Aperture's Blog, page 173

October 25, 2014

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision

Alex Webb, Havana, 1993, and Rebecca Norris Webb, Blue Secondhand Prom Dress, Rochester, NY, 2012

Do you know where you’re going next with your photography—or where it’s taking you? This intensive weekend workshop will help photographers begin to understand their own distinct way of seeing the world. It will also help photographers figure out their next step photographically, from deepening a unique vision, to discovering and completing a long-term project, to translating a body of work into books and exhibitions. This is a workshop for serious amateurs and professionals alike, taught by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, a creative team which often edits projects and books together. This includes their two recent joint books Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image (Aperture, 2014) and Memory City (2014); Alex’s The Suffering of Light (Aperture, 2011); and Rebecca’s My Dakota (2012).

This weekend workshop will begin with reviews of each participant’s work on Saturday morning, a process that will spark a larger discussion about various photographic issues, including the process of photographing spontaneously and intuitively; how to edit photographs; how to work in cultures different from one’s own; and how long-term projects can evolve into books and exhibitions. The first day will end with a group editing exercise and an optional photography or editing assignment. Sunday will be dedicated to reviewing each participant’s assignment, as well as a series of presentations about bookmaking and exhibitions that will end with an informal Q&A session with the Webbs. Lunch will be served both days.

Alex Webb is best-known for his vibrant and complex color photography, often made in Latin America and the Caribbean. He has published eleven books, including Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (with Rebecca Norris Webb, 2009) and The Suffering of Light (Aperture, 2011), a collection of thirty years of his color work. Webb became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1979. His work has been shown widely, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. He’s received numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, and GEO, among other publications.

Rebecca Norris Webb, originally a poet, has published three photography books that explore the complicated relationship between people and the natural world: The Glass Between Us (2006), Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs from Cuba (with Alex Webb, 2009), and My Dakota (2012). Her fourth book, Memory City (with Alex Webb, 2014), is a meditation on film, time, and the city of Rochester, New York, in what may be the last days of film as we know it. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; George Eastman House, Rochester, New York; Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York; and Robert Klein Gallery, Boston. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Time, National Geographic, and Le Monde Magazine.

Tuition: $600 ($540 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture members at the $250 level and above)

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions or to register now.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Finding Your Vision appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Larry Fink: Choreographing Miracles

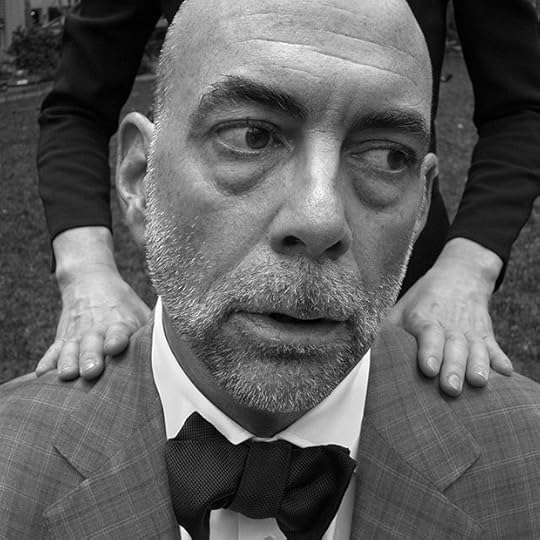

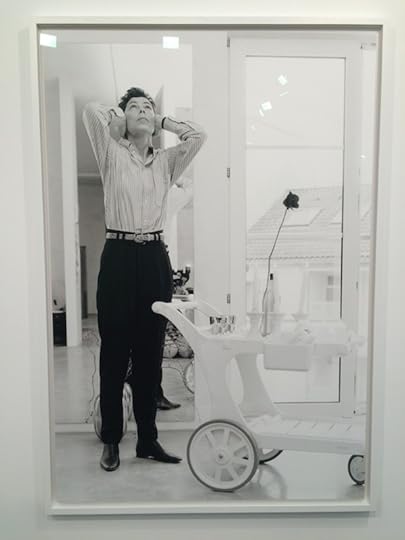

Larry Fink, Donald Antrim, 2014

“My picture-making process is not so much about making a photograph as it is about paying extreme attention to what I’m most attracted to, what is drawing my interest. For the most part, I’m hyperstimulated at all times; my life is a massive run-on sentence of stimulation. I’m always aware of what’s holding my interest while I’m shooting, but I’m not analyzing my desires to the point of cooling things down—just to the point of understanding impulses as they come.”

—from Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation (Aperture, 2014)

Larry Fink’s photographs merge style, vision, and content so seamlessly that their meaning strikes us as given: something known and shared—an unequivocal truth about what things looked and felt like there in front of the camera. The art of this lies in Fink’s ability and willingness to penetrate the scene at hand, even when the politics may not be to his liking. Join Larry Fink for this workshop to explore the relationship between subject and photographer, luck and happenstance, style and meaning, and the logic of geometry.

Included in the workshop will be a portfolio review followed by an individualized assignment. Students will have three weeks to complete the assignment before returning for a group critique led by Fink.

Larry Fink has been a professor at Yale University School of Art, New Haven; Cooper Union School of Art and Architecture, New York; Parsons The New School for Design, New York; and Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia. Currently, he is a tenured professor of photography at Bard College. His work has been widely exhibited in the United States, including solo exhibitions at Light Gallery, New York; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge; Museum of Modern Art, New York; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture members at the $250 level and above)

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions or to register now.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture. We recommend, for instance, that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all electrical appliances.

The post Larry Fink: Choreographing Miracles appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 24, 2014

The Icons by Inez & Vinoodh

This piece was originally published in Aperture Magazine issue 216, Fall 2014, Fashion.

Every fashion designer is consistently delving into the past, basing a collection on a string of memories, like shoulder pads worn by clubbers in the ’80s or the platform shoes David Bowie put on when he performed as Ziggy Stardust. Our photography stems from a similar nostalgia. Fashion is a language made up of a visual code of status symbols. We play with this code, and sometimes subvert it; without this play on references the images become too abstract. Building a character based on myriad elements—paintings, movies, music videos, pictures of your mother—is what keeps the process exciting. You might feel the references but you can’t determine their source. What follows is a selection of images by some of fashion photography’s giants, whose work has influenced four decades of fashion, photography, and advertising and has been important to the development and motivation behind our own work. One might say that in today’s professional climate, in which clients want to see their campaign images before they are even shot, you’re only as good as your references.

Richard Avedon, Verushka, dress by Bill Blass, New York, January 4, 1967 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

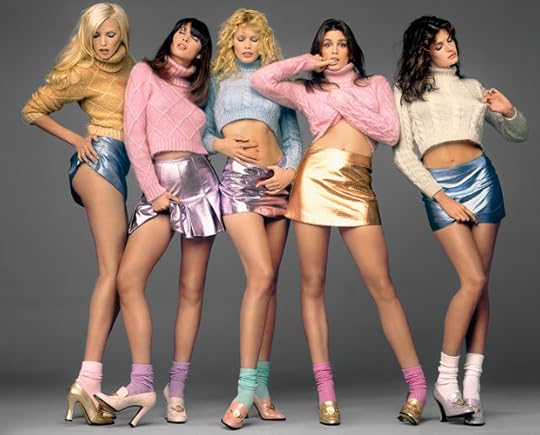

Richard Avedon, Nadja Auermann, Christy Turlington, Claudia Schiffer,

Cindy Crawford, and Stephanie Seymour, Versace Fall/Winter 1994–95 Campaign, New York, April 14, 1994 © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon

Avedon had a brilliant way of turning everyone he photographed into a hero. It was not necessarily about beautifying people, but about making them into iconic versions of themselves. He was attentive to proportion and body positioning, and able to find that one quality of someone’s physiognomy that is remarkable, whether grotesque or elegant, and bring it to the foreground. No photographer controlled body language better. Everyone is inspired by this series with Verushka, which is the epitome of movement in the studio. Almost every studio shoot today is orchestrated this way.

Avedon could translate the mood of a period but never lost his own voice. His collaboration with Versace over many years, similar to that of Yves Saint Laurent and Helmut Newton, was one of the most incredible between a designer and a photographer in which both the people and the clothing look larger than life. This photograph of five of the most beautiful women in the world is so stylized and glamorous (down to their ankle socks), yet he manages to keep their exaggerated gestures feeling candid and humorous. Apart from, of course, having the best lighting in the world, you immediately know that it’s an Avedon because the people appear magnificent. He must have been truly interested in everyone he photographed.

Guy Bourdin, Charles Jourdan, Spring, 1978 © Estate of Guy Bourdin; courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London; and Art + Commerce, New York

Guy Bourdin, Charles Jourdan, Spring, 1979 © Estate of Guy Bourdin; courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London; and Art + Commerce, New York

Guy Bourdain

Growing up with a mother who went to Paris twice a year to see the runway shows and who brought back issues of Vogue Paris, I (Inez) flipped through the magazine at an early age and thought that the way Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin portrayed women was the way women were meant to be: bold, strong, wild, erotic, and independent. Bourdin definitely informed pretty much all of my early photography.

We’ve all heard the stories of how precise and demanding he was. You can tell that everything was preconceived, that it must have started with a sketch somewhere. This in-camera collage, in the picture opposite, shows how he merged abstraction with content like no one else. His consistent use of strong pink and red makeup, pale skin, and super curly hair (ideally red) has influenced many hair and makeup artists and is basically an industry standard.

Bourdin pushed his models to assume really wild expressions; sometimes he actually scared them. He must have been reacting to the ’50s, when everything had to be very perfect, proper, and clean, and then the ’60s, when everything was “peace and love.” In his work from the ’70s you feel something dubious is happening outside the frame. That dark side is inspiring, and his use of bodies, color (his painterly approach), lighting, and humor has been a big influence, especially this image, one of Bourdin’s most genius, in which a photograph of John Travolta is propped between the model’s legs. We love the use of color along with her body position. And, as in all his pictures, your eye immediately goes to the shoes.

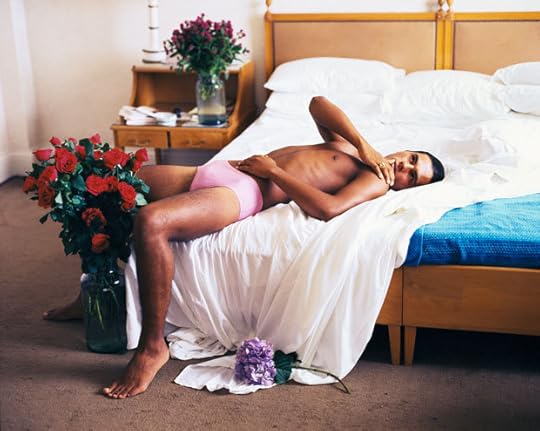

Annie Leibovitz, Anjelica Huston, 1985 © Annie Leibovitz / CONTACT PRESS IMAGES

Annie Leibovitz, Brad Pitt, Las Vegas, 1994 © Annie Leibovitz / CONTACT PRESS IMAGES

Annie Leibovitz

We saw this image of Brad Pitt for the first time at Annie’s exhibition in Stockholm, and were struck by the audacity of the leopard-print pants, the boots, the pajama shirt, the red blanket on the bed, and the nasty carpet—the sharp contrast between him and his surroundings. Annie pushes her subjects to become part of a scene or plot. Others might photograph Pitt, a male superstar, as heroic and strong, whereas here he’s passive but dressed so flamboyantly. On the other hand, Anjelica Huston wears a riding costume, looking very masculine, especially with her almost crotch-grabbing hand gesture. Anjelica has been hugely inspiring in our world, in fashion and fashion photography, for her work with Guy Bourdin, Helmut Newton, and Bob Richardson. These pictures are both portraits and fashion images. There is a simplicity to the images and their production, but the people are absolutely magnificent.

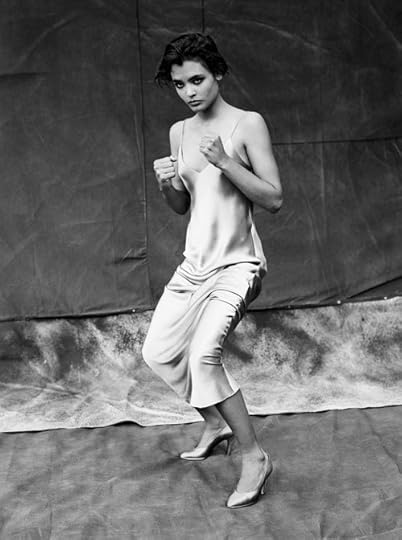

Bruce Weber, Talisa, Bellport, New York, 1982 © Bruce Weber

Bruce Weber, Gustav, Room 500, Copacabana Palace Hotel, Rio de Janeiro, 1986 © Bruce Weber

Bruce Weber

Bruce makes the most masculine men on earth look as elegant and beautiful as the most beautiful women, and he makes the most feminine women look like the strongest boys. It’s androgynous without being obviously androgynous. This image at right of Talisa, in her boxing stance, is the ultimate version of that. There is a generation that is absolutely inspired by Bruce and Herb Ritts for their interpretation of this sort of androgyny. You could say Bruce comes from the line of thought that Helmut Newton started with Yves Saint Laurent, when he set women free by using masculine codes, dressing them in tuxedos and pantsuits. We’re always trying to find a duality in a person: half male, half-female, a blurring of identity.

Bruce’s 1986 book O Rio de Janeiro has been a huge influence. His documentary approach is liberating and even stimulating. You’re in a place, you have an incredible subject, the light is the light that’s there. Now make that person incredible. That’s what we admire in Bruce’s work, that there’s no artifice. But we think that’s the bottom line for every photographer: when you’re really interested in the people you’re photographing, you get more than just the registration of someone.

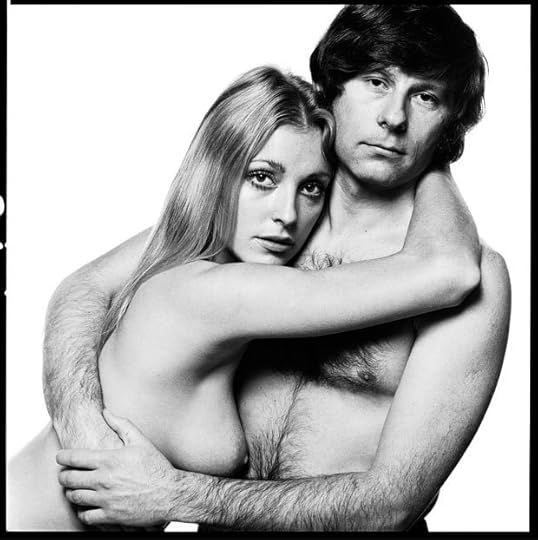

David Bailey, Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski, 1969 © David Bailey

David Bailey, Jane Birkin, 1969 © David Bailey

David Bailey

Bailey was a master of freezing a moment and registering energy. In this image of Jane Birkin, the lighting is harsh and unsubtle. Bailey went after people he really wanted

to meet, or he found models on the street if he couldn’t find the right one at an agency. Humor, bravado, and flamboyance all come through in his raw, unapologetic portraiture—you sense that his models made themselves vulnerable to him. This directness is the most honest way of working with a subject. For example, if we want to shoot someone naked, we will tell them immediately. You feel that kind of directness in his work. It’s like: “This is what it is. Are you going for it? Are you submitting yourself to it? Here we go.”

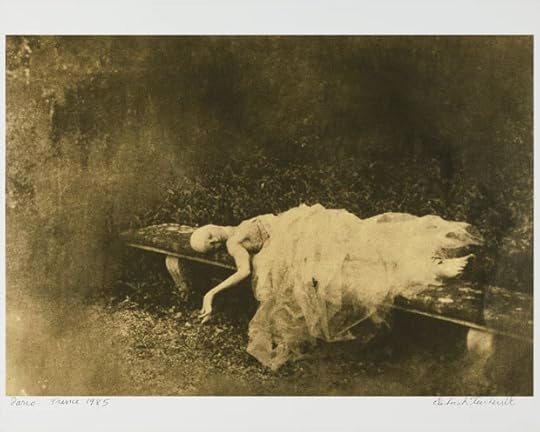

Deborah Turbeville, Parco, Paris, 1986. Courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

Deborah Turbeville, Valentino, Vogue Paris, 1977. Courtesy Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

Deborah Turbeville

This image above has been in my scrapbooks ever since I (Inez) can remember looking at photography. The way the model’s head is wrapped. This decaying environment. The broken-doll position; the faded, uncanny romantic atmosphere that seems based on an old painting; the way Turbeville would lay out her books with pieces of tape stuck to her photographs—all of that influenced me. There’s a series that we did for The Face, with the model Maggie Rizer, based on this image; she had a headwrap like this girl’s.

Group shots, like the one above, are so difficult to do, at least successfully. Turbeville was a master at using negative space and catching everyone at the right moment. She must have been amazing at directing people in such a way that they would let go. Her models are often a little bit neurotic, a little on the verge of falling apart. They are unsure and unavailable, which we find attractive, but there is an incredible delicateness. We’re always amazed at how she manages to construct these group shots so beautifully, which is again a hard thing to do because you’re setting up a fashion photograph. You’re dealing with shoes and clothes. It’s incredible how she directed her subjects, and found a way to make things feel personal, as though there is complicity among the women.

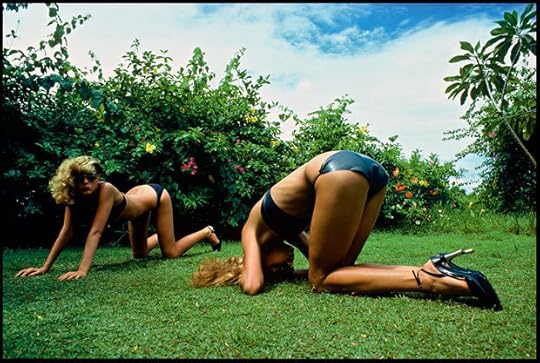

Hans Feurer, Stern, 1978 Courtesy Hans Feurer / The Licensing Project

Hans Feurer

In the 1970s, Feurer opened up a studied, controlled idea of the fashion photograph while shooting for Kenzo. He worked with a long lens, at a distance, directing models with a megaphone in the early morning and at the end of the day when the light was the right temperature. Maybe using the long lens had to do with him not really wanting to engage with the women in the photographs but rather capturing them voyeuristically. The energy and the movement of the women in his photographs is sexy and creates a very unexpected body language. Women float in space in such an incredible way, showing the clothes so beautifully. When he worked with Kenzo it was a time in fashion that mixed utilitarian clothes and elegance. In this photograph at right, you’re not sure what’s going on: she’s wearing a very folkloric outfit with a military hood and gloves and mountain-climbing shoes. There are all these different messages.

This image above we honestly thought was by Guy Bourdin. But then we found out, along the way, that this was a Feurer. Let’s say there is his work with Kenzo, and then there is his work that has a sporty, fitness side to it. With this image, because of the contorted bodies and the strangeness of the composition, there is eroticism, but in his work it’s never obvious nor cheap.

______

Inez & Vinoodh are a photography duo based in New York. They guest-edited Aperture‘s “Fashion” issue.

The post The Icons

by Inez & Vinoodh appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction

Event co-chair and trustee Sarah Gore Reeves, Juan Carlos Castro, and Delphine Gesquiere. Photo by Max Campbell

Alec Soth and Joe Purdy. Photo by Max Campbell

Darius Himes and Allison Hadar. Photo by Max Campbell

Jock Reynolds and Board of Trustees Chair Cathy Kaplan. Photo by Max Campbell

David Campany, Denise Wolff, and Executive Director Chris Boot. Photo by Max Campbell

Bob Gruen and Elizabeth Gruen. Photo by Max Campbell

Kate O’Shaughnessy, Chris Denny-Brown, and Lauren O’Shaughnessy. Photo by Max Campbell

More than 800 guests attended The Open Road, Aperture Foundation’s Benefit Party, on Tuesday, October 21. The event, a tribute to Robert Frank, took its theme from the newly released Aperture book of the same title, in which David Campany chronicles the uniquely American tradition of photography about, or taken on, the road.

Photo by John Stillman

Guests register to bid through Artsy for the Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit silent auction. Photo by Katie Booth

Designed by Merissa Lombardo Studios. Photo by John Stillman

A flatbed truck served as a photobooth, designed by Merissa Lombardo Studios. Photo by Katie Booth

At Terminal 5, vintage neon signs for “No Vacancy” as well as “Cocktails,” stripped right from the road, decorated the hangar-like space, alongside gas pumps and a pick-up truck photo booth, designed by Merissa Lombardo Studios. In the downstairs space, the Artsy-powered silent auction was well underway at 6 p.m., with more than 50 lots on sale that took the open road as cue. From a 1970s Patti Smith on the Bowery by Godlis to a near-abstract image of birds in the sky by Richard Misrach, the small works, “Postcards from the Road,” expanded on the theme of travel; souvenir postcards by Instagram and Aperture were given to guests to trade throughout the night.

Event co-chair Eve Reid, Courtney Joyner, Richard Joyner, and Cheryl Joyner. Photo by Katie Booth

Trustee Celso Gonzalez-Falla, Robert Frank, and Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla. Photo by Katie Booth

Event co-chair and trustee Melissa O’Shaughnessy and trustee Annette Friedland. Photo by Katie Booth

Julie Saul, Mary Sliwa, Yancey Richardson, trustee Elaine Goldman, and Rita Galliani. © Patrick McMullan

Elizabeth Kahane and Kellie McLaughlin. Photo by Katie Booth

Lesley A. Martin, Bill Hunt, Melissa Harris, and Paul Kopeikin. Photo by Katie Booth

Trustee Michael Hoeh and trustee Jessica Nagle with guest. Photo by Katie Booth

Trustee Stuart Cooper, Tierra Dorsey, and Regina DeLuise. Photo by Katie Booth

Cory Jacobs, Justine Kurland, Jason Schmidt, and guest. Photo by Katie Booth

Jock Reynolds, Deputy Director Sarah McNear, Ian Wardropper, trustee Celso Gonzalez-Falla, and Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla. Photo by Katie Booth

Executive Director Chris Boot, Bruce Davidson, Emily Davidson, and Joe Purdy. Photo by Katie Booth

Kristin Doggett, Olivia Bee, and Drew Doggett. Photo by John Stillman

Photographers from Mary Ellen Mark to Paul Graham to Aperture magazine’s fall 2014 issue guest editors Inez & Vinoodh were in attendance to celebrate. Also among the crowd were photographers Justine Kurland, featured in The Open Road, Bruce Davidson, Bob Gruen, and Instagram influencer Olivia Bee. From the world of media, Aperture was joined by Kathy Ryan of the New York Times Magazine–her book Office Romance is published by Aperture this month.

Chris Boot, Pierre-Alexis Dumas, and Board of Trustees chair Cathy Kaplan. Photo by Katie Booth

David Campany. Photo by Katie Booth

Robert Frank seated among guests. Photo by John Stillman

Before the start of the evening’s program, a new programmatic alliance between Aperture Foundation and the Hermès Foundation was announced, to begin in 2015. The two will work together to commission, exhibit, publish, and promote the art and craft of contemporary French and American photography, said Aperture Executive Director Chris Boot. In attendance was Pierre-Alexis Dumas, President of the Hermès Foundation and Artistic Director of Hermès, who gave a speech focused on the context of the partnership.

To begin the Open Road program, Chris Boot made a celebratory toast to Leica’s 100th anniversary of its original model. Author David Campany then paid tribute to Robert Frank with a moving speech about the importance of Frank’s contribution to the history of photography. “When I look at those photographs, I can feel an artist trying to give his whole nervous system to what he’s trying to do, and who can ask for anything more than that,” he said. “In a world of false confidence, what I respond to is Robert’s skepticism and his open heartedness. ”

Joe Purdy, Billy Bragg, and Alec Soth. Photo by Katie Booth

The program centered on a performance of words, photographs, and video from Alec Soth, Billy Bragg, Joe Purdy, and Isaac Gale, created for Aperture on a road trip down the Mississippi in August.

August Uribe of Phillips. Photo by Katie Booth

The Kills. Photo by Max Campbell

The Kills. Photo by Max Campbell

At the anticipated live auction, auctioneer August Uribe, worldwide co-head of contemporary art at Phillips, presided over the sale of 9 commissioned works by photographers, including Justine Kurland, Alex Prager, Todd Hido, and Joel Meyerowitz. Just before the bidding for the premier lot–a print by Robert Frank donated by the artist–the crowd went nearly silent; after rigorous bidding, the work fetched $95,000.

Once the sales had been set, The Kills took the stage, as guests sipped on Goose Island beer, Perrier, and Espolòn tequila cocktails, followed by a DJ set by AndrewAndrew.

______

The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party was made possible with the generous support of presenting sponsor Leica Camera AG. Additional support provided by: Turon Travel, Preferred Aperture Foundation travel agency.

Supporting Sponsor: Pinch Food Design

Associate Sponsor: Phillips

Friend Sponsors: Hahnemühle USA, Fotocare, LTI Lightside Photographic Services, Espolòn Tequila, Perrier, Goose Island Beer Company, Merissa Lombardo Studios, Wölffer Estate Vineyard,

Media Sponsor: Patrick McMullan Company

All photographs by Katie Booth, Max Campbell, and John Stillman © Aperture Foundation.

The post The Open Road Aperture Foundation Benefit Party and Auction appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 21, 2014

Meatyard’s “Ghosts” On View at Team Gallery in New York

Untitled, ca. 1957 / printed ca. 1957 (all images courtesy of team (gallery, inc.), fraenkel gallery, and the estate of ralph eugene meatyard)

Untitled, ca. 1959 / printed ca. 1959

Untitled, ca. 1959 / printed ca. 1959

Untitled, 1959

Untitled, 1961

Untitled, ca. 1968-72 / printed ca. 1968-72

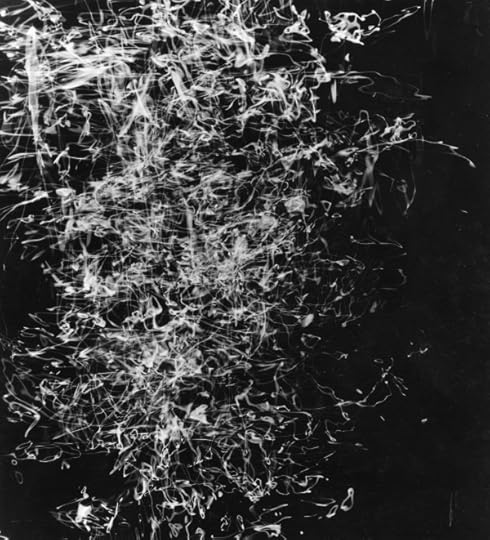

A new exhibition at New York’s Team Gallery, titled “ghost outfit,” sets the eerie and enigmatic work of Ralph Eugene Meatyard in conversation with that of Dan Flavin and Robert Janitz, as organized by director Todd von Ammon. Through sculpture, painting, and photography, the show brings together disparate artists who all “made drawings with light,” as von Ammon put it.

Little recognized in his lifetime, Ralph Eugene Meatyard became widely known during the 1970s photo boom, shortly after his death at age 46. Born in Normal, Illinois in 1925– a detail critics often point out, given the self-taught photographer’s macabre imagery– Meatyard alternately experimented with early photographic techniques of abstraction and staged scenes rife with literary allusion.

Von Ammon first discovered Meatyard’s work as a child, in an Aperture Foundation monograph published in 1974 that his family owned. As the exhibition began to materialize around Flavin and Janitz, he felt the spot for a third dominant medium should belong to Meatyard, with “light on water as a formal corollary” uniting the three artists. He saw Meatyard as, “the opposite of Flavin, who was slouching toward this metaphysical purity while Meatyard was muddying his hands.”

Photographs in the front gallery represent the abstract, more ethereal version of Meatyard, with motion blurs, swirling perspectives, and scattered light, alongside Janitz’s painterly streaked canvases. In the back gallery, a darker image of the photographer emerges; the cool green neon of a Flavin glows against Meatyard’s black-and-white gelatin prints of skull masks, dolls, and a zombie hand reaching out from a grave.

“What ultimately happened is that the show grew this extra limb and became about the ghost, the mask, or obscurity in terms of light,” von Ammon adds, noting themes commonly attributed to Meatyard’s work. The photographs came directly from Madelyn Meatyard, the artist’s widow, who relayed to von Ammon that the show marks one of the few occasions Meatyard’s work has been shown in such a decontextualized setting, among the likes of artists such as Flavin.

“The show is about stripping these artists of their previous associations,” von Ammon says, “Giving it some kind of elevated strangeness. We don’t mitigate that, we want to amplify that.”

The show, which opened on October 19, runs through November 16– overlapping Halloween. To follow, von Ammon adds, “I didn’t plan on the show being so goth.”

–Alexandra Pechman

The post Meatyard’s “Ghosts” On View at Team Gallery in New York appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 17, 2014

The Howard Chapnick Legacy (Video)

On Monday, September 22, Aperture hosted a special evening to honor Howard Chapnick (1922–1996), a legend of photography, long-time head of the Black Star Agency, and author of The Truth Needs No Ally: Inside Photojournalism. The evening was hosted by Michael Itkoff of Daylight Books, a 2006 recipient of the Smith Fund’s Howard Chapnick Grant. Past Chapnick grantees Marie Arago, Ryan Libre, Liza Faktor, and Richard Steven Street shared some insight on their projects, with additional remarks by Smith Fund board members John Morris and Rich Clarkson, and trustees Aaron Schindler and Phil Block.

The evening was one of the W. Eugene Smith Talks, a series of collaborations between the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund and Aperture Foundation.

For more information about the Howard Chapnick Grant, visit smithfund.org.

The post The Howard Chapnick Legacy (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Bernard Plossu on Movies and Mexico

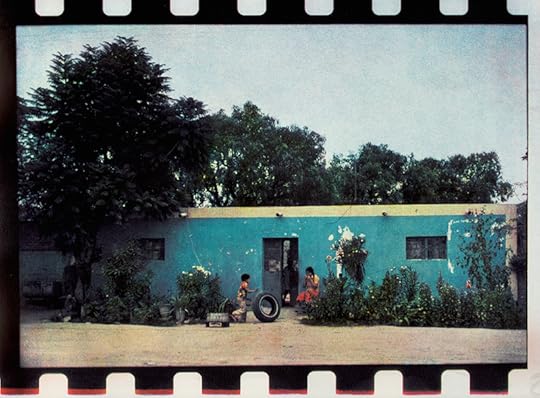

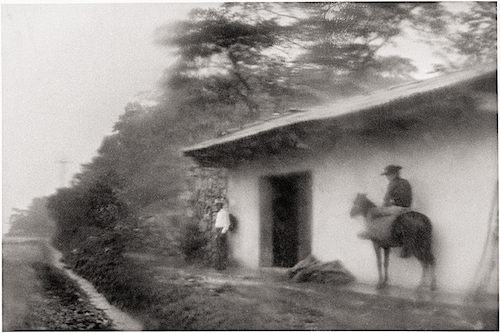

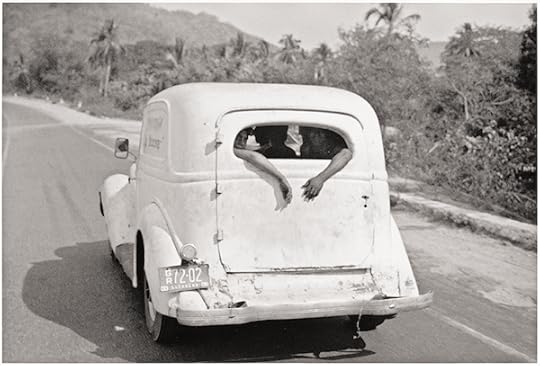

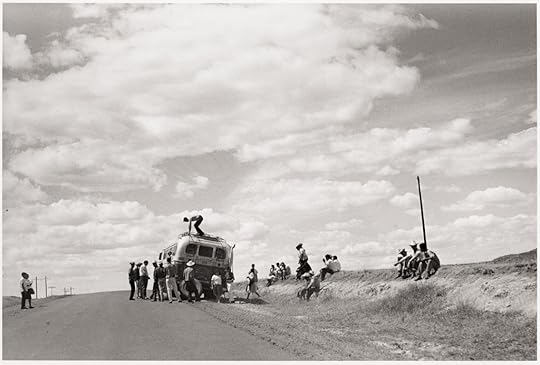

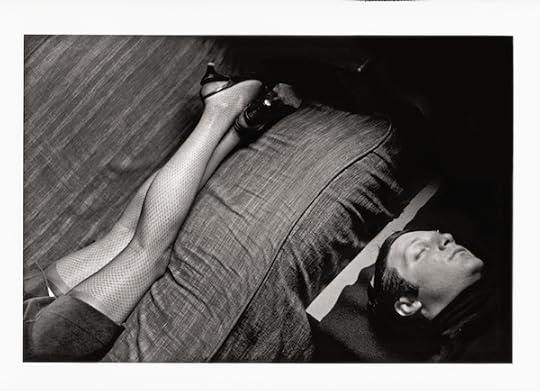

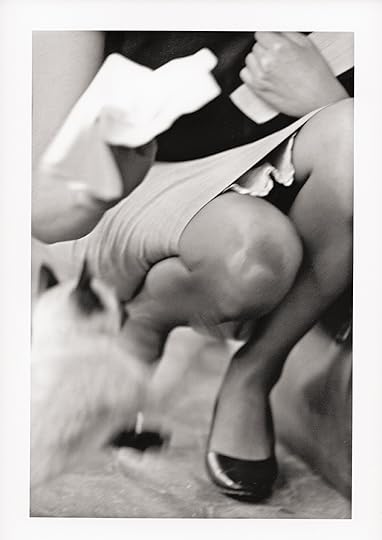

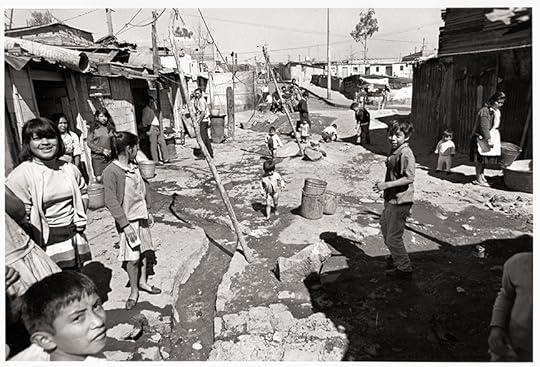

Bernard Plossu from the Fresson Color series, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014). © Bernard Plossu.

French photographer Bernard Plossu has traveled extensively throughout his life, visiting the jungles of Chiapas in Mexico, the American West, India, the Aeolian Islands, and Niger. From the 1960s through the ’80s he made four extended trips to Mexico to photograph people, landscapes, and a culture in flux. ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México, published by Aperture this spring, captures the bohemian adventure of this traveler’s journeys. In France, his pictures have transfixed generations of young people, who cherish him much in the same way young Americans celebrate Jack Kerouac.

Regarded as a leading figure in French photography, Plossu’s photographs have been exhibited internationally, including at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia, Spain; and Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, France. He has published numerous books, including Le Voyage Mexicain: L’integral, 1956–1966 (1979), African Desert (1987), Forget Me Not (2002), Bernard Plossu’s New Mexico (2006), and Europa (2011). In 2008 he was the recipient of the CRAF International Award of Photography.

Paula Kupfer spoke with Plossu earlier this year about the experience of reliving his trips to Mexico through his pictures, the influences of his youth, and the importance of cinema in his work.

Paula Kupfer: Your career has involved traveling and photographing all over the world. What is it like to revisit your work from Mexico through the publication of ¡Vámonos!?

Bernard Plossu: When I started photographing in Mexico in 1945, I was twenty years old. I was taking lots of pictures but I had no idea that it would be my future job. Looking at the book now is revealing: I see the way I was influenced by cinema, especially Westerns—especially Vera Cruz (1954), by American filmmaker Robert Aldrich. Veracruz takes place in Mexico and it was filmed on location; I didn’t know this until I traveled there myself. I think I was looking for the landscape I had seen in the film: the scenery, the marketplace. Some of my photographs seem straight out of the film.

Bernard Plossu from the series From The North Mexican Tropics, 1981, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

The question is: have I changed in half a century? I may have changed age-wise, but style-wise I still use only a 50 mm lens, which is a very sober vision. I still take my pictures without gimmicks.

PK: Do you continue to have a rapport with Mexico today?

BP: I’m constantly connected with all my friends from Mexico by mail. I left Mexico in 1981 and the United States in 1985; I haven’t been back since then. I got very involved working in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Poland. But I stayed in touch with all my friends—Mexicans and Americans. A few years ago, I had a show at the Monet Museum in Giverny. Many friends came from America; we had a big meeting and we decided to meet every year. This year we went to Scotland. We’re trying to stay in touch and not disappear. By now some of our children know each other, also.

Bernard Plossu from the series Mexican Journey, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

PK: Do you have any plans to visit Mexico again?

BP: Yes. I am planning a trip to Mexico in October. The whole gang wants to come along.

PK: What was the influence of the original photography book Le voyage mexicain when it was published in 1979?

BP: Many young people have told me they traveled with the small edition of Le voyage mexicain in their pocket—it was a small paperback. They looked to it as a model. But it wasn’t a fine-art book on Mexico; it was a book on being twenty and traveling and going anywhere and doing anything. Although it’s an important book for me, I didn’t take it that seriously. More than an art style, it was a lifestyle.

Bernard Plossu from the series Mexican Journey, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

PK: What was the most influential aspect of your Mexico travels?

BP: It was the discovery of some of the Mexican painters. When I was in France I had no idea about painters like Siqueiros, Orozco, and Goitia. We all know about Diego Rivera in France—he’s big like Matisse, very decorative. Siqueiros, Orozco, and Goitia are more like German Expressionists, they’re earthier. Their paintings are less beautiful; they’re rougher and better at capturing the Mexican land. These painters really changed my taste in art. I went from very traditional French paintings to very gutsy painters and this is one of the lessons—one of the influences—that I got from my Mexican travels. And photography of course, with Álvarez Bravo . . .

PK: . . . and Tina Modotti?

BP: I’m very fond of Tina Modotti—I was just going to say that. To me, she’s the lady of the twentieth century. Not only a great photographer, she was also a very strong-minded woman. Her statements, her life, her involvement, her politics—she’s an amazing figure. How do I say this without being negative? Everyone talks about Frida Kahlo. Of course, she’s special, but I wish people would talk more about Modotti.

Bernard Plossu from the series The Border, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

There are a couple photographers, Héctor García and Nacho López, who impressed me. They have the same style as Robert Frank, but I don’t think they’re known here in France. They’re known in Mexico; they’re major photographers—very, very strong.

PK: People have written that your work falls somewhere between two Bressons: photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson and filmmaker Robert Bresson. Where do you see yourself?

BP: What means most to me is the influence of cinema. To make it short, I’m much more interested in the mood of the photographs than in the composition of the photographs. With all respect to Cartier-Bresson, many people tell me,“You are the ‘non-decisive’ photographer.” I don’t mean to pun the master—I’m not doing a copy of Cartier-Bresson. I’m more interested in the non-decisive: the little nothings that may not be very important, apparently, but that are important, in life and in seeing with the camera.

Bernard Plossu from the series Mexican Journey, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

PK: ¡Vamonos! includes 35 mm black-and-white and color Fresson prints. What are your preferred types of film and processes now?

BP: In my days, in the ’60s and ’70s, I used the same film I use now: Kodak Tri-X. But the color we used was slides, Kodachrome. Very good quality, but there’s no Kodachrome left, so I use negative film. I use, like many people, Fujifilm 200 ISO. The printing is still traditional black-and-white, no gimmicks, no black skies, nothing fancy—when something is gray, it has to be gray.

Bernard Plossu from the series Mexican Journey, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

In color, I’m very faithful to Fresson printing. I don’t know how much you know in the States about Fresson printing. It’s a fourth-generation darkroom in Paris, in the suburbs, with charcoal prints—very matte, very grainy. They give a mood to the photograph that is similar to that of black-and-white. This is why I don’t hesitate mixing them. Now I’m working with the grandson, who is forty years old. Before that I worked with the father, and the grandfather. It’s a mystique, the Fresson prints. The people who know about it and print with it know. It’s very special.

PK: How did your childhood lead you to a career in photography?

BP: I was born in Vietnam; in those years, there were many people living in the colonies and abroad. Some people need it—like me. I could’ve never spent my whole life living in France. The world is way too big. We returned to France after the Second World War, and I was raised in Paris, on the right bank.

When I was thirteen, my father took me to the African desert, the Sahara, and it opened my eyes—the different scenery, people, smells. He bought me a small Brownie camera and I began to experiment.

From sixteen to nineteen, I didn’t go to school very much. I spent my time at the cinémathèque in Paris. I was very attracted by the imagery of cinematography, so instead of working on math, I went to see movies. I got to see all the films by Bresson, Mizoguchi, Carl Dreyer, Buñuel. I learned about images at the cinémathèque.

Bernard Plossu from the series Mexican Journey, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

At this time, my mother had one good book of photography, by Izis [Israëlis Bidermanas]. It’s a book about Paris, black-and-white pictures. And my godfather was married to a painter and for my birthdays, I got art books on Klee, Mondrian, Kandinsky. I made some oil paintings—they were not good. They were copies of Mondrian. Instead, it’s cinema culture that gave me my photo roots. All these together made Le voyage mexicain.

PK: Did you make any films yourself?

BP: I’ve made little films with 8 mm and Super-8 cameras. In Mexico, I filmed the markets, Oaxaca, the people. Before Mexico, in Paris, I filmed my girlfriend. She was very beautiful; she was my Monica Vitti, my Anna Karina—the actresses of nouvelle vague. I spent a lot of time with a great movie-maker my age; his name was Étienne O’Leary. He died a while ago, but was well-known. The Pompidou recently showed a retrospective of his experimental films.

He was making very abstract movies, influenced by contemporary music, like Karlheinz Stockhausen. I was just filming the streets of Paris and my girlfriend. But when I look at them now—the extracts from the films—they’re very good. I made a little book called 8 Super 8, published by Yale. I wish I could show you the book. It shows how my stills from my movie camera are just like my photographs.

Bernard Plossu, The Return, from ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México (Aperture, 2014) © Bernard Plossu

——-

Paula Kupfer is managing editor of Aperture magazine.

¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México

¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in México$125.00

Add to Cart

The post Bernard Plossu on Movies and Mexico appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 16, 2014

Photography at London’s Frieze Art Fairs

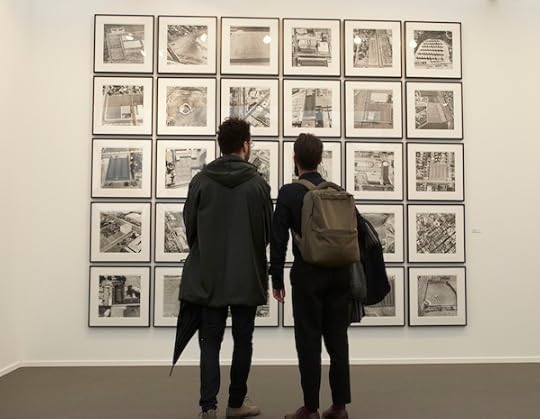

Ed Ruscha, Parking Lots, 1967–1999, on view at Bruce Silverstein Gallery.

Courtesy Stephen Wells/Frieze (Photograph by Stephen Wells)

Frieze London and Frieze Masters opened yesterday in London, with nearly three hundred booths spread out between two respective tents in stately Regent’s Park: the former focused on contemporary art, the latter on works ancient to modern. Large-scale photography dominated many booths, from Thomas Struth’s monumental scenes of museum gallery-goers to Andreas Gursky’s Superman diptych SHII (2014) at White Cube, or Anne Hardy’s sparkling, nearly abstracted installation scenes at Maureen Paley.

Installation by Anne Hardy, on view at Maureen Paley. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Other photographs popular among fair booths were portraits by Wolfgang Tillmans, including a large portrait of his former partner Isa Genzken, and still lifes and portraits by Christopher Williams, coming off the international attention given to his current MoMA retrospective.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Haircut, 2007. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

A Wolfgang Tillmans portrait of Isa Genzken at Galerie Daniel Buchholz (Photograph by Alexandra Pechman)

Christopher Williams, Mustafa Kinte (Gambia), Shirt: Van Laak Shirt Kent 64 41061 Mönchengladbach, Germany Dirk Schaper Studio, Berlin, July 20, 2007, 2008. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Stylish, kitschy booths characterized this year’s edition: there was a faux collector’s living room at Helly Nahmad, while Salon 94’s booth was lemon-yellow and painted with smiley faces. A number of photo-works also acted as framing devices to differentiate the standard makeshift spaces—the set design technique used to grab the attention of over-traveled fairgoers has almost become an art form in itself. Esther Schipper Gallery, from Berlin, bedecked one side of their booth in floral wallpaper photographed by Thomas Demand, whose work was also on display at Sprüth Magers.

Thomas Demand, Hanami, 2014 (wall). Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin (Photograph by Andrea Rossetti)

Thomas Demand, Stove, 2014. (c) Thomas Demand, courtesy Sprüth Magers, London and Berlin

At Kate MacGarry, a black-and-white Goshka Macuga living room served as a backdrop while gallerists sat on lucite chairs shaped like her portrait subjects, as if populating the frame. Galleries with a strong roster of photographers such as New York’s 303 Gallery and Berlin’s Wien Lukatsch Gallery devoted most of their wall space to photo-works, from Jane and Louise Wilson to Stephen Shore to Florian Maier-Aichen.

Goshka Macuga works on view at Kate McGarry Gallery. Courtesy Stephen Wells/Frieze (Photograph by Stephen Wells)

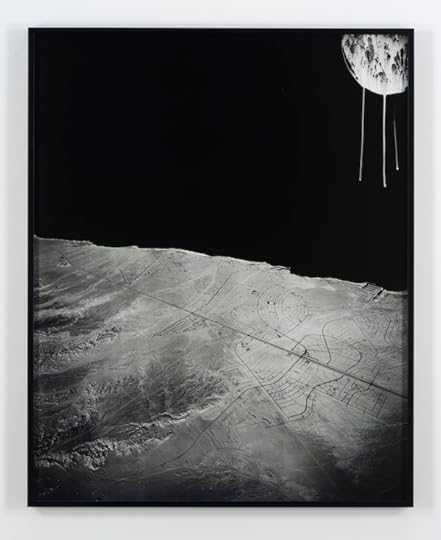

Florian Maier-Aichen, Halbes Bild, 2014. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

Frieze Masters offered a historic look at the last century of photography: legs captured by Herb Ritts, a Man Ray bust, and Sally Mann were all on display at Edwynn Houk Gallery, while Sprüth Magers, for their Masters booth, highlighted multiple of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s solemn series of facades. Skartstedt showed untitled film stills by Cindy Sherman from 1980.

Bernd and Hilla Becher, from the Industrial Facades series, 1970-1996, on view at Sprüth Magers (Photograph by Alexandra Pechman)

Installation view: Work by Cindy Sherman at Skarstedt at Frieze Masters, 15 – 19 October 2014. © Cindy Sherman. Courtesy the artist and Skarstedt.

Cheim & Read dedicated their entire booth to William Eggleston’s “Troubled Waters” portfolio. In the fifteen dye-transfer prints taken in 1980, his subjects range from a dog hazily captured mid-stride to a brown-gold slice of field. But perhaps most attention-grabbing was the apt Freezer: on a frosty blue ledge, banal pastel foods look almost gemlike in their overflowing piles.

William Eggleston , Freezer, 1980, from the series “Troubled Waters” © Eggleston Artistic Trust and courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

The post Photography at London’s Frieze Art Fairs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 15, 2014

Joachim Schmid Artist Talk (Video)

On September 30, 2014, Aperture Foundation, in collaboration with the Department of Photography at Parsons The New School for Design, presented a talk with artist Joachim Schmid. For decades Schmid has appropriated thousands of photographs, discovering new meanings in the currents of digital photography. For series such as Archiv (1986–99) and Estrelas amadas (2013), Schmid sourced imagery from the public sphere, using flea markets and Flickr as tools to understand trends in contemporary photography, including our fascination with constantly redocumenting the same occurrences in the same way. Schmid’s collection highlights the rapid image economy that is characteristic of the digital age, providing a real-time glimpse of culture at large.

The post Joachim Schmid Artist Talk (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 9, 2014

Jeff Liao in Coversation With Sean Corcoran (Video)

On Monday, September 29, Sean Corcoran curator of prints and photographs at the Museum of the City of New York joined Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao for a discussion of Liao’s new book, Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York. Over the past ten years, Liao has crafted exhilarating panoramas of New York City with painstaking care and technological precision. Shooting primarily with a large-format film camera, then scanning and digitally editing the negatives, he creates enormous, detail-driven panoramas of the social and urban landscape of the city.

Assembled Realities, an exhibition of Liao’s work curated by Corcoran, opens October 15, 2014.

Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York

Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao: New York $95.00

Add to Cart

The post Jeff Liao in Coversation With Sean Corcoran (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers