Aperture's Blog, page 159

May 29, 2015

Behind the Scenes of Emmet Gowin at the Morgan Library and Museum

Joel Smith as told to Alexandra Pechman

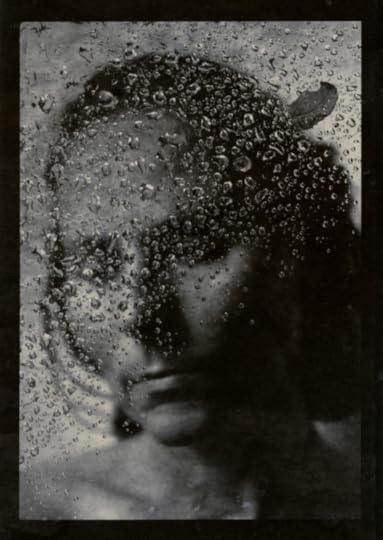

Emmet Gowin, Edith, 2004 (Rain Droplets in a Web). Gold- toned salt print on gelatin coated paper. Collection of Emmet and Edith Gowin. © Emmet and Edith Gowin, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery.

Throughout his prolific career as a photographer, Emmet Gowin has threaded together seemingly disparate subjects: his wife, Edith, and their extended family; American and European landscapes; and aerial views of environmental devastation. In 2013, Aperture copublished a long-awaited survey publication, Emmet Gowin, in conjunction with a related exhibition organized by Fundación Mapfre, Madrid. On May 22, the Morgan Library and Museum opened Hidden Likeness, a show of Gowin’s photographs from throughout his career paired with selections he made from the museum’s vast holdings of ancient Near Eastern seals, medieval books, music manuscripts, and prints and drawings, as well as photographs. Online editor Alexandra Pechman spoke with Joel Smith, Richard L. Menschel Curator and Department Head, Photography, during a tour of the exhibition during its installation in early May. In June, Aperture Foundation Members at the Patron level will have a private tour of the exhibition led by Smith. What follows are a few selections from Smith’s commentary on how the Gowin show came together. This article also appears in Issue 8 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

On the Exhibition’s Beginnings

If you look at an artist’s work and say, “What other work would help to explain their work or bring out themes?” in Emmet Gowin’s case, it would need to be a very rich, long list of things precisely because of the range of things that he does and the depth of each. I’ve known about his great love of William Blake as well as Dürer and Old Masters, so that knowledge infected my eye in looking at his work. What I really wanted to do was to leave those relationships to speak for themselves—not to come up with thematic categories that he had to fit into, but to really have a free-flowing visual relationship between his body of work and the kinds of things that the Morgan has. . . . Emmet started coming in last spring for a day at time, and I made appointments with the curators [in other departments]. Based on their conversations, we could pull things to show. So we wound up with a group of a couple hundred objects and cut down from there to about fifty as we talked about which pieces of his own he wanted to include. In terms of his work, we were trying to choose a large number of [photographs] that had maybe been shown only once, as well as a few that are the anchors that people know.

(Left) Emmet Gowin, Edith and Elijah, Danville, Virginia, 1968. Gelatin silver print. Collection of Emmet and Edith Gowin. © Emmet and Edith Gowin, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery. (Right) Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669), Woman with a Child Descending a Staircase, ca. 1636. Pen and brown ink, brown wash. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Edith

She is a common thread that runs throughout his career, so she appears a number of times in the show. Those portraits you see in combination with, for example, Frank Albert Rinehart’s portrait from an 1898 Indian conference in Omaha, Nebraska [Eneas Michel, Flatheads, 1898], a photograph that I acquired just a couple of years ago. Emmet loved the way the man maintains his dignity even in this totally imposed, unnatural context that’s determined by the photographer…he saw [this] as a common element with Edith. There are portraits of Edith from 1967 all the way up to 2009, paired with Gauguin, Rembrandt, Degas. Happily there is this picture [top] of Edith that is a “hidden likeness”: it’s actually a photograph of a photograph. Emmet made pictures of Edith that he took traveling with him, as a way of bringing Edith along. There had been a rain shower outside on his porch in Pennsylvania, and when he looked out he saw a spider web that had droplets of rain in it and a leaf. He went back in the house and got his camera as well as one of those portraits, and he just slipped it behind the spider web. The web disappeared, and there’s nothing but the water which becomes this veil over her face. So the photograph of her is from maybe ten or twelve years earlier, though this photograph is recent.

(Left) Emmet Gowin, French Guiana, Insect Movement, 2010. Archival digital inkjet print. Collection of Emmet and Edith Gowin. © Emmet and Edith Gowin, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery. (Right) Johann Hartlieb (active 1450), Die Kunst Chiromantia (The Art of Chiromancy). Augsburg: Georg Schapf, ca. 1475. Ink and wash on paper. Purchased with the Bennett Collection, 1902, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Relationships between objects

There are artistic relationships and surprises in the show: there’s a very early Lyonel Feininger academic study that has nothing to do with what he did later as an artist but is formally so beautiful. . . . These fit with the image of the paths of moths and droplets of water on a tent surface in the jungle, from when Emmet was photographing moths in the rainforest [above]. He made a few of these and, in the booklet, we paired this with a palm from a very early printed book. Some of these [moth path] images have never been shown: the cloth of the tent gets wet at night in the rainforest, soaked, and then you can see the moths land on it, droplets of water run down it, you can see the feet of the moth—I love where this one walked in a circle.

(Left) Emmet Gowin, Copper Ore Tailing, Globe, Arizona, 1988. Toned gelatin silver print. Collection of Emmet and Edith Gowin. © Emmet and Edith Gowin, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery. (Right) William Blake (1757–1827), Behemoth and Leviathan (illustration for the Book of Job), ca. 1805–10. Pen and black and gray ink, gray wash, and watercolor, over faint indications in graphite. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909, The Morgan Library & Museum.

Terrible Beauty

William Blake is a favorite of Emmet’s, and I wanted to get [Emmet’s] aerial photographs in from the beginning. These two images [above] are paired at the beginning of the show and both have this demonic beauty to them. . . . We will have an event later in the run of the show on September 10 called “Terrible Beauty,” where Emmet will speak on the subject of beauty in catastrophe. The beginning of [the idea of terrible beauty] can be seen in his views of Matera, Italy, made in 1980, a couple years after an earthquake that made parts of the city uninhabitable. Around the same time he was photographing Mount St. Helens, where he was beginning to have that almost aerial perspective. It was in the course of doing the aerial work that he flew over Hanford [Nuclear Reservation near Richland, Washington] and realized there’s this whole nuclear story in the U.S. to be told through photographs.

The title (Hidden Likeness)

[At the] Morgan, we have not only works of art but all of these other things like books, musical manuscripts, and objects such as Coptic bindings, that are really not there for their visual characteristics at all, but for their historical significance. Those are things I just knew Emmet was going to respond to, and I wanted to do something that would bring out the richness of what the Morgan has; he was an ideal instrument to get at that depth. This title, Hidden Likeness, came about because I asked Emmet if I could look through his old notebooks where he had written quotations down and so on. It was actually the transcript of a talk in which he said, “Jacob Bronowski [biologist, mathematician, and author of The Ascent of Man] would have called this a hidden likeness,” and I didn’t even know what it referred to, but I liked the phrase. It wound up explaining very nicely what I saw here: in the range of what the Morgan has and in the range of what Emmet does, there’s a likeness that nobody meant to produce but was there waiting to be found.

Size and intimacy

Another element of likeness is simply one of scale. The largest thing Emmet has ever created as a photographer is about [handheld] size, and that’s the kind of range in which the Morgan’s collection exists—we don’t have a painting collection, we don’t have sculptures in any great number. There was something about that human scale that felt like an affinity as well. Photography is all sorts of different things now, and for some photographers it’s something electronic and for some it’s something monumental, but Emmet really does work in a tradition that speaks historically to the kind of tradition that the Morgan is about. He works toward a piece of paper, or the size of something you might hold in your hand. That kind of intimate feature of the objects is something I hope that people will experience by seeing the show.

The post Behind the Scenes of Emmet Gowin at the Morgan Library and Museum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 27, 2015

Kikuji Kawada in conversation with Ryuichi Kaneko

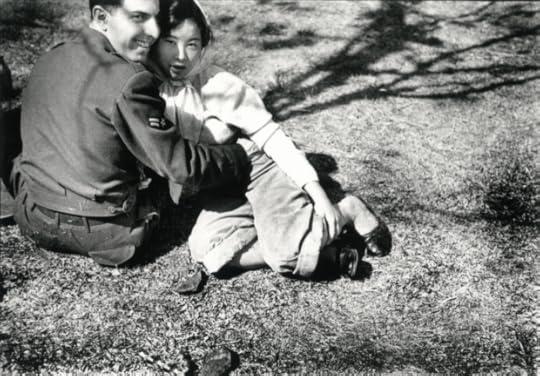

G.I. and a Woman at Ueno Park, 1953

Kikuji Kawada is one of Japan’s most celebrated postwar photographers. In 1959, Kawada—along with Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, and Akira Tanno—founded the influential VIVO cooperative, which championed an expressive approach to documentary photography. He is perhaps best known for his now-iconic 1965 book The Map (or Chizu in Japanese), a disquieting exploration of the trauma of World War II. The book, designed by Kohei Sugiura, features images of stains burnt into the walls of Hiroshima’s A-Bomb Dome (now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial), as well as images related to the iconography of the American occupation. Kawada’s subsequent projects continued his interest in connecting the present with historical touchstones, and shift between realism and abstraction. Kawada, now eighty-two, continues to attract a wide international audience. His photographs were featured in the 2014 exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography, curated by Simon Baker, for London’s Tate Modern, and MACK Books has recently released a volume of The Last Cosmology, Kawada’s project on astrological phenomena. This past January, at Aperture’s request, Kawada met with Ryuichi Kaneko, an influential historian and a major collector of Japanese photography books, at Tokyo’s Photo Gallery International. They discussed the arc of Kawada’s six-decade-long engagement with photography for the Summer 2015 “Tokyo” issue of Aperture magazine. The following is an excerpt of their conversation that focuses on Kawada’s early career and the making of The Map. This excerpt also appears in Issue 8 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Ryuichi Kaneko: I’d like to start by asking what made you become a photographer. What inspired your first forays into photography as an art?

Kikuji Kawada: People ask me all the time what made me decide to be a photographer, but I have to say, I’ve always found it hard to put my finger on it. It was more like one thing led to another, really. I got my first camera in high school. The first time I used it, I got on my bike and rode way out into the mountains, out where no one was around, and ended up taking pictures of some dry grass I found out there. Thinking back now, I have no idea why I did that. I was born in a little town called Tsuchiura—really rural. You could get on your bike and end up in the mountains right away or wander around amid the rice fields.

RK: Most people think of a camera, first and foremost, as a tool for taking pictures of those closest to them. But your first instinct was to go out where there weren’t any people at all.

KK: I liked doing things in secret—maybe not the healthiest predilection, now that I think about it [laughs]. I was interested in playing with mechanical things in secret; it felt like I was accessing the heart of the mechanism that way, its essence. Discovering its secrets.

RK: In the 1950s and ’60s you published frequently in photography magazines; Shincho Weekly, Nippon Camera, and Photo Art—those magazines were your mainstay. Looking back at the photographs you published early on—Yaizu and Fishing Port at Yaizu (1957–59), or The Bar Abandoned by the Boom (1957), or even, to a certain extent, the Base photographs (1953)—did these first run in Shincho Weekly?

KK: Many photographs were taken for magazines but didn’t end up published. They were too strange. Shincho Weekly wanted less edgy themes for the spreads—though some were things I shot on my own time, when inspiration struck. I would stop to shoot something on the way back from an assignment, for example.

Pages from the maquette for The Map (1965) showing the A-Bomb Dome.

RK: [By the late 1950s] you’d become a member of the postwar generation of photographers, and your work was getting a fair amount of attention. But there’s one series I really must ask you about from this time: when you went to Hiroshima. That was with Domon, right? [Ken Domon, the influential documentary photographer of this period.]

KK: It was. I’ve talked about this ad nauseam over the years, but long story short: I proposed a trip to Hiroshima to the editorial board of Shincho Weekly, a documentary shoot, and it was approved. I was excited at the prospect of going, but it was decided that it would have to be a special issue, and in that case it should be Domon who went. That was an order from the top. So, my hopes were dashed in an instant. The people who ended up going were Domon and [freelance journalist] Daizo Kusayanagi. They were charged with gathering evidence under the auspices of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission. It became a huge special issue. And Domon ended up going back and forth to Hiroshima many times during the process of shooting what would become the book Hiroshima (1958). The editor at Shincho was paying for these trips out of his own pocket, and at one point he said to me that he knew I’d been the one to propose the project but that I’d never gotten a chance to go, so he was going to send me along as an assistant. So, it was as Domon’s assistant that I ended up going. That was my first trip to Hiroshima.

RK: How many times did you end up going with him?

KK: Just once. Domon liked the finer things. He wanted to stay at the very best place in town, so we ended up in a new hotel and would walk to the Peace Park and the A-Bomb Dome, which were nearby. We would go together, but then I’d slip away and walk around on my own. And that’s when I found them: the stains on the walls of the rooms beneath the dome that became the subject of the Stain series. I would just slip away, secretly, without a word to Domon.

Pages from the maquette for The Map (1965) showing the Stain series

.

RK: So, there were rooms underground, beneath the dome?

KK: When the place was destroyed, there were about thirty people—I think it was around eight in the morning or so, but at any rate, in the morning—these people had arrived for work and ended up vaporized. The place had a horrible atmosphere. Just looking at it was overwhelming. And you couldn’t see very well; there were no lights, no electricity. So, I left and gathered up a big camera and some bulbs and headed back.

RK: So, that’s how you first discovered that place?

KK: Yes. This was going to be my Hiroshima. I could take so many kinds of pictures there. This was no longer assistant’s work; I was preparing my own project. I wasn’t thinking about anything else.

RK: You said you brought back a big camera. Do you mean a 4 by 5? And lights to illuminate the rooms?

KK: It was a 4 by 5, yes. But I didn’t use lights; I shot in natural light. Back then, we could go in and out of the dome as we liked. In the Tate Modern book [Conflict, Time, Photography, 2014], there’s that famous photograph of Kiyoshi Kikkawa, who was called genbaku ichi-go [bomb victim number one]. He ran a souvenir stand right next to the dome.

RK: I’ve heard you talk before about discovering those “stains” beneath the dome, and when I think about how they may be all that was left of people who were vaporized in an instant, all the hair on my body stands on end. You hear about things like that: people explain what happened as carefully as they can—this happened, that happened, like that. But there’s no comparison to seeing it as one image. It has so much power.

KK: The hard part becomes how to organize that kind of material, how to convey its enormity.

RK: You published some of those photographs in Nippon Camera under the title The Map: Stain. That was August 1962. Was that their debut?

KK: I think so. After the Eyes of Ten exhibition (1957), there was another show, NON, at the Matsuya Ginza Gallery (1962). I showed many of the Stain pictures there—about ten pieces in all, I think. That was the first time I’d put together a fair amount of them as one exhibition. Eikoh Hosoe debuted the first of his Ordeal by Roses photographs there, too. We had a lot of people coming to that show including Yukio Mishima, of course, since he was Hosoe’s model. I overheard him asking, “What kind of ‘stains’ are these? Stains left by what?” I was a bit contrary back then, you know. I said, “That’s for you to imagine, sir” [laughs]. Though I did think you should be able to tell just by looking.

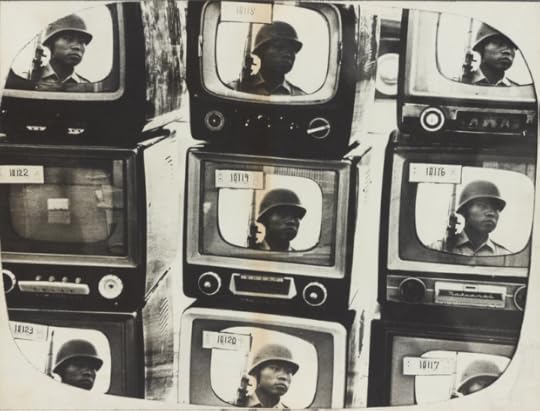

RK: When looking through The Map, the first thing that makes an impression is of course the A-Bomb Dome photographs—the Stain photos—and then the other images of what you might call “scars of war.” But there are other images, too, like the spiral lathe left for scrap in a factory or a wanted poster related to a heinous crime, or a bank of television screens—all sorts of images. So, history is brought into direct contact with the present.

Pages from the maquette for The Map (1965)

KK: An image taken of the “present,” whenever that is, is so strong—vivid in hue, aspect, substance—because it’s a document. I seek even now to explore new forms for documentary to take. When you layer things in the way we’ve been discussing, the layers produce meaning, metaphors emerge as you go deeper into the juxtapositions that arise, and the ways of seeing the image multiply. Not because it’s a collage, because you have layers, like this [indicates the accordion shape of a camera bellows].

RK: I understand that when it came time to actually make the book, there were a lot of complications on the road from the dummy version to its final form. You were unable to put it out as you first envisioned it, in two volumes, and instead everything had to be layered physically into one volume.

KK: That was the plan proposed by our fantastic designer, Kohei Sugiura—to split The Map in two. On the one hand, there were the Stain photographs; they added up to a good proportion of the whole. Then there were the other photographs, the Hinomaru flag photograph, the monuments, the more symbolic stuff. We split these photographs into two volumes—half in one, half in the other—and we’d put them in one case. So, the viewer would have to take them out and look at one volume, then open the other. So, it was only in their heads that the whole “map” ever existed. It was so creative, this idea. But I thought it was too hard to understand. Someone buying the thing would have to realize that he has to look at one volume and then another just to figure out what’s going on. It’s too much trouble.

Pages from the maquette for The Map (1965). Photographs © Kikuji Kawada and courtesy Photo Gallery International, Tokyo; maquette spreads courtesy Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Anyway, to skip to the end of the story, it was decided that the thing was too big—it would be too expensive—so we had to make it smaller. To make it smaller, we decided it should fold out on every page—Kannon-style [referring to the Buddhist goddess of mercy], they call it, with the hinged doors. Sugiura asked how many pages we should make that way. I thought, if we go that way, we should go all the way. With a triptych, when you fold the sides over a central image, what’s hidden becomes a sacred icon. That’s the meaning of that design—exactly what the Japanese term means, like opening an altar to view an image of Kannon. So, we redesigned every page that way, and it took about a year or so to do it.

RK: The Map came out in 1965, on the twentieth anniversary of the end of the war, and it was talked about quite a bit. Though, I gather it didn’t sell that well?

KK: I was afraid it might be passed over entirely, so I took a copy to each publication that ran real criticism. I took the book physically to their offices, right to the writers. I remember one guy, Hiroshi Iwada, the poet. He wrote something in the newspaper Nihon Dokusho Shimbun. And then there was Tatsuhiko Shibusawa [a novelist and critic]; I got him to write something somewhere, too. So, word trickled out like that, and as far as critical opinion was concerned, people thought it was a pretty great thing.

RK: You called the work you did before The Map “symbolic documentary,” Ikko Narahara’s Human Land photographs were eventually called a “personal document,” and Eikoh Hosoe called Kamaitachi a “memory document.” Shomei Tomatsu never used the term, but in the end, it seemed to me that this generation of photographers considered all photography to be “documentary.”

KK: We had no strong consciousness of it. I mean, we never debated things in those terms, but I know what you’re saying. Now that I hear you say it, I can’t help but think, Yes, that’s exactly it!

The post Kikuji Kawada in conversation with Ryuichi Kaneko appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 26, 2015

Issue 8 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Inside issue 8, our readers can find:

● A conversation between celebrated Japanese photographer Kikuji Kawada and historian of the Japanese photobook Ryuichi Kaneko, on The Map

● A review of Tate Britain’s first-ever exhibition to focus on a living photographer, Nick Waplington’s photographs of Alexander McQueen, Working Process

● From the latest issue of The PhotoBook Review: Max Pinckers’ Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

● A look inside Richard Misrach’s new book, The Mysterious Opacity of Other Beings

● A behind-the-scenes look at Emmet Gowin’s exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 8 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 21, 2015

If You Came Here to Have Fun, You Will

Jason Fulford is known not only for his work as a photographer and publisher of J&L Books, but also for going beyond the standard format of a book talk or signing and creating, instead, live performances or happenings that are playful and memorable. Denise Wolff, an editor in Aperture’s books program, has worked with Fulford on two recent books: The Photographer’s Playbook and This Equals That, both Aperture, 2014. Over the course of a year, Fulford and Wolff organized a series of events that involved activities, games, merchandise, flags, a live show, pancakes, and even a debate—all to bring new dimensions to the books themselves. If you ever receive a packet of mushrooms, a letter from the past (or future), or a ticket in the mail with no other explanation, it probably has Fulford’s telltale Scranton, Pennsylvania, return address. Do not discard it; event information will follow. Fulford has a letterpress in his basement and makes much of the ephemera and mailings himself, and with his wife, Tamara Shopsin. These are all part of the experience. For the new issue of The PhotoBook Review 008, Spring 2015, Fulford and Wolff discussed the parallel lives of a book through its events, and the event as intersection of artist and viewer. This article also appears in Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Photogram and letterpress card from the In the Dark and Behind a Wall event at Dexter Sinister, New York, March 26, 2011—the second installment of The Mushroom Collection after the Amsterdam storefront. Visitors passed small objects through a slot in the wall. The objects were converted into light and passed back through the slot.

Denise Wolff: I’ve never known you to do a standard artist talk or panel. Have you?

Jason Fulford: I give talks at universities about four times a year. I don’t like panels though. My talks are scripted so I can put in a lot of information. Then we do Q&As after. I want the audience to get their money’s worth. When I’ve been on panels in the past, I’ve left thinking the audience got cheated somehow. I’ve seen a few good panels though, where personalities clashed, and that is good content.

Hotel Oracle key tags from the New York City event at the New Yorker Hotel, October 2013. The event took place in the Tesla Room, number 3327 on the thirty-third floor, where Nikola Tesla—an inventor, electrical and mechanical engineer, and futurist—lived for the last ten years of his life.

DW: Maybe we should talk about a few of your favorite events. These are the ones I remember: the J&L variety show, the Mushroom Collector darkroom with Dexter Sinister, the Hotel Oracle world tour, the This Equals That pancakes and game, and of course, the Photographer’s Playdate festival of assignments. Are there one or two you can walk us through in particular?

JF: When my book The Mushroom Collector came out in 2010, Lorenzo de Rita, my editor and publisher of the Soon Institute, rented a storefront space in Amsterdam for one month. Our idea was to transform the book into four dimensions, bringing it into time. The space became a cross between a store and a period room. We channeled the anonymous mushroom collector who took the vintage pictures that appear in the book, and imagined what his or her workspace would feel like. Every night something in the room changed, similar to the way mushrooms appear overnight. Over the course of the month, we programmed talks and screenings and music events with different artists.

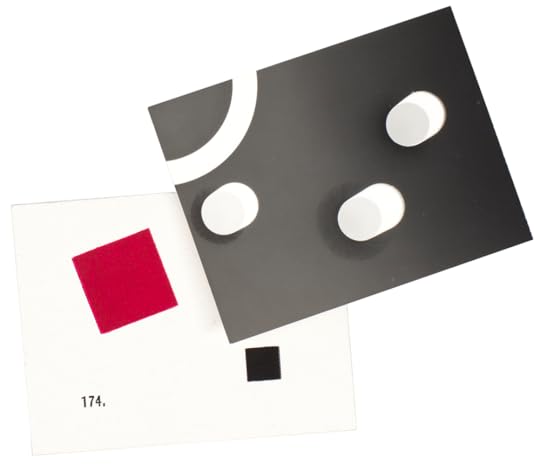

Engraved translucent plexiglass triangles that appeared overnight in the Mushroom Collection storefront space in Amsterdam, 2010. Each triangle is an optical illusion. Most people read this arrangement of words as “I love Paris in the springtime.” Look again.

Back in New York, Dexter Sinister invited me to present the book in their basement space on Ludlow Street. We turned the basement into a one-day darkroom, and built a Malevich-inspired wall. Visitors were invited to bring an object and pass it through the wall, where I converted it into light and removed one dimension by making a photogram. Each visitor received the object back in its new form: a matte barite print. I made about 150 prints that afternoon. We were really sweating behind the wall, listening to Mississippi Records and eating Clif bars.

Around the time Hotel Oracle came out in 2013, Lorenzo and I were having a conversation about the French writer Georges Perec. He wrote an essay describing the perfect Parisian apartment. Each room was in a different neighborhood, in a different type of building, on a different floor, etc.—each location well-suited to the function of the room. It occurred to us that the Hotel Oracle exists all over the world, in pieces, like Perec’s apartment: the room in New York, terrace in Paris, game room in Tokyo, bar in Krakow, laundry in San Francisco, pool in Los Angeles, shuttle van in Philadelphia, and wine cellar in Milan.

Button worn by the eighty-year-old “Future Jason” at the Hotel Oracle pool event in Los Angeles, February 2014. Participants were sent on a self-guided tour through time and asked to find Fulford three times in the historic, ten-floor Los Angeles Athletic Club. The three Jasons were different ages—ten, forty, and eighty—and each signed the book with a different date: 1983, 2014, and 2053.

DW: These events and happenings take a lot of planning, work, and imagination. Why do a book event this way? It seems to be about more than selling and promoting the book. Is it about creating a live experience of the book for an audience? Is it more of an excuse to have a good time? How did the event madness begin?

JF: The Mushroom and Oracle events began as book parties. But wine and cheese and stacks of books are boring. I want the events to be custom-made for the books—to take ideas from the books, and turn them into experiences. In this way the events become supplementary to the books. They’re like appendixes. They’re parallel to the book. They feel like the book. They’re also an excuse for me to play with other materials—architecture, sound, objects. They’re a chance for me to meet my readers one-on-one, which hardly ever happens otherwise.

DW: I really like the idea of the author and reader meeting each other. What was really odd is that, even though I know you, when I “met” you at the Hotel Oracle events in New York and San Francisco, I felt it was an encounter with—well, not quite a stranger, but someone else: the oracle. Did you feel you became an oracle for the event?

JF: That’s great. I’m glad it felt that way. One thing I learned about being an oracle is that equal work is done by the people who receive the message. They are the ones who bring meaning to it. I think that’s also the ideal situation when someone reads one of my books. I want the readers to think about their own lives—not mine.

Hotel Oracle drink coaster from the bar event in Krakow, Poland, June 2014. The Hotel Oracle is a phantom building that appeared in various parts of the world between October 2013 to June 2014—as a room in New York, a bar in Krakow, a terrace in Paris. The events in each location explored themes from the book (such as myth, time, travel, existence, and the supernatural) through performance and interaction. As of June 2014, the hotel is closed.

DW: Do you have a good story or two about meeting your readers? Were there tears? Laughter?

JF: During the San Francisco Oracle event, I met visitors one-on-one in a dark room lit with a red bulb. I asked each person to think of something that was happening in their life at that moment, then to pick from a pile of cards. The message on the card would then relate to the thing they were thinking about. Almost all of the exchanges were intense. Some people left happy, and others more somber. In New York and Paris we did a similar exchange, but with a slide image instead of a card. The slide related to their thoughts. I’ve seen some of the people a year later, and they still remember their fortune.

DW: I remember my slide fortune was about a place called Taco Land. I do feel it was perfect for me and fit well for the whole of 2014. Long live Taco Land! What the hell was that a picture of any way? Can you reveal?

JF: That’s a teletype machine I shot at the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting outside Minneapolis.

The Mushroom Collector mailing that went out in advance of the book’s release in 2010. The Mushroom Collection project began with a set of photographs of wild mushrooms found at a flea market.

DW: Do you want to say anything about the mail? This seems to be part of the fun, and is a bit mysterious (kind of like the events themselves). Do you have more to say on this?

JF: I think we’re OK, but maybe you could mention getting the ticket in the mail?

DW: I received the ticket, which said, “If you came here to have fun, you will!! If not, you won’t!!!”, along with a single sheet of Hotel Oracle stationary. I don’t think it said what it was for or who it was from, but I knew you were behind it and that the information would follow. It was inevitable that I would go to something involving a mysterious ticket received in the mail. Who could resist? The rest is Taco Land history. Maybe I should also ask: what do you think makes a great event?

JF: It’s fun and it makes you think. Maybe you go away with something (physically). And maybe it doesn’t fully make sense until the next day or later.

Tap here to find more from The PhotoBook Review.

The post If You Came Here to Have Fun, You Will appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

If You Came Here to Have Fun…

Photogram and letterpress card from the In the Dark and Behind a Wall event at Dexter Sinister, New York, March 26, 2011—the second installment of The Mushroom Collection after the Amsterdam storefront. Visitors passed small objects through a slot in the wall. The objects were converted into light and passed back through the slot.

Jason Fulford is known not only for his work as a photographer and publisher of J&L Books, but also for going beyond the standard format of a book talk or signing and creating, instead, live performances or happenings that are playful and memorable. Denise Wolff, an editor in Aperture’s books program, has worked with Fulford on two recent books: The Photographer’s Playbook and This Equals That, both Aperture, 2014. Over the course of a year, Fulford and Wolff organized a series of events that involved activities, games, merchandise, flags, a live show, pancakes, and even a debate—all to bring new dimensions to the books themselves. If you ever receive a packet of mushrooms, a letter from the past (or future), or a ticket in the mail with no other explanation, it probably has Fulford’s telltale Scranton, Pennsylvania, return address. Do not discard it; event information will follow. Fulford has a letterpress in his basement and makes much of the ephemera and mailings himself, and with his wife, Tamara Shopsin. These are all part of the experience. For the new issue of The PhotoBook Review 008, Spring 2015, Fulford and Wolff discussed the parallel lives of a book through its events, and the event as intersection of artist and viewer. This article also appears in Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Denise Wolff: I’ve never known you to do a standard artist talk or panel. Have you?

Jason Fulford: I give talks at universities about four times a year. I don’t like panels though. My talks are scripted so I can put in a lot of information. Then we do Q&As after. I want the audience to get their money’s worth. When I’ve been on panels in the past, I’ve left thinking the audience got cheated somehow. I’ve seen a few good panels though, where personalities clashed, and that is good content.

Hotel Oracle key tags from the New York City event at the New Yorker Hotel, October 2013. The event took place in the Tesla Room, number 3327 on the thirty-third floor, where Nikola Tesla—an inventor, electrical and mechanical engineer, and futurist—lived for the last ten years of his life.

DW: Maybe we should talk about a few of your favorite events. These are the ones I remember: the J&L variety show, the Mushroom Collector darkroom with Dexter Sinister, the Hotel Oracle world tour, the This Equals That pancakes and game, and of course, the Photographer’s Playdate festival of assignments. Are there one or two you can walk us through in particular?

JF: When my book The Mushroom Collector came out in 2010, Lorenzo de Rita, my editor and publisher of the Soon Institute, rented a storefront space in Amsterdam for one month. Our idea was to transform the book into four dimensions, bringing it into time. The space became a cross between a store and a period room. We channeled the anonymous mushroom collector who took the vintage pictures that appear in the book, and imagined what his or her workspace would feel like. Every night something in the room changed, similar to the way mushrooms appear overnight. Over the course of the month, we programmed talks and screenings and music events with different artists.

Engraved translucent plexiglass triangles that appeared overnight in the Mushroom Collection storefront space in Amsterdam, 2010. Each triangle is an optical illusion. Most people read this arrangement of words as “I love Paris in the springtime.” Look again.

Back in New York, Dexter Sinister invited me to present the book in their basement space on Ludlow Street. We turned the basement into a one-day darkroom, and built a Malevich-inspired wall. Visitors were invited to bring an object and pass it through the wall, where I converted it into light and removed one dimension by making a photogram. Each visitor received the object back in its new form: a matte barite print. I made about 150 prints that afternoon. We were really sweating behind the wall, listening to Mississippi Records and eating Clif bars.

Around the time Hotel Oracle came out in 2013, Lorenzo and I were having a conversation about the French writer Georges Perec. He wrote an essay describing the perfect Parisian apartment. Each room was in a different neighborhood, in a different type of building, on a different floor, etc.—each location well-suited to the function of the room. It occurred to us that the Hotel Oracle exists all over the world, in pieces, like Perec’s apartment: the room in New York, terrace in Paris, game room in Tokyo, bar in Krakow, laundry in San Francisco, pool in Los Angeles, shuttle van in Philadelphia, and wine cellar in Milan.

Button worn by the eighty-year-old “Future Jason” at the Hotel Oracle pool event in Los Angeles, February 2014. Participants were sent on a self-guided tour through time and asked to find Fulford three times in the historic, ten-floor Los Angeles Athletic Club. The three Jasons were different ages—ten, forty, and eighty—and each signed the book with a different date: 1983, 2014, and 2053.

DW: These events and happenings take a lot of planning, work, and imagination. Why do a book event this way? It seems to be about more than selling and promoting the book. Is it about creating a live experience of the book for an audience? Is it more of an excuse to have a good time? How did the event madness begin?

JF: The Mushroom and Oracle events began as book parties. But wine and cheese and stacks of books are boring. I want the events to be custom-made for the books—to take ideas from the books, and turn them into experiences. In this way the events become supplementary to the books. They’re like appendixes. They’re parallel to the book. They feel like the book. They’re also an excuse for me to play with other materials—architecture, sound, objects. They’re a chance for me to meet my readers one-on-one, which hardly ever happens otherwise.

DW: I really like the idea of the author and reader meeting each other. What was really odd is that, even though I know you, when I “met” you at the Hotel Oracle events in New York and San Francisco, I felt it was an encounter with—well, not quite a stranger, but someone else: the oracle. Did you feel you became an oracle for the event?

JF: That’s great. I’m glad it felt that way. One thing I learned about being an oracle is that equal work is done by the people who receive the message. They are the ones who bring meaning to it. I think that’s also the ideal situation when someone reads one of my books. I want the readers to think about their own lives—not mine.

Hotel Oracle drink coaster from the bar event in Krakow, Poland, June 2014. The Hotel Oracle is a phantom building that appeared in various parts of the world between October 2013 to June 2014—as a room in New York, a bar in Krakow, a terrace in Paris. The events in each location explored themes from the book (such as myth, time, travel, existence, and the supernatural) through performance and interaction. As of June 2014, the hotel is closed.

DW: Do you have a good story or two about meeting your readers? Were there tears? Laughter?

JF: During the San Francisco Oracle event, I met visitors one-on-one in a dark room lit with a red bulb. I asked each person to think of something that was happening in their life at that moment, then to pick from a pile of cards. The message on the card would then relate to the thing they were thinking about. Almost all of the exchanges were intense. Some people left happy, and others more somber. In New York and Paris we did a similar exchange, but with a slide image instead of a card. The slide related to their thoughts. I’ve seen some of the people a year later, and they still remember their fortune.

DW: I remember my slide fortune was about a place called Taco Land. I do feel it was perfect for me and fit well for the whole of 2014. Long live Taco Land! What the hell was that a picture of any way? Can you reveal?

JF: That’s a teletype machine I shot at the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting outside Minneapolis.

The Mushroom Collector mailing that went out in advance of the book’s release in 2010. The Mushroom Collection project began with a set of photographs of wild mushrooms found at a flea market.

DW: Do you want to say anything about the mail? This seems to be part of the fun, and is a bit mysterious (kind of like the events themselves). Do you have more to say on this?

JF: I think we’re OK, but maybe you could mention getting the ticket in the mail?

DW: I received the ticket, which said, “If you came here to have fun, you will!! If not, you won’t!!!”, along with a single sheet of Hotel Oracle stationary. I don’t think it said what it was for or who it was from, but I knew you were behind it and that the information would follow. It was inevitable that I would go to something involving a mysterious ticket received in the mail. Who could resist? The rest is Taco Land history. Maybe I should also ask: what do you think makes a great event?

JF: It’s fun and it makes you think. Maybe you go away with something (physically). And maybe it doesn’t fully make sense until the next day or later.

Tap here to find more from The PhotoBook Review.

The post If You Came Here to Have Fun… appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 20, 2015

Tokyo Aperture #219 – Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #219, Summer 2015. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Takashi Homma, Tokyo, 2015

Tokyo conjures a distinctive, if familiar, image: hyper-modern and kaleidoscopic, a mutating urbanscape that is more Blade Runner than picturesque capital. Like any iconic city, Tokyo also exists in our mind’s eye as an idea. But Noi Sawaragi, one of Japan’s most influential art critics, speaking of the capital in these pages, punctures the idea that this ever-changing place can be neatly encapsulated. “Is Tokyo even a city at all?” he challenges, before reflecting on its diverse culture of image making. “There is very likely a connection between this lack of substance in Tokyo as a city and the scarcity of any single overarching theme or style that might define its photographic expression.”

That diversity of expression is felt across this issue, Aperture’s second to focus on photography through the lens of a global city. While interest in Japanese photography is always strong, a number of major exhibitions on the subject are now being staged internationally (or will be in the near future). Once again, it is a photo-zeitgeist. To create this issue we spent three weeks last December working in Tokyo with editor and publisher Ivan Vartanian, our consultant and guide. We met with photographers, curators, editors, booksellers, and historians to glean a sense of what people in Tokyo’s photography community were talking and thinking about, and what kinds of research and curatorial work were under way. The geography of the city is not simply depicted in these pages but is present as a central character in narratives of photography. As Vartanian commented in a conversation while we finalized the issue, “You might say that Tokyo infuses every body of work coming out of Japan.”

We have tried to characterize the photographic enterprise of the city by reflecting a range of work—some is explicitly connected to the city itself, other projects take us further afield, and a significant offering takes us into the past. We take a deep look at the work of Takuma Nakahira, the Provoke-era photographer and writer who is key to grasping Japanese postwar photography; we consider the role of the medium in Tokyo’s avant-garde scene that emerged amid the social turbulence of the 1960s; we revisit the mass-market, and at times lowbrow, glossy magazines that for decades were the platform for serious photographers. And then we turn to younger generations of image makers, such as newcomers Daisuke Yokota and Mayumi Hosokura, as well as midcareer figures like Rinko Kawauchi and Takashi Homma, both of whom display their evolving curiosity with their most recent projects—published here for the first time—which, for each of them, mark a departure from earlier series. Homma, featured on our cover, now makes foreboding images of Tokyo’s urbanscape using a camera obscura.

Like the city itself, the photography world in Tokyo is a vast and shifting landscape. A single issue can only hope to scratch the surface. Our concurrent edition of The PhotoBook Review, also dedicated to photography from Japan, helps us expand the conversation, and addresses the key role that books play in Japanese photographic culture—including a look at the crop of publications made in response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and Fukushima nuclear disaster. Additional articles will appear on Aperture.org and on the Aperture Photography App—among them an introduction to the thriving scene of alternative spaces that are helping to shape photography in Tokyo today, as well as other related stories and images from our archive. As writer Hideo Furukawa observes of Tokyo in this issue: “the city [is] formed…from an accumulation of tiny, fascinating details.”

—The Editors

The post Tokyo

Aperture #219 – Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 18, 2015

On Chance and Photography

By Robin Kelsey and Samuel Ewing

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Open Door, 1844. Courtesy Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York

To what degree is photography dependent on chance? If photography is a chance operation, are the intentions of the photographer undermined? Robin Kelsey, Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography at Harvard, and a regular contributor to Aperture magazine, tackles these and other questions in his new book, Photography and the Art of Chance (Harvard, 2015). Here he speaks with Samuel Ewing, a graduate student in art history at Harvard, about chance in relation to the work of Julia Margaret Cameron, Alfred Stieglitz, John Baldessari, and others, as well as on how chance itself led him to write a book on the subject. This article also appears in Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

Samuel Ewing: You raise the point in the introduction that chance and its history have remained neglected issues within most photographic scholarship. I understand that a desire to fill in and understand these blind spots drives research, but it so often happens that chance, luck, or serendipity play a major role in even locating the blind spots to begin with. How did you initially “chance upon” this subject?

Robin Kelsey: Back in 2000, I was finishing up my dissertation on the survey photography of Timothy O’Sullivan and wrestling with how the photographs related to other survey modes of grasping the American West graphically—topographic sketching or cartography or verbal description. I thought Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844) might help, because Talbot had to locate his newly invented photographic process in relationship to other modes of representing things. As often happens with great texts or works of art, however, I went looking for one thing and found another. As I read Talbot, it occurred to me that he was struggling brilliantly with an issue to which I had never given much thought, namely, the role of chance in making photographs. Is stumbling on a pleasing arrangement in the world the same as composing one from the imagination? Do the unintended details of a photograph speak on their own behalf? These questions troubled Talbot and, as I later discovered, some other great practitioners as well. So even before I had finished my first book-length project, the second had begun.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Loch Katrine, 1844. Courtesy Hans P. Kraus Jr., New York

SE: The principal photographers in the book—William Henry Fox Talbot, Julia Margaret Cameron, Alfred Stieglitz, Frederick Sommer, and John Baldessari—all have a rather substantial amount of scholarship already dedicated to them. Do you think your argument that chance plays a constitutive and often ambivalent role in photography would change had you focused on lesser-known subjects?

RK: What binds the figures featured in the book is their self-conscious grappling with the relationship of photography to art. For each of them, this grappling required addressing the troublesome role of chance in photography, and each addressed this role in terms responsive to his or her day and circumstances. When Cameron practiced, Victorians were very concerned that modern markets were making investment akin to gambling, and she treated photography as a kind of aesthetic speculation. Stieglitz was more interested in the spontaneous accidental forms of vapors and clouds and scenes on the urban street.

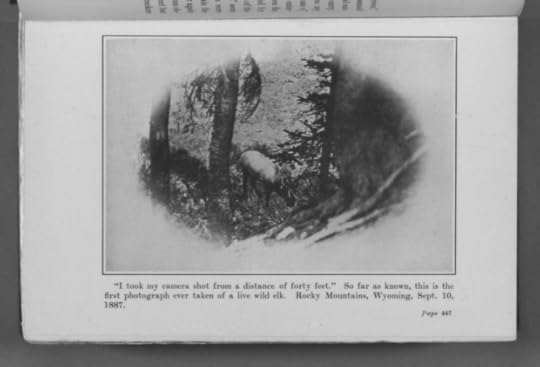

Anthony Weston Dimock, “I Took My Camera Shot from a Distance of Forty Feet,” 1887, from Wall Street and the Wilds. Courtesy Widener Library, Harvard University

SE:Since you mentioned Stieglitz, maybe we can talk about his image taken during the winter of 1892–93, Impression, which I assume to be one you consider really good since you write about it at length. The scene it depicts seems resolutely foreign today—a boy feeding wood into an asphalt paver’s stove—and yet you make the case that the image is redolent with “the alchemy of modern life.”

RK: It’s a great photograph, at least in my view. With Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893) and The Terminal (1893) receiving so much attention over the years, it puzzles me that Stieglitz’s grittier street photographs from that same winter have received so little. To understand the modernism of these pictures you have to remember that rustic labor was a favorite subject of pictorialists at the time. Haying, washing by the stream, that sort of thing. Often taken in a misty setting to give the picture a poetic feeling. Stieglitz knew that such rustic scenes just couldn’t be done in America the way they were done in Europe. So he turned his camera on urban labor, substituting the smoke and steam of machines for the vapors of brooks and fens. Asphalt paving was a perfect subject, because the bicycle craze was underway, and smoother roads were all the rage. With Stieglitz using a new hand-held camera, the picture was all about mobility and change. The result was a radically new pictorialism, one more open to spontaneity and chance.

Experiencing these modern dimensions of the picture today requires bringing all this to mind. It also requires remembering that Impression was primarily shown in the 1890s as a projected lantern slide. Although I have looked long and avidly at the slide of Impression in the George Eastman House on a light table, where it looks much more radiant and atmospheric than it does when reproduced on a page, I have never seen it projected. So, like everyone else, I must use my imagination!

Julia Margaret Cameron, Vivien and Merlin (from Idylls of the King), 1874. Courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University

SE: You use the word glitch to describe the imperfections found in Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs. I associate glitch more often with computers and digital images—corrupted jpg files, for example—than with the wet photographic chemistry used by Cameron. Were you thinking at all about contemporary digital chance while writing about these earlier figures?

RK: In a sense, yes. Glitch is, as you say, associated with electronics and seems to date from the 1960s. Using it in the context of Cameron was a conscious anachronism. I wanted a word that could grab the diverse and unpredictable process-based irregularities in her work—irregularities of focus, of emulsion application, of printing. What I liked about glitch was its suggestion of a systemic irregularity with a mysterious or autonomous origin. Words such as error or defect or mistake just didn’t do the trick. The ambiguity about origin—that is, whether Cameron was simply technically deficient or whether she cultivated the spontaneous flaw—is crucial to the power of her work. Her photography aims for ideals, while insisting that they will never be reached. A quintessential Victorian contradiction! Because what Cameron was fighting was a notion that photography was too mechanical to be an art, a word associated with mechanical breakdown seemed appropriate.

SE: It seems that mechanical breakdowns, though, pose less of a problem when camera technologies become more commercialized, regularized, and refined, especially when your story progresses into the twentieth century.

RK: That’s right. Cameron portrayed herself as an experimentalist, reinventing the medium in a messy, makeshift fashion. By the end of the nineteenth century, after Kodak has arrived, the game changes. Much of the role of chance migrates from the processing phase to the moment of exposure. That moment was always prone to chance—in the long exposures of early photography, a dog might wander in a street scene, or a young portrait subject might sneeze and blur the image. But with fast shutters and films, the so-called instantaneous photograph arrives, and chance takes on a new prominence in composition—to the point that even the word composition seems questionable. In the book, I spend some time discussing a remarkable example of that: Joe Rosenthal’s famous photograph of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima, the beautiful appearance of which came as a complete surprise to him. Most every snap-shooter has experienced something similar. What happens when chance plays a key role in determining the specifics of pictures? Have we honestly dealt with the implications? Or do we like to imagine some kind of mysterious intentions or meaning behind the accidents of everyday form?

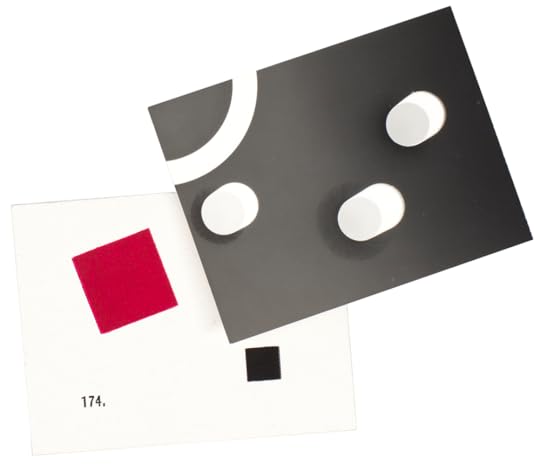

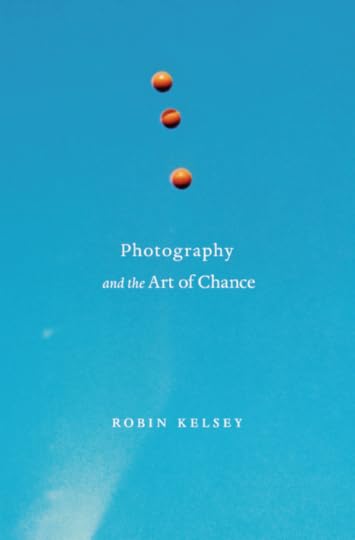

Robin Kelsey, Photography and the Art of Chance, (Harvard, 2015). The cover features an image by John Baldessari

SE: The final figure in your book, John Baldessari, seems to build chance directly into the production of his pictures, often in the form of a game—a new photographic gambit. In the book, you write: “Just as Talbot, Cameron, Stieglitz, and Sommer had done before him, Baldessari found aesthetic possibility in a new historical meaning of chance.” What kinds of historical meanings are found at the intersection of chance, games, and photography in the 1970s?

RK: The changing meaning of chance over the past two centuries is crucial to the book. During the Cold War, chance became a tool of research. Specialists in the military-industrial complex used randomization to grapple with systems too complex to reduce to precise calculation. Games and simulations enabled designers of hydrogen bombs and conflict analysts of the RAND Corporation to grapple with an increasingly complex world. Many schoolchildren of the period, including me, spent many hours playing educational games modeling urban development, global diplomacy, or what have you. This surge of interest in gaming and simulation around 1970 is a largely forgotten chapter of history.

What does this have to do with photography? In the case of Baldessari, lots. He was interested in photography as a system, and he used games and randomization (e.g., throwing balls up in the air) to model it. In doing so, he was evidently taking on not only the everyday practice of photography but what we might call the Cold War “knowledge system.” The more time I spend with his work from that period, the more brilliant I think it is.

Nicholas Hughes, Untitled #16 (2012), from the series Aspects of Cosmological Indifferrence. Courtesy the Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York, and the Photographers’ Gallery, London

SE:What do you think are some of the contemporary meanings we ascribe to chance and photography?

RK: We are in a different era now. In some ways, the computational power of the digital age has fostered a return to determinism and a retreat of chance. Chaos theory, which is oddly named, posits that many things that seem random are actually determined by causal chains that are sensitive to initial conditions. In photography, we now have such a profusion of images that chance no longer seems to offer much of a pathway to the new. We have so many easy ways to digitally alter our images that chance seems to have given way almost wholly to the “chance effect.” But I wouldn’t dig the grave of chance and photography just yet. As I note in the conclusion, there are today still practitioners, such as Nicholas Hughes, doing interesting work that combines them.

The post On Chance and Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 13, 2015

Where in the World is Aperture?

Aperture exhibitions are currently on three continents, from Asia to Europe to the Americas. How does it come together? Aperture’s exhibitions manager Annette Booth takes us inside the many shows currently traveling the globe, from The Chinese Photobook presentations in both London and Beijing, to Martin Parr’s Life’s a Beach in Savannah, Georgia, to the exhibitions currently in the making at Aperture’s gallery space in New York City.

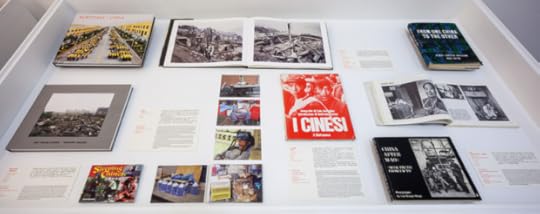

Installation view of The Chinese Photobook at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing

The Chinese Photobook, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, April 4–May 31, 2015

Installation view of The Chinese Photobook at The Photographers’ Gallery, London. Courtesy The Photographers’ Gallery. Photograph by Kate Elliott

The Chinese Photobook, The Photographers’ Gallery, London, April 17–July 5, 2015

The London and Beijing shows opened within two weeks of the exhibition closing at Aperture’s gallery. The books and framed portfolios in London are the same materials that were in New York, but the difference between the two shows is the size of the galleries and the layout of the walls. At Rencontres d’Arles, where the exhibition was first on view in 2014, each chapter of the exhibition was in a different room and viewed under flashlight, which definitely influenced your experience. At Aperture, we have an open space that can be partitioned with temporary internal walls, so each chapter had a space of its own but was in view of the next section.

Installation view of The Chinese Photobook at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing

Now in London, the show has been edited; the space is smaller and no internal walls are set up. The result is that books from the early 1900s are just across the wall from contemporary volumes. The work at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing is a different set of material, geared specifically for a Chinese audienceThis version doesn’t include the few books on Tiananmen Square, but it includes many more from the other historical chapters. Those books will now travel throughout China so more people will get the opportunity to see their history through the photobook. We were lucky that Martin Parr had a set of books in Bristol, England, and Ruben Lundgren another set in Beijing—it made the simultaneous exhibitions possible.

Martin Parr, Japan. Miyazaki. The Ocean Dome, 1996. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Martin Parr: Life’s a Beach, Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, May 15–July 30, 2015

Parr’s show started at Aperture’s gallery in New York in 2013, and is now in Savannah, Georgia, a small metropolitan city with a distinctly Southern vibe. The Telfair Museum will be the fourth venue in this exhibition tour, which began in 2013. The works are unframed and pinned to the wall, so the shipping is a breeze, which is one of the hardest parts about traveling exhibitions. And Martin Parr’s photographs are just a lot of fun: the last venue, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida, paired Life’s a Beach with Monet to Matisse: On the French Coast. You had the very traditional Matisse paintings alongside Parr’s witty, color-saturated photographs—the old and the new. Next year, the show will continue to the Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington.

Richard Renaldi, Vincent and Charles, 2012 © Richard Renaldi

Richard Renaldi: Touching Strangers, at Loyola Marymount University Museum of Art, May 23–August 2, 2015

I love what this show is about and the public really relates to it, that’s why it has done well as a touring exhibition. It’s about people letting go of preconceived stereotypes and relating to each other with an open spirit. I saw that as a kind of Jesuit ideal and so approached Loyola University Museum of Art, Chicago (LUMA), and Laband Art Gallery, Los Angeles, both associated with the Loyola Marymount Universities, which are Jesuit. LUMA Chicago is presenting the exhibition in connection with the one-hundredth anniversary of their School of Social Work. They’ve asked students and alumni from the school to pick a photograph in the exhibition and write up to fifty words in response. Their essays will be presented next to the piece in the gallery.

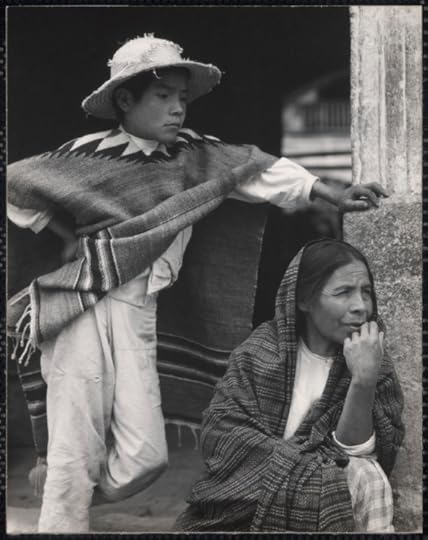

Paul Strand, Woman and Boy, Tenancingo, Mexico, 1933 © 2014 Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation, Inc

Aperture: Photographs, 1285 Avenue of the Americas Gallery, New York, June 29–September 18, 2015

Aperture: Photographs tells the history of Aperture Foundation through our limited-edition print and fundraising programs from over fifty years. The Founders and Friends portfolio, which includes work by Minor White, Edward Weston, and Dorothea Lange, is followed by Paul Strand’s Mexican Portfolio, the first portfolio that Aperture published in 1967. The viewer will stroll chronologically through a who’s-who list of photography greats: Lisette Model, William Christenberry, Bruce Davidson, and David Wojnarowicz, just to name a few. Then it goes to the present: there’s a commission by John Chiara, for which we asked him to respond to an assignment from The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014), and it ends with David Benjamin Sherry’s print from our newly launched, limited-edition subscription series for the magazine. It’s a really diverse display of photography from some of the best Aperture publications.

James, Mollison, Hull Trinity House School, Hull, UK © James Mollison

James Mollison: Playground, Aperture Gallery, New York, April 16–June 25, 2015

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Bottom (Talbot Towers, Allegheny County Housing Projects), 2009 © LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Selected Works, Aperture Gallery, New York City, May 14–July 9, 2015

What the Playground exhibition has that the book doesn’t is scale. Mollison’s work is detailed, and seeing his photographs large in the gallery encourages you to spend time with them. You can look at the same piece numerous times and then on the tenth time see something you didn’t see previously. There is also an immersive audio component of children playing in all these different languages. With schools from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East represented in the photographs, there’s an international perspective that makes it an ideal touring show. Also on view, starting on May 14, will be a selection of works by LaToya Ruby Frazier, in celebration of the Infinity Award for best publication awarded to The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2014).

The post Where in the World is Aperture? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

James Mollison and Jon Ronson on “Playground”

Photographer James Mollison and writer Jon Ronson recall their playground memories with Aperture Executive Director Chris Boot preceding the opening reception of the “Playground” exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York. Mollison photographs children at play in their school playgrounds, inspired by memories of his own childhood and how we all learn to negotiate relationships and our place in the world through play. Established writer and documentary filmmaker Jon Ronson wrote the foreword to “Playground”. With photographs from schools in countries including Argentina, Bhutan, Bolivia, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Nepal, Norway, Sierra Leone, the United Kingdom, and the U.S., Mollison also gives access for readers of all ages to issues of global diversity and inequality.

See the exhibition at Aperture Gallery through June 25th

The post James Mollison and Jon Ronson on “Playground” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 12, 2015

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Curriculum

Growing up in Braddock, Pennsylvania, photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier saw firsthand the economic and environmental decline and racism that affected her industrial hometown, subjects she explores through a personal documentary approach. For twelve years, she photographed her mother, grandmother, and herself in the series of deeply evocative images contained in her book The Notion of Family, published by Aperture in 2014. Also a lecturer and professor, Frazier is among the most compelling new voices working within and expanding the tradition of documentary photography today. For Aperture‘s Summer 2015 issue, the editors asked Frazier to contribute to the magazine’s regular Curriculum column, where photographers discuss readings and works of art that have informed their thinking. On May 14, Aperture’s gallery in New York City will open an exhibition of Frazier’s, culled from The Notion of Family, which just received an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography. This article also appears in Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

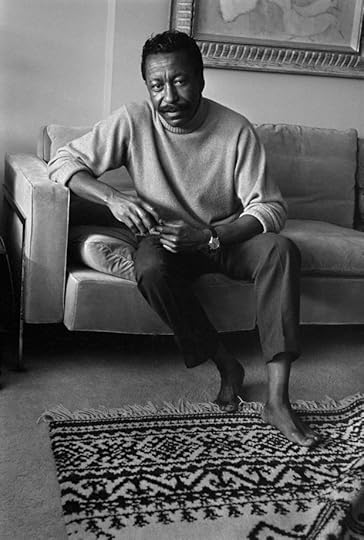

Eve Arnold, Gordon Parks, 1964 © Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos

Gordon Parks, A Choice of Weapons, 1966

Gordon Parks’s memoir taught me the best reason to pick up a camera: “My deepest instincts told me that I would not perish. Poverty and bigotry would still be around, but at last I could fight them on even terms.” It is a story of strength, courage, honor—a will to survive and make a mark on history. His ability to express his disdain for poverty, racism, and discrimination in America through eloquent, beautiful, and dignified photographs is timeless. Any student struggling to understand why some photographers document humanity will gain insight from this autobiography.

Fred W. McDarrah, Jamaica Kincaid, New York, 1974 © The Estate of Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place, 1988

I’ve been fascinated by literature’s freedom to render the complexities of dark childhood memories and abject realities. Kincaid’s fictions, semiautobiographies, and multiple points of view are intensely rich and unapologetically evocative. Her ability to take on themes of patriarchal oppression, colonialism, race, gender, loss, adolescence, and ambivalence between mothers and daughters inspires me. Any reader who wants descriptions of familial relationships or a sense of human relationships to homeland, economy, and education could certainly glean universal themes from Kincaid.

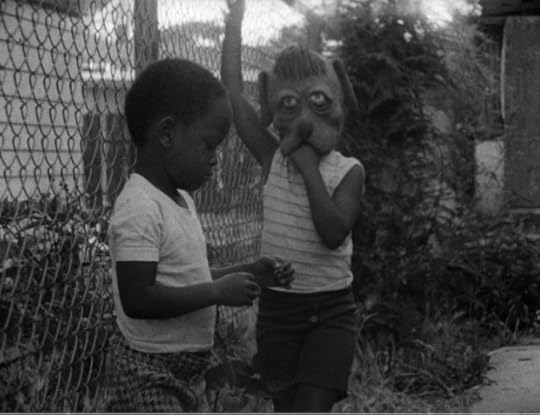

Charles Burnett, film still from Killer of Sheep, 1977 © Charles Burnett and courtesy Milestone Film & Video

Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep, 1977

My understanding of how to create atmosphere, mood, and narrative largely comes from my love of film and cinema—from Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, Alfred Hitchcock, and Charles Burnett to Wong Kar-wai. I love showing my students the relationship between these filmmakers’ visual language and that of classic photographers, like Eugène Atget, August Sander, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, and Parks. With its soundtrack and lyrical visual language, Killer of Sheep is the ultimate masterpiece. Set in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, a portrait of American life is rendered as the protagonist Stan struggles with social class and disillusionment while working long hours at a slaughterhouse; the stress to generate financial stability strains relationships with his wife and close friends. The film is an incredible depiction of how we negotiate intimacy and how we are restricted by landscapes and labor.

Jason Moran, “Artists Ought to Be Writing,” from the album Artist in Residence, 2006

Sometimes when I’m editing in the studio, I play music by jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran. I was brought deeper into his music when I heard artist Adrian Piper’s voice in his song “Artists Ought to Be Writing.” While writing the text to accompany my photographs in my first book, I followed Piper’s instructions: “Artists ought to be writing about what they do and what kinds of procedures they go through to realize a work. . . . If artists’ intentions and ideas were more accessible to the general public, I think it might break down some of the barriers of misunderstanding between the art world and artists and the general public.”

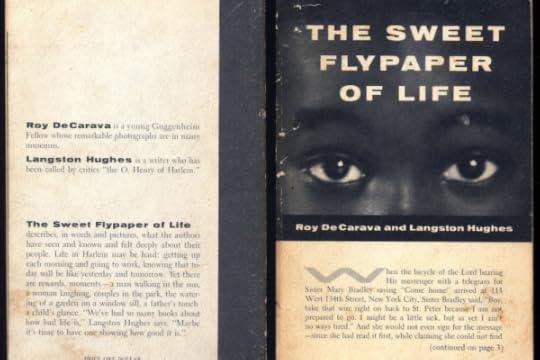

Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, 1955

DeCarava and Hughes’s collaboration is a perfect example of how history can be reclaimed and redirected through storytelling and imagination. Hughes’s words take us through the eyes of a fictitious grandmother to reveal a representation and memory of Harlem that is at odds with the unloved depictions reported by mainstream media in the 1950s. Hughes’s last book, Black Misery (1969), is seldom discussed or quoted, but this line resonates with my work: “Misery is when you heard on the radio that the neighborhood you live in is a slum but you always thought it was home.”

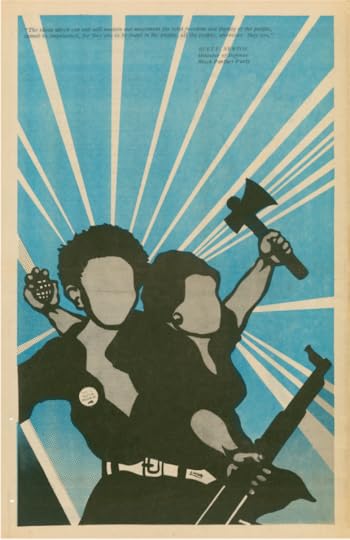

Emory Douglas, Untitled, from Black Panther, February 17, 1970 © Emory Douglas and Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

New Museum survey, Emory Douglas: Black Panther, 2009

Though I speak primarily through photography, I am not limited to it. Occasionally, I work in video and performance. When I look at the artwork, illustrations, prints, and roles of Emory Douglas as a revolutionary artist and minister of culture for his community, I am reminded of Bertolt Brecht’s The Popular and the Realistic (1938): “There is only one ally against growing barbarism—the people, who suffer so greatly from it. It is only from them that one can expect anything. . . . .Anyone who is not a victim of formalistic prejudices knows that the truth can be suppressed in many ways and must be expressed in many ways.”

August Wilson, The Piano Lesson, 1990

I watch this play to understand the great migration from the South, self-worth, and how to put my cultural legacy to use creatively.

Albert and David Maysles, film still from Grey Gardens, 1975 © Maysles Films Inc., via Portrait Releasing Inc.

Albert and David Maysles, Grey Gardens, 1975

This is the film that helped guide me into my collaborations with my mother. Full of compassion and without judgment, this brilliant documentary takes cinema verité and psychological space to another dimension. Shot over a six-week period of time, the Maysles brothers’ encounters with Edie and Edith Beale are not shown in chronological order. This destabilizes the viewer’s sense of time and heightens the complexity of the Beales’ relationship. The passage of time is indicated through a gradual collapse of a dilapidated wall; at the beginning it’s a hole in the plaster, toward the middle the hole expands, and by the end it falls completely as a raccoon crawls out. This is a great example of how time can be used as metaphor and to build tension in a set of relationships.

Aperture magazine #219, “Tokyo,” Summer 2015, is coming soon. Tap here to subscribe.

The post LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Curriculum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers