Aperture's Blog, page 137

June 8, 2016

John Chiara’s Sidewalk Studio: A Conversation with Allie Haeusslein

Using large-scale cameras he designs and builds himself, John Chiara combines perspective and performance to capture ethereal views of nature and the built environment. His one-of-a-kind prints are distinctive for their materiality and sculptural effects. Chiara, known for images from San Francisco and Los Angeles, spent the last year making photographs in Manhattan and the Hudson River Valley, which were presented together in his recent exhibition, West Side at Tioronda, at Yossi Milo Gallery. Here, Chiara speaks about the challenges of working in New York and how he transformed the iconic city into a boldly colorful, otherworldly landscape.

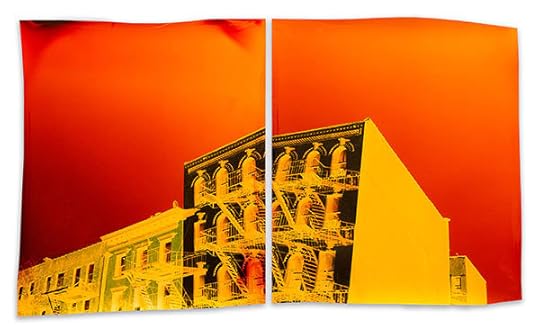

John Chiara, E14th Street at Avenue A, 2015 © the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Allie Haeusslein: Could you describe your process?

John Chiara: I build out the equipment and processes to physically produce the work given those parameters. The equipment and process both revolve around the type of lens and positive, color photographic paper I use. When I’m out shooting, I directly expose the paper, dodge, burn, and filter the light as if I were working in the darkroom. I have been working with this intuitive process for about twenty years now. Often, I work from the inside of a large camera obscura to expose photographic paper up to 50-by-80 inches. I then develop the image using a section of capped PVC pipe filled with chemistry and then roll the tube across the studio floor to process the photograph.

John Chiara, Hudson at Indian Point, 2016 © the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Haeusslein: You mention your large camera obscura, but you also work with cameras of various sizes. What dictates your decisions about what camera to use in a given environment?

Chiara: When I start photographing in a new place, I take time to figure out the right camera to use. For instance, I started photographing Manhattan with a 34-by-28-inch camera; the images feel pulled in because there is no room to step back when working from the street or sidewalk. In this vertical format, these images feel like fragments ripped from the landscape.

I faced many, many logistical challenges photographing in New York with a 34-by-28-inch camera and a 50-by-55-inch camera obscura. When I first started, in June 2015, I was moving the camera around Chelsea on a dolly and using the storage area behind the front desk of Yossi Milo Gallery in New York to unload and reload the large film backs. Working on the sidewalk with large equipment draws a lot of attention. Although there are some benefits to working like this, the process is laborious and makes expanding your photographic terrain difficult.

Several months later, I rented a red Ford F150 and photographed from the bed of the truck. The truck allowed me to drive around looking for photographs to take. I could jump out, take the protective slide out of the film back, adjust the camera in the bed, and then complete the twenty second to three minute exposure. I was fortunate to find My Own Color Lab on West Twenty-Seventh Street, where they allowed me to run prints through their processor so I could review images as I was working. It has been great to become a part of this community and to develop alongside other photographers I admire, like Liz Nelson and Letha Wilson.

To capture what I wanted to photograph while working with a fixed lens at a fixed focal length, from the back of a truck on the streets of New York, I started making vertical and horizontal diptychs. I would take one view of the scene on a sheet of paper, then another view of the scene on a second sheet, to create a staggered effect; after completing several of these diptychs, it occurred to me that I should build a larger format camera. I built a 50-by-30-inch camera, which provided more vertical perspective.

I learn from every picture I take and use what I have learned to develop the work. For me, this way of working is particularly well suited to examining the landscape.

John Chiara, Fulton Street at Church Street, Variation 1, 2016 © the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Haeusslein: Did you have any particularly memorable interactions on the streets of New York as a result of your very visible photographic process?

Chiara: My most memorable interaction was when we took the photograph Fulton Street at Church Street right at the edge of Ground Zero. For some time, I had wanted to make a photograph from the valet zone in front of the Hilton Hotel on the corner. The energy and security is so intense there; you can almost feel it in the air. We had been driving down Fulton Street for weeks trying to figure out exactly where and when I would be able to photograph the area just as the reflection off One World Trade Center would glare directly into the camera’s lens.

There was a huge blizzard in New York back in late January. The Sunday after the blizzard was projected to be sunny, but it was also the coldest day of the year at negative fifteen to negative twenty degrees. I decided this was the day to try to take this picture, thinking the area would be more vacant. At 2PM, we approached Fulton Street at Church Street just as the light was starting to beam off One World Trade Center and, in a stroke of luck, there was an open parking spot in the loading zone near the corner. My assistant, Brett Johnston, and I jumped into the truck bed to remove the slide and then hefted the new 50-by-30-inch-format camera over the truck’s ceiling and aimed it directly at the glare coming off the Freedom Tower. We did this too quickly and were struggling to keep the camera from falling off the truck. As we were doing this, a blinding, god-like light started to flare off One World Trade Center to the West just as a large man started yelling at us from the street to the East, “Hey, what are you doing?” Totally distracted, neither of us answered. As he approached the truck and continued raising his voice, the doorman from the Hilton overheard and came outside, saying “Hey man. It’s a large camera. I bet they are taking some kind of picture.” I fell in love with New York City right then and there.

John Chiara, Market Street at Madison Street, Variation 1, 2016 © the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Haeusslein: Why did you decide to invert the color palette for the photographs made around Manhattan?

Chiara: There are too many reasons to mention them all. When I was contemplating the possibility of photographing in New York, I started experimenting shooting directly onto chromogenic paper on the streets of San Francisco. This process not only physically inverts an image and its colors, but also reverses light and shadow. It creates an image that is profoundly more graphic. Subtle changes in light gradations on architecture become more visible as its saturated negative in the photograph. I believe the negative has subliminal qualities and exposes the underlying properties that make up the landscape.

John Chiara, Embarcadero at Interstate 80, 2013 © the artist and courtesy Pier 24

Haeusslein: Did you focus on particular neighborhoods in Manhattan? If so, what drew you to these locations in particular?

Chiara: I made the decision to photograph in Manhattan because I wanted the work to have an undiluted sense of place. I saw an opportunity to make still images that feel electric, or carry an energy parallel to the kind of chaotic beauty that makes this city what it is. I thought about making images that distilled this essence so a viewer could meditate on this idea.

I usually begin photographing a new place near where the exhibition will take place. This strategy allows me to experiment with technical calibrations while also giving me the time to think about the exhibition space and its surrounding area. The first picture I took, for example, was of the side of the building that houses Yossi Milo Gallery.

Once I got a truck, I started working up and down the West Side. After I got comfortable working there, I was drawn toward the city’s center and started to make work on Park Avenue.

Eventually, another one of my assistants, Josh Olley, helped me find a place near him in Chinatown, under the Manhattan Bridge. Soon after moving, I began to see photographic opportunities right outside the front door and on the adjacent streets. No one seemed bothered as my assistants and I moved large pieces of equipment in and out of the building on a daily basis. My bed basically takes up the whole room, but there is just enough space to unload, load, and store the large film backs and paper.

John Chiara, Delta at 1st, West, 2013 © the artist and courtesy ROSEGALLERY, Santa Monica

Haeusslein: Where are you interested in making pictures next?

Chiara: I want to keep making work here in New York and in California. I would like to keep developing the Mississippi work as well. Someday in the future, I hope to be invited to an artist residency in France, or possibly Italy.

Haeusslein: What about France and Italy do you find particularly intriguing? Have you ever photographed abroad?

Chiara: The only time I photographed across the Atlantic was in 1993. Taking a break from my undergraduate studies, I hefted my Mamiya 330 twin lens and tripod across Europe during a six-month backpacking trip. I did not visit France on that trip, but I did travel through Italy by train. Looking out the window, the landscape resonated with me.

I visited France for the first time this April for my solo exhibition In Camera: American Landscapes at NextLevel Galerie in Paris. My first thought after arriving was, Why haven’t I been coming here all along? After spending some time around Paris, I feel there are opportunities for me to make work in France. I can already envision what I could do in Italy or France. I see a direction to go in.

Allie Haeusslein is the Associate Director at Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco.

The post John Chiara’s Sidewalk Studio: A Conversation with Allie Haeusslein appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Jason Fulford: CHANCE

Photographs by Jason Fulford

Order from Chaos, Surrealist Games, Psychogeography, Impracticality, In Praise of Idleness, Where Function Ends and Play Begins, Dumpster Diving, Keeping It Weird, Photographer as Editor, Scavenger, Author, Comedian, Critic & Wanderer, Maximum Effort for Minimum Result. This and more will be covered in a five-day workshop/seminar with Jason Fulford. Half the time will be spent at Aperture headquarters doing physical and mental exercises, while the other half will be out and about, visiting some of the city’s offbeat repositories of inspiration.

Jason Fulford is a photographer and cofounder of J&L Books. He is a contributing editor to Blind Spot, a frequent lecturer at universities and a 2014 Guggenheim Fellow. Monographs of his work include Sunbird (2000), Crushed (2003), Raising Frogs For $$$ (2006), The Mushroom Collector (2010), and Hotel Oracle (2013). He is coeditor with Gregory Halpern of The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014), and coauthor with Tamara Shopsin of the photography book for children This Equals That (Aperture, 2014).

Tuition: $950 ($855 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Register here

Registration ends on Wednesday, August 10

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Jason Fulford: CHANCE appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision

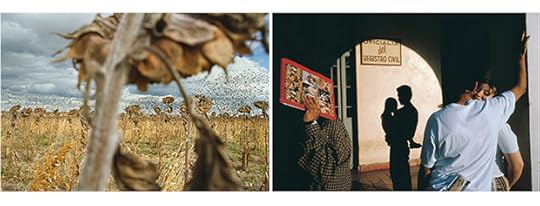

Rebecca Norris Webb, Blackbirds, from My Dakota (left); Alex Webb, Nuevo Laredo, 1996, from La Calle (right)

Do you know where you’re going next with your photography—or where it’s taking you? This intensive weekend workshop will help photographers begin to understand their own distinct way of seeing the world. It will also help photographers figure out their next step photographically, from deepening a unique vision, to discovering and completing a long-term project, to translating a body of work into books and exhibitions. This is a workshop for serious amateurs and professionals alike, taught by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, a creative team that often edits projects and books together, including their collaborative workshop book Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image (Aperture, 2014); Alex’s new monograph, La Calle (Aperture, 2016); and Rebecca’s monograph, My Dakota (2012), which will be reissued this fall.

This weekend workshop will begin with reviews of each participant’s work on Saturday morning, which spark a larger discussion about various photographic issues, including the process of photographing spontaneously and intuitively, how to edit photographs, how to work in cultures different from one’s own, and how long-term projects can evolve into books and exhibitions. The first day will end with a group editing exercise, an an optional photography assignment, and a gallery talk with Alex about his La Calle exhibition at Aperture, which will be open to the public. Sunday will be dedicated to reviewing each participant’s assignment, as well as a series of presentations about bookmaking and exhibitions and will end with an informal Q&A with Alex and Rebecca.

Lunch and light refreshments will be served both days. Participants should notify Aperture staff of any dietary restrictions and/or requirements at education@aperture.org no later than Thursday, September 22.

RELATED EVENT: In addition to the workshop, there will be a joint artists’ talk and book signing on Friday, September 23 beginning at 7:00 p.m., which all the workshop participants are required to attend as some of the material discussed will not be covered during the workshop. This event will be open to the public, however Aperture will reserve seats for workshop participants.

Best known for his vibrant and complex color work, especially from Latin America and the Caribbean, Alex Webb has published fourteen books, including The Suffering of Light (Aperture, 2011), a survey book of his color work, and most recently Memory City (2014, with Rebecca Norris Webb), a meditation about film, time, and the city of Rochester, New York, the longtime home of Kodak, in the year following the company’s bankruptcy. His fifteenth book, La Calle—which features some thirty years of his street photographs from Mexico—will be published in fall 2016 to coincide with the opening of the traveling exhibition of the work at Aperture Foundation in New York on September 7, 2016. Alex has exhibited at museums worldwide including the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the High Museum of Art, Atlanta; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His work is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Guggenheim Museum, New York. Alex became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1979. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, GEO Magazine, and other publications. He has received numerous awards and grants including a Hasselblad Foundation Grant in 1998 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007.

Rebecca Norris Webb has published five photography books, including The Glass Between Us (2006), Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image (Aperture, 2014), and Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (2009, with Alex Webb), the latter exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Originally a poet, Rebecca often interweaves her text and photographs in her books, most notably with My Dakota (2012)—an elegy for her brother who died unexpectedly—with a solo exhibition of the work this past summer at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Her photographs have appeared in the New Yorker, Time, Le Monde, and National Geographic, among other publications, and her work is in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Cleveland Museum of Art; and George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York. This fall, Radius is reissuing My Dakota, which will be launched at Paris Photo, along with an Italian version of the book launched soon after in Rome. This summer, she was one of the guest curators of Documentum’s Pictures & Text issue, along with Teju Cole and Colette LaBouff Speer.

Tuition: $600 ($540 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

PLEASE NOTE: This workshop is for photographers who collaborate with the world, not for those who dramatically alter or change their images digitally.

Register here

Registration ends on Wednesday, September 14

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Shelby Lee Adams: Your Voice in Portrait Lighting

Shelby Lee Adams, Tompkins Sq. Park, 2013 [Aperture Workshop]

“Seeing, connecting, and nurturing love while recalling and sharing more difficult times requires a balanced perspective. It can be tender, or tough and thorny, but all parts are necessary to integrate.”

—Shelby Lee Adams, Salt and Truth (2011)

Join Shelby Lee Adams for a three-day intensive workshop that will explore the psychological, emotional, and technical aspects of portraiture, with special emphasis on photographing people in their environments. Students will learn how to approach people with confidence as well as how to light environments skillfully and with a personal approach. For three days, the workshop students will engage in many scenarios—with assistants, lighting equipment, models, and the instructor—that they can apply to their own photographic pursuits.

On the first day, participants will meet at Aperture where Adams will present slides, share a set of his original exhibition prints and discuss how to develop a rapport with subjects by establishing a collaborative relationship, which aids in producing spontaneous, intimate, and inventive portraits. Adams will also feature slides, explain lighting equipment as well as the blending of diverse light sources, the histogram, color balance, and lighting ratios. The afternoon will be a continuation of the morning presentations with reserved time for reviewing students’ portfolios.

The second day will be spent on location. Students will meet at Tompkins Square Park with their cameras. The class will divide into three smaller groups, each with a teaching assistant and a professional light kit. There will be a few models provided; however, students will be encouraged to approach people within the park and invite them to participate. Lunches will be purchased (at student expense) within the local area, so that participants will have maximum time to photograph.

For the final meeting, participants will meet at Aperture, where the morning will be spent preparing images in an open lab environment with the instructor and assistants providing guidance and feedback. After lunch, students will present the works they created the day previous. Adams will lead a group discussion about each student’s images. Participants will be encouraged to talk openly about their experiences and to discuss the successes and the difficulties of creating unique portraits outside of a standard photography studio setting. Students may also show work from their portfolios that they may not have shared on the first day.

Participants are required to provide their own digital camera and laptop with photo editing software, as well as a portfolio of approximately fifteen images. Prints are preferred; however, students can also present digital files. Lunch and light refreshments will be provided on the first and last days of the workshop (Saturday, October 8 and Monday, October 10). Participants should notify Aperture staff of any dietary restrictions and/or requirements at education@aperture.org no later than Thursday, October 6.

Shelby Lee Adams was born in Hazard, Kentucky, in 1950, and educated at the Cleveland Institute of Art and Massachusetts College of Art. He received a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 2010 and is the author of four photography books: Appalachian Portraits (1993), Appalachian Legacy (1998), Appalachian Lives (2003), and Salt and Truth (2011). His work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, Polaroid Corporation, Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation, and Peter S. Reed Foundation. His photographs are in over sixty national and international collections, including the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. His work has appeared in such publications as Aperture, Smithsonian Magazine, the New York Times, Mother Jones, and Black and White magazine. He divides his time between the Berkshire Mountains and eastern Kentucky.

Tuition: $750 ($675 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Register here

Registration ends on Wednesday, September 28

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Shelby Lee Adams: Your Voice in Portrait Lighting appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 6, 2016

Vision & Justice: Ingrid Monson on Roy DeCarava

Collectors: The Jazz Musicians

For the “Vision & Justice” issue of Aperture, Wynton Marsalis, Ingrid Monson, Alicia Hall Moran, Jason Moran, and Somi reflect on photographs that represent moments in their lives. Here, Monson responds to Roy DeCarava’s Oliver Beener Group #13.

Roy DeCarava, Oliver Beener Group #13, 1956 © Estate of Roy DeCarava

Trumpeter Oliver Beener’s quartet silhouetted from behind, looking out into a smoky room (perhaps the Club 845 or Blue Morocco in the Bronx), captures, for me, the preeminence of the rhythm section in jazz. The trumpeter held up by the pulsating collaboration between the bass, drums, and piano taking place behind him. The Victorian ceiling refracting the harsh club lighting, glaring at the drummer and through the piano bench, making the snare stand, bottom of the hi-hat, and piano panel unusually visible. We see the musicians’ point of view, accelerated by the receding lines of the tin ceiling, pulling us into their world, their responsibilities, their teamwork, their joy. A woman and a fedoraed man look up, hearing intently.

Ingrid Monson is the Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music at Harvard University.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice: Ingrid Monson on Roy DeCarava appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

From Magnum Photographers, 10 Decisive Moments

For five days only, prints by Magnum photographers which respond to the meaning of the decisive moment, will be available to buy as signed, museum quality, 6×6” square prints, exceptionally priced at just $100. By using this link to make your purchase, a proceed from each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

The timing had to be perfect. A swimmer is caught in a midair plunge from a rusted boat. A young ballerina looks ready to fly above the New York skyline. A man steps, with sublime elegance, into three columns of light. Celebrated for “the decisive moment,” the harmonic composition of form, style, and frame, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs are among the most influential in the recent history of photography. For photographers associated with Magnum Photos, the influential agency Cartier-Bresson cofounded in 1947, pursuing the decisive moment has produced endless variations on a classic theme. This month, Magnum’s Square Sale, online now through June 10, is a collective portrait of events personal or political, displaying the astounding vision of international photographers who, from the 1950s to today, who have redefined what it means to stop time on film. Here is a preview, in the words of the photographers themselves.

Jim Goldberg, 6PM, Kiev Ukraine, 2006, from the series Open See

Jim Goldberg

“Wandering Kiev with my 4×5, I saw this woman of the streets readily posing for my camera. For a split second, the light, soft smoke and her pose evoked a different reality from the one she lived in.” — Jim Goldberg

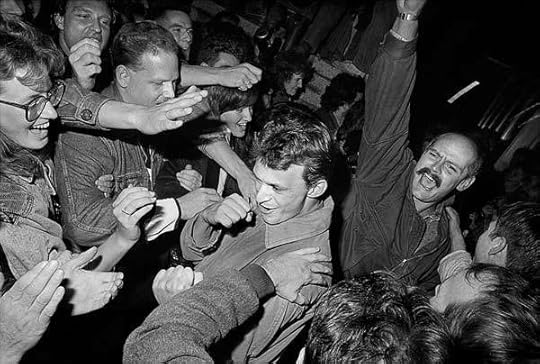

Mark Power, Berlin, Germany November 9th/10th 1989

Mark Power

“By a series of fortunate events I found myself in Berlin on the night the Wall (unexpectedly) opened. The story of how I came to be there at all is a long one, but fate dealt her cards and I was lucky. The moment was decisive historically, of course, and one of those all-too-rare occasions when a momentous event is joyful rather than tragic.” — Mark Power

Jonas Bendiksen, Abkhazia, Sukhum, 2005

Jonas Bendiksen

“I took this image at the Black Sea beachfront in the city of Sukhumi in the unrecognized republic of Abkhazia. Tourists and locals were hanging out picnicking and bathing. When people are hurling themselves from old shipwrecks I don’t necessarily think, ‘Oh, here is a decisive moment’. . . Some are complicated, where lots of elements come together; some are simple low-hanging fruit; some are long, drawn-out sluggish affairs; others are over in a split second. Whatever it is, the shutter had better be open at the right time.” — Jonas Bendiksen

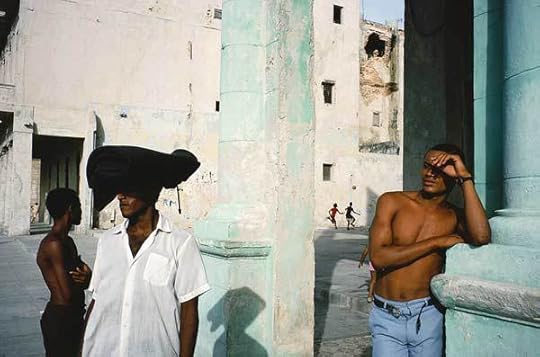

Alex Webb, Havana, 1993

Alex Webb

“There are many photographs of mine that have “taken” me. I chose Havana, 1993 because Cuba, then, seemed suspended in time, echoing the feel of the Spanish streets in the 1930s that Cartier-Bresson photographed so memorably. I suspect that the Cartier-Bresson I knew would have been skeptical of the color of this homage to him—but I’d like to think his younger, surrealistic self would have at least appreciated the two boys in the background with that soccer ball hovering overhead, out of reach forever.” — Alex Webb

Jacob Aue Sobol, from Arrivals and Departures, 2012

Jacob Aue Sobol

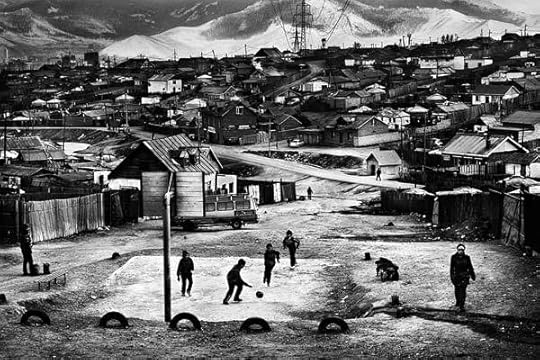

“The sun’s setting as I sit down on a bench and close my eyes. A group of boys pass me with a basketball. I decide to follow—I have to get back on my feet. They run through the narrow alleys and into an open space on top of a hill. This is the basketball court. I forget about photographing, but start playing with the boys. Then, on my way home, I walk to the hilltop, and as I turn around I see it all come together. The boys playing, their homes and the mountains. A moment I want to keep and remember.” — Jacob Aue Sobol

Matt Black, Syracuse, New York, 2015

Matt Black

“To me, the act of observing is what makes a moment decisive. It’s not a moment until it is seen and recorded. What is interesting to me is what happens internally that leads to that instant of clarity. A decisive image stops movement, but it also preserves thought.” — Matt Black

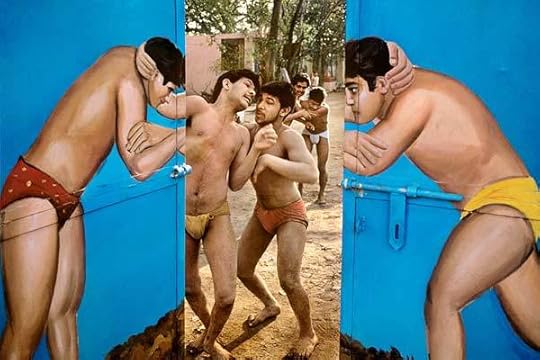

Raghu Rai, Wrestlers in Akhara, Delhi, 1988

Raghu Rai

“I shot this image in 1988 when I was doing my second book on Delhi. While driving past, I saw the main door of a wresting complex (Akhara) garishly painted with two guys in a dramatic wresting posture. I stopped and as I pushed the door open this is what was going on inside. I stayed on the spot and shot a few frames where the inside and outside human body shapes came into certain relationships, thanked them, shut the door and came back.” —Raghu Rai

Alessandra Sanguinetti, New Year, Buenos Aires, 2005

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“I like to stay long enough in one place or situation to watch the scene unfold, either because of my presence or in spite of it, lingering until it all slows down enough so I can contemplate and be aware of moments that would otherwise go by unnoticed. This portrait of Belinda was taken on a drowsy New Year’s Day morning.” — Alessandra Sanguinetti

Eli Reed, Tyra Banks and John Singleton, 1994

Eli Reed

“Tyra is what I think of as a generous, intelligent, and sensitive human being, as well as being a beautiful woman, and John is an impassioned artist filmmaker, who is a brilliant writer, connected with the world he lives in. I wanted to capture an image of the two’s feelings for each other at that particular point. Tyra briefly closed her eyes and the moment was there.” — Eli Reed

Carolyn Drake, Wellington, Florida, 2005

Carolyn Drake

“This image recalls a moment in my own life; it puts me in the shoes of myself before I moved abroad in my thirties, just starting my career as a photographer, so is this how I saw the US back then? Having returned to make new images after almost a decade away, it begs me to consider how I’ve changed, how my perceptions of this country have changed, and how image-making has changed. This is one of the few early images of mine that have stayed with me over time.” — Carolyn Drake

All images © the artist/MAGNUM Photos

Support Aperture today through the Magnum Square Print Sale, open online June 6–10, 2016.

The post From Magnum Photographers, 10 Decisive Moments appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 3, 2016

Vision & Justice: Awol Erizku

A young photographer finds inspiration in Old Masters and Afropunk.

By Steven Nelson

Awol Erizku, Girl with a Bamboo Earring, 2009. Courtesy the artist

Awol Erizku, born in Ethiopia, raised in the Bronx, and based in Los Angeles, effortlessly moves among photography, painting, sculpture, installation, and video. He also has a very active presence on social media, and with little notice one might catch an array of new images on Tumblr or a quick exhibition on Instagram. In 2009, he replaced Johannes Vermeer’s white girl wearing a pearl earring with a black one sporting bamboo. He substituted Leonardo da Vinci’s white lady cradling an ermine with a black woman embracing a pit bull. Exacting in pose and in detail, these images focus on the black body and its relationship to Western painting. These portraits, which force us to look at the work of the Old Masters through a black, diasporic lens, challenge Western art history’s almost blinding whiteness. Erizku’s strategy lays bare the act of seeing as culturally contingent and, more to the point, racially informed. His concerns fit quite neatly into a trajectory of African and Afro-Atlantic artists such as Robert Colescott, Renee Cox, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Faith Ringgold, Yinka Shonibare, and Kehinde Wiley, who have explicitly used Western painting as the foundation for reimagining black subjectivity and the complicated workings of race in representation. At the same time, like Nina Katchadourian’s Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style (2010), Girl with a Bamboo Earring and Boy with the Red Turban, which satirically references Orientalism, are also roguish and fun.

Awol Erizku, Edfu, 2014. Courtesy the artist

While the work of the Old Masters serves as fodder for Erizku’s formal, political, and intellectual interventions, it also confirms for him the importance of fashion in portraiture. Whether northern or southern, whether by Vermeer or da Vinci, style and dress were considered to be as important as composition, gesture, and pose in relaying the high social status of sitters. Erizku combines the lessons of the Old Masters with sensibilities from two mentors: the formal exactitude of Lorna Simpson’s “archival” portraits and the sensual, often humorous theatricality of David LaChapelle’s photographic spectacles. Erizku’s images are far less statements about fixed black identities than they are analyses of subjects under construction.

In 2014, the artist created a series of portraits for Vogue of attendees at the tenth annual Afropunk Fest, held in Brooklyn’s Commodore Barry Park. Ostensibly an exploration of black hair, the resulting images exult in the gap between portrait and mug shot. In this liminal space, Erizku deconstructs and reconstructs; he testifies and signifies; he profiles and represents; and, to borrow from Henry Louis Gates, Jr., he serves us race and explores the difference it makes.

Awol Erizku, Untitled Heads (Dope), 2013. Courtesy the artist

Erizku’s portraits exist as wry exegeses on profiling, which, in African American contexts, can be read numerous ways. As a tool of the state, it supports and continually reinforces a norm of black stereotyping that upholds myths of black social and cultural inferiority and criminality, sustains the right of law enforcement and vigilantes to murder unarmed black men and women with impunity, insists that those slaughtered deserved what they got, and makes necessary movements like #BlackLivesMatter. Profiling as seen in Erizku’s portraits is also the ancestor of vogueing. It’s a black sartorial snap: Walking into a room and owning it, knowing you look fierce. Taking for granted that the world is your runway and onlookers had better move aside and take their tired, stereotypical bullshit with them. And profiling is a photographer’s tool—Erizku is profiling sitters engaged in profiling.

His fabulous, self-possessed sitters resist any negative meaning. They will not be categorized or terrorized. In making these photographs, in playing with multiple levels of identity, Erizku, like the band Funkadelic, exhorts, “Free your mind and your ass will follow.”

Steven Nelson is Director of the African Studies Center and Professor of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice: Awol Erizku appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 2, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Jamel Shabazz in Conversation with Michaela Angela Davis

“Well before there was Kehinde Wiley, there was Jamel Shabazz and his New York street portraiture of subjects framed by regalia of their own making,” Khalil Gibran Muhammad writes of the legendary street photographer in Aperture’s “Vision & Justice” issue. “His lens has always seen more joy, more life, more blackness than our own eyes are capable of.” Renowned for capturing the styles and poses of New York in the early 1980s, Shabazz’s photographs, collected in Back in the Days (2001), A Time Before Crack (2005), and several other recent books and exhibitions, are indelible records of African American life, as rich with humanity as the portraits of James VanDerZee and Gordon Parks. Here, Shabazz speaks with the image activist, CNN commentator, and former fashion and beauty editor for Essence magazine, Michaela Angela Davis, about the origins of his photography and the impulse to record African American communities, from the dawn of hip-hop to today.

Jamel Shabazz, Grand Master, Harlem, New York, 2010. Courtesy the artist

Michaela Angela Davis: When did you first start taking pictures?

Jamel Shabazz: I started taking pictures in 1975. My first subjects were primarily close friends and fellow junior high school classmates. Prior to that, as a young child, given that my father was a photographer, I was always surrounded by images, and I saw the beauty of photography.

Davis: You say you saw the beauty of photography. When did you discover the beauty of black people? When I pore over your images, I find they all are like love letters to us, to black people, to black youth. Can you remember learning or knowing that you loved these people, or that you loved us?

Shabazz: Oh, no doubt about that! My discovery came by way of viewing the countless family photo albums we had prominently displayed in our home. I was in my single digits at the time, but I saw beautiful black and white photographs of my immediate family in pages of well-organized albums, many going back into the early 1900s. There were images of love, struggle, and dignity and it was within the pages of these albums that my love for my people was born.

Around this same time, my father had this very unique book, Black in White America (1968) by Leonard Freed, which would become a fixture on our coffee table. That one book provided me with a broader view of black people outside of my local community. I not only saw intriguing images of black people, but I also got the chance to read many stories of injustice and fortitude. Black in White America was instrumental in helping me better understand the climate of America at the time, as the civil rights movement was on the rise in the midst of racial and social unrest. I can honestly say that Freed’s book changed my life, inspired my vision and love for my people. It also helped me to better understand my higher calling in life, which is to continue to document our history and culture in hopes that young people can draw inspiration from my work.

Jamel Shabazz, School Days, Brooklyn, 1981. Courtesy the artist

Davis: There’s a very particular sensibility that you had in looking at black youth at the time, in the 1970s and ’80s. I feel like you were doing, you know, Black Lives Matter through photography in a time when we didn’t even have that language. You were looking at the people that no one else was looking at, and photographing them in a way that had dignity and importance, and assuming that someday this would matter. Was that your goal? Can you remember what your initial hunger was to take photographs of the people in your high school or in your neighborhood?

Shabazz: My main goal for making images during my high school years was just to have a greater sense of purpose. At the time, many of my friends were up and coming graffiti artists and were making names for themselves in the neighborhood and outer boroughs. I did partake in that particular art form, but I found photography more direct and personal. Photography allowed me an opportunity to engage and interact with folks that were often deemed invisible or irrelevant.

I discovered my real hunger for making images while I was stationed in West Germany in the late 1970s. It was there that I realized how impactful photographs are, on me directly. To military personnel stationed overseas, letters and photographs are vital to one’s wellbeing, especially as we had to contend with a lot of hardships and thoughts of being away from home. Photographs I brought over with me that I had made just a couple of years earlier, of my junior and senior high school friends, provoked good memories and helped me maintain my sanity in an environment that did not have a lot of people of color. In Germany, I promised myself that when I returned home I would carry my camera everywhere I go, so I would never be without memories.

Jamel Shabazz, The Ranks, Chicago, Illinois, 1997. Courtesy the artist

Davis: What were those images that kept you sane?

Shabazz: They were mostly pictures of family, junior and senior high school friends, and of course my girlfriends. In the States, the photos were important, but when I went overseas they took on a whole new form. I was not only looking at the individuals in the photographs, but every aspect of the photos, from various styles to the environments in which they were made. When I would go out in the field on exercises, I would actually bring my small portfolios of 4-by-6 inch prints to help suppress the homesickness that I would feel from being away. Those few images allowed me to see the magical power of photographs and having memories.

Upon returning home, during the summer of 1980, my camera became the compass and the magnet that allowed me to both connect and reconnect with a lot of young people. During the fall of that year, I returned to my high school now more idealistic, mature, and concerned with the wellbeing of the younger generation and the mounting tension that was so present in both the school and local community. I realized that I had to lend my voice, and talk about the idea of “nation time” and nation building. This would be a challenge. Guns and drugs were gaining a strong presence and a number of young men were being led astray. I started talking to the youth at every opportunity. One of my main statements was “I see your greatness, young brother. I’m a photographer, and would you mind me capturing your legacy?” That was a practice that broke down many barriers and created a way in. Once they agreed, I would train my lens on them while composing the frame; I would speak to them about the need to love one another, and to be mindful of the pitfalls and obstacles that they could face, and I often used my own life as an example.

Jamel Shabazz, Remembering Malcolm, Harlem, New York, 2008. Courtesy the artist

Davis: You said that? You would literally say, “I see your greatness, my young brother, and I would be honored to let me capture your legacy.”

Shabazz: Yes, for the most part those were my words. It was always about recognizing the greatness, the warrior spirits, and the beauty within. I realized that I had a voice, not only to capture the image, but more importantly to plant the seed of positivity in their minds. What I wanted to do was allow these brothers and sisters to know that I see you for who you are. I used the word “warrior spirit” with many of the young men coming up because they were the ones that were often challenged and searching to be recognized, and I noticed that particular reference made the brother feel good. It made him feel visible. But what was more important for me was to engage young people to help eradicate some of the violence that was going on. I also realized that I had the ability as a mediator to actually go amongst them and end a lot of tension between warring factions.

Davis: So you were clear that you were disrupting the violence. The camera was there, the thing that got them to hold still, which I think is very powerful—not just to hold still in the photographic, clinical kind of model term, but to hold still in the midst of all this chaos and connect with them human-to-human, spirit-to-spirit, brother-to-brother, to let their spirit hold still for a second because, you know, they were in this war zone. So you saw yourself as someone who was coming to interrupt the violence. Did you see a shift in them, like, when you would look at them with respect, or look at them lovingly?

Shabazz: No doubt about it, sister. I was very clear on what I needed to do to counter the escalating violence. Because one thing I learned in the military was the spirit of brotherly love. When I came home, I wanted to pass on that torch. Recognizing their greatness and their beauty produced a connection and sense of acceptance. Interestingly enough, one of the things I would pass on to both males and females who I really bonded with was the “DAP,” which was a popular handshake that we did in the Army meaning, “Dignity and Pride.” Once we had that DAP connection, a lasting bound was established.

Davis: I never knew that’s what “DAP” meant.

Shabazz: Yes, “Dignity and Pride”! That originated from brothers during the Vietnam War. We would extend our right hand in a fist and each participant would have an opportunity to be on top (showing one is not over the other), then the fists would join in the center (symbolizing equality), and finally the fists were pressed against the heart (showing love and sincerity). For many of us, it was a starting point for creating love and unity.

Jamel Shabazz, We Must Be Brothers, Harlem, New York, 1997. Courtesy the artist

Davis: With all of that as your intention, you were able to capture—and I’m going to use this word “swag” now—this incredible sense of style. You recorded for all of us now, forever, the ingenuity, the intelligence, the genius, the diversity of black youth style, even in the midst of this war zone. You saw the style in them as a creative expression, and that could also be something that was self-esteem-building. Or at least that’s what I see. Where did style play into it?

Shabazz: With all honesty, having style back in the 1970s and ’80s was common. That was a way of life where I come from. In Brooklyn, in particular, in my community—East Flatbush, Red Hook—everyone was stylish. Looking back now, I was drawn to those people who had a particular style. The person who was unable to afford the latest fashion trends, or lacked “swag,” could feel rejected and alienated, so oftentimes I would invite them to be photographed. Back in the days, people did not have a lot, but they took what they had and made it work. Back then you had to have a crease in your pants! You may not have brand new sneakers, but you kept a toothbrush in your pocket to brush away any dirt that would alter the newness. Colors were coordinated and a fresh haircut was almost mandatory. For the women of my generation, the majority of them wore dress shoes to school, and if you had sneakers, in many cases you had them in your bag, only wearing them for gym, or track. Fashion trends are so ever present in much of my earlier photographs, but for me, my point of interest was grounded more in seeing the heart and souls of the men and women that stood before me. That was the real swag!

Jamel Shabazz, Cultured and Refined, New York, 2005. Courtesy the artist

Davis: When you don’t come from that community, where you didn’t see style no matter what, there’s a part of it that helps to illustrate that warrior spirit. Meaning there is something that did not get destroyed in all of this. For me, it connects us to our heritage. You go to any country on the African continent, any tribe, you see an expression of God, of creativity, through the way that we present, whether it’s hair or fabrics or jewelry or dressing. I feel like what you were able to record was this inevitable, indestructible response, that we’re still able to present ourselves in this way that is exciting and interesting and full of pride. So I don’t see it as a surface thing at all. I feel it is proof of some power that we have still, this idea of these are people that nobody’s checking for, there were no street style mavens or whatever looking at them, and still they were fresher than most.

Shabazz: Yes, that is a great analysis and I agree with you one hundred per cent.

Davis: You have that as history. You have proof! It was proof of who this black youth was. They were pushing through. They were here. Were you able to show folks after you photographed them that they were in a book? Did that shift anything, for them to see themselves as you saw them?

Shabazz: The proof is in the photographs. I saw so much potential and possibility in our youth until the crack and AIDS epidemics came and life as we knew it gradually changed. Communities were losing their youth, both through incarceration and premature death. Families were falling apart and homes were being lost. My work then became an official record on how life used to be. I was fortunate to be able to document so many people at the high point of their lives; my images would also later on serve as reminders, of a different day and time; a period I refer to as “a time before crack.”

There seems to be a great appreciation for the photographs I made and they brought joy to everyone who happened to see his or her portrait. Over thirty years have now passed and I am still learning about the people I photographed. Many are not here today, but with my books, their legacy lives on. For those that have survived, the images and stories are now passed on to their children.

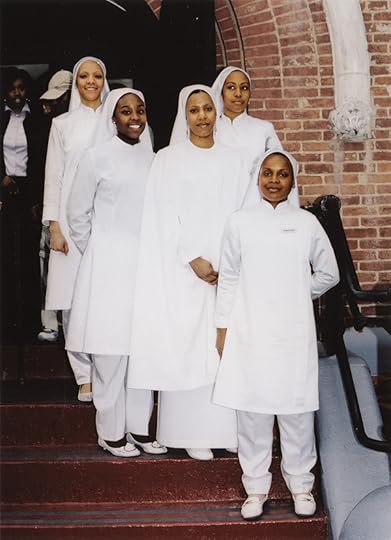

Jamel Shabazz, Muslim Girls Training and General Civilization Class, Harlem, New York, 2010. Courtesy the artist

Davis: The community responded in a particular way. What about the industry? In the late ’80s and ’90s, the whole photography scene, or the art scene in photography, was very closed. It was elite. There are very few brothers who were prominent. What has that experience been like? What was that like, being a conscious black artist?

Shabazz: I was fortunate to work with a number of magazines in the late 1990s—TRACE, The Source, and Vibe. It was really TRACE magazine that recognized my work early on, and I’m very grateful to Claude Grunitzky who was the founder and editor of that great publication, for seeing value in my photographs and inviting me to share my images with his publication. It was via TRACE that my work garnered both national and international recognition, aiding in propelling my career. During that time, I only knew of a handful of African American photographers besides the great Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava. There was Barron Claiborne and Mark Baptist, who were two of the top fashion photographers whose worked I would see often in the pages of various fashion and lifestyle publications, which I held with high regard. Later, I would go on to meet Barron, who I consider a very conscious practitioner of the craft, and it was through his guidance and personal experiences that I became aware of the politics and the ins and outs of the industry. I took in his advice and I moved forward with great zeal and self-awareness.

I remember going to The Source one day with no appointment. I met Eric Russ, an assistant photo editor for the magazine, who happened be in the elevator. He saw me with my portfolio and said, “What do you have there?” I showed him work that I was making back in the day, and he said, “Brother, this is right on time. We’re working on our 100th issue, and would like to have some of these images featured.” I was elated! About fifteen of my photographs from the 1980s were selected. When that 100th issue came out, I was told that issue sold out all over New York City. People wanted to have it, because it featured many people who were respected in the black community, not necessarily hip-hop artists, but everyday people who were known in New York City. That’s when it occurred to me that I may have something special and unique. With the success of The Source feature, I decided that it was now time to publish a book. I had previously read an article about this new publishing company in New York, PowerHouse Books, which happened to be in the area. So in the case with The Source, I went to Powerhouse with a portfolio of 1980s photographs, without an appointment. To my surprise, I was able to get an audience with the co-founder, Craig Cohen, who upon seeing my work, told me, “This is what we have been looking for. Your book can be out by next year.” He honored his word and Back in the Days was introduced to the world in September 2001.

As a conscious black artist, I now had a voice and opportunity to create what I have been blessed to do and thereby contribute to the annals of history. I revisited the work and writings of Gordon Parks to better understand how to navigate in this new and uncharted area. Gordon had many challenges, but he persevered and let his work speak for itself. I was determined to create images that represented various aspects of communities and people that are often not properly represented or included in the larger narrative. Today like never before, I feel a great sense of urgency to be out on the front lines addressing issues that we face not only as a people, but also as a global community. As a child born in the 1960s, the images that fed my mind were of brutal wars and injustice, and today, in 2016, those same problems still exist. The difference between then and now is that I was not old enough to lend my voice during the antiwar protests during the Vietnam era, nor the numerous protests demanding freedom, justice, and equality, but today I can.

Jamel Shabazz, In The Zone, East Rutheford, New Jersey, 2009. Courtesy the artist

Davis: A lot of the children we see now, the young adults who seem so troubled, and who everyone is so afraid of, they are the fallout of that time. What’s your vision now? And what is your hope for this nation? And what have you really seen that has changed?

Shabazz: Wow! What a powerful question right there. In terms of hope, Kendrick Lamar’s performance at the Grammys this year comes to mind. That really touched me!

Davis: Me, too.

Shabazz: It made me feel good to know that this young brother has risen up from the ashes, making such profound statements about the state of America and its laws that have incarcerated generations of its people. I can’t help but to think about those sixteen accomplished black women from West Point who dared to raise their fists as a sign of solidarity and celebration, only to be mocked and persecuted for having confidence and pride. It’s a change. It’s something I needed to see.

There so much work that needs to be done to reverse many of the problems we are faced with today. The topic of mass incarceration is serious; the overall criminal justice system has to be revamped. More often than not, I am reminded of the countless imprisoned men of color who are being exonerated due to the utilization of DNA samples. So many have spent decades locked up and thousands still languish behind bars due to disparities and covert racism. Witnessing the crack epidemic and the unfair laws that contributed to the dismantling of communities and mass incarceration, far too many people just needed rehabilitation versus incarceration. Sadly, the damage has already been done and lives and families have forever been changed. I really can’t predict what the future will hold, as right now the world is in turmoil and much will be determined by who the next president of this country will be. I do know one thing: they have a great task ahead of them.

Jamel Shabazz, Best Friends, Brooklyn, 1980. Courtesy the artist

Davis: You did this work before Instagram, before Facebook, before the age of social media, when now we’re able to exchange images across the globe in a matter of seconds. But for all the people who are recording these times, you represent that they are connected to a legacy of people caring about recording our lives. But that this is an integral part of the legacy. And particularly the crack epidemic—very few people have talked about it in pictures, whether moving pictures or not. What literally happened. Because people look at a lot of black youth now as if, “What is wrong with them?” And it’s not what’s wrong with them. It’s like, “What happened to them?” Your images create the conversation of “What happened to them?” That is a burden. The fact that you’re not just like Vice and droppin’ down, and taking pictures of cool black people. You have touched them and talked to them and know them, and now that you know what happened to them, that’s a whole other layer to this movement. It’s really important that you’re here.

Shabazz: Well, I thank you so much for that and it’s very important that you’re here, as well as so many other visionaries who lend their voices. I personally stand on the shoulders of the many who have sacrificed so much, and that is how I can even be having this exchange with you.

Davis: We are our stories. That’s what proves that a people were here. If someone young happened to get “Vision & Justice,” this very lovely magazine, a young black person, what would you want to say to them directly?

Shabazz: I would say that we have a very important history, it must never be forgotten, and at the same time, all of us individually have the ability to be creative and proactive in some form or fashion. Let us search inside ourselves and see what we can do to contribute to the preservation of our history and culture. We can start with our own families. It is vital that we take time to have conversations with the elders within our immediate families and communities, because they hold the keys to a very important history.

A wise man once said, “You can’t know where you’re going, until you know where you’ve been.” I wasn’t aware of the importance of exchanging thoughts with my aunts and uncles back in the ’60s and the ’70s. They’re gone now and so much went with them, but this generation, born in the age of Facebook and other forms of social media, have an abundance of tools readily available to not only record history, but also to inspire and enlighten others on a global stage. With the world being in such disarray, we need all hands on deck.

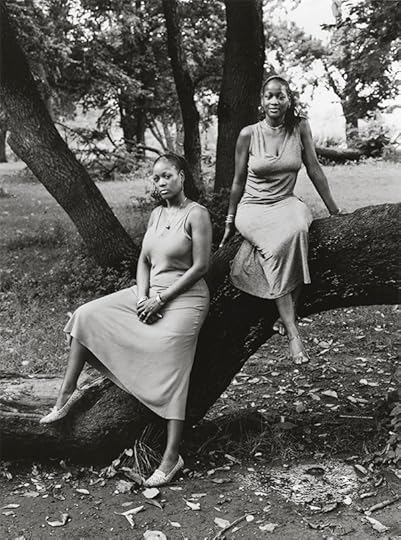

Jamel Shabazz, Sisters, Brooklyn, New York, 2003. Courtesy the artist

Davis: That is perfect advice. I needed to hear that. Thank you so much. You’re so inspiring. I’m glad I’m living in a time with you in it.

Shabazz: That means a lot because you’ve been an inspiration to me over many, many years and I look back at your work when I first was introduced to it in Essence and Vibe. You were a master stylist and that helped me be the man I am today. You also helped me to appreciate womanhood. As I said to you in an earlier conversation, seeing you on TV and raising your voice, you have made great contributions that inspired me over the years! So I salute you for what you’ve done and what you will continue to do, because I see you as a serious torch bearer, both now and for the future generations.

Davis: Well, we’re out here together.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Jamel Shabazz in Conversation with Michaela Angela Davis appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 31, 2016

Vision & Justice: Wynton Marsalis on Frank Stewart

Collectors: The Jazz Musicians

For the “Vision & Justice” issue of Aperture, Wynton Marsalis, Ingrid Monson, Alicia Hall Moran, Jason Moran, and Somi reflect on photographs that represent moments in their lives. Here, Marsalis responds to Frank Stewart’s Calling the Indians Out.

Frank Stewart, Calling the Indians Out, 1976. Courtesy the artist

As dreams of previous generations erode, there is nothing more uplifting than the clear vision of a veteran free of bitterness. That’s why I love the work of Frank Stewart. His vigilant eye is trained on counternarrative realities that run deeper than race, gender, class, or even oppression itself.

Frank loves black folks, but he focuses on timeless HUMAN fundamentals that only increase in value and intensity with time. He is a jazzman with a camera. Improvisational, empathetic, and accurate, all kinds of folks trust him and let him in.

In the New Orleans of my youth, if someone agreed with you they would say, “I hear you.” If it was deeper than that, they would say, “I FEEL you.” When I look at this photo, I’m there with ’em, can feel ’em bringing that spirit down, still.

The picture is titled Calling the Indians Out. That means to proclaim your identity, to evoke ancestors, to prepare the way for the Big Chief on Mardi Gras Day, and above all else to combat the demons of life with a razor-sharp artistry. And here they are on a typical Crescent City street beating out that three-beat rhythm on those tambourines. Everybody chanting “Two Way Pocky Way,” and then each takes a turn inventing some rhymed couplets, a communal art as old as Dan Tucker. I come from the bottom of the Lower 9, look the devil in his face and say I don’t mind dyin’. Here they are gathered in that unforced circle, and they clap and dance … and I bet somebody we don’t see is hitting a cowbell or drum. And I hope you’re not in a hurry, because we’re gonna be here until it feels right. Ain’t nobody in a hurry.

If you’ve had a bad time for a few centuries, having a great time for a few hours could easily be a matter of life or death.

Wynton Marsalis is a trumpeter, composer, teacher, music educator, and Artistic and Managing Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice: Wynton Marsalis on Frank Stewart appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 26, 2016

The Garden of Virtual Beauty: A Conversation with Karine Laval

Vivid colors and florid imagery are just the surface of Karine Laval’s new series, Heterotopia. But the surface is important, too. With their glossy finishes, her photographs and sculptural installations create a luscious fantasy world. In her new exhibition, Artificial by Nature, Laval investigates senses of space, identity, and perception. Here, she speaks about the lure of artificial environments, Monet’s Water Lilies, and how her childhood in France—and travels abroad—have influenced everything from her choice of medium to her vibrant palette.

Karine Laval, Untitled 45, from the series Heterotopia, 2014

Annika Klein: You lived in Algeria as a young person, as well as in the Caribbean. Has that experience informed your fascination with color?

Karine Laval: Yes, I think so. My upbringing and traveling, spending time in different—and what are perceived as very exotic—places has influenced my work. My whole family had a life of travel, particularly on my dad’s side. He grew up in several countries in Africa—Gabon, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Morocco, and Algeria—and moved around from one country to another every couple of years. The first time I went to Martinique I was six years old. My grandparents had moved there from Africa. One year, my parents sent my sister and me to spend the summer with our grandparents. They put us on the plane alone! We were probably among the first kids traveling trans-Atlantic by air on their own back then! Although I was young, I can still see my grandparents, behind the glass doors at the airport. I could already see the strong presence of nature outside, and I remember coming out of this airport and feeling that warmth taking me and enveloping me, the humidity of the tropics. Those lush green trees immediately surrounded us. I’m certain my sense of color and interest in the landscape in general have been inspired by those tropical landscapes.

Karine Laval, Poolscape #58 (Fire Island, New York), 2010

Klein: Your new body of work appears linked to the experience of these landscapes, but not as a literal representation. Is Impressionism also an influence?

Laval: Growing up in France, Monet is part of our culture. In his Water Lilies series, Monet began to deconstruct the image by veering toward abstraction. His paintings became more about light, color, and texture. For over ten years, my work has been inspired by and centered on water. I have even used water in the image-making process as an additional lens of the camera. In my Poolscapes series (2009–2012), I shot from above the surface of the water, which means you can see reflections of what’s outside the pool, while still seeing what’s under, what’s being distorted.

Klein: And this investigation led you further in to abstraction?

Laval: Yes, eventually my focus shifted from water being primarily a subject matter to being the substance and tool I employ to create the work. Since making Poolscapes, I have used the element to reveal transformed reality. So I naturally became interested in using other reflective surfaces, such as Mylar, mirrors, and glass, which echo the distortive qualities of water. My use of reflection is an attempt to explore the tension between representation and abstraction, and to further deconstruct the image. I started using Mylar, which I used with chemically-shifted film, in my series Altered States (2012).

These approaches are similar to how I worked for Heterotopia (2014–ongoing), because I worked with mirrors and glass, particularly with two-way mirrors, which mimic the reflective and see-through effects of the water surface. I moved away from the actual world, but not too far. Instead of the pool, I focused on the garden as a way to pursue my ongoing investigation of the notion of space and our relationship to the environment, both natural and artificial. Flowers are an obvious subject matter for their beauty, but they also offer patterns that can easily allude to abstract forms or alien bodies. I manipulate reflective materials to create layers that convey different meanings, emotions, and can also trigger the imagination of the viewer, as well as mine.

Karine Laval, Untitled #15 (Collision), from the series Altered States, 2012

Klein: The colors you use are vivid and fantastical, but there seems to be a sense of something ominous as well.

Laval: The colors and floral environment are very seductive. But, as you say, there is also something ominous, or something unnatural and strange. The landscapes are clearly a projection of my imagination and my fantasies, but also the product of playfulness in the process of creating the images. I see these landscapes as worlds that don’t exist yet, but which could exist beyond us. The acidic colors act as a vehicle to translate a world in transition or mutation, oscillating between a psychedelic vision of nature and a toxic and artificial post-natural world. They could also belong to the world of virtual reality.

Klein: How is that sense of otherworldliness reflected in the way you choose to present your work?

Laval: I integrated the process of image-making in the final presentation: I chose to face-mount the images to Plexiglas because this is the material some of my mirrors are made of. The effect is sleek and alludes to the screen of the computer. It’s also a very liquid, glossy finish, again referring to water. I purposely picked the high gloss finish because I welcome the reflections on the surface. It’s another layer, and it also reflects the gaze of the viewer.

Karine Laval, Untitled #7, from the series Black Palms, 2014

Klein: You become part of the work.

Laval: Yes. Also the thickness of the Plexiglas gives some depth, and a three dimensional effect. With Heterotopia, I’m introducing my first sculpture. There is a new technology where you can print directly onto Plexiglas; one sculpture has multiple layers of this printed Plexiglas as well as a two-way mirror, which reveals or conceals what is behind it, or both, depending on which side you’re on and how it is lit. As you move in front and around the sculpture, your perception of the image changes. I see it as a metaphor for what photography does. It reveals, but it conceals at the same time.

Klein: Do you feel that the direction you want to move into is more sculptural?

Laval: Yes, for the past few years I’ve wanted to present my work in relationship to architecture. My work is rooted in the landscape and the identity of space anyway, whether it’s about the natural environment, or the built environment, swimming pools, or even my more recent abstract work. When we speak of space, we speak of three-dimensionality, so I think it’s natural that I’m moving in the direction of sculpture. But I’ve also worked in video for about ten years and have made immersive, multimedia projects with nonprofit organizations and alternative spaces. I’m interested in mixing sound, as well as moving and still images to create an environment, an experience for the viewer.

Karine Laval, Untitled 56, from the series Heterotopia, 2014–ongoing. All images courtesy the artist and Benrubi Gallery, New York

Klein: You’ve mentioned other mediums. What are your origins with photography?

Laval: My grandparents lived in Bièvres, a small village near Paris, where the first museum of photography was opened in France. They owned a restaurant where Nadar once developed his film in the bathroom, and the pictures he developed there included some of his first aerial photographs of Paris. I have very vivid memory of going to see my grandparents and visiting that little museum where there were daguerreotypes and old cameras from the nineteenth century. And when I was about eleven or twelve, my grandfather gave me his camera, which I still have. When I started my career—my adventure with photography—I was drawn to photojournalism. I was full of ideals. I worked at the UN for four years. The first photographers that really struck me were photographers working in black and white mostly, such as Josef Koudelka, Gilles Perez, and William Klein. I love the way Klein exploded the frame. And love Daido Moriyama for the same reason. In my younger years I was drawn to William Eggleston and his the way the intensity of his colors almost look like fields of paint.

Klein: For Heterotopia and Black Palms, what led you to make works about perception and seeing?

Laval: Even as a child, I have always been interested in perception. Perhaps it comes from the perception of my own identity—another kind of perception that’s not necessarily optical. My own identity is about knowing where my family came from, but also my own sexual identity, which I was aware of from an early age. When you have those feelings and that questioning within you, it translates into the way you see the world, or the way you want to see the world. And of course my encounter with photography and cinema at an early age made me question perception. I remember when I was a teenager The Twilight Zone was showing on TV in France. I was watching that and wondering what is that world that we don’t see. Is it possible that there is really a world beyond our field of vision? With this body of work I tried to enter that world, that fourth dimension.

Annika Klein is the Editorial Assistant at Aperture magazine.

Karine Laval: Artificial by Nature is on view at Benrubi Gallery, New York, through July 1, 2016.

The post The Garden of Virtual Beauty: A Conversation with Karine Laval appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers