Aperture's Blog, page 158

June 12, 2015

Inside Aperture’s Spring Patron Cocktail Event

On Monday, June 8, nearly fifty Aperture Patrons, board members, and photographers gathered for the second annual Spring Patron Cocktail Party. The evening included presentations by photographers Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao and Scout Tufankjian. Liao spoke about the complicated process that goes into making each of his photographs, as they are assembled by section, overlaying up to forty shots to create a distinctive landscape image. Tufankjian discussed her photojournalism work. Through anecdotes from the 2008 campaign trail—where she was the only photographer to follow the entire Obama campaign—to her most recent project documenting Armenian communities around the world, she gave the audience a taste of what goes into her profoundly human pictures. Following the presentations, guests mingled with each other as well as the featured photographers. Signed copies of Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York (Aperture, 2014) were also available.

We look forward to future Aperture Patron events and thank all of our Members, trustees, and photographers for their involvement and support.

To learn more about Aperture’s Patron Program, click here or contact Emily Grillo at egrillo[at]aperture.org or 212.946.7103.

Images © Max Mikulecky.

The post Inside Aperture’s Spring Patron Cocktail Event appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 11, 2015

Rick Sands: Breaking The Light Barrier

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled from Beneath the Roses, 2004

“I always call him ‘the genius of light’. He puts all of the lighting scenes together. He thinks differently than everyone else I know. He just responds to light. It’s remarkable.”

—Gregory Crewdson on Rick Sands

Join master illuminator Rick Sands for “Breaking the Light Barrier,” a workshop for photographers who would like to improve their understanding of lighting—from conceptualization through execution. For nearly fifteen years, Sands has created elaborate lighting for the narrative photographs of artist Gregory Crewdson. The class will cover varied philosophies of lighting technique, working under a wide range of conditions (day as well as night, interior as well as exterior), and studying separation through use of contrast via intensity and color. The class will also cover practical aspects like scheduling and budgetary concerns.

Over the course of six days, “Breaking the Light Barrier” will cover contextual light, interior lighting, exterior lighting, and project flow as separate units of study. Each unit will be comprised of conceptual overview, study of examples, equipment demonstration, training exercises, and experimentation. Students will be asked to complete four assignments, the last being a comprehensive production exercise taking place over three days. Additional concepts reviewed will include the motivation of light, the study of ambient light, light plots, the importance of time-of-day, and the set environment and its effect on lighting.

Participants will then form teams to produce projects employing the techniques covered by the curriculum. The main objective of the class is to create and extend a lighting vernacular that allows you to design and execute diverse projects. Participants will gain comfort and confidence, enabling them to work adeptly throughout the lighting design process.

Rick Sands is a film technician whose roots are in cinema production. His portfolio includes thirty-five theatrically released motion pictures with directors such as Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola, forty-seven television movies, and countless one-hour television episodes. His work in advertising has won him several ADDY awards. Through his unique collaboration with Gregory Crewdson, Sands’s lighting has been featured in six books and several international exhibitions.

Tuition: $950 ($875 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Register here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Rick Sands: Breaking The Light Barrier appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

On Philip Gefter’s Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe

Philip Gefter’s new biography of Sam Wagstaff examines the life of the influential curator and collector, and his romantic relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe. Gefter argues that there is a relationship between the queer gaze and a particularly influential period for the history of photography, as told through Wagstaff’s story. Here we feature writer Kira Josefsson’s review of Gefter’s book.

In 1970s New York, when homosexuality was still punishable by law, it was an especially risky act for a man to let his eyes linger on another man in public. But photographs enjoyed privately could be a safe space for the queer gaze. As author and critic Philip Gefter argues in his biography Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe, it was not an accident that so many photography collectors active during this period were gay men. The book charts the life of Sam Wagstaff, best-known as the lover and patron of Robert Mapplethorpe, and sets out to show that his importance extends beyond that relationship—that he was a critical force in photography’s elevation to an art form, on par with MoMA curator John Szarkowski in influence.

Born into the repressive, patrician circles of the 1920s Upper East Side, Wagstaff always had a keen eye. But it was not until he went back to school for art history at age thirty-six that he was able to fully explore his interest in the visual. From 1961 to 1971, Wagstaff worked as a curator, first at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut, then at the Detroit Institute of Arts. During this time, he immersed himself in contemporary art, spending most of his free time with young artists in Hartford, Detroit, and New York, championing those—often men—whose ideas, talent, and, frequently, looks attracted him. In this way, Gefter argues, Wagstaff came to be at the forefront of new ideas; he was responsible for the first exhibition of minimalist art at a major museum, with Black, White, and Gray at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1964.

Wagstaff’s love for photography coincided directly with his love for Mapplethorpe. Mapplethorpe had already begun his move from collage to photography when the two men—born the same day, twenty-five years apart—began their relationship in 1972. Wagstaff had a ferocious belief in Mapplethorpe’s talent. He supported him financially by buying him a loft in New York and pushed his career in myriad other ways. Their deep bond, forged as much by intellectual and artistic exchange as by attraction, was often complicated, and they each took other long-term lovers; but their symbiosis would last until Wagstaff died of AIDS in 1987. (Mapplethorpe was taken two years later.)

In 1973, the two went to see the exhibition The Painterly Photograph at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Wagstaff had a revelation in front of Steichen’s The Flatiron (1904) which led him to shed his skepticism about the medium. He turned to photography with the enthusiasm of a religious convert, trawling auctions, flea markets, and estate sales all over Europe and the U.S. He soon had a vast, idiosyncratic collection, encompassing everything from work by Nadar to cat pictures, and he showed it to everyone who would listen, rhapsodizing over light and composition, pointing out parallels to classical painting. These photographs ended up in shows, were edited into a book by Wagstaff, and, eventually, joined the Getty Museum collection.

Gefter argues that Mapplethorpe benefited by learning about the largely uncharted aesthetic history of photography as Wagstaff drew its outlines for himself—and the medium benefited, as well. The fact that a person with Wagstaff’s by-then considerable weight in the art world took such an interest in photography, not widely accepted as a fine art, helped spark the attention of others. No doubt the large sums Wagstaff and his fellow enthusiasts spent on their collections helped, too.

A curator engaged in art investment can fall into conflicts of interest; the profit motive risks muddling curatorial judgment. Wagstaff was certainly not in it for the money, but this slippery slope was nevertheless sometimes manifest in his actions. Gefter, clearly enthused by his subject, tends to breeze past such inequities. His conjectures about the link between Wagstaff’s homosexuality and his habit of collecting can also come across as slightly tenuous. Such missteps aside, the biography draws from a treasure trove of materials and paints a rich, detailed portrait, including two short inserts with images of the (human, as well as inanimate) objects of Wagstaff’s affection. Wagstaff is a loving and inquisitive cultural history of the New York art world in the twentieth century.

The PhotoBook Review is Aperture’s biannual tabloid-sized newspaper dedicated to photobooks, with reviews, opinion pieces, artist selections, and publisher profiles. Pick up a free copy at the Aperture Gallery and Bookstore or subscribe to Aperture magazine and get PBR delivered to your door.

The post On Philip Gefter’s Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 9, 2015

Magazine Work

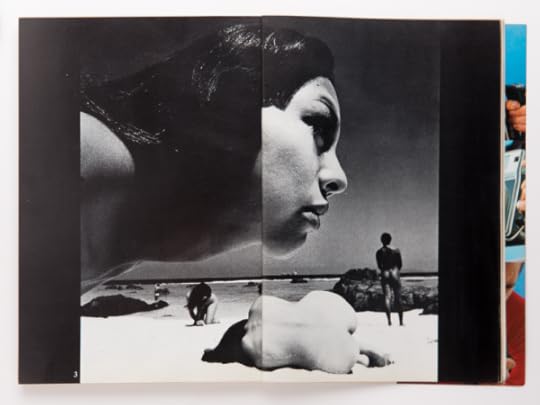

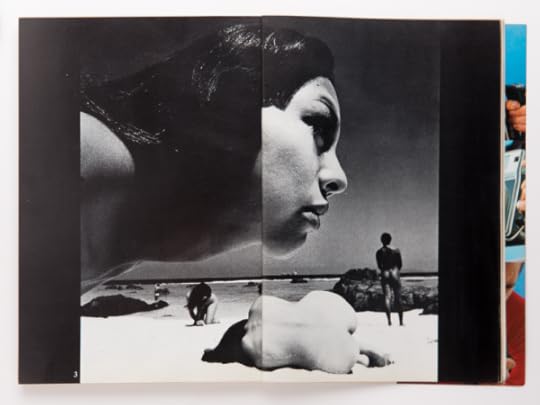

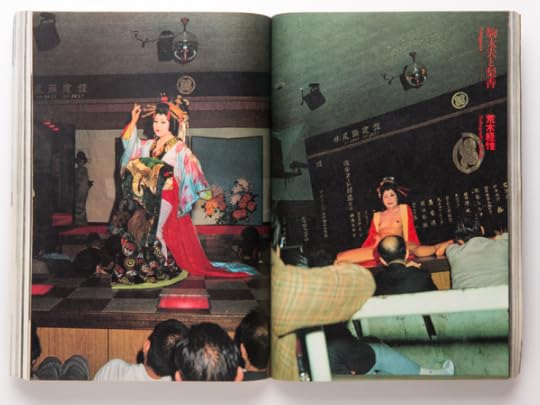

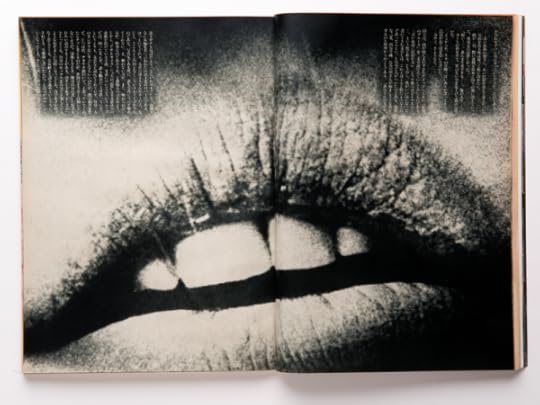

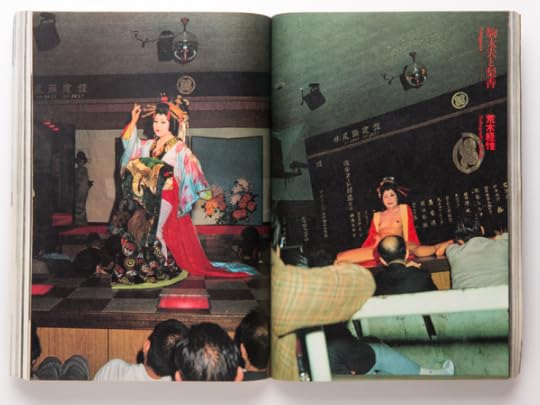

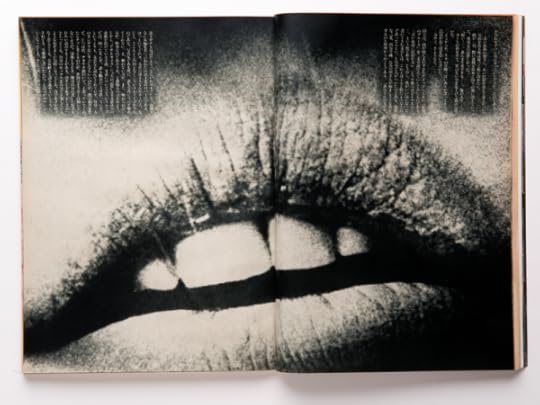

Camera Mainichi, November 1968, photograph by Kishin Shinoyama

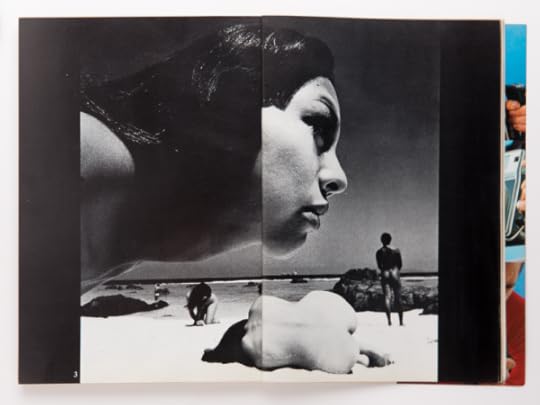

Camera Mainichi, December 1967, photograph by Haruo Tomiyama

Asahi Camera, October 1969, photograph by Kishin Shinoyama

Asahi Camera, June 1969, photograph by Daido Moriyama

Asahi Camera, January 1976, photograph by Masahisa Fukase

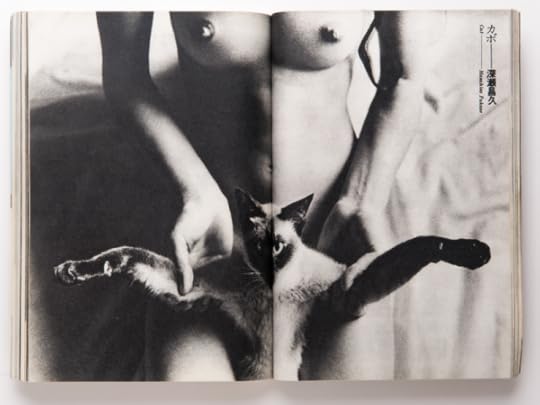

Asahi Camera, January 1976, photographs Nobuyoshi Araki

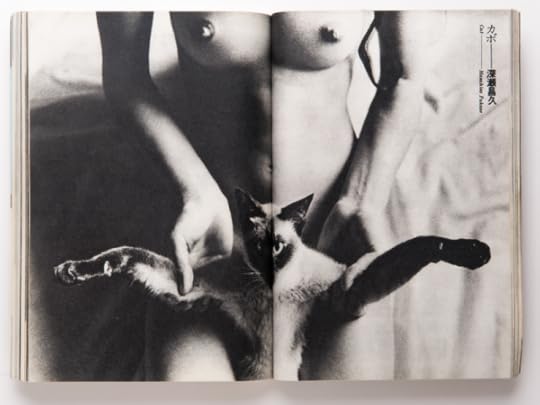

Shashin Jidai, March 1983, photograph by Daido Moriyama

Shashin Jidai, September 1982, photograph by Keizo Kitajima.

Shashin Jidai, November 1981, photographs by Nobuyoshi Araki

Camera Mainichi, April 1965, photograph by Yoshihiro Tatsuki

By Ivan Vartanian

Is the history of Japanese photography also a history of magazine publishing? In the new issue of Aperture magazine, Tokyo-based curator Ivan Vartanian offers a look through the pages of the popular technical and erotically minded magazines of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, revealing some the most significant photography produced during those decades. He writes, “In 1950, in the midst of Japan’s postwar economic recovery, the Ricohflex III premiered on the market. The world’s first mass-produced twin-lens reflex camera was met with phenomenal sales and catalyzed what would become a prolonged boom market for cameras. Magazines like Asahi Camera (1949–present) and Camera Mainichi (1954–85) emerged to educate this new demographic of photo-enthusiasts. While the bulk of content consisted of articles on technique, equipment reviews, and pictures submitted by amateur snappers, these magazines also published some of the most important photography of postwar Japan. Editorial stories by Shomei Tomatsu, Kishin Shinoyama, Daido Moriyama, Yutaka Takanashi, and Issei Suda may not have driven sales, but these photographers effectively challenged established ideas about the nature of the medium. Through their work, they argued that photography had the power to provoke thought and possibly exceed written language in its capacity to communicate.” Here we feature a selection of images from Asahi Camera , Camera Mainichi, and Shashin Jidai (1981-87), which is also discussed in the article. This article also appears in Issue 9 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

The post Magazine Work appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

On Japanese Photography Magazines

Camera Mainichi, November 1968, photograph by Kishin Shinoyama

Camera Mainichi, December 1967, photograph by Haruo Tomiyama

Asahi Camera, October 1969, photograph by Kishin Shinoyama

Asahi Camera, June 1969, photograph by Daido Moriyama

Asahi Camera, January 1976, photograph by Masahisa Fukase

Asahi Camera, January 1976, photographs Nobuyoshi Araki

Shashin Jidai, March 1983, photograph by Daido Moriyama

Shashin Jidai, September 1982, photograph by Keizo Kitajima.

Shashin Jidai, November 1981, photographs by Nobuyoshi Araki

Camera Mainichi, April 1965, photograph by Yoshihiro Tatsuki

By Ivan Vartanian

Is the history of Japanese photography also a history of magazine publishing? In the new issue of Aperture magazine, Tokyo-based curator Ivan Vartanian offers a look through the pages of the popular technical and erotically minded magazines of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, revealing some the most significant photography produced during those decades. He writes, “In 1950, in the midst of Japan’s postwar economic recovery, the Ricohflex III premiered on the market. The world’s first mass-produced twin-lens reflex camera was met with phenomenal sales and catalyzed what would become a prolonged boom market for cameras. Magazines like Asahi Camera (1949–present) and Camera Mainichi (1954–85) emerged to educate this new demographic of photo-enthusiasts. While the bulk of content consisted of articles on technique, equipment reviews, and pictures submitted by amateur snappers, these magazines also published some of the most important photography of postwar Japan. Editorial stories by Shomei Tomatsu, Kishin Shinoyama, Daido Moriyama, Yutaka Takanashi, and Issei Suda may not have driven sales, but these photographers effectively challenged established ideas about the nature of the medium. Through their work, they argued that photography had the power to provoke thought and possibly exceed written language in its capacity to communicate.” Here we feature a selection of images from Asahi Camera , Camera Mainichi, and Shashin Jidai (1981-87), which is also discussed in the article. This article also appears in Issue 9 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

The post On Japanese Photography Magazines appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 8, 2015

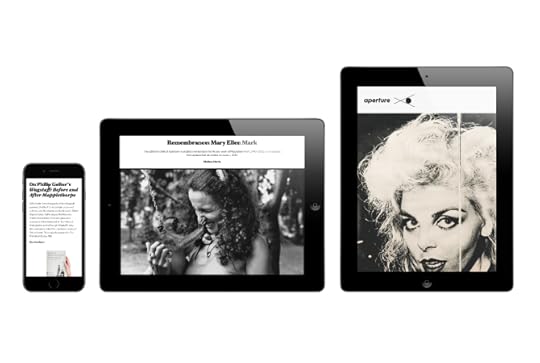

Issue 9 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 9:

● Tokyo-based-curator Ivan Vartanian offers a look inside Japanese photography magazines from the 60s, 70s, and 80s

● Mary Ellen Mark’s life and work is remembered by her collaborators, colleagues, and friends

● A report from the newly opened Shanghai Center of Photography

● From The PhotoBook Review 008, Kira Josefsson on Philip Gefter’s Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe

● A look at the redesigned and expanded version of Berenice Abbott: Aperture Masters of Photography

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 9 of the Aperture Photography App Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 5, 2015

Review: On Max Pinckers’s Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

Max Pinckers

Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

Self-published, 2014

Designed by Jurgen Maelfeyt

8 1/4 x 11 1/2 in. (21 x 29 cm)

232 pages

140 color images

Paperback with flaps

maxpinckers.be

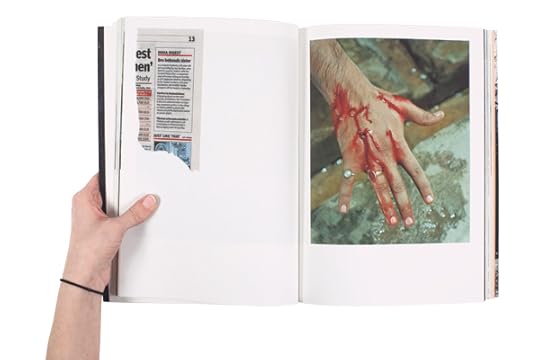

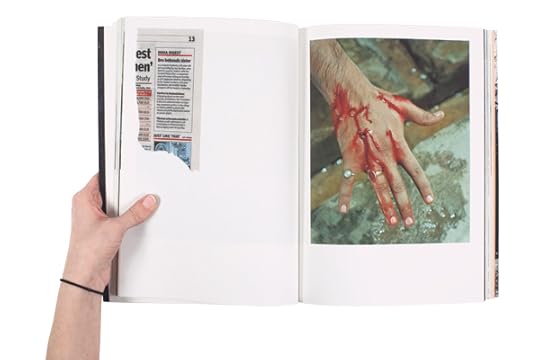

“Cops joined kin’s hunt for lovers,” declares the ragged-edged headline of a newspaper article slapped into Max Pinckers’s lush, layered Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty. Providing context for the images that come before and after, the article serves as an entry point into Pinckers’s beautiful, poetic, and occasionally simplistic exploration of love as experienced by the Indian subcontinent.

To open the book is to fall into the middle of a mystery. Comprised of documentary-style photographs, staged compositions, reprinted e-mails, newspaper clippings, and digitized photo backdrops (where fall foliage and spring tulips form a literally impossible landscape), it pivots between the fantastic, the lurid, and the disarmingly real. In one recurring series, a powder-blue room holds couple after couple within its walls, their cuddling and smiles a poignant counterpoint to their confinement. They are, in fact, fugitives; press clippings on that same blue wall and reprints of desperate e-mails lead to the understanding that these couples’ lives are in the hands of the Love Commandos, an NGO dedicated to assisting couples whose families—for reasons of caste, religion, or economic status—forbid their marriage. Just how far certain families will go to forbid a union is made clear with more clippings: “Bro beheads sister,” for example, and “For honour, man kills pregnant daughter.”

Max Pinckers, Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

This is a deftly layered book, each page a “clue” propelling the viewer past marriage podiums and portraits, past the unique synthesis of myth, history, and Bollywood spectacle that comprise modern India’s relationship to love. Pinckers’s best works read as beautiful hybrids, the spontaneity of documentary combined with the painterly sense of color and composition found in staged shots. He excels at catching emotion between lovers, whether they stand apart on a rocky shore or hide their connected heads under a saffron chunni. In one particularly heartbreaking set, a young couple lies shoulder-to-shoulder and fully clothed on a safe-house bed, moving from serious conversation to smiles, to laughter. The affection between them is so palpable that one can’t help but feel frustrated by anything that would keep them apart.

But here the book reaches too easily for an answer, and finds itself in familiar Western territory, with its predictable assessment of arranged marriage. Presented as a malevolent specter—the dark force of familial will waiting to put an end to true love—the photographer’s view toward the tradition comes through in both composition and juxtaposition: a photograph of a bloody hand on the same spread as the clipping that reads “Bro beheads sister”; an older man with one hand on a young woman’s neck, preceding “For honour, man kills pregnant daughter.” Marriage portraits with the faces cut out further emphasize that any sense of identity vanishes within these unions.

Hans Theys’s essay in the book identifies Pinckers as having been born in Belgium but raised in Asia, and asserts that, “the beauty of [his] approach is that he takes no stance. He doesn’t make a statement, he tries to show us things.” It’s an assessment that overlooks the fact that fictionalizing—that is, choosing the details of a story—is inherently a stance. Placing a photograph of a burning kameez across from a clipping of divorce announcements is a statement, as is having the argument for arranged marriage exemplified by reports of violence and a singular, poorly spelled e-mail. The country’s more complex tension between arranged marriage and romantic love—and the prevalent Indian view that the first can easily lead to the second—is vastly ignored here, in favor of a centuries-old storyline that paints the West as custodians of identity and passion, the East as fear-bound followers. In this, one can’t help regret the blindness of an eye keen on seeing so much. But while the misstep detracts from what might be a more nuanced reflection, it does not rob these pages of their dense, intriguing, visual glory.

_____

Mira Jacob is the author of the critically acclaimed novel The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing (Random House, 2014), which was short-listed for the Tata Literature Live! First Book Award; honored by the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association; and named one of the best books of 2014 by Kirkus Reviews, the Boston Globe, Goodreads, Bustle, and the Millions. She teaches fiction writing at New York University.

mirajacob.com

The post Review: On Max Pinckers’s Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Review: Mira Jacob on Max Pinckers’s Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

Max Pinckers

Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

Self-published, 2014

Designed by Jurgen Maelfeyt

8 1/4 x 11 1/2 in. (21 x 29 cm)

232 pages

140 color images

Paperback with flaps

maxpinckers.be

“Cops joined kin’s hunt for lovers,” declares the ragged-edged headline of a newspaper article slapped into Max Pinckers’s lush, layered Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty. Providing context for the images that come before and after, the article serves as an entry point into Pinckers’s beautiful, poetic, and occasionally simplistic exploration of love as experienced by the Indian subcontinent.

To open the book is to fall into the middle of a mystery. Comprised of documentary-style photographs, staged compositions, reprinted e-mails, newspaper clippings, and digitized photo backdrops (where fall foliage and spring tulips form a literally impossible landscape), it pivots between the fantastic, the lurid, and the disarmingly real. In one recurring series, a powder-blue room holds couple after couple within its walls, their cuddling and smiles a poignant counterpoint to their confinement. They are, in fact, fugitives; press clippings on that same blue wall and reprints of desperate e-mails lead to the understanding that these couples’ lives are in the hands of the Love Commandos, an NGO dedicated to assisting couples whose families—for reasons of caste, religion, or economic status—forbid their marriage. Just how far certain families will go to forbid a union is made clear with more clippings: “Bro beheads sister,” for example, and “For honour, man kills pregnant daughter.”

Max Pinckers, Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty

This is a deftly layered book, each page a “clue” propelling the viewer past marriage podiums and portraits, past the unique synthesis of myth, history, and Bollywood spectacle that comprise modern India’s relationship to love. Pinckers’s best works read as beautiful hybrids, the spontaneity of documentary combined with the painterly sense of color and composition found in staged shots. He excels at catching emotion between lovers, whether they stand apart on a rocky shore or hide their connected heads under a saffron chunni. In one particularly heartbreaking set, a young couple lies shoulder-to-shoulder and fully clothed on a safe-house bed, moving from serious conversation to smiles, to laughter. The affection between them is so palpable that one can’t help but feel frustrated by anything that would keep them apart.

But here the book reaches too easily for an answer, and finds itself in familiar Western territory, with its predictable assessment of arranged marriage. Presented as a malevolent specter—the dark force of familial will waiting to put an end to true love—the photographer’s view toward the tradition comes through in both composition and juxtaposition: a photograph of a bloody hand on the same spread as the clipping that reads “Bro beheads sister”; an older man with one hand on a young woman’s neck, preceding “For honour, man kills pregnant daughter.” Marriage portraits with the faces cut out further emphasize that any sense of identity vanishes within these unions.

Hans Theys’s essay in the book identifies Pinckers as having been born in Belgium but raised in Asia, and asserts that, “the beauty of [his] approach is that he takes no stance. He doesn’t make a statement, he tries to show us things.” It’s an assessment that overlooks the fact that fictionalizing—that is, choosing the details of a story—is inherently a stance. Placing a photograph of a burning kameez across from a clipping of divorce announcements is a statement, as is having the argument for arranged marriage exemplified by reports of violence and a singular, poorly spelled e-mail. The country’s more complex tension between arranged marriage and romantic love—and the prevalent Indian view that the first can easily lead to the second—is vastly ignored here, in favor of a centuries-old storyline that paints the West as custodians of identity and passion, the East as fear-bound followers. In this, one can’t help regret the blindness of an eye keen on seeing so much. But while the misstep detracts from what might be a more nuanced reflection, it does not rob these pages of their dense, intriguing, visual glory.

_____

Mira Jacob is the author of the critically acclaimed novel The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing (Random House, 2014), which was short-listed for the Tata Literature Live! First Book Award; honored by the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association; and named one of the best books of 2014 by Kirkus Reviews, the Boston Globe, Goodreads, Bustle, and the Millions. She teaches fiction writing at New York University.

mirajacob.com

The post Review: Mira Jacob on Max Pinckers’s Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 3, 2015

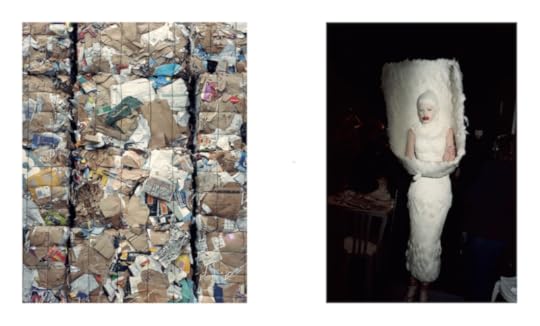

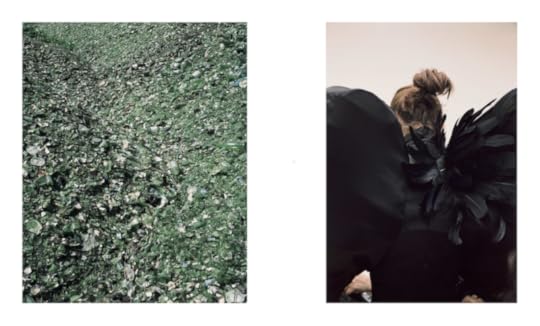

On Nick Waplington/Alexander McQueen: Working Process at Tate Britain

Tate Britain’s first-ever exhibition to focus on a living photographer features the work of Nick Waplington, who documented the late designer Alexander McQueen as he created his Autumn/Winter 2009/10 collection, which would be his last before his death in 2010. Since the 1980s, Waplington has worked in a wide variety of photographic mediums on diverse subjects, and has been particularly notable for his treatment of the photobook as an art form, and McQueen specifically commissioned him to create one about his process. Fashion, however, has hardly ever featured into Waplington’s work that is usually documentary in nature, such as in the projects Living Room (Aperture, 1991); Weddings, Parties, Anything (Aperture, 1996); and Other Edens (Aperture, 1994). Here, Alistair O’Neill, a senior research fellow at Central Saint Martins in London, examines how the unlikely pairing of a fashion designer and photographer unfolds across Tate Britain’s galleries. The show runs in tandem with the V&A Museum’s presentation of McQueen’s designs in the exhibition Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. This article also appears in Issue 8 of the Aperture Photography App, a new biweekly publication from Aperture: click here to download the free app.

In line with the Victoria and Albert Museum’s staging of Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty in London, is a revealing exhibition at Tate Britain displaying a body of work by British photographer Nick Waplington, commissioned by British fashion designer Alexander McQueen to document the process of building his Autumn/Winter 2009/10 collection, Horn of Plenty. If Savage Beauty makes use of McQueen’s extraordinary showpieces and sense of spectacle for exhibits and scenography, then Waplington’s exhibition Working Process relies on an examination of the processes that lie behind the craftsmanship and staging inherent to McQueen’s work, conveyed through documentary photographs.

When commissioning Waplington, McQueen asked, “Can you make me something dirty and messy like your photobooks?” To which the photographer replied, “. . . This is fashion. I don’t think it’s very dirty and messy, but we can try.” What is captured is neither dirty nor messy in literal terms, but is rather a visceral and textured rendering of fashion being made. From this tight focus (a collection rather than a career; photographs on display instead of fashion) springs a richly articulated and detailed account of the designer at work.

This is informed and inscribed by the words of fashion journalist Susannah Frankel, who worked closely with McQueen (and features in a number of the photographs), and Waplington himself. Her words adorn the walls of the exhibition and are also available as audio on a free mobile resource via Tate WiFi, bringing us closer to the creativity the photographs document, and investing journalist and photographer as both witness and guide.

Horn of Plenty was inspired by the visual sign for cornucopia, but in McQueen’s hands the symbol was reworked to point to the excesses and spoils of late capitalism, assuming a cynical starting point as he returned to his archive and reassessed his career. For the fashion show, McQueen’s team made a black bonfire of all the props he had used in his fashion shows to date, as if a pyre for a black mass to sustainability. Waplington contributed to the theme by offering photographs taken in an East End landfill site to sit among those taken in McQueen’s Clerkenwell studio. In the exhibition, these juxtapositions relate bound bales of recycled paper to the gridded baste stitches that underpin embellished fabrics. Waplington also compares a mound of ground-up glass with the shimmering effect of hand-sewn sequins, linking the transformation of everyday materials with the glimmer of fashion’s visual effects. Frankel’s commentary reminds us that these are not themes born out of interpretation, but ones woven through the collection from the outset: “There was an irony to the recycling element of the collection. The clothes that are supposed to look like they are made of bin bags are actually made from the finest, most expensive silks.”

All photographs, Untitled, by Nick Waplington, from the series Alexander McQueen: Working Process, 2008–09 © Nick Waplington

Such transformations are also delineated by the use of photographic images in McQueen’s studio as part of the fashion-design process. An outfit in toile is photographed back, front, and side, then printed and tacked to a board before its skirt is redrawn with two lines of marker pen: from A-line to tulip shape. Mood boards force the mid-century Dior woman into company with the racetrack attendees of My Fair Lady and a ragbag of Felliniesque clowns and vamps. Through McQueen’s working process in cloth, they reappear, altered, as an army of models that shift and shape, look by look, until they document the fashion show’s outfits and runway order. There is a strong dexterity in using images: they slice and reassemble in the McQueen studio like scissors into cloth. Working Process offers a remarkably intimate portrait of the designer at work and a fitting portrayal of fashion design as craftsmanship.

Working Process ran at Tate Britain from March 10 to May 17.

The post On Nick Waplington/Alexander McQueen: Working Process at Tate Britain appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 1, 2015

Remembering Mary Ellen Mark, 1940–2015

Mary Ellen Mark , Bali, 1973 (photo by Jack Garofalo)

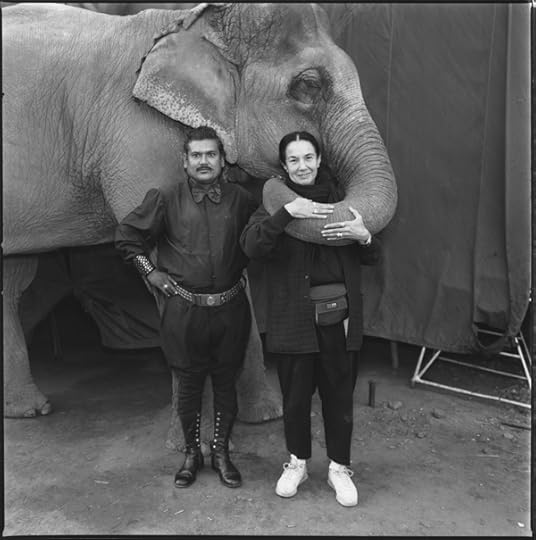

Mary Ellen Mark and Raja, Great Gemini Circus, Perintalmanna, India, 1989 (photo by David Liittschwager)

Mary Ellen Mark with Ram Prakash Singh and his elephant, Shyama, Great Golden Circus, Ahmedabad, India, 1990 (photo by Farrokh Chothia)

Mary Ellen Mark, Oaxaca, Mexico 2013 (photo by Cristina Llerena Navarro)

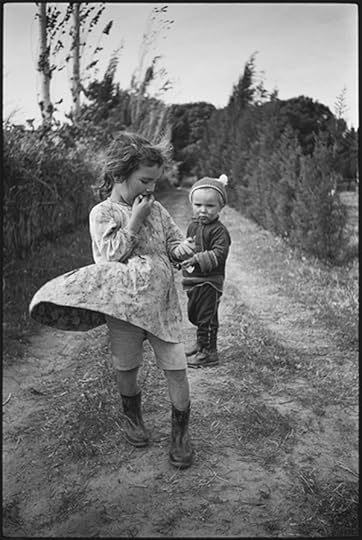

Two Children, Izmir, Turkey, 1965

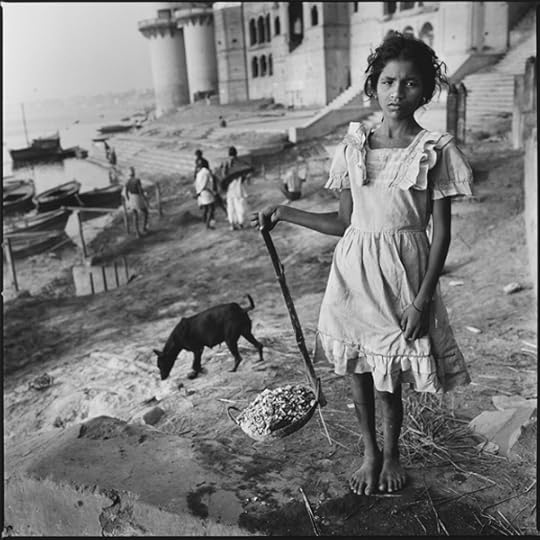

Girl Sifting through Ashes at the Burning Ghats, Benares, India, 1989

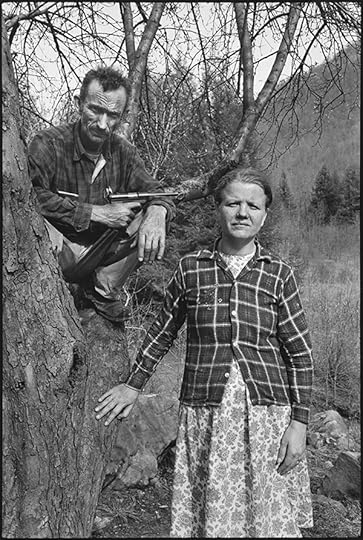

Husband and Wife, Harlan County, Kentucky, 1971

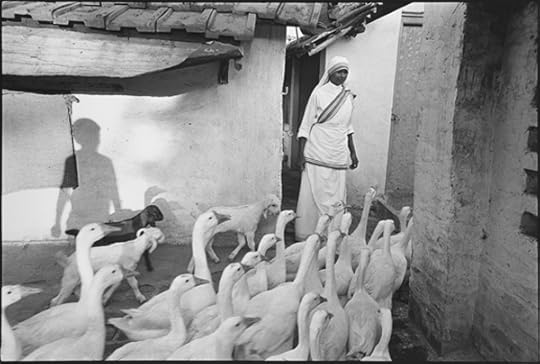

Shadow on a Wall, Shanti Nagar Leprosy Hospital, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, Bengal, India, 1981

Mother Teresa Feeding a Man at the Home for the Dying, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, Calcutta, India, 1980

Three Acrobats, Vazquez Brothers Circus, Mexico City, 1997

Pinky and Shiva Ji, Great Royal Circus, Junagadh, India, 1992

Performing Dogs, National Circus of Vietnam, Lenin Park, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1994

Laurie in the Bathtub, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, 1976

Amanda and Her Cousin Amy, Valdese, North Carolina, 1990

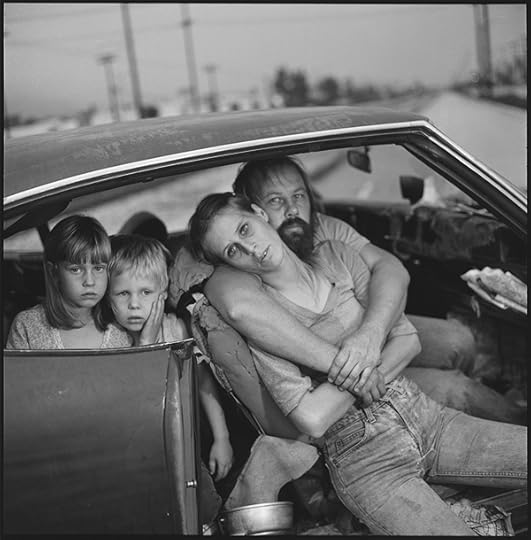

The Damm Family in Their Car, Los Angeles, 1987

Crissy, Dean, and Linda Damm, Llano, California, 1994

Twelve-Year-Old Lata Lying in Bed, Falkland Road, Bombay, India, 1978

Kamla Behind Curtains with a Customer, Falkland Road, Bombay, India, 1978

Gibbs Senior High School Prom, St. Petersburg, Florida, 1986

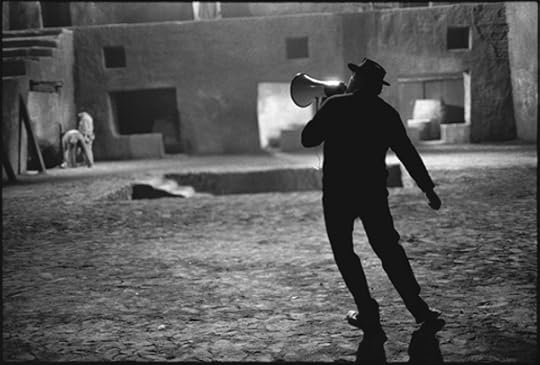

François Truffaut Directing Catherine Deneuve on the Set of Mississippi Mermaid, Grenoble, France, 1969

Federico Fellini on the Set of Satyricon, Rome, 1969

The Cast of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest Posing, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon, 1974

Dennis Hopper on the Set of Apocalypse Now, Pagsanjan, Philippines, 1976

Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Los Angeles, 1978

Tim Burton and a Trained Squirrel on the Set of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, London, 2004

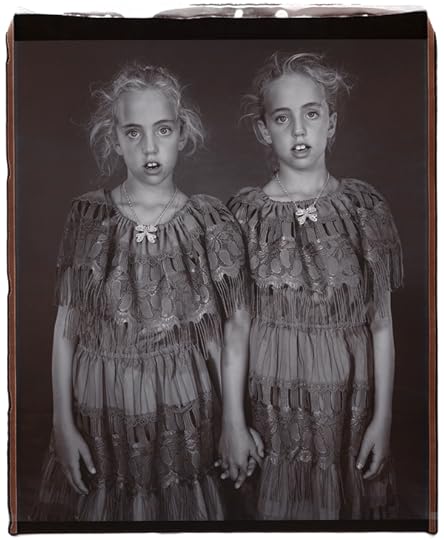

Heather and Kelsey Dietrick, Twinsburg, Ohio, 2002

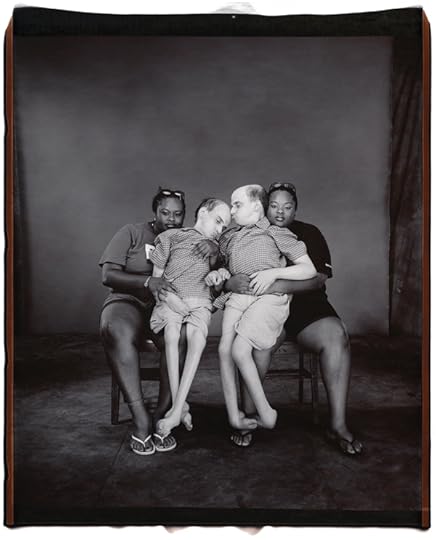

Teresa Merriweather, Bruce and Brian Kuzak, Tillie Merriweather, Twinsburg, Ohio, 2001

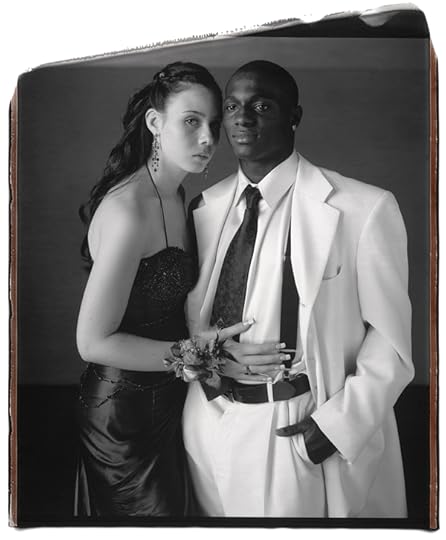

Samantha Monte and Khalil Samad, Staten Island, New York, 2006

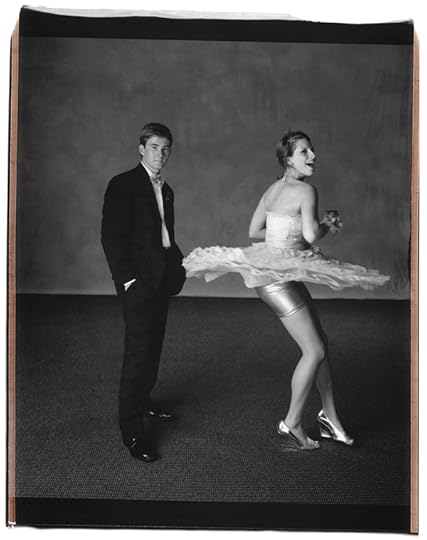

Adam Johnson and Carley Gunter, Austin, Texas, 2008

Tiny in Her Halloween Costume, Seattle, 1983

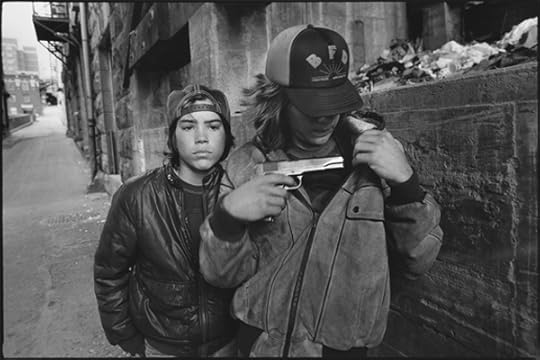

Rat and Mike with a Gun, Seattle, 1983

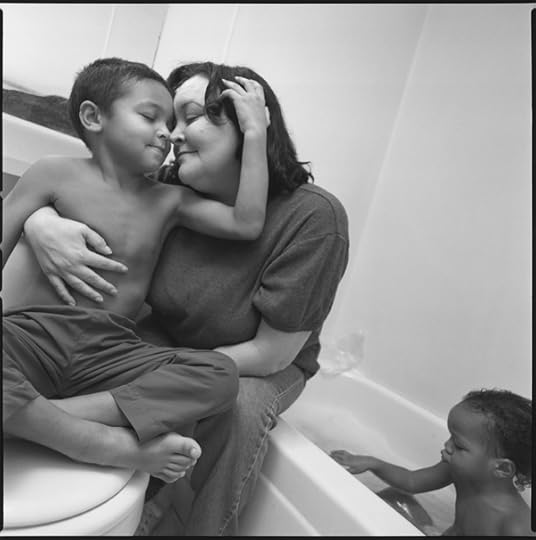

Tiny in the Bathroom with Rayshon and E’Mari, Seattle, 2003

Tiny and J’Lisa on the couch, Seattle, 2014

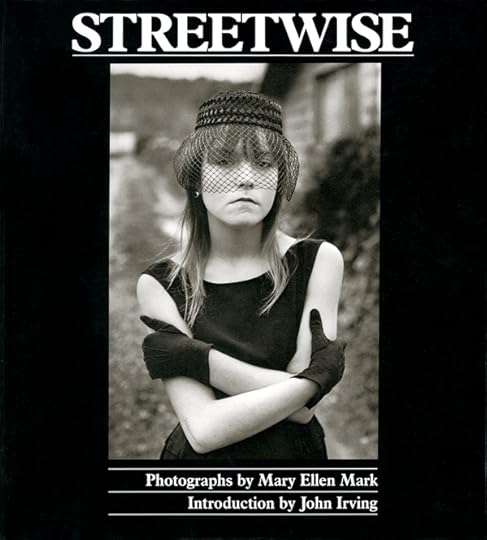

Streetwise, published by Aperture in 1992

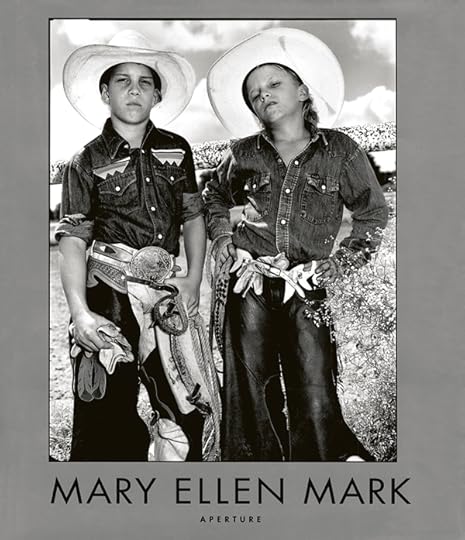

American Odyssey, published by Aperture in 1999

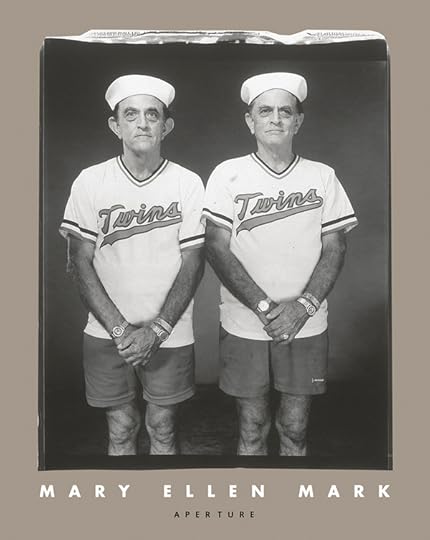

Twins, published by Aperture in 2003

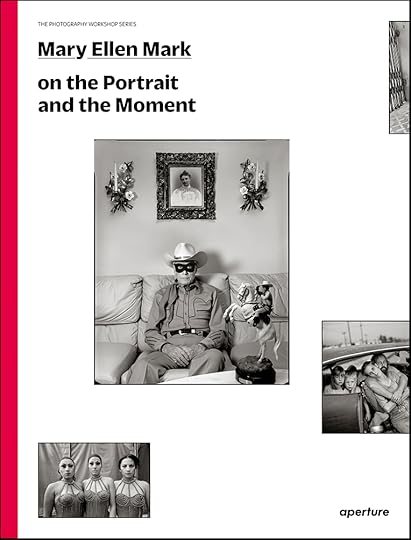

Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment, forthcoming in the Photography Workshop Series by Aperture in June 2015. Mary Ellen Mark died on May 25, 2015. She had completed all the work on this book in the weeks before, and it had just printed at the time of her death.

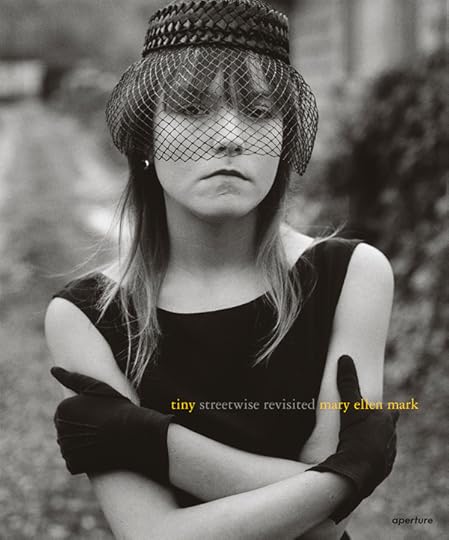

Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, forthcoming by Aperture in September 2015. Mary Ellen Mark died on May 25, 2015. She had completed all the work on this book in the weeks before, and it had just printed at the time of her death.

Mary Ellen (holding Keanna), Martin, and Tiny, 1990

“I was thinking about how fleeting and how precious life is and the choices that you make in life, the luck of being born in the right bed, to parents who support and help you, and who love you. That doesn’t always happen—and then, what happens when that doesn’t happen?” —Mary Ellen Mark, from the afterword to Tiny: Streetwise Revisited

It was early this past winter, and Mary Ellen and I were discussing the afterword she would write—based on interviews I was doing with her—for her forthcoming book, Tiny: Streetwise Revisited. How she would encapsulate her thirty-plus years photographing Tiny, whom she had first met and photographed when Tiny was thirteen, and living with a group of homeless teens on Pike Street, in Seattle? Mary Ellen was sick, but refused to be a slave to her illness. Willfully, determinedly, and at times ironically, she confronted it, without compromise—and with the strong, candid, loving, and intelligent support of her husband and partner, the filmmaker Martin Bell.

Our meetings were squeezed in between the Oaxaca workshops she taught, photographing in Seattle for the final chapter of Tiny: Streetwise Revisited while Martin filmed, teaching in California, accepting awards, and working on another book with my Aperture colleague Denise Wolff.

“There was a time when the sight of Mary Ellen Mark’s number on my phone could raise my blood pressure,” says Wolff. “Whether it was a photographer she wanted me to meet or the time she called to say she wanted good-looking caterers at her fundraising cocktail event—who wouldn’t?!—or something more important, she was relentless when she wanted something.”

Wolff had always heard that Mary Ellen was a wonderful teacher and when Aperture created The Photography Workshop Series, she knew that she wanted to publish a book of her teaching. Mark said yes, but insisted that Wolff travel to her ten-day workshop in Oaxaca, Mexico, to work on the book and meet her students. Aperture’s director, Chris Boot, asked Wolff to persuade Mark that she could gather enough material here in New York or that we could hire an editor we all knew from Mexico to go instead. “Of course, that didn’t work,” says Wolff. “She wanted to do the book, and I had to come to Oaxaca. That was that. Even after I bought the flight, I don’t think she believed I was really coming until I arrived. She had her driver, Tomas, waiting to pick me up at the airport. He had been driving for her in Oaxaca as long as she had been teaching the workshop [over fifteen years]. I told him the story of how I came to be there. He laughed knowingly, ‘Mary Ellen is an easy person to say yes to.’”

Mary Ellen didn’t so much as teach, as much as push her students—to go further from wherever they were at that moment. “Just try to be a better photographer; that is enough,” she would say. She was highly intuitive with her students, with everyone, notes Wolff. She understood immediately who they were and could spot their strengths and also what was holding them back. “Don’t try to illustrate what happens; interpret it,” she would say. She was a tough editor; an “almost” picture was always a miss.

Wolff had worked with her before on her book of film stills (Seen Behind the Scene) but had never had the opportunity to see this side of her—the way she looked for the best in her students and how she championed them. And, how funny she was. At the workshop, a long-time student, Laurie Rae Baxter, was telling Mary Ellen about a man in the street who tried to spit on her when she was photographing. Mary Ellen asked, “Did you get his picture?!” Laurie laughed, no. “Coward,” Mary Ellen joked, “I would have taken his picture.”

Knowing that Mary Ellen was in poor health, for all of us the Workshop book as well as Tiny: Streetwise Revisited took on a different meaning and urgency. For the Workshop book, she poured over the text—“I don’t want to talk about creativity here, I want to talk about connection”—cutting to the heart of the matter. For both books, she didn’t put things off. Says Wolff: “We worked when she was tired, when she was busy, when she was not well, when she shouldn’t have been working. She saw the book through, adding new people to thank, to the day it went on press. I know she would be happier knowing that others will be reading her words and looking at this book, especially her students, than she would be in seeing it herself.” Both books were finalized first and signed off on by Mary Ellen a few weeks before she died. Sadly, she did not get to see them printed and bound.

Mary Ellen Mark’s first book with Aperture, and our first project together, was the facsimile reprinting of Streetwise in 1992. In 1997, her work in India was critical to Aperture’s publication and exhibition in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of India’s independence. This was soon followed in 1999 by the retrospective of her work photographed in the United States, American Odyssey—also a traveling exhibition that began at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and went to the International Center of Photography in New York, among other venues. Laser-focused, she was an excellent, sometimes unyielding, collaborator—impassioned, opinionated, open-minded at times, and single-minded at others. I also regularly featured Mary Ellen’s work in Aperture magazine when I was its Editor-in-Chief.

Mary Ellen was a force of nature, and her relationships reflected that intensity and engagement as well as an unwavering generosity. I always thought she’d be one of the people I’d want in my lifeboat. At her and Martin’s studio, she was supported by two remarkable individuals who define grace under pressure—Meredith Lue, Library Manager, and Julia Bezgin, Studio Manager, whose dog, Cooper, accompanies her to the studio every day, which delighted Mary Ellen. The studio always seems a flurry of activity, with Martin in the back space, working on his films: most recently, Tiny, which is to come out with Mary Ellen’s book in the fall.

If you were a young photographer in whose work Mary Ellen found something of merit—you could be certain she would call everybody she knew who might be able to help you. I say this having been on the receiving end of these “you must see” calls for twenty years. And, even if I had wanted to, it was impossible to say no to Mary Ellen. If you didn’t like the work that was one thing—you were just wrong—but not to look: that was not tolerated. She had a wonderful eye and was an extraordinary teacher.

Letizia Battaglia, whose work demanding justice in mafia-plagued Sicily moved and impressed Mary Ellen, remembers: “I have deeply loved Mary Ellen Mark since about 1975. And then her photos of the psychiatric hospital [Ward 81, 1979] and all the others were a model for me, an example of elegant and sincere reportage. . . . I respect her work, but also the delicacy of her way of living. I remember that in Arles, perhaps the first year there was an Arles [photo festival]; she was a teacher there. I didn’t have the money to pay for the workshop and, keeping it a secret from the organizers, she brought me into her group.”

If you were Tiny and her ten children, it meant receiving Christmas gifts for the kids, for thirty years. And, after Aperture’s Executive Director and Publisher, Michael Hoffman, unexpectedly died in 2001, Mary Ellen, with Lynne Honickman, put together a stunning collection of photographs in his honor, which was donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

One could not have a more vital, more sensitive friend. And her fierce loyalty and generosity extended as well to animals—she loved elephants, pigs, chimps, goats, donkeys . . . and especially dogs.

If you were a stray dog, wandering around Oaxaca, at risk of going to the pound, Mary Ellen was mission-driven. Her first rescue was Gringo—much beloved, and still living with her close friend, Diana Haas, who met the puppy while taking one of Mary Ellen’s workshops. When I interviewed her for her book, Man and Beast, Mary Ellen told me: “Since the success with Gringo, I’ve taken it upon myself to find dogs for my Oaxaca workshop students, to convince my students to adopt dogs. And several of them do, and they have happy lives. I follow up. There are a lot of stray dogs in Oaxaca, and the dogcatchers go after them. After I had a couple of fistfights with dogcatchers in the Zócalo, they now let me take them.”

Mary Ellen also loved Cholo, the Mexican hairless dog of her dear friends in Oaxaca, the painter, Francisco Toledo, and his wife, the Danish weaver, Trine Ellitsgaard. Trine wrote me the other day: “I am so very sad, she was my most special friend ever, and a kind of lifesaver for me and my children, always. We are doing a show of forty prints beginning Saturday in Centro Fotográfico here in Oaxaca, in memory of all that she has done for Oaxaca. I will tell you something strange that for me and Francisco has been so connected to Mary Ellen: We had two dogs who Mary Ellen loved very much; she always brought them presents and dog sweets from New York every time she came, and always asked about their being. They both passed away a few days before Mary Ellen. Francisco and I like to believe that they left to be there, on the other side, to receive her . . . It is overwhelming to lose my three loved ones together, but I can excuse my dogs if their plan was to be with Mary Ellen.”

Mary Ellen also found a home for a neglected dog belonging to the Damm family, a family, as with Tiny’s, who she photographed repeatedly—the first time when they were living in their car in the late 1980s. With this shattering revelation, she created one of the many iconic images of her life, and in the life of the medium itself.

And then there was the annual, much anticipated, “Doggy Christmas.” Dozens of often dubious dogs, chaperoned by excited friends and colleagues, poured into the SoHo studio, both to party and to have their portraits taken. Sometimes the dogs were costumed by theme, or there were props or backdrops or characters, but inevitably, the dog would sit on the platform—the studio set up as it might be if Mary Ellen was photographing any politician or actor—while assistants scurried about. If Mary Ellen was not satisfied by the composition, she’d instruct the unsuspecting beagle or Lhasa apso or greyhound to move “stage right” and “upstage,” along with other, non-doggy directions.

Mary Ellen loved India and Mexico, and more recently, Iceland, as does Martin, and created signature stories in all places—including her 1981 color work on the prostitutes of Falkland Road in Bombay, where she embedded for six weeks and with a muted, but striking palette conveyed a ravaged and sensual world, without sentimentality. About her work on the Indian circus, John Irving, who spent some time with Mary Ellen when she was photographing there, wrote in his foreword to that book, “The Indian circuses reflect an atavistic and compassionate life, which Mary Ellen has depicted with disturbing honesty and compelling affection.”

With the circus projects, in India and later in Mexico, she told me that she was “looking for the anthropomorphic things in animals.” When photographing children, on the other hand, she was looking for the “beast.” “There’s an innocence sometimes in children, which is similar in animals. But I rarely look for the innocence. Children are ‘Man.’ They can be very cruel. They’re tiny humans. That’s what I try to look for in children. I’m looking for the things they do that reveal their true nature.”

She also did quite a lot of work on Mother Teresa. Although slightly more sympathetic, I believe she ultimately concurred, more or less, with Christopher Hitchens’s take on Mother Teresa as expressed in his book, The Missionary Position. At the time, Mary Ellen could not reconcile the vast amounts of money Mother Teresa was able to raise, with the shabby and ridiculously low-tech condition of her hospitals: she seemingly could have afforded to build the most modern, high level medical facility for the suffering people she was so committed to helping. Still, Mary Ellen’s work on Mother Teresa tenderly and respectfully declares her as a force to be reckoned with. On the willfulness front, they were certainly well matched.

In 2002 when the beatification of Mother Teresa transpired, Mary Ellen and I thought, wouldn’t it be great to tie the pub date of a potential book, into her potential sainthood? So, I called art director Yolanda Cuomo, who I knew had friends in high places. Yo called up her pal, Monsignor Michele Prattichizzo, who works at the Vatican in what we referred to as the Department of Saints. At the time, Mother Teresa had realized most of the requirements, but there were still some miracles pending. We decided to wait for the miracles.

Mary Ellen’s portraiture went through a transition when she started to use the Polaroid 20 x 24 camera. Entirely set up, although there was no longer the spontaneity of context, movement, or angle, she achieved a different kind of directness by virtue of being literally so close, and needing to direct her subjects more than she had chosen to do previously. Martin made films for both the Twins project (the book was published by Aperture in 2003) and Proms, first published in Aperture magazine, and then as a book in 2012 by J. Paul Getty Museum, and also exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as well as, in part, at the LOOK3 Festival of the Photograph in Charlottesville, Virginia, including to the public’s excitement, the Charlottesville prom. There is a poignancy and frankness to both projects, and humor that comes across especially in the films.

Mary Ellen asked me to go on two shoots for Proms to help Martin with the interviewing process for his film. The first was a Staten Island high school prom held at Chelsea Piers in New York. Mary Ellen was gleeful that the previous year, the graduating students must have behaved so badly that the Pierre Hotel would not allow this year’s class back at any price. The second was a high school prom in Ithaca, New York, that she somehow convinced me entailed just a two-hour drive. Six hours later, interviewing these students on the cusp of life part two, and watching Mary Ellen, witty and kind, unintimidating, gently bossy give them the first degree as she positioned them—“So, are you two having sex? Do your parents know?” Or, “Are you in love?”—this behind-the-scenes experience afforded me exceptional insight.

Michael “Nick” Nichols, who “amazed” Mary Ellen because of how he conveyed “the intimate side of the lives of animals,” wrote: “I’m sixty-two and have been around a while. Mary Ellen was one of the first photographers whose work I admired, and who had an influence on me and so many others. She never stopped working. When I was able to see her actually working on Proms in Charlottesville, it all became clear. The camera was not there, it was MEM looking a stranger in the eye, and getting exactly what she wanted to come through. Finally she was so tough on herself, and the whole system, and she was never satisfied with her place in the publishing and Art world. But as a giver and teacher outside that world, she was endlessly generous. I will miss her. In no way was I ready for her to leave. She slipped away.”

Watching her relate to her subjects, so visually goal-oriented, but with such honesty, and almost feral alertness—spotting when she had triggered something, and then going there graciously, sympathetically, sometimes aggressively, I understood how her work may suggest something about her subjects’ interior lives which even they have yet to understand.

Donna Ferrato, whose reportage and advocacy on behalf of battered women Mary Ellen believed in, and found so powerful, states: “What made Mary Ellen Mark a strong photographer was her vulnerability. She allowed herself to feel things and to express them, and she genuinely loved and cared about the people she was photographing. She had the gift of a truly great photographer: the gift of being able to sense and to put into a photograph not only what she felt, but what the people on the other side of the camera felt, as well. Mary Ellen hated the term ‘woman photographer,’ and always said she was ‘a photographer first.’ But to me, it was her strength as a woman, her willingness to be vulnerable, her fighting spirit, that made her exceptional; she was a warrior, a lioness, and I always trusted her.”

Mary Ellen never exploited a situation, never exploited someone else’s pain or difficult conditions. Her work was simultaneously uninflected and deeply inflected. That is, she got you to feel, without telling you what or how to feel. She was passionate and compassionate. Life mattered. Animals mattered. People mattered.

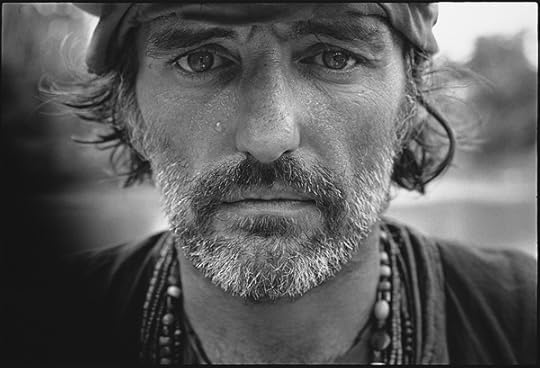

Eugene Richards, the photographer with whom Mary Ellen felt perhaps the closest kinship, and whose often wrenching work got under her skin, and moved her enormously, wrote me of Mary Ellen’s death, and the recent loss of another dear, extraordinarily present, brilliant friend of his and mine: “I don’t know if it’s appropriate to be relating the recent loss of one deeply creative friend with the loss of another deeply creative friend. But I can’t help it. To my mind, you see, Mary Ellen and the great writer Chuck Bowden, who died last August, were not in fundamental ways dissimilar. Both were relentless workers, both provocative presences, meaning that when they entered a room, they by force of personality dominated the room. Both loved and hated the magazine world that they toiled in; both chose their own artistic paths, had distinctive voices, and only seldom wavered from them. Both were, at times, scarily intense and self-occupied, while capable of deeply heartfelt personal revelations and emotion. And, not to belabor the comparison, both of them lived their lives out in big ways, while giving a lot back.”

There was rarely, if ever, ambiguity with Mary Ellen. There was minimal gray area. She was empathetic, kooky sometimes, tempestuous at other times, always attentive, always intense, and you always knew how she felt, where she stood, where you stood, and why. And as photography editor Laurie Kratochvil wrote to me, “Mary Ellen did not suffer fools gladly…” In her darker moments, Mary Ellen could have a piercing disdain for the art/photography world, and for the decline of the editorial possibilities for documentary photographers in magazines, and at times—very unfortunately—felt slighted by them, no matter how hard one tried to dissuade her. And yet, this would pass, and then recur like a turbulent thunderstorm.

One afternoon this past winter when I was at the studio working with Mary Ellen and Martin on the Tiny: Streetwise Revisited texts, Mary Ellen drifted away from the work at hand to tell me about a poem by Robert Frost, “Birches,” that Martin had read to her that morning. She especially loved the final passages:

So was I once myself a swinger of birches. / And so I dream of going back to be. / It’s when I’m weary of considerations, / And life is too much like a pathless wood / Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs/ Broken across it, and one eye is weeping / From a twig’s having lashed across it open. / I’d like to get away from earth awhile / And then come back to it and begin over. / May no fate willfully misunderstand me / And half grant what I wish and snatch me away / Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better. / I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree, / And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk / Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more, / But dipped its top and set me down again. / That would be good both going and coming back. / One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

Then, Mary Ellen added: “I remember when I must have been around four years old, I had been very ill, deathly ill. And then I woke up one morning and I was feeling better. It was spring. I looked out a window in my grandfather’s house. It was on the second or third floor. And this tree, with these beautiful flowers—apples maybe, or magnolias—they were flowers that smelled so sweetly on the breeze: warm wind, and the flowers moving. I remember being so happy and grateful for life.”

Mary Ellen Mark died on Monday May 25 from pneumonia, a result of lowered immunity from myelodysplastic syndrome, a disease affecting bone marrow and blood. She was seventy-five.

I keep thinking of Mary Ellen’s long, signature braids, flowing clothes with sweeping scarves, uniquely intricate silver jewelry—often made by friends. I remember Tiny calling her “exotic” when we spoke some years ago. Mary Ellen had such presence. She and her images influenced and are loved, respected, and admired by so many. The world feels lesser without her.

—Melissa Harris, May 31, 2015

The post Remembering Mary Ellen Mark, 1940–2015 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers