Aperture's Blog, page 175

September 22, 2014

Emmanuelle Alt: Conversation with Penny Martin

Inez & Vinoodh, Emmanuelle Alt, 2014 © Inez & Vinoodh and courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York, and The Collective Shift

Fashion photography can be a nostalgic business, but Emmanuelle Alt’s appetite for the unexpected and glamorous keeps her in the vanguard of taste. A forty-seven-year-old stylist who learned her trade at French Elle, Alt is celebrated for reinvigorating the industry’s tired ’70s fashion clichés with surprising, sporty modernity since joining its most prestigious magazine, Vogue Paris, as fashion director in 2000.

Taking over from Carine Roitfeld as the publication’s editor-in-chief three years ago has demanded a more global view of making a magazine, shifting Alt’s focus away from styling and aesthetics alone. She may not now enjoy the luxury of being on set with Mario Testino, David Sims,

and Inez & Vinoodh every week, but Alt still has the knack of intuiting exactly what a photographer needs to make a truly great picture. Penny Martin, editor of the women’s title The Gentlewoman, interviewed Alt at the Vogue Paris offices on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré this past May.

Penny Martin: Let’s start in the present. Emmanuelle, tell me about your most recent shoot—how did it come about?

Emmanuelle Alt: I was just in St. Barths with Inez & Vinoodh, shooting for our June/July issue. I’ve known them for about twelve years, so we’ve developed an easy way of working. We all love the same period of photography. And it’s not only the images; it’s the whole culture—a certain time of models, clothes, a certain time in music.

PM: I gather you started off in music videos?

EA: Yes, when I started styling, videos were very important. It was the era of Jean-Paul Goude and Jean-Baptiste Mondino, a totally new medium.

PM: Was this while you were at Elle?

EA: Yeah, I was working as a production assistant at the same time. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a director; I was just fascinated by images, I think. I assisted on some Mondino videos; at that time he was fashion photography’s God. The stylist was Ray Petri. It was a brilliant team.

PM: So that was the golden age for you?

EA: Yes, for me, probably the beginning of the ’80s, the end of the ’70s . . . I think your first music and visual influences stay with you forever. My group all listens to Bowie; there’s nothing better. You live with what was around when you first became curious.

Vogue Paris, December 2013. Cover photograph by Inez & Vinoodh © Inez & Vinoodh/Vogue Paris

PM: When it comes to initiating a shoot, then, are those common influences even mentioned between collaborators of the same age?

EA: Well, this story began with Inez and me exchanging images by e-mail. Sometimes it comes from almost nothing; it might just be a color. When you’re shooting in the sun—you know that strong blue sky in St. Barths—you need a contrast. So I might say, “What do you think about red and white?” And Inez is like, “Oh, yeah, sure!” I’ll send a picture of a red shoe and a René Gruau illustration, which is full of red, and just a silhouette or a little sketch. It’s not always photographs—often it’s a painting or a frame-grab from a YouTube film. Very quickly, we’ll start to build up an image of a woman, and then we can discuss the casting. Some photographers will keep changing their casting or think they need a stronger idea. But Inez isn’t someone who hesitates. It’s like three phone calls and everything is booked.

PM: Do you ever have preproduction meetings with photographers in person?

EA: Unfortunately, everything is done over phone and e-mail since no one is in Paris. Of the bigger photographers we work with, I think Peter Lindbergh is the only one. Besides, at this time of year, we need to shoot overseas for the light. And unless photographers have made a career out of studio photography, like Penn or Avedon, I think most of them get bored if they’ve been stuck in there all year.

PM: The studio is all about control—leaving very little to chance so an idea can be executed exactly as imagined.

EA: Whereas outside you’re looking for accidents. I’m going on a trip with David Sims in a few weeks—once a year we take him on location. For a studio photographer like him, who controls the lighting, everything, he has to face a lot of unexpected things outside. Suddenly, rain makes a fantastic picture or there’s a dog in the street. The only thing is it costs a lot of money to fly photographers and their teams out there. We’re far from the days of Helmut Newton traveling with one assistant, one person doing hair and makeup, the model, and a fashion editor. Five people: it was nothing.

The following first appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of Aperture magazine, “Fashion”. Subscribe here to continue reading.

The post Emmanuelle Alt: Conversation with Penny Martin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 19, 2014

Sebastião Salgado: Genesis

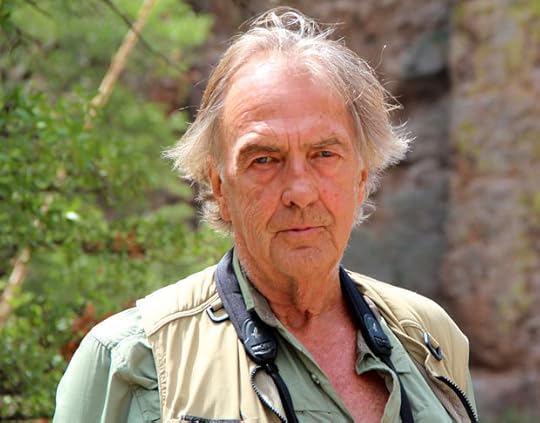

Sebastião Salgado at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

Sebastião Salgado's exhibition Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography.

The timing for the opening of Sebastião Salgado’s eight-years-in-the-making, epic project Genesis, on view at the International Center of Photography from September 19 to January 11, 2015, could not be more ideal or inspiring. With both a UN Climate Summit and a People’s Climate March (expected to include an unprecedented number of participants) also taking place in New York within the next week, Salgado’s exhibition, curated by his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado, is a call to action. Salgado—who has focused on poverty and starvation in his work in the Sahel, child refugees and migrants in The Children (Aperture, 2000), the struggle of the landless peasants in Brazil in Terra (1997), the end of manual labor in Workers (Aperture, 1993), and the displacement of the world’s people at the end of the twentieth century with Migrations (Aperture, 2000)—does not consider himself an activist. Rather, he said to me simply, “I am a photographer. Photography is my life, and my way of life.”

And yes, he is first and foremost a photographer, committed to rendering our quickly evolving world as he experiences it. His view is infused with empathy and a deep engagement with his subject. With Genesis, which was published as a book last year, for the first time he has focused on animals and the landscape, as well as people who are still living as they lived for centuries. In his new book, From My Land to the Planet (2014), Salgado writes of Genesis: “I wanted to recount the dignity and the beauty of life in all its forms and show how we all share the same origins. . . . For me, it has nothing to do with religion, but indicates that harmony in the beginning that enabled the diversification of the species: this miracle of which we are all part.”

Speaking with him for thirty minutes or so during the final stages of the exhibition’s installation, his sense of wonder and his belief in the planet’s resilience resonate passionately. His prognosis for humanity? Well, he’s more circumspect . . . but still hopeful. What follows are a few excerpts from our conversation.

—Melissa Harris, September 17, 2014, New York

Melissa Harris: I’m looking at the reforestation project you and Lélia did in Brazil through your [non-profit organization] Instituto Terra on the land your parents gave you, where you planted over 2.5 million trees and really reestablished the whole ecosystem. Were you thinking about ecosystems with Genesis?

Sebastião Salgado: These are macro ecosystems. These are huge regions of the planet that are, in a sense, with a certain equilibrium. In this section of the show, all this is Africa. Africa we cannot say is just one ecosystem. But it is a macro region of the planet. If you go from one ecosystem to the other, to the other, to the other, it creates a huge movement of ecosystems—and so you understand it in a more macro way. I made nine trips to Africa in order to get these pictures, working from the desert in the south of Africa to the Sahara Desert in the north of Africa, and working in between in Ethiopia, in Zambia, in Botswana, in Namibia . . .

We had another chapter in the north of the planet with an entirely different group of ecosystems, because I worked in the Kamchatka in Russia; worked on Wrangel Island, north of Siberia; worked with the movement of reindeers in the north of Siberia also, in the Yamal Peninsula; worked in the Brooks Range in Alaska; worked in Canada, the border of Canada and Alaska on the Pacific side; worked in the United States in the Colorado Plateau.

MH: What happened to you in this process? Did you experience something you hadn’t experienced before?

SS: Incredible. For me, it was incredible, this thing. I did eight years of trips, eight months a year. I went to thirty-two regions or countries. But the big trip that I did was inside myself. I discovered that I am part of all this, that I am part of the animals. That we are part of everything alive in the planet. We are part of this huge equilibrium. You know? For me, it was the most important thing.

We came out of the planet. We must go back to the planet. And I went back to the planet. I thought before, being human, that I was part of the only rational species. That’s a big lie. Because each species is deeply rational inside its own species. We are all—the mineral species, the vegetable species, the animal species—we are all the same. We have the same life. We are all alive.

Once I was with a scientist here in the United States in this incredible chain of mountains—the Rocky Mountains. The guy tells me, “Sebastião, these are young mountains.” I said, “You are lying; these are billions of years old.” He said, “Yes, but this is the second generation of the Rocky Mountains, because the one that was there before was eroded to the ground zero, and the new one is young because she is growing still.” The Rocky Mountains are still growing! Incredible!

I’ll show you a picture of a mountain in Africa that is two days old. When we were in front of the mountains here, that are billions of years old. In these I discover all that we are . . . we are part of all this. We are not important. We give too much importance to ourselves. The life of this land is as important as we are, and we are part of it. I was astonished. You see, [in this picture] a volcano is going off, and it projected this new material, this new mountain. But I had to keep lifting my feet up and down as I photographed, or my shoes would start to melt.

It was amazing. To see these stones when they have just come out of the oven. It was so amazing. So amazing to discover these things.

And working on Galápagos, that was . . . I can show to you a cactus, one cactus, that you can touch—it has no nails that hit you. So soft. So small. But this cactus, born in the middle of these stones that came out of a volcano which created these lives!

I remember once I was working in Alaska. I was in the Brooks Range. I had a small plane that drove me to a point, and left me there, and came back for me one week or ten days later. Because in Alaska, you cannot fly always. It was June. You have the cold air coming from the Arctic and hot air from inside Alaska, and they meet over this Brooks Range, over this mountain, and it creates a lot of microclimates. In June, I had a lot of snow, a lot of rain—hot, cold, everything happened there. The plane sometimes was forced to leave me there. I’m sitting there all day long in front of the mountain. You are the planet; you are part of all this together. And you see how the wind cuts at these mountains like a knife, and it creates sand that will create soil, and you see all the vegetation, the small vegetation fights to survive. It’s amazing.

You see, that is the important thing. No? Even before, I photographed all one species, and with Genesis I became so open to every other species.

MH: Do you feel differently about Man now?

SS: Completely different about Man. If you consider the history of it: our earth, it started here—the beginning of this wall. At the end of this wall came the animal, then the human. We arrive in the last millimeter here. That’s the important idea. All of this lived before us. All this creation was happening. All these relations, linked to evolution, creating this kind of huge intelligence and evolution that was born from all these things. This for me was fantastic, so great.

MH: Is there still such a thing as “wild,” Sebastião? Is it possible to find something that is pristine and wild?

SS: There are places where no one from Western civilization has gone; there are humans who still live like we lived fifty thousand years before. There are a lot of groups that never made any contact with anyone else. They are the same as us. There is still a percentage of the planet that is in the state of genesis.

MH: That’s extraordinary.

SS: What we think is no more, what has been destroyed, is true—but it is not the whole thing. In the desert, in the Arctic, in the Amazon.

Yes, a good half of the planet—where we built our farms, where we built our agriculture—we destroyed. It’s ecologically destroyed. But a good half is there, and we must hold on to this if we want to survive as a species. Because we are not a danger to the planet; we are a danger to ourselves. It will be the end of our species. Because the moment that we go, the planet renews itself in five hundred years or a thousand years. It’s always done that. The forests come back. The planet can renew quite quickly. It’s not that damaging for the planet. It’s damaging for us. If we want to survive as a species, we must change our behavior.

These chemicals introduced to the planet with war or poison or anything damaging are the chemicals of the planet that we put in concentrated portions through here or through there. But the planet has a capacity to absorb all these things in the long term. Now we live longer lives. And we live outside of nature. We are the only species that has a real consciousness, I believe, that we will be dying. The others just live. And this consciousness that we’ll be dying happens in this modern urbanization. Because when you work with the Indians in the Amazon, they use their body. They have their body to be used. If they cut, they cut. If they break a leg, they break a leg. If they become old, they separate from the others, they go to the forest . . .

If we don’t change our behavior, we’ll disappear very fast. We’ll disappear as a species. You see, we have species that lived for 150 million years. They were much more strong than us. The dinosaurs. They’re gone 100 million years ago. And we are here after a few hundreds of thousands of years, no more than this. We are cutting the trees at a very high speed. They could help save us, and we are destroying the trees.

If we go, there are a lot of species that will go with us. But there are a lot of species that will not go—that will stay. For example, the species inside of the ocean will stay. The process can start again. In billions of years, the humans can come back again.

I believe at least that we must try to go back to the planet, probably not to live more inside the forests—that won’t happen. But we must, at least spiritually, go back into the planet. Feel that we are part of the planet. Add to the beautiful part of the planet, not destroy it. We have money, we have technology; we must have a spiritual comeback to the planet, being part of the planet. If we do this, we can control a majority of the carbon emissions that we have. If you control the quantity of the emissions, we can reduce them. We can use solar energy. We can use the movement of the world, the wind, so many things, to produce energy. We can change our concept of consumption.

MH: Are you sure you’re not an activist?

SS: No, it’s not activism. This is a way of life. It’s different. It’s my life. Activists are putting people in the street. We are planting the trees. I chose the word “genesis” just to say we live here with the beginning of life. That is also the planting—the beginning of life.

MH: Sebastião, was it different to photograph landscape and animals?

SS: You must respect people. You must respect nature. This [photograph of a giant tortoise] was one of my first pictures in Genesis. To make her portrait was at first impossible. She was afraid. In a moment, I was so tired that I put myself on my knees. When I put myself on my knees, by chance, I was at her level and it happened. I lay down. I started to work with her like this [gestures crawling, using his knees and elbows]. She came to me! And I moved back a little bit, to show her that I was respecting the territory, and she was as curious of me as I was of her. I stayed two hours with her, because she wasn’t afraid of me. It’s fantastic, our planet, and we are just a micro part of this huge life.

MH: What did you read? Were you reading Darwin? Were you reading poetry?

SS: I read Darwin, absolutely. I came to start at Galápagos because Darwin finished all his trip up with the Beagle, his boat. It is here that he finalized all the research to create the theory of evolution, and I came here trying to understand what he understood. I had all the writings. I went to exactly the same place Darwin came.

MH: So now what are you going to do? What’s next?

SS: Now I am working on another story. After last year, I started to do a story with the Indian movement in the Amazon. I want to do a story about the Amazon Indians and the Amazon Forest, link the two.

MH: Man and nature, and the nature of man. Is it complicated to get access?

SS: It is. I am working with the National Foundation of Indians, the Ministry of Justice. You must get authorization to be accepted by the Indians. It’s a long preparation. Now we were in Brazil this past winter for them to get three authorizations for the next year. I go to three different tribes next year.

_____

Sebastião Salgado (born in Brazil, 1944) was initially an economist, and began his photographic career in Paris in 1973. He worked with the Sygma, Gamma, and Magnum Photos agencies until 1994, when he and his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado founded Amazonas Images, dedicated exclusively to his work. He has traveled to more than a hundred countries for his photographic projects, which—after being published in the press—are mainly presented in books including Sahel, l’homme en détresse (1986), Workers (Aperture, 1993), Terra (1997), The Children (Aperture, 2000), Migrations (Aperture, 2000), and Genesis (2013). Traveling exhibitions of his work have been presented throughout the world. Salgado has been awarded many prizes, and is a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador and honorary member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.

Melissa Harris is editor-in-chief of Aperture Foundation.

The post Sebastião Salgado: Genesis appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Billy Bragg Visits Aperture

For The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction, we commissioned Alec Soth, Billy Bragg, and Joe Purdy to take a road trip and create a live performance of music, photography, and video. They drove from Rock Island, Illinois, to Little Rock, Arkansas, performing and gathering material along the way. This week, Billy Bragg stopped by Aperture Gallery and spoke to executive director Chris Boot about the trip.

The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction, an evening of art and entertainment in tribute to Robert Frank, will take place October 21 at Terminal 5 in New York City. Purchase your ticket here.

The post Billy Bragg Visits Aperture appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 12, 2014

Remembering Charles Bowden, 1945–2014

Courtesy of Molly Molloy

The December 1996 issue of Harper’s had just come out and within days, I received an unprecedented cluster of phone calls about one article. The anticensorship lawyer Burt Joseph and photographers Lynn Davis and Sally Mann each called to say that I had to read a devastating piece by a journalist named Charles Bowden. Bowden had focused on a group of young, unknown, Weegee-like Mexican photographers, risking their lives in Juárez to confront and combat corruption (including in the government and police forces), narcotraficantes, and the exploitation and murder of women. “It’s your kind of story,” the three of them said—and they were correct. Along with exceptional reporting on an issue most turned away from, it also placed front and center photography’s sometimes singular, searing ability to insist that attention must be paid.

Chuck was prescient, as always. It was years before Juárez as a place and as an issue would be covered regularly, before it would enter into the public eye, and he was remarkably courageous—physically, and in terms of his at-times unpopular convictions. And he was bilingual, understanding both words and images and how they may brush up against each other, sometimes realizing a power together that neither might have otherwise achieved alone.

His article resonated with urgency. I wanted to do a book with him and these photographers immediately, so I called him up. Fortunately, his number was listed in Tucson, Arizona, where the contributor’s bio indicated he lived. His signature sonorous voice at the other end of the line—deep, gravelly, yet kind of laid-back—said something along the lines of: “I was waiting for your kind to call.” He was wary at first. He knew of Aperture, but didn’t see this as a typical Aperture book. I reassured him we could do it fearlessly and with integrity, then sent him what turned out to be our ace in the hole: Eugene Richards’s Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue (Aperture, 1994). This blew his mind. It convinced him that Aperture had the chops to make a book with him on Juárez.

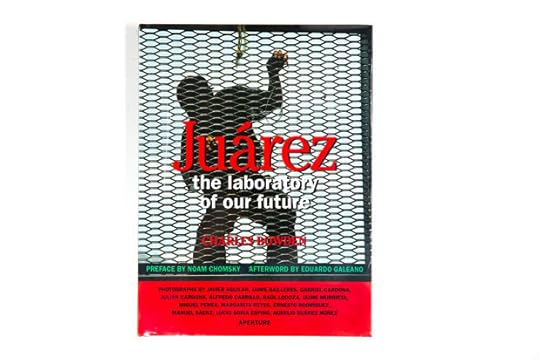

Charles Bowden, Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future (Aperture, 1998), winner of the 1999 ICP Infinity Award for best publication.

Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future (Aperture, 1998) includes photographs by Javier Aguilar, Jaime Bailleres, Gabriel Cardona, Julián Cardona, Alfredo Carrillo, Raúl Lodoza, Jaime Murrieta, Miguel Perea, Margarita Reyes, Ernesto Rodríguez, Manuel Sáenz, Lucio Soria Espino, and Aurelio Suárez Núñez, as well as a preface by Noam Chomsky and an afterword by Eduardo Galeano. It happened because Patrick Lannan and the Lannan Foundation also had a vision and came in as an instant supporter and advocate. It is one of the more brutal and raw subjects I’ve ever worked on. It is also one of the books I’ve edited that matters most. Chuck’s honesty and passion as a mission-driven, willful, open-minded, and brilliant investigative journalist, combined with his free-spirited pleasure in defying givens, was an exhilarating provocation to take a stand, to make a difference. Along with this, his certainty that images and words could coexist with parity—that one did not have to illustrate or be subservient to the other—made him an extraordinary collaborator and ally. Juárez, at the time, was one of the few books Aperture had ever done where the images and the text carried equal weight, and together drove the narrative. It presented a great challenge to me and to its designer, Wendy Byrne. Chuck’s mind was constantly racing in so many directions, drawing on such a breadth of knowledge and experience, conversations always kept me on my toes—which was an incredible tonic. He was viscerally, uncompromisingly awake.

When, in 1999, Michael Hoffman, Yolanda Cuomo, and I were working on the reconceptualization and redesign of Aperture magazine, Chuck was my pen pal and coconspirator, having been a magazine editor himself with strong opinions. A few days after he saw the first issue of the “new” Aperture in 2000, an unsolicited, “rough promotional manifesto” for the reconceived magazine appeared in my inbox.

“The camera may lie, cheat, and steal,” he wrote, “but it never has to stay home. Let’s team the fresh eyes with the best writing and let them play like musicians in an after hours club. Let’s have harmony, dissonance. Let’s improvise. Let’s have no rules or schools or borders. Let’s take the white gloves off. Let’s be happy, let’s be riveted, let’s be sad, let’s be the ocean blue, and let’s be alive to what light and film can do to our souls.”

To say Chuck was prolific is the understatement of the centuries. He wrote tirelessly and relentlessly; there were always projects. But along with his books and magazine articles, he offered, with typical generosity, to lend a hand in getting the word out about Aperture’s new iteration. We were thrilled!

In the twelve years that I was the editor of Aperture, I commissioned eight articles by Chuck. Or really, I had a couple of ideas, and he had multiple. Woven through all of his pieces were sensuous considerations of time, life, death, love, and beauty, and the extraordinary wonder in being.

You can read two of these articles here. One, “The Other Life of Photographs”, I asked him to write for Aperture magazine’s fiftieth anniversary in 2002; the other, “The Lives of the Saints,” he sent to me in 2011 to have my way with.

Courtesy of Molly Molloy

When Yolanda Cuomo first met Chuck, she called him a cowboy: tall, in blue jeans, longish hair, rugged, sun-baked. A friend of his I knew called him “walking testosterone.” He was charismatic in that Sam Shepard sort of way, but not macho. And he was exceptionally kind, supportive, talkative, private, and the person you’d definitely want in your lifeboat. Conversations might engage ideas, ranging from the border to corruption to the death penalty, to humming- and other birds, a beloved tortoise, a cherished dog, Hoyt Axton, red wine, a new recipe, night-blooming cactus, long desert walks, and his dear friend and partner in crime, Edward Abbey.

Chuck was a dreamer, a visionary, a sensualist, a doer, a lover, an intense and luminous individual with an inimitable voice and an unrivaled social conscience. He had no patience for conformity, no interest in power except to effect change. He often wrote of an “is-ness”—a word that I’ve stolen several times. I took that to mean a kind of presentness and in-the-worldness that made everything vital and electric. And that was Chuck.

“Look,” said Chuck, “you have a gift, life is precious, and eventually you die. All you are going to have to show for it is your work, and whether you did a good job or not.”

Chuck Bowden died in his sleep on Saturday, August 30, in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he lived with his partner, Molly Molloy. He was sixty-nine. The loss of his voice, his presence, his originality, his mind, his heart, and his friendship is immeasurable. As a friend of his wrote of Chuck’s last moments, “I hope he heard the birds singing.”

—Melissa Harris, September 9, 2014

The post Remembering Charles Bowden, 1945–2014 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 11, 2014

Recap: Aperture “Fashion” Launch at Gagosian Shop

On Tuesday, September 9, at the height of New York Fashion Week, the Gagosian Shop hosted the launch of Aperture magazine’s Fall 2014 issue, #216, “Fashion”. Guest-editors Inez & Vinoodh joined Aperture staff and guests to discuss the issue, which is dedicated to fashion photography.

“Fashion” is available in print, and online. Click here to subscribe to Aperture magazine.

All images © Max Campbell.

The post Recap: Aperture “Fashion” Launch at Gagosian Shop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 9, 2014

Postcards From the Road: Silent Auction Preview

Christina DeMiddel, Untitled from the series Antipodes, 2013

Richard Misrach, Birds, Boca Chica Highway, Gulf Coast Texas, 2014

Tierney Gearon

Amy Stein, Steven, Route 10, Louisiana, 2006

Martin Parr, from the series From A to B, 1994

Olivia Bee, The Middle of Nowhere, CA, 2013

Phil Toledano, Hydrant, 2005

Mark Peterson, Rose at the Golden Gate

Oliver Chanarin, Runway built for the set of Catch-22, filmed in San Carlos, Mexico, 1969

Andrew Moore, Negaunee, Michigan

Charlotte Dumas

This fall, we’re excited to host The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction, an evening of art and entertainment in tribute to Robert Frank, in conjunction with Aperture’s fall book release The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip.

In addition to live performances by the Kills and Alec Soth, Billy Bragg, and Joe Purdy, as well as a DJ set by AndrewAndrew, the evening will include a live auction of commissioned works inspired by the road and a silent auction of small framed works from one hundred photographers—“postcards” from the road. Some of these photographs are iconic, such as Martin Parr’s image from his series From A to B (1994), while others were inspired by the Benefit theme.

Visit the Open Road site for the latest news and to purchase Benefit tickets.

The post Postcards From the Road: Silent Auction Preview appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 4, 2014

The Last Book by Reinier Gerritsen (video)

The world—and the word—is in the process of becoming less and less dependent on paper. Our reading habits, especially as they occur in public spaces, are subtly shifting each day. In The Last Book, published by Aperture this fall, photographer Reinier Gerritsen has taken up the current plethora of books and their readers on New York City’s subways as the proverbial canary-in-the-coal-mine: an indicator of the still-robust nature of public readership in the face of its ostensible decline.

Gerritsen’s photographs of people reading books on the subway began with modest observations and evolved into The Last Book, a series of unexpected documentary portraits. His book also includes an illustrated index and bibliography charting readership. We joined Gerritsen on the subway in New York City, where he took us through his process of shooting and editing. Of the chaotic, crowded cars, Gerritsen remarks, “The light is magnificent . . . it’s such a dense situation of people. A lot of sociological events are very visible in the subway.”

The Last Book and a limited-edition print by Reinier Gerritsen, Haruki Murakami, 1Q84, 2005 , are available online.

The Last Book

The Last Book$65.00

Add to Cart

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84, 2005

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84, 2005$700.00

Add to Cart

The post The Last Book by Reinier Gerritsen (video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 2, 2014

Aperture #216 – Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #216 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Inez & Vinoodh, Waiting for Kate, 2001 © Inez & Vinoodh and courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York, and The Collective Shift

Though this issue’s title appears in quotation marks, the intention is not to be ironic, or to suggest skepticism. Rather, the quotes allude to image quotation and reference, which are part and parcel of any creative act but are essential to the world of fashion. “In today’s professional climate . . . you’re only as good as your references,” guest editors Inez & Vinoodh note in their introduction to a portfolio of images by fashion’s most iconic and imitated photographers. Referencing is delicate, requiring thoughtful handling to avoid crossing the line into copying. Curator Charlotte Cotton remarks in her contribution that fashion photography’s often transparent use of references may be one reason why the genre is criticized from other corners. But in the end what matters is how a reference is used: when adequately transformed, you may sense a quotation but won’t recognize its source.

Transformation, in a broader sense, is a hallmark of Inez & Vinoodh’s work. The husband-and-wife team has collaborated for more than twenty-five years, breaking ground in the 1990s with their early digital interventions into fashion photography. Their work is marked by restlessness and curiosity about photography, a tension between illusion and reality, the beautiful and the grotesque, and a desire to explore the medium’s generous flexibility. The protean nature of their output has earned them both commercial success and art-world kudos. In these pages, writer Donatien Grau describes their agnostic practice as a “collaboration embedded within collaborations,” noting their frequent partnerships with artists, graphic designers, even pop stars.

The “Pictures” section comprises key influences and references for Inez & Vinoodh. Some choices may be surprising, as not all emerge from the field of fashion but instead reference styles from various periods, as in the work, spanning the 1950s through the 1980s, of Ed van der Elsken, the influential Dutch documentary photographer. A selection of the wonderfully beguiling ads produced in decades past for the Shiseido cosmetics company are a reminder that commercial art often warrants serious consideration. A collage from Pop artist Richard Hamilton’s Fashion-plate series appears on our cover, an image that playfully underscores the artifice, construction, and illusion that is fashion image making. This 1969 collage is part of a portfolio that considers photographs that have served as references for painting. Hamilton sourced his material from fashion magazines, the medium through which the story of fashion photography is often told. A new generation of photographers has gleaned much by flipping through back issues of the pioneering magazines i-D, The Face, and Jill, all of which fostered the careers of many major photographers and stylists. (The dog-eared and even cut-up copies of these publications in the Fashion Institute of Technology’s library attest to their consistent use as reference material.) Closing the “Pictures” section are two emerging photographers who reference photography’s recent past: the street tradition for Daniel Arnold and a casual diaristic touch in the work of Margaret Durow.

In “Words” we consider the growing area of fashion film, the complex relationship between documentary photography and fashion, and a conversation between two of fashion’s most influential magazine editors, Penny Martin of The Gentlewoman and Emmanuelle Alt of Vogue Paris, details the production of fashion photography and the sensitivities of using archival references when working with photographers. Alt notes that “your first music and visual influences stay with you forever. . . . You live with what was around when you first became curious.” Indeed, much of what forms this issue is culled from what was around when Inez & Vinoodh first became curious, as they note, echoing Alt’s observation, that fashion is nostalgic and based on a “string of memories.”

—The Editors

The post Aperture #216 – Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Final Call for Entries! The PhotoBook Awards 2014

The call for entries for the 2014 edition of The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards is coming to a close, and we have received an incredible selection of books thus far. This year we were excited to reveal the introduction of a third award category, Photography Catalogue of the Year, which joins the PhotoBook of the Year and First PhotoBook categories. There’s still time to enter in all three categories.

Entries must be received at Aperture Foundation’s offices in New York by September 12, 2014, in order to be considered.

Click here for entry details and FAQ.

Join us Friday, September 26 at the NY Art Book Fair, where Todd Hido will announce the PhotoBook Awards Shortlist.

The post Final Call for Entries!

The PhotoBook Awards 2014 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 29, 2014

Workshop Instructor Profile: Rob Hornstra (Video)

Over the weekend of May 31 and June 1, 2014, Rob Hornstra taught a weekend workshop at Aperture Foundation. The workshop, DIY Storytelling, focused on self-publishing a photobook. Hornstra took participants through the processes of financing, shooting, designing, promoting, and selling each of his self-published projects, and ended the workshop with a discussion about the landscape of contemporary photobook publishing. We caught up with Hornstra on the final day of the workshop to discuss his role not only as a storyteller, but also as an instructor.

Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen are the creators of The Sochi Project, a “slow journalism” series focusing on the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics, and the authors of the 2013 Aperture book The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus.

Rob Hornstra’s workshop was part of Aperture’s workshops program, which brings students, professionals, and amateurs together with leading photographers working in a variety of fields and genres. Workshops focus on topics related to photobook design and history, current photographic practice, and the history of the medium. View a complete list of Aperture’s Fall–Winter 2014 Workshops.

The post Workshop Instructor Profile: Rob Hornstra (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers