Aperture's Blog, page 141

March 29, 2016

Along the Dinosaur Road: A Conversation with Yto Barrada

Is the trade in precious fossils the next frontier of Moroccan tourism—or just a ruse?

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Ballroom, Arizona), 2014–15

A dual citizen of France and Morocco, the artist and photographer Yto Barrada examines the effects of political and economic currents, as in her first photographic series, A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project (1998–2004), which documented the northbound flow of migration from Africa to Europe through the Strait of Gibraltar. Moroccan citizens, to whom the northern border is largely closed, are forced either to wait for the day they can legally emigrate, or “burn” their past and flee.

In her recent exhibition, Faux Guide, Barrada examines the exploitation of Morocco’s dinosaur trade through a myriad of mediums, including photography, film, and fabricated objects. (According to Barrada, Morocco runs a brisk trade in fake fossils.) Faux Guide also encompasses her Dinosaur Road series, which considers history, science, politics, and the construction of national identity. Previously unpublished, a selection of images from Dinosaur Road appears in “Odyssey,” the spring 2016 issue of Aperture. Introducing Barrada’s portfolio, Carmen Winant leads us along the route—from the tourist hoping to pick up a Middle Jurassic Period fossil to a mineral and fossil trade show in Tucson, Arizona. In Dinosaur Road, Winant sees Barrada’s subtle critique of this pitfall “as a cycle of discovery and myth, erosion and ruin. Some kind of full circle.” Part of Barrada’s series includes documenting Morocco’s unfinished national museums that would, if fully realized, house and protect its national paleontological treasures. Such ventures, possibly a boon to the tourist economy, might also risk degrading the very landscape the museums were built to preserve. I spoke with Barrada in December 2015 about her journey into Dinosaur Road. —Nicole Maturo

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

Nicole Maturo: What is Dinosaur Road, and how do your photographs published in Aperture fit into the larger artistic project Faux Guide?

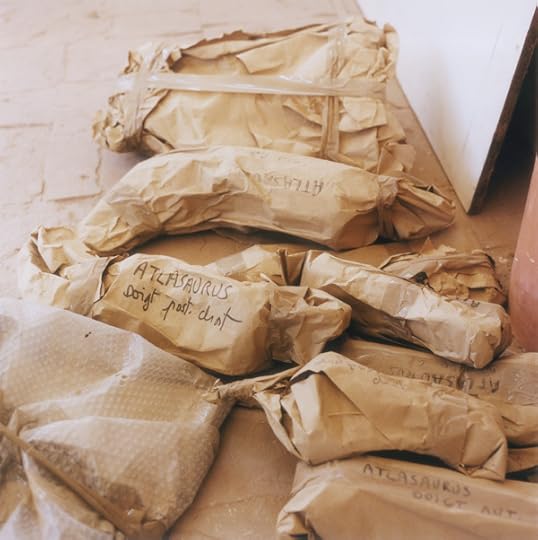

Yto Barrada: Faux Guide (“false guide” in French) was the name of my show last year in London and Nîmes. Dinosaur Road is a group of images about the dinosaur fossil trade in Morocco. It’s also the title of a recent French-language book, La route des dinosaures, by a geologist and his wife, Michel and Jacqueline Monbaron. For years they were working on this project, and it was just published in Morocco. Their goal is to defend two museums that don’t exist yet, which are under construction to house two of Morocco’s main dinosaurs, including one of the biggest, called Atlasaurus.

My project came out of different experiments with recycling stuff collected on my road trip into collages, drawings, textiles, photographs, and books. The artistic avant-garde’s new way of looking at African ethnological artifacts and their collections was also an influence. But my current interests were about the invention of traditions and the question of authenticity. It could seem like a paradox: a tradition shouldn’t be invented; it should be something you pass on. Nationality is a nineteenth-century invention; the nation-state is a nineteenth-century invention. I’m interested in the artifacts, the histories, the stories that are linked to this construction. And the collections of a museum have often played a major role in that construction—how the museum displays the collections, what a museum chooses to put forward.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Dinosaur Road series, Dinosaur Footprints, Iouaridene, High Atlas, Morocco), 2013–15

Maturo: Is “Dinosaur Road” a real place?

Barrada: It’s not one road; it’s a whole itinerary for fossil lovers in the Geoparc M’Goun, where there are lots of sites.

In the trade, if you decide to look at the pyramid of structure, if you’re going to look at the local lumpen proletariat that work to take these fossils from the ground and prepare them; you also have the scientists, and the missions of paleontologists from around the world who can come work, since Morocco is open, making great discoveries. And, in the pyramid of structure, at the top are the dealers, the big dealers who have everything sent to them outside of the country, and deal them at international trade fairs like the Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Balloon, Arizona), 2014–15

The market is changing: natural history events are popular in major auction houses, as well as with the buyers themselves, the people who are decorating their homes with national treasures. That’s one of the big trends: people are buying dinosaurs not to put in a museum, but to put in their living room.

Maturo: How chic.

Barrada: How terrible! What’s interesting with paleontology or history is the way it’s instrumentalized in the construction of a national discourse. That’s what started my interest in dinosaurs. I mean, how come we don’t use the fact that one of the biggest meat-eating dinosaur comes from Morocco? Dinosaurs should be on the tourist poster boards, you know, “Spend your vacation in Morocco with a dinosaur!” The French companies hired to do advertising still talk about “Eternal Morocco,” and show you pictures of the spice markets in Fez. “Time passed everywhere in the world except in Fez.” You could add a dinosaur to the picture, and it would make sense.

On the other hand, if the Dinosaur Road became a popular destination, mass tourism might have tragic consequences by putting pressure on fragile Berber territories. It’s a complex issue because it’s not just about the scientific community wanting to protect the paleontological sites and make the heritage visible locally with museums, it’s also about thousands of families, farmers, and their kids living in these villages nearby: they need the fossil trade to complement their small income and survive.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Salle des fêtes OCP, Khouribga) 2013–15

Maturo: What other forms has this project taken?

Barrada: The discovery of the fake fossil craft became a major part of the project. I made a film called False Start, with a grant from the Abraaj Group. This was also a project supported by the Peabody Museum at Harvard. The trip allowed me to look at the very hard work of the talented preparators and forgers who are making fake fossils. The tools they invent and build for this work are quite astonishing; there is a sequence in my film about the “beauties of the common tool.”

I was also learning a lot and interested in my own visual illiteracy and education. I didn’t know the rocks, the tools, the fossil layers, and the landscapes. Where does their scientific knowledge come from? Most of them are self-taught; they didn’t go to college, they’re shop owners who can bluff their way through—that’s where the Faux Guide title comes from. In Morocco, guys who propose their services to take you around are doing a performance.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (painted educational board found on site of Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

In Tangier, for example, in the pre-smart-phone-GPS-world, you get off the ferry, you have twenty minutes, and you want an oriental experience in the medina, so you would find a partner to tango with and a younger guy would be your “faux guide.” He would give you, for a little bit of money, the typical experience you expect. I have a friend, an anthropologist, who worked on Tangier “faux guides” fifteen years ago.

I’m currently working on a book called A Guide to Fossils for Forgers and Foreigners, to be released this spring. It will have a little section about the “faux guides.” I’m also doing a sort of portable museum, a box, like the Duchamp box museum, where I’m going to put the treasures of Moroccan paleontology. I’m interested in the format of educational material, so it has to be transportable.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (painted educational board found on site of Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

Maturo: You have an academic-oriented research approach to your topics. What did you study at the Sorbonne?

Barrada: I studied history, so with this methodology, I know how to do research, but I have a more inclusive and playful approach, too. I’m looking for new forms. Yet I have a wide scope in terms of forms because I’m always looking for the right shape to transform what I find.

But to get back to photography—on this filming trip, I was interested in the fact that I was totally illiterate in trying to decipher and read the extraordinary landscapes we saw, between the Atlas mountains and the desert—illiterate compared to a geologist, a paleontologist, or a local shepherd who sees so many stories in those rocks.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Painted Sign series, Rock Shop) 2013–15

I would regularly ask my companions on our mission to describe what they saw. The paleontologists, for example, they see everything as if it was still underwater, so it was quite wonderful: the poetry of the scientific vocabulary is unlimited, you get any lithology book, and you just jump in. Or even a book on textile history. I was looking at a catalog and there was this whole thing on telling muslins apart. And there was this sentence that was incredible: “Muslins are made by walking.” I just want to put that in the middle of one of my texts! They’re talking about the way the fabric is made; I don’t know what “walking” means, technically, but it means something in the weaving industry, do you see what I mean?

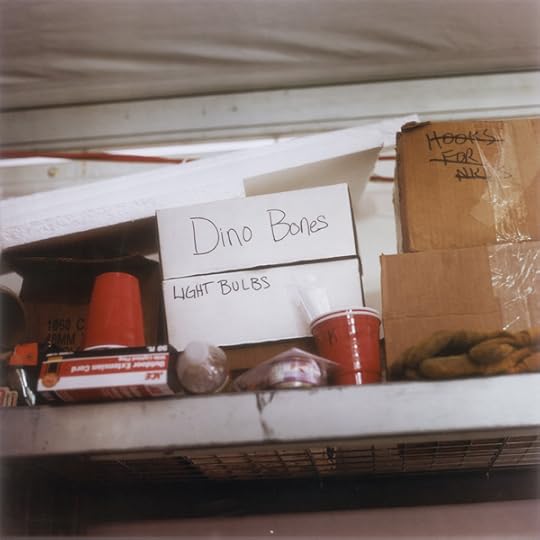

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Dino Bones, Arizona), 2014–15. All photographs courtesy the artist; Pace Gallery, London; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut and Hamburg; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Maturo: Why is it that a lot of people don’t know about dinosaurs in Morocco?

Barrada: A lot of people do know, but they’re either specialists or local bureaucrats or kids. I’m saying there’s no instrumentalization by the state and that is odd. No airport posters, no school posters, no hotel posters. That’s why I made the series of posters, I made the communication—that’s material you can have. I made the toys for the museum so they’d be ready the day the museum opened, because you know that in the modern museum, if you don’t have a boutique, the museum will not survive.

Dinosaurs and fossils are fascinating to me because they involve fiction, forgery, tourism, and economy. You have something that has philosophy imprinted, and then you have the story of imprint—the imprint is like photography. Strangely enough, a fossil is a mold-and-a-cast all by itself; the fossil is already an incredibly faithful copy of the prehistoric creature.

There’s this thing in Morocco around filming or taking pictures—there’s this silly dogma of giving a “positive” image. I’m attracted to the other image, the bandit, the “faux guide,” the magician, the underdog, and the smuggler. In most of my films, the characters I chose are mostly figures of resistance. In a situation of domination, I am interested in how you find a way to keep your head up. Humor is one way; ruse is another.

Nicole Maturo, a former work scholar at Aperture magazine, is an executive assistant at the Aperture Foundation.

Yto Barrada’s exhibition Faux Guide will travel to Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut from May 26 to August 1, 2016, and to The Power Plant in Toronto, beginning in October 2016. A Guide to Fossils for Forgers and Foreigners will be published in spring 2016 by Walther König.

The post Along the Dinosaur Road: A Conversation with Yto Barrada appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 28, 2016

The Foto Cine Clube

In São Paulo, an exhibition explores the global reach of modern Brazilian photography.

By Paula V. Kupfer

German Lorca, Le diable au corps (The devil in the flesh), 1949. Period of circulation: 1949–53

Founded at dawn on a cool São Paulo night in April 1939, the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante played a crucial role in the development of modern photography in Brazil. It was in the 1950s, however, in the midst of rapidly industrializing São Paulo, that its members arrived at the abstracted, formal, modernist style that became their signature. Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante: Do Arquivo à Rede, recently presented at the Museum of Art of São Paulo, is the first institutional nod to the club’s contributions; the curators describe it as a “decisive step in the process of legitimation of modern Brazilian photography.”

German Lorca, The devil in the flesh (verso), 1949

Shown on the second floor of the museum’s iconic Lina Bo Bardi building, 279 prints provide a chronological look at the work of FCCB photographers Thomaz Farkas, Geraldo de Barros, and German Lorca, among many others, from 1939 to the 1980s. The show was beautifully installed, with simple means for an elegant effect: sets of panels on thin metal rods leaned against each other, completely detached from the walls. While the early works betray the photographers’ pictorialist inclinations, subsequent ones demonstrate how their aesthetic morphed into a sharper look at geometry, shadow, and light. The photographs from the 1950s and ’60s that dominate the exhibition echo visual tropes of movements in Europe in the 1920s and ’50s, but capture a distinct Brazilian sensibility—an attitude reflected in ambitious architectural projects of the time and the new São Paulo Biennial (founded in 1951).

German Lorca, Apartamentos ou Apartamento na Mooca ou Apartamentos, rua do Oratório (Apartments, or Apartments at the Mooca, or Apartments, Oratório Street), 1951. Period of circulation: ca. 1951–53

Organized around the ideas of “archive” and “network,” the exhibition reflects both the vast FCCB archive and the global network of photo-clubs they were part of. Stickers, paper tags, and stamps on the backs of many prints confirm the photographs’ active journeys to salons throughout South America; international capitals such as London, Paris, and Singapore; as well as regional cities in the United States, including Louisville and Indianapolis. In what is arguably the curators’ boldest decision, a quarter of the photographs on view are displayed from the back only, their stories told not through imagery but via their travel marks. These stamps offer another way of reading history: their careful designs range from constructivist to art deco and suggest an awareness of international art.

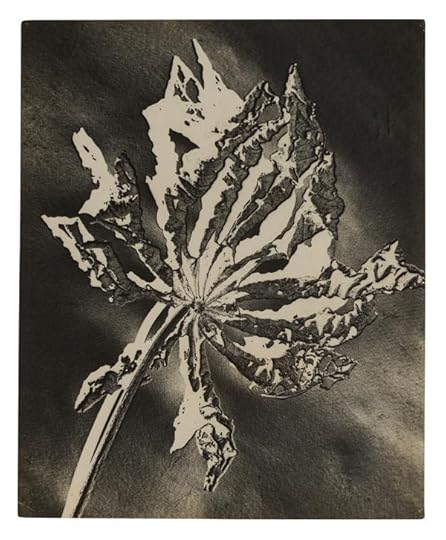

Gertrudes Altschul, Folha morta (Dead leaf), n.d. Period of circulation: ca. 1952–59

Fans of the iconic image makers from the 1950s, including Farkas, de Barros, Lorca, and Chico Albuquerque, will be satisfied, but they’ll also learn about other remarkable figures like Roberto Yoshida, José Oiticica Filho (father of Hélio Oiticica), Kazuo Kawahara, Ademar Manarini, José Yalenti, and Eduardo Salvatore, longtime FCCB president. The show also offers a glimpse at women’s work in the male-dominated club, notably that of German-born Gertrudes Altschul, whose formal and elegant experimental approach is represented in twelve prints.

José Yalenti, Arquitetura ou Crepúsculo (Architecture or Twilight), ca. 1957. Period of circulation: 1957–64. All images courtesy the Museu de Arte de São Paulo

The “archive” aspect of the exhibition left this viewer wanting. A vitrine displays catalogues with stylish covers from the yearly Photography Salons, but the FCCB’s assiduously maintained bulletins, published from the ’40s onward, are nowhere to be seen. Extracted quotations related to photographic genres and techniques, questions about the medium, and the role of the photo club, are scattered across a wall, but it comes off as a modest effort masking a missed opportunity to highlight the group’s committed effort to record-keeping and critical discussion. (They diligently reprinted critical articles and reviews from local press and international publications, documented club events and excursions, and kept track of members’ inclusion in international salons.) That said, the exhibition places the photographs at the center, foregrounding the photographers’ work, and thus attests to their aesthetically innovative spirit and lasting contribution to the story of modern photography.

Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante: Do Arquivo a Rede was on view at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo from November 27, 2015 to March 3, 2016.

Paula V. Kupfer is a writer and editor based in New York. Formerly the managing editor of Aperture magazine, she is working on her master’s thesis on 1950s photography in São Paulo.

The post The Foto Cine Clube appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 24, 2016

From the Outside In

In exploring the lives of others, what are the virtues of an outsider’s position?

By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Spread from Dana Lixenberg’s photobook Imperial Courts, 2015

What did the participants hope would result from their share in this common ritual? At the least, they knew themselves to be partnered in an open-ended but definite transaction.

— Max Kozloff, “Variations on a Theme of Portraiture,” Aperture 114, 1989

Dutch photographer Dana Lixenberg’s latest book Imperial Courts (2015) is a collective portrait of the inhabitants of a housing project in Watts, Los Angeles. The work began in the wake of the riots that exploded in April 1992 following the acquittal of four white police officers who were filmed beating Rodney King. By coincidence, Lixenberg completed the work in spring 2015, in the full heat of protests in Baltimore that followed the death of Freddie Gray from a spine severed while in police custody. In the book, as Lixenberg gradually introduces a large cast of individuals, we are struck by the complexity of reckoning with time mapped across faces over so many years. Imperial Courts grants us entry and proximity as outsiders to a small, neglected, inner-city community, raising a question addressed by the work itself, but pertinent to much contemporary photographic practice: What are the virtues of a photographer’s position on the outside of a world looking in?

Spread from Dana Lixenberg’s photobook Imperial Courts, 2015

With the exception of the book’s cover image, showing the extension of a highway intersection that opens onto Imperial Courts, Lixenberg made every photograph within the housing project. Across 343 pictures, she patiently tracks multiple generational changes: parents age, children are born, and daughters become grandmothers in the span of these pages. Lixenberg first photographed infant Dee Dee in 1993, wearing patterned braids and perched on her father Chin’s lap, then as an adolescent in 2008, and finally as a mother in 2013, proudly holding her infant son Emir. We see China, her hair neatly bound up in rollers in 1993, and her elegant daughter Keisha some seventeen years later, now mother to an infant Romeo, and sister to an adolescent Tye, whose oversized earrings hark back to the fashions of China’s youth.

Spread from Dana Lixenberg’s photobook Imperial Courts, 2015

Lixenberg’s photographs issue from the lengthy, purposeful collaboration required by a 4 x 5 camera. As such, they place particular emphasis on the formal presentation of the self. These individuals are intensely aware not only of the camera, but also, seemingly, its foreignness to their community—and, by implication, the foreignness of the photographer herself. In portraits of Trouble (2009), Jeff (1993), and Marylee (2010), we sense a relationship to Lixenberg shaped by circumspection and pride, which is complicated as Jeff reveals a small measure of sadness, or as J-50 warms to the camera over an interval of fifteen years.

Lixenberg’s rejection of the spectacle of ruination following the riots of 1992, and her use of portraiture to record changing American families, reflects her disavowal of the reflexive linkage of blackness with crisis. This choice does not redress the innumerable daily injustices of white supremacy, nor could it. But Lixenberg’s portraits underscore the value of individual and communal life, even as such life plays out in the abandoned urban zones that undergird economic “progress” in the United States. Imperial Courts momentarily closes the symbolic and physical distances inscribed in the landscape and culture that it traverses. It is work possessed of a degree of lucidity, specificity, variety, and beauty that is the equal of the many people depicted.

Spread from Petra Stavast’s photobook Ramya, 2014

While Lixenberg initially traveled from Amsterdam to Los Angeles to make portraits of unfamiliar people, her compatriot Petra Stavast turned to her upstairs landlady in Amsterdam, refusing the stable comfort of anonymity with a neighbor for the volatility that accompanies a more intimate relationship. Where Lixenberg became involved in the history of a foreign community, in Ramya (2014), Stavast immersed herself in the life an equally unfamiliar but proximate stranger—each artist was thus drawn into reciprocal and changing relationships with others by the inherently social nature of photography.

Spread from Petra Stavast’s photobook Ramya, 2014

Stavast’s desire to make portraits was the catalyst for her decade-long relationship with Ramya, the eponymous subject of her latest book. In it, she sketches the fascinating shape of Ramya’s life through an array of photographs, video stills, documents, and transcribed conversations. In Stavast’s early series of portraits, Ramya rejects any formal etiquette, while accommodating the camera’s presence with a mixture of bemusement, boredom, disbelief, and disinterest. While there are occasional intimations of mutual curiosity in these pictures, the cumulative effect of the series underscores the slippery imprecision of a portrait’s static address. Ramya is certainly aware of the camera, but apparently habituated to its presence. As she becomes successively less guarded, she reveals her mercurial, complex charisma.

Spread from Petra Stavast’s photobook Ramya, 2014

The book is marked by the somber fact that Ramya died during the making of the work, and its multi-layered composition results from the imperative Stavast felt, after her death, to delve deeper into the record of Ramya’s history. Thus Stavast discovered Ramya’s membership in the Rajneeshpuram commune in rural Oregon in the early 1980s, and that prior to this, Ramya had been known by another name. In stills from Ramya’s Oregon video footage, Stavast searches out the woman she knows to have been present, but can no longer reliably identify, selecting possible candidates from the crowd, and enlarging them to a point of degradation at which the pattern of a dot screen is legible, as if to revivify the gene of a past sealed away within the surface of the image itself. Ramya underscores the unpredictable nature of relationships facilitated by photography, but also the closeness that can come from the repetitive act of portraiture. Across the book’s pages, we are compelled to reckon with the mysteries of those people who are momentarily closest to us, and we are left with the compelling imperfection of memories and images.

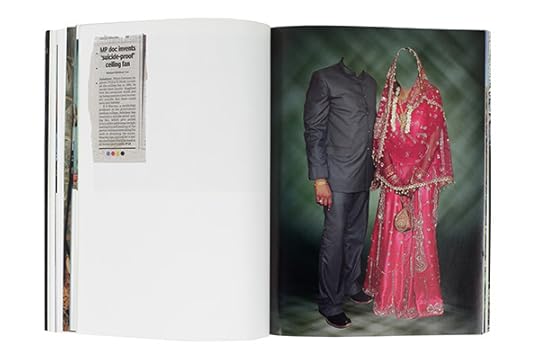

Spread from Max Pinckers’s photobook Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty, 2014

Amongst Ramya’s documents from her time in the commune are mental exercises on redefining the self, in one of which is written, “YOUR REALITY IS CREATED BY YOUR MIND!” These mantras speak to a faith in mental images as tools for creating unimagined futures. Such notions are taken up by Max Pinckers in his self-published book Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty (2014), which explores forbidden romantic love within the Indian caste system through its relationship to the imagery of Indian cinema. Pinckers, born in Belgium and raised in Asia, photographed couples who hope to transform tradition by ignoring caste restrictions on marriage. Thus the love of his protagonists is a projection of faith in the prospect of change held over against an inflexible past.

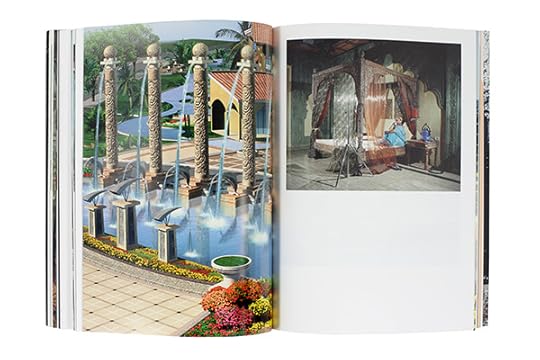

Spread from Max Pinckers’s photobook Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty, 2014

Will They Sing Like Raindrops retains a buoyant optimism in the face of the violent threat of repression to which these couples are all too frequently exposed, intimated in a photograph of bloody fingers or in gruesome news clippings scattered pointedly throughout the book. Pinckers’s recurrent use of what western art photography calls the “tableau” derives from his fascination with the populist force of Indian cinema, whose melodramatic affect has its roots in pre-medieval theories of Indian theater.

In his overtly staged melodramas, couples embrace alongside tumultuous seas beneath patterned fabrics “lit” by the mirrored glare of artificial light, or fling forbidden missives across rooftops above houses whose walls separate them from one another. Pinckers’s portrait of a star-gazing woman regally smoking atop a four poster bed recalls Larry Sultan’s pictures from The Valley, and speaks not only to the currency of cinema’s hold on human imagination, but also to the irrepressible yearnings unchained by the image’s capacity to enlist us in willful dreaming. In this way, Pinckers’s work reveals the disjuncture between the freedom of images and the rigidity of political will.

Spread from Max Pinckers’s photobook Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty, 2014

Lixenberg, Stavast, and Pinkers’s books deploy an array of forms and strategies that seek to contextualize the people they depict, and to ground us in the individual and communal worlds their work outlines. In contrast to the pejorative books I explored in my essay “The Lives of Others,” published on this site in October 2015, these works reject the facile tropes common to deterministic treatments of the Other. Moreover, each of these three artists have rejected the liberal strain of determinism, which seeks to proscribe artists from making certain work on the basis of their ethnicity, gender, nationality, or relative wealth. Such proscriptions (commendably) attempt to mitigate the effects of real systemic inequalities, but they essentialize these categories as absolutes in the process.

Were we to accept a contemporary photography in which artists depicted only those people they resembled, we would be bereft of the diversity we rightly crave and defend in social life. We would be guilty of conforming human imagination to the rigidity of political norms. The representation of others affords us new means to claim a commonality that respects our differences, while reminding us, as Toni Morrison wrote of the portraiture of Robert Bergman, that “the stranger is … not alien but remembered.”

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, a photographer, writer, and editor of The Great Leap Sideways, is a faculty member in the photography department at Purchase College, SUNY.

The post From the Outside In appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 23, 2016

2016 Aperture Summer Open: A Conversation with Charlotte Cotton

The call for entries is now open for the Aperture Summer Open, an open-submission exhibition for which all image-makers are eligible. Entries for the exhibition will be accepted until Wednesday, April 6, 2016 at 12:00 p.m. EST.

This year, the exhibition will take its cue from Aperture’s recent publication Photography Is Magic, and will be curated by the book’s author, Charlotte Cotton. As Cotton notes, a single, “straight,” photographic image can be as rich, complex, and magical as one essentially made in post-production. Aperture Foundation’s executive director, Chris Boot, recently spoke with Cotton about the relationship between photography and magic and how she expects the exhibition to come to fruition.

Bubi Canal, Beautiful Mystery, from the series Dreamtime, 2015

Chris Boot: You came up with the phrase “photography is magic,” a brilliant slogan for what’s going on in photography at the moment, even for the medium as a whole. Where did you get the idea for it?

Charlotte Cotton: I often decide on a project’s title quite early on in the process—it helps me keep a project on track! The title is intentionally optimistic and multi-layered, which was important to me. Originally, there was an exclamation point in the title—Photography is Magic!—but as the book began to take form, we felt that the imagery included did the work of the exclamation point. Of course, the title refers to actual, secular performance of magic—and I write about that in the essay. In particular, I was interested in the idea of a close circle of magicians paying attention to the skill, craft, and innovations in the magic being made by their peers. That feels like an important aspect of contemporary art photography, and relates to the literal and intellectual connections between practitioners at a global level. And you are right: the title at its most general makes an enduring declaration that photography is a magical medium.

Boot: Doesn’t it also refer to the history of photography? I grew up in a world of photography where the darkroom was central, where the emergence of a picture on a piece of paper in the developing tray was always thought of as “magic.” Photography has always been a medium of magical transformation, hasn’t it?

Cotton: The alchemical magic of photography is a very established line of thought. But what I’ve become interested in is the idea of magic as something that is triggered in the imaginations of the viewers of a magician’s sleight of hand—something much more to do with the perception, reception, and attention given to photographic imagery rather than what you are talking about, which is the magic of photographic processes. While I do think that your magical alchemy is undoubtedly alive and well and at play in the practices of contemporary photographers, the magic I’m interested in is that which is activated in the viewer—those transformations and awakenings of perception that art and its processes can prompt.

“I am as interested in photographs that embody this very special, and magical, type of engagement with the unfolding of real time that photography has always provided.”

Boot: The Photography Is Magic book is about a very particular group of artists who are deconstructing and reconstructing the traditional expectations of photography in very playful ways, often using scissors, computers, etc. But you’re treating the idea of “magic” more broadly for the Summer Open. Can you say a little more about the idea in this context, and about what you’re excited to see? Can “straight” photographs—scenes represented as they appeared in front of the viewer, via a camera, without manipulation—serve the idea of photography as a magic medium, and might you select some “straight” photographs?

Cotton: The book does concentrate on the work of artists who are highly conscious of every active choice they make in their photographic work, from the choice of the ostensible subject to the use of analog and digital techniques (and their hybridization), through to the rendering of physical objects. My choice to concentrate on a range of related motivations and working processes in the book is not, of course, the full extent of where I see photographers drawing our attention to the magic of photography. And, yes, I am very, very interested to see Aperture Summer Open submissions that approach the theme in other ways.

When I am looking at so-called “straight” photography, I am often drawn to pictures that I think of as “lucky pictures” or “pictures waiting to happen,” you know, those kind of celestial “gifts” that you can come across when you are working and looking photographically. I am as interested in photographs that embody this very special, and magical, type of engagement with the unfolding of real time that photography has always provided. A single, “straight,” photographic image can be as richly complex, fantastically confusing, and inherently magical as one essentially made in the post-production and rendering stages of photographic practice.

“The idea about photography that I am obsessing about centers on curating image and media streams in real time.”

Boot: You look at new photography all the time. Can you mention a couple of things—single pictures, bodies of work, or even ideas about photography—that you’ve encountered this year, that you were really excited to see . . . or hear or read?

Cotton: Some photographers have contacted me in response to the launch of the Photography Is Magic book and I’m thrilled to know about their work (and a little sad that I did not see it before we went to print)! Valerie Green’s practice has been a welcome revelation to me. Right now, the idea about photography that I am obsessing about centers on curating image and media streams in real time. It’s my first real foray into this area. I’m collaborating with an amazing thinker and creator, Mark Ghuneim, and we are working with Elizabeth Kilroy and her New Media Narratives students at ICP. You will see the fruits of our labors at ICP’s new space at 250 Bowery when it opens in June this year.

Boot: Five years ago, I think most of us involved in photography felt we were in the throes of an incredible revolution, and we had no idea what the world of photography might become. Now it feels like we’re in a new landscape for photography, but the pace of change has slowed down. Do you think the revolution has happened, and we can begin to see it in the past tense? Or is it still just the beginning?

Cotton: Oh, I think this is only the beginning. But beginnings are exciting and perhaps the slowing down that you’re feeling is more to do with us having reached a bit of a plateau where we can take a breath, look around us, and pay attention to what has unfolded so far. Within that is the chance to think about both the ongoing magical properties of photography and what is genuinely new within this landscape of practice. And that’s a collective effort for us all—sharing and linking our perspectives, thinking about our own individual practices in relation to others’, and mapping an extremely exciting chapter in photography’s story.

For more information on how to enter the 2016 Aperture Summer Open, visit aperture.org/summeropen or contact summeropen@aperture.org.

The post 2016 Aperture Summer Open: A Conversation with Charlotte Cotton appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 21, 2016

First Look: photo+craft

An upcoming festival in Asheville, North Carolina, investigates the intersection of photography and craft.

By Diana C. Stoll

Clarissa Sligh, detail from artist book What’s Happening with Momma? (Outside), 1988. Courtesy the artist

The overlaps between craft and photography have long been a matter of debate, provocation, wonder, and perplexity. The two fields and their places of intersection will be considered later this month at photo+craft, a four-day gathering in Asheville, North Carolina.

Located in the state’s western mountains, Asheville has a dynamic history in both disciplines—most notably, perhaps, as the city nearest to Black Mountain College, where original minds and ideas percolated from 1933 to 1957. At Black Mountain, particularly under the demanding eye of Josef Albers (who headed the school’s painting program for more than a decade), the distinction between craft and fine art was more or less moot: what was being taught were fundamental processes of creative thinking—channeled through media that ranged from weaving to pottery to farming to writing to mathematics to dance to sculpture, painting, and photography. (Among the school’s photography faculty at various points were Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, Arthur Siegel, and Beaumont Newhall.)

Alejandro Cartagena, from the series Suburbia Mexicana, 2006–09. Courtesy the artist

Asheville is home today to the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, devoted to the school’s legacy—both its literal archive and its spirit. The city is also a hub of crafts institutions: the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design is here, and nearby are the Penland School of Crafts and John C. Campbell Folk School (the latter lovingly documented by photographer Doris Ulmann in the 1930s). The surrounding hills boast a rich and immeasurably deep history of individual makers and a tradition of artistic community that continues today in Asheville’s many galleries and studios.

At photo+craft, the intersections between the two disciplines will be investigated in exhibitions, workshops, and panel discussions taking place throughout the city. Two keynote speakers will anchor the festival, each an authority in one of the fields under consideration. Igniting the conversation about craft is Namita Gupta Wiggers, curator, teacher, and cofounder of the Critical Craft Forum, a web-based matrix for dialogue and resources on craft. Photography’s rapidly changing forms and roles will be addressed by Fred Ritchin, dean of education at New York’s International Center of Photography, whose publications include In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography (first published in 1990, with revised editions in 1999 and 2010) and After Photography (2008). Ritchin’s Bending the Frame, which addresses, among other things, photography’s evolving role as a tool of advocacy and progress, was published by Aperture in 2013—his talk at photo+craft shares its title.

Elijah Gowin, Cd Relic. Courtesy the artist

The evolving understanding of digital approaches is of course a central topic at photo+craft. Among the weekend’s panel discussions is “Ghosts in the Machine: Finding Craft in the Digital,” at Asheville’s Altamont Theatre, featuring three artists whose practices challenge boundaries among media and among means of representation. James Huckenpahler creates images, books, and “virtual sculptures” on a laptop computer; Vesna Pavlović plays with perception, using, in her words, “analog photographic technology . . . in a contemporary digital mode”; and Elijah Gowin freely combines old photographic tools with new—from paper negatives to scanners—to achieve a unique and palpably handmade feel in his images. Also at the Altamont, filmmaker Harvey Wang will screen his 2014 documentary From Darkroom to Daylight: a look at the transition from film to digital photography as seen through the eyes of more than twenty eminent photographers.

In his book Bending the Frame, Ritchin insists that photography can be proactive instead of reactive, offering solutions to social conflicts rather than simply documenting them. Can the same be said of craft? The question will be considered from multiple angles this weekend, including at “Making and Meaning: Photobooks and the Social Fabric,” a discussion between Clarissa Sligh and Alejandro Cartagena, moderated by Eric Baden (photographer, educator, and photo+craft’s project director). Sligh’s long career is marked by candid engagements with social issues; her many photo-based artist’s books have tackled such fraught questions as white hegemony (e.g. in Reading Dick and Jane with Me, 1989; and It Wasn’t Little Rock, 2004) and the complexities of sexual identity (in Wrongly Bodied, 2009). Cartagena frequently turns his lens to the life and people of Monterrey, Mexico, creating images of disquieting stillness, at odds with the rampant violence of this northern region of the country. The photobook is a vital space of dissemination for both artists.

Steve Mann, The Boneman, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2007. Courtesy the artist

Related exhibitions will be presented throughout Asheville, including photographer Steve Mann’s Orthogonal Convergence at Pink Dog Creative, and the group show Authentic Constructions at the Henco Gallery, featuring the work of Janelle Young, Christina Z. Anderson, Constance Thalken, and artist duo Lindsay Lochman and Barbara Ciurej. Ancillary shows will be held at the Asheville Art Museum, the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design, Penland, and other venues around Asheville. In addition, a workshop titled “Cameraless Photography: Silver Figurative Rendering Salon” will be led by Robert Asman; and renowned photo-printer Rocky Kenworthy (who has printed for such luminaries as Annie Leibovitz, Don McCullin, Sebastião Salgado, and many others) will offer a tour of his Dot Editions studio.

Photo+craft winds up on Sunday, April 3, with “Building a Collection,” a talk with Asheville-based collectors Hedy Fischer, Randy Shull, and David Raymond. A portion of Raymond’s vast photography trove was recently acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art and featured in the museum’s 2014–15 exhibition Forbidden Games: Surrealist and Modernist Photography, The David Raymond Collection. Undoubtedly under discussion here will be the weight of photography and craft’s existential (and monetary) value in relation to Art with a capital A. Or could it be that now, in 2016, that matter no longer has meaning? Just as the frontiers seem to be rapidly dissolving between creative fields, so they are, perhaps, between Art and Craft, between Art and Photography.

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in North Carolina. She is the coauthor, with Lin Arison, of The Desert and the Cities Sing, forthcoming from Chronicle Books in fall 2016.

photo+craft, sponsored by Warren Wilson College, will take place at venues throughout Asheville, North Carolina, March 31–April 3.

The post First Look: photo+craft appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 18, 2016

Archipelago

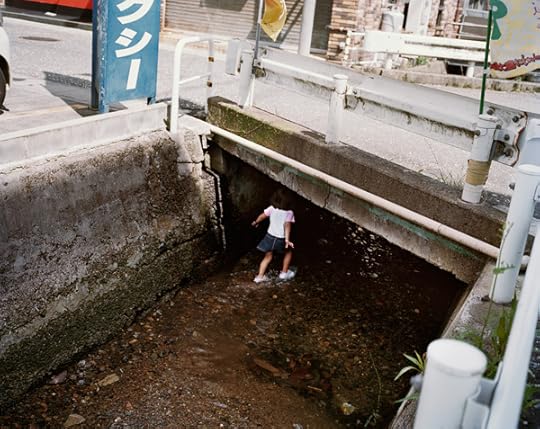

Across ten years, Ishikawa Naoki traveled Japan’s island chains, from the far south to the far north, depicting canted colorful scenes of everyday life and ceremonial traditions. This article is drawn from the recent “Odyssey” issue of Aperture magazine.

By Niwa Harumi

An adventurer turned photographer, Ishikawa Naoki has journeyed from the North Pole to the South Pole using only human-powered vehicles. He is the youngest person ever to have scaled the highest peaks on all seven continents, as well as K2, one of the world’s most hazardous mountains. But Ishikawa, who was born in Tokyo in 1977, doesn’t travel out of a desire to conquer nature—but rather, as he says, in order to relativize his own perspective.

For his series Archipelago (2009), made over ten years, Ishikawa traveled around the numerous island chains in the seas to the north and south of Japan. The artist’s twenty-first-century project to reposition Japan—once seen as being on the far edge of the world (“the land where the sun rises”), as one cluster in a long chain of islands in Asia—and to reconsider its history and culture in that context is an act redolent with implications. From the southernmost tip of Kyushu he traveled to Okinawa, the Yaeyama Islands, the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, and Kinmen, a tiny group of islands situated within a hair’s breadth of the Chinese mainland that has several times become the site of fierce territorial battles between Taiwan and China. For his travels in the north, he went to Sakhalin, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Bering Sea—and even as far as Haida Gwaii in the Gulf of Alaska.

Throughout the islands, Ishikawa devoted himself to documenting local festivals and practices, as well as people’s daily lives. “There are certain realities that disappear when you package them up in language,” he says. “My idea is to break through all that, and simply present the things in the world.” His work attempts to view afresh customs and ceremonies, teasing out histories and cultures on the margins that have been overlooked in favor of cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

Festivals in the Tokara Islands, to the south, and also in further islands, are quite different from those you might find on Japan’s main island of Honshu, having more in common with traditions in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, or Taiwan. In a world we are continually being told has shrunk with the power of the Internet and the effects of globalization, fascinating customs and practices abound that are unique to particular cultural and spiritual topographies. “Before we had political boundaries, it was each local area, each locality—that was all that mattered,” Ishikawa explains. “The world was made up simply of individual places.” As we gaze at such places through Ishikawa’s eyes we experience this topographical uniqueness in a direct, unmediated way.

The photographs in this series are often compared to Shomei Tomatsu’s prizewinning 1975 book on Okinawa, Taiyo no empitsu (The pencil of the sun). But the impulse behind Tomatsu’s images is different in character—his are real-time documents shot through with experiences of the political realities of the postwar years. Ishikawa’s work, set in present-day Japan, well past the postwar period, is impelled by a more epistemological project, an attempt to express the idea of what it is to know. Facing both north and south, he fits together the various pieces of an archipelago of his own design. Today, in 2015, pivotal changes are occurring in Asia that could never have been foreseen when this collection first came out seven years ago—the China–U.S. summit meeting, the historic meeting between President Xi Jinping of China and President Ma Ying-jeou of Taiwan. The archipelago that Ishikawa envisioned now seems situated like the long arc of a bow taut with the tension of what was yet to come in the relations between Asia and the rest of the world.

Niwa Harumi is a curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Translated from the Japanese by Lucy North.

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Archipelago appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 17, 2016

Of Refugees and the Photograph

In conjunction with the recent “Odyssey” issue of Aperture magazine, Fred Ritchin examines photography of the refugee crisis.

Nina Berman, Installation view of Zaatari: Inside These Walls, March, 23, 2014. © Nina Berman/ NOOR

Have we done enough in the field of photography to represent the enormity and the suffering of the current refugee crisis? There are now some sixty million refugees and internally displaced people in the world, a population that would constitute the world’s twenty-fourth largest country, after Italy. Has the huge amount of imagery that has been produced related to this human disaster helped to significantly alleviate the widespread anguish and distress, to minimize the deaths, to promote a more just resolution of the crisis?

In the past, the first question, when asked of photographers and editors, may have been sufficient given the prevailing social contract that photographing tragedy, especially at this scale, was intended to be instrumental in eliciting a societal response (not that it always succeeded). In this paradigm, suffering was not displayed from the vantage point of voyeurism, but as part of a witnessing function that attempted to compel media and governments to investigate further and to decide, whenever possible, upon a course of action to at least partially rectify the situation depicted.

This is what Cornell Capa meant when he proposed the field of “concerned photography” half a century ago, and founded the International Fund for Concerned Photography (later the International Center of Photography). It was a term that provided some meaning, perhaps even solace, after the sudden death of his brother, Robert, who was killed in 1954 while covering yet another war, this one in Indochina. It was also a term that could serve to validate the work of many others, such as Werner Bischof, Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, David “Chim” Seymour, and W. Eugene Smith.

This social contract seems to have been in play last September when photographs were widely distributed of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, a Syrian refugee who, along with his brother and mother, drowned while trying to escape to the West. Politicians, including Britain’s David Cameron, who said “as a father” he had been deeply moved, responded more quickly and viscerally than usual. Many other commentators stated how Alan Kurdi reminded them of their own child, dressed with care and love. There seemed to be something different in these images than in the multitude of other pictures of refugees meeting difficult and terrible fates. Alan, his face largely concealed from the camera, seemed serene, lying on his stomach on the sand where it met the water, his palms up, wearing blue shorts, sandals, and a red shirt. He seemed, at first glance, to be almost sleeping, but the awful truth was that he had been abandoned by the larger society, and he was dead.

Nilüfer Demir, Paramilitary police officer investigates before carrying the body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi from the sea shore, September 2, 2015. Courtesy AP Photo/Nilufer Demir, DHA, File

A Turkish photographer, Nilüfer Demir, made the images of Alan from a respectful distance. The child was not asking anything of the viewer—it was too late. The viewer was not to be confronted by the tormented faces of refugee families screaming and crying, pushing against barbed wire, lying on railroad tracks, frenzied and exhausted, asking for something to be done. Instead, in the image of Alan Kurdi, there was a hint of divine grace, a sense of stillness rising above the cataclysm from which his family had been trying to escape, and above the cynical politics strangling their home country. Rather than joining a manipulative war of images to clamor for the public’s consideration, these photographs asserted tragedy quietly, with minimal polemics.

Others felt the image should not have been published, that showing a dead child was outside the bounds of decency. Peter Bouckaert, Human Rights Watch’s director of emergencies, wrote a bluntly eloquent blog post responding to this criticism under the title, “Dispatches: Why I Shared a Horrific Photo of a Drowned Syrian Child.” In it he writes, “Some say the picture is too offensive to share online or print in our newspapers. But what I find offensive is that drowned children are washing up on our shorelines, when more could have been done to prevent their deaths.”

Without the political will and a sense of what might be done to implement change, such photographs can be seen, rather than as iconic and motivational, as part of a detached, consumerist spectacle. Nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc being napalmed in 1972 during the Vietnam War, or Nguyen Van Lem of the Vietcong being summarily executed in the streets of Saigon in 1968 by national police chief Nguyen Ngoc Loan, transcended the prurient because the roiled body politic felt that something could be done—massive protests leading to a military withdrawal. The 1968 Christmas Eve photograph of the Earth from outer space, looking fragile in the universe, led to the first Earth Day sixteen months later, and provided momentum for an emergent, activist engagement with the environment. And, more recently, the images of torture from Abu Ghraib prison that were made by soldiers also provoked moral outrage and a turn against the war in Iraq.

But since the Abu Ghraib images were released in 2004, other than those of Alan Kurdi eleven years later, few—if any—photographs have had a similarly forceful impact on world opinion. There have not been photographs that have resonated as much as the one of a hooded prisoner in Abu Ghraib, his arms outstretched Jesus-like with wires dangling from them, captioned by The New Yorker, “An Iraqi who was told he would be electrocuted if he fell off the box.” It may be, in part, because these photographs were made as an aspect of the torture by the soldiers themselves, and have a casual, party-like, perverse quality that circumvents the growing skepticism surrounding professional imagery, with its higher production values and more targeted messaging. Professionals often represent suffering in photojournalistic tropes that focus on the “other,” and not on “us.” The Abu Ghraib images and, to a certain extent, those of Alan Kurdi can be seen from the perspective of “us,” or, even more tellingly, of “me.”

“Photojournalism is a great tool for telling very simple stories,” former photojournalist Simon Norfolk, who has worked extensively in Afghanistan, stated in a 2006 interview. “Here’s a good guy. Here’s a bad guy. It’s awful. But the stuff I was dealing with was getting more and more complicated—it felt like I was trying to play Rachmaninoff in boxing gloves.” The complexity of the contemporary refugee crisis, including the lack of clarity as to political solutions and the fear that societies opening their frontiers will be destabilized, makes it impossible to assert a simplistic narrative, to always tell the “good” guys from the “bad.”

This may be a reason why the smuggling by a military policeman code-named Caesar of fifty-five thousand forensic photographs of eleven thousand young Syrian detainees killed in prison by the Assad regime, many of them also tortured (their cause of death was to be reported as “either a ‘heart attack’ or ‘breathing problems’”), had very little effect on the world when in 2014 they were made available (I wrote a piece about them for Time magazine). Apparently the images of a three-year-old boy that appeared the following year were more difficult to deny.

But would images of refugees similar to those of Alan Kurdi be taken so seriously again? Following the sexual attacks on women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve by men described as predominantly North African, and other troubling events relating to immigration in Europe, it has no doubt grown easier for many to deny their own empathetic responses and for others to promote xenophobic agendas. (While only three of the fifty-eight men arrested for the Cologne attacks were identified as recent refugees from Syria and Iraq, the majority of suspects were said by the police to be of Algerian, Moroccan, or Tunisian descent.)

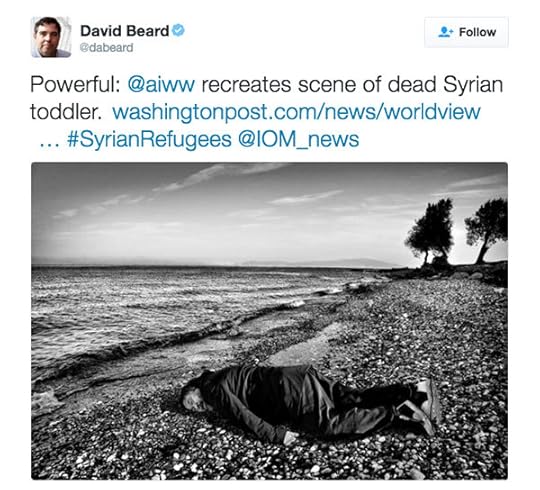

The problem, of course, is broader, as photographs are now more easily contested and disbelieved. Social media—Web 2.0—does a powerful job of interrogating assertions, whether verbal or pictorial, including those from news sources and governments. And an entrenched sense of consumerism, in which it is the discrete viewer/consumer who matters and is societally entitled, makes it more difficult to arrive at a sense of collective responsibility. Is the photograph of Ai Weiwei sprawled on the beach in a pose intentionally similar to that of Alan Kurdi a gesture of empathy, a commercial self-promotion for the India Art Fair, or both?

Ai Weiwei’s recreation of the Alan Kurdi photograph, as seen on journalist David Beard’s Twitter feed. A print of Ai Weiwei’s image was displayed at the India Art Fair.

There are, of course, other attempts by photographers to directly help their subjects. For example, the project by four members of the Noor agency to create mural-sized portraits of Syrian refugees in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan (often shown with an object that each one cherishes), along with photographs of daily life, was largely an attempt to reiterate the dignity of these refugees for themselves—the images were placed on the inside of the camp’s walls, making its denizens the primary audience. Also, photography workshops for refugees to express their new and old realities, both in camps and in the countries to which they have migrated, are at times useful, and can help others understand more of who they are.

Photographs of young Iraqi Yazidi women who were enslaved by ISIS and taken to Syria, published alongside lengthy texts that recount their stories, underline a particularly savage migration. The women are shown in white bridal dresses to restore a sense of purity, while their faces are intentionally obscured by veils. Seivan M. Salim, a female photographer from the independent Iraqi agency Metrography, made the images and conducted the painful interviews. Muna, an eighteen-year-old who was forced into captivity for four months as of August 15, 2014, states: “They forced me to go with them when I was in Tal Afar. They said, ‘If you don’t come with us we will behead your two young brothers,’ and I had to go with a man to Mosul. I worked in his family as a slave. They forced me to become a Muslim. Although he had a wife and a family he always slept with me. When we were besieged in Sinjar the fighters of ISIS threatened us by showing on a mobile how they beheaded some Peshmerga fighters. Five members of my family are still held by them, and I don’t know where they are, or if they are still alive.”

Seivan M. Salim, Muna from the project Map of Displacement, 2015. Courtesy the artist/ Metrography

Sadly the photographs remained unseen for a time, according to Metrography’s cofounder Sebastian Meyer and its editor-in-chief Stefano Carini, as Western media appeared hesitant to publish the work. That only changed when Marcia Allert, director of photography at the Daily Beast, took an interest after seeing the photographs and meeting Meyer and Carini last September at a panel discussion, “The Representation of War—From Capa to Instagram,” at the International Center of Photography. Since appearing in the Daily Beast on November 6, the work has been published in many countries.

What, then, are the issues complicating the previous social contract in which photographic witnessing could be, although certainly not always, relied upon as a spur to action? Might it be that the fragmentation caused by billions of photographs uploaded online daily, representing the world as a collection of disparate single two-dimensional rectangles made over fractional seconds, makes it more difficult to place both the images and the events that they are meant to signify in a universe of cause and effect? Might it be also that the frequent controversies surrounding the manipulation of photographs via software and the staging of events have contributed to the medium’s diminished standing as social referent? Could it be as well that short videos and their more explicit narratives, such as the many we have recently seen of police brutality in the United States, are perceived as more credible and as a result galvanize more concern, particularly when emerging from a society in which the pursuit of legal recourse is possible?

Today’s refugees are being photographed attentively and widely. But today’s photographers, in a world riven by stridently competing perspectives exacerbated by the dissonance of much of social media, have difficulty providing a declaration of moral right. It is hardly coincidental that today’s politics have a similar problem.

Fred Ritchin is Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography and author, most recently, of Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (Aperture, 2013).

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Of Refugees and the Photograph appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 13, 2016

Bill Armstrong: The Secrets of Color in Photography

Bill Armstrong, Untitled (Film Noir #1433), 2012

“I recommend Bill Armstrong’s color workshop 100%. His understanding of color in photography is unparalleled. . . . He is a working artist who understands and can talk about his medium. My experience of his class was incredibly valuable and full of insights.”

—W.M. Hunt

Join photographer Bill Armstrong for a two-day workshop designed for photographers of all skill levels who would like to learn the aesthetic principles behind creating strong color photographs. The workshop will focus on how to unleash the power of color for maximum impact. Exploring both the technical and aesthetic aspects of color, Armstrong will examine such topics as how the eye sees color; the contrast and harmony of colors; color and time of day; color mood and meaning; and the psychology and symbolism of color.

Through lectures, visual presentations and hands-on exercises students will gain a core understanding of how color works, which will improve their technical ability to shoot and print. Light refreshments and lunch will be provided on both days. Please contact education@aperture.org with any dietary restrictions at least one week before the workshop begins.

Bill Armstrong is a fine art photographer whose work is represented by ClampArt in New York, Hackelbury in London, and numerous galleries across the country and in Europe. His work is part of various museum collections including the Vatican Museum; the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum; the Houston Museum of Fine Arts; and the Bibliothèque National de France. Armstrong also teaches at the International Center of Photography and the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

REGISTRATION DEADLINE EXTENDED! Please register by Thursday, March 11.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Register here

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Bill Armstrong: The Secrets of Color in Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 10, 2016

Lee Miller: A Woman’s War

From the London Blitz to Hitler’s apartment, Lee Miller, once a muse to the Surrealists, captured some of the most audacious images of World War II.

By Isabel Stevens

Lee Miller, Fire Masks, Downshire Hill, London, England, 1941 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

Late in life, when people asked about the beginnings of her career, Lee Miller would answer, “I used to take a few photographs.” It’s hard to believe this was the same woman—a former Condé Nast model—who doorstepped Man Ray and demanded he teach her everything about photography, and who, as a burgeoning photojournalist, refused to return home to the United States when World War II broke out in Europe, choosing instead to push toward the front lines. Miller was one of the first photographers to uncover the horrors of the concentration camps. In war zones, she carried a Rolliflex and a brass knuckle-duster engraved with her name.

Previous Miller retrospectives—notably The Art of Lee Miller, presented in 2007 at the V&A Museum—have repositioned her reputation as a singular photographer, not just an intriguing muse and a body that Man Ray, Jean Cocteau, and Roland Penrose fractured into sensuous, strange pieces. What’s novel about Lee Miller: A Woman’s War, currently on view at the Imperial War Museum in London, is the exhibition’s focus on Miller as an artist who interrogated a woman’s place in the world before, during, and after the war. No doubt her own career mirrored those of many Englishwomen she captured, for example, who worked during the war: there was a burst of opportunity, followed by disappointment. In Miller’s case, this experience was compounded by depression; she was forever haunted by what she had witnessed in Europe.

Lee Miller, Lady Mary Dunn and young evacuee, Buckinghamshire, England, 1941 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

Instead of Miller’s more surreal, well known visions, A Woman’s War includes her photo-critiques of relationships between men and women in artistic circles. Images of bohemian gatherings in the 1930s feature clothed male Surrealists and their naked lovers. Husbands loom possessively over their wives. This is the work of a model-turned-artist who starts to question the world around her: Miller was tired by the domineering nature of her lover Man Ray, and as an artist, she longed to be released from working in his shadow. Throughout her short career, as this exhibition demonstrates, Miller also brought many pioneering female artists into the spotlight, and made a point of emphasizing their creativity. She photographed the filmmaker Jill Craigie watching over a scene, and the writer Martha Gelhorn with a pen in her hand. Later, in 1946, Miller made a searing Surrealist critique: a portrait that pits a giant Max Ernst against a tiny, marionette-like Dorothea Tanning.

Despite bringing some Surrealist flair to the practice of shooting wartime fashion, Miller’s images for British Vogue from the 1930s appear inert when compared with what came next. After female conscription was introduced, in 1941, she began to document women on the home front: factory workers, mechanics, pilots, nurses, land girls, and Wrens, all going about their daily business. A bizarre parade of unnerving objects such as surgical gloves, parachutes, and gas masks also made their way into the pages of Britain’s fashion bible. Fortunately for Miller, her commercial career coincided with the appointment of Audrey Withers as editor of British Vogue. Withers cared little for frocks or hats, and she was responsible for commissioning some of the magazine’s most daring visual reportage.

Lee Miller, Two German women sitting on a park bench surrounded by destroyed buildings, Cologne, Germany, 1945 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

In July 1944, Miller was allowed to join the Allied forces liberating Western Europe. She spent the next year and a half roaming the continent and documenting the aftermath of Nazi rule, singling out female victims and perpetrators in particular and questioning whether, in wartime, anyone could truly be an innocent onlooker. Her images of nurses working on the front line, concentration camp prostitutes, and lone women refugees with their children, are vital records of war her male colleagues didn’t or wouldn’t seek out; they are also among the most extraordinary images Miller ever created. Rather subversively, clothes play an important role in her dispatches for Vogue, whether it’s the traditional German dress a local girl wears for an enforced tour of Buchenwald, or the immaculate nurse’s uniform a Nazi teenager has chosen for her suicide. The only disappointment of A Woman’s War is that more of Miller’s own writings aren’t displayed alongside her images—impressionistic and searing first-person accounts, which proved Miller to be the rare photojournalist who is as competent a master of prose as images.

Lee Miller with David E. Scherman, Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, Hitler’s apartment, Munich, Germany, 1945 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

Miller’s photographs often meet the gaze of her subjects with subtle precision, herself included. Together with the photographer David E. Scherman, Miller was the first person to enter Hitler’s Munich apartment as American forces were liberating the city. It was only natural that Miller, an Aryan beauty if there ever was one, composed an uncanny spectacle with herself at the center. Naked in Hitler’s bath and clasping his washcloth, her muddy boots soiling the Fürher’s pristine white bathmat, she performs for the camera on her own terms. In this shocking tableau, her stare is intimate—and defiant.

Isabel Stevens writes about photography and film for Sight & Sound, Apollo, Frieze and the Guardian.

Lee Miller: A Woman’s War is on view at the Imperial War Museum in London through April 24, 2016.

The post Lee Miller: A Woman’s War appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 9, 2016

Into Eden: A Conversation with Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques

Ahead of his commission for Aperture, the French photographer previews a new project exploring the mythologies of real estate.

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, Untitled 02, 2013, from the series Standards & Poors

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, the first artist recipient of Immersion: A French American Photography Commission, created by the Hermès Foundation and the Aperture Foundation, has found himself a piece of Eden—specifically, a little red schoolhouse located in Eden, North Carolina (population 15,527). Having purchased the house with funds from the award, granted in 2015, Couzinet-Jacques has used it to initiate a series of explorations of small-town USA and the mythologies of the American dream. The work he is producing incorporates photographs made in Eden, research materials from the local historical archives, and scans of items found on-site or of portions of the house itself, as well as the work of invited artists such as Ugo Schiavi, Thomas Hauser, and Fred Cave, each of whom visited the schoolhouse in Eden for brief working stints over the past six months—mini residencies within Couzinet-Jacques’s own residency.

In this way, the schoolhouse has become a site for making and showcasing work, as well as the putative subject of the work itself. Each activity may help uncover or express a new facet of the house, its history, and that of the community in which it’s located. Couzinet-Jacques maintains that his interest is in exploring these issues, while simultaneously looking at photography as one means among many of imprinting and translating reality into visual form. Abstaining from the classic American road trip, Couzinet-Jacques has instead embedded in one place. As he puts it, “I prefer to see the landscape moving through the windows of the living room rather than just from the windows of the car.” The work created during this manifold experience will be exhibited at Aperture Gallery in New York in November 2016. Couzinet-Jacques recently sat down with Lesley A. Martin, Creative Director of the Aperture Foundation, to offer a sneak peek at the project.

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, The Little Red Schoolhouse, ca. 1905. Courtesy the artist and Eden Historical Museum

Lesley A. Martin: Sylvain, tell us a little bit about your background as an artist and as a photographer. You first graduated from the master’s program at the art school in Marseille, ESADMM (2010), and subsequently from the L’École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles (2012). Your work is decidedly interdisciplinary, drawing on different methods of presentation and image making. Where did you begin?

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques: I used to be a painter—or to be more precise, I guess I used to paint, almost fifteen years ago, and I had a studio at that time. It was a gift—somebody lent me a studio to work and paint. After two years, the person took back the studio. I was like, “Okay, where I can paint?” I bought a camera to photograph nudes for my next paintings. At first it was just for taking notes, but then photography became more central. I have always considered the photographic act to exist at the intersection of figurative ways of being in the world and poetic and abstract ones.

Martin: The Eden project seems to be a continuation of some ideas you explored in your series Standards & Poors, both in the topics you’re focusing on, and in a multidisciplinary approach to those topics.

Couzinet-Jacques: Standards & Poors is a series I made in 2013, in Spain. It’s about the financial crisis, which of course was directly linked to the housing market and real estate crisis. My new project, Eden, is also linked to real estate. I wanted to invest in a cheap house, possibly a foreclosed house, to change the way one might consider it. I want to change an object that is linked to “bad things”—bad, recent history—and make it something very new and different. I’m interested in real estate as it modifies a way of living.

Martin: Meaning, how we construct our lives through the landscape?

Couzinet-Jacques: Absolutely. It’s more than just an observation. I try to totally involve myself in a project as a way of living. Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is a text that has haunted me for years and I wanted a similar experience—to live someplace for several months and to try to document it from inside. I wanted to talk about a house from inside the house, like a circle. So I bought a house. It’s the first public school of Eden—the classic little red schoolhouse. I wanted to work in a house in order to give some dimensionality to my photography, and then I discovered that the house was built in 1884, the same year that Kodak received its first patent on photographic film, a way to put the real world into a single, flat dimension. I’m going to use the house as a walk-in art space, a lab for pictures, screen-printing, and sculpture. I’m interested in the subject of the house itself, its materials. And I’m very interested in how life can be close to art, directly part of art.

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, Untitled 04, 2013, from the series Standards & Poors

Martin: Is that also why, for example, in your installation of Standards & Poors, you used UV light, which has a direct impact on skin?

Couzinet-Jacques: Yes. I wanted the public to be a witness, exactly as I had been on those sites. It was a way to allow the viewer to feel this light that is quite beautiful and very magical in a way, but also unsafe.

I had been invited by Le Bal, in Paris, to create a body of work that would talk about what is happening in Spain, and also reflect on what contemporary documentary photography is. At Le Bal, there were two types of pictures: “normal” images, and those that required viewing through tinted glass. The prints were almost entirely black-and-white, but colors were introduced during the framing via tinted glass. During the exhibition, the UV lights destroyed some of the prints I had made; but at the same time, other images were protected by the coloration. One part of the exhibition was destroyed, and one part was resistant to the light and the environment. (Viewers were also warned that prolonged exposure to the exhibition could cause burns.) This was a somewhat ironic way to talk about the crisis in Spain—a landscape in crisis. Ghost cities. Buildings that were new and old at the same time. Future ruins.

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, The Little Red Schoolhouse (Red version), 2015

Martin: You have an unusual way of working with color as an overlay or as an added element to the picture.

Couzinet-Jacques: I think about a picture as a pictorial process. That’s why I use layers and weird colors sometimes, although I start out with traditional film. The layering is also a link to a conceptual part. Pictures themselves are not the reality, so there is a layer between the real and the way you can express it.

Martin: Your practice seems very material-based. It’s not just pictures on the wall, as you were describing. It’s quite sculptural.

Couzinet-Jacques: Well, you know what Ad Reinhardt said: “Sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.” But what is interesting in photography is that it’s linked to real things. It’s quite straight. The price to pay is that the image itself can be too plain and too perpendicular to talk about real things on its own.

Martin: Too perpendicular? Perpendicular to what?

Couzinet-Jacques: A photograph is square and flat. Sculpture or an installation allows for more dimension to talk about feelings, surfaces, and objects. I try to create an enchantment, to transform the subject, to deviate from the “straightness” of the photography medium.

Martin: But, you mentioned showing your work at Le Bal, which focuses primarily on documentary photography. Do you consider yourself a documentary photographer? Are your reference points in photography documentary photographers, or art photographers?

Couzinet-Jacques: I like that photography is linked to something that exists, but how you compose something, the decision you make when you press a button, this becomes a mix of the political, the social, and the poetic. Poetry and politics are part of the documentary. I’m very interested in the American documentary school, starting with Walker Evans. They are my “mentors.” But I don’t want to do the same things. I try to find my own grammar, my own language. Probably it’s a kind of remix in a way.

Sylvain Couzinet-Jacques, Untitled, Eden, 2015. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs © and courtesy the artist

Martin: I think so much of contemporary photography is sort of “Photography Plus”—photography plus sculpture, photography plus painting. It seems like you’re also drawing on tools from other mediums as you need them.

Couzinet-Jacques: I try to be free with that. I’m very interested in other works that are not linked to photography—contemporary art; art generally. I would say that I use photography as a default setting. I use it because its strength is to link people directly to the social and political. Probably the greatest, most beautiful poetry is ultimately concrete in form. I don’t know if I will still be a photographer in ten years, but I will always work with images.