Aperture's Blog, page 149

October 30, 2015

Report from The Ballad: Live, Aperture’s Fall Benefit

On October 26, Aperture Foundation celebrated photography and Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency with live performances at the annual fall benefit.

Atmosphere. All photographs courtesy of media sponsor Patrick McMullan and Clint Spaulding

When Nan Goldin took the stage as the honoree of Aperture’s Fall Benefit on October 26, The Ballad: Live, she spoke about the beginnings of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, first published by Aperture in 1985. The book’s publication, she said, was thanks to curator and writer Marvin Heiferman, who introduced her work to former Aperture publisher Michael Hoffman. “If it wasn’t for him the book would have never happened,” she said of Heiferman. “We spent six months with the pictures laid out on the floor, reediting and reediting and reediting.” The resulting book, a seminal work of documentary photography, was the focal point of Aperture Foundation’s annual fundraiser, which drew more than 800 guests and raised approximately $700,000 in support for publications, public programming, and educational initiatives. The event was co-chaired by Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Judy Glickman Lauder, and Anne Stark Locher. The evening, presented by U.S. Trust, centered on a live performance to accompany Goldin’s slideshow presentation of The Ballad, which depicts how her circle of friends and lovers lived during the late 1970s and early 80s. A performance by Laurie Anderson, Martha Wainwright, Pat Irwin, Samuel Rohrer, and The Bush Tetras scored the impactful, iconic images of a bygone New York City.

Laurie Anderson and Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin and Marvin Heiferman

Samuel Rohrer, Laurie Anderson, Pat Irwin, Martha Wainwright, Dee Pop, Pat Place, Cynthia Sley, and Julia Murphy

Laurie Anderson

Martha Wainwright

The influence of music on photography played into many other of the night’s festivities. The artnet-sponsored silent auction, “The Playlist,” gathered 100 photographs by artists such as Matthew Brandt, Olivia Bee, Hank Willis Thomas, and Larry Fink, inspired by songs from “Tiny Dancer” to “Blitzkrieg Bop.” A collection of songs about photographs, provided the soundtrack for DJ Bob Gruen, during the VIP preview, where guests mingled in Terminal 5 with prominent artists, gallerists, writers, and patrons in the world of photography. The benefit weekend had earlier kicked off with an array of VIP events, including an exclusive kick-off cocktail party at U.S. Trust, and studio visits with Letha Wilson, Hannah Whitaker, and Hank Willis Thomas.

Hank Willis Thomas and Chris McCall

Elizabeth Kahane, Leonard A. Lauder, and Judy Glickman

Lesley A. Martin and Celso Gonzalez-Falla

Lea Rizzo and Doug DuBois

Jim O’Shaughnessy, Aperture trustee Melissa O’Shaughnessy, Jamie Camhi, and Joshua Greenberg of U.S. Trust

Helen Nitkin, Joel Rosenkranz, Pamela Ellison, Herbert Kasper, and benefit co-chair Anne Stark

Aperture board chair Cathy Kaplan with Eve Reid

Sara Friedlander, vice-president and head of evening sale at Christie’s, presided over the live auction, which featured eleven works by artists such as Richard Learoyd, Stephen Shore, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Nan Goldin. Guests enjoyed hors d’oeuvres and dinner by Pinch Food Design as well as tequila sunrises by Espolón Tequila and other libations by Anheuser-Busch, and Wölffer Estate Vineyard. A DJ set by Mick Rock closed out the night.

Jeff Hirsch with Michael and Cara Hejtmanek

Gina Nanni and Glenn O’Brien

Sara Friedlander

The 2015 Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction was generously supported by: U.S. Trust (Presenting Sponsor), Foto Care, Anheuser-Busch, artnet, Christie’s, Espolón Tequila, Fine Art Frameworks, Hahnemuhle, LTI Lightside, Merissa Lombardo, Tekserve, Wölffer Estate Vineyard, and Patrick McMullan (media sponsor).

Mick Rock

Juliane Hiam and Gregory Crewdson

Chris Boot, Mary Ellen Goeke, and Tom Schiff

Aperture Benefit cochairs Judy Glickman Lauder and Elizabeth Ann Kahane

Additional party photos are available on patrickmcmullan.com

Tap here to learn more about Aperture Foundation’s fundraising events and Aperture Membership.

The post Report from The Ballad: Live, Aperture’s Fall Benefit appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Wins Lucie Award for Book Publisher of the Year for Tiny: Streetwise Revisited

By The Editors

Mary Ellen Mark, Tiny, 1983 All photographs © Mary Ellen Mark

Tiny holding Papas, Seattle, 1983

Tiny with her friends on Pike Street , 1983

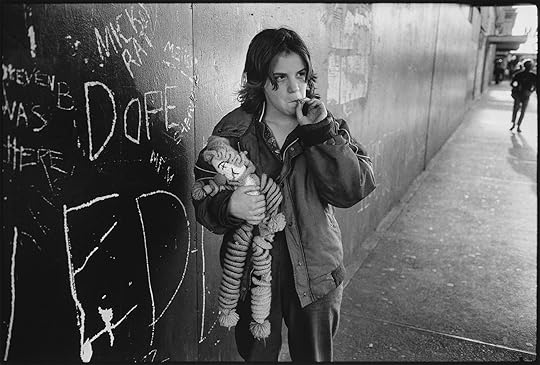

Lillie and her rag doll on Pike Street, Seattle, 1983

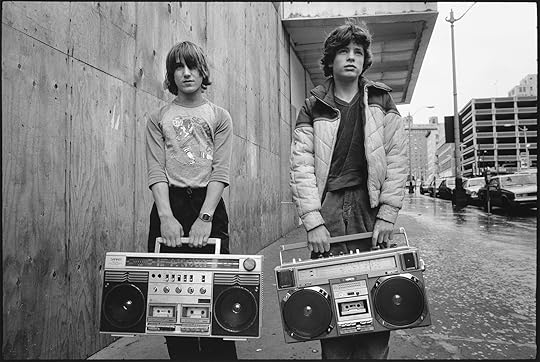

White Junior and Justin, 1983

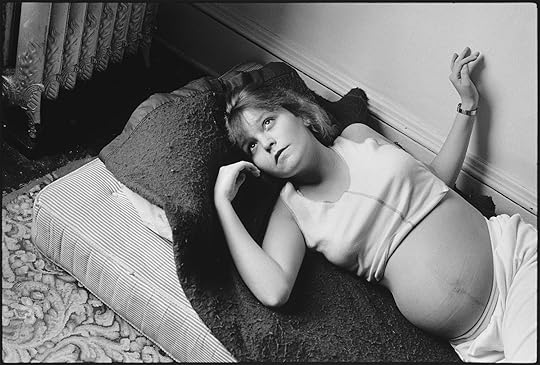

Erin (who previously went by her street name “Tiny”) pregnant with Daylon, Seattle, 1985

Erin and her mother Pat, along the road, Seattle, 1993

Rayshon and Erin on the couch, Seattle, 1999

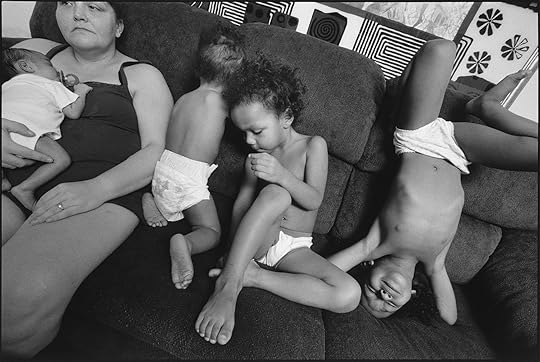

Erin holding Kayteonna with Julian, E’Mari, and Ranaja on the couch, Seattle, 2004

On October 27, Aperture received the Lucie Award for book publisher of the year (classic) for Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, one of the last two books Mary Ellen Mark conceived and realized before her death. In 1983, Mark first photographed a group of homeless and troubled youth who made their way on the streets of Seattle as pimps, prostitutes, panhandlers, and small-time drug dealers. Streetwise was published in 1988, after the film of the same name by Mark’s husband, Martin Bell, premiered in 1985; it received critical acclaim for its portrayal of life on the streets and introduced us to “Tiny” (Erin Charles)—a thirteen-year-old prostitute with dreams of a horse farm, diamonds and furs, and a baby of her own.

After meeting Tiny thirty years ago, Mark continued to photographer her, creating what became one of Mark’s most significant and long-term projects. Today, almost forty-five, Tiny has ten children, the youngest five of whom are by her husband, Will, and her life has unfolded in unexpected ways. Texts in the book are drawn from conversations between Tiny and Mary Ellen Mark as well as Martin Bell. Streetwise Revisited is an examination of intergenerational poverty as well as homelessness, education, healthcare, addiction, mental health, and child welfare—in addition, the book gives insight into a relationship sustained between artist and subject for more than thirty years.

On November 4, at 6 p.m., Aperture will host A Toast to Mary Ellen Mark, a tribute to her life and work, at Aperture Gallery in New York. The slideshow above features work by Mark documenting Tiny, her friends, and her family from the 1980s into the present day.

Tap here to find Tiny: Streetwise Revisited on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Aperture Wins Lucie Award for Book Publisher of the Year for Tiny: Streetwise Revisited appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 28, 2015

Exhibition: Paul Graham on The Whiteness of the Whale at Pier 24 Photography

San Francisco’s Pier 24 Photography recently opened British photographer Paul Graham’s exhibition The Whiteness of the Whale, the venue’s first-ever presentation of a single artist. The show, which is on view until February 29, 2016, centers on three of the acclaimed photographer’s series, comprising a trilogy: American Night (1998–2002), a shimmer of possibility (2004–06), and The Present (2009–11). Through the more than sixty images on view, Graham approaches issues such as race, inequality, urban life, and poverty, while considering how the camera’s mechanics can be considered in relation to a subject. Allie Haeusslein, associate director at Pier 24, spoke with Graham about the exhibition and the thinking behind his work, his unique approach to installation, and reading Moby Dick.

The Whiteness of the Whale, 2015 (Installation View). Courtesy Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco

Allie Haeusslein: Your exhibition at Pier 24 Photography includes three bodies of work made in the United States—American Night (1998-2002), a shimmer of possibility (2004-06), and The Present (2009-11)—and is titled The Whiteness of the Whale, a reference to Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851). What was your experience reading that book?

Paul Graham: Well . . . I’m no lit graduate, but I think the book touches on many major subjects. Especially relevant here are issues of monomaniacal blindness, and how chasing one thing obsessively can drive to destruction. To be honest, I found it a hard read—inspired and crazy in places, insightful in others, racist and offensive in others again.

AH: Why did you decide to read Moby-Dick the first time?

PG: Because of American Night—the white images, the white whale, etc. We ended up using a quote from Moby-Dick on the back cover about seeing and whiteness. [“Pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper; and like wilful travellers in Lapland, who refuse to wear coloured and colouring glasses upon their eyes, so the wretched infidel gazes himself blind at the monumental white shroud that wraps all the prospect around him.”] It’s nice to return to that book now with The Whiteness of the Whale. Melville’s eponymous chapter is on the edge between genius and madness and that intrigues me.

Woman sitting on sidewalk, New York, from the series American Night, 2002

AH: So is American Night the first project that resulted from your serious focus on making work in the U.S.?

PG: If you’re talking about the first body of work, then, yes. But you don’t start out thinking, “I’m going to make a body of work about America.” You just start taking pictures and looking for truly interesting photographs. And that can take a month, or a year, or multiple years—to find some amazing, unusual, different image, which is the gateway through which you will pass into uncharted territory. In this case, I found these overexposed white pictures, which described a sort of invisibility of the dispossessed in this country. That was a fresh visualization worth pursuing—making near-invisible photographs.

AH: Where were you making these pictures?

PG: The locations in American Night were basically along the compass points across the United States. North was Detroit; South was Memphis and Atlanta; East was New York; West was greater Los Angeles. The pictures were geographically spread out so people didn’t think, “Oh, isn’t inner-city New York terrible, or Detroit . . .” It wasn’t about one location; it was about something pervasive across the country.

AH: You made these near-invisible photographs through deliberate overexposure. How did you decide to make pictures in this way?

PG: The idea principally came about during a visit to Memphis where a portrait from End of an Age (1996–98) was in a group show. One afternoon, I went to the cinema—lazy me—and when the movie finished, I walked out a side exit door that led straight into the bright afternoon sunlight. I stumbled around thinking, “What is going on here?” While completely blinded by the brightness, I noticed this slightly unhinged guy shouting to himself as he walked across the car park. And I realized how amazing this whole scene was. With my overwhelmed, burnt-out vision, this poor man appeared to be crossing a wasteland of whiteness, unnoticed by the world.

White SUV outside new house, California, from the series American Night, 2002

AH: There are also very dark photographs taken in cities and bright “Technicolor” images of large homes included in American Night. How do these three different kinds of pictures work together?

PG: The earliest pictures for American Night were the dark ones. In those pictures, I was working on the streets of New York like a classic street photographer, but didn’t have any purpose for them.

Two or three years later, I discovered the white pictures. And I realized that was the breakthrough. While I wanted the majority of the images to be these near-invisible white pictures, the dark pictures were important too, as a counterbalance, and I wanted to include the American Dream—presented as glorious full-color McMansions. I worked with these three types of imagery—white, dark, and “Technicolor”—looking for ways to integrate them. Ultimately, the white images predominate; they’re around seventy-five percent of the pictures.

New Orleans (Cajun Corner), from the series a shimmer of possibility, 2005

Allie Haeusslein: As you moved on to making pictures for a shimmer of possibility, did your working process and concerns feel like a departure from, or a continuation of, long-standing interests?

PG: In all my works, there is a similar engagement with the world through photography and the act of being in the world. shimmer also engages with the social fabric of the United States, so in that sense it’s not a departure. It is, however, structurally different with these extended, flowing sequences—the “visual haikus”—of images.

AH: You have linked the idea of the “visual haiku” to the short stories of Anton Chekhov. What is the connection?

PG: As I was reviewing scanned negatives on my computer screen, I started to notice these interesting flickering sequences. Even though I was still shooting analog, there was no traditional contact sheet. Instead, I was working with scans—digital files—of the work. As the pictures come on your screen, and you flick next, next, next, you get this stuttering sequence. The actual process of photographing, of seeing, is right there: the realization of the world as it arrives and departs on your screen.

As for Chekhov, well, he describes the most ordinary things in his short stories. There’s an openness to his simple descriptions of everyday moments. I realized these stories were connected to the sorts of pictures I was making—not nineteenth-century Russia, but today’s America—people waiting at bus stops, cutting grass, or scratching a lottery card in hopes of winning. It wasn’t so much an influence as a validation that this was a profound and worthwhile way of working, however humble it may seem.

San Francisco (Woman in Silver Jacket), from the series a shimmer of possibility, 2006

AH: As you designed the sequences in shimmer, did you always use consecutive images, or were there instances where you eliminated exposures from the final sequence?

PG: Some pictures are left out because there’s a pause or they’re repetitious. I’m not literally showing every frame from a five-second film. That’s not the idea.

In a haiku—there’s a moment where it breaks away and touches upon the weather or the season, like “blossoms,” just a word or two, hinting at something beyond the instant concern. I tried to integrate that breakaway into some of the sequences. For instance, in the pictures with the man cutting the grass, one frame looks at his brown minivan, in all its 1980s glory. In the pictures where I’m walking behind the couple carrying home their Pepsi, I glanced to the side at some children playing in the garden with plastic bags and took a picture of them. It’s a little glance aside from the main thread—to note the sunset or the rain falling or a child playing.

AH: Was the working process for The Present—a body of work made on the streets of New York—significantly different from when you were on the road making pictures for American Night or shimmer?

PG: I lead a weird artist’s life, so I don’t go to work in midtown or a regular job where I clock-in and clock-out. When I wander around Wall Street or Midtown and experience the city’s business life, it’s like another world. And one of the great things about New York is how you can travel on the subway for just fifteen or twenty minutes and find yourself somewhere else. When you come out through another hole in the ground, you are in Ghana or Israel or Pakistan because each different neighborhood has its own ethnicities and histories.

North Dakota (Moonrise at Garage), from the series a shimmer of possibility, 2005

AH: Many people are surprised to learn that the photographs in The Present were completely unstaged. Can you talk about the process of making those pictures?

PG: If you look at Winogrand’s contact sheets, he took five pictures of the same thing and then printed the one he thought was the most interesting. And that was great, of course. Likewise, I’m taking five pictures, but choosing two, or very occasionally three, to show this flowing consciousness of time, to get a different sense of the city, time, people, and life’s flow. It takes a different direction from Henri Cartier-Bresson or Winogrand, who worked to capture the singular instant, but it continues in that lineage and connects with their amazing work. In short, there’s an attempt to shift our awareness from a sort of spotlight to a floodlight.

AH: You draw our attention to the idea of seeing through repeated allusions to sight and blindness in The Present. Was that something you noticed during the editing process—that these subjects appeared in the work?

PG: It’s in American Night as well. The first and last pictures in the sequence of dark pictures in New York are of a blinded man and a woman whose eye is covered over with gauze. In The Present there are quite a few pictures of blind people with white sticks in the city. I’ve always been interested in notions of sight, seeing, and blindness. And American Night is primarily about blindness—willful blindness or psychological blindness.

The Whiteness of the Whale, 2015 (Installation View)

AH: The installation of your work typically differs significantly from traditional modes of presenting photographs, namely the ubiquitous single line on the wall. How did you develop this unconventional approach to installation?

PG: I think I learned how to install from working on books and figuring out how to lay them out in more exciting ways. In the 1980s, I laid out my publications in a fairly classical fashion. I then started working with Scalo and their editors in the 1990s. But those books were the Scalo look, rather than my look. From then on, especially with the advent of Adobe’s InDesign program, I managed layouts myself—with American Night, then with shimmer, where we produced a twelve-volume set, and then The Present, with its multiple gatefolds.

I realized I could take what I had learned in book layout and apply it to the wall—high, low, sizes floating around, no grid. You can transfer that approach to the wall and it works very well, using gallery corners in the same way one might use the edge of a page, or you can hang high on the wall or low on the wall in the same way as on a page. But slowly, my approach to installation became its own thing, related but different.

AH: Do you think anything about your relationship to American politics is reflected in the photographs you have made in this country?

PG: Most photographers worth their salt rely on empathy and concern for their fellow citizens on this planet, rather than on political ideology. Inevitably, that empathic connection with other human beings leads one to certain sympathies. But I’m certainly not a spokesperson or a mouthpiece for the Democrats or Socialism or anything like that.

AH: You did three bodies of work in Britain, and now there are three bodies of work you’ve done in the United States. Is there something about this three-part organization that suits the way you made work in these two places?

Paul Graham: I feel it’s just a coincidence. Though, with American Night, shimmer, and The Present, there is a connection to the three principal controls of the camera—aperture, shutter, and focus . . .

New Orleans (Woman Eating), from the series a shimmer of possibility, 2005

AH: At what point did you become conscious of the fact these three bodies of work touch on the three controls of the camera?

PG: It occurred to me toward the end of shimmer. I also realized by using very shallow focus on the street in The Present that I could deal with specific individuals in terms of one’s awareness very effectively. And that would neatly encompass all three respects. Of course, the three camera controls—shutter, aperture, and focus—are really not that interesting in themselves. I mean—so what? But when you start to think of them in terms of the shutter controlling time, the aperture adjusting light, and the focus directing our attention or consciousness, they become a lot more powerful and fertile: time, light, consciousness.

Art often does that—it speaks both of itself and of the stuff it is made of. I like that about this work. It speaks about America, about seeing, and about photography. That makes me happy.

The post Exhibition: Paul Graham on The Whiteness of the Whale at Pier 24 Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 26, 2015

August Sander: Prints for the Aperture Monograph, Printed by His Son Gunther Sander

August Sander’s profound influence on the history of photography is impossible to overstate. But, in the mid-1970s, when Aperture published a volume of his work, only a handful of books on the German photographer’s work were in print. Exhibited in New York for the first time, the prints made by Sander’s son, Gunther, for the Aperture monograph are the subject of an exhibition at New York’s Deborah Bell Photographs, which features some of the most iconic portraits of the twentieth century.

This article originally appeared in Issue 18 of the Aperture Photography App.

By Brendan Wattenberg

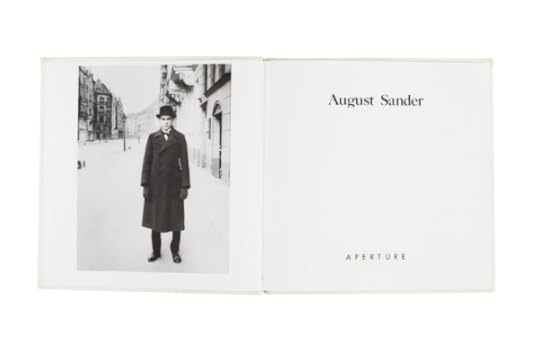

Pages from August Sander: the Aperture History of Photography Series (1977). Photograph by Cassidy Paul.

In 1977, Aperture published a slim volume of photographs by August Sander, for the seventh entry in the Aperture History of Photography Series. With a selection of forty-three portraits from the German photographer’s expansive, early twentieth-century study of German society, the Aperture book was then one of the few available introductions to Sander’s work. At the time, his son Gunther Sander had prepared a set of prints for the bookplates, following his father’s technique. The younger Sander deposited the prints in Cologne with Könemann, the publisher of the German edition, and they were soon forgotten. More than thirty years later, after their discovery in a private collection earlier this year, Gunther Sander’s prints are now the subject of a jewel-box exhibition at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York.

Installation view of August Sander: Prints for the Aperture Monograph, Printed by His Son Gunther Sander. Courtesy Deborah Bell Photographs.

August Sander was born in 1876 in Herdorf, a mining region near Cologne. In his youth, as an apprentice to a foreman, Sander was chosen to assist a landscape photographer contracted by a local mine. He soon became fascinated by photography. After a stint in the army, he worked for a photographer in Linz, Austria, and later bought the studio. By 1910, having returned to Cologne, Sander began cycling around the rural lands of the Westerwald to make portraits of local farmers and tradespeople. These images, the first entries into Sander’s prolific catalogue of German types, display the clarity and precision that would later become the hallmarks of New Objectivity, a Weimar-era artistic response to the chaos of World War I.

August Sander, Confirmation Candidate, Westerwald, 1911. All following photographs courtesy Galerie Julian Sander / Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne

Prior to Aperture’s monograph, the primary book on Sander’s portraiture was Antlitz der Zeit (“Face of Our Time”), published in 1929 by Transmere Verlag in Munich. Sander intended the sixty images of Antlitz der Zeit to be a preview of his anticipated multivolume series, which would divide his photographs of German citizens into seven major categories and numerous subgroups. In contrast to Antlitz der Zeit, which is sequenced according to the structure of Sander’s portfolios—beginning with the farmer, ascending through the classes and professions, and concluding with the “last people,” the destitute and the dying—the Aperture book contains a populist, illustrative combination of memorable portraits. Many images are masterpieces, ranking among the most iconic photographs in the history of the medium.

The exhibition at Deborah Bell Photographs presents all forty-three prints in the same order as in the Aperture book, elegantly framed and set in the window-mats of pebbled white paper favored by Sander. The modestly scaled images and the narrow salon of the gallery belie the arresting power of the portraits, which collectively provoke a peerless, insatiable curiosity. Seeking to portray every type of German citizen with the same amount of concentration, Sander provided an immensely detailed transcription of German life, from the clothing and hairstyles of the time, to the physiognomy that characterized the conditions of a subject’s working life.

August Sander, Bicyclists, Cologne, 1924.

Sander’s lucid approach no doubt owed to his consistent use of glass plate negatives, which allowed for extreme detail. For the expert viewer acquainted with the sociology and material culture of early twentieth century Germany, the images contain a wealth of information to be endlessly scrutinized. The painters, sculptors, musicians, and prominent intellectuals to be filed under “Trades, Classes and Professions” were often identified in later publications on Sander, which opens up the possibility of reading deeply into their work. But, for the unnamed peasants, clergymen, high school students, athletes, and homeless figures, who appear as living sculptures, what can we possibly learn about their inner lives? Though New Objectivity photography aspired to transparency without adornment, Sander’s portraits protect as much as they reveal. Like the comparative industrial studies by Bernd and Hilla Becher, who referred to New Objectivity as a model for their systematic typologies, Sander never goes out of style.

Circus People, Düren, 1930

The exhibition, which follows Gerd Sander’s selection, is notable for its differences from the sequence Sander originally chose for Antlitz der Zeit. The indelible classics, Young Farmers (1914) and Boxers (1929), are there, but so is Circus People, Düren (1930), an extraordinary multiracial portrait of seven performers listening to a gramophone, which wasn’t included in Antlitz der Zeit. By the mid-1930s, the Nazi party had declared Sander’s project antisocial, halting sales of the book and destroying the printing plates, ostensibly in retaliation for the resistance politics of Sander’s son, Erich. In a portrait such as Circus People, it’s easy to see how Sander’s democratic vision of Germany, which brought all types into its genealogy, implicitly defied the idealized Aryan body of Third Reich propaganda.

Working Students, Cologne, 1926 (Sander’s son Erich is at far left.)

For Working Students, Cologne (1926), one of the final images of the exhibition and the Aperture book, Sander photographed his son Erich together with three young men. With its comparative approach, and its voluminous yet subtle range of poses and facial expressions, Working Students is a precedent for Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits of adolescents, Nicholas Nixon’s multi-decade series The Brown Sisters, and Thomas Ruff’s untitled 1980s portraits of artists and friends at the Kunstacademie Düsseldorf. The wake of Sander’s influence is impossible to measure. Sander’s subjects are types and originals, individual and universal. “The portrait is your mirror,” Sander told his grandson, Gerd. “It’s you.”

Brendan Wattenberg is managing editor of Aperture magazine.

August Sander: Prints for the Aperture Monograph, Printed by His Son Gunther Sander is on view at Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, through October 31.

The post August Sander: Prints for the Aperture Monograph, Printed by His Son Gunther Sander appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

7 Exhibitions to See in October

By Freddy Martinez

The Atlas Group/ Walid Raad, Hostage: The Bachar tapes (English version), 2001; Video (color, sound), 16:17 min, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Walid Raad

Walid Raad at the Museum of Modern Art (through January 31):

The Museum of Modern Art is staging the first comprehensive American survey of the Lebanese artist Walid Raad. The displayed work includes photography, film, sculpture and performance made during last twenty-five years for two long-term projects The Atlas Group and Scratching on things I could disavow. The exhibition focuses on Waad’s use of fiction and narrative, while also exploring the political tensions of the Middle East. The photographs imagine as much as they inform. They are both poetic retellings of history and troubling documents of conflict.

Still from Dziga Vertov, Man with a Movie Camera, 1929, black-and-white film, 68 min. Image provided by Deutsche Kinemathek

The Power of Pictures at the Jewish Museum (through February 7):

It’s no secret that photography has an ugly, propagandistic side: the camera was even once declared just as important as the gun for “class struggle” by Lenin. And, in Russia, from the time after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 through the 1930s, artists worked for and caused great social change. The Power of Pictures, on view at the Jewish Museum, explores how thirteen Soviet photographers as well as ten filmmakers from this period of history used photographs to spread Communist ideologies. In addition to the photographs and cinematic works, film posters, vintage books, and newspapers also showcase examples of art working in hand with politics.

Yu Lik Wai: It’s A Bright Guilty World at WhiteBox gallery (through November 8):

The Hong Kong-born, Beijing-based artist Yu Lik Wai has his first solo U.S. exhibition at Whitebox gallery. A renowned filmmaker and cinematographer, Wai is known for depicting scenes of contemporary urban life in China, often of existential despair. His images of empty built environments, already symbolic of neglect, signal alienation more absurdly when shot in flourishes of color. Alongside his richly chromatic photographs, a three-channel video holographic installation entitled Flux is also on view.

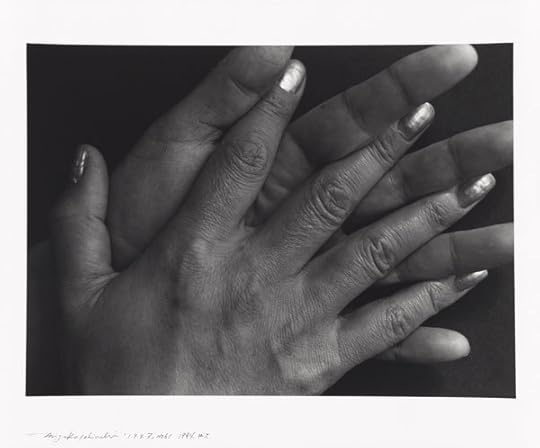

Ishiuchi Miyako, 1·9·4·7 #61, 1988 – 1989; Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows at J. Paul Getty Museum (through February 21):

Ishiuchi Miyako, interviewed in this fall’s “Interview Issue” of Aperture magazine, has a solo exhibition of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles. With the last forty years, Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows spans nearly Miyako’s entire career. From her stunning early work through to her most recent series, “???/hiroshima,” the retrospective presents thirty-eight photographs that give a satisfying taste of her evocative and haunting output.

Kadir van Lohuizen, Via PanAm, Panama; © Kadir van Lohuizen

Via PanAm at the Bronx Documentary Center (through December 13):

After stops in Chile, Costa Rica, and Luxembourg, the award-winning exhibition Via PanAm visits New York at the Bronx Documentary Center. Combining audio-visual installations and photographs, the exhibition showcases the photographer Kadir van Lohuizen’s journey from southernmost Chile to the top of Alaska, as he documents stories of historic and contemporary migration to the United States. Shot with personal intimacy, the videos and photographs bluntly depict the 40, 000 kilometer path to reflect the complex stories behind migration.

Graciela Iturbide, Cementerio / Cemetery, Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1988; Courtesy of Throckmorton Fine Art © Graciela Iturbide.

Women Pioneers: Mexican Photography I at Throckmorton Fine Art (through November 14):

The first gallery to exhibit artwork by Frida Kahlo anywhere in Mexico was run by Lola Álavarez Bravo. Years later it was Graciela Iturbide who elevated Mexican photography to the top of the world. Both women were photographers in a field dominated by men.Women Pioneers: Mexican Photography I, on view at Throckmorton Fine Art, presents their work, as well as seven other women working in Mexico, from the early 20th century to today, including Tina Modotti, Kati Horna, and contemporary artists such as Cristina Kahlo. Together the exhibition highlights the storytelling, humanity, and spirit present in the work of these trailblazing women.

![GL-10150---Kelp-thrown-into-a-grey,-overcast-sky,-Drakes-Beach,-California,-14-July-2013[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1445916744i/16718927._SY540_.jpg)

Andy Goldsworthy, Kelp thrown into a grey, overcast sky, Drakes Beach, California, 14 July 2013; Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York © Andy Goldsworthy

Andy Goldsworthy: Leaning into the Wind at Galerie Lelong (through December 5):Andy Goldsworthy will have his largest exhibition of work to date at Galerie Lelong. The exhibition of photography and films includes recent work made in the last three years, some never before seen, and vintage work made in the 70s and 80s. Uninterested in outcome or planning, Goldsworthy, in both his new and early work, shows his body in various states of action—whether throwing, spitting, or jumping—to engage the photographic frame with movement and energy.

The post 7 Exhibitions to See in October appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 23, 2015

Issue 18 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 18:

● An interview with Rosalind Fox Solomon from “The Interview Issue” of Aperture magazine

● A report on an exhibition of work by August Sander

● An interview with Paul Graham

● An excerpt from Jimmy DeSana’s Suburban

● A portfolio from Tiny: Streetwise Revisited

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 18 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Wolfgang Tillmans at David Zwirner

By Gabriel H. Sanchez

Wolfgang Tillmans, Installation view from the 2015 solo exhibition PCR at David Zwirner, New York. All photographs courtesy David Zwirner, New York

PCR, Wolfgang Tillmans’s first exhibition with David Zwirner Gallery, captures a sensibility fixed on examining the pliability and immediacy of a photographic document. Its title is taken from a procedure in molecular biology called “polymerase chain reaction,” which in a manner similar to a photographic process is capable of amplifying a single strand of DNA into millions of identical copies. The show taps into themes Tillmans has explored since the early 1990s–vibrant images of bustling nightclubs, casual snapshots of friends, the obscurity of his surroundings, and the ephemeral moments only a photograph is capable of documenting– rendered still with a swift, voyeuristic perspective. Among these images are abstractions and photograms from his Table Works, (2005-ongoing), and Silver series, (1998-ongoing), that also demonstrate how his practice has evolved over the years to encompass a more self-referential approach to his photography.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Installation view from the 2015 solo exhibition PCR at David Zwirner, New York.

Through both of Zwirner’s gallery spaces, seemingly disparate photographic elements of his output–abstractions, personal snapshots, sculptural gestures, and even magazine cutouts–are hung in Tillmans’s recognizable and erratic style across the gallery walls. The manner in which they are shown invites viewers to contemplate images as objects in their own right, a reoccurring theme in Tillmans’s work that has become increasingly poignant as more and more of today’s digital images lack any physical form at all. In the same way that digital images now roam today’s social web without any context or intention, Tillmans creates a mosaic of subject matter without any form of observable reason. For instance, a forceful and sensual encounter with a lover in arms and legs, 2014, receives the same treatment and reverence as a seemingly benign encounter with weeds budding from between cracks in the sidewalk in Weed, 2014.

arms and legs, 2014

Among the over one hundred works on view, we also find several unexpected curiosities that demonstrate how Tillmans has continued to broaden his practice. A new multipart sculpture titled, I refuse to be your enemy, 2015, takes an ultra-reductive approach in acknowledging the physical nature of photography. The installation consists of eight wooden tables with neatly laid rows of blank sheets of paper laid on top: here, Tillmans bring our focus to the slight differences of the papers’ varying size, color, and opacity. One could read each of these sheets of paper as the shell of an image, the physical form left behind as photographs are digitalized and continue to transcend their material form.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Installation view of Instrument, 2015

In a darkened room of the gallery, a new multi-channel video called Instrument, 2015, shows a man a dancing in a repetitive ritualistic fashion, wearing nothing but pair of briefs. The right channel of this nearly six-minute film reveals the man’s bouncing shadow reflecting on an adjacent wall within the video. For audio, Tillmans has put the repetitive tapping of the man’s feet though a digital feedback-loop, continuously building on itself until it becomes a droning dance track. The effect reflects the cyclical, and at times willfully repetitive, nature of Tillmans’s presentation. With that, each channel appears gritty and framed with minimal production value, which once again steers towards a sensibility fixated on documenting reality, or at least what appears to be real.

Adalbert Garden, 2014

From this video to the cascade of images throughout the gallery, it can be difficult not to feel completely overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of images–photographs that were once invariably chained to their context stripped of meaning. But with that, Tillmans reassess the value of his subjects. A picture of budding sprouts from his garden, is allowed the same attention as a political protest against Boko Haram in Berlin; while still lifes of fruit and foliage are valued with the same respect given to the dirty laundry shown in Wäscheberg, 2012. Several pictures are found replicated in various sizes in the gallery, as if balancing the scales to any hierarchies that might develop. With that, PCR illustrates the complex networks of images on today’s Internet, our unprecedented documentation of the world around us, and our concession to forfeit context in favor of distribution.

PCR is on view at David Zwirner through October 24.

The post Wolfgang Tillmans at David Zwirner appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 22, 2015

The Lives of Others

A look at how some recent photobooks, featuring African subjects, rehash pejorative tropes. This article first appeared in Issue 17 of the Aperture Photography App.

By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

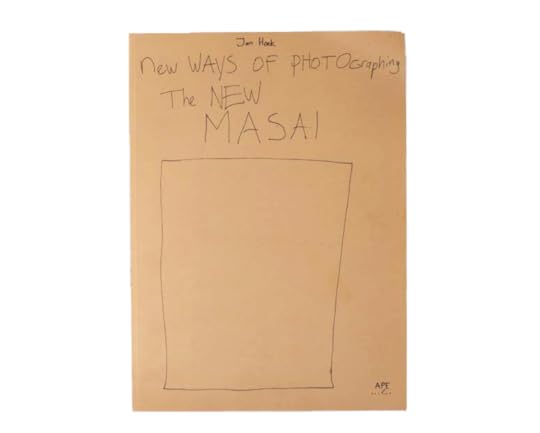

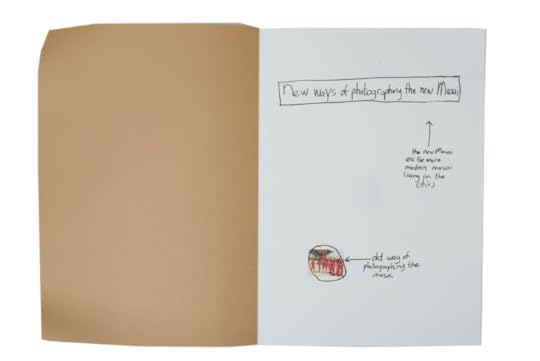

The cover of Jan Hoek’s New Ways of Photographing the New Masai (Art Paper Editions, 2014)

Dutch photographer Jan Hoek’s New Ways of Photographing the New Masai (Art Paper Editions, 2014) has the appearance of a handwritten school notebook. Its spine and cover are adorned with a mishmash of spidery letters that spell out the title in an irregular and child-like script. The book scarcely contains any writing to contextualize the project and define for readers what is meant by “old” versus “new” ways of photographing this traditionally semi-nomadic tribe of Kenyan people, save for a very small image of leaping tribesmen that appears on the book’s first page. That image is uncredited, and appears to be a fairly conventional travel photograph in which the Masai are photographed jumping skyward in traditional red costume while grinning for the lens. Hoek’s website offers some more information:

“The Masais are always photographed the same: jumping in nature while wearing traditional outfits and jewellery. Almost like it is a group of animals. But more and more Masai start to live in towns and buy their first Nikes and put mobile phones in their stretched ears. Together with seven urban Masai I tried to find a new way to photograph the new Masai.”

Hoek’s book contains a series of portraits of seven Masai tribespeople, made according to what we are told are their preferences as to how to be pictured:

Filemon: “Doesn’t like: To be photographed naked.” Seuri: “Doesn’t like: To be photographed naked.” Mike: “Likes: Masais [to be] photographed in a modern way.”

We later discover only six are true Masai tribesmen, and that the seventh individual falsified his identity. His portraits are still included but appear struck through with thin black lines, so that his deception is theatrically punished, while the competence of whomever he deceived is left excluded from the record, along with the nature of the relationships and intentions that led Hoek to make this book.

Pages from New Ways of Photographing the New Masai

The provenance of these pictures; the very reason for their having been made at all; the manner of their making; the nature of the “collaborative” relationship with the photographer; the necessity that Westerners see Masai tribesmen according to Hoek’s “new way”—none of these crucial but unstated questions—are deemed worthy of an answer. Hoek’s “New Masai” are left as protagonists and independent actors, reaching out to us (apparently) at their own behest, and ostensibly in the manner of their own choosing. The specific hopes, desires, and experiences of seven people are reduced to an itemized list that continually restates their desire not to be forced to strip naked for the delectation of a Western lens. In this way, these individuals are imagined within the confines of their role as objects for visual representation. Their lives as people are pared back to the narrow parameters of how they choose to live as images.

These seven people are left to respond to the unstated prerogatives of an artist whose virtual silence within the written content of the book confers on them responsibility for their unskilled appearance. They are rendered in poorly lit, poorly exposed, technically mediocre images, which only succeed in demonstrating their inexpert grasp of new technology. The only choices declared in the book are those of the individuals who are the subjects of images credited to Hoek as the photographer. Thus, in “addressing us” through a premise constructed so that Hoek might show his new way of seeing black bodies, these individuals take up the centuries-old mantle of the colonial subject responding to white Western preoccupations. And as in so much orientalist imagery, their bodies exist purely to serve.

Pages from New Ways of Photographing the New Masai

There has latterly been a recurrence of pejorative photography of the black body in contemporary photobooks. Such work operates on the implicit premise of the primitivism of the Other, according to which blackness and black bodies are defined by a rudimentary existence in a premodern, mystical world. Such work depends upon this assumption in order to celebrate the vibrancy of African culture, the athleticism of the black body, or to delight in the richness and beauty of black skin. In this way, the black Other serves to alleviate the complexities of modern Western life, by offering an anachronistic alternative to white Western identity.

New Ways of Photographing the New Masai is characteristic of this growing corpus of photographs that portray the black body as “a socius without writing or the Word, history or cultural complexity,” as Hal Foster wrote in his 1985 essay “The ‘Primitive’ Unconscious of Modern Art, or White Skin, Black Masks.” Foster’s essay title underscores the way in which blackness serves as a theatrical mask that conceals a troubled white identity. His essay critiqued the decontextualization necessary to argue for an affinity between ritual tribal objects and the products of modernist art, and argued that the “primitive” is instead made to serve as a phase in the development of properly Western traditions. The primitive serves as a marker of the antiquated, the uncivilized—as a point of abjection against which Western modernity can be mapped and celebrated. Recent instances of such primitivism in contemporary photography tend to depend on the unstated clause of white Western intellectual superiority, as it is contrasted with the inherently retrograde sensuality of the black body. Such work often stresses the earthly, folkloric, and animalistic as inherent virtues of the black body and its attendant “culture,” although any contextualization of such culture is habitually excluded.

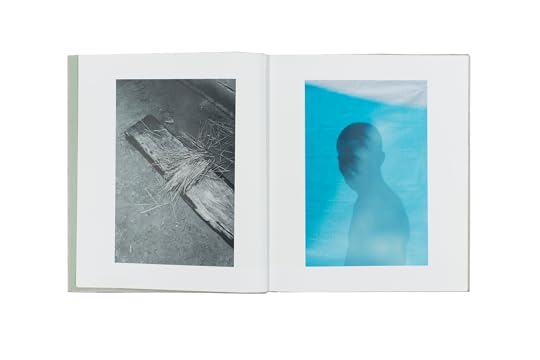

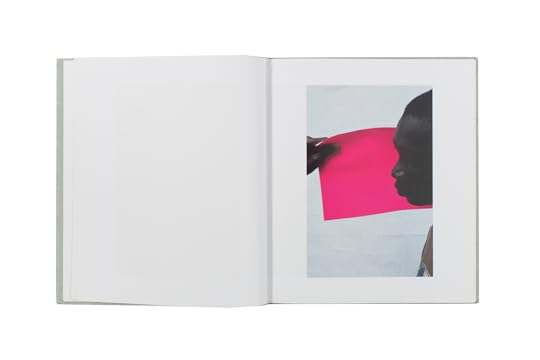

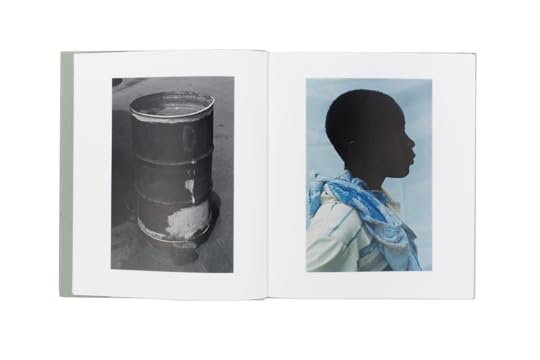

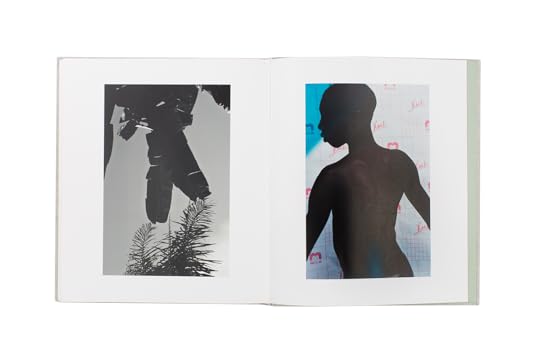

Pages from Viviane Sassen’s Pikin Slee (Prestel, 2014)

These tropes are also apparent in the work of Dutch photographer Viviane Sassen, in books such as Flamboya (contrasto, 2009), Parasomnia (Prestel, 2011), and in her latest Pikin Slee (Prestel, 2014). Made at various points in Africa and across the African diaspora, the black body is repeatedly rendered as an anachronistic contrast to Western norms, whether these are intimated by architecture, by fashion, or by other commonplace commercial goods. Sassen’s photographs are characterized by the solubility of blackness into shadow, or by its vivid difference from garish color. Her portraits incessantly emphasize the black body’s pliability and malleability in a series of strange gestures of physical contortion. In her photographs, the black body is mute, dark, gestural, and inanimate: an object made up exclusively of deep brown and black contours, pools of impenetrable shade, counterpointed by vibrant dollar-store goods, lurid paint, or the patterned effects of light and shadow.

Pages from Pikin Slee

In photographs such as Anansi (2007) or Ivy (2010), supine black bodies fuse together into sculptural oddities that are born out of a soluble relationship to the earth. And yet a certain ironic dissonance is produced by the whiteness of a shirt in shadow, or the presence of England’s Three Lions on a pair of football shorts. The antinomies of blackness and whiteness, of the earthly and the intellectual, the savage and the savior, are here overt structuring elements of the image. But such aesthetic tensions as these contrasts evoke do not trouble a long history of ethnic degradation; they reinforce it as a further instance of the theatrical acquiescence we have come to expect from subservient, primitive blacks.

Pages from Pikin Slee

Sassen’s black bodies are very frequently abstracted into postures that intimate strange bodily rituals, invoking a kind of voodoo ergonomics of spontaneous contortion, and frequently displaying acts of apparently voluntary self-effacement. They are cast as primitives, denuded of any locally specific cultural history. Sassen herself has said in an interview with Planet magazine in 2010:

“I never intend to dismantle misconceptions of the ethnic ‘Other,’ though I like to play with these preconceived ideas people in the West have. I show them things they think they know or they don’t understand (like the paint), and in that way [my photographs] indirectly provoke questions about our Western view of the ethnic ‘Other,’ which is often a very limited view.”

Pages from Pikin Slee

It is apparent from the figurative language of Sassen’s images that she plainly does not seek to “dismantle misconceptions” of the “ethnic Other,” but rather to use the black body as one among many manageable objects in a series of portraits perhaps better understood as still lifes. However, it is extraordinarily difficult to avoid the conclusion that her photographs regurgitate a limited view of alterity, which frames the black body as an object and not as an individual.

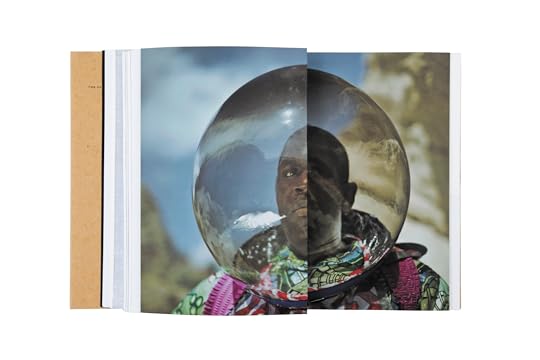

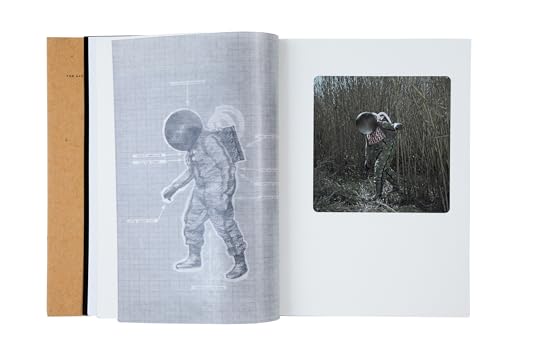

Pages from Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts (self-published, 2012)

Cristina de Middel’s The Afronauts (self-published, 2012) set out to lament “the fact that nobody believes that Africa will ever reach the moon,” by re-staging images derived partly from documents she discovered recording an aborted attempt to launch a Zambian space program in 1964. De Middel’s project was photographed in Spain following her discovery, in 2009, of the story of Edward Makuka Nkoloso, founder and sole member of Zambia’s National Academy of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy. His goal was to launch a woman, two cats, and a missionary to the moon, and then on to Mars.

De Middel’s book relates an approximate version of this story from elements that are sometimes factual but often fictitious, incorporating diagrams and news stories alongside images of “afronauts” in garishly patterned spacesuit costumes sewn by her grandmother. This space program is recreated in the midst of a wild landscape that lacks any traces of aeronautical infrastructure, but contains a strangely pliant elephant. While the photographs delight in a farcical retelling, De Middel’s description for the book on Amazon.com argues that this work contains a “subtle critique” of “our position towards the whole continent and our prejudices.”

Pages from The Afronauts

Ostensibly this is a story about the unbridled ambitions of African people, and about the injustice of their relative lack of freedom in achieving them. The absurd and implausible attempt at space flight depicted in the work underscores a profound disjuncture between Africa and the West. The riches of the slave trade provided the capital for the Industrial Revolution, without which space flight would have remained a pipe dream. The farcical tenor of the The Afronauts acts as a comic reprieve and disguises the formative role of exploitation in the production of poverty on one continent, and unbridled freedom on another.

If the past decade of extraordinary photographic production has demonstrated any one thing in the arts, surely it is the apparently inexhaustible adaptability of the photographic book to contextualize and address the specificity of an artist’s own intentions? In the photobook we have a form capable of embodying, rather than vaguely approximating, the vision of those artists who seek to use it. The recurrence of orientalist work that deals with race and its representation in such a willfully tenuous fashion suggests the spectacle of the primitive is resurgent in contemporary visual culture. This recurrence stands at odds with other meaningful advances in the general discussion around race and politics, but it also highlights the deeply contested and complex nature of the issues at hand. Just as modernity is inseparable from colonial history, so too is the abjection of “primitive” blackness inseparable from white privilege. We would do well to question the contextualization of race in such photographic work, so that we might more clearly see the white skin lurking beneath its black masks.

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa is a photographer, writer, and editor of The Great Leap Sideways where portions of this essay originally appeared. He was an artist-in-residence at Light Work in 2015; has contributed essays to catalogues and monographs by Vanessa Winship, George Georgiou, and Paul Graham; and is a faculty member in the photography department at Purchase College, SUNY.

The post The Lives of Others appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 21, 2015

Hilla Becher (1934–2015)

Portrait of Bernd and Hilla Becher, 1985. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery

By Brian Wallis

When Hilla Becher appeared on stage at the Paris Photo Platform in 2012, the event was something like a coronation. With her silver-bobbed hair and infectious intelligence, she deftly answered questions in precise English, and left to a standing ovation. The public lecture accompanied two exhibitions of work that she and her husband Bernd Becher, who died in 2007, had produced over the past half-century. Her rare public appearance and the twin exhibitions were a reminder of the extraordinary public regard for the Bechers and of their broad impact on postwar art and photography. For this reason, the death on October 10, 2015 of Hilla Becher at age 81 felt not only like a profound loss but also like an abrupt end to a unique way of seeing the world.

Hilla Wobeser was born in 1934 in Potsdam, in what was later East Germany. From the beginning, she was immersed in photography. Her mother was a photographer, as was her uncle, who left a young Hilla his darkroom. After moving to Berlin, Hilla enrolled at Lette-Verein, the technical design school where her mother had also studied. By then she was skilled in operating heavy glass-plate cameras, and in 1951 she secured an apprenticeship with the conservative Berlin photographer Walter Eichgrun. Later, while working in advertising photography in Düsseldorf in 1957, Hilla met Bernd Becher, who was then a student at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. The following year, Hilla also enrolled in the Kunstakademie and they began working together. They married in 1961.

In 1957, Bernd and Hilla Becher launched a campaign to document the anonymous and often-disused manufacturing and domestic buildings they encountered in the abandoned wasteland of postindustrial Europe. Starting with the mining and steel-producing region around Siegen, Bernd’s hometown, and radiating out through the Ruhr Valley, the Bechers discovered an extraordinary proliferation of unique, anonymously designed vernacular structures in plain sight. In the coal-mining regions of England, France, Belgium, Italy, and ultimately the United States, the Bechers later photographed an encyclopedic range of industrial architectural forms, taking care to honor the generic categories while recording the subtle differences and the often idiosyncratic variations invented by local builders. In 1966 alone, the Bechers traveled for six months through England and Wales, visiting coal mining regions and industrial revolution relics around Manchester, Sheffield, and Nottingham. They were industrial archeologists, meticulously recording blast furnaces, lime kilns, cooling towers, water towers, gasometers, silos, factory buildings, timber-frame houses, pit winding towers, and coal tipples.

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Typology of Slate and Framework Houses (diptych), 2011 © Bernd and Hilla Becher. Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery

Working methodically, the itinerant Bechers followed a very deliberate practice depicting these architectural forms and complexes, producing sequences of separate photographs that looked at individual structures from every side, as well the surrounding natural and manmade contexts, though never showing workers or any other people. They derived inspiration from the precisionist approach of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) photographers August Sander, Karl Blossfeldt, and Albert Renger-Patzch of the 1920s, and utilizing a bulky large-format camera on a tripod, the Bechers photographed the specific character of each example of a type of construction as scientifically as possible. Every building was framed in exactly the same way: frontally, in isolation, from a reasonable distance, against a gray overcast sky.

Relating similar buildings according to their structural forms and original purposes, the Bechers created a vast taxonomy of modern architectural types facing eradication. “We didn’t really see it as artists, we saw it as something like natural history,” Hilla Becher noted in 2012. “So we also used the methods of natural history books, like comparing things, having the same species in different versions.” The Bechers exhibited these images in large, strictly ordered grids of nine, twelve, or sixteen photographs of nearly identical structures. They called these grids “typologies.” “The Typology is nothing but comparing and giving it a shape, giving it some sort of possibility to be looked at,” Hilla Becher said. “Otherwise, it would just be heaps of paper.” For the Bechers, these typologies were conceptual categories based on the general ideas used to sort a large body of information. For the rest of the world, the typologies were a revelation. Their structuralist approach and their interest in ordered sets and serial presentations were unusual in photography at the time; as a consequence, the Bechers often presented their work elsewhere, in austere Conceptual Art publications and exhibitions rather than the contexts of photography or architecture.

Bernd and Hilla Becher, New York Water Towers, 2003, © Bernd and Hilla Becher. Courtesy of Sonnabend Gallery.

Among the first to recognize the artistic significance of these typologies was American Minimal artist Carl Andre, who wrote in Artforum in 1972: “A partial catalogue of the typological subjects of Bernd and Hilla Becher includes: structures with the same function (all water towers); structures with the same function, but with different shapes (spherical, cylindrical, and conical water towers); structures with the same function and shape, but built with different materials (steel, cement, wood, brick, or some combination, such as wood and steel); structures with the same function, shape, and materials; comparative perspective views of ore and coal preparation plants; comparative frontal views of pithead towers; comparative and perspective views of pithead towers, high tension electrical pylons, blast furnaces, and factory buildings.” Andre’s straightforward listing conformed to his own rejection of narrative and style and his preference for neutral systemic or serial practices. Such an approach had long been advocated by the Bechers, who in 1970 called their first book on vernacular architecture Anonymous Sculptures and who eagerly participated in Conceptual and Minimal Art exhibitions. The photographs by the Bechers, and the artists surrounding them, were critical statements, which in part challenged the normative ideals of the postindustrial American culture of the 1960s and its emphasis on bland repetition and mechanical reproducibility.

Today, the influence of the Bechers is everywhere: in the widespread contemporary tendency toward serial documentary photography and in many artists’ interest in creating typologies or archival sequences of photographs. And, of course, they mentored a generation of students—the so-called Becher School—at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1976 to 1996. Among the students who assimilated the Bechers’ approach but often produced very different, large-scale color photographs in series were Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, Caio Resiewitz, and Elger Esser. Yet, despite this cadre of followers and the many accolades at Paris Photo and elsewhere, Bernd and Hilla Becher were outliers. They were uninterested in prevailing trends in art and photography, but offered instead a model for disciplined living and seeing. For five decades they pursued their singular project with astonishing tenacity and rigor, adhering to two simple guidelines: to record with exacting fidelity specific overlooked elements of everyday life and to organize that potentially ephemeral information into a form that creates new meaning. In essence, fleeting time was their subject, and photography allowed them to rescue sights that time has by now eradicated. In their elegant typologies, the blueprint of their attitude toward life endures.

Brian Wallis is the former Director of Exhibitions and Chief Curator of the International Center of Photography in New York.

The post Hilla Becher (1934–2015) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

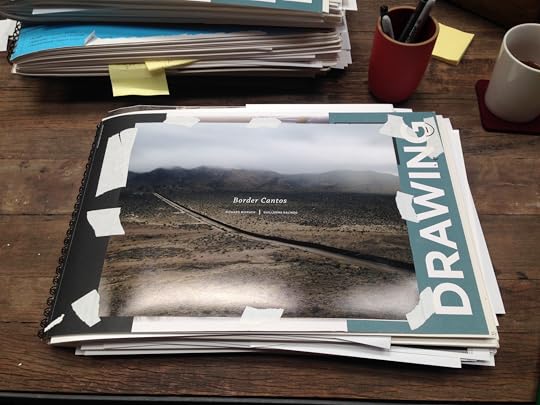

Richard Misrach on Border Cantos

In early 2016, Aperture will release the latest addition to Richard Misrach’s ongoing Desert Cantos series: an examination of the U.S.–Mexico border that is both document and interpretation, a collaborative undertaking with composer Guillermo Galindo. Misrach stopped by Aperture to finalize critical details of the book.

Richard Misrach visits the Aperture offices for a presentation of work that will appear in Border Cantos. Photograph by Max Mikulecky.

After his presentation, Misrach held a book signing at Aperture Gallery. Photograph by Max Mikelucky.

Misrach’s studio serves as a staging ground for image grids, Galindo’s instruments, and other works in process, April 2015

Richard Misrach, in his studio, showcases a draft of one of Guillermo Galindo’s graphic scores, April 2015

A grid of Misrach’s photographs of artifacts found along the U.S.-Mexico border, and in the foreground, one of Galindo’s instruments created from bullet casings found at Border Patrol shooting ranges, April 2015

Border Cantos in raw dummy form. The first dummy initially filled three sketchbooks, April 2015.

Reviewing first proofs of Border Cantos at Aperture with production expert, Matt Harvey, September 2015

By the Editors

In the early days of a presidential campaign in which immigration is a heated issue, and on the heels of Pope Francis’s U.S. visit in September—when he urged Congress to show compassion toward those who “travel north in search of a better life,”—Richard Misrach visited the Aperture Foundation to scrutinize the design and production details for his forthcoming book, Border Cantos. This project focuses on the U.S.–Mexico border and has been developed over several years in close collaboration with the Mexican American composer Guillermo Galindo. In between looking at color proofs and signing copies of his last Aperture publication, The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings, Misrach gave a presentation in which he walked the Aperture staff through the layout of the book-in-progress. The book will accompany a traveling exhibition of the work, opening at the San Jose Museum of Art in February 2016. The exhibition will also include handcrafted instruments created by Galindo out of discarded materials Misrach collected from the border.

Since 1979, Misrach has worked on his Desert Cantos series, exploring unseen aspects of the American West, specifically its vast deserts. His Border Cantos project specifically focuses on the narrow strip of land where hundreds of people die each year attempting to cross into the U.S. from Mexico, which Misrach called “a huge humanitarian disaster every day.” He explained how most of what he saw was surprising and goes mostly unreported: unexplained scarecrow-like sculptures made in the desert, water stations set up by humanitarian-aid groups, ephemera left strewn across the desert during various crossings. Misrach began to collaborate with Galindo to create a score for a series of compositions intended to be performed entirely on handmade instruments made out of what Misrach picked up along the border, including, in one case, a piece of the border wall itself. Despite the border’s divisive, prominent place in the current political conversation, Misrach emphasized the unseen stories behind the policy—one he believes will be widely regretted in years to come. “There’s all this activity no one knows about,” he said, of the photographs that will make up Border Cantos.

The above slide show includes images from Misrach’s visit and from the project in various stages of development.

Tap here to find The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Richard Misrach on Border Cantos appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers