Aperture's Blog, page 179

June 10, 2014

The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus

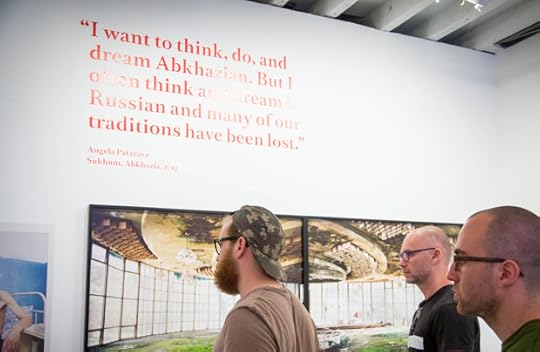

On Wednesday, June 4, Aperture Members and friends were the first to view Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen’s exhibition The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus at Aperture Gallery. Hornstra and van Bruggen gave Members an exclusive tour.

The exhibition is on view through July 10, 2014. The accompanying publication, The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus, was published by Aperture in 2013.

Membership at Aperture is about seeing it first. Engage with our talented photographers, writers, and editors at a variety of events like this by becoming an Aperture Member today! For more information, e-mail membership@aperture.org.

All images © Katie Booth.

The post The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 5, 2014

Inside the DIY Storytelling Workshop with Rob Hornstra

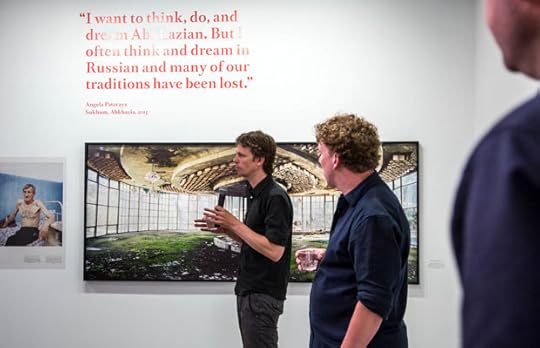

Over the weekend of May 31 and June 1 at Aperture Foundation, photographer Rob Hornstra led a very informative workshop on self-publishing a photobook. Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen are the creators of The Sochi Project, a “slow journalism” series focusing on the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics, and the authors of the 2013 Aperture book The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus.

At the workshop, participants learned about Hornstra’s process of financing, shooting, designing, promoting, and selling each of his self-published projects, allowing them to gain insight into the advantages and disadvantages of working as an independent book publisher. Students were also encouraged to share their own projects and were given advice on transforming their work into photobooks. The workshop ended with a discussion on the landscape of contemporary photobook publishing, which included some examples of successful and unique photobooks, and a look at the most prestigious photobook awards.

—

To learn more about Aperture workshops, click here.

Images © Katie Booth.

The post Inside the DIY Storytelling Workshop with Rob Hornstra appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 4, 2014

Inside Our Spring Patron Cocktail Event

On the evening of Wednesday, May 28, over fifty Aperture donors, board members, and artists gathered at the home of Trustee Jessica Nagle for Aperture’s inaugural Spring Patron Cocktail Party. Artists in attendance included Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao, Mary Ellen Mark, Matthew Pillsbury, Richard Renaldi, Stefan Ruiz, Mickalene Thomas, and Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb. This celebration is just one of the many exciting opportunities available to Aperture Patrons. We thank our Trustees, Members, and artists for their involvement in and support of Aperture.

—

To learn more about Aperture’s Patron Program, click here or contact Emily Grillo at egrillo[at]aperture.org.

Images © Katie Booth.

The post Inside Our Spring Patron Cocktail Event appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Caio Reisewitz by Christopher Phillips

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

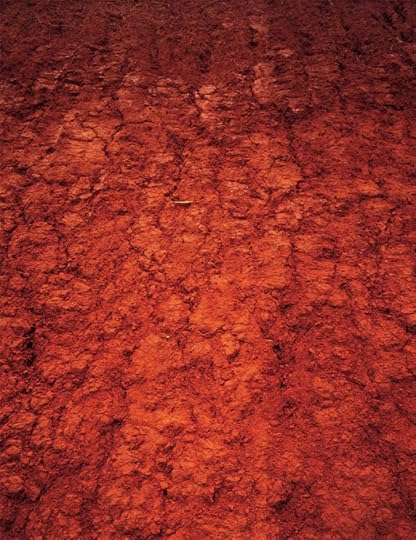

Caio Reisewitz, Cubatão II, 2003. © Caio Reisewitz and courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

Caio Reisewitz, Boituva, 2008. © Caio Reisewitz and courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

Since returning to São Paulo in 1997 after studies in Germany, Caio Reisewitz has won an international reputation as one of Brazil’s most significant photographers. His admiration for members of the Düsseldorf School such as Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, and Andreas Gursky is evident in the meticulous accuracy of his monumental color photographs, yet his concentration on the landscape and architecture of Brazil lends his work a distinctive and immediately recognizable character. Reisewitz’s images offer a sustained reflection on the struggle between primeval nature and the voracious human appetite to exploit it that has marked Brazil’s history since colonial times. The title he chose for his presentation in the Brazilian pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale, “Threatened Utopia,” signals the key preoccupation of his work.

The dense rainforest settings of many of Reisewitz’s photographs have led some viewers to assume that he specializes in scenes from the Amazon region. In fact, most of his landscape photographs are made within a few hundred miles of São Paulo, a silver-white skyscraper city surrounded by an immense, verdant tropical forest. Reisewitz regards the still-extensive remnants of the Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Forest) that once filled Brazil’s east coast as a natural wonderland, and he marvels that it is virtually unknown to São Paulo’s twenty million urban dwellers. The relation of city and country-side in Brazil today could be described as one of close physical proximity and surprising psychological distance.

Often Reisewitz’s photographs recall the extraordinary abundance of Brazil’s natural environment and the history of its domestication for cropland, ranching, and mining. Boituva (2008) presents a close-up view of a patch of the famous red clay soil that eighteenth-century colonists discovered to be ideally suited for coffee cultivation. In Cubatão II (2003), we look down on a ribbonlike highway slicing through an otherwise pristine vista of mountain forests. Itaquaquecetuba (2004) shows a green hilltop set ablaze as part of a land-clearing operation. Such images register the current state of Brazil’s breakneck quest for economic development and pinpoint the global environmental dangers posed by the wholesale destruction of Brazil’s forests.

Caio Reisewitz, Itaquaquecetuba, 2004. © Caio Reisewitz and courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

Caio Reisewitz, Diadema, 2004. © Caio Reisewitz and courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

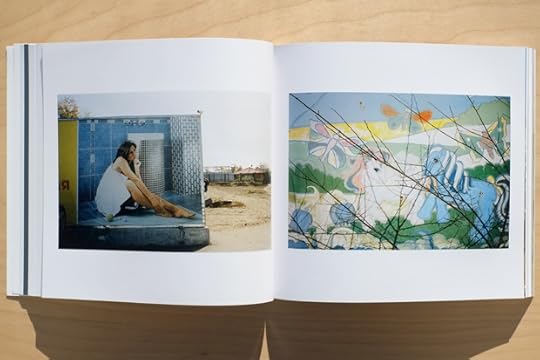

Reisewitz’s work has recently moved in surprising new directions, notably in a series of small, handmade photo collages that extend his exploration of the tension between the city and the countryside. Visually more playful than his view-camera photographs, these works sometimes contain lyrically curving cutouts that echo the exuberant visual rhythms found in Brazilian modernist art and architecture of the 1960s. These collage experiments have led Reisewitz to new ways of conceiving his view-camera photographs. His latest large-format works often employ a dense visual layering, as in Santuário San Pedro Claver III, Cartagena de Índias (San Pedro Claver III monastery, Cartagena) (2007), in which elusive architectural details can be glimpsed through a tangled skein of tree branches and plant forms.

The city in the forest, and the forest in the city—this is the metaphor that currently drives much of Reisewitz’s work. It underlies his photographs of Brazil’s iconic modernist residences, such as that of the 1928 Casa Modernista by émigré Russian architect Gregori Warchavchik, Casa Rua Santa Cruz (House on Santa Cruz Street) (2013), and of the 1951 Glass House by Lina Bo Bardi, both located in São Paulo. It is probably most evident, however, in his photograph Casa Canoas (Canoas House) (2013), which provides a fresh look at the legendary minimalist-style house that Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer built for himself in 1951 on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. As Reisewitz portrays it, the glass-walled house all but disappears amid the luxuriant vegetation that presses in on all sides. At the same time, the building’s elongated and sensuously curving white roof seems to reach out to embrace the forest. In images like this, Reisewitz holds onto the hope that nature and human culture may yet share common ground in Brazil.

Caio Reisewitz, Casa Canoas (Canoas House), 2013. © Caio Reisewitz and courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria, São Paulo

—

Christopher Phillips, a curator at the International Center of Photography in New York, organized the exhibition Caio Reisewitz, on view at ICP from May 16 to September 7, 2014.

The post Caio Reisewitz

by Christopher Phillips appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 3, 2014

Tomatsu on the Americans (Video)

Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012), one of Japan’s foremost twentieth-century photographers, created one of the defining portraits of postwar Japan. Beginning in the late 1950s, Tomatsu committed to photographing as many of the American military bases in Japan as possible, focusing on the seismic impact of the American victory and occupation: uniformed American soldiers carousing in red-light districts with Japanese women; foreign children at play in seedy landscapes, home to American forces; and the emerging protest formed in response to the ongoing American military presence. Images from one of his iconic series from this time were recently published by Aperture as the book Chewing Gum and Chocolate.

On May 20, we joined photographer and curator Leo Rubinfien (editor and essayist of Chewing Gum and Chocolate), Dr. Miwako Tezuka, and Matthew Witkovsky for a panel discussion on Tomatsu’s work and influence on a generation of Japanese photographers.

View “Tomatsu on the Americans” Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 on Vimeo.

The post Tomatsu on the Americans (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 30, 2014

Black in the Rose Garden: Sarah Jones at Anton Kern Gallery

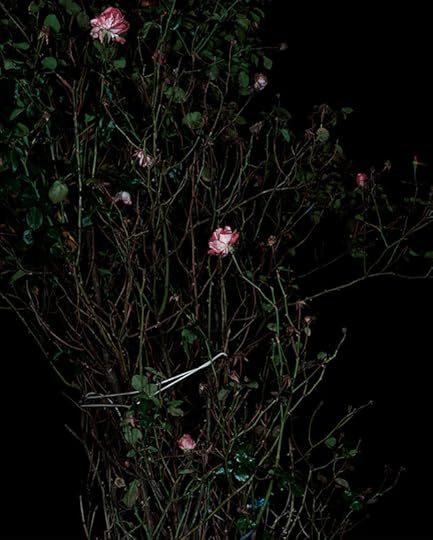

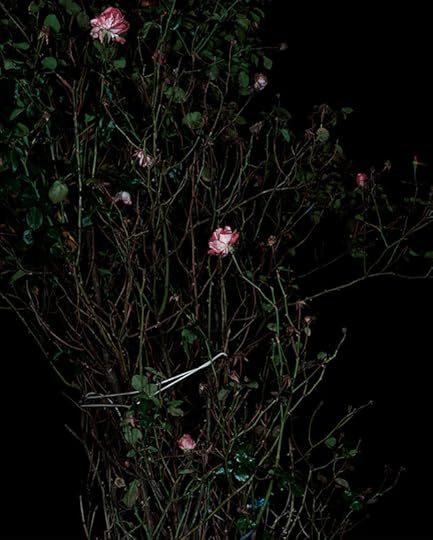

Sarah Jones, The Rose Garden (Display) (VII), 2014.

Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones, Horse (profile) (black) (II/II), 2014. Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones, Vitrine (I/I), 2003.

Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones, Cabinet (III) (Drape), 2003.

Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones, Cabinet (IV) (Red Velvet), 2013.

Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones, Rosehip (I), 2014.

Courtesy Anton Kern Gallery, New York

Sarah Jones draws out her photographs as opposed to simply taking them. The artist creates environments for contemplation and, with the slow pace of a meticulously traced still life, forms staid yet poetic images with her camera. A whist rose, some cloth laid out, a long-haired woman; Jones’s images are never ugly, but always unsettled.

The London-based artist, born in 1959 and educated in painting and fine art at Goldsmiths, has been photographing various subjects of intellectual and aesthetic curiosity since the 1990s. Whether it be an analyst’s couch, a close-to-empty artist’s studio, a horse, a young woman, or a decaying flower frozen in some Cimmerian shade, Jones chooses austere subjects—academic propositions tied to the weight of art history. These images are beautifully sequenced in the artist’s first monograph, Sarah Jones, published in October 2013 by Violette Editions. Accompanied by two essays and an interview, the book provides a substantial and rich description—in all its diversity of subject matter and allusion—of Jones’s practice to date. A recent exhibition at Anton Kern Gallery in New York, which closed April 26, picked up on this survey by presenting works from the book alongside more recent images. Twenty-one pictures were positioned evenly along the gallery walls. No room for mess here; everything was framed, contemplated, and presented in blackness.

In her photographs, the artist draws out the deep black tones made possible by expert analog printing from black-and-white negatives, surrounding the images’ focal points in a fabricated night (some of the images are shot in daylight with a flash, “radically underexposed,” as Brian Dillon writes in his essay in the book). Van Gogh thought there was a better way to give color depth than to use black; in an 1888 letter to his younger art dealer brother Theo, the painter offered some examples and a word of warning: “Indigo with terra sienna, Prussian blue with burnt sienna, really give much deeper tones than pure black itself . . . I retain from nature a certain sequence and a certain correctness in placing the tones; I study nature, so as not to do foolish things, to remain reasonable.” In photography, however, this is made irrelevant by the way photographic printing selectively occludes rather than favors natural objects, plucking out any object from a black, chemical space whatever its distinction. Jones uses lighting techniques to fabricate a black backdrop for the naturalness of flowers or a horse to appear in front of, therefore placing them in a strange sort of isolation: the natural and the chemical sit together in a blank, distinctly photographic frieze.

Jones’s theoretical references have included Sigmund Freud, Jaques Lacan, and other pedestalled intellectuals seemingly bound to photography and its theories in the UK and further afield since their introduction in the 1970s by Victor Burgin, among others. The artist demonstrates this in part through a body of work featured in the book—but not the exhibition—titled Consulting Room, in which the empty and therefore perhaps untroubled spaces of analysts’ couches recall psychoanalytic theory and its relationship to the photographic image. Some of the couch covers appear creased, evoking recent use, while others seem neat and as yet unperturbed. In A. M. Homes’s interview with the artist in the book, Sarah Jones explains how she began photographing these couches during her master’s studies as “a response to the theory being taught.” The influence of photography theory from 1970s and ’80s on contemporary work in the UK has now become nearly overbearing, but Jones handles these tricky and somewhat hackneyed reference points with little naiveté, an admirable sensitivity, and, importantly, a light touch.

Two later bodies of work included in the monograph and Anton Kern exhibition, Rose Gardens and Cabinet, expand and trade instead on the meaning of historically prevalent objects from the nineteenth century. Victorian designer Augustus Pugin’s gothic revivalist tendencies are apparent in a photograph of an elaborate iron screen (Screen I, 2014), while in another image, the reflective qualities of a gazing ball—an object often associated with the English Victorian garden—allude to the diverse interior design of the period. The compositional influence and style of photographer Karl Blossfeldt’s botanical studies is certainly present in Jones’s photographs of roses, as is Muybridge’s black horse, here presented motionless and in almost complete obscurity against its black background in the photograph Horse (profile) (black) (I), from 2010.

The artist also has an interest in the very Victorian cultural obsession with photographing hair—one which, today, is also perpetuated by collectors Brad Feuerhelm in London and W. M. Hunt in New York, who amass such fetishistic photographs, not to mention younger artists such as Tereza Zelenkova, a former student in the photography department at the Royal College of Art, where Jones tutors. To her credit, Jones avoids overstating this particular gothic cliché, only lightly referring to the existence of such visual preoccupations in her own works The Park (II), The Living Room (I), and The Guest Room (II), all 2002–3.

Installation view of Jones’s recent exhibition at Anton Kern Gallery, New York (March 27 – April 26, 2014)

Jones included several diptychs in the Anton Kern exhibition, which could be read as direct reflections of a single picture. Like Rorschach inkblots, the artist’s compositions, such as Vitrine 1/1 (2014), fold in on themselves, as one might expect from a hinged canvas trapping the view of a subject and conjoining one picture to another. The only hidden doors in Jones’s Cabinet images, which depict empty black vitrines, are metaphorical; these photographs appear to have little actual depth. As Van Gogh observed, “Black is not as deep as it looks: mixing the dark tones of nature together produces a depth like no other”—perhaps including that produced by the canonized theorists of photographic representation. One can either fall into black interiors in this exhibition or have them collapse around you.

Darkness certainly demands something, and it is in this space that Jones asks us to consider her work. What first appears black in her photographs is actually silver, gray, or even purple. While the language of academic art-making might often be narrow and elusive, the artist either reflects back her references to art history and photographic theory or folds them in on themselves, saving her own work from didacticism. Her pictures are generous not just in terms of intellectual context and reference, but also in sheer attractiveness.

—

Daniel C. Blight is a writer and critic based in London who contributes to the Guardian, frieze, and Notes on Metamodernism. He is the editor of The Photographers’ Gallery blog and the curator of Chandelier, a project space for contemporary art in Hackney, London.

The post Black in the Rose Garden:

Sarah Jones at Anton Kern Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The More Things Change: An Interview with Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2013. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

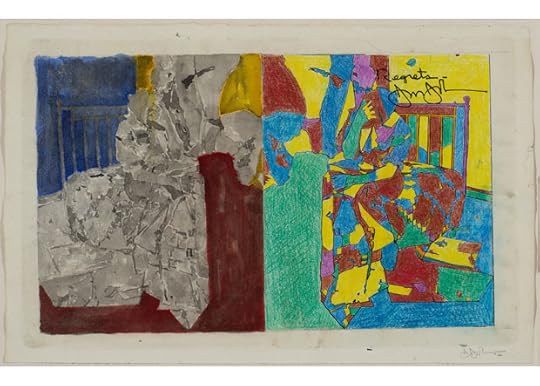

Jasper Johns, Study for Regrets, 2012. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

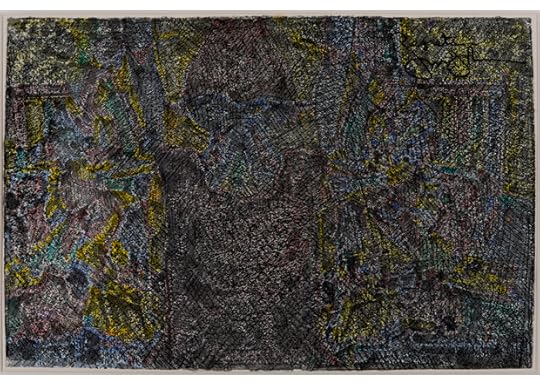

Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2013. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

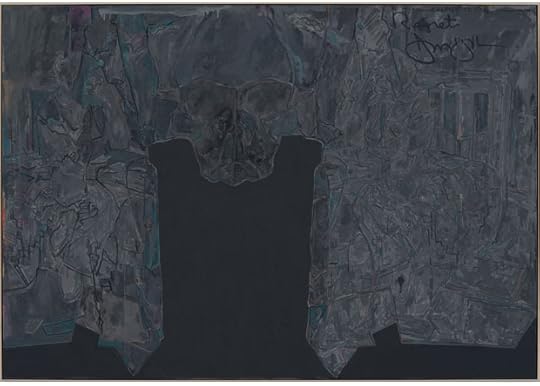

Jasper Johns, Regrets, 2013. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

Jasper Johns, Regrets, 2014. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

Jasper Johns, Regrets. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York

We tend to think that a photograph of someone reveals something about that person, but sometimes, what we take away from an image is ultimately dependent upon the circumstances; the portrait’s truth to the subject perhaps relative, its evidentiary value negligible, its elemental nature morphing and evolving through the process of being reworked, reconsidered—depersonalized (or not)—as it gets recontextualized.

Around 1964, Francis Bacon commissioned the British photographer John Deakin to photograph Lucian Freud; the image was used as a reference for Bacon’s eventual triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969). It is said that Bacon messed with his source material when he worked—tearing it, folding it, and splattering it with paint. Does this photograph, as presented here, tell us about Freud, or Deakin, or Bacon?

In the spring of 2012, Jasper Johns saw Deakin’s portrait of Freud in an auction catalog, reproduced on a black background. Johns lifted the image and had his way with it, in terms of both form and content—creating variation after variation. The original photograph and the resulting works—two paintings and a group of drawings and prints made between 2012 and 2014—are currently on view in Jasper Johns: Regrets, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (through September 1). The exhibition’s title is a riff on the words on a rubber stamp the artist has employed as a mode of declining requests and invitations when need be.

It would seem that it was not the fact of Lucian Freud that initially drew Johns to the photograph. The image, composition, and physicality of the already much-handled print clearly engaged Johns. For some viewers, however, the provenance of the photograph inevitably informs Regrets, and Johns is forthcoming about its source. But then—teasing the photograph’s intrinsic documentary quality and intentionality, and treating it almost as a found object—Johns offers us a way into the work beyond its layered narrative: here is a picture of an artist, commissioned by a second artist, made by a photographer, and then taken up and deconstructed anew by yet another artist.

There have been moments in Johns’s work at which he has clearly referenced a specific person, in a way that is deeply essential and experiential—more of than about the individual. Consider, for example, Frank O’Hara’s footprint in the sand in Memory Piece (Frank O’Hara) (1961/1970); or the painting commissioned for what is now called the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center, Numbers (1964)—the corner of which bears the imprint of Merce Cunningham’s foot. Consider Johns’s signature target, rendered in flowers, offered in lieu of his own physical presence onstage at David Tudor’s 1961 performance of John Cage’s Variation ll in Paris. Numbers, targets, footprints, flowers: stand-ins for the person? Measuring devices for quantity, distance, time? Evocations of absence—regretted or not—and presence? Then there are Johns’s Study for Skin works from 1962, and Skin I and Skin II from 1973—the impressions of his oiled body on paper—perhaps another kind of stamp? Johns made use of his own body again, outlining his shadow, in his series of paintings, prints, and drawings titled The Seasons of the late 1980s, touching on notions of time passing and the mutability of identity.

Positive and negative space, depth of field, light and shadow, time—traditional photographic concerns all come into play in Johns’s work. Consistently and insistently, Jasper Johns: Regrets is about seeing, about looking. In his case, the more things change, the more things change.

We are most grateful to Jasper Johns for not rubberstamping our request for an interview, and for taking the time to respond to some questions in April.

—Melissa Harris

Melissa Harris: In the case of Regrets, does personality matter? Could the photograph have been a portrait of anyone, or was it important that it was of an artist—and particularly of Lucian Freud?

Jasper Johns: I don’t think I was aware that Freud was the person shown in the photograph when I first saw it. I was attracted to the image as a whole, without analyzing it.

MH: What, if anything, about photography interests you?

JJ: Photography is often interesting, but I know almost nothing about it. We may be grateful that photographs offer serious clues to spaces other than those we occupy, and, often, to eyes and minds other than our own.

MH: Does the repetition—the process of reworking the initial idea or image and doing so in different media—denude it of any personal or other meaning? Or does it intensify that meaning?

JJ: I don’t think that the photograph alters the painting or that the painting alters the photograph. I am not sure that there was an “initial” “idea.” The response to the photograph was not a preconception of the paintings, etc., but the activation of an energy that moved toward or through the various works. One might imagine a kind of chain reaction in which each element is affected by the nature of the others.

MH: How much was Regrets preconceived, from the moment you saw the photograph and knew you wanted to use it in some way? Or is it the process that dictates the result?

JJ: Here is a group of works with one title and they seem closely related. But any group of works from a limited period of time is usually closely related by some preoccupation or focus that the artist has been concerned with. Viewers are not always given access to such groups and may not be interested in that aspect of the works.

MH: The archaic use of the word regret is related to “absence.” The more visually dominant space in Regrets is shaped by the missing space in the object of the print—how it was worked, folded, and so on. Were you thinking about that at all? Is it about being there, or not? Positive and negative space—the vase/profile notion, as in your Cup 2 Picasso (1972–73)?

JJ: I would say that, much of the time, I was thinking about what I saw, and much of the time about what I was thinking.

MH: In Souvenir 2 (1964), you used a photograph of yourself. Why?

JJ: I had not seen photographs applied to ceramics before seeing them in a shop window in Tokyo. Wanting to use such a thing in my work, it only occurred to me to use my own image.

MH: Regrets brought to mind your painting Between the Clock and the Bed (1981)—not just the mirroring (with the crosshatches in the earlier work), but also the reference to Edvard Munch, the bed, and a kind of despair. Is there any relationship?

JJ: As you have made the relationship, so have I.

MH: The repetition in the group of works insists that the viewer examine closely. Attention must be paid if we are to notice the nuances, the variations on a theme. . . . I almost felt I saw a ghost of a young man on the left side of the watercolor on paper. I thought I saw one of your skull-like motifs in some of the other works, where the mirroring unfolds. It can be like reading pictures in clouds. We can see, find, interpret anything at some point. Are you interested in the multiplicity of possible readings?

JJ: Yes, it does interest me. Maybe not so much the readings themselves, but the movement among them.

—

Melissa Harris is editor-in-chief of Aperture Foundation.

The post The More Things Change:

An Interview with Jasper Johns appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 22, 2014

The Case for Digital by Simon Bainbridge

Kadir van Lohuizen, Vía PanAm (Paradox/NOOR, 2011)

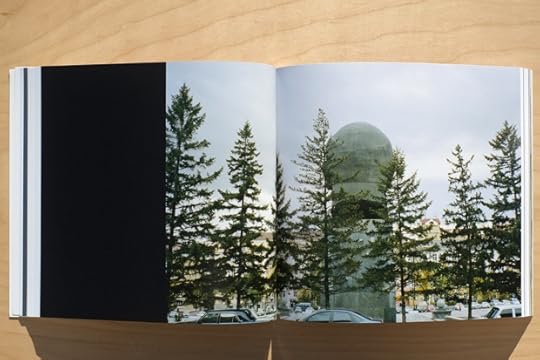

Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux, Atlas photographique de la Lune (MAPP Editions, 2013)

It’s been twenty-five years since Tim Berners-Lee proposed the framework for what was to become the World Wide Web, around the same time Thomas and John Knoll were finessing version 1.0 of Photoshop. Now we live in the digital present, connecting online as global communities; communicating via vast, interlinked networks that bypass geographic, economic, and sociopolitical boundaries; using photographs where common languages don’t exist.

And yet this was first published in a printed newspaper dedicated to photobooks in all their physical manifestations.

In the weeks and months it’s taken to put this issue together—from initial conversations between publisher and guest editor last September, to the final copy deadline in the middle of March, followed by the excruciatingly protracted process of reading, editing, subbing, designing, fitting, checking, sending, scheduling, printing, and distributing—countless brilliant and insightful thoughts about photography will have been discussed elsewhere. Many of these ideas were then typed out and, with very little additional effort, published online. Seconds later, they were being shared and commented on, instantly becoming part of a global discussion unencumbered by the need to deliver an object or commodity, far removed from the cliques and cloisters of photobook fandom. In a sense, the resurgent photobook is the perfect riposte to all this. Let’s face it: much of what we read online isn’t that enlightening, in part because of how easy it is to get thoughts out into the world. By contrast, the photobook is a fine example of slow publishing. It brings together artists and editors with highly skilled designers and makers to produce a tightly curated artwork in extended form, one which requires sustained time and thought from the reader, away from distraction.

But I’m concerned that our rediscovery of the printed book also plays to the conservative tendencies running deep within the photographic community.

Surely it’s no coincidence that while most of the world was ditching analog and using digital cameras to rediscover the pleasures of making pictures, art photographers were taking up large-format and hitting the road in their RVs once again. Photographers tend not to be great joiners; they’re usually outsiders looking in. So this early rejection of digital, with its ability to hasten and perfect the picture-making process, probably came from a more radical tendency, an independent streak that was alarmed by the sudden ubiquity of digital SLRs.

This impulse to opt out leaves photography with nowhere to go but backward. Likewise with the book; rather than exploring how digital could expand the form, and taking advantage of these new tools to tell stories and extend artistic practice, we are in retreat. And instead of embracing the opportunity to reach new audiences, we have retrenched, operating in a closed loop that may seem dynamic now, but risks losing relevance to anyone less wedded to the physical book than we are.

I am curious about all this because the arrival of the iPad four years ago gave us the ideal vehicle with which to develop a new language. Tablets bring together the best of the digital realm—its dynamic, instantaneous, interlinking, multimedia forms—with all the accumulated skills and knowledge brought to bear on print over the past five hundred-odd years.

This was certainly our experience with the launch of an iPad version of British Journal of Photography, with which we doubled our subscription base in two years; we are now building a global readership. For the first time ever, we could take our skills to the digital screen to produce something much more cohesive and elegant than we ever could online, bringing the printed page to life with the addition of video (just as photographers were given easier access to filmmaking when broadcast-quality motion capture was added to DSLRs) and intuitive navigational devices that, because they are tactile, are somehow more personal.

So why haven’t we seen the same dynamic in photobook publishing, where the lead times give greater room for experimentation, and the imperative to find wider readerships is even more urgent? There may be worthy intentions behind them, but most of the digital photobooks we’ve seen so far have been terribly dull, failing to advance beyond the printed page in any significant form.

Some of the reasons are economic. Digital publishing isn’t, as many believe, a cheap option. You need to invest time and money setting up, and you more than double the workload by adding a digital format alongside an existing print workflow. There’s something of the dark arts to getting publications through the Apple approval process; visibility for your books on the iTunes storefront is a major challenge. And anything ambitious will require a programmer, which is beyond the reach of most small independents.

An early example of someone using the iPad to unfold a story in a way that would have been impossible in print is Vía PanAm, photographer Kadir van Lohuizen’s investigation of the roots of migration in the Americas, first released as an app in 2011. It brings together the stories of the people he encountered on his nearly 16,000-mile trip from Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of South America, to Alaska. Vía PanAm remains one of the more innovative photography projects to date, using digital publishing and multimedia to explore new narrative possibilities. Van Lohuizen updated the app as he went along, adding text, audio, and pictures during the twelve-month journey in something close to real time. It cost tens of thousands of euros to produce and, despite substantial backing, wasn’t much of a commercial success. Nothing as ambitious has been attempted since.

Even more damaging than the cost is the general sense of apathy toward digital publishing—and the resurgence of the printed photobook is to blame. In our ever-more-cozy relationship with the art market, the photography world has become obsessed with the idea of the limited-edition object. The market demands artwork that is collectible, which means it must be both scarce and tangible. This is killing innovation in the digital realm. Photographers have no reason to invest in it and are seemingly too scared or too lazy to think beyond the ecosystem supported by galleries, who in turn are dependent on collectors who are innately conservative about how they attribute value.

Collectible books—special editions, multiple volumes—are now more financially sustainable than conventional print runs, even if they are priced high and reach far fewer people. Someone who’d been a major part of this model, but decided to address it, is London-based publisher Michael Mack, who says he doesn’t like the idea of merely collecting books instead of buying them on the strength of their merits. He has invested heavily into digital publishing, setting up the e-book publisher MAPP three years ago alongside the traditional book imprint that carries his name.

MAPP produced one of the more interesting digital photobooks yet seen, Jason Evans’s NYLPT, which features multi-exposed frames of overlapping images taken in New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo, as well as audio. In the printed version of the book, there is a sort of narrative structure to it, which Evans plays with in an attempt to interrupt the emerging logic. But it’s only in the digital version that his search for “chance, happy accident, luck” is given full rein, as each time the images and accompanying sound appear in a different sequence. The edit—the Holy Grail of the photobook—is never the same. What plays out is given higher priority than the artist’s ego.

NYLPT is a rare example of the digital version outshining the print, but it’s hardly the brave new world of publishing. For the most part, MAPP has excelled in bringing rare or unseen books into the public realm, such as Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux’s Atlas photographique de la Lune (a pioneering astronomical study of the moon, now rendered as photographs overlaid with semitransparent maps of the peaks and troughs of its surface), or the forthcoming version of William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, which is near-impossible to see in its original form. It is scholarly ambition and a sense of egalitarianism that seem to drive Mack, rather than any desire to take the book toward new frontiers.

This is a small beginning. In the future, digital publishing will intersect with other new technologies, incorporating digital overlays, such as maps and navigational tools, with wearable devices offering the promise of “sensory fiction,” exploring the architecture of gaming environments, and segueing into augmented realities. And yet all that seems so far away. For now, digital photobooks are more of a theory than a reality, the promise of something to come. They have so far failed to seduce. The physical photobook brings together the collective know-how of artists, designers, editors, publishers, and printers, and when they work in harmony, they deliver so much more than the sum of their parts. What has the digital book got to offer instead?

The spell will only be broken if artists themselves begin to take the form seriously, working in tandem with publishers and developers to forge artworks that can stand alone. We need artists with the imagination and ambition of someone like Björk, whose Biophilia project reimagined the album as an interactive game. And we need a community to support them, with residencies and bursaries that encourage partnerships between artists and technologists, institutions that don’t look to the market for what’s coming next, and collectors that invest in artists rather than commodities.

That’s a big ask. But if digital technology is widening the frontiers of society, transforming the ways we live and communicate, it should be seen as a failure if photography is unable to reach beyond its historical confines simply because the established genres we operate in are so familiar. Photography as we know it, so often heralded as one of the youngest of art forms, is in danger of becoming antiquarian.

—

Simon Bainbridge became editor-in-chief of British Journal of Photography in 2003, steering the 160-year-old publication away from its uncertain future as a weekly trade magazine into a monthly that now goes out in print and digital formats. Based in London, he contributes to numerous awards as a judge and nominator (including the Prix Pictet and Deutsche Börse Photography Prize), and has cocurated two exhibitions: Paper, Rock, Scissors: The Constructed Image in New British Photography at Flash Forward Festival, Toronto, and Photography Beyond the Decisive Moment at Hereford Photography Festival, United Kingdom.

The post The Case for Digital

by Simon Bainbridge appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 21, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Justine Kurland on Nicholas Muellner, The Amnesia Pavilions

This is part of the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in The PhotoBook Review 006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

Nicholas Muellner

The Amnesia Pavilions

A-Jump Books

Ithaca, New York, 2011

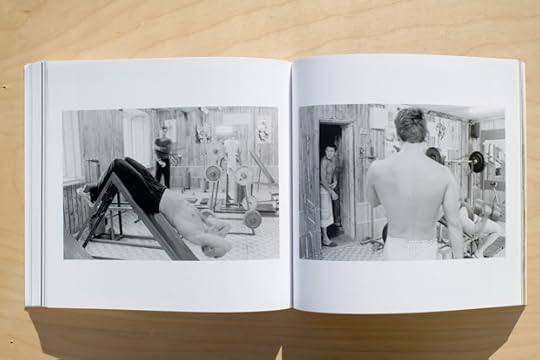

The Amnesia Pavilions chronicles Nicholas Muellner’s 1990 and 1992 trips to a small town in post-Soviet Russia and his subsequent return in 2009, in search of a boy he had met there nineteen years earlier. The boy is named Aleksei Tsvetkov, and it’s a love story. It is also a book that speaks to my own obsessive photographic road trips, as I constantly retrace steps I made in previous years, frantically looking for something in the same places I’ve already checked.

Three distinct photographic vocabularies are in operation. The photographs from the early ’90s are made with a hungry eye, strong faith in photography’s ability to tell a humanist story, and the visceral physicality of young Russian men. Next are snapshots that Tsvetkov sent Muellner in the intervening years. Their contingency as cultural artifacts imbues them with an aura of authenticity, but they seem standoffish, offering evidence of Tsvetkov’s life carried on in Muellner’s absence. The final pictures made in 2009 deliver the stuff of the world with a taxonomical and formal eloquence. Here, remarkably unremarkable buildings and listless saplings are at once indifferent to this story and inextricably marked by it.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes that the picture of his mother “fulfill[s] Nietzsche’s prophecy: ‘A labyrinthine man never seeks truth, but only his Ariadne.’ The Winter Garden Photograph was my Ariadne, not because it would help me discover a secret thing (monster or treasure), but because it would tell me what constituted that thread which drew me towards Photography.”

In the accompanying text, Muellner sets his memory of Tsvetkov against a contemplation of photography, moving from the crushing disappointment of Tsvetkov’s disappearance to the introspective unveiling of self-knowledge. Muellner describes the suppressed eroticism he felt in Tsvetkov’s presence and the pathos he sank to in his absence. In reading Muellner’s book, I feel a strange inversion, where I’m the one looking for Tsvetkov. Every adventure I’ve ever had with love and photography has ended in a similar misadventure. As is often the case, the rush of longing detaches from its object of desire, and my photographic ghosts only lead me back to myself, alone.

—

Justine Kurland was born in 1969 in Warsaw, New York. Her photographs have been exhibited extensively at museums and galleries in the U.S. and internationally.

The post PhotoBook Lust: Justine Kurland on Nicholas Muellner, The Amnesia Pavilions appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 20, 2014

Aperture #215—Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

View of São Paulo and Copan building, 2013. Photograph by Tuca Vieira

Was photography invented in Brazil? Possibly, according to the story of Hercule Florence, a tireless inventor and adventurer who pioneered an early form of photography in the 1830s. More likely, photography was invented simultaneously in many places, but Florence’s Herzogian story of entrepreneurial tenacity and Amazonian exploration gone awry is largely absent from the more familiar narratives of European figures attempting to fix light and shadow.

This São Paulo Issue is based on two extended visits to Brazil last autumn and winter. We wanted to expand our purview to find stories like Florence’s, told here by Natalia Brizuela. Working with guest editor Thyago Nogueira, editor of Zum magazine and curator of contemporary photography at the Instituto Moreira Salles, one of Brazil’s leading photography institutions, we visited dozens of photographers, writers, and curators. We came to better understand a history of photography largely untold in the United States—one mostly new to us—and were introduced to a vibrant contemporary scene supported by a growing network of museums, galleries, and emerging alternative spaces.

“Within cities like São Paulo there exist countless worlds that can be peeled away, layer by layer, to reveal hidden lives,” Cassiano Elek Machado writes in these pages. With a population pushing twenty million, São Paulo extends vertiginously in all directions. A single magazine issue can only hope to peel back a few layers of curatorial and research activity, but in these pages you’ll find a cross section of ideas and projects, an almost even split between historical and contemporary.

Waves of immigration shaped São Paulo, and its transnational story is evident in Sérgio Burgi’s panoramic overview of the city’s artistic activity across the twentieth century, and in Claudia Andujar’s extraordinary story of fleeing Eastern Europe during the Second World War. Russian émigré Gregori Warchavchik’s Casa Modernista appears on our cover in Caio Reisewitz’s lush image. Modernism’s enduring legacy and a fluid intersection of photography and design thread the issue—from Geraldo de Barros’s diverse practice (from photography to furniture design) to Mauro Restiffe’s tribute to legendary architect Oscar Niemeyer. With the exception of Bárbara Wagner and Jonathas de Andrade, each artist featured in the issue has roots in São Paulo. These two figures (whose work we discovered on view in São Paulo) may be more associated with the northern city of Recife, but their work taps into important areas of Brazilian culture and history—performance groups embodying Afro-Brazilian traditions and the years of military dictatorship, respectively.

Last year’s social unrest, born out of debates about inequality in Brazil’s fast-growing economy, played out dramatically as large-scale street demonstrations across the country. Politically engaged photography collectives, such as Mídia Ninja, were active in documenting the protests predicted to resume this summer when Brazil assumes the global spotlight as World Cup host. These forward-thinking collectives are redrawing the media landscape. Ronaldo Entler, in his overview of this phenomenon, notes how these groups “prove that it is possible to reinvent photography in times of crisis.” It seems as long as photography has been around, it has been invented and reinvented in Brazil. This is the first time Aperture has embedded in a city abroad to uncover narratives of photography from a different perspective; we hope it will be the first of many.

—The Editors

The post Aperture #215—Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers