Aperture's Blog, page 170

November 20, 2014

The Islamic State and Photography

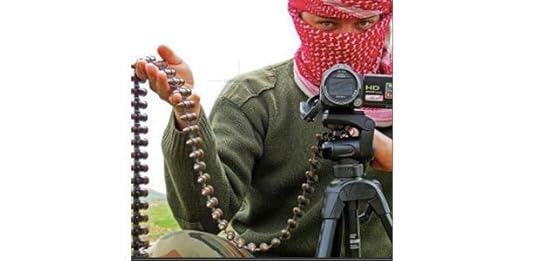

Image of Unknown IS fighter from Twitter. Location Unknown. July, 2014.

Sam Powers is a social media analyst who has spent time working in private intelligence, focusing on the threat posed by foreign terrorist organizations. For the past year, he has been monitoring the growing threat posed by The Islamic State (IS), tracking the group’s media strategy and outreach to Western audiences on social media. Before his career in intelligence and social media, Powers was a documentary filmmaker . Here, he considers the strategies and visual imagery of IS from a photographic standpoint.

As The Islamic State attempts to recruit new members, their use of photography and imagery has arguably become more advanced than any other terrorist group in history. The group’s most deliberate imagery, made with high-quality cameras and using editing techniques similar to major Western media outlets, has come under scrutiny by news agencies as well as the intelligence community for its ability to capture both jarring battle footage and the group’s quotidian activities. In fact, IS has created an entire industry comprised of private groups, staffed by journalists and former government employees, all of whom are dedicated to sifting through IS media releases and analyzing the message and effect on a predominantly Western audience.

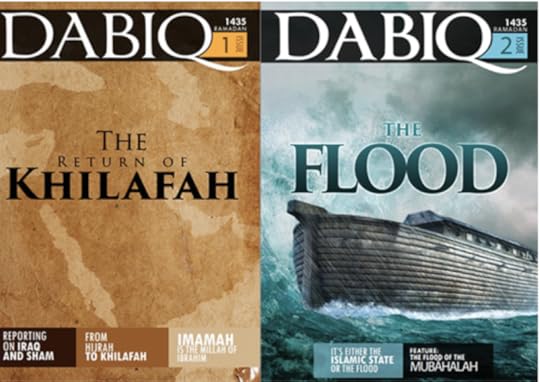

IS runs various media offices, with its largest known as Al-Hayat (meaning life in Arabic). This outlet releases a slick, online multilingual magazine called Dabiq, named after a religiously significant Syrian town. Within the pages of this magazine and through official media handles on Twitter, IS presents its carefully choreographed vision to a global audience. As their reports attempt to mimic the production values of Western media outlets, IS sympathizers on Twitter grow at an alarming rate. Currently there are tens of thousands of Twitter users who either claim that they are fighting with IS or are sympathetic to the group’s mission.

Two recent covers of Dabiq magazine, the IS online periodical. September, 2014.

The images that follow are sourced from these various media platforms as well as from IS supporters on Twitter. Many are screenshots from videos distributed by IS on hosting websites including JustPaste.it, a Polish website used for sharing large files. While the authenticity of these images cannot be independently verified, the mass dissemination of the photos in this article as well as their endorsement by known jihadist ideologues and media officials suggest that the images are genuine. The pictures are of high quality and capture everything from battle footage to IS efforts to maintain support amongst their constituency in Iraq and Syria.

Image from Black War Training Camp, unknown location in Syria. September, 2014.

A battle photo taken from a Dabiq magazine release. Location Unknown. September 2014.

Photo of IS stronghold Ar Raqqah, Syria, using long exposure. October 2014.

Much IS imagery captures the mundane, often with the clear intention of attracting a Western audience. From rides in the back of tanks to images of local cuisine alongside Coca Cola or other comfort foods, these pictures show IS’s attempt to present jihad with a human face. Such images of daily life are usually of lower quality, clearly taken with devices like smart phones by fighters on the ground. They offer a distinctly different aesthetic when compared with the more sophisticated images taken with higher-quality DSLR cameras that appear in IS propaganda magazines.

A foreign fighter enjoying a kebab at a post-battle celebration in Iraq. September 2014.

IS fighter handing out candy during Eid Al-Fitr celebrations in Nineveh province, Iraq. July, 2014.

Another prominent category of imagery surfacing on Twitter is personal images that evoke allegiance to IS and demonstrate a pledge of faith (Bayah in Arabic). These are often the first images displayed by a Twitter user once he becomes a member of IS. Established members often re-tweet images of new members pledging faith by holding up their index finger, an allusion to the tawhid, or the oneness of god. Unaware of what they are being asked to swear allegiance to, children of fighters are often pictured in the same position, sometimes brandishing automatic weapons.

A child pledging allegiance to IS. Location Unknown. August, 2014.

Alongside pledges of faith, the use of images of dead brothers in arms, referred to by IS as “martyrs,” have become increasingly popular since the US-led coalition targeting the group began. These images are often placed alongside a fighter’s personal profile on Twitter to commemorate the dead and to encourage continued fighting against the West.

Image from a propaganda page of a dead suicide bomber and his explosive laden truck. Iraq. October, 2014.

With carefully crafted magazines displaying how and why to join the jihad and video using advanced film techniques, IS has reached a large global audience. While the United States and other countries have attempted to counter the group’s vast media output, such efforts have not degraded IS’s ability to tap into the heart of a minority of susceptible young Muslims, from the West in particular, who are increasingly attempting to travel to Iraq and Syria to join the militant group. Some have argued that government alone cannot be the sole voice online against IS, particularly when dealing with sensitive topics of Islamic faith.

Efforts including the State Department’s Digital Outreach team (found on Twitter under the handle @DSDOTAR) lack IS’s propagandist’s production values and wide reach. For example, when compared to the tens of thousands of followers maintained by IS’s most well known sympathizers, referred to by some in the intelligence community as “power users,” @DSDOTAR maintains just over one thousand followers, many of whom appear to be IS fighters and sympathizers themselves who trail the handle, most likely to gain information on US government practices online.

Image from @ThinkAgain_DOS Twitter Page. October, 2014.

While other initiatives, including the State Department’s (DOS) “Think Again Turn Away” (found on Twitter at @ThinkAgain_DOS), maintain a large following and emphasize that IS is a brutal, anti-Muslim organization, the government has been criticized for its use of imagery on social media. The image produced below highlights how DOS is attempting to apply a moral argument to delegitimize IS, while using jarring imagery to back up their statement. Some have argued that a US-sanctioned Twitter page, producing anti-IS imagery, merely serves as a beacon of attack for IS fighters themselves. As seen in the image below, IS fighters and sympathizers often use these government handles to make anti-US remarks and attempt to justify violence. With this in mind, it seems that those who want to counter IS’s sophisticated use of media and imaging to garner a following will need to create an equally seductive alternative narrative and take the fight to IS online.

Image from @ThinkAgain_DOS Twitter page with a comment from an IS sympathizer.

The post The Islamic State and Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 19, 2014

Events Ashore: An-My Lê Artist Talk (Video)

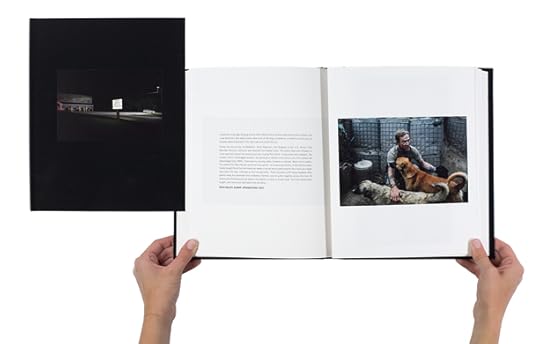

On November 4, 2014, we joined artist An-My Lê for a talk and book signing of her highly anticipated second book, Events Ashore. In this body of work, Lê continues her exploration of the American military, a pursuit both personal and civic. Events Ashore began when Lê was invited to photograph U.S. naval ships preparing for deployment to Iraq, her first in a series of visits to battleships, humanitarian missions in Africa and Asia, training exercises, and scientific missions in the Arctic and Antarctic. Lê took attendees through Events Ashore from beginning to end, explaining the intentions behind the individual images as well as the book’s design.

Events Ashore

Events Ashore $89.95

Add to Cart

The post Events Ashore: An-My Lê Artist Talk (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 18, 2014

The Living Library Markus Schaden on the Opening of the PhotoBook Museum

On August 19, 2014, the PhotoBook Museum, Cologne, opened the doors to its temporary Carlswerk space, a former industrial site now filled with containers full of photobooks; a smorgasbord of exhibitions of individual “PhotoBook Studies”; a book research lab run by Dortmund University; workshop areas; and even an almost-to-scale replica of Café Lehmitz, made famous (or infamous) by Anders Petersen’s book of the same name. (This first version of the Museum closed October 12, but it is looking for a more permanent home.) Markus Schaden, photobook evangelist and museum founder, reports back on the opening events, his inspiration, and its future.

There were approximately five thousand visitors to the PhotoBook Museum in the first week—a lot of photobook and photography fans, but also local people interested in an exciting event and people who have nothing to do with photobooks, which, for me, is the most exciting.

My experience with photobooks comes out of the book trade, as a bookseller and buyer. I missed being in touch with the average reader, not just someone already immersed in the field. Every photographer wants to make a book, so they are interested, and then you have the collectors, the freaks, the nerds; they love to have a book all signed, editioned, etc. But I think we need readers outside of these niches to make the market healthier. As Wolfgang Tillmans said a few weeks ago in the Guardian, pictures are replacing words, for young kids especially. We have to take care to educate, to show kids and others the possibilities of good visual culture in book form. I think we have to develop this kind of visual literacy—not just fetishize the book by discussing paper, special bindings, whatever.

A good example of this can be found in one of the PhotoBook History sections of the museum: Chargesheimer: Köln 5 Uhr 30. A Book-History Reconstructed: Photokina 1970, in which a 1970 exhibition is reconstructed. This exhibition—and the book it accompanies—presents the photographer’s manifesto and statement about Cologne, and the changes the city landscape was undergoing at the time. Using this work, I want to have a discussion with people from the city about traffic patterns, post-war architecture, and living in Cologne today. If a book can really get into life and change it, or at least change your view of the world, that is the best a photobook can do. For sure, everyone has to take care to think about the form, the production. But this is not the real item. The real item is the story, the message. For me, a book is an idea in a physical form.

Another of my goals was to explore a new relationship between a collector, a collection, and a museum. As I was planning, one of my questions was: do I need to buy a collection? Maybe not; maybe it would be nice to partner with others who are already building specialized collections. They could continue to collect, and we could make an agreement for how best to use those collections. For example, Hilla Becher has an amazing library that she and Bernd created. The great thing is that it’s not just about photography, it’s about their research: books about steel and about the German construction industry and architecture. I think this is the real library for Becher studies! Or, for example, one of the first collections of Japanese books I ever saw, in 1999, was in the bathroom of the Kodoji Bar in Tokyo, where Araki famously hung out. In this tiny bathroom of this tiny bar were all these masterpieces of Japanese photography. The bathroom also had pens on hand, and the books were all inscribed by other photographers—Tomatsu writing something to Moriyama, for example! I thought to myself, wow, this is the perfect research library.

In the long run, we want to find a permanent residence for the museum. I would love to be here in Cologne, but it is not absolutely necessary. I know how difficult it is to set up a museum in terms of money, of funding, and finding a building especially, so my whole strategy was to turn the planning steps around to start with what is basically a dummy version of the museum. After this site-specific manifestation, we’ll put everything online and make documentation of it available to more people. Then we can go on tour with a shipping container, the cargo version. We can pack up parts into individual shipping containers; it can travel to festivals, other museums, fairs, wherever. Maybe other people will take over the idea. The dream is that in ten years, we might have three or four PhotoBook Museums around the world. Even if I can’t do it, and other people take over the idea, it would be great.

_____

Markus Schaden is the founder of the PhotoBook Museum and the Schaden.com publishing house. He is based in Cologne, Germany. The PhotoBook Museum’s first catalogue is nominated for a 2014 PhotoBook Award. thephotobookmuseum.com

The post The Living Library

Markus Schaden on the Opening of the PhotoBook Museum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Review: Christopher Anderson on Peter Van Agtmael

Peter van Agtmael, Disco Night Sept. 11

This book was short-listed for a 2014 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Award.

Peter van Agtmael

Disco Night Sept. 11

Red Hook Editions

Brooklyn, 2014

Designed by Yolanda Cuomo Design

8 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (21.59 x 26.7 cm)

276 pages, including 19 gatefolds

188 color photographs

Clothbound hardcover with tip-on

I really don’t want to look at another picture from a war. For such a visual subject to photograph, so little seems to come from war photography that means much of anything at all. Some of it is done “better” or “worse”; sometimes there is a more powerful moment here, or better light there. But rarely does any of it add up to something more than a horrific accounting of a daily score. One of the reasons (there were many) I no longer function as a “war photographer” is that I couldn’t find a path to reconciling this for myself. I could not give myself a satisfactory answer to the question, “What is the point?”

It was always so. But now and then (once in a generation?) a body of work comes along that answers this question with thunder and poetry. Vietnam Inc. by Philip Jones Griffiths (1971) comes to mind. Farewell to Bosnia by Gilles Peress (1994) is an obvious example. With his book Disco Night Sept. 11, Peter van Agtmael might have answered that question for his generation of war photographers—and for himself.

Disco Night moves over vast territory, both geographic and emotional. Layers are stitched together to equal meaning that is bigger than the sum of its parts. The images float back and forth from Afghanistan to Iraq to America. We meet soldiers and civilians and families. But van Agtmael’s camera serves not to report their stories as much as communicate his experience among them. As with Tim Hetherington’s video, Diary (2010), van Agtmael deals with the dissonance between war and home and the gray areas in between: one day a firefight in Afghanistan, the next a view from his own childhood window. But the introspection is ambient noise; he is not consumed by it. The central characters are those trying to make sense (or not) of what war has brought them. The striking thing in this book is the humanity with which van Agtmael introduces us to this material. Humor and tragedy are not easily untangled in the real world.

The design and size of the book walk a fine line between understatement and gravitas. It is elegant without being pompous, simple without being shallow. The photography is loose and subtle, so it needs a bit of size to register. Apart from van Agtmael’s poignant introduction and diary-like entries sprinkled in (thank goodness he didn’t add some insufferable academic essay about what war photography is), lengthy captions accompany the images. In a lesser book, this might easily suck out all the poetry, but here it works coherently in the service of its overall power.

I should note that Peter is a friend and colleague of mine at Magnum, so in the spirit of objectivity there has to be some criticism. So, here goes: photography in and of itself is not very interesting to me. Visual wizardry and compositional fireworks are just tricks. With some shining exceptions, the pictures in Disco Night are not what one would describe as “good” in that mundane sense of photography. But because they are not “good” pictures, they are great pictures: pictures full of confusion, frustration, fear, excitement, anger, horror, and sorrow. For me, this is where photography becomes interesting. These are not just pictures about war. They are pictures about us—us as Americans, Afghans, Iraqis; as soldiers, civilians, journalists, innocents, savages. It doesn’t seem trite to call Disco Night Sept. 11 an important book. It will fit perfectly on your shelf somewhere between Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977) and Gilles Peress’s Telex Iran (1983).

_____

Christopher Anderson has been a member of Magnum Photos since 2005. He is the author of five photography monographs, including Capitolio (Editorial RM, 2009), Son (Kehrer, 2013), and Stump (Editorial RM, 2014). Presently he is the first-ever photographer-in-residence at New York magazine.

The post Review: Christopher Anderson on Peter Van Agtmael appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Review: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen on Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse

Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse, Ponte City

This book was short-listed for a 2014 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Award.

Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse

Ponte City

Steidl

Göttingen, Germany, 2014

Designed by Ramon Pez

9 1/2 x 14 5/ 8 in. (24.1 x 37 cm)

192 pages

365 four-color and black-and-white images

Clothbound hardcover in a box, including 17 accompanying booklets with written and visual essays

It is a testament to the purchase of the building known as Ponte City on the collective imagination of Johannesburgers that, within minutes of my opening Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse’s book of that name in a coffee shop hardly four miles from the place, several people stop to tell me something about the Ponte they know: a city councillor whose German father lived there in the early ’80s when he came to South Africa on a work assignment; a lyric soprano who sang a lullaby in the round building’s famous hollow core; an architect just returned from a Europe trip with a trove of city books, several of which mention Ponte; and an artist who conducted a “suicide project” in the tower—a video camera parachuted down into the core, recording as it went.

I have my own flickering recollection of a visit to a Ponte apartment in Johannesburg’s “bad” late ’80s. On such visits one saw quickly that it was, then, a space where more than one kind of transgression was possible: the apartment was shared by one black and one white tenant, defying multiple apartheid-era proscriptions, and, at some point in the visit, drugs of various description were consumed. Today, cleaned up, secure, and home to thousands of tenants, many from outside South Africa, its glamour and infamy are ameliorated by the everydayness of life in a residential skyscraper.

What this substantial book demonstrates, both in its visual scope and its bookish, boxy materiality, are the variegated ambitions, associations, and meanings of an apartheid-era residential building that rises fifty-four storeys above Johannesburg’s skyline—a city within a city, like the high-rise in José Saramago’s novel The Cave. Housed in a plain, stapled cardboard box, Ponte City is really eighteen books: a large photobook with a minimalist blue-and-black cloth cover, and, nesting beneath it in a rectangular cavity, seventeen saddle-stitched booklets. These form a kind of visual-textual puzzle: the cover of each is a section of one of the photographs in the bigger book, and each reflects on or interprets Ponte differently.

If you follow the editorial signposts, you’ll flip through the photobook, and as you get to the pages with the “missing pieces,” reach for the right booklet and read downward into the subterranean layers beneath Ponte, or upward through its hollow core. You’ll gaze voyeuristically into the apartments, or rifle through press clippings, tracing Ponte’s history from its construction in 1975, to its middle-class hipsterism, to its status as urban eyesore, to the post-apartheid ambitions developers had for it. Reading in this way is like tunneling into Ponte’s past and discovering that the first vision for the building, as a home for upwardly mobile young urbanites, lies buried under the various layers of its complex history. But you’ll also read “smaller” histories—gleaned from the ephemera gathered by the photographers from vacated apartments into a bitty, pop archive—about migration, bureaucracy, Johannesburg’s transformations, hope and failure and the banal texture of daily life. These are presented textually and visually as quasi-fictions, fictions, and documentary fragments, lying between the full-bleed images—some by the photographers, some found—in the photobook.

This book looks at a single and singular building from multiple perspectives, at once a filmic, literary, and photographic account of Ponte, fixated both on the individual lives lived here and the heady panoramas of the hectic city from which it ascends. Ephemera serve as counterpoint to the “big gaze” of Subotzky and Waterhouse’s meticulously composed images. But so do their collages of doors, windows, televisions. In these they zoom in and away—from kitchen counter to cityscape—in dizzying maneuvers that point to the relationship of metropole to individual life, of history to intimacy. Ponte City plays out partly as a postmodern archeological dig, recalling the work of other documentarians but also contemplating the inevitable fragmentation of lives and the concomitant inventiveness that are the photographer’s challenge and pleasure.

_____

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen is a writer, senior lecturer, and head of creative writing at Wits University, Johannesburg; cofounder and editor of Fourthwall Books; and former editor of Art South Africa magazine. fourthwallbooks.com

The post Review: Bronwyn Law-Viljoen on Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

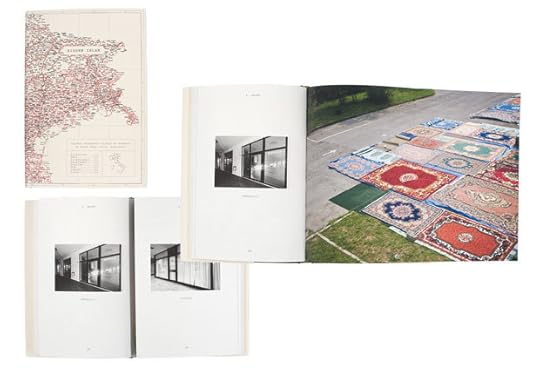

Review: Daniele De Luigi on Nicoló Degiorgis

Nicoló Degiorgis, Hidden Islam

This book was the winner of the First PhotoBook Award in the 2014 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

Nicoló Degiorgis

Hidden Islam

Rorhof

Bolzano Bozen, Italy, 2014

Designed by Nicoló Degiorgis and Walter Hutton

6 1/4 x 9 1/2 in. (16 x 24 cm)

90 pages, including 45 gatefolds

42 color photographs and 82 black-and-white photographs

Hardcover

“Silent invasion” is a phrase that Italian right-wing populist parties and media frequently use to oppose the rise of new Islamic places of worship across the country. The clear aim is to generate panic about Muslims “colonizing” Italy. It is true that places in the country where Muslims can practice their faith are often invisible to others—but this is because requests to build official mosques are so frequently denied by local governments. Beyond special regulations for Catholicism, there are no clear and complete national laws on the construction of places of worship, leaving other religious groups vulnerable to bias. Moreover, every time there is an announcement that a new mosque may be built, groups of local citizens shout that it will be a den of terrorists and barbarians. As a result, you can literally count the number of official Italian mosques on two hands, and an estimated 1.5 million Muslims are forced to gather in hundreds of makeshift places of worship.

Hidden Islam by Nicoló Degiorgis, winner of the 2014 Rencontres d’Arles Prix du Livre d’Auteur, uses a clever layout device to illustrate this situation. The photographer’s research focuses on northeastern Italy, a large area where Islamophobia has spread. Degiorgis carried out an extremely accurate mapping of unofficial places of worship and decided to represent them using a dual approach in style. He shot the exteriors of buildings using the rules of nineteenth-century documentary aesthetics: black and white, diffused daylight, visual clarity, no people, anonymity. The point of view is always diagonal, facing a corner of the building, or frontal, for the apartment buildings featured. The sequence is made up of images of similar buildings, to increase the impression that there’s nothing to see. All the photographs are sorted into eight types—such as warehouses, shops, supermarkets—and pinpointed through postal codes. Half of the buildings have been shot inside too, but in color and typically with people in prayer. The documentary approach in these color photos is narrative: Degiorgis allows himself to vary the point of view and the moment of shooting, with great attention to detail depending on the scene.

The peculiarity of the book is how the photographic material has been organized. Every page in the book is made up of a gatefold: on the outside of the flaps are pictures of the exteriors, while inside the gatefolds are the interiors. The combined use of two photographic codes that are usually seen in opposition—a choice that could be seen as risky—works surprisingly well; the gatefold structure doesn’t read as an obvious play on inside vs. outside.

This book does not only shed light on the condition of Italian Muslims or of Muslims living in Italy. As it’s up to the reader to either keep the pages folded, only looking at the surfaces of the urban landscape, or open them to cast a glance inside, it also works as a metaphor for the attitudes one can adopt in the face of this phenomenon. This is key to understanding religious tensions in contemporary Italy, a land that is both the cradle of Catholicism and a prime destination for many Muslim immigrants, many of whom arrive from countries just across the Mediterranean. Ironically, Hidden Islam could even be a useful tool for the supporters of the “silent invasion” theory. Thus, the book is also a reflection of the instability of photographic meaning and the limits of the medium. As Lewis Baltz suggested, to see is not the same as to know.

_____

Daniele De Luigi was recently appointed curator of the Galleria Civica di Modena Italy, and is a regular contributor to the European Photography Festival in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

The post Review: Daniele De Luigi on Nicoló Degiorgis appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Publisher Profile: Natasha Christia on La Kursala

The exhibition La Decencia, with photographs by Davíd León Rodríguez, at La Kursala in September.

La Kursala, an exhibition room dedicated to emerging Spanish photographers and patron for independent publishing under the imprint Los Cuadernos de la Kursala, has been one of the most influential exponents of the recent boom in Spanish photobooks. Initiated in 2007 by the University of Cádiz and assigned since its beginning to photographer, professor, and curator Jesús Micó, the project has remained committed to its core goal of bringing international attention to the periphery of Spanish photographic creation.

The backlist of Los Cuadernos de la Kursala, a collection of photobooks copublished with emerging photographers and small independent editors from around Spain, reads as a heterogeneous cartography of contemporary Spanish photobooks: the forty-three released so far include La caza del lobo congelado by Ricardo Cases (2009), The Afronauts by Cristina de Middel (2012), and Ostalgia by Simona Rota (2013). La Kursala, using a standard low-scale budget, works less as a publisher than as a collaborative, unpaid editor, whose main task is to spread the word about its editorial selection by sending out its whole five-hundred-copy print run to a mailing list of influential photography people in Spain and abroad. In this sense, Los Cuadernos books are messengers: not only have they drawn attention to the curatorial discourse of a small hall in Cádiz, but they have also conferred visibility upon a new generation of photographers and photobook makers residing in Spain who would have otherwise lacked any sort of institutional platform.

Jesús Micó is a Cádiz local permanently based in Barcelona, 900 kilometers away from the small seaside town, which is situated at the extreme southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. He was given carte blanche for La Kursala’s conceptualization and development, and to him, a self-described “expert in projects of the periphery,” it represented a stimulating challenge: was it possible to turn a minor provincial exhibition hall into a reference point in contemporary creation, and, if yes, how? In Micó’s mind, La Kursala should make up for its peripheral position with a fresh and competitive program, omitting consecrated photographers in favor of novel young names. Secondly, it should maintain this program within the margins of an affordable budget, yet not at quality’s expense. Thirdly, and most important, it was necessary to develop a promotional strategy which would allow its work to transcend local frontiers and reach the nucleus of contemporary Spanish photography.

When the University of Cádiz offered a standard budget of 2,900 euros for every La Kursala project, Micó suggested that most of this money be allocated to the publication that accompanied the exhibition rather than to the exhibition itself: book production would be financed with 2,000 euros, while only 900 would be allotted to the exhibition. At the time, photographers, sellers, and institutions in Spain were primarily oriented toward exhibitions, but La Kursala placed photobooks, with their infinite narrative layers, at the core of its project.

In 2008, the year after La Kursala’s founding, the financial crisis blasted away the Spanish market and any illusion of welfare guaranteed until then by the flow of public funds. An emerging generation of photographers found themselves on the crossroad of two eras: before and after the crisis. In 2007, their works were largely absent from gallery walls, museum collections, fairs, or auctions; they were too young, the establishment too conservative. After 2008, they were at least, in comparison to older generations, better prepared to start all over again and deal with irreversible changes to the rules. “Websites, blogs, screenings, and, of course, electronic or printed photobooks became their media of expression,” Micó explains. La Kursala arrived at the right moment. By acknowledging the autonomy of the artist as self-curator and producer, Micó says it provided, for the first time, an institutionalized frame of support for this “self-sustained generation, whose way of understanding photography was closely related to the concept of the photobook—a generation conceiving their works mainly to be made in this format.”

As a result, the books published independently under Los Cuadernos de la Kursala work more like singular artistic statements than like the traditional exhibition catalogues produced by other Spanish publishers. Variety in format, content, and aesthetic denotes Micó’s fundamental curatorial premise: absolute creative freedom for participants and full respect for their work. Attuned to this spirit, La Kursala provides everyone with the same modest budget regardless of their name, trajectory, or status, and, apart from Micó’s discrete coordination and curatorial advice, the University of Cádiz does not interfere in any way with editorial or production. This is a far cry from more traditional Spanish publishers who are less keen on risks and rarities.

As a flexible publishing platform that has provided essential support to many people and projects, La Kursala acknowledges the ideas of self-publishing and the synergy of various agents when putting a project through. Crowdfunding, private sponsors, and small independent publishers are all welcome. Although 2,000 euros is the minimal, elementary budget for each book-publishing project, this has nonetheless kickstarted books such as The Afronauts (a book that was obviously not made with 2,000 euros) and initiatives such as Fiesta Ediciones, Ricardo Cases’s own publishing venture. Furtivos by Vicente Paredes (2012) and Ukraina Pasport by Federico Clavarino (2011) were Fiesta’s first projects exhibited at and copublished with La Kursala, while, for Juan Diego Valera and Aleix Plademunt, the release of their respective Kursala books Coma (2011) and Espectadores (2007) prepared them to launch Ca l’Isidret, their own publishing house.

Micó repeatedly stresses the paramount role of regular mail as a promotional channel for La Kursala. Each Los Cuadernos volume is dispatched to journalists, curators, booksellers, professors, collectors, and others in the Spanish photo world. This affordable DIY distribution strategy—airmail requires a minimal budget—has transcended regional barriers and solidified a visceral circulation network that has spread the word, fueled debate on online social networks about photobook culture, and reinforced the awareness of both collective work in photography and of the photobook community.

Narrating the story of La Kursala is equivalent to sequencing the history of the Spanish photobook of recent years: nearly all significant independent publishers in Spain have collaborated with or originated from it, and some of the best Spanish designers, including N2, Jaime Narváez, and Ramon Pezzarini, to mention but a few, have been involved in its projects. Over the last years its volumes have been finalists for PHotoEspaña awards, won prestigious distinctions, and been featured in exhibitions, such as the contemporary photobook exhibition Books that are photos, photos that are books at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, and Photobooks: Here and Now at the Fundaciò Foto Colectania, Barcelona.

Meanwhile, life in Cádiz is quiet for La Kursala. The university keeps its budgets frozen. All Cuadernos books can be downloaded from the university’s website in PDF format, with images, critical texts, and biographies. “La Kursala does not have a proper webpage yet due to the lack of funds for its production and permanent actualization,” Micó explains. But perhaps keeping structures minimal and affordable, and depending on its books to provide sites for visceral experience, has been precisely what has contributed to La Kursala’s success.

_____

Natasha Christia is a freelance writer and curator based in Barcelona. She is currently coordinator of international editions at Editorial RM and a member of the research group Arqueologia del Punt de Vista. natashachristia.com

The post Publisher Profile: Natasha Christia on La Kursala appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 17, 2014

Aperture #217 – Editors’ Note

The following note first appeared in Aperture magazine #217, Winter 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

Natalie Czech, A Poem by Repetition by Emmett Williams II , 2013

Are images trumping the written word? Even in the age of instant visual communication via Instagram and Snapchat, this isn’t a new question. Photography critic and curator Nancy Newhall wrote in 1952, in the first issue of this magazine, of which she was a founder: “Perhaps the old literacy of words is dying and a new literacy of images is being born. Perhaps the printed page will disappear and even our records [will] be kept in images and sounds.” Penned more than sixty years ago, Newhall’s words sound remarkably prescient now that photographs have come to be described as “chatter” and the culture of books and reading is shifting. A New Yorker blog post earlier this year detailed how smartphone pictures had superseded note taking in one writer’s process; a recent New York Times article proclaimed that “The Emoji have Won the Battle of Words,” referring to the popular pictograph lexicon used in text messages.

We hope (and are fairly certain) that the latter isn’t true, but this issue is set against a backdrop where images are, arguably, placing significant pressure on the written word, whether or not this is a new or old problem. The prolific French writer Hervé Guibert, an accomplished photographer in his own right, prophetically feared that photography could “quickly turn to madness, because everything is photographable.” He is joined in this issue by William S. Burroughs and Kobo Abe, novelists who moonlighted as photographers. Writers Geoff Dyer and Janet Malcolm never developed a practice as photographers, but both have thought deeply and written extensively about images, navigating the tricky business of translating the visual into the verbal. A group of contemporary fiction writers offer varying takes on the pressure images place on what they do—Lynne Tillman smartly reminds us that “fiction is another form of image making,” and Teju Cole makes a case for poetry and lyricism in the age of automated images. Gus Powell, Moyra Davey, Sarah Dobai, and Eamonn Doyle have all looked to works of literature to inform their work as image makers, whether by adopting a formal constraint, borrowing snippets of language, or riffing on a theme. Taking a cue from Burroughs, creator of the “cut-up,” Natalie Czech and Erica Baum reanimate found language— from tactile, printed book pages to unlikely commercial objects (like the effects pedal above)—prompting viewers to reflect on how language can be both read and seen.

Words as inspiration for image making, words as images, images as open-ended fictions, documentary under the influence of fiction—as in the case of Walker Evans and his interest in writing and French literature, explored here by David Campany—are just some of the ways in which image and language brush up against each other in these pages. Perhaps novelist Tom McCarthy gets it right when he says, “in the end the difference between image and word isn’t relevant because ultimately it’s all scriptural…photography is a branch of writing.”

—The Editors

The post Aperture #217 – Editors’ Note appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 14, 2014

Announcing the Winners of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2014

Paris, November 14, 2014—Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of the 2014 edition of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the book’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. Hidden Islam by Nicoló Degiorgis is the winner of $10,000 in the First PhotoBook category. The selection for this year’s new category, Photography Catalogue of the Year, is the separately published, matched set of catalogues Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness and Christopher Williams: Printed in Germany by Christopher Williams, while Imaginary Club by Oliver Sieber is the winner of PhotoBook of the Year. A special mention in that category goes to Vytautas V. Stanionis’s Photographs for Documents.

A jury in Paris selected this year’s winners: Rahaab Allana, curator at the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts; Quentin Bajac, Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator at the Museum of Modern Art; Cléo Charuet, designer and director; Sebastian Hau, curator; and Pierre Hourquet, gallerist, publisher, and designer, who replaced Urs Stahel due to a delay in Mr. Stahel’s schedule.

The initial short-list selection was made by Julien Frydman, director of Paris Photo; Todd Hido, photographer and photobook maker; Lesley A. Martin, publisher of the Aperture Foundation book program and of The PhotoBook Review; Mutsuko Ota, editorial director of IMA magazine; and Anne Wilkes Tucker, photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

“Overall, it was more complicated than I thought,” says Cléo Charuet. “It was a hard task to judge, as it is a hard task to make a book: understanding the work of a photographer, understanding how to make a book attractive but well-suited to the subject.”

Winner of First PhotoBook 2014:

Nicoló Degiorgis, Hidden Islam

“This volume condenses years of research and interaction with members of Muslim communities in northern Italy. It is a sincere book that attempts to bridge local conditions in Italy to a larger European context—and a very strong example of attention to detail and overall concept in today’s independent bookmaking.”—Sebastian Hau

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year 2014:

Christopher Williams, Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness and Christopher Williams: Printed in Germany

“This is a super pure, extremely well-done set of books: the use of bright colors, the perfect selection of papers, the perfect economy and rhythm. It’s very appropriate to what’s happening right now in terms of both design and photography. The book is a perfect response to the material.”—Cléo Charuet

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year 2014:

Oliver Sieber, Imaginary Club

From a range of titles that included both emerging artists and contemporary masters competing for the PhotoBook of the Year prize, the jury selected Oliver Sieber’s Imaginary Club as an extremely well-crafted final manifestation of a photographer’s personal, in-depth project.

Special Mention:

Vytautas V. Stanionis, Photographs for Documents

“Photographs for Documents tells me that these are not just documents; they are lives that are shared on the page. The page becomes a stage. . . . The fragility and simplicity, the humility of the materials themselves, are also pivotal to the overall result.”—Rahaab Allana

_____

The short list is on view in the Publishers section of Paris Photo at the Grand Palais in Paris until November 16, 2014. The exhibition will then travel to the IMA Concept Store in Tokyo from December 9, 2014 to January 18, 2015, and New York’s Aperture Gallery from December 13 to January 29, 2015, followed by exhibitions in 2015 at Photobook Melbourne, Australia, and the Month of Photography Los Angeles.

The short-listed books are also profiled in issue 007 of The Photobook Review, Aperture’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook. The PhotoBook Review is available for free at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore in New York and mailed to all Aperture magazine subscribers.

See the entire PhotoBook Awards 2014 short list.

The post Announcing the Winners of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2014 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 13, 2014

Review: Noemi Smolik on Thomas Ruff

THOMAS RUFF, ‘r.phg.05_II,’ 2014. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Thomas Ruff’s “Photograms,” a series begun in 2012, represents most of his new exhibition at the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf: after becoming fascinated with the photograms of artists such as Lászlo Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, Ruff began to experiment with the process himself, but Ruff transfers the analog technique into digital. The darkroom is instead set up inside a computer, with objects three-dimensionally projected, exposed to light, and moved. Through this controlled procedure, virtually exposed waves, crystals, spirals, lenses, and patterns leave their imprints on virtually generated paper. The C-print process then transfers these traces to real pieces of paper measuring approximately six-by-five feet. The resulting framed photograms create an impression that is spherical and remarkably pictorial. Some of these images are highly geometric in composition, with an illusionary depth created by the interplay of light and shadow. Others are chaotic or arbitrary; some are crystal clear while others are indistinct; some are bluish or greenish in tint; and others display astonishingly vivid shades of luminous yellow, red and blue, such as the image phg.05 III (2013). They are created without any use of the camera lens, and, consequently, these images expand the range of Ruff’s photographic experiments, the complexity and diversity of which are without equal in the contemporary art scene.

THOMAS RUFF, ‘phg.09_II, 2014,’ © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

The “Interiors” (1979–1983) and “Stars” (1987–1992) series’ are also on view. The small “Interiors” images show the meticulously photographed home décor of Ruff’s parents and friends from the Black Forest region; they testify to a subtle but frightening smugness and narrow-mindedness.

THOMAS RUFF, ‘Interieur 1A, 1979,’ © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Giant black photographs of stars, which Ruff acquired from the European Southern Observatory, could potentially serve as an effective contrast to the “Interiors,” but within the constellation of this exhibition, however, they do not, which highlights issues with exhibition with the installation and presentation of the various individual series.

THOMAS RUFF, ’17h 38m/-30°,’ 1990, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

The images from the “Night” series (1992–1996), positioned side by side can also produce a slightly bland effect. Inspired by the nighttime photographs that suddenly began appearing on television during the First Gulf War (1990 – 1991), Ruff also began to make use of night vision devices. But he employed them to photograph utterly peaceful courtyards, streets and house entrances in his city of Düsseldorf. These images have a greenish tinge, due to the device’s amplification of low light, and they succeed in wresting light impressions even from the darkness. While making inroads into dark with light, they still leave a mysterious, enigmatic, or even dangerous impression.

THOMAS RUFF, ‘Nacht,’ 1992. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

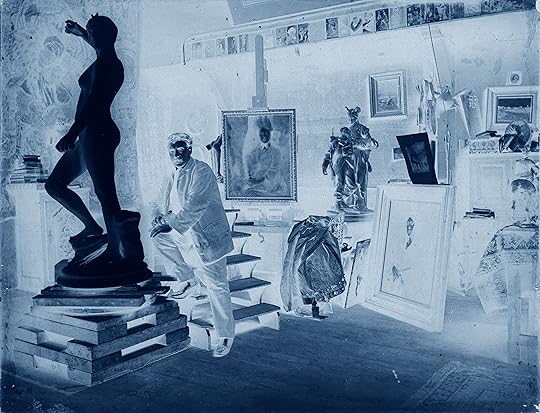

The 2014 series “Negative,” which appears in the same gallery, features blue-tinged images of black-and-white photographs from the nineteenth century that have been transformed back into negatives. The images depict studios of the era when the competition between paintings and photographs began as well as portraits, oriental landscapes, and nudes. With their bluish tinge, a result of the reversion to the negative, these images create the impression a world of ice that has become almost transparent, from a time when the photograph still served as a document. With this new series, Ruff returns to the beginning of his artistic development, when he was dealing with documentary photography. Here, he has turned this kind of photography upside down.

Noemi Smolik is a critic living in Bonn, Germany, and Prague.

Translated from German by Alan G. Paddle.

“Thomas Ruff: Lichten” runs through January 11, 2015, at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf.

THOMAS RUFF, ‘neg◊artists_01,’ 2014. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

The post Review: Noemi Smolik on Thomas Ruff appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers