Aperture's Blog, page 151

October 8, 2015

Archive: A Look Back at Aperture Magazine’s Fortieth Anniversary

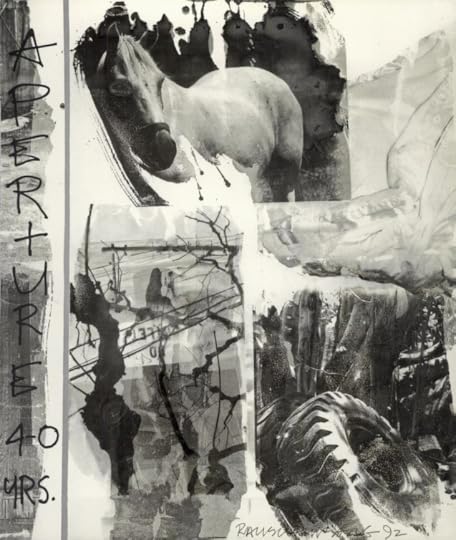

The fall 1992 issue of Aperture magazine featured an original Robert Rauschenberg cover for the magazine’s fortieth anniversary. Inside, photographer Robert Adams interviewed Michael E. Hoffman (1942–2001), who built Aperture into a book publishing program, acted as publisher and editor of the magazine, and was the longtime director, from the 1960s through the 1990s. On the occasion of the launch of the Aperture Digital Archive, making every issue of Aperture magazine available online, appears this excerpt from that conversation, in which Hoffman speaks candidly about the early days with Minor White and Paul Strand, and about the development of Aperture.

Cover of Aperture Issue 129, with cover art by Robert Rauschenberg.

Robert Adams: In the first issue of the first volume of the magazine, in an opening statement about Aperture which is signed by [Minor] White and [Dorothea] Lange and all the rest, there is the following: “Aperture is intended to be a mature journal in which photographers can talk straight to each other.” In the early issues, there is in fact a striking and exciting willingness by photographers and writers to address fundamental issues in clear language, issues like “What are we doing?” and “What is it good for?” Do you have the sense that this directness is harder to come by now? And if so, why? And do you think there is any way around the increased academicization of photography?

Michael E. Hoffman: Think of Nancy Newhall. She was writing in a highly experiential, charged style. When you were near her and she was talking about photography and photographers, she vibrated. She was passionate. She was an intelligent, well-educated person who wrote beautifully.

I think at that time photography was life itself for people like her. They were in a process of discovery that was enormously exciting. There was no monetary support, there was no real outside interest. They were very much on their own.

What has happened today is that the academic side has overwhelmed the experiential side. A great many people have become interested in photography, but without bringing to it the qualities of engagement that force one to ask those primary questions. Instead, we get questions about style, and we get art-speak. . . . .

RA: Where and when did you first meet Minor White? And as you came to know him, what was it that most convinced you to shape your own life as you have—you’ve been working with Aperture since 1964. Was it his manner, or what he said, or his pictures, or all of this together?

MEH: I had been given a subscription to Aperture in 1957, when I was fifteen years old. At first, the magazine had no effect on me. Then, all of a sudden, one day I sat down to look at it, and three hours later I came back changed. I had never had such an experience of total immersion. It was the issue that Nancy Newhall had done on Edward Weston, at Weston’s death, called “The Flame of Recognition.”

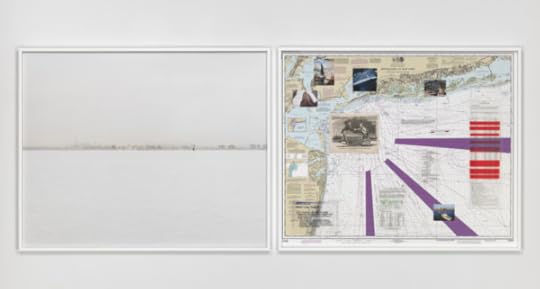

Pages from Issue 129 of Aperture.

RA: Had you yourself been photographing?

MEH: Yes. I had been taking pictures for about seven years. As a result of my Aperture subscription, I received a notice that Minor White was giving a workshop in Denver. I had just come back from college, and I said to myself, “This is something I could do.”

When I arrived at the workshop, I found it to be quite a bohemian setting. In the room there was a tall man with a beard, rather handsome, rather formidable—and I was sure that he had to be Minor White. To the right of the door there was another man with an open white shirt and some loose-fitting trousers. He had one leg up against the wall, and I think he was wearing sandals. I said to myself, “I wish this man would leave as soon as possible, because what the hell is he standing around here for? Why not get on with this important undertaking?” Of course, the man in the white shirt was Minor White.

I had never encountered a presence like his, somebody who was so unassuming, who had a relaxed, gracious manner, who was incredibly accepting of the people in the workshop, and who appeared to radiate a quality of light. Minor had a rather deep voice and a great presence. He gave us assignments that embarrassed me: we were to stand out on a street corner, for example, and let all the traffic and the people just go by. Just stand there. A lot of what we did, I only later came to understand, were the kinds of exercises that certain religious communities utilize to train people to become more aware, more present.

At one point we even went out to a garbage dump to start photographing. I thought, this is the limit, this is the end. I was going to give it up right there, and then things began to transform themselves before my eyes. I was astonished. We processed and printed every day, and then we had sessions so that we could look at what other people were doing. It was an intensification of what I had experienced with Weston’s “Flame of Recognition.” The search seemed somehow to give life real meaning, and Minor was both a guide and an ally.

RA: How did you then get to know White better?

MEH: Well, I tried to suggest to him that I could be helpful in the workshops that he was doing in the East. I was fishing, trying to find something. He was not very open to working with anybody. He was a very private person. In any event, he did agree to let me set up a workshop at the Millbrook School, a secondary boarding school I had attended. This was very successful, and so he agreed to give a workshop at St. Lawrence University. And then, in 1964, when I graduated, he invited me to Rochester to work with him personally, which I considered a great opportunity.

Aperture had gone out of existence in early 1964, and I said to Minor that I thought it should continue. And then I met Nancy Newhall, who was very supportive, although I suspect that Minor really didn’t want to see Aperture continue.

Pages from Issue 129 of Aperture.

RA: Why was that?

MEH: He felt that he had done everything that needed doing. Aperture‘s lifetime, then, was almost equal to the span of time during which Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work was published—Minor felt a very great connection with Stieglitz—and he thought Aperture had come to its natural end. He also was tired of the personal attacks, the lack of support, and the isolation. He had worked without any monetary compensation. He had devoted twelve years to the magazine, and had no money except what he earned as a part-time instructor. Minor eventually agreed, and Nancy and I decided we would do an issue on Weston, because the 1958 “Flame of Recognition” issue had reached only a few people. We decided to redo it simultaneously as a book and as the first new issue of the magazine, which had been dormant for almost a year. We had no money at all, and for a number of years I received no compensation. . . .

RA: Why don’t we talk for a little about Aperture the magazine as it has evolved since White gave up his guidance of it. In recent years, there has been a shift away from issues of mixed content to issues that focus on a particular theme, and some people—I think particularly photographers—have found that the results are often less interesting to them. They point out that the thematic issues sometimes seem to begin from an idea rather than from pictures in hand, and thus, perhaps inevitably, are not as exciting visually. Photographers also would suggest, I think, that these thematic issues have tended to discourage submissions of general portfolios. This may in turn be why the magazine doesn’t seem to have as many wonderful, anomalous shots, sometimes by unknown photographers, which made some of the earlier issues of the magazine so exciting. I am interested to know how you see the pros and cons of running a schedule of thematic issues, and interested to know if the practice is one that you think is valuable enough to continue.

MEH: Well, to begin with, I think the theme idea was a predominant mode in Minor’s approach to the issues in the early years. As Aperture evolved, and because of the editors—Carole Kismaric, Larry Frascella, Mark Holborn, Nan Richardson, Chuck Hagen, all of whom are very talented, as is our current group: Rebecca Busselle, Melissa Harris, and Andrew Wilkes—there was a desire to create a more coherent framework. I think it was a reaction to the portfolio approach, which seemed quite uncreative. There was no sense of a larger vision, a larger idea with which the pictures had to interrelate, by which they had to be challenged. I think that there was a desire among the editors to touch on ideas beyond those possible in a portfolio approach. In other words, larger ideas into which photography could focus and give a larger meaning, gain a larger meaning. . . .

RA: How does an issue originate? For example, does the idea usually come from in-house? And then what is the editorial process that leads to the choice of an issue’s theme?

MEH: We wrestle with that question all the time. We’ve been blessed over the years in having some very creative people involved with Aperture, all with very different views.

Chuck Hagen, for instance, wanted to do a show called “Drawing and Photography.” And he was deeply committed to the idea of doing this as an issue of the magazine as well. I think it was a marvelous exploration. It was really a chance to explore the medium in a broad variety of ways. Four issues before that, Melissa Harris did “The Body in Question.” In between, Andrew Wilkes edited “The Idealizing Vision,” on fashion photography; then there was the issue on German photography, and “Connoisseurs and Collections.” These were very diverse, equally valid approaches to photography and the magazine.

The hope is that in four issues we are able to cover enough ground and to include enough photographers to satisfy the need for people to be shown. But we really rely on the creative juices of the editors. We just did an issue called “Our Town,” which includes photographs by a broad variety of remarkable photographers, many of whom are not known, and marvelous texts by David Byrne, Richard Ford, Michele Wallace, Gary Indiana, John Waters, Marianne Wiggins, and others. We hope that this is a way to engage photographers, but also to achieve a broad cultural reach. We try to bring in a variety of forces of our time.

Click here to find the Aperture Digital Archive on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Archive: A Look Back at Aperture Magazine’s Fortieth Anniversary appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 7, 2015

“Breaking the Light Barrier” Workshop at Aperture Gallery

Attendees of "Breaking the Light Barrier" set up a shot. Photograph by Becca Imrich

Image courtesy of Juliana Tan, 2015.

Image courtesy of Joan Lobis Brown, 2015. Two lights and filters inside the lamps were used to simulate ambient light from a television.

Image courtesy of Dale May, 2015. A combination of six lights and various filters on the windows were used to transform day to night.

By Becca Imrich

Rick Sands’s Aperture workshop “Breaking the Light Barrier,” created for photographers who want to master lighting techniques, took place at Aperture Gallery from August 29 to September 3. Aperture workshops bring students, professionals, and amateurs together with leading photographers working in a variety of fields and genres for intensive educational experiences. The next workshop at Aperture is “Mark Klett: Traveling the Devil’s Highway—Exploring the Borderlands of the Sonoran Desert, Arizona.”

Over the course of six days, workshop participants collaborated with master illuminator Rick Sands to learn how to see, understand, and realize various lighting scenarios. For nearly fifteen years, Sands, a film technician, has created elaborate lighting for the narrative photographs of artist Gregory Crewdson. His portfolio also includes thirty-five theatrically released motion pictures with directors such as Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola, forty-seven television movies, and countless one-hour television episodes. The class worked under a wide range of conditions (day as well as night, interior as well as exterior), and studied separation through use of contrast via intensity and color. Sands discussed philosophies of lighting techniques and shared his insight on the five properties of light, and how they interrelate: quality, quantity, color, shape, and direction.

The workshop was a mixture of lighting theory and hands-on practical exercises. Aperture’s Chelsea gallery was turned into a studio for participants in which they could arrange various lighting scenarios. On the second day of the workshop students were challenged to recreate a scene with complex lighting. Each participant brought in found images and worked in teams to reproduce the lighting set-up while employing techniques discussed the previous day. Some Aperture staff served as models; in the slideshow above, look out for examples of student work from the workshop and see how the gallery was transformed.

Click here to learn more about Aperture Workshops.

The post “Breaking the Light Barrier” Workshop at Aperture Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 1, 2015

Pacifico Silano, Light Work Artist-in-Residence

Pacifico Silano, 2013 Portfolio Prize runner-up to participate in 2016 Light Work’s Artists-in-Residence Program.

The post Pacifico Silano, Light Work Artist-in-Residence appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize Now Open!

Submit your portfolio for Aperture’s editorial staff to review. The deadline is December 2, 2015 at 12 noon EST. More details here.

The post 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize Now Open! appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Drew Nikonowicz, Medium Photography Festival Lecture

Drew Nikonowicz, winner of the 2015 Portfolio Prize will present a lecture at the 4th annual Medium Festival of Photography.

The post Drew Nikonowicz, Medium Photography Festival Lecture appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Trevor Paglen at Metro Pictures

Trevor Paglen’s new exhibition at Metro Pictures focuses on the unseen images of the Internet: the deep-sea cables that connect massive amounts of data across the globe, and now serve as vulnerable points in cyber warfare. Writer Genevieve Allison considers the effect of our viewing such obscured sites of power in Paglen’s latest series. This article first appeared in Issue 16 of the Aperture Photography App.

Trevor Paglen, Installation view, 2015. Metro Pictures, New York.

By Genevieve Allison

Paranoia has never been far from the causation of war, but as the nature of material reality becomes increasingly virtual, such fears have also become part of its mechanization. And perhaps most central to these transformations is the appropriation of the Internet as an instrument of mass surveillance. In his second exhibition at Metro Pictures, Trevor Paglen delves into the subject of the Internet’s physical geography as well as vulnerability. He looks at where it sits on the earth’s surface, what is its otherwise faceless architecture: vast networks of transoceanic fiber-optic cables laid on the seabed, carrying telecommunication signals between the world’s continents.

Trevor Paglen, Installation view, 2015. Metro Pictures, New York.

Throughout his many careers—as photographer, fine artist, geographer, author, and independent scholar—Paglen has pursued questions about regulatory prerogative as it relates to surveillance and security, and how these forces shape the public domain and the production of public space, whether mapped, imagined or virtualized. Previous work has investigated, in publication form, the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program (Torture Taxi, 2006) and military iconography (I could tell you but then you would have to be destroyed by me, 2008) but is best recognized through his ethereal photographs of celestial fields and classified landscapes—sublime images informed by the artist’s empirical observation of covert activity. In this latest body of work, Paglen documents and charts the location of major submarine cables, illustrating global data communication in concrete terms rather than through abstract and popularly constructed metaphors like the cloud, the Web, or cyberspace. The real subject, however, is how these sites are targeted and accessed by national security agencies.

Trevor Paglen, Columbus III, NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean, 2015

A dual-channel video installation of material Paglen filmed for Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’s Oscar-winning film about Edward Snowden, is the focal point of the exhibition, consisting of a series of photographs, charts, and several sculptures. Throughout the twenty-four minutes of Eighty Nine Landscapes (2015), lonely seascapes, and countrysides unfold with slow, haunting beauty. The video presents locations where main arterial transoceanic cables connect to the continental shelf. More specifically, these “choke points” are where the U.S. government’s National Security Agency (NSA) has installed onshore surveillance utilities to tap information as the cables reach landfall. As the scenery shifts from rolling green hills to windswept coastal expanses, land-based surveillance stations come in and out of view. Their presence—remote, surreal, and unnatural in these picturesque landscapes—are ominous signs of real-world manifestations of virtual activity. It might have once been an abstract, infinitely nebulous space of interpretation, but since the Edward Snowden leaks, the underlying fragility and weaponization of global communication has been exposed and deeply questioned—along with the spying, sabotage, and malware waged through it, outside of public visibility.

Trevor Paglen, Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1), NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean, 2015

A series of large-format C-prints of the submerged cables offer another meticulously staked-out vantage point, which Paglen was able to explore after learning to dive and conducting extensive research and fieldwork. The resulting images seem more like inky color-field explorations into aquatic green than surveys of any geographic import, but their titles give reference to their location and significance—photographs such as Globenet NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable Atlantic Ocean, 2015, and Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1)NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean, 2015. The images trace the obscured existence of this extreme feat of engineering on the seafloor and bring to bear a parallel between perhaps humanity’s greatest achievement and its least explored frontier. The seductive images may seem at a far remove from what we think of as anything resembling conflict photography, but they appeal to its key critical discourses: to illustrate the nature of conflict, and to study its darkest values via an impulse toward aestheticization.

Trevor Paglen, NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, New York City, New York, United States, 2015. All images courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Trevor Paglen is on view at Metro Pictures in New York from September 10 to October 24.

The post Trevor Paglen at Metro Pictures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 29, 2015

An Interview with Ishiuchi Miyako

Through her images of subjects ranging from the American Occupation of Japan and the bombing of Hiroshima, to women’s scarred bodies and her mother’s and Frida Kahlo’s personal effects, Ishiuchi Miyako, born in 1947, has explored the passage of time and history. Like Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama, renowned Japanese photographers who emerged in the 1950s and ’60s, Ishiuchi’s early work has been shaped by the residual presence of

World War II. Her first series, Yokosuka Story (1976–77), focused on her coastal hometown, the site of a U.S. naval base that was permeated by American culture. Projects that closely followed—Apartment (1977–78), which explored the interiors of Tokyo’s postwar housing, and Endless Night (1978–80), for which she photographed brothels—honed Ishiuchi’s vision as well as her process; for her, the image is a physical object made by hand in the darkroom.

For more recent work such as Mother’s (2000–2005), featured at the 2005 Venice Biennale; ひろしま / Hiroshima (2007); and Frida (2013), Ishiuchi turned to color, taking a forensic approach to examine clothing and objects laden with complex histories, underscoring the idea that the traces of time’s passage are her true subjects. Last year, Ishiuchi won the prestigious Hasselblad Award, and, on October 6, a major exhibition of her work, Postwar Shadows, will open at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In this excerpt from the Fall 2015 “Interview Issue” of Aperture magazine, Yuri Mitsuda, curator at the Kawamura Memorial DIC Museum of Art, speaks with Ishiuchi about the evolution of her explorations of time and how she has negotiated a field dominated by men.

Yokosuka Story #58, 1976–77

Yuri Mitsuda: Were you ever excluded because you were a woman?

Ishiuchi Miyako: Not at all. I mean, Tomatsu loved women. Moriyama too. So there were always women around. I had no interest in them that way, though, as men. There wasn’t one guy who was my type among all those photography guys. Thank goodness. But it can be an ordeal, being a woman. People constantly accosting you. I watched it happen all around me. There were a lot of women who wanted to do something in photography, and one after another I saw their efforts come to nothing.

Yokosuka Story #98, 1976–77

YM: Why do you think that was?

IM: They underestimated how hard it would be. In my case, I thought I would do Yokosuka Story and then quit. Like I was getting back at an enemy. Yokosuka was a difficult place for a woman because of the sexual violence that occurred there. Rape was a part of daily life, but nobody saw it as a crime. I did not experience rape myself, but it scarred me. I’m gonna kill you once and for all; that was the feeling. That city, Yokosuka, it had inflicted so much on me, so much trauma, so many scars. If I don’t kill you I can’t move on—that was the feeling I had.

You had to have that kind of intense feeling. I thought I’d do it once and be done, but of course, I ended up continuing. I looked around and thought, Well, now I’ll do Hyakka Ryoran (A hundred flowers bloom, 1976).

Endless Night #71, 1978–80

YM: Hyakka Ryoran was an all-woman show you planned for Shimizu Gallery, wasn’t it? So you had the sense that you needed to do things as just women, as women photographers.

IM: Of course I did. We wanted to do something just for women, but separate from the women’s lib movement. The mainstream world of Japanese photography was absolutely a boys’ club. People outside Japan noticed it too, and they were right. I had no interest in them, at all. The workshop group was a boys’ club, too, of course, but the form it took was different. They were interesting, at least, Tomatsu and all those guys. They were fun to hang around with. We went out drinking every week on the Shinjuku Golden Street. We had fun drinking

together. I got my share of sexual harassment, of course. They were old-school guys, after all. It sounds idiotic saying it like that now, but that’s how it was.

YM: The excess energy produced by artists, by people engaged in making things—it doesn’t always lead to the most moral conduct.

IM: And there were plenty of people who left themselves vulnerable. But never me. I got a reputation as pigheaded, a dragon lady. But I stuck to my guns.

Mother’s #3, 2000

YM: If you didn’t, it would come to nothing.

IM: They’ll undermine you, drag you down.

YM: Do you mean how Hyakka Ryoran was thought of as unsuccessful?

IM: No, it was just completely ignored. There’s hardly any record that it happened at all. The only attention it got was in [the tabloid] Heibon Punch. They wrote about women taking pictures of men, of women making men strip naked. So that got picked up on television, as a kind of scandal.

Apartment #14, 1977–78

YM: At the time, Diane Arbus was getting a lot of attention as a female photographer.

IM: But I didn’t have a lot of interest in her. She was a special case, though. Arbus wasn’t popular as a woman; she was popular as an American.

Frida by Ishiuchi #50, 2012

YM: These past ten years you’ve exhibited more and more outside Japan. Do you think that’s expanded your view on things? Were there things you encountered that surprised you?

IM: I was surprised by the Hasselblad Award. I was even more surprised to learn that they knew everything about me—they had all the data, right at their fingertips!

These days, I have many more opportunities to show outside, rather than in Japan. And I find that the respect people have for photography [in the West] is different. Photographers are artists. In Japan, a photographer is just a photographer. No one thinks of photographers as artists in Japan.

ひろしま/Hiroshima #69 (Donor: Abe, H.), 2007. All photographs © Ishiuchi Miyako and courtesy The Third Gallery Aya, Osaka, and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London

YM: There’s a history of Japanese photographers saying things like, “I’m no artist; I’m just a photographer.” Especially photographers who specialize in street shots, in Ihei Kimura–style documentary photography. There’s a tendency to want to minimize the role of art, to rebel against the legacy of fine-art photography. That was the basis, or history, on which much of Japanese photography was formed.

IM: Of course. And I don’t care about definitions of art, about what art is or isn’t. All I’m doing is what I feel I must do, regardless of any label.

Frida by Ishiuchi #86, 2012

YM: All the shows you’re putting on, all the books you’re writing: your sixties have been kind of a turning point, haven’t they? How do you feel now, looking back over them?

IM: I’ve had free time up until now. Everyone else has been so busy, but I’ve had the freedom to do things. So I pushed myself past my limits, to do more than I really am able to. Or rather, to do everything I am able to. I know what I can’t do, so I only do what I know I can. I’ve started to think lately that perhaps I really am suited to photography. That’s the potential of photography, to be freer and freer, to do things with ever more freedom.

Translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom.

Click here to find the complete interview from Aperture magazine on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post An Interview with Ishiuchi Miyako appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 27, 2015

John Gossage: Photographs in Books, the Complete Story

John Gossage from pomodori a grappolo (2015)

Join John Gossage the do-it-all photographer, book designer, production manager, and publisher for a two-day workshop that will guide participants through the process of producing a photobook, from conception to completion. Students will learn how to navigate various decisions, ranging from creative, aesthetic choices to budgetary options, while developing a photographic project into book form. Gossage will present an overview of the photobook-making process and lead conversations about specific books brought in by the participants. He will then review each participant’s proposed book project while engaging the group in discussion.

Gossage will be joined by Aperture’s senior editor, Denise Wolff, for a conversation about how Aperture develops its publications and how its editors work with photographers. A few other special guests will stop by throughout the weekend to share their insights on photobook-making. Working step-by-step through the process of creation, with personalized advice, each participant will come closer to finalizing his or her photobook.

Participants are required to bring a proposed book project at any stage of completion, from a group of pictures to a completed mock-up, as well as a photobook they admire to share with the group for discussion. Lunch and light refreshments will be served both days.

John Gossage was born in New York in 1946 and is based in Washington, D.C. His photographs have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions over the past forty-five years. His many one-person exhibitions have included The Better Neighborhoods of Greater Washington, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1976; Gardens, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1978; Photographs of Berlin, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1989; LAMF, Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Germany, 1990; One Work in 39 Parts, Saint Louis Art Museum, 1994; There and Gone, Sprengel Museum, Hannover, 1998; The Romance Industry, Comune di Venezia, Venice, 2003; Berlin in the Time of the Wall, Galerie Zulauf, Freinsheim, Germany, 2005; and The Pond, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., 2011. An exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago is currently in preparation.

Gossage is regarded as one of the finest American photobook-makers of the last forty years. In 2010, Aperture reissued his monograph The Pond (1985) in a twenty-fifth-anniversary edition. Gossage’s other notable works include Stadt Des Schwarz (1987); LAMF (1987); There and Gone (1997); The Things That Animals Care About (1998); Hey Fuckface (2000); Snake Eyes (2002); Berlin in the Time of the Wall (2004); Putting Back the Wall (2007); The Secrets of Real Estate (2008); The Thirty-Two Inch Ruler/Map of Babylon (2010); and pomodori a grappolo (2015).

In 2002, Gossage started his own publishing company, Loosestrife Editions. He is represented by the Stephen Daiter Gallery in Chicago, and his work is included in major public and private collections.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Registration ends Monday, November 29

Register here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post John Gossage: Photographs in Books, the Complete Story appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 25, 2015

Issue 16 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 16:

● An excerpt of Ishiuchi Miyako’s talk with Yuri Mitsuda from “The Interview Issue” of Aperture magazine

● A look back at Aperture magazine’s Fortieth Anniversary issue with an excerpted interview with Michael E. Hoffman

● A preview of images from Rochester 585/716: A Postcard from America Project

● A look inside Rick Sands’s recent Aperture workshop “Breaking the Light Barrier”

● A review of Trevor Paglen’s newest exhibition at Metro Pictures Gallery

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 16 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 24, 2015

A Look Inside the Aperture Digital Archive

The Aperture Digital Archive includes every issue of Aperture magazine since 1952, including rare, early editions. Over 15,000 images, from 220 issues of the magazine, will be searchable by photographer, genre, and decade.

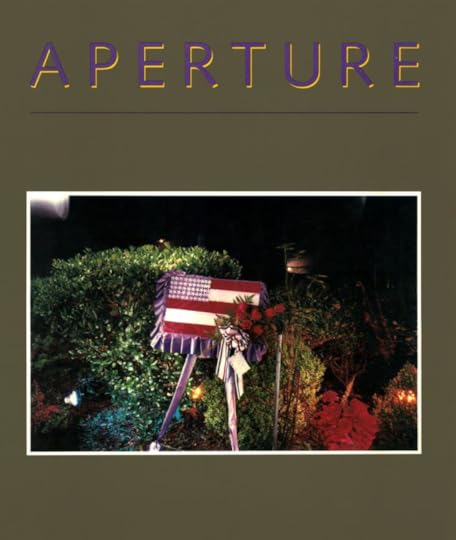

The redesigned Aperture magazine appeared in Spring 2013, with a cover by Christopher Williams.

2014, issue 216: Photographers Inez & Vinoodh guest edit "Fashion" issue

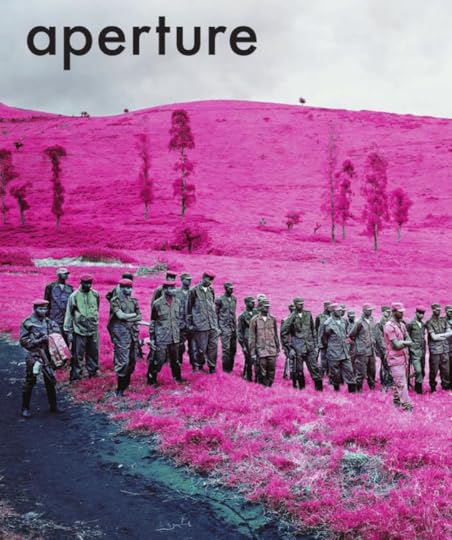

2011, Issue 203: Richard Mosse’s Congo work is featured in the magazine and on the cover; this same series is later published in a best-selling Aperture book.

1992, Issue 129: Special fortieth anniversary issue. Seventy photographers who had appeared in the pages of the magazine were asked to select three photographs, and one image from each artist is chosen for publication. Because no single image could represent forty years, Robert Rauschenberg—whose vast talents included collage—is asked to create a cover that would visually and metaphorically give a sense of Aperture.

1984, Issue 96: previously unpublished work from William Eggleston forms the basis for an entire issue devoted to color photography, which also includes portfolios from William

1975, vol. 19, no. 4: Helen Levitt’s New York City street photography is the first four-color portfolio to be published in Aperture.

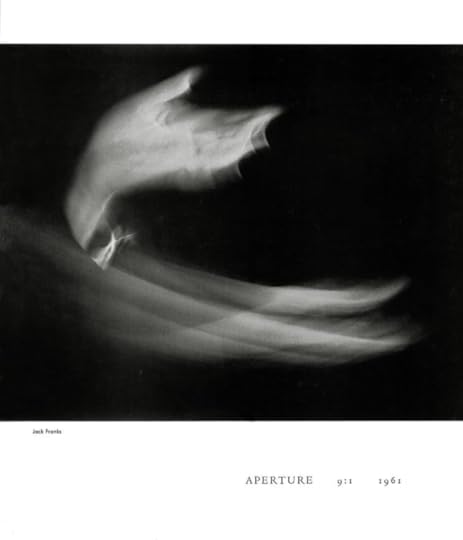

1961, vol. 9, no. 2 included photographs by Robert Frank from The Americans and Pull My Daisy

Paul Strand’s “Letters from France and Italy” correspondence and selected images first appeared in 1953, vol. 2, no. 2

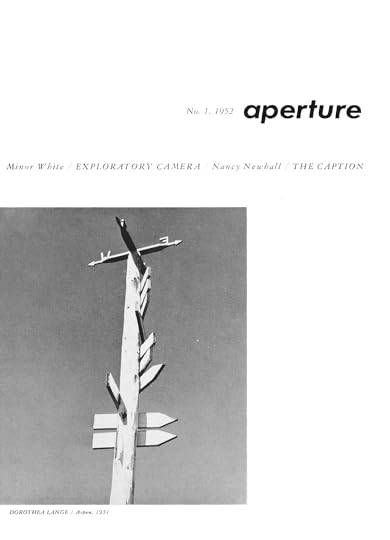

The first issue of Aperture magazine.

On September 10, 2015, Aperture Foundation launched a fully searchable online resource containing every issue of Aperture magazine since its founding in 1952, called the Aperture Digital Archive. From their desktops, laptops, tablets, or mobile devices, users will be able to access all 220 issues of the magazine, including groundbreaking issues such as “Edward Weston: Flame of Recognition,” “French Primitive Photography,” “Black Sun: The Eyes of Four,” and “Queer.” The archive brings together images and personal stories of hundreds of photographers, including Berenice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, Paul Strand, and more, alongside authoritative voices on photography through six decades, including Robert Adams, Peter C. Bunnell, Nancy Newhall, Fred Ritchin, John Szarkowski, and Minor White as well as critics whose perspectives provided new visions of photography, including Charles Bowden, Geoff Dyer, Neil LaBute, Janet Malcolm, Greil Marcus, and Francine Prose.

“Aperture is a document of great artistic, cultural, and scholarly value,” says Dana Triwush, the publisher, “and the archive is designed as a dynamic, interactive tool in keeping with the high standard of content and image quality for which the magazine is known.”

Aperture Foundation partnered with Bondi, a New York-based technology and creative services company whose platform powers the online archives of many top magazines. The Bondi platform presents every back issue as a full digital replica—preserving the magazine’s award-winning design—with every article and image indexed individually. The foundation has also partnered with JSTOR and ProQuest to bring the Aperture Digital Archive to college and university campuses around the world.

Look out for more writings in this tab about Aperture magazine’s archives from prominent voices in the photography world.

Click here to find the Aperture Digital Archive on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post A Look Inside the Aperture Digital Archive appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers