Aperture's Blog, page 143

February 23, 2016

Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima

Visionary director Haile Gerima emigrated from Ethiopia to the United States in the late 1960s. Exploring African and African American narratives, his works, sometimes born of dreams and visions, have inspired a new generation of filmmakers. This article is a preview of Aperture magazine’s “Vision and Justice” issue, guest edited by Sarah Lewis, which will be released in May 2016.

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

By Sarah Lewis and Dagmawi Woubshet

Dagmawi Woubshet: I think it’s a fair statement to say that one can think of Haile Gerima’s work as a meditation on love. I am reminded of James Baldwin in The Fire Next Time, who says that “love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” I think your films, Haile, actually allow us those kinds of self-revelations. And so I hope we can glean from the questions that we’ve come up with, the different idioms of love, and the different inflections of love that show up in your body of work.

Sarah Lewis: Thank you, Dagmawi. I wonder, Haile, if you would speak to us a bit about the courage it took to begin your journey from Ethiopia to Chicago, studying theater in the 1960s, to Los Angeles studying film to tell stories that have moved us all?

Haile Gerima: First, I just want to thank you both because it didn’t really occur to me to … I’m so alienated about the whole idea of love. I’m not sure I deserve such an honor because of the few films I have done in the world. I didn’t have the resources to have done more. Sankofa (1993), I should have done at least ten sequels because I have fifteen scripts. And so, in a world where one is denied the tools and resources, in that kind of dire state of struggle to gain my right to tell a story, to think of such very insightful emotional dynamics in my work is really a blessing. Now for me, I am a human being who’s been lied to. So when I shoot, it’s, for me, a rifle, it’s a gun, it’s an explosion. Every film is a staircase to respond to my interest to cleanse my own state of occupation. It’s kind of a decolonizing journey, and no one is going to finance me, no one is going to say, “Here’s money to tell another story.” Unless she drives Miss Daisy I have no chance of being financed by the present arrangement.

Woubshet: We wanted to ask you, since you are really the product of two civilizations—an Ethiopian civilization and also an African-American civilization—if you could talk about the insight that each has given you about love, and also the resources that each civilization has given you in becoming the kind of filmmaker you are.

Haile Gerima, Still from Ashes and Embers, 1982. Courtesy the artist

Gerima: Well, let me put love aside for a second because I’m the least developed person to discuss love. But let me speak about these two situations that I find myself in. I think, for example, World War II began in Ethiopia. Ethiopia was the first country where Mussolini waged war and Ethiopians were the first casualties of poison gas. Their history is still not told. Why? Because we are in this Eurocentric educational university, global university, where our instincts and tendencies are managed and conducted by this higher empire, which is the United States empire. I am the product, the grotesque and disciplined product, of the American empire. This is how I think we have to look at my work, that the American empire was where Haile Selassie ran because of the trickster British colonial idea of colonizing Ethiopia. To prevent that, he went into the bosom of Roosevelt, and Ethiopia, unlike its past history, became in the orbit of the American empire. And so our educational systems were changed. Twenty-one-, eighteen-year-old American Peace Corps came to teach us. Local Ethiopian educational system was completely obliterated, which also obliterated my father, who wrote plays and never knew Shakespeare nor Molière. His plays were displaced and my immediate inheritance to be a storyteller in Ethiopia was completely destabilized.

And so everything I do is to reconnect my disconnected umbilical cord. My focus is completely resistance, and love in that whole metrics is really the fact that we dare to still love. It amazes me. I’m not yet developed. I’m not going to claim my films do that. I just want to hear you guys tell me it does a little bit here and there. But the point is … and the African-American now comes in here. I came to America and I was, in response to my conditioning … The first demonized population in Chicago I tried to run away from were African-Americans. But by the time of the Black Power Movement, 1968–69, I had the biggest afro of any African-American. I am an Ethiopian citizen. I don’t intend to be an American citizen, but I have a big, big … owe to African- Americans for awakening me to want to find out who the hell I was, and that is not a simple debt.

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

Woubshet: One has to prepare in advance to watch your films because they are emotionally very heavy. It’s not Friday night at the movies, you know. Even though the characters achieve some form of self-revelation or self-consciousness toward the end of your films, they go through immense amounts of pain and suffering. They’re deeply haunted characters, and it seems, in fact, a signature of yours is to thrust their interior, psychological turmoil on the screen for us. And you are relentless about that. Can you talk about how your deeply troubled characters ultimately gain some form of self-possession?

Gerima: Well, that’s very nice, and thank you. I’m going to tell you there are two things in motion. First, in general, just even the idea of storytelling—the aesthetics, the accent, and the structure of storytelling still has to operate in the empire of this Eurocentric America. America is really European aesthetics. In general, the vocabulary of America is a white supremacist vocabulary and Europe lives in America with all of us being the ambassador and emissary of its vocabulary. My struggle is not only what I want to tell, but it is the very form of storytelling that I am in constant struggle with. Am I succeeding? No, it’s an imperfect struggle that is on a journey of someday finding this stable, coherent, narrative gratification. And so, the intensity that I think you are talking about comes from the fact that I am in a struggle. That is part of it.

Black people that I know are struggling every day. In struggle there is intensity and resistance, and there is also love in that intensity. To dare to love within the circumstance of an intense struggle is an amazing situation. I cannot claim I have succeeded to do that. I don’t know if I answered you, but I improvised my way through.

Lewis: The idea of love as connected to a right to have agency about your future seems to be a through line in your films; a right to live out your potential. We see this in Sankofa, in Bush Mama, (1979). Can you speak to us more about this focus on right to the future as a motivator?

Gerima: Well, you know, I think … Frantz Fanon’s idea that every generation has a responsibility some fulfill and some betray. Out of that I decided that some of us come on this earth to be fertilizers. I live amongst fertilizers knowing there will be firebrand children that will not have the same entrapments that postpone them from grabbing their historical making process.

Haile Gerima, Still from Sankofa, 1993. Courtesy the artist

Lewis: We wanted to also speak about the segments and codas you create by having the sounds of everyday activities, specifically in Harvest: 3,000 Years (1976) and Ashes and Embers (1982), whether it’s cattle sounds in the harvest or the creaking of the swing with the grandmother at the end of Ashes and Embers as she is telling her story to Liza. We wondered if you could just tell us more about how the stories and their environments have inspired your journey to filmmaking.

Gerima: When I came to Chicago and finally UCLA, I had two choices: to reconnect with something that has been very insistent in my life; to reconnect to the melodies and the storytelling. I have students who are always plugged by earphones, furthering their own mental conditioning, and could not build sound tracks when they do their films.

The crackling fire is the sound track of my grandmother, which I did in Ashes and Embers. Ashes and Embers, for example, is built on the whole crisis I was having. When does a generation listen to the passing generation? I was working on this thing jazz musicians call the ripe moment. When is one ripe to hear the truth?

I think all my other films did benefit a lot because even structurally I wanted to abide by the idea of when does one see the light. What kind of generational struggle takes place for that generational transaction? Is it when you want it or when the kid is ripe, and is the kid ripe now or one hundred years later? That is what I learned.

Woubshet: Following up on that, your films have such a clear political content to them, but then you get these long interludes of everyday life, the quotidian.

Lewis: There is an ethic of care you have created, a legacy at Howard University and in Washington, D.C. You have been there for thirty years now and with your students, you teach them with a level of love that is so profound to hear.

Gerima: I think black people carry a genomic story in their body in this country. If they don’t want me to help them activate it then I’m useless because I am not a teacher that is there for salary. I declined many film school offers in Europe to go to Howard because I was looking to teach black kids who I felt didn’t have to go, like me, to UCLA to spend more time justifying their story is normal instead of the technical discussion in white schools. I went to a school where I want to have black kids like me who are really in urgent situation to tell the story of their grandmother or their grandfather. I said, “I want to be a part of a school like that.”

Sarah Lewis, guest editor of “Vision & Justice,“ is Assistant Professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies at Harvard University. Dagmawi Woubshet is Associate Professor of English at Cornell University.

This article, which will be published in Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice,” is adapted from “Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima,” originally published in Callaloo, vol. 36, no. 3, Summer 2013, and reprinted courtesy of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 18, 2016

Higher Ground

Vittorio Sella, born in the foothills of the Italian Alps, combined his passions of photography and mountaineering to capture the elevated beauty of the world’s most inhospitable places.

By Alexander Stille

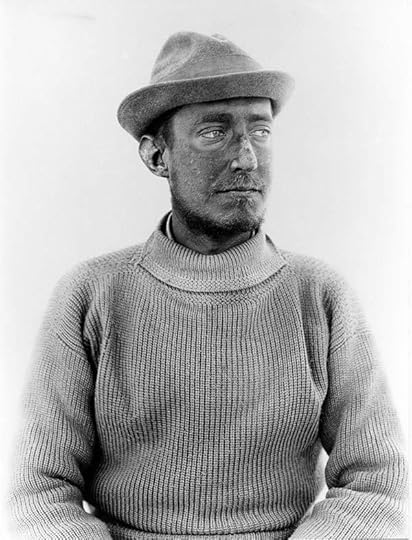

Vittorio Sella, Luigi Amadeo di Savoia-Aosta at age 24, just after returning from Mt. St. Elias, 1897

Mountains are powerful symbols of eternity, of the immensity and grandeur of nature, towering above and indifferent to human civilization and history. Yet our interest in and preoccupation with mountains—climbing, studying, painting, and photographing them—are the products of a very recent history.

High and remote mountains, which earlier European generations avoided, viewing them as dangerous wastelands inhabited by the poorest and most backward people, suddenly took on new appeal in a rapidly industrializing nineteenth-century Europe. Romantic poets longed to escape from the “dark Satanic mills” (William Blake)—the factories beginning to dot the landscape—and from the “getting and spending” (William Wordsworth) of growing urban life. Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley all wrote about the powerful, formative experiences of their visits to Mont Blanc and their encounters with the mighty Alps. “High mountains are a feeling, but the hum / Of human cities torture,” Byron wrote. While the eighteenth-century traveler concentrated on the ancient sites of Italy and Greece, the Alps became an obligatory Grand Tour destination for cultivated young English gentlemen of the nineteenth century. John Ruskin, Victorian England’s most influential tastemaker, proclaimed, in 1856, that “mountains are the beginning and the end of all natural scenery.”

Vittorio Sella, Crevasses, Glacier du Chardon, August 3, 1888

This sudden awareness of the mountains, together with improved transportation and technical capacity for systematic mountain climbing, tempted Europeans not just to admire the mountains from below but to see the world from their heights. In the mid-nineteenth century there was an active scramble—a kind of friendly, international competition among a new class of gentleman mountaineers and explorers—to reach the remaining unexplored peaks of the Alps, the last frontier of nature in Europe untouched by man. The ascent in 1854 of the Wetterhorn—one of the highest peaks in Switzerland—by British climber Alfred Wills was an international event, ushering in the “golden age” of mountaineering and the formation of the Alpine Club in 1857.

Vittorio Sella, mountain-photography pioneer, was born in 1859 into a family of explorers and photographers in the town of Biella, in the foothills of the Italian Alps, where his family ran a successful wool factory. A few years before Sella’s birth, his father published the first major treatise in Italian on the new science of photography. When Sella was four years old, his uncle, Quintino Sella, led the first expedition to the top of Monte Viso (or Monviso), the highest mountain in the French-Italian Alps, and in 1863 founded the Club Alpino Italiano, which remains Italy’s principal mountaineering club.

Vittorio Sella, The Duke of Abruzzi and guides climbing through Chogolisa Icefall, 1909

Sella’s father died when Sella was just sixteen, leaving him in the care of his uncle, an important and emblematic figure in nineteenth-century Italy. After getting an undergraduate degree in engineering, Quintino Sella studied mineralogy at the École des Mines in Paris, then returned to Italy, where he taught mathematics and mineralogy. During his frequent ascents, he gathered samples of unusual rocks, assembling one of Italy’s most important collections of minerals. He was placed in charge of a new royal museum of mineralogy in Turin, which was the capital of the Duchy of Savoy, home to what would become the Italian monarchy. Quintino Sella entered politics in 1860 and became Italy’s minister of finance in 1862, after Italy was unified. The conquest of the alpine peaks was not entirely divorced from the politics of the newly unified Italian nation: Quintino Sella shrewdly included a member of parliament from Calabria in his ascent of Monte Viso, making the climb a public moment of patriotic unity.

Vittorio Sella, Alessandro Sella, Joseph Maquignaz, and Gaudenzio Sella on the Wetterhorn, July 19, 1886

Vittorio Sella synthesized his father’s expertise in photography with his uncle’s passion for mountaineering. When he was nineteen he made his first serious effort at alpine photography, dragging heavy, borrowed photography equipment up to Monte Mars and making his first panoramic views of the Alps. At the time, he was working with extremely cumbersome and volatile wet-collodion glass-plate negatives. With this method a photographer needed to coat each plate with a silver-nitrate solution and develop each shot within ten or fifteen minutes of exposure, while the negative was still wet. This meant that Sella had to carry and improvise a portable darkroom up in the Alps. Despite the technical difficulties and uneven photographic results of these initial efforts, Sella persisted, learning a great deal through the trial and error of an art that was still in rapid evolution. “From 1880,” he wrote, “I made up my mind to combine photography with Alpinism, and I took almost no interest at all in the lower parts of the mountains, and confined myself to photographic work on the summits, and to those higher regions of the Alps, which were little known and had not been photographed.”

Fortunately for Sella, photographic technology was evolving; particularly revolutionary was the development of the gelatin process—glass plates with a dry photographic emulsion—which meant that negatives could be prepared in advance and developed later. The new dry negatives were both more convenient and exceptionally sensitive, allowing for shorter exposure times and remarkable photographic detail.

Vittorio Sella, The Karagom Glacier as seen from its right moraine, Caucasus, 1890 © Fondazione Sella and courtesy Decaneas Archive

Sella was a pioneer in mountaineering as well as photography. In 1882, he led the first group to successfully climb the Matterhorn (known as Cervino in Italian), the largest mountain on the Italian–Swiss border, during the winter—an achievement hailed by the Alpine Club as “beyond doubt the most remarkable that has ever been made during the winter season.” Later that same year, in a fever of excitement, he wrote to the camera company J. H. Dallmeyer in London: “I beg you to undertake immediately the camera for plates 30 × 40 cm described in my letter. I beg you to make it in the best mahogany, with every care possible, as I will serve myself of it for taking photographs in the high Alps…Here, we have splendid weather and I burn with impatience to start photographic excursions.”

The camera that Sella acquired from J. H. Dallmeyer weighed nearly forty pounds; each glass plate, almost two. Despite this exceptional challenge, Sella managed to get the camera and plates back up the Matterhorn, where he began to make some of the pictures that established him as the premier mountain photographer of his time.

Alexander Stille is San Paolo Professor of International Journalism at Columbia University and a regular contributor to The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and La Repubblica.

To continue reading the full article, buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Higher Ground appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Highway Kind

Crossing the United States in her beat-up van, Justine Kurland pictures America’s tangled sense of itself.

By David Campany

Justine Kurland, Like a Black Snake, 2008

The actualities and the myths, the facts and the metaphors. Justine Kurland photographs America’s tangled sense of itself. How do we see when seeing has been so anticipated by images? Through the filter of all that has gone before, can a photographer describe lives and places anew? In the last few years Kurland’s pictures have emerged in groupings, with names like This Train Is Bound for Glory and Sincere Auto Care. Gathered here in eloquent sequence is a small sample from her forthcoming book with Aperture.

A train snakes like a toy across the desert between Nevada and Utah. The view looks unchanged for decades but those are boxcars of cheap consumables from China, bound for Walmart. The photographer’s son, Casper, a regular companion on these trips, throws back his head and refreshes himself. He looks like a feral creature, a pioneer, and a twenty-first-century boy, chugging juice from a plastic bottle. The excess trickles down his belly to his diaper. When Casper was six, Kurland took a teaching job. It reconnected her with the work of Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and the long tradition of intelligent documentary photography. For now, this is her idiom—wide, generous, and testing.

Her road trips are long and her van is eleven years old. With 250,000 miles on the clock, it gets patched up often. Since nobody feels entirely positive about cars these days, breakdowns and crashes feel like larger symbolic deaths. But as Evans wrote in “The Auto Junkyard,” a 1962 photo-essay published in Fortune, “There is a secret imp in almost every civilized man that bids him delight in the surprises and in the mockery in the forms of destruction. At times, nothing could be gayer than the complete collapse of our fanciest contrivances. Scenes like these are rich in tragicomic suggestions of the fall of man from his high ride.”

Justine Kurland, 280 Coup, 2012

The auto yard is a place of pragmatic resurrection. Indeed, the fall of man, or more exactly fallen men, have their own erotic pathos. Kurland’s pictures of mechanics and car culture are touching and affectionate. They leave the ambivalence to us. Casper had his own little fall from Mom’s parked van, catching his mouth on the bumper. That’s his tooth in his hand.

One day she met a man who looked uncannily like Casper, all grown up and coming down from a junkie’s high. With a head full of worries about keeping her boy safe and the knowledge that he won’t be hers forever, she photographed this man. She accepted him, watching him almost pray with his hands around a Coke. Her camera is respectful but it wards off the fears.

Justine Kurland, What Casper Might Look Like if He Grew Up to Be a Junkie in Tacoma, 2013

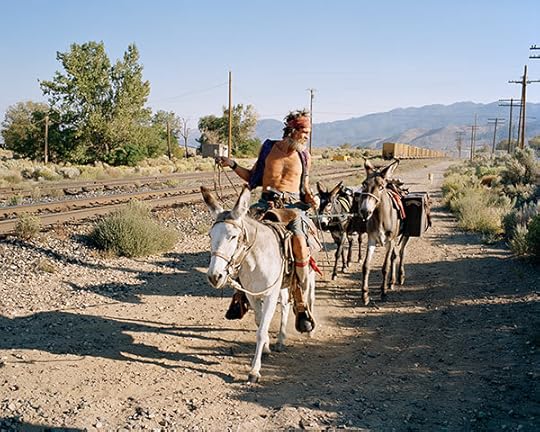

And here is Cuervo, on horseback, no car in sight. Kurland got to know him and photographed him over three years. He can hunt, prepare food, and light fires without matches. His past includes drug running and incarceration in Mexico. He has just crossed the Sierra Nevada with his animals. Kurland recalls his words: “I’m a man with a man’s needs, and if you want to get some photography done you are going to have to satisfy my needs.” She walked away. “When I came back he was completely naked. Somehow that was the final straw. I haven’t talked to him since.”

We all know the easy failings of men. The pride, arrogance, narcissism, and fragile vanity. Yet, nobody is quite sure what a man is supposed to be. Myth and history were once on his side but no longer. In these photographs, made with young Casper at her side, Kurland offers her own brave contemplation of it all.

Justine Kurland, Cuervo Astride Mama Burro, Now Dead, 2007. All photographs courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

David Campany’s most recent book is A Handful of Dust (2015).

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Highway Kind appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Open Roads & Invisible Borders

Since 2009, a photography collective has embarked on five road trips across West and Central Africa, creating a kaleidoscopic portrait of everyday life. For their latest trek, the group drove from Lagos to Sarajevo, a bold endeavor that would test their resolve.

By Sean O’ Toole

Emeka Okereke, Waiting, Rosso (Mauritania–Senegal border), 2014

In early November of 2009, a group of ten Nigerian friends—among them photographers Uche Okpa-Iroha, Amaize Ojeikere, Emeka Okereke, and Ray Daniels Okeugo—piled into a black VW van christened “Black Maria” and headed east out of Lagos on the coastal expressway toward neighboring Benin. Their plan: to spend four days driving a 1,400-mile route from their home city to Bamako, the capital of Mali, where they intended to catch the opening of the eighth edition of the Bamako Encounters, Africa’s most important photography biennial. Four days to drive roughly the same distance separating New York from Miami. Plotted on a map it looks easy. But maps don’t account for muddy quagmires that sometimes pass as roads in the tropics, nor do they anticipate delays posed by lethargic and corrupt immigration officials staffing West Africa’s many border checks. Maps simplify reality; they can make the foolhardy seem doable.

A week after they embarked on their overland journey across Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Burkina Faso to Mali, the group of travelers participating in the inaugural road trip of the Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographers Organisation, an artist-led nonprofit that has now coordinated five completed expeditions, arrived in Bamako by interstate bus. Despite a breakdown in Accra, the Ghanaian capital, they had made it, albeit three days late. Bamako’s collegial photography biennial, which that year was thematically concerned with material and symbolic borders, was, however, still in full swing.

Ray Daniels Okeugo, Nna Olopa, Lagos, Nigeria, 2011

Unbeknownst to the travelers, during their journey their episodic blog had gained a small reading public among the photographic community gathered in Bamako. Predating the launch of the photo-sharing app Instagram by a year, their blog, which is still accessible online, is surprisingly text heavy. Updated by various members, notably the poet and writer Nike Adesuyi-Ojeikere, it detailed the group’s various encounters with feckless moneychangers and helpful strangers. It also chronicled the group’s cumulative frustrations as it navigated spatial and temporal thresholds, and crossed political and psychological boundaries. “We took off like a bunch of novices and thought we would be allowed to cross borders without a thorough explanation,” Okereke told me in 2012. The group’s idealism was dashed at Seme, a border post between Nigeria and Benin, where, Adesuyi-Ojeikere writes, they were held up for two hours and paid “official and unofficial taxes” before continuing.

By the time their van broke down in Accra, the group’s enthusiasm for observing Africa’s diverse realities, a core tenet of the project, waned as the “why not?” attitude that kick-started the inaugural journey ceded to the actuality of life on the road. “With no van, and living from minute to minute in the hope that the repairs would soon be done and we would hit the road again, we did not dare venture far from base,” remarked Unoma Giese, a former stockbroker turned artist, of the layover in Accra. The constraints of travel, she continued, demanded a continual regrouping and rearranging of priorities.

Ray Daniels Okeugo, Smuggler, Koussiri (Cameroon–Chadian border), 2011

Invisible Borders is a gregarious project. It is also, notably, a durable, Afrocentric, mobile photography platform that has outgrown its early origins as an informal Lagosian thing. At heart, though, it is a sociable aggregation of like-minded photographers. Named by photographer Uche James-Iroha, a participant in the first trip, this organization traces its origins back to an earlier photographic collective. In 2001, following their participation in that year’s edition of the Bamako Encounters, four Lagos-based friends—including James-Iroha and Ojeikere, son of the famed Nigerian portrait photographer J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere—founded Depth of Field (DOP), a loose affiliation of individuals rather than an aesthetic movement bounded by a common style. The collective later expanded to include Emeka Okereke, the current artistic director of Invisible Borders.

The remit of DOP’s photography was diverse, ranging in subject from James-Iroha’s allegorical portraiture to Ojeikere’s abstracted documentary studies of market goods and Okereke’s more naturalistic observations of urban soccer. After a brief flurry of exhibitions in Berlin, London, and New York in the mid-aughts, the collective’s momentum dissipated, prompting Okereke to act. “He felt that they were not doing enough artistically and project-wise to further their initial success,” says Akinbode Akinbiyi, a Berlin-based Nigerian photographer who is a key mentor and ally of the group. “Initially he launched the idea of the intercontinental travels to his closest colleagues in DOP.” They liked his idea. The maiden journey of Invisible Borders included three DOP members.

The warm response to the 2009 road trip project prompted Okereke to develop it into an annual event. In 2010, a journey was undertaken from Lagos to Dakar, the Senegalese capital city and host, since 1992, of Dak’Art, a visual arts biennial. Departing once again along the trans–West Africa coastal highway, the road trip included visits to Cotonou, Lomé, Accra, and Abidjan, before detouring inland to Bamako, bypassing the troubled states of Liberia and Sierra Leone. At Diéma, a Malian settlement between Bamako and Dakar, the group met three Nigerian women operating a roadside eatery, which they had opened after a smuggler abandoned them while en route to Spain. As was custom early on, a group portrait was produced of the Nigerian adventurers with their enterprising compatriots.

Ala Kheir, Equilibrium, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. All photographs © the artists and courtesy Invisible Borders

In its earliest iterations, Invisible Borders was overwhelmingly Nigerian in its makeup. Since 2011, however, when the group navigated overland from Lagos to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to join the Addis Foto Fest (with one flight connection between N’Djamena, Chad, to the Sudanese capital city of Khartoum), they have taken on a more pan-African appearance. “It began with what seemed like a Nigerian collective, but the main idea is to make it a platform for artists from different parts of the African continent,” Okereke explained in 2012.

At the time, he was planning a fourth trip: from Lagos to Lubumbashi, a mineral-rich city in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo and site of the Lubumbashi Biennale. This southerly trip, which included participants from Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Rwanda, and South Africa, was marked by an epic five-day struggle on muddy roads between Calabar, a city in southern Nigeria, and Mamfe, in neighboring Cameroon. Encountering roads of thick, golden-brown clay, they hired “mud workers” to aid their passages, and later argued with officials who imposed a fine when a vehicle owned by a Chinese construction outfit collided with them. The last-minute postponement of the Lubumbashi Biennale saw the trip rerouted to the port city of Libreville, Gabon, where participant Jide Odukoya, from Nigeria, made a portrait series of his expatriate countrymen living in this oil-rich state. By this time only Okereke and Ray Daniels Okeugo, a photographer and Nollywood actor who died in October 2013, remained of the original group of ten Nigerian friends who founded Invisible Borders.

The group’s malleable membership is less important than its modus operandi, which by 2011 had matured from spontaneous adventurism into a sustained exercise in transcontinental networking and photographic encounter. The latter action, to photograph, is an important facet of the collective, but also possibly the hardest thing to coherently track. Their work is widely and consistently exhibited—including appearances in The Idea of Africa (re-invented), a 2010 photography exhibition at Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland; The Ungovernables, the 2012 New Museum Triennial in New York; and All the World’s Futures, curator Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition at the 2015 Venice Biennale—but it is somewhat misleading to speak of an Invisible Borders style.

Often thought of as a photographic collective, Invisible Borders has evolved to include video, site-specific performances, and a good deal of writing. Although diverse, this creative output is linked by an impressionistic and sensorial thread, exemplified by Nigerian author Emmanuel Iduma’s blog posts and South African filmmaker Lesedi Mogoatlhe’s short web clip of Cameroon-based singer Danielle Eog Makedah. However, for the group’s career-defining Venice showcase, Okereke—assisted by Akinbiyi, Iduma, and photographer Jumoke Sanwo—emphasized the group’s lens-based work. Multiplicity and diversity trumped the discrete image in their photographic selection: a collage of densely clustered reportage, documentary, and pictorial images represented Invisible Borders.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and editor based in Cape Town, South Africa.

To continue reading the full article, buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Open Roads & Invisible Borders appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

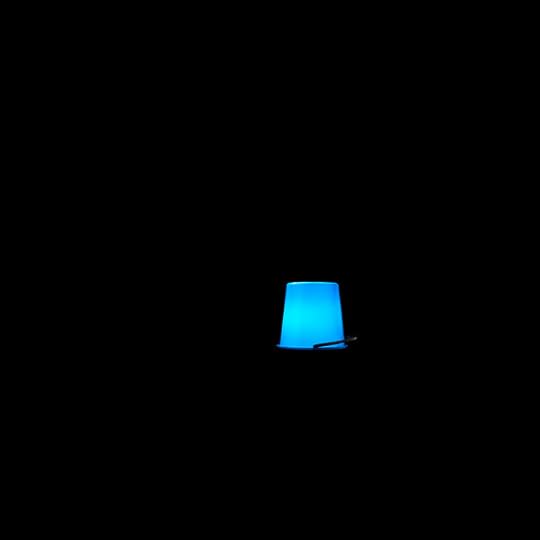

Into the Void: Taryn Simon in Conversation with Kate Fowle

Since 2006, Taryn Simon has collected objects and documents in a black field measured to the exact dimensions of Kazimir Malevich’s painting Black Square (1915). Set to end on May 21, 3015, and created in collaboration with Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation, Simon’s newest iteration of the project, a journey into the future, is the ultimate homage—a black square of vitrified nuclear waste. Black Square XVII is now a permanent installation at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, where the ongoing series will be presented in spring 2016. With Black Square XVII, Simon explained, “I wanted to make a work not for my generation, nor my children’s generation, but for a distant future to which I have no tangible relationship.”

Taryn Simon, Black Square, 2006– Void for artwork. Permanent installation at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow

Kate Fowle: Black Square began in 2006 and is ongoing, making it the longest running project you have embarked upon so far. At the same time, it has never been exhibited as a series, or perhaps it’s better to say not exhibited as a complete story. Does this project enable you to structure, or think out loud, about various subjects and ideas that become important to you during your research for other series?

Taryn Simon: It was a needed liberation from the tight margins of my projects. I’ve worked for so long in very closed and serial projects—ones that take consecutive years to produce. The Black Square series has allowed me to think and work differently.

KF: It’s “action research.”

TS: I make the individual works for Black Square whenever I feel like it—not in a controlled time slot. Within the “black” I’m able to dig into the lists I collect of singular ideas. I guess the irony is that I couldn’t escape my taxonomic instinct, as I put all of these distinct subjects in the repetitive void of the black square. But, for me, it’s the messiest I’ve been.

Taryn Simon, Film still of Radon nuclear waste disposal plant, Sergiev Posad, Russia, 2015–ongoing

KF: Let’s talk about the premise of this series. Why did you choose to use Kazimir Malevich’s painting Black Square 1915 as an organizing principle? What is your own story in relation to this work?

TS: The Black Square—or the great nothing, a zero form, as Malevich described it—was the first icon without an icon in Russian painting. This average shape, size, and color was inscribed with countless political and mystical dimensions. A very simple, dull gesture became revolutionary. For years I’ve used the shape, color, and scale of Malevich’s square as background to a number of representations of man’s inventions, or man’s disruptive marks. Then the great nothing became a big something—researchers using X-rays have recently discovered that beneath the paint of the Black Square lay secret messages and earlier paintings. Ironically, the painting itself suddenly takes on overtly secretive and hidden characteristics, like many other subjects of my work. On a more personal note, Malevich’s Black Square was created during a period of Russian history that led to my family’s departure from the country.

KF: The works share a format, but their contents are all very different.

TS: The subjects of the black squares come from my imagination, things I’m reading or lists I’ve made through the years of ideas to consider for projects. There’s no real reason behind them, just things that have a certain solitude or inherent contradiction.

Taryn Simon, film still of Radon nuclear waste disposal plant, Sergiev Posad, Russia, 2015–ongoing

KF: Can you describe a couple of the works and how they came about?

TS: Black Square IV pictures “The Blaster,” an anticarjacking system installed beneath vehicles in South Africa. It’s a flamethrower activated by a driver or passenger of a car under attack. Black Square V includes a shadowed image of Henry Kissinger. Black Square XII documents The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which purports to be the minutes of a meeting between Jewish leaders outlining their plan to control the world. Despite having been exposed as a false document, it continues to be reproduced in many languages and distributed throughout the world. Black Square XIII pictures a functional 3-D handgun printed in my studio in nine hours and forty-eight minutes, using black ABS plastic. Black Square XVIII looks at the variations in dust from different nations.

Taryn Simon, Black Square VI, from Black Square, 2006– Blue buckets were mounted atop civilian vehicles in Moscow to protest the misuse of emergency blue rotating lights by VIP businessmen, celebrities, and officials to bypass Moscow traffic. All works courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery

KF: The most recent iteration of the Black Square is a sculpture.

TS: Yes, its start was a fantasy that developed into a long-term project with Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. The goal was to construct a black square made from vitrified nuclear waste that would hold within it a letter that I had written to the future. The process of vitrification converts radioactive waste from a volatile liquid to a stable, solid mass resembling polished black glass. It is considered to be one of the safest and most effective methods for the long-term storage and neutralization of radioactive waste. At long last, in 2015, we began fabricating the black square, which will be stored in a steel container reinforced with concrete, situated within a holding chamber surrounded by clay-rich soil, and then placed at the radon nuclear waste disposal plant in Sergiev Posad, located seventy-two kilometers northeast of Moscow. It will reside at the radon facility until its radioactive properties have diminished to levels deemed safe for human exposure and exhibition—approximately one thousand years after its creation.

Kate Fowle is the chief curator at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow and Director-at-Large at independent Curators International in New York.

To continue reading the full article, buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Into the Void: Taryn Simon in Conversation with Kate Fowle appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Arrivals and Departures

On the Trans-Siberian Railway, Jacob Aue Sobol discovers the texture of societies in transition.

By Pico Iyer

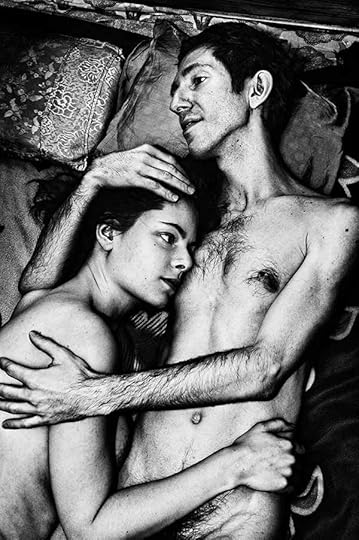

Jacob Aue Sobol, Moscow, Russia, 2012

Fierce eyed in their filmy black dresses and off-the-shoulder numbers, the girls of Ulaanbaatar were strutting down the corridors of the gleaming new Shangri-La Hotel last August as if in Bangkok or Shanghai. Some were carrying bags from the shiny Vuitton outlet down the street; others had no doubt been pastoralists on the grasslands just years before. Every time the branch train of the Trans-Siberian Railway stops in the Mongolian capital, fresh faces—new thoughts of faraway worlds—flood out to transform a world of horses and heart-stopping emptiness. “You know,” a Mongolian friend said to me just before heading to the bar Naadam, “Genghis Khan was the WTO of the thirteenth century.” What he didn’t need to say was that what used to be a trade of spices and tea is now very often one of promises and dreams.

As I sauntered among the Thai massage joints and “Vegas” nightclubs of Ulaanbaatar last summer, I might have been in the stark and sometimes unsettling world that Jacob Aue Sobol has made his own. Since 2012, on one month-long trip after another, the Danish wanderer has been opening up a boldly contemporary Asia, as he rides the Trans-Siberian and its branch lines, taking us into Chinese, Russian, and Mongolian lives. At every stage, we feel not just the textures of societies in transition, but something inward and very private on the far side of the tracks. The mixed feelings of a traveler slipping out after a quickie, the unease of arriving in a place that is itself on the move (or even, in Mongolia, on the hunt). The view not through the window of the celebrated train, but from within a shuttered room, looking back.

Jacob Aue Sobol, Moscow, Russia, 2012

It’s easy—perhaps too easy—to say that the tourist wants to go somewhere while the traveler likes to linger. The tourist hopes to catch something through his lens, while the traveler seeks to surrender, even to be claimed by a surprise in very real life. Yet Sobol’s work goes even deeper than most travelers, by seeing what is left behind when the train pulls out, and by seeking out the shadows,

the unintended consequences, of a journey that leads not just to discovery but confrontation. Though the title of his ongoing series is Arrivals and Departures, he clearly has little interest in the names and times listed on railway-station announcement boards. Destinations are less important to him than those feelings—of guilt, of disquiet, of wanderlust—that arise whenever a wayfarer draws close enough to a local to feel (or impart) real hurt. I think of Jackson Browne’s haunting line about running for a morning flight “through the whispered promises and the changing light / Of the bed where we both lie.” With the emphasis on “lie.”

Jacob Aue Sobol, Moscow, Russia, 2012

As a traveler through the alleyways of contemporary urban Asia for the past thirty-two years, I’ve always sought out those scenes that can’t be caught on any screen. I’ve been interested in why, a few miles from the wind-whipped silences of Mongolia, a “Luxury Nail Spa” is opening amid crowds of Dubai-worthy glass towers, and why Mongolian Airlines is showing Two Night Stand, of all Hollywood comedies, as we fly into the land of Genghis Khan. But looking at Sobol’s work, I’m reminded of how we writers will always lag behind: it’s not so much that a picture is worth a thousand words as that it can grasp a thousand silences. The unspoken moment; the impenitent stare; every murmur or grunt or tremor that no words can begin to transcribe. In the age of the selfie, Sobol’s camera looks out—and finds a brazenness that conceals at least as much as reticence does.

Jacob Aue Sobol, Moscow, Russia, 2012

In China, bullet trains are being built to travel over 300 miles per hour; coming in from the airport in Shanghai, I rode a Maglev train that whisks passengers past avenues of skyscrapers at 268 miles per hour. In Russia, the ghostly gray monuments of Leninism have given way, almost overnight, to over-the-top dance clubs and, in Moscow alone, eight separate Rolex outlets. Even in Mongolia, I found last summer, the memory of the worldly conquerors known as the Golden Horde is being trumped by the prospect of hoarded gold. Yes, Sobol’s inky black-and-whites take us past the glitter of the twenty-first-century Silk Road into more uncertain moments that recall the elemental, even predatory street poetry of Daido Moriyama or Jack Kerouac. This comes from having the patience to step off the train and walk slowly into the lives and bewildering landscapes all around.

Jacob Aue Sobol, Moscow, Russia, 2012. All photographs © Jacob Aue Sobol and courtesy Magnum Photos and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

These images stay with me in part because they give back so little, and what they do give back is not consoling. They’re antisnapshots of a kind about the displacing truth of travel—that places are often resistant to our gaze, and the deeper we enter them, the more we lose all sense of where we are. In this context, the stress on Trans-Siberian Railway falls emphatically on “Trans”—the sense of movement, of crossing frontiers, of stepping toward a human contact that will always remain out of reach. Less transcendence, you might say, than transgression. And—as in the most memorable trips—no answers, but questions that keep on turning inside of you, forever.

Pico Iyer is the author, most recently, of The Art of Stillness (2014).

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Arrivals and Departures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Odyssey

Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Traffic, 2013, from the series Eurasia. Courtesy the artists, RaebervonStenglin, Sies+Höke, and Peter Lav Gallery

“The tourist hopes to catch something through his lens, while the traveler seeks to surrender, even to be claimed by a surprise in very real life,” celebrated travel writer Pico Iyer notes in his introduction to a portfolio of Jacob Aue Sobol’s photographs made while riding on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The unexpected route, the captivating spell of wanderlust, and the lure of the unpredictable bind the images in this issue. From early twentieth-century expeditions like those of Vittorio Sella, who created sublime views of the world’s most treacherous mountains, to the recent documentary projects of Invisible Borders, a West African photography collective, the camera is central to the journey—not just a means to prove the trip was made. Even so, for Emeka Okereke, the artistic director of Invisible Borders, “The purest form of the project is while we are on the road.”

Among the peripatetic wanderers brought together in these pages are Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, who drove a four-wheeler from Switzerland to Mongolia, photographing unfamiliar landscapes and futuristic architecture, and Justine Kurland, who has crossed the United States in a weathered van, adding thousands of miles to her odometer while pursuing a chronicle of American drifters. Precedence can be found in the travelogues of Wilfred Thesiger, who opted for camel over automobile in his arduous midcentury expeditions throughout the Arabian Peninsula, slowly pushing forward into the desert. “I had no desire to travel faster,” he wrote. “In this way there was time to notice things.”

Likening her artistic process to an “unconscious journey,” Tacita Dean, known for her prodigious output in film, still photography, and other forms, is attracted by the hunt for found images. Her oeuvre is marked by references to personal quests: one in search of Robert Smithson’s then-submerged land work Spiral Jetty, another for a boat, languishing on a remote island, that once belonged to a doomed amateur sailor. Yto Barrada also traces the path of submerged relics. Following the “dinosaur road”—the lucrative trade of purloined fossils between Morocco and Arizona—Barrada constructs her own map of archaeological exploits, constructing a sequence of landscape collages and found paintings, published here for the first time.

Some journeys are undertaken at moments of upheaval; some maps extend past the realm of public knowledge,or into an uncharted future. In his latest project, Trevor Paglen has plunged beneath the ocean to document the Trans-Atlantic cables that carry the bulk of Internet traffic now heavily monitored by government surveillance. Taryn Simon’s Black Square contains a letter to the future, a project expected to achieve its full realization in one thousand years. But the odyssey emblematic of our time, perhaps the most pressing issue of contemporary international consequence, is the flow of mass migration across North Africa and the Middle East toward Europe. Powerfully represented by Samuel Gratacap in his series Empire, refugees from many nations have reached a standstill at Choucha Camp in Tunisia and await passage to an elusive haven. To their north, the islands of Lesbos, Kos, and Lampedusa, among many others that figured in the geography of Homer’s epic poem, form an archipelago of uncertainty. At the edge of the Mediterranean, the longest journey is still to come, the territory just beyond the horizon. — The Editors

To read more from “Odyssey,” buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Odyssey appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 17, 2016

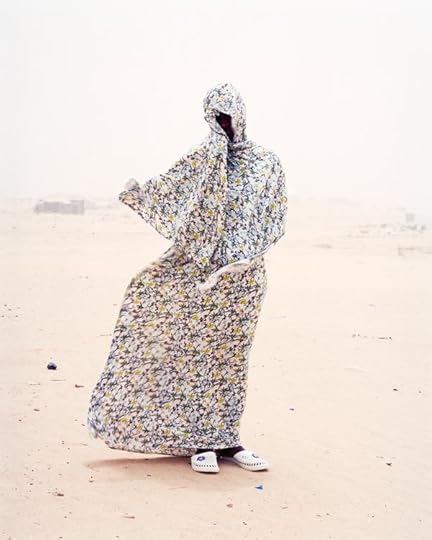

On the Cover: A Conversation with Samuel Gratacap

A young photographer reports on the odyssey of our time.

The Spring 2016 issue of Aperture features a cover image taken by Samuel Gratacap at a transit camp in Tunisia. Since 2007, the 32-year old French photographer has followed the lives of refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean, documenting moments of departure—and the emotions of waiting—at sites including the Italian island of Lampedusa and a detention center in Marseille, France. At its peak of operation, the transit camp at Choucha, where his series Empire is set, received upwards of 200,000 migrants, many fleeing the crisis in neighboring Libya and others escaping conflicts in West Africa and Southeast Asia. One of the most pressing debates of current international consequence, the flow of political and economic refugees toward an elusive haven in Europe has been the subject of intense coverage in news media and photojournalism. Resisting the sensational, however, as Bronwyn Law-Viljoen writes in her introduction to Gratacap’s work in Aperture, “There is beauty in his images, but also an attempt to understand the bare-life fact of Choucha, and to avoid consigning the camp’s inhabitants to the realm of the poetic.” I spoke with Gratacap late last year, shortly after he returned from a reporting trip in West Africa for Le Monde. —Brendan Wattenberg

Samuel Gratacap, Departure day, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

Brendan Wattenberg: Do you consider yourself a photojournalist and an artist? How does your reporting on current events influence your long-term projects?

Samuel Gratacap: I’m a photographer. The main thing that pushes me to be more and more involved is the importance of the mass media in representing the topic of migration. Mass media should be concerned with making the complex issues around migration visible, but instead it is limited to making so-called news. However, some photo-editors are starting to create new ways of editing and publishing photography—at Le Monde, for instance—such as double pages dedicated to photography in the print version and portfolios online. For me, jumping between long-term projects and photojournalism is just a way to challenge my own practice, to find new fields and new forms of expression.

BW: Before Empire, you were already working on migration as a theme in Castaways and La Chance. What prompted you to become so interested and involved with this issue? How does Empire extend your previous work?

SG: Photography becomes interesting when making pictures is a difficult process, primarily for reasons of accessibility. I first became involved with migration issues when I was a student at the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Marseille. La Chance (2007–2012), my first series, is a project I created in 2007 in a detention center in Marseille for “illegals.” The underlying reason for my decision to enter the detention center was the desire to understand the conditions of imprisonment and the judicial system in France with regard to undocumented immigrants. I felt like I was moving away from reality by reading newspapers and publications that distorted figures or images, anonymous and impersonal testimonies. I wanted to go in search of a reality on a human scale, make it visible, define the contours of individual stories beyond the numbers, flows, and figures.

Samuel Gratacap, Detention Center for Migrants, Zaouïa, Libya, 2014

Castaways (2007–2016) follows seven years of work about places of confinement and transit areas related to migration routes in the Mediterranean region. The idea is to reverse the concept of borders and create a proper map, within which emerging destinies and random trips take place. Having recorded the testimonies of migrants and asylum seekers throughout my travels, I’ve noticed that it’s often at the cost of freedom of expression and reduction of their basic rights that people choose to leave their country of origin. “Undocumented,” they are forced to hide. They fall into complete anonymity, finding themselves in constant struggle with a system that doesn’t give them the chance to get out and get papers.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

Empire was my first long-term project. It was a natural extension of my previous work, but I had the desire to involve myself, like I had never done before, through a deep and immersive approach. It changed a lot about the way I photograph. I was already working on a project I started in southeast Tunisia, in the city of Zarzis, not far from Choucha. Zarzis was a port of departure for thousands of Tunisian migrants who fled to Italy just after the revolution in 2011. At the same time, the civil war and NATO attacks started in Libya. Hundreds of thousands of refugees moved to Tunisia, specifically to Choucha.

Choucha is symptomatic of the fate often reserved by the mass media for migration. These refugees and migrants went from an anonymous status to suddenly having the spotlight turned on them; they then became contemporary icons of what the media has too often presented as the “migratory drama.” But after the Libyan “crisis” and the death of Gaddafi, in October 2011, the media was much less interested in the fate of refugees. Set upon for a while, in an often spectacular time in which images play a crucial role, refugees became abruptly forgotten and undesirable.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: Empire is characterized by a form of guarded intimacy. The portraits and landscapes represent a closeness and immersion in the camp’s community. Still, you approach the story with the objectivity of an outsider. During the time you worked on Empire, how long would you stay at the camp? Did you live with refugees? How did you establish relationships and take testimonies?

SG: I first traveled to Choucha in January 2012 as a photographer accompanying a reporter. Confronted with the rules of short-term reporting, I faced difficulties in rendering an image. As a result, I decided to return to Choucha in July 2012 and start a long-term photographic and video documentary project. For two years I stayed a total of about twelve months in the field. I lived between the border city of Ben Gardane and the camp. A community of refugees from the Ivory Coast hosted me. I slept there during this time; I was very close to the people. This closeness was important for my understanding of daily life inside the camp. As my time in the camp passed, my photography evolved, but I wouldn’t say it was so intimate. I never considered myself an inhabitant of the camp. The main thing was to maintain a sufficient distance, to go further and push my work.

The reality of the camp was so complex; it was important to find a way to make it apparent, starting from a distance, and then getting increasingly closer. There is not one precise story of Choucha, but instead as many stories as the number of the people who’ve been there. I obviously missed some stories, some pictures. I forced myself to find the “right” approach and the “right” moment to document this place as the hostile environment it is. The desert, the sandstorms, the waiting, the everyday moments (the food, the hairdresser), the days of departure … Time passed slowly and people felt more and more abandoned until that decisive moment, in July 2013, when humanitarian organizations “closed” the camp and left more than three hundred people with no food, no water. Men, women, and children were rejected as asylum seekers.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: Even though Choucha is a “transit zone,” your photographs from the camp are mostly about the experience, as you say, of waiting. In fact, Karim Traoré, an Ivorian migrant who you interviewed, says that Choucha is full of “wandering souls.” The spaces they inhabit alternate between claustrophobic tents and wide-open desert horizons. In the image we’ve chosen for the cover of Aperture, of a man facing a bus, you capture a person seemingly at an impasse. Could you tell us what Choucha was like during your time working there?

SG: From 2012 to 2014, Choucha was still a refugee camp, but the living conditions had become worse and worse. The sand destroyed everything, cracking the fabric of tents that were too fragile. The wind swept everything away. This picture of a man walking in front of the bus leaving the camp is an image of a tearing, a prejudice. Departure days were both sad and beautiful for the fact that some people could go and some people no.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: In Empire and your previous series, you show quiet, often very personal scenes, such as a man having his head shaved in Choucha or young men seeking a moment of leisure in Zarzis. In contrast to news photography, which is concerned with action and conflict, why is it important to portray these moments between action?

SG: I try to portray these moments to reveal how people are occupying time. How life is still going on despite the difficulties people are facing. How they are organizing themselves to fight against the hostility of places they are passing through. At the camp, the body undergoes an “administrative” status. The evolution of the people in these areas often lasts for years: there’s zero stability; men, women, and children are in a state of precarious vulnerability. My work is about these territories of movement: the border crossings, the waiting zones for daily workers, the prisons. As well as the places related to the “rest” of the body, the paths toward a newfound identity. How does it feel when one person is, at the same time, not feeling at home and not being accepted as a foreigner? How does the body “store” both the rootlessness and the rejection?

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: How do these projects integrate photography, video, and postcards together with found materials such as personal pictures, maps, and journals?

SG: The project to which you refer here, La Chance, is about the Italian island of Lampedusa, a place of shipwreck and a paradise for tourists. Lampedusa was a popular destination in the Mediterranean before becoming an emblematic place for the arrival of migrants by boat. With the series of postcards, I tried to reveal this paradox, showing the hidden side of the island. In parallel to this work, I created photographic reproductions of documents and photographs belonging to migrants, washed -up and recovered on the beaches of the island.

Samuel Gratacap, Cemetery of clandestine boats (fig n°4), Series of 8 postcards of Lampedusa, Italy, 2011

BW: Have you been able to stay in touch with any of the subjects of Empire? Have they seen your book?

SG: I stayed in touch with many people I met in Choucha. Some of them are still in the camp; some are in the capital, Tunis; some in Italy, in France. Social networks help to maintain contact. I think that only a few people I met in Choucha have seen the book yet, apart from some who are in Tunis and Paris.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire, Paris

BW: You are currently living between Paris and Tunisia and continuing to work in North Africa, particularly in Libya. What other projects are you working on now?

SG: I’m now pursuing my work about Libya and my assignments for Le Monde. The exhibition of Empire will travel to Tunis in 2016; this is the next step. At Le BAL, particularly through my project’s exposure in the press, I realized that the exhibition could reflect the situation of the refugees in Choucha for all visitors. That’s really important for me, because the project is about Tunisia. The camp still exists. People are still inside almost five years after their arrival.

Samuel Gratacap’s work is featured in Aperture Issue 223, “Odyssey.” Selections from his series Empire will be presented by Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire at AIPAD: The Photography Show from April 14–17, 2016 in New York.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post On the Cover: A Conversation with Samuel Gratacap appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Celebration for John H. Gutfreund

![Atmosphere1[19][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154888._SX540_.jpg)

![Atmosphere1[19][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154888._SX540_.jpg)

![Lauren Gutfreund and friend[16]-horizontal[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445481987i/16657920.png)

![Lauren Gutfreund and friend[16]-horizontal[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154889._SX540_.jpg)

Lauren Gutfreund and friend

![Aperture executive director Chris Boot and board chair Cathy M. Kaplan[19][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445481987i/16657920.png)

![Aperture executive director Chris Boot and board chair Cathy M. Kaplan[19][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154890._SX540_.jpg)

Aperture executive director Chris Boot and board chair Cathy M. Kaplan

![Jim and Meg Conner[10][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445481987i/16657920.png)

![Jim and Meg Conner[10][1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154891._SX540_.jpg)

Jim and Meg Conner

![Elizabeth and Mark Levine and Aperture trustee Frederick Smith[12]-horizantal[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445481987i/16657920.png)

![Elizabeth and Mark Levine and Aperture trustee Frederick Smith[12]-horizantal[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455812081i/18154892._SX540_.jpg)

Elizabeth and Mark Levine and Aperture trustee Frederick Smith

On February 11, Aperture trustees and friends gathered to celebrate John H. Gutfreund’s twenty years of service on the foundation’s Board of Trustees. Fellow board members Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla and Celso Gonzalez-Falla hosted the fête, with cocktails and hors d’oeuvres, in their Manhattan home, where guests had the opportunity to share stories about Mr. Gutfreund and his earliest years as chairman of the Aperture Finance Committee.

Mr. Gutfreund received the warmest of receptions, as Aperture executive director Chris Boot and current board chair Cathy Kaplan toasted his remarkable record of service to Aperture, including his former post as board chair. Former trustee Mark Levine applauded Mr. Gutfreund for his leadership and warmly acknowledged his wife, Susan Gutfreund, for her invaluable contributions to the foundation. Mr. Gutfreund was presented with the Paul Strand print The Court, New York, 1924, signed by fellow board members, to commemorate the evening.

Mr. Gutfreund became a trustee of Aperture Foundation in 1996 and served as chairman from 2001 to 2005. Active in the worlds of finance, politics, and philanthropy, he serves as a trustee of Montefiore Health System and is an advisor of the Universal Bond Fund and president of Gutfreund & Company. He also served as vice chairman of the New York Stock Exchange and was the chief executive officer of Salomon Brothers. The UJA-Federation of New York has honored him for his charitable activities and contributions. Mr. Gutfreund will always remain a special part of Aperture’s community of loyal friends and supporters.

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming. Click here to learn more about how to affirm your place in the Aperture community.

The post A Celebration for John H. Gutfreund appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 16, 2016

Catherine Opie’s American Souvenirs

From the rush of Niagara Falls to Elizabeth Taylor’s bedroom, a chronicler of American life presents two psychologically striking exhibitions.

By Anne Doran

Catherine Opie, Mary, 2012 © Catherine Opie and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

For the last thirty years, Ohio-born, Los Angeles-based photographer Catherine Opie has been making formally assured and psychologically astute images of America’s landscape and people. Her subjects have ranged from the 1980s lesbian BDSM scene in San Francisco (of which she was once a part), surfers in Malibu, and high-school footballers in small towns across the U.S. to Los Angeles freeway overpasses, Minnesotan ice fishing houses, and downtown St. Louis at dawn. The notion of community with its attendant questions of identity and inclusion is a persistent theme in her work.

For her solo debut at New York’s Lehmann Maupin gallery, Opie presents two concurrent shows. Portraits and Landscapes at the gallery’s Chelsea space combines allegorical photographs of Opie’s friends and people she admires with oversized, out-of-focus images of mountains and waterfalls shot in national parks. At Lehmann Maupin’s Lower East Side outpost, 700 Nimes Road, titled after the address of Elizabeth Taylor’s former home in Bel Air, is a portrait of the actress through pictures of her house and her possessions. (Iterations of both exhibitions are currently on view in Los Angeles at the Hammer Museum and MOCA Pacific Design Center respectively.)

Catherine Opie, Untitled #9, 2013 © Catherine Opie and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

The portraits in Portraits and Landscapes, largely of people from the overlapping worlds of fine art, fashion, performance, and writing, consciously evoke Old Master paintings in style. Each subject poses against a black background, their strongly lit features swimming up out of darkness. Julie Tolentino and Stosh Fila (a.k.a. Pigpen) enact an S&M performance, Pigpen suturing Tolentino’s mouth closed with needles and red silk ribbon, while Kate and Laura Mulleavy, of the fashion house Rodarte, present a tableau in which one, in a man’s suit, works on an embroidery of a blood stain, as the other, dressed in white ruffles, looks on.

Viewed in conjunction with these former works, more straightforward portraits—of author and critic Hilton Als debonair in seersucker, artist Chuck Close flamboyant in a wildly patterned silk shirt, and endurance swimmer Diana Nyad muscular in nothing at all—cannily suggest that we are all, to some degree, and particularly in the age of personal branding and the Internet, performers. The blurred postcard vistas accompanying the portraits might also be seen as landscapes performing abstracted versions of themselves.

Catherine Opie, Hilton, 2013 © Catherine Opie and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

But in spite of their undeniable beauty, these works, in their too-heavy black frames, are underwhelming. The portraits’ lack of psychological complexity in favor of markers of profession or class—Nyad’s tan lines; tattoo-parlor owner Indexa’s body art—is mirrored in their painting-like flatness. Likewise, the landscapes, reduced to muddles of surface color, are revealing of nothing. In these works, at least, Opie elects to refute photography’s rather closer relationship to sculpture, particularly its ability to record, rather than render the illusion of, real space.

Catherine Opie, Bedside Table from the 700 Nimes Road Portfolio, 2010–11 © Catherine Opie and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

More satisfying is 700 Nimes Road. While engaged in documenting Elizabeth Taylor’s house, Opie never photographed or even encountered Taylor, who died three months into project. Thereafter the series took on a new dimension as Opie recorded the dismantling of Taylor’s home and the readying of her belongings for sale. While this series, too, focuses on performativity—in this case Taylor’s carefully maintained, ultra-feminine persona—it presents dichotomies at every level: between public and private, formality and hominess, perception and reality. There is humor here, too—a close-up of swagged pink curtains suggests the star’s famously ample cleavage—and acknowledgement of a life lived almost entirely in the public eye, summed up by the numerous “intimate” snaps of Taylor and Richard Burton taken by professional photographers.

Catherine Opie, Krupp Diamond from the 700 Nimes Road Portfolio, 2010–11 © Catherine Opie and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Equally important, perhaps, are the spatial qualities of the pictures. Billed as Opie’s homage to William Eggleston’s photographs of Graceland, they display, if not Eggleston’s extraordinary sense of color and composition, a similar attentiveness to the relationship between objects in space. In images of hatboxes stacked on a lavender shag rug, gowns coffined in boxes with see-through lids, and those legendary jewels sorted into Lucite containers—all in preparation for auction—Opie shows her true skills as a photographer.

Anne Doran is a visual artist and writer living in New York.

Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road is on view through February 20, 2016 at Lehmann Maupin, Lower East Side. Catherine Opie: Portraits and Landscapes is on view through March 5, 2016 at Lehmann Maupin, Chelsea.

The post Catherine Opie’s American Souvenirs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers