Aperture's Blog, page 160

May 11, 2015

Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Inside Issue 7 our readers can find:

● Where in the World is Aperture? an interview with Aperture’s exhibitions manager, Annette Booth.

● From the upcoming Summer 2015 issue of Aperture magazine: LaToya Ruby Frazier’s favorite anythings

● An interview from The PhotoBook Review on Jason Fulford’s madcap book events

● An archival interview with Daido Moriyama

● A Q&A on Chance and Photography, a new book from Robin Kelsey that explores the accident and the camera

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free: select articles later appear here on the Aperture Blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 7 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 8, 2015

David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin

In September of 1990, AIDS activist, writer, and artist David Wojnarowicz and photographer Nan Goldin, longtime friends, sat down for a three-hour conversation on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Their conversation was originally commissioned by Interview magazine and Brant Publications, and excerpts were originally published in Interview’s February 1991 issue. The following excerpt was published in Aperture #137, from the fall of 1994, in an issue solely dedicated to the work of Wojnarowicz. In 1991, Wojnarowicz had been in talks with Aperture’s editors to publish a book of his work but he died of AIDS in July 1992 before the project was completed; the editors then posthumously published Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, as both a book and as a monographic issue of the magazine. “Not since Aperture’s earliest years—before there was a book publishing program—has an issue of the magazine been entirely devoted to the work of one contemporary artist,” the editors wrote in that issue. This year, on the twentieth anniversary of its publication, Aperture is releasing a new edition of Brush Fires in the Social Landscape. This excerpt also appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

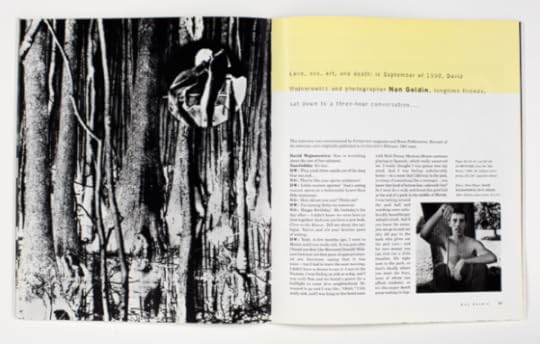

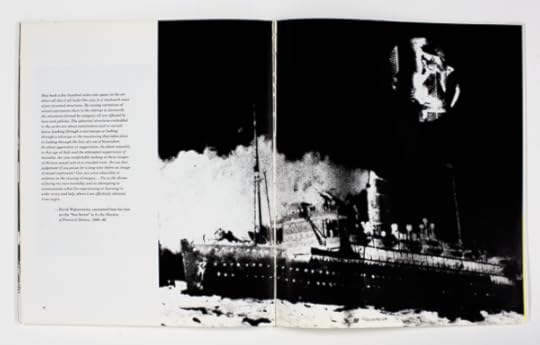

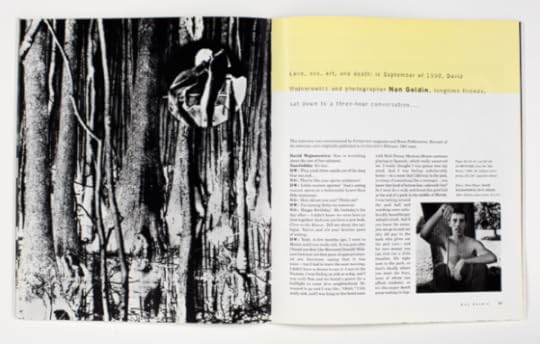

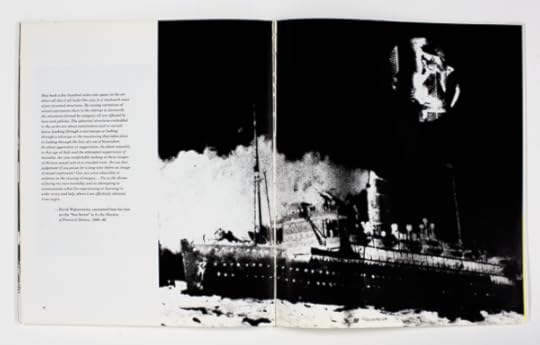

Spreads from Aperture magazine #137. Photographs by Thomas Bollier

David Wojnarowicz: Nan is kvetching about the size of her calamari.

Nan Goldin: It’s tiny.

DW: They yank these squids out of the deep blue sea and . . .

NG: They’re like your sperm sculptures!

DW: Little mutant sperms! Nan’s eating mutant sperm at a fashionable Lower East Side restaurant.

NG: How old are you now? Thirty-six?

DW: I’m turning thirty-six tomorrow.

NG: Happy Birthday! My birthday’s the day after—I didn’t know we were born so close together. And now you have a new book, Close to the Knives. Tell me about the epilogue. You’ve said it’s your favorite piece of writing.

DW: Yeah. A few months ago, I went to Mexico and I was really sick. It was just after I found out that [the Reverend Donald] Wildmon had sent out that piece of appropriationist sex literature saying that it was mine—but I had to leave the next morning, I didn’t have a chance to see it. I was in the Yucatan. I was feeling as sick as a dog, and I was with Tom and we found a poster for a bullfight in some dive neighborhood. He wanted to go and I was like, “Ohhh.” I felt really sick, and I was lying in his hotel room with Walt Disney Mexican Mouse cartoons playing in Spanish, which really unnerved me. I really thought I was gonna lose my mind. And I was feeling unbelievably horny—in a sense that I did way in the past, in terms of something like a teenager . . . you know that kind of bottom-line, sidewalk lust? So I went for a walk and found this pool hall and watching some believably beautiful guy unload a truck. And if you know the scene, you can go in and see this old guy in the back who gives out the pool cues—and for zero money you can rent out a little chamber. It’s right next to the park, so that’s ideally where you meet the boys, none of whom can afford condoms, so it’s this major death scene waiting to happen.

I was feeling this intense lust, just standing on the street corner in a daze, having these thoughts of lustful sex, and . . . and it got very frustrating, so I went back and told Tom, “Okay let’s go to the bullfight.” I figured maybe blood would wake me up, or snap me out of this daze. And during this bullfight I kept this journal which was horrifying. I mean, I’d seen a bullfight before on TV in Mexico City, and there was one guy who killed the bull—I suddenly understood what the sport was. Because it was one of the most unbelievable movements of the male body through space, so extraordinarily beautiful that the death was like a climax. And it made perfect sense in a very profound way. But these guys were like horrendous bullfighters, and they were totally carving up these bulls in the ring. So while I was there I started writing this piece, and it jumps between all the events of my childhood, from my first sexual experience as a six- or seven-year-old kid to the experience of my father, who was completely brutal and sadistic, to all these images of violence that I remember as a child.

My earliest memory is of hearing a police siren go by. And I remember running blocks to follow it and when I got there there was this guy in a white T-shirt on a front lawn with a gun to a woman’s head. So my piece jumps in all these random violent scenes in Jersey, and then sexual scenes, and it’s interspersed with this tense buildup of the bullfight. I sat there and just notated every description and color and smell, all the dust and the heat. I wove in some of the fantasy stuff from the pool hall and the guy unloading the truck, following that through in my imagination and getting the key and going to the room and crawling across the bed at him . . .

NG: Listening to you it seems like there’s no difference for you between then and now; your visual and verbal memories are so acute. I read your story about your trip to the meteor crater and it was like a road movie. I had the best sex after reading it.

DW: Wow, that’s great! My strongest memories are always connected to really powerful images, images that I can drift on, that I can never forget. Years ago, a trucker told me that driving a truck was the one thing in the world that made the most sense for people to do because you’re essentially at rest in the seat of the truck, and you’re alone. You’re encapsulated by the form of the vehicle—but at the same time your landscape is forever changing, so it’s not the same thing as being at home. It’s almost like the perfect state of being, to be floating through a landscape and at rest at the same time. I always love that feeling of riding in a car, except that mental stuff gets very, very intense. Your brain starts chattering away. Plus it gets very sexual, very sensual. You start populating that car with men.

. . .

NG: You write for relief from your own perceptions, but is it also because you think its important to leave a record? I think America is the land of revisionist memory.

DW: Absolutely. My two biggest impulses for writing the book were: if some kid gets a hold of it and would feel less alienated, great. I really suffered as a teenager, because I never had any indication n that there was anything out there that reflected myself. But I also wanted to leave a record. Because once this body drops I’d like some of my experience to live on. It was a total relief to have put words to what I put words to, an enormous relief.

NG: How did you go from living on the streets to living on the Lower East Side?

DW: I went to this halfway house for ex-cons. They thought I was so desperate that I’d become a convict if they didn’t take me in. Then I worked in manual labor here in New York and in custodial jobs. I mean, the same shit I’m doing now, you know. [Laughing.] In the art world. Just shifting through society’s garbage.

NG: Were you writing at the time?

DW: Yeah. I’ve been writing since I got off the streets. I started out writing bad poems, and then I started with the monologues in my early twenties. I’ve also made things since I was a kid. I used to make sexual “Archie” comics out of collage and then throw them down the incinerator whenever I’d hear my family coming home.

NG: When did you start showing your work publicly?

DW: Around 1982. Some jerk-off in SoHo actually called up Peter Hujar and asked him if he knew who had done these stencils on these abandoned cars on the Lower East Side. When I lived on the Bowery, whenever there was a car wreck, they dragged the wreck right outside my apartment and they’d leave it there for eight or nine months. Then I discovered that if I stenciled these images of war all over the wrecks, they’d tow them overnight. So for a while, I did that, and then I started stenciling on the walls and then I went through SoHo and spray-painted all these gallery doors with burning houses. I was going these action installations, along with Julie Hair, where we took a hundred pounds of bloody cow bones and threw them down the staircase at Leo Castelli’s, and stenciled an empty plate and knife and a fork on the wall, and then we ran off. This was right in the middle of a Saturday afternoon. Nobody raised an eyelash.

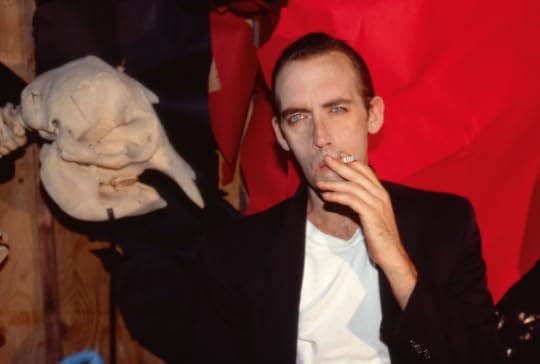

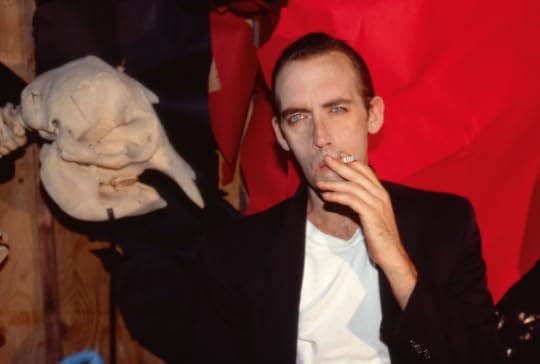

Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz at Home, New York City, 1991 © Nan Goldin, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

NG: How do you feel about the art world right now?

DW: If the art world was reduced—if conditions in this country increase in the direction they’ve been going, and suddenly all art was made to look like tiny refrigerators, the art world wouldn’t falter for a moment. I think that the real power structure, the money structure, the boards of museums and institutions, 98 percent of these people would be happy to keep a market alive for small refrigerators. And those are the people who should be held accountable for the state of things in this country. They’ve never collected real culture in this country. Their mirror is completely tarnished. The only thing they reflect is their investments and their private collections.

NG: What would you like your work to do?

DW: I want to make somebody feel less alienated—that’s the most meaningful thing to me. I think part of what informs the book is the pain of having grown up for years and years believing I was from some other planet.

NG: A lot of people I know still see you as kind of a moral conscience for our time. How does that make you feel?

DW: I want people to hear me. I want to be understood and acknowledged to a certain extent. But do I think that something I say might have the weight to shift something? I don’t know.

NG: It does for me. It does for a lot of people.

DW: Good, but then you also have that effect on me. We can all affect each other, by being open enough to make each other feel less alienated. We all are able to have a profound effect on each other, a positive effect that sustains us. . . . But I ain’t no Jesus.

Tap here to learn more about the Aperture Magazine Digital Archive.

The post David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Archive: David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin

In September of 1990, AIDS activist, writer, and artist David Wojnarowicz and photographer Nan Goldin, longtime friends, sat down for a three-hour conversation on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Their conversation was originally commissioned by Interview magazine and Brant Publications, and excerpts were originally published in Interview’s February 1991 issue. The following excerpt was published in Aperture #137, from the fall of 1994, in an issue solely dedicated to the work of Wojnarowicz. In 1991, Wojnarowicz had been in talks with Aperture’s editors to publish a book of his work but he died of AIDS in July 1992 before the project was completed; the editors then posthumously published Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, as both a book and as a monographic issue of the magazine. “Not since Aperture’s earliest years—before there was a book publishing program—has an issue of the magazine been entirely devoted to the work of one contemporary artist,” the editors wrote in that issue. This year, on the twentieth anniversary of its publication, Aperture is releasing a new edition of Brush Fires in the Social Landscape. This excerpt also appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Spreads from Aperture magazine #137. Photographs by Thomas Bollier

David Wojnarowicz: Nan is kvetching about the size of her calamari.

Nan Goldin: It’s tiny.

DW: They yank these squids out of the deep blue sea and . . .

NG: They’re like your sperm sculptures!

DW: Little mutant sperms! Nan’s eating mutant sperm at a fashionable Lower East Side restaurant.

NG: How old are you now? Thirty-six?

DW: I’m turning thirty-six tomorrow.

NG: Happy Birthday! My birthday’s the day after—I didn’t know we were born so close together. And now you have a new book, Close to the Knives. Tell me about the epilogue. You’ve said it’s your favorite piece of writing.

DW: Yeah. A few months ago, I went to Mexico and I was really sick. It was just after I found out that [the Reverend Donald] Wildmon had sent out that piece of appropriationist sex literature saying that it was mine—but I had to leave the next morning, I didn’t have a chance to see it. I was in the Yucatan. I was feeling as sick as a dog, and I was with Tom and we found a poster for a bullfight in some dive neighborhood. He wanted to go and I was like, “Ohhh.” I felt really sick, and I was lying in his hotel room with Walt Disney Mexican Mouse cartoons playing in Spanish, which really unnerved me. I really thought I was gonna lose my mind. And I was feeling unbelievably horny—in a sense that I did way in the past, in terms of something like a teenager . . . you know that kind of bottom-line, sidewalk lust? So I went for a walk and found this pool hall and watching some believably beautiful guy unload a truck. And if you know the scene, you can go in and see this old guy in the back who gives out the pool cues—and for zero money you can rent out a little chamber. It’s right next to the park, so that’s ideally where you meet the boys, none of whom can afford condoms, so it’s this major death scene waiting to happen.

I was feeling this intense lust, just standing on the street corner in a daze, having these thoughts of lustful sex, and . . . and it got very frustrating, so I went back and told Tom, “Okay let’s go to the bullfight.” I figured maybe blood would wake me up, or snap me out of this daze. And during this bullfight I kept this journal which was horrifying. I mean, I’d seen a bullfight before on TV in Mexico City, and there was one guy who killed the bull—I suddenly understood what the sport was. Because it was one of the most unbelievable movements of the male body through space, so extraordinarily beautiful that the death was like a climax. And it made perfect sense in a very profound way. But these guys were like horrendous bullfighters, and they were totally carving up these bulls in the ring. So while I was there I started writing this piece, and it jumps between all the events of my childhood, from my first sexual experience as a six- or seven-year-old kid to the experience of my father, who was completely brutal and sadistic, to all these images of violence that I remember as a child.

My earliest memory is of hearing a police siren go by. And I remember running blocks to follow it and when I got there there was this guy in a white T-shirt on a front lawn with a gun to a woman’s head. So my piece jumps in all these random violent scenes in Jersey, and then sexual scenes, and it’s interspersed with this tense buildup of the bullfight. I sat there and just notated every description and color and smell, all the dust and the heat. I wove in some of the fantasy stuff from the pool hall and the guy unloading the truck, following that through in my imagination and getting the key and going to the room and crawling across the bed at him . . .

NG: Listening to you it seems like there’s no difference for you between then and now; your visual and verbal memories are so acute. I read your story about your trip to the meteor crater and it was like a road movie. I had the best sex after reading it.

DW: Wow, that’s great! My strongest memories are always connected to really powerful images, images that I can drift on, that I can never forget. Years ago, a trucker told me that driving a truck was the one thing in the world that made the most sense for people to do because you’re essentially at rest in the seat of the truck, and you’re alone. You’re encapsulated by the form of the vehicle—but at the same time your landscape is forever changing, so it’s not the same thing as being at home. It’s almost like the perfect state of being, to be floating through a landscape and at rest at the same time. I always love that feeling of riding in a car, except that mental stuff gets very, very intense. Your brain starts chattering away. Plus it gets very sexual, very sensual. You start populating that car with men.

. . .

NG: You write for relief from your own perceptions, but is it also because you think its important to leave a record? I think America is the land of revisionist memory.

DW: Absolutely. My two biggest impulses for writing the book were: if some kid gets a hold of it and would feel less alienated, great. I really suffered as a teenager, because I never had any indication n that there was anything out there that reflected myself. But I also wanted to leave a record. Because once this body drops I’d like some of my experience to live on. It was a total relief to have put words to what I put words to, an enormous relief.

NG: How did you go from living on the streets to living on the Lower East Side?

DW: I went to this halfway house for ex-cons. They thought I was so desperate that I’d become a convict if they didn’t take me in. Then I worked in manual labor here in New York and in custodial jobs. I mean, the same shit I’m doing now, you know. [Laughing.] In the art world. Just shifting through society’s garbage.

NG: Were you writing at the time?

DW: Yeah. I’ve been writing since I got off the streets. I started out writing bad poems, and then I started with the monologues in my early twenties. I’ve also made things since I was a kid. I used to make sexual “Archie” comics out of collage and then throw them down the incinerator whenever I’d hear my family coming home.

NG: When did you start showing your work publicly?

DW: Around 1982. Some jerk-off in SoHo actually called up Peter Hujar and asked him if he knew who had done these stencils on these abandoned cars on the Lower East Side. When I lived on the Bowery, whenever there was a car wreck, they dragged the wreck right outside my apartment and they’d leave it there for eight or nine months. Then I discovered that if I stenciled these images of war all over the wrecks, they’d tow them overnight. So for a while, I did that, and then I started stenciling on the walls and then I went through SoHo and spray-painted all these gallery doors with burning houses. I was going these action installations, along with Julie Hair, where we took a hundred pounds of bloody cow bones and threw them down the staircase at Leo Castelli’s, and stenciled an empty plate and knife and a fork on the wall, and then we ran off. This was right in the middle of a Saturday afternoon. Nobody raised an eyelash.

Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz at Home, New York City, 1991 © Nan Goldin, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

NG: How do you feel about the art world right now?

DW: If the art world was reduced—if conditions in this country increase in the direction they’ve been going, and suddenly all art was made to look like tiny refrigerators, the art world wouldn’t falter for a moment. I think that the real power structure, the money structure, the boards of museums and institutions, 98 percent of these people would be happy to keep a market alive for small refrigerators. And those are the people who should be held accountable for the state of things in this country. They’ve never collected real culture in this country. Their mirror is completely tarnished. The only thing they reflect is their investments and their private collections.

NG: What would you like your work to do?

DW: I want to make somebody feel less alienated—that’s the most meaningful thing to me. I think part of what informs the book is the pain of having grown up for years and years believing I was from some other planet.

NG: A lot of people I know still see you as kind of a moral conscience for our time. How does that make you feel?

DW: I want people to hear me. I want to be understood and acknowledged to a certain extent. But do I think that something I say might have the weight to shift something? I don’t know.

NG: It does for me. It does for a lot of people.

DW: Good, but then you also have that effect on me. We can all affect each other, by being open enough to make each other feel less alienated. We all are able to have a profound effect on each other, a positive effect that sustains us. . . . But I ain’t no Jesus.

Tap here to learn more about the Aperture Magazine Digital Archive.

The post Archive: David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 7, 2015

Collecting the Japanese Photobook

Ryuichi Kaneko interviewed by Ivan Vartanian

Ryuichi Kaneko is a leading historian of Japanese photobooks, and over the course of four decades he has amassed a formidable collection of twenty thousand volumes, including magazines and catalogues. In his role as curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, from its nascency up until this year, he oversaw the development of the institution’s public collection. As a scholar, Kaneko has been an important figure in supporting and extending scholarship surrounding Japanese photography and photobooks. Ivan Vartanian, who guest edited the latest issue of The PhotoBook Review , spoke to him about how he became one of the first and most enduring champions of the Japanese photobook, the evolution of the form, and what makes a book irresistible. This article also appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Ivan Vartanian: You began collecting books at a time when no one else had interest in Japanese photobooks. How and why did you start?

Ryuichi Kaneko: It started in high school and university, when I was taking photographs and realized I possessed absolutely no talent for it. But I loved photography. My father was an amateur photographer, and after the war he worked as an editor at a fashion magazine, which influenced me too, with all the exposure to material it provided. Since I couldn’t make images, I thought intensely about what I could do that would connect me with the world of photography, and started to just consume and absorb whatever materials I could get my hands on. Photobooks were a vehicle for that.

The first Japanese photobook I ever purchased was Otoko to onna [Man and Woman, 1961] by Eikoh Hosoe. And the first book I purchased by a foreign photographer, in 1967 or ’68, was William Klein’s New York [1956]. Around that time, 1967 or ’68, I started to become acquainted with a lot of photographers, and by 1974 or ’75 I started to buy books actively.

Kazuhiko Motomura is a publisher and editor who made Robert Frank’s The Lines of My Hand [1972] with Yugensha. When I ordered a copy of the book, Motomura delivered it by hand to my door. And from there started a long friendship and a sort of mentorship. He introduced me to a slew of photographers, bookstores, and bookstore owners, particularly in the Kanda area of Tokyo. After that, Kanda became my library, where books and magazines could be bought. My passion became my mission.

And it was just about this time that independent galleries were operating in Tokyo. To the photographers in these places— which were hangouts as much as they were noncommercial exhibition spaces—I became known as the guy who had all these photobooks from Japan and the West. It was an opportunity, or excuse, if you like, to talk to photographers and be connected to the medium that I loved so much. For example, at Photo Gallery Prism, I met photographers Hitoshi Tsukiji, Kineo Kuwabara, and Hiroshi Yamazaki. At Image Shop Camp, I met Keizo Kitajima. These photographers were of the same generation as me. That was an important point because they had an antiestablishment way of thinking.

IV: So what was the experience of buying photobooks at that time?

RK: It wasn’t simple. There weren’t a lot of photobooks by Japanese photographers. And of those that were in existence, only a handful were worth buying, like Shomei Tomatsu’s Taiyo no empitsu [The pencil of the sun, 1975] or Kikuji Kawada’s Sacré Atavism [1971]. But there were several gems from the West: Lee Friedlander’s Photographs [1978], Garry Winogrand, Nathan Lyons, and Bruce Davidson, as well as Aperture’s Paul Strand and Walker Evans retrospectives. There was also Dorothy Norman’s book on Stieglitz, An American Seer [1973], which I went around and showed to everyone, and it changed our impression of Stieglitz. It was this process that led me to become interested in the history of photography, too.

IV: After the mid-1970s, with the proliferation of photobooks, were you able to keep up?

RK: I bought pretty much ninety percent of everything that was published then. I don’t think you can imagine this: I would go to Kanda twice a week, and then Waseda, to visit used bookstores. And of course Shinjuku’s Kinokuniya bookstore. Unlike now, when there is a surplus of books, at that time there weren’t many Japanese photobooks to buy. How could I use the ¥10,000 I had in my hand? There were days when I couldn’t find a single book to buy and would go home feeling dejected.

IV: Were there any other people buying photobooks at that time?

RK: No! There was no one else.

IV: So how did this culture of collecting books grow in Japan?

RK: It’s thanks to me and Kotaro Iizawa. He, too, was studying Japanese photo history, and when we eventually met we realized we were both doing pretty much the same thing at the same time. Iizawa often said that we needed to change the culture from the enjoyment of taking photographs to the enjoyment of looking at photographs. That was in the first half of the 1980s, just before I started working at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. But the culture of actually enjoying reading Japanese photobooks didn’t evolve until after the 1990s. The 1980s were about foreign photobooks, but I was a cheerleader for Japanese photobooks.

IV: Were there any dramatic shifts in the form of Japanese photobooks between the 1960s and the ’80s?

RK: No, except for the dramatic improvements in printing technique. It was something that became apparent later. There was gravure printing in the beginning, after the war, and then after the 1970s it was all offset printing. But there still wasn’t this sense that a photobook was a function of its printing. That would be entirely the influence of the American photobook, which was recognized in Japan in the 1980s.

IV: Japanese photobooks have special value as the vehicles by which a lot of Japanese photography has been seen by the West. Do you think some distortion has resulted from this, by not seeing the prints themselves and only seeing the work in the form of photobooks?

RK: In Japan the photobook has had special significance for photographers from the 1930s onward; from the 1950s to the 1970s, there was a widely accepted understanding that there were certain modes of expression that could only be achieved in the form of a photobook. The print was forgotten to a certain degree. And when it came to academic matters of collecting, which is what I did as a curator for the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, the first selection of images was often based on what was in photobooks. Quite frankly, many Japanese photographers are quite unconcerned with how work is shown in a gallery setting because the photobook is already out in the world and circulating among people.

It is precisely because of this imbalance that Japanese photobooks have their unique sensibility and can achieve new levels of expression. A great example of this would be the 1963 version of Eikoh Hosoe’s Barakei, which was printed in gravure. You could cut those pages out of the book and frame them. One shot of Yukio Mishima staring into the camera at close range has not only become a symbol of that body of work, it has become iconic. So when the prints from that series are sold, that image gets prominence over the other images, and the book’s context and complexity get lost.

IV: So how about contemporary photobooks? Are you actively collecting those too?

RK: [laughs] To be totally frank, it’s no different from the situation I was facing back in the 1970s. It’s very difficult to find a book I feel I must own. There are a lot of books out there now, which is like a dream come true, but sadly only a few make it into my collection. There are few books that communicate an innate need to exist, or to even be a photobook to begin with. Then there are the books that you just take one look at and know, “I must own this.” That’s what I’m looking for when I visit bookstores.

Translation from Japanese by Ivan Vartanian.

Ivan Vartanian is a Tokyo-based independent curator and author as well as the founder of the imprint Goliga.

Ryuichi Kaneko is a critic, historian, and collector of photobooks. He has authored or contributed to numerous publications, including Independent Photographers in Japan 1976–83 (Tokyo Shoseki, 1989),The History of Japanese Photography (Yale University Press and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003), Japanese Photobooks of

the 1960s and ’70s (Aperture, 2009), and Japan’s Modern Divide (J. Paul Getty Museum)

Tap here to find more from The PhotoBook Review.

The post Collecting the Japanese Photobook appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 6, 2015

Inside the Aperture Spring Party

Jeffrey Kane of LTI/ Lightside Photographic Services. Photo by Max Mikulecky

The Aperture Spring Party: Moving Mountains drew more than 250 guests to the Aperture Foundation in Chelsea, New York on Friday, April 17 during the AIPAD Photography Show New York.

Aperture teamed up with photographer Penelope Umbrico (Range, Aperture 2014 and Penelope Umbrico: Photographs, Aperture 2011) to offer party attendees a unique, signed photograph from Umbrico’s Moving Mountains series.

Aperture published Umbrico’s first monograph in 2011, and this recent series takes the Aperture Masters of Photography Series as a jumping-off point, which Umbrico rephotographed using various camera apps and filters, re-rendering classic works by the likes of Edward Weston, Wynn Bullock, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Manuel Álvarez Bravo as almost entirely different images. (The series was recently featured in the New York Times Magazine’s new photography column by Teju Cole.) The event was co-chaired by Aperture trustees Elaine Goldman and Michael Hoeh, and featured a DJ set by Zachary Cole Smith of DIIV.

Prints from Umbrico’s 2015 Moving Mountains limited-edition series are available for purchase on Artsy. Print sale proceeds help to support all of Aperture Foundation’s free and low-cost public events and education programs as well as publishing a diverse roster of photobooks and internationally touring exhibitions. For questions, contact springparty@aperture.org or (212) 946-7103/7146.

Umbrico’s exhibition Shallow Sun is currently on view through October 25, 2015 at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

The Aperture Spring Party was generously supported by lead sponsor Stribling. Additional event support was provided by:

LTI/ Lightside Photographic Services

Additional party photos are on www.patrickmcmullan.com.

Event co-chair and Aperture trustee Michael Hoeh with Steve Houck. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Dublin and Gabrielle Wallace. Photo by Adair Ewin

Aperture Board of Trustees chair Cathy Kaplan with fellow Aperture trustees Jessica Nagle, James O’Shaughnessy, and Melissa O’Shaughnessy. Photo by Max Mikulecky

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s curator of photography Barbara Tannenbaum, guest of honor Penelope Umbrico, and photographer Simen Johan. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Photographer Hannah Whitaker and Aperture trustee David Solo. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Photographer Richard Renaldi and Aperture Paul Strand Circle Member Kate Cordsen. Photo by Max Mikulecky

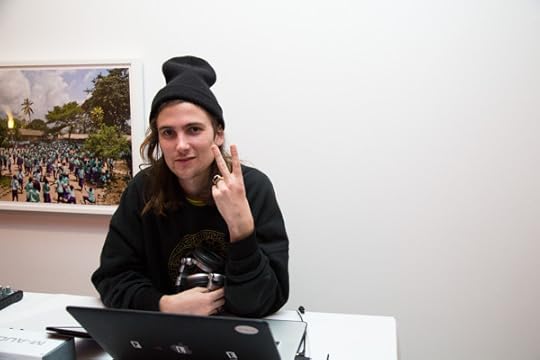

Zachary Cole Smith of DIIV. Photo by Anna Kamensky

Tim Doody and guest. Photo by Adair Ewin

Angela Ledgerwood, Erin Allweiss, and Ella Marder. Photo by Adair Ewin

Liz Grover, Lori Grover, Josh Rosen, and Harrison Grover. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Gallerist Yancey Richardson with Museum of Fine Arts, Boston curators Karen Haas and Anne Havinga. Photo by Adair Ewin

Spring Party guest with gallerist Lexing Zhang, and Aperture trustees Stuart Cooper and Rebecca Besson. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Aperture Spring Party atmosphere. Photo by Max Mikulecky

Photographer Rose Marie Cromwell, Aperture magazine’s managing editor Paula Kupfer, and Zara Katz. Photo by Adair Ewin

The post Inside the Aperture Spring Party appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 4, 2015

London Exhibitions of Photographers’ Collections

by Isabel Stevens

Installation view of Simon Fujiwara’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photograph: Linda Nylind

Two exhibitions in London currently highlight collections of art and oddities that belong to some of the most prominent photographers today. Magnificent Obsessions at the Barbican presents the objects belonging to photographers such as Martin Parr and Hiroshi Sugimoto while the Hayward Gallery’s History is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain has four photographers—Hannah Starkey, Jane and Louise Wilson, and Richard Wentworth—acting as curators of various section. Writer Isabel Stevens examines the theme. This review first appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

“You know how a collector is. He gets excessively conscious of a certain object and falls in love with it and then pursues it…And it’s compulsive and you can hardly stop.” –Walker Evans

The obsessive hunt of the collector is an activity and state of mind the photographer knows all too well. Walker Evans, who walked away with many of the flotsam, signs, and tools he gathered with his lens, and who was a life-long collector of picture postcards, regarded the two pursuits as “almost the same thing.” For isn’t the tendency to collect deepest ingrained in photographers and the nature of their medium? Consider conceptually-inclined artists with one-track minds fixed on subjects such as water towers (Bernd and Hilla Becher); photo-collagists from Hannah Höch to John Stezaker; archive rummagers such as Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel; Alec Soth and his shot lists of subjects to scavenge (suitcases, snow, unusually tall people); and, of course, Susan Sontag’s famous statements “To photograph is to appropriate the thing being photographed” and “to collect photographs is to collect the world.” When, in 1920, Eugène Atget remarked that “the collection has today almost completely disappeared,” he wasn’t just referring to his negatives, but the content of them—the curious façades, statues, fountains, and street vendors of old Paris.

Martin Parr, Venice, Italy, 2005 © Martin Parr/ Magnum Photos/ Rocket Gallery. From Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

Two exhibitions in London currently highlight photographers’ foraging acuities and their collecting habits. At the Barbican, Magnificent Obsessions presents artists’ personal collections, including Martin Parr and Hiroshi Sugimoto. Meanwhile the Hayward Gallery’s History is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain has four photographers— Hannah Starkey, Jane and Louise Wilson, and Richard Wentworth—acting as curators refracting moments and themes in Britain’s seventy-year postwar history through art works, artifacts, and archival documents.

These exhibition strategies are far from a new phenomenon. Sugimoto’s collection has been aired before (just not in the UK), and Parrworld, at the Jeu de Paume in 2009, showed off many of the photographer’s acquisitions, ranging from the bizarre (Saddam Hussein watches) to the banal (boring postcards). Similarly, both the Barbican and Hayward exhibitions have a Wunderkammer feel to them: vitrines and piles of unexpected, disparate objects and images.

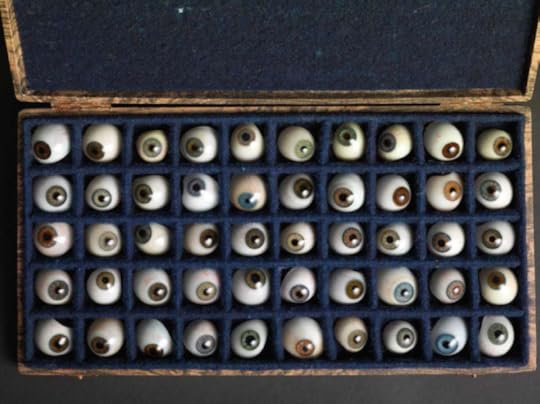

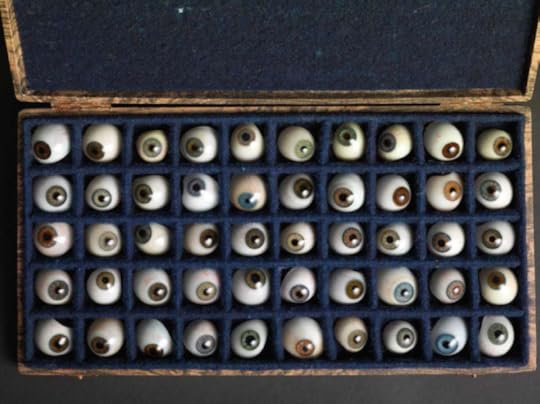

50 Glass Eyes, 1811–88 Collection of Hiroshi Sugimoto, from Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

While exhibitions generally present finished artworks and reference influences, an artist’s selection opens up the creative process and offers a view of sources of inspiration. In this case, showing a collection or curating a show becomes an act of self-portraiture, or even advocacy. Where an artist takes the role of a celebrity curator, he or she can introduce unknown artists to wider audiences in the ways that regular curators often can’t. In the case of photography, the opportunity it provides for rediscovery is particularly pertinent as the medium was looked down upon for so much of the twentieth century, and, as a result, offers historical gaps to fill. Martin Parr’s championing of photographers such as Tony Ray-Jones stands in a long tradition, reaching back to Berenice Abbott’s salvaging of Eugène Atget’s work.

Flying postcard, 1960–90. Collection of Martin Parr © Martin Parr Collection/ Magnum Photos/ Rocket Gallery. From Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

At the Barbican, Parr’s Soviet space-dog memorabilia isn’t nearly as fascinating as the early, pre–World War II postcards on show, which commemorate idiosyncratic sights and occasions such as giant bonfires and hailstones, car crashes and factory-smoke-filled landscapes that resemble miniature, monochrome Turner paintings. Beyond their salacious and strange everyday obsessions, which chime with Parr’s own, Parr also uncovers their artistry, particularly the elaborate, morbid collages of W. Gothard, which record and pay tribute to disasters.

While Parr’s collection offers the thrill of discovery, Sugimoto’s hardly raises an eyebrow. The aged optical curios in glass cabinets and ordered anatomical drawings lined on the wall, which at close quarters look almost abstract, are exactly what we might expect a photographer fascinated with perception, time, and surrealism to be attracted to. Ditto the most entrancing segment of this studied and austere presentation, Sugimoto’s fossils of sea creatures that call to mind the cyanotypes of Anna Atkins, who collected botanical specimens to preserve. Sadly, the William Henry Fox Talbot images from his collection aren’t on show. Those eager to know what other photographic treasures lie in his possession will have to wait for Sugimoto’s museum, the Odawara Art Foundation, scheduled to open in spring 2016. His sleek art complex is an enticing proposition, but you do hope that there’s also a future for dusty old museums.

Just as Sugimoto’s assemblage at the Barbican is too much of a scattershot self-portrait, so too is Jane and Louise Wilson’s display at the Hayward. It explores social unrest in British history, but too often through the prism of their own work. However, it does bring to light two female photographers who each explored the situation of women in the 1970s: Penelope Slinger, whose surreal collages blend her body with a deserted country mansion (the messy, eerie juxtapositions standing out over the neat, obvious ones); and Christine Voge, whose intimate documentation focuses on daily life in the first women’s refuge in the UK—including children, and registering both troubled, confrontational gazes and moments of carefree abandon.

Installation view of Hannah Starkey’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photo Linda Nylind

Voge also figures in Hannah Starkey’s more daring arrangement investigating gender and visual culture, sifted from the Arts Council’s under-appreciated photography collection. Voge’s image of a child crying, contorting her body away from the prying lens, is matched with images by other photographers of children’s bodies arrested in strange positions. Starkey’s battle cry for intelligent images, and tender, inquisitive representations of people and their situations, is a familiar one, but feels fresh, as social reportage and fine art are all mixed up in a display ordered by motif as much as intellectual inquiry.

Installation view of Jane and Louise Wilson’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photograph: Linda Nylind

At the Hayward, Richard Wentworth’s messy scrapbook approach to curating and collecting offers the clearest challenge to the white-walled status quo—and is furthest removed from Sugimoto’s Barbican stockpile. “True to the experience of being alive,” he calls it. Just as the makeshift urban assemblages he chances upon in his ongoing photographic series Making Do and Getting By make you look at street scenes twice, here his arrangements alter the way you look at and behave in a gallery: peer up at book covers, facedown on a glass shelf above; bend down and assume almost the same pose as the female cleaners at the feet of officers in photojournalist Bert Hardy’s record of Downing Street in the grip of WWII—and later, as the soldiers kneeling in the sand in Robert Capa’s blurred documents of the D-day landings.

Looking at Capa’s grainy records, which very nearly didn’t survive, you realize one more reason why “the collecting gene,” as Parr terms it, is so engrained in photographers: to collect is to keep things safe, and photography is so very fragile.

Isabel Stevens works at Sight & Sound and writes on film and photography.

Magnificent Obsessions at the Barbican runs through May 24.

History is Now at the Hayward Gallery runs through April 26.

The post London Exhibitions of Photographers’ Collections appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Review: On London Exhibitions of Photographers’ Collections

by Isabel Stevens

Installation view of Simon Fujiwara’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photograph: Linda Nylind

Two exhibitions in London currently highlight collections of art and oddities that belong to some of the most prominent photographers today. Magnificent Obsessions at the Barbican presents the objects belonging to photographers such as Martin Parr and Hiroshi Sugimoto while the Hayward Gallery’s History is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain has four photographers—Hannah Starkey, Jane and Louise Wilson, and Richard Wentworth—acting as curators of various section. Writer Isabel Stevens examines the theme. This review first appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

“You know how a collector is. He gets excessively conscious of a certain object and falls in love with it and then pursues it…And it’s compulsive and you can hardly stop.” –Walker Evans

The obsessive hunt of the collector is an activity and state of mind the photographer knows all too well. Walker Evans, who walked away with many of the flotsam, signs, and tools he gathered with his lens, and who was a life-long collector of picture postcards, regarded the two pursuits as “almost the same thing.” For isn’t the tendency to collect deepest ingrained in photographers and the nature of their medium? Consider conceptually-inclined artists with one-track minds fixed on subjects such as water towers (Bernd and Hilla Becher); photo-collagists from Hannah Höch to John Stezaker; archive rummagers such as Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel; Alec Soth and his shot lists of subjects to scavenge (suitcases, snow, unusually tall people); and, of course, Susan Sontag’s famous statements “To photograph is to appropriate the thing being photographed” and “to collect photographs is to collect the world.” When, in 1920, Eugène Atget remarked that “the collection has today almost completely disappeared,” he wasn’t just referring to his negatives, but the content of them—the curious façades, statues, fountains, and street vendors of old Paris.

Martin Parr, Venice, Italy, 2005 © Martin Parr/ Magnum Photos/ Rocket Gallery. From Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

Two exhibitions in London currently highlight photographers’ foraging acuities and their collecting habits. At the Barbican, Magnificent Obsessions presents artists’ personal collections, including Martin Parr and Hiroshi Sugimoto. Meanwhile the Hayward Gallery’s History is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain has four photographers— Hannah Starkey, Jane and Louise Wilson, and Richard Wentworth—acting as curators refracting moments and themes in Britain’s seventy-year postwar history through art works, artifacts, and archival documents.

These exhibition strategies are far from a new phenomenon. Sugimoto’s collection has been aired before (just not in the UK), and Parrworld, at the Jeu de Paume in 2009, showed off many of the photographer’s acquisitions, ranging from the bizarre (Saddam Hussein watches) to the banal (boring postcards). Similarly, both the Barbican and Hayward exhibitions have a Wunderkammer feel to them: vitrines and piles of unexpected, disparate objects and images.

50 Glass Eyes, 1811–88 Collection of Hiroshi Sugimoto, from Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

While exhibitions generally present finished artworks and reference influences, an artist’s selection opens up the creative process and offers a view of sources of inspiration. In this case, showing a collection or curating a show becomes an act of self-portraiture, or even advocacy. Where an artist takes the role of a celebrity curator, he or she can introduce unknown artists to wider audiences in the ways that regular curators often can’t. In the case of photography, the opportunity it provides for rediscovery is particularly pertinent as the medium was looked down upon for so much of the twentieth century, and, as a result, offers historical gaps to fill. Martin Parr’s championing of photographers such as Tony Ray-Jones stands in a long tradition, reaching back to Berenice Abbott’s salvaging of Eugène Atget’s work.

Flying postcard, 1960–90. Collection of Martin Parr © Martin Parr Collection/ Magnum Photos/ Rocket Gallery. From Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

At the Barbican, Parr’s Soviet space-dog memorabilia isn’t nearly as fascinating as the early, pre–World War II postcards on show, which commemorate idiosyncratic sights and occasions such as giant bonfires and hailstones, car crashes and factory-smoke-filled landscapes that resemble miniature, monochrome Turner paintings. Beyond their salacious and strange everyday obsessions, which chime with Parr’s own, Parr also uncovers their artistry, particularly the elaborate, morbid collages of W. Gothard, which record and pay tribute to disasters.

While Parr’s collection offers the thrill of discovery, Sugimoto’s hardly raises an eyebrow. The aged optical curios in glass cabinets and ordered anatomical drawings lined on the wall, which at close quarters look almost abstract, are exactly what we might expect a photographer fascinated with perception, time, and surrealism to be attracted to. Ditto the most entrancing segment of this studied and austere presentation, Sugimoto’s fossils of sea creatures that call to mind the cyanotypes of Anna Atkins, who collected botanical specimens to preserve. Sadly, the William Henry Fox Talbot images from his collection aren’t on show. Those eager to know what other photographic treasures lie in his possession will have to wait for Sugimoto’s museum, the Odawara Art Foundation, scheduled to open in spring 2016. His sleek art complex is an enticing proposition, but you do hope that there’s also a future for dusty old museums.

Just as Sugimoto’s assemblage at the Barbican is too much of a scattershot self-portrait, so too is Jane and Louise Wilson’s display at the Hayward. It explores social unrest in British history, but too often through the prism of their own work. However, it does bring to light two female photographers who each explored the situation of women in the 1970s: Penelope Slinger, whose surreal collages blend her body with a deserted country mansion (the messy, eerie juxtapositions standing out over the neat, obvious ones); and Christine Voge, whose intimate documentation focuses on daily life in the first women’s refuge in the UK—including children, and registering both troubled, confrontational gazes and moments of carefree abandon.

Installation view of Hannah Starkey’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photo Linda Nylind

Voge also figures in Hannah Starkey’s more daring arrangement investigating gender and visual culture, sifted from the Arts Council’s under-appreciated photography collection. Voge’s image of a child crying, contorting her body away from the prying lens, is matched with images by other photographers of children’s bodies arrested in strange positions. Starkey’s battle cry for intelligent images, and tender, inquisitive representations of people and their situations, is a familiar one, but feels fresh, as social reportage and fine art are all mixed up in a display ordered by motif as much as intellectual inquiry.

Installation view of Jane and Louise Wilson’s curated section at Hayward Gallery, History Is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain. Photograph: Linda Nylind

At the Hayward, Richard Wentworth’s messy scrapbook approach to curating and collecting offers the clearest challenge to the white-walled status quo—and is furthest removed from Sugimoto’s Barbican stockpile. “True to the experience of being alive,” he calls it. Just as the makeshift urban assemblages he chances upon in his ongoing photographic series Making Do and Getting By make you look at street scenes twice, here his arrangements alter the way you look at and behave in a gallery: peer up at book covers, facedown on a glass shelf above; bend down and assume almost the same pose as the female cleaners at the feet of officers in photojournalist Bert Hardy’s record of Downing Street in the grip of WWII—and later, as the soldiers kneeling in the sand in Robert Capa’s blurred documents of the D-day landings.

Looking at Capa’s grainy records, which very nearly didn’t survive, you realize one more reason why “the collecting gene,” as Parr terms it, is so engrained in photographers: to collect is to keep things safe, and photography is so very fragile.

Isabel Stevens works at Sight & Sound and writes on film and photography.

Magnificent Obsessions at the Barbican runs through May 24.

History is Now at the Hayward Gallery runs through April 26.

The post Review: On London Exhibitions of Photographers’ Collections appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 1, 2015

Lynne Tillman on Brush Fires in the Social Landscape

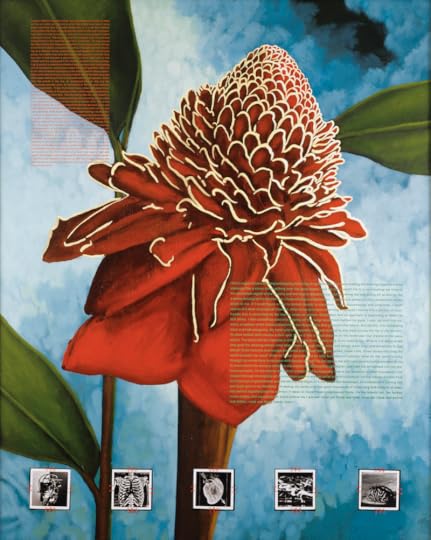

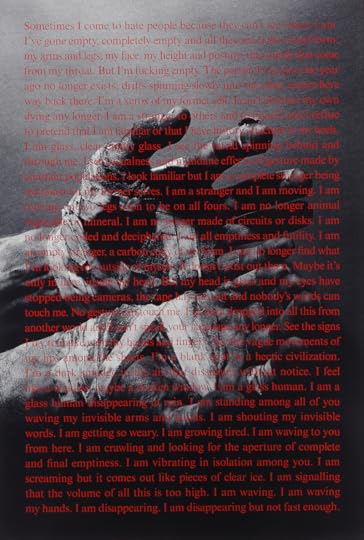

David Wojnarowicz, Seeds of Industry II, 1988–89

For the new twentieth-anniversary edition of Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, Aperture invited writers and artists to examine the lasting effects of the work and life of David Wojnarowicz. In this excerpt, writer Lynne Tillman reflects on discovering his work, its contemporary interpretations, and his influence on future generations of artists and writers. This excerpt appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

I’m almost certain Kiki Smith introduced me to David Wojnarowicz. I knew about him, his Rimbaud pictures were pasted on walls and stenciled on sidewalks in the East Village. In my mind’s eye, we’re on a sidewalk, maybe on Houston Street; it’s windy, late fall or early winter, and Wojnarowicz is standing behind Kiki. Consciousness superimposes scenes from the present onto the past, or mixes one distant moment with another; memory has forever been photo-shopped. The technology replicates a natural, involuntary default position in the brain, or a human inclination to fuse events. Photo-shopping can deliberately distort or corrupt historical events; human memory is distorted, first, by subjectivity or point of view, then by the passage of time. Was it a dream, a photograph, did I hear the story, did it actually happen? The clock marks seconds, minutes, hours; the calendar, days, months, and years—these human productions divide now from then, and from the future. The unconscious doesn’t obey time, which also confuses memory, and can make days feel endless or too short. Maybe that’s why people invented what Shakespeare, in Richard II, called time’s “numb’ring clock.” I picture Wojnarowicz with his head down; he was tall, I’m short, which would influence how I saw him, and he me. He might have been looking sideways, and appeared shy or elusive. He had a long face, uneven features, and a smoker’s raspy voice. Other adjectives pop up: gangly, rawboned, intense, weirdly funny, restless, sad, sensitive, vulnerable. But this isn’t a portrait of the artist as a young man. Wojnarowicz’s portrait was, in a profound sense, shot by his time.

David Wojnarowicz, Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone, 1988–89

Wojnarowicz knew he was homosexual before the word gay took its place; he came of age with Stonewall and the movement it incited—gay liberation. Then, an individual’s “coming out” was a revolution of great and intimate proportions, a public and private declaration of startling consequence. Wojnarowicz’s art and writing were born and nurtured before, but fomented in and exploded during, the AIDS crisis. Artists and writers are often very different from their work. They work with and against their education, fear, anxiety, hope, angst, values, to build characters, find words or concepts, build structures or images that defeat or deny these things their power, or sometimes to venerate them. The gap between person and artist can be inexplicable, but people, including artists, often conflate the two. Art historians and critics might merge them, judging the work by the person or the person by the work. But history judges what history also produces.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Eye with Ant), 1988–89

What is now called “history” was Wojnarowicz’s lifetime, his present, which insidiously produced what mattered to him. His best talents were made furious use of during the 1980s until his death in 1992. His impassioned writing became a powerful voice of the AIDS epidemic, his blunt-force-trauma art a singular and passionate face. Wojnarowicz’s work, I believe, even without the exigent circumstances, or influence, of AIDS, would have been knife-sharp and arresting. Without the consequences of AIDS, though, there would have been time for him to mature as a person and an artist, to have a future. Consequence and influence share territory. They can’t be predicted or entirely comprehended, since the two radiate from a myriad of sources and will settle without foreknowledge and, usually, without acknowledgment. Mostly, people don’t get to choose an influence, unless they’re conscious adults, and by then the wish to be influenced—to absorb—means that a person has been, in a sense, prepared. The preparation for influence develops independently of consciousness, while simultaneously creating it. In the 1980s, being infected by HIV and developing AIDS was an unchosen, horrific fate, fatal. People were very frightened, and felt hopeless. Not every artist or writer responded as Wojnarowicz did. His responses were unique, thoroughly felt, and driven by an urgent necessity. In his time, his work was extraordinarily moving—it stunned. It will never be experienced again as it was then, in that very dark moment. Contemporary artists sympathetic to Wojnarowicz’s work, who say his work influenced them, find meanings in it that have been profoundly useful to them. They are a diverse group, their work dissimilar in appearance from his, and from each other’s. Some of the artists might say: “His work gave me courage.” Or “Wojnarowicz was a courageous artist.” Courage in an artist or writer is different from the courage of firefighters, who rescue people and risk their own lives. Artistic courage might be conceptualized as an internal drama about overcoming rules or inhibitions, dicta of all kinds, the art a manifestation or result of a multitude of processes. Art won’t save people from burning buildings, but not all risks are the same or equal, and they shouldn’t be measured by one ruler. During his time, Wojnarowicz’s work might have sprung from rage, fear, and compassion or been inspired by them, his approach or sense of form enabled by and called to address them. An abiding necessity to save himself and others arose. A cruel disease had suddenly and quickly made helpless victims of an already stigmatized group. The tragic waste of the disease, and also the injustice of stigma, probably urged Wojnarowicz toward a kind of overcoming. To have his life be meaningful, he would keep living by doing his work. He would rage on.

David Wojnarowicz, I Feel a Vague Nausea, 1990

Artists are not mythical beings or romantic heroes. In their chosen fields and in a certain time, they make aesthetic, intellectual, conceptual decisions; they may react variously to social and political questions and to concerns central to their mediums and practices. As artists, they evolve from and are influenced by not just other artists, but also their own psychology, religion, race, economic background, and more. Influence is everywhere, and they take chances, too. Everyone who lives sometimes does, everyone sometimes has to. That curious notion of character also comes into play: existentially, artists and writers become who they are, and make what they do, in the moment they act.

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York (on subway), 1978–79

Sometimes an artist’s work opens up a space. I’ll call it a “mental space,” a space for themselves and others, where random thoughts, images, ideas germinate and occur—these might have consequence. When that happens, when an artist’s choices do that, an artist might be called courageous. Something that was broken got metaphorically fixed; something that was blocked breaks through. A solution arrives to a problem no one ever mentioned. Some will notice that in the work, and it helps them. Shannon Ebner, Wade Guyton, Henrik Olesen, Adam Putnam, Emily Roysdon, Zoe Strauss, and Wolfgang Tillmans, among many other artists who mention Wojnarowicz’s influence on them, probably recognized, reacted to, or internalized something they gleaned in his work; usually they mediate it so thoroughly, a viewer wouldn’t spy it. Or, because it was an idea for them, an idea, say, without materiality, it never materializes in their work. Harold Bloom theorized that influence produced anxiety and troubled poets who turned to writing poetry after reading other poets. Bloom studied the Romantics, but wrote The Anxiety of Influence (1973) under the sign of Modernism. Ezra Pound’s call was “make it new” (though Dante shaped his poetics). Influence from that purview was a staining or tainting, an inhibiting or retarding, of an artist’s originality. To rejig the concept of influence as an actor-agent in the work of artists and writers, to make influence newer, the computer must be restarted with another program. Influence occurs, in this register, because an artist perceives in another’s work a space, or opening. Maybe it’s whimsical, inchoate, wishful, a fragment of a fragment. Rarely a direct taking, more like the flow of information. Rarely “stealing,” as Picasso said great artists do rather than borrowing. Instead, something is shown, intimated or associated, noticed, and it feels true or right or necessary. A diffusion is transmitted and received. Influence reconceived would be a heuristic device, an emboldening or an encouragement.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Sometimes I come to hate people), 1992. All works © the Estate of David Wojnarowicz, Courtesy P.P.O.W Gallery, New York

One artist can and often does encourage another. One artist’s courage in making, or what another perceives as such, becomes another’s space to take up. Courage and encourage have a similar root: in Latin, cor means heart. To have a heart is to give heart. To give heart is to embrace and charge others with a kind of love.

Lynne Tillman is the author of five novels, three collections of short stories, one collection of essays and two other nonfiction books. She collaborates often with artists and writes regularly on culture, and her fiction is anthologized widely.

Tap here to find Brush Fires in the Social Landscape on the Aperture Foundation website.

The post Lynne Tillman on Brush Fires in the Social Landscape appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 28, 2015

Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Inside Issue 6 our readers can find:

● An excerpt from the new edition of Brush Fires in the Social Landscape by Lynne Tillman

● A first look at the upcoming Summer 2015 “Tokyo” Issue of Aperture magazine

● An interview from The PhotoBook Review on collecting Japanese photobooks

● A 1990 interview between David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin

● A review of two exhibitions in London about photographers’ collections

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free: select articles later appear here on the Aperture Blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Nakahira’s Circulation

By Matthew S. Witkovsky

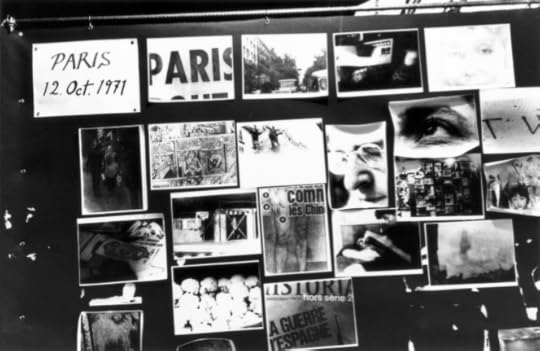

A mythical figure in the story of Japanese photography, Takuma Nakahira is a founder of Provoke (Purovoku), the short-lived experimental magazine that featured photographers like Daido Moriyama working in the are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus) style of the late 1960s. His extensive writings explore photography’s capacity to probe the shape-shifting contours of postwar Japanese society. Nakahira destroyed his own negatives in 1973, and he suffered a traumatic loss of memory in 1977, events that have contributed to his relative obscurity outside of Japan. In the Summer 2015 issue of Aperture magazine, “Tokyo,” which will be available next month, we offer two perspectives on this vital figure: scholar Franz Prichard introduces Nakahira as a photographer and writer; and curator Matthew S. Witkovksy, who is currently planning a major exhibition on Provoke-era photography, unpacks Nakahira’s landmark photo-installation Circulation, staged at the 1971 Paris Biennale. Here, we feature an excerpt from Witkovsky’s article.

This excerpt first appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

On the afternoon of September 28, 1971, when Japanese critic and photographer Takuma Nakahira set foot (several days late) in the seventh Paris Biennale, he felt nothing so much as “hollowness” and “despair.” Reporting these sensations for the Japanese weekly Asahi Journal that December, Nakahira explained his dissatisfaction with the state of contemporary art and, indeed, with his own activities as a creator and commentator on art. The laudable artworks on view mostly attacked a social system from which their makers pretended to keep some distance; Nakahira observed that, in fact, this art could only be the very face of such a system, which created a sort of play area for artists to vent futile opposition to the forces of capital flow and authoritarian control. Those forces had a vested interest in shoring up authorial ego when, in fact, it was the art goods and their exchange value that really mattered: individuality was a commodity construct. Yet his own contribution to the Paris Biennale, which he described at length for Asahi Journal and again for the photography magazine Asahi Camera the following February, allowed him guarded hope that art and art criticism could still have a purpose in the world. What was it about Circulation: Date, Place, Events, Nakahira’s piece for the 1971 Biennale, that gave grounds for optimism?

Takuma Nakahira, who got his start in photography and criticism only around 1965, had by the end of that decade already become one of the most influential figures in contemporary culture in Japan. Nakahira’s incisive writing cut apart standing views in literature, film, politics, and especially photography, and he published both articles and photographs at a feverish rate. He wanted a relation between these two activities that could come closer than complementarity— a joint force of action, perhaps. The intended effect of that joint action might be “illumination,” to quote a word favored by prewar German critic and theorist Walter Benjamin, whose essays were first anthologized in English as well as in Japanese in the late 1960s: searing, flashbulb-like insights afforded by a photograph or fragmentary phrases. Provoke: Provocative Materials for Thought—the short-lived photography journal that Nakahira helped to found, which blazed its trail across the Tokyo cultural scene in those years—took its name from such intertwined desires. Writing and photography should illuminate the world, explosively, and they should set each other ablaze as well. Nakahira’s epochal photobook, For a Language to Come (1970), pushed even more insistently at an overhaul of word-image relations. Yet Nakahira remained dissatisfied and, worse, fatigued by his efforts to develop a productive analysis of contemporary culture.

“Has Photography Been Able to Provoke Language?” Nakahira asked in March 1970, around eight months before his book appeared. “Only through human use can a language be given life,” he asserted, for without a subjective viewpoint, language exists as mere symbols and generalities. But to shake a language awake, to deploy it, is also to risk damaging one’s psyche: “This kind of ‘exploding language’ is a language that has been fiercely lived here and now by a single person.” Just such “fiercely lived” insights were what Nakahira sought to produce and circulate, operating calculatedly on the verge of madness. (Prichard has translated that essay and others in the recent reprint of For a Language to Come, as well as in Circulation: Date, Place, Events; issued by the Tokyo house Osiris, both books also have keenly written afterwords by cultural critic Akihito Yasumi.)

In the view of many who have encountered it then or since, For a Language to Come eminently fulfilled Nakahira’s hope for pictures that would give concrete meaning to words while threatening language overall as a system of convention and control. The word tree is general, but a photograph of any tree will be specific, Nakahira argued, with catlike stealth, before pouncing on the surprise conclusion: that close comparison of a single tree in image and word “causes the concept and meaning of tree to disintegrate.” How? Through sentences that leap and dart, and pictures that careen between heavy grays and blinding whites; through sequences of haunting images that overtake the reader, as if the setting for Nakahira’s photographs—the city of Tokyo—were a mental space in which one staggered from desire to trauma, a solitary ego shattered by passion and rage.

The effort of making For a Language to Come left Nakahira spent and temporarily uninterested in further photographic projects. One year later, the commissioner for Japanese entries in the Paris Biennale, fellow Provoke veteran Takahiko Okada, convinced him to travel there only after much debate, “at least to do some sightseeing,” as Nakahira disarmingly recalled upon his return. Yet the very fact of Nakahira’s repeated and extensive commentary on his Paris piece suggests the sense of renewal it brought him. Circulation was not only the title of this piece but also its ambition and modus operandi. More literally than did For a Language to Come, the fleeting work raced with an illuminating flash of brilliance through the early 1970s art scene.

Circulation was, in essence, a performance piece in which photographs were the engine of the performance rather than a record of it. This quality is the greatest guarantor of the work’s uniqueness in photographic terms, but there are other reasons to reassess its meanings today. (New prints from the original negatives were shown in New York in 2012 and feature currently in an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.) Rather than send existing pictures to Paris, Nakahira wished to create something “live” during the run of the exhibition. He would hang only pictures taken and printed that very day, making a photo-diary of his Parisian experiences that would cover his Biennale wall in stages. By circulation Nakahira meant his own movements around Paris, the movement of his pictures from darkroom to display, and the perambulation past his evolving piece by visitors to the Biennale, whom Nakahira photographed for this installation as well.

All photographs: Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1971, from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events

© 1971 Takuma Nakahira and courtesy Osiris, Tokyo, and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

The prints themselves would be “mere remnants” of these circulatory patterns. Nakahira’s description of his procedure, from the February 1972 article in Asahi Camera, suggests a determined resistance to fixity: “To put it concretely, I set myself to photograph, develop, and exhibit nothing but the Paris that I was living and experiencing. My project … was born from this motivation. Every day I would go out into the streets of Paris from my hotel. I would watch television, read newspapers and magazines, watch the people passing by, look at other artists’ works at the Biennale venue, and watch the people there looking at these works. I would capture all of these things on film, develop them the same day, make enlargements, and put them up for display that evening, often with the photographic prints still wet from the washing process.”

Aperture magazine #219, “Tokyo,” (Summer 2015) is coming soon. Tap here to subscribe!

The post Nakahira’s Circulation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers