Aperture's Blog, page 165

February 19, 2015

From the Earth to the Moon: Vintage NASA Photographs

Buzz Aldrin, First self-portrait in space, Gemini 12, November 1966. All photographs courtesy Bloomsbury London

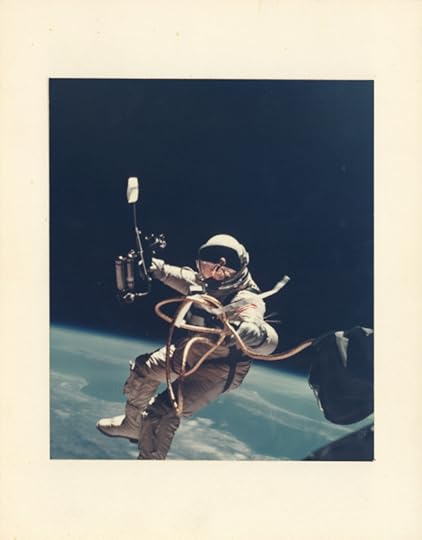

James McDivitt, First US Spacewalk, Ed White’s EVA over New Mexico, Gemini 4, 3 June 1965

Edgar Mitchell, Alan Shepard and the American flag, Apollo 14, February 1971

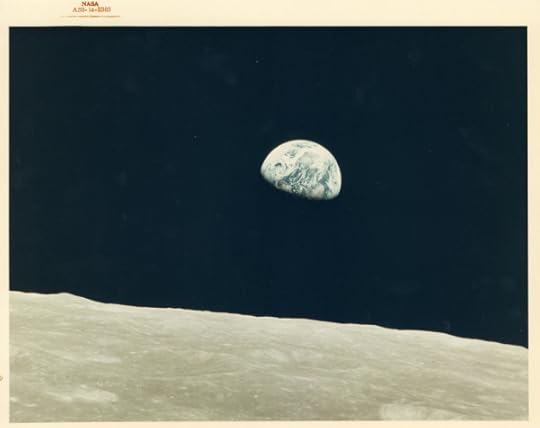

William Anders, First Earthrise seen by human eyes, Apollo 8, December 1968

Walter Cunningham, Florida Peninsula looking East, Apollo 7, October 1968

Clyde Holliday, The first photograph from space, October 24, 1946

Buzz Aldrin, The only clear photograph of Neil Armstrong on the Moon, Apollo 11, July 1969

Harrison Schmitt, Portrait of astronaut Eugene Cernan, explorer of another world, Apollo 17, December 1972

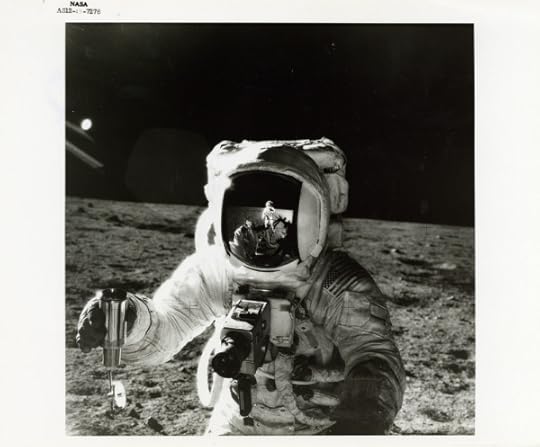

Pete Conrad, Alan Bean with the reflection of the photographer in his visor, EVA 2, Apollo 12 November 1969

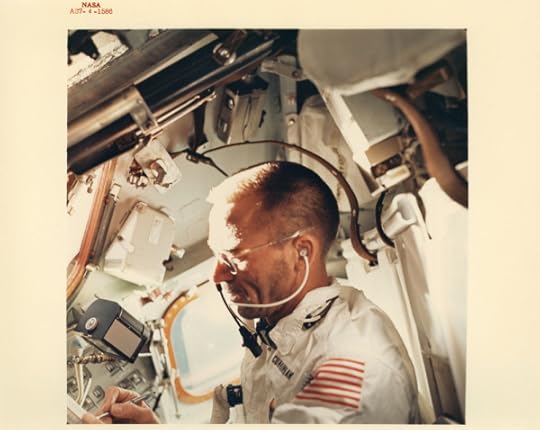

Walter Schirra, On-board portrait of astronaut Walter Cunningham, Apollo 7, October 1968

By Paula Kupfer

Since the start of space exploration, cameras have been an elemental carry-on for extraterrestrial voyages, on both manned and unmanned spacecraft. According to Hasselblad, at least twelve Electronic Data Cameras of their manufacture rest on the surface on the moon, taken into space by astronauts and later shed for their weight. The film they contained was brought back to Earth for developing, but despite the wondrous quality of the photographs, many were kept for decades at NASA’s archives, available only to specialized researchers. Many remained heretofore unpublished. Now a wealth of photographic gems from the early decades of space explorations is on view at Bloomsbury London in From the Earth to the Moon: Vintage NASA Photographs, where the over six hundred vintage prints will be auctioned on February 26. The expansive lot includes photographs spanning the Mercury, Gemini, and Lunar Orbiter as well as the famed Apollo missions, and features a vintage gelatin-silver print of the “first photograph from space” from 24 October 1946, taken by a 35-mm camera developed by Clyde Holliday and fitted on the 13th V-2 missile launched from the New Mexico desert. Vintage color prints of astronauts floating in space on EVA (extravehicular activity) from the Gemini 11 and 12 voyages are particularly stunning, as are the collages of lunar craters, mosaics of black-and-white photographs arranged into one “panoramic” view. As Sarah Wheeler, head of photographs at Bloombury Auctions, said, “these photographs are more than merely documentary, many are simply sublime.”

Paula Kupfer is managing editor of Aperture magazine.

The post From the Earth to the Moon: Vintage NASA Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 17, 2015

Brian Dillon on Conflict, Time, Photography

Luc Delahaye, US Bombing on Taliban Positions, 2001 Courtesy Luc Delahaye & Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Bruxelles

Simon Norfolk, Bullet-scarred apartment building and shops in the Karte Char district of Kabul. This area saw fighting between Hikmetyar and Rabbani and then between Rabbani and the Hazaras, 2003 © Simon Norfolk

Ursula Schultz-Domburg, Kazakhstan. Opytnoe Pole. 2012 Courtesy the artist's studio © Ursula Schultz-Domburg

Jo Ractliffe

On the road to Cuito Cuanavale IV 2009

Hand-printed silver gelatin print

Courtesy the artist

An-My Lê, Untitled, Hanoi, 1995. Courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

Chloe Dewe Matthews, from Shot at Dawn, 2013 © Chloe Dewe Matthews

This article first appeared in Issue 1 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

The title of this conceptual survey of war-derived imagery does not exactly describe a thematic cluster, rather a strict chronology: the event itself, a certain duration, followed by the act of photography. The image is captured at a greater or lesser remove: from two minutes after the fact to a distance of almost a century. The works at Tate Modern were organized according to their immediacy or belatedness: rapid responses at the start of the show, slowing by the end to examples of distant historical recovery or invocation.

In the first room were Toshio Fukada’s photographs of the mushroom cloud at Hiroshima, taken just twenty minutes after the detonation of the atom bomb. They show a raging mass, framed by leaves and branches in the foreground, that is quite unlike familiar test-site imagery. At the furthest temporal remove from historical reference, Chloe Dewe Mathews’s series Shot at Dawn (2013) records the places where soldiers were executed for cowardice or desertion during the First World War: nondescript stretches of misty early-morning countryside, once soaked in blood and shame.

Such extremes might imply that Tate curator Simon Baker’s chronological schema was simply a way of pitching photographic immediacy—the sort of reportorial proximity for which war photographers are often celebrated—against the long, slow translation of catastrophe into memory and monuments. In fact, the curatorial device had the effect of confusing timescales in surprising and resonant ways.

Historical distance may bring greater intimacy: Hitler’s headquarters in occupied Poland reveals itself as a bright and bristling ruin in Jerzy Lewczyński’s Wolf Lair series of 1960. Hiroshima and Nagasaki return time and again in the works of Japanese photographers such as Shomei Tomatsu and Kikuji Kawada, who recast the original trauma in terms of landscape, portraiture or still-life studies from the archaeology of disaster. In the late 1950s, architect and urbanist Paul Virilio photographed the sci-fi wreckage of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall fortifications; the same structures return, filtered now through the fiction of J. G. Ballard and the history of Brutalist architecture, in large-scale photographs by Jane and Louise Wilson.

For the most part Conflict, Time, Photography dealt in series and not in the single compelling or appalling image. (Exceptions included Don McCullin’s Shell-shocked US Marine, Vietnam, Hué (1968): photographed, as the exhibition’s wall text reminded us, ‘moments later’.) Many of the pictures were drawn from well-known books: Ernst Friedrich’s War Against War (1924), Richard Peter’s Dresden: A Camera Accuses (1949). Between these earlier photobooks and later conceptually minded grids of uniformly formatted images—such as Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s blown-up fragments from a Belfast archive in People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground (2011)—there was a sense of unsettling stasis across the historical span of the exhibition: from the Crimean War to contemporary Iraq and Afghanistan.

It was a textural shock, then, to enter a portion of the show drawn from the holdings of the Archive of Modern Conflict and find that the curators of this vast and eccentric collection had exhibited mostly discrete, often absurd, and energetically salon-hung works. There were German helmets piled by a canal in apparent homage to Roger Fenton’s famous Crimean cannonballs, Frank Capa’s skewed and monstrous studies of soldiers in training, and a hilarious Rolex magazine advertisement featuring none other than Don McCullin, posed in the sort of heroic snapper mode that Conflict, Time, Photography had calmly undermined.

Brian Dillon is UK editor of Cabinet and teaches critical writing at the Royal College of Art. His most recent books are Objects in This Mirror: Essays (2014) and Ruin Lust (2014).

Conflict, Time, Photography runs at Tate Modern through March 15.

The post Brian Dillon on Conflict, Time, Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 13, 2015

“Photographing the Familiar” by Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon

This excerpt from Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon’s essay for Aperture magazine #2, from 1952, appears in The Aperture Magazine Anthology.

Photography today appears to be in a state of flight.

This is clearly a harsh judgment. Some will feel it to be a false judgment; others will think it clumsy or ill-considered. But still others may feel it to have merit. They, perhaps less devoutly enlisted in this or that photographic cause, may find in their uncertainties a reason to believe the judgment sound. Themselves in disorder, they may sense some design of a larger disorder. It is an effort to explain that design—and in the conviction that there can be found for disorder a remedy—that we say what we do: that photography appears to be in a state of flight.

But why flight? What in flight from? If in flight, what can be done?

To begin with, photography is still a very young technique—one that has found power and expression in the mastery of its own mechanics. This is not only true of photography. It applies to all young techniques—to the

steam engine and the camera alike. During the early years, all photographers were in a sense inventors, and photography as a field is still infant enough to have undeveloped in it some of the features of invention. Color,

for instance, is beginning now to assert itself as a photographic value; there is excited talk of a new dimension in the motion picture; in an age perhaps more than any other dedicated to techniques, science presents to the photographic technician a challenge more important than any he has had to face before.

But, on the whole, the day is gone when the photographer could find in exploration of his equipment the expression he sought. Settled to a different pace, technical advance has permitted the photographer to catch up. The ranges of technique have been largely conquered; and that exploration ended, the photographer must seek another.

Now it is no accident that the photographer becomes a photographer any more than the lion tamer becomes a lion tamer. Just as there is a necessary element of hazard in one, in the other is a necessary element of

the mechanical. For better or for worse, the destiny of the photographer is bound up with the destinies of a machine. In this alliance is presented a very special problem. Ours is a time of the machine, and ours is a need

to know that the machine can be put to creative human effort. If it is not, the machine can destroy us. It is within the power of the photographer to help prohibit this destruction, and help make the machine an agent of more

good than of evil. Though not a poet, nor a painter, nor a composer, he is yet an artist, and as an artist undertakes not only risks but responsibility. And it is with responsibility that both the photographer and his machine are brought to their ultimate tests. His machine must prove that it can be endowed with the passion and the humanity of the photographer; the photographer must prove that he has the passion and the humanity with which to endow the machine.

This certainly is one of the great questions of our time. Upon such an endowment of the mechanical device may depend not only the state of the present but the prospects of the future. The photographer is privileged that it is a question which in his work he can help to answer.

But does he?

Unfortunately, very often not. For in his natural zeal to master his craft, he has too long relied upon the technical to engage his energies. Now the technical has relaxed its challenge, he is often left with the feeling that there is nowhere to go. He is lost; he is confused; he is bewildered. Accustomed to discovery, now suddenly he is obliged to interpret.

Click here to read more and download the Aperture Photography App.

The post “Photographing the Familiar” by Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Archive: “Photographing the Familiar” by Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon

This excerpt from Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon’s essay for Aperture magazine #2, from 1952, appears in The Aperture Magazine Anthology.

Photography today appears to be in a state of flight.

This is clearly a harsh judgment. Some will feel it to be a false judgment; others will think it clumsy or ill-considered. But still others may feel it to have merit. They, perhaps less devoutly enlisted in this or that photographic cause, may find in their uncertainties a reason to believe the judgment sound. Themselves in disorder, they may sense some design of a larger disorder. It is an effort to explain that design—and in the conviction that there can be found for disorder a remedy—that we say what we do: that photography appears to be in a state of flight.

But why flight? What in flight from? If in flight, what can be done?

To begin with, photography is still a very young technique—one that has found power and expression in the mastery of its own mechanics. This is not only true of photography. It applies to all young techniques—to the

steam engine and the camera alike. During the early years, all photographers were in a sense inventors, and photography as a field is still infant enough to have undeveloped in it some of the features of invention. Color,

for instance, is beginning now to assert itself as a photographic value; there is excited talk of a new dimension in the motion picture; in an age perhaps more than any other dedicated to techniques, science presents to the photographic technician a challenge more important than any he has had to face before.

But, on the whole, the day is gone when the photographer could find in exploration of his equipment the expression he sought. Settled to a different pace, technical advance has permitted the photographer to catch up. The ranges of technique have been largely conquered; and that exploration ended, the photographer must seek another.

Now it is no accident that the photographer becomes a photographer any more than the lion tamer becomes a lion tamer. Just as there is a necessary element of hazard in one, in the other is a necessary element of

the mechanical. For better or for worse, the destiny of the photographer is bound up with the destinies of a machine. In this alliance is presented a very special problem. Ours is a time of the machine, and ours is a need

to know that the machine can be put to creative human effort. If it is not, the machine can destroy us. It is within the power of the photographer to help prohibit this destruction, and help make the machine an agent of more

good than of evil. Though not a poet, nor a painter, nor a composer, he is yet an artist, and as an artist undertakes not only risks but responsibility. And it is with responsibility that both the photographer and his machine

are brought to their ultimate tests. His machine must prove that it can be endowed with the passion and the humanity of the photographer; the photographer must prove that he has the passion and the humanity with which

to endow the machine.

This certainly is one of the great questions of our time. Upon such an endowment of the mechanical device may depend not only the state of the present but the prospects of the future. The photographer is privileged that it is a question which in his work he can help to answer.

But does he?

Unfortunately, very often not. For in his natural zeal to master his craft, he has too long relied upon the technical to engage his energies. Now the technical has relaxed its challenge, he is often left with the feeling that there is nowhere to go. He is lost; he is confused; he is bewildered. Accustomed to discovery, now suddenly he is obliged to interpret.

This article first appeared on the Aperture Photography App. Click here to

Click here to read more and download the Aperture Photography App.

The post Archive: “Photographing the Familiar” by Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 12, 2015

Rescripted After a conversation between Moyra Davey and Matthew S. Witkovsky

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014, “Lit.” Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Literary and personal histories coalesce in Moyra Davey’s elegant works in photography and video. For her ongoing “mailer” projects, begun in 2006 and included in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, Davey folds photographs made with a point-and-shoot camera and printed on durable paper and mails them to various recipients, including family and colleagues; when unfolded and displayed in grid formation on gallery walls, the images, photo-letters marked with sections of colorful tape and postage stamps, bear the traces of transit. Her video works invoke writers, from the transgressive Jean Genet to the nineteenth-century proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, as in Les Goddesses (2011), a piece Davey describes as “a love letter to my family,” and at other moments depict readers’ reactions to passages of writing. In the following conversation, loosely structured as a play, the artist speaks with Matthew S. Witkovsky, curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, about her practice of interlacing photography with literary touchstones, the Norwegian literary phenomenon Karl Ove Knausgaard, with whom Davey shares an affinity for the quotidian, and her work as a writer, which ranges from reflections on photography to personal essays.

—The Editors

Moyra Davey, The End, 2010 (detail) courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

Moyra Davey, The End, 2010 (detail) courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

An eleventh-floor apartment on Riverside Drive in northern Manhattan. Stately multistory buildings, sloping streets, longtime tenants. “How the Upper West Side used to be.” Sunny rooms, improbably bare in feel despite the jumble of books and framed artworks coating the simple plaster walls: posters by Sister Corita Kent, photographs by Bruce Davidson, Zoe Leonard, Danny Lyon. Furniture has a spartan or improvised quality (which is it? Moyra says both). In the kitchen at rear, a lovingly restored midcentury stove with a griddle and four small ovens sits in an elongated space that evokes rusticity. None of her own photographs, but of course plenty of what appears in them, such as shelves of records topped by old stereo equipment. A sense of being on set, even, for viewers of Moyra Davey’s Les Goddesses, particularly strong when one sees in the back bedroom two bikes and a low mattress, on which Davey leafed through her early photographs in that book-length video.

MW: While it is true that artists in every domain make books, there is a long history of the photobook in particular as a main form of expression, rather than a side project or a record of other works of art. As a photographer, did you come to writing through an interest in making books? What was your first book of writings?

MD: Long Life Cool White (2008). But what got me hooked on writing as part of my working method was editing Mother Reader (2001). I spent a couple of years reading all those texts, shaping the book, and then wrote an introduction. After that, reading and writing became so much more central to what I do.

MW: Were you not reading as much before putting that book together?

MD: I was reading while studying for my MFA, so, targeted theoretical stuff, and then in the Whitney program, also targeted reading. After that I stopped that kind of reading and started

to read literature.

MW: Funny: I stopped reading literature, which had given me all my ideas, once I was through with my undergraduate major in literary theory and had shifted fully into art history. The malformation of the art historian, no doubt: you get impatient with plot and drop the book once you think you’ve understood its underlying structure.

MD: I don’t read so much fiction, but like everyone lately I have been reading Karl Ove Knausgaard (My Struggle, 2012 [English translation]). It took me a hundred pages to get into it, and I frankly didn’t think I would continue—but then halfway through there’s a major dramatic event and I was hooked. He’s like candy now.

Moyra Davey, Ornament and Reproach, 2012–13 (installation view) courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

MW: What’s his style?

MD: Endless description. You have to imagine that the guy has a photographic memory. Run-on pages of mundane but fascinating details of his life, conversations recorded, and, here and there, digressions on figures like the poet Friedrich Hölderlin, or jabs

at post-Structuralist theory. It’s amazing.

MW: Is it the sort of thing where he tries to keep an impersonal voice, so that meaning comes out of an endless accumulation of facts?

MD: He has a slightly caustic voice, a bit misanthropic, ever so slightly, and maybe that’s what keeps it impersonal. Although he does express a lot of emotion, a lot of grief. I want to think more about how he does it, because it interests me.

MW: You’re building your craft as a writer …

MD: I am, yeah, slowly. I’ve never taken a writing class, though, in my entire life. I’ve always been a very reluctant student, in photography as well. Impatient. Always thought of myself as a bad student. If Eileen Myles were teaching a poetry class, though, I would jump on that. I know she has done that, back in the day.

Getting back to structure: I know it’s important. For someone to want to read something, there has to be some glue, a raison d’être, but yet I resist it. To read any piece of writing or see a movie that does the full circle thing is very satisfying—the closure, the return—but for some perverse, stubborn reason, I avoid it.

MW: And yet your video Les Goddesses is beautiful, like a nineteenth-century novel. Expansive yet incredibly tightly composed. It does have closure of a sort, and it employs many novelistic attributes: lengthy narration, the introduction and development of characters. It also has the symmetry

of a return at the end to what comes in the beginning.

MD: I guess it does. It starts and ends with still photographs.

But I did that almost unconsciously.

MW: Yes, we begin the film by looking at your photograph

of your sisters in the early 1980s, standing, as you say, like caryatids, and then at another that shows two of them, Jane and Kate, lying on the grass—but in voice-over you are talking about the Wollstonecraft family. Literature and photography are held up for comparison and further analogized to the relation of still and moving images.

MD: And to mise-en-scène versus documentary photography.

Moyra Davey, Seven, 2014 courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

MW: These comparisons are not parallels, not sets of lines

that never touch. Instead, you’ve polluted relations, crossed the lines. Nor is the content exactly pure: sex, drugs, debauchery!

MD: Yeah, I think I’m going to do a part two. Things have happened in my family since I made that video. Jane’s youngest daughter, Hannah, overdosed on fentanyl, a synthetic opiate. Very potent. She was nineteen. She’s in the last video I made, My Saints (2014).

MW responds with surprise and momentary upset at the revelation. MD’s voice remains steady.

Hannah hid it so well. When you see her in My Saints, she’s chatting, ebullient; you would never suspect she was on downers. There were signs, but a lot of people missed the signs. That and other things make me want to—[emphatic] Matt, I could revisit that entire video and remake it totally differently.

MW: A rewrite then. Habits of writing give you certain license, I think, that for better or worse you don’t get in the visual arts. Published revisions are a normal part of the writing process. A fictional story—or an art history essay—

can start its public life at a reading, then become a magazine article, a contribution to a multi-author anthology, and after, a chapter in a book. What would you revisit if you did remake the video?

MD: Les Goddesses was kind of a love letter to my family. I think I idealized them. Everything in it is true, of course. But a lot is left out, which is one reason I term those videos “auto-fiction.” Remaking the work, I could do something much grittier. I didn’t show the family as they are now, for instance—

MW: Would you then be putting people back in the work?

In Les Goddesses you treat the living human figure literarily, but not pictorially. The video shows photographs of your family only from your earliest years—pictures that you showed no more than one or two times before “giving up” taking photographs of people around 1985.

MD: I actually videotaped my sister Jane walking, talking, smoking cigarettes in the park. But I don’t know if I’d have the guts to pursue that kind of thing. The remove and control you have working with still photographs is pretty great. Although, My Saints is made up of interviews with friends and family. So maybe I’m a step closer to filming my siblings in the flesh.

MW: You do have remarkable formal means to bridge the gap between photography and writing. The mailers, for example: these are recent photographic grids of yours, the prints for which you have printed on heavier, coated paper, then folded and sent by post to friends and colleagues. The individual images (ranging from a handful to several dozen) are gathered together for display as a composite wall work. Their address and your own are plain to see, covering the images, along with adhesive tabs that were used to hold the folded photograph flat in the mail. They, too, are love letters, sent only to those you know.

MD: Here is one I made showing my sisters, derived from a group photo taken around 1971. We all have that hippie look. It’s called Seven (2014), based on a J.D. Salinger character who is one of seven siblings. It’s funny because, other than Catcher in the Rye I don’t really like Salinger…. After I made the photo piece, I dug up this clever, sniping letter from one of my sisters, sent to me when I was in Paris in 1977, describing all the shenanigans going down with my siblings in my absence. And it was exactly seven pages long, a perfect match. I photographed each page separately and concealed her name to protect her privacy, though I doubt she’d care.

MW: Fragments of writing, on the one hand, and fragments of a picture on the other hand. It should be pointed out that the pictorial fragments don’t divide neatly—we see parts of one or more sisters in each of the (nine) parts of the family photo mailer—whereas your mailer of the one sister’s letter does appear as a single sheet per picture.

MD: Except that parts of the writing are covered with stamps and labels and tape, so you can’t read everything. You can read passages but not all of the writing.

MW: It’s another way of revising: covering over. Hiding and revealing simultaneously seems to be your way of coming to terms with a sort of confessional self-expression.

MD: It is confessional, but I’ve found distance through a certain dispassionate, dissociative stance. I feel simultaneously that it’s me and not me writing and performing this material. It would be a good challenge now to make a video where the faces are no longer pretty.

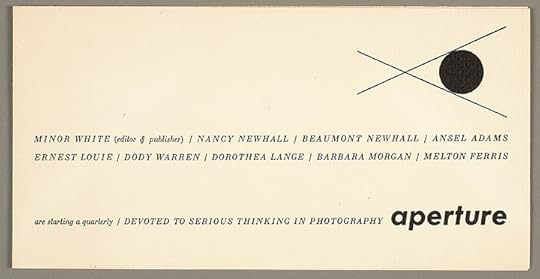

Moyra Davey, Video still from Les Goddesses, 2011 courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

MW: You’ve quoted a line from Jean Genet, saying I’m fifty and I look like sixty, and I think that’s fabulous …

MD: He says, I’m not ashamed.

MW: Right, and he’s writing to this young man, Java.

MD: His former lover. And he adds, “I even find it rather restful.”

MW: Yes, I’m amazed I forgot that bit of the quote, because it is beautiful. Restful: what a perfect word. A whole lot of youthful energy is expended in making oneself presentable.

MD: And middle-age energy too. In a section of My Saints titled “Vanity,” I start with a line about the “bleaching white light of vanity,” and then enter the frame, my face sun-bleached out. Later I go to “Vanitas,” a view of one of my nieces, who has a tattoo of her skeleton on her back—all the bones—wait, I have to get you the picture to show you…

Walks away. A half-minute of silence while she searches.

MW: This is an incredible picture, your niece, her skeletal structure imprinted on her skin. Like wearing your own X-ray—more questions of how to articulate structure and content. I was about to ask how you structure the making of your videos, whether you follow conventions of scripting or storyboarding.

MD: I don’t storyboard, but I always write something. I wrote this text (Burn the Diaries) and thought it was going to be the video (My Saints). Then I started to perform it and realized that I need to get others in front of the camera to make this work.

I do appear in the one scene, and I’m heard off-camera pretty regularly. There’s a lot of talking but also text—rolling and static. That was a device I set out to use from the onset as a way to modulate the spoken word.

MW: You ask viewers to look at language and read it as well. Unlike many career writers but like a lot of visual artists interested in language, you seem fascinated by the material objects and paraphernalia of writing.

MD: I love paper, and I have fountain pens, and I love soft pencils; but the only way I can seriously compose anything is on the computer. Actually, I really began writing only when I met Jason [Simon, a filmmaker], in 1986, and he had a little Mac. It was so much more accessible to me to type on that.

MW: When I read your books now, I hear your voice, not my own. You read more slowly aloud than I do when reading to myself, so I slow down to accommodate what I remember as your cadences and pauses. It’s an odd feeling, having another voice in my head.

MD: When I sit down to write something, my instinct is “start with the most pressing thing.” Then I go to the notebooks, read through them systematically and pull out anything of interest. And then build on those extracts. You know what I would like to do: write without intertitles. That would be a good challenge, because using intertitles is a very easy way for me to write, in short fragments. Having the intertitles gives my writing a de facto structure.

Moyra Davey, Video still from My Saints, 2014 courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

MW: I just assumed you used intertitles out of a persistent love for Walter Benjamin.

MD: Yes, and Roland Barthes. But it is a bit of a crutch.

MD and MW each get up to fetch something for the other. MW returns with a small book of pictures and quotations from Japanese photographer Shomei Tomatsu.

MW: There were just a few copies printed of this book after

a show that we did last fall, which in its concept was intended as a book on a wall. The installation had writings interspersed with photographs, in quotations printed at the size of a standard 11-by-14-inch photograph; text as image and also

as the equal of images. He was a brilliant writer, I think. It was an especially meaningful show for me, largely because of the importance of his dual practice as writer and photographer.

MD: Thank you for this!

Speaks as she leafs slowly through the book.

I have his book [Chewing Gum and Chocolate, Aperture, 2014] and have just started reading it. You can tell right away he had the knack, a natural scribe. It’s so unpretentious, so unassuming, but so observant of what is going on around him, and of himself, his own position in that postwar world. Writing that’s a little bit elliptical, running on a parallel track to the photographs yet intersecting at points with them.

Moyra Davey, Video still from My Saints, 2014 courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

MW: When you think about it, for all the emphasis on book- making in photography—and that is where we started this afternoon—there seem to be relatively few photographers who give themselves seriously to writing. Tomatsu is unusual in that sense. Maybe it’s a further sign of his promiscuity,

a word you’ve used lately as well. Tomatsu moves in and out of straight documentary photography, but he also likes montage, he likes abstraction, he likes mixing color and black and white … and he likes to write, and even to test different voices, from the statistical to the emotional, the novelistic

to the epistolary. His great midcareer retrospective book I Am a King (1972) has at its center a section on the height of the student protests, in 1969–70, and in this section he pairs photographs with a month’s worth of diary entries. In short, Tomatsu does not mind being literary. That’s true right from his start in magazines at the tail end of the 1950s and early 1960s. This is very unlike his near-contemporary Robert Frank, whose book The Americans (1958–59) depended for its words on Jack Kerouac. It’s even further from the classic photobooks of the 1920s and ’30s, in which photographers’ efforts were often framed with essays or statements by hired critics. Although there are many more examples of photographer–writers in recent decades, an extensive literary commitment such as yours remains unusual.

Of course there is still the question of whether anyone reads.

MD: Living with a seventeen-year-old boy who only wants to leave the house with his phone (permanently outlined on his thigh) and his wallet—won’t carry a book—it’s a question we ask here every day. He listens to music, and he reads challenging stuff for school, but he stopped reading for pleasure once electronics entered his life. I, on the other hand, should devote more time to listening to music.

[Conversation continues.]

_____

Matthew S. Witkovsky is Richard and Ellen Sandor Chair and Curator, department of photography, the Art Institute of Chicago. photography is now celebrating its fortieth anniversary as a curatorial department with a series of presentations from the permanent collection, including a room devoted to work by Moyra Davey.

The post Rescripted

After a conversation between Moyra Davey and Matthew S. Witkovsky appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

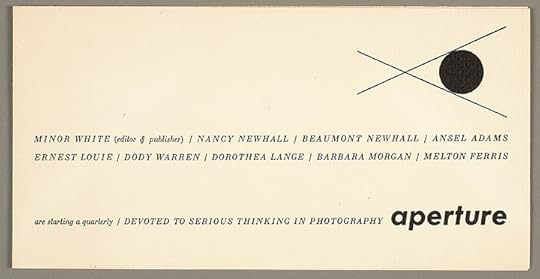

Introducing the Aperture Photography App

The Preview Issue of Aperture Photography, pictured above, can be found in the iTunes Store.

Aperture Foundation is excited to announce the Aperture Photography App—a new, free publication delivered to your iPhone, iPod, or iPad twice a month. You can subscribe through the iTunes store to be alerted whenever the latest issue is ready to download. The Aperture Photography App will keep readers updated about what’s new on “the Aperture beat,” in a short digest of the many goings on at Aperture Foundation. We’ll also feature regular reviews from the world of photography beyond our doors.

You’ll get to sample some of the things we have coming out in Aperture magazine, in our new books, and in The PhotoBook Review. We’ll offer insights behind the scenes of various projects, including books and exhibitions in the making and our education programs, showcasing some of the talented artists and thinkers within the photo world coming through our New York offices, and participating in our programs. As we mine our archives for items that shed light on photography today, we’re also using this app as a place to republish classic features from more than sixty years of producing Aperture magazine, and forty-five years of publishing books. We hope these easily accessible stories will enliven and deepen your journey in photography, and your appreciation of the photographers we are working with.

A view inside Aperture Foundation’s offices in Chelsea, New York City.

For those who already follow the blog, check the app for a first look: stories will appear there before they run on the website. We’ll adapt to readers’ interest as we go along, so please do write to our online editor, Alexandra Pechman, at apechman@aperture.org, so we can foster a dynamic relationship with our readers on this new platform. We hope to introduce you to work and ideas in the world of photography while we engage your interest in the range of everything we’re working on right now at Aperture Foundation.

Click here to read more and download the Aperture Photography App.

The post Introducing the Aperture Photography App appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 11, 2015

Sabine Mirlesse on Alix Cléo Roubaud at BnF

By Sabine Mirlesse

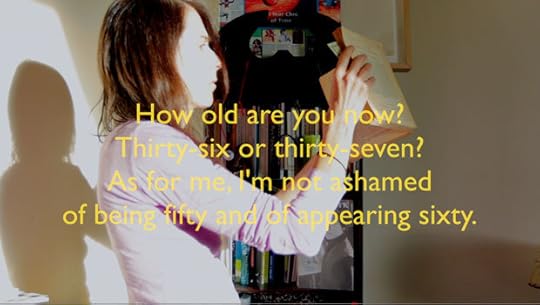

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Si quelque chose noir 7/17, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Si quelque chose noir 17/17, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

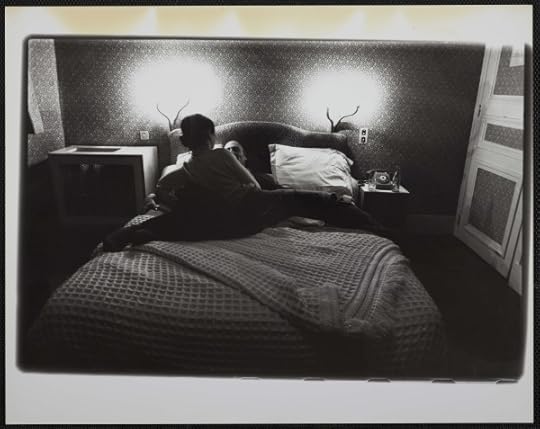

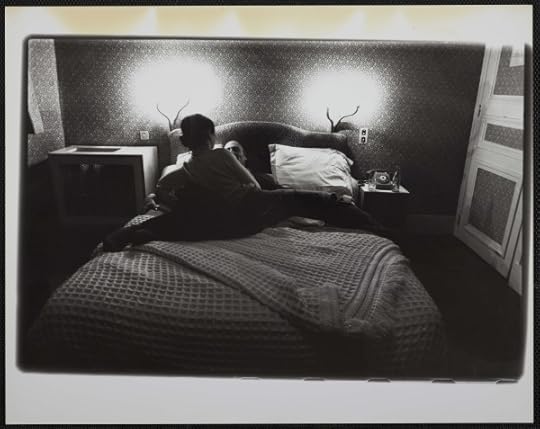

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Autoportrait avec Jacques Roubaud, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Roubaud/Hélène Giannecchini

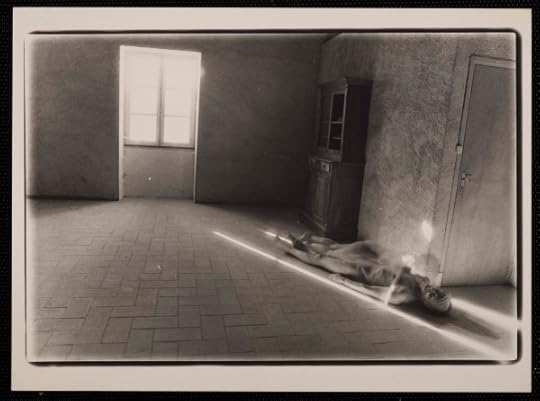

Alix Cléo Roubaud, from the series "Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration," 1980. BNF, estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

“All photography struggles against death and the passage of time,” Alix Cléo Roubaud says in a video titled Les Photos D’Alix (1980) by Jean Eustache, on display in her exhibition at Bibliotheque Nationale de France’s gallery in Paris, titled Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration. Yet those words grow eerie, as one quickly learned that the dozens of photographs on view were from not a lifetime’s work spanning decades, but rather from the four-year period before Roubaud’s death in 1983, at the age of 31, of pulmonary disease.

If death is represented by darkness, Roubaud’s images confront it with light—literally burning it out of her images, bathing her subjects in white, her landscapes seemingly floating in ether. Roubaud also drew on her negatives and prints, often stopping the development process before it was finished. She also layered texts and made double exposures, as in La Dernière Chambre (1979), where she overlaid text and image to create visual palimpsests. In some cases, she moved the frame itself and made it the central element of the final image, as in the Non Contact Theory series from 1980; in others she used burning and dodging techniques to completely remove elements of an image that didn’t interest her. She believed “the only real photographs are the ones of [one’s] childhood,” and so perhaps considered her own photographs less sacred and thus ready candidates for manipulation. But she also rephotographed her childhood album images, creating new material to play with. Perhaps because she used her negatives like a painter uses a color palette, self-awareness successfully melts away into the permeability of being both photographer and artist simultaneously, rather than separately—her formal choices feel natural rather than as though a gimmick were at play.

Born in Mexico in 1952 to Canadian diplomats, Alix Cléo Blanchette grew up in various countries, including Egypt and Portugal, moving according to her parents’ professional obligations. Because of Roubaud’s fragile lungs, she preferred warmer climates and decided to study philosophy in Aix-en-Provence rather than at Cambridge or in Paris. She wrote her thesis on Ludwig Wittgenstein. In 1979, she met the writer Jacques Roubaud (whom she later married) and decided to become a photographer. A year later, she presented her first, and only complete, series—on view now at the Bibliothèque Nationale for the first time—entitled Si quelque chose noir (If anything black), a seventeen-image sequence mirroring the syllable count of a haiku. Following the medieval Japanese tradition of “Rakki tai” or “taming one’s demons,” in the series she imagines her own death in order to confront it. She passed away before completing her next major project.

Roubaud kept journals her entire life and wrote candidly, likely with the idea that her words would be read after her passing. Snippets of her writings decorate the walls of the first exhibition room at the Bibliotheque: they are excerpts from her journals, fragments of her life philosophy, her thoughts on photography in general, and loose memories and musings. These words enrich the photographs on view, adding another layer of intimacy to the palimpsest, and echoing the sound of her voice streaming from the video playing in a room at the far end of the space. “I used this photograph to seduce a man once” she says at one point during the film, gesturing towards an image she has laid out. Describing another she says, “I was very, very hot that day, which I indicated with the incorrect, overexposed whiteness,” signaling that she burned into the frame. Her personal life informs her technique, and everything seems to be part of a carefully plotted plan—so much so that she destroyed most of her negatives and only left behind unique prints.

Alix Cléo Roubaud is virtually unknown, and any of her minor notoriety has arrived posthumously, thanks to her husband’s dedicated archiving and promotion of his late wife’s work. Yet her images seem to find a place alongside that of artists like Duane Michals or Francesca Woodman, who also have used the photograph as a canvas to explore and transcend intertwined layers of process and metaphysics, intimacy, and philosophy. Roubaud had no time to waste, infusing each frame with her own sense of mortality and pushing back against it. It is now possible to view these poignant proofs of her existence, and to feel her absence, imagining the possible career she might have had—a duality that she perhaps sought to manifest. It’s rare today to feel as though one has stumbled upon an important talent about which few people know, particularly when that talent has departed and left an oeuvre created with purpose and deliberation, mysterious yet knowing.

Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration ran from October 28, 2014 to February 1, 2015 at the Bibliotheque Nationale de France’s gallery in Paris.

Sabine Mirlesse is a photographer and visual artist living in Paris. Her first book, As if it should have been a quarry, a collection of images shot in Iceland between 2011-2013, is now available through D.A.P. Artbook and Damiani Editions. She has additionally contributed to Art in America, BOMB, and the Paris Review as a writer and interviewer

The post Sabine Mirlesse on Alix Cléo Roubaud at BnF appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Sabine Mirlesse on Alix Cléo Rouboud at BnF

By Sabine Mirlesse

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Si quelque chose noir 7/17, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Si quelque chose noir 17/17, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

Alix Cléo Rouboud, Autoportrait avec Jacques Roubaud, 1980. BnF, Estampes et photographie ©Jacques Roubaud/Hélène Giannecchini

Alix Cléo Roubaud, from the series "Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration," 1980. BNF, estampes et photographie ©Jacques Rouboud/Hélène Giannecchini

“All photography struggles against death and the passage of time,” Alix Cléo Roubaud says in a video titled Les Photos D’Alix (1980) by Jean Eustache, on display in her exhibition at Bibliotheque Nationale de France’s gallery in Paris, titled Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration. Yet those words grow eerie, as one quickly learned that the dozens of photographs on view were from not a lifetime’s work spanning decades, but rather from the four-year period before Roubaud’s death in 1983, at the age of 31, of pulmonary disease.

If death is represented by darkness, Rouboud’s images confront it with light—literally burning it out of her images, bathing her subjects in white, her landscapes seemingly floating in ether. Roubaud also drew on her negatives and prints, often stopping the development process before it was finished. She also layered texts and made double exposures, as in La Dernière Chambre (1979), where she overlaid text and image to create visual palimpsests. In some cases, she moved the frame itself and made it the central element of the final image, as in the Non Contact Theory series from 1980; in others she used burning and dodging techniques to completely remove elements of an image that didn’t interest her. She believed “the only real photographs are the ones of [one’s] childhood,” and so perhaps considered her own photographs less sacred and thus ready candidates for manipulation. But she also rephotographed her childhood album images, creating new material to play with. Perhaps because she used her negatives like a painter uses a color palette, self-awareness successfully melts away into the permeability of being both photographer and artist simultaneously, rather than separately—her formal choices feel natural rather than as though a gimmick were at play.

Born in Mexico in 1952 to Canadian diplomats, Alix Cléo Blanchette grew up in various countries, including Egypt and Portugal, moving according to her parents’ professional obligations. Because of Rouboud’s fragile lungs, she preferred warmer climates and decided to study philosophy in Aix-en-Provence rather than at Cambridge or in Paris. She wrote her thesis on Ludwig Wittgenstein. In 1979, she met the writer Jacques Roubaud (whom she later married) and decided to become a photographer. A year later, she presented her first, and only complete, series—on view now at the Bibliothèque Nationale for the first time—entitled Si quelque chose noir (If anything black), a seventeen-image sequence mirroring the syllable count of a haiku. Following the medieval Japanese tradition of “Rakki tai” or “taming one’s demons,” in the series she imagines her own death in order to confront it. She passed away before completing her next major project.

Rouboud kept journals her entire life and wrote candidly, likely with the idea that her words would be read after her passing. Snippets of her writings decorate the walls of the first exhibition room at the Bibliotheque: they are excerpts from her journals, fragments of her life philosophy, her thoughts on photography in general, and loose memories and musings. These words enrich the photographs on view, adding another layer of intimacy to the palimpsest, and echoing the sound of her voice streaming from the video playing in a room at the far end of the space. “I used this photograph to seduce a man once” she says at one point during the film, gesturing towards an image she has laid out. Describing another she says, “I was very, very hot that day, which I indicated with the incorrect, overexposed whiteness,” signaling that she burned into the frame. Her personal life informs her technique, and everything seems to be part of a carefully plotted plan—so much so that she destroyed most of her negatives and only left behind unique prints.

Alix Cléo Roubaud is virtually unknown, and any of her minor notoriety has arrived posthumously, thanks to her husband’s dedicated archiving and promotion of his late wife’s work. Yet her images seem to find a place alongside that of artists like Duane Michals or Francesca Woodman, who also have used the photograph as a canvas to explore and transcend intertwined layers of process and metaphysics, intimacy, and philosophy. Roubaud had no time to waste, infusing each frame with her own sense of mortality and pushing back against it. It is now possible to view these poignant proofs of her existence, and to feel her absence, imagining the possible career she might have had—a duality that she perhaps sought to manifest. It’s rare today to feel as though one has stumbled upon an important talent about which few people know, particularly when that talent has departed and left an oeuvre created with purpose and deliberation, mysterious yet knowing.

Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration ran from October 28, 2014 to February 1, 2015 at the Bibliotheque Nationale de France’s gallery in Paris.

Sabine Mirlesse is a photographer and visual artist living in Paris. Her first book, As if it should have been a quarry, a collection of images shot in Iceland between 2011-2013, is now available through D.A.P. Artbook and Damiani Editions. She has additionally contributed to Art in America, BOMB, and the Paris Review as a writer and interviewer

The post Sabine Mirlesse on Alix Cléo Rouboud at BnF appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 10, 2015

Adam Ekberg’s “Orchestrating the Ordinary” at ClampArt

By Gabriel H. Sanchez

Adam Ekberg, A disco ball on the mountain, 2005. All photographs copyright Adam Ekberg and courtesy ClampArt, New York City

Burning skull, 2014

Eclipse, 2012.

Goldish, 2013.

Outpost #1, 2011

Sparkler on a frozen lake, 2006

A camera in the forest, 2008

Occurrence #2, 2012

Adam Ekberg’s first solo exhibition in New York, “Orchestrating the Ordinary,” presents a collection of sixteen recent photographs that depict surprising, brief moments in time rendered in vivid large format. He stages what he describes as “minor spectacles,” by pointing mirrors toward mirrors, flashlights to flashlights, to create a variety of hypnotic lighting situations in otherwise mundane spaces. Cool and calculated, the images also wear a thin lining of humor.

Ekberg’s images showcase the unique qualities of different kinds of light and matter. In the photograph Candle, mirrors, and laser, 2014, a solitary candle illuminates the wooden table it sits on and a nearby mirror. From outside the frame, a red laser beam cuts through the darkness aimed directly into the mirror’s reflection, dividing the beam into geometrical cross-sections. The two types of light contrast with and complement each other. Elsewhere, in Aberration #8, 2006, and Eclipse, 2012, Ekberg trains his eye on the most vital light source—he made both photographs by pointing the camera directly into the sun. A lens flare appears as a result in both images, and with it, a spectrum of hues unfolds across the frame.

Other photographs fetishize light even further. In A disco ball on the mountain, 2005, a mirrored orb is hung incongruously in a dark and snowy forest, appearing to explode from the inside out; in Outpost #1, 2011, the photographer finds a string of patio lights strewn over a flowing river at dusk. Other works discover formal beauty in the properties of liquid: in the case of Occurrence #2, 2012, it’s spilt milk, evoking the iconic 1957 photograph by Harold Edgerton. One huge splash leaps from its cup and off a vacant dining room table, frozen in time by Ekberg’s camera, a spectacle that might otherwise pass unnoticed.

“Orchestrating the Ordinary” runs through February 14, at ClampArt in New York City.

Gabriel H. Sanchez is a writer, photographer, and BuzzFeed’s Photo Essay Editor. He is currently based in New York City.

The post Adam Ekberg’s “Orchestrating the Ordinary” at ClampArt appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 9, 2015

Geoff Dyer & Janet Malcolm on Photography and Writing

The following conversation first appeared in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014, “Lit.” Subscribe here to read it in full, in print or online.

Of the influential British art critic and novelist John Berger, writer Geoff Dyer deems most striking Berger’s “ability to keep looking, staring at a picture until it yields its secrets.” Dyer’s comment appears during the following exchange with critic Janet Malcolm. Dyer and Malcolm, two distinguished writers on photography, were drawn to the medium for different reasons. Although Malcolm suggests that they may even reside within different rooms in photography’s many mansions, both agree that good writing on images begins with an urge to “keep looking.

Malcolm is a longtime staff writer for the New Yorker and a force in American writing and journalism. She is the author of more than ten books, which include Diana & Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography (1980); The Journalist and the Murderer (1990); The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes (1994); Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice (2007); and Iphigenia in Forest Hills: Anatomy of a Murder Trial (2011). Her recent collection Forty-One False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers (2013) includes, among other pieces, writings on Diane Arbus and Thomas Struth and a brilliant 1986 portrait of Artforum then-editor Ingrid Sischy, and demonstrates that, no matter the subject, Malcolm’s approach is analytical and precise, almost photographically so.

Geoff Dyer is equally catholic in his selection of topics, usually approached in a pleasurably digressive style entirely his own. His book about photography, The Ongoing Moment (2005), is organized around various photographers’ handling of subjects, from blind individuals to hats to benches. Dyer warns his readers in the book’s introduction: “I suspect that this book will be a source of irritation to many people, especially those who know more about photography than I do.” Surely even the most informed readers benefited from his unique approach. Dyer’s other books include Out of Sheer Rage (1997), an achingly funny book about not writing a book about D.H. Lawrence; an essay collection titled Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011, winner of a National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism); Zona (2012), about Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker; and most recently, Another Great Day at Sea: Life Aboard the USS George H.W. Bush (2014).

When Aperture asked Dyer and Malcolm this past summer to correspond about their respective practices as writers who share an abiding interest in photography, the ensuing email exchange took place over a number of weeks, with Dyer corresponding from his temporary residence in Venice, California, and Malcolm from her summer home in rural Massachusetts. The conversation is fittingly interrupted at one point by a summer storm; an impasse is overcome, improbably, by a surprisingly relevant discussion of aircraft carriers. Dyer and Malcolm may not reveal any secrets as to how they both so precisely bring their subjects into sharp focus. Indeed, there may be none to reveal— aside from a preternatural talent for translating close looking into shrewd writing.

- The Editors

Tamara Shopsin & Jason Fulford, photo-illustration (after Kenneth Josephson), 2014

Geoff Dyer: How did you first become interested in photography? Did this interest precede your writing about it or did the two things occur more or less simultaneously? At the risk of preempting your answer, at what point did an interest in photographs or photographers become an interest in photography?

Janet Malcolm: Like Julia Margaret Cameron, I became interested in photography when a relative gave me a camera. Unlike Mrs. Cameron, I did not become a great photographer, or even a good one. I learned no technique. Most of the pictures I took were either under- or overexposed. Chance dictated that some images emerged clearly. But I loved taking pictures and would take the camera—a Leica M3—on all trips.

I had read that Cartier-Bresson thought of his Leica as an extension of his eye, considering it a great improvement over the large, heavy cameras that were its predecessors. It permitted him to run around Paris having his decisive moments. It has taken me years to realize that (1) traveling with a camera and seeing everything through its eye rather than through one’s own may not be the best way to see the world, and (2) the Leica is not a lightweight object but a heavy, cumbersome thing when compared to the deliciously lightweight point-and-shoot and cellphone cameras of today.

I began writing about photography with the spurious authority of the young. I probably thought that my experience as an amateur photographer was some sort of qualification. Above all, I was inspired by John Szarkowski’s brilliant directorship of the Museum of Modern Art’s photography department and by his book Looking at Pictures. What about you? How did you come to write about photography? What drew you to it?

GD: Almost entirely it was reading about it (rather than actually looking at pictures). The big three: you know, two Bs and an S—Barthes, Berger, and Sontag—and a bit of a third B: Benjamin. I wrote a few small things on photographers for British papers and then I became very interested in photographs of jazz musicians when I was writing But Beautiful in 1989, particularly in the question of whether, or how, to convey sound visually. But I was using the pictures mainly as a source for fiction so was far more concerned with the people in the pictures than I was with the people who took them, something I became interested in only later. (That happened when I realized that a picture of D.H. Lawrence was also a picture by Edward Weston.) I still think jazz is an art form that’s been very well served by photography. Do you know Roy DeCarava’s amazing picture of Ben Webster and John Coltrane?

JM: No, I don’t.

GD: I didn’t know it at the time I was writing But Beautiful but wish I had, especially since DeCarava, in The Sound I Saw, had very consciously explored the question that interested me. Webster is cuddling him—Coltrane!—with such rough tenderness. There it is: tradition in jazz condensed into a single picture. I still love it—it’s so intimate and telling—even though DeCarava turned out to be impossible about having his pictures reproduced in The Ongoing Moment. That’s a subject—the right to reproduce images—I’m sure we’ll want to come back to. Anyway, my knowledge of photography was still very scanty in the early 1990s. I remember going to dinner at John Berger’s place in the Paris suburbs in 1991. Cartier- Bresson was there. The name rang some kind of bell but I wasn’t sure if he was a film director or a maker of watches. In 1997 I was invited to the Center for Documentary Studies in Durham, North Carolina, to help work on a book of photographs by William Gedney that Margaret Sartor was putting together. That’s when I became aware of how incredibly ignorant I was about the history of photography and began to study it in a far more thorough way. Perhaps appropriately that’s when and where I first read your book Diana & Nikon. I only read Szarkowski much later, by which time I had a sense of what a huge figure he was. I read and reviewed his Atget book—the one with a picture on one page and a few paragraphs of text on the facing page—which I think is one of the great books about photography and a beautiful work of art. (Incidentally, I hope I won’t go to my grave without having done a similar kind of book—picture on verso page, text on recto or vice versa—myself.) He saw the review and sent me a signed copy of his book Mr. Bristol’s Barn. Obviously that’s something I treasure. Anyway, going back to what I said at the beginning, I’d be very interested to hear what Berger, Barthes, and Sontag—each of them— meant to you.

JM: I had to smile when I read your reply to my question. Aperture could not have brought together two people who are more apart in their relationship to photography than we are. Berger’s, Barthes’s, and Sontag’s writings on photography have meant almost nothing to me. I struggled and failed to grasp Barthes’s and Berger’s thought, and while I could understand Sontag’s, with a few exceptions (the Leni Riefenstahl piece, for example), I found her interests remote from mine.

The house of photography has many mansions, and you and I live in different parts of the building. You are on a high floor with a large view while I am in the garden apartment. The first publisher of Diana & Nikon gave the collection the rather clumsy subtitle “Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography.” But what he had in mind was to distinguish my approach from Sontag’s. These are conceptual writers, while I am—I don’t know—someone who is better equipped to look at pictures than to think about what photography is.

So what are we going to talk about—aircraft carriers perhaps? I read your piece in the New Yorker about your experiences aboard one of those amazing vessels with the most enormous pleasure and admiration. I have been interested in aircraft carriers ever since I read a book called We Captured a U-Boat by Rear Admiral Daniel V. Gallery, in which an aircraft carrier called the Guadalcanal subdues a German submarine and tows it 1,700 miles back to America. The submarine is now in a museum in Chicago. Did you read this book in preparation for your project? I’m not sure why, but I think aircraft carriers will help get us over our impasse re: photography.

(Conversation continues.)

Read the full conversation in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014, “Lit.”

The post Geoff Dyer & Janet Malcolm on Photography and Writing appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers