Aperture's Blog, page 140

April 29, 2016

The Pleasure of the Image: A Conversation with Isaac Julien

Isaac Julien, Mise en Scene No. 2, Looking for Langston (Vintage series), 1989/2016. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

One of the most innovative artists of his generation, Isaac Julien rose to prominence in the late 1980s with the debut of his film Looking for Langston (1989), a lyrical meditation on the poet Langston Hughes. Looking for Langston, made collaboratively with the photographer Sunil Gupta and the cinematographer Nina Kellgren, is set in the atmospheric, reimagined world of Harlem in the 1920s. Evoking Hughes as a queer icon, Julien pushed expressions of black male desire into visual culture through what he calls the “aesthetics of reparation”—the creation of a space where images of different identities and races can exist and flourish. Here, Julien speaks about returning to his early work in Vintage, an exhibition of photographs that recently opened at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco.

Isaac Julien, Film Noir Angels, 1989. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Brendan Wattenberg: For Vintage, why did you decide to turn back to your earlier film and video work in the form of still images?

Isaac Julien: A lot of this emanates from working on my MoMA catalogue, Riot (2013), which comes out of the work I’ve been undertaking in my studio. In the mid-2000s, we began looking at my archive and trying to get that into order. That’s where the first interest began in showing the Langston photographs. That felt like a work that was kind of important to resurrect because it had just been gathering dust in the vault!

Wattenberg: In the exhibition, there are two scales for the prints.

Julien: Yes, these prints are showing two different kinds of photographic techniques—traditional gelatin-silver prints and larger-scale photographs, which are closer to the original cinematic experience of looking at the film. I wanted to make some larger-scale works from the series because, of course, new technology allows one to do that! I’ve been making photographic works in Germany, at Grieger in Düsseldorf—and I see the influence of that “New German Photography” school in my own practice. But, the Looking for Langston images were always meant to be images, which were shot both on Super 16mm film and on 35mm black-and-white film. All of the images made for both technologies were made to be seen at a large scale. There’s my premise.

Isaac Julien, Homage Noir, 1989. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Wattenberg: Let’s go back to the origins of photography and the image for you. I’m thinking about the photographers you’ve mentioned, both in your MoMA catalogue and with regard to this exhibition: James VanDerZee, George Platt Lynes, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Were these the photographers you had in mind in the early part of your career? Or specifically when you set out to make Looking for Langston?

Julien: I know there’s a new documentary on Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, which I saw at the Berlin film festival, and it reminded me that my thesis, when I was at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, was focused very much around Robert Mapplethorpe’s work. The thing I was trying to do, in the early ’80s, was to look for images that resonated with me. When I saw VanDerZee’s work, for example, I just knew it was very important in terms of vernacular of African American photography and black culture generally. So, it was when I was making Looking for Langston, when I was concentrating on the theme of the Harlem Renaissance, that my encounter with photography—with American photography, and with black-and-white photography in particular—became very important.

Wattenberg: Robert Mapplethorpe is having a moment right now. Do you still feel a strong connection to his work?

Julien: I see a return to Mapplethorpe, and indeed a return to analog techniques in photography, as a kind of recourse to the way in which digital technologies have become “over-spectralized” to such an extent. We’re completely intoxicated by images. So, there’s that return. But certainly thirty years has passed, and that creates enough critical distance where you can look at a photographer like Mapplethorpe anew. It’s very much about periodization and the shift that time affords and enables you to have a different gaze upon works of his kind.

Isaac Julien, Pas-de-Deux, from Looking for Langston (Vintage series), 1989/2016. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Wattenberg: Do you see Looking for Langston in a genealogy of American portraiture?

Julien: Absolutely. That really comes out in the work. In Looking for Langston, it’s George Platt Lynes and black-and-white photography, which creates a kind of “cocktail”—VanDerZee is the strong aesthetic signature to the work. There are also all the other references—cinematic references to say film noir, or to the expressionism which belonged to German cinema, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—that intersect the work. For all intents and purposes, the series in Vintage belong to a film set. So it’s also the lighting of Nina Kellgren, who shot the film, and the apparatus that cinema brings to the image, and the way you have to think about the black-and-white image in particular.

Wattenberg: What was the nature of your collaboration with Sunil Gupta on Looking for Langston?

Julien: The nature of the work was similar to working with Nina. I’m always looking to make work with people who are technicians, but in the case of Nina, she studied sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art, she made black-and-white photography, and she taught photography. Sunil is a photographer himself. I was in dialogue with both artists when I was making Looking for Langston as they were performing and working and shooting the film. And to some extent, I carry that practice on to this day. But, I would say, in Sunil’s work, we were interested in the way that he was pushing certain questions around gender and sexual identity, in the same way that I was, in Sankofa Film and Video and the Black Audio Film Collective. We have a lot of friendships from those days, which were committed to lots of different struggles that were taking place, especially around the AIDS crisis and the decolonization of queer culture, which was very much attacked by Thatcherite forces. There was a common bond that we had.

Isaac Julien, Trussed series, 1996. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Wattenberg: Could you explain what you mean by “aesthetics of reparation”?

Julien: When we’re thinking about the industries of film and photography, we know that we’re dealing with a technology that is particularly non-neutral in the way in which black subjects, specifically, have been treated. Not only by the technologies themselves, which were aligned to lighter skin tones, but we know that the rules of representation—and the technologies of representation—have to be rewritten if you want to articulate a certain aesthetic. So, I always view the making of works as an act of reparation, aesthetically. It’s the undoing of a very forceful regime of dominant effects, which are quite a bombardment for any person of color growing up or being part of a generally dominant white culture, particularly in the photographic and cinematic industries. Making work is about how one can produce the aesthetics of representation, which is about creating and sustaining spaces for different images to exist of black subjects, of queer subjects, of working class subjects. In the work of Langston Hughes, for example, I see a strong sense of the aesthetics of representation. His work is very much about looking at black life and the aesthetics that get drawn out, such as in VanDerZee’s Harlem Book of the Dead, a photographic book which I looked at very closely in the making of Looking for Langston. In some senses, I’m looking to recreate a certain mise-en-scène, which had an inspiration from those photographic images and from black modernism.

Wattenberg: You mentioned that you’re still working on your archive. But Riot contains a great quantity of photographs—it is an archive, in it’s own way. There are many pictures of the artists and intellectuals who surrounded you as you were making the works we’ve just discussed. Are you still thinking about another book project on your archives?

Julien: I’ve wanted to do a book on Looking for Langston. But, I think it would be fantastic to do a book just on the photographic side of my work, which of course includes lots of collaborators, such as Sunil Gupta, and also all the people I worked with on my films, such as Nina Kellgren. My work is rooted in photography. In the Vintage exhibition, that’s one of the things I’m trying to bring to the forefront.

Brendan Wattenberg is the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

Vintage is on view at Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, through June 11, 2016.

The post The Pleasure of the Image: A Conversation with Isaac Julien appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 25, 2016

The Architecture of Desire

In her recent videos and installations, Amie Siegel navigates the threshold of art and commerce.

By Sabrina Mandanici

Amie Siegel, Circuit, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

The word “ricochet” describes a moving object—such as a bullet—which, when hitting a surface, fails to penetrate it, and instead rebounds at an angle. It’s appropriate that Amie Siegel’s first large-scale survey exhibition in Germany, Double Negative, is presented as part of Ricochet, the exhibition series at Munich’s Villa Stuck, a museum housed in the former mansion of German fin-de-siècle painter Franz von Stuck. Like a ricocheting object, the power of Siegel’s works comes at you tangentially and strikes with unexpected force.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Siegel’s seven works on view—in video, film, and photography—provide thorough insight into an artistic practice often considered an “interrogation of cinematic tropes.” Double Negative also reflects on, plays with, and undermines the narrative and formal strategies of visual storytelling and its media, as well as the iconography of the moving image. Yet that would discount, even ignore, the precise curating of Yara Sonseca Mas and Siegel herself and their nimble use of the villa’s challenging, ornately decorated, rooms. Over the course of the exhibition, each of Siegel’s works gradually resonates with one another to reveal their Janus-like nature.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Rich and multi-layered in aesthetic and content, Siegel’s art observes the social and economic patterns that form and influence our relationship with object and image, architecture and archive. A meticulous image maker, precise in her framing and construction of thought-provoking tableaus, she questions our often-fetishistic habit to assign myths to material objects and thereby establishes both personal meaning and commercial value. Siegel illustrates this instinct explicitly in Provenance (2013), the first piece on view.

Amie Siegel, Provenance, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

As the title implies, Provenance, a 40-minute HD video traces an object’s history, in this case the global trade of collectible designer furniture, mainly chairs and stools, to their origin at Chandigarh—the controversial 1950s modernist city in India, conceived by Swiss architect Le Corbusier—all the way down to its furniture. In reverse chronology, the video’s slow, opening tracking shots of upscale Western residences—the furniture’s present settings—proceed backward through auction previews and sales, photo studios, restorers’ workshops, shipping containers, and finally into Chandigarh’s office complexes, where the furniture originated.

Amie Siegel, Provenance, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Siegel’s complex power of observation lies not in offering judgment, but in a seemingly objective, almost passive presentation, a strategy of indirect disclosure. Provenance, however, has been unjustly criticized for its high-end aesthetics, and for obscuring details about locations, dealers, and collectors, and particularly for exploiting the insular logic of the art market. After the first exhibition of Provenance in New York, Siegel later auctioned off an edition of the video at Christie’s in London—and filmed the entire process. The result, Lot 248 (2013), retelling the preview and auctioning of Provenance, and Proof (Christie’s 19 October, 2013) (2013), a framed printer’s proof of the auction catalogue’s page for the Provenance lot, are also exhibited in Munich. Taken together, the entanglement of Provenance with the art market is merely a feint to decode something else: following our desire to possess or belong, objects become actors—or surrogates.

Amie Siegel, The Modernists, 2010. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

A more intimate and humorous facet is present in The Modernists (2010), scenes from vernacular photographs and Super 8 films, made by a couple from the 1960s to the ’80s, who traveled to the world’s major museums and iconic art sites and posed with famous sculptures. Displayed in the villa’s remarkable former bathroom (with fragments of an antique frieze affixed to its walls), it subtly prompts questions about class, about economic power and the accessibility of culture, and the shifting status of souvenirs—from historic objects to photographic performance.

Amie Siegel, The Modernists, 2010. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Berlin Remake (2005) is a double-projection of scenes from films by the former East German State Film Studio, juxtaposed with her present-day “remade” versions. Deathstar/Todesstern (2006), five screens of slow-motion shots traveling through hallways of early German modernist buildings, constructed or appropriated by the country’s totalitarian regime, are loops that viewers can enter into at any point. Devoid of narrative, with no explicitly theatrical motivation or plot, they prompt viewers to confront the uncanny, somewhat menacing, architecture itself, and thereby reveal how our reaction is directed, if not manipulated by, the camera.

Amie Siegel, Berlin Remake, 2005. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

The nexus of this exhibition’s cross-referential net is Double Negative (2016), a new two-part work commissioned by the museum. Two facing, 16mm films simultaneously project images of Le Corbusier’s all-white Villa Savoye, now a museum near Paris, and its all-black “replica” in Australia, which houses an aboriginal archive. As both films are projected from negative stock, our notions of original and copy, of black and white, are confused, and we are left to find our own answers of intent and meaning. The second part, a color video of the interior of the Australian archive, shows, in a melancholic tone, its ongoing digitization of ethnographic films and aboriginal cult objects.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York. All installation photographs by Jann Averwerser

The questions ricocheting from Double Negative are what make this exhibition so satisfying, as well as its confrontation of our relationship to objects that surround us, and the importance we assign to them. Perceptive and self-reflexive, Amie Siegel skillfully navigates the threshold between art and economics—between the human impulse to leave a mark, or to own it.

Sabrina Mandanici is a writer and an Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung Fellow in the program “Museum Curator for Photography.” She currently lives in Germany.

Amie Siegel: Double Negative is on view at Villa Stuck, Munich, through June 5, 2016. Amie Siegel: The Spear in the Stone is on view at Simon Preston Gallery, New York, from May 1 to June 19, 2016.

The post The Architecture of Desire appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 21, 2016

At San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, a New Frontier for Photography

Snøhetta expansion of the new SFMOMA, opening May 14, 2016 © Henrik Kam. Courtesy SFMOMA

When SFMOMA reopens next month, the new Pritzker Center for Photography will become the largest photography showcase in an American art museum. The center will have double the original gallery space and new, state-of-the-art educational and storage facilities. At the heart of one of the nation’s leading fine art institutions, photography will take center stage. Glen Helfand recently spoke with senior curator Sandra Phillips about the Pritzker Center and upcoming exhibitions at SFMOMA.

Glen Helfand: How much discussion was there about the importance of photography as a medium in terms of its prime location in the museum?

Sandra Phillips: There’s a considerable group of Trustees who are committed to photography. I know that photography was something that SFMOMA director Neal Benezra and the Trustees were eager to present in an important and focused way in the enlarged museum, and it’s something we’ve stood for since the museum was founded in the 1930s. We have been very photography-oriented because it’s been our important community, both historically and now.

Lewis Baltz, Claremont, 1973 © Estate of Lewis Baltz. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What exactly is the Pritzker Center for Photography?

Phillips: It comprises the old galleries in the Botta Building that now showcase the permanent collection. It includes the Photography Interpretation Galleries, which will also include a coffee bar. And it includes the Temporary Exhibition galleries for photography, where we will present our own shows and those from other institutions. Finally it will also include the collection itself, the study room, a classroom, and two offices.

Helfand: What aspects are you most excited about?

Phillips: I think the whole thing as a unit, which unites the study of the original objects in the study room with work being shown in the galleries, together with an in-depth concentration on our permanent collection and a creative use of it. It will enable us to bring in more shows from other institutions. We will also be developing our archives and making all that accessible. The whole thing is like a dream come true.

Seiichi Furuya, Izu, 1978, from the series Portrait of Christine, 1978 © Seiichi Furuya. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What’s in the Photography Interpretive Gallery?

Phillips: There will be exhibits about aspects of the collection presented digitally. In the opening program one will feature examples of California photography in our collection, one of our strengths. It will present a kind of roadmap where you can figure out what pictures of Yosemite or Los Angeles we have. There will also be educational games to help people understand how photography actually works, for instance, a way to make a photogram with your cell phone to understand photographic process and photographic ideas. Then there’s access to other aspects of our collection, like films on and interviews with photographers whose work we own. We just went to Japan and interviewed ten photographers who we will be showing in the second permanent collection exhibition. These will be edited and put up online, and also available in the gallery, so you can see what these photographers have to say about their work when you see the show.

Stephen Shore, Market Street, San Francisco, California, September 4, 1974, 1974 © Stephen Shore. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What ways do you see the expanded facility shifting what the department can do moving forward?

Phillips: One of our strengths has been to think of ways to present all kinds of photography. I think that’s one of the great aspects of this medium—the technology is available to everyone. We haven’t shown much of our large vernacular collection and it deserves to be seen because it’s so relevant to the questions we ask of photography now. Now that we accept photography fully as art, the vernacular tradition might be rethought and put into the context of so-called “art photography.” I think this is a wonderful way to get people to think about the diversity of the medium, and what it can do uniquely.

Helfand: How many works are in the collection now, and how much activity happened in terms of growing it during the construction hiatus?

Phillips: Well, there’s something like 18,000 pictures in the collection. During the closure, we got a large and very wonderful group of pictures from Japan, the so-called Kurenboh Collection. I think it’s a very interesting collection, and it really adds to our commitment to Japanese photography, and helps us move forward into the current activity, where there is a vital group of young, important photographers. I think Japan is a very interesting community for photography.

Tseng Kwong Chi, Grand Canyon, Arizona, 1987 © Estate of Tseng Kwong Chi. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: You concentrated on California for your opening exhibition California and the West, which includes mostly recent acquisitions and gifts. Can you talk about the concept of the show?

Phillips: When I did the show called Crossing the Frontier, in 1996, I realized how much amazing material there was that reflected the discovery and development of the West, and what had happened after it was initially developed. It was a show designed to present how we developed Western land for all kinds of purposes, to extract mineral or lumber or whatever, and what we’ve inherited from that. So there will be some of that kind of material in this show as well, but it does not stop there. Since this was a show about the gifts we were receiving, we also wanted to include pictures of the northern California landscape in photographs from people like Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange and Minor White to the present. In California, there’s been a very interesting culture for photography, though it’s not generally recognized as coming from here. That was my stated aim—to discover the tradition and to put it into some kind of context that could be understood, and show how it developed.

Helfand: What are some highlights?

Phillips: There’s some very beautiful early work. Not only Watkins’ pictures of Yosemite, but also early pictures of the developed land. There’s a diptych of a corporate farm in southern California in the nineteenth century. We were also fortunate to receive the beautiful, very important, very modernist surf sequence by Ansel Adams. The show and gift campaign also enabled us to focus attention on photographers of this area associated with the New Topographics exhibition, and to pursue some of the great figures of the 1930s—Weston, Cunningham, Minor White—and add significantly to those holdings. And then we were able to add to the conceptual work that was going on here in the ’70s and ’80s—Bruce Connor, Hal Fisher, Lew Thomas, and finally what’s been happening here more recently with work by Larry Sultan, Mike Light, and Trevor Paglen.

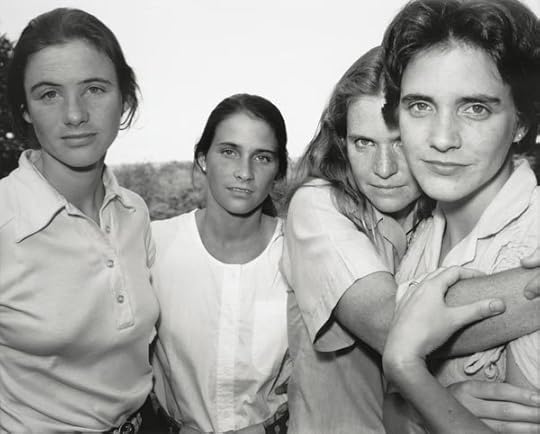

Nicholas Nixon, The Brown Sisters, East Greenwich, Rhode Island, 1980 © Nicholas Nixon. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Helfand: The California show is in dialogue with the other opening exhibition, About Time.

Phillips: About Time is really a show that considers this element of photography that’s constant to it, and pursuing the ideas that come out of it. The show looks at the whole medium and also examines the implications of these ideas in video and projection. I think it’s a really wonderful and important show.

Helfand: How will you be moving forward with the department?

Phillips: I’m officially retiring at the end of June. I will continue to organize shows that have been on the calendar. The show from our Japanese collection is an examination of gifts and promised gifts to the museum. After that, I will put up the Larry Sultan show that comes from LACMA. We’ll have a show I’ve been working on called American Geography that looks at how we live in and use our land. In any case, when the next person in charge of the department is selected, I hope I can have a relationship that is important to the museum. I’d love to do things like work on the history of the department, which I think would be useful to everyone.

Larry Sultan, Isleton, from the series Homeland, 2009 © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What else is coming up in the first year or two of exhibitions?

Phillips: There’s a wonderful show of Anthony Hernandez, a photographer in southern California who has never had the attention his work certainly deserves. My colleague, Erin O’Toole, will be doing that.

Helfand: What was it like to have a three-year moment of working behind the scenes versus public presentations?

Phillips: It certainly was not easy. We were divorced from our collection. We’d have to go down to the collection center and work there to see it. But I would say it provided a time for us to really think about the collection in a more abstract way—what it really needed, what the goals were. We spent some serious time doing a kind of analysis of our department, a strategic plan. We were given this opportunity to rethink the department’s goals, refine our collecting objectives, and to rethink how the department works. That was really, really hard, and really, really important. It was a difficult but worthwhile period for us and I think we made very good use of that time.

Glen Helfand is a freelance writer and Associate Professor at California College of the Arts.

The post At San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, a New Frontier for Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 20, 2016

Does Mapplethorpe Still Matter?

Notorious for photographs that pushed private desire into the public realm, two major exhibitions in Los Angeles consider the artist—and the man—in full.

By Sayantan Mukhopadhyay

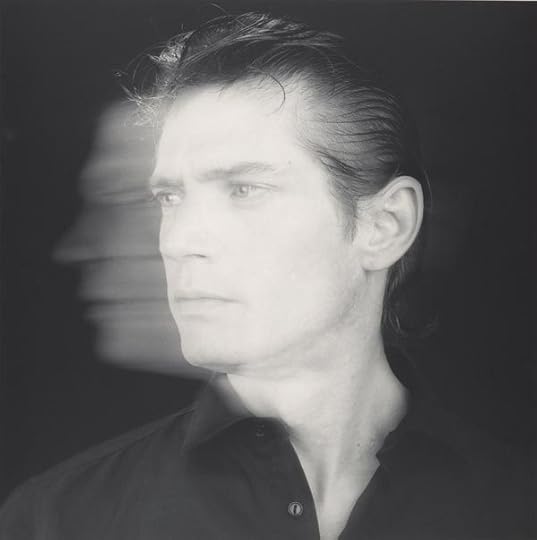

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1985. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The story of Robert Mapplethorpe is a tantalizing emblem of a vanished moment in New York’s urban history, shaded by the underground sexual hedonism of the 1970s and the pursuant AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Mapplethorpe’s status as a dominant figure in twentieth century photography is a product, in part, of the close circle of influential colleagues crucial to his biography: friend and former lover, Patti Smith; patron and partner, Sam Wagstaff; rival and idol, Andy Warhol. But Mapplethorpe was an artist responding to a particular sociopolitical climate, which has to be defined not only by the mythologized demimonde of downtown New York, but also the cultural flashpoint of his first posthumous retrospective, in 1989, which secured his position among a queer intelligentsia flourishing in a time of urgent need.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Two Men Dancing, 1984. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The Perfect Medium, two concurrent retrospectives of the work of Robert Mapplethorpe hosted simultaneously at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Getty Center, provides the richest narrative about the photographer to date. By centering on Mapplethorpe’s world—his network of affiliations—instead of resting on the artist’s brand of sexual bombast, the shows manage to lift Mapplethorpe out of the often facile discourse on pornography’s contentions with fine art. Together, the exhibitions form a monumental homage to the late artist that at once attempt to resuscitate the narrative of the enfant terrible of American photography, while challenging the grounds on which his fame has been earned. Mapping Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre onto Los Angeles’s diffuse sprawl in a show that spans two locations is a test of ambition, yet despite the miles of freeway separating the institutions housing the exhibitions, the result is a resoundingly cohesive image of the man.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Banana & Keys, 1974 Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

LACMA’s intervention begins with Mapplethorpe’s rarely seen early student work, featuring multimedia installation, collage, and new media. The growing pains of a young practitioner are on view in vitrines: a set of artist-made necklaces, as well as a trio of t-shirts, render the fabled photographer human. This biographical focus contributes to a three-dimensional approach taken by LACMA, allowing Mapplethorpe’s legacy to transcend his relationship to the camera. The first room in LACMA’s iteration of the show is successful in providing important and vivid contextual backdrops for the many developments in Mapplethorpe’s studio practice.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Calla Lily, 1988. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

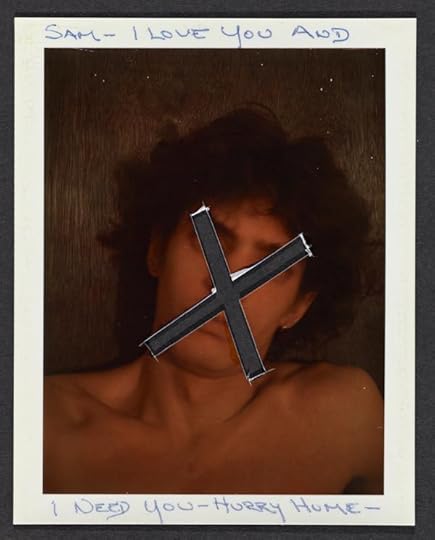

The remainder of the LACMA exhibition centers on the figures that oriented Mapplethorpe’s later work, before moving onto both his BDSM and flower series. On view in tandem with his sexually explicit photographs—labeled discreetly with an advisory warning as wall text—the Mapplethorpe Archive supplies treasures from the artist’s personal collection of knickknacks, including pornographic mail-order photographs. These souvenirs enliven an image of a man whose life’s work has had a resonant impact, in art history and contemporary visual culture, on ideas about the body and desire. The strength of LACMA’s contribution the retrospective is the context these illustrative objects add to the photographs themselves.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Joe, NYC, 1978. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The Getty offers a complimentary entry into Mapplethorpe’s life, sometimes doubling up on the subject matter addressed across town at LACMA. The most prominent feature in the Getty’s presentation is Mapplethorpe’s subversive X Portfolio (1978), a series portraying jarring acts of extreme sexual bravado. A moveable wall, mounted with an iconic flower photograph, decorously screens off images from the portfolio. The meeting of these two oppositional mainstays—the corporeal and the floral—is a poetic metaphor for the sensitive treatment that both the Getty and LACMA have given to the artist’s body of work.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Kathy Acker, 1983. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Descriptions of Mapplethorpe’s complicated identity are often crudely flattened into commentary on the uneasy line he towed between fine art and pornography. But this expansive, unprecedented exhibition never denies the complexities of Mapplethorpe’s trajectory as an artist, a celebrity, a friend, and a lover. Previous Mapplethorpe shows to approach this scale—notably The Perfect Moment, which traveled in the U.S. in the late 1980s and spawned rancor for its supposed peddling of erotic imagery as art—have been received reductively as valorizing the artist simply as a formalist quasi-pornographer, while ignoring the vast social make-up of his prominence.

The exhibitions at LACMA and the Getty, and the accompanying LACMA catalogue, address this history through essays that not only look to Mapplethorpe’s status as a queer revolutionary, but also a skilled portraitist, a pioneer of style, and a purveyor of fashion and fetish. The Getty Research Institute’s publication on the Mapplethorpe Archive serves to round out the discussion by narrating Mapplethorpe’s life story through objects from his personal collections.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Untitled (“Sam—I love you and I need you—hurry home”), 1974. Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Through their delicate resurrection of the life and times of this art historical underdog, these exhibitions and attendant publications offer the viewer an opportunity to consider the headway that has been made in the discourse on queer visibility in America. While we become increasingly committed to the normalizing of peripheral identities—through same-sex marriage modeled on heterosexual partnerships, rallying around the rainbow flag that reifies a non-existent unified gay nationalism—Mapplethorpe reminds us of the truly radical power latent among queer communities to resist mainstream expectations. The progressive vision embodied by Mapplethorpe’s photographs has yet to be realized. The LACMA and Getty exhibitions are thus a spectacular portrait of a man whose short life fueled suspicion and excitement, and whose images lit an expansive array of incendiary debates in contemporary art and American culture at large. In The Perfect Medium, the embers continue to burn.

Sayantan Mukhopadhyay is a doctoral student in of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles, where his research includes the exhibition history of modern art from South Asia.

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium is on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Getty Center through July 31, 2016.

The post Does Mapplethorpe Still Matter? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 19, 2016

Inside the 2016 Aperture Spring Party & Dinner

Spring Party co-chairs Julie Meneret and Jessica Nagle, Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Cathy Kaplan, Jim and Missy O'Shaughnessy, Jessica Nagle, Darius Himes, Julie Meneret, Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Malú Alvarez and Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Elizabeth and William Kahane. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Bruce Barnes, Neal Slavin, Lisa Hostetler, Denise Wolff, Stephen Shore, Chris Boot, Stanley and David Zabar. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Atmosphere. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Darius Himes. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Neal Slavin and Anita Slavin. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Nadiya and Whit Williams. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Alexander Hurst and David Meneret. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Chris Boot and Lindsay McCrum. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Ashley Dennig and Brianna Martin. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Emory Lecrone and Meredith Hinshaw. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Yasu Nakamori, Barbara Tannenbaum, Darius Himes. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Stephen Shore with dinner guests. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Alvise Marino. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Sasha Frolova. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Cathy Kaplan and Anne Stark Locher. Photo by Max Mikulecky

EXP. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

EXP, Karin Kuroda, Bora Kim, Samantha Yung Shao. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Cathy Kaplan, Jim O'Shaughnessy, and Missy O'Shaughnessy. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Stefan Ruiz. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Zenith Richards. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Ilva Heitmann. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Aliza and Gabrielle Sena. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Severn Taylor, Martha Posner, Elizabeth Kahane, Susan Dumke. Photo by Patrick McMullan © Patrick McMullan

Laurent Claquin and Chris Boot. Photo by Owen Hoffmann/PMC © Patrick McMullan

Chris Boot and Deborah Barsel. Photo by Sita Fidler

Stephen Shore’s pie was just the beginning. Celebrating the pre-launch of The Photographer’s Cookbook, copublished by Aperture and the George Eastman Museum, the more than 325 guests who attended Aperture’s second annual Spring Party were treated to inventive fare by BITE inspired by some of the most photogenic recipes around. The event was co-chaired by Jessica Nagle and Julie Meneret and co-hosted by Aperture’s executive director Chris Boot and Darius Himes on behalf of presenting sponsor Christie’s. During the Host Committee Dinner, guests had the opportunity to chat with Cookbook contributors Stephen Shore and Neal Slavin.

Proceeds from the event support Aperture’s youth education programs and educational and community partnerships, including Aperture on Sight: Teaching Visual Literacy Through Photography, designed to cultivate visual literacy through photography and photo book creation. Under the sparkle of lights at Aperture Gallery in Chelsea, where the photographer Doug DuBois’s current exhibition, In Good Time, is on view, guests danced to disco music by DJ and photographer Stefan Ruiz or watched professionals—the K-pop phenomenon EXP—take the floor. Of the two night’s two prizes, one winner took home a basket with The Photographer’s Cookbook and sundries from Zabar’s, the iconic Upper West Side emporium and cosponsor of the Spring Party, and another guest won a Key Lime Pie Supreme straight from the kitchen of Shore himself.

Additional party photos are available on patrickmcmullan.com.

Click here to make a donation to Aperture’s Annual Fund.

For a sensational and sold-out evening, Aperture wishes to thank co-chairs Jessica Nagle and Julie Meneret; Presenting sponsors Christie’s and Zabar’s; contributing artists Stephen Shore and Neal Slavin; Bruce Barnes and Lisa Hostetler of the George Eastman Museum; AIPAD; Brooklyn Brewery; Hotel Americano; Espolon Tequila; Foto Care; Jean Perrier et Fils; Patrick McMullan Company; Pro Sho; and Smilebooth; DJs Stefan Ruiz & Al-Veez; and EXP (Bora Kim, Karin Kuroda and Samantha Y. Shao). Additional thanks to all of the Aperture staff, work scholars, volunteers, and ambassadors for their time and dedication.

Host Committee

Allan Chapin and Anna Rachminov

Andrew Lewin

Anne Stark Locher and Kurt Locher

Barbara and Donald Tober

Bill and Victoria Cherry

Cathy M. Kaplan*

Christine Symchych

Crystal McCrary and Raymond J. McGuire

D. Severn Taylor and J. Scott Switzer

Darius Himes, Christie’s*

David Solo

Elaine Goldman

Elizabeth and William Kahane

Frederick M. R. Smith

Jessica Nagle and Roland Hartley-Urquhart*

Julie and David Meneret*

Kasper

Kate Cordsen

The Lauder Foundation–Leonard & Judy Lauder Fund

Malú Alvarez

Marcy Morgan

Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy

Michael Hoeh*

Nion McEvoy*

Olivia Marciano

Peter Barbur and Tim Doody

Priscilla Rattazzi

S. B. Cooper and Rebecca Besson

Scott Martin and Lauralee Bell Martin*

Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla

Stanley Zabar, Zabar’s and Zabars.com*

Susan Dumke

Whit Williams

Willard Taylor and Virginia Davies

*Leader

Spring Party Committee

Alexander G. Clark

Alexander Hurst

Dianna Cohen

Esther Zuckerman

Isabelle Friedrich McTwigan

Liz Grover

Olivia Marciano

Sarah Krueger

The post Inside the 2016 Aperture Spring Party & Dinner appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 13, 2016

Japan at the Edge of Reality

Five years after the devastating earthquake and tsunami, a group of visionary Japanese photographers responds to a national tragedy.

By Russet Lederman

Lieko Shiga, Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore) 45, from the series Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2012 © Lieko Shiga. Courtesy the artist and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

On March 11, 2011, the world watched as the 3/11 Triple Disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear reactor failure wreaked havoc and destruction across Japan’s northeast Tohoku region. Five years later to the day, Japan Society has opened In the Wake, a group exhibition that examines the various responses by seventeen Japanese photographers to the profound devastation and loss that mark the national tragedy.

In the Wake, conceived by and originally presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has been reinterpreted into three distinct yet overlapping sections in the current installation at Japan Society: documentary approaches to the disaster, response through experimental photographic practices, and the development of a new narrative that blurs the boundaries between the actual events and representations. Intertwined and inescapable within all the photographs, projections, and installations on view are the larger issues of visible destruction and invisible harm.

Naoya Hatakeyama, 2011.5.2 Takata-chō from the series Rikuzentakata, 2011 © Naoya Hatakeyama. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As a photography exhibition about a widely photographed tragedy, In the Wake begins with images and texts by two photographers whose lives and families were directly affected by 3/11 loss. Naoya Hatakeyama, who lost his mother and family house when the tsunami decimated his hometown of Rikuzentakata, presents side-by-side projected images that chronicle the town before and after the devastation, and its slow progression toward recovery. Also directly affected was Lieko Shiga, whose works are prominently displayed at both the beginning and the end of the exhibition. As the resident photographer for the coastal town of Kitakama, Shiga was responsible for photographing local ceremonies and documenting the village’s aging population. Kitakama was hit particularly hard by the tsunami. Shiga’s journal-like text and small-scale black-and-white photographs introduce the magnitude of personal loss immediately following the tragedy. Her efforts to recover family photographs that were scattered by the tsunami are displayed in a large-scale image that shows the village’s assembly hall transformed into a photograph-drying center for retrieved memories.

Takashi Arai, April 26, 2011, Onahama, Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture, from the series Mirrors in Our Nights, 2011 © Takashi Arai. Courtesy Photo Gallery International and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Hatakeyama’s and Shiga’s focus on individual loss sets a humanizing tone for the images that follow in the north gallery. Taken by photographers who traveled to the Tohoku region to document the aftermath of 3/11, these photographs convey an overwhelming sense of loss and visible damage from a nonjournalistic stance. Large-format color photographs by Keizo Kitajima show the ghosts of homes and boats barely standing, while a central projection by Rinko Kawauchi sequences images from her Light and Shadow series of two pigeons flying above mountains of debris and a ravaged landscape. The devastation is enormous, but so is humankind’s capacity to recover. Yasusuke Ōta’s photograph Deserted Town, of an ostrich in the middle of an empty shopping street, reveals abandonment tinged with humor.

Yasusuke Ōta, Deserted Town, from the series The Abandoned Animals of Fukushima, 2011 © Yasusuke Ōta. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Not all the photographers who ventured to Tohoku in the weeks after the disaster documented visible representations of destruction. An ominous silence pervades Shimpei Takeda’s abstracted, almost celestial images of irradiated soil. Takashi Homma also exposes unseen dangers in stark funereal photographs of mushrooms with high radiation levels from the forests near the Fukushima nuclear power plant. These nuanced approaches to documenting the invisible contrast strongly with the powerful personal voices and sense of renewal in Lost and Found, a full-wall installation of rescued snapshots from Tohoku debris by the volunteer-run Salvage Memory Project.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled, from the series Shakyō rōjin nikki (Diary of a Photo Mad Old Man), 2011 © Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A quiet moment for reflection is offered in the all-black gallery containing Takashi Arai’s iridescent daguerreotype images of scenes shot around Fukushima and at Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome monument. Arai’s contemporary interpretations of a nineteenth-century technique form a perfect segue to the south gallery, which showcases photographers whose images rethink established photographic conventions. All of the photographs in this section are by photographers who responded to the 3/11 disaster without traveling to the Tohoku area. Kikuji Kawada—who is well-known for his 1965 photobook Chizu (The Map), a response to the Hiroshima atomic bombing—is represented with a wall of highly saturated, ominously glowing images repurposed from news and television reports. Nobuyoshi Araki underscores the depth of the destruction in his large-scale black-and-white photographs with surfaces defaced by brutal black slashes. Material destruction in a process that combines analog with digital produces the degraded ghostlike images and artifacts in the work of Daisuke Yokota.

Lieko Shiga, Mother’s Gentle Hands, from the series Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2009 © Lieko Shiga. Courtesy of the artist and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Drawing upon the Tohoku region’s strong tradition of mysticism, In the Wake concludes with ten large color images by Lieko Shiga of elderly Kitakama residents caught performing mysterious acts against surreal landscapes. Suffused with a garish nighttime glow, their performances are an otherworldly manifestation of reality as it blends with a postapocalyptic fantasy.

For Japanese photographers, history repeats itself. National tragedy and its associated anxiety again act as a catalyst for a new visual language that pushes photographic conventions beyond the edges of reality into a fluid space that hovers somewhere between the unseen and abstraction.

Russet Lederman, a researcher and writer, teaches art writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11 is on view at Japan Society in New York through June 12, 2016.

The post Japan at the Edge of Reality appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 11, 2016

Adventure on the Danube

In 1958, Inge Morath set out to document the cultures of Central and Eastern Europe. Spanning four decades, her monumental project was the quest of a lifetime.

By Amanda Hopkinson

Inge Morath, Oyster farming near Danube delta, Romania, 1994 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

Several months after the end of World War II, Inge Morath joined a long caravan of displaced people heading south from Berlin. She hitched rides and spent days and nights walking. “It’s amazing how kind of crusty you get, with dirt and probably bugs,” she recalled. “You can feel nice and ready to drown yourself, and that night there was a little river nice and ready for the purpose.” Saved by a one-legged soldier—perhaps just a phantom—who hauled her off the precipice of a bridge, she continued the slow march to her parents’ home in Salzburg, Austria. It was, perhaps, the first occasion on which a river was to play a decisive part in Morath’s life.

Back in Austria in the late 1940s, Morath made her first journalism contacts by writing for the United States Information Service in Salzburg and Vienna, and later freelanced for national radio, as well as for the magazines Rot-Weiss-Rot and Der Optimist. In 1951, when she added Heute to her clients, she received a camera as a Christmas present. By then she had become acquainted with a fellow Austrian, Ernst Haas, who had joined Magnum Photos in Paris in 1949. Helping out in the picture agency’s office persuaded her that life was more vivid behind a camera. By 1952, she was working for Simon Guttmann’s legendary Dephot agency in London, where she was as likely to be asked to sweep the floor as to shoot a commission.

Inge Morath, A newly engaged girl, dressed in her Sunday costume and wearing a bridal crown, walks with two girl friends from house to house to announce the great event, Rumania, Near Sibiu, 1958 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

A year later, Morath was back in Paris, working as a researcher and assistant to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Considering her appetite for travel and spirit of adventure, her command of several languages, her burgeoning talent for editorial photography, and her close friendships with several Magnum members, Morath’s admission to the Magnum agency, in 1955, now seems inevitable. Yet, it was immediately clear that she was not going to be the token woman assigned to “soft stories” (animals and children); her first big story was on the worker-priests of Paris, followed by documentations of the London underworld and post-civil-war Spain. Soon her portfolio included Paris Match, Holiday, Saturday Evening Post, and Life, the most sought-after (and highest-paying) of all.

It was the very fluidity of her life—her frequent changes of location, her unbounded work across many media—that would enhance Morath’s fascination with the Danube River. According to the Austrian photographer Kurt Kaindl, Morath “bore within her an inchoate longing for the great cultural spread of Eastern Europe. From the moment she joined Magnum as a photographer, she repeatedly photographed parts of the Danube, especially in her native Austria and in neighboring Germany.” In 1958, as Morath wrote in her travel diary, the time had arrived: “The great adventure can begin.”

Inge Morath, On board a boat in the Danube, between Galatzi and Tulcea, Romania, 1958 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

The longest trans-European river, the Danube passes through communities with distinct cultures, languages, and work and life patterns, and has been a source of continuing fascination and inspiration at least since Roman times. Among the many regional inhabitants at the beginning of Morath’s work were Austrians, Bulgarians, Croats, Germans, Hungarians, Jews, Roma, Romanians, Serbs, Swabians, Ukrainians, and the Slovenians of the Morath family’s roots. On May 16, Morath opened her travel journal to write: “Departure from Paris. 21.20 sleeper train to Vienna. Orient Express. Or was it only called Orient Express after Vienna?” Trundling through Hungary to Romania, upon reaching Bucharest, Morath sharply anticipates what lies ahead as soon as she is met by her interpreter: “Roundtrip through town, visit the Village Museum. Bad lunch in Lido. Penelope not a good interpreter. … With this lady I am not going to go far. Courage. We’ll see.”

Courage, however, was an attribute Morath had in spades. Although undefeated, she was frequently frustrated. The journals, typed on an ancient Remington typewriter, are a polyglot mix of English, French, German, and the occasional Romanian, as she records her itinerary, weather reports, and personal commentary. She voyaged, as she wrote, “on foot, drove cars, hitched truck rides, rode trains, ferries, boats and steamers.” In practice it was almost entirely by train or car, the Danube being out of bounds to private travelers, with her program prescribed for her. Irritations, delays, and perplexity were endemic: “From Sinaia to Comarna, co-operative for carpet making. Up to a place called Costa. Great view. But no photos. I am driven crazy by not getting any material. Drive to Brasov, Kronstadt in German. Totally Germanic in aspect. Dinner with a Madame Thalmann. Don’t know why.”

Inge Morath, Liberation Hall, 34 victories in marble, one for each of the German states – from a circle, holding between them 17 tablets inscribed with the names of the battles fought in the victorious War of Liberation against Napoleon from 1813 to 1815, Kelheim, West Germany, 1959 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

Morath had no publication or exhibition planned when she made the Danube journey, nor any anticipated date to resume. Yet two months later, she embarked again on her quest. This time she was more assertive: “I am adamant. Finally obtain permit to sit on one of the tribunes to photograph the parade celebrating victory of Communism. Hot. I still suffer from a kind of isolation.” Exasperated by constant interruptions and requests to show her permit, Morath was a street photographer barred from photographing on the street, continuously reminded of how she was external to the events she witnessed. Hotels are so “grimy” she retires to bed without eating. Banned from accepting an invitation to a wedding party by her minder, casting a sad farewell glance at the delicious food on offer she retires to bed “to eat chocolate.”

Morath’s first voyage on the Danube followed the closing of the Iron Curtain; the last came in the wake of its opening, in 1993. The collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with a proposal from Kurt Kaindl and his wife, Brigitte Blüml, that together they retrace Morath’s tracks along the river. On the first expedition, Morath’s pictures had received their principal exposure in the form of a long photo-essay published in Paris Match in 1959. Kaindl also knew how Morath still longed to pursue her Danubian theme, her lifelong aim to create an extended photo-essay. He assembled the proposal for a book and an exhibition at the new national gallery of photography, the Fotohof, where he and his wife had formed part of a collective of curator-directors. Morath accepted with alacrity, sending a handwritten letter proposing she take a plane from her latest exhibition opening in Pamplona.

Inge Morath, Boys in the street, Nikopol, Bulgaria, 1994 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

While her first trips were self-financed and made alone when she was in her early thirties, on the later trip Morath was in her seventies and in failing health. Kaindl and Blüml, managing the project, took turns accompanying her on five trips over two years. They obtained funding and brought the publisher Otto Müller on board; Kaindl proposed a monograph similar to Claudio Magris’s magnum opus, Danube: A Sentimental Journey from the Source to the Black Sea (1986), and was at once accepted. The 1994 voyage, however, was marred by technical problems aboard a boat in the Danube Delta whose ignition kept cutting out as it dodged across shipping lanes, intermittently blocking the traffic and risking being mown down. Fuel shortages persisted, and whole villages banded together to supply enough for transport to the next stopping point. Kaindl’s photographs show Morath aboard yet almost indistinguishable, shrouded in borrowed hats, scarves, and fisherman’s oilskins against the penetrating cold.

Morath liked to point out how a photograph is made in a fraction of a second, yet the image may be the result of years of observation. When the Fotohof opened in Salzburg, in 2012, on the newly named Inge-Morath-Platz, an exhibition showcased Morath photographs. Behind fifty years of creative work was a lifelong yearning: “I secretly long for that stretch of land along the border,” she once said. “When someone asks me ‘Where are you from? Where do you feel at home?’ then—apart from where I’ve lived so long in America—here in these vineyards, my childhood paradise. But the land across the border, about which my mother Titti told me so much, is also a part of it. Strange that I’m rediscovering these things now.”

Amanda Hopkinson is Visiting Professor in Literary Translation at City University London.

The post Adventure on the Danube appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 7, 2016

5 Exhibitions to See in April

Ellsworth Kelly, the Guerrilla Girls, and the Italian coast. Here are the must-see photography exhibitions in New York this spring.

Luigi Ghirri, Trevigliano Mazzano, Portoghesi, case, popolari, 1985 © Estate of Luigi Ghirri. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Luigi Ghirri: The Impossible Landscape

Matthew Marks Gallery, 526 West 22th Street, New York

Through April 30, 2016

How do small, quiet images of idiosyncratic subjects and their strange textures—torn advertisements, tile arrangements, eccentrically manicured plants, and panes of blue sky—have the power to speak about the construction of memory? This is the enigma at the heart of Luigi Ghirri’s vernacular-style photographs taken predominantly in his home region of Emilia-Romagna, Italy, in the 1970s and ’80s. Informed by an earlier career in landscape surveying, where he learned to codify the emotional and associative sensations of unremarkable surroundings, Ghirri approached landscape photography with a pioneering conceptualism drawn together with affection for his northern Italian milieu. In his 1989 essay “The Impossible Landscape,” after which this show is titled (and anthologized in the recent book Luigi Ghirri: The Complete Essays 1973–1991), the artist suggests that when we are presented with the image of a place—even the sequential, banal elements of our everyday environment—our personal histories show up to complete the picture. The warm quality of Ghirri’s vintage chromogenic and cibachrome prints are documents of a time when color was only just becoming an expressive consideration in photography and amateur work, evolving out of a postwar snapshot generation. Ghirri, alongside other pioneers of color, shifted the way the photograph engaged the modern, everyday world. —Genevieve Allison

Hiro, Kelly Stewart, New York, 1994 © Hiro. Courtesy Pace/MacGill

Pace/MacGill, 32 East 57th Street, New York

Through April 16, 2016

In a possibly apocryphal story, Richard Avedon is said to have watched Hiro stare at a single transparency all day. Although Hiro may not enjoy the name recognition of the giants he apprenticed under—Avedon and legendary Harper’s Bazaar art director, Alexey Brodovitch—he shares their obsession with formal and technical mastery. Hiro’s black-and-white portraits of notables from Jacques Costeau to Muhammad Ali project their subjects into the realm of the iconic (an Avedon signature). When he did leave the studio environment, he appears to have reigned in chance: one image of passengers crammed into a Tokyo metro feels as if the photographer organized the scene himself. But it’s with the still life form that Hiro thrived and pushed his capacity for invention. With their deeply saturated color and analog manipulation, these images elevate the ordinary to the monumental and surreal—an egg fries on the scabrous surface of a Utah Salt Flat, an ant perches atop a garish-red fingernail. 1970s supermodel Jerry Hall is caught in profile on a Saint Martin beach exhaling a sinuous smoke plume that merges with the clouds—an effortless gesture that is a hallmark of Hiro’s output, even if he might have been scrutinizing his transparencies all day, searching for formal perfection. —Michael Famighetti

Petah Coyne and Kathy Grove, The Real Guerrillas: The Early Years, AKA Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, 2015–16 © Petah Coyne and Kathy Grove. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

Galerie Lelong, 528 West 26th Street, New York

Through April 23, 2016

Each pair of artists in this imaginative group exhibition generates images with strikingly diverse methods. In the 1970s, Neville D’Almeida and Hélio Oiticica made “supra-sensorial,” multi-media environments using photographs that depict patterns of powdered cocaine on commercial images of Marilyn Monroe, Jimi Hendrix, and other celebrities. These photographs, printed decades later, were once projected on walls, ceilings, or even into swimming pools as viewers lay on foam mats or in hammocks. Twin brothers, and longtime artistic duo, Doug and Mike Starn share a studio and work side-by-side, essentially as one artist; here, they create labyrinthine patterns of tree branches on delicately layered Japanese paper. Lin Tianmiao and Wang Gongxin, married for thirty years before incorporating their artistic practices, show a series of photographs with figures in otherworldly costume. But the draw of Narrative/Collaborative is new work by Petah Coyne and Kathy Grove, artists with decades-long solo careers, who have come together to create The Real Guerrillas–The Early Years, a never-before-seen series that seeks to document and celebrate each woman who participated with the Guerrilla Girls collective between 1985 and 2000. Conceived as an ongoing project, the series presents fictionalized portraits of each Guerrilla Girl, masked and digitally imposed into an artwork by her artist persona—lesser-known art historical figures including Lyubov Popova, Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun, Chansonetta Stanley Emmons, and Remedios Varo. (The prints are accompanied by extensive narrative captions.) Only after a member passes away can her identity be exposed, when Coyne and Grove will reveal a second photograph, named and unmasked. Through this completed, future portrait of each Guerrilla Girl, and the powerful woman behind the mask, Coyne and Grove aspire to acknowledge each woman’s life of anonymity and her work within and outside of the collective. —Taia Kwinter

Ellsworth Kelly, Hangar Doorway, St. Barthélemy, 1977 © Ellsworth Kelly. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Matthew Marks, 523 West 24th Street, New York

Through April 30, 2016

Printed and prepared by Ellsworth Kelly just months before his death, at age 92, in December 2015, the thirty-one gelatin-silver prints presented in this fascinating exhibition—the first ever dedicated to the artist’s photography—are a revelation. Kelly’s little-known talent behind the lens displays the clarity and incisiveness of a vision that transcends mediums. Produced between 1950 and 1982, during a period of remarkable creative ferment when Kelly moved from France to upstate New York, the photographs, which he considered to be independent from his painting, nevertheless suggest the figurative origins behind his boldly abstract canvases. Like his paintings, they look squarely at the natural and built worlds, finding compositions that are at once self-evident and abstract. Architectural structures—doors, windows, roofs, and the shadows they cast—figure throughout, transformed into a language of binaries, diagonals, contrasts and surprising synergies. These forms exist everywhere, according to Kelly. You just don’t see them—until now. —Genevieve Allison

Nadav Kander, The Aral Sea I (Officers Housing), Kazakhstan, 2011 © Nadav Kander. Courtesy Flowers Gallery

Flowers, 529 West 20th Street, New York

Through May 7, 2016

While the splendid ruins of the ancient world provide inspiration to young architects and tourist dollars to local economies—unless they’ve been bombed by ISIS forces—the ruins in Nadav Kander’s photographs in Dust are recent enough to provoke a sense of anguished fascination. Kander discovered the previously unknown sites of Kurchatov and Priozersk, towns along the Russian-Kazakhstand border, on Google Earth, where the physical evidence of Cold War-era nuclear experiments is manifest in partially collapsed buildings—stadiums, administration buildings, or factories—revealed now as humble cenotaphs. A sequence examining the Polygon, an atomic test site opened in 1947, is especially disturbing for what Kander’s images do not or cannot portray. Contrary to official claims, a local population lived in close proximity to the Polygon, where nuclear testing took place, and the subsequent effects of cancer and birth defects are widespread. (The dimming rays of an electric pink sunset at the Polygon are apocalyptic.) In Kander’s images of the Aral Sea, once a thriving fishing port, where water has drained away for irrigation of cotton, the sagging tides bring up pink foam, perhaps the runoff of chemical waste. Summoning the horror of Hiroshima, in the accompanying catalogue Will Self claims that the landscapes in Dust do not aestheticize these ruins or “make beautiful what is not,” but instead they confront Western society with souvenirs of its hubris in science and politics. Many of the former military buildings in these test sites were destroyed to hide the past, but the remaining structures, floating on grasslands like abandoned boats, describe the perils of atomic warfare with subtle but unambiguous power. —Brendan Wattenberg

The post 5 Exhibitions to See in April appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 5, 2016

Shooting the Holy Land

In a new documentary, Josef Koudelka turns to a divided landscape.

By David Levi Strauss

Josef Koudelka in Israel/Palestine. Still from Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land, 2015 © Gilad Baram

The genre of documentary films about documentary photographers has grown considerably and admirably over the last twenty-five years, including The Salt of the Earth (2014), about Sebastião Salgado, by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado; What Remains (2008) about Sally Mann, by Steven Cantor; War Photographer (2001), about James Nachtwey, by Christian Frei; and Pictures from a Revolution (1991), about Susan Meiselas, by Meiselas and Alfred Guzzetti, to name a few of the best.

To this list we can now add Koudelka Shooting Holy Land (2015), by the young Israeli photographer and filmmaker Gilad Baram. Baram was hired to assist Koudelka in Israel and the Palestinian territories by making travel arrangements and providing security, logistical support, and captions as the photographer worked on his epic project to document the building of the wall in Israel, culminating in the book Wall: Israeli & Palestinian Landscape, 2008–2012, published by Aperture in 2013.

Josef Koudelka, Rachel’s Tomb, 2009 © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

Josef Koudelka, born in 1938, is arguably one of the greatest living photographers. He burst onto the international stage in 1968, when he photographed the Russian invasion of his native Prague. His photographs were smuggled out of Prague to Magnum and published anonymously, but they were so distinctive that they refused to remain anonymous. His later books Gypsies (Aperture, 1975) and Exiles (Aperture, 1988) changed how people view documentary photography. More recently, his work has focused on panoramic landscapes.

Koudelka is part of a generation of documentary photographers who believe fervently that if you show people what is actually happening in the world, they will understand and be moved to demand change. Social documentary photography has always been defined by this passionate subjective belief in democracy and action. Without it, the practice devolves into self-involved sensationalistic pandering.

Josef Koudelka, A crusader map mural, Kalya Junction, Near the Dead Sea, 2009 © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

This makes the filmic documenting of documentarians a rather precarious process. If you shift the focus of your inquiry too completely to the photographer, and away from his or her subject, you risk the diminution of the subject and obscure the motive force of the work.

At first viewing, one might think that Gilad Baram has made a nature film, perhaps about a particular species of bird. Everything this creature does has one purpose: to make better images. Everything else is peripheral. So Baram lets the peripheral in. What is happening around the photographer becomes the filmmaker’s subject, and this periphery is loaded with meaning, because the social landscape impinging on the wall is an especially complex one: the enforced borders between the State of Israel and its Other within, the Palestinians of the occupied territories.

Josef Koudelka, Shu’fat Refugee camp, overlooking Al ‘Isawiya, East Jerusalem, 2009 © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

Koudelka continuously and relentlessly points his formidable and precise beak, a Fuji GX617 panoramic camera, into the crevices and fissures of this fraught border, and the official enforcers react with increasingly menacing warnings. As we watch Koudelka repeatedly violate these boundaries as he attempts to get into position to make the best photographs, we recall Magnum cofounder Robert Capa’s famous injunction: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” When Koudelka gets close, a disembodied voice from a loudspeaker barks, “Photographer, move away from the fence! Go back, photographer. Move back!”

Koudelka is not photographing war here, but the visible wounds of war in the form of walls built to control the movements of the enemy within. His movements reflect the preemptive violence of these walls that shatters lives on both sides of the divide. “One wall. Two jails.”

At one point, seventy-five-year-old Koudelka painstakingly slides on his back under and inside a mass of razor wire, trying to get into position to compose a shot, as the barbs tear his clothes. All that matters is the photographs, because they’re the only thing that will last. The characteristically laconic photographer says little about the situation, directly. “I hate the Wall. But, at the same time, it is pretty spectacular, this Wall.” He speaks at one point about the necessity “to keep the healthy anger; to keep it as long as possible.”

Josef Koudelka in Israel/Palestine. Still from Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land, 2015 © Gilad Baram

But mostly, he only talks about the pictures: “In this place there is a picture waiting for me.” There is a lot of waiting. Waiting for the picture, waiting for the weather to break, waiting to get into position. Watching, looking, moving, waiting. “Sometimes it happens. Sometimes not.”

Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem; Qalandiya Checkpoint in Ramallah; “Detroit” (Al Baladiya) Urban Warfare Training Facility near Tze’elim; Shab Al Dar in East Jerusalem; the Judean Desert; the memorial site for the Israeli Army’s 679th Armored Brigade in the Golan Heights; Mount Gerizim in Nablus. Four frames on a roll of 120mm film. One day = 20 rolls. Focus to infinity.

David Levi Strauss is a writer and critic based in New York and the author, most recently, of Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow: Essays on the Present and Future of Photography (2014).

Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land will be screened at Finale Plzen, April 15–21, 2016 and DOK.fest Munich, May 5–15, 2016.

The post Shooting the Holy Land appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 31, 2016

The Business of Photography: A Conversation with Mary Virginia Swanson

A leading photography educator shares essential advice for working artists.

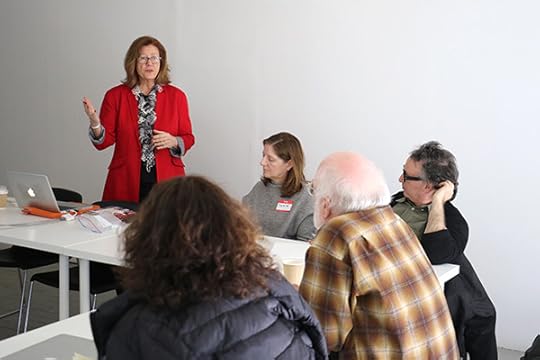

Mary Virginia Swanson’s workshop To Be Published, or Self-Publish? at the Aperture Foundation, February 2016. Photographs by Becca Imrich

Aperture workshops bring students, professionals, and amateurs together with leading photographers working in a variety of fields and genres for intensive educational experiences. Registration is open for the two remaining sessions of the Business of Photography Series—Introduction to Multiple Markets and Your Work, Your Brand—taught by Mary Virginia Swanson, renowned author, educator, and consultant in the photography community.

Aperture Foundation’s Education Work Scholar, Becca Imrich, spoke with Swanson recently about her thoughts on the photography publishing market, favorite photobooks, and advice for photographers and photo enthusiasts looking to take their projects and careers to the next level.

Becca Imrich: When did you develop your affinity for teaching? What catalyzed your shift from being a photographer to an educator, and an advocate for other photographers?

Mary Virginia Swanson: As far back as graduate school, when I was the student director of Northlight Gallery [at Arizona State University], I was teaching professional rather than creative practices. I knew I wanted to work with photographs and with artists. It was after gaining a much broader perspective on our field when working at Magnum that I developed a class for NYU called “Career Options in Photography: A Pre-Professional Survey.” We spent two weeks meeting with individuals engaged with photography, and photographers—artists, of course, but also gallerists, curators, master printers, photo editors, art buyers, paper conservators, photo researchers, commercial studio managers, and more. The opportunities I have had to teach involved the business of being an artist—building on one’s strengths and understanding how to build a career. My teaching and mentoring today emphasize maintaining a smart professional practice.

BI: Can you speak about what it was like to work at The Friends of Photography with Ansel Adams during the 1980s?

MVS: Ansel was a lifelong teacher, from leading tours in the Sierras as a young photographer to our workshops in Carmel late in his life. He had an incredible curiosity about creativity and the science of photography, and was interested in what you were interested in. We had an amazing group of people around us and so many of our heroes came to Carmel to meet Ansel. I had the opportunity to meet many inspiring artists, historians, writers, publishers, curators, and gallerists, and came to understand and appreciate that together we are a community.

BI: Is there a particular photobook that initially sparked your infatuation for photobooks, and why?

MVS: My family gave me important photobooks for holidays and graduation—The Family of Man, of course, then later Szarkowski’s The Face of Minnesota was important to me as Minnesota is my homeland. In college I bought exhibitions catalogues as they were more affordable, and I could see the work of more artists. I love publications of collections, my first being A Book of Photographs of the collection of Sam Wagstaff. As I was fortunate to come to know Helmut Gernsheim and study with Bill Jay early in my studies, I still love reading great photo history titles. And lastly, I never tire of reading books about photobooks!

BI: What is a photobook that you’ve seen recently that really resonated with you?

MVS: It’s rare that a photobook doesn’t interest me in some way. I am excited about how photographers are beginning to explore the book form in a way that artist bookmakers have been working for decades. A friend since our college days, Susan kae Grant’s artist books opened that world to me, and two recent titles I love are Penelope Umbrico’s Range (Aperture, limited edition of 500) and the artist-book version of Jane Fulton Alt’s book The Burn called between fire/smoke (self-published, edition of 18). Both titles engage the viewer in an exploratory manner.

BI: While you were teaching the first session of your Business of Photography series at Aperture, I noticed that you’ve distilled these essential questions that get to the heart of what photographers should be considering as they move towards publishing their work. What questions should photographers ask themselves while they are in the process of conceptualizing and developing their projects?

MVS: At conception, understand what the work tells us, and what it does not. It is that unknown that drives one to engage, to push boundaries. At development, question the final presentation format and the vocabulary that one might bring to the work. To me, this is the place where one’s work expands and evolves.

BI: You have reviewed hundreds of artists’ projects over the years! One of the defining factors of our current climate is an inundation of information and images and the democratization of photography. In your opinion, what are the fundamental ingredients of a successful photography project—whether a photobook, exhibition, or both?

MVS: There is a lot of good work out there that fully satisfies the maker and their audience. Far fewer projects feel authentic, however, with their vision, craft and presentation fully resolved, causing the viewer to pause and ponder the work. Rarely do I see work that I have not seen before and when I do, it is memorable.

BI: In recent years, the photobook market has changed significantly and expanded. Still, the question of how to make this business profitable remains omnipresent. What is missing in the photography publishing market, and what is the je ne sais quoi that will keep sustaining it?

MVS: Distribution. If you know your audience, and you know their price point, and you know how to reach them you can make engaging photobooks. But if they sit in storage they are not going to reach any audience and the work and investment you brought to the project certainly won’t make a difference in your career.

BI: What advice do you have for people trying to find their niche in the photography community?

MVS: Take a good hard look at what inspires you in our field and work to get yourself into that aspect of this profession. Your contributions to our industry need not be measured in your accomplishments as an artist. Artists could not thrive if we didn’t have visually sophisticated, supportive professionals surrounding them at every step of the art-making and art-marketing process.

Registration for Introduction to Multiple Markets will remain open until Sunday, April 17, 2016. Registration for Your Work, Your Brand will remain open until Sunday, May 1, 2016.

For more information on Mary Virginia Swanson’s Business of Photography Workshop Series, and other upcoming workshops at Aperture, please visit aperture.org/workshops or contact education@aperture.org. For information about Aperture’s Work Scholar Program, please visit aperture.org/internships.

The post The Business of Photography: A Conversation with Mary Virginia Swanson appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers