Aperture's Blog, page 174

October 8, 2014

i-D, Jill, and The Face: Fashion’s Maverick Magazines

by Phil Bicker

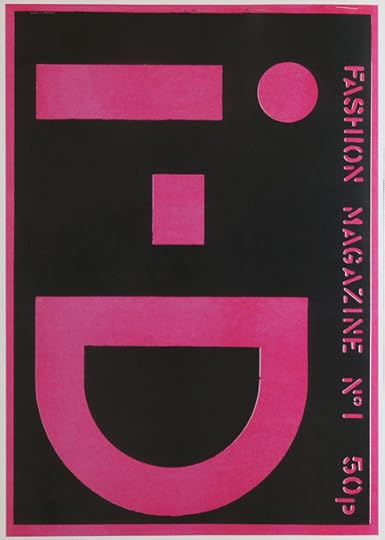

Pages from i-D no. 1, August 1980, “Straight-Up.” Photographs by Steven Johnston

The year 1980 saw the birth in London of The Face and i-D, two independently published and quintessentially British magazines. i-D was the invention of former British Vogue art director Terry Jones, and The Face was created by former NME (New Musical Express) editor Nick Logan. These new publications signaled a bold, catalytic moment in magazine publishing, offering an escape from the constraints of mainstream media for their founders and a platform for instinctive self-expression for their contributors. As the last vestiges of punk waned and transitioned to New Wave and then New Romantic, the first issue of The Face was produced and launched by Logan using his personal savings, and i-D’s early landscape-format issues (with silk-screened graphic covers) were designed and distributed in small runs in keeping with punk’s DIY mantra and post-punk aesthetic. Both magazines covered similar facets of youth culture; however, given the respective backgrounds of their founders, it was unsurprising that from the outset The Face was music focused, while i-D was more interested in fashion. The first issues of i-D introduced the “Straight-Up”—formal full-length street portraits photographed against blank urban walls—that documented the personal and individual style of British youth. While many of the photographers responsible for those early images remain as little known as the majority of the passing strangers they documented, the names of other early contributors would become more familiar. As i-D’s format rotated from landscape to portrait, Nick Knight made its first “photographic” cover, featuring Sade, and Marc Lebon made the second, featuring Madonna.

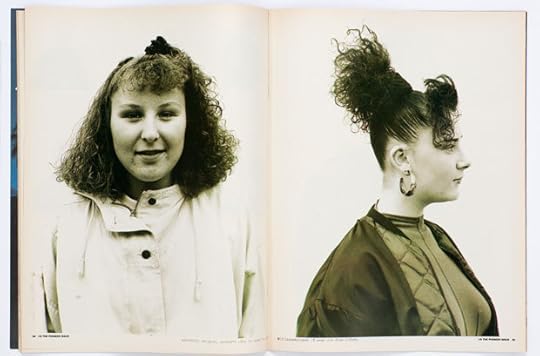

Both photographers would become i-D regulars, integral to the magazine’s evolution. Lebon’s work was raw and visceral, an experimental mash-up, fashion photography without boundaries. Knight’s tireless creative contribution—one of his stories, art-directed by Marc Ascoli, was aptly titled “In Pursuit of Excellence”—was as inspiring as it was pivotal. For the magazine’s fifth anniversary issue, Knight created a series of one hundred portraits, a styled topology of Britain’s rich history of tribal youth culture, signaling the photographer’s constant inventive hunger; he continued to produce dozens of fashion stories, more often than not made with his trusted collaborator, stylist Simon Foxton. Along with the contributions of stylists Judy Blame, Caroline Baker, and Ray Petri, these and other stories over the next halfdecade augmented and magnified street style, taking the magazine to another level.

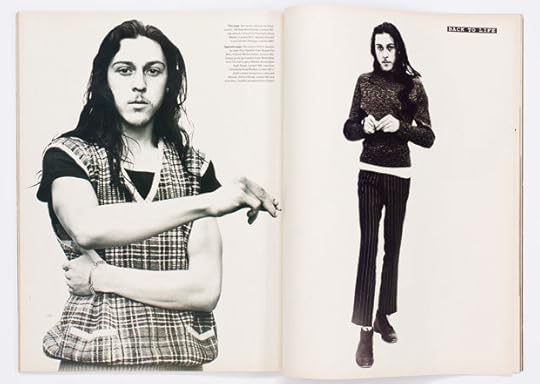

Pages from The Face no. 26, November 1990, “Back to Life.” Photographs by David Sims, styling by Melanie Ward

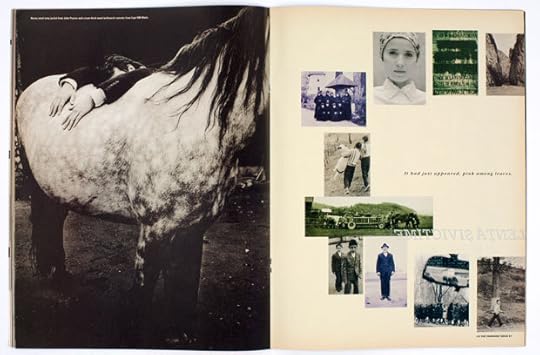

Pages from i-D no. 83, August 1990, “Romania—Paradise Lost?” Photographs by Juergen Teller; styling by Venetia Scott

Pages from i-D no. 110, November 1992, “Like Brother Like Sister: A Fashion Story.” Photographs and styling by Wolfgang Tillmans

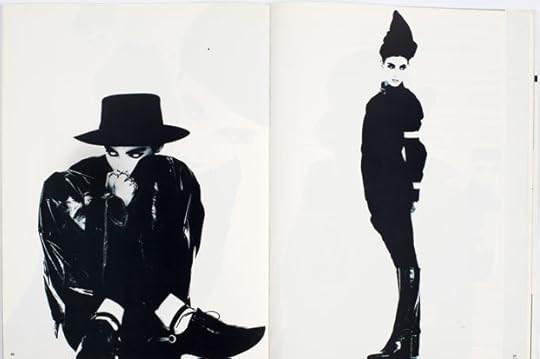

Pages from i-D no. 39, August 1986, “Pose!” Photographs by Nick Knight, styling by Simon Foxton

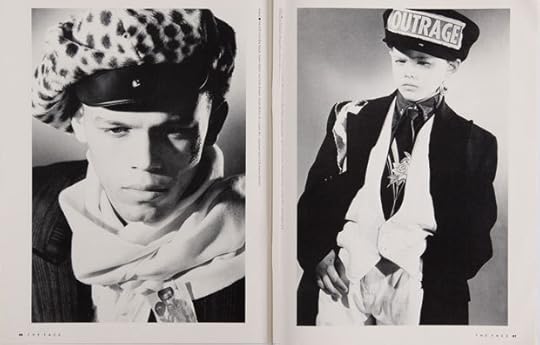

The early issues of The Face inherently touched on style in their portrayals of musicians, but the magazine’s fashion coverage was, at least in its formative issues, less overt. While the irreverent i-D embodied the spirit of its logo—a wink and a smile—The Face took a more classical approach to cool. As the publication found its audience and confidence, the experimental graphics and custom typography of designer Neville Brody defined the magazine’s identity, framed its content, and spread its influence. As the publication moved beyond its music roots, it took more risks. The Face chose “style” over “fashion,” and stylist Helen Roberts initiated the magazine’s evolution with photographer Jamie Morgan. Other stylists followed—Joe McKenna, Michael Roberts, Caroline Baker, and Debbie Mason among them—but none would have the impact or lasting influence of Ray Petri, or “Sting Ray,” as he first chose to be credited. Petri was the godfather and unquestionably the leader of the creative West London “Buffalo” collective, a group of photographers (including Jamie Morgan and Marc Lebon), stylists (including Mitzi Lorenz), musicians (Neneh Cherry, Nick Kamen), artists (Barry Kamen), and models (including a fourteenyear-old Naomi Campbell), who brashly defined the look of ’80s youth culture.

Petri made the MA-1 bomber jacket ubiquitous and mixed secondhand clothes and Army surplus, skiwear, sportswear, and accessories to create a brave new world of street style, urban cowboys, rude boys and ragamuffins, men in boxer shorts, collaged gangsters, and even men in skirts. He made the radical desirable and the outrageous believable, until his career was cut short when he died in August 1989 of AIDS. His legacy would include his later work with photographer Norman Watson for Arena, but it was his original vision and idiosyncratic styling, photographed by Jamie Morgan, that provided The Face with its first “style” cover—a photograph that publisher Nick Logan would later describe as a “fuck-off image from another planet”—and some of the magazine’s most memorable stories, iconic covers, and “Killer” images. “New,” “Hard,” “Bold,” the cover lines rang out; “Buffalo: The Harder They Come the Better,” one portfolio’s introductory text announced.

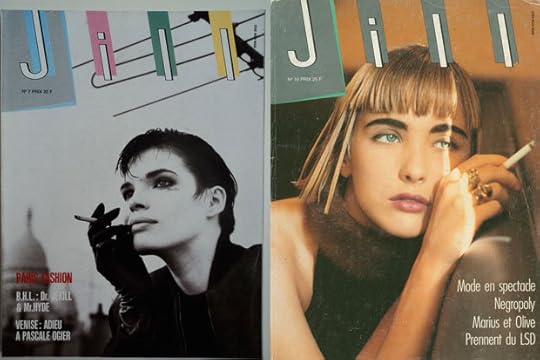

While Petri reimagined British style, the short-lived Jill magazine in Paris, under the direction of stylist Elisabeth “Babeth” Dijan, also embraced liberty, and the spirit of the new. As French as i-D and The Face were British, the independently published Jill was more fashion-centric but no less influential. The magazine was alternately at times a little softer and romantic, and at times a little darker and fantastic than its English counterparts. In its short run of eleven issues, published between 1983 and 1985, Dijan’s inspired vision and styling and the photography of her contributors, including Peter Lindbergh, Jean-Baptiste Mondino, Jean-François Lepage, and a young Ellen von Unwerth, embraced the work of Jean Paul Gaultier and his generation of young French designers who turned the fashion world’s attention once more firmly back to Paris.

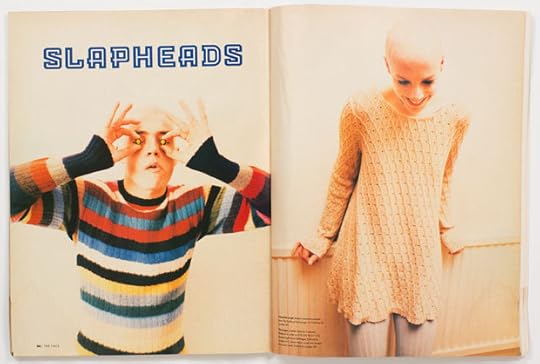

Pages from The Face no. 32, May 1991, “Slapheads.” Photographs by Corinne Day; styling by Melanie Ward

Pages from i-D no. 88, January 1991, “Teenage Precinct Shoppers.” Photographs by Nigel Shafran; styling by Melanie Ward

i-D no. 1, August 1980. Cover design by Terry Jones

A year after Jill folded, Dijan’s distinctive styling was featured in a special Paris issue of The Face. By the end of the ’80s Dijan had contributed a series of highly stylized fashion stories to the magazine, including the twenty-six-page comic-bookinspired opus, “Fashion Heroes,” with photographer Stephane Sednaoui. The story featured designers Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Martine Sitbon, Vivienne Westwood, Azzedine Alaïa, and a fantastical, intricately collaged series of images that preempted the digital era.

As the decade turned, a new generation of photographers, including David Sims and Corinne Day, and stylists, including Melanie Ward, emerged. Both Knight as photo editor at i-D and I as art director at The Face, nurtured and published their work. Inspired by rave music and, later, “grunge,” the pared-down photographs related more to personal style and self expression than to manufactured fantasy for commercial ends.

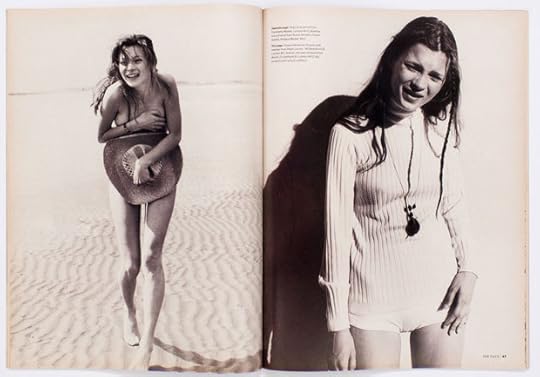

The images that appeared in The Face and i-D at the time were an antidote to fashion’s high glamour and excess. In the summer of 1990, The Face ran an eight-page black-and-white story featuring a sixteen-yearold, then-unknown model, Kate Moss, and put her on the cover. The antithesis of the supermodel, the thin and refreshingly natural Moss stood just five-foot-seven. Photographed by Corinne Day and styled by Melanie Ward at England’s Camber Sands beach, in feather headdress, Birkenstocks, cheesecloth, and daisy chains, Moss challenged the prevalent concept of beauty and, in doing so, embodied a new attitude and spirit for the age.

Simultaneously, David Sims further challenged mainstream ideals and archetypes, photographing a story for The Face in 1990 that featured a lank-haired, unlikely “model” named Rev against a stark white studio background. Styled by Ward and choreographed by Sims, Rev looked like a gypsy, clad in his own ill-fitting secondhand pinstripes and knitwear, as he alternately floated, posed, and cut a graphic figure. In another key 1990 story that ran in i-D, stylist Venetia Scott and photographer Juergen Teller traveled across Romania, dressing and photographing real people of various ages they encountered to produce a wonderfully nuanced, understated, and ultimately unfashionable fashion story. And, recalling and refining the simple approach of i-D’s early “Straight-Ups,” Nigel Shafran in 1991 photographed the personal style of “Teenage Precinct Shoppers” unadorned.

Pages from The Face no. 22,

July 1990, “The Daisy Age.” Photographs by Corinne Day; styling by Melanie Ward

Pages from The Face no. 59, March 1985, “The Harder They Come.” Photographs by Jamie Morgan; styling by Ray Petri

Pages from Jill no. 8, February 1985, “ J’suis snob” (I’m a snob). Photographs by J.-J. Castres; art direction by Mitzi Lorenz

Jill no. 7, and Jill no. 10

These photographs, especially those by Day and Sims, made waves. A startled fashion world—unable to comprehend the casting, styling, or aesthetic—was at first caustic and dismissive. But the work could not be ignored. It was exciting, new, and challenging. Eventually the contagious individual visions of nonconformity made an impact on the mainstream and became a fashionable way of photographing fashion.

Both i-D and The Face continued their creative celebration of intuition, instinct, and individuality; Wolfgang Tillmans emerged through the pages of i-D in 1992 to blur and break down the boundaries between art and fashion photography, and The Face published pioneering stories by Inez & Vinoodh in 1994 and Elaine Constantine in 1997, before eventually folding in 2004. But despite both magazines’ years of commercial and cultural success, the spirit of originality and global influence that defined their work in the late ’80s and early ’90s would never be surpassed.

_____

Phil Bicker, a creative director, designer, and photography editor, was the art director of The Face from 1987 to 1991.

The post i-D, Jill, and The Face:

Fashion’s Maverick Magazines appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 5, 2014

Elinor Carucci: Finding the Universal in Photographic Narratives

Elinor Carucci, The woman that I still am 2, 2010

Join Elinor Carucci for this critique-based workshop designed to aid those who wish to observe, consider, and respond to the world around them with a camera—creating work that, while specific to the story at hand, is also universal. This workshop will enable students to enhance their vision and style while delving deeper into the emotions, layers, and nuances of their images. On the first day, Carucci will briefly introduce her own approach to storytelling in both her personal and editorial work, followed by a critique and discussion of each student’s current portfolio and recommendations for how to bring their project to the next level. New directions will be identified and assignments given for the next class meeting, occurring four weeks later to allow time for each student to make work in response to their particular assignment. Subjects and styles distinct from Carucci’s own work are very welcome, as is commercial/editorial work.

Please bring one or more bodies of work that can serve as a starting point, or that you want to expand and develop. Please bring a minimum of 25 prints or digital files.

Elinor Carucci (born in Jerusalem, 1971) graduated in 1995 from Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design with a degree in photography, then moved to New York that same year. She has had solo shows at Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York; Gallery Fifty One, Antwerp; and James Hyman Gallery and Gagosian Gallery, both in London, among others. She has also been included in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Photographers’ Gallery, London. Her photographs are included in the collections of institutions such as MoMA, Brooklyn Museum, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and her work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, Details, New York, W, Aperture, ARTnews, and many more publications. She was awarded the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for a Young Photographer in 2001, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2002, and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in 2010. Carucci has published three monographs to date: Mother (2013), Diary of a Dancer (2005), and Closer (2002). Carucci currently teaches at the photography graduate program at the School of Visual Arts, New York, and is represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery.

Watch Elinor Carucci’s Artist Talk, which she presented at Aperture Gallery on March 6, 2014.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

Terms and Conditions

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older. If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Elinor Carucci: Finding the Universal in Photographic Narratives appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Workshop: Finding the Universal in Photographic Narratives with Elinor Carucci

Elinor Carucci, The woman that I still am 2, 2010

Join Elinor Carucci for this critique-based workshop designed to aid those who wish to observe, consider, and respond to the world around them with a camera—creating work that, while specific to the story at hand, is also universal. This workshop will enable students to enhance their vision and style while delving deeper into the emotions, layers, and nuances of their images. On the first day, Carucci will briefly introduce her own approach to storytelling in both her personal and editorial work, followed by a critique and discussion of each student’s current portfolio and recommendations for how to bring their project to the next level. New directions will be identified and assignments given for the next class meeting, occurring four weeks later to allow time for each student to make work in response to their particular assignment. Subjects and styles distinct from Carucci’s own work are very welcome, as is commercial/editorial work.

Please bring one or more bodies of work that can serve as a starting point, or that you want to expand and develop. Please bring a minimum of 25 prints or digital files.

Elinor Carucci (born in Jerusalem, 1971) graduated in 1995 from Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design with a degree in photography, then moved to New York that same year. She has had solo shows at Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York; Gallery Fifty One, Antwerp; and James Hyman Gallery and Gagosian Gallery, both in London, among others. She has also been included in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Photographers’ Gallery, London. Her photographs are included in the collections of institutions such as MoMA, Brooklyn Museum, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and her work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, Details, New York, W, Aperture, ARTnews, and many more publications. She was awarded the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for a Young Photographer in 2001, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2002, and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in 2010. Carucci has published three monographs to date: Mother (2013), Diary of a Dancer (2005), and Closer (2002). Carucci currently teaches at the photography graduate program at the School of Visual Arts, New York, and is represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery.

Watch Elinor Carucci’s Artist Talk, which she presented at Aperture Gallery on March 6, 2014.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

Terms and Conditions

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older. If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Workshop: Finding the Universal in Photographic Narratives with Elinor Carucci appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 3, 2014

Joel Meyerowitz on The Open Road (video)

Hear from photographer Joel Meyerowitz, whose photographs are featured in Aperture’s forthcoming publication The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip. From his backyard in Tuscany, Meyerowitz reflects on his time on the road as a photographer.

The Open Road shares its theme with The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction, an evening of art and entertainment in tribute to Robert Frank, which will take place on October 21, 2014, at Terminal 5 in New York City.

The post Joel Meyerowitz on The Open Road (video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 27, 2014

Announcing The Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2014 Short List

Todd Hido, photographer and photobook maker greeted an eager crowd at the New York Art Book Fair on Friday, September 26 to announce the thirty-five outstanding photobooks short listed for the 2014 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, supported by Amana / IMA Magazine.

Initiated in November 2011, by Aperture Foundation and Paris Photo, the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards celebrate the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography, with two major categories: First PhotoBook and PhotoBook of the Year. This year, the Awards introduced a brand-new third category, Photography Catalogue of the Year. In 2013, First PhotoBook was awarded to KARMA by Óscar Monzón (RVB Books/Dalpine), and PhotoBook of the Year went to A01 [COD.19.1.1.43] — A27 [S | COD.23] by Rosângela Rennó.

This year’s short list selection was made by Julien Frydman, director of Paris Photo; Todd Hido, Lesley A. Martin, publisher of the Aperture book program and of The PhotoBook Review; Mutsuko Ota, editorial director of IMA magazine; and Anne Wilkes Tucker, photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The ten short listed titles for PhotoBook of the Year are:

The Big Book

Photographer: W. Eugene Smith

Publisher: University of Texas Press

Rich and Poor

Photographer: Jim Goldberg

Publisher: Steidl

Disco Night Sept. 11

Photographer: Peter van Agtmael

Publisher: Red Hook Editions

Marrakech

Photographer: Daido Moriyama

Publisher: SUPER LABO

Photographs for Documents

Photographer(s): Vytautas V. Stanionis

Publisher: Kaunas Photography Gallery

Ponte City

Photographers: Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse

Publisher: Steidl

Vertigo

Photographer(s): Daisuke Yokota

Publisher: Newfave

Imaginary Club

Photographer(s): Oliver Sieber

Publisher: Editions GwinZegal/BöhmKobayashi

The Winners

Photographer(s): Rafal Milach

Publisher: GOST

The Arrangement

Photographer(s): Ruth van Beek

Publisher: RVB Books

The twenty short listed titles for First Photobook are:

everything will be ok

Photographer: Alberto Lizaralde

Publisher: Self-published

Synonym Study

Photographer: Nico Krijno

Publisher: Self-published

The Meteorite Hunter

Photographer: Alexandra Lethbridge

Publisher: Self-published

Father Figure: Exploring Alternative Notions of Black Fatherhood

Photographer: Zun Lee

Publisher: Ceiba

19.06_26.08.1945

Photographer: Andrea Botto

Publisher: Danilo Montanari

Miklós Klaus Rózsa

Photographer: Christof Nüssli and Christoph Oeschger

Publisher: Cpress/Spectorbooks

ED IT: The Substantial System for Photographic Archive Maintenance

Authors: Ola Lanko, Brigiet van den Berg, Nikki Brörmann, Simone Engelen, Sterre Sprengers Publisher: Self-published

Back to the Future

Photographer: Irina Werning

Publisher: Self-published

Inventio

Photographer(s): Yann Haeberlin

Publisher: Self-published

Euromaidan

Photographer(s): Vladyslav Krasnoshchok and Sergiy Lebedynskyy

Publisher: Riot Books

Silent Histories

Photographer: Kazuma Obara

Publisher: Self-published

Hidden Islam

Photographer: Nicoló Degiorgis

Publisher: Rorhof

Sequester

Photographer: Awoiska van der Molen

Publisher: Fw: Books

The American Series

Photographer: Oskar Schmidt

Publisher: Distanz

Fractal State of Being

Photographer: Sara Skorgan Teigen

Publisher: Journal

Spasibo

Photographer: Davide Monteleone

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag

Red String

Photographer: Yoshikatsu Fujii

Publisher: Self-published

War Porn

Photographer: Christoph Bangert

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag

Jannis

Photographer: Alma Cecilia Suarez

Publisher: Self-published

Photograph

Photographer: Yuji Hamada

Publisher: Lemon Books

The five short listed titles for Photography Catalogue of the Year are:

Photobooks: Spain 1905–1977

Photographers: Multiple

Publisher: Editorial RM

Christopher Williams: Printed in Germany

Photographer: Christopher Williams

Publisher: Walther König/David Zwirner

Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness

Photographer: Christopher Williams

Publisher: Art Institute of Chicago

Dark Knees

Photographer: Mark Cohen

Publisher: Le Bal/Éditions Xavier Barral

Tsunami, Photographs, and Then: Lost and Found Project

Photographer: Munemasa Takahashi

Publisher: AKAAKA

The Catalogue Box

Photographers: Multiple

Publisher: Verlag Kettler/The PhotoBook Museum

The thirty-five selected photobooks will be exhibited at Paris Photo in the Publishers Space. After Paris Photo, the exhibition will travel to Aperture Gallery in New York from December 13, 2014–January 29, 2015 and will tour after to the IMA Concept store and gallery in Tokyo from December 9, 2014–January 18, 2015, as well as other venues to be determined.

They short listed books will also be profiled in issue 007 of The Photobook Review, Aperture’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook, to be released in November 2014 at Paris Photo. Copies will be also be available at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore, as well as distributed with Aperture magazine and through other distribution partners.

The short list is also available at Aperture Foundation’s web site at www.aperture.org/photobookawards/ and Paris Photo’s web site at www.parisphoto.com.

A final jury in Paris will select the winners for all three prizes, which will be revealed at Paris Photo on November 14, 2013. The winner of First PhotoBook will be awarded $10,000.

The post Announcing The Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation

PhotoBook Awards 2014 Short List appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 25, 2014

Revisiting the Sequence: Minor White at the Getty Center

Diana C. Stoll in conversation with Paul Martineau, curator of Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit at the J. Paul Getty Center, Los Angeles

Minor White, Self-Portrait (West Bloomfield, New York), 1957. © Trustees of Princeton University

Aperture magazine was founded in 1952 by a group of luminaries that included Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. But the figure who truly breathed life into the new journal was photographer, teacher, critic, poet, and spiritual thinker Minor White. As the editor of Aperture during its first twenty-three years, White established the magazine’s identity as a crucial forum for contemporary art photography. His decisive influence was also disseminated through classes and workshops, and of course through his own work in photography—a medium he saw as nothing less than a vehicle toward transcendence.

Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, the first museum exhibition of White’s work to be presented in a quarter of a century, is on view at the J. Paul Getty Center in Los Angeles through October 19. I recently spoke with Paul Martineau, the show’s curator and the author of its accompanying catalog, about White’s work and its reception, and the thinking behind the exhibition. —Diana C. Stoll

Diana C. Stoll: Minor White is a perennially interesting and complicated subject. How did you come to take this on as a project?

Paul Martineau: I have liked Minor White’s work for a long time—and although the Getty has an outstanding holding of modernist photography, I was surprised to learn that there were only three prints by Minor in the collection. I had the idea to do a show with the hope of obtaining more of his work for the museum. We were very fortunate to have the support of Los Angeles–based philanthropists Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, who helped us to acquire the sequence Sound of One Hand and have promised to donate a significant number of photographs by White to the Getty Museum. In three years, when all the gifts have come in, we’ll have seventy-five!

Also, it had been twenty-five years since Minor’s last major exhibition [Minor White: The Eye That Shapes, organized by Peter C. Bunnell, opened in 1989 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and traveled to Portland, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Rochester, Boston, and Princeton]. I realized it was time.

DCS: Let’s talk about that twenty-five year gap. The subtitle of your show is Manifestations of the Spirit. The idea of Spirit was central to Minor’s work—but do you think it might be one of the reasons why he’s not been focused on in all these years?

PM: Yes. When I was planning this exhibition, I looked into all the past exhibitions and books on Minor—and I thought about how difficult it seemed to come to an understanding of what Minor was all about. I realized that what was needed at this time was a project that made Minor’s life and work more accessible.

DCS: Certainly the public’s understanding of homosexuality has changed, too—since the 1989 exhibition, and even more since Minor’s own lifetime. Does this give us a new way to talk about his approach?

PM: It’s key to understanding what he’s about. Imagine trying to understand Alfred Stieglitz without his photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe, or Edward Weston without his photographs of Tina Modotti or Charis Wilson.

DCS: But as heterosexuals, Stieglitz and Weston didn’t face the quite same thing in their work. In his 2008 essay “Cruising and Transcendence in the Photographs of Minor White,” critic Kevin Moore talks about the idea of sexual frustration being central to the meaning of Minor’s work. For Stieglitz and Weston—and many others, of course—sexuality was important, but I don’t think they felt thwarted in finding the means to express it.

But I wonder if someday Minor’s angst will seem almost historical to us—like the fury of pre-civil-rights artists in the United States . . . we can understand where their anger and frustration were coming from, but it feels distant. Will Minor’s frustration—if that word applies—seem foreign to people as generations go by, and as sexual variations are taken for granted?

PM: Right. I learned recently that Facebook now has fifty-one different gender designations to choose from—and the British branch of Facebook added fourteen more! It shows you how far things have come.

One of the clues to how Minor thought about homosexuality is in a letter that he wrote to photographer Edmund Teske. [In 1962, Teske sent White some two hundred photographs in the hopes that he would make a selection from them for publication in Aperture. Teske’s sexual interest in men was clear to White, who responded with a very emotional letter saying that Teske needed to “universalize” his imagery, so that his feelings wouldn’t be so obvious and the work would have a broad appeal.]

Minor White, Rochester, New York, 1963. Courtesy of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

DCS: When I was working as an editor at Aperture magazine, many decades later, that was still the central question: how does the work communicate to the reader? The magazine has to function as a mediator between the artist and the public—and it was Minor who set up that dynamic for Aperture. How does an artist take this intensely personal thing and universalize it so that people will get it on the other end? As an editor, Minor understood: the magazine brings it to the reader, and the reader in turn has to be able to take it and go with it.

I’ve had the opportunity to talk to Peter Bunnell about Aperture’s early years, and how Minor fell into the job of being the editor. But boy, he took to it like a fish to water!

PM: Yes. And Aperture became a sort of a Bible for insiders. But by the time the ’70s rolled around there was some reaction against Minor and his powerful influence. People were becoming interested in new things, photographically and otherwise—such as New Topographics.

DCS: And of course sociologically, the world was changing, too. All that very important and influential stuff that Minor was disseminating with his workshops—the mystical, the esoteric, the spiritual. . . .

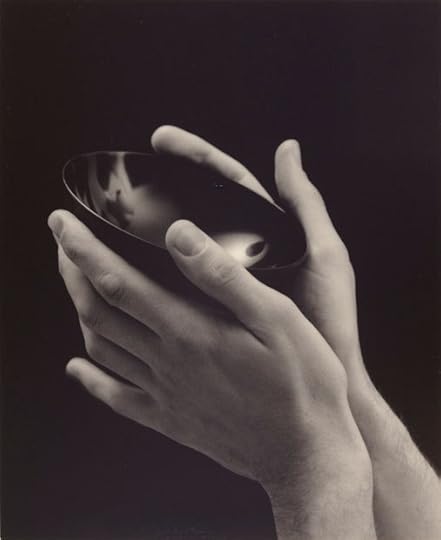

Minor White, The Sound of One Hand Clapping, Pultneyville, New York, 1957. Courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

PM: It was part of that period, and then it subsided.

DCS: In a similar way, Minor was wonderfully presumptuous in what he expected of viewers—both for his own work and for other people’s photography—he demanded a kind of “heightened awareness.” He wanted you to bring your full self to the process of looking. One wonders how well later generations will be able to do that. Will they do it at all?

PM: Today, of course, we’re constantly bombarded with images—on the sides of buses, on our cell phones. This show, however, calls on people to slow down and study the pictures. To spend time with them.

DCS: One of White’s great contributions to photography was the idea of sequence: a body of images that is somehow greater than the sum of its parts—he used the term “cinema of stills.” But in the 1989 show, Bunnell did not include any sequences at all, because (as he says in a footnote in the exhibition catalog): “In a public gallery, crowded with people, the necessary state of concentration cannot be achieved by a viewer to properly engage the works as White intended.”

PM: I think that might make sense for someone who has devoted a life to the study of photography . . . which is different from the average museum-goer. I think it’s a disservice to Minor and to the viewer not to include any sequences because of the fear that people might approach it in the wrong way.

Installation view of Minor White’s series Sound of One Hand. Courtesy Getty Center

DCS: How are you presenting Minor’s sequences in this show?

PM: The only sequence that I have in its entirety, in the original order, is Sound of One Hand (sequenced in 1965). Ten of the photographs are hung closely together on one wall with the eleventh nearby in a floor case. I placed a text explaining what a sequence is, and how Minor would want you to approach reading it, on the adjacent wall. So visitors are able to experience it the way Minor intended, if they want to. Some people won’t read it and maybe they’ll go backwards, but that’s up to them.

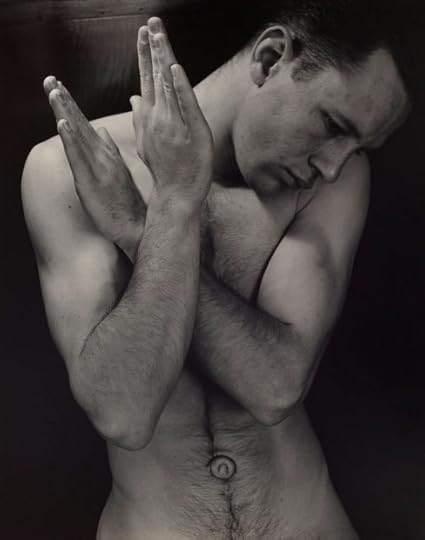

DCS: In the exhibition catalog, you show The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors [thirty-two images centered on White’s student and model Tom Murphy, sequenced in 1948] in its entirety. I believe there are only two copies of that sequence, right? Minor had one, and Tom Murphy had the other.

PM: Yes, both copies are now in the Minor White Archive, thanks to Peter Bunnell’s efforts. Hardly anyone knew about this album before we published it.

DCS: What kind of light do you think this sequence sheds on his work?

PM: It’s a wonderful pilgrimage of sorts through Minor’s various mental and emotional states, from anguish to ecstasy. The alternating rhythms of stillness and movement feel like a kind of a dance, as you page through the album.

DCS: Clearly Minor considered this a private project—but there is certainly meaning to be drawn from it. It’s an interesting balance: how understanding Minor affects the understanding of his work, versus being able, as a viewer, to pull from yourself and relate to his images.

PM: It’s the two-way street; you benefit by being able to travel both ways. If you know more about Minor, certain things come to the fore that you would probably not have realized on your own. But you can still appreciate and enjoy the power of the work without any knowledge of what Minor was about.

DCS: Minor’s body of work—as well as his work with Aperture, and as a teacher—was very much about challenging the viewer to rise to the occasion of looking: to bring your all to the experience.

PM: That was one of his lifelong challenges: he wanted people to study the work and bring their own associations to the viewing of it. I think a big clue to Minor’s approach is the title of Sound of One Hand—from the Zen koan that asks “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” Everyone is going to come up with a different answer.

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, from the series The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, 1948 © Trustees of Princeton University

DCS: And what about the title The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors?

PM: It refers to Anthony the Great, the mystic who helped spread the concept of monasticism and lived as hermit. When he was alone in the desert, he was continuously tempted by the Devil. And Minor believed that every portrait he took was a self-portrait—a mirror image of his desires and fears. . . . I think in all his pictures, there are these two issues: he presents himself as someone who has desires for men, but doesn’t act on them—and channels that energy into something of great beauty and power. He didn’t always live up to his ideals, but he tried to.

DCS: Minor said at one point: “A love of God can grow out of a love for the flesh.”

PM: Yes. Minor was hard on himself. That is part of the struggle that you can feel in some of his work.

DCS: It’s interesting how some photographers can benefit from their challenges. All these things nourished Minor’s work.

PM: For me, Minor’s best work was made from 1958 to 1963—that really represents the apex of his career, when I feel he was applying all the things he was learning from his study of Eastern religions to the work, and doing things that no one else was doing. Although he had been teaching for many years already, this was also when he was really starting his workshops. He liked the workshop format because it enabled him to be more experimental. He didn’t have to answer to anyone. He even studied hypnotism and used it in some of his workshops in the 1960s. That might not have gone over so well in an academic setting!

The photographer John Upton, who studied with Minor, told me that he used Minor’s relaxation techniques in an experiment that he did with two groups of students. He had them all read photographs, and the group that had completed the exercises came up with much more profound insights and reactions to the photographs.

DCS: And what else about Minor’s legacy? What things have come down to us from him, in terms of both photography and teaching photography?

PM: At the outset, I thought it would be interesting to create a kind of genealogical tree that would show Minor and his students, and their students. Then I realized that such a project would take years to develop! Minors students are legion—Minor’s army! There are so many people who studied with him and then, in turn, taught other people

DCS: Are there photographers today who had no contact with Minor but have been obviously touched by him?

PM: Abelardo Morell comes to mind. I don’t think he knew Minor, but he has definitely been influenced by his writing and ideas. I remember him quoting Minor at one point, about metaphorical photographs.

DCS: Minor said: “To look at things to see what else they are.” It’s about photographing and understanding meaning on at least three levels, and probably more. He took Stieglitz’s idea of equivalency all the way to the end-point.

PM: Right. There’s nothing else to be uncovered in that theory while remaining connected to reality.

And Paul Caponigro, who was a student of Minor’s, said something I think is very important: that Minor White showed everyone, in word and deed, what it is to live a life completely dedicated to photography.

Minor White, 72 N. Union Street, Rochester, 1960. Courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

_____

Paul Martineau is associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in Asheville, North Carolina. She was the senior editor of Aperture magazine from 2000 to 2013, and co-edited Peter C. Bunnell’s 2012 book Aperture Magazine Anthology—The Minor White Years, 1952–1976.

The post Revisiting the Sequence:

Minor White at the Getty Center appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 24, 2014

Protected: This is another post for Portfolio Prize

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: This is another post for Portfolio Prize appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Call For Entries for the 2015 Portfolio Prize is Now Open!

The entry period for the 2015 Aperture Portfolio Prize opened on Wednesday, October 1, 2014. To be eligible, entries must be received by Tuesday, December 2, 2014, at 12:00 noon EST.

The post The Call For Entries for the 2015 Portfolio Prize is Now Open! appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Protected: This is a test post for Portfolio Prize new templates

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: This is a test post for Portfolio Prize new templates appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 23, 2014

Recap: The New York Times Magazine Photographs Opening Reception

On Wednesday, September 17, Aperture Members and friends were the first to view The New York Times Magazine Photographs exhibition at Aperture Gallery. Guests were joined by the show’s curators, Kathy Ryan, director of photography at the New York Times Magazine, and Lesley A. Martin, publisher of Aperture’s books program, for a tour of the exhibition.

The exhibition has been traveling internationally for over two years and is on view at Aperture Gallery through November 1, 2014. The accompanying publication, The New York Times Magazine Photographs, was published by Aperture in 2011.

Images © Max Campbell and Katie Booth.

The post Recap: The New York Times Magazine Photographs Opening Reception appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers