Aperture's Blog, page 155

August 10, 2015

“Conflict” at Krakow Photomonth 2015

Writer Aaron Schuman reports from this year’s edition of Krakow Photomonth, an annual photography festival held in institutions, galleries, and spaces around the city each June. Schuman reflects on this year’s theme of conflict.

Josef Koudelka, Czechoslovakia, August 1968; from the series Prague, 1968.

Established in 2002, Krakow Photomonth has grown from a rather rambunctious and rebellious upstart—packed into disused buildings, artist squats, crowded bars, and burgeoning galleries—into one of the most ambitious and engaging festivals on the photography calendar, now staged in some of the city’s most prestigious museums and exhibition spaces. In recent years, its various programs have consistently presented thoughtful and challenging shows on a wide range of themes, including ruminations on artistic use of a fictional identity, in ALIAS (curated by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2011); to experimental takes on Photography in Everyday Life (curated by Charlotte Cotton and Karol Hordziej, 2012); to investigations into The Limits of Fashion (curated by Paweł Szypulski, 2013); to explorations of the complex relationship between photography and information in Re:Search (curated by myself, 2014). This year’s edition, which ran from May 14 to June 14 and was devised by Wojciech Nowicki, a celebrated Polish essayist, novelist, critic and curator, revolved elegantly and elliptically around the central theme, conflict.

Festival poster for Krakow Photomonth 2015

In part, the seventy-year-old specter of Soviet aggression—resurrected and made real again with the current crisis in neighboring Ukraine—loomed subtly (and at times, not so subtly) over the festival. At Starmach Gallery, a renovated nineteenth-century synagogue that now serves as one of the city’s most distinguished commercial art spaces, Josef Koudelka’s legendary body of work, Invasion Prague 1968, served as a reminder of the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, and the non-violent protests and impassioned resistance that erupted in the streets of Prague during the week that followed, which ultimately failed to prevent the Russians from ostensibly ruling over the country for the next thirty years.

Frederic Lezmi, Taksim Calling (self published), 2013; installation view of TRACK-22: Photobooks on Conflicts at Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art (photograph by Aaron Schuman)

In Track-22, curated by the publisher and founder of The PhotoBook Museum, Markus Schaden, and held in the imposing 1960s brutalist masterpiece, Bunkier Sztuki, photographic engagements with more recent political uprisings and protests surfaced, including those staged in Istanbul’s Taksim Square (Taksim Calling by Frederic Lezmi, 2013), Kiev’s Independence Square (Maydan: Hundred Portraits by Émeric Lhuisset, Barricade by Julia Polunina-But, and Euromaidan by Vladislav Krasnoshek and Sergiy Lebedynskyy, 2014), and elsewhere. The dynamic installations of these series, and several others, specifically called attention to the potency of contemporary photobooks that deal with such matters, which Schaden argued “counter anonymous and delocalized media coverage . . . have a distinct authorship, and are capable of tracking and witnessing conflict from a genuine point of view . . . through visual dramaturgy and materiality.”

Indre Serpytyte, I, 2009; from the series Forest Brothers

Indre Serpytyte, 7 Margio street, Alytus, 2014; from the series Former NKVD, MVD, MGB, KGB Buildings

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow (MOCAK), a stunning new arts complex that opened in 2010 on the site of Oskar Schindler’s Factory, was 1944–1991 by Indre Serpytyte. Including two bodies of work—Forest Brothers (2009) and Former NKVD, MVD, MGB, KGB Buildings (2009–15)—the exhibition testified in a discreet yet powerful manner to the Lithuanian dissidents and guerrillas who fought against Soviet rule throughout the second half of the twentieth century, despite being subjected to imprisonment, torture, and murder by the Soviet security services.

Joanna Piotrowska, XXIII, 2013–14; from the series Frowst

Elsewhere Nowicki’s take on the concept of conflict stretched well beyond the boundaries of politics and war, offering refreshing possibilities as to what could be deemed “conflict photography” today. “Conflict does not mean only armed clashes,” Nowicki explained in the festival’s introductory statement. “Often, conflicts are played out only in someone’s imagination, and consist of gestures, or even memories, that are difficult to capture.” Such sentiments surfaced in surprising ways in Joanna Piotrowska’s Frowst (2013–14), exhibited at the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow, which portrays suppressed yet discernable familial tensions through the physical contortions and awkward body language of her subjects, all of whom are immediately related.

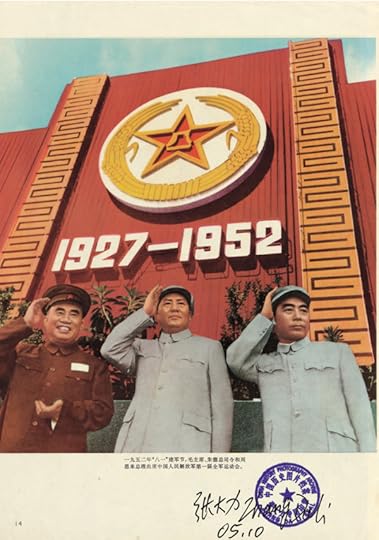

Zhang Dali, The First Sports Meeting of the People’s Liberation Army, 1952. (from the series, A Second History)

At the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology, Zhang Dali’s A Second History explored the doctoring of official photographs in Mao-era China, forensically dissecting the menacing and ridiculous ways in which images deemed in conflict with the Party line were manipulated in order to reflect an acceptable Maoist “reality.” The most unexpected interpretations of the festival’s theme came with Paweł Szypulski’s exhibition, Foreign Body, which brought together a trove of materials—ranging from video clips from Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda, to Leni Riefenstahl’s book, The Last of the Nuba, Kodak’s “Shirley” color-test cards from the 1950s to the 1990s, a 1972 Playboy magazine that served as the source of the standard referencing photograph (dubbed “Lenna”) used in testing image compression algorithms, to a YouTube video entitled HP Computers Are Racist, to Eugène Atget’s photograph of the Callipygian Venus (“Venus of the Beautiful Buttocks”) at Versailles, to footage of Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston topless, and more—presenting a stunning example of curatorial choreography in which intriguing histories and uncomfortable relationships between gender, race, photographic technology, and visual culture at large were exposed in the most entertaining and enlightening of ways.

Ultimately, Krakow Photomonth 2015 represented how a photography festival, when given the freedom to embrace ambition, complexity, and experimentation, can offer thoroughly new insights and engage audiences far beyond expectation. The experience was both an inspiring and a dizzying one, raising difficult questions and contradictions, which likely left visitors feeling satisfyingly conflicted—and surely that was the whole point.

The post “Conflict” at Krakow Photomonth 2015 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 7, 2015

Letters from Sally Mann On Process

The following letters from Sally Mann to Melissa Harris, now editor-in-chief of Aperture Foundation, originally appeared as a part of an interview on Mann’s process in Aperture #138, “On Location,” in 1995. This month, Aperture reissues the paperback version of Mann’s Immediate Family, originally published in 1992, on the occasion of this year’s release of her autobiography, Hold Still. This fall, Aperture Foundation launches the Aperture Digital Archive, giving subscribers access to every issue of Aperture magazine to subscribers.

Sally Mann, Torn Jeans, 1990 © Sally Mann

July 1, 1994, Lexington, Virginia

Dear Melissa,

I sense that there’s something strange happening in the family pictures. The kids seem to be disappearing from the image, receding into the landscape. I used to conceive of the picture first and then look for a good place to take it, but now I seem to find the backgrounds and place a child in them, hoping for something interesting to happen.

In the last picture I took of the three of them together, they are actually just blurs, attenuated by the heat waves from a quenched bonfire. In the foreground the focus is on some determined little mongrel flowers.

Judging by the scrutiny we were subjected to over the last few years, I expect much will be made of the distance springing up in the pictures between the children and me. But, in fact, what has happened is that I have been ambushed by my backgrounds.

They beckon me with just the right look of dispossession, the unassertiveness of the peripheral. These are the places and things most of us drive by unseeing, scenes of Southern dejection we’d contemplate only if our car broke down and left us by the verdant roadside.

I like to think that these are the kind of pictures Eugène Atget would have gotten if he had pivoted his camera away from the monuments and toward the unalluring underbrush. In fact, sometimes I do just that: under the dark cloth I rotate the camera on the tripod and watch the randomly edited scenes pass across the milky rectangle.

But it’s not that they are easy, to take or to look at. Compared to the family pictures, which had the natural magnetism of portraiture, these are uncompelling. Unlike the stare of a self-possessed child, these pictures will not draw you across the bleached parquet.

They’re a little scary that way. The family pictures seemed to strike a powerful chord in people and it’s a chord I could keep plucking as long as I have children and film. But here are a few of the landscapes: see what you think.

Love from everyone.

August 29, 1994, Bequia, St. Vincent

M—

I’ve had you on my mind all these weeks. Why? Because I’ve been taking hundreds (3? 4?) of pictures—and half of them are family pictures. Up close. That kind of blows the theory I wrote to you about the diminution (in number and importance) of the recent family pictures, doesn’t it? Thinking about the landscapes more as an extension of the family pictures than a replacement seems more accurate. After all, they spring from the same source.

xxx to you

August 30, 1994, Bequia, St. Vincent

M—

Thanks for faxing back. I picked it up this morning on my way back from the village clinic. Now that was an experience! I was a little daunted by the line that had formed by the time we got there (8:15, after a 1/2 mile walk down from the cliffs) . . . but our connections were good and the local store owner interceded for us. It turns out Emmett has a ruptured eardrum and an ear infection. He also has a marriage proposal from a toothless 80-year-old widow who insisted, patting the bench next to her, that he sit there wedged up against her. I was happy to give him away to her, I said, provided that she had a big house and we could all come and live with her. She seemed quite pleased with this arrangement and stroked his brown shoulder and sang bold songs to him while we waited. As we left after the appointment, I told her that he was damaged goods and she deserved better. (But if she’d had a big house I might have thrown Larry in to make up for the bad ear and sweeten the deal.)

I love it here. There’s a line in Turgenev’s Virgin Soil . . . it’s a suicide note, and the entire note is “I could not simplify myself.” I think that might have been my note if I had not come here.

Just the picture-taking thing: it’s all different now. I think I was working out my next step when I saw you in Lexington, and the landscapes we looked at were the first sign of new growth. Now I’m freely moving back and forth between the family pictures, some new work with Larry, some self-portraiture and the landscapes. The boundaries of all these projects seem more permeable now—they all feel like family pictures in a way.

The pictures of the children, and, to a degree, the pictures of Larry, come in moments of epiphany, serendipity. The landscape work is a lot more cerebral, less dependent on chance. The landscape is teasingly slow to give up its secrets. There it is, sprawled across our vision, always out there. Just the way the children were there, underfoot, seeming to be so accessible.

But neither of them proved to be: to the contrary, their complexity was Gordian. I wasn’t sure how to puzzle it out. I suppose I could have tried to untie it or cut it, like Alexander. But I chose to look at it, and photograph its defiant intricacy.

Working on the landscapes, I came back to the elemental, basic presentation; the solitary tree, the light-struck noonday field. As a consequence, they are often simple pictures, possessed of a kind of naiveté that I thought I had lost. I am less afraid of that naiveté: as Niall once remarked to me, naiveté in art is like the digit 0 in math; its value depends on what it’s attached to.

I still want to make a beautiful image. Since I’ve been here I’ve read a piece by Dave Hickey in which he applauds the subversive power of beauty. In this article Hickey argues for the use of beauty as a persuasive agent in conveying the artist’s agenda. I find this more Ciceronian approach between agency and agenda far more appealing than the Modernist’s distinction between form and content.

I have found tangible evidence that within this life’s sweet tedium reside certain truths: that nothing attains maximum beauty until touched with decay, that the vulgar and the miraculous can be one. For years I’ve passed this evidence by: it was invisible through overfamiliarity.

I look now at all hours, but I mostly find the pictures in the marginal times of day, that hour of mystery before night. Toning them, and usually printing them dark, gives them more of the feel of the actual moment: in some cases impenetrable and mysterious, but in others crazed with tawny light.

The landscapes need to be seen in context. They are intended to be every bit as revelatory and celebratory as the family pictures. Michael Lesy once wrote that if a picture is taken out of its context of life and love, it will appear enigmatic and void of meaning. But, when restored to its narrative and iconographic context it becomes “the capstone of a pyramid whose base rises from the human heart.” These landscapes belong with the family pictures; they provide the background and the history and the scale. They give them dimension. If the family pictures are flashes of the finite, these landscapes offer them residence in the languid tableaux of the durable.

Warm love,

S.

September 14, 1994, Lexington, Virginia

M—

It occurs to me that since this is an article on process, I might as well tell the rest of the story. It’s true that I shot four hundred negatives. But fifty percent of them were ruined by the humidity. It turns out that the gelatin layer was soft because it was fresh film.

When I got ready to develop them, I noticed that they were stuck together in little pinprick areas and I teased them apart. But the friction of the bond separating caused a microburst of electricity. They look as starry as the night sky. Most of them weren’t good pictures anyway; my usual 2% success ratio was in play, but there are a few beauties that were ruined.

This is process, isn’t it?

Love, as always,

Sally

Click here to find Immediate Family on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Letters from Sally Mann On Process appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 6, 2015

Staff Picks: Summer Exhibitions

Aperture editors and staff select the photography exhibitions we’re seeing around New York City this summer, from MoMA to the Guggenheim to Chelsea’s galleries. Follow the Aperture Beat column for the latest on what’s going on inside Aperture Foundation now.

This article originally appeared in Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App.

Yayoi Kusama, Mirror Performance, New York, 1968. Photograph by Shunk-Kender © 2015 Yayoi Kusama. Photograph: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Art on Camera: Photographs by Shunk-Kender, 1960–1971 at the Museum of Modern Art showcases works by the photographers Harry Shunk and János Kender, who collaborated under the name “Shunk-Kender.” By presenting the duo’s photographs of artworks and performances by their contemporaries, the exhibition looks at the two photographers’ relationship with the avant-garde, specifically of the 1960s. The relationship is indeed a dynamic one. Sometimes Shunk-Kender acted as a surrogate to the artist; the duo enacted performances as directed by the artist and then immortalized the fleeting moment by documenting it with their cameras. For instance, for David Askevold’s untitled 1971 work from the project Pier 18, the two played a game of hide-and-seek while recording it through photographs. Other times, they were witnesses to scandalous art scenes, as with their images of Yayoi Kusama’s The Anatomic Explosion (1968), a nude performance on the Wall Street. Their photographs are not only a document of the contemporary art scene of the period but also an active participation in it. —Yun Sun Lee, publicity and events Work Scholar

Lorraine O’Grady, Art Is. . . (Cop Eyeing Young Man), 1983/2009. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York © 2015 Lorraine O’Grady/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

There is no shortage of fantastic work up at the Studio Museum in Harlem this summer, ranging from vibrant painting to immersive installations. Lorraine O’Grady’s Art Is . . . uses photo-documentation to take viewers back to a public performance at the September 1983 African-American Day Parade in Harlem. Using large empty frames with the caption “Art is…”, O’Grady turned the parade into a statement about the vibrancy of Harlem’s community and the everyday present of artistic selves. Paraders of all ages stop and pose in front of the fantastical frames, adding exhilarating flare to the day’s festivities. Several images show young black women glaring through the frames at on-duty white police officers; these women stare defiantly, challenging the authoritarian gaze the viewer has come to expect. These photographs archive a powerful event that bleeds public spectacle, performance art, and photography into a fantastic and poignant showcase about one day over twenty years ago in New York City, which proves striking at the current moment. —Joshua Herren, development associate

Storylines at the Guggenheim incorporates the work of contemporary artists, including photographers such as Catherine Opie, Zanele Muholi, and Ryan McGinley, alongside responses from prominent writers, reinforcing the narratives inherent in their work as well as inspiring entirely new tangents. For those who can’t experience the work in the twirling galleries of the Guggenheim, the website offers an equally, if not more engrossing experience. Images float on an open plane where one’s attention can roam freely from work to work within the confines of a screen—after selecting an image, we find Edwidge Dandicat poems paired with Muholi’s Faces and Phases series, or Opie’s Self-Portrait/Nursing (2004) is set off by poems by Denise Duhamel. —Alexandra Pechman, online editor

Meryl Meisler, Jive Guy on Williamsburg Subway, Brooklyn, NY, 1978

I’m hoping to check out Purgatory & Paradise: SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City at Black Box Gallery in Brooklyn. The photographs are by Meryl Meisler, who has been photographing the New York nightlife scene since the ’70s. This exhibition, on view until October 12, juxtaposes images of her home life on Long Island with some never-before-seen street and nightlife images. This includes shots of Fire Island, the Rockettes, the Hamptons, Go-Go-Bars, punks, CBGB, and even Girl Scouts. —Elena Tarchi, publicity and events associate

Follow the Aperture Beat column for more behind-the-scenes looks at Aperture Foundation.

The post Staff Picks: Summer Exhibitions appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 5, 2015

Highlights from From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola

Roxana Marcoci and Sarah Meister as told to Paula Kupfer

Grete Stern, Sueño No. 1: Artículos eléctricos para el hogar (Dream No. 1: Electrical Appliances for the Home), 1949 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola.

When German artist Grete Stern and Argentine photographer Horacio Coppola met at the Bauhaus in Berlin in 1932, Coppola had already made incursions into photography and film while Stern had done the same with typography and graphic design experiments. They became a well-known couple within the intellectual scene of Berlin, but when the Nazi party began to gain power, they departed for London, where they married, and later arrived in Argentina. Intellectual and literary circles in Buenos Aires celebrated their unique visions, and their first exhibition, in 1935, at the editorial office of the magazine Sur, was heralded as the arrival of modernism in Argentina. A current exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, presents their work separately, in keeping with their different practices and careers, but highlights instances of overlap: their collaboration on several books, and their experimental, if short-lived, graphic design and photography studio. After the couple divorced in 1943, Coppola abandoned photography, while Stern continued to make photographs for several decades and surrounded herself with contemporary artists. Here, curators Sarah Meister, who focused on Coppola, and Roxana Marcoci, who researched Grete Stern, offer comments and insights into key works in the exhibition. —Paula Kupfer

This article originally appeared in Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App.

Horacio Coppola. Still Life with Egg and Twine, 1932 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

Sarah Meister: The first pictures by Coppola that I ever saw came in through the Thomas Walther Collection. We thought, that’s funny, an Argentine at the Bauhaus. This was in 2001 and we didn’t really know what to do. . . . We were pigeonholing him with the Bauhaus and not thinking of him as an independent artist. Then I started working with the Latin American–Caribbean Fund, which was helping support acquisitions of Latin American photographers, and with our C-MAP group [Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives in a Global Age Initiative, a global research initiative at MoMA]. I had the opportunity to travel to Brazil, to Argentina, to Mexico, and I started to see who the major figures were. The question became: how do you tell these alternative modernisms that are less familiar to an American public?

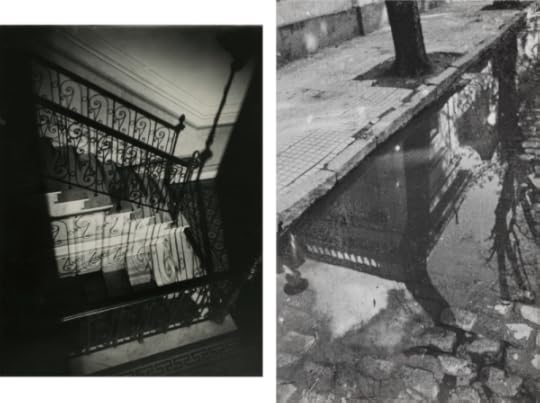

LEFT: Horacio Coppola, Untitled (Staircase at Calle Corrientes), 1928 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola; RIGHT: Horacio Coppola, “¡Esto es Buenos Aires!” (“This is Buenos Aires!”) (Jorge Luis Borges), 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

SM: These are pictures (above and below) from before Coppola’s first trip to London. You already see the modernity. Then he gets a Leica and . . . these are what [publisher] Victoria Ocampo sees and publishes in Sur: “a modern vision of a city.” The problem with previous scholarship was that it put the achievement out there, but until you impose a strict chronology you can’t learn the sources.

Horacio Coppola, Buenos Aires, 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

This is one photograph that I love (above). I thought this was maybe a 3-by-4 negative, a contact print, since it’s unbelievably precise. I knew he’d borrowed his brother’s camera, but I didn’t know if this was in 1931 before he went to Europe or afterward. But I knew about the wonderful binders he made, of his favorite pictures—he literally took his 35mm-negative contact prints and pasted them in. Then I knew for sure it was a 35mm negative and I could place it in the context; I could see what he made before, what he made after. Like all good art history if you actually do your homework . . . and take the time to piece it together, it’s amazing, like detective work in the most satisfying way.

Installation view of From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by John Wronn © 2015 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

SM: This wall shows Coppola’s photographs from his seminal book Buenos Aires (1936). I thought I would never in a million years hang this many pictures on a wall but actually . . . there was a moment in the installation where I thought, No, embrace it. Let the obelisk be the loose fulcrum, go from day to night. I knew I didn’t want to do a “day wall” and a “night wall.” I realized a few people might not get it, which is fine.

Installation view of From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by John Wronn © 2015 the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Roxana Marcoci: For Stern, the show opens with this wall, which establishes the protagonists: we see Coppola, Ellen Auerbach, and Walter Auerbach, and others. Basically, Stern comes to Berlin extremely young, at the age of twenty-three, in 1927. Before that, she had already established a commercial studio in her hometown, and experimented with typography and advertisements; she was extremely precocious. So she comes right then to Berlin—which was the intellectual and cultural capital of central Europe—we’re talking roaring ’20s and the Weimar Republic. She becomes the very first student of Walter Peterhans, and then a year later, Ellen Rosenbach [later Ellen Auerbach] also becomes his student. [Auerbach and Stern] were very progressive. Both had been living with their middle-class, bourgeois families and they went to study and to Berlin. They experiment with film. And they all live together, with their lovers at that time, who eventually become their husbands.

LEFT: ringl + pit, Komol, 1931 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola; RIGHT: ringl + pit, Soapsuds, 1930 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: Stern’s sense of very close observation brought her to Peterhans—he is about the New Objectivity, the Neue Sachlichkeit strain in the Bauhaus, of very close observation. The other part of her is the sense of experimentation, of whimsicality, that comes through in the advertisements. She and Auerbach decide to form the ringl + pit studio. They are playful—they take [the name] from their nicknames from when they were children—Stern was Ringl, Auerbach was Pit—but also impressed both commercial and avant-garde loyalties. They decide to cosign the work; they spoof the cliché of the “master”—these are women who are working both in front of and behind the camera. For Stern, the whole psychoanalysis aspect in her work, the idea of opposition, of where you stand from and where you take the picture from, is a very feminist idea. While she never was an activist she was always affiliated with feminist and antifascist causes.

In this picture, for instance (above, left), there is this engagement with what is called the “Neue Frau” (new woman): she was considered the first global icon of modernity, as a woman and as an image of a woman. (In France, Coco Chanel was an example, and there’s the American flapper, too.) What’s nice about what they do is that they scramble a lot of gender signifiers and sartorial cues.

And in this one (above, right), they say they can’t even remember who took the picture and who is the hand. So this mix of animate and inanimate, which was dear to the surrealists, is also at play here. Interestingly, this [picture of soap] is one that Christopher Williams, with whom I did a previous show, was looking at. He has a picture of soap, too.

Grete Stern, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait), 1943 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: This is one of the most revolutionary self-portraits. It’s a self-portrait as a representation in a mirror—she doesn’t even appear in it—and because of the combination of feminine and masculine props, the floral arrangement, which are also in other pictures of her, but also the mathematical instruments and then the mirror and the lens, which are visible in the foreground. Both mirror and lens function as tools of self-analysis.

RM: They [Coppola and Stern] divorced in 1943. They’d built a house, by Vladimiro Acosta, a very progressive architect, in the Ramos Mejía [neighborhood]. Grete kept the house, and it would become a mecca for a whole new group of writers and artists, including Madí.(Madí stands for materialismo dialéctico; they were a leftist group of artists who stood in opposition to Perón.) She designs their logo (above): she takes the existing neon sign for Movado watches and superimposes the three other letters in 3-D fashion, over the obelisk, partly because the obelisk is an abstract signifier and the Madí group was interested in abstraction. This Madí photomontage is the first acquisition that I made a few years ago—before we started working on the exhibition.

Grete Stern, Sueño No. 28: Amor sin ilusión (Dream No. 28: Love Without Illusion), 1951 © 2015 Estate of Horacio Coppola

RM: The last room is dedicated to the Sueños, from 1948 to ’51. Stern starts contributing on a weekly basis to the magazine Idilio. The rest of the magazine is these fotonovelas (photo–soap operas), very kitsch, but her work is very strong. The rubric “Psychoanalysis Will Help You” was written by two sociologists and a psychoanalyst under a pseudonym. She was making the photomontages on the basis of the analysis and the dream. What is interesting is that often her photomontages stand as a form of resistance to their interpretation of the dreams. This is a country where psychoanalysis has such a strong foot. Perón was against all of it; the psychoanalysts were blacklisted. This could only appear in a women’s magazine.

It’s interesting that in all these pictures the main protagonist is a woman, and the situation is always one of conflict; she has this very filmic mode of telling a whole narrative within a frame. This is where [the exhibition] ends, with her Sueños, because here, more than in any other bodies of work, the lessons of the Bauhaus laboratory—obviously advertisement techniques, and even typography—merge with this more Latin American, Borgesian sense of rupture and montage and different type of storytelling. When two cultures meet in this way, you can talk about a transnational modernist culture.

From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires runs through October 4 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The post Highlights from From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 4, 2015

A Recap of Aperture’s Summer Soirée

Aperture Foundation creative director Lesley A. Martin introduces photographer Matthew Pillsbury to Summer Soirée guests. Photo by Max Mikulecky.

On July 22, photographers and friends of Aperture, as well as Aperture’s executive director, Chris Boot, and creative director, Lesley A. Martin, gathered to celebrate summer and photography at the Aperture Summer Soirée. Aperture trustees Jessica Nagle and Roland Hartley-Urquhart hosted a party with cocktails and hors d’oeuvres on the terrace of their Manhattan home, where guests had the opportunity to speak with Matthew Pillsbury, whose monograph City Stages was published by Aperture in 2013. Other Aperture photographers in attendance included Hannah Whitaker (Photography Is Magic, forthcoming in September 2015), Richard Renaldi (Touching Strangers, 2014), and Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao (Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York, 2014).

Pillsbury presented recent work (courtesy of Benrubi Gallery) that he made on a trip to Japan. He discussed his early photographs and his turn to color. “It challenged me to work in a completely different way,” he said. “I felt like I had this freedom given to me.”

Of one photograph on view, depicting a ramen museum, he noted, “I saw this one room and said, ‘It has to be in color.’” Known for his black-and-white studies of modern urban environments, Pillsbury discussed this new approach. “Suddenly, in Tokyo, there were so many things that needed to be in color. . . . It’s a whole new language.”

Aperture Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization that relies on the generosity of individuals for support of its publications, exhibitions, and public and educational programming. Click here to learn more about becoming an Aperture Member.

Matthew Pillsbury speaks about the process of making Cup Noodles Museum, Yokohama, Tokyo, 2014 (courtesy of Benrubi Gallery), on a trip to Japan.

Jessica Levy with Joshua Greenberg of U.S. Trust, Bank of America, Andrew Craven, Aperture Foundation executive director Chris Boot, Aperture Foundation trustee Jessica Nagle, and Rodger Hicks

Aperture Foundation creative director Lesley A. Martin and Christiane Fischer

Jeffrey Peabody of Matthew Marks Gallery, with Aperture trustees Jessica Nagle and Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy

Tony White, Doug Friedlander, and guest

Erika Basave, Whit Williams, Jr., and Matthew Pillsbury

All photographs © Max Mikulecky.

The post A Recap of Aperture’s Summer Soirée appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 31, 2015

Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 13:

● An excerpt from Edward Weston’s Flame of Recognition.

● A report from Krakow Photomonth 2015.

● Highlights from From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola.

● Aperture staff picks for summer exhibitions.

● From the archive: an interview with Richard Learoyd.

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 13 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 29, 2015

Excerpt from Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment

One of the last projects by Mary Ellen Mark (1940–2015), Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment, the latest book in Aperture’s Workshop Series gathers some of the acclaimed documentary photographer’s favorite portraits alongside her commentary about where she found her subjects and how the now-recognizable images came to be. Mark passed away in May of this year, after the completion of this book and Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, to be released this fall. From her early magazine assignments to the series Streetwise and Prom, she reflected in the book, excerpted below, on decades of iconic photographs of everything from everyday life to the bizarre, taken around the world.

This article originally appeared in Issue 12 of the Aperture Photography App.

Craig Scarmardo and Cheyloh Mather at the Boerne Rodeo, Texas, 1991

Let Things Happen

This photograph was shot in the early ’90s on assignment to photograph small-town rodeos for Texas Monthly magazine. It was a great assignment for me (given by a wonderful art director, D. J. Stout), and we found six or seven towns with rodeos. We timed things to shoot seven rodeos in about three weeks. I had never been to a rodeo before. Everything about it was fascinating, and very Texan.

These boys look a little bit like brothers, but they aren’t. They’re close friends and were bull riders. It’s one of the most dangerous sports in the world, really terrifying. I saw countless men and boys being thrown and stomped on by bulls.

I got to a point where I couldn’t watch anymore and began photographing people on the sidelines. This was shot on 4-by-5, so I definitely directed them to look at me. I probably did a Polaroid test-shot first, but that’s how they decided to stand on their own. They were excellent bull riders; you can tell by their attitude that they knew it too. They were macho beyond their years.

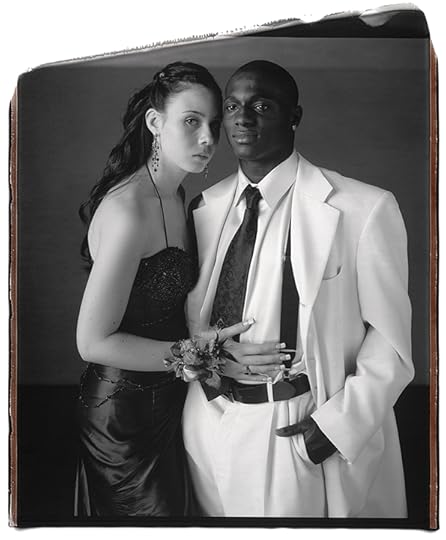

Samantha Monte and Khalil Samad, Staten Island, New York, 2006

Take Control

I was looking for another project to do with the 20-by-24 Polaroid camera, like Twins, which I finished in 2002. I feel sort of let down after I finish a big series—I firmly believe that I’m only as good as the next thing I do. I’m not interested in going back but in going forward. I miss the excitement—that amazing excitement—of starting a new project, which is why I am a photographer. The prom seemed right for my next project because I was interested in the costumes, the rituals, the choice of partner. I felt the need to look at them closely. I knew it would be a good idea. . . .

With the 20-by-24 Polaroid camera, I didn’t have the luxury of shooting lots of frames. The film costs a fortune, and there’s no postproduction. The picture comes out of the camera finished, so the lighting, the set up, everything, has to be perfect during the shot. You have to take into account all the details. I used the same backdrop and setup for each picture. I had to make a decision before the shot and stick to it: I’ll shoot from this distance, and have this idea for the photograph. I couldn’t take lots of pictures and then decide because I had so few frames to shoot.

Ram Prakash Singh with His Elephant Shyama, Great Golden Circus, Ahmedabad, India, 1990

Look for Mystery

Fiction writers are lucky in the sense that they can imagine anything. I am not good at imagining things; I’m most interested in finding the strangeness and irony in reality. That’s my forte.

This picture of the elephant and his trainer is one of my most well-known pictures from the Indian circus. It has a strong composition, with the trunk making a circle around the trainer. He had the elephant perform that for me (I think he was showing off). But what makes the portrait work so well is the elephant’s expression. I took several pictures of this act, so much so that the elephant got fed up. He looked at me from the side as if to say, “Ugh, Mary Ellen, that’s enough. This is your last frame.”

Sometimes it’s better to go for a subtle image rather than a sensational one. Simple and direct images can work, but look for what has some mystery to it. I couldn’t have planned such a sly look from the elephant and how it would contrast with the seriousness of the trainer. Afterward, the trainer insisted that I get my picture taken with the elephant’s trunk around me. It was very heavy!

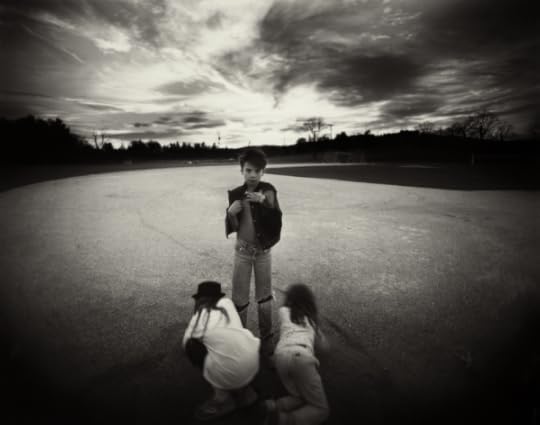

Amanda and Her Cousin Amy, Valdese, North Carolina, 1990 © Mary Ellen Mark

Build the Frame

There was a school for problem children in Valdese, North Carolina, and I went there on assignment for LIFE magazine. I thought all the kids were great. Nine-year-old Amanda was very intelligent and very naughty. She was, of course, my favorite. I took a lot of pictures of her, and one day I rode the school bus home with her. I was curious about where she lived. She got off the bus in front of her house but ran into the woods. I ran after her and found her sitting there in an old chair smoking a cigarette. What could I do? She was nine and smoking a cigarette. If I had asked her to stop, she would have just laughed at me.

I met Amanda’s mother and arranged to come back the following Sunday to spend a day photographing. I always recommend sticking with a subject you like to photograph. You don’t have to be on a magazine assignment to follow your interests and instincts. Following one subject can be an assignment in and of itself.

Amanda got really excited that I was coming. She put on her mother’s makeup, and even got fake fingernails. So I spent the day with the family, mainly Amanda and her cousin, Amy. I was a little disappointed because Amanda was so into being photographed that it was hard to catch an authentic moment. Sometimes, the hardest thing is to get people to stop mugging for the camera. Also, with children, if they are playing too much to you, it’s not real (they’re too involved with you). Treat them like adults. Sometimes I’ll say, “If you smile, I won’t take your picture.”

Toward the end of the day, as I was about to leave, Amanda’s mother said, “Amanda’s back in the kiddy pool if you want to say good-bye.” So I went back to the pool, and there she was smoking a cigarette. I had my Leica with me. I composed the picture quickly with the round pool filling a lot of the frame. Amanda commands the foreground with her attitude and her cigarette. You can see that she’s totally relaxed in front of the camera after a day of shooting. She’s not performing anymore. I shot two frames, maybe three.

I often tell students, “Don’t put away your camera. Keep it out at all times even when you think you have the shot already.” Something can always happen. I had packed up all of my other equipment but luckily I had the Leica on me.

The post Excerpt from Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 28, 2015

Altered Images at the Bronx Documentary Center

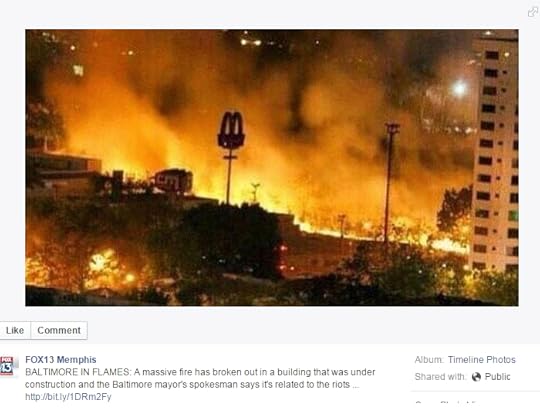

Unknown photographer, Valencia, Venezuela, February, 2014

On April 27, 2015, FOX13 Memphis posted a picture to their Facebook page of what appeared to be Baltimore engulfed in flames. While Baltimore was overrun with riots that night, the photograph was taken in Venezuela a year prior. The photographer remains unknown.

Distributed by the Revolutionary Guard, Iran

July, 2008

Numerous American news outlets published this image of an Iranian missile launch on their front page. The image showed four missiles streaking into the air. It was released by Sepah News, the official online news site of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. Only three of the missiles successfully launched; the fourth was Photoshopped in to hide the missile that failed to launch. Little Green Footballs, an American political blog, discovered the manipulation the day of the photo's publication, calling it a "Photoshop fake." The Associated Press released the original photo the next day with the fourth missile unlaunched in the center; both Sepah News and Agence France-Presse (AFP) rescinded the photograph.

Adnan Hajj, Beirut, Lebanon, August 5, 2006

Adnan Hajj, the photographer, was found to have used Photoshop to clone and darken the smoke in this photo to exaggerate the bombing damage. This photograph was distributed throughout the media before the manipulation was caught by a blogger. Reuters news agency, who worked with the freelance photographer, immediately fired him. Reuters then withdrew all 920 photographs by Hajj from its database after it was discovered that he had manipulated a second photo.

Arthur Rothstein, South Dakota Badlands, 1936

Arthur Rothstein, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, moved and photographed a steer skull at several locations in South Dakota during a severe drought in the region. Several frames of this exist, all showing different backgrounds. After one of the photos was distributed by the Associated Press, Republican opponents of President Roosevelt seized on the opportunity and articles about the staging of this photo were published in conservative newspapers around the country.

Eugene Smith, Deleitosa, Spain, 1951

Eugene Smith's photo essay Spanish Village was published in LIFE magazine in 1951 and was received with national acclaim among both readers and photographers. The iamge series depicts a small rural village in Spain under the rule of dictator Francisco Franco. In this photograph, an intimate scene of the wake of a Deleitosa villager, Smith retouched the wife and daughter's eyes. Originally the two women had been looking toward the photographer, but in the darkroom he printed their eyes much darker and then applied bleach with a fine-tipped brush to create new whites, thereby redirecting their gazes downward and to the side.

Giovanni Troilo, Charleroi, Belgium, 2014

This was part of a winning photo essay in the 2015 World Press Photo awards. The image, of the photographer's cousin and a woman having sex in a car, and lit by the photographer's remote flash inside the car, was set up. WPP judges eventually rescinded the award after numerous other complaints surfaced and an uproar ensued from the photojournalism community; another photo in the series was found to be taken in Brussels, not Charleroi, as the caption claimed. Charleroi's mayor and others complained that other photos from the series were staged.

Yevgeny Khaldei, German Reichstag building, Berlin, May 2, 1945

This iconic photograph from World War II shows a triumphant Red Army soldier waving a Soviet flag over the Reichstag building in Berlin, signifying communist conquest over Nazi Germany. Khaldei scaled the Reichstag with his own Soviet flag in tow, one that had been made by his uncle out of tablecloths for this purpose. He asked the soldiers to pose with the flag. Before the photo's first publication in Ogoniok, a Russian magazine, the watches on the soldiers' wrists were scratched out on the negative, concealing that the Soviets had been looting. Dark clouds of smoke were added in a later version on the photograph.

Brian Walski, Basra, Iraq, March 30, 2003

The photograph is a composite of two images taken seconds apart. After the Hartford Courant published the image, an employee noticed a duplication of civilians in the background. The Los Angeles Times confronted Walski, who confessed to having digitally merged the two photographs to improve the composition.

How—and why—do photojournalists change their photographs? A new exhibition, Altered Images: 150 Years of Posed and Manipulated Documentary Photography, on view at the Bronx Documentary Center through August 2, posits that the history of altered news pictures might provide an alternative history of photojournalism itself. In the 1850s and 1860s, war photographers such as Roger Fenton (in Crimea) and Alexander Gardner (during the Civil War) rearranged cannon balls and bodies to make the image more true to life, since action photography was impossible. By the 1930s, Robert Capa used film and Leicas, which allowed him to capture action but brought different sorts of problems. How did Capa manage to capture a Spanish soldier dying from a bullet wound? The unforgettable picture first appeared on September 23, 1936 in France’s VU, and modern researchers still debate whether Capa was at the place identified in the caption.

Altered Images was born out of such questions, and from director (and award-winning photojournalist) Mark Kamber’s desire to reinforce a code of journalist ethics that he perceives to be at risk, largely because of the economic and technical crises that now threaten news media.

The show includes over one hundred cases of alteration, from the 1850s to the present, each accompanied by informative captions. We see the image as originally published, what the show calls the “Representation,” in the form of front pages of newspapers, pages of magazines, and screen shots. A text describing the “Reality” identifies the alteration and the reason behind it, in numerous cases including quotes from the photographer.

Alteration in photojournalism is not a new story, but it has become simpler to do with the rise of digital journalism, confirmed here by the fact that the majority of examples from this exhibition date from recently. The most recent front-page story dates from January 11, 2015 when world leaders joined a Paris demonstration for the slain journalists of French humor magazine Charlie Hebdo. The Orthodox Israeli paper HaMevaser, altered a photograph of the march taken by Haim Zach, removing German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo, and President of Switzerland Simonetta Sommaruga. Their presence, as women, violated religious beliefs of publisher, editors and readers —a reminder that such censors always believe in the justice of their work.

We are left prompted to ask different kinds of questions: what kind of information remains immune to alteration? What kind of photographic evidence cannot be altered? This exhibition, refreshingly, does not pretend to offer answers.

–Mary Panzer

The post Altered Images at the Bronx Documentary Center appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 27, 2015

Nobuyoshi Araki’s Polaroids

Nobuyoshi Araki’s portfolio of Polaroid collages of nudes juxtaposed with flora is one of the Tokyo-based photographer’s latest projects, which appeared in Aperture magazine #219, Summer 2015, “Tokyo,” with the following editors’ note. Araki’s latest exhibition, Eros Diary, is currently on view at Anton Kern Gallery, New York, through August 7.

All photographs from the series Kekkai, 2014 © Nobuyoshi Araki and Eyesencia, Tokyo

At his retrospective in London a decade ago, Nobuyoshi Araki’s presence was likened to a tornado. Indeed, as photographers go, Araki is something of a storm. His voluminous output now forms a library unto itself: more than five hundred books of his photographs have been published since the 1960s. Over the course of his career, Araki’s sharp and libidinous eye has garnered a global cult following; he has incited controversy for his signature kinbaku (a Japanese form of bondage) images of kimono-draped models bound with rope. A tension between Eros and Thanatos is at the center of his work—the weight shifting to the latter as Araki ages. He is seventy-four and recently lost sight in his right eye, but in his work he shows no sign of slowing down. For Araki, photography and living are mutually dependent. An unfortunate fate becomes an area of creative exploration. His series Love on the Left Eye (2013–14) features photographs half-obscured with marker, and last December he presented the works seen on these pages, a new series of Polaroid collages titled Kekkai (2014), at Tokyo’s Art Space AM. The title invokes the Buddhist concept of a barrier cordoning off a sanctum. Araki splices together nudes and flowers, reanimating two of his long-standing preoccupations. “When you lose something, you gain something else,” Araki recently remarked about his reduced vision. “I say to myself that I believe I should be able to see things differently.”

–The Editors

Click here to find Aperture magazine on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Nobuyoshi Araki’s Polaroids appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 24, 2015

On Press with Aperture Production

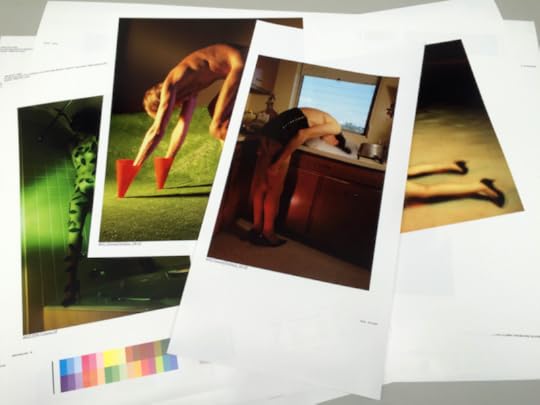

Production coordinator Thomas Bollier walks us through the recent printing of the Aperture book Suburban, a collection of Jimmy DeSana’s earlier photographs, made from the 1970s to early 1980s. The production team makes numerous press trips each year to oversee the printing of Aperture’s books and magazine, traveling to places as diverse as Istanbul; Dongguan, China; and Verona, Italy. The DeSana book was printed at Optimal Media in Röbel, Germany, this July. Suburban will be available this fall.

This article originally appeared in Issue 12 of the Aperture Photography App.

This is the exterior of Optimal’s printing plant and offices. Optimal also produces CDs and vinyl records—it’s one of the few remaining factories still pressing vinyl.

Books are generally printed on sheets of paper about this size, which are later folded down to produce signatures that are bound together. We check and approve the color for the printing on each side of each sheet, matching the color that appears on press with color proofs. For this project, the proofs were made for us by Echelon Color, a Los Angeles-based color separator and repro (reproduction) house we also use for the production of Aperture magazine. Color separators like Echelon convert the RGB files we receive from artists—in this case, drum scans we had made of DeSana’s original 35mm transparencies—to a CMYK color space that can be used for offset printing. They also output color proofs for us using an Epson ink-jet printer that is set up to simulate the color that will be produced when the images are printed in CMYK. This simulation is not exact, but it’s often very close. For most projects, we go through several rounds of proofing, adjusting color and contrast, and spotting and retouching when necessary. We also review the proofs with the artists when possible so they know what to expect, often comparing proofs to the artist’s original print.

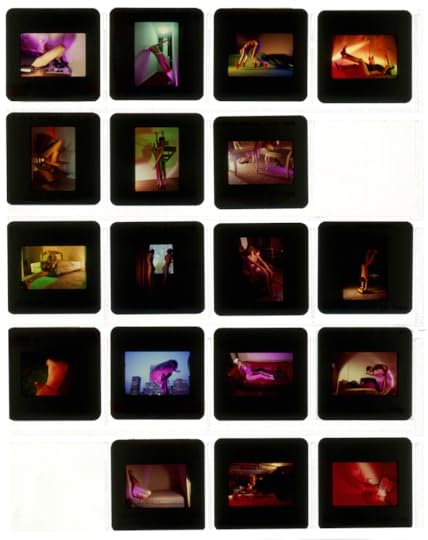

Original Jimmy DeSana 35mm transparencies—the source material for the images reproduced in Suburban.

Unfolded printed sheets are left to dry after printing. With this book, the sheets went through the press a second time to apply a layer of varnish to the images. Sometimes, varnish is applied “in-line,” or in the same pass as all the other inks. In this case, we printed the varnish “off-line,” or in a separate pass. This way, the ink is let to dry before the varnish is laid on top, allowing a heavier, more glossy layer of varnish to be printed.

Here we adjust the color on the book’s cover image. The adjacent sheets laid side-by-side show incremental adjustments in the density of certain inks, with the goal of matching the color of the proof, visible in the middle. The cover will later be laminated, before being bound with the book, to add a layer of protection and a gloss finish.

A Heidelberg Speedmaster ten-color press.

The northern German landscape, as viewed from the printing plant.

Tap here to follow the Aperture Production team on Instagram.

The post On Press with Aperture Production appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers