Aperture's Blog, page 146

January 13, 2016

The Past and Other Countries: Chris Killip in Conversation with Michael Almereyda

On the occasion of his new exhibition In Flagrante Two, opening on January 28th at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, Aperture magazine revisits a classic interview with Chris Killip.

Housing Estate on May 5th, North Shields, Tyneside, 1981

Chris Killip’s photographs—black and white, crisply detailed, at once lush and stark—tend to center on working-class people, hard-pressed citizens on the job and at rest. We see them collecting sea coal, toiling in a tire factory, or withdrawn into attitudes of wariness, disenchantment, exhaustion. The weight of the world is upon them, more often than not, and this pressure, bearing down on vividly particular faces, bodies, and landscapes, can be taken to be Killip’s abiding subject. But the pictures convey considerably more than a bleak historical chronicle or sociological report. Killip imbues his subjects and scenes with a sense of urgency, mystery, and radiance. In his greatest work, he seems to deliver more than a photograph can be expected to communicate or contain: hard evidence of the human soul, flickering like embers in a heap of ashes.

The following interview was excerpted from a conversation conducted in Killip’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, an easy stroll from Harvard University, where the photographer has taught since 1991. —Michael Almereyda

Boat Repair, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983

Michael Almereyda: When you were approached to mount a retrospective of your work, what flashed into your head?

Chris Killip: Pleasure at the thought. Nobody had ever asked me to do this before. I am fond of and familiar with Ute Eskildsen from the Folkwang Museum, and it was her suggestion. She is a person that I respect greatly. I couldn’t do it with many other people; I don’t trust other people in the way that I trust her.

MA: I know that your original selection of images was very spare, and she helped fill it out.

CK: Well, it was a process. I’d never gone back to my archive and looked at what I’d done, and Ute made me rethink. My book In Flagrante was published in 1988, and every curator of every exhibition that I’ve been in since has referred back to that book. Ute was the first to say: “What didn’t you publish? What else is there?” It was a great pleasure, but also a great task, which took more than two years, to go through the archive. I also digitized everything while I was doing this, thought about it, printed pictures in different ways.

We included many pictures that I had not considered in years, that I hadn’t published. I thought at the time maybe an image was too nihilistic, or too emphatically strong, or that I might have offended the people in the photograph. There were all sorts of complex reasons why things were never published.

Moira Hand Picking, Sea Coal Beach, Lynemouth, Northumberland, 1982

MA: Why don’t we take a specific case?

CK: There is an image from 1977 called Celebrating The Queen’s Silver Jubilee: I like the picture very much. But I can remember processing and printing it, looking at the contact and thinking: “Oh, my God, I can’t show this.” There’s a very old lady who has been made up for the occasion by her friends: they’ve powdered her face but they’ve been rather overzealous, and the flash has hit her overpowdered face, and, as my cousin would say, “She looks like they dug her up.” I remember thinking at the time: I can’t show anybody this image, it’s just too strange. Now I don’t think that. The picture is such a supercharged Martin Parr-ish image, with the Union Jack in the background and people smiling, and the words The Queen’s Silver Jubilee right there.

Celebrating the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, North Shields, Tyneside, 1977

MA: Your work often has a political undercurrent—if not an explicit acknowledgment of the political situation.

CK: Well, it would, wouldn’t it? I mean, I was living in the industrial community of Newcastle, starting in the mid-1970s. I remember the editor of the Saturday magazine of the Sunday Telegraph asking me to photograph the men from the miners’ strike. I didn’t want to do the story for them because it is such a right-wing newspaper. He asked me which side was I on? I was quite shocked by the question. It had never occurred to me that I could be on anything other than the side I was on!

MA: But including political elements in your work is not about picking sides; it’s about openly saying that your work, your worldview, is conditioned by historical forces.

CK: It was natural. I had no wish to deny it. I was also influenced by John Berger’s TV program Ways of Seeing. I was so excited by that. I was just trying to understand then that no matter what you did, you inevitably had a political position. How declared it was was up to you, but it was going to be inherent in the work, and it was something you should think about as a maker. I never worried about my position in the art world. I thought time and history would ultimately judge me, that my job was to get on with it, to make the work and to make it wholeheartedly from what had informed me.

MA: Was there another photographer who pointed in that direction?

CK: Maybe the least obvious—and the most obvious—would be Walker Evans. It was Evans’s coolness, about surviving McCarthyism, and all the things that Evans survived; and still you knew he had a distinct political position: it was in the work. Evans gave me great heart about that. He had navigated much more difficult circumstances than I had. In America, he had to live through a much more charged political situation than the liberalism of England. In America, it’s much more of a minefield for people who are not of the Right.

MA: I never thought of him having to negotiate that. He seemed so entrenched when he was working at Fortune magazine. It’s interesting to think that he was actually in a perilous situation.

CK: Well, the man who made The Crime of Cuba [1934] had to be very careful. Evans never spoke about his politics, because McCarthy was right behind him—and all the evidence against him was there.

I was also keen on Paul Strand, but I moved from Strand to Evans— attracted by Evans’s greater sophistication, not as an image-maker but as a thinker. Strand was a good image-maker, but Evans was a much more interesting man. It’s very ironic that Strand would make something like his Mexican Portfolio [published 1940], which seems patronizing as it’s so much about the beauty of poverty.

MA: How do you see your political awareness coming through in specific images?

CK: One picture is of a burned-out block of flats in Newcastle. Some people have got their clothes drying on the balcony, and somebody else has got flowers in their window. I think it’s so strange, this optimism. This was a specific moment—1976— in Newcastle history, when some people in public housing were burning themselves out of their homes in order to get rehoused. My interest was in the people who didn’t. But at that time, my pictures were known to Newcastle City Council, whose leader at a council meeting stated (it’s in the minutes of the meeting) that my work was never to be exhibited at any council-controlled museum or gallery in Newcastle, because I was showing the “wrong” image of Newcastle.

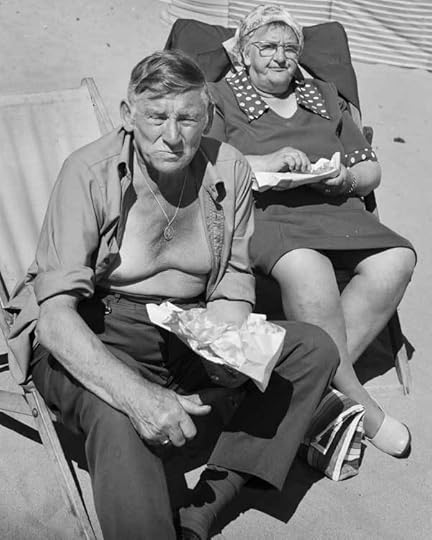

Couple Eating Fish and Chips, Whitley Bay, Tyneside, 1976

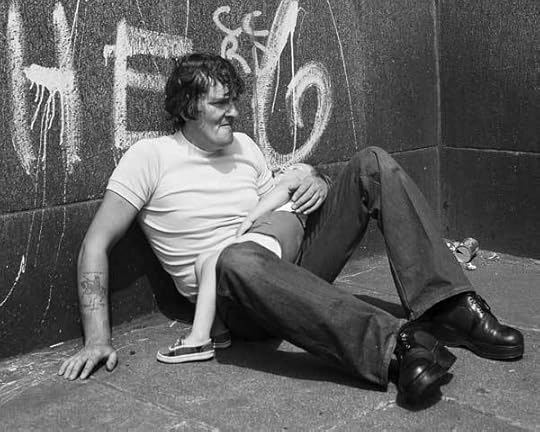

Man and Child at Sunday Market, Newcastle, 1975

MA: You were close with a lot of the people in the pictures you took. That’s been an important ingredient in what you do.

CK: Yes. I remember speaking with Josef Koudelka in 1975 about why I should stay in Newcastle. Josef said that you could bring in six Magnum photographers, and they could stay and photograph for six weeks—and he felt that inevitably their photographs would have a sort of similarity. As good as they were, their photographs wouldn’t get beyond a certain point. But if you stayed for two years, your pictures would be different, and if you stayed for three years they would be different again. You could get under the skin of a place and do something different, because you were then photographing from the inside. I understood what he was talking about. I stayed in Newcastle for fifteen years. I mean, to get the access to photograph the sea-coal workers took eight years. You do get embroiled in a place.

MA: Let’s talk about some of the other images that you retrieved.

CK: There is a picture of a man who reminds me so much of my father and my father’s friends. I look at him, and I recognize him as a working-class man with a trade. How can I know this? I know it instinctively. Something about his attitude and his look and his unabashed stare: he is looking directly at me and questioning me. My father has also served an apprenticeship in his trade as a fitter before he had a pub. Both are men of pride. I didn’t publish this picture when I took it, because I didn’t think this was so important. Now I think differently.

Another picture features graffiti on a wall that says “Bobby Sands, Greedy Irish Pig,” and next to it is a graffiti that says “Smash the IRA” [Housing Estate on May 5th]. I never released this picture while I was living in Newcastle. I felt it was too much about prejudice and intransigence. It’s from May 5, 1981. I can tell you the date, because it’s when Margaret Thatcher announced on the radio program The World at One that the IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands was dead. I was in the darkroom, printing a picture. She said it so triumphantly that I stopped what I was doing, got my 5-by-4, got in my car, and went to the only place I knew that Bobby Sands was memorialized in any way. It was in a public housing project in North Shields, which is fiercely Protestant, and I photographed the graffiti in its context. Kids came up and asked could they be in the picture, and I said Sure. I take a while to get anything together, so they got a bit bored and they’re messing around, but the picture also shows the circumstance of the estate. You can see where people are burning themselves out. Six years after the other pictures I took, where people are burning themselves out of their homes, it’s still going on. You can see somebody’s washing on the line. It’s significant that nothing has changed in the six years.

For me, it was a very sad picture. North Shields is very linked to shipbuilding, and in Britain shipbuilding is dominated by the “Orange Order,” which means that no Catholic can work in shipbuilding. Something about working-class bigotry is so strong for me in this picture. In another way, it’s about how history is lived by working-class people, and how bigotry is passed down, restraining and constraining lives.

Housing and Shipyard, Wallsend, Tyneside, 1975. All images © Chris Killip

MA: The children seem kind of innocent of it.

CK: They could be innocent of it, but they’re not unaffected by it. Your innocence can’t last. Bigotry is powerful.

These pictures belong to a time that’s gone. When I looked at my work on the walls of the museum in Germany, I realized that I was, by default, the chronicler of the “De-Industrial Revolution” in Britain. I knew this, but I didn’t ever know it was blatant until I saw it on the wall in this retrospective, so contextualized. For me, it was overwhelming to think about what had happened to the two countries and how different they now are, Germany full of manufacturing industry, Britain with none. There seems to be no way around it: here the past is another country.

This article was originally published in Aperture issue 208, Fall 2012, available for purchase or in the Aperture Digital Archive.

The post The Past and Other Countries: Chris Killip in Conversation with Michael Almereyda appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 26, 2015

Aperture’s 2015 Year in Review

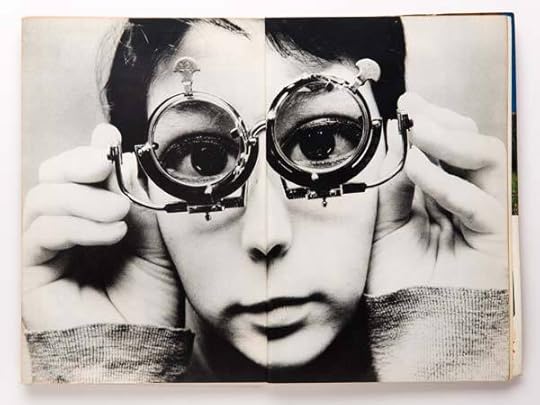

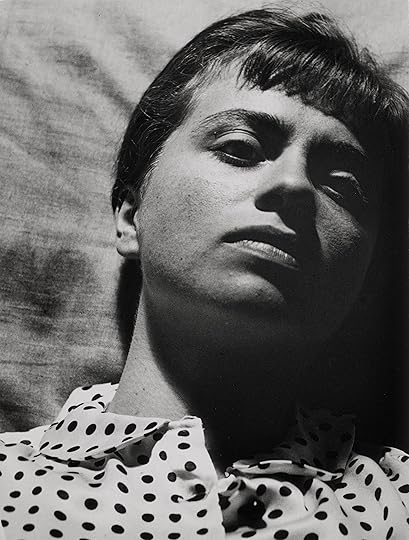

William Klein, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, 1966

Camera Mainichi, April 1965, photograph by Yoshihiro Tatsuki

Ishiuchi Miyako, Frida by Ishiuchi #50, 2012

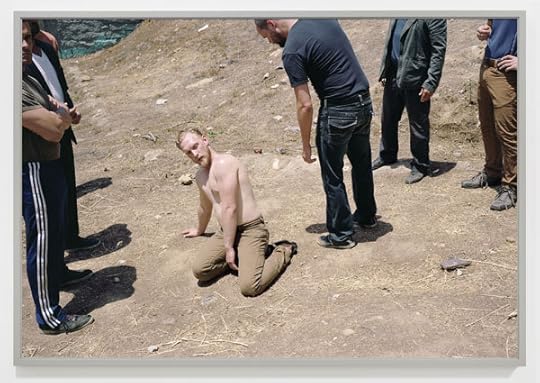

Mike Kelley, Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #32, Plus, a Performa commission, 2009. Photograph by Paula Court and courtesy Performa

Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014

Portrait of Bernd and Hilla Becher, 1985. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery

Pages from Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts (self-published, 2012)

Hal Fischer, Gay Semiotics, 1977

© and courtesy Hal Fischer, and Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

Unknown photographer, Kansas dust Storm, barren earth, 1935. Courtesy Le Bal, Paris

As 2015 enters its twilight, we look back at a selection of features in Aperture magazine, from in-depth conversations with William Klein and Miyako Ishiuchi to articles covering a secret history of Japanese photography to how artists today disrupt Instagram’s conventions, plus much more.

Interview with William Klein: The legend on forgettable fashion, a dream starring Jean-Luc Godard, and his life in photography.

Magazine Work: Ivan Vartanian on finding the Japanese avant-garde amidst the techie and raunchy.

Interview with Ishiuichi Miyako: On the occasion of a retrospective at the Getty Museum, Ishiuichi considers photography as sex, history, and memory.

When is an image more than a document?: Roxana Marcoci and RoseLee Goldberg on photography and performance.

Self-Portraiture in the First-Person Age: Lauren Cornell on the ways artists disrupt Instagram’s conventions.

Hilla Becher (1934-2015): Brian Wallis remembers an iconic figure.

The Lives of Others: Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa on photobooks and troubling representations of Africa.

Gay Semiotics Revisited: Hal Fischer discusses his 1977 examination of the “hanky code.”

A Handful of Dust: David Campany charts the strange career of a surrealist photograph.

On the Nature of Photographs: In this article from Aperture’s new digital archive, Luc Sante and Stephen Shore discuss the essential qualities of photographs.

The post Aperture’s 2015 Year in Review appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 22, 2015

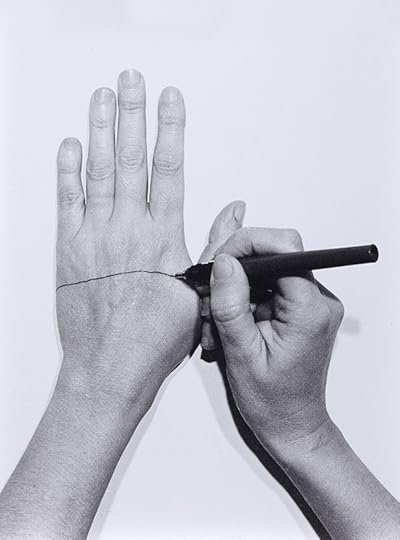

Magazine: Helena Almeida

The octogenarian Portuguese artist Helena Almeida was intent on blurring lines: her playful images might be considered paintings, actions, and performative photographs. Here, Lisbon–based curator and writer Delfim Sardo introduces her work that is now the subject of a major traveling exhibition.

Study for Inner Enrichment. Acrylic on gelatin-silver print, 1977. Courtesy Portugal Telecom Collection.

Inhabited Painting. Acrylic on gelatin-silver print, 1975

Inhabited Painting, 1976

Seduce. Acrylic on gelatin-silver print, 2002

Photograph from the series Inhabited Drawing, 1975

Photograph from the series Inhabited Drawing, 1975

Photograph from the series Inhabited Drawing, 1975

Photograph from the series Inhabited Drawing, 1975

By Delfim Sardo

In Helena Almeida’s 1969 photograph Pink Canvas for Wearing, she is literally wearing a canvas, her arms wrapped in sleeves that seem to sprout from it. This is the first photograph of her career, after working for more than a decade as a painter since graduating from the Faculty of Fine Arts of Lisbon in 1955. In Lisbon’s close-knit art scene of the 1960s, her importance among the Portuguese avant-garde, which included artists Alberto Carneiro, Paula Rego, and Lourdes Castro (most of whom were living abroad, far from the Portuguese dictatorship that wouldn’t end until 1974), was confirmed by her solo show of three-dimensional canvases at Galerie Buchholz in 1967. Despite her increasing renown as a painter, Almeida’s delight at discovering that she could function as a painting through the medium of photography is palpable in this lively image.

Italian artist Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, which Almeida encountered in Paris in 1964, prompted her to start seeing the physical support used for painting—the canvas and the stretcher—as a vehicle for a spatial, conceptual approach to painting that takes the body as its principal point of reference. (Other influences at the time included the French New Wave, which piqued her interest in a conceptual approach to image making, as well as the work of Rebecca Horn, Urs Lüthi, and Jürgen Klauke.) Almeida’s wearable canvases, which are applied to the body in the manner of orthoses, enable the literal embodiment of the painting and the transformation of the artist’s own body into the support and its medium. “I was impressed by the obscure side of the slash, the mystery of what is beyond the canvas,” she said in an interview in 2011. “But unlike Fontana, I wanted to do something that would detach from the painting. Instead of showing the reverse of the canvas, I went out of the canvas.”

A concern with drawing also informs much of Almeida’s work, and she treats the surfaces of drawings or photographs as portals for crossing from the domain of representation into the realm of physical space. In her series of drawings Inhabited Drawing (1975–77), she makes a line materialize (actually a piece of horsehair) and physically snake its way through the space of the image. As the artist described the process in 2006: “I passed to photography through drawing. The drawings with strings [the collages with horsehair] made me use photography. I wanted to grab the string with my own fingers to demonstrate that the line in the paper had become solid.”

While the artist’s initial forays into photography are grouped together as canvas(es) for wearing (1969–70) or, later, Inhabited Painting(s) (1975–76), subsequent pieces would incorporate a number of key forms of expression, including the series titled Studies for Inner Enrichment (1977). In this last body of work, a rich blue paint, somewhere between ultramarine and cobalt, is layered on top of the photograph, sparking little narratives: at times the artist seems to be swallowing or regurgitating the paint, weeping blue tears, slipping it into her pocket like a talisman, or embracing it, incorporating it into herself as she gradually blurs and fades away—almost like a process of transubstantiation.

While the project has eucharistic connotations, here the artist’s body is made visible by the fading of the blue color, highlighting the difference between the surfaces of painting and the flatness of the photographic image. Almeida has used the stringency of the grain in high-contrast photography to rob the pictures of their photographic poetry and render them purely documentary. In the late 1970s Almeida embarked on a vast multimedia series, Feel Me, Hear Me, See Me (1978–80), in which the commands of the title allude to a series of complex and contradictory situations. The Feel Me images are beset with representations of the impossibility of feeling the other, featuring images of closed eyes; the Hear Me images are based on the difficulty of communication, illustrated (among other groups of images) via eight photographs of Almeida and her husband (and work partner), Artur Rosa, facing each other, their mouths connected by what seem to be thin sheets of paper that materialize breath; and the See Me work features an amplified recording of graphite on paper, the sound of a drawing being made. About this sound piece, Almeida wrote in 1979, “I used to think how I would like to hear-see my drawings. So I have recorded some of them… In so doing I had no rhythmical or musical intent but I welcomed in surprise their breathing and rhythm.”

Helena Almeida is now eighty-one, and, although she has been exhibiting internationally since the 1970s, the idiosyncratic character of her work and the profound originality of her approach don’t allow for any easy interpretation. Even in her native Portugal, recognition of her work has been slow: when she had a retrospective exhibition in Lisbon in 2004, it was the first time her work had been on view in a Lisbon museum since 1983. The retrospective exhibition that is now on view at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, in Porto, and that will travel to the Jeu de Paume, in Paris, and to Wiels, in Brussels, in 2016, will be an occasion to see her work as belonging to a generation of artists who examined the relationships between the body, images, and physical space.

Unless otherwise noted, photographs courtesy Galería Helga de Alvear, Madrid.

The post Magazine: Helena Almeida appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 18, 2015

Issue 22 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 22:

● A review of Laura El-Tantawy’s new photobook from from the latest issue of the The PhotoBook Review

● An excerpted essay on Helena Almeida from the “Performance Issue” of Aperture magazine

● A preview of adorable cat photographs from Walter Chandoha: The Cat Photographer

● A conversation between David Campany and Aperture magazine’s managing editor, Brendan Wattenberg

● A review of Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie’s new exhibition, Qui a peur des femmes photographes?

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 22 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 17, 2015

Dust to Dust: A Conversation with David Campany

Dust might be the enemy of photography, but for curator David Campany, the recent exhibition A Handful of Dust was a “dream show.” In this interview, Campany discusses the strange career of a surrealist photograph.

Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, Dust Breeding, 1920. Courtesy Galerie Françoise Paviot © ADAGP, Paris

In 1920, Man Ray visited the Manhattan studio of Marcel Duchamp to photograph a section of what would become Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923), otherwise known as The Large Glass. Strapped for cash, Man Ray had agreed to photograph works of art for the modern art collection Société Anonyme. But first he needed some practice. He set up his camera and focused on the plane of glass, which was perched on sawhorses and covered in dust, opened the shutter for a long exposure, and left the studio with Duchamp for a bite to eat. The word “surreal” is overused and misappropriated these days, but the resulting picture is truly weird. And now it’s the centerpiece of the beguiling exhibition A Handful of Dust, organized by David Campany and on view at Le Bal in Paris through January 17, 2016.

The dust picture is hardly a documentation akin to the copy work for which Man Ray was ostensibly preparing. Within two years, the picture appeared in André Breton’s journal Littérature with a playfully bizarre caption: “Behold the domain of Rrose Sélavy / how arid it is / how fertile it is / how joyous it is / how sad it is! View from an aeroplane by Man Ray – 1921.” (Rrose Sélavy was Duchamp’s feminine alter ego.) With its vertiginous view upon an alien landscape, the dust picture toggles alarmingly between the microcosmic and macrocosmic, defying any settled interpretation or photographic genre. As such, the images collected in A Handful of Dust (the title is borrowed from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land), deftly installed and beautifully reproduced in the accompanying catalogue, are transformed by their association with Man Ray and Duchamp’s visual experiment.

For an exhibition about something filthy, A Handful of Dust glitters with brilliance. At Le Bal, Dust Breeding (one of the photograph’s eventual titles), is juxtaposed with works by Walker Evans and Edward Weston, postcards of American dust storms, and a vitrine of magazines and books charting the strange career of the dust picture in print. The soundscape to a short clip from Alain Resnais’s 1959 film Hiroshima Mon Amour pervades the space and sets an atmospheric tone. In the main gallery downstairs, Campany has selected an array of contemporary artworks that derive their intensity from associations with dust. Driving a through line from Dada to the Gulf War, the dust picture proves to be one of the most mind-bending objects in the history of photography. —Brendan Wattenberg

Photographer unknown, After dust storm woman writes in dust, Kansas City, 1935. Courtesy Le Bal, Paris

Brendan Wattenberg: I imagine you must have long known about the “dust picture,” as you call it, in the context of twentieth century art history, specifically in relation to photography and surrealism. Although it’s appeared in many different ways and in various publications, without A Handful of Dust the picture might have remained something of an oddity. Now it has star billing. When—and how—did the dust picture become the protagonist of this exhibition?

David Campany: Before it became a protagonist of the show, that photograph had been a protagonist in my own understanding of photography, for quite a while. A signpost, or force field in my own mental landscape of photography. Around decade ago I wrote a short essay about it and thought I’d got it out my system. But something nagged away. I felt there was a whole history of the last century that could be extrapolated from that one image. No more than a hunch, really, but when Le Bal in Paris asked me for my “dream show,” I thought … Why not? Let’s see if it will work. It’s a risky idea, but Le Bal is a risk-taking institution. Dust Breeding has been claimed for Dada, Surrealism, Abstraction, Conceptual Art, Land Art, Performance Art, and Postmodern Art. It belongs to all of them and none of them. It’s an unlikely counterpoint to military imaging, forensics, documentary practices, photojournalism, and reportage. In it we see an exploration of time, an embrace of chance, spatial uncertainty, ambiguities of origin and authorship, institutional instability, a blurring of photography, sculpture and performance, a meditation on process, a stand-off between image and text, and a scrambling of distinctions between document and artwork, the formal and the formless, the cosmic and the domestic. Big claims, I know, but they’re worth proposing, at least.

BW: T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land was published in The Criterion in October 1922, the same month as the dust picture was published in Littérature. What is the connection between Eliot and the dust picture?

DC: There’s no literal connection. But connections are less important to me than affinity, suggestion, association, resonances. There was plenty of dust after the First World War. Modernity and “progress” create dust on an unprecedented scale. Tearing down and starting again, coal-fueled factories, war. But modernity and progress also despise dust. It’s the waste product, the extraneous stuff, the marginalia that clogs and clumps and must be got rid of. Meanwhile, in order to track and set up a critical distance from modernity so much of the great art of the last century has, understandably, looked to that extraneous stuff as subject matter and as metaphor. A thickness of dust is a measure of time. It’s also a latent sign of actions or processes. It’s domestic but cosmic, too. To see the world from the point of view of dust will give a different perspective of history and civilization.

Unknown photographer, Kansas dust Storm, barren earth, 1935. Courtesy Le Bal, Paris

BW: As you write in the catalogue, “America’s vast ‘empty’ landscape symbolized boredom of the promise of escape. It’s rarely the space of real anxiety or aesthetic breakdown.” At the same time, you show images of the Dust Bowl, the catastrophic period in the 1930s when dust storms destroyed American farmland, particularly in Oklahoma and Texas. In the dust picture, do you see something particularly foreboding?

DC: Well, dust is a sign both of entropy and foreboding, I think. Everything comes from dust and goes to dust (not wanting to be too Judeo-Christian about it!). What happens in the middle is what counts, but it never runs smoothly. I’m fascinated with images of the dust clouds that tormented the mid-western states in the 1930s. Dust is the enemy of photography—you don’t want it in your camera, or on your negatives—but it is also profoundly photogenic.

Jacques Witt, photograph published in Time, February 25, 1991; Sophie Ristelhueber, À la cause de l’élevage de poussière (Because of Dust Breeding), 1991–2007. Spread from A Handful of Dust, 2015. Courtesy MACK

BW: The images in the catalogue roughly follow a chronological trajectory, but they appear without captions or dates. The structure of the dust picture—its seeming aerial view and the physical property of dust itself—provides a kind of associative road map. Did you have this concept in mind when you began to design the catalogue? Or was this a result of your collaboration with Le Bal and MACK?

DC: Yes, I had that concept in mind, but when you work with a publisher as good as MACK, and with great designers, they understand what you’re trying to do. Together you refine it until you’ve really got something that expresses the original idea. For a while now I’ve been circling around the possibility of the associative sequence of images being a form of “writing”—using images in such a way that they articulate and bounce off each other. In my last twenty or so publications, I’ve been selecting and sequencing the images before even beginning to write. I did this when I wrote the long essay for The Open Road for Aperture, for example. That essay should make a lot of sense simply as a sequence of images, before you’ve even read a word. For the Dust project, I had written a long essay, maybe 30,000 words, but I was quite prepared to junk it as the necessary labor that got me to that particular selection and sequencing of images. In the end we found a lovely format for the book. The text is a separate supplement that sits in the image sequence but can be removed entirely. You can make your way intuitively through the image track, or you can read my historical/theoretical text. I was so pleased to have found a format that worked both ways. I think it’s pretty innovative and a good sign of how I’d like to be thinking about images and writing in the future.

Robert Burley, Demolition of Buildings 64 and 69, Kodak Park, Rochester, New York, 2007. Courtesy the artist and Musée Nicéphore Niepce, France

BW: You’ve included an enormous range of objects spanning nearly a century—vintage prints, books, postcards, vernacular photographs, video clips. No medium is privileged over another. Was this curatorial strategy meant to show the promiscuous nature of photographs—the cross-pollination of images between art, documentary, forensics, and war?

DC: It’s not a curatorial strategy. It’s just how I think about images, and how I think they should be about. If you don’t follow the canon, or the museum histories or the money, you can see the richness of photography for what it is: dispersed and anti-hierarchical. We know that great work, or significant work, can be made in the name of art, as a press photo, as a vernacular postcard, or as a scientific document. And on any given day we might consume all those things. This seems perfectly normal to see, not a strategy at all. In fact, it’s only strategy that will exclude that promiscuity. Museums tried to do that for decades, thinking that was the way to make photography special. Now they realize that its specialness is quite the opposite.

Xavier Ribas, Nomads, 2008. Installation view: A Handful of Dust, Le Bal, Paris, October 16, 2016–January 17, 2016. Photograph: Martin Argyroglo. Courtesy Le Bal, Paris

BW: The exhibition at Le Bal features multiple works by contemporary artists, including Sophie Ristelhueber, Nick Waplington, John Gerrard, and Xavier Ribas. How have these recent projects created a further permutation of the dust picture?

DC: I wanted to put together a project about resonances. But there is one work that was made as a result of influence. When Sophie Ristelhueber photographed the deserts of Kuwait in 1991, in the wake of the retreat of Saddam Hussein’s army, the image she had in mind, as a template or program, was that image of dust on Duchamp’s Large Glass taken in 1920. I find that remarkable. A photograph made in a completely different circumstance, of a completely different subject can become your point of reference. It just shows the strange and barely conscious ways that images can affect us so deeply. But I also take Ristelhueber’s project as an instance of what elsewhere I have called “Late Photography.” In the wake of TV, video, and internet coverage of world events, still photography has been eclipsed. It’s not obsolete, but it is secondary. Events are often left to the moving image, while many photographers prefer to come along afterwards, as a second wave of more circumspect or even allegorical image-makers. I touch on this in this book and the show as being one of the most significant changes in photography in the last generation. And in shifting from the events to their traces or aftermaths, photography has come into new relations to dust.

Brendan Wattenberg is the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

A Handful of Dust is on view at Le Bal, Paris, through January 17, 2016.

The post Dust to Dust: A Conversation with David Campany appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 16, 2015

When Women Get Involved

Two Paris museums put women photographers in the spotlight. But are gender-specific exhibitions relevant today?

By Wilco Versteeg

Margaret Bourke-White, Self-portrait with camera, ca. 1933 © Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

This winter, a dual exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie titled Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 presents a survey meant to highlight the long history of contributions to photography by women practitioners and artists. Throughout this expansive, multi-venue project, the visitor is invited to take a critical approach to the history of photography and to ponder the value of gender-specific exhibitions. In a mechanical visual medium that seems more resistant to distinctly male or female touches than other arts, the diverse selection of photographs here constantly reminds us to consider who was behind the camera and why. By choosing to exhibit a very large sample of lesser-known women photographers, Qui a peur des femmes photographes? aspires to enrich or even rewrite photographic history.

Barbara Morgan, We are three women – We are three million women, 1938 © Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie

The first of the exhibition’s two parts, hosted by Musée de l’Orangerie, covers the years from 1839, marking the French patent on photography, to 1919. The second, at Musée d’Orsay, is bookended by the two world wars. As for this division, the end of World War I, of course, brought about social and political changes, but many stylistic patterns continued from the previous era. The chronological set-up seeks to narrate a story of both stylistic experimentations, exploring the possibilities and limits of photographic processes and social developments by and of women photographers, but sometimes lacks context about the individual careers of those who are not as famous as figures such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Gertrude Käsebier, or Dora Maar. Take Madame Yevonde and her path breaking work in color photography, or the pioneering travel photography by Helen Messinger Murdoch. Monographic exhibitions on these artists would grant their place in the pantheon of photographers.

Christina Broom, Young Suffragettes advertising the Women’s Exhibition, 1909 © Museum of London

But what is distinctly female about the works in this exhibition? For me, as a male viewer, Lee Miller’s early-1930s anti-voyeuristic image, Severed Breast from Radical Surgery in a Place Sitting, an image of an amputated breast on a plate, haunts me more than any other image on view. It made me realize that the title of the exhibition is ill-chosen: it should not have been Who is afraid of female photographers? but What Are Men Afraid to Photograph? Whether this might be explained by the impossibility for men to separate the breast from its maternal or sexual functions is open to discussion: Miller, in any case, shows a relationship to the breast that transcends these categories. In Miller’s transgressive audacity, something decidedly feminine can be found.

Aenne Biermann, Gummibaum, 1927 © Museum Folkwang Essen

From its invention, photography proved to be a more inclusive medium for women, who were not allowed into art schools or academies: discovering the possibilities of the camera by trial and error didn’t necessarily require formal instruction. From those looking at everyday life to the more conceptually adventurous, female photographers quickly covered all imaginable fields. The beautiful photographs of plants by Aenne Biermann, Alma Lavenson, and Tina Modotti come to mind; or taboo images of male nudes by Imogen Cunningham, Anne W. Brigman, and Harriet V.S. Thorne. These images seem to avoid objectification by foregrounding the sensual, even mystical aspects of the naked male body, whose formal beauty is sublimated into something easy to look at, but hard to define. In these pictures, the body is allowed to perform a non-pornographic erotics and to escape a reductive gaze unlike those of female nudes by their counterparts. In another critical position on the body, one segment of the exhibition is dedicated to self-portraiture, where subject and object collide and the photographer can take complete control over her final image. Madame D’Ora’s Selfportrait with Black Cat (1929) is an exquisite example: not only does the work show absolute mastery over material and light, it inscribes itself consciously into art history (references to Manet’s Olympia are on the horizon).

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Marins dansant la valse à bord de l’USS Olympia, 1899 © Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

However, in the realm of photojournalism, the exhibition makes its strongest argument for a gender-specific presentation. Notions of identity are performed in theaters of conflict, and domains formerly restricted by gender are pried open. Christina Broom’s underappreciated work (at least in the marketplace) for both the suffragettes and the British army, and Florence Farmborough’s pictures from the front lines of World War I, show when and how women photographers started to level the playing field. In the next war, photographers such as Gerda Taro, Julia Pirotte, Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, and Joanna Szydlowska found their distinct voices. Taro’s brutal Air Raid Victim in the Morgue, Valence (1937) or Szydlowska’s images taken illegally inside a women’s concentration camp are vivid examples of their tenacity. Olga Vsevolodovna Ignatovitch, unfortunately, is the only example from the Soviet side of the Allied war effort. During “the great patriotic war,” as the conflict was called in the USSR, women chose to fight for their country either by taking up arms or picking up a camera. This subject would provide enough material for its own exhibition.

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Mills Thompson travesti, ca. 1895 © Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Simultaneously on view at the Musée d’Orsay is Splendeurs et misères. Images de la prostitution, 1850–1910, which focuses on women as passive objects of male voyeurism It’s a fascinating coincidence to have two exhibitions dedicated to “the feminine” in art history on view at the same moment. The prostitution show is a spectacle and has been extremely popular with audiences, which grants the more modest exhibition on female photographic practitioners an urgency it perhaps wouldn’t have had otherwise. Together, the exhibitions foreground the logic and task of the contemporary museum in catering to unquestioned tastes for “the feminine” and aim to confront audiences with what was at risk of being forgotten.

Elfriede Stegemeyer, Self-Portrait, 1933 © Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

Qui a peur des femmes photographes takes the role of debunking the male gaze much more seriously than the exhibition on images of prostitution. Even so, it’s not a radical exhibition in a political sense: there is little overt activism in that it does not try to steer the audience towards a reductive interpretation of female photographers and their social suppression by men. The exhibition left me with a hunger for dedicated exhibitions on multiple aspects of the show that were only mentioned in passing. This broadness is a strength, but also points to the fact that the study of women photographers is still in an early phase. It’s impossible to imagine an exhibition dedicated to “male photographers”; in fact, it would rightly be considered absurd. Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 is a necessary exhibition that points to important women practitioners to whom we have been partly blind. One can only wonder what is still hidden in the archives.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD student of photographic representations of virtual warfare at Université Paris Diderot.

Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 is on view at Musée de l’Orangerie and Musée de l’Orsay, Paris, until January 24, 2016.

The post When Women Get Involved appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 15, 2015

For a New World to Come

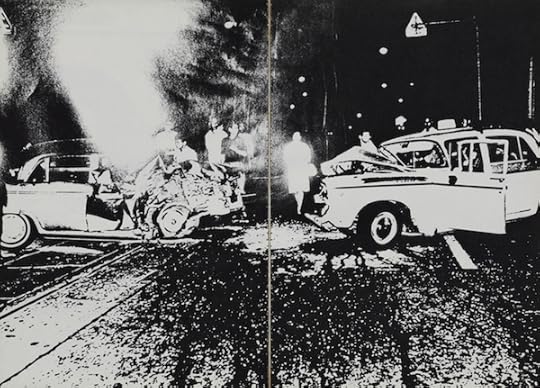

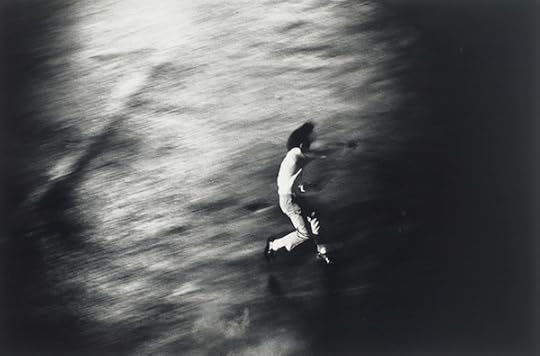

Daido Moriyama, from Asahi Camera, 1969 © Daido Moriyama and courtesy Tokyo Polytechnic University, Shadai Gallery and Taka Ishii Gallery

Aficionados of photography from Japan will find surprises—and their assumptions challenged—among roughly 250 works included in the fascinating exhibition For A New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Photography, 1968-1979. The exhibition explores avant-garde artistic output during a decade in Japan marked by widespread student protests, economic flux, and transformative urban growth. While the show includes legends like the Provoke-era master Daido Moriyama, the famously provocative Nobuyoshi Araki, and Shomei Tomatsu, who cast a critical eye on the American occupation of Okinawa, many of the twenty-nine artists featured in this show have never been exhibited before in the United States. By delving into the nexus of photography and conceptual art, the exhibition presents a trove of unseen works in the forms of gelatin-silver prints, graphically seductive books and magazines, homespun Xerox projects, videos, and other pieces that bridge photography, painting, and sculpture. The exhibition, which is accompanied by a catalog full of scholarly essays, is revelatory and opens up a rich history for American audiences.

Aperture magazine editor, Michael Famighetti, recently spoke with curator Yasufumi Nakamori about his show, which opened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, before traveling to New York, where it was split between Japan Society and the Grey Art Gallery, New York University. Nakamori also contributed a related essay to Aperture magazine’s “Tokyo” issue.

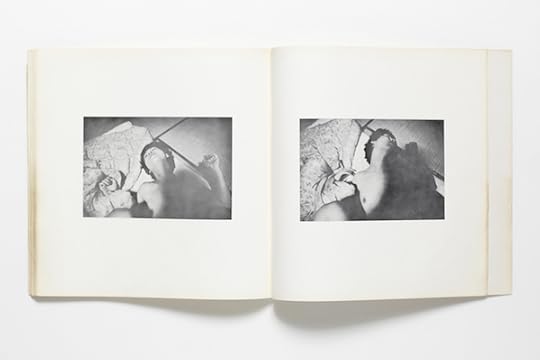

Araki Nobuyoshi, Sentimental Journey, 1971 © Nobuyoshi Araki

Michael Famighetti: This exhibition is, in part, a response to curator John Szarkowski’s 1974 MoMA exhibition New Japanese Photography, which introduced an American audience to post-War figures, such as Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama. For a New World to Come includes some of these same names but introduces many other practitioners. What was the starting point for your research into experimental work of this period?

Yasufumi Nakamori: The exhibition research continued for two years. My research partner, Yuri Mitsuda, a Tokyo-based art critic, and I first looked at several dozen photographers and artists (painters and sculptors) who were making experimental work with the camera in the 1970s, and at several exhibitions that took place mostly in Japan, as well as in the U.S. and Europe.

We meant “experimental” to mean a wide range of experiments, both personal and collective, including emerging conceptual and post-minimal practices. This was a decade when Japanese society had undergone radical transformations in politics, economy, and cultural production. We were primarily interested in how artists and photographers, freed in the late 1960s from the rigorous orthodoxy imposed by the academy, responded artistically to this cultural shift. Artists crossed the boundaries of fine arts and photography; the two mediums had their own distinct histories until then. We were interested in finding out what had not been shown (as an exhibition) or discussed (within scholarship). In our exhibition and publication, we have shown successfully that, contrary to the general perception, in the 1970s, numerous Japanese artists and photographers were engaged in experimental practices with the camera. They were aware of international trends and laid a foundation for the field of contemporary art, where photography plays a critical role.

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1968–1973, printed 2014 © Takuma Nakahira

MF: The exhibition’s title is a play on Takuma Nakahira’s book For a Language to Come (1970). How does Nakahira serve as a touchstone for the show?

YN: His publication, filled with his Provoke-era photographs of the city, characterized as are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), is certainly the beginning of the exhibition. However, I was more interested in his shift that took place in the early 1970s, from his signature black-and-white photographs to his large-scale installation (twenty feet across) of forty-eight color photographs, known as Overflow (1974). Earlier, Nakahira insisted that written language was no longer sufficient to portray the complexities and nuances of the time, and proposed for photography to fill the older medium’s deficiency, as the new Japanese culture known as eizo gengo (image language) surfaced.

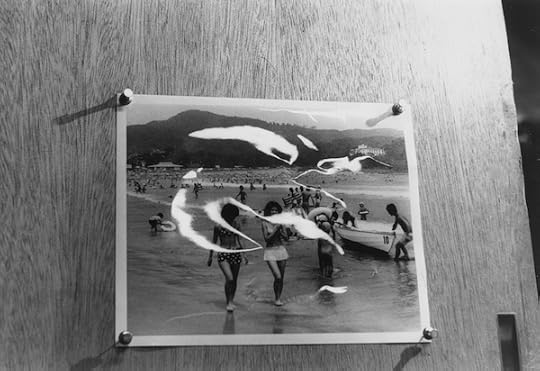

Jiro Takamatsu, Photograph of a Photograph (No. D-2401), 1972 © The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu and courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates

With his anthology of essays titled “Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?” (1973), Nakahira defied his then-recent past and advocated for color photography to accurately reflect Japanese society in the 1970s. In the installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, I traced this shift in Nakahira’s photographic practice. Additionally, Nakahira was important for the exhibition because he connected the worlds of photography and contemporary art in 1970s Japan. For example, his photograph of a desolate part of the Tokyo Bay was used on the cover of the catalogue of the 10th Tokyo Biennale, titled Between Man and Matter (1970), an important exhibition that introduced conceptualism to Japanese audiences. In my show, I featured artists Jiro Takamatsu, Koji Enokura, Hitoshi Nomura, and Tatsuo Kawaguchi, who were shown in Between Man and Matter.

Nobuo Yamanaka, Manhattan in Pinhole 1, 1980 © Nobuo Yamanaka

MF: Such names will likely be new to visitors of the show in the States, but how well known are these artists in Japan?

YN: Artists such as Kazuyo Kinoshita, Masafumi Maita, Nobuo Yamanaka, and photographers like Kiyoshi Suzuki, and Kenshichi Heshiki are known among specific (and relatively small) audiences in Japan.

Yuri Mitsuda and I both grew up in the 1970s in the Osaka/Kobe area and we were keen on moving away from Tokyo-centric art and photography. This is what has been shown in a number of U.S. exhibitions of post-War Japanese art, such as New Japanese Photography (MoMA, 1974), Japan: A Self-Portrait (ICP, 1979), and Tokyo: A New Avant-Garde, 1955–1970 (MoMA, 2013). However, exhibitions like Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky (Guggenheim Soho, 1994), Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s to 1980s (QMA, 1999), and Gutai: A Splendid Playground (Guggenheim, 2013) certainly indicated a direction for an interdisciplinary methodology for my current exhibition.

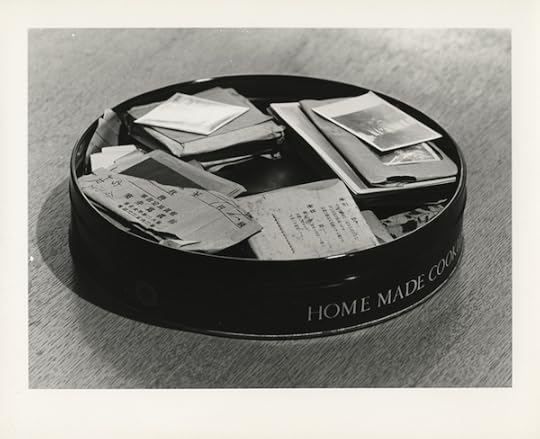

Kiyoji Otsuji, Past of One Tin Can, from the series Otsuji Experimental Laboratory, 1977 © Seiko Otsuji

MF: The Provoke figures were influenced by French thought, by authors such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, to name one example. A poet was among the founders of Provoke. Nakahira saw photography as exceeding written language. What was the relationship between the literary and photography worlds in Tokyo at this time?

YN: An excellent question. Nakahira studied Spanish, French philosophy, and literature. Takahiko Okada, one of the Provoke collective members (the only non-photographer member), edited, along with the Surrealist and photographer Kiyoji Otsuji, the December 1968 issue of Bijutsu techo (Artists’ Notebook) that was entirely devoted to the history of photography. Another Provoke collective member Koji Taki, who was familiar with, among many other things, the literature by Walter Benjamin, soon began writing criticism on art, photography, culture, and architecture. Provoke was certainly marketed in both photography and literary circles. Nakahira can be situated in a group of writers and artists who advocated for the emerging field of eizo gengo (image language) in the 1970s. The terminology is arguably derived from the French film critic André Bazin’s book What Is Cinema?, which was released in Japanese translation in 1970. Nakahira’s familiarity with the literature and films by French artists, such as Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) were relevant to his photographic projects, like his 1971 Circulation: Date, Place, and Events, created at the Paris Biennale. Nakahira’s color photo installation Overflow (1974) can be interpreted his dreamlike non-narrative of a city wanderer, a psycho-geographical photographic experiment, perhaps informed by Guy Debord.

Shomei Tomatsu, Protest 1, from the series Oh! Shinjuku, 1969, printed 1980 © Shomei Tomatsu and INTERFACE

MF: A tension between Tomatsu and his vision of photography, which was experimental in its own right, and the Provoke photographers, plays out in the exhibition. That said, both Tomatsu and the Provoke figures were pushing the language of photography. How much of this was an aesthetic battle vs. a regional battle (Osaka vs. Tokyo)? Or a question of inclusivity vs. exclusivity?

YN: Tomatsu was slightly older than both the Provoke photographers and those associated with konpora (a shorthand in Japanese for “contemporary photography”), who were known for their deskilled snapshots of the everyday. Tomatsu thought both of these camps were nonsense, though he maintained a certain relationship with the Provoke photographers. Tomatsu himself also took some out-of-focus photographs (a stylistic hallmark of the Provoke group), like those he shot in Okinawa. Self-taught and self-established, Tomatsu was never interested in being a passive member of any collective, after his participation in the photography collective VIVO, in the 1960s. He started a publishing house (Shaken), a magazine (Ken), and an alternative photography school (Photography Workshop). His vision for photography—and Japan—went beyond the Tokyo-centric, New Left elite discourse. He traveled to Okinawa before the island was repatriated to Japan in 1972. In the early ’70s, he began looking at even Southeast Asia. His dialogue extended outside the narrow field of photography and the city of Tokyo.

Shigeo Gocho, from the series Familiar Street Scenes, 1978–1980 © Hiroichi Gocho

MF: You mentioned konpora, the term used to describe the snapshot aesthetic seen in the work of photographers such as Shigeo Gocho. Your exhibition catalog text points to Nathan Lyons’s 1966 George Eastman House exhibition Contemporary Photographers: Toward a Social Landscape as a influence on this style of photography in Japan. Presumably, the catalog for that show circulated widely in photo-circles in Japan at that time?

YN: Yes. My understanding is that the American exhibition catalog and Otsuji’s writing about the exhibition in a 1968 Mainichi Camera issue circulated in Japan and at major photography schools, like the Tokyo College of Photography.

MF: The exhibition highlights the role of the photographer-run, independent gallery and photographer-run magazines. Did photographers need to create, in effect, their own institutions?

YN: I believe they did. Given that there was no commercial market, photographers needed to create their own opportunities to show (and sell) beyond commercial photography magazines, like Mainichi Camera and Asahi Camera. The short-lived Workshop Photo School (established by Tomatsu but which also included Araki, Noriaki Yokosuka, Masahisa Fukase, Moriyama, and Eikoh Hosoe) was extraordinary. In addition to teaching photography, these teachers published quarterly journals and attempted to create a photography market. In 1976, for example, they set up an exhibition where they and their colleagues sold prints. From the Workshop Photo School, numerous independent photography spaces, such as Image Shop CAMP, Prism, and Put emerged.

MF: This is a big, ambitious show, featuring twenty-nine artists. What challenges did you encounter?

YN: As I mentioned, it took me and Yuri Mitsuda, my research partner, approximately two years to do the research. I met all of the artists or representatives (if the artists were deceased or ill), except for two. As we finalized the selection of works, it was important to figure out what the decade of the 1970s and the idea of “experimental” meant to these artists. A major challenge was that I needed to create the ambitious exhibition and publication (of eighteen essays by thirteen authors) within a reasonable budget, which was not huge.

MF: The idea of what’s “experimental” means many things in this show.

YN: Most of the artists and photographers in the exhibition sought out to find new ways of seeing with the camera, freed from traditional ways of seeing taught at the academy. Such experiments could range from conceptual, to intermedia/interdisciplinary, and to performative. Introduction of seriality to express the element of time was also seen often. Each experiment observed in the show is personal, yet international. International contemporaneity observed through various experimental practices is the core of the exhibition.

Kazuyo Kinoshita, 79-38-A, 1979 © Kazuyo Kinoshita

MF: Were any of the artists new discoveries for you? What did you learn as a scholar/ curator that was unexpected?

YN: Personally the artists Nobuo Yamanaka and Kazuyo Kinoshita were new discoveries to me. Both Mitsuda Yuri and I felt that we needed to bring up in the exhibition most experimental aspects of each artist/photographer’s practice. The sculpture/photography installation by Keiji Uematsu, who installed his site-specific sculpture Cutting both in Houston and New York, brought an experiment to me as a curator of photography. Reconstructing the late Yamanaka’s Fixed River (1972) based on research that we conducted was both a challenge and a learning experience.

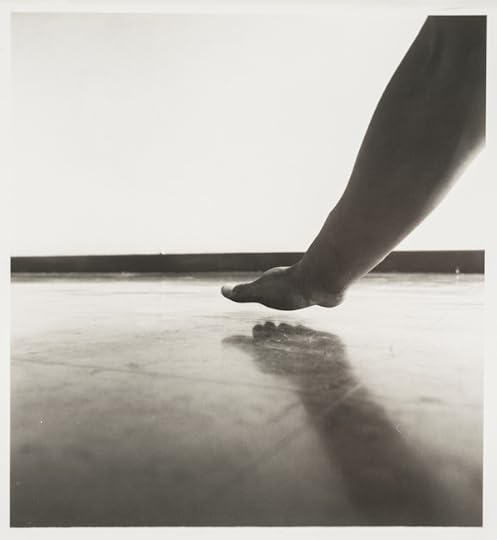

Koji Enokura, P.W. No. 51, Symptom—Floor, Hand, 1974 © Michiyo Enokura and Photo: Paul Hester, Hester + Hardaway Photography

MF: The exhibition is strictly bracketed by the years 1968–1979. Did this spirit of experimentation cease in the 1980s, as Japan surged economically?

YN: I tend to think that the experimental spirit waned as many of the photographers and artists began to have access to capital, art commissions, and other opportunities to sell and do more commercial work. The dominance of color photography in the 1980s also changed the conceptual/experimental practice found previously.

Toshio Matsumoto, For the Damaged Right Eye, 1968. Triple 16mm film (transferred to DVD), color, 12 min. 9 sec. Matsumoto Toshio © Toshio Matsumoto, Photo: PJMIA

MF: Now that you’ve unpacked this incredibly rich decade of photography, where will you turn your attention next as a curator? Do you see another lacuna in the narrative of photography from Japan that should be brought to an international audience?

YN: A serious investigation of the aforementioned Photo School Workshop as an artistic movement, in relation to the collapse of modern photography observed in the mid-1970s, should be done.

For A New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Photography, 1968-1979 is on view at Japan Society in New York through January 10, 2016.

The post For a New World to Come appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 11, 2015

Ocean of Images at MoMA

The Museum of Modern Art’s New Photography exhibition considers contemporary image-making in an increasingly globalized yet formless world.

By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

DIS, Positive Ambiguity (beard, lectern, teleprompter, wind machine, confidence), 2015. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art’s revamped, and now biannual New Photography exhibition is called Ocean of Images, which the curators Quentin Bajac, Roxana Marcoci, and Lucy Gallun explain is a title that clarifies the exhibition’s attempt to probe “the effects of an image-based post-Internet reality.” In this context, the Internet is to be understood as “a vortex of images, a site of piracy, and a system of networks,” and the show brings together nineteen international artists grouped around this central theme. Ocean of Images explores the extent to which their photographic practice reflects these rapidly changing techno-social norms.

The show opens with three works by the American collective DIS, known for their online publication DIS magazine. The first, Positive Ambiguity (beard, lectern, teleprompter, wind machine, confidence) (2015), is a sensuous video performance by pop artist and drag queen Conchita Wurst, who appears between two clear glass panes of a teleprompter, in the faux setting of an awards ceremony. The title signals the virtue of Wurst’s increasing popularity, and hints at the adaptability of people to new images and identities as something linked to the changing role of the screen.

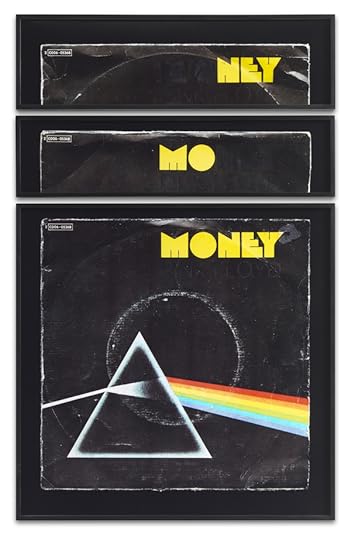

Natalie Czech, A Poem by Repetition by Aram Saroyan, 2013. Courtesy Capitain Petzel, Berlin and Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf. Art © the artist

Themes of performance and fame are echoed in German artist Natalie Czech’s works, as in A Poem by Repetition by Aram Saroyan (2013), which folds together Saroyan’s sparse three-line poem with cropped and appropriated sections of the record cover for Pink Floyd’s Money from 1973. Czech’s works reflect the current retromania in popular (and artistic) culture, and methodically point to its strong links to a changing contemporary sense of identity. Czech’s taut formal control is echoed in Israeli artist Ilit Azoulay’s Shifting Degrees of Certainty (2014), which arrays a collection of eighty-four fragmented inkjet prints of curtains, doorways, statues, pre-historic animals, and a stuffed giraffe into the vague shape of a proto-gothic church façade. This piece reflects the associative bounties of image archives, by intimating disjunctive links between digital images floating in physical space.

Ilit Azoulay, Shifting Degrees of Certainty (detail), 2014. Courtesy the artist, Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York, and Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv © the artist

David Hartt’s Belvedere cycle (2013), Anouk Kruithof’s Subconscious Travelling (2013), and Indrė Šerpytytė’s 1944–1991, a series of re-photographed wood-carved models of Soviet-era torture houses (2009–15) also engage ideas of the archive. Šerpytytė’s row of bleak monochromatic prints is simultaneously ghostly and typological. Hartt’s photographs of rooms filled with stacks of photocopied documents, made in a free-market think-tank (The Mackinac Center for Public Policy), display the conjunction of bureaucratic order (a neutral, gray cubicle specifically for fiscal policy) and the callousness of lobbying (binders on “greed” and “freeloaders” recall Mitt Romney’s infamous remark on his “binders full of women”). Hartt’s pictures suggest a strange mixture of frat-boy humor and rigid bureaucracy in the functioning of American political power.

David Hartt, Belvedere II: Joseph P. Overton Memorial Library at The Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Midland, Michigan, 2013. Courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York © the artist

Other pieces invoke older modes of photographic imagery that continue to maintain their purchase on the present. Lele Saveri’s The Newstand (2013–14) transposes his ten-month occupation of a functioning newsstand, selling independent zines, artist books and records, from a subway stop in Brooklyn to the Steichen galleries of the MoMA. Its presence here underscores the ascendant interest in hand-made and limited edition printed matter within the circles of high art. The Newstand installation is open to customers during select hours, outside of which patrons are requested “not to touch the materials unattended.” This hauteur and reserve is a startling contrast to the openness of the original newsstand, and with its irreverent fare. That contrast is heightened by The Newstand’s proximity to Found Not Taken, Luanda (2013) by Edson Chagas, which features five pallets of free stacks of lithograph posters showing photographs of urban disjecta arranged into still lifes in interstitial parts of Luanda.

Lele Saveri, The Newsstand, 2013–14. Produced in collaboration with Alldayeveryday © and courtesy the artist

Nearby is David Horvitz’s Mood Disorder (2015). The work tracks the spread of Horvitz’s self-portrait, head in hands by a roiling sea, after he uploaded it to Wikimedia and it was adopted as a stock image to symbolize troubled mental health. This piece, ostensibly about motion and replication, instead becomes stilted in its installation as printed spreads hung on a gallery wall. Along with Positive Ambiguity, and Lucas Blalock’s overtly distorted and digitised studio pictures, this work appears in conceptual terms to be most germane to the exhibition’s stated premise of addressing photography’s relationship to “post-Internet reality.”

This raises the question of whether, and how soon, one might expect photographic art, or the slow speed of major museums’ exhibition schedules, to reflect a technological revolution that has only recently begun to transform every avenue of western public and private life. We might think of Warhol and Rauschenberg’s work from the 1960s as exemplary of art informed by the late adolescence of the television age, as in the case of Double Elvis (1963) or Retroactive I (1963), but public access to Facebook is not even a decade old. Web-driven life is still in its infancy.

Installation view of Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 7, 2015–March 20, 2016 © and courtesy The Museum of Modern Art

While its survey of photographic modes is commendably broad in geographic variety, Ocean of Images is a stately affair, and it generates little catalytic energy between its works at a visceral level. It lacks the dizzying hybridity of the “vortex” signalled in its own description, and the relative paucity of depicted human beings in the exhibited works evidences the show’s preferential interest in the life of images over life in images. This legitimates the presumption that we have all, in some fundamental sense, migrated to a world enclosed within the screen, suggesting that Ocean of Images is an exhibition that seeks to theorize the world rather than know it, to rework a line from John Szarkowski’s New Documents exhibition in 1967.

One wonders whether some structural change to the slow speed and expense of MoMA’s exhibition schedule isn’t a necessary precondition for responding to the velocity and complexity of life in the digital realm. Perhaps a more provisional and less comprehensive approach might deliver a more concise and emphatic exhibition. The danger of a thematic approach to a biannual survey built around the fact of rapidity may be that the mechanism itself is too slow.

Lucas Blalock, Strawberries (forever fresh), 2014. Courtesy the artist and Ramiken Crucible, New York

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa is a photographer, writer, and editor of The Great Leap Sideways.

Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015 is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through March 20, 2016.

The post Ocean of Images at MoMA appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In and Out of the Studio

The Met has mounted its first-ever exhibition of West African photographs. But is the museum late to the party?

By Brendan Wattenberg

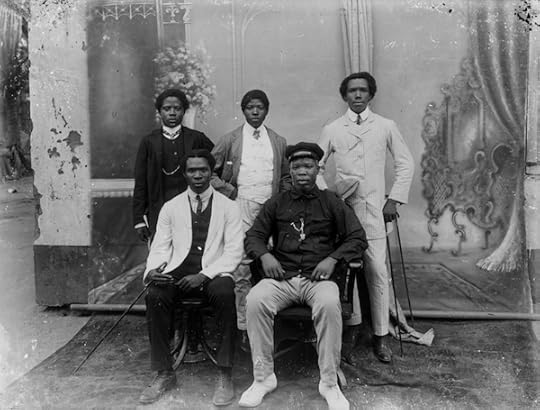

Alex Agbaglo Acolatse, Group portrait, ca. 1900–1920. Inkjet print from glass negative, 2015. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

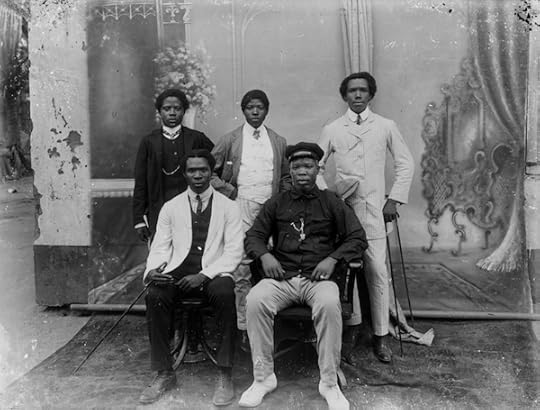

Unidentified photographer, Outdoor group portrait, Senegal, Dakar, ca. 1930s–40s. Gelatin-silver print. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

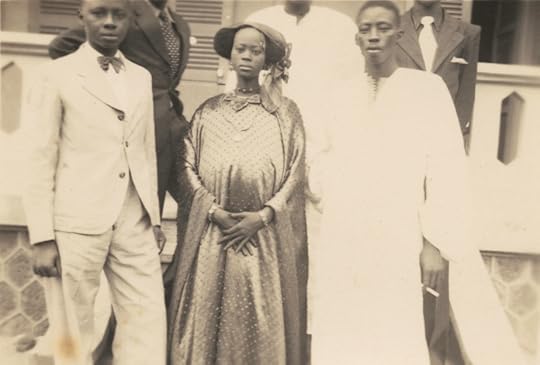

Possibly Jean Benyoumoff, ca. 1900–1910. Postcard reproduction published by Jean Benyoumoff. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

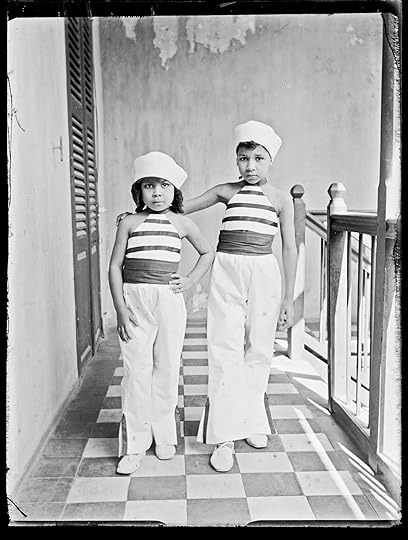

Unknown Artist (Senegal), Two Girls, Indoors, ca. 1915. Gelatin-silver print from glass negative, 2015. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

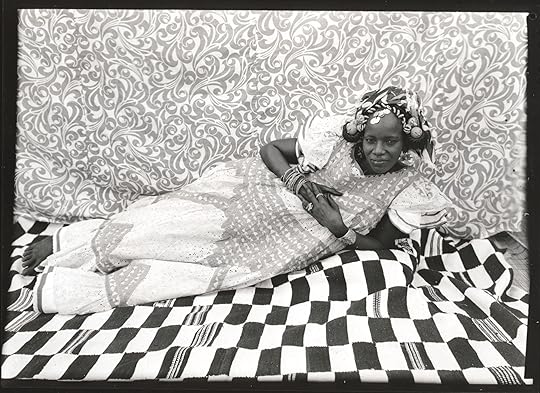

Mama Casset, Two Reclining Women, ca.1950s–60s. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

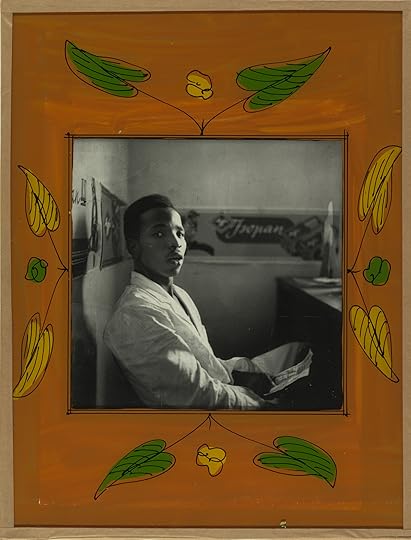

Malick Sidibé, Self-Portrait, 1956. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Seydou Keïta, Reclining Woman, 1950s-1960s. Gelatin-silver print, 1975. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

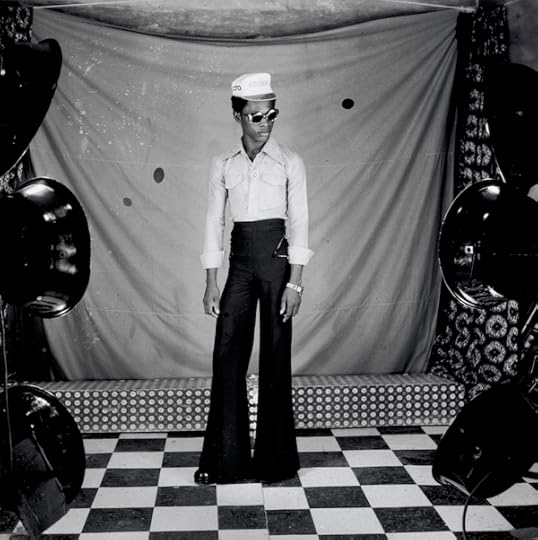

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait, 1976. Gelatin-silver print, 2003 © the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

You didn’t have to be a movie star to be photographed by Mama Casset, but you might have left his studio feeling like one. Casset established a successful studio in Dakar, Senegal in the 1940s, and his portraits were enviably chic. He often posed subjects on a diagonal, energizing the picture with verve and momentum. His close focus removed any worldly references beyond the dark curtains of the backdrop. It’s all the more exciting, then, to discover an image by Casset midway through In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa, an exhibition of nearly eighty photographs currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But one Casset is not enough. Relegated to a back room of the Modern and Contemporary wing, this exhibition, which aspires to cover a century of West African photography, illustrates the challenge of glossing the immense range of West African photographic expression in a space smaller than most Chelsea galleries.

In and Out of the Studio begins with a sequence of late-nineteenth century portraits by the father and son George A. G. and Albert George Lutterodt, as well as by Alex Agbaglo Acolatse, who worked in present-day Ghana and Togo. In these photographs, groups of men in regal dress are pictured in stiff, stately postures against painted backdrops. The full-frame image from an original glass negative (on display alongside a modern gelatin-silver print) shows the fringes of the outdoor setting—the roll of the backdrop, the flaking stucco wall, the sandy ground: backstage details that would have been cropped out for a client’s souvenir print. As an introduction to photographic practices in West Africa, Lutterodt and Acolatse’s portraits create the establishing shot, articulating the concept of the studio as a fabricated scene and a laboratory for self-expression.

This exhibition, the first at the Met devoted to African photography, is curated by Yaëlle Biro and Giulia Paoletti and drawn entirely from the museum’s permanent collection. The majority of prints belong to the Visual Resource Archives in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, a photo study collection originally meant as a repository for supplemental research. In the 1990s, the former Met curator Virginia-Lee Webb began actively seeking photographs from Africa for the collection. Her initiative, which has continued with new acquisitions by successive curators, has created a fascinating and little-known archive of historic photography from the continent. The early-twentieth century postcards in In and Out of the Studio, for example, most on view for the first time, represent a typology for foreign audiences, then and now. Printed titles indicate “young women” or “indigenous type”; the subjects themselves remain nameless.

In contrast to these rigid portraits, groups of more casual pictures—vintage prints and modern reproductions from original negatives—deliver a remarkably intimate view into leisure and family life in Senegal in the 1930s and ’40s. When released from the strictures of the studio format, images of weddings or strolls in a park show a vision of pre-independence West Africa totally unlike the ethnographic propaganda disseminated at the time by colonial powers and by Western photographers. The curators have placed numerous examples in a vitrine, in which pictures are envisioned as objects to be held, traded, collected, or assembled into personal albums. Such buoyant tactility is also evident in several portraits by the renowned Malian portrait photographer Malick Sidibé, who captured the joie-de-vivre of 1960s Bamako, and whose painted glass frames add a flash of color to the exhibition’s otherwise duotone palette. An exquisite self-portrait by Sidibé envisions the artist as an impossibly handsome dandy, his white blazer set off by a burnt-orange frame with green and yellow leaves.

Beneath the generous and incisive captions, however, the Met’s accession numbers tell another story about the history of West African photography and the international marketplace. Mama Casset’s portrait of two Senegalese women, together with one by his brother, Salla Casset, was acquired for the Visual Resources Archive. These images, it would seem, are “evidence.” But in the last third of the exhibition, which includes works by Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, Samuel Fosso, and J. D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, the photographs are “artworks.” The legacy of Keïta, a prominent photographer who operated a studio in Bamako from 1948 to the early 1960s, is a particularly illuminating example. Since the 1990s, when his midcentury portraits were reprinted and marketed abroad, Keïta’s studio portraits have aroused questions of authenticity. Keïta used a large-format camera and wisely preserved his negatives, which allowed for modern reproduction in high definition. The new prints of Keïta’s work, conspicuously appealing to the market and made in European or American print labs, are crisp and brilliant and big. All printmaking is an interpretation of a negative, but the new prints revealed Keïta as a master. The splendid contrasting patterns of textiles, the perfection of the pose, the firm placement of radios or cars, the lustrous skin tones and gleaming accessories—these elements amount to a photographic humanism of the highest order.

The Met holds several modern Keïta prints from the 1990s and the two selected for In and Out of the Studio are incandescent. But they are installed together with three diminutive Keïta portraits that are contact prints made in 1975. In these, the tone is overcast, the blacks lack depth, and the overall sense is comparatively modest. As artworks, they’re deflating. As gifts to the Met from Susan Mullin Vogel, a curator and scholar of African art, they make a rather ironic coda to the long saga of Keïta’s prints and his checkered entanglement with foreign galleries and art dealers. (In 1991, Vogel organized the seminal exhibition Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art at the Center for African Art in New York, in which seven pictures, now identified as portraits by Keïta, were attributed to an “unknown photographer.” Vogel had collected a small selection of Keïta’s negatives on a research trip to Mali in the 1970s and commissioned contact prints by the American photographer Jerry Thompson. Regarding Keïta’s designation as “unknown,” she later insisted that she had misplaced her research notes, even though, at the time of the exhibition in New York, Keïta would certainly have been a known entity in Bamako.) Nevertheless, there’s no going back now—“revised,” marketable versions of Keïta’s portraiture are held in leading institutional and private collections, notably Jean Pigozzi’s Geneva-based Contemporary African Art Collection. And there’s no denying the profound impact Keïta has had on international appreciation of photography from Africa. The most significant statement of this exhibition might be the provocative ambivalence about fetishizing the vintage print: the image itself is an artwork subject to continual revision.

Keïta’s portraits, of course, are central to the recent history of African studio photography. But they should be grouped with African photographers only insofar as Richard Avedon should be grouped with American photographers or August Sander with the Germans. When it comes to the masters, geography is arbitrary. Take Samuel Fosso, who opened a studio in the Central African Republic as a teenager and later became famous for his exuberant, 1970s-era self-portraits. In a way, Fosso’s work doesn’t belong in this exhibition at all. Fosso’s commercial portraiture of subjects other than himself, which might have made a more appropriate inclusion, is rarely exhibited or published, probably because it’s not obviously distinctive from the inventory of other West and Central African studios of the era. Fosso’s particular genius, in his personal work, was to detach his “self” from his self-portraits, to presciently tap into a masquerade of archetypes, a postmodern strategy that would be celebrated in the West ten years later with the advent of the Pictures Generation. Today, Fosso’s career is entirely different from those of his West African contemporaries—he makes self-portrait series with estimable production values, shot in Paris with a team of assistants and printed for collectors, not studio clientele. Firmly established within the cross-cultural dialogues around conceptual photography, his closest peers are Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura, whose variations on self-portraiture form an endless inspiration to theoretical studies on gender identity.

In 1984, a fire destroyed Mama Casset’s studio and his archives. When one thinks about the prominence of Seydou Keïta—no doubt due to the preservation of his negatives—the loss is staggering, particularly given that the triumvirate of Keïta, Sidibé, and Fosso has dominated surveys of African photography for the last twenty years. More frequently, broader global surveys of portrait photography are beginning to include African artists on their own terms, and for their formal influence on the medium. The Met’s exhibition is meticulously organized and supplemented by erudite research; for most viewers, it will be an encounter replete with discoveries. Without the careful work by the Met’s conservators, half of the exhibition wouldn’t be available for public viewing, and this itself forms a contribution to the field, especially as one can see firsthand the benefits of preserving cultural patrimony. But the Met is late to the party. A more comprehensive account of African photography is essential, but will viewers ever see one at the Met? With so many stories about African photography still to tell, In and Out of the Studio is like a precious appetizer at an elite restaurant: the presentation is dazzling, but you’re ravenous for more.

Brendan Wattenberg is the managing editor of Aperture magazine.

In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 3, 2016.

The post In and Out of the Studio appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 10, 2015

Jeff Wall at Marian Goodman

In Jeff Wall’s most recent work, massive prints impart a cinematic quality to everyday life.

By Zoë Lescaze

Installation view of Jeff Wall, Staircase & two rooms, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. All Installation photos by Cathy Carver

Interpreting Jeff Wall’s photographs can feel like trying to catch an animal, one that knows it’s quicker than you: A possible meaning will stand relatively still, humoring one’s advances, only to suddenly dart out of reach. This enigmatic quality stems partly from the tension between Wall’s subject matter and his method. For nearly forty years he has photographed seemingly mundane moments that, in fact, are meticulously staged. These images, with their carefully scouted locations and casts of amateur actors, thwart our attempts to deduce the internal logic driving their creation. Alluringly elliptical, they lapse into banality when the formula falters.

Installation view of Jeff Wall, Changing Room, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Wall’s current exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York is compact, comprising only eight large photographs, but eclectic in its motley subject matter. Approach (2014) depicts a short, seemingly homeless woman standing alone on a dark, trash-scattered sidewalk. She is wrapped in a blanket, gazing down at a makeshift shelter of battered cardboard boxes, as though visiting a grave. In stark contrast on a nearby wall, Changing Room (2014) transports the viewer to a brightly lit fitting room in Barneys New York, where a slim woman wearing a crisp red dress with white flowers is trying on another garment. From the waist up, a tangle of busily printed fabric has transformed her body into a strange, sculptural mass. It’s unclear whether she’s wrestling this second piece of clothing on or struggling to escape the frenzy of garish zebra stripes, python scales, paisley teardrops, and kaleidoscopic arabesques. Both Approach and Changing Room share a certain suspense, needling us with unnerving narratives we cannot fully unravel.

Installation view of Jeff Wall, Approach, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

When they fail to conjure any intrigue, Wall’s images feel tedious and their enormous size only exaggerates their flaws. Blander pictures like Office Hallway, Spring Street, Los Angeles (1997), a black-and-white photograph of a man pausing in a dingy hallway, can make one nostalgic for the dark humor that characterized Wall’s ambitious earlier works. One craves the macabre complexity of The Vampires’ Picnic (1991) and Dead Troops Talk (a vision after an ambush of a Red Army patrol, near Moquor, Afghanistan, winter 1986) (1992), in which mangled soldiers lounge around the battlefield joking about their fatal wounds.

Installation view of Jeff Wall, Listener, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery