Aperture's Blog, page 172

November 5, 2014

Fashion Film & the Photographic by Marketa Uhlirova

Still from Inez & Vinoodh fashion film with Daria Werbowy for Vogue Paris, 2012

Still from Jean-François Carly, I Feel for

Raf Simons, 2005

Still from John Maybury film for Alexander McQueen Autumn/Winter 2013 collection, 2013

Still from Experiments in Advertising: The Films of Erwin Blumenfeld (1958–64), edited by filmmaker Adam Mufti and sound designer Olivier Alary, 2006

Still from Pierre Debusschere, Holy Flowers, 2012

From Bob Richardson, Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, and Deborah Turbeville to Steven Meisel, Glen Luchford, and others, fashion photographers in the past few decades have often emulated the aesthetics of cinema. They have pictured carefully constructed and dramatically lit scenes that brim with narrative potential or, more directly, quote mise-en-scène drawn from the vast reservoir of the movies. This type of photography is, not surprisingly, described as “cinematic.” But what if we flip this familiar concept of the “cinematic” fashion photograph to make a reverse claim: that some recent fashion film, a newly prominent type of fashion image, has curiously dwelled on the “photographic”? In fact, could it be that the fashion film has, more than any other form of the moving image, a proclivity to reside in, gravitate toward, or at least somehow hover around photography?

This may sound odd because, surely, the initial stimulus of its makers was the opposite—to escape the confines of the photographic medium. Take Erwin Blumenfeld, who, in the late 1950s, began to experiment with film chiefly to extend the scope of his work in fashion photography. His desire was to set into motion the traditionally static form—very much in an echo of the primary impulse of early cinema to “animate photographs”—and outline a new visual language for fashion by introducing movement and time. While the recent fashion filmmakers were spurred on by such motivations, it is worth stressing that, like Blumenfeld, they have also transposed onto film what were essentially photographic problems and conventions, by holding onto processes, structures, and concerns specific to fashion photography.

Although fashion film assimilates a number of diverse film genres and forms, for the most part it evokes short, intense, non-narrative spectacles dedicated to the display and promotion of fashion. It is perhaps best characterized as a rhythmic fusion of visual and aural effects, somewhat similar to the music video. As a form of moving image, it is certainly not new, for it had appeared in different mutations since the beginnings of cinema (consider fashion commercials, newsreel and cine-magazine pieces, or various hybrids of promotional and documentary films). Yet, it had until recently been a form strangely overlooked, even displaced: an unclaimed ground half-lost somewhere between fashion and cinema—two industries with different demands. So it makes sense that when it reemerged from within the fashion community during the aughts, it “arrived” with unprecedented vigor. This rejuvenation has evidently been enabled by the “digital revolution,” especially in the new millennium, which has seen an intensified encounter between new media and technologies on the one hand, and fashion image makers and clients keen to explore them on the other.

Dynamic Blooms from Tell No One on Vimeo.

Fashion film has shared photography’s clients, settings, budgets, and, progressively, imaging tools. And it has replicated—at least to a degree—its crews and cast. Many of today’s fashion filmmakers have backgrounds in photography but little or no formal knowledge of film or animation techniques and have generally continued with their previous practice of producing editorials and advertising for print magazines. This hybridization between photography and film has increasingly manifested itself through specific projects. Nick Knight and Tell No One’s Dynamic Blooms (AnOther magazine/SHOWstudio, 2011), Pierre Debusschere’s Holy Flowers (Dazed Digital, 2012), or Sølve Sundsbø’s The Ever Changing Face of Beauty (W, 2012), for example, all treat the material generated in a single “shoot” as the basis for a published fashion editorial and an online fashion film, simultaneously and with no obvious hierarchy between them. In the same vein, recent advertising campaigns such as Inez & Vinoodh for Yves Saint Laurent’s Autumn/Winter 2010–11 and Steven Meisel for Lanvin’s Spring/Summer 2013 present a seamless continuity between photography and film. This intermedial coexistence feels very real as it has also found its platforms in museum exhibitions, retail and public spaces, and, above all, online fashion magazines and websites. The most important of these has been Nick Knight and Peter Saville’s SHOWstudio, which has since its conception been very specific about the “studio” as a physical space that can amalgamate various creative practices (photography, filmmaking, and so on), while also being a broadcasting station.

Alongside these material and functional connections, there is another way to consider this close alliance between film and photography. It is through fashion’s vital preoccupation with the pose—something that has in fact been a recurrent source of fascination for the cinema. Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (USA, 1957), and Veˇra Chytilová’s Strop (Ceiling, Czechoslovakia, 1962) are two fiction films about fashion that in their portrayal of photo shoots use the freeze-frame or photographic still to provoke a tension between the models’ pose as a process, a choreography unraveling in time, and a final product—a privileged fashion image. By highlighting the moment of the holding of a pose, both expose its intrinsic paradox whereby one must become an immobilized image prior to the fact. (Both films did so with a different purpose: Funny Face elevates the frozen moment as the ideal image whereas Strop draws attention to its falsity.)

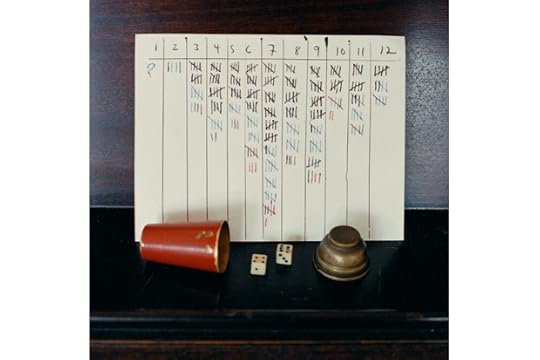

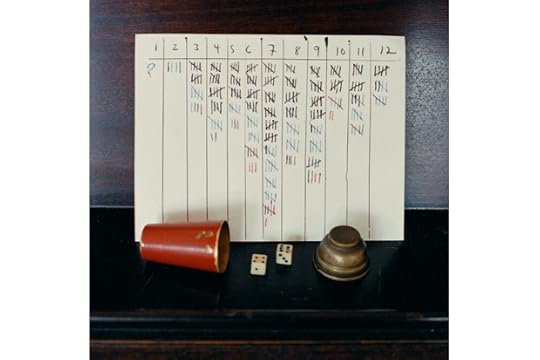

In a similar, if less ideological, manner, a distinct group of early fashion films associated with SHOWstudio explore the deceptive borderline between photographic stillness and filmic illusion of stillness. For example, Shelley Fox 14 (Shelley Fox and SHOWstudio, 2002) and Maison Martin Margiela A/W 2004–05 (Nigel Bennett, 2004) both arrange sets or sequences of still photographs into a temporal experience. Two other early SHOWstudio films, Jean-François Carly’s I Feel (2005) and Knight’s Sleep (2001) approximate photographs in the way their subjects are statically framed and portrayed as ostensibly inactive. Carly’s film shows a string of young male subjects standing in front of a white sheet, facing the camera in a way that is reminiscent of Warhol’s Screen Tests. The screen is split into two, with each pair of portraits showing the same boy, one dressed in his own clothes, the other in Raf Simons. The juxtapositions are accompanied by sparse comments in which the boys state how they feel as their newly fashioned selves, bringing into focus the transformative potential of clothes. In another nod to Warhol, Knight’s Sleep was first staged as a “live photo shoot” portraying nine models while they slept in their hotel rooms. Initially filmed by webcams and streamed via SHOWstudio, the footage of Sleep was subsequently turned into nine short films that speed up the non-action by applying a time-lapse effect. The edited films reintroduce movement, spotlighting the lyrically mutating draperies of the models’ flimsy dresses.

I Feel Pal by Jean-François Carly from Visual Art Services on Vimeo.

The attachment to the photographic seen in SHOWstudio’s early films also permeates a number of other, different strands of the fashion film: Inez & Vinoodh’s campaign for Yves Saint Laurent Autumn/Winter 2010–11 shows a simple event of a model descending a staircase and walking past the camera, very much in the style of early Lumière films. The model’s descent is not, however, captured as fluid motion but rather as a broken and disjointed sequence of slow-motion shots displaying an array of outfits. Yang Fudong’s campaign First Spring for Prada Spring/Summer 2010 inserts deliberately stilled or decelerated shots into otherwise dynamic street and interior scenes. Steven Klein’s Time Capsule series (2011) are pared-down filmic continuations (in black-and-white) of the very (color) images that make up the photographer’s editorial for W.

Why, then, this insistence on stillness and restricted expression in so many fashion films? Perhaps there is a sense (articulated by many, most famously Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag) that photographs are ultimately more memorable and impactful than moving images. Or perhaps the prolonged static shots allow for a closer study of shapes, colors, textures, and detail, something that industry clients and consumers may like to see. What is certain, though, is that the growing entanglement of the two media has naturally pushed for a new level of aesthetic and conceptual dialogue between them. In this relation, film is not necessarily an extension of photography, but rather, each medium is an extension of the other.

_____

Marketa Uhlirova is director and curator of the Fashion in Film festival and a research fellow at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London. She is the editor, most recently, of Birds of Paradise: Costume as Cinematic Spectacle (Koenig Books, 2013).

The post Fashion Film & the Photographic by Marketa Uhlirova appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 4, 2014

Vicki Goldberg: Russian Photography Looks at the Past

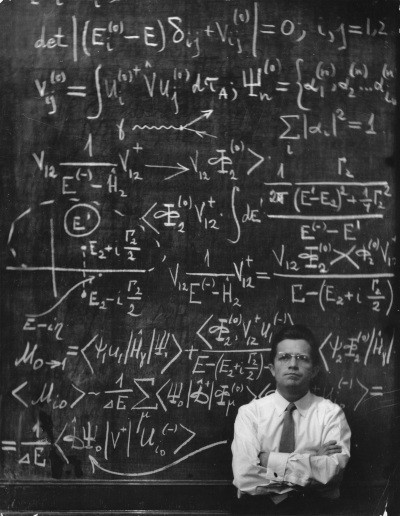

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Biophysics Moscow region, town of Pushchino,' 1974-1976. MAMM collection.

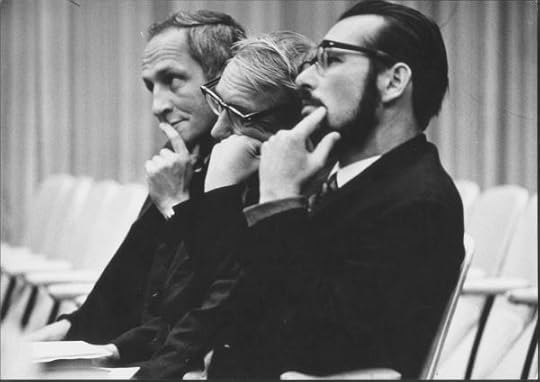

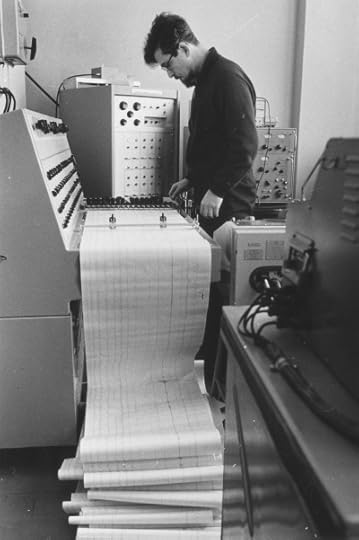

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'Vladimir Safronov, engineer of apparatus for cultivating algae (chlorella) USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Biophysics Moscow region, town of Pushchino,' 1974. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, from the series "Moscow University" 'The university at night,' 1964. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, from the series "Moscow University." 'Academician P. S. Alexandrov,' 1964. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, from the series "Moscow University." 'Duel,' 1963. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, "Untitiled," 1970s. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'Research session to determine the influence of perceptual conflict on short-term visual memory. Emotional memory laboratory. USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Biophysics Moscow region, town of Pushchino,' 1974-1976. MAMM collection

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'Assembly of the Mirabelle hydrogen bubble chamber Moscow region, town of Protvino,' 1971-1974. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'Pulse generator of elementary particles at the Institute for High Energy Physics in Protvino,' 1980s. MAMM collection.

Vsevolod Tarasevich, 'Candidate of Medical Sciences Igor Podolsky checks the progress of an experiment on electrophysiological equipment for researching conditioned reflexes in animals. Emotional memory laboratory, USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Biophysics, Moscow region, town of Pushchino,' 1974-1976. MAMM collection.

In 2013, writer Vicki Goldberg traveled to Russia and Ukraine, where she examined postwar and contemporary visual imagery that illuminates life under and after communism. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we publish Goldberg’s three-part diary, which looks to photography from the Soviet era and today. In part one, Goldberg considers USSR propaganda photography of the 1970s.

Part 1: Russian Photography Looks at the Past

The past is irretrievable but may be revisited in bits and pieces through memory, literature, histories, and other means– prominent among them photography. The summer of 2013, when I was in Moscow, several of the photographs and exhibitions I saw were engaged in a lively dialogue with the history, art, and photography of the Russian past. Sometimes this amounted to an homage to the notion that ‘we are dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants’ and can only move forward if we admit our debt, sometimes it was a program to retrieve visual shards of the nation’s past. In either case, the camera performed one of its cleverest and most common tricks: helping people remember a time they never knew.

Soviet photography had a demanding leader, and his name was officialdom. For a very long time, photography belonged to the state; the aim, often clearly stated and always understood, was propaganda; and the authorities, from generation to generation, demanded that all negatives revert to the state. Olga Sviblova, who founded and directs the Multimedia Art Museum of Moscow (formerly the Moscow House of Photography), told the New York Times in 2010 that in France in 1991 she saw, for the first time, Soviet photographs that had been censored in her own country.

“At the time a new Russia was starting and we were a country without any kind of visual history,” Sviblova said. “I realized without history you cannot look into the future.” (May 28, 2010) The experience spurred her to collect historical photographs, which resulted in such exhibitions as “Time Formula,” a June 2013 show of Vsevolod Tarasevich’s photographs curated by Olga Annanurova as part of several exhibitions of “The History of Russia in Photographs”.

From the late 1950s to the mid 1970s Tarasevich was a well-known photojournalist whose pictures of Moscow University and of scientists all over the Soviet Union were widely published in a magazine called Soviet Life. The images on view generally looked like blow-ups of 35mm, some of them grainy, some candid, some dramatically lit, even back lit, a few softly romantic, the scientists’ portraits nicely done and nicely varied, everything well enough seen and composed to stand beside most of Life and Look at the time. The few examples of the magazine on view revealed a splendidly executed journal, the contrasts sharper and more telling than in American magazines. The photographs often occupied a whole page or three quarters of a double page, while the text was merely a fillip.

Every issue and picture served a propaganda purpose. Soviet Life, like that most beautiful of all magazines, USSR in Construction (1930s), was published for the eyes of foreigners interested in “everyday life in the USSR” as the Soviets selectively presented it. (Never underestimate the selective capacity of a viewfinder, an editor, or a repressive government.) The Russian embassy in Washington distributed 30,000 copies of Soviet Life every month. Tarasovich’s photographs of Soviet scientists and science centers were propaganda that this area of Soviet achievement well deserved, since the USSR had one scientific triumph after another during this period: Sputnik, Yuri Gagarin (the first man in orbit), others who went into space, and Nobel prizes for seven Soviet physicists. According to the wall text, scientists, physicists first of all, were the heroes of “an epoch in which knowledge and achievement were more important than material rewards.”

Another aspect of these years was richly on display at the Lumiere Brothers Center for Photography, which previously exhibited photographs of Moscow from the first half of the twentieth century and in 2013 concluded their program of “Moscow Stories” with images of the city by the forgotten photojournalists of the 1950s to the 1980s. (The curators Irina Chmyreva and Evgeny Berezner introduced me to the gallery, its director, and other photographers.) Photojournalists who had been famous for decades were subsequently erased from memory by the years, and Edward Litvinsky and his wife, Natasha Grigorieva, who together founded Lumiere, spent seven years resurrecting upwards of one hundred photographers. They went to the photographers’ homes, asked to see their work, and found, despite the state’s lock on negatives, large bags of jumbled negatives and prints. Evgeny Berezner told me flatly that the Soviet Union was a double-faced country, every person in it being necessarily double-faced and every photographer making a double of each photograph – one negative for the authorities, one, secretly, for the photographer. The carelessly bagged photographs the couple found had been unopened for years because no one was interested– until Litvinsky and Grigorieva were.

Their large exhibition displayed Moscow soon after Stalin, when there was a slight easing up, and in the later years when cracks in the system began to open up but had not yet grown quite wide enough to step through. Moscow was depicted in a good light to be sure – it was not until late in this period that it was possible to take unofficial photography– but a Moscow younger people neither knew nor remembered and that they flocked to the gallery to see. There were pictures of Khrushchev and Gagarin, of missiles muscling through Red Square on Victory Day, and street photography of children playing in older sections of the city with nary an ad on buildings that today are plastered with them. Most of this was in black and white, all of it on film, all of it highly competent in a rather classical, photojournalistic vein. There were no forays into Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand or Gene Smith territory (probably unknown then), but reporting that would have been welcome in most American and European magazines. Authoritarian governments, of course, do not lack for talented citizens.

It is odd today to see how few cars there were in the city in the 1950s. Later there were more cars, all of them the Russian manufactured Volgas; today the cars fill the streets like a plague of locusts named Mercedes Benz. Change is inevitable, seeing it is not.

The post Vicki Goldberg: Russian Photography Looks at the Past appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin

Dear PhotoBook Review Reader

You’ll find many of the following pages are guided by one particular idea as a loose organizational frame: the photobook and desire. For those of you who know guest editor Bruno Ceschel as the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy, a curatorial project com- mitted to the celebration and study of the self-published photobook, you may also be aware of SPBH’s id-driven alter ego, Self Publish, Be Naughty, a series of monographs about love, lust, sex, and taboos. It is eclectically promiscuous in its approach to desire and, as is pointed out in The Photobook: A History, Vol. III (Phaidon, 2014), to photog- raphy itself. A giddy, mischievous ethos infuses most of Bruno’s projects, and this one

is no different. His vision is ultimately utopian at its core, in which confession of our desires sets us free and connects us to communities of shared and overlapping interests.

This utopian bent is particularly appropriate as this is also the second time we will be launching the spring issue on the dreamy West Coast, during Paris Photo Los Angeles. Last spring, in issue 004, guest editor Charlotte Cotton gave us a blueprint for intertwining personal experience with intellectual analysis, a challenge which has been consciously picked up by Bruno and many of the contributors selected by him and his team. In “PhotoBook Lust” and other writings in these pages, you will find an unruly garden of thrills and delights, filled with books that can seduce us into taking them home for private enjoyment.

I was especially gratified to have the opportunity to engage Miyako Ishiuchi and Yurie Nagashima in a conversation about the ways the female body has been depicted in Japanese photography—both in their own work and in that of other photographers, some of whom have gained international recognition for their frank, possibly exploitative depictions of the eroticized nude (pages 12–13). Also in this issue, instead of a standard Publisher’s Profile, Bruno has interviewed David Senior, bibliographer of the MoMA Library, about the increasingly blurred lines between publisher, designer, artist, and other once-discrete roles (page 4). In this interview, Senior proposes that one new application of the book form itself is as a self-run artist’s space, particularly as it applies to self-published works.

Finally, I’d like to bring attention to the launch of a new category of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. While it has become a bit of a tru- ism that a “true photobook” is almost exclusively the authorship of an individual artist or editor, it became evident during last year’s jurying process that many excellent contributions to the field decidedly do not fall into the aforementioned framework, as they are focused more on the presentation of scholarship and curatorial thinking. We realized we ought to find a way to recognize these efforts to bring innovation and new knowledge to the world of photobooks. With this in mind, this spring we launch a new, third category of prize: Photography Catalogue of the Year. More details on this can be found at aperture.org/photobookawards.

As always, we thank our guest editor and contributors (of whom there are so many in this issue!), whose ideas and words are the backbone of The PhotoBook Review. The collected wisdom and opinions of so many participants reshaping the landscape of the photobook today are continually inspiring to me, as they hopefully are to you, the PhotoBook Reader, as well.

—LESLEY A. MARTIN

Publisher, The PhotoBook Review and Aperture Foundation book program

The post Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Studio Visit: Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao’s New York (Video)

With painstaking care and the use of multiple exposures, Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao stitches images together to create detail-driven panoramas of the New York City landscape. We visited Liao at his home studio in Queens, NY, where he showed us what’s behind his unique perspective of the city, and took us through his recently published monograph, Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York.

Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York includes photographs taken over the last ten years. From rehabilitated Coney Island to the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, from the demise of Shea Stadium in Queens to the newly built One World Trade Center, Liao has created a lasting document of a significant period of transformation of New York’s skyline and social fabric.

The post Studio Visit: Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao’s New York (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 3, 2014

Anne Wilkes Tucker on Ray K. Metzker (1931-2014)

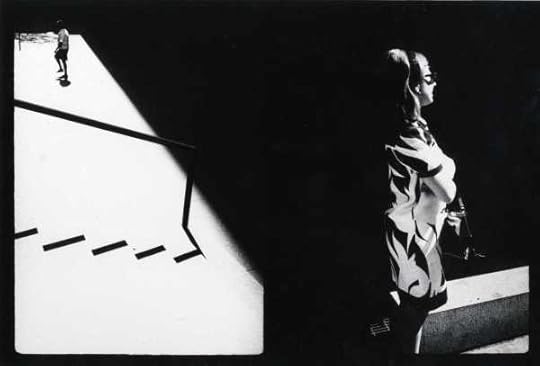

Ray K. Metzger, 'City Whispers, Philadelphia 1983.' All photographs: Estate of Ray K. Metzker, Courtesy Laurence Miller Gallery.

![metzker59CC36[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![metzker59CC36[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415123538i/11729028._SX540_.jpg)

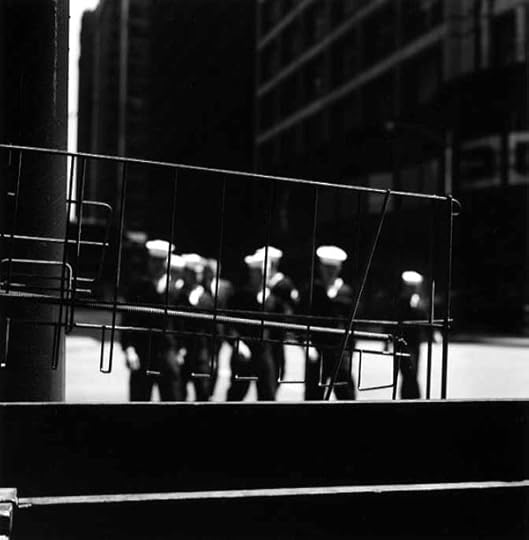

'Chicago 1959.'

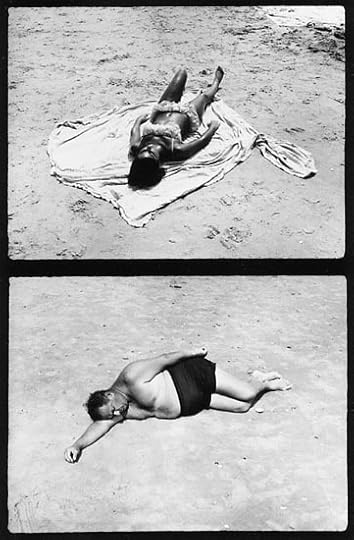

'Couplet, Atlantic, 1968.'

'Pictus Interruptus, 1980.'

'Pictus Interruptus, 1978.'

'Couplet, 1968, NYC'

'Valencia, 1961.'

'City Whispers, Philadelphia, 1981.'

'Autowacky, Philadelphia, 2009.'

![metzker composite (Big Nude) 1966[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![metzker composite (Big Nude) 1966[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415123538i/11729036._SY540_.jpg)

'Composites: Nude, 1966.'

'Chicago 1958.'

'Philadelphia, 1963.'

Few artists can boast five decades of works so consistently exquisite, formally innovative, and intellectually challenging as those made by Ray K. Metzker, as well as a well lived, comtemplative life, rich with friends and family.

Metzker was an attentive teacher whose demands as well as generous encouragements were warmly remembered through social media after his death. Established photographers who only met him once, but early enough in their careers, acknowledged his lasting impact. And I have a similar acknowledgement to make. Unknown Territory: Photography by Ray K. Metzker, 1957-1983, was the first mid-career retrospective that I curated. Ray made the distinction between fun and joy: fun was carefree and irresponsible, a respite from one’s endeavors. (Anyone who saw him smile knew his capacity for fun.) But joy was “full of body, encountered only from intense endeavor.” Our project included plenty of both fun and joy. I temporarily moved to Philadelphia so we could work every day, which was a huge sacrifice for Ray: he was uncomfortable devoting so much time to looking back rather than making new pictures. I slowly realized the complex patterns of his practice, and our exhibition became the first to group and identify his pictures into projects. He devoted himself to the goals we collaboratively defined, thinking through each step, especially the details– every detail. I learned not just about Ray Metzker and his work, but about working.

His career began when as a graduate student at the Institute of Design in Chicago. Studying with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, he produced a photographic series on the Chicago business district that the legendary curator Hugh Edwards selected to exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1959. After that show, Metzker produced two other complete series, and then created his best-known project, Composites (1964-66, resumed through 1984). Composites arose from his realization that a single work could be created from an entire roll of film. Employing bold graphic designs, deep shadows, clean highlights, and repeated motifs to investigate “the possibilities of synthesis,” he mounted his contact strips on boards four feet square or larger. A viewer could find a wealth of everyday information, but had no particular point of entry into the picture, so Metzker used his proclivity for humor and word play to nudge viewers’ perceptions, with titles like Hot Diggidy, Leapin’zz, and A Maze N Philadelphia. John Szarkowski presented the series in a one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967.

Again and again, Metzker would invent formal problems that led to extensive series on subjects as diverse as prone bodies, lush landscapes, pedestrians in skyscraper canyons, and reflections off of cars. His city views convey isolation, longing, and anonymity as well as formal beauty and empathy. In his project Sand Creatures, he followed beachgoers as they carved out their spots, oblivious to whatever this process exposed about their bodies, dreams, or desires. In Pictus Interruptus, he partially blocked the camera’s lens with simple objects, recording both sharp and out-of-focus forms, creating a provocative tension between photographic representation and abstraction.

Like any great artist, he kept returning to ideas and reinventing the ways to present them. Always, he balanced formal solutions with social ideas and tributes to art from many media. Though it may have cost him widespread recognition, he never played to the public or the critics, only to his own vision. He kept his life simple, reserving complexities as an option in his images. His student and later colleague Tom Goodman once asked Metzker how he worked, to which Metzker replied, “One day I would walk out the door and turn to the left; the next day I would turn to the right.”

_____

Since 1976, Anne Wilkes Tucker has been the Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston where she has curated exhibitions ranging from retrospectives such as “Unknown Territory: Photographs by Ray K. Metzker” and “Robert Frank: New York to Nova Scotia ” to historical surveys including “Czech Modernism: 1900-1945,” “This History of Japanese History,” and “WAR/PHOTOGRPAHY: Images of Armed Conflict and its Aftermath.”

The post Anne Wilkes Tucker on Ray K. Metzker (1931-2014) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 30, 2014

LaToya Ruby Frazier in Conversation with Dawoud Bey (Video)

On Wednesday, October 15, Aperture Foundation, in collaboration with the department of photography at Parsons The New School for Design, presented a conversation between photographers LaToya Ruby Frazier and Dawoud Bey, followed by a book signing.

The recipient of a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship, Frazier creates work that offers an incisive exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Her work also considers the impact of that decline on the community and on her family, and creates a statement both personal and truly political: an intervention in the histories and narratives of the region. Frazier and Bey, well-known for his community-based portraiture work, discussed Frazier’s first book, The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2014), and the ideas and issues that inform her practice, along with the ways in which photography can provoke an active conversation in the larger social world.

The post LaToya Ruby Frazier in Conversation with Dawoud Bey (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 29, 2014

‘Picasso and the Camera’ Opens at Gagosian Gallery

Photographer unknown, 'Picasso with Bob (the Great Pyrenees), Château de Boisgeloup, France,' 1932 © Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA). Courtesy Archives Olga Ruiz-Picasso and Gagosian Gallery.

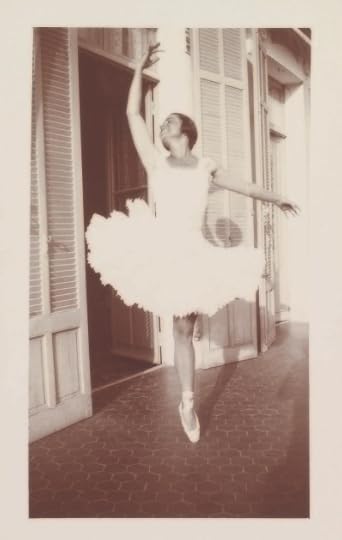

Photographer unknown, Olga Picasso, Villa Belle Rose, Juan-les-Pins, France, summer 1925 © Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA). Courtesy Archives Olga Ruiz-Picasso and Gagosian Gallery.

Pablo Picasso, 'Le réservoir (Horta de Ebro),' 1909. © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Michele Bellot. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

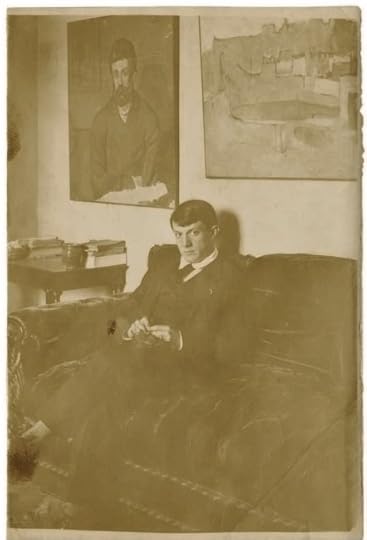

Pablo Picasso, Autoportrait avec Portrait d’homme, 5 bis, rue Schoelcher, Paris, 1915–16 © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Maurice Aeschimann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

A new exhibition at Gagosian Gallery, Picasso and the Camera, curated by Picasso biographer John Richardson, pulls together hundreds of photographs, paintings, and even pieces of furniture that braid together the precise realities of film with the prismatic, painted world of Pablo Picasso. Including never-before-seen archival images, the exhibition traces Picasso’s life through the means of the photograph, drawing from records of his works’ progress to images taken by the women in his life to studio stills by the top photographers of the day (Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Man Ray are just a few who visited). Through this documentation and personal ephemera, these photographs reveal some of Picasso’s most experimental projects as well as his personal life.

Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, grandson of Picasso and his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, organized the exhibition in partnership with the gallery. Snapshots offer fragmented views of the artist’s life—many taken by his first wife and subsequent lovers (and vice versa) on holiday, at home, and at work—and appear on rows sliced by soaring, blown-up images of these figures, reaching the 21st Street gallery’s massive ceiling. But, perhaps most importantly, many of the images offer insight into how Picasso made his work, at a time when artists were just starting to experiment with photography.

“For Picasso, photos were very important in the sense that he was modern—he was not having models in his studio. He would do things by memory or because he had books, newspaper, or photographs, as well as objects that he cherished,” Ruiz-Picasso says.

Many of the images come from Ruiz-Picasso’s grandmother’s archive. In one, the former ballerina stands en pointe, smiling devilishly; adjacent is Picasso’s 1932 painting Le repos (1932), a Cubist imagining of ballet’s fifth position, the dancer bearing a similar grin. (However, the photographer of the original image—most likely Picasso or Khokhlova—is unknown.) Most photographs taken by Picasso were used as studies of work, or as a jumping-off point. One tableaux tracks the progress of a painting in his Montmartre studio from 1908 to 1910; another wall pairs landscape photographs taken by Picasso with the Cubist landscapes they inspired.

“Who was taking those photographs?” Ruiz-Picasso explains of these connections. “We knew that Picasso was taking photographs. We were confident. Only in the 1930s did he ask different photographers like Brassaï to do for him what he was already doing himself.”

A 1922 portrait by Man Ray finds the artist stoic yet relaxed in his Paris studio; Brassaï’s images depict Picasso’s countryside studio filled with sculptures of the 1930s in moody lighting; and in 1944, Cartier-Bresson took a photograph of the artist’s crowded Paris studio—the artist nowhere in sight. Throughout his life, Picasso maintained close, collaborative relationships with a number of photographers, namely Lucien Clergue, Edward Quinn, and André Villers.

Villers and Picasso worked together on a 1962 project in which Picasso’s cutouts of animals, faces, and masks were overlaid on landscape photographs taken by Villers. The thirty works, which span a gallery wall, make for one of the exhibition’s most striking moments, and they appear just as contemporary today as they did when they were made. As Ruiz-Picasso notes, today artists’ lives and practices are constantly being photographed; this expansive show, which runs through January 3, 2015, offers a rare look at one of twentieth-century art’s most monumental figures.

–Alexandra Pechman

The post ‘Picasso and the Camera’ Opens at Gagosian Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 28, 2014

Jason Fulford on Visual Language: How Pictures Speak to Each Other

Jason Fulford, Scranton, PA, 2009

“Everywhere there is a grammatical mysticism. Grammar. It is not only the human being that speaks—the universe also speaks—everything speaks—unending languages.”

—Novalis

The single photograph, despite its specificity, remains ambiguous. The image is always relative to something else: another image, the mode of presentation, text, or the viewer’s own mood and memory. For this reason, context is an important tool for the photographer. Context can be used either to play on the photograph’s inherent ambiguity, or to clarify the photographer’s message. In this hands-on workshop, participants will discuss and experiment with visual language and the relationship between images. On day one, participants engage in a series of games and exercises that will teach them conceptual editing tools using found imagery. On day two, participants will work on their own and each other’s personal work.

In advance of the workshop, participants must send twenty-five found photographs and twenty-five of their own photographs, the latter preferably from a single body of work. Images may be sent to education@aperture.org.

Jason Fulford is a photographer and cofounder of J&L Books. He is a contributing editor to Blind Spot magazine and a frequent lecturer at universities. Monographs of his work include Sunbird (2000), Crushed (2003), Raising Frogs For $$$ (2006), The Mushroom Collector (2010), and Hotel Oracle (2013). He is coeditor with Gregory Halpern of The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014), and coauthor with Tamara Shopsin of the photography book for children This Equals That (Aperture, 2014). Fulford is also a 2014 Guggenheim Fellowship recipient.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

This workshop has been filled. Please click here to explore more workshops. Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Jason Fulford on Visual Language: How Pictures Speak to Each Other appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 27, 2014

Dawoud Bey: The Portrait in a Community Context

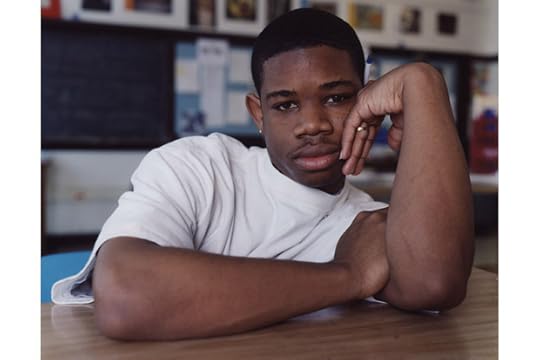

Dawoud Bey, DeMarco, South Shore High School, Chicago, 2003

In Dawoud Bey’s portraits, he depicts both individuals and communities. Through series such as Class Pictures, Character Project, and most recently, The Birmingham Project, Bey explores collective individuality while guiding viewers through social and historical spaces.

Join Bey for a workshop on how to create effective portraits within a community context. The workshop will begin at Aperture, with an introductory review of students’ portfolios. In addition to providing personalized feedback and tasks for improvement, Bey will present his own work and experiences as an artist. The discussion will present conceptual and practical strategies for making new work, followed by a full-day site visit to a church, school, community center, or shelter where students will work directly with subjects to photograph them in the context of their shared environment and community. Students should have a strong working knowledge of their cameras, as well as basic working knowledge of artificial lighting.

Topics for discussion will include:

• What is your interest in the subject(s)?

• What is it you want to say about your subject(s)?

• What is the relationship between the subject(s) and the space you photograph them in?

• How do you establish narrative in the photographic portrait?

• How to collaborate with and direct your subject(s)

• Location setup and lighting: what works and how to do it

Dawoud Bey (born in New York, 1953) began his career as a photographer in 1975 with a series of photographs called Harlem, USA, which was later exhibited in his first one-person exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979. He has since had numerous exhibitions worldwide at such institutions as the Art Institute of Chicago; Barbican Centre in London; Cleveland Museum of Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Detroit Institute of Arts; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; GA; National Portrait Gallery, London; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among many others. The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, organized a mid-career survey of his work, Dawoud Bey: Portraits 1975–1995, which then traveled to institutions throughout the United States and Europe. A major publication of the same title was also published in conjunction with that exhibition. Class Pictures was published by Aperture in 2007, and a traveling exhibition of this work toured to museums throughout the country from 2007 to 2011.

“I like when people look at this picture of me and be like, ‘Oh, he looks like he’ll do something bad like this.’ Some people might be like, ‘Oh, he looks like a bad kid,’ or . . . like, ‘I can picture him beatin’ up somebody or taking something from somebody,’ whereas that’s not me at all. I guess there is a certain look, ’cause I’ve experienced it before. Like, teachers in school, they’re like, ‘Oh, I thought you was a bad kid, but you’re all right,’ you know. ’Cause I like to prove people wrong so I can make me look better in the end. ’Cause as they get to know me, then they’ll see—like I said, I’m a funny person—and they’ll see I’m a funny person.”

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture members at the Dual/Friend level and above)

herRegister here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Dawoud Bey: The Portrait in a Community Context appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Stephen Shore in Conversation with Peter Schjeldahl (Video)

On Tuesday, October 7, Aperture Foundation hosted a conversation with photographer Stephen Shore and acclaimed critic Peter Schjeldahl in conjunction with Shore’s forthcoming book, Stephen Shore: Survey.

The two discussed the work that spans Shore’s impressive and productive career, in light of his first-ever retrospective at Fundación MAPFRE this fall, which includes his series Early Works, Amarillo, New York City, American Surfaces, and Uncommon Places as well as Shore’s significant contributions and influence on photography over the past four decades. Shore and Schjeldahl took questions from the audience following their discussion.

_____

Stephen Shore: Survey

Stephen Shore: Survey $65.00

Add to Cart

The post Stephen Shore in Conversation with Peter Schjeldahl (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers