Aperture's Blog, page 154

August 31, 2015

An Archival Interview with Richard Misrach

The following interview was edited from a tape-recorded conversation between Aperture Foundation editor-in-chief Melissa Harris and Richard Misrach at his California studio in March 1992 and appeared in the book Violent Legacies (1992), which includes three “cantos” in his series of photographs that explore the American West. This spring, Aperture released Misrach’s The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings in which the photographer focuses on the gestures and expressions of faraway bathers, adrift in the oceans of Hawaii. Here, he and Harris discuss this earlier project that brings together the landscapes of Utah deadlands, a former nuclear test site in Nevada, and copies of Playboy magazine.

This article originally appeared in Issue 14 of the Aperture Photography App.

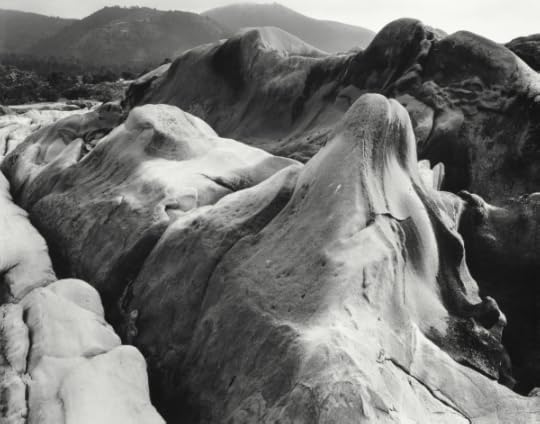

Spreads from Violent Legacies (1992).

Melissa Harris: How does Violent Legacies fit into your ongoing Desert Cantos project?

Richard Misrach: I began the Desert Cantos project around 1979. For over a decade, I have been searching the deserts of the American West for images that suggest the collision between “civilization” and nature. The three cantos that make up Violent Legacies are part of this larger project, but deal specifically with militarism and cultural violence.

The “canto” idea is actually very simple. It’s a structural term meaning the subsection of a long song or poem. Throughout the history of literature it has been repeatedly used. Most people are familiar with Ezra Pound’s epic poem, The Cantos, or Dante’s Inferno, which is subdivided into cantos.

I found that, photographically, my work in the desert naturally broke into subseries. Each subseries, or canto, was independent, but related to the others. Combining the cantos created an epic, comprehensive relationship. Now I’m on “Desert Canto XIV.”

I tend to work on several cantos simultaneously. I give them numbers upon completion, instead of when they are initiated, because they can change significantly as they evolve. The three cantos that comprise Violent Legacies are: “Desert Canto IX: Project W-47 (The Secret)”; “Desert Canto VI: The Pit”; and “Desert Canto XI: The Playboys.”

Thus far, there are fourteen fully defined cantos (although some are still in progress) and a prologue. From one to fourteen, the cantos are: “The Terrain”; “The Event”; “The Flood”; “The Fires”; “The War (Bravo 20)”; “The Pit”; “Desert Seas”; “The Event II”; “Project W-47 (The Secret)”; “The Test Site”; “The Playboys”; “Clouds (non-equivalents)”; “The Inhabitants”; and “The Visitors.”

Spreads from Violent Legacies (1992).

MH: I know that some of your pre-cantos work was also done in the desert. There was a whole series of night desert landscapes of cacti and palm trees that were made in the mid-’70s. What is it about the desert that holds such a fascination for you?

RM: I am not certain what it is that makes it so compelling. It does seem that the severity of the landscape sets cultural artifacts off in dramatic relief. The paucity of life there—in comparison with other environments, like forests and cities—is a reminder of how fragile human existence is. The desert has always provided rich material for literature and the visual arts, from the Bible to science-fiction films, probably because it epitomizes the extremes of the human condition.

And the deserts of the American West are particularly interesting because of their role in determining a peculiarly American identity and mythology. But I don’t think I could have sustained this project for as long as I have if I didn’t enjoy the process of working in the desert so much. It’s the heat, the feel of the earth, the rich solitude and silence, and the remarkable scale of everything that makes being there so deeply fulfilling. I’ve always had this strange sensation of being a small figure in a vast landscape—as if I were seeing myself from the air. My best ideas seem to come when I’m driving those long stretches of desert highway. Physically and mentally, that’s where I feel the most alive. . . .

MH: What are the relationships among your artistic intentions, your political activism, and your evident desire to uncover truths? Is your work journalistic documentation? Is it about aesthetics? Or is it a sort of hybrid?

RM: First off, all art reflects one’s politics, whether consciously or otherwise. Certainly, some images are more overtly political than others. Sometimes the politics are layered, problematic, and very complex. Being a white, male, American artist affects or skews my perspective on everything I do from the outset. The best I can do is try to keep this self-consciousness at the forefront while I work, and not assume that the “truths” I discover are objective or universal.

The very act of representation has been so thoroughly challenged in recent years by postmodern theories that it is impossible not to see the flaws everywhere, in any practice of photography. Traditional genres in particular—journalism, documentary studies, and fine-art photography—have become shells, or forms emptied of meaning. Victor Burgin underscored a significant point when he made the distinction between the “representation of politics” and the “politics of representation.” Nonetheless, despite the limitations and problems inherent to photographic representation (and especially the representation of politics), it remains for me the most powerful and engaging medium today—one central to the development of cultural dialogue.

The Desert Cantos project of the last decade has shifted somewhat in the nature of its representation. The earliest series, “The Terrain,” “The Event,” “The Flood,” and “The Fires,” for example, were more or less aesthetic metaphors. Recent cantos, however, have become more explicitly political. The “Bravo 20” project points a finger directly at military abuse of the environment. I think the three cantos in Violent Legacies hover between the two.

Spreads from Violent Legacies (1992).

MH: Richard, your photographs are visually very seductive. Yet your subjects are death, contamination, and violence. Are you perhaps aestheticizing the horrific, and thus exploiting it?

RM: Probably the strongest criticism leveled at my work is that I’m making “poetry of the holocaust.” But I’ve come to believe that beauty can be a very powerful conveyor of difficult ideas. It engages people when they might otherwise look away.

Recent theory has been critical of the distancing effect of artistic expression—“Create solutions, not art.” But the impact of art may be more complex and far-reaching than theory is capable of assessing. To me, the work I do is a means of interpreting unsettling truths, of bearing witness, and of sounding an alarm. The beauty of formal representation both carries an affirmation of life and subversively brings us face to face with news from our besieged world.

The post An Archival Interview with Richard Misrach appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 28, 2015

Closing Deadlines for Fall 2015 Aperture Workshops

The Aperture Foundation workshop program continues a valued tradition originating with Aperture magazine’s founding editor and legendary teacher, Minor White. Known for his open-minded, inventive, and insightful approach to teaching, White leaves a legacy that defines the workshop program at Aperture. The workshops bring students, professionals, and amateurs together with leading photographers working in a variety of fields and genres for intensive educational experiences. Our classes focus on topics related to photobook design and history, current photographic practice, and the history of the medium.

Jamey Stillings, Nevada Arch Segment, April 29, 2009; from the series The Bridge at Hoover Dam

Mary Virginia Swanson: Securing Support for Your Long-Term Project

Saturday, September 12, and Saturday 19, 2015 11:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m., both days

Registration ends Sunday, September 6, 2015

Join Mary Virginia Swanson for a two-part workshop designed for photographers who would like to learn how to secure funding for a long-term personal project through drafting a successful proposal and budget, as well as learn how to build awareness for that project. The workshop will also explore various types of funding, as well as different approaches to expanding your audience.

Mary Virginia Swanson is an author, educator, and consultant who helps artists find the strengths in their work, identify appreciative audiences, and present their work in an informed, professional manner. Her seminars and lectures on marketing opportunities aid photographers in moving their careers to the next level.

Swanson is the recipient of the 2013 Focus Lifetime Achievement Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography, and the 2014 Susan Carr Award for Education from the American Society of Media Photographers. The Society for Photographic Education named her the 2015 Honored Educator. Swanson coauthored Publish Your Photography Book (revised edition, 2014) with Darius Himes. Her latest publication, Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs, will be released in 2015.

The featured image, Nevada Arch Segment, April 29, 2009 is from Jamey Stillings’ exhibition and book of the same name, The Bridge at Hoover Dam, a project that is featured as a case study in Swanson’s upcoming publication, Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs.

Photograph by Brendon Baker and Daniel Evans, from Self Publish, Be Happy (Aperture, 2015)

Bruno Ceschel: The Self-Published Photo Book

Saturday and Sunday, September 26-27, 2015 11:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m., both days

Registration ends Sunday, September 20, 2015

Join Bruno Ceschel, founder of Self Publish, Be Happy—and author of the book of the same name, to be published by Aperture in fall 2015—for a two-day intensive workshop conceived for people interested in publishing their own photobooks.

Bruno Ceschel is a writer, curator, and lecturer on photography at the University of the Arts London. He is the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy (SPBH), an organization that collects, promotes, and studies contemporary self-published photobooks. SPBH’s library contains more than two thousand publications, and the organization produces an extensive series of workshops, talks, and projects. Self Publish, Be Happy has organized events at a number of institutions around the world, including Aperture, Tate Modern, The Photographers’ Gallery, Serpentine Galleries, C/O Berlin, and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, among others. Ceschel is also the director of SPBH Editions, which has most recently published books by Cristina de Middel, Lucas Blalock, Mariah Robertson, Gareth McConnell, and Lorenzo Vitturi. Ceschel writes regularly for a number of publications, such as Foam, the British Journal of Photography, and Aperture magazine, and has guest-edited issues of Photography and Culture, OjodePez, and The PhotoBook Review.

Doug DuBois, Lise and Spencer, Ithaca, NY, 2004

Doug DuBois: The Intimate Photograph

Saturday, October 3, Saturday, October 17, 2015 11:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m, both days

This workshop is sold out. Please contact education@aperture.org to be placed on the waiting list.

Join photographer Doug DuBois for a two-part workshop through which students will gain a better understanding of how to articulate intimacy and explore ways of creating photographs that demonstrate a certain closeness between photographer, subject, and viewer. Students will work with DuBois to assemble a rhetorical rather than purely emotional guide to photography’s intimate claims.

Doug DuBois has photographs in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He has received fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and National Endowment for the Arts. DuBois has exhibited at the J. Paul Getty Museum and MoMA, The Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin and the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma in Italy. He has photographed for magazines, including the New York Times Magazine, Time, Details, and GQ. He has published two books with Aperture: All the Days and Nights in 2009 and My Last Day at Seventeen, which will be available in the fall of 2015. DuBois teaches in the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University and in the Limited Residency MFA program at Hartford Art School.

The post Closing Deadlines for Fall 2015 Aperture Workshops appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 26, 2015

An Interview with Bruce Davidson

The fall issue of Aperture magazine comprises nine in-depth interviews with major photographers who have spent their lives working as image makers; some subjects have doggedly been at it for more than six decades. Here, we offer a preview of one interview, conducted by curator Charlotte Cotton, with the legendary documentarian Bruce Davidson. “Too much in photography is shoot and leave,” Bruce Davidson says in this candid conversation, referring to how he has remained in contact with the subjects seen in many of his now-iconic projects, including his work on the civil rights movement. Now eighty-one, Davidson has been looking back through his archive, revisiting older projects, including a series shot in Los Angeles 1964. For this interview, excerpted below, Cotton visited Davidson at his home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side last April, where the two spoke about the arc of his extraordinary career that began in the 1950s and continues today.

This article originally appeared in Issue 14 of the Aperture Photography App.

New York City, 1959, from the series Brooklyn Gang

Charlotte Cotton: How did you develop your skills as a photographer when you were young?

Bruce Davidson: There was a camera store in town—Austin Camera. They took me on as a stock boy: I dusted the cameras, cleaned the toilets and the floors. And an old country gentleman came in. His name was Al Cox and he had a studio in the town. He told me, “Anytime you want to come by, kid, I’m there.”

So I did. He was an incredible craftsman. First of all, he could make dye-transfer prints, so I was exposed to the process. He was a commercial photographer working for the newspaper and I’d go along with him. He would shoot with a Rolleiflex and a flash. Whenever my mother called to find me, I was always with Al Cox. When I was admitted to RIT [Rochester Institute of Technology], Al read somewhere that the first thing I would be doing was pinhole photography, so he made me a pinhole camera with interchangeable pinholes. So he sent me off to college. He could also build strobes and was a ham radio operator. He was a genius old guy—he was an old guy to me.

Selma, Alabama, 1965, from the series Time of Change

CC: Tell me about the relationship you were forming with cameras and all the material stuff of photography, like chemicals. It’s one thing—which I’m sure we will come back to—to think of photographic capture, of looking and learning about the world through photography. But it sounds like you were also learning through Al Cox about technology and materials of photography and about how to render something, not just capture it.

BD: It meant a lot to me. I bought an old 35 mm Contax camera when I was at RIT. Walking the streets at Rochester, I found the Lighthouse Mission. It was very atmospheric—a place where these vagrant men would come to get a bologna sandwich and listen to the sermons. I was already exposed to the idea of not a picture but a series.

CC: And that would have meant the picture magazines at that time, such as Time?

BD: Well, yes. My hero was Gene Smith [W. Eugene Smith]. There were two young women in my class at RIT and one of them had a copy of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1952 book The Decisive Moment, and she showed it to me. There was also an inspiring teacher, Ralph Hattersley. He showed us Smith, Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn, and others. This really sent me in that direction—not imitating, but finding the way I wanted to photograph.

Blonde girl sitting in the park, London, 1960

CC: What did you feel you were seeing in Cartier-Bresson’s photographs? What resonated with you?

BD: The way he saw life. Life was moving; the world was in flux.

James Duffy and Sons Circus, Ireland, 1967, from the series Circus

CC: So did this feel attainable to you—did figures like Smith and Cartier-Bresson seem close to you?

BD: Oh yes. There was a gallery in New York called the Witkin Gallery. And Gene Smith used to go there. I used to go up to the gallery and see him and I just couldn’t say anything. He saw that I was doing good work but I couldn’t touch him. Later I really got to know Cartier-Bresson. After college at RIT, I spent some time in the photography department at Yale—I was in the graphic designer Herbert Matter’s class. I was drafted and sent to the Arizona desert, but before I went I photographed the Yale football team, not the game, but the tension and the mood among the players. I submitted the pictures to Life magazine. A year went by, and then they ran them. The captain in charge of the labs had been in the barbershop and had seen my pictures in Life. He burst into the darkroom and said, “Private, did you take these pictures?” I said, “Yes, sir, I did.” And he said, “Take that mop away, you are photographing the general this afternoon.” That was a real decisive moment.

Yale football, New Haven, Connecticut, 1954, from the series Yale Football

Somehow, I got really lucky and I was sent to the photo-labs for the Signal Corps in Paris. I was in the supreme headquarters in Paris and there were French soldiers in this international camp and I took up a friendship with a French soldier who was a painter. He took me home to his mother’s house in Montmartre to have lunch. And that’s when I saw the widow hobbling up the street. “This woman lives above us in a garret,” he told me, “and she knew Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin.” I had a motor scooter, so I would go up from the fort to Montmartre to photograph her. That’s when I submitted my work to Cartier-Bresson at the Magnum Paris office. It took a couple of weeks before I got an appointment with him. He was very interested in the contact sheets and the rhythm implicit in shooting. Then I walked outside with him and it was like the street was made up of his pictures. All those moments were there if you could just take a chance.

Click here to find the complete interview from Aperture magazine on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post An Interview with Bruce Davidson appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 25, 2015

The Interview Issue Aperture #220 – Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #220, Fall 2015. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Clockwise from top left: William Klein, 1978; Boris Mikhailov, 2014; Rosalind Fox Solomon, 2002; Ishiuchi Miyako, 2012; Guido Guidi, 1997; David Goldblatt, 2009; Bertien van Manen [Eikenhorst], 1973; Bruce Davidson, 2015; center: Paolo Gasparini, 1978.

What compels someone to become a photographer? And what drives someone to continue to be one, for as many as seven decades? How does a veteran photographer describe years of questioning politics, personal experience, social unrest, landscape, and history through the camera?

For this issue we have broken with our usual “Words” and “Pictures” format to offer nine in-depth interviews, firsthand accounts that underscore the generosity and intelligence of their speakers. Born between 1928 and 1947, the nine photographers here—Bruce Davidson, Paolo Gasparini, David Goldblatt, Guido Guidi, Ishiuchi Miyako, William Klein, Bertien van Manen, Boris Mikhailov, and Rosalind Fox Solomon—are still active today, adding to their already unparalleled bodies of work. In these pages, the medium is considered from various points of view, offering a range of philosophies, values, and perspectives, yet for all the differences within this group, they share a fundamental curiosity about the human experience.

The interviews took place around the globe, and five of the nine were conducted in languages other than English, in the photographers’ native tongues: Japanese, Russian, Italian, Spanish, and Dutch. No matter the language, an underlying passion and drive come through in the force of each speaker’s words. William Klein, for example, now eighty-seven, is sharp-witted and voluble; his anecdotes project ecstatically. No surprise, then, that we learn through the course of his conversation with writer Aaron Schuman that Klein had been out until very late the previous evening at filmmaker David Lynch’s club in Paris.

That kind of restlessness characterizes each speaker. Solomon and van Manen are both peripatetic, having traveled throughout the world to focus on questions of community, ritual, place, and gender identity. Guidi, known for his understated images of European towns, meditates on how the mechanics of images, specifically perspective, allow for a description of the world—a world that is often politically fraught. Goldblatt has long used the camera to reflect the social realities of apartheid and postapartheid South Africa. For Gasparini, who has documented social conditions in his adopted city of Caracas, postrevolutionary fervor in Cuba, and experiments in architecture across Central and South America, photography cannot be split from ideology. Empathy for others has likewise motivated Bruce Davidson, who remarks that the joy of photographing, and returning to former subjects, sustains him. Ishiuchi was a reluctant photographer at first, but succumbed to the physical presence of pictures and their ability to trace history and time, from the personal (her relationship to her mother) to history on an incomprehensible scale (the bombing of Hiroshima).

These lifetimes of seeing through the lens might best be summed up by Boris Mikhailov, who made much of his work under oppressive Soviet rule. “When you’re open to life, it responds to you,” he remarks. “That is what an intuitive possibility of photography is—to crawl deeper into the depths of life.”

—The Editors

The post The Interview Issue

Aperture #220 – Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 19, 2015

Watch: Imaginary Club, Winner of PhotoBook of the Year 2014

Imaginary Club, last year’s winner of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards PhotoBook of the Year, sold out within months of winning the award. In 2016, Gwinzegal and Böhm/Kobayashi will reissue the photobook, which will only be available via pre-order. In this video, Sieber talks about the photobook and what went into his work.

Enter now for your chance to win in one of three categories of the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. Since 2012, the PhotoBook Awards have granted prizes in the categories of PhotoBook of the Year, First PhotoBook, and starting last year, Photography Catalogue of the Year. The call for entries began May 4 and ends September 11.

Click here for more information about Imaginary Club and to place your pre-order.

The post Watch: Imaginary Club, Winner of PhotoBook of the Year 2014 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Review: Heritage and Home: Photographs of Hickory Nut Gap Farm

Diana C. Stoll reviews Ken Abbott’s new exhibition at the Asheville Art Museum, North Carolina, which focuses on the day-to-day of a prominent local farm and its inhabitants.

By Diana C. Stoll

All photographs Ken Abbott, Hickory Nut Gap Farm series, 2012. Courtesy the artist.

Our place here is just a dream, darling, and some day we will be sitting [you] . . . down on a wide porch with a whole stretch of superb mountains out in front. Then dear, you’ll be set down to a table full of country food & after that tucked into bed . . . & you’ll sleep as you haven’t slept in years.

A 1916 letter written by Elizabeth McClure, enticing her cousin Martha to visit her new home, describes a former stagecoach stop known as Sherrill’s Inn located in the hills of western North Carolina. Elizabeth and her husband, Jim, were newlyweds from the North traveling on their honeymoon when they first saw the big house—perched at the top of a slope overlooking acres of fields and farms. North Carolina was not familiar territory for them: Jim McClure was a Yale- and Oxford-educated Presbyterian minister, his young bride a painter who had studied in Europe. Yet they were smitten, and purchased the inn and surrounding land, thus beginning a chapter in the life of Hickory Nut Gap Farm that continues today, a century—and five generations of family—later.

The legacy of a single house can be more enduring than its transitory inhabitants, but in the case of the McClures and their offspring, there has also been a sustained tribal ethos over the decades that seems to have permeated the very walls. The family has been a hub of the community since 1920, when the McClures founded a regional Farmers’ Federation. Later scions of Hickory Nut Gap include the late James Clarke (farmer and congressman in the 1980s) and John Ager (farmer and Democrat in the North Carolina House of Representatives). And yet, whatever local prestige their status might imply, this is a place of groundedness. Everyone tends the land, and in the house, today’s residents live their chaotic lives: beds are sometimes left unmade and sinks are often filled with dishes. It is a place, however, with a perceptible aura of history and lore.

Photographer Ken Abbott first visited the house and farm in 2004 on a trip with his daughter’s preschool, determined to return with his camera. And so he did—again and again, over a decade, discovering new corners with each visit. With his ever-deeper visual understanding of the place and the family, Abbott’s photographs do great justice to the complex life of Hickory Nut Gap Farm, as seen in his book Useful Work (Gooseberry Studio & Press, 2015—with essays on the family’s story by historian Rob Neufeld) and in the exhibition Heritage and Home, currently on view at the Asheville Art Museum.

Abbott’s background has equipped him well for this project: as an undergraduate at Colorado College in the late 1970s, he studied with Frank Gohlke, and after attending Yale’s MFA program in photography, Abbott returned to his native Colorado, where he found an advisor and friend in Robert Adams. Abbott’s mentors seem to have provided him both inspirations as well as aesthetic and emotional stances against which to press. Like Gohlke and Adams—and like Eugène Atget, Lewis Baltz, Walker Evans, and many others—Abbott deftly straddles a line in his work between document and art. Unlike them, he rarely adopts a visual tone of dispassion, and instead revels (and allows us to revel) in the sheer handsomeness of colors, forms, depths, and nostalgic narratives. The elements the McClures surely fell in love with a century ago are palpable in Abbott’s images.

Abbott investigates the near and the far: from the weathered, wooden exterior walls of a smokehouse to the voluptuous gray swells of the distant mountains. Day-to-day implements and chores—the “useful work” of Hickory Nut Gap Farm—are shown to be embodiments of beauty: a wood-burning stove in the kitchen (undoubtedly a nod to Evans); rag rugs hung on a fence to dry; a triangular barn behind a white-picket proscenium. One senses some obligation in his images of visiting children—they are almost jarringly of the present—whereas other portraits, of farmworkers and family members, seem absolved from debt to any particular era. A young farmer presses a shovel into a row of carrots with a purposeful gesture; another lifts a young lamb, checking its belly with all the heedfulness of a new father. This is not for show; it is how farms have operated for millennia.

The meaning in these photographs derives mainly from the layered histories they reveal. In one image we encounter an antique highboy dresser—a venerable old Queen Anne specimen, so tall it nearly touches the ceiling of a book-lined room. Its drawers are all ajar, exploding with clothes, a captain’s hat slung on one side and a keffiyeh on the other; and perched on top is what looks like a purple-velvet dog bed. Here the old and the new coexist, sometimes humorously, in jumbled harmony.

One of the most lyrical photographs in Abbott’s collection is of a silver pitcher sitting on a blue Formica kitchen countertop. The pitcher, its curves reflecting white light from the window and the blue of the counter, sits by a glass of water, a Mason jar, a dish drainer stacked with pots, and a plastic bottle of dish soap. Abbott informs us that this pitcher, which once belonged to Elizabeth McClure, is still used by the family every day to bring water from the springhouse to their table. It is, he writes, “an aesthetic connection for the family to Elizabeth, but also . . . a connection to the place.” Like many of the images in this series, the photograph captures the intimate, living spirit of this home, where the now collides so propitiously with the then.

Heritage and Home: Photographs of Hickory Nut Gap Farm is on view at the Asheville Art Museum, North Carolina, July 18–October 11, 2015.

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in western North Carolina.

The post Review: Heritage and Home: Photographs of Hickory Nut Gap Farm appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 18, 2015

Inside the PhotoBook Award Entries

By Freddy Martinez

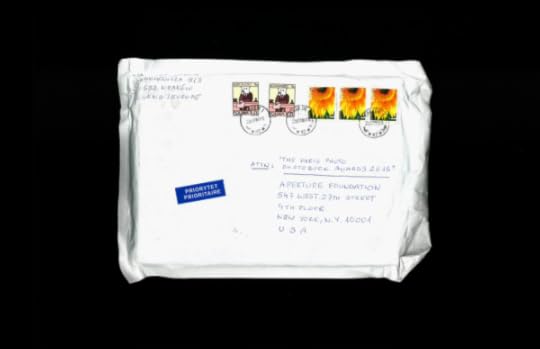

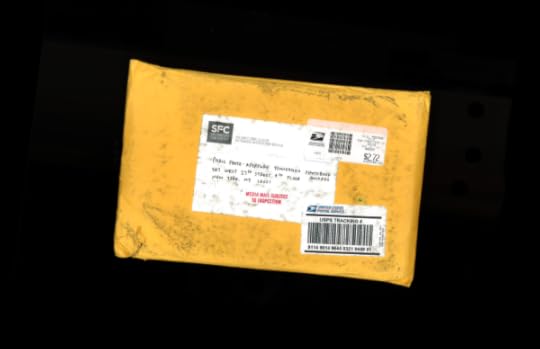

Photobooks from around the world—from Tokyo to Paris to Los Angeles—are currently arriving at Aperture’s Chelsea office as entries to this year’s Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, an annual celebration of the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. Since 2012, the PhotoBook Awards have granted prizes in the categories of PhotoBook of the Year, First PhotoBook, and starting last year, Photography Catalogue of the Year. The call for entries began May 4 and ends September 11. On September 18, thirty-five short-listed photobooks, chosen by representatives of both Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation, will be announced at the NY Art Book Fair.

On July 30, Aperture’s creative director Lesley A. Martin, photographer Penelope Umbrico, and digital media assistant Max Mikulecky, unboxed twenty entries at the Aperture offices, in part to record the details of the arrivals but mainly to preview the photobooks inside. The various packages tell a story of their own. They arrive with handwritten addresses, from meticulous uppercase to functional cursive, bearing a notable array of stamps from a Polish astrological-themed scene of a Capricorn goat sitting at a desk, to a sampler of stamps from Brazil that honors six species of stingless bees.

“The first thing I do is flip through,” Martin said after unboxing the first package. “I want to see the overall universe of it. And then I go back and look more carefully at all its individual components. I try to figure it out.” The above slideshow offers a look at the first few entries.

Click here to find out more about how to submit to the PhotoBook Awards.

Freddy Martinez is the Digital Media Work Scholar at Aperture Foundation.

The post Inside the PhotoBook Award Entries appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 17, 2015

Issue 14 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 14:

● An interview with Bruce Davidson from the upcoming fall issue of Aperture magazine

● An inside look at the entries arriving for this year’s PhotoBook Awards

● A review of Ken Abbott’s exhibition at the Asheville Art Museum, North Carolina

● An interview with Richard Misrach from the Aperture archive

● More about Aperture’s rerelease of Sebastião Salgado’s Other Americas

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 14 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 12, 2015

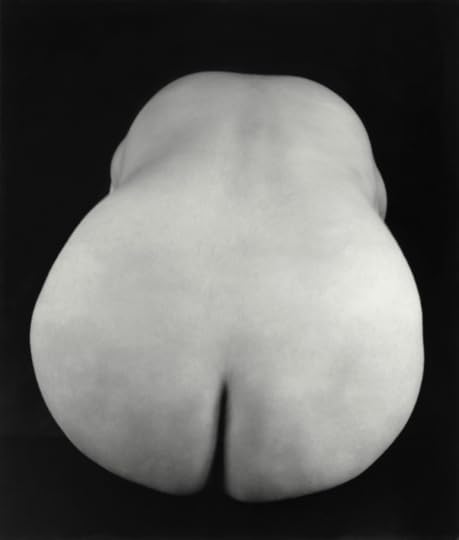

Edward Weston’s The Flame of Recognition

The Flame of Recognition, the classic monograph by Edward Weston, first issued as a hardcover in 1965, began its life in 1958 as a monographic issue of Aperture magazine in celebration of Weston’s life. Weston (1886–1958) began to earn an international reputation for his portrait work in 1911, and from 1923 to 1926 worked in Mexico and California, turning to subjects such as nudes, clouds, and close-ups of rocks, trees, vegetables, and shells. Now, fifty years later, Aperture reissues this volume, covering Weston’s greatest works, from the portraits and nudes to the landscapes and still-lifes. Photographer and founding member of Aperture Ansel Adams contributed the following essay, written in 1964, a posthumous tribute to the artist.

This article originally appeared in Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App.

By Ansel Adams

Cabbage Leaf, 1931

In the six years since Edward Weston passed away in Carmel, California, he remains in memory as a man of great spirit, integrity, and power. To me, he was a profound artist and friend in the deepest sense of the word. Living, as I do now, within a mile of his last home, sensing the same scents of the sea and the pine forests, the grayness of the same fogs, the glory of the same triumphal storms, and the ageless presence of the Point Lobos stone, I find it very difficult to realize he is no longer with us in actuality.

Nude, 1926

Edward understood thoughts and concepts which dwell on simple mystical levels. His work—direct and honest as it is—leaped from a deep intuition and belief in forces beyond the apparent and the factual. He accepted these forces as completely real and part of the total world of man and nature, only a small portion of which most of us experience directly. As with any great artist or imaginative scientist, the concept is immediate and clear, but the “working out” takes time, effort, and conscious evaluations.

Edward Weston’s work stood for him as a complete statement of the man and his art. He favored the grand sweep of creative projects. He was aware of the loneliness of the artist, especially the artist in photography, photography where out of the uncounted thousands of photographers only a handful of workers support the best of photojournalism, illustration, documentation, and poetic expression. And it was Weston who accomplished more than anyone, with the possible exception of Alfred Stieglitz, to elevate photography to the status of fine-art expression.

South Shore, Point Lobos, 1938

His approach bypassed the vast currents of pictorial photography, photojournalism, scientific-technical photography, and what is generally lumped together as “professional photography” (portraits of the usual “studio” kind, illustrations, and advertising). Through his kind of photography he opened up wonderful worlds of seeing and doing.

Tina Reciting, 1924. All photographs by Edward Weston, Collection Center for Creative Photography

Many were the students and experts whose lives and concepts were profoundly modified by Edward’s nonaggressive, non-preaching, but ever-comprehending approach to people and their expression problems. “Seeing” the Point Lobos Rocks was one thing, but encouraging another person to “see” something in his own way was the most important thing of all. Edward’s works need no evaluation here. I would prefer to join Edward in avoiding verbal or written explanations and definitions of creative work. Who can talk or write about the Bach partitas? You just play them or listen to them. They exist only in the world of music. Likewise, Edward’s photographs exist only as original prints, or as in this monograph, in superb reproductions. Look at his photographs, look at them carefully, then look at yourselves—not critically, or with self-depreciation, or any sense of inferiority. Read the material from his Daybooks and letters so carefully compiled, edited, and associated with the photographs by Nancy Newhall. You might discover through Edward Weston’s work how basically good you are, or might become. This is the way Edward Weston would want it to be.

Click here to find The Flame of Recognition on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Edward Weston’s The Flame of Recognition appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 11, 2015

An Interview with Richard Learoyd from the Archives

In Aperture magazine #199, from 2010, writer Peggy Roalf interviewed Richard Learoyd about his life-size portraits made with a room-size camera obscura, on the occasion of his first U.S. solo exhibition. This fall, Aperture will release Day For Night, a deluxe monograph of Learoyd’s photographs, to coincide with a solo exhibition of the artist’s work at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. “Time, motion, speed—some of photography’s attributes that are enhanced by the effect of a frame, and that often distance this medium from painting—are absent,” Roalf writes in the introduction to her interview. “But the massive scale and surface quality of Learoyd’s portraits share features with both the painting and the photography of nineteenth-century France; they have an intentionality that is imposed by the maker rather than received from the sitter. This is perhaps why his photographs invoke the sublime.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App.

Harmony in White, 2012

Peggy Roalf: I was reading an essay by Mark Haworth-Booth recently about William Henry Fox Talbot. He was onto the magic of photography and talked about his invention as if it were a fairytale, and about nature as “a field of wonders past our comprehension.” I was wondering, have you found inspiration in Fox Talbot’s work and writings?

Richard Learoyd: I think many contemporary photographers would be foolish to deny the influence of Fox Talbot. Andreas Gursky and the Prada series, for example, or Robert Mapplethorpe’s ladders, and now Hiroshi Sugimoto with his new positive images.

I often muse over what might have come about if Fox Talbot had not invented the means to reproduce photographic images as multiples; maybe a completely different way of seeing would have emerged, leaving photography as a more singular viewing experience, where the value of the photographic object was maintained. But what Fox Talbot did was to introduce larger issues of mortality and religion into photographic imagery. The sometimes clumsy symbolism—which could seem irrelevant in our time—undoubtedly speaks of someone inventing a new visual language. The ladder rising into the blackness of a hayloft (from hisPencil of Nature) is a strong influence; for me it is the first word in an emerging photographic language.

I see my work more in the lineage of the French—referring to daguerreotypes: those non-reproducible photographic objects whose multi-planed surface and miraculous depth of field fascinate me. With my work I am interested in the moment when the image becomes dye and color, when the illusion of it being a reflection or projection breaks down. I think you get that sense with daguerreotype images: you see the object before the illusion. With my pictures, the illusion is very strong and breaks suddenly, and often only momentarily, which is something I like.

PR: The nature of film photography today generally excludes any sense of the surface from its describable qualities. When and how did you realize that you could bend traditional photographic processes to create the sense of mass and volume that’s evident in your photographs?

Agnes in Red Dress, 2008

RL: I was lucky enough to be in the generation before computers became the norm. I studied at Glasgow School of Art under Thomas Joshua Cooper, who is a wonderful landscape artist. During that time the frontier seemed to be a place of ideas realized with persistence and craft, where all was valued until proved useless. I look back at the time I had there and realize that’s when my life really began.

I first started experimenting with the camera obscura, or the room-camera method that I use now, during my postgraduate year at Glasgow. It was Cooper who lent me the lens from a nineteenth-century portrait camera he had in his office. At the time postgraduate students were given studios; this enabled me to experiment with a different set of ideas instead of being out in the world searching for something to photograph. Until then, my work had been landscape-based; it was fairly quiet and thoughtful, almost reticent in a way. I suppose something in me craved a sense of power or directness in my work that I felt was lacking in my landscape photographs. Working with the camera obscura seemed to satisfy this need.

For the next several years I taught photography at a university and worked as a commercial photographer. At a certain point I had learned what I could from that and it was time to get on with being an artist. In 2004 I built the first version of the camera I use now, as an extension of the work I had begun fourteen or so years earlier. But now I knew what I was doing. I was inventing photography for myself in a way that I could, and began making the photographs I had imagined could be made. I don’t know why, but the camera obscura seemed to me the most natural of methods. The apparatus I use consists of a lens, some lights, and a processing machine. The process has certain built-in qualities to do with physics and optics, but the most important quality for me is that it is capable of producing photographs that fascinate me, that match my vision.

It is an incredibly restrictive process and there are many things you simply can’t do. It’s slow and painstaking, with much that can go wrong. The method gives parameters of what you choose to photograph. It’s very liberating to have limited choices, and the technique offers immediacy as it jumps past the printmaking process.

Man with Octopus Tattoo, 2011. All photograhs © Richard Learoyd

PR: At one point you mentioned that people in charge of their bodies, such as dancers, seem to have a different center of gravity. How does this observation manifest in your work?

RL: One thing that this process, at best, can do is to translate weight, density, and mass—not only in a physical sense, but in a more psychological way. When a picture is successful, the mental state of the sitter seems to radiate from that person’s physicality.

PR: The surface quality of your photographs is remarkable, in its sharpness, and in the way that you adjust the focal plane to shift back and forth within an extremely shallow range. Can you point to a moment when you found that this was possible on a large scale?

RL: While I must admit to disliking the use of shallow focus in most conventional photographs today (it seems like a device within a device), I think a big influence on my understanding how the focus issue could work for me was revisiting some early Lewis Baltz pictures of scrubland. Don’t ask me why, but they stuck in my mind. The minute depth of field in these pictures is part of a restrictive practice; it’s quite simply physics. Every artist, whatever their medium, has to deal with the rules of the universe. I think the secret is to accept it and move on. For me, in my work, the implication or meaning of this shift between extreme sharpness and blur is an emerging and submerging of a person’s consciousness, and emphasis of their immediate presence.

Click here to find Day For Night, available this fall, on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post An Interview with Richard Learoyd from the Archives appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers