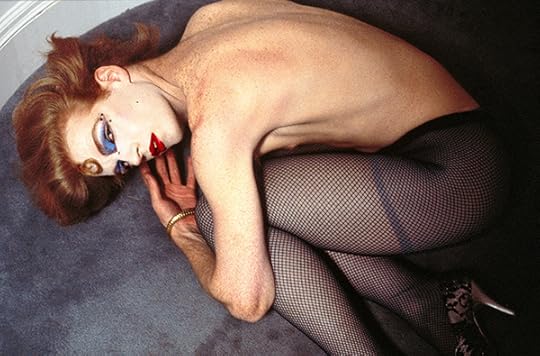

The Cult of Walter Pfeiffer

Delighting in male beauty and gender play, a prolific Swiss photographer reinvented the rules of attraction.

By Alistair O’Neill

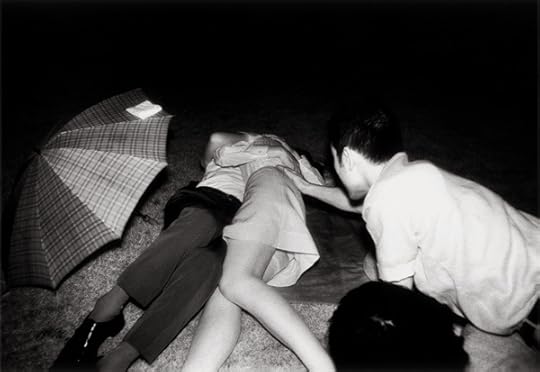

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 2009

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

Visiting the photographer Walter Pfeiffer in his studio in Zurich, you find an orderly space, painted white, possessing the trappings of a typical design studio: swivel chairs, Pantone pens, and a white Formica tabletop on trestles. Yet, lining the walls are exquisitely arranged mood boards, wrapping paper, photographs, posters, plastic props, and a Technicolor cornucopia of cascading bolts of cloth. Early in his career, Pfeiffer was a window dresser for a department store, where he learned the skills of arrangement. Today, he still employs this way of working to test environments and themes for commissions, as if he always has the shopwindow in mind.

Now in his early seventies, Pfeiffer has never been in greater demand. His photographs are exhibited and published worldwide, and he continues to work commercially, represented by a leading fashion-image agency, Art + Commerce, which handles the likes of Steven Meisel, Patrick Demarchelier, and Paolo Roversi. Pfeiffer’s style readily connects with the preoccupations of contemporary image makers with whom he is now identified, such as Jack Pierson, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Ryan McGinley. Yet, he emerged in the 1970s with an earlier generation of photographers that included Larry Clark, Duane Michals, and Peter Hujar, who explored the instability of gender and sexuality in relation to the male body. To look at a Pfeiffer photograph, such as the lead image for the 2017 exhibition Smoke Gets in Your Eyes at F+F design school, in Zurich, of a bare-chested young man exhaling a curling puff of yellow smoke between cupped hands—like a modern-day satyr performing at a party—is to be reminded that masculinity is now rooted in self-awareness, a kind of disruptive sexualization. This is the legacy of the liberation movements of minority groups who undermined the hegemony of heterosexual masculinity in the 1970s.

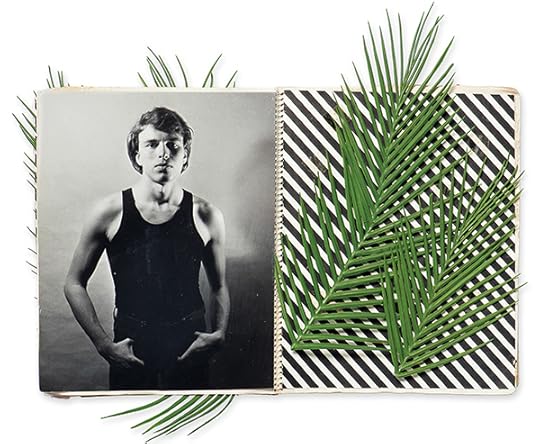

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 1974–81

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

Pfeiffer’s work first garnered attention in 1974 as part of the group exhibition Transformer: Aspects of Travesty at the Kunstmuseum Luzern, in Switzerland, curated by Jean-Christophe Ammann, who would become Pfeiffer’s long-term editor. The title references Lou Reed’s 1972 album; Transformer was the first museum exhibition to explore transvestism and nonnormative sexualities as represented in art, fashion, and music. The show brought together American and European practitioners such as Andy Warhol, the Cockettes, Jürgen Klauke, Luciano Castelli, and Urs Lüthi. Pfeiffer exhibited a set of photographs of a young transsexual, Carlo Joh (pictured opposite, bottom right), taken over a number of months in 1973. They charted, across black-and-white images printed on cheap photo paper, a boy in differing states of gender, oscillating between nakedness and drag with the aid of makeup and accessories. Pfeiffer recalls that the sequence “started with Carlo Joh in his blossoming beauty and every time when he came—we photographed maybe once a month—he got thinner, and you see this in the pictures.” Carlo Joh died unexpectedly soon after the photography sessions ended, and before Pfeiffer first worked with Ammann on selecting the photographs for display.

The work has an intense beauty, depicting a person at their moment of becoming, just before that beauty is taken from them. As portraits, they show the strength and vulnerability of the trans boy in the visual register of both his glamour and decline. Writing in the introduction to Peter Hujar’s 1976 book, Portraits of Life and Death, Susan Sontag identified two impulses in photography: one that “converts the world itself into a department store,” and another that “converts the whole world into a cemetery.” The theory evoked how photographs aestheticize and commodify subjects as much as they ossify them, by marking the beauty of their moment in front of the camera as time passes. Like Sontag’s theory, Pfeiffer’s photographs of Carlo Joh invoke the department store and the cemetery, just like Hujar’s Candy Darling on Her Deathbed (a portrait of a Warhol superstar in declining health, now regarded as a significant image of trans identity), also taken in 1973. What makes Sontag’s formulation particularly relevant to Pfeiffer is that he actually worked as a department-store window dresser before becoming a photographer.

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 2005

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

In the mid-1960s, Pfeiffer was employed at the Globus department store in Zurich, where, he recalls, “you had to create an atmosphere because it was a stage. So you learned what works up and what works down, and about depth, height, and framing, even though I never touched a camera.” Pfeiffer’s training in the commercial gaze taught him how to construct visual seduction, and it translated readily into a self-taught mode of photography that placed value on the look of things. This made Pfeiffer adept at backgrounds, scenarios, and settings, as well as how to direct a model’s gesture and how to frame elements within an image.

Pfeiffer was soon promoted to assist the art director of Globus magazine, the department store’s promotional catalog, learning illustration, typography, photography editing, and layout design. This led him to enroll in the newly opened private art college F+F (a reference to Form und Farbe, the Bauhaus term for form and color), established in 1971 by Serge Stauffer, a Marcel Duchamp specialist, and the artist Hansjörg Mattmüller, who greatly influenced Pfeiffer and first revealed to him that Warhol was a homosexual. It was much later that Pfeiffer found out that Warhol also had an early career as a window dresser and fashion illustrator, but the revelation of his sexuality encouraged Pfeiffer to be open about being gay. At F+F, Pfeiffer, a student of painting and drawing, was exposed to art history via Dada, a movement that started in Zurich at the Cabaret Voltaire, and to contemporary Swiss design, typified by graphic designer Josef Müller-Brockmann. The design principles absorbed during his schooling are visible in his 1977 portrait series Chez Walti, which includes Pfeiffer as a model, and makes use of brightly colored backgrounds and matching food props. His ongoing, confident handling of saturated color and graphic motifs were born out of a calibrated approach to art directing his own work.

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 1974–81

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

After being introduced to British Pop artist Peter Phillips via Phillips’s girlfriend, who ran a fashion boutique in Zurich, Pfeiffer arrived in London for a short trip in 1970. He met shoe designer Manolo Blahnik (who had seen Pfeiffer’s shoe illustrations in Twen magazine) at the opening of an exhibition at Arthur Tooth & Sons by Pop artist Allen Jones, which displayed fetishistic female mannequins posed in furniture forms—a chair, a table, a hatstand—that would incite feminist criticism. Staying with Blahnik in his Notting Hill flat, Pfeiffer unwittingly entered a small enclave of fashionable creatives who were obsessed with nostalgia and fed on old movies shown at the Electric Cinema on Portobello Road. They included artist David Hockney, textile designer Celia Birtwell, fashion designer Ossie Clark, and fashion editor Anna Piaggi, and, as such, the scene connected to the culture of Warhol’s underground superstars in New York, which reprised the star system of Hollywood’s golden era and an interest in the aesthetics of the 1920s.

Returning to Zurich, Pfeiffer continued his job as a commercial illustrator, living in a small white room simply furnished with a bed, a table, and a television. “When I made my illustrations, I worked on the table, and when friends came round they sat on the bed, and then I started to use this camera to take pictures of them,” Pfeiffer remarked, referring to a small white Polaroid with which he shot copies of his illustrations. By turning the camera on his guests, he took his first photographs. Incorporating discarded window-display props from his day job, he created his own one-room nostalgic star system.

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 1975

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

The scale of his site-based, theatrical photography soon expanded when Pfeiffer, in the early 1970s, rented a large villa near the lake in Zurich to live in, regularly staging parties where guests would be sprayed with perfume on arrival and directed to be “always on camera” for the duration of the evening. But all the campy exultation these scenarios produced was tempered by Pfeiffer’s wish to segue into the everyday life of his friends, what he called “their habits, objects, and traces.” The edited, Muybridge-like run of connected images he took at these events was shown in 1974 at Galerie le Tobler, in Zurich, where photographs were collaged over textile samples set into cheap frames and bound photo albums of portraits were set out on tables for visitors to look through. The display offered glimpses into a way of life carried out by a group of young confidants without much money, but possessing the will to reinvent themselves by being photographed.

The presentation of the photo albums is reminiscent of Pfeiffer’s scrapbooks, made for his own satisfaction from 1969 to 1985, which are now celebrated for their incongruous and iconoclastic juxtapositions of found images, mixing male anatomy, objects, flora, fauna, and food to startling effect. In Pfeiffer’s world, everything is intense and nothing is natural; it is a queer material culture of sorts. Yet the color and combinations of Pfeiffer’s scrapbooks are far from the aesthetic found in the black-and-white photobook that made his name. First published in 1980, with a second edition printed in 2004, Walter Pfeiffer: 1970–1980 was, according to a 2003 Artforum profile, one of the two most thumbed-through photobooks during the 1980s at Printed Matter, a specialist bookshop in New York. (The other was Larry Clark’s 1981 Teenage Lust, which also operates in a terrain that is neither documentary nor pornography.) Pfeiffer’s book features young men he knew from teaching drawing classes at F+F, as well as those he met in local bars and clubs. The photographs show close crops of mostly naked bodies in a variety of positions. In some instances, modeling was brokered; the subject decided which frames could be used and which had to be destroyed. The final images were selected by Ammann, who insisted on including full-frontal nudity. As Pfeiffer recalls, “Without the cocks it still would have been a good book, but with those forceful things it was better.”

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 2004

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce

International recognition came to Pfeiffer much later, in the form of a survey exhibition and publication titled Welcome Aboard, shown at Galerie Schedler in Zurich in 2001 and the Scalo Project Space in New York in 2002, followed by a retrospective at the Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris in 2004. But a more prescient indicator of the changed world of visual culture is a 2005 profile that appeared in Butt, a Dutch gay-interest fashion magazine printed on pink paper and published by Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom. Butt (and for a short time its sister title, Kutt, which means “cunt” in Dutch) aimed to make a virtue of the number of gay creatives involved in the fashion world, promoting a European aesthetic for making queer sensibilities visible in fashion photography that veered away from the look of American hetero “porno chic” developed by Terry Richardson.

In addition to an interview with Pfeiffer and a survey of his photographs, issue fourteen of the publication contains a Marc Jacobs advertising campaign of Rufus Wainwright shot by Juergen Teller, an advertisement for a Wolfgang Tillmans monograph by Taschen, an article on fashion stylist Simon Foxton’s homoerotic scrapbooks, and a readers’ section, “Buttstuff,” featuring amateur photographs of readers’ behinds. It must have been a curious “arrival” for Pfeiffer, who had anticipated nearly all of the creative strategies for queer representation presented in the issue by more than two decades.

Walter Pfeiffer, Untitled, 2004

Courtesy the artist and Art + Commerce