Aperture's Blog, page 164

March 5, 2015

The 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize Short List

We’re pleased to announce the four finalists for the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an international photography competition whose goal is to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, Aperture’s editorial and limited-edition print staff reviewed more than seven hundred portfolios. Our challenge was to select one winner and three honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. Of the following exceptional finalists, one will be selected as the winner of the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize, receiving a cash prize and an exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York:

Lisa Elmaleh

Heikki Kaski

Drew Nikonowicz

Laurence Rasti

The winner of the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced in April. The finalists’ portfolios and statements will be available to view on aperture.org. In the meantime, view past Portfolio Prize winners.

The post The 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize Short List appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Announcing the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize Short List

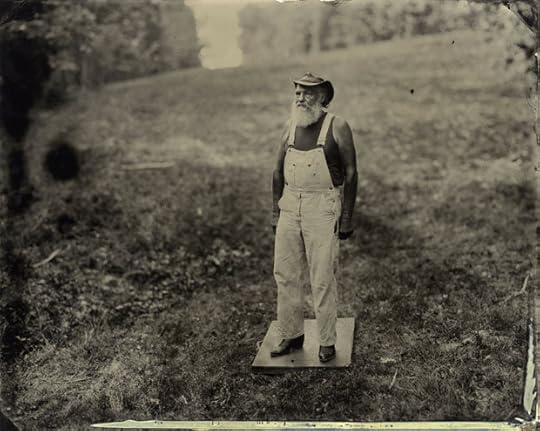

Lisa Elmaleh, Dennis Rhodes, Hawesville, Kentucky, 2013; from the series American Folk

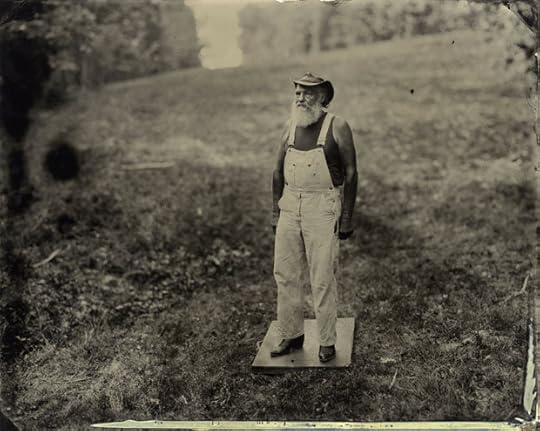

Heikki Kaski, from the series Tranquillity, 2014

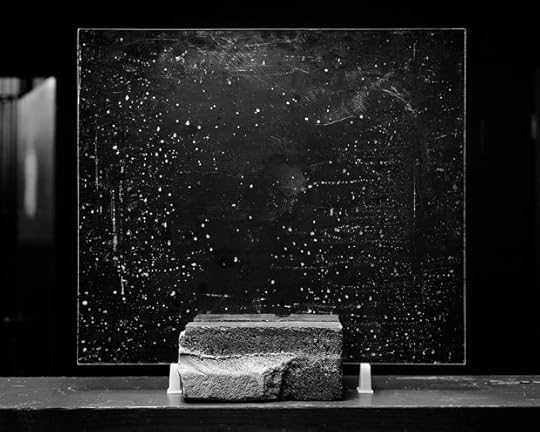

Drew Nikonowicz, 2014-10-13 03:43:24 PM 38°56'45.73" N 092°19'33.29" W 0773, 2014; from the series This World and Others Like It

Laurence Rasti, from the series There Are No Homosexuals in Iran, 2014

We’re pleased to announce the four finalists for the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an international photography competition whose goal is to identify trends in contemporary photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, Aperture’s editorial and limited-edition print staff reviewed more than seven hundred portfolios. Our challenge was to select one winner and three honorable mentions from this overwhelming response. Of the following exceptional finalists, one will be selected as the winner of the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize, receiving a cash prize and an exhibition at Aperture Gallery in New York:

Lisa Elmaleh

Heikki Kaski

Drew Nikonowicz

Laurence Rasti

The winner of the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize will be announced in April. The finalists’ portfolios and statements will be available to view on aperture.org. In the meantime, view past Portfolio Prize winners.

The post Announcing the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize Short List appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 4, 2015

Drew Sawyer on Thomas Demand

Thomas Demand, Bloom, 2014. All photographs © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Two exhibitions, at Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Matthew Marks Gallery’s Los Angeles location, feature German-born photographer Thomas Demand, who lives and works in Los Angeles. Demand creates models which he then photographs: At Matthew Marks, he debuts new photographs, while at LACMA he shows a work of stop-motion animation. Drew Sawyer, the Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, considers the effect the artist’s new relationship to the West Coast has on this body of images.

Thomas Demand’s current multiple exhibitions in Los Angeles, where the German-born artist has lived since 2010, serve as evidence of a subsequent shift in his practice. Since the early 1990s, Demand has produced photographs of seemingly ordinary places and objects: paper-strewn offices, sterile hallways, and modernist staircases. He typically begins with an existing image of political or cultural relevance culled from archives or the media that he then translates into a three-dimensional paper model. He came to this circuitous and labor-intensive method while attending the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, where he trained as a sculptor with Fritz Schwegler. Though he did not study with Bernd and Hilla Becher, he clearly shares their concern for documenting banal-looking places and structures with deep historical significance.

Atelier, 2014

In an exhibition of new works at both of Matthew Marks’s West Hollywood galleries, Demand presents large-scale photographs of paper models based on photographs. Although the form feels familiar, this new series relates to recent events or art and architectural history, whereas his prior show, in New York, in 2013 to 2014, presented pictures made from casual cellphone snaps. The current exhibition includes images charged with more political and cultural commentary: Backyard (2014) is drawn from a New York Times photograph of Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s home in Cambridge. A thirteen-foot-long photograph, Bloom (2014), focuses on cherry blossoms in the background of the same backyard, further removing the image from its disquieting source material. These photographs are juxtaposed with two images modeled after Matisse’s studio, where added colorful paper scraps on the herringbone floor reference the modernist master’s late cutouts—playfully referencing Demand’s own paper constructions. Demand’s exclusion of human figures—he removed Tsarnaev’s wife from the source photograph in Backyard as well as a wheelchair-bound Matisse in Atelier (2014)—recalls forensic photography, a genre of images from which he often draws. As with his previous photographs, both bodies of work reflect on the circulation of images and the loss of context in the construction of historical memory.

Sidegate, 2014

Other photographs on view push his practice in new conceptual directions. He reimagines the Santa Monica balcony belonging to mob boss and fugitive Whitey Bulger and a gated entrance to the Southern California home of Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, the writer and producer behind the 2012 anti-Islamic video Muslim Innocence. While drawn from the news, these works are not based on existing images. Rather, Demand’s proximity to the locations allowed him to carry out his own espionage, and the images allegorize the themes of privacy and transparency by focusing on visual barriers: a large solid gate or a barred balcony in front of sliding glass doors with drawn curtains. Without preexisting images, we are offered even less access to these places, and even Demand’s own experience of them does not offer much information.

At Matthew Marks’s second space, Demand shows new photographs of architectural models by the Tokyo-based architectural firm SANAA. These images continue his series of models of unrealized structures by the mid-century Californian architect John Lauder, which Demand carried out while a visiting scholar at the Getty Research Institute in 2010. The photographs represent the first time the artist has photographed models he did not build, and push his exploration of representation and abstraction even further.

Pacific Sun, 2012, production still

Demand’s recent film Pacific Sun, a one-hundred-second stop-motion animation based on security footage from a cruise ship dining room during a tumultuous storm off the coast of New Zealand, is also currently on view, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Demand also began the film at the Getty Research Institute, where he and a team of assistants meticulously recreated, in 2,400 photographs of paper models, the violent movement of hundreds of objects from one side of the cafeteria to the other. The result is one of Demand’s most ambitious works to date. His first film Tunnel, from 1999, was a track shot of a thirty-two-meter-long cardboard model of an underpass that evokes the 1997 death of Princess Diana of Wales by car crash. Both films, like his photographs related to the Boston Marathon bomber and the fugitive mob boss, explore our contemporary moment of insecurity and surveillance via the media. In a culture with an excess of images that serve as either means of power or distraction, how does one wrest control of their incessant flow? Demand’s recent photographs and films may not provide the answers, but they are asking the right questions.

Pacific Sun at LACMA runs through April 12.

Thomas Demand at Matthew Marks runs through April 4.

The post Drew Sawyer on Thomas Demand appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 3, 2015

Inside the Spring Party with Penelope Umbrico

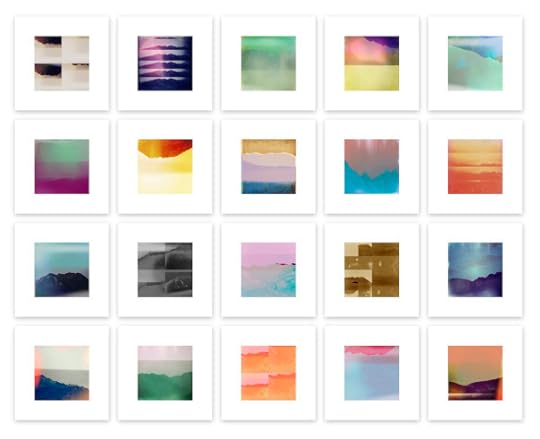

Detail of 350 Mountains (with Smartphone Camera App Filters) for Aperture Spring Party Edition, 2015, from Range: of Aperture’s Masters of Photography

On Friday, April 17, Aperture Foundation will hold its first annual Spring Party. For this inaugural event, Aperture has teamed up with artist Penelope Umbrico to offer each party attendee a unique, signed photograph from Umbrico’s Moving Mountains series. Each print grants access to the Spring Party, which will feature an open bar, hors-d’oeuvres, music, and celebration. Umbrico, whose work has been shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1, New York, frequently engages with the saturation of images in a digitized word, sampling from catalogs, brochures, even Flickr. Online editor Alexandra Pechman asked Umbrico about the inspiration for the series, its recent presentation at Aperture’s gallery, and the changing world of contemporary photography. This article also appears in Issue 2 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Aperture Foundation: Your series Moving Mountains (1850–2012) began a few years ago when you were commissioned by Aperture to contribute to Aperture Remix, an exhibition for which photographers were invited to choose an Aperture publication and to pay it artistic homage. Why did you choose the Aperture Masters of Photography Series?

PU: I was interested in a converging the two most disparate things, the stability of a masterly photographic practice with the instability of smartphone camera technology.

AF: What attracted you to the mountain photographs within those books?

PU: I had been suddenly seeing images of mountains everywhere (on magazine covers, in galleries, advertisements, etc.), and thinking about the mountain as a symbol of stability, I had a quasi-theory that the more unstable our definitions of photography are, the more images of mountains appear in the photographs of photographers who have something at stake in the medium. So I looked for mountains in the Masters‘ photographs. I liked the parallel relationship of stable object to master photographer: the sense of integrity, history, and timelessness in both.

AF: You rephotographed the Masters photographs with an iPhone using various camera apps and their photo filters, rendering classic works by the likes of Edward Weston, Wynn Bullock, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Manuel Álvarez Bravo as almost entirely different images. What was your thought process behind this?

PU: If I was going to look at the mountains of master photographers, it made sense to rephotograph them with the least stable of photographic technologies—the smartphone camera app. I love that when the camera is pointing down at the books, the gravity sensor of the iPhone can flip a mountain sideways or upside down. This disorienting effect blends with hallucinogenic colors of the camera app filters, where photo grain, dot-screen, pixel, and screen resolution collide in undulating moirés. I was particularly interested in light-leak filters—nostalgic representations of the failures of analog photography, simulated with no light at all, in the vacuum of an iPhone.

AF: When first presented at Aperture Gallery, the photographs played off one another in a cohesive, colorful grid. Did you have an idea of how you wanted the images to look together or did the idea develop as you went along?

PU: I made about six thousand iPhone images in the course of a couple months. The fact that I could make so many, so quickly heightened the contrast between thinking about the inherent multiplicity of analog photography historically, and its limits in relation to current replication and distribution systems. The film/paper photograph becomes quite singular beside digital files and social media. I wanted the installation at Aperture to speak to this—I chose images from the six thousand-plus that would speak to each other as formally contingent parts of a whole. Not all the resulting images work this way: some work best in groups, and some are better on their own or in pairs.

AF: What was the most surprising thing you found going through the original images?

PU: The biggest surprise for me though was that, of the four women represented in the Masters of Photography series, none had images of mountains in their photographs. This solidified an idea about the symbolism of the mountain, and the fact that I, a present-day female, was rephotographing mountain images by male photographers only, by circumstance and not by choice, seemed to fit the symmetrically oppositional logic I had set up. I wrote a text piece that to accompany the work called Masters, Mountains, Ranges, and Rangers, —a progression through various dictionary definitions of those words that points to opposing ideas for each of those words, and questions their assumed cultural values. It’s in my e-book, Moving Mountains, which Aperture produced, and also in the new small book, Range (Aperture, 2014).

AF: Moving Mountains comments on the changing nature of contemporary photography, and was in fact, our first artist ebook when released in 2013 for the exhibition. Now the prints will be sold through Artsy online…and, of course, we’re previewing all this on a brand-new app! What does the pace of digital media today mean to you as an artist?

PU: It’s exciting for me because it’s my material, and therefore these changing technologies become my subject—the more there is, the more I have to work with!

AF: The purchase of one of the photographs gains entry to our first-ever Spring Party, which seems fitting for photographs that celebrate two centuries of photography. What do you hope the effect will be on those who live with this work?

PU: I’d like to think that the issues I address in a body of work are embedded in that work. For Range, (or Moving Mountains as it was called in for the first installation), the register of time, as you say, is quite literally in the work. But also each small piece contains a concentration of a dialogue between the old and the new, distance and proximity, limited and unlimited, the singular and the multiple, the fixed and the moving, the rare and the common, master and disciple, and the master and the copy.

The post Inside the Spring Party with Penelope Umbrico appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 27, 2015

Doug Dubois – My Last Day at Seventeen

Support My Last Day at Seventeen on Kickstarter.

Doug DuBois first went to Ireland at the invitation of Sirius Arts Centre in 2009. What began as a month-long residency grew into a five-year project about youth, Ireland, and an exceptional group of young people from a few blocks of a housing estate in Russell Heights. The resulting photographs are an exploration into the promise and adventure of childhood with an eye toward its fragility and inevitable loss.

DuBois gained entry to the community when two of its residents, Kevin and Eirn (who would later become central subjects of his work), took him to a local hangout spot, opening his eyes “to a world of the not-quite adults, struggling—publicly and privately—through the last moments of their childhood.”

Over the course of many summers, DuBois returned to Russell Heights. People came and left, relationships formed and dissolved, and babies were born. Combining portraits, spontaneous encounters, and collaborative performances, the images of My Last Day at Seventeen exist in a delicate balance between documentary and fiction. A powerful follow-up to DuBois’ acclaimed first book, All the Days and Nights, this project provides an incisive examination of the uncertainties of growing up in Ireland today, while highlighting the unique relationship sustained between artist and subject.

If this Kickstarter campaign is successful, in fall 2015, the New York-based not-for-profit photography publisher Aperture Foundation will publish the photobook My Last Day at Seventeen. The book incorporates elements of a graphic novel, with stories from the community illustrated by Patrick Lynch.

Along with the photobook, Aperture Foundation hopes to also publish a unique “community edition,” produced especially for the individuals featured in the book, as a way to acknowledge the individual value of members in the community and their integral roles in the making of the project.

The post Doug Dubois – My Last Day at Seventeen appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Q&A: Peter Barberie on Paul Strand

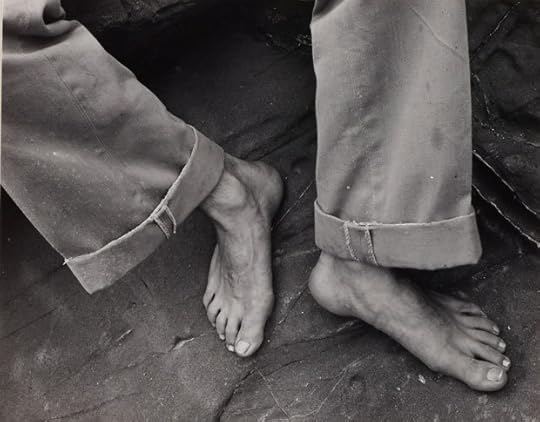

Young Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France,1951 © 2014 Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation, Inc.

Last fall a retrospective of Paul Strand’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) featured 250 photographs by the modernist master. Strand helped establish photography as an art form in its own right, experimenting with abstraction, documentary, and filmmaking, from as early as 1910 through the 1970s. Yale University Press published the exhibition catalogue, edited by Peter Barberie, PMA Brodsky Curator of Photographs, while to coincide with the new survey, Aperture republished Aperture Masters of Photography Series: Paul Strand, with a new introduction and texts by Barberie. The Paul Strand Archive at Aperture Foundation works in partnership with the PMA—the home of the Paul Strand Collection—to preserve and promote Strand’s legacy. Online editor Alexandra Pechman spoke with him last fall about the exhibition, which opens at the Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, on March 7. This article first appeared in Issue 1 of the new Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Alexandra Pechman: There are so many thousands of photographs now in the museum’s collection, which, as you talk about in the book give a whole new perspective on the work. What to you is the most interesting aspect of what we couldn’t see about the work before?

Peter Barberie: The place I like to start from is Alfred Stieglitz, who of course is Strand’s great mentor, and who thought in order to understand an artist’s work you have to be able to trace his or her development. Stieglitz of course kept a great body of his work together, and he wanted to show a single artist’s work over time. One thing to say is that it’s a great tribute to that conviction of Stieglitz’s that we’ve assembled examples of Strand’s work from every moment of his career, in one collection.

In terms of what you can see that you couldn’t see before, Strand always insisted on the continuity of his ideas in his work. He insisted on that without really explaining it completely, so it’s always a little enigmatic to see what he meant. But you can, for instance, look at his portraits from 1916 all the way up to the late 1960s and see his ideas about representing individuals.

AP: There’s that quote you mention about [Georgia] O’Keeffe calling him “thick and slow,” as both a compliment and a slight at the same time. Today, that’s probably more on the slight side, given there’s more of an emphasis on speed. Would you say that makes people more inclined or receptive to Strand’s work now, or they should be?

PB: I think we’re at a moment in contemporary art when it seems to me that it’s good to reassess Strand’s later work because a lot of artists are interested in the documentary tradition in photography. A generation ago, Strand’s move away from avant-garde modernism seemed perplexing, at best. And I think today if you think of a figure like Allan Sekula or Susan Meiselas or any number of people, Strand’s turn to a kind of social seeing—that also has a political dimension in that he shows the politics of a place—has a lot of resonance.

AP: Even though at the same time, he never saw his work as photojournalism. How do you reconcile that with his work being a document in that way?

PB: He was clear that his work was not documentary, and, specifically, that it was not photojournalism. He said that making clear his admiration for photojournalism and the high value he placed on it. But it was clear to him that his mode of working was very different than what was required of photojournalism. One way that he put it is that he liked to work slower than that, which was indeed true. If you look back to the 30s and 40s when he was trying to make political art, specifically in his films, one of the painful lessons for him was his approach to working, which he would not let go of because he understood it was integral to his success. He took a long time, both with ideas and with individual pictures, and that’s not really suited to making politicized art.

AP: Then there are also those photographs of his wife, Hazel, taking photographs of him staging the photograph a bit more than one would in a real document.

PB: What’s important about those photographs by Hazel is that he was never secretive about that staging. He saw no reason to be disingenuous about that; he saw it as contradictory to the way he was presenting his work. I think the reception of his work—because we have this go-to idea that we fall back on about “straight” photography, which sometimes gets conflated with how people think of street photography—is that he’s “finding” these moments. But he was really clear that he was making complicated representations of whatever subject he had chosen.

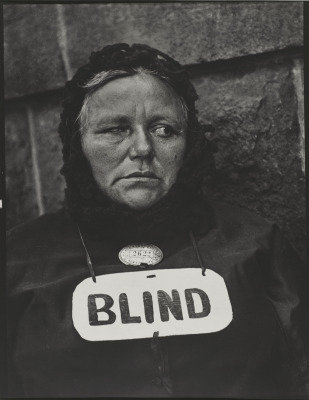

Blind Woman, New York, 1916 © 2014 Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation, Inc.

AP: You mentioned his politics. They’re sublimated in some places and more prominent in others—you talk about in the end of the essay, how it’s kind of convoluted as he’s wavering between leftist optimism, with absolute belief in certain opinions and some conflicting views. What’s your takeaway on his politics?

PB: I have a couple takeaways. Strand was very politically engaged from the 1930s onward. It was clear to him that his political views were distinct from his art. That goes back to what I said earlier: he realized he wasn’t really cut out to be a political artist in the way that John Heartfield was or someone like that. He didn’t want his photographs to be seen as illustrations of his political ideas. A lot of people have a hard time with that, even in reviews of this exhibition. Because he was such a man of the left, people are really stuck on the idea that he was making his photographic projects with a kind of vague yet central political idea. He really wanted to move away from that.

It’s sort of unfortunate because he becomes very reticent about these matters in late interviews in his life. A lot of people have taken that to mean that because of the political climate of the moment, he didn’t really want to talk about it. But I see it as that he wasn’t worried about his politics being discussed: he was worried about his art being discussed as political.

Strand may or may not have been a clear political thinker. When he’s making his art, he’s making it as a reader of literature and poetry. He had strong political commitments that, in my view, were not welded to a certain political party. I think it’s inaccurate to say that Strand is a communist or he’s a socialist. He was on the left and he embraced a wide range of left ideas. That’s about as precise as we can get about his political views. He was absolutely sympathetic to communism, there’s no question, but to say that and leave it at that confuses the matter. I think the way he would have explained it, although he never did, is that his choice of subjects was of course influenced by his worldview and his politics, but his art was about a broader set of issues.

AP: I wonder where in the exhibition, getting this bigger picture of his work, that might be clearer now.

PB: The way I look at his later projects is that he’s more interested in issues of time and history, and certainly the contemporary moment. For instance, in the New England work, I think he’s really interested in American democracy when he makes those pictures, but he’s thinking of American democracy from the beginning until the current moment of the 1940s. His projects in France and Luzzara are very much about the contemporary moment in Europe right after World War II. But in the France work as with New England he looks back to the history of the country, whereas in Luzzara he’s resolutely in the moment of 1953. The heart of these projects, for me, ends up being more about everyday life than about his political views. I don’t want to completely unwind them from each other, because his politics are there, but I don’t think they are the driving force of his ideas.

AP: They are also very poetic. You mentioned that interest as well, in the book, with his use of literature as both in collaborations with Claude Roy and as source material from poets like Whitman– what do you think led to that connection so often? Poetry specifically.

PB: There’s also the folk music traditions of the Hebrides islands [in Scotland] which sparked his interest in going there to some degree. He heard a BBC radio program produced by Alan Lomax about folk music, specifically Gaelic folk songs, in the Hebrides that Lomax had recorded. Strand is interested in the survival of this tradition but he’s much more interested in the broad contemporary moment of these people who live at an extreme edge of Western Europe. So his interest in poetry and music and folk culture is a part of that. In that case, it was an immediate event: he heard the program and wanted to go there.

In other cases, his interest in literature or a certain writer develops for a long time. In Luzzarra in 1953, he finally realizes this long ambition to make a work of art about a single village. This comes from early-twentieth-century American literature, people like Sherwood Anderson or Edgar Lee Masters, where they had fictional works that revolve around the voices of different people in a town. The other thing is that Strand was excited by the aesthetics and the ethics of neorealist cinema and filmmakers in Italy, some of whom were also interested in the same American literary models. So Strand has been thinking for a long time that he’d like to make a work of art about a single village, and then he becomes somewhat close to a group of the neorealists who are making the now celebrated films in Italy. Their aesthetic and sensibility about what they wanted these films to do, which was to speak to a broad and contemporary audience very directly, were perfectly in line with what Strand wanted for his photographs. It’s hard to unravel this question because every time Strand uses a literary model he uses it for different reasons and it merges with what is going on specifically in a given project. But it’s true if you look at his books that many of them do include poetry—in fact, maybe all of them, except Luzzarra, have poems as part of the text.

Collaborating was really important to Strand for his books. He would produce the photographs and then collaborate with a writer who either wrote or selected texts for the book. He saw the two things as very distinct, but I’m sure that he and each writer he worked with influenced each other a lot, in terms of selections of images and texts.

Paul Strand, White Fence, Port Kent, New York, 1916 (negative); 1945 (print). © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

I want to say one thing that goes back to your first question. One thing I love about the exhibition is that you can really trace one of the core things about Strand, which is the importance of place and photography’s special ability to record details of time and place. His later work is all about that, what he would call these “portraits of places” where he spends a lot of time and goes in depth to a very deep representation of places that, I think, he always thought of as modern, even if they don’t always look modern in the way that we use the term. If you go back to the beginning of his work, even as early as his Cubist abstractions in 1916, which he made in Connecticut, you see his attention to the details of place. You see it in those abstractions: you see it in the picture White Fence, Port Kent, which was made that same year. He even said later that the picture was the beginning of New England for him.

Then you see it again when he goes to Maine in the summers of 1927 and ’28. It’s pretty clear that he was making those photographs as individual nature studies. I think his idea was to use a very sophisticated and modern machine, his camera, to make pictures of organic and natural subjects, because those were the two elements that he felt had to be in a photographic work of art at the moment. In interviews many years later, he says that looking at those pictures from Maine from those two summers, he realized that they gave a specificity of place, about the coast of Maine for instance, so that you knew you were looking at things that really described that place specifically. It’s a very slow process for him. He’s always interested in this ability to describe place, but he gradually figures out the layered ways that photography does that. By the time that you get to his photobooks, starting with Time in New England, he has a really sophisticated approach to time and place.

AP: Right, and I did want to briefly talk about Mexico as a turning point as well, which was a place where portraiture comes more into Strand’s work and continues into his New England project.

PB: Mexico is really crucial, but I see it as a transitional moment, as I see all of the ’20s and early ’30s as transitional for Strand. He’s making incredible work where he is figuring out what he wants the camera to do: he is incredibly ambitious for photography as an art form, and he wants it to match the achievements of painting. Mexico is a crucible moment for multiple reasons. Things in his personal life have shifted drastically: he hasn’t broken from Stieglitz, but they have come to a very cordial parting of the ways, his marriage to Rebecca fails, and he’s very upset about the Great Depression. It’s clear from reading his letters that, while he was always a man of the left, this is the historical moment when he becomes much more politicized because of the economic inequities that are exposed by the Depression. He’s thinking about all of this while in Mexico, and I think if you look at his street portraits from 1916, that when he resumes portraiture in Mexico that he is going back to that work from 1916. He hadn’t tried to make pictures like that for more than fifteen years, in part because that mode of working was so uncomfortable for him. He was a very methodical artist—we’ve already talked about his deliberate staging—and he couldn’t do that with anonymous focused portraiture.

I see the Mexico portraits as a return to this body of work that he felt was very important and powerful from 1916, although he has a much more sophisticated way of making those pictures in Mexico. In my interpretation he’s much more politicized at this time in his way of thinking and is thinking about the social or economic differences between himself and his subjects, possibly. Where Strand always gets with his portraiture, even in 1916, is that he focuses so intently on details—on people’s expressions, their postures, their clothing—that he brings you right through social documentary to grappling with these subjects as individuals. That’s a very powerful factor of his portraiture from the beginning to the end, and that’s one way that you see how politics aren’t as central as some critics will have it. He has a way of making these portraits that makes you think of these people as ones with histories of their own, which have people shaped by historical events.

AP: Anything else you’d like to add?

PB: I think earlier exhibitions of his work have sometimes been guilty of evading his political views because they are controversial or because curators don’t know what to do with them. Our approach has been to foreground his political views to the extent that they are a part of the story of who Strand was and how he approached the world. But I think political art didn’t work perfectly for him. His way of working was too methodical and slow and had too many layers of literary meaning and narrative that take you outside of politics.

We want the exhibition to be very candid about Strand’s politics. We want his political views, as far as we know them and understand them, to be clear because they did inform his worldview. But I would insist that his later projects are not illustrations of his political ideas: they are much more complicated than that.

Paul Strand – Photography and Film for the 20th Century runs through May 17 at the Fotomuseum Winterthur, Zurich, Switzerland.

The post Q&A: Peter Barberie on Paul Strand appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 25, 2015

6 Photography Exhibitions to See This Month

Wolfgang Tillmans, Book for Architects, 2014. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York, Maureen Paley, London, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, New York (N.407), 1979. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery

Installation view of Shadows, 2014. Courtesy Galerie Lelong

Anonymous, Untitled, Green Hill School, Chehalis, WA. Made by young prisoner. Courtesy Steve Davis

Josh Begley, Facility 492

Willi Ruge, Seconds Before Landing; from the series I Photograph Myself during a Parachute Jump, 1931. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Six photography exhibitions to see in New York in March.

1. Wolfgang Tillmans, Book for Architects, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York:

On view for the first time since its showing at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, Book for Architects is an installation made up of ten-years-worth of 450 photographs from 37 countries on five continents. The presentation, however, is less overwhelming than it sounds: the images play in a site-specific, two-channel video shown on perpendicular walls. Through July 5

2. Francesca Woodman, I’m trying my hand at fashion photography, at Marian Goodman Gallery, New York:

For those who can’t have too much of Fashion Week—or perhaps prefer to take a subtler approach—Marian Goodman has mounted a show of Woodman’s experiments with fashion photography. Taken between 1978 and 1980 while she lived in New York City, the photographs manifest style in their quietness, and even their obscurities: cropped frames, blurred faces, bodies sliced by shadow. Through March 13

3. Alfredo Jaar, Shadows, at Galerie Lelong, New York:

Jaar’s latest exhibition, while not strictly photography, sources from Koen Wessing’s photobook Chili, September 1973, a wordless document narrated by images from the month of Chile’s military coup. Wessing, who died in 2011, was one of only a few international photographers to witness the conflict. The show includes illuminated images taken from the book that lead to a large light installation of two silhouetted figures from one of Wessing’s photographs, the anonymous figures symbolizing the many nameless causalities of war and oppression. Through March 28

4. Vera Lutter at Gagosian Gallery, New York:

Recent photographs by Vera Lutter take New York City as subject, namely the changing views from her apartment, which she turned into a pinhole camera. Projecting the outside world onto photo-sensitive paper, Lutter exposed images for days, weeks, even months, for an aptly temporal rendering of the city. Through March 7

5. Prison Obscura at the New School, New York:

This exhibition offers glimpses of the world in and around the country’s many prisons. From aerial views of compounds to intimate portraits of inmates, the photographs on view reflect the unseen facets of a system which, while constantly debated, is almost entirely hidden from view. Through April 17

6. Modern Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection, 1909–1949, at MoMA:

This sprawling exhibition gathers more than three hundred photographs from perhaps the most experimental moment in photo history, as the street, architecture, abstraction, and figuration played roles in art photography as never before. The private collection of the German-born photography collector is now on view for the first time, with images from the likes of Berenice Abbott, André Kertész, El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Maurice Tabard, Umbo, and Edward Weston, just to name a few. The four-year-long collaborative exhibition sets off the Thomas Walther Collection Project, which includes the extensive research and conservation project Object:Photo, which can be accessed online here. Through April 19

The post 6 Photography Exhibitions to See This Month appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 23, 2015

A Q&A on the 2015 Aperture Summer Open

The call for entries is now open for the 2015 Summer Open, Aperture’s second open-submission exhibition for which all photographers are eligible. Entries for the Summer Open will be accepted until Wednesday, April 8, 2015, at 12:00 noon eastern time. Entrants must bea current Aperture Foundation Member, through April 10, 2015, OR an Aperture magazine print subscriber through the Summer issue, or #219. The theme this year is Black Mirror, and will be curated by Aperture magazine editor Michael Famighetti: he recently spoke with Aperture Foundation’s executive director, Chris Boot, about the inspirations for this year’s theme and the selection process. This article also appears in Issue 1 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Chris Boot: Last year I selected the work featured in what was our first Aperture Summer Open.The exhibition turned out to be very light, and playful, because that reflected the work that was submitted. This year, as curator, you seem interested in the opposite. Tell us where that came from. Do you think the future is dark?

Michael Famighetti: The theme suggests a dark point of view, but there’s plenty of room for playful work. Science fiction is packed with play and humor, even if it’s a gallows humor. The idea came from the show Black Mirror, which I think is a clever take on a future that feels just removed from the present, a time when technology defines our lives in an ominous way. The show’s title is, for me, a photographic reference: The “black mirror” is a screen turned off. I liked that the show got at how ubiquitous screens and images shape our lives today, and, of course, the metaphor of photography as a “mirror” goes back a long way. Is the future dark? I hope not, but the present is certainly strange and troubled. Another reference for the show was an article I read by Rebecca Solnit about now being 30 years beyond Orwell’s imagined 1984 where she articulates how the present feels stranger than societies portrayed in classics of science fiction, like films by Ridley Scott or stories by Philip K. Dick.

CB: Why Black Mirror, specifically? I haven’t seen the British TV show that the title references. Are you hooked on it?

MF: I really saw the show as being about photography, or at least media and an image-based culture. The image, at least in the context of this show, is ingrained in our lives, often in a sinister way. One could certainly submit work even if you’ve never seen the show. The theme is specific but potentially encapsulates a wide range of subjects, which works well for an open call.

CB: What kind of pictures are you hoping to see?

MF: A broad range—this topic can be spun in many different directions and explored through many approaches to photography, whether documentary or more art-based. I would like to see some projects that address the place of technology in our lives, of course, but projects could relate to the economy, social media, surveillance, the environment, time travel and space, or even Edward Snowden. Photographers might look at their work and think, “Oh, I could edit something I have to dovetail with this.” Mostly I’d like to be surprised by what’s submitted and to end up with a selection that captures the strangeness of 2015.

CB: It sounds like what the future looks like in photographs, in your mind, is partly foreboding, but in a way sexy, too. Is that fair? Can you give me some examples of work that you’ve been excited by, out in the world, that fit this theme?

MF: Speculations on the future should be seductive even if they can be disquieting. In terms of some recent work that we’ve published, or that I’ve seen, that could relate to this theme, there’s Thomas Dworzak’s Instagram Scrapbooks; Andrew Norman Wilson’s project on the scanners used to create Google’s library; Lucas Foglia’s documentation of communities gone off the grid; Mishka Henner’s work; and Martin Lange’s pictures of machines in high-tech labs, that are complicated to the point of comedy.

CB: How does this project relate to your work as editor of the magazine?

MF: We’re constantly building out new themes for the magazine and trying to see as much work as possible, so the open call here could help feed future issues of the magazine as well. Even if work doesn’t end up in the show, I hope to uncover things that may make sense for something else down the road. We’ll be closely looking at everything submitted.

The post A Q&A on the 2015 Aperture Summer Open appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 20, 2015

On The Nature of Photographs

Stephen Shore, West Third Street, Parkersburg, West Virginia, May 16, 1974, from Stephen Shore: Survey (Aperture, 2014) © Stephen Shore, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

The following excerpt comes from a conversation published in Aperture magazine in 2007 (#186) between writer Luc Sante and Stephen Shore, on Shore’s The Nature of Photographs (1998). Today the book is considered a primer for those who wish to read the visual language of a photograph, from negatives to found Polaroids to images on a screen. Their conversation provides an insight into Shore’s thinking behind the original publication with Sante, one of photography’s foremost critics. The photographs that accompany this interview appear in Stephen Shore: Survey, published by Aperture in 2014, which features more than 250 images from Shore’s six-decade-long career, one that serves as an important reference point in the story of photography. This article also appears in Issue 1 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Luc Sante: I want to ask you about a particular sentence on the first page of the book: “The print has a physical dimension; it is not a true plane.”

Stephen Shore: What I mean is that it’s a piece of paper. The image has a picture plane—but a true plane exists in only two dimensions, and a piece of paper has three dimensions. I wanted to emphasize that it is an object, and that on the object there is an image. The image is an illusion that’s embedded in a physical object.

LS: At one point in the book, referring to Nicholas Nixon’s image Friendly, West Virginia, you write that Nixon solves a picture, rather than composes one. Could you elaborate on that distinction?

SS: “Composition” seems to me to be a term borrowed from painting. A vocabulary was developed in the critique of painting, and then along came a new medium that also takes place on a flat rectangle—and so photography borrowed those terms. The word “composition” comes from the Latin root componere, which means “to put together.” It is the Latin complement of the Greek root of the word “synthesis.” With a painting, you’re taking basic building blocks and making something that’s more complex than what you started with. It is a synthetic process. A photograph does the opposite: it takes the world, and puts an order on it, simplifies it. It is an analytic process.

LS: The propositions in this book are a bit like Zen koans, and sometimes they make me want a little more—as when you contrast an Eggleston picture with your picture of El Paso—and you talk about how one is an open composition and the other is enclosed.

SS: I am talking about framing. In some images, the frame acts as the end of the picture. I may want to take a portrait of you, and I decide where your face is going to go in the picture, and then I’m aware of the frame. The picture simply has to end somewhere, and I make a decision about where that is. But often with the view camera, the frame is not the end but the beginning of the picture. It’s as though the photographer starts with the frame and builds the picture in from the frame.

LS: You include a Japanese print in the book. I’ve been thinking about the Impressionists, specifically Degas, and how he learned from Japanese prints. . . . The Impressionists’ use of the frame seemed to anticipate photography. But obviously, the camera apparatus itself taught photographers with no background about the semi-arbitrary nature of framing.

SS: Degas was also taking photographs—so as an artist, he could have learned both from the Japanese print and from photography. John Szarkowski talks about the Japanese and Chinese scroll tradition: you turn the scrolls to see the image pass by, so you see an infinite number of framings—the way a photographer going out in the world sees an infinite number of framings.

LS: I was surprised by the picture by Thomas Annan in the book—of the alley with the small black square. It seems so startlingly modern: it’s about that small black square, about geometry and texture and plane as well as volume, in a way that’s astounding for a mid-nineteenth-century image. It brings to mind another picture in the book, by Berenice Abbott, Department of Docks, New York City, 1936, which, you say, “uses structural devices to emphasize deep space but has a shallow mental space.” Are you referring to more than simply this kind of imaginary refocusing that we do when looking at certain photographs?

SS: The Abbott is an interesting example, because it clearly depicts deep space from the foreground, maybe eight feet away, to the sky. But when I look at it and, let’s say, move my attention from the man in the suit in the foreground to the building behind him, I know that I’m looking at something farther away, but I don’t have that physical sensation of my eyes changing focus. Also in the book, there is a photograph by Frederick Sommer. The space it represents is only a few feet deep. When I look at that one, I have a tremendous sense of refocusing with my eyes. With Sommer, I would guess that that is a deliberate effect. With the Abbott, I don’t think it’s necessarily deliberate. I think that some photographs, simply by chance, have that quality of refocusing. I also use the Walker Evans picture of the gas station in the book. He’s so conscious of what he’s doing—he’s thinking about how this pole in the foreground relates to this gas station behind it in deep space in the real life, and how they also relate to each other sitting right on the picture plane.

LS: The Evans picture gets me thinking about metaphysics. This image is truly remarkable—it looks like a collage. The sky appears to float on a different plane, as though it were cut out from a different picture. You write: “This collaging appears when there is a difference in the degree of attention a photographer pays the different parts of this picture. For this to happen, the photographer needs to pay intense, clear, heightened attention to one part of the picture but not to another.” Which suggests that something in the physics of the photo-making process responds to desire, or to a kind of telepathy.

SS: I would put it in more matter-of-fact terms. Let’s say you’re going to take a picture of me. You’re aware of my face and my head and shoulders, and you’re deciding where you’re going to put the frame—the frame relates to what you’re paying attention to. But what if you realize that you weren’t paying attention to the room behind me? As soon as you’re aware of what’s behind me, as well as me, you make a different framing decision. The frame resonates off of what you pay attention to. So it’s not exactly metaphysical.

LS: Can you explain what relationship “mental modeling,” as you call it, has to what one might call the “signature style” of an artist?

SS: If the signature style is something genuine, something inherent, as opposed to a stylization imposed on one’s work, mental modeling is simply the natural inclination of that photographer. There has been this idea in photography of pre-visioning (to use Weston’s term), which is having a mental image of the picture. The image an experienced photographer has in mind, whether it be conscious or unconscious, can guide all the little decisions that go into making a picture. It becomes the coordinating factor. With “mental modeling,” I’m talking about making that conscious, becoming aware of it as an image, and not simply seeing out your eyes like out a window.

The post On The Nature of Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 19, 2015

Queer Aperture #218 – Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #218, Spring 2015. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, 1948, No. 8 from the series The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, sequenced 1948 © Trustees of Princeton University, and courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, 1948, No. 9 from the series The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, sequenced 1948 © Trustees of Princeton University, and courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

Why an issue on queer photography? The going narrative states that, after the culture wars of the early 1990s, we moved into an era in which sexual difference mattered progressively less, when the fight against AIDS no longer defined the gay community, and when same-sex marriage had been approved in many parts of the United States and in a handful of countries around the world. But considering the volume of recent photography we’ve encountered that is pointedly engaged with questions of queer identity and experiences—as well as work by curators and writers who are revisiting past figures and projects—it seems that queer is back on the agenda, or rather, that it never left. The public conversation about what it means to be queer (which arguably began with Stonewall in 1969) has evolved and remains not only relevant but also necessary to continue. As photographer Catherine Opie notes, “Queer photographers these days are not necessarily identifying in singular identity terms; they are interested in being part of a political discourse about how radically life has changed over the past three decades.”

One radical difference is globalization. Thirty years ago, in an effort to make her own community visible, American photographer Joan E. Biren traveled the United States and Canada presenting a slide-show history of photography foregrounding lesbians as both artist and subject. Today, Zanele Muholi cites Biren’s groundbreaking project as a key influence on her ongoing work to create a visual record of South Africa’s lesbian community, many of whom have suffered discrimination and violence. Such cross-generational dialogue threads this issue as younger photographers probe the past to engage queer archives and histories. Dean Sameshima appropriates old physique and cruising imagery from a time of secret codes and clandestine existence, a period the artist himself never experienced. This time was one that San Francisco–based photographer Hal Fischer codified in his 1977 project Gay Semiotics, revisited in these pages.

Kevin Moore introduces David Benjamin Sherry’s brashly colored landscapes, which invoke iconic American photographers, including Carleton Watkins, Edward Weston, and Minor White, Aperture’s founding editor. The subject of White’s sexuality was explored in last year’s Getty Museum exhibition that featured the little-known 1948 handmade book, The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, an early homoerotic series of White’s student-model. Two images from this project appear above, and on the occasion of this issue, we have republished Moore’s 2008 essay, “Cruising and Transcendence in the Photographs of Minor White,” on our website (aperture.org/minorwhite218).

Queer perspectives continue to offer essential counterpoints to the dominant heteronormative (and patriarchal) paradigm. Vince Aletti sums this idea up best in his contribution when he writes: “Queer doesn’t have a look, a size, a sex. Queer resists boundaries and refuses to be narrowly defined.” This idea is evident in A.L. Steiner’s anarchic collages, which playfully grapple with our moment of economic and environmental crisis, in K8 Hardy’s series of self-portraits that confound gendered tropes and play with conventions of fashion photography, and in Shannon Michael Cane’s survey of queer independent publishing. And working in a very different sociopolitical and cultural context, Ren Hang, a young Chinese photographer whose work appears on our cover, has garnered a following in his country while stirring controversy. In his raw, playful images, nudity is the norm, and sexual preference and gender begin to feel irrelevant. While Hang doesn’t identify as part of a specific queer scene or movement in China (and the term queer doesn’t entirely translate there), his provocative and weirdly beautiful images seem to be emblematic of the contemporary idea that gender and sexuality are fluid—pointing toward a future (and, for some, a present) in which traditional dichotomies of gender and sexuality no longer apply.

—The Editors

The post Queer

Aperture #218 – Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers