Aperture's Blog, page 169

December 10, 2014

Drew Sawyer: Morgan Fisher’s Melancholic Modernism

Morgan Fisher, Lumière Alticolor Lumière du Jour 106 July 1956, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Ilford FP3 120 December 1959, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

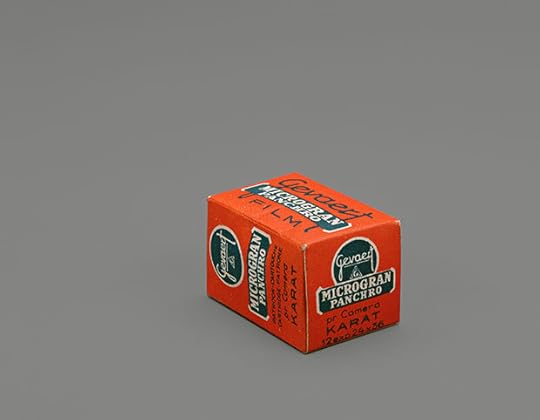

Morgan Fisher, Gevaert Microgran Panchro 24 x 36 October 1951, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Dufay Ortho Y20 B.S. Size 3 January 1954, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

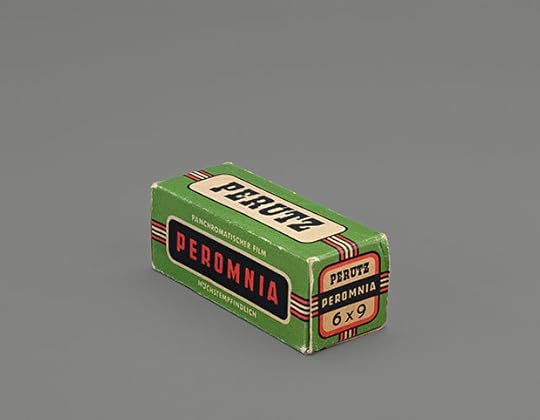

Morgan Fisher, Perutz Peromnia 6 x 9 April 1955, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Agfacolor Negativfilm K 24 x 36 mm August 1955, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Adox R14 120 July 1958, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

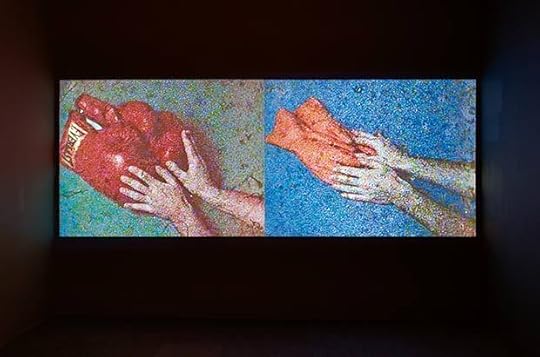

Morgan Fisher, Red Boxing Gloves / Orange Kitchen Gloves, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

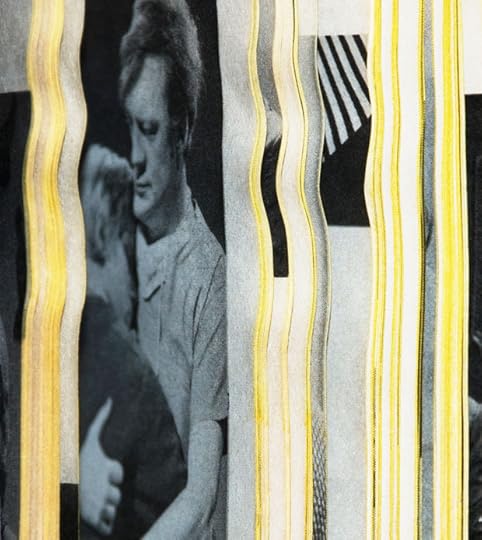

Morgan Fisher, Production Footage, 1971, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Production Footage, 1971, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Morgan Fisher, Production Footage, 1971, 2014. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

From his structural films in the 1960s through the 1980s to his monochrome paintings begun in the 1990s, Santa Monica–based artist Morgan Fisher has consistently and intelligently deconstructed the machinery of representation. For a new body of work on view at Maureen Paley in London and his first solo exhibition, titled “Past Present, Present Past,” the artist turns his attention to the dashed hopes of photography at mid-twentieth century. Twelve photographs document unopened boxes of rolls of film by European manufacturers from the 1950s, the decade in which he both grew up and became aware of photography and its history. Also using film, Fisher shot each unused box, with its bold color and graphics, against a gray background that simultaneously recalls the detachment of commercial photography and the cool aesthetics of Pop and Minimalist art. The repetition of subject matter and formal strategies shifts the viewer’s attention away from authorship to consider systems of production and technological obsolescence. The photographs, according to Fisher, “are examples of waste, things that have gone unused and are now useless, specific signs of what more generally we can call oblivion.”

Fisher and the gallery juxtapose the photographs with two early films, Production Footage (1971) and Red Boxing Gloves / Orange Kitchen Gloves (1980), respectively shot on 16mm film and Polavision. They demonstrate the artist’s early interest in camera equipment and structures as well as his own changing relationship to outmoded technologies. Working as an editor in the commercial film industry led to Fisher’s deep interest in dissecting the systems of cinema, from its physical materials to moviemaking production methods. Production Footage, for example, records the use of two cameras, one an archetypal black-and-white film Hollywood studio camera on a dolly and the other a small handheld camera using color film, in addition to the type of image that each of them produces.

While much of Fisher’s art relies on acts of impersonalization that remove intentional markers and subjectivity, his works often derive from autobiographical sources. In 2013, the artist produced a series of monochrome paintings based on paint chips in Exterior and Interior Color Beauty, a 1935 booklet by General Houses, Inc., a prefabricated house manufacturer founded by his father, Howard T. Fisher. The canvases originate in found materials that at once reference the artist’s childhood, the history of modernism, and the production of images—here, the ideal middle class home. The photographs of expired film boxes similarly memorialize the artist’s childhood and father, also an accomplished photographer, who introduced him to the medium as a boy.

For over a decade Fisher has been producing work that examines now-vanished photographic cultures. In 2011, he produced a similar body of work that documented film boxes produced in the United States in the 1950s. First exhibited at Bortolami Gallery in New York, the photographs were shown alongside a series of pencil rubbings made from 1950’s embossed covers of the conservative British photography annual Photograms of the Year, which his father had in his library. In 2002, Fisher also produced tracings of advertisements in the now long-defunct journal US Camera Annual. The line drawings of the aspirational pictures and slogans heighten and commemorate the naivety of amateur photographic cultures and postwar middle class dreams while also referencing the camera lucida, an optical device that refracted a section of a landscape view on to paper, which photography rendered archaic.

“In the most general sense,” Fisher says, “what underpins these bodies of work is anxiety about what the passing of time will have to say to our ambitions and hopes, earnest and in good faith though we may be. And how quickly and irrevocably what had once been the present becomes the past and with it oblivion.” Fisher’s photographs present relics that reflect on both old and new systems of image production, distribution, and consumption. Ultimately they reveal, as the artist has stated, “the power of obsolescence to disturb.”

“Past Present, Present Past” is on view at Maureen Paley in London through January 25.

_____

Drew Sawyer, an art historian and curator, is currently Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The post Drew Sawyer: Morgan Fisher’s Melancholic Modernism appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Erica Baum: Wordplay

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014, “Lit.” Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Introduction by Nat Trotman

Erica Baum is fascinated by the printed word. Whether scavenging newspaper clippings, vintage paperbacks, or half- cleaned chalkboards, she reveals unexpected poetry in the language that permeates everyday life. She approaches these materials almost scientifically, creating discrete but concurrent series of images that straightforwardly document their sources. Conjuring her objects of study through fragmentary details, shot in close-up and with shallow depth of field, Baum evokes an intimate space in which viewers can decipher the images according to their own associations and memories. Her works accentuate this character by highlighting manifestations of language marked by obsolescence, such as lyrics appearing on player–piano rolls. The Card Catalogue series pictures its eponymous subject in extreme detail, focusing on just a few subject markers amid rows of index cards bearing information related to those topics. In Baum’s hands these headings seem to hover against an abstract visual field, like ghostly relics of a pre-digital era— a point made all the more succinctly in her topic selection for Untitled (Apparitions) (1997).

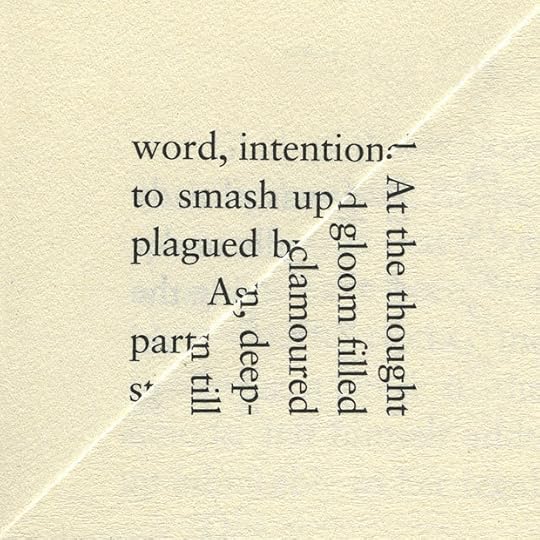

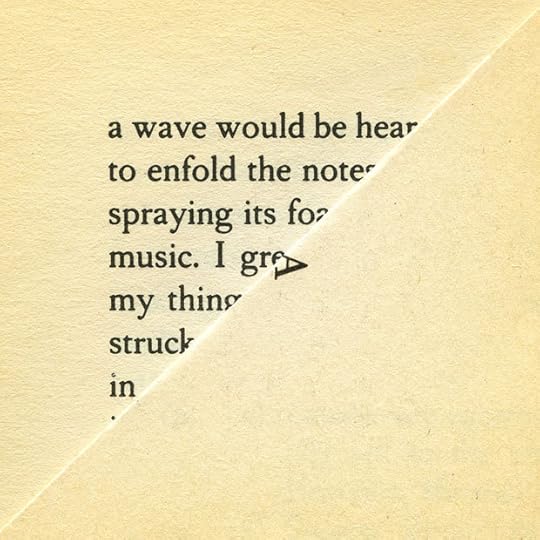

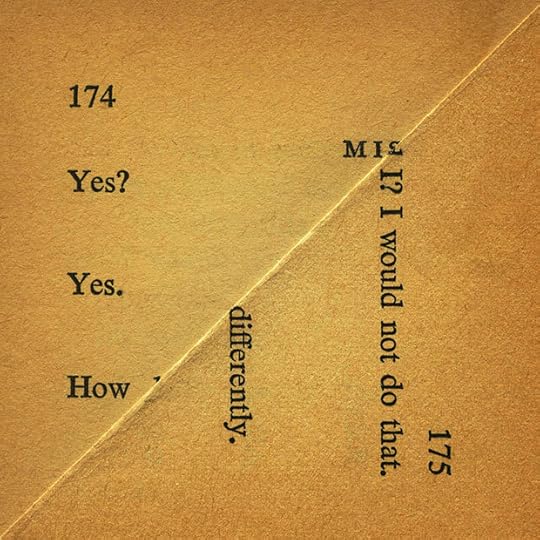

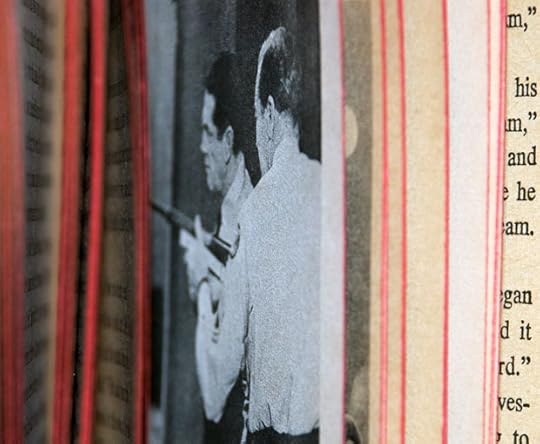

An admirer of concrete poetry, Baum takes up Brion Gysin’s exhortation that “words have a vitality of their own and you or anybody can make them gush into action.” Photography provides a means for her to combine the chance effects of Gysin’s cut-up method with her own reverence for the materiality of the printed page. In the Dog Ear series she ingeniously fuses these verbal and visual qualities by photographing the folded corners of book pages. Works like Differently (2009) and Enfold (2013) draw attention to the physical layout of margins, page numbers, line spacing, and font design while transforming their found texts into syncopated blocks of signification in potentia. The regular folds that cut diagonals across each square frame recall the formal rigor of Minimalism even as they reference the more subjective act of marking significant passages in old books. Baum draws out the luscious physicality of these common objects: the various textures of woven paper, the yellowing tones of age, the hint of ink bleeding through thin pages.

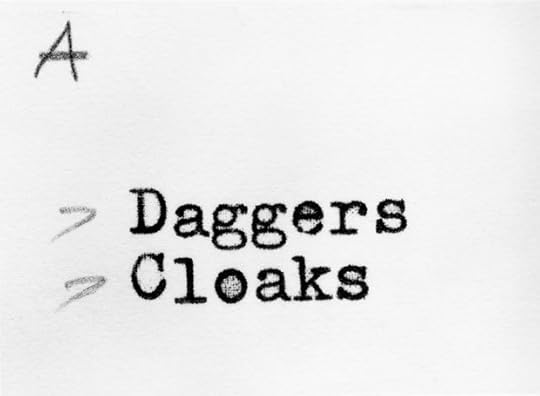

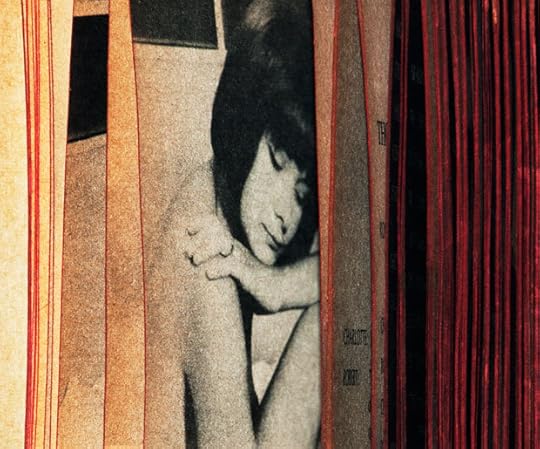

In the Naked Eye series, Baum photographs old softcovers from the side, choosing to show their pages rather than the spines, and fanning the pages out to create mysterious chance juxtapositions. Words appear sliced or foreshortened, giving way to flattened strips of images—film starlets, clouds, fragments of buildings—that, as in Amnesia (2009), are sandwiched between the rippling and vividly dyed edges of surrounding pages. Bereft of caption and context, these illustrations take over the role of displaced signifier previously held by catalog keywords like daggers and cloaks. Digging through old books on cinema for works like Flint (2009) and Clara (2013), Baum selects anonymous figures who either cast oblique glances off the frame of the page or seem poised for the gaze. Leaving their narratives necessarily unresolved, she spins a web of longing that resonates with her own attraction to the source material. Through these open-ended investigations Baum honors the tradition of print—that textured, tangible objectification of language that inexorably fades with each passing year.

Erica Baum, Untitled (Apparitions), 1997, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Untitled (Daggers Cloaks), 1998, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Word Intention, 2014, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Enfold, 2013, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Differently, 2009, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Clara, 2013, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Amnesia, 2009, courtesy Bureau, New York

Erica Baum, Flint, 2009, courtesy Bureau, New York

_____

Nat Trotman is an associate curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The post Erica Baum: Wordplay appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 7, 2014

Mary Ellen Mark: Developing Personal Projects

Mary Ellen Mark, “Rat” and Mike with a gun, Seattle, Washington, 1983

Join Mary Ellen Mark for this workshop designed to help photographers develop and sustain individual personal projects. Mark has produced nineteen books, including three (Streetwise, American Odyssey, and Twins) with Aperture, with whom she is currently working on two additional books. Since she started to photograph in the 1960s, the whole process of creating, maintaining, and bringing personal projects to completion has changed enormously. It is much more difficult now, as there are no longer the same support mechanisms there were when Mark began as a photographer. For instance, magazines used to be one of the resources and outlets for her production of personal work; that’s no longer possible. Today, one must be much more resourceful to complete a project and, hopefully, produce a book. In this workshop, Mark will advise how each student might proceed to achieve the highest photographic potential of their work.

Each student should bring work-in-progress to the workshop—either the beginnings of a project, or work they feel leads to another project they wish to start. Following an open critique, Mark and the class will discuss how each person might best move forward with their projects.

Mary Ellen Mark has achieved worldwide visibility through her numerous books, exhibitions, and editorial magazine work. She has published photo-essays and portraits in publications such as the New Yorker, LIFE, and the New York Times Magazine. Mark has received several awards, including the Cornell Capa Award; Infinity Award for Photojournalism; Dr. Erich Salomon Award; Sony World Photography Awards’ Outstanding Contribution to Photography; Victor Hasselblad Cover Award; two Robert F. Kennedy Awards; and the Creative Arts Award Citation for Photography at Brandeis University. She was presented with two honorary Doctorates of Fine Arts from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of the Arts, Philadelphia. She has received three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and is the recipient of the Erna & Victor Hasselblad Foundation Grant, Walter Annenberg Grant, and John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship. She also acted as the associate producer of the major motion picture American Heart (1992), directed by Martin Bell.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture members at the Dual/Friend level and above)

herRegister here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Mary Ellen Mark: Developing Personal Projects appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 6, 2014

Todd Hido: Sources and Influences

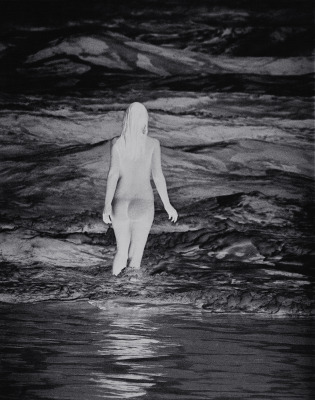

#11374-8145, 2014 © Todd Hido courtesy Rose Gallery

“Part of being a photographer is noticing surface details and how they represent something larger; it’s like being a detective or psychologist.” —from Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude (Aperture, 2014)

Nocturnal illumination, weather phenomena, and differing temperatures of electric light lend an eerie quality to Todd Hido’s unique landscape photographs. Join Hido as he shares his expertise in a weekend workshop for artists and documentarians alike. The course will cover the experiences, strategies, and influences that form and shape a photographer’s career. He will candidly present his own work and provide answers to the elusive questions all photographers ask themselves: Where does my work come from? What does it say? How can I express myself more effectively?

Included in the workshop will be a portfolio review where each student will receive personalized feedback and tasks for improvement. Students will also study the precedent set by other photographers as a rich source of inspiration. The workshop’s main objective is to provide students with a framework for intuitive self-discovery and the merging of one’s practice and one’s everyday life. Lunch will be served both days.

Todd Hido (born in Kent, Ohio, 1968) is a San Francisco Bay Area–based artist whose work has been featured in Artforum, New York Times Magazine, Eyemazing, Metropolis, the Face, I-D, and Vanity Fair. His photographs are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Museum, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among other institutions. He has published more than a dozen books, including Excerpts from Silver Meadows (2013). Hido earned a BFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, Boston, and an MFA from the California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California, and is an adjunct professor at the California College of Art, San Francisco.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture members at the Dual/Friend level and above)

herRegister here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Todd Hido: Sources and Influences appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 5, 2014

The Call for Entries for the 2015 Portfolio Prize is Now Closed!

Thanks to all who entered! Stay tuned for the announcement of our winner and runners-up in March 2015.

The post The Call for Entries for the 2015 Portfolio Prize is Now Closed! appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Erwin Olaf: Volume II (video)

Erwin Olaf’s approach to storytelling is enticingly ambiguous. Erwin Olaf: Volume II is a presentation of his most recent work, through which he expands on his established style of highly polished and stylized color studio images. This new volume showcases Olaf at the height of his powers as an artisan of atmosphere and a craftsman who uses high polish to both perverse and seductive effect. Here, Olaf gives us a virtual tour of the series included in Erwin Olaf: Volume II, and gives insight on his thought process and inspiration for each.

Erwin Olaf: Volume II

Erwin Olaf: Volume II $65.00

The post Erwin Olaf: Volume II (video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 3, 2014

Workshop Instructor Profile: Elinor Carucci (Video)

We sat down with photographer and instructor Elinor Carucci on November 1 to discuss her two-part workshop at Aperture Foundation, “Finding the Universal in Photographic Narratives”. The workshop reflected what motivates Carucci both as a photographer and as an educator. Spanning two weekends, the workshop led students to discuss the concepts and elements of personal narrative within their images, along with ideas and suggestions for how to make compelling edits and intriguing image sequences. Four weeks after the first meeting, Carucci gathered with students to view their new work, encouraging them to listen to their work, and allow it to grow.

“Elinor is a great photographer and a warm person who can look at your work with a critical eye while also being supportive.”

“You will be spending time with a master. There is much to learn even beyond your own work.”

—Workshop participants

The post Workshop Instructor Profile: Elinor Carucci (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 2, 2014

Anne Collier at MCA Chicago

Anne Collier, Developing Tray #2 (Grey), 2009. Courtesy the artist; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Corvi-Mora, London; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles.

Anne Collier, Negative (California), 2013. Courtesy the artist; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Corvi-Mora, London; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles.

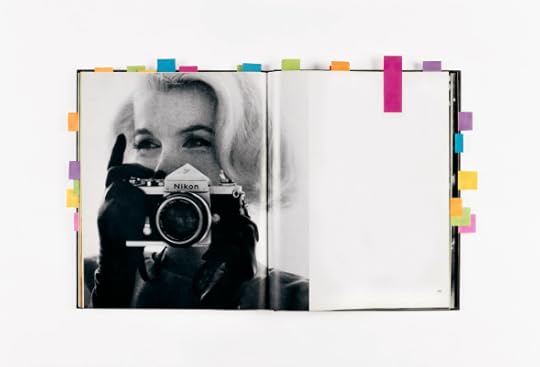

Double Marilyn, 2007. Chromogenic print. Collection of Dean Valentine, Los Angeles.

Cut (Color), 2009. Chromogenic print. Collection of Pauline Karpidas, New York

Untitled (This Charming Man), 2009. Chromogenic print. Collection of Anton Kern, New York.

8 x 10 (Lynda), 2007. Chromogenic print. Courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Anne Collier, Open Book #7 (Light Years), 2011. Courtesy the artist; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Corvi-Mora, London; Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles.

Woman With A Camera (The Last Sitting, Bert Stern), 2009. Chromogenic print. Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg.

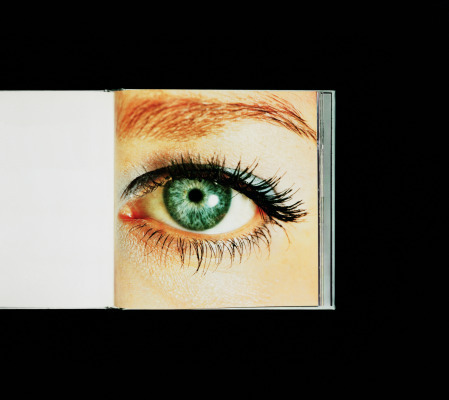

Eye (Enlargement of Color Negative), 2007. Chromogenic print. Collection of Randy Slifka, New York.

Last week Anne Collier’s solo show opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the photographer’s first major museum exhibition, surveying her work since 2002. In Collier’s work, the camera itself becomes an object that must be examined through photographs, often leading her to photograph photographs, whether they are her own or from others. She often isolates commercial images to point out their sublimated politics. Her longstanding “Woman with a Camera” series reverses our gaze on ad-happy models or recognizable actresses like Cheryl Tiegs posing with cameras. By making these images the still-life subjects of photographs, Collier forces us to reconsider who is looking at whom as well as confound the object and the observer. She makes sly use of visual language by allusion, as in her image Cut, a photographic representation of the notorious eye-slicing scene of Un Chien Andalou: a photograph of the photographer’s eye is bisected whilst trapped in a paper cutter. In her recurring images of eyes, often also presented as photographs of photographs, she places the act of seeing at the forefront of her work, in a kind of Russian-doll effect. The exhibition, which runs through March 8, 2015, is aptly titled Anne Collier, in the same self-reflexive impulse that characterizes her photographs.

The post Anne Collier at MCA Chicago appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Deadline Extended for the 2015 Portfolio Prize!

The call for entries for the 2015 Portfolio Prize has been extended to Friday, December 5.

The post Deadline Extended for the 2015 Portfolio Prize! appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 25, 2014

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family (Video)

We sat down with LaToya Ruby Frazier to discuss the realization of her first book, The Notion of Family, which offers an incisive exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania.

More than 12 years in the making, the work compellingly sets a story of three generations—her Grandma Ruby, her mother, and herself—against larger questions of civic belonging and responsibility. Since beginning the work as a teenager, Frazier has enlisted the participation of her family—and her mother in particular. These images acknowledge and expand upon the traditions of classic black-and-white documentary photography, and are themselves transformative acts, resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives, both for those of her family and those of the community at large.

The Notion of Family

The Notion of Family $60.00

The post LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers