Aperture's Blog, page 178

June 24, 2014

Robert Capa in Color: the Photographer Inside Life

Roberto Saviano, author of the bestselling title Gomorrah, comments on the color work of Robert Capa in Capa in Color, an exhibition on view at the International Center of Photography January 31–May 4, 2014. This review first appeared in La Repubblica on April 13, 2014.

Robert Capa, [Capucine, French model and actress, on a balcony, Rome], August 1951. © Robert Capa/International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos.

NEW YORK – As a young boy, in contests to see who could hold their breath the longest, he got as far as three minutes. It’s a mental discipline, and if you succeed in holding your breath, in not giving in to the tyranny of the diaphragm, then you also succeed in controlling your emotions.

I arrive at the International Center of Photography in New York and breathe in through my nose, inhaling all the air I can, filling my lungs. Faced with images that, piece by piece, have constructed my worldview, I really don’t know if my vital functions will remain unaltered. Encountering Robert Capa’s photographs is like standing before work by Raphael or Caravaggio. All the images in your mind of the Second World War, of the American troops in Italy, of the war in Spain, of the Jews who survived the concentration camps, of the bombed out cities, in other words all those images hidden in some far-off corner of your memory, live within you because Robert Capa lived. A photojournalist who almost always had his camera handy and who never released the shutter without receiving an advance for an assignment.

At this point his most famous shots belong to our collective memory: the anarchist militiaman shot to death in the Spanish Civil War, perhaps his most cited photo; the mothers in mourning around the coffins of children from the Liceo Sannazaro who were killed fighting the Germans during the Four Days of Naples; blurry images of the Normandy landing, which inspired Spielberg for the opening sequences of Saving Private Ryan. These are, by definition, black and white photography, and this is why “Capa in Color,” the ICP exhibition that commemorates the one-hundredth anniversary of the photographer’s birth, delivers a sort of visual shock.

First of all there is the incredible image of Capucine, the stunning and unfortunate woman who committed suicide at age sixty-two. Incredible because you get so close to her, you feel the breath from her nostrils. Her chin resting on her hand, the light of Piazza di Spagna, her red shirt: this shot seems to already contain everything about her fate, and it offers proof that Capa’s art, with his eye, with his unique gaze, lays the foundation for a literary genre.

Robert Capa, [Young visitors waiting to see Lenin’s Tomb at Red Square, Moscow], 1947. © Robert Capa/International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos.

My education, everything I have written, everything written by the authors who have influenced me, derives directly from him. Literary, iconographic and cinematographic neorealism all draw on Robert Capa. His biographers describe this photographer, barely five feet three inches tall, as an indomitable lover, someone who would punctually disappear when the object of his love indicated that she wanted to tie him down, to share a life with him. He had also loved Ingrid Bergman, and indeed it was he who had introduced her to Rossellini, the Italian Neorealist filmmaker. The latter was inspired by Capa’s esthetic rigor, whereby he not only sought to unearth drama, but also its dangerous communicative beauty, in order to enable that drama to transform the observer. This is Capa’s most profound lesson for cinema. His work not only allowed us to construct an extremely personal and sumptuous mosaic. No, Capa did much more: he created literature and communication, in the most modern sense of the terms.

His way of shooting is neither denunciation nor indignation, nor an artistic choice; it is all three together. And this is true only because his glance – immersed in life, drenched in and sullied by life – implicates. Someone who is not afraid of life, not afraid of people. “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” according to his most well-known maxim. Getting inside things. This is precisely what Capa’s color photographs reveal: that he is not at war, but inside war, among the soldiers, so close he puts his own life at risk. And this is true for all his photography. Even when he shoots Truman Capote in Ravello, or Martha Gellhorn walking amid the ruins of the temple of Ceres in Paestum. He gets inside everything he photographs. Inside all the people he photographs.

His shots cost him eternal, deep hatred. He was never forgiven for the photograph of the anarchist militiaman, the authenticity of which has been questioned by an entire body of literature. Likewise he has never been forgiven for his color photographs of the Stalinist USSR, published with texts by John Steinbeck, detested by the communists because they are anti-communist and by the anti-communists because they are pro-communist. Whatever photos he shot, he knew that he would stir up instinctive reactions. He liked capturing images of the world and transforming the way people looked at the world.

Robert Capa, [Skier sunbathing in front of the Matterhorn, Zermatt, Switzerland], 1950. © Robert Capa/International Center of Photography/ Magnum Photos.

But the photographs I am seeing not only change my way of looking at the world; it is as if they were giving birth to an urgency, as if they were setting off an alarm: go back to looking at the world and don’t limit yourself to merely copying it, to extracting from everyday life some image or another in order to put it back in circulation, to bombard people with useless stills that saturate the glance but go no further. In fact, it isn’t enough to see these shots by Capa, it isn’t sufficient to look at them and then move on; one needs to stop and read them. In Holiday magazine Capa wrote: “I went back to photograph Budapest because I happened to have been born there; I was able to photograph Moscow, which is impossible for most people to do; I photographed Paris because I lived there before the war; London because I lived there during the war; and Rome because I was unhappy I had never seen it and instead would have liked to live there.” There are photographs of American families in Switzerland, in glossy tourist magazines, or those that were disseminated at travel agencies. There is Magnani during the shooting of Visconti’s Bellissima. Capa photographs everyone in every sort of situation, famous people and unknowns, without snobbery, because he wasn’t interested in playing a role — for him, the priority was to get inside life. He knew that observation entailed getting involved, and this didn’t scare him off.

He had learned from Gerda Taro, his companion. Gerda died at twenty-seven, struck by a “friendly” tank of the Republican Popular Front. She was looking into her camera while standing on the running board of a military vehicle. Hit, she fell and ended up beneath the wheels. In 1954, in Indochina, Robert Capa was also looking into his camera. He had decided to wait for a French military column that was advancing. He went up an embankment. Retreating, he stepped on a landmine. Gerda and Robert never distanced themselves from their subjects. And this getting inside, inside the eyes of the people in front of you, their muscle structure, the landscapes, the creases of a model’s glance, the pride and dissatisfaction of a bourgeois entrepreneur: all this is research. Capa photographs with an awareness that it is precisely when you begin to believe that life is shutting you out, that there is no point in seeking the truth, that you have lost the only chance to be truly alive, to be able to make an impression on this world. As soon as you decide to take one of the possible shortcuts, in order to mimic life, you have already lost. Robert Capa’s secret does not lie in the end product, but in the search, in the voyage, which cannot exist without completely implicating himself. The only salvation lies in getting inside what you want to understand. Getting inside life.

(Translated from the Italian by Marguerite Shore.)

—

Roberto Saviano is an Italian journalist and writer. He is the author of numerous publications, including Gomorrah (Mondadori, 2006), La bellezza e l’inferno (Beauty and the Inferno, Mondadori, 2009), and most recently Zero Zero Zero (Feltrinelli Editore, 2013). He is a regular contributor to La Repubblica.

Capa in Color will be on view at Fundación Mapfre, Madrid, June 28–September 7, 2014, and Museo dell’Ara Pacis, Rome, September 26, 2014–June 1, 2015.

The post Robert Capa in Color: the Photographer Inside Life appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 20, 2014

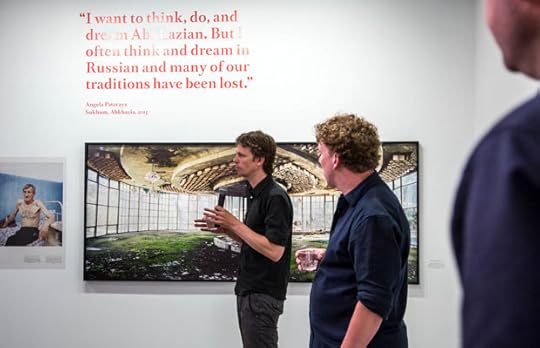

The Sochi Project: in Conversation (Video)

On June 3, 2014, we joined Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen at Aperture Gallery to discuss The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus. The project, on view until July 30, offers an alternative perspective and in-depth reporting on the remarkable Sochi region, which sits at the combustible crossroads of war, tourism, and history. Hornstra and van Bruggen have returned repeatedly to this region since 2009 as committed practitioners of “slow journalism,” establishing a solid foundation of research on and engagement with this small yet incredibly complicated place before it found itself in the glare of international media attention. Their book The Sochi Project was published by Aperture in 2013.

See “The Sochi Project: Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen in Conversation” Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 on Vimeo.

The post The Sochi Project: in Conversation (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 13, 2014

Groupshot: Mídia Ninja

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online. Return to Ronaldo Entler’s introduction to the Groupshot feature here.

Mídia Ninja, Barricade protesting the FIFA Confederations Cup Brazil, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2013, part of the project Ruas de Junho (June Streets) Courtesy Mídia Ninja

During the 2013 protests, Mídia Ninja became one of the most instrumental collectives to provide on-the-scene coverage: Several videos posted on Twitcast reached as many as one hundred thousand viewers. With a huge portfolio documenting conflict situations, they were able to confront major news providers whose coverage had been critical of the protests, forcing some to adjust their content and provide a more nuanced portrayal that included not only scenes of vandalism on the part of protesters but also scenes of police violence.

Ninja (a Portuguese acronym for Independent Narratives, Journalism, and Action) was formed in 2011 as a sideline of Fora do Eixo, a collective network created in 2005 to organize independent music festivals in several Brazilian cities. Part of Mídia Ninja’s know-how and strategy is a result of its work with these festivals. While Bruno Torturra, Pablo Capilé, Filipe Peçanha, and Rafael Vilela are some of the members who most often appear in public to discuss their projects, the collective estimates that there are nearly one hundred regular members and a network of as many as two thousand collaborators who can be mobilized across the country. Although known for their use of camera phones, many collaborators have, in fact, had solid audiovisual training.

Though made under a banner of independent journalism and media activism, work by the collective members has often been featured by mainstream news outlets, where it has been the subject of debate: Critics question whether their informal coverage qualifies as legitimate journalism. According to Vilela, Ninja’s projects have been funded primarily by social organizations that support the same causes. “We’re not looking to be impartial,” Vilela asserts, “what distinguishes us from the major platforms is the transparency with which we present points of view.” The group’s images are available for free downloading on Creative Commons and have been published in newspapers around the world. Aside from the alternative channels that they explore, the works produced by Ninja have also begun to exert a presence within the art circuit and are often featured in photography exhibitions and collections. Mídia Ninja is an evolving project. Its core membership recently relocated to Rio de Janeiro from São Paulo. With the World Cup approaching, Rio will be packed with tourists and journalists, as well as militants keeping an eye out for the social unrest that is often unleashed by such major events— and the collective will be well-positioned to witness, record, and disseminate.

Mídia Ninja, Monument occupied during popular protests, 23 de Maio Avenue, São Paulo, 2013, part of the project Ruas de Junho (June Streets) Courtesy Mídia Ninja

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot: Mídia Ninja appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot: SelvaSP

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online. Return to Ronaldo Entler’s introduction to the Groupshot feature here.

Drago, A hurt military police officer fends off attackers during the second protest against the bus-fare hikes in São Paulo, June 2013 © Drago/SelvaSP

SelvaSP, meaning São Paulo jungle, formed in 2012 with an entirely aesthetic objective: the revitalization of street photography. The group’s manifesto recalls the work of classical photographers and questions why critics have decided to view this genre as archaic. The collective, which still considers itself in a formative phase, currently has twelve members: Gabriel Cabral, Victor Dragonetti (Drago), Leo Eloy, Francisco Costa, Syã Fonseca, Gustavo Gomes, Paulo Marinuzzi, Rafael Mattar, Lucas Mello, Gustavo Morita, Padu Palmério, and Hudson Rodrigues.

Gustavo Gomes, from the series Plástico (Plastic), 2013 © Gustavo Gomes/SelvaSP

According to Gabriel Cabral, despite the group’s coverage of the 2013 protests, their photo essays are defined more by trying to capture everyday life in the city—neighborhood identities and the gestures and expressions of people on the street—than by urgent reporting on fast-breaking events. SelvaSP produces tightly edited photo essays, not the news.

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot: SelvaSP appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot: Garapa

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online. Return to Ronaldo Entler’s introduction to the Groupshot feature here.

Garapa, Ex-moradores do edifício Mercúrio (Former residents of the Mercúrio building), from the project Morar, 2011 Courtesy Garapa

Garapa takes its name from the Portuguese word for the sugarcane juice used to make, among other things, the distilled spirit cachaça. Formed in 2008 by photographers Rodrigo Marcondes, Paulo Fehlauer, and Leo Caobelli, the collective occupies an important role in Brazil’s cultural scene and is devoted to experimenting with new narrative forms. While encouraging members to complete their own projects outside of the group, Garapa maintains a solid roster of jointly realized projects.

Morar (2009–11), the group’s first effort, centered on the emptying and demolition of two contiguous buildings, São Vito and Mercúrio, during a somewhat suspect program of urban revitalization for the city’s downtown. Some of the group’s research was financed by crowdfunding, and the project made use of a wide range of techniques, from daguerreotype to video, and took a variety of forms: several exhibitions that included photographs and a short documentary, a tabloid-format publication, and a site-specific installation featuring portraits of former residents on the land where the two buildings once stood. According to Rodrigo Marcondes, the group’s recent works have drawn on new partnerships, and while still maintaining a documentary approach, they also utilize certain fictional elements. In Calma (2013), a work that included the collaboration of artists Lana Mesic and Thomas Kuijpers, the collective followed the fictitious story of Rolf, a Dutchman who had come to São Paulo in search of his missing father.

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot: Garapa appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot: FotoProtestoSP

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online. Return to Ronaldo Entler’s introduction to the Groupshot feature here.

Keiny Andrade, Demonstrators block traffic on 23 de Maio Avenue during a protest against raising public transportation fares, São Paulo, June 20, 2013. Courtesy FotoProtestoSP

One of the more stringent collectives to rise out of the unrest of 2013 is FotoProtestoSP. Its thirty members include several well-established veterans of Brazilian photojournalism, such as Maurício Lima, Marlene Bergamo, Fernando Costa Netto, Keiny Andrade, Ignácio Aronovich, and José Francisco Diório. Their manifesto radiates indignation with the country’s political structure and asserts a desire to explore the critical power of photography beyond private media platforms and art institutions. “We understand the urgency of not letting inertia take control of society and, in order to visually display our indignation, we will take over the public or empty spaces in São Paulo with our photographs,” their manifesto states.

Each member maintains his or her own working routine and no attempts are made to produce coverage specifically bearing a collective signature. According to Renato Stockler, one of the group’s members, its objective is to occupy the city’s leisure spaces and to remind residents of the power people have when they unite around a common cause. “It’s about giving back to the street what the street initially gave to photographers,” Stockler says. One of FotoProtestoSP’s most important actions involved wheatpasting two walls in downtown São Paulo with large-format photographs of the protests. Despite its relative newness, the important names attached to the group and the dramatic imagery produced have drawn much attention to their initiative.

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot: FotoProtestoSP appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot: Cia de Foto

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online. Return to Ronaldo Entler’s introduction to the Groupshot feature here.

Cia de Foto, from the project 911, 2006 (video still). Courtesy Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Cia de Foto, whose name means photo company, was the most influential of these collectives and served as a model and inspiration for other groups in Brazil, but in late 2013, it caused a commotion by posting a brief message on its Facebook page announcing its dissolution.

Cia de Foto emerged in 2003, spearheaded by photographers Pio Figueiroa, Rafael Jacinto, and João Kehl, and later incorporated image editor Carol Lopes. Eschewing photographic pamphleteering, the group’s presence within the framework of social debate was nonetheless apparent. One of its first projects, 911, focused on the occupation of a building in downtown São Paulo by a group of squatting homeless families. A newer project, Passe Livre, addressed the bus fare hikes of 2013. In recent years, the group began to direct its attention to a range of diverse subjects, sometimes assuming a more poetic approach (though the subject matter remained political in nature). One example is Marcha (2011/2013), which recorded the daily commute of workers through one of the city’s major train stations. By highlighting the dispersed yet unchanging nature of these commutes, the images suggest that masses of workers no longer represent a potent political force as they did in the past.

Cia de Foto was defined by its very structure as a collective and stirred some controversy by refusing ever to provide an individual’s signature on any of the works that it produced. As many important public and private collections acquired the group’s pieces, its structure grew to meet the demands of the market, and it led various art institutions to reformulate their own policies in order to acquire works of collective authorship. The group curated exhibitions, published books in experimental formats, and nurtured emerging artists. It also welcomed other collaborators. According to Pio Figueiroa, “It’s been more thought-provoking to share and encourage people to debate ideas than to simply sign off on a completed work.”

Several projects remain to be completed and the future of Cia de Foto’s immense image archive now seems uncertain. Despite the group’s breakup, Figueiroa has stated that he still sees collectives playing an important role in responding to the difficulties for professional development and to the lack of organization among Brazilian photographers.

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot: Cia de Foto appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot by Ronaldo Entler

The following feature first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Photography collectives with diverse styles and philosophies are transforming São Paulo’s media landscape through their documentation of last year’s massive street protests and by exploring everyday life in the megalopolis.

Photograph by Rafael Mattar of Selva SP. © Rafael Mattar/SelvaSP

In June 2013, mass demonstrations rocked Brazil. Protests against bus fare hikes, organized by the Movimento Passe Livre (Free Fare Movement), gained swift momentum, moving from one city to the next, absorbing other causes and attracting international attention. The demonstrations also triggered a media war. On one side, news reports highlighted scenes of protesters engaged in acts of vandalism. On the other, protesters captured excessive police violence. During this time, photography collectives played a key role, recording and supporting the protests. While the work of these groups, whose numbers have steadily grown over the past ten years, is hardly isolated to instances of political demonstrations, this particular moment of upheaval exemplified the collaborative impulse that fuels them.

Brazilian photography collectives are forging alternatives to image banks and news agencies. Even when their style veers toward photojournalism, or even commercial advertising, photography collectives’ projects assume the form of social or political engagement. Generally made up of young photographers, they embrace social media and online networks and have little interest in traditional models based on solitary authorship.

The phenomenon is hardly unique to Brazil. Marked by their own aesthetic decisions and approaches, many such groups have formed across the globe, often united by specific collaborative projects. Such is the case with Blank Paper and Pandora (Spain), Kameraphoto (Portugal), Luceo (United States), Mondaphoto (Mexico), and Supayfotos (Peru). There are, however, certain historical precedents specific to Brazil, such as the photo-clubs established in various cities in the mid-twentieth century, or the independent photography agencies that have sprung up since the 1970s—such as Fotocontexto, F4, and Ágil—and cultural initiatives such as Fotoativa, an important educational project founded in Belém do Pará in 1984.

Today’s new collectives encompass a wide range of approaches but share a proclivity toward political confrontation. Their political engagement is reflected in how the groups have sought alternative models for managing and disseminating images and information. By mining social networks, they explore new paths for financial survival and dialogue with curators, critics, and other cultural producers. By banding together, these collectives assert a clear ideological and aesthetic identity and produce projects of great depth while also constructing spaces for the distribution of works not absorbed by the mass media. In some cases, they gain access to the art circuit or publishing and advertising markets, which are attracted by the gritty glamour of a language forged outside the mainstream.

Mapping São Paulo’s collectives is no easy task. Many of these groups meet only sporadically and tend to be short-lived, but what follows is a selection of some of the most important ones recently working in the city. It would be difficult to conceive of these collectives as part of a broader, cohesive movement, or to suppose that the future of photography is necessarily headed in the direction of collective authorship. Many of the groups have been temporary, and others are still too new to assess their impact. Nevertheless, these collectives have demonstrated their power. Restlessness is one of the unique qualities of any group formed by diverse points of view and desires. They have proven that it is possible to reinvent photography during times of crisis.

Cia de Foto

Cia de Foto, from the project 911, 2006 (video still). Courtesy Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Cia de Foto, whose name means photo company, was the most influential of these collectives and served as a model and inspiration for other groups in Brazil, but in late 2013, it caused a commotion by posting a brief message on its Facebook page announcing its dissolution.

Cia de Foto emerged in 2003, spearheaded by photographers Pio Figueiroa, Rafael Jacinto, and João Kehl, and later incorporated image editor Carol Lopes. Eschewing photographic pamphleteering, the group’s presence within the framework of social debate was nonetheless apparent. One of its first projects, 911, focused on the occupation of a building in downtown São Paulo by a group of squatting homeless families. A newer project, Passe Livre, addressed the bus fare hikes of 2013. In recent years, the group began to direct its attention to a range of diverse subjects, sometimes assuming a more poetic approach (though the subject matter remained political in nature). One example is Marcha (2011/2013), which recorded the daily commute of workers through one of the city’s major train stations. By highlighting the dispersed yet unchanging nature of these commutes, the images suggest that masses of workers no longer represent a potent political force as they did in the past.

Cia de Foto was defined by its very structure as a collective and stirred some controversy by refusing ever to provide an individual’s signature on any of the works that it produced. As many important public and private collections acquired the group’s pieces, its structure grew to meet the demands of the market, and it led various art institutions to reformulate their own policies in order to acquire works of collective authorship. The group curated exhibitions, published books in experimental formats, and nurtured emerging artists. It also welcomed other collaborators. According to Pio Figueiroa, “It’s been more thought-provoking to share and encourage people to debate ideas than to simply sign off on a completed work.”

Several projects remain to be completed and the future of Cia de Foto’s immense image archive now seems uncertain. Despite the group’s breakup, Figueiroa has stated that he still sees collectives playing an important role in responding to the difficulties for professional development and to the lack of organization among Brazilian photographers.

Garapa

Garapa, Ex-moradores do edifício Mercúrio (Former residents of the Mercúrio building), from the project Morar, 2011 Courtesy Garapa

Garapa takes its name from the Portuguese word for the sugarcane juice used to make, among other things, the distilled spirit cachaça. Formed in 2008 by photographers Rodrigo Marcondes, Paulo Fehlauer, and Leo Caobelli, the collective occupies an important role in Brazil’s cultural scene and is devoted to experimenting with new narrative forms. While encouraging members to complete their own projects outside of the group, Garapa maintains a solid roster of jointly realized projects.

Morar (2009–11), the group’s first effort, centered on the emptying and demolition of two contiguous buildings, São Vito and Mercúrio, during a somewhat suspect program of urban revitalization for the city’s downtown. Some of the group’s research was financed by crowdfunding, and the project made use of a wide range of techniques, from daguerreotype to video, and took a variety of forms: several exhibitions that included photographs and a short documentary, a tabloid-format publication, and a site-specific installation featuring portraits of former residents on the land where the two buildings once stood. According to Rodrigo Marcondes, the group’s recent works have drawn on new partnerships, and while still maintaining a documentary approach, they also utilize certain fictional elements. In Calma (2013), a work that included the collaboration of artists Lana Mesic and Thomas Kuijpers, the collective followed the fictitious story of Rolf, a Dutchman who had come to São Paulo in search of his missing father.

FotoProtestoSP

Keiny Andrade, Demonstrators block traffic on 23 de Maio Avenue during a protest against raising public transportation fares, São Paulo, June 20, 2013. Courtesy FotoProtestoSP

One of the more stringent collectives to rise out of the unrest of 2013 is FotoProtestoSP. Its thirty members include several well-established veterans of Brazilian photojournalism, such as Maurício Lima, Marlene Bergamo, Fernando Costa Netto, Keiny Andrade, Ignácio Aronovich, and José Francisco Diório. Their manifesto radiates indignation with the country’s political structure and asserts a desire to explore the critical power of photography beyond private media platforms and art institutions. “We understand the urgency of not letting inertia take control of society and, in order to visually display our indignation, we will take over the public or empty spaces in São Paulo with our photographs,” their manifesto states.

Each member maintains his or her own working routine and no attempts are made to produce coverage specifically bearing a collective signature. According to Renato Stockler, one of the group’s members, its objective is to occupy the city’s leisure spaces and to remind residents of the power people have when they unite around a common cause. “It’s about giving back to the street what the street initially gave to photographers,” Stockler says. One of FotoProtestoSP’s most important actions involved wheatpasting two walls in downtown São Paulo with large-format photographs of the protests. Despite its relative newness, the important names attached to the group and the dramatic imagery produced have drawn much attention to their initiative.

SelvaSP

Drago, A hurt military police officer fends off attackers during the second protest against the bus-fare hikes in São Paulo, June 2013 © Drago/SelvaSP

SelvaSP, meaning São Paulo jungle, formed in 2012 with an entirely aesthetic objective: the revitalization of street photography. The group’s manifesto recalls the work of classical photographers and questions why critics have decided to view this genre as archaic. The collective, which still considers itself in a formative phase, currently has twelve members: Gabriel Cabral, Victor Dragonetti (Drago), Leo Eloy, Francisco Costa, Syã Fonseca, Gustavo Gomes, Paulo Marinuzzi, Rafael Mattar, Lucas Mello, Gustavo Morita, Padu Palmério, and Hudson Rodrigues.

Gustavo Gomes, from the series Plástico (Plastic), 2013 © Gustavo Gomes/SelvaSP

According to Gabriel Cabral, despite the group’s coverage of the 2013 protests, their photo essays are defined more by trying to capture everyday life in the city—neighborhood identities and the gestures and expressions of people on the street—than by urgent reporting on fast-breaking events. SelvaSP produces tightly edited photo essays, not the news.

Mídia Ninja

Mídia Ninja, Barricade protesting the FIFA Confederations Cup Brazil, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2013, part of the project Ruas de Junho (June Streets) Courtesy Mídia Ninja

During the 2013 protests, Mídia Ninja became one of the most instrumental collectives to provide on-the-scene coverage: Several videos posted on Twitcast reached as many as one hundred thousand viewers. With a huge portfolio documenting conflict situations, they were able to confront major news providers whose coverage had been critical of the protests, forcing some to adjust their content and provide a more nuanced portrayal that included not only scenes of vandalism on the part of protesters but also scenes of police violence.

Ninja (a Portuguese acronym for Independent Narratives, Journalism, and Action) was formed in 2011 as a sideline of Fora do Eixo, a collective network created in 2005 to organize independent music festivals in several Brazilian cities. Part of Mídia Ninja’s know-how and strategy is a result of its work with these festivals. While Bruno Torturra, Pablo Capilé, Filipe Peçanha, and Rafael Vilela are some of the members who most often appear in public to discuss their projects, the collective estimates that there are nearly one hundred regular members and a network of as many as two thousand collaborators who can be mobilized across the country. Although known for their use of camera phones, many collaborators have, in fact, had solid audiovisual training.

Though made under a banner of independent journalism and media activism, work by the collective members has often been featured by mainstream news outlets, where it has been the subject of debate: Critics question whether their informal coverage qualifies as legitimate journalism. According to Vilela, Ninja’s projects have been funded primarily by social organizations that support the same causes. “We’re not looking to be impartial,” Vilela asserts, “what distinguishes us from the major platforms is the transparency with which we present points of view.” The group’s images are available for free downloading on Creative Commons and have been published in newspapers around the world. Aside from the alternative channels that they explore, the works produced by Ninja have also begun to exert a presence within the art circuit and are often featured in photography exhibitions and collections.

Mídia Ninja is an evolving project. Its core membership recently relocated to Rio de Janeiro from São Paulo. With the World Cup approaching, Rio will be packed with tourists and journalists, as well as militants keeping an eye out for the social unrest that is often unleashed by such major events— and the collective will be well-positioned to witness, record, and disseminate.

Mídia Ninja, Monument occupied during popular protests, 23 de Maio Avenue, São Paulo, 2013, part of the project Ruas de Junho (June Streets) Courtesy Mídia Ninja

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program.

The post Groupshot

by Ronaldo Entler appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Groupshot: Introduction by Ronaldo Entler

The following feature first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Photography collectives with diverse styles and philosophies are transforming São Paulo’s media landscape through their documentation of last year’s massive street protests and by exploring everyday life in the megalopolis.

Photograph by Rafael Mattar of Selva SP. © Rafael Mattar/SelvaSP

In June 2013, mass demonstrations rocked Brazil. Protests against bus fare hikes, organized by the Movimento Passe Livre (Free Fare Movement), gained swift momentum, moving from one city to the next, absorbing other causes and attracting international attention. The demonstrations also triggered a media war. On one side, news reports highlighted scenes of protesters engaged in acts of vandalism. On the other, protesters captured excessive police violence. During this time, photography collectives played a key role, recording and supporting the protests. While the work of these groups, whose numbers have steadily grown over the past ten years, is hardly isolated to instances of political demonstrations, this particular moment of upheaval exemplified the collaborative impulse that fuels them.

Brazilian photography collectives are forging alternatives to image banks and news agencies. Even when their style veers toward photojournalism, or even commercial advertising, photography collectives’ projects assume the form of social or political engagement. Generally made up of young photographers, they embrace social media and online networks and have little interest in traditional models based on solitary authorship. The phenomenon is hardly unique to Brazil. Marked by their own aesthetic decisions and approaches, many such groups have formed across the globe, often united by specific collaborative projects. Such is the case with Blank Paper and Pandora (Spain), Kameraphoto (Portugal), Luceo (United States), Mondaphoto (Mexico), and Supayfotos (Peru). There are, however, certain historical precedents specific to Brazil, such as the photo-clubs established in various cities in the mid-twentieth century, or the independent photography agencies that have sprung up since the 1970s—such as Fotocontexto, F4, and Ágil—and cultural initiatives such as Fotoativa, an important educational project founded in Belém do Pará in 1984.

Today’s new collectives encompass a wide range of approaches but share a proclivity toward political confrontation. Their political engagement is reflected in how the groups have sought alternative models for managing and disseminating images and information. By mining social networks, they explore new paths for financial survival and dialogue with curators, critics, and other cultural producers. By banding together, these collectives assert a clear ideological and aesthetic identity and produce projects of great depth while also constructing spaces for the distribution of works not absorbed by the mass media. In some cases, they gain access to the art circuit or publishing and advertising markets, which are attracted by the gritty glamour of a language forged outside the mainstream.

Mapping São Paulo’s collectives is no easy task. Many of these groups meet only sporadically and tend to be short-lived, but what follows is a selection of some of the most important ones recently working in the city. It would be difficult to conceive of these collectives as part of a broader, cohesive movement, or to suppose that the future of photography is necessarily headed in the direction of collective authorship. Many of the groups have been temporary, and others are still too new to assess their impact. Nevertheless, these collectives have demonstrated their power. Restlessness is one of the unique qualities of any group formed by diverse points of view and desires. They have proven that it is possible to reinvent photography during times of crisis.

Part 1 – Groupshot: Cia de Foto

Part 2 – Groupshot: Garapa

Part 3 – Groupshot: FotoProtestoSP

Part 4 – Groupshot: SelvaSP

Part 5 – Groupshot: Mídia Ninja

—

Ronaldo Entler, a researcher and photography critic, is a professor at the School of Communication of Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), in São Paulo, where he is also the graduate coordinator of the school’s masters of photography program. Read his introduction to the Groupshot section of the issue here.

The post Groupshot:

Introduction by Ronaldo Entler appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 10, 2014

Recap: The Sochi Project Opening Reception

On Wednesday, June 4, Aperture Members and friends were the first to view Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen’s exhibition The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus at Aperture Gallery. Hornstra and van Bruggen gave Members an exclusive tour.

The exhibition is on view through July 10, 2014. The accompanying publication, The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus, was published by Aperture in 2013.

Membership at Aperture is about seeing it first. Engage with our talented photographers, writers, and editors at a variety of events like this by becoming an Aperture Member today! For more information, e-mail membership@aperture.org.

All images © Katie Booth.

The post Recap: The Sochi Project Opening Reception appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers