Aperture's Blog, page 156

July 23, 2015

William J. Simmons on Josef Astor at Participant Inc.

Writer William J. Simmons reviews Josef Astor’s recent exhibition at Participant Inc., New York, which connects photography, installation, and dance. The show was curated by Astor’s frequent collaborator and subject, the cult musician Antony.

This article originally appeared in Issue 12 of the Aperture Photography App.

Joe-Ho, 1996. All photographs by Josef Astor, courtesy Participant Inc.

By William J. Simmons

Josef Astor’s résumé runs the gamut of the art world—an instructor at the School of Visual Arts, an acclaimed director, and a commercial as well as fine art photographer, he has had a varied, decades-long career. Astor received an equally complex treatment in his recent exhibition at Participant Inc., an incisive and long-overdue survey of his work from the 1980s through the 2000s. Lovingly curated by Antony—one of Astor’s longtime models—Displaced Persons exists at the intersection of dance, photography, and documentary, and took a humorously critical eye toward art-historical conventions. Astor’s project is an archive of an era, full of cross-disciplinary communities and collaborations, which no longer exists. Displaced Persons illustrated this unsure mixture of bodies and histories while never coalescing into a flattened narrative. A simultaneously celebratory and sorrowful air filled the space as Astor invited us to a lyrical examination of the unforeseen and, at times, paradoxical possibilities of a photograph.

Peeesseye, 2005

Page + Wid, 1999

Using rear-screen projections (as in the oft-overlooked series in the same vein by Laurie Simmons and Cindy Sherman) as well as inventive costuming, Astor created an environment rather than purely a show. As a result of his mastery of color manipulation on these archival prints, a sickly pallor was cast over the gallery, broken from time to time by bursts of glamorous purples and reds. In Peeesseye (2005), a figure that appears to don a bondage mask presides over what could be either a fight or an avant-garde performance; the room’s gaudy fluorescence suggests an even stranger version of Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s hustler images. Light cast from a Del Taco sign in Astor’s Ralph Smith, 21 years old, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, $25 (1990–92) results in a stunningly artificial, yet uncannily real dreamscape. For Astor, the body is always fighting for movement in the fixed field of the photograph. The dancers from Astor’s collaborations with Charles Atlas, such as the combatants in Peeesseye, seem to perpetually struggle against various forms of bondage: a shackled Leigh Bowery is grounded but no less fabulous.

Annie + Puppet, 1994.

These issues—history, embodiment, and performance—reach an apex in Skewed Halo (1999), a portrait of Antony himself. The makeshift studio walls and single pale disc on the floor, reminiscent of an ersatz minimalist sculpture, provide a hiding place for a crouching figure clad entirely in white save for his blood-red lips. However, the most interesting detail is the most obvious: Astor has dressed his model in an enormous condom, separating Antony’s body from the surroundings with a tenuously protective layer. In Astor’s elegant combination of photography and performance, we are presented with the specter of the AIDS crisis—at once a tribute and an opportunity for a cross-generational reckoning with this tragedy. Astor confronts us with our own permeability, and the possibility of the body’s decay, just as various artistic disciplines become permeable in his hands.

Skewed Halo, 1999.

Displaced Persons was equal parts memorial and art exhibition—Leigh Bowery, a muse for many, lost his life to AIDS-related illness—and, as a result, Astor produced a space for reflection on a bygone New York City, even as he posed crucial aesthetic questions running the gamut of normative and non-normative art histories.

Displaced Persons was on view at Participant Inc., New York, from May 31 to July 12.

The post William J. Simmons on Josef Astor at Participant Inc. appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 22, 2015

Recap: 2015 Aperture Summer Open Opening Reception

On Thursday, July 16, Aperture held the opening reception of the 2015 Aperture Summer Open exhibition, an annual open-submission exhibition about the character of photography now, to which all photographers are invited to submit work. The exhibition will be on view at Aperture Gallery through August 13.

The theme of this year’s Summer Open is “Black Mirror.” The title Black Mirror is borrowed from the 2011 British television series of the same name, which imagines a dystopian near future—a Twilight Zone for the age of the smartphone. More than 500 photographers applied to this year’s call for entries, and 24 were selected by Aperture magazine editor Michael Famighetti. Before the opening, Michael Famighetti invited the participating photographers to talk about their work in the Aperture gallery.

See the full list of photographers included in the exhibition here.

Aperture deputy director Sarah McNear welcomes Aperture members to the Summer Open walkthrough before the opening

Artist Felix R. Cid talks about his piece Untitled (Detroit),2014

Artist Sarah Meyohas talks about the process behind her work from the series BitchCoin, 2014

Artist Balarama Heller explains the work from his series, Sparrow Mountain, 2010–14

Artist Farah Al Qasim talks about her Dubai-based series, The World is Sinking, 2013–14

Artist Ben Freedman talks about his work from the series Dark Matter, 2014

Artist Emmanuelle Andrianjafy stands by her work from the series We’re Moving to Kounoune, 2015

Artist Emmanuelle Andrianjafy talks with a guest at the reception for the Summer Open

Artists Emmanuelle Andrianjafy, Philippe Branquenier, Ben Freedman, and Brandon Nichols

Artist Balarama Heller with guests

More than 300 guests attended the opening reception Thursday night at Aperture Gallery in New York

All images © Max Mikulecky and Nahshon Outten

The post Recap: 2015 Aperture Summer Open Opening Reception appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 17, 2015

Issue 12 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 12:

● An excerpt from one of Mary Ellen Mark’s last projects Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment

● Letters from Sally Mann on process that originally appeared in Aperture magazine #138, from 1995.

● A portfolio of Polaroids by Nobuyoshi Araki that appeared in Aperture #219, Summer 2015, “Tokyo.”

● An inside look at the printing of Jimmy DeSana’s Suburban, out this fall from Aperture

● A review of Josef Astor at Participant Inc. by William J. Simmons

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 12 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 14, 2015

The PhotoBook Review: Photobooks After 3/11

By Marc Feustel

Marc Feustel, an independent curator, writer, and editor based in Paris, examines the photobook in the wake of the earthquake and resulting tsunamis that devastated northeast Japan on March 11, 2011. This article appeared in The PhotoBook Review 008, guest edited by Ivan Vartanian and focused on photobooks from Japan.

This article originally appeared in Issue 11 of the Aperture Photography App.

Rinko Kawauchi, Light and Shadow (Tokyo: Rinko Kawauchi Office Co., Ltd., 2012)

It has been four years since the Great Tohoku Earthquake unleashed a series of tsunami waves which struck a vast area of Japan’s northeastern coastline, and caused a severe nuclear incident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Japan is no stranger to natural and man-made disasters. However, since the 1960s the nation has, by and large, experienced peace and prosperity. Since the post-bubble years of the 1990s, much of Japanese contemporary art has been driven by self-representation and aesthetics. But the events of March 11, 2011 (referred to in Japan as 3/11), have profoundly impacted the way art is both made and received in Japan, and today the social and documentary concerns that characterized the postwar years have risen back to the surface.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, photographers from around the country—and indeed the world—flocked to the devastated area. In the following months, book after book was published, seemingly documenting every inch of the devastated coastline. This photographic reaction is both natural and necessary, as if events of this magnitude require images to make it possible for us to begin to comprehend them. However, the sheer volume of these book projects quickly became overwhelming. It was difficult to feel anything but numb when faced with these endless images of devastated landscapes.

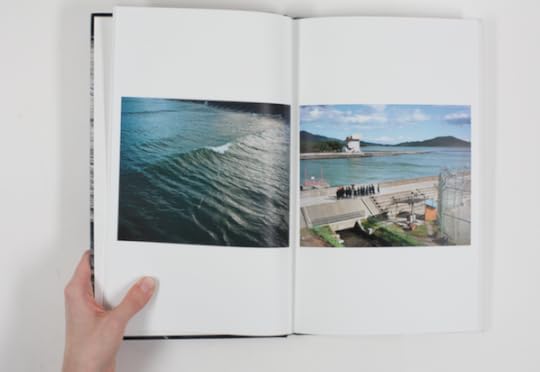

It was in this context that projects began to emerge with new approaches to this difficult subject. As early as April 2011, Rinko Kawauchi traveled to the earthquake-devastated towns of Ishinomaki, Onagawa, Kesennuma, and Rikuzentakata. From this journey she created the series Light and Shadow, based on her encounter with a pair of pigeons, one black, one white. This became the project’s theme: the dualism of light and shadow, good and evil. While the photographs depict destruction, Kawauchi’s work does not feel like a document, but rather a transcendence of the disaster, where despair already contains the seeds of hope. Two publications have emerged from the series, both titled Light and Shadow: a short, self-published book in 2012, and an expanded edit of the series published by SUPER LABO in 2014.

Rinko Kawauchi, Light and Shadow (Tokyo: Rinko Kawauchi Office Co., Ltd., 2012)

New approaches were also at work in two projects dealing with the Fukushima nuclear incident that resulted from the earthquake: Katsumi Omori’s Subete wa hajimete okoru (Everything happens for the first time, Match and Company, 2011) and Takashi Homma’s Sono mori no kodomo (Mushrooms from the forest, Blind Gallery, 2011—both of which were reviewed by Ivan Vartanian in The PhotoBook Review 002.) Fukushima is the least likely of photographic subjects as it demands the impossible: to photograph radiation—the invisible. Omori described the compulsion that drove him to Fukushima: “I must go to Fukushima. I must shoot the radiation (though it cannot be shot).” By employing a halation effect throughout his series, he lays bare the limitations of photography in the face of this invisible threat, while also giving that threat a form.

Tomoki Imai, Semicircle Law (Match and Company, Tokyo, 2013)

At first glance, Homma’s images of forests and wild mushrooms seem to bear no relation to the nuclear power plant, but their meaning is transformed by a brief text buried at the end of the book. In it, Homma explains that mushrooms absorb radiation faster than other living organisms; those he collected in the forests of Fukushima Prefecture contain much higher

levels of radiation than elsewhere in Japan. The experience is unsettling, forcing the viewer back through the images with a very different eye. Tomoki Imai’s Semicircle Law (Match and Company, 2013) uses a similar device. His seemingly anodyne forest landscapes are transformed by a diagram at the end of the book revealing that his photographs were taken on either side of the twenty-kilometer security radius established by the Japanese government around the stricken nuclear plant. Imai himself has said that he thinks these images’ significance will depend on which vantage point the future will bring.

Non-Japanese artists have also been drawn to the affected region. The German photographer Hans-Christian Schink traveled to Japan one year after the quake to photograph the coastline. Tohoku (Hatje Cantz, 2013) provides a complex view of the aftermath of 3/11, in which the tsunami’s impact ranges from the imperceptible to the brutal—a landscape still caught in the midst of a long healing process. More recently, Antoine D’Agata produced a surprising new book on Fukushima. Over the course of six hundred black-and-white plates, Fukushima (SUPER LABO, 2014) presents a typology of those houses abandoned due to their proximity to the stricken nuclear plant. A far cry from D’Agata’s signature work, the uncharacteristic coolness of these images builds to a foreboding emptiness.

Tomoki Imai, Semicircle Law (Match and Company, Tokyo, 2013)

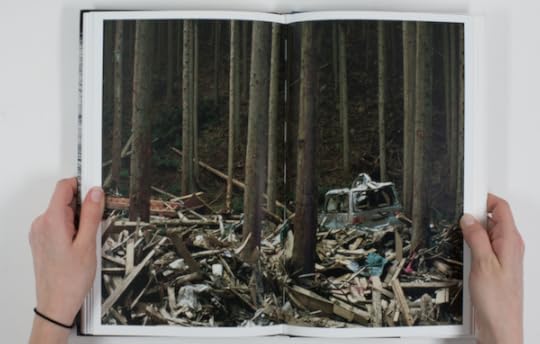

While all the projects mentioned above were created by photographers from outside the Tohoku region, for some the events of 3/11 were of a more personal nature. Iwate-born Kazuma Obara’s Reset Beyond Fukushima (Lars Müller, 2012) goes beyond a documentation of the catastrophe to become a call to action—the book’s subtitle is Will the Nuclear Catastrophe Bring Humanity to Its Senses?—in the grand tradition of the Japanese protest book. Naoya Hatakeyama is also from Iwate, and his book Kesengawa (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2012; Editions Light Motiv, 2013) is concerned with the destruction of his hometown of Rikuzentakata. Kesengawa has two distinct halves. The first contains photographs that Hatakeyama had been casually producing over the years along the Kesen River, which runs through Rikuzentakata. The book then shifts into the photographs taken in his hometown in the aftermath of the wave. In the book’s afterword he describes his aim to “bring the event closer to people, to compress the physical distance.” Whereas Homma and Imai’s images are altered by the text that follows them, in the case of Kesengawa, the photographs are transformed by the events themselves. Snapshots made only to be tucked away in a small box in Hatakeyama’s studio suddenly gained great significance—a profound illustration of the ever-shifting relationship between photography and the world.

Spreads from Naoya Hatakeyama, Kesengawa (France: Editions Light Motiv La Madeleine, 2013)

Lieko Shiga was directly affected by the tsunami. In 2008 the young artist relocated to the small coastal village of Kitakama in Miyagi Prefecture, where she had been given a home and a studio in exchange for taking on the role of official photographer for this small community. Shiga had been working on an ambitious project about her adoptive home when the tsunami struck, destroying much of the community and her studio with it. She went on to finish the project, which became a book and an exhibition. Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Beach, AKAAKA, 2013—short-listed as PhotoBook of the Year in the 2013 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards) is not a book about the tsunami, but one whose course was profoundly affected by it. Like many of the projects referred to here, Rasen Kaigan is also concerned with bringing the invisible to light: rather than documenting the surface of her adoptive community, Shiga chose to focus on its fantasies, dreams, and memories—its “essence.”

Of all the books that deal with the 3/11 tsunami, Tsunami, Photographs, and Then: Lost and Found Project (AKAAKA, 2014—short-listed as Photography Catalogue of the Year in the 2014 PhotoBook Awards) is perhaps that which says the most about photography’s importance at times like these. The book provides an overview of the work of the Lost and Found Project, a group that was formed to attempt to retrieve photographs that had been scattered by the wave, preserve them, and return them to their owners. Initiatives like this one sprung up all along the Tohoku coast, and are a testament to the vital importance accorded to photographs when all has been lost.

An extraordinary breadth of projects and approaches have emerged around 3/11 in the past four years. The books mentioned here all deal with the subject directly, but there are countless others in which these disasters are a powerful, if indirect, undercurrent; the many projects referred to in this piece only represent a beginning. Looking to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, these events remained key themes for decades after the events. Arguably the two most powerful bodies of work on the atomic bombings, Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu (The Map, 1965) and Shomei Tomatsu’s 11:02 Nagasaki (1966), were not published until twenty years after the fact. Today, the resurgence of social concerns echoes the artistic engagement of those postwar years. Perhaps the greatest photobooks to deal with 3/11 are still to come.

The post The PhotoBook Review: Photobooks After 3/11 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 13, 2015

Tokyo’s Spaces

By Kenji Takazawa

Tokyo is teeming with independent art spaces that present exhibitions, sell photobooks, and provide platforms for discussing photography. Journalist Kenji Takazawa provides an essential guide for your next photographic tour of Japan’s capital. This online-only piece is published in conjunction with the “Tokyo” issue of Aperture magazine.

This article originally appeared in Issue 11 of the Aperture Photography App.

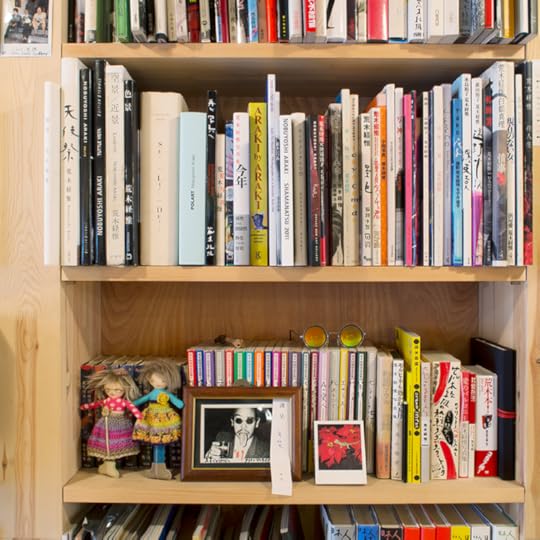

Shelves at the Photobook Diner Megutama

The most experimental photography in Japan has more often than not been produced by photographers operating outside the mainstream. Before the Second World War, the scene was found in amateur photographer clubs; after the war, independent galleries provided spaces for reflection. Many of these independent galleries were set up in the 1970s by photographers who had studied at the Workshop School run by Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama, in a bid to overcome the otherwise limited options for presenting their work to the public. At this time, mainstream photography was dominated by galleries that belonged to camera manufacturers. It didn’t help that photography tended to be held in low esteem by the art world. For young photographers bent on innovative photographic expression, they really had no other option but to set up and run their own places. These independent galleries, and the amazingly original work they produced, are important to understanding photography from Japan.

This tradition is still alive in Tokyo today. As someone who makes a living interviewing the main players in Japanese photography, I spend quite a bit of time just walking the streets of the city and checking out the scene. Let me take you on a little photography-themed tour.

The Photobook Diner Megutama

This café and restaurant serves delicious Japanese home cooking and is located near Ebisu Station. The wooden shelves that run along most of its walls are filled with photography books. The place is run by a trio of people—the photographer Kotaro Iizawa, the artist Tokitama, and Megumiko Okada, who is in charge of the food. What explains such an amazing collection of books? And why have them in a restaurant? “These are all photographic books that Iizawa has been amassing for over thirty years,” Tokitama explained. “We had more books than we could handle at home, so we thought we’d make them available in a collection here.” Iizawa is one of Japan’s most prolific photography critics, author of more than fifty books on photography. In the 1990s he worked as an editor for the photography magazine déjà-vu. “I’ve organized so many events that involved food in one way or another,” Megumiko added. “Food is just such a great way of putting participants at ease and helping things go smoothly—and visitors like it as well. But probably the main reason for this photobook restaurant is that the three of us just love to eat!”

Altogether the collection amounts to some five thousand volumes, including rare photobooks and collections by photographers Daido Moriyama, Nobuyoshi Araki, and Kiyoshi Suzuki. Amazingly, anyone can just take the books off the shelves and start reading—none of the stiff rules of public libraries apply. The idea is for visitors to look at the books, enjoy the photographs, and chat to each other about them. It’s a pretty laid-back place, and probably one of a kind.

POST

Keisuke Nakajima set up this independent bookstore, also located in Ebisu, in 2005. POST sells photography and art books, and most uniquely, features art books from only one or two publishers at time, with the idea of highlighting their particular character and vision. POST’s gallery space shows work by contemporary Japanese and non-Japanese photographers. The Tokyo-based photo-duo Nerhol and the American photographer Todd Hido have both exhibited here. POST has also begun publishing printed editions, for example, by Takashi Homma and Nao Tsuda.

Photographers’ Gallery

Shinjuku is probably what comes to mind when anyone mentions Tokyo street photography, since the area has long featured in the work of Moriyama and Araki. In this area many small independent photography galleries can be found. The Photographers’ Gallery, located in the heart of Shinjuku Nichome, the gay center of Tokyo, is well-known throughout Japan. Photographer Keizo Kitajima has been the driving force behind this gallery since its establishment in 2001. Famous for photobooks such as Photo Express: Tokyo and USSR 1991, Kitajima was also a founding member of CAMP, the legendary independent photographic gallery and magazine publisher. “We photographers have always liked to run our own show. We value our independence, and we like to be in charge of everything we do,” Kitajima said. “CAMP was one expression of this. Being involved in photography means not only creating and showing your own work, and running your own gallery, but holding talks, putting out publications, the whole thing. It means doing it all.”

Photographers’ Gallery publishes its own magazine under the title of Photographers’ Gallery Press. Recent issues have featured little-known areas in the history of photography in Japan; Kenzo Tamoto’s photographs of the reclamation projects of Hokkaido, for example, and reappraisals of photographs of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This independent bookstore and gallery is located in Shinjuku Gyoen. Sokyusha published Masahisa Fukase’s 1986 Karasu (Ravens), as well as many other photobooks by figures like Moriyama and Miyako Ishiuchi. In much the same way as POST, Sokyusha stocks new publications as well as old ones, and it also releases privately published limited editions. The shelves of this bookstore, carefully curated by the owner and photobook editor Michitaka Ota, speak volumes about the fiercely independent spirit of Japanese photography.

A gathering at Place M

Not far away from Sokyusha Photobook Store is Place M. Established in 1987 by the photographer Masato Seto, known for his photobook Heya/Living Room, Tokyo (1996), as well as the photobook Binran (2008), this must be one of the longest-running galleries in Tokyo. The place is now run by a team of four photographers, including Moriyama. “I was one of the first students to study under Moriyama,” says Masato. “But I wasn’t a member of CAMP. I went to view their exhibitions, but at that time I wasn’t independent. Once I became independent I wanted a place to show my own work, and that’s when Michio Yamauchi and I set up Place M.” Place M is a multifunctional space that combines galleries, darkrooms, a bookstore, and workshops. And of course, it’s also a publisher. Quite often lectures are held here.

Inside Bar Kodoji

Bar Kodoji

A short walk from Place M will bring you to Golden Gai (“Golden Town”). A maze of six or so streets crammed with shanty-style bars and frequented by any number of players involved in theater, film, and photography, in the 1960s and ’70s this was one of the hippest neighborhoods in Tokyo, functioning as a kind of cultural salon. Artists have never been able to count on support from the government here in Japan, so aspiring artists have always had to find their own makeshift meeting places, and here in Golden Gai you could get a cheap drink and a bite to eat. Photographers such as Moriyama and Araki frequented the dives and hangouts of this part of town, so it’s hardly surprising that the streets of Shinjuku feature prominently in their work.

One of the oldest and most famous of Golden Gai bars is Bar Kodoji, established in 1974. As its proprietress Shigeko Ono explained, “I opened this bar at roughly the same period as CAMP was begun. Lots of CAMP members used to come here to drink, and that was the start of the association with photographers.” In 2002 she began using the walls of the bar as a place to display photos, and at one time Moriyama had an annual exhibition here. Last year there were exhibits of work by Koji Onaka and the French photographer Antoine D’Agata. “At first I told him no, but Antoine kept begging and begging till finally I said yes. I’ve known him for close to ten years. I’m kind of nervous about what kind of photos he’ll want to show!” she joked to me last winter.

The shelves here are packed with photobooks that have been given to the bar by various photographers and editors. Among them are some very rare books–the photo-album Kazoku (Family, 1991), for example, by Masahisa Fukase. In fact, Golden Gai was one of Fukase’s favorite neighborhoods, and he used to come here to drink pretty much every night. (He died in 2000.)

That’s just a quick tour of some of the spaces in Tokyo frequented by lovers of photography. Needless to say, countless other places exist, even in Shinjuku alone. Over in Jimbocho, the booklovers’ paradise of a neighborhood, is The White gallery. On the east side of the city, near the Museum of Contemporary Art, is TAP Gallery, which combines a gallery and a bookshop. Even further east, in Higashi Mukojima, is Reminders Photography Stronghold. All of these places combine remarkable book collections, gallery space, and public programming-and they all share an intimate atmosphere, even if the spaces are sometimes cramped and the furnishings less than luxurious. The people who run them live, breathe, eat, and talk photography–it’s the most important thing in their lives.

Translated from Japanese by Lucy North. All photographs by Mie Morimoto.

Tap here to find Aperture magazine on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Tokyo’s Spaces appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 9, 2015

Genevieve Allison on Gillian Laub at Benrubi Gallery

By Genevieve Allison

This article originally appeared in Issue 11 of the Aperture Photography App.

Julie and Bubba, 2002. All photographs Courtesy Gillian Laub/Courtesy Benrubi Gallery, NYC

The American South has been a fertile subject for photographers throughout the history of the medium. From the Depression-era urtext of FSA documentary photographers like Walker Evans to Eggleston’s in-color mapping of the suburban South’s desuetude-picturesque, as well as Martin Parr’s outsider representation of its contemporary character, our collective imagination is built around representations of a historical charm—and its difficult legacy. One finds a distinctly Southern vernacular in the horizontal milieu of backyards, languid architecture, and low, vacant landscapes. But most of all, photographers and documentarians have gravitated toward an expression of Southern culture through the human face, often with an emphasis on the familial and an eye toward the impecunious and the disenfranchised.

The Prom Prince and Princess dancing at the integrated prom, 2011

Mount Vernon, a small town in rural Georgia just inland from the coastal plains, is by most measures unremarkable save for one extraordinary anachronism that has persisted there well into the twenty-first century. Although Montgomery County High School was integrated in the early 1970s, for the last four decades it has held racially segregated proms, throwing two separate proms on separate nights and crowning two sets of prom kings and queens: one white, one black. Gillian Laub, perhaps better known for her work on the Middle East, began photographing the community in 2001 and, compelled by the complicated cultural landscape she encountered, kept returning for more than a decade to document the annual event and its matriculating teenagers. Her twelve-year visual study offers striking portraits of the student-subjects and glimpses of a society deeply inflected by religion and tradition. It serves as document of the prevailing issues of race and inequality still affecting the social and material conditions of education in the United States sixty-one years after Brown v. Board of Education.

Amber and Reggie, 2011

The selection in this exhibition mainly looked at the years that directly precede and follow 2010, the year the first integrated prom was held (a change that was finally effected after the national outcry following the New York Times Magazine’s publication of Laub’s work and the production of an HBO documentary). Following a “prom photo” convention of sorts, the images capture a prescriptive sequence of events: the congregation beforehand on back lawns, porches, and driveways; the slow dance; the seat in an empty hall at the end of a long night. The pictorial language is straightforward documentary portraiture. The accompanying wall texts, which offer quotes and context, lend the presentation a sense of journalistic intent. Individually and collectively, these accounts provide an unmediated entrée into the personal circumstances informing each experience. By virtue of this device, each photograph operates in specific and concrete reference to the underlying social context and unequivocally underlines the moral and political purpose of the work.

Angel outside the black prom, 2009

Collectively, the images are a facet of a greater narrative: of young, formative identities brushing up against cultural and ideological obstacles. A mixed-race couple (Qu’an and Brooke) poses together outdoors in the late sunlight in a stiff but intimate clasp; two years back, Qu’an points out, he and Brooke would never have been able to go to the prom together. Included in the archival material and documentary ephemera also presented with the work is a handwritten letter from a student to a teacher. It was submitted in lieu of an assignment and plaintively addresses the iniquity of segregation at the school prom: it received a grade of 76 percent.

Qu’an and Brooke, 2012

Southern Rites was on view at Benrubi Gallery from May 14 to July 2.

The post Genevieve Allison on Gillian Laub at Benrubi Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 8, 2015

Kathrin Sonntag On Her Installation, This Was Tomorrow Once

Portrait Kathrin Sonntag at Fotografie Forum Frankfurt, June 2015 © RAY 2015 Fotografieprojekte Frankfurt/RheinMain

This summer RAY 2015 Fotografieprojekte Frankfurt/RheinMain presents examples of contemporary photography and related media at twelve venues in Frankfurt am Main and the surrounding region. The Berlin-based artist Kathrin Sonntag (b. 1981) was commissioned to create one of twelve new productions for RAY 2015. Her site-specific installation “This Was Tomorrow Once” is one of the spaces of the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt, one of the three venues currently presenting the photography triennial’s central exhibition, titled IMAGINE REALITY (June 20– September 20 at Fotografie Forum Frankfurt, Museum Angewandte Kunst and MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main). For IMAGINE REALITY, twenty-eight artists use fragments of reality to create imaginary and visionary worlds. Their images lead into a world in which reality and fiction, facts and illusions are inseparably woven together. The following interview was conducted by RAY 2015 organizers and is presented by MMK Notes (the MMK Museum blog) and RAY 2015.

RAY: What is the origin of the title This Was Tomorrow Once?

Kathrin Sonntag: During my research on the topic of time travel, I discovered the quote in the film Portrait of Jennie (1948) and thought it fit well with the topic of my new project. When one thinks of a future moment from the present, and this very moment is temporally exceeded, the thought “this was tomorrow once” comes to mind. With its confusing effect, the quote describes what I wanted to deal with in my installation at the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt.

Kathrin Sonntag, This Was Tomorrow Once, 2015. Exhibition View from IMAGINE REALITY at Fotografie Forum Frankfurt. Photograph: Albrecht Haag © Kathrin Sonntag, RAY 2015 Fotografieprojekte Frankfurt/RheinMain

RAY: Can you say something about the beginnings of this project?

KS: The basic idea was to make the room in which the piece is shown the main motif of the installation—to photograph the exhibition space and insert these photos in the space as 1:1 photo wallpaper. Beyond that, I wanted to add an aspect of temporality. Photographs always capture a past moment. While developing the installation I asked myself: is it possible to create images that look as if they come from the future?

I developed situations for the space that capture temporality. The idea of my new production for RAY 2015 is based on the question of whether photography can serve as a time machine.

RAY: With the question of ephemerality, you refer to a very characteristic theme of the medium of photography. Through capturing moments of action, such as photographing a fresh-picked bouquet of flowers to stand in contrast with a wilting bouquet in the room, you bring different layers of time to the piece. Can you explain these layers of time more?

KS: The passing of time becomes clear through the altering or shifting of individual objects within my installation. Differences between the objects depicted on the wallpaper and those in the actual space create confusion about the time sequence. For example, there is a broom in the space that appears broken on the wallpaper. There are marks on the broom that lead [one] to the conclusion that it must be the same broom. If the broom in the space is intact, how can the broom on the wallpaper be broken, unless one assumes that it depicts the future? All objects that are represented in this installation refer to the beginning or the end, the set-up or deconstruction of an exhibition. Meanwhile, the viewer will always perceive the moment in-between, the presence of the exhibition.

RAY: What about the other clocks in the image?

KS: How it is possible to photographically illustrate a time sequence? I play with objects in the installation, through whose change the passing of time can be grasped. The before-mentioned wilting flowers represent a classic motif, through which the the passing of time is illustrated. The mirror, on the other hand, is an object that reflects the present. In the installation it appears in printed form on the wallpaper and so creates the illusion that the current state of the room is displayed. Next to these objects, the clock is probably the most obvious symbol of time passing.

RAY: Can one say that a temporal state is created in your work that doesn’t exist for the viewer?

KS: On the wallpaper I myself am depicted, and on my wrist is a watch that also shows the date next to the time. The date is set to exactly half of the duration of the exhibition. So, for a while, this photograph displays the future, for a fleeting moment the present, and then the past. It is dependent on the time that the viewer visits the installation.

RAY: In some ways it seems as though you intend to create a confusion about the different temporal layers. Could there lie the possibility in this to see more than there is to see de facto?

KS: In my work I play with everyday scenarios, in which subtle shifts cause confusion. For me, it makes sense to start at the familiar. It is moments like these that interest me, in which one starts to stumble visually and starts questioning our habits of perception. In this moment of delay lies the potential to view something that one has seen a thousand times from a new perspective. The medium of photography—which we trust to reflect an objective representation of reality and that we distrust at the same time, because we are aware of the corruptibility of photographs—offers an interesting starting point in this context.

Kathrin Sonntag, This Was Tomorrow Once, 2015. Exhibition View from IMAGINE REALITY at Fotografie Forum Frankfurt. Photograph: Albrecht Haag © Kathrin Sonntag, RAY 2015 Fotografieprojekte Frankfurt/RheinMain

RAY: In your work you play with relationships of proximity and distance. From your viewpoint, can a sentitive glance at photography be created, that can be upheld beyond the visit to the exhibition?

KS: Perception is always selective. However, through the great mass of images that we encounter every day, one could speak of a conditioning of the view that engraves the ever-same interpretation or reading. I like playing with conventions of seeing, and to momentarily create a change of perception mode through visual stumbling blocks.

Of course, it would make me happy if this shifted view would be upheld beyond the visit to the exhibition, if the visitor to the FFF came home and suddenly think that even the water bottle on [her] kitchen table somehow looked odd.

This interview was conducted by MMK Notes and RAY 2015 © RAY 2015 Fotografieprojekte Frankfurt/RheinMain, www.ray2015.de/ MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. The interview on the websites for MMK Notes and RAY 2015.

The post Kathrin Sonntag On Her Installation, This Was Tomorrow Once appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 7, 2015

Staff Picks: 7 Instagram Accounts We’re Following

Members of the Aperture Foundation staff selected our favorite photography-related Instagram accounts of the moment, ranging from photographers to editors to public collections. Follow the Aperture Beat column on the app and online for regular staff picks about favorite readings, social media, and exhibitions.

This article originally appeared on the Aperture Photography App.

Thomas Prior, a New York–based photographer whose work appears in Outside, Bloomberg Businessweek, and the California Sunday Magazine, uses Instagram to capture moments from his travels and projects. I’ve been an avid fan-follower of his account since last summer, when he was shooting a series on handball courts in New York City. In Handball (2014), sculpted bodies play against white concrete, the shadows poetically quiet but full of tension; these naturally lit, uncanny images captured with a sharp eye quickly made this account unforgettable and one of my favorites. —Mariah Tyler, Editorial Work Scholar

The Instagram for the New York Public Library is widely followed, but perhaps lesser known, and far more idiosyncratic and irreverent, is the account for the NYPL Picture Collection. The trove contains more than one million images from mostly pre-1923 periodicals, as well as original photographs, prints, and postcards. More than thirty thousand of these have been digitized and are available through the library’s website, and the accompanying Instagram features oddities such as vintage fabric samples, baseball cards from 1889, and FSA photographs by Dorothea Lange. Also notable is that the library currently has a major photography exhibition on view through September, of selections from its vast collection of 175 years worth of photography. —Alexandra Pechman, Online Editor

The booksellers of Dover Street Market have an excellently curated selection of fashion books, kitschy architecture books, photography books, and design titles. Sometimes, rare Aperture titles will pop up! A must-follow for collectors. —Elena Tarchi, publicity and events associate

Sam Morrison’s feed invites followers to travel the world alongside him. A photographer and social media enthusiast who works at Kaltura, an online video TK, we originally studied photography together at the iSchool at Syracuse University. In 2011, his father challenged him 100 dollars to do a back flip every day of the year, so Sam posted his flip pictures online daily; after he won the bet, Sam made a life goal to do a back flip on each continent. Sam’s style has evolved since we were students photographing each other in banal settings while dreaming of travel. His passion for social media is inspiring to me; it’s no wonder that he found his job with Kaltura through Instagram. –Beatrice Schachenmayr, Development Work Scholar

It’s rare to find a photographer whose work I like to have an Instagram that’s equally interesting. Noah Kalina’s feed is a mix of repeating landscapes and photos from behind the scenes of a traveling editorial photographer, all while not taking himself too seriously (it is Instagram, after all).—Max Mikulecky, Digital Marketing Assistant

Although I’ve seen people utilize “the grid” on Instagram, Melissa Spitz takes this to another level. Spitz almost always posts three or more photos at a time to achieve a grid of perfect larger photos. Sometimes the bigger picture is made up of twelve or more Instagrams: it’s well worth it in the gallery view. Her entire Instagram account is devoted to a single body of work documenting her mentally ill mother. —M.M.

When someone complains to me that Instagram is nothing more than a platform for narcissistic rituals or a frivolous trade in pictures of about-to-be-consumed meals and insipid feline adventures, I’ll point them to Jennifer Higgie’s feed. Higgie, a coeditor of Frieze, posts portraits of artists (all are women) on the day of their birth. Each is accompanied by a deep caption, rich in biographical detail, which includes a captivatingly compressed narrative of a fascinating life. Higgie’s posts on figures ranging from writer Flannery O’Connor, photojournalist Hansel Mieth, or the electronic music composer Delia Derbyshire—to name just three of her more than one thousand posts—often end with the command “Bow Down.” Instagrammers should be directed to do the same before Higgie, whose feed proves that this platform can be as rich as you want it to be. —Michael Famighetti, editor of Aperture magazine

Click here to follow Aperture Foundation on Instagram.

The post Staff Picks: 7 Instagram Accounts We’re Following appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 1, 2015

At the Opening of Aperture: Photographs

Installation view of Aperture: Photographs. All photographs by Max Mikulecky.

This past Monday photographers and friends of Aperture gathered at the 1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery for the opening of Aperture: Photographs, a unique exhibition gathering decades of Aperture’s history into one space. The photographs draw from Aperture’s print and fundraising programs from more than fifty years by more than forty photographers. The exhibition spans from classic works by the likes of Robert Capa, Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, Edward Steichen, and Paul Strand to contemporary photographers who work with Aperture today including LaToya Ruby Frazier, Richard Misrach, James Mollison, David Benjamin Sherry, and Penelope Umbrico, along with many more.

The exhibition will be on view Mondays through Fridays from 8:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m from now through September 18. Aperture: Photographs is sponsored by the 1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery, in partnership with Jones Lang LaSalle, as a community-based public service.

1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery

Artist Michael Flomen explains his process behind his print New Born, 2010

Colin Thomson and designer Linda Florio in front of Penelope Umbrico’s Suns from Flickr series, 2014

Michael Hejtmanek, President and CEO of Hasselblad Bron Inc. and Aperture Executive Director Chris Boot

A guest views David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Buffalos), 1988

Guests converse in front of Hank Willis Thomas’ Black Power, 2006

Aperture Trustee Celso Gonzalez-Falla with Chair of the Board of Trustees Cathy Kaplan and Executive Director Chris Boot

Artist Michael Flomen, guest and Aperture Paul Strand Circle Member Philippe Laumont

Aperture Deputy Director Sarah Anne McNear with Aperture Paul Strand Circle Members David and LaVon Kellner

The post At the Opening of Aperture: Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 30, 2015

The PhotoBook Review: Collecting the Japanese Photobook, Part Two

Manfred Heiting is an inveterate and encyclopedic collector of the photobook. He began his career as a designer before gaining experience and acclaim as a curator, editor, scholar, and connoisseur of the genre. In 2013, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, added his library of books to their extensive set of four thousand prints from his collection, acquired in 2002 and 2004. This addition will include more than twenty-five thousand titles from around the world, including Germany, the Soviet Union, France, the United States, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, and roughly two thousand volumes from Japan. As a committed outsider seeking insight via the Japanese photobook, Heiting’s interest in the form operates complementarily to historian Ryuichi Kaneko’s inside track [as discussed in App Issue 9]. In addition to the forthcoming volume Soviet Photo Books 1912–1941 (Steidl, 2015), Heiting is also at work on the book The Japanese Photo Book: 1912–1980. The following conversation with Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review, appeared in The PhotoBook Review 008.

This article originally appeared in Issue 10 of the Aperture Photography App.

Lesley A. Martin: How and when did you first become interested in the Japanese photobook as a particular area of collecting?

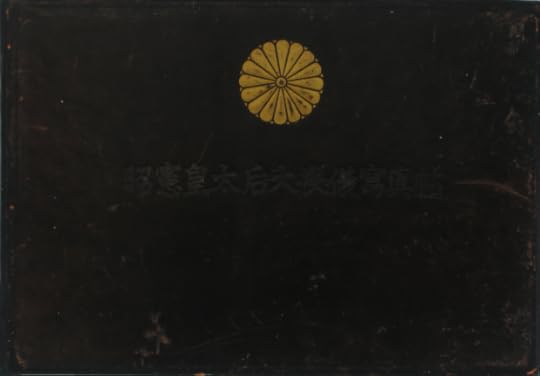

Manfred Heiting: I started collecting Japanese photography in 1972 after a visit to Tokyo to meet with Goro Kuramochi, a curator and editor who later became a friend. He introduced me to a few photographers: Ikko Narahara, Eikoh Hosoe (who helped me a lot), Teiko Shiotani, Shoji Ueda, and others. I knew at that time that vintage prints were not part of the Japanese narrative, and during that visit I only bought a few contemporary prints from those photographers I met. I also acquired some books as part of my reference library, useful to understanding the work of the photographers; they were not seen as “collectible” at that time. It was only at the beginning of the 1990s that my interest in [photographers’] books became more focused. I see 1912 as a decisive starting point for my collection of Japanese books, based on a photobook by Kazuma Ogawa that documents the Meiji emperor’s funeral that year (which traditionally took place at night), Photographic Album of the Imperial Funeral Ceremonies. Floodlights had not been invented yet—just the magnesium flash for close range. The Japanese government purchased all the magnesium they could get and placed it alongside the road so that the long, nighttime procession could be photographed. The images are quite impressive, and I think that is a fitting beginning.

For now, however, I’ve stopped looking at books produced after the 1980s. I call most Japanese photobooks produced after that period “Eastern art for Western taste.” Before the 1980s (and in particular before the 1970s), publishing photobooks was an elaborate and expensive undertaking, and there was only a small market for them. In other words: before a publisher would take the risk, a book had to offer a very good value proposition, featuring the most acclaimed work from well-known photographers, and be well-designed and technically well-executed to ensure that the book would be a commercial success.

In the 1980s, more museums began to show photography, and more publishers saw the photobook as a new and attractive market. More buyers gave the publishers confidence to invest in photobooks, and English became the accepted language of choice for many of those publications. And when the museums rediscovered photography, the most common type of photobook became the catalogue, designed to replicate the individual print on the gallery or museum wall. You saw less diversity of printing and materials, less design, less individualistic layouts—just more and more color surrounded by more and more white paper. In my opinion, these are less “book” than just “printed, colorful paper.” This was the situation in the U.S. and Europe in the 1980s, which soon arrived in Japan and took away the most admired—and different—concepts of the Japanese photobooks of the 1960s and 1970s, with their unique design and photographic languages, and their high-quality printing. Photographers and publishers both had their eyes on the international market and adapted to our tastes in order to sell them to us. There are exceptions of course—but I shy away from most of the contemporary Japanese books.

Kazuma Ogawa, Photographic Album of the Imperial Funeral Ceremonies, Top: standard edition; bottom: palace edition. Privately published, 1912

LAM: What were your criteria for buying books when you started to collect in this area? Has that criteria changed over time?

MH: The criteria has not changed much—I am always interested in “complete-as-published” volumes—but the understanding and knowledge of what that means regarding Japanese photobooks has increased, and with the network of trusted local advisors, I now know more of what I am still missing.

LAM: Beyond its completeness and condition, what is it you look for when you buy a book, especially a Japanese photobook?

Are you interested in the design, in the quality of the pictures? Perhaps the real question: do you need to fall in love with a book in order to buy it?

MH: Of course, all of the above. As I have explained before: I am talking about the printed B-O-O-K (I have collected original photographic prints before and have closed that

chapter). Therefore, I am interested in a “book” with all its unique parts and attributes: for its particular photographic language and authorship, its design, layout, size, printing, and binding quality—and that’s for each period and country. If I like a photographer’s work or think that the subject and style warrants “preserving,” I look for every book from a photographer, from every period and most subjects—provided that the book and all its attributes are of a high quality. I think this is a different way of falling in love with a book, but also an admiration for the complete result intended by the makers.

LAM: Are there any particular themes or motifs that you have found of interest or that especially define the Japanese photobook?

MH: Yes. Without being dogmatic, I categorize twentieth-century

Japanese photobooks in four distinct periods.

The pictorial period: This includes publications from amateur photo clubs (which have played an important role in Japan). Also, pictorialism extended longer in Japan than in Europe and the U.S., lasting until the beginning of the 1930s.

The avant-garde: Including the surrealist advertising and Bauhaus-influenced photobooks and advertising of the 1930s (these are not easy to find).

Propaganda: Many books and magazines were published by the imperial government, the military, and the occupying authorities in Manchuria and elsewhere. These materials are quite substantial and more “impressive” than European fascist-propaganda photobooks—but fall a bit short of the creativity

seen in Soviet propaganda photobooks.

The 1960s and 1970s: This is the best-known and most widely admired period of Japanese photography and photobook making. During this period, books were it! And the quality of the photography, aesthetics, and production (mostly in sheet-fed gravure) are unmatched in other parts of our photobook culture.

LAM: The canon of the photobook has begun to solidify in the past ten years. Are there any Japanese photobooks that you feel have been left out of the surveys or best-of listings?

MH: Best-of listings are very bad for collectors who want to do more than just invest in the top/best/rarest of books. The market aspect has certainly helped to focus on a particular period or culture and has brought a lot to light, but other than “the top ten”—or, in particular, prewar photobooks—we are still mostly in the dark, or the books are unrecorded. The Japanese protest photobook is certainly on everyone’s radar, but that does not mean that we know much of what we are after. Robert Hughes, the most celebrated art critic of the later twentieth century,

famously stated, “What strip mining is to nature the art market has become to culture”—this fits perfectly into our field as well.

LAM: How would you define the relationship between connoisseurship and scholarship in your role as a collector?

MH: In my particular situation, my quest and my goal cannot be separated: I seek to combine both connoisseurship and scholarship. I basically collect the twentieth-century photobook (more precisely the “printed photobook,” from about 1886 until 2000). Because of the two world wars, the twentieth century is a difficult period for the photobook—so much was produced and so much is lost forever, including most of the subject matter, and history needs to be preserved. I see the photobook in the twentieth century as one of the most important mediums in our culture and of that part of history, and recording it as a very important task for scholars, libraries, universities, museums, and collectors alike.

I also think that only a private collector is more “privileged” and can do both—if he or she is prepared to spend the time and money to accomplish both of these tasks. At the outset, one has to decide for whom and where the results will be made, deposited, and placed to keep it all together. In my case, I decided that some time ago. No one can take things with them.

Tap here to find The PhotoBook Review on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post The PhotoBook Review: Collecting the Japanese Photobook, Part Two appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers