Aperture's Blog, page 142

March 8, 2016

An Outsider in Rio

From Kurt Klagsbrunn, a midcentury vision of Brazil’s most photogenic city.

By Alexandra Pechman

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Dama acompanhando a corrida no Jockey Clube, Rio de Janeiro, 1945

Kurt Klagsbrunn documented the life of Rio de Janeiro with an outsider’s sense of awe. A Jewish Austrian refugee, he arrived in the city in 1940 and photographed its people and places until 1960, the year the government decamped for Brasília. As noted in the title of this recent exhibition at the Museu de Arte do Rio—Kurt Klagsbrunn, um fotógrafo humanista no Rio (1940–1960)—he was a humanist photographer, and subscribed to no specific viewpoint in his images of celebration and demonstration, hard labor and elite leisure. He used dozens of cameras, some of which were on display here, celebrating the city as often as lambasting it, at times doing both at once. The presentation was part of the FotoRio 2015 program as well as a series at the Museu de Arte do Rio to celebrate the city’s 450th anniversary. Klagsbrunn seems a worthy, lesser-known subject through which to explore the city’s particular midcentury moment: it was a haven to refugees during World War II during its twilight as capital city, not long after which many artists, including Klagsbrunn, were expelled by the dictatorship.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Engraxate na Cinelândia, ao fundo o Palácio Monroe, Rio de Janeiro, 1940s

Klagsbrunn’s family escaped Nazi-occupied Austria, securing passage through Lisbon to Brazil (the exhibition is organized in part by his niece and nephew). The exhibition begins with early photographs he took in Europe: contemplative, obscured scenes of 1930s Austria, followed by melancholy pictures of Lisbon, of his father at a window or a boat leaving the port, as hands at shore wave scarfs leaving ghostly trails. This darkened and brief prelude makes way for a platform that gives view to a huge curved screen, on which are projected beaches, sloping rock formations, sweeping views of the bay—offering an entrance into Rio much like the photographer’s own. (Unfortunately, some of the projected images appear somewhat stretched.) The wall text, which describes Klagsbrunn’s arrival in the city in 1940, could just as easily have been an exclamation point.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Pausa para o café, Minas-Gerai, 1947

Klagsbrunn wasted no time: he took no less than 100,000 photographs of his new city. The austerity of his early pictures quickly gives way to crowded street scenes with a focus on character, whether a trolley fish seller, a carnival samba dancer, or a Carioca walking her dog in Copacabana. A chic young journalist eyes the camera suspiciously as a two white-coated waiters dote on her; a grisly greengrocer looks on tiredly from inside his shop. The exhibition includes clippings from the newspaper column in which many of the images originally appeared, “O que o turista nota no Rio” (What the tourist notices in Rio). An opposite wall illustrates how Klagsbrunn’s appreciation extended to the sloping lines of the city’s then recent deco architecture—his few forays into abstraction. His frame is more often frenetically clasped around action: the slope of a boardwalk, fitted so it almost bulges out of the frame, or a simple scene of men taking their coffee, so crammed with detail it appears a shade away from chaos. Paradoxes occur often, as in pictures of the mobilization of forces in World War II: graceful ballet dancers in white are surrounded by a gray mass of soldiers; in a group of dozens of nurses, a woman on the bottom right gives a dubious smirk. The photographer’s own off-kilter sense of humor is never out of sight.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Baile de carnaaval no Teatro Municipal, Traje permitido fantasia ou à rigor, Rio de Janeiro, 1949

The show honored his outlook, gathering a wealth of material in support of the photographs, including clippings as well as lenses, cameras, and numerous carefully maintained photography books and manuals. Klagsbrunn’s photographs can at times lapse into a postcard-version Rio—most of the work he published appeared as editorial work in glossy magazines. But he had plenty of other, more democratic subjects that he tirelessly pursued: he documented the working class and the black culture of the city in detail, particularly dance subcultures such as capoeira and gafieira. Across from his published photographs of the famous and elite, from Niemeyer to Eva Perón to carnival banquets to jockey clubs, were his images of football games, favela life, and sambistas—which today define the culture of the city.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Gafieira, Rio de Janeiro, 1948. All images courtesy Museu de Arte do Rio

The exhibition closed with a heavy-handed message about Rio’s rise and fall in the twentieth century: two images hang side by side, one of a 1950s protest in the city center, the other of a tour group from a few years later, at a clinical distance from the space-age severity of Niemeyer’s new capital buildings in Brasília. It’s a point not overtly made until the exhibition’s end—and draws out a guiding principle from Klagsbrunn’s encyclopedic output. Only then do we see Klagsbrunn didn’t just photograph a bygone city, but was perhaps obsessively trying to preserve the one that belonged more to its people than to bureaucracy.

Alexandra Pechman is a writer currently based in Rio de Janeiro.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, a humanist photographer in Rio (1940–1960) was presented at the Museu de Arte do Rio from April 14, 2015–January 31, 2016.

The post An Outsider in Rio appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Nothing Personal

At the Art Institute of Chicago, three artists provoke timely questions about race and sexuality.

By Faye Gleisser

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #12, 1978. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Nothing Personal exposes viewers to intimate moments, sounds, and photographic evidence of personal experiences, both imagined and real. The potential connections on offer within this exhibition, which opened in January 2016 at the Art Institute of Chicago, are rich and timely. Three dynamic projects by three leading American artists—Cindy Sherman, Zoe Leonard, and Lorna Simpson—provide viewers with the chance to examine, as the curators propose, how “the passage from personhood to persona” sits firmly at the intersection of canonical photography, conceptual art, and gender theory. But an evasive stance on class, race, and historical narratives prevents Nothing Personal from inciting the fullest possible conversation about identity, which these provocative works clearly demand.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993–96 (detail) © and courtesy the artist; Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and Hauser & Wirth, New York

The superstar checklist of Nothing Personal includes six of Sherman’s black-and-white Untitled Film Stills, produced between 1977 and 1980; Leonard’s The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96), a fabricated archive of a fictional 1930s African American queer starlet, which Leonard made for the filmmaker Cheryl Dunye’s movie The Watermelon Woman; and Simpson’s two-channel video installation Corridor (2003), which uses a split-screen format to portray an African American woman—played by the artist Wangechi Mutu—simultaneously undertaking daily routines as a servant or slave in the mid-nineteenth century and as a wealthy homeowner in the mid-twentieth century.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993–96. Installation view by Geoffrey Clements, Whitney Biennial 1997 © and courtesy the artist; Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and Hauser & Wirth, New York

To be sure, Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills series, in which the photographer enacts various female prototypes from the housewife to the B-movie Hollywood star, is considered one of the most influential works in heralding a feminist critique of the masculine gaze, while also recalibrating the strategies of appropriation and reference in portraiture. In the 1990s, alternatively, Leonard’s eighty-two touch-worn photographs, accompanied by typeset biographical captions, exemplified the turn toward institutional critique that pressed viewers to confront the reality of systemic racial, gendered, sexual-orientation, and class-based exclusions. The action of making oneself up links Sherman’s and Leonard’s photographs to the characters appearing in Simpson’s Corridor and their collapsed labor of self-presentation and the tidiness of interior spaces. Like Mutu’s actions of applying makeup or bathing in Corridor, the typewritten captions in Leonard’s archive, full of intentional typos, capture a process of imperfection, of making or becoming that all three works examine.

Lorna Simpson, Corridor (detail), 2003 © and courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

A number of distressing evasions, however, characterize Nothing Personal. The central impulse about that “passage from personhood to persona” fails to take up the links of whose personhood and whose personas remain concertedly effaced. Nothing Personal should have opened a critical space in which to reconsider how the similar actions of inventing and reinventing oneself—as an artist and as a woman in American society—are in fact motivated by different sets of racial, sexual, and class-based exclusions. Instead, the exhibition flattens the most significant points of revision that might have been illustrated by viewing these artists side by side. Not only are the institutionalized social barriers that catalyzed each artwork made by women about women’s experiences of commodification unremarked upon in the exhibition’s didactic text, there is surprisingly no mention of the explicitly political photo-literary book (1964), created by Richard Avedon and James Baldwin, despite it being the seeming inspiration for the exhibition’s title. Perhaps the hedging of these concerns in the exhibition arises from a pervasive institutional anxiety about the place and role of identity in museums, as well as a self-conscious motivation for the show itself: Leonard’s piece, as noted by the exhibition label, is an “acquisition consideration,” as if this installation were a rehearsal and Fae Richards, ironically, auditioning for yet another role.

Lorna Simpson, Corridor (detail), 2003 © and courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Despite its shortcomings, the main conceit raised by Nothing Personal remains critically salient: the show asks that we consider how collecting and consuming images is tied to protecting and maintaining our cultural fictions. Additionally, the brevity of context given by Nothing Personal reminds us that the work of making significant connections between fraught histories cannot be left to speculative meditation. Displaying histories of exclusion and erasure, however painful and deep-seated, in a manner that represents both the violence and potential of representation, is surely how art museums critically engaged with the politics of identity today will remain relevant tomorrow.

Faye Gleisser, a PhD candidate at Northwestern University in the Department of Art History, is the Marjorie Susman Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.

Nothing Personal is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through May 1, 2016.

The post Nothing Personal appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 4, 2016

Recap of Connect Member Meetup

Pixy Liao, presenting artist and Brent Beamon, director of Flowers Gallery

Lesley A. Martin, Aperture creative director

Allegra Favila, Brent Beamon, Pixy Liao, Rebecca Reeve, and Shen Wei

On February 26, Aperture Connect Members came together for a private after-hours meet-up at Flowers Gallery in Chelsea, New York, to hear from Brooklyn-based artist Pixy Yijun Liao about Experimental Relationship, her body of work featured in the exhibition The Real Thing.

Brent Beamon, director of Flowers Gallery, led the exhibition tour, which also includes work by Juno Calypso, Natasha Caruana, and Melanie Willhide. Yijun Liao discussed with Connect Members her process of inverting traditional relationship roles in various domestic scenes of herself and her younger lover. Members participated in an informal Q&A before continuing on to Toro for cocktails with Liao and Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation.

Aperture Connect is comprised of young professionals who are photography and publishing enthusiasts, ages 21 to 37. A Connect membership offers year-round opportunities for supporters to engage with each other and with practitioners and artists in the fields of publishing and photography. Join as a Connect Member today and receive invitations to exclusive events like this one.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming.

The post Recap of Connect Member Meetup appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 1, 2016

Sales and Distribution Changes

Today, Aperture is pleased to announce two changes we’re making in our sales and distribution structure, in a planned effort to grow our book sales in North America:

First, we’ve hired Richard Gregg to take on the new role of ‘Sales Director, Books’, to lead our future book sales growth, directly, and working with our distributors. Richard brings extensive experience and contacts with him, having worked for the last four years as Director of Retail Operations for the ICA, in Boston, and prior to that, for seven years for Phaidon Press, in various roles including Business Development Manager. We’re thrilled to have him on board.

Secondly, we will be changing our North American book distribution arrangements, moving from DAP to Ingram, at the end of July.

Alongside their wholesale division, Ingram provides publisher services to Taschen, Ammo, Actar and Granta, among many others, and offer us new opportunities to improve our sales in the USA and Canada. We’re very excited to start work with them as our distribution partners.

For the last decade, Aperture’s books have been distributed by DAP (and continue to be, until the end of July). The team at DAP is incredible, and we sincerely appreciate everything they have done for Aperture. We wouldn’t be where we are now, without them. We will sincerely miss working with them, and shall continue to recommend them highly to other art publishers.

There will be no change in how bookstores order Aperture books until August 1st.

Chris Boot, Executive Director

The post Sales and Distribution Changes appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Armory Africa Focus Preview: A Conversation with François-Xavier Gbré

François-Xavier Gbré, Swimming pool III, Bamako, 2009. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Working in France and West Africa, François-Xavier Gbré studies the ruins of industry, modernist architecture, and national memorials. Here, the Ivorian photographer, whose latest work will be featured in the Armory Show’s Focus: African Perspectives, speaks with Peter Barberie, the Brodsky Curator of Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Peter Barberie: You have photographed ruined modernist buildings in both Europe and Africa. How are these disparate sites connected for you? It seems to me that your photographs capture the aspirations of these buildings, as well as their failings.

François-Xavier Gbré: I grew up in the north of France, an area that used to be an industrial center. In the 1970s and ’80s, the region was in decline and abandoned factories surrounded us. The aesthetic became familiar and it came out in my work. The Unilever factory in Haubourdin and Poyaud in Surgères were both built in the early twentieth century. The modernist architecture was a symbol of rapid technological advancement and modernization of society. European architects naturally exported their model during the colonial time and after. In my work, I look for bridges between Europe and Africa. I try to document the complex relationship between North and South. Even if these buildings were constructed for different reasons, they often share the same fate (for different reasons, too).

François-Xavier Gbré, Unilever II, Haubourdin, France, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Barberie: Your photographs of the Imprimerie Nationale, in Porto Novo, Benin, are especially moving to me. When I visited Rencontres de Bamako–The African Biennale of Photography in November 2015, I encountered several conversations about the loss of modern African archives, so it seems to me that the history of several African nations is at stake in these pictures. Were you thinking about archives when you made these views?

Gbré: All of the chapters of my series Tracks (2009–2015) aim to acknowledge the past. In this way, I make an archive. The Imprimerie Nationale (National Printing Factory) is more particular because I documented a place in charge of the official documentation of an African state. And the conclusion is sad. This chapter of my work includes both a question and an answer: Why don’t we have a better understanding or recognition of African history? Because African archives are in a mediocre state.

François-Xavier Gbré, Piscine #1, Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Cocody, Abidjan, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Barberie: I am curious about swimming pools as a recurring motif for you. I think this tells us about an important element in your work. You approach these sites with an eye that is both critical and optimistic.

Gbré: As a child, I used to go to the public swimming pool and it made my day. And I still love it. After showing my work about the swimming pool in Bamako, many friendly people wanted to introduce me to other pools, but I didn’t have any particular interest in it because I was not making an inventory. I use that motif because it can tell a lot about the society. In Bamako, I question the construction and the succession. The absence of water implies the idea of death. In Abidjan, the pool is filled, but it appears very quiet, despite the fact that it’s located on the university campus. Why there is such a silence? What are people waiting for? What are people dreaming of?

François-Xavier Gbré, Général Abdoulaye Soumaré, Avenue des Armées, Sotuba, Bamako, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Barberie: Your photographs of the sculptures on the Avenue des Armées in Bamako grapple with a more brutal topic, military might. The sculptures look small in your pictures, which dwell upon the unfinished state and questionable impact of this triumphal avenue. To some degree you treat the place with comedy. During Rencontres de Bamako you exhibited large cutout prints of some of the sculptures in a space next to Bla Bla Bar, one of the key meeting points in the city. The way you installed and lit the pictures was incredible: they looked like remnants of sculpture from the Parthenon. The comedy was gone, replaced by pathos and menace. In the past you have installed wallpaper prints in several locations, including Bla Bla. Was this the first time you exhibited prints that were shaped and melded into the setting?

François-Xavier Gbré, Installation view from the series Mali Militari, Hippodrome, Rencontres de Bamako, October 2015. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Gbré: In 2013, I discovered this new part of the Bla Bla when I was still living in Bamako, and since the first look I wanted to do something in it. In October 2015, I came back to Bamako with a “precise” project in mind and I was very surprised when I found that place totally changed: almost all the walls were destroyed. That pushed me to experiment with a new way of showing my work in order to fit the original idea of the project. The idea was to build my own square by bringing sculptures from one area of Bamako to another. I wanted to translocate the statues from an open space to a closed one, creating a more intimate reading of the work. I wanted to concentrate the several architectural elements from Avenue des Armées in order to share the experience and the feelings I had when taking the photographs years before. By repeating and multiplying the sculptures, playing with their size in the installation, I could make the message more impressive or aggressive. The lighting also played an important role by night. Finally, the fact that the original place was destroyed facilitated the dialogue between the location and the artworks because now they would share the same aesthetic of construction and destruction. It was the first time I worked in that way. The surprise makes the work in situ more exciting to me.

François-Xavier Gbré, Baie de Mermoz II, Dakar, Senegal, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, Abidjan

Barberie: Your photograph Baie de Mermoz II gives us an expansive view foregrounded by a construction site where work seems to have just begun. This composition, like many of your others, has real elegance. I’ve never been to Dakar, so I googled “Baie de Mermoz” to learn more about the place. The top results were all about real estate!

Gbré: This photograph deals with how the private space imposes itself with force into the public landscape. I see art as an act of showing a political or social issue in its most beautiful dress.

François-Xavier Gbré’s work will be on view at the Armory Focus: African Perspectives in New York from March 3–6, 2016.

The post Armory Africa Focus Preview: A Conversation with François-Xavier Gbré appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 29, 2016

Armory Africa Focus Preview: A Conversation with Namsa Leuba

Namsa Leuba’s worlds are colorful configurations, detailed and evocative. Her photographs take the viewer to the farthest reaches of glamour—an unapologetic glamour, especially since she orchestrates the picturing of alluring black bodies and positions them inside “Western aesthetic choices,” to use her formulation. For a Swiss-Guinean artist, a Western gaze might be inescapable, but so is the beauty of her sets, costumes, and fashionable Nigerian models. Bodies, in most of her work, become amenable, draped and painted over, embellished and ennobled. In Ya Kala Ben, the exorcising rituals of a Guinean village are depicted with the appeal and mystery of a performance. In The African Queens and Cocktail, Leuba’s models are positioned against resplendent backgrounds, costumed luxuriantly while they bend, kneel, crouch, or stand. I spoke with Leuba about her most recent work in advance of her presentation at the Armory Show’s Focus: African Perspectives. —Emmanuel Iduma

Namsa Leuba, Sarah, from the series NGL, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Emmanuel Iduma: I’d like us to begin with geography. This year, the Armory show has invited fourteen galleries across the continent to participate in special section of the fair. Your work will come to New York courtesy of Art Twenty One, a gallery based in Lagos. You’re Swiss-Guinean, represented by a Nigerian gallery, and you’ll be shown in New York’s premier international art fair. What are your thoughts about the movement of your work in this way?

Namsa Leuba: I feel quite lucky to be represented by my gallery in this event. For me, it’s interesting that I was born in Switzerland but always grew up with African culture and Africans around me. My mother is from Guinea and I always went there as a child. I think I feel much better when I’m there than in Switzerland. It’s totally different, because when I’m in Africa, I study other perspectives. Everywhere I go I feel at home, because there’s very special interest. Even though the cultures are totally different—in Nigeria, Guinea, and South Africa—there’s something unique.

I think my work has a place in New York, since all of my work is focused on African identity through Western eyes. Why is it through Western eyes? Because I was born and educated in the West. I studied in Swiss schools (a bachelor’s in photography and a master’s in art direction) and at the School of Visual Arts in New York (the Photo Global program). I can’t say through African eyes, since that depends on your education, which informs your outlook on the world. My cousin who lives in Guinea will have another perspective and outlook on creativity, art, photography.

Namsa Leuba, Damien, from the series NGL, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Iduma: Are you making new work for the Armory presentation?

Leuba: Yes. I’m very excited about it. Last year I spent a month in Lagos, from July to August 2015. I was in a residency at my gallery, Art Twenty One. We’re going to show a part of my new work.

Iduma: Which is from Lagos?

Leuba: Yes, it’s from Lagos. I worked with Nigerian fashion designers—such as TZar, Tokyo James, Re Bahia, I Am Isigo, Deco, Maxivive—and I used their clothes for my pictures.

Namsa Leuba, Kenny, from the series NGL, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Iduma: Is this a continuation of your research on African identity through Western eyes?

Leuba: Of course, but in a different way. And I’m also going to show Zulu Kids (2014), which I did two years ago.

Iduma: Could you talk about your preoccupations with this new work?

Leuba: The title is New Generation Lagos (NGL), which is a play on the letters “NG,” since it could also mean Nigeria. I wanted to do something a little different, more related to fashion, although it’s art. I’m at the borderline, similar to what I did with The African Queens (2012), or Cocktail (2012). So there’s a lot of color. This time I made portraits of people, of their faces. Some of the pictures can be a little bit psychedelic as well.

Namsa Leuba, Layo, from the series NGL, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Iduma: In your photographs, I get the sense that color isn’t merely a technical choice, particularly because you often construct environments for your subjects. What do you have in mind when you’re assembling colors for the costumes and when you’re choosing what to photograph?

Leuba: You know, when I was making Ya Kala Ben (2011), a lot of people said there was something related to fashion stylistically. For all of my work, I try to bring the models inside Western aesthetic choices, even the models for the work I make in Africa. I like to play with colors because they bring a different sensation to the pictures. People play with different patterns, layers, colors in South Africa, Guinea, Nigeria, Morocco. I like that. It gives some volume.

Iduma: Tell me more about what you mean by “Western aesthetic choices.”

Leuba: The codes and symbols of culture and society are different in Europe. In the West, people who come to look at my pictures would like to look at them with comfort. Most of the time the viewer stays on the surface. But in Guinea people see different parameters, and sometimes there are violent reactions because they see my work as a sacrilege. While making Ya Kala Ben, I was arrested by the police!

Namsa Leuba, Damien II, from the series NGL, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Art Twenty One, Lagos

Iduma: How do you work with your subjects?

Leuba: For all my artwork I do my casting on the streets. I prefer to work with unprofessional people. This is important, because of all the people you’re going to see in NGL, there’s only one or two who are professional models, who came to my casting and said they’d like to pose for me. Otherwise I like to work with people on the street. This is what happened in Nigeria, as in all of my work. I like to be in contact with people. There is a long and very interesting process of exchange that I like.

Emmanuel Iduma, a Nigerian writer and art critic, is the author of the novel Farad (2012) and co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing (2014). He co-founded Saraba magazine , and is the managing editor of The Trans-African .

Namsa Leuba’s work will be on view at the 2016 Armory Focus: African Perspectives in New York from March 3–6, 2016 .

The post Armory Africa Focus Preview: A Conversation with Namsa Leuba appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 26, 2016

New Yorker Photo Department Instagram Takeover

Past Aperture Portfolio Prize winner, Bryan Schumaat (2013) and runner-up, Marueen Drennan (2009) have each had the opportunity to take over the New Yorker photo department Instagram account during the past two weeks. Schutmaat’s takeover will end February 28. Check it here.

The post New Yorker Photo Department Instagram Takeover appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 25, 2016

2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Bill Durgin, Adrien with Mosaic, 2015; from the series Studio Fantasy

Eli Durst, Asmara Stadium, 2015; from the series In Asmara

Sean Thomas Foulkes, Composite #12, Syria, 2014; from the series Fragments of Engagement

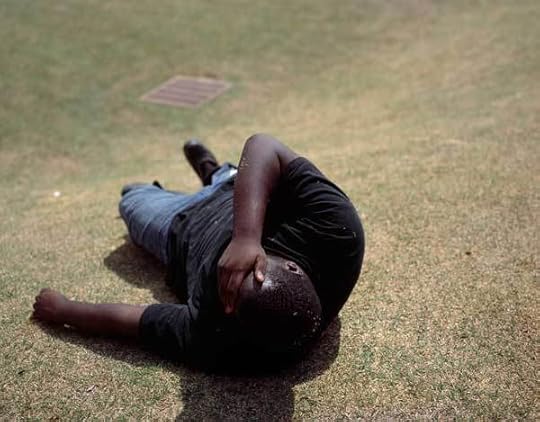

RaMell Ross, Antonio; from the series South County, AL

We’re pleased to announce the four finalists for the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an international photography competition whose goal is to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, Aperture’s editorial and limited-edition print staff reviewed more than five hundred portfolios. Our challenge is to select one winner and three honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. Out of the following exceptional finalists, one will be selected as the winner of the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize, receiving a cash prize and exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York:

Bill Durgin

Eli Durst

Sean Thomas Foulkes

RaMell Ross

The winner of the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced in late March. The finalists’ portfolios and statements will be available here on aperture.org. In the meantime, check out last year’s winner, Drew Nikonowicz, and the three runners up.

The post 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 23, 2016

Black Lives, Silver Screen: Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young in Conversation

As the United States navigates a political moment defined by the close of the Obama era and the rise of #BlackLivesMatter activism, in May 2016 Aperture magazine will release “Vision & Justice,” a special issue guest edited by Sarah Lewis, the distinguished author and art historian, addressing the role of photography in the African American experience. This week, as a preview of “Vision & Justice,” we are publishing three articles online, including the conversation below between the groundbreaking filmmakers Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young, who speak about diversity and inclusion in Hollywood—now a national conversation—and why black lives must be visible on the silver screen. To learn more about “Vision & Justice,” click here to read an introduction by Sarah Lewis.

David Oyelowo and Carmen Ejogo in Selma, 2014. Courtesy Paramount Pictures/Jima

Director Ava DuVernay is on a mission. With her films I Will Follow (2010), Middle of Nowhere (2012), and the critically acclaimed Selma (2014), about Martin Luther King, Jr., she has created cinematic worlds distinguished by deft character studies and nuanced subtexts. One of the only African-American female directors to helm a major Hollywood picture, DuVernay realized early in her career the importance of telling stories as yet untold. In Selma, she portrayed a King of stirring complexity. “We unencased him from marble,” she remarked when the film was released. “We really made him breathe and live as any man would, in his kitchen, telling his wife he’s about to go on a long trip.” In this conversation with her frequent collaborator Bradford Young, two enterprising filmmakers discuss the significance of the black cinematic image. Young, the visionary cinematographer and director of photography, has a distinguished profile in contemporary cinema, enriching the inner lives of on-screen characters with an uncommon range of visual emotions in films like Pariah (2011), Dee Rees’s striking, coming-of-age portrait of a young New York lesbian, and Mother of George (2013), Andrew Dosunmu’s sumptuously colorful drama about Nigerians living in Brooklyn. Here, DuVernay and Young speak at length about their collaborations and inspirations.

Ava DuVernay: I don’t really know what we’re talking about. I just came out of casting and writers room and my head is swimming with other things, so literally, I’m super taking your lead.

Bradford Young: I was going to take your lead! Oh, we’re in trouble.

DuVernay: Let’s get it on track. I think we’re supposed to talk about black imagery, black images … Don’t laugh! Let’s start with Haile Gerima. Shall we?

Young: And the importance of image making and our collaboration specifically. And why should we even care about the possibility of what an image can look like within the context of a black film.

DuVernay: I think my mind can’t help but go to Haile, because today our distribution collective ARRAY announced the acquisition of his film Ashes and Embers (1982) and I’m so proud of that. And he is your teacher, all of our teachers, and such a foundation in your work, and an inspiration for our work together. Now, I feel some kind of way about trying to re-present Ashes and Embers in theaters and other platforms for the first time since its making in the early ’80s. Truly too many have forgotten about that particular work of his, and the film community I don’t think is acknowledging him for the very reason you just said. Because there is no true value placed, outside of the value that we place on our own. No true value placed on the black image as it relates to cinema at large.

Young: I think Haile Gerima is the catalyst and the counterpoint really for our whole conversation. Haile has taught us so much in direct and indirect ways. I discovered knowledge of myself, who I am, what my purpose is on the earth—it comes from me being with Haile for the past twenty years of my life. In particular, Ashes and Embers was the one film that changed not only what I think film can stand for but also what the film experience can be. Ashes and Embers set the bar for me. It was that fine line between realism as it relates to black life and realism as it relates to black life in film, but it was also willing to be experimental and imaginative at the same time. The imagination part of his films isn’t just magical realism. It’s not just imagination or experimentation just for imagination’s or experimentation’s sake. When he wants to convey the psychological decay of the main character, he hangs the camera from a tree and spins it. There’s so much loaded in that. That’s about black men being lynched. It’s about black men ultimately lynching themselves, the black body sort of being lynched in real time by the forces that be. But it’s also in order to put us in the shoes of the person who’s hanging from the tree; he actually hangs the camera from the tree. That way of making films is the beginning of why I even care about the way a film looks, or the potential of what a film can look like.

DuVernay: Yes, yes!

DuVernay and Young on the set of Selma, 2014. Courtesy Paramount Pictures/Jima

Young: But on many levels, I’m so curious to hear from you, Miss Ava DuVernay, a growing artist in the film context. Your life’s calling is about the transformative, revolutionary power of cinema. You’ve taken on a mandate to make film that truly communicates the revolutionary potential of human beings. I’d be curious to hear why you think the image is important in our evolutionary and revolutionary process as black people in the world and within the American context. What makes you feel like image is such a significant element in our development?

DuVernay: Goodness gracious, Bradford. That’s an easy question. Let me just rattle off a quick answer. Ha! The image is intimate to me. We use the term our mind’s eye for a reason. The images that we consume and that we take in, they can nourish us, they cannot malnourish us. They become a part of our DNA in some way. They become a part of our mind, our memory.

Young: Right.

DuVernay: It’s in our internal camera. The image. This idea of the image is so much more dense than even using it in a film context. It’s an intimacy inside your own memory, inside your own mind.

We see the world and each other in pictures. That’s why I think film is so emotional. It’s re-creating what’s already embedded in our internal process. It’s an artificial rendering of what’s already going on inside. I think that, for whatever reason, that is why I’ve always been drawn to it, and as you start to apply theories of progression and liberation and all of those things around very intimate ideas, it becomes even more powerful.

But that’s why I’m so excited when I see your images as a cinematographer. Because I know inherent in that image, there is an idea becoming a part of someone’s mental canvas. You drink it in, and that’s now part of you. That’s why what you do is so important, I think, divorced of story. You’re telling your own story within the image that’s sometimes not even attached to the narrative that it’s inside of. Does that make sense?

Young: Yes. As you’re saying that, I’m tapping my foot on the ground. I might actually want to scream and run around the room. As your director of photography, I’m supposed to manage expectations. You say to me, “I want the film to feel this way visually,” and then I have to go pull all these people together to determine how we’re going to make your wishes come true. How we’re going to manifest what you said, this sort of internal image-making capacity that’s innate to all of us. For the last two years I’ve been thinking about images, but as an image maker I’ve actually never heard anybody describe it like that. Now you’ve got me thinking, Wow, I’ve got to really be careful with whom I collaborate, because the director is essentially the person in this context who is going to help me unlock the box.

Danai Gurira in Mother of George, 2013. Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

DuVernay: That’s not easy. We work in a place that is set up to, that is crafted to do exactly the opposite of that. Our objectives, our intention as black movie makers, as a black woman movie director—there’s nothing in this industry, when we work inside of the industry, that fosters that. I think that’s why I hold on for dear life for the collaborations, the moments that exist outside of this industry, because that’s where we both started—outside of the industry.

Young: Right.

DuVernay: You represent a weird conundrum for me in that regard because you represent the moments where I’ve felt the most free, independently making films outside of the industry like Middle of Nowhere (2012). And also the moments when I first took a step inside of that industry with Selma (2014) and tried to create something intentional in an environment that was a lot less free. That’s what I’m wrestling with. The films are not going to reach who you want the way you want if you don’t participate in this industry somehow. I know that to be true. I grew up in Compton, and you can’t see Straight Outta Compton (2015) in Compton because there ain’t no movie theater there. You can’t see Selma in Selma because there ain’t no movie theater there for that black community. You know what I mean? There’s this cinema segregation that happens that ain’t nobody seen Ashes and Embers, the film that they should see! Why?! Because it ain’t coming to a theater near you, because it wasn’t made inside this paradigm. I struggle with that. How have you navigated it? Because you’re doing it quite well.

Emayatzy Corinealdi in Middle of Nowhere, 2012. Courtesy ARRAY

Young: Sometimes it’s hard for me to see if I’m navigating it well. The installation work and things I’ve done specifically, let’s say, with Leslie Hewitt have become really important in my process. At the same time, I do think there is a disharmony between what I expect from the filmmaking experience and what it is I am actually getting out of all the experience that I’m having outside of the community that actually raised me. You know what I’m saying?

DuVernay: Mmm hmm. Yeah.

Young: It’s not like jazz or hip-hop—art forms that started as expressions of dissonance and resistance. Filmmaking isn’t part of our organic narrative as black people in America. We’re asking people who were very much interested in making sure film communicated white supremacist values, like the founding fathers of the film experience—D. W. Griffith, Thomas Edison, these people who were very interested in white supremacy—we’re asking the sort of grandchildren of those people to allow us into the filmmaking experience with a whole counterpoint to why they started it. You know what I mean? It didn’t start off as an art form of resistance. Actually what you said earlier is the real purpose of why we do this. It’s like trying to etch in real time our mind’s camera, our mind’s image-making capacity. It generates images so that we can deal with life. So the way I navigate it, I think, is that I’ve just got to stay focused on the possibility that one day it could be completely turned over on its head and transformed.

Still from Selma, 2014. Courtesy Paramount Pictures/Jima

DuVernay: Those words are moving. As you were talking, a conversation that I had with Ryan Coogler came to mind. We were looking at the statistics that just came out from the Directors Guild of America about super-disturbing numbers that really starkly lay out the omission and the absence and the disappearing of voices other than white men in the guild, or the industry or whatever. It went by year and by studio, by gender and by race. It was like, one woman director at Paramount in 2015, two people of color directors at Warner Bros. in 2013–14, etcetera. We were trippin’ out, because he rightly remarked, “That one at that studio in that year is you, and I’m one of the two in this year.” So we were talking about those numbers; they might as well have had our names on it. We are the numbers on the chart at this moment. Ain’t nobody else around. Like, who are we looking for? Ain’t nobody coming to help us. Know what I mean? There’s one person in that column and it’s you and you’re standing there next to one other person at another studio in the other year and that’s your homie. So how do you reconcile being part of a larger industry, a larger energy that’s making a certain thing when you lay the numbers out and we literally are standing alone amongst a lot of opposition, misunderstanding, purposeful omission, all of that.

Even more so, I thought, Oh, well, Ryan, at least he’s got five other black men with him as small as that is. There’s two of us. Women. Two black American women who’ve made studio movies in 2014. There’s me and Gina Prince-Bythewood. I thought, Well, we’ve got it really bad! And then, do you know who I started to think of?

Young: Who?

DuVernay: You! Because you ain’t got none. The past five years, it would be one. It would be Brad. Not even one other black cinematographer who’s getting air and room to breathe in the studio framework. Just one. You. What is that like? When you can say, you are a creative entity that has it worse than the black woman filmmaker! That’s rough, cause we got it bad! Ha! It’s the black cinematographer. That’s so sparse that there’s only one guy doing it on a certain level. You truly stand alone in this moment. I know it’s not a badge of honor. That’s a badge of disappointment for all of us that there’s not more. But surely, that’s where you are. And what’s going on with that?

Young: You know what’s bittersweet about it? The sweet part of it is all of the elders around me, Ernest Dickerson, Malik Sayeed, Arthur Jafa, and Johnny Simmons. It’s not like I’m really alone. But things do happen when you’re alone. There’s a certain dissonance that comes from being alone. Know what I mean?

DuVernay: Yes.

Danai Gurira in Mother of George, 2013. Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

Young: I’m just one cell in a mass of what we need to do to feel human in our experience of being black in the world. Obviously, there’s Shawn Peters. There’s Chayse Irvin. There are cats that are coming up. But at the same time, I do feel lonely, because I still want to be able to pick up the phone and call the other cinematographer who’s working consistently within projects, the same kind of level of projects I’m working on, and say, “Hey, what was it like for you?” I still have to go back to Haile.

Listen, I’m like the seventh black person to ever be let into the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC). The seventh. Out of a body of more than three hundred people. According to the history of the organization, they don’t let us in all the time, and when they let us in, we’ve got to really check how we celebrate that.

These images, these things I’m helping to provide, come from a very complicated, joyful, but very painful experience of often being the only person in the conversation.

DuVernay: You were talking about ASC. Same situation with the Academy. Having a moment that you look around and it’s not even a deep dive to understand the context. It’s so stark, it’s laid so bare right there. How much can you celebrate? It’s a residue of all that is not. All that is not. All that never was. All that is absent. It sits right on top of whatever little moment that is. But that’s such an interesting way to think about your place in all of this, and it’s really fascinating to hear how you’re reconciling it, both in your work and just personally.

Young: Everything we just talked about is why you and I are together. It is why we’re doing what we’re doing together. We’re aware of what’s happening around us.

DuVernay: Yeah, for sure. Yes, indeed. Okay, they want us to talk about that work. Our work together. I’ll throw out the name. You can tell them what we did. The first was My Mic Sounds Nice (2010). It was a documentary that was the first documentary that BET ever commissioned as an original doc. It was about women in hip-hop and the art form of emceeing, and women. I’d reached out to you because I had seen Mississippi Damned (2009). Tina Mabry, great filmmaker, who is now working with me, blessedly, on my new TV show project—writing and directing with me. I’d seen her film and loved it, which you shot. I reached out to you about I Will Follow (2010) and you couldn’t do it because you were shooting the great filmmaker Dee Rees’s project Pariah (2011). I didn’t know you from Adam. It was just a cold call.

Omari Hardwick and Emayatzy Corinealdi in Middle of Nowhere, 2012. Courtesy ARRAY

Young: That’s right. First of all, everybody had been talking about you. So when you asked me and I said I couldn’t, I was hoping and anticipating at some point that you would call again and we would do something together. When it finally came that time when we were actually going to do My Mic Sounds Nice, it was abundantly clear from the beginning that whatever we were going to do, we were going to try to push it. We were going to try to make it not just seeing these beautiful sisters on a screen talking about their experience. It was also going to be about how people were going to experience it visually.

So we met in Atlanta. Before we even went to shoot, we sat on these couches in the hotel where we were staying, and we had a more than an hour long conversation about what our expectations were and are about cinema. I hadn’t had that experience before. We talked about Haile. You were bringing up films that I had never seen. I just realized, like, Oh, this is my sister. This is my friend. This is a person I haven’t met, but we’ve been on the same path, the same journey. The only thing that was separating us was land, was space.

DuVernay: You’re taking me back to that couch, that bad faux postmodern couch where this collaboration was born. Ha! It was a real organic, beautiful, deeply rooted conversation in this totally false, like fabricated environment.

We went out into Atlanta and we shot. I remember it was the second day or the first day and I still have these people in my head. We saw some young brothers in the street skating. There was a girl with them. Do you remember this? I said, “Look at them; they’re so beautiful.” I always regret that we never went back and shot them. She was so beautiful. They were just some skater kids. You said something like, “Look at them, they’re free,” and then we started talking about a story, like, “Wow, we should have talked with them.” Anyway, I think of them now and then. Memory. The mind’s eye. I can see that moment that I looked over at them in my head still. Do you remember?

Young: I do. They were three skater kids, three black skater kids, in an abandoned parking lot. Two brothers and a girl in East Point, Georgia. We’d just come out of that raw food restaurant, feeling good. Feeling good!

David Oyelowo and Emayatzy Corinealdi in Middle of Nowhere, 2012. Courtesy ARRAY

DuVernay: Yeah! Yes! Middle of Nowhere was our next collaboration. You were already a star. You’d already won Best Cinematography at Sundance for Pariah, or it was coming up. These things that the industry marks as worthy. But we already knew. I remember being glad that you were doing it, because I think at that point you had different choices about what you could do. Different possible trajectories and different people pulling on you different ways. The talent was apparent at that point. Enough of us had seen the work, and were valuing it. So anyway, it was no money. It was fourteen days in LA, in South Central and all around LA. Yeah, what did we do then?

Young: We were at a place to exercise some of the ideas that we think about. Like, how do you capture black life in real time? We’d already talked Ashes and Embers. We already had those references. Now it was time to show up and be part of that conversation.

Gabrielle Union in The Door, 2013. Photo: Brigitte Lacombe

DuVernay: After, we did a branded piece, The Door (2013), commissioned by Prada. They basically just gave a chunk of change to tell a story, as long as the characters were wearing their clothes. I was like, “let’s see … ok.” And we made something … I love that piece. I think we said something with it.

Told a story that I thought was important. Everyone looks like you just want to sop them up on a biscuit. We walked into that with very little prep. Very little prep. I remember being in that house like, “ok, let’s have her stand over there; let’s have her stand by the painting; let’s get her by the painting, I might use it.” By that point, we’d already done Middle and Mic and we had a shorthand. I just remember feeling super free. Even though the client was on the set looking at it, it felt super free and very connected. What did you think?

Young: Yes. It was basically an experiment to see if we could do something more free and do something commercial, sell a product. I hadn’t shot many commercials and you hadn’t shot many either. It was beautiful to improv with you. I’m so proud of that piece. I think this is what we do when we come together. We try to bring all the conversations we have when we’re not shooting movies together or shooting commercials together.

Gabrielle Union in The Door, 2013. Photo: Brigitte Lacombe

DuVernay: There’s no one who can reach into my brain and make the image a reality, that mind’s eye into a real thing, better than you. You make it even better than I even thought of it.

Then Selma was next. Truly, on Selma was the first time I felt like I knew what I was doing at all. I had made five documentaries, two narrative films, shot an episode of Scandal, done the Prada thing, done a couple of other branded pieces —and with all those I felt not entirely comfortable within myself, if I’m honest.

So it was on Selma that I was super clear. From work with the actors, to my work on the script, to my work with you on camera, to work with the set design, the locations, production design.

Whatever my strengths were, and weaknesses, I feel like they all evened out and I had accepted my limits and my strengths and wasn’t beating myself up over either. It’s certainly not done but I felt like I was at least stepping into a sphere where I could say, Oh, I understand. I haven’t mastered any of it but I understand what I want my place to be.

DuVernay and Young on the set of Selma, 2014. Courtesy Paramount Pictures/Jima

Young: You had so much swagger on Selma. It was unbelievable. Working with you on that film has changed not just the way I look at you as a director, but the way I look at you as a woman, as a person, as a human being. It was evident and clear from the time that you showed me those Paul Fusco photographs to the point we went into the battle. You were like, “This is what I want, and it’s got to happen.” I was just watching everybody, including myself, line up and meet the challenge.

DuVernay: We couldn’t have done it without each other. Nor would I have wanted to.

Young: I feel the same.

DuVernay: So as we wrap up this almost conversation for some people who are listening, and they’re like, What the hell are they talking about?

Young: Ha!

DuVernay: I just have to thank you for being my partner. I just want to thank you. Because before the image itself, it’s the experience of making the image. The audience gets the image. We get the experience of making the image, too. And those experiences when I’ve worked with you have been real gifts. So thank you, my brother. I love you.

Young: I love you, A. I always say, I’ve been standing with Haile for twenty years, and I’ve watched a lot of cats, brothers, and sisters come in and out of his space. But you are the first person that I brought to meet the brother. We all love you. We adore you. We look up to you right now. You’re so real. And people got to know that. I hope people who read this know that. Man, the way you’re navigating this space—we’re watching you. We’re learning. Because you bring a lot of dignity—forgive me, I’m getting emotional—you bring a lot of dignity to a space where I don’t see dignity. I know we all have our capacity to go down that road. But you? You are relentless. And you make us so proud. That’s why I don’t want to waste your time. Even my wife is like, “Do not waste Ava’s time. She’s on a mission.”

DuVernay: I’m happy to be on it with you, Brad.

This article will appear in Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice,” to be published on May 24, 2016. Subscribe to Aperture today and never miss an issue.

The post Black Lives, Silver Screen: Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young in Conversation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Vision & Justice: Guest Editor’s Note

As the United States navigates a political moment defined by the close of the Obama era and the rise of #BlackLivesMatter activism, in May 2016 Aperture magazine will release “Vision & Justice,” a special issue guest edited by Sarah Lewis, the distinguished author and art historian, addressing the role of photography in the African American experience. Here is a preview.

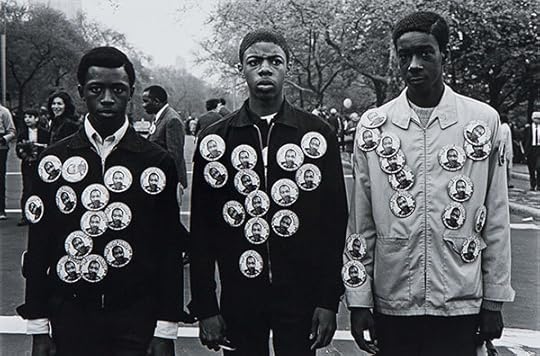

Benedict Fernandez, Memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr., Central Park, New York, 1968. Courtesy Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

By Sarah Lewis

In 1926, my grandfather was expelled in the eleventh grade in New York City for asking where African-Americans were in the history books. He refused to accept what the teacher told him, that African-Americans had done nothing to merit inclusion. He was expelled for his so-called impertinence. His pride was so wounded that he never went back to high school. Instead, he went on to become a jazz musician and a painter, inserting images of African-Americans in scenes where he thought they should—and knew they did—exist. The endeavor to affirm the dignity of human life cannot be waged without pictures, without representational justice. This, he knew.

American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice.

When I was asked to guest edit this special issue devoted to photography of the black experience—the first of its kind for Aperture—I could think of no other theme. No matter the topic—beauty, family, politics, power—the quest for a legacy of photographic representation of African-Americans has been about these two things. The centuries-long effort to craft an image to pay honor to the full humanity of black life is a corrective task for which photography and cinema have been central, even indispensable.

Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil. Today, we’ve been able to witness injustices in a firsthand way on a massive scale that would have been unimaginable decades ago. We have had to ask ourselves questions that call upon powers of visual analysis to read, for example, the image of Eric Garner’s killing, virally disseminated through social media, or to understand the symbolism in Dylann Roof’s self-styled portraiture before his killing of the Emanuel 9 in Charleston. Being an engaged citizen requires grappling with pictures, and knowing their historical context with, at times, near art-historical precision. Yet it is the artist who knows what images need to be seen to affect change and alter history, to shine a spotlight in ways that will result in sustained attention. The ongoing focus that comes from the power of the images presented in these pages—from artists such as Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young, Deborah Willis and Jamel Shabazz, to Lorna Simpson and LaToya Ruby Frazier—move us from merely seeing to holding an enduring, penetrating gaze long enough that we consider what is before us anew.

This issue takes its conceptual inspiration from the abolitionist and great nineteenth-century thinker Frederick Douglass, who understood this long ago. In a Civil War speech, “Pictures and Progress,” Douglass spoke about the transformative power of pictures to affect a new vision for the nation. This issue opens with that historic framework—Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s writing on Douglass’s prophetic, probing ideas and theories about the medium of photography at the dawn of the photographic age. Douglass, the most photographed American man in the nineteenth century, argued that combat might end complete sectional disunion, but America’s progress would require pictures because of the images they conjure in one’s imagination.

We come closer to understanding Douglass’s vision of justice with the generation of imaginative photographers and artists represented by projects in this issue, from Leslie Hewitt’s and Lorna Simpson’s assemblages of archival pictures that speak to the complex legacies of the civil rights movement to Awol Erizku’s stylish studio portraits, in which he appropriates iconic poses of Old Master paintings. We see it in the photographs of Roy DeCarava, Carrie Mae Weems, Frank Stewart, and Jamel Shabazz, who never lets us forget the dignity of black life, and in those of Deborah Willis, who has also long chronicled the history of the field. We are fortunate to have writing in this issue by a wide range of scholars, artists, and writers—including Teju Cole, Margo Jefferson, Claudia Rankine, Robin Kelsey, Cheryl Finley, and Leigh Raiford, alongside historians Nell Painter and Khalil Gibran Muhammad and musicians Wynton Marsalis and Jason Moran—who offer invaluable insights about the significance of this relationship between art and citizenship exemplified by the works selected for this issue.

Douglass in Cedar Hill Study, ca. 1880s. Courtesy the National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

This issue, published in the last year of the Obama presidency, is a time of unparalleled visibility for an African-American family on the world stage. Yet this era must also be defined by the emergence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the stagnated wages of working-class citizens, and growing impatience with mass incarceration. Devin Allen, a young photographer who came to national attention through his prolific Instagram feed, chronicled the unrest in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody. Suddenly the streets of 2015 looked like memories of 1968. Radcliffe “Ruddy” Roye, who has propelled the classic genre of street photography into the age of social media, asks, in his continuous stream of images, how we should imagine dignity in the face of oppression. Catalyzed by events just over fifty years apart, Dawoud Bey’s powerful meditation on the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Alabama and Deana Lawson’s portrait series on the families of victims killed in 2015 at Mother Emanuel in Charleston, South Carolina, speak to the legacy of the African-American church as a target for terrorism and a refuge of grace.

We often see the nexus of vision and justice as a retrospective exercise, chronicling the recent past. We saw this most notably with what I would call Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “aesthetic funerals”: the urge after his death to visually unfurl images, ideas, epic visions of African-American culture as if to secure the horizon line that felt suddenly in doubt. We saw it in Benedict J. Fernandez’s photograph taken on April 5, 1968, of three young boys with their torsos covered in buttons of King’s Poor People’s Campaign, as if they were laying out the body of King across their own. At the time of year when Fernandez took this photograph, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was planning an exhibition called Harlem on My Mind to open in 1969, which used the visual poetics of an unfurling, a spreading out of an archive, to show the development of Harlem. As Bridget R. Cooks describes in this issue, Harlem on My Mind was designed as a tour of Harlem, a processional through thirteen chronologically ordered gallery displays of photographs, dominated by James VanDerZee. It also had a most unusual feature: a closed-circuit television showing exhibition visitors at the Metropolitan real-time footage of pedestrians passing on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue. The now nearly unimaginable feature of a camera displaying Harlem as a distant culture from that of the Upper East Side still offers a vivid reminder—art is often the way to cross the gulf that separates us.

What does it take to work toward representational justice? In this issue, we are fortunate to have answers through a frank discussion between the trailblazing filmmaker Ava DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young and an interview with a pioneer of film, Haile Gerima, followed by Carla Williams’s reflections on the role of the groundbreaking, 1970s-era Black Photographers Annual for the development of this photographic field. What did it mean for African-American photographers to create this journal dedicated to fine-art photography, given that more visible magazines, including this one, rarely included work by African-American photographers? That short-lived publication would pave the way for historians such as Deborah Willis, among others, who have devoted their careers to elevating the life stories and images of African-American photographers, whose immeasurable contributions to the medium are only just becoming widely recognized.

Saturated with images, we now live in a world where the power of an image is alternatively so self-evident, so common, that it is easily dismissed. Douglass was writing at a time when it could not be forgotten. As I wrote in The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery, it was a modernist vision at the dawn of the age of photography that might take decades, if not a century or more, to be made clear.

How many movements began when an aesthetic encounter indelibly changed our past perceptions of the world? It was an abolitionist print, not logical argument, which dealt the final blow to the legalization of the slave trade—the broadside Description of a Slave Ship (1789). The London print of the British slave ship Brookes showed the dehumanizing statistical visualization with graphic precision—how the legally permitted 454 men, women, and children might be accommodated by treating humans as more base than commodities (though the ship Brookes carried many more, up to 740). The image it conjured in the mind was intolerable enough to help abolish the institution; the broadside served in parliamentary hearings as the evidentiary proof of slavery’s inhumanity.

How many went to Selma because they were moved by images of injustice on their television? How many, like Brown v. Board of Education constitutional lawyer Charles L. Black, Jr., saw that segregation was wrong after being moved by the power of an artist, in this case the “genius” of the trumpet playing of Louis Armstrong? Armstrong’s genius, Black would state, “opened my eyes wide, and put to me a choice”: to keep to a small view of humanity or to embrace a more expanded vision. Once Black made the choice, he never turned back. This is what aesthetic force can do—create a clear line forward, and an alternate route to choose. Later Black would say that, in many ways, this was the day he began “walking toward the Brown case, where I belonged.” Black never forgot it. He held an annual Armstrong listening night at Columbia and Yale, where he would go on to teach constitutional law, to honor the power of art in the field of justice and the man who caused him to have an inner, life-changing shift.

The gravity of this connection between vision and justice is crucial to understand as we live in a polarized climate in the United States; sociologists tell us that people now congregate, live, worship, play, and learn with those like themselves more than ever before. Save for constructed societies, we come into close contact with those who do not share our political and religious views less and less. How we remain connected depends on the function of pictures—increasingly the way that we process worlds unlike our own. The tool we marshal to cross our gulf is irrevocably altered vision. The imagination inspired by aesthetic encounters can get us to the point of benevolent surrender, making way for a new version of our collective selves.

Shortly after my grandfather died, I went back to the house where he lived in Virginia, the white clapboard structure nearly ready to sink back into the earth. I stood in that pass-through chamber off of the dining room where he painted. The dining room looked empty, absent the paintings and drawings we’d often splay out on the table as if nourishment of an essential kind. Guest editing this issue of Aperture has brought me to that moment again, mindful of my very personal commitment to the artists, writers, playwrights, and filmmakers who, like my grandfather, see this inextricable nexus between race, art, and citizenship. I dedicate this issue to my grandfather’s memory and to all those who are working tirelessly to honor the full spectrum of human life.

Sarah Lewis, guest editor of Aperture’s Vision & Justice issue, is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University and the author of The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery (2014).

This article will appear in Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice,” to be published on May 24, 2016. Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice: Guest Editor’s Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers