Aperture's Blog, page 134

July 27, 2016

Doug DuBois on Chris Killip In Flagrante Two

My first encounter with In Flagrante (1988) was in San Francisco, where the year it was released I made regular visits to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore, and to the used bookstores sandwiched between the strip clubs on Broadway. It worked like this: I would go to City Lights to touch and ogle the unaffordable photobooks, read a few pages of an ever-growing list of post-structuralist or feminist literary theory and postmodern art criticism, then head over to Broadway to scour the bins in hopes of finding something more affordable (one such find was a $14.95 copy of Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence, from the True Crime section of Columbus Books).

In Flagrante, released by the progressive British imprint Secker & Warburg, known for publishing first editions of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Simone de Beauvoir, J. M. Coetzee, etc., found its way into the photography section at City Lights. I remember thinking, I should buy this, but I didn’t. So, like many people, I came to study the book in earnest through the Errata Editions facsimile from 2008. Here’s what I Iearned:

1. You can shift an image wherever you need—left, right, or off-center—so that the gutter bisects the photograph precisely where you want it, not simply where it lands relative to the page border. (While hardly an innovation unique to Killip or this book, this was a revelation for me.)

2. Photographs of children can be more than ciphers for innocence and suffering.

3. Anger, attenuated by art, holds fast.

Chris Killip In Flagrante Two Steidl • Göttingen, Germany, 2015 Designed by Chris Killip and Victor Balko 14 1/4 x 11 1/4 in. (36.1 x 28.6 cm) • 110 pages 50 tritone images Hardcover with jacket • steidl.de

In a recent interview with Martin Parr, Chris Killip shared a memorable (and snarky) comment from photographer Brian Griffin about the layout of In Flagrante: “I always knew that you were very fond of the gutter but I had no idea that you’d end up in it.” In this year’s newly designed, discreetly re-edited edition, In Flagrante Two, Killip reorients the book from portrait to landscape format, placing all the photographs on the right-hand page. The vertical images are sidewise to maintain their scale. I have to admit that I miss the choreography of the first edition; the engagement of the photographs with the gutter contributed to a restless dynamic that carried through the sequence of images. With its vastly improved reproductions and unencumbered views, however, In Flagrante Two invokes the statelier rhythm of a print portfolio.

Over the years, much has been made of Killip’s terse introduction to the original In Flagrante, especially its final sentence: “This book is a fiction about a metaphor.” That introduction, as well the other texts (by W. B. Yeats, John Berger, and Sylvia Grant), are absent from this new edition. The Scottish poet Don Paterson, writing for the Financial Times, celebrated this paring away with a parenthetical aside reserved for Killip’s best-known line: “I have still no idea what he means. The work is not a fiction, nor is it concerned with metaphor, if either of these words are to be conventionally defined.” However, in the first edition, Grant and Berger had argued together: “Fiction, I think, because it is a story, not just information. About a human tragedy not an accident. Metaphor because it is through metaphor that, at first and last, we seek for meaning.”

The photograph May 5th 1981, North Shields, Tyneside, is one of the three images newly added to In Flagrante Two. The date commemorates both the day the photograph was made and the death by hunger strike of IRA leader Bobby Sands, in HM Prison Maze. The image is placed within a sequence of photographs depicting food (grown, harvested, canned, and eaten), families at rest, dogs, children, and young adults at play. In the photograph May 5th, there are five children, two standing on a wall posing for the camera, the other three in various stages of either climbing up to pose, or clambering down to leave. Killip is at a distance and well above the children, so the background opens up behind them to reveal a housing estate with burned-out flats and the graffitied slogans “Bobby Sands Greedy Irish Pig” and “Smash the IRA.”

In 2012, the filmmaker Michael Almereyda interviewed Killip on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition Arbeit/Work at the Museum Folkwang in Germany, in which many photographs, including May 5th, were being shown for the first time:

Killip: I . . . went to the only place I knew that Bobby Sands was memorialized in any way. It was in a public housing project in North Shields, which is fiercely Protestant, and I photographed the graffiti in its context. Kids came up and asked could they be in the picture, and I said sure. For me, it was a very sad picture. . . . it’s about how history is lived by working-class people, and how bigotry is passed down, restraining and constraining lives.

Almereyda: The children seem kind of innocent of it.

Killip: They could be innocent of it, but they’re not unaffected by it. Your innocence can’t last. Bigotry is powerful.

Killip goes out to photograph graffiti in reaction to the death of Bobby Sands. He allows a group of children to enter the frame and pose for him. Undoubtedly oblivious to the graffiti behind them, the children think the photograph is of, if not for, them. Killip, however, is quite aware that the children’s presence enlarges the meaning of the image from an angry, ironic commemoration to a more conflicted image about the etiology of bigotry, nationalism, and the conflict in Northern Ireland. The belated inclusion of this photograph within the new sequence shifts meaning in the book, just as a novelist might by adding or excising a paragraph, a poet by removing a stanza, or the painter in Len Tabner painting, Skinningrove, N Yorkshire, who busily paints a roiling storm in front of an overcast seascape. All are fictions and metaphors at work and play.

Chris Killip In Flagrante Secker & Warburg • London, 1988 Designed by Peter Dyer 9 5/8 x 11 7/8 in. (24.6 x 30.2 cm) • 96 pages 50 black-and-white images • Softcover

Perhaps the central motivation and best measure of Killip’s photographs are their distillation of inchoate feelings—anger, righteousness, respect—into a carefully considered argument and concise form. In 1989, poet and critic Daniel Wolff concluded his review of In Flagrante with the question: “What can we do to respond to the kind of public neglect documented in Chris Killip’s book?” In February of this year, poet and critic John Yau titled his review of In Flagrante Two “What Will You Do About Chris Killip’s Challenge?” Dana Lixenberg, Khalik Allah, Zoe Strauss, Dave Jordano, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Stephen Gill are just a few of the artists answering this challenge, and presenting their own. But whether or not we do anything in response to Killip’s photographs is hardly a measure of their worth, nor is the negligible change in conditions that gave rise to their making a cause for indifference. The project of art is long, and my answer to Yau’s question is simple: keep working.

DOUG DUBOIS has received fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and National Endowment for the Arts. DuBois teaches in the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University, and his most recent book is My Last Day At Seventeen (Aperture, 2015). A survey of his work, In Good Time, opened at Aperture Gallery in March 2016.

The post Doug DuBois on Chris Killip In Flagrante Two appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

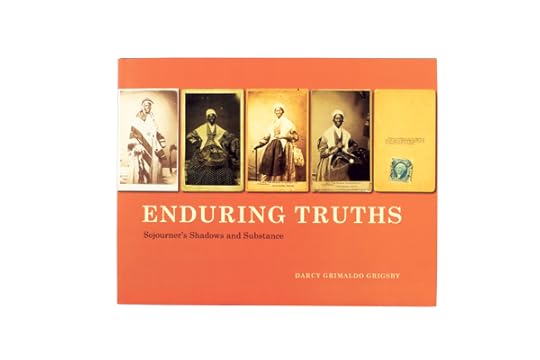

Vicki Goldberg on Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance

In 1826, a thirty-year-old slave named Isabella Baumfree escaped from captivity, taking her baby with her but leaving behind her husband and three other children. She would become someone else: legally free, an outspoken and effective supporter of the abolitionist cause, and a woman who fully understood and astutely utilized the rising power of photography and of the press. Although she was and remained illiterate, she was also a much-published writer and sought-after lecturer. Changing her name to go with her changed circumstances, she entered history as Sojourner Truth.

Darcy Grimaldo Grimsby’s Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance is an admirable and admirably expansive scholarly enterprise that tracks down twenty-eight different photographic portraits Sojourner sat for, which she had reprinted multiple times and sold (for 25 to 40 cents apiece) to support her lectures and her life. Grigsby also teases out the message Truth meant to convey, then fills in a fascinating history on the uses and impact of photographs on abolitionism and the post–Civil War era.

Assisted by friends and relatives, Truth wrote innumerable letters to newspapers, asking that they be published. That an illiterate ex-slave in the mid-to-late nineteenth century should have had such a clear, such a modern, understanding of the persuasive (and propagandist) power of both photographs and the press is a fact to be engraved upon the mind. This book should be read in tandem with John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier’s Picturing Frederick Douglass (Liveright, 2015), discussed in the Spring 2016 issue of Aperture magazine, “Vision & Justice.” Together, these two books generously enlarge the story of photographic and racial history in this country. (Full disclosure: John Stauffer is a friend, but anyone should find this book remarkable.)

Truth was an activist; she lectured and wrote on behalf of abolition and, during the war, on its behalf as well, for she believed it was being fought to abolish slavery. When her grandson enlisted in a colored regiment, she posed for portraits with his framed photograph on her lap—until he was captured, which often meant death at Confederate hands. The photograph within the photograph indicated a direct contribution to the cause, the closest a woman could come to actual soldiering. After his disappearance, Truth posed with her knitting, another sign of patriotism, as women knitted to keep soldiers warm. She also taught knitting to black women to give the unskilled a skill—slaves did not knit. Always she presented herself as a respectable, intelligent woman, far removed, and properly so, from the imagery of slavery.

Truth’s photographs were mostly cartes de visite, cheap and easily disseminated through the recently reformed post. (How apt that she named herself Truth at a time when photographs were thought to be truth incarnate.) Cartes de visite, which had been crucial to Lincoln’s first election and were key elements in the first celebrity craze (as discussed in my 1991 book The Power of Photography), were the first mass-produced photographs. Truth copyrighted hers and added the text: “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.” Like many an entrepreneur, she ran her sales as a private business. She also made extensive use of the nascent mass media, the newspapers and journals that proliferated in the North.

Her portraits (and Douglass’s) were civil rights photographs: some to propagandize for the Civil War, all to announce that black Americans deserved the same respect that whites did. Photographs have continued to contribute heavily to that cause. In the 1960s, pictures of fire hoses and dogs loosed on black Americans helped spur government action, and more recent smartphone and police body-cam videos of police action against black people have ignited peaceful protests, riots, dismissals, trials, and investigations. Enduring Truths illuminates the resourcefulness and importance of one woman at an early stage of this struggle, limns a detailed map of her sojourn, and underlines the vital role photography has played from the moment when technologies, history, and social change first put it on center stage.

VICKI GOLDBERG’s forthcoming bio of Bruce Davidson, part of a series on Magnum photographers, will be released this spring as Bruce Davidson: Magnum Legacy (Prestel, 2016).

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby

Enduring Truths:

Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance

University of Chicago Press • Chicago, 2015 Designed by Ryan Li

10 7/8 x 8 1/2 in. (27.6 x 21.6 cm) • 240 pages

156 black-and-white and color images

Hardcover with jacket • press.uchicago.edu

The post Vicki Goldberg on Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

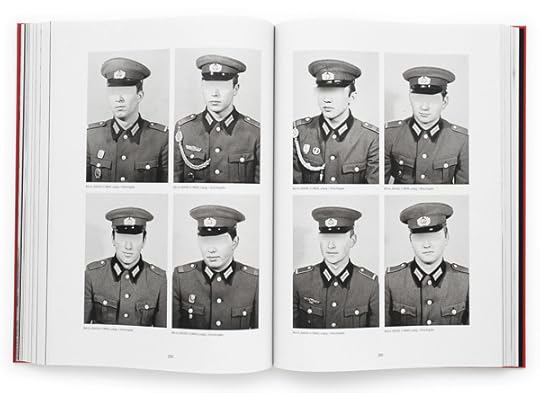

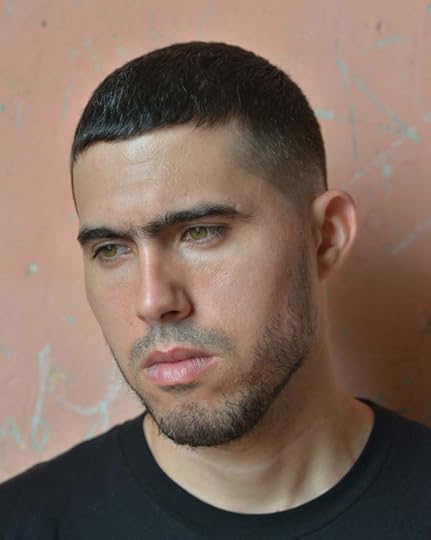

Eugénie Shinkle on Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin Spirit is a Bone

The images in Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chagrin’s Spirit is a Bone were made using advanced facial recognition software, which gathers data from four separate lenses and builds a model of the face according to the configuration of the skull—the spaces, unique to each face, between eyes, nose, and mouth. The resulting three-dimensional images, all depicting citizens of Moscow, are data visualizations rather than photographic portraits per se. Usually taken without the subject’s knowledge, they are euphemistically termed “non-collaborative” by the Russian engineers who designed the software used to create them.

The book takes its title from Hegel’s claim, in The Phenomenology of Spirit, that “spirit is a bone”—that the essence of the human subject is revealed not through the physiognomy of the face, but through the enduring material of the skull. Both facial recognition and forensic anthropology also rely on the shape of the skull to establish identity. The fleshy parts of the face are said to be capable of deceit through camouflage, decay, or shifts in expression; the bony structure beneath is not.

Similarly, the cameras that generate these images treat the tissue of the face as a thin layer of ephemeral material—a mask worn over the skull. Glossy and slightly elevated from the matte, white ground of the page, Bloomberg and Chanarin’s portraits seem just as easily stripped away from their substrate. Identified only by labels based on each individual’s position in Moscow society—machine operator, philosopher, city dweller—they recall attempts by earlier photographers, such as August Sander, to use the photograph as a tool for sorting and classifying. But here these designations are as inconsequential as the facial features of the subjects they name.

The subjects of these portraits wear the unguarded expressions of those who are unaware of the camera, but the odd, oblique angles and heavy foreshortening make their faces difficult to recognize. The distortions introduced by the software—features warped and doubled, lips clamped tightly—appear grotesque to human viewers, but not to the algorithms that will read the data the images contain. These portraits were not intended for human eyes.

Spirit is a Bone offers a biting commentary on the predictive and preemptive use of imaging technologies by military and law enforcement agencies. Facial recognition is part of a global surveillance industry, generating images that are gathered by the state for future use against its own citizens. The resulting archives are political instruments designed to manage the social body—in this case, as Eyal Weizman remarks in conversation with the artists, by “interrogating the future before it is materialized.”

Barthes’s famous dictum about the portrait photograph as a “closed field of forces” is couched entirely in the personal pronoun “I.” For Barthes, the portrait was a form of social exchange. “Non-collaborative” portraiture belongs to a new field

of forces, in which the face is no longer a living expression of humanity, but yet another digital trace left by the subject in a society increasingly preoccupied with the management of risk and the possibility of threats from within.

EUGENIE SHINGLE is reader in photography at the Westminster School of Media, Arts, and Design in London. She lectures and publishes widely about a number of areas related to photography, including fashion, landscape, globalization, and body/technology relations.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin

Spirit is a Bone

MACK Books • London, 2015

Designed by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, with Grégoire Pujade-Lauraine

6 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (16.4 x 21 cm) • 240 pages

134 black-and-white images • Hardcover

mackbook.co.uk

The post Eugénie Shinkle on Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin Spirit is a Bone appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 26, 2016

Revisiting the Berlin Wall

In the 1960s, East German border troops photographed the entire length of the Berlin Wall, but the film was never developed. Fifty years later, a new book brings a secret archive to light.

By Lisa Andergassen

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, from Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016 © Arwed Messmer, using BArch, DVH 60 Bild-GR35-10-014

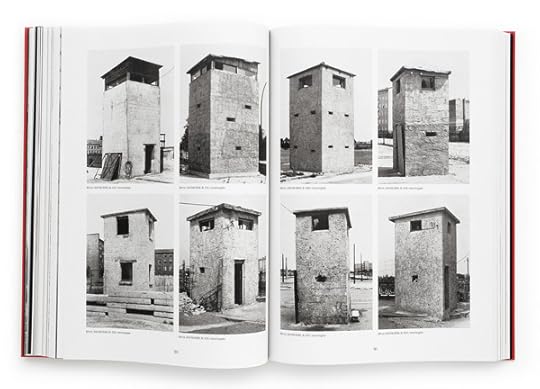

Black-and-white panoramas portraying ragged dugouts, hunched-up on hillsides, half-buried under pale sand and shaggy plants, or hastily erected, with roofs covered up by pine branches. In the background, vaguely perceptible fences and wooden stakes. Towers, stretching upward like deerstands on stilts, or listing closer to the ground, dumpy and rectangular, made of concrete. In all of them: the Berlin Wall, fragmented, sitting unspectacularly in No-Mans Land, or cutting through Berlin’s urban landscape.

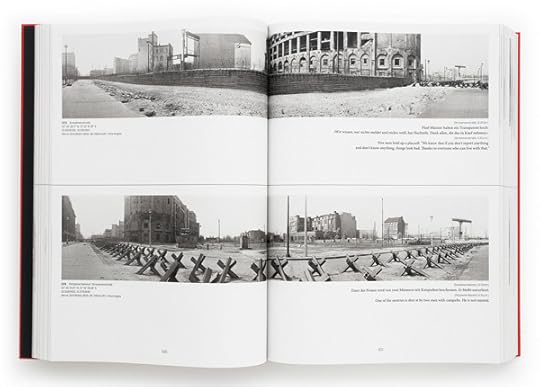

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, spread from Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016 © Arwed Messmer/Annett Gröschner

Taken by members of the East German border patrol between 1965 and 1966, these photographs were meant to be destroyed after they had served a banal function: to track down the weak spots in the wall. The wall itself was supposed to be picture-less. Photographing the wall was strictly forbidden and convictions carried a charge of two years in prison, turning the wall into an abstract object for GDR citizens outside of Berlin. But for reasons unknown (or perhaps pure sloppiness), the film was left undeveloped and forgotten in the federal archives of the GDR and later in those of united Germany—remnants of a compulsive regime, which translated its totalitarian claims into relentless documentation.

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, spread from Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016 © Arwed Messmer/Annett Gröschner

In 1995, while working in the Intermediate Military Archives for a research project on Berlin’s Gleimstrasse, photographer Arwed Messmer and writer Annett Gröschner stumbled upon the rolls of film, piled in an unremarkable box. It was an accidental but not entirely coincidental discovery. Both artists are archive veterans, frequently de- and re-contextualizing historical documents in their works. Messmer addresses the role of the photographic medium as an accomplice of power, while enabling an approach that leaves open avenues of mystery. (In his 2014 book Reenactment MfS, he displays chilling pictures from the Stasi archives without any accompanying text, only revealing their source in a small booklet enclosed as an appendix.) In Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, published by Hatje Cantz and accompanied by an exhibition currently on view at Haus am Kleistpark in Berlin, Messmer and Gröschner restore the material from the Intermediate Military Archives, complete with maps and texts based on files and protocols.

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016. Installation view at Haus am Kleistpark, Berlin, 2016 © Arwed Messmer/Annett Gröschner

The bright red, hand-bound ten pound book comes in two volumes. The first is overflowing with digitally arranged panoramas of the entire length of the wall—156 kilometers cast in concrete and barbed wire. The pictures are accompanied by meticulous captions and excerpts of statements yelled over the wall, and recorded by the East German border patrol, which bear witness to encounters between East and West Germans: “A woman shouts out of the 8th story of an apartment tower in the Märkisches Viertel: ‘Do you want beer?’” Stories of arrests are boiled down into single exchanges. (“When he locked his Trabant car, he asked: ‘If I drive off now, will you shoot?’”) By showing the entire range of the often monotonous pictures, Messmer gives a sense of the wall’s colossal scale, as it bisected desolate landscapes as well as recognizable parts of central Berlin.

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, spread from Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016 © Arwed Messmer/Annett Gröschner

The second volume dissects selections of single images into typologies that recall the works of German conceptual photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher: fortifications (such as towers and dugouts); abandoned ladders and bikes; tunnels; border patrol members; and things, like chaotic piles of gloves, backpacks, cigarettes and shoes, or lunch-ensembles with thermo bottles and untouched sandwiches. These images, taken by photographic amateurs, have a strange appeal. Frontally directed flashlights emphasize random objects that happened to be in the foreground, transforming evidentiary photographs of tunnels—carved in the ground to bypass the wall—into weird-looking earthen holes, inhabited by bizarre creatures with cable-like tentacles.

Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall, 2016. Installation view at Haus am Kleistpark, Berlin, 2016 © Arwed Messmer/Annett Gröschner

As the title suggests, Taking Stock of Power enables an “other view” of the so-called “Antifascist Protection Wall.” The photographs have historical merit as impeccable and rare documentation of the wall. But Messmer and Gröschner release them from the bureaucratic conditions of their production. Freeing up the material without effacing its origins, Messmer and Gröschner’s project is a discrete but deeply political gesture. Taking Stock of Power returns to the public an archive denied under the GDR regime and resists any strict interpretation. The wall may be gone, but its stories continue to emerge.

Lisa Andergassen is an academic researcher, writer, and editor based in Berlin.

Taking Stock of Power: An Other View of the Berlin Wall is on view at Haus am Kleistpark in Berlin through August 21, 2016.

The post Revisiting the Berlin Wall appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Andrew Stefan Weiner on Marcel Broodthaers Musée d ’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicité

The Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers has long suffered from a bifurcated reception: while his work has been shunned by many, due in part to his reputation as a hermitic figure or a stylistic outlier, it has been championed by others, who see it as a pivotal threshold in the development of critical post-conceptual art. Mindful of this divide, a major international 2016 retrospective currently on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art has sought to complicate viewers’ sense of Broodthaers’s oeuvre. The present moment seems like an apt time to reevaluate the 1995 publication Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicity, which corresponded to the re-exhibition of one of the artist’s most complex and provocative works by the same name. Section Publicity, or “publicity section,” first shown at documenta 5 in 1972, was the culminating installment of Broodthaers’s attempt to critique the institution of art by developing an elaborate, semi-fictional “Museum of Modern Art.” Acknowledging but distancing himself from the intense antagonisms of 1968, the moment in which the work originated, Broodthaers framed his exhibition as “a political parody of artistic events,” and vice versa.

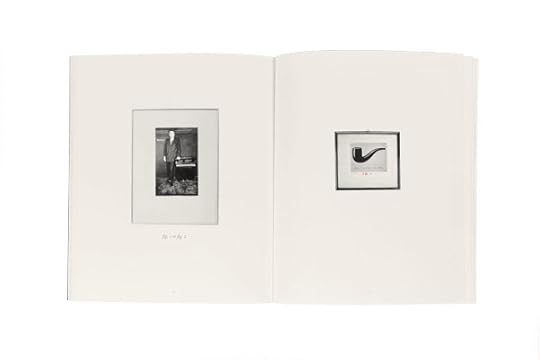

Marcel Broodthaers, Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicité, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, 1995

If such a formulation suggests the ambitions of the artist’s project, it also represents the sort of disorienting reversal characteristic of his highly oblique style. This gnomic tendency pervades Broodthaers’s “museum,” which archives a bewildering, heterogeneous array of images. The most legible of these are installation shots from documenta 5, where Broodthaers installed a small, freestanding gallery that functioned as his museum’s Département des Aigles, or “department of eagles.” (This display was meant to stand in for the “actual” museum, then on display in Düsseldorf, which consisted of a sprawling collection of eagles of every conceivable kind, borrowed from museums and private collections.) The interior and exterior of the gallery were hung with photographs and facsimiles of this collection, interspersed with some original objects. The display also included advertising posters, pseudo-informative signage, empty frames, a slide show, and a shipping crate used in the museum’s first incarnation. Most of these displays are dedicated to the eagles, which assume any number of incarnations: military helmets, flags, beer bottles, tattoos, typewriters, taxidermy, statuary, and a seemingly endless array of other forms.

As this selective list would indicate, the apparent authority of Broodthaers’s institution is undone by the rampant heterogeneity of its contents. The brilliant economy of his joke is that a seemingly arbitrary criterion generates a body of data that is perfectly organized but also useless, insofar as it seems to simultaneously signify one thing, everything, and nothing. This resistance to meaning is typically read as a satire of modernity’s will to knowledge and as a criticism of the institution of art—not just museums, but the discourse of aestheticism more generally. While Broodthaers’s focus on the eagle has been linked to an interest in fascism and the iconography of power, his inclusion of advertising imagery has been seen as signaling the interpenetration of art and spectacle. Although these readings remain compelling, one wonders what other sorts of interpretative possibilities are opened by his museum. It is also worth questioning how one might read this book as something other than a document of a particular exhibition. Broodthaers once referred to his museum as a “novel of objects.” Is it possible that this book might be read as a novel of images?

ANDREW STEFAN WEINER teaches art theory and criticism in the Department of Art and Art Professions at NYU Steinhardt. He has written about contemporary art for publications, including Texte zur Kunst, Afterall, and ARTMargins.

The post Andrew Stefan Weiner on Marcel Broodthaers Musée d ’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicité appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 21, 2016

Memories of the African Diaspora: A Conversation with Nicola Lo Calzo

Since 2010, the Italian photographer Nicola Lo Calzo has traversed the Atlantic coasts to research buried memories of the African Diaspora. His latest installment, Regla, taken in Cuba, is the sixth and last chapter in an album entitled Cham, following series in West Africa, Guadeloupe, Haiti, the southern United States, French Guyana, and Suriname, each of which set the stage for photographic journeys through history. Mixing documentary and art photography, Regla reveals a society’s solidarity and resistance to oppression. I spoke with Lo Calzo in advance of his exhibition of Regla, currently on view at the fourth edition of the PORTRAIT(S) festival in Vichy, France. —Yves Chatap

Nicola Lo Calzo, Reinier, Sibooney Beach, Santiago, 2015. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Yves Chatap: In the introductory text to your series Regla, you write, “There are two Cubas . . . ” What do you mean by this?

Nicola Lo Calzo: This idea of “two Cubas “comes from a desire to report on another story about a country that is often sidelined by the revolutionary story. For example, in Cuba, there is a form of negotiated freedom governed by religious and secular rituals. At the time of Spanish colonization, African descendants developed spaces of emancipation which are now owned by the majority of Cubans. Despite the complex socioeconomic and political developments that have animated Cuba since the beginning of the communist revolution, all of these practices have retained their original functions. In all the groups that I photographed, such as the masons, the Abakuá secret society, the families of Santeria, the Cabildos de Nacione Africana, and the hip-hop community, there are strong links of solidarity and mutual assistance that have persisted since the creation of Afro-Cuban communities during the time when the country was still a colony.

Nicola Lo Calzo, The Sacred Chalice with medicinal plants used to purify the places and the people present at the Abakuá ceremony, Erionda Efo secret society, Regla, 2016. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: How does this new series connect with your work from the series Casta, which focused on the southern United States?

Lo Calzo: The series Regla and Casta are both part of my long-term project on African heritage and memories of slavery in the Atlantic world, which I began in 2010. In Casta, I turned my eyes to the legacy of slavery during the antebellum period in Louisiana and Mississippi, and focused on the different ways local communities have been re-appropriating the past. While in Cuba, I explored some of the existing Afro-Cuban cultural practices, developed during that country’s slave era. Within these religious or secular practices, the Cuban—irrespective of color or political affiliation and far from the revolutionary ideology—expresses herself as an individual. I’ve always been interested in the question of identity, either through gender, race, memory, or difference.

I started this project about postcolonialism when I moved to Paris. In talking with my friends, I wondered about the impact of racializing assigned identity through this issue of visible or invisible community. In trying to understand how this subject had impacted the life of my African or Caribbean friends, while also trying to understand their roots, I became interested in African history and European colonialism, and that’s how I began to work on the memory of slavery. Another key point for me is empathy, because even if we may belong to different worlds, empathy allows us to identify with each other. This sense of empathy remains complicated because we have to be very careful how we approach each other, and learn to deconstruct or “decolonize” our own eyes.

Nicola Lo Calzo, Young Ecobios shows their Abakuá signatures (firmas) in the form of tattoos, Munongo Efo secret society, Regla, 2015. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: Let’s go back to your most recent series, Regla. What does this title mean?

Lo Calzo: For Cubans, this title immediately refers both to state power and Afro-Cuban Heritage. It is a nod to the Cuban society built on dogmas, on rules. So, Regla has several meanings. It refers to a small town facing the Bay of Havana, which is considered a major religious center and includes Santeria, as well as the male secret society Abakuá. Regla is also a reference to how Cubans designate different religions such as Santeria, also known as called Regla de Ocha, an Afro-Caribbean practice derived from Yoruba and Catholic beliefs, or the Abakuá religion named Regla. But there is also a subtlety here, as “regla” refers to the precept, to the order.

Nicola Lo Calzo, Anajulia, initiated in the Regla de Osha, during the initiation ceremony of her daughter, Eva Isabel, Los Olmos neighborhood, Santiago, 2015. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: How did you decide to make work about the secret society of Abakuá?

Lo Calzo: Abakuá is an Afro-Cuban secret men’s society shrouded in mystery. For me, it was a challenge to be able to attend ceremonies and make images. I had seen only a few drawings about their practice from the nineteenth century as well as rare photographs from the last fifty years. In the Afro-Cuban religious system, Abakuá is one of the most respected and feared societies because it is based on strict ethics associated with “manhood,” so very little photographic work had been made. Through the society, young men are affirmed as members, they gain a social role, and they achieve the respect of the community.

In these temples there is a form of freedom and emancipation from the Cuban regime: the youth at the margins of the revolution are flourishing in this space. It is also one of the rare places where the state allows gatherings. Through this series, I wanted to show the continuities and discontinuities between the Cuban present and the colonial past. Today, Abakuá societies are real places of “transculturation”—these areas are open to all people regardless of color, political ideology, or social class. This inclusivity has been driven, in part, by the revolution. The hip-hop movement, some of whose members are also part of the Abakuá society, is fully involved with this Afro-Cuban history that questions the black identity and popular racism within Cuban society.

Nicola Lo Calzo, Barbaro, DJ lapis, and DJ neurys, at a concert at the outskirts of Havana, 2016. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: The portrait is often at the center of your series. What is your interest in this photographic style?

Lo Calzo: It’s important for me to use different registers in my work. Some of my portraits are improvised, whereas others are staged. This juxtaposition allows me to restore the complex reality that I photograph, while finding a personal style in narration, as can be seen in my exhibition in Vichy. For the exhibition, the constraint was to highlight the portrait, and for this we had an ad hoc selection. Today, however, I need to complicate the narrative of my work. I want my work to be as eclectic and hybrid as possible, and to reflect the subjects I photograph. This approach allows me to move from documentary photography to portraits, to give a precise rhythm that accompanies the spectator in my story.

Nicola Lo Calzo, Elocuente, Rap Artist, Centro-Havana, 2016. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: Now that you’ve come to the end of Cham, what have you learned from telling these stories about the African Diaspora around the world?

Lo Calzo: I have learned a lot about people, myself included, throughout my many travels. I have encountered extraordinary individuals and communities that are, for the most part, unknown and marginalized. One aspect of this experience that fascinates me beyond measure is the richness of cultures from African descent and their unfettered resilience, as communities that have been hanging in the balance since the slave era.

Most of the cultural practices depicted in my photographs were beaten into shape by virtue of harsh slave plantation conditions, not forgetting the abysmal hopelessness of slave ship holds. Against all odds, Afro-descendant communities still thrive, imposing their presence in the world, and affirming their otherness. I believe that the sum of their experiences, both different and complex, carries with it a universal value that belongs to all of us: the dignity of humanity and the power of life.

Nicola Lo Calzo, The Ireme Aberisun dancing in front of the temple entrance, Abakuá secret society in Guanabacoa, 2016. Courtesy the artist and L’agence à Paris

Chatap: What are your hopes for the future of the complete project?

Lo Calzo: Cham is both an art project and a research project. During all these years, I conducted numerous interviews, and created sound recordings of the ceremonies, rituals, and parades. I also made videos. And I never stopped collecting items of all kinds, archival documents, or simply objects related to the memories of slavery. I want all these different mediums to join in the complete exhibition of Cham. This synesthetic approach is, to me, the most interesting way to express the complexity of this subject, as well as my artistic ambition. I also expect to make a book, which will compile all of this photographic project as well as various contributions from the artists, the researchers, the anthropologists, the activists, and others people who worked with me and without whom we could never have access the stories I photographed. After Vichy, the next important step is Colombia: the Festival FOTOGRÁFICA, Bogotá, will exhibit the overall project of Cham in 2017, when the photographs, sound, video, documents, and objects will co-exist in a single story.

Yves Chatap is an art critic and curator based in France.

PORTRAIT(S) is on view in Vichy, France, through September 4, 2016.

The post Memories of the African Diaspora: A Conversation with Nicola Lo Calzo appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Celebrates the Launch of “Vision & Justice”

On Tuesday, May 10, 2016, the Ford Foundation hosted Aperture magazine for a special evening celebrating “Vision & Justice,” guest edited by Sarah Lewis, a landmark issue addressing the role of photography in the African American experience. Hosted by Darren Walker, President, Ford Foundation and co-hosted by Chris Boot, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis, the evening featured readings by Michael Famighetti, Sarah Lewis, Sarah Jones, Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, Garnette Cadogan, Margo Jefferson, Chelsea Clinton, and Khalil Gibran Muhammad. (Darren Walker intended to open the program, but was called away for work that took him abroad.)

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Aperture Celebrates the Launch of “Vision & Justice” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 20, 2016

From Three African Photographers, A Diverse Vision of Urban Life

An exhibition in Philadelphia explores African cities through street photography and portraiture.

By Ian Bourland

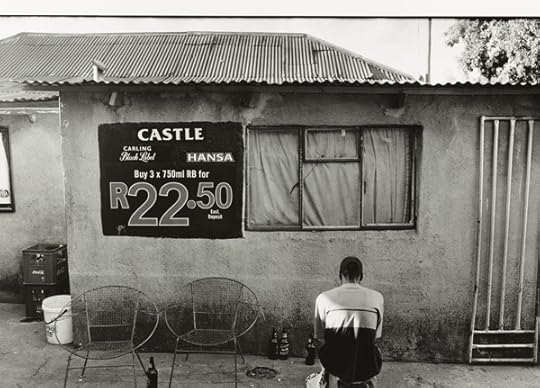

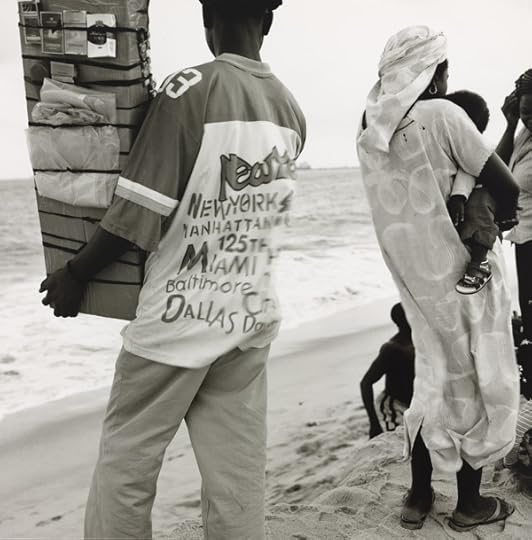

Ananias Léki Dago, Alexandra Township, from the series Shebeen Blues, 2008 © and courtesy the artist

This summer The Philadelphia Museum of Art has dedicated its Perelman building to a multifaceted program, broadly conceived as Creative Africa. While clearly intended to expose a wide audience to artists from the continent, the installations and related programming—including a textile display of Vlisco brand “batik” wax-resist cloth and a retrospective of Berlin-based Burkinabé architect Diébédo Francis Kéré—perpetuate the notion of a monolithic Africa as an exotic, if resourceful, wonderland. Challenging such misconceptions has been at the heart of recent curatorial work by, for instance, Okwui Enwezor, director of the 2015 Venice Biennale, or in Philadelphia two years ago with Yinka Shonibare, MBE’s Magic Ladders at the Barnes Foundation. Magic Ladders also used Vlisco-type fabric, but as a site of ambivalence precisely to challenge stereotypes that European or American audiences might bring with them into the gallery.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Untitled (Cairo, Egypt), 2002 © and courtesy the artist

Within Creative Africa, curator Peter Barberie has brought together a trio of veteran African-born photographers under the aegis of Three Photographers/Six Cities, which attempts to visualize a wide spectrum of quotidian life on the continent, but does so through small moments rather than wide angles. The exhibition endeavors to revise a tendency in many photographic representations of Africa—often taken by outsiders—that privilege exotic landscapes or terrifying conflicts, perpetuating what Enwezor, in his seminal exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (2006), calls “Afro-pessimism.” Indeed, Enwezor’s exhibition from a decade ago (as well as Simon Njami’s Africa Remix and Laurie Ann Farrell’s Looking Both Ways: Art of the Contemporary African Diaspora from the same period) set the tone for broadly conceived but theoretically nuanced exhibitions on African art. In his exhibition, Barberie pursues a more discrete, but nonetheless evocative, course: the three photographers—Ananias Léki Dago, Seydou Camara, and Akinbode Akinbiyi—consider six urban contexts by blending conventional street photography with quiet moments of portraiture.

Ananias Léki Dago, CBD, Johannesburg, from the series Shebeen Blues, 2007 © and courtesy the artist

Much of the geographic range here is provided by Léki Dago, whose work is drawn from several series exploring Nairobi, Bamako, and Soweto—three distinct urban spaces, each of which the photographer, Ivorian by birth and based in Abidjan and Paris, explored as a relative outsider. He describes his own process as less rooted in the decisive moment of street photography, and more about locating a visual metaphor that recurs in the landscape. Such tropes include the cruciform cart handles of local workers in Mali, the undulating waves of corrugated tin in Kenya, or shebeens, the informal bars common to black communities in South Africa. From the series Shebeen Blues (2010) on, his more recent work ventures into portraiture with hagiographic undertones. Taken together, Léki Dago’s 35mm projects tarry in soft focus and lyrical abstraction, seeking hidden or microcosmic zones in the everyday. In this sense, his own projects contrast with now-familiar modes of earlier African portraiture and photojournalism, such as that of Peter Magubane in South Africa, Seydou Keïta in Mali, or Paul Kodjo in Ivory Coast, whose archive Léki Dago is currently working to conserve.

Seydou Camara, Untitled, 2009 © and courtesy the artist

By contrast, Camara’s extended meditation on Tombouctou, a region of Mali famous for the Djingareyber Mosque, draws the viewer into a lush visual terrain that bears traces of the past. These smaller-scale works document sacred texts and the hands that bear them, and offer tight landscapes of a radiant and dusty city built around six-hundred-year-old mud and timber mosques. (Camara lives and works in Mali.) Tombouctou has long been a center of learning and cosmopolitanism in trans-Saharan Islam, a legacy now threatened by the emergence of radical factions throughout northern Africa. The only color pictures in the show, Camara’s delicate inkjets convey the region’s vast desert skies, arid streets, and brittle pages with a crisp clarity.

Seydou Camara, Untitled, 2013 © and courtesy the artist

The most arresting work in Three Photographers/Six Cities, however, is by the veteran Akinbiyi, whose square-format grid from his ongoing series All Roads immerses the viewer in the clamor of Lagos with bracing immediacy. A megacity of some twenty million, set across islands and waterways, one could dedicate a career to the place and scarcely scratch the surface. Although Akinbiyi, who was born in Nigeria and currently lives in Berlin, also takes on Cairo, All Roads conveys a sense of location and dynamism with concision, velocity, even pathos. His vision is one of a new urbanism that typifies much of Africa and the global hubs once relegated to the periphery.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Untitled (Lagos, Nigeria), 2004 © and courtesy the artist

This sensibility, in fact, is the central contribution of Three Photographers/Six Cities, which draws landscapes to the fore to represent the lived experience of specific African urban communities. Such cities are kinetic hubs of migration and uneven development, improvisation and adaption—from the seemingly timeless but now-threatened built environment of Tombouctou to the bustle of Lagos’s Yaba market. These narratives are framed by photographers living, working, traveling, and exhibiting their photography on the continent, which provide a diverse contribution of imagery to the wider concept, however vague, of Creative Africa. Still, a soundtrack on loop in the gallery pulls focus from the photographs. The music is a mixture of voices (from sinuous kora and funky Afrobeat, King Sunny Ade to Miriam Makeba) and a playlist of postcolonial classics. The experience is at once jarring—imagine seeing pictures of Mexico City set to “Born in the USA”—and also reinforces the tired misconception that visual art from Africa cannot be dissociated from the sonic.

Akinbode Akinbiyi, Untitled (Lagos, Nigeria), 2004 © and courtesy the artist

Ultimately, Three Photographers/Six Cities is a crucial proposition in its willingness to offer a more sustained and open-ended meditation on one dimension of contemporary landscapes, rather than issue generalizations, theoretical or otherwise. It also highlights the work of West African photographers who are far less known in America than their South African counterparts, such as Zanele Muholi or Pieter Hugo, who tend to have more gallery-level visibility here. Taken together, their projects confound common themes within recent displays of photography from Africa, from romanticism to pessimism. This latter point is especially crucial in the larger context of Creative Africa, which, for its benign intent, rehearses some by-now threadbare approaches to displaying a social landscape in constant flux.

Ian Bourland is an assistant professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Three Photographers/Six Cities is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through September 25, 2016.

The post From Three African Photographers, A Diverse Vision of Urban Life appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 19, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Renée Mussai in Conversation with Victor Peterson II

Coinciding with the release of Aperture’s summer issue, “Vision & Justice,” Renée Mussai, Curator and Head of Archive at Autograph ABP in London, discusses the politics of representation in photography from the African diaspora.

James Barnor, Eva, 1960. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Photography writes stories with light and, like sound, resonates within us. These stories are hieroglyphs to some, living word to the initiated. Etched on Shoreditch’s brick and pavement are stories from the anti-establishment dreams of the 1960s to the cultural movements of today. For almost three decades, Autograph ABP has told the stories of the black experience through photography.

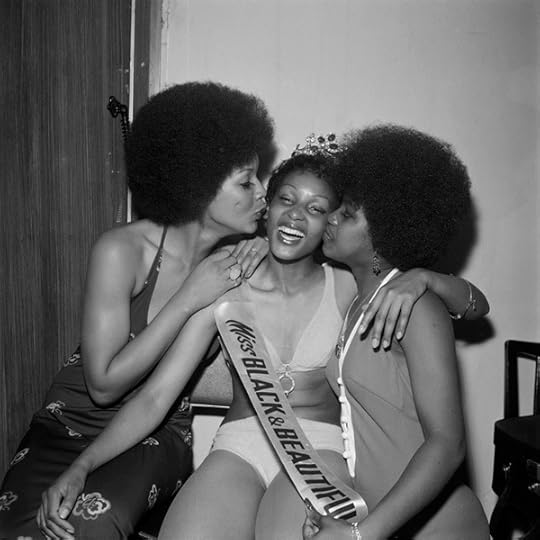

In 1988, Autograph ABP was established in London to advocate for the inclusion of black image-makers and black subjects in cultural institutions. Originally located in a Brixton office, its current location, as of 2007, sits at 1 Rivington Place in East London. The building’s matte grey façade, designed by David Adjaye, is nestled in scenery befitting that uneasy, yet coveted moniker of an “up and coming” neighborhood. Since moving to the East End, Autograph has presented numerous exhibitions including Black Chronicles II, Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism, James Barnor: Ever Young, Maud Sulter: Syrcas, and Raphael Albert: Miss Black and Beautiful. Exhibitions also tour internationally; Black Chronicles has traveled to Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta and The Hutchins Center’s Cooper Gallery at Harvard University, while James Barnor: Ever Young is currently on view at Theaster Gates’s Stony Island Art Bank in Chicago.

This spring, I spoke with the curator Renée Mussai at Autograph ABP about the thematic and historical resonance between Black British photography and the politics of representation in the African diaspora. Here, she discusses her research-led curatorial work focusing on archives, postcolonial portraiture, and the themes of race, gender, and sexuality in historic and contemporary photography. —Victor Peterson II

Renée Mussai, Curator, at the exhibition Black Chronicles II, 2014, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

Victor Peterson II: What first caught your interest in photography?

Renée Mussai: I was afraid you might ask me this! Growing up in Central Europe in the 1980s, as a product of an interracial union, with only one culture present and the other absent, my childhood was marked by an occasional longing for images that I could relate to personally, images that depict people who looked a little more like me. So from an early age onward, I have always been obsessed with images—the abundance of certain representations, and the invisibility of others. My sustained interest in the tradition of African studio photography, and long-term engagement with the work of photographers such as James Barnor, stems from a photograph taken in Mogadishu in the early 1980s. In that picture, my Somali relations, including my father and grandmother, pose against an elaborately painted backdrop. As a child, this photograph served as the only palpable link to “that” side of my cultural heritage: I was equally intrigued by the portrait’s artifice, and by the people in it, most of whom I had never met.

Renée Mussai, Madame Mulatresse, photo booth portraits, Migros supermarket, Switzerland, 1990s. Courtesy Renée Mussai

I grew up in the Austrian Alps with an extraordinary, wonderful single mother and a close-knit family. To encounter other Afro-Europeans, Africans, African Americans, or people from similarly mixed cultural backgrounds, was rare—in real life, or in pictures. Think of James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village,” a brilliant essay on his experience of living in a small Swiss village during the early 1950s. Picture that and then conjure an image of The Sound of Music . . . And so, in my early teens, I began a strange ritual of taking the train across the Swiss border to visit a particular shopping mall that housed a very special photo booth: one of those vintage machines that produces a strip of four different exposures resembling medium format square portraits. If I was feeling especially adventurous, I’d take a bag of props with me: a wig, make-up kit, accessories, et cetera. And, once inside, I’d try out different shades, different personae: from a pale-skinned Monroe-esque movie starlet fantasy, when I was twelve, to a revolutionary Angela Davis civil rights avatar, in my formative years, just before I left Austria for London. It was inside this miniscule enclave of a public-private hub that I fell in love with photography, while I was processing—literally—a range of existential moments. Photography offered a prism through which I could playfully engage with my own cultural identity, or identities, and explore different modes of being and becoming. A little narcissistic, most definitely, but necessary, too. Sometimes I’d invite lovers, friends, and family to join me in these portraits. And as an undergraduate photography student, in the early 2000s, I created my first art installation based on this archive of hundreds of images.

On a less self-indulgent note, the first time I used a camera myself was during an obligatory class visit to Mauthausen, one of Hitler’s main concentration camps in Upper Austria. I must have been about eleven or twelve years old, perhaps younger. Systematically photographing each room and each encounter was the only way I could comprehend and process the sense of haunting the place incited in me, the ontology of horror that was deeply imprinted everywhere, embedded in its walls, in the very aura of the place.

So I suppose the sum of these three experiences or impressions brought me closer to understanding and appreciating the remedial and political work images can perform—politically, culturally, personally.

Peterson: The title for Aperture’s summer issue is “Vision & Justice.” What does this mean to you? How is one implicated in the other, if at all?

Mussai: And a very intriguing title it is. One of the first things that comes to mind is the relationship between photography and human rights—inherent in Autograph ABP’s mission—and how photography can be deployed as a tool for resistance or oppression. Vision is also, of course, intrinsically linked to the act of seeing, a kind of apocalyptic or visionary seeing, if you will: seeing with determination, imagination, and wisdom; seeing for a cause, with conviction.

Young African American woman, three-quarter length portrait, facing slightly right, with hands folded on her lap, from African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Historically, I think of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “American Negro” installation, presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition, one of the most significant photographic interventions. Du Bois was effectively the first black curator of photography. His project was driven by an undeniable humanist concern and an undying belief in the visual as an effective political tool to institute social change. Together with others who shared his mission, Du Bois strategically deployed 363 photographs to stage a claim for the humanity of the black subject. And, in that moment, he was perhaps also the first scholar-activist who turned to photography as a campaign tool presenting visual “evidence” en masse. At Autograph, we presented a contemporary installation of 200 of these photographs under the title The Paris Albums 1900, which toured to the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at Harvard (now the Hutchins Center) in 2013, marking the fiftieth anniversary of DuBois’s passing.

I also think of When Harmony Went To Hell: Congo Dialogues, another recent Autograph project championed by Mark Sealy, which highlighted the human rights campaign in the Congo, where photography—through the lens of English missionary Alice Seeley Harris, a figure rarely mentioned in the history books—played a pivotal role in securing justice to end the genocide inflicted upon the Congolese people by the violent regime of King Leopold II of Belgium.

Alice Seely Harris, Three head sentries of the ABIR with a prisoner, Congo Free State, ca. 1904. Courtesy Anti-Slavery International and Autograph ABP

The concept of social justice as married to photography and cultural identity politics has been deeply embedded in our human rights agenda since the early 2000s, when Autograph first began to engage with artists such as Marcelo Brodsky, whose work deals with state terrorism throughout Argentina’s “Dirty War.” Implicit in this mission is a continuous investigation of questions around access, equality, and responsibility, and how these relate to the visual and privileged spaces of museums, galleries, and the academy. Mark Sealy, Autograph’s director since 1991, has spoken and written vigorously about the relationship between cultural violence and visual politics over the years. Under his vision, the organization has become an agency and gallery uniquely placed in incorporating human rights as an extension of race and representation in relation to photography, and increasingly also moving image works.

Maud Sulter, Duval et Dumas, 1993. Courtesy of Maud Sulter Estate and Autograph ABP

Peterson: What do you see as Autograph’s responsibility to and for representations of the black diaspora? For generations, people from all over the world have been settling in London, often coming from the UK’s former colonies. I’m thinking, historically, of the HMT Empire Windrush voyage from Jamaica to England in 1948—what many would say was a starting point for talking about the emergence of a black British culture in London.

Mussai: The “burden of responsibility”—where does one begin? It is important to remember that Autograph was born out of the black arts movement of the 1980s, a time of extreme Thatcherite conservative politics, serious oppression, marginalization, and discrimination. But this era was also a deeply creative time, when a pioneering generation of black artists entered art schools and infiltrated mainstream establishments; they also formed influential artist collectives and independent platforms to nurture their practices. Identity politics, for lack of a better term, played out across several, convergent lines of sexual, cultural, and racial differences, and many concurrent dialogues emerged out of this moment. There, are of course, many ways to look at the question of responsibility. One key aspect of our continuous curatorial responsibility lies in preserving the legacy of certain influential artists, such as the work of Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955-1989), a founding member and the first chair of Autograph ABP, or that of Maud Sulter (1960–2008), a pioneering curator, writer, and artist whose work we recently presented at Rivington Place, and at this year’s Rencontres d’Arles in France. Without sustained advocacy, these artists are invisible, their contributions erased, forgotten, which is, ironically, a prevalent theme in their work. Part of our mission is to inspire other institutions take notice, and consider these and other artists’ work in their collecting and exhibiting frameworks.

In addition to operating within contemporary and postcolonial creative spaces, we are increasingly turning our attention to mining image archives, contributing new knowledge to the ongoing writing and re-writing of photographic histories. While our work is often directed at filling gaps of a particular focus, the aim is to annotate and affect wider cultural narratives, and address what we refer to as a series of “missing chapters” above and beyond specific black or diasporic histories.

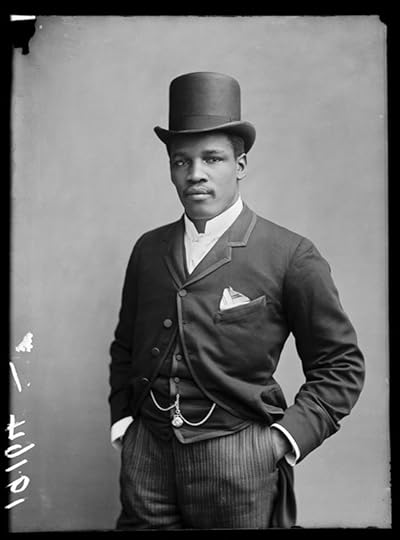

Peter Jackson, London Stereoscopic Company, 1889 © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

It’s interesting to me that you frame your question in the context of the Empire Windrush, as much of our recent curatorial work has been about quietly unsettling or dislodging this so-called watershed moment in 1948, too often erroneously cited as the beginning of a multicultural Britain. Oftentimes, our archive research arises out of the desire to disrupt established narratives of “arrival,” to unlock the coming of diaspora from a post-war moment. The black diaspora in Britain—and in the rest of Europe—is so much older than generally assumed: it dates back hundreds of years, all the way to the Roman Empire. For many years, Caroline Bressey, for instance, has been researching these so-called “hidden” histories of black presence in Victorian and Edwardian Britain in great depth, considering black women and their stories in particular. We know of different “presences” from art history, illuminated by great scholarly publications such as the multivolume series The Image of the Black in Western Art (recently re-published by Harvard University under the editorship of David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.). But paintings and drawings are often produced from the artists’ imagination, while photography in the nineteenth century was primarily seen as “evidential,” one of the reasons I believe why Black Chronicles II, our touring exhibition on black portraitures in the nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain, has resonated with audiences and critics alike. Many of the photographs in the exhibition were shown for the first time in more than 135 years, extracted from the Hulton Archive in London, one of the world’s oldest and largest image archives. Through this strategic partnership, made possible through our Heritage Lottery-funded Missing Chapter program, we were able to collectively affect the way the black figure is represented in nineteenth-century photography in Britain.

Returning to your question: to offer new knowledge about the representations of the diaspora, to ensure diverse voices are not only heard but acknowledged and incorporated in larger narratives, to preserve the legacy of those artists who have shaped this path, and to provide a platform for those working today in the charged arena of cultural politics and the visual, is where I see our critical responsibility as curatorial agents.

Peterson: In your work as a curator and scholar, do you think of yourself as telling a story with images or do the images tell their own story?

Mussai: Roland Barthes, I believe, once famously described the photographic image as “a message without a code.” Personally, I’ve always been more intrigued by the idea of deciphering a photograph’s “stored code.” I suppose I think of myself as a translator, or as a kind of mediator, an organizer, of images. That is not to say that images aren’t capable of telling a story on their own. I believe in photographs having a “voice,” albeit one that constantly shifts and mutates upon reception, and often the images themselves benefit from “interpretation,” mediation, advocacy.

Black Chronicles II, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2014. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

I’m interested in new image configurations and their concomitant reverberations that emerge through archival acts of resurrection, and at times bricolage. A lot of our work is driven by this Foucauldian notion of “excavation” and the creation of new narratives, new meanings, through the re-assembly of images and texts, which at one time or another, were “orphaned.” These stories change over time. The curatorial work needed is to provide a cohesive framework to channel their collective registers—their “voices.” The juxtaposition of text and image in Black Chronicles II is a good example, where a series of citations by the late Professor Stuart Hall on the gallery walls subtly animated the archival work on display.

Peterson: How do we write ourselves into history or make our own narratives through images? What takes precedence, fitting into a narrative or creating one’s own?

Mussai: Often, the desire to write new narratives is driven by a perceived sense of lack, because we feel that we don’t fit into existing accounts. The desire to tell your own story, to find one’s place within history or the contemporary, within the archive and its image repertoire, is a natural drive towards the validation of one’s existence, especially for artists working in a space defined or somehow marked by “diaspora,” and affected by themes of displacement, whatever these may be. I believe we resurrect images from the archive to say something about our times, usually informed by a desire or need for them in the present.

Perhaps the key is to see history, or the archive, not as a prison-house of the past—to paraphrase Stuart Hall—but as a space of contemporary relevance, and to reflect carefully about our reasons behind these “resurrections.” Then there are “acts of inscription,” a term I used recently in a transatlantic project in collaboration with my friend and colleague Ruti Talmor. I believe that some of the most profound artworks are born out of this moment when subjectivity meets history, and in the act of inserting oneself into a grand narrative of absence. See Yinka Shonibare’s Effnik for instance—a seminal piece of work Autograph APB commissioned in 1996, and which we recently showcased as part of Black Chronicles II.

Yinka Shonibare, Effnik, 1996. Commissioned by Autograph ABP. Courtesy Autograph ABP

When fitting images into a narrative of the past is not possible, then the creation of a new archive becomes the only viable option, a necessary act. Take Zanele Muholi, for example, one of the most courageous artists of our time, for whom photography is never a luxury, but a necessity. And through this necessity she has created a singular, living photographic archive of African queer, black, lesbian, and non-gender-conforming individuals, with the mission to contribute toward a more democratic and representative national history of post-apartheid South Africa. That visual story did not exist before. It was her art and activism that created it, conjured its space in history, and created both agency and visibility for a community that is perpetually marginalized, and threatened by xenophobic and homophobic violence. Work such as hers forces us to reconsider how histories are written, and to take action in writing our own stories.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Cargo of the Middle Passage, 1989. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: How does Autograph figure into an historical narrative of a black radical presence and national identity?

Mussai: Autograph ABP was founded by a constituency of radical young artists, curators, and activists from African, Caribbean, and Asian backgrounds in late-1980s London. All of them were creative practitioners in their own right, whose work was driven by the desire to “tell their own stories” as diasporic and displaced subjects. At the time, their work was rarely recognized as significant, or seen as relevant, and was largely ignored by mainstream institutions. Yet the founders were deeply instrumental in shaping an emerging black arts movement, whose waves are still palpable today. A perfect example is found in Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Amongst his contemporaries, he was without precedent. His repertoire of tropes and signifiers was too multi-layered to define: black, African, queer, bohemian, political, erotic, spiritual. To claim a hostile space as your own, to write your own narrative in troubling times is always a radical and deeply transgressive gesture. And since the organization’s formation nearly thirty years ago, Autograph ABP has actively engaged in a space of radical visual cultural politics through progressive curatorial work, scholarly discourse, new commissions and publications, education and outreach, and through mining different image archives.

Dawoud Bey, Stuart Hall, London, 1998. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: What is the legacy of the Association of Black Photographers and, in particular, the work of Stuart Hall and cultural studies at Autograph ABP?

Mussai: To answer this question, allow me tell you an anecdote. A few years ago, I went to visit Stuart Hall at his home in Hampstead. It was a Sunday afternoon just before Christmas. We had tea and spoke about my PhD, on which I was about to embark, and I was seeking his advice. As we left, my son, who was about seven years old at the time, said to me, “Mum, this old man is very good with words, isn’t he? I could have listened to him much, much longer.” I’ll never forget that moment, because it was so profoundly moving, funny, and to the point: I’ve never known a person in my lifetime as succinct and eloquent as Stuart Hall. He was influential in so many different fields, and he was also one of the first scholars in Britain to write about photography in relation to cultural difference, race, and representation.

So, Stuart Hall’s critical thinking has been a tremendous source of inspiration and support over the past decades, it and still is. In fact, Autograph was launched in 1988, in his presence, at The Photographers’ Gallery. In those days, the organization was known as the Association of Black Photographers in London. Today the acronym “ABP” points to this legacy, but we no longer refer to ourselves as an “association of black photographers,” and our remit has broadened considerably since. As our chairman for more than seventeen years, from 1991 up until his retirement in 2008, Stuart’s generosity of spirit was fundamental to the 2007 establishment of our home and gallery base in Rivington Place, for which he championed with unparalleled dedication. The continuous impact of his thought is evident in recent installations such as Black Chronicles II, which is dedicated to his memory. His legacy is also preserved by projects such as The Unfinished Conversation, a critically acclaimed three-screen film work by John Akomfrah, commissioned by Autograph in 2013.

Professor Stuart Hall, James Barnor, and Renée Mussai at the opening of James Barnor: Ever Young, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2010. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: How does the recent exhibition Rock Against Racism relate to movements today such as Afro punk or Black Lives Matter?

Mussai: Syd Shelton’s Rock Against Racism (RAR), an exhibition and a book, is one of our most successful recent projects, brilliantly curated by Mark Sealy in collaboration with Carol Tulloch. The project was so successful partly because people could relate to the visual testimony on a personal level, and due to its contemporary relevance. For many people, RAR is a living memory. For others, the collective coming-together of people from all kinds of different cultural and social backgrounds to fight the rise of neo-fascism and racism has a profound resonance in the present.

Syd Shelton, Special fans, Potternewton Park, Leeds, from Rock Against Racism, 1981. Courtesy Autograph ABP

On view concurrently with RAR was a small showcase I curated in the upstairs gallery at Rivington Place, a series of photographs by Bruno Boudjelal that we commissioned a few years ago to mark fifty years of Algerian independence. The exhibition juxtaposed Bruno’s photographs with excerpts from writings by Frantz Fanon, which are displayed on the wall, in vinyl. One of the citations, from The Wretched of The Earth, reads, “When we revolt it’s not for a particular culture. We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.” It only occurred to me retrospectively how very poignant—and potent—these words are when read in relation to the Black Lives Matter campaign, and other current, transatlantic movements.

Rock Against Racism, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2015. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: This question is something that I have been thinking about for a while. When I was younger, a nickname of mine was “black magic.” It has had a profound effect on how I see the world. Do you believe in magic?

Mussai: Yes. I am intrigued by everything remotely supernatural. And as a teenager, I used to think of photographs as magical, transfigured objects. Back then, the darkroom represented this intoxicating and deeply magical space for me, a complete realm of enchantment: the red light, the chemicals, the textures and movement of the liquid in the tray, the uncanny process of giving birth to an image, its transition from the sphere of nothingness into visibility. Photography is rooted in science, of course, but how can that not be utterly magical also? Hannah Arendt has described art as a process of magic, and she located that magic in the artist’s transfiguration of something ordinary into something extraordinary, an expression of the infinite in the finite world of things. I also believe in amorous magic, the Nina Simone “I Put a Spell on You” kind of magic . . . but that’s another story. Apropos names: I never had a nickname, but Renée means “re-born” in French and Melanie, my middle name, derives from the Greek melania, as in dark, or blackness. And I’ve always quietly enjoyed the notion of being called something akin to “the dark one reborn!”

Renée Mussai, 2016. Photograph ©Maliq Mitchell and courtesy of Autograph ABP

Peterson: Growing up in the U.S., everyone had a nickname. “Magic,” for me, has to do with movement and imagination. Everything in the world, everything that can be, is already here, just moving at different speeds in relation to each other. The world, then, can be seen as a theater of images. Some of us can see things coming from outside of the frame before others. The first seers of these images are called magicians. Maybe they just see more of the world, and from a different point of view. In a way, photographers do this all the time.

Mussai: What a wonderful proposition, and so very visual . . . Makes me recall the work of the science fiction horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, and his parallel visual spheres. In the his universe, the creative process is always associated with dreams. Images born in and of dreams are tied to the “delirium” of creation. Magic and its connection to a historical trajectory of reinforcing cultural legitimacy—vampires and witches in popular culture, for instance—hold a particular affinity for me, something about difference and visibility, I presume. Mythical vampires only exist in a transitory realm of the visual: they resist even their own reflection, yet they are forever moving through changing visual stimuli and altered temporalities—through what you so beautifully describe as a “theater of images.”

Peterson: If the world is made of images, how do you see yourself and Autograph with regard to curating images from the past and present, was well as proposing future images for others to look at and read themselves into?

Mussai: Well, I think the first thing we must remember is that we read images from the position of the present and thus these “imaginings” are never stable, or moored within fixed temporalities. And, as such, they require delicate and considerate excavation, when working with contemporary practitioners, or within the archive. What is at stake? Who are we speaking to, and why? Why now? The objective is to create conditions in the present that make it possible for such critical visual dialogues to be fostered between the past and the present, for multiple historical trajectories to be acknowledged, explored, and to create spaces that enable transformative encounters and offer new knowledge.

Raphael Albert, Miss Black & Beautiful Sybil McLean with fellow contestants, Hammersmith Palais, London, 1972. Courtesy Autograph ABP.

Peterson: What photographers are you excited about at the moment?

Mussai: I am always interested in socially-engaged work that addresses the politics of gender, sexuality, or the post-colonial condition: for instance, the work produced by artists such Zanele Muholi or Sammy Baloji, whose new book Suturing The City: Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds, we just published. Currently, I am excited by the work of emerging contemporary artist Aida Silvestri, who deploys innovative and hard-hitting visual strategies to address potent topics such as female genital mutilation or human trafficking. Her solo show Unsterile Clinic is on view at Autograph ABP this summer.

Aida Silvestri: Unsterile Clinic, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2016. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

And I am always open and receptive to what the archive has to offer. At the moment, this means a schizophrenic oscillation between several projects. The basis of our next exhibition, the uncatalogued image archive of the late Raphael Albert, features a vast array of photographs of women in swimsuits posing for black beauty pageants in 1970s London. And then, of course, the ongoing research of Victorian portraiture of black figures in nineteenth-century Britain, as part of the Black Chronicles series, which is the subject a book to be published by Autograph ABP in partnership with Harvard University’s Hutchins Center this fall, as well as our ongoing Missing Chapter archive program, and my associated PhD research. I am excited by work that rebukes any notions of certainties, that operates outside of established regimes of truth, and, instead, opens up new configurations, new ways of seeing.

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, London Stereoscopic Company, 1891 © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Renée Mussai is Curator and Head of Archive at Autograph ABP, and a PhD candidate in Art History at University College London. Victor Peterson II, a writer from Philadelphia and former editorial assistant at Aperture magazine, is currently conducting research in black cultural studies at Kings College, London.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Renée Mussai in Conversation with Victor Peterson II appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 15, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: 3 Reflections on Cinema and Archives

For Aperture’s “Vision & Justice” issue, groundbreaking filmmakers Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young speak about diversity and inclusion in Hollywood in “Black Lives, Silver Screen.” Here, Catherine Gund, Shola Lynch, and Franklin Leonard extend the conversation by reflecting on pioneers of cinema, African American archives, and the definitive films about black life and experience.

Still from An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, 2012, directed by Terence Nance. Courtesy MVMT

Catherine Gund

“Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.” —Frederick Douglass

How could a feature film have changed the world? This is not a hypothetical question. What was possible one hundred years ago, before all that has happened since in the United States, in Hollywood, in our streets, in our minds? What can be seen (and imagined) now? How can we turn witnessing into guiding? Can artistic representation manifest fairness? Can we actually use media to create the world we want to live in?

Still from Lime Kiln Club Field Day Project, 1913, directed by Bert Williams. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art

In 1913, two years before the release of D.W. Griffith’s hideously racist Birth of a Nation, black and white people were making a silent film together starring Bert Williams entitled Lime Kiln Club Field Day. It was never finished, never shown, never seen. Its vision was unrealized, literally and profoundly. But unlabeled canisters full of outtakes—lost for a century—were recently discovered in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art. A thrilling find, a hint, an inspiration, a provocation because it was so unique. Here are everyday pictures of pleasure. Parades and picnics. Boy meets girl, gets girl, kisses girl by the front door. The dailies reveal what was a startling vision, a potential route forward in cinema toward equality, diversity, and justice. Except it was a path not taken. Lime Kiln Club Field Day, instead, remained in darkness, buried under this country’s doctrines of dehumanization, segregation, violence, and a powerful mainstream media machine.

Louisiana-based artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley is exploring that repressed path of social progress, reimagining not only the disappeared parts of Lime Kiln, but also some of the other seventy percent of silent films from that era which are missing, deteriorated, destroyed. Her project American Rhapsody is a series of twelve silent, black-and-white, 35mm films set between the years 1915 and 1926. Each of the films represent experiences in everyday black life against the backdrop of ordinarily extraordinary things like the establishment of the forty-hour work week, the Negro League, the radio, and Daylight Saving Time. I am coproducing this series with Lauren Domino because there is a thin layer of history that can be mined for justice and joy. The three of us are going there, and asking: How do we understand the past? What is media’s power to change the course of history? And how can we consider race differently as we move forward as a society?