Aperture's Blog, page 157

June 29, 2015

Images of Conviction at Le Bal, Paris

By Carole Naggar

Built on the site of a popular 1920s ballroom in the eighteenth arrondissement of Paris, Le Bal is an innovative space dedicated to documentary photography and video. Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence, which opened on June 4, presents ten case studies that demonstrate how photography and video have functioned in the evidence of death: how were these protocols invented? How did they become legitimate? How were they applied in legal settings? This exhibition, conceived by Le Bal director Diane Dufour, offers viewers access to documents that had until now been either lost or overlooked. The following are a few examples of the ten case studies that appear in the exhibition.

This article originally appeared in Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App.

Left: Alphonse Bertillon, Murder of Monsieur Canon, boulevard de Clichy, 9 December 1914; center: Alphonse Bertillon, Murder of Monsieur André, boulevard de la Villette, Paris, 3 October 1910; right: Alphonse Bertillon, Murder of Madame Langlois, Puteaux case, 5 April 1905 © Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris.

Bertillon’s Metric Photography

Ten years after Alphonse Bertillon was appointed head of the Paris Préfecture de Police Photography Department in 1882, he developed a scientific means of recording crime scenes: metric photography. The photographs were taken using a wide-angle lens fitted on a camera that stood on a two-meter-high tripod, giving a precise representation of the crime scene that was not only useful for the police enquiry, but also for the judge and jurors during the trial. Bertillon thought that such photographs could be a powerful tool in the justice system: they would have an emotional effect on the accused, inciting him to confess his crime, and on the judges, giving them a sense of the atmosphere and all the details in a way that words alone could not address. All the elements of the scene were recorded: position of the body, situation of the weapons, of the objects and traces. Bertillon’s photographs form the base of modern criminal proceedings, which still use his methods, and are ancestors to contemporary 3-D reconstructions of crime scenes.

Two enlarged views of Secondo Pia, The Holy Shroud, 1898.

The Shroud of Turin

Secondo Pia, an amateur photographer, was the author of the first photographs of the Shroud of Turin as it was displayed in 1898. As he developed his photographs, he discovered on the picture negative an imprint of a face and body, which he thought were those of Christ. Strangely enough, face and body were positive imprints, as if the shroud itself, which has been dubbed “the first photograph of crime,” was the negative. This was the start of a long-lasting debate on the authenticity of the relic. In 1902, the biologist Paul Vignon published a detailed study of the photographs. In 1986, the shroud was tested with carbon 14 and the test revealed that the fabric only dated back to sometime between 1260 and 1390. Today the shroud still remains an object of veneration for the faithful, fascinated by the image and unconvinced by the scientific proof.

Left: Marfa Ilinitchna Riazantseva, Russian, born in 1866 in the village of Kosafort, close to Makhatchkala, Daghestan, knowing barely how to read and write, no party, retired. Domiciled in Moscow, 1re Mechtchanskaïa 62, apartement 26. Arrested 27 August 1937. Sentenced to death 8 October 1937. Executed 11 October 1937. Rehabilitated in 1989; right: Alekseï Grigorievitch Jeltikov, Russian, b. 1890 in the village of Demkino, Riazan region. Primary school. Left the VKP(b) in 1921, indicating his disagreement with the Party’s New Economic Policy (NEP). Locksmith in the Moscow metro workshops. Domiciled in Moscow, Sadovaia-Tchernogriazskaia 3, apartment 41. Arrested 8 July 1937.Sentenced to death 31 October 1937. Executed the next day. Rehabilitated in 1957. © Central Archives FSB and National Archives from the Russian Federation GARF, Moscow, copies published from the Archives of the Association internationale Memorial, Moscow.

The Great Purge in the USSR 1937–38

Twenty years after the October Revolution, Joseph Stalin initiated a large-scale campaign of terror—the first genocide in history conceived by a state leader against his own people. Approximately 1.7 million people were arrested, and from August 1937 to November 1938, 750,000 people (one adult out of 100 in the Soviet Union) were executed after being tortured into confessing to crimes they had not committed. More than 700,000 were condemned to the gulag and would die in the following years. Le Bal’s exhibition includes portraits of those sentenced to death taken by the NKVD, the Soviet law enforcement agency, just moments before their execution. The mug shots followed the style inherited from Bertillon’s identification system. The same system was later used by the Khmer Rouge to photograph victims.

In 2008, Polish photographer Tomasz Kizny obtained permission to rephotograph 250 portraits directly from the NKVD files. These haunting photographs give back a face and a memory to innocent people that have been annihilated by a dictatorial regime.

Images of Conviction is on view at Le Bal, Paris, through August 30.

Carole Naggar has been a regular contributor to Aperture magazine since 1988.

The post Images of Conviction at Le Bal, Paris appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 26, 2015

Tonight: The BlowUp Hosts Live Storytelling Event in NYC

Stefan Ruiz, Michel, Monterrey, Mexico from The Cholombianos series, 2011

The tales behind the making of a photograph can be legendary, and these stories of intimate, insane, and oftentimes-unimaginable moments can be heard at New York’s newest photography event series, The BlowUp. Presented and produced by the photography blog Feature Shoot, The BlowUp brings together a curated selection of influential photographers each telling the story behind one of their favorite photographs they took. The themed events first started in April and are now held quarterly in New York City.

Tonight from 6:30pm to 9pm, ROOT Drive-In Studios, in Chelsea, will play host to the second installment, which focuses on photography that documents subcultures, featuring Larry Fink, Martha Cooper, Deidre Schoo, Andrew Hetherington, Gillian Laub, Chris Arnade, Stefan Ruiz, and Danny Ghitis. Fink has done iconic documentary work, from capturing the Beats of the 1950s to the blue-blooded society of 1970s Manhattan. Before Ruiz began work on his current series, Cholombianos (about a teenage Mexican countercultural group that styles itself to Cumbia music and culture), Aperture published his book of telenovela photographs, The Factory of Dreams in 2012.

Gillain Laub has spent her career giving voice to diverse and multifaceted communities through photography and filmmaking. Her critically acclaimed book, Testimony, was published by Aperture in 2007. Most recently, Laub has been documenting racially segregated proms of Montgomery County, Georgia in a book and documentary titled Southern Rites.

The first installment took music photography as its theme; as Janette Beckman, Michael Levine, Amy Lombard, and others spoke of photographing musicians and fans, from the early days of hip hop to juggalos. For five to seven minutes, each photographer presents one specific photograph and talks about the moment and story behind their shot.

For more information about the event and ticketing visit theblowupnyc.com.

The post Tonight: The BlowUp Hosts Live Storytelling Event in NYC appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 25, 2015

Announcing the 2015 Summer Open

Monika Sziladi, Untitled (Passing by), 2014

For this year’s Summer Open, Aperture’s annual open-call exhibition, we asked photographers to consider the ways in which our current reality might outpace outlandish narratives of science fiction. The twenty-four projects here, culled from more than 500 and representing diverse subjects and photographic approaches, reflect our current moment. Their concerns run the gamut, from how technology increasingly permeates daily life to off-the-grid communities, the misused landscape, utopian architecture, and the vocabularies of science and science fiction, among other concerns.

Included are photographers Farah Al Qasimi, Fabrizio Albertini, Emmanuelle Andrianjafy, Tine Bek, Arnau Blanch, Anaïs Boileau, Philippe Braquenier, Antoine Bruy, Felix R. Cid, Ben Freedman, Yaeli Gabriely, Alexander Gehring, Aras Gökten, Jeremy Haik, Balarama Heller, Klara Källström and Thobias Fäldt, Vivienne Luo Wang, Jim Mangan, Sarah Meyohas, Dylan Nelson, Brandon Nichols, Eva O’Leary, Martine Stig, and Monika Sziladi.

The exhibition will open on July 16 at Aperture Gallery in New York.

The post Announcing the 2015 Summer Open appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 24, 2015

Zoë Lescaze on Candida Höfer at Sean Kelly Gallery

By Zoë Lescaze

Benrather Schloss Düsseldorf V, 2011.

Benrather Schloss Düsseldorf I, 2011

Neuer Stahlhof Düsseldorf III, 2012

Deutsche Oper am Rhein Düsseldorf I, 2012

Neuer Stahlhof Düsseldorf I, 2012

Neuer Stahlhof Düsseldorf II, 2012

Sankt Maximilian Düsseldorf I, 2012

Julia Stoschek Collection Düsseldorf IVa, 2008. All photographs © Candida Höfer, Köln / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy Sean Kelly, New York

For more than thirty years, the German photographer Candida Höfer has composed scrupulously symmetrical shots of lavish libraries, museums, opera houses, and churches, cataloguing the poetics of interior space over the course of her career. In her first show at Sean Kelly Gallery, From Düsseldorf, Höfer offered an array of palatial rooms from the title city, printed in color at an enormous scale.

Höfer allows her viewers to see these rooms more clearly and coherently than if they were actually there, and the fixed perspective and stillness captures minutiae otherwise missed. One can count the feathers on St. John’s eagle painted on the stairs leading to the elaborate gilded pulpit in Dominikanerkirche Sankt Andreas Düsseldorf (2011), or study the carvings on the ceiling of that vast, visually cluttered church. The absence of human beings makes one uncomfortably conscious of the figurative sculptures adorning these rooms; bare-breasted caryatids smile blankly, while creepy cherubim clutch bouquets and their own plump little bodies. In some cases, Höfer’s exclusion of living subjects makes her viewers acutely aware of their own participation. In Deutsche Oper am Rhein Düsseldorf I (2012), she shoots the opera house from center stage, putting us in the position of a performer standing before an invisible audience in hundreds of empty red seats.

The artist’s coldly documentarian impulse sometimes saps her images of their impact. Perhaps such spaces ought to be recorded for their historical importance, but, as works of art, these photographs don’t explore conceptual territory that Höfer hasn’t already covered in this series. When Höfer plays with the formula, however, the photos sing. The Benrather Schloss, a powder-pink rococo pleasure palace overflowing with frilly decorative details in southern Düsseldorf, looks as though it was spun out of confectioner’s sugar. In one photograph, Höfer lets—or makes—the blinding light blow out part of a polished, intricately inlaid wooden floor. By erasing some of the fussy detail she normally records, Höfer subtly sabotages the decadent space, and her purposeful slip from technical perfection defies our expectations.

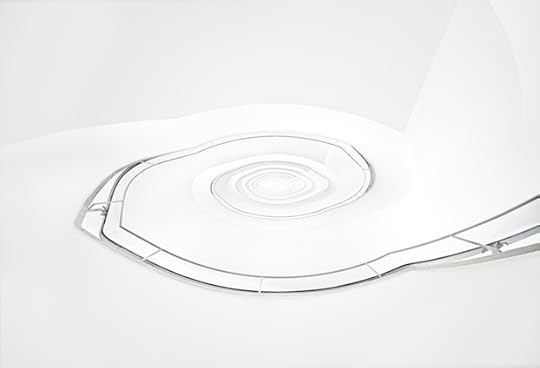

Alongside Höfer’s signature shots of fussily decorated rooms, the show also includes a markedly different body of work, in which she focuses on spare architectural forms in modernist buildings. In place of vast, elaborate chambers captured in all their excess, these works present small portions of windows distorted with reflections, or bits of walls and floors. Several of the wider shots offer asymmetrical glimpses of austere, minimalist spaces, such as an empty German art gallery. Many of these don’t work. A photograph of a few beige steps bearing blue strips of tread in an institutional stairwell feels overly straightforward and banal. Photographs of a spiral staircase, however, are fantastic; other photographers have been drawn to this subject matter for its Fibonacci-fueled grace and seductive vertigo, but Höfer’s pictures abstract the architecture so dramatically that the spiral barely reads as part of a building. Neuer Stahlhof Düsseldorf I (2012), in which the stairs are shot from below, is profoundly disorienting: bright light bathes the smooth white underside of the steps, and the near-monochrome is punctuated only by the serpentine metal banister coiling up to an empty center. The image provides a counterpoint to the artist’s usual practice, introducing a welcome complexity to her understanding of space.

The post Zoë Lescaze on Candida Höfer at Sean Kelly Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 23, 2015

Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Obscura

The following is an excerpt from a portfolio in Aperture magazine #219, Summer 2015, “Tokyo.” This article also appears in Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Tokyo, 2013

Tokyo, 2013

Tokyo, 2014

Tokyo, 2014

Tokyo, 2014

Tokyo, 2014

Takashi Homma emerged in the 1990s as one of the leading photographers of his generation. After living in London, where he worked for the groundbreaking style and culture magazine i-D, Homma embarked on a number of projects of his own, resulting in a sequence of photobooks that engaged Japan’s capital, including Tokyo Suburbia (1998), Tokyo Children (2001), Tokyo and My Daughter (2006), and Tokyo (2008). He became known for his elegantly restrained compositions and understated color, and an aesthetic that seemed to have more in common with that of the American photographers Stephen Shore and Robert Adams than it did with previous generations of Japanese photographers, like Daido Moriyama, whose pictures looked intentionally blurry and distressed. Recently, however, in a radical departure from his earlier work, Homma has begun working with a camera obscura, the proto-form of photography in which an inverted image is projected by light passing through a tiny hole in a wall.

Homma tends to prefer hotels for his camera obscura process: he converts entire rooms in Tokyo into pinhole cameras, blacking out the windows with dark paper and sealing off light leaks with tape. “The concept was to use architecture to take pictures of architecture,” Homma explains. In this way, he’s photographed water towers, city streets, skylines, ordinary subjects that take on an aura of mystery. In some images, large dots eclipse part of the view, like a gothic Japanese flag; in others, the blur is enigmatic, the palette unusual. “Exposing color film to natural light, rather than light through a lens, produces tones I’ve never quite seen before.”

The initial idea, however, was inspired by the work of Nobuo Yamanaka, a conceptual artist working in Tokyo in the 1970s. “Yamanaka, over twelve years, devoted himself to transforming his apartment into a pinhole camera. It made me think of the first daguerreotypes made by Nicéphore Niépce, how they were landscapes visible through the window of his house.”

With this work, Homma is purposely conjuring the past, intrigued by the way the process slows photography down, especially in our digital age of instant-image gratification. Another important touchstone for the work is author Junichiro Tanizaki’s “In Praise of Shadows,” a classic 1933 essay on aesthetics, in which Tanizaki comments on how, in the past, darkness was more a part of everyday life. “Today the world overflows with light,” Homma says. “Creating darkness is itself special. When you make a whole room into a pinhole camera, you move subtly away from the idea that you are taking the picture. It’s not the result of your actions alone and it’s unclear how it will all turn out until the very end.” –The Editors

The post Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Obscura appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Magazine: Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Obscura

The following is an excerpt from a portfolio in Aperture magazine #219, Summer 2015, “Tokyo.” This article also appears in Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Takashi Homma emerged in the 1990s as one of the leading photographers of his generation. After living in London, where he worked for the groundbreaking style and culture magazine i-D, Homma embarked on a number of projects of his own, resulting in a sequence of photobooks that engaged Japan’s capital, including Tokyo Suburbia (1998), Tokyo Children (2001), Tokyo and My Daughter (2006), and Tokyo (2008). He became known for his elegantly restrained compositions and understated color, and an aesthetic that seemed to have more in common with that of the American photographers Stephen Shore and Robert Adams than it did with previous generations of Japanese photographers, like Daido Moriyama, whose pictures looked intentionally blurry and distressed. Recently, however, in a radical departure from his earlier work, Homma has begun working with a camera obscura, the proto-form of photography in which an inverted image is projected by light passing through a tiny hole in a wall.

Homma tends to prefer hotels for his camera obscura process: he converts entire rooms in Tokyo into pinhole cameras, blacking out the windows with dark paper and sealing off light leaks with tape. “The concept was to use architecture to take pictures of architecture,” Homma explains. In this way, he’s photographed water towers, city streets, skylines, ordinary subjects that take on an aura of mystery. In some images, large dots eclipse part of the view, like a gothic Japanese flag; in others, the blur is enigmatic, the palette unusual. “Exposing color film to natural light, rather than light through a lens, produces tones I’ve never quite seen before.”

The initial idea, however, was inspired by the work of Nobuo Yamanaka, a conceptual artist working in Tokyo in the 1970s. “Yamanaka, over twelve years, devoted himself to transforming his apartment into a pinhole camera. It made me think of the first daguerreotypes made by Nicéphore Niépce, how they were landscapes visible through the window of his house.”

With this work, Homma is purposely conjuring the past, intrigued by the way the process slows photography down, especially in our digital age of instant-image gratification. Another important touchstone for the work is author Junichiro Tanizaki’s “In Praise of Shadows,” a classic 1933 essay on aesthetics, in which Tanizaki comments on how, in the past, darkness was more a part of everyday life. “Today the world overflows with light,” Homma says. “Creating darkness is itself special. When you make a whole room into a pinhole camera, you move subtly away from the idea that you are taking the picture. It’s not the result of your actions alone and it’s unclear how it will all turn out until the very end.”

The post Magazine: Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Obscura appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 19, 2015

Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 10:

● An excerpt from Hellen van Meene’s upcoming photobook, The Years Shall Run Like Rabbits by Marin Barnes, senior curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

● A report from Carole Naggar about Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence, an exhibition at Le Bal, Paris

● From The PhotoBook Review 008, Collecting the Japanese Photobook, Part Two: Leslie A. Martin in conversation with Manfred Heiting

● An excerpt from Aperture magazine: Takashi Homma’s Tokyo Obscura

● Aperture staff pick our favorite Instagram accounts

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 16, 2015

Todd Hido: Sources and Influences

“Part of being a photographer is noticing surface details and how they represent something larger; it’s like being a detective or psychologist.” —from Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude (Aperture, 2014)

Cinematic structure, suburbia, Raymond Carver novels, ink-jet printers, Kodak film, and Lightroom: these are just a few of the dozens of topics photographer Todd Hido discussed throughout his two-day workshop, during which he presented personal influences, shared knowledge concerning photography as both fine art and a career, and explained his evolution as an artist. After presenting his work, he led participants in group conversations surrounding their photographs, offering generous, individualized critiques and valuable advice for the development and direction of their portfolios. Hido addressed the importance of following one’s own innate wisdom, explaining, “Work that is rooted in our own personal experience never disappoints.”

“The workshop exceeded my expectations. I received valuable information from both the discussion of Todd’s work and the critiques of the participants.”

“Getting feedback on my portfolio was helpful, but it was also valuable to hear about Todd Hido’s process; the way that he trusted his gut and developed his own unique style, and the ways that he built a career out of creating a particular mood.”

“Todd was open and super generous—answering all questions, taking a lot of time to go through our own work.”

“Todd was a great instructor. For me, it was good to know that everyone faces the same struggles when making and looking for images to photograph.”

—Workshop participants

Todd Hido (born in Kent, Ohio, 1968) is a San Francisco Bay Area–based artist whose work has been featured in Artforum, the New York Times Magazine, Eyemazing, Metropolis, the Face, i-D, and Vanity Fair. His photographs are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Museum, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among other institutions. He has published more than a dozen books, including Excerpts from Silver Meadows (2013). Hido earned a BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, Boston, and an MFA from the California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California, and is an adjunct professor at the California College of Art, San Francisco.

The post Todd Hido: Sources and Influences appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Selected Works Walkthrough

In this video, LaToya Ruby Frazier walks us through her exhibition, LaToya Ruby Frazier: Selected Works at Aperture gallery in New York. In celebration of Frazier’s first book, The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2014), as well as in honor of her recent Infinity Award for Publication (presented by the International Center of Photography) and her Alice Austen Award for the Advancement of Photography, Aperture Foundation presents a selection of photographs and videos related to the publication and to Frazier’s ongoing work.

The 2015 Infinity Award–winning photobook, The Notion of Family is available from Aperture’s online shop.

The post LaToya Ruby Frazier: Selected Works Walkthrough appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 15, 2015

Report from the Shanghai Center of Photography

The newly opened Shanghai Center of Photography promises an ambitious array of photography exhibitions in its inaugural year, from landmark works of the twentieth century to a survey of Chinese contemporary photography. Situated on the West Bund, a new arts district being promoted by the city as a museum and gallery-going destination, the center hopes to introduce modern and contemporary photography of all genres to a city largely devoid of institutions to educate about the medium. Online editor Alexandra Pechman visited Shanghai this May, where the center’s director Rebecca Catching spoke to her about their ambitions, plans, and what it means to open a museum or arts center in China.

Much has been made of China’s museum boom– with hundreds of new venues opening each year–but few have been devoted specifically to contemporary photography, and in Shanghai, there are none at all. In May, the Shanghai Center of Photography opened along what is now called the West Bund Cultural Corridor along the southern bend of the Huangpu River. Here, a loose association of brand-new museums, art centers, and festival grounds have cropped up, devoted to contemporary art and culture. The inaugural exhibition at the Shanghai Center, Photography from the 20th Century: The Private Collection of Jin Hongwei, presents selections from the sixteen hundred-piece collection of Hongwei, a Chinese collector with a formidable trove of twentieth century photography. The small show includes classic works by Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Joseph Koudelka, Elliott Erwitt, and Ansel Adams as well as more contemporary selections from Robert Mapplethorpe, David Hockney, and Sally Mann (Jin primarily collected American photography). “It includes works from photographers who shaped the evolution of the medium from the early days of glass plate photography to contemporary explorations of digital photomontage,” a statement about the show announced.

“China doesn’t really have a dedicated photography center,” director Rebecca Catching said, who began her role just two months ago. “Everyone knows Stieglitz and Steichen as big names, but I don’t know that they know what they did.” There are even a few well-known photographers whose work has provoked conversation. “For instance, Sally Mann is not that well known in China and we have quite a few of her works in this show,” she said. “We had an interesting dialogue with a journalist about it who was saying about how her work is controversial in the States or at least it was at the time, and Mr. Jin said to the journalist said oh yeah it’s controversial because people found it inappropriate to have nude children but in China, a naked child is really not so much of an issue.”

The center does not have a collection but will show a wide range of work from diverse sources, in order to give a comprehensive view of photography to a city that has largely lacked an introduction to the world of photography. The building, designed by US-based architectural duo Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, features elliptical-shaped walls, a triangular courtyard, and skylights that allow slices of light into the white space. Originally intended as a showpiece for the 2013 West Bund Biennial, an architectural biennial sponsored by the city, the space was offered to veteran photojournalist Liu Heung Shing as a studio space, which he had no need for. He then decided to found a photography center instead.

Catching is planning the next show, a survey of Chinese photography, which will to include documentary, landscape, portraiture, conceptual photography, focusing on eight photographers who have a had an impact on the history of photography in China. The exhibition will open during Photo Shanghai in September, while, for 2016, Catching is planning exhibitions of William Eggleston and Boris Mikhailov.

Of the fact that many art exhibitions in China are subject to censorship, Catching said, “Unfortunately we do have to think about these things, especially when it’s our first show.” For example, a tamer selection by Robert Mapplethorpe appears in the exhibition. “If we’re going to do something controversial, we’d like to save it for something where there’s a really tough solo show that we want to do.” While the center’s entryway bears the well-known Susan Sontag quote, “Today everything exists to end in a photograph,” the contemporary embodiments to that statement– Facebook, Instagram, and Google image search, for example– are all blocked in China. Mainly, Catching said, the goal is educate a public that has been relatively isolated from the history of photography, while starting from scratch. “It’s been kind of fast and furious, dealing with roof leaks and renovations while also putting up the first show and also creating a huge amount of material,” said Catching. “It’s been quite an endeavor.”

The post Report from the Shanghai Center of Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers