Aperture's Blog, page 171

November 13, 2014

Paris Views: Gail Albert Halaban (Video)

On October 29, 2014, we joined artist Gail Albert Halaban for a conversation with Amy Adler, Emily Kempin Professor of Law at the NYU School of Law, about Halaban’s new book, Paris Views. The two discussed the conventions and tensions of urban lifestyles, the blurring between reality and fantasy, feelings of isolation in the city, and intimacies of home and daily life in Halaban’s work. A continuation of Halaban’s 2012 series Out My Window, her new series Paris Views shifts her focus from New York to Paris and features cinematic atmospheres and intimate domestic stills taken through the windows of her neighbors and others in the community.

Gail Albert Halaban: Paris Views

Gail Albert Halaban: Paris Views $79.95

Add to Cart

The post Paris Views: Gail Albert Halaban (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 12, 2014

Vicki Goldberg: More History in Russian Photographs

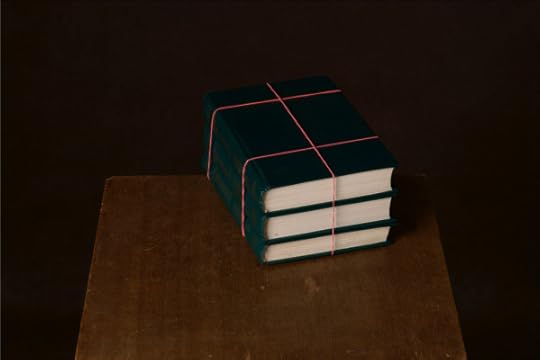

Vadim Gushchin, "Colored Envelopes #3," 2010. Courtesy ClampArt, New York City.

Vadim Gushchin, 'Circle of Reading #1,' 2010. Courtesy ClampArt, New York City.

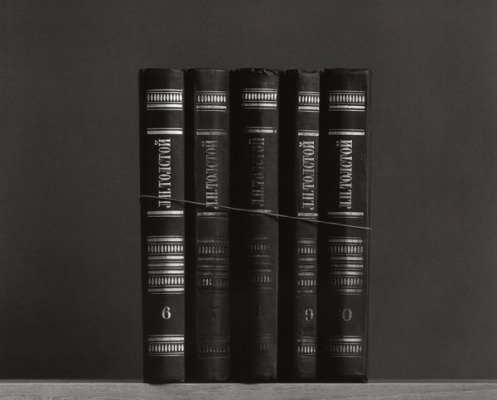

Vadim Gushchin, 'Library #1,' 2000. Courtesy ClampArt, New York City.

Vadim Gushchin, 'Circle of Reading #14,' 2010. Courtesy ClampArt, New York City.

![windows1991[10]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![windows1991[10]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875008.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Windows,' 1991. Courtesy the artist.

![windows1994[10]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![windows1994[10]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875009.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Windows,' 1994. Courtesy the artist.

![slow series 1984[12]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![slow series 1984[12]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875010.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Slow Series,' 1984. Courtesy the artist.

![fast series 1994[7]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![fast series 1994[7]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875011.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Fast Series,' 1994. Courtesy the artist.

![fast series 1990[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![fast series 1990[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875012.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Fast Series,' 1990. Courtesy the artist.

![slow series1990[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![slow series1990[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1416001232i/11875013.jpg)

Nikolai Kulebyaki, 'Slow Series,' 1990. Courtesy the artist.

In 2013, writer Vicki Goldberg traveled to Russia and Ukraine, where she examined postwar and contemporary visual imagery that illuminates life under and after communism. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we publish Goldberg’s three-part diary, which looks to photography from the Soviet era and today. In part three, Goldberg assesses the contemporary work of Vadim Guschchin and Nikolai Kulebyakin.

Part 3: More History in Russian Photographs

Russian art photographer Vadim Gushchin, who combines minimalist, conceptualist, and abstract strategies, is also entwined with two crucial aspects of Russian art that are inseparable from the nation’s identity and history. (He is widely exhibited internationally and since summer 2013 has been shown twice in Moscow, once in Vienna, and once in Paris.) He photographs the most mundane objects from his (and our) daily life, each in series: books, envelopes, pills, packages, bread. Photographers from Stephen Shore to Gabriel Orozco have also photographed the least imposing elements in our homes— a plate, a pail, a table mat— but Gushchin manages to transpose the globally recognizable, inconsequential, disposable fragments of life into pristine artifacts of art, more beautiful in their spare perfection than reproductions of his work suggest.

A wrapped package, a red business card holder, an envelope, or a single pill is isolated and centered on a table. (He likes envelopes because they tell signify important events: births, weddings, deaths, even in this age of email.)

Seen from above, an envelope or package on a table are flattened into abstract shapes; the table tilts up and runs into the featureless dark ground like a table in a Cézanne still life: a mere three colors, minutely scrutinized and arranged, a single rectangle, sometimes cut off by the frame and maneuvered into different geometries: we are in Malevich territory here, with objects destined for wastebaskets converted to Constructivism, a heroic movement in Russian and indeed in twentieth century art. Gushchin says that it is impossible to invent new forms of art: “The language has been invented. The question is, what do you want to say?”

For fifteen years he photographed only in black and white. In a series of photographs of the white pyramids and spheres used to teach student artists how to draw three-dimensional objects, Guschin pointed out the marks left by handling, which encode a kind of history of the objects. The last of the black and whites was a series of different water glasses, the light choreographing complex patterns within them, each one topped with a different kind of bread. A Russian would understand it at a level of personal and national history: at a Russian wake, family and friends gather to drink wine and eat bread, leaving one empty glass and piece of bread for the dead. Gushchin combined particular glasses with breads of different shapes in an attempt to create the impression of particular people. “Thus,” he told me, “an imaginary portrait gallery of the dead appeared.”

In color, his subjects are frequently red, a color associated not only with Malevich but even more often with icons as it is associated with blood. What’s more, the artist says, the word ‘red’ in Russian is very close to the word for beauty. In a photograph of several plastic jar tops in a row, Gushchin points out a gold metal jar top as another reference: the gold backgrounds of icons refer to the constant splendor of light in heaven. Several of the wrapped packages he photographs are bound with rubber bands, to make a cross. This is a more humble reference to religion than even the current Pope’s automobile: a cross made of rubber bands that have never been blessed, holding together a package that, who knows? may be contaminated with atheism. Can such pedestrian objects assume the mantel of faith? Gushchin says that being Russian, he has to reflect Russia, a country with a long history of fervent belief that persisted even while the Soviets killed millions for their beliefs.

During the summer of 2013 the Glaz (Eye) Gallery in Moscow had an exhibition of work by Nikolai Kulebyakin, another photographer widely known internationally. There were arresting, sometimes counterintuitive, even inexplicable color photographs of the outdoors, made with exposures as long as an entire night and into the day with unpredictable results. Color shifted and light misbehaved as the world turned and the lens lingered.

A larger selection of black- and- white prints offered a dazzlingly, endlessly complex set of still lifes of overlapping glass sheets and objects, some of them broken, plus mirrors, layer upon layer, with light improbably sifting through or ricocheting off unlikely surfaces. These images were tantalizing puzzles with no reasonable solutions – what was in front of what and what behind? What was seen through glass? What was reflected, and what was not? Both series were about photography, seeing, perception, and the limits of all three.

Kulebyakin too has jousted with history, even personal history, on occasion. A series called “Reproduction of Archive” consists of snapshots of children, family groups, a man with a dog, and so on, in diptychs with negative and positive on adjacent halves. The series comments on photography again and the retrieval of family history, the creation and reinforcement of memory through reprinted negatives, a slippery matter: does anyone remember the dog’s name after all these years? Can anyone identify the child in that damaged photograph?

Forget history for the moment or leave it to the future to construct – Kulebyakin’s black-and-white portraits are as individual as, well, the individuals, and take a fresh and powerful look at an age-old genre. The sitters maintain strong identities while negatives of slightly different portraits of themselves are thrown upon the background in rectangles that are somewhat distorted and askew. Something is usually aslant– a trapezoid of light. a wall, or a pane of glass– and strong lights, shadows, and bits of negative portraits of themselves fall over faces, shirts, lightly patterned backgrounds. The result is a partly modernist, partly cubist shifting pattern of lights, darks, and negative reversals, and yet the sitter’s image triumphs over all. A psychic insight is implied: that another self exists, perhaps an inner self, possibly inverse or darker, or just differently perceived by a spectator – or by a photographer. At the same time, these images emphasize the reproducible nature of photography and make visible the ordinary studio procedure of taking more than one portrait of a sitter. They deploy the extraordinary potentials of light in a medium that owes its existence to it.

Possibly somewhere in the vast repository of current work there is some that will make history and last within it, but history can be fickle and elusive. None of us knows what art (original or not), what records, or even what inventions will be preserved in the notebook that time keeps on file until someone opens the file drawer, realizes that something of value is inside and opens it to the present, restoring it to memory– or perhaps to the history of photography.

Vicki Goldberg is a writer on photography and author of the Aperture book Light Matters.

The post Vicki Goldberg: More History in Russian Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 11, 2014

What’s in a Name? By David Campany

This article originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review 007.

The term “photobook” is very recent. It hardly appears in writings and discussions before the twenty-first century. This is surprising, given that some of the various kinds of objects it purports to designate have been around since the 1840s. It seems that makers and audiences of photographic books did not require the term to exist; indeed, they might have benefitted from its absence. Perhaps photographic bookmaking was so rich and varied precisely because it was not conceptualized as a practice with a unified name. So does the advent of the term “photobook” mark some kind of change?

There was little serious writing on the subject of photographically illustrated books throughout what was arguably the most important period for the form: 1920 to 1970. In that half century, when so many remarkable and important books were published, barely a single intelligent essay was written about them. For example, August Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of Our Time, 1929) and Atget: Photographe de Paris (1930) received almost no critical attention, beyond a few lines from Walter Benjamin and Walker Evans. Today they are among the most discussed. Even Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958/9) attracted little serious commentary when it first appeared (although there were plenty of ranting column inches, for and against).

For all the sophistication of the photographs, design, editing, and printing techniques, and for all the nuanced grasp of how a book of photographs might contribute to its cultural moment or become a complex document, something seemed to elude critics and commentators. It seems as if it was only once photographically illustrated printed matter had begun to be eclipsed by television, video, and, later, the Internet that it could come under close scrutiny. In 1998 the American scholar Carol Armstrong published Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843–1875. It is a remarkable reflection on the very early interplay of photography, writing, and the printed page. Armstrong’s discussion of books by Anna Atkins, William Henry Fox Talbot, Julia Margaret Cameron, and others is very illuminating, and her way of seeing that distant but vital moment through the prism of more recent critical theory is ambitious. Upon reading it, I felt convinced it was going to be the book to open a new field of study—but it didn’t. Maybe it was still too early. It never got out of its expensive hardcover and has now slipped out of print.

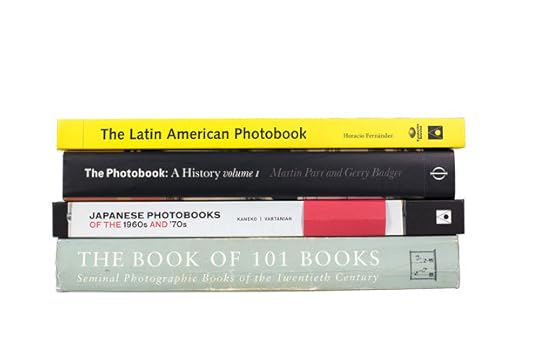

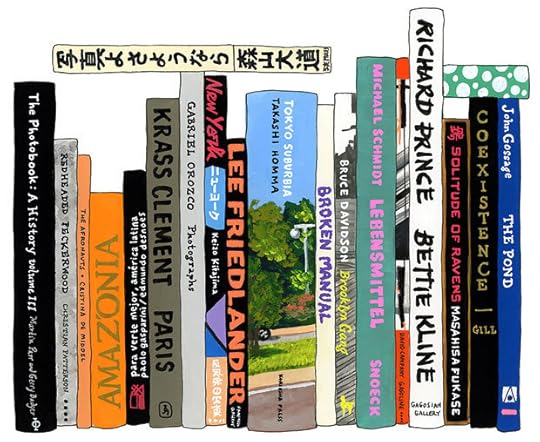

By contrast, the dominant form for books about photographic books follows the template set in 2001 by Andrew Roth’s The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century, and consolidated by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s three volumes of The Photobook: A History (2004–14). These densely illustrated anthologies introduce a range of titles, establish some kind of canon, and function as guides for collectors, connoisseurs, and curators. There have been more than a dozen published in this vein, most often taking a national or regional theme: Dutch books, Japanese books, Latin American, German, and so on. These anthologies are invaluable because the area of study is still so new and there’s still much to discover, but they also frustrate because the writing on each entry is usually short. Swiss Photobooks from 1927 to the Present (2011) is a welcome exception, with more sustained essays about the context, production, and reception of each book included.

Generally the more serious scholarship is scattered and a little harder to spot, but it is there. The Photobook: From Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond (edited by Patrizia Di Bello, Colette Wilson, and Shamoon Zamir, 2012) emerged from the regular meetings of a bunch of UK academics, myself included. The meetings didn’t really cohere and neither does this collection of papers, but maybe that doesn’t matter—if the writing of one of the various thinkers is of interest to you, it’s not difficult to track down more of what they’ve been up to. For example, Caroline Blinder writes extensively on the intersection of photography and literature in the U.S.; Ian Walker’s books on Surrealism are attentive to image/text interplay; and the reliably provocative David Evans writes on everything from photomontage and Situationism to Jean-Luc Godard and Wolfgang Tillmans, always with an interest in photo editing. I look forward to his forthcoming book 1+1, a primer on the history of editing.

This brings me to what I think has been the real stumbling block for sustained discussion of photographic books: a critical framework for thinking about editing has never really taken hold. How do we articulate the endlessly varied ways in which one image affects another, and another? In the 1920s, filmmakers and film theorists worked up sophisticated, even revolutionary, theories of cinematic editing. Think of the Soviet situation, with the intensity of the ideas of Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein, and Dziga Vertov. Given the expansion of the popular press and the extraordinary experiments with the book form around that time, one might have expected an equally sophisticated discourse around the editing of photographs. But beyond pockets of debate about photomontage and collage, there really wasn’t any. Even the great image editors of the last century, from Stefan Lorant and André Malraux to Franz Roh and Robert Delpire, have spoken little and written less about how they actually operated.

Nevertheless, editing is ubiquitous. For over a century nearly all photographic culture—from mainstream magazine photo-essays to independent books and website presentations—has involved the ordering of bodies of images. “Composition” is not confined to the rectangle of the viewfinder; it is also a matter of the composition of the set, series, suite, typology, archive, album, sequence, slideshow, story, and so forth. So are we to presume editing and its effects upon us are simply ineffable, beyond language, pursued entirely intuitively? Is editing a poetic practice that is not to be thought about too hard? Do we not discuss editing because it’s a painful truth that the majority of photographers are lousy editors of their own work? Many a landmark photographic book has resulted from collaboration between photographer and editor. This complicates the presumption of the singular authorial voice that still dominates discussion of photographic books.

In this light, Blake Stimson’s The Pivot of the World: Photography and its Nation (2006) is a significant study, with its sustained chapters on Frank’s The Americans, The Family of Man book and exhibition (1955), and the serial studies of industrial architecture made by Bernd and Hilla Becher. Stimson’s central contention is, “The photographic essay was born of the promise of another kind of truth from that given by the individual photograph or image on its own, a truth available only in the interstices between pictures, in the movement from one picture to the next.” From this, he develops a nuanced argument in which photographic meaning is as much about gaps and the unrepresentable as it is about what can be revealed or expressed visually. It is refreshing to see this idea articulated and thought through. At its core it’s not a wildly original insight—anyone who has ever sequenced photographs will at least intuit what Stimson is getting at—but this might be precisely why his book is starting to have an influence. Sarah E. James’s Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures across the Iron Curtain (2013), which emerged from her doctoral research, is a good example of this; her debt to Stimson is clear in her close attention to ways in which poetics and politics are inseparable in the making and reading of image sequences.

It might still be early days for the discipline, but is discipline what is needed? I know you can’t unring a bell but I rather miss those days before the dubious term “photobook” became so widespread. It’s not an innocent word. It has been welcomed and taken up in order to impose some kind of unity where there simply was none and perhaps should be none. A few years ago I wrote this in the British magazine Source: “The compound noun ‘photobook’ is a nifty little invention, designed to turn an infinite field (books with photographs in them) into something much more definable. What chancer would dare try to coin the term ‘wordbook’ to make something coherent of all books with words in them? But here we are. A field needs a name and until we find a better one we’re stuck with ‘photobook.’”

The emergence of the term and the institutionalization of a field of study does signal a change, and nobody who has witnessed the boom in interest in the last decade could fail to ask themselves, “Why ‘photobooks’ now?” I don’t think the term signals an end. New media don’t replace old ones but they do redefine them. The take-up of the term “photobook” is a consequence of the Internet, and so is the field it marks. Compared to the wild hall of mirrors that is the photograph online, the photobook—for all its various forms—is at least a fixed and relatively tame object of study.

_____

David Campany is one of the best-known and most accessible writers on photography. His books include Walker Evans: The Magazine Work (2013), Jeff Wall: Picture for Women (2011), Photography and Cinema (2008), and Art and Photography (2003). He is also the author of The Open Road (Aperture, 2014). davidcampany.com

The post appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 10, 2014

Video: The PhotoBook Awards 2014 Short List

With this week’s opening of Paris Photo, we’re highlighting the titles included in the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards 2014 Short List.

Stay tuned for the final announcement of the winners of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards on Friday, November 14, at 1:00 p.m. at Paris Photo and on the PhotoBook Awards website. In the meantime, take a closer look at the outstanding publications competing for the Photography Catalogue of the Year, First PhotoBook, and PhotoBook of the Year prizes.

The post Video: The PhotoBook Awards 2014 Short List appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Editor’s Note: Ramón Reverté

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #751: Ramón Reverté

I confess: the more I know about the photobook market, the less I understand it. It is widely believed that the photobook community is growing—and in fact, one often hears this moment described as a “golden age”—but if you ask publishers whether they are seeing a corresponding growth in sales, many will tell you no. Sales have plateaued or are declining, and it is increasingly easy to find good books with print runs of just a few hundred copies. My guess is that the market is maturing and growing, but the sheer volume of published books has outstripped the appetite for them.

All this notwithstanding, great books do sell, and sell very well indeed, if the formula is just right. The combination of photography, new book printing technologies, and—that catalyzing ingredient—the Internet has proved to be a potent cocktail for the dissemination of photobooks and information about them. More people appear to be collecting books, albeit from a more informed perspective and in a less voracious, compulsory way. The broader recognition of the photobook as a work of art (finally) has created new rules and increased interest in buying books not just for the pleasure of owning them, but because of their monetary value.

In the midst of this interesting moment, this issue of The Photobook Review focuses on the explosion of events that have grown up around the photobook: the fairs, festivals, workshops, contests, and clubs. As a Mexican publisher based in Barcelona who spends roughly half the year working out of Mexico City, I also wanted to address the recent exciting revolution in photobooks being produced in Latin America and, especially, Spain.

Many consider this extraordinary period of creativity in Spanish photobooks to have begun in 2011, with the release of Ricardo Cases’s remarkable book Paloma al aire. Other great examples had emerged previously, but Paloma al aire appeared at the right moment, when many things were converging in Spain: a hungry, young generation of photographers; new photography schools outside of the traditional academy, notably Madrid’s Blank Paper; independent publishers such as Phree, Ca L’Isidret, Bside Books, Standard Books, and Ediciones Anómalas; specialized booksellers doubling as publishers, such as Dalpine, Kowasa, and Ivorypress; photobook collectives such as NoPhoto; blogs such as 30y3.com and cienojetes.com; talented designers such as Eloi Gimeno, N2, and Astrid Stavro; active photobook meet-ups and clubs; and, perhaps most important, the exhibition space and publisher La Kursala.

We have invited some of the protagonists of the Spanish boom to write for this issue, and Cristina de Middel created the centerfold: the bombastic Photobook Boulevard, an homage to various now-iconic photobooks, using the cover of The Great Unreal by Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs as a template.

I would like to thank all the writers and reviewers for their collaboration. It is my hope that this issue will help broaden our shared understanding of this amazing field.

_____

Ramón Reverté is the editor-in-chief and creative director of Editorial RM, a publishing house based in Mexico and Spain. He is also a voracious book collector, the cofounder of the Concurso Fotolibro Iberoamericano, and the publisher of The Latin American Photobook (Editorial RM/Aperture/Images en Manoeuvres/Cosac Naify, 2011) and Photobooks: Spain 1905–1977 (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía/Acción Cultural Española/Editorial RM, 2014). editorialrm.com

Jane Mount (illustration) published The Ideal Bookshelf, a collection of the favorite books of one hundred creative thinkers, with Little, Brown in 2012. More of her work can be seen at idealbookshelf.com

The post Editor’s Note: Ramón Reverté appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin

Dear Photobook Review reader,

Over the past three years that The PhotoBook Review has been in publication, it has become apparent that the ecosystem of the photobook is no longer exclusively concerned with simply publishing books. A whole network of additional activities has sprung up around that core act, with prizes awarded and festivals held practically every month, from Indonesia to Vienna; the de rigueur publication of “books about books” from any country with a respectable publication record; exhibition treatises about single photobooks or regional surveys; and, finally, the move to create a PhotoBook Museum (or at least, as founder Markus Schaden says, a first draft or “dummy” of what such a museum might look like).

If we were to take a snapshot of these activities and provide a representative sampling of the world of the photobook, above and beyond the actual making of books, who and what would be represented? How and for how long can this spate of activities—what I’d like to affectionately term “the PhotoBook Circus”—be additive to our understanding of the power and meaning of photography itself? In pursuit of insight, I turned to Ramón Reverté, a fellow publisher and enabler in the growth of photobook activities, to select a range of contributors who would assemble a series of “Reports from the Field.” Our goal was to help record the range of activities happening around the photobook today—the better to gain a sense of their repercussions and the motivations behind them.

Not coincidentally, this issue turns a spotlight on Spain’s recently energized photobook scene. This focus highlights not only the output of contemporary Spanish photographers, but also what could be seen as a case study, in which activities centered around the photobook help transform and invigorate photographic communities outside of traditional cultural centers, with directly participatory and highly networked means of both creating new work and communicating it outward via the photobook.

I’m also delighted to include the short-listed titles from the 2014 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. Paris Photo, with its strengthened commitment to the photobook under the guidance of director Julien Frydman, serves as another example of the way in which the conversation has expanded to acknowledge the photobook as an essential part of photography. This year, the Awards include a new category: Photography Catalogue of the Year. Thank you to the more than eight hundred entrants overall! Finally, I’d also like to thank Ramón for being this issue’s editor, and, as always, all the participants who have let us harvest a few of their thoughts and ideas—a smorgasbord of photobook delights.

—Lesley A. Martin

Publisher, The PhotoBook Review and Aperture Foundation book program

The post Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 7, 2014

The Air for All: An Introduction to The Drone Primer

![Halemaʻumaʻu crater, 2013[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486453i/11798248._SX540_.png)

![Halemaʻumaʻu crater, 2013[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486453i/11798248._SX540_.png)

Tushev Aerials, 'Halemaʻumaʻu crater,' 2013. Courtesy Center for the Study of the Drone.

Tushev Aerials, 'Cape Canaveral,' 2013. Courtesy Center for the Study of the Drone.

![Brooklyn, Queens by Night, 2014[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Brooklyn, Queens by Night, 2014[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486453i/11798250._SX540_.png)

Tushev Aerials, 'Brooklyn, Queens by Night,' 2014. Courtesy Center for the Study of the Drone.

Tushev Aerials, 'Cape May,' 2013. Courtesy Center for the Study of the Drone.

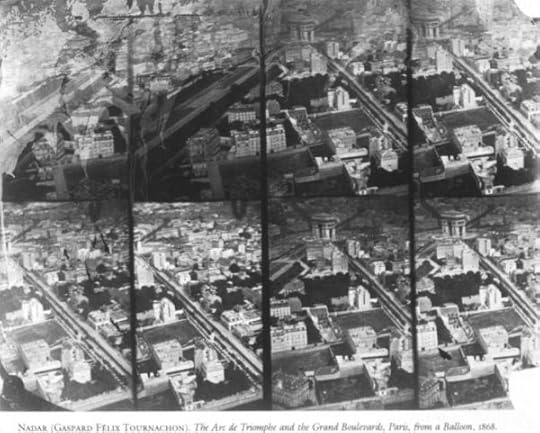

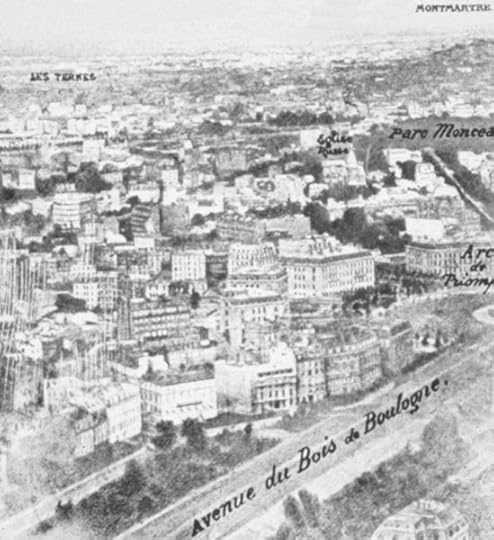

Undated aerial photographs of Paris, taken by Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon).

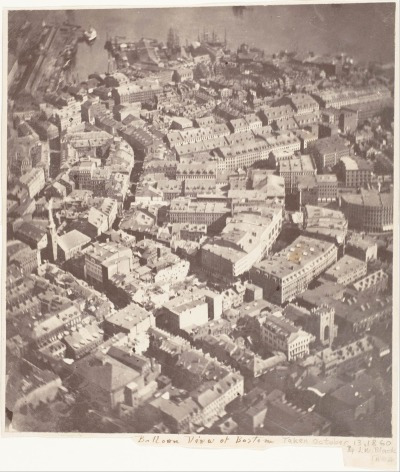

The single surviving photograph of Boston from James Black’s balloon flight in 1860.

One of the first aerial photos of Paris, taken in 1868 by Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon).

The Center for the Study of the Drone introduces its compendium The Drone Primer this weekend, with a launch event on Saturday at Wendy’s Subway, 722 Metropolitan, Brooklyn, starting at 8pm. The launch will feature a multimedia aerial installation by the drone-flying art duo Tushev Aerials, featured in the slideshow above. Below, an excerpt from the chapter “The Air for All,” featured in the book.

The first aerial photograph was made in 1858 by the artist and critic Nadar, who used a balloon of his own invention to fly eighty meters above the French village of Petit-Becetre. Nadar’s artistic and somewhat bohemian leanings belied a more utilitarian motive: three years earlier, he had patented the idea of photographic mapping, and the following year he was proposing to take photographs for the French Army during its campaign in Italy. Flying with a camera wasn’t easy (Nadar had to install a miniature darkroom in the balloon basket) and it wasn’t always safe (his second flight ended in a landing that dragged him and his wife for a kilometer). But he was on to something. By the First World War, the cultural theorist Paul Virilio wrote, aviation had ceased to be about breaking flight records and had become an essential, a determinant aspect of modernity and “one way, or perhaps even the ultimate way, of seeing.”

The price point for that way of seeing has dropped dramatically in the past few years. The continued development of the components that go inside smartphones—sensors, optics, batteries, and embedded processors—has brought the cost of an able quadcopter with a camera and a thirty-minute battery life down to roughly $700, within reach of many gadgeteers and amateurs. The FAA has predicted that by 2018, around 7,500 drones will fly over the U.S., and that’s not counting many smaller, lower-flying consumer systems. Just as the computer giants vied to put a computer in everyone’s pocket, some upstart drone companies dream of putting a drone joystick in everyone’s hand. “We are entering the drone age,” declared Chris Anderson in 2012, as he left his job editing Wired to run 3D Robotics, a drone kit company, and DIY Drones, an associated website where drone hobbyists share mostly open-source designs. The site has over 30,000 members. Now armed with small cameras and GPS navigation systems, homemade and commercially-available remote aircraft are used as affordable tools for filmmaking, farming, environmental sensing, wilderness patrol, and searching for missing people. They have been used by realtors to make dramatic videos of homes, and by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to take epic video selfies. “Our goal is to put flying robots in the hands of as many people as possible,” Tim Reuter, a drone hobbyist and one of the founders of AirDroids, one of many drone startups based in San Diego, told TechCrunch in January. (In a Kickstarter campaign, the company raised over $50,000 overnight.) “We think it’s empowering to democratize the sky,” he added.

The drone raises the stakes in the tension between information and privacy. When Google’s Street View cars were found to be collecting massive amounts of data in Germany without proper authorization, they became a symbol of the massive and otherwise invisible network of sensors that spans from the street corner to our inboxes. And yet these cars—someday, per Google’s driverless dream, bound to be drones themselves—bring us value: they allow anyone to view the streets like a kind of drone pilot. Google’s satellite maps, meanwhile, have done for the Earth what Google’s web crawlers did for the Internet. They allow us to scan the Earth on a map that is, per Jorge Luis Borges’ famous short story “On Exactitude in Science,” as large as the world itself. (The U.S. government, with its satellites, can have something like a real-time version of this map.) In 2012, the artist James Bridle underscored the drone-like power of Google with Dronestagram [featured in Aperture's "Documentary Expanded" issue], bird’s-eye-view photos of the locations of drone strikes taken from Google Maps and tinted like a scenic cell phone selfie. It contemplated two sides of the drone, bringing the people closer to a way of seeing typically reserved by the state.

The Drone Primer is available for free download.

The post The Air for All:

An Introduction to The Drone Primer appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture at Paris Photo, Nov. 13 to 16

Visit Aperture Foundation at Paris Photo, the leading international fair dedicated to photography. Throughout the weekend, join us for book signings and the announcement of the winners of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, on Friday, November 14, at 1:00 p.m. Limited editions by Erwin Olaf, LaToya Ruby Frazier, An-My Lê, and Pieter Hugo will be available.

For ticketing information, visit parisphoto.com.

Book Signings

Thursday, November 13

3:30 p.m.: Larry Towell

Friday, November 14

1:30 p.m.: Alex Majoli and Paolo Pellegrin

2:00 p.m.: Erwin Olaf

3:30 p.m.: Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb

4:30 p.m.: The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip, with David Campany, Todd Hido, Joel Meyerowitz, and Bernard Plossu

6:30 p.m.: Pieter Hugo: launch of Kin in a slipcased edition—available exclusively through Aperture, in advance of the trade edition available in spring 2015

Saturday, November 15

2:30 p.m.: Reinier Gerritsen

3:30 p.m.: Richard Misrach

5:30 p.m.: Penelope Umbrico: launch of RANGE

Sunday, November 16

2:30 p.m.: Joel Meyerowitz

3:30 p.m.: Robin Schwartz

The post Aperture at Paris Photo, Nov. 13 to 16 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 6, 2014

Vicki Goldberg: Contemporary Ukrainian Photography

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_4[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_4[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798258._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_3[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_3[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798259._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_2[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_2[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798260._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_5[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_5[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798261._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012. All photographs courtesy Shilo-Group.

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_4[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_4[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798262._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_3[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_3[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798263._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

In 2013, writer Vicki Goldberg traveled to Russia and Ukraine, where she examined postwar and contemporary visual imagery that illuminates life under and after communism. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we publish Goldberg’s three-part diary, which looks to photography from the Soviet era and today. In part two, Goldberg considers the work of Ukrainian photography collective Shilo-Group.

Part 2: History in Contemporary Ukranian Photography

Like human beings, contemporary art most often retains hints of its heritage whether it means to or not, sometimes even by maneuvering to disown it, which is one form of acknowledgement. In any case, it cannot help being part of the time it is embedded in. Past and present have met head on in the work of the Shilo-Group, gounded in 2010 by three young men from Kharkiv in Ukraine: Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, Sergiy Lebedynskyy, and Vadym Trykoz. Having nothing on display in galleries or museums when I was there, they showed me several bodies of work, including a dummy of a book they hoped to publish. (Since then, Krasnoshchok and Lebedynskyy’s Euromaidan has been shortlisted for the Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.) In November of 2013, the group had a show in Moscow. As a group they are unusual: all self taught photographers, they live in three different countries and only photograph together several times a year, and all three have different professions: Krasnoshchok is a maxillofacial surgeon in Kharkiv, Lebednyskyy is finishing a PhD in particle technology in Germany, and Trykoz is an adhesive engineer in Austria. (I was told that this kind of cross-country art collaboration is relatively common in Eastern Europe, most commonly when people who are citizens of different nations work together) The Shilo-Group shares ideas about photography and, evidently, attitudes to the contemporary life around them. Their individual styles all bear a strong family resemblance to each other.

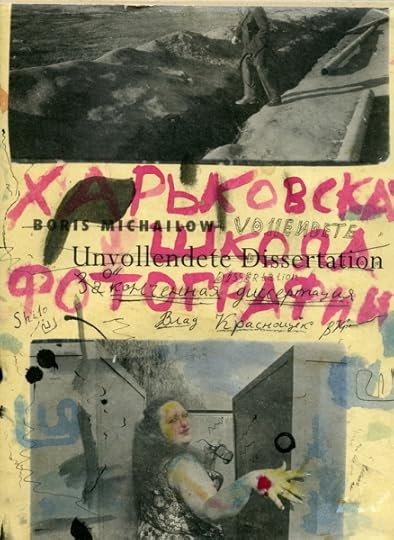

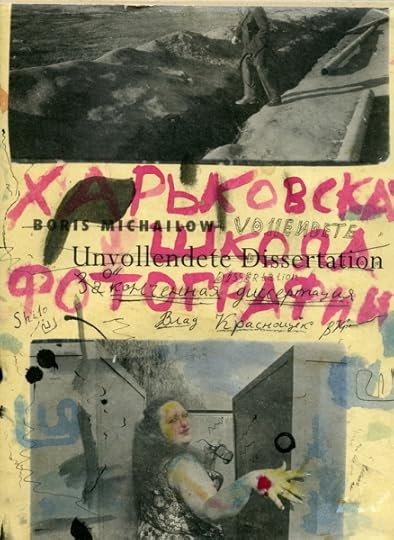

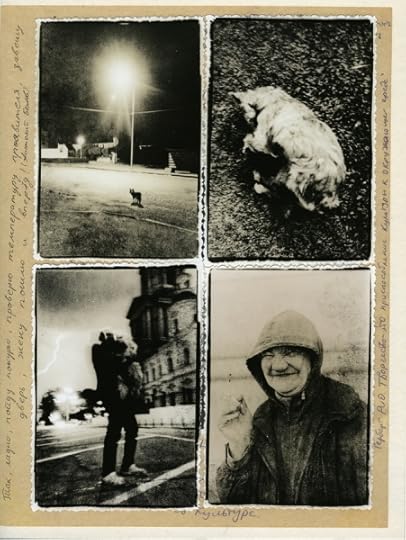

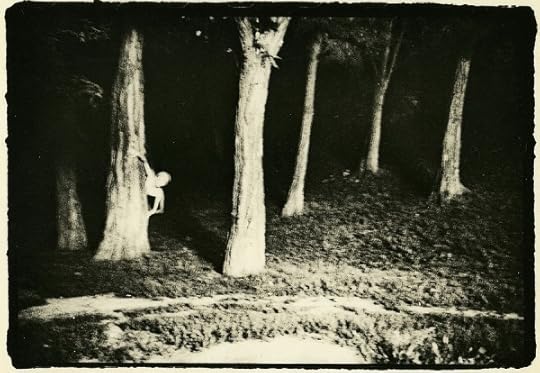

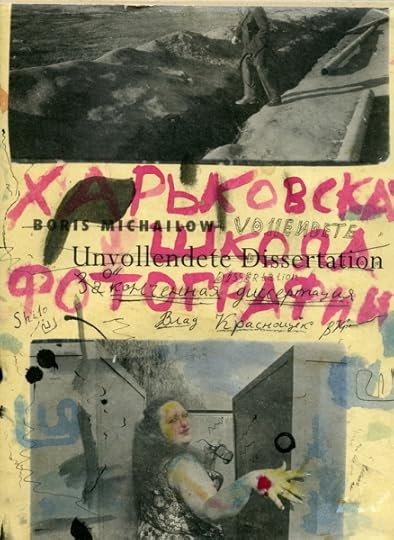

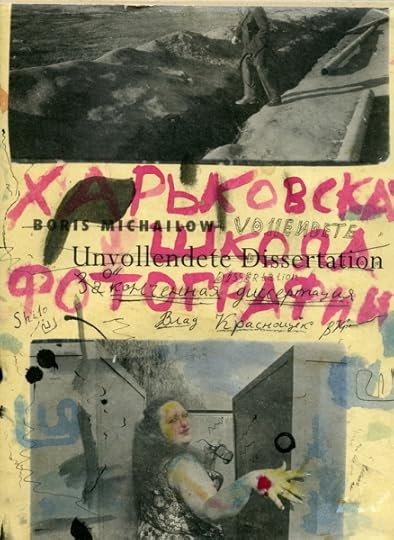

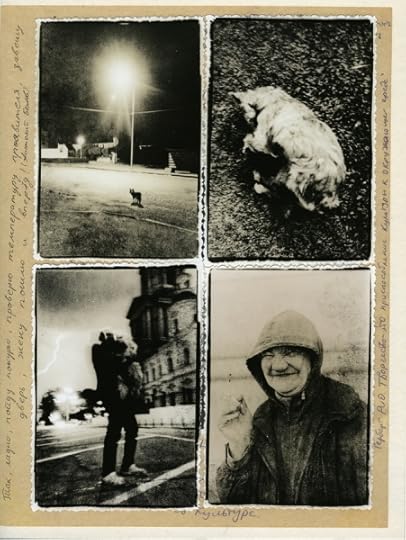

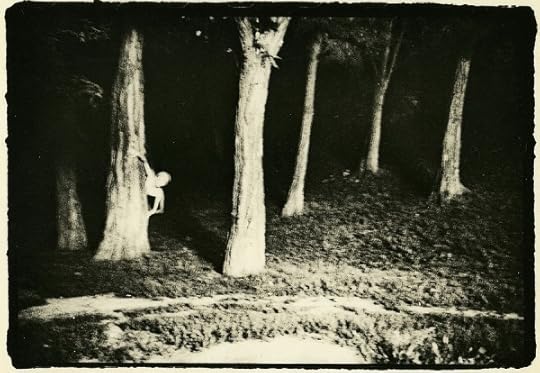

They have previously written that they joined forces when they “felt stuck in a big swamp of played out and constrained local photography environment.” In Kharkiv independent photography began tentatively in the early 1970s, when the first unofficial photo clubs began meeting informally and irregularly. Today the best known of those photographers is Boris Mikhailov, who has continued to photograph a social documentary of life after communism fell, often seeing it at its worst, as in his unblinking pictures of the homeless. In the mid 1980s he made Unfinished Dissertation, a book of his own images glued onto the back of his uncle’s lecture notes, with short handwritten texts on most pages. The Shilo-Group’s book project is called Finished Dissertation: they cut Mikhailov’s pictures out of a published copy of his book, replaced them with their own, and also erased and replaced his texts. This could be seen as appropriation disguised as obliteration, but it is appropriation at a basic structural level: Barbara Kruger’s catalog illustrations have been removed from catalogs and Richard Prince’s Marlborough men from ads, but no matter how transmuted Finished Dissertation is, it remains a book, in fact, still the original book which was itself appropriated from another man’s notes.

The defaced and refaced use of an earlier book is a logical expansion of appropriation. London-based photographers Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin bought 100 copies of the 1998 edition of Berthold Brecht’s War Primer, first published in 1955, and in 2011 issued War Primer 2, their profoundly revised version. Brecht’s book reprinted black-and-white mass-media photographs of World War II; Broomberg and Chanarin superimposed media photographs of the “War on Terror,” in color, over the earlier images. (Their book, which in a new edition won the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize this year, was shown in the New Photography show at MoMA in New York last year.) War Primer 2 not only comments on the earlier publication but also on earlier photojournalism and war photography itself as well as the means of its dissemination. War photography is as continuous as war itself but as variable as circumstances, technologies, and the changing media, a family lineage that is inevitably reshaped by new generations.

The Shilo-Group calls its book a diary of “the creative life of the emergent photographic generation” and of friends and colleagues as well as both a prank and a serious work: “‘Finished Dissertation’ is a play in impudence,” they said. It’s a kind of furtive social documentary at a distance, observed through sunglasses at night and tinged with apprehension and a sense of dislocation that lingers from long after 1989, when so much fell apart and so many left Ukraine. A prank it may be, but one couched in a contemporary idiom that is at once faintly plaintive, quietly melancholy even when it laughs, and consistently, raggedly, expressive. As of today, of course, the constant stream of photographs from Ukraine might make one nostalgic for mere dislocation.

The Shilo-Group’s revisions of Mikhailov could hardly be a more direct reference to their local photographic history, and in their own way the members of the group are as intent on telling the story of their period and place as their Ukrainian forebear. But like inheritors mindful of their family’s success yet determined to make their own mark, they have changed both the approach and the ambience. Their images are black and white, gritty, dark with sudden flares of light, sometimes purposefully outrageous, other times simply off kilter. Their street photography is determinedly half legible, the people anonymous, the streets more atmospheric than descriptive, the message hovering on the edge of ambiguity. They develop by lith printing, a process that invites accidents and unpredictability and is, therefore, not reproducible. No two prints are exactly the same, and the group uses Soviet-era paper, which is hard to find and, inevitably, altered by time.

In the Shilo-Group’s kit bag there are also some painted-over and written-over color photographs and a pointed political fantasy called “Timoshenko’s escape or the first step to the exhibition on Mars.” The escape rewrites the fate of Yuliya Tymoschenko, the imprisoned former prime minister of Ukraine, who was released during this year’s revolution. In this narrative, where a mostly naked woman takes the role of Tymoschenko, she escapes and finds Kharkiv, an old industrial city free of excessive charm, so beautiful she decides to stay. That’s current history seen through Alice’s looking glass – or perhaps a grim fairy tale: as of this writing, Tymoschenko is free, has run for election once more, and lost.

Vicki Goldberg is a writer on photography and author of the Aperture book Light Matters.

The post Vicki Goldberg: Contemporary Ukrainian Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Vicki Goldberg: History in Contemporary Ukrainian Photography

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_4[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_4[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798258._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_3[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_3[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798259._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_2[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Finished Dissertation Shilo_2[5]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798260._SY540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Finished Dissertation", 2011-2013

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_5[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_5[6]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798261._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012. All photographs courtesy Shilo-Group.

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_4[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_4[3]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798262._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_3[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380930019i/3344528.png)

![Shilo_Group_Timoschenko's_Escape_3[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1415486454i/11798263._SX540_.jpg)

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

"Untitled" from series "Timoshenko's escape", 2012

In 2013, writer Vicki Goldberg traveled to Russia and Ukraine, where she examined postwar and contemporary visual imagery that illuminates life under and after communism. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we publish Goldberg’s three-part diary, which looks to photography from the Soviet era and today. In part two, Goldberg considers the work of Ukrainian photography collective Shilo-Group.

Part 2: History in Contemporary Ukranian Photography

Like human beings, contemporary art most often retains hints of its heritage whether it means to or not, sometimes even by maneuvering to disown it, which is one form of acknowledgement. In any case, it cannot help being part of the time it is embedded in. Past and present have met head on in the work of the Shilo-Group, gounded in 2010 by three young men from Kharkiv in Ukraine: Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, Sergiy Lebedynskyy, and Vadym Trykoz. Having nothing on display in galleries or museums when I was there, they showed me several bodies of work, including a dummy of a book they hoped to publish. (Since then, Krasnoshchok and Lebedynskyy’s Euromaidan has been shortlisted for the Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.) In November of 2013, the group had a show in Moscow. As a group they are unusual: all self taught photographers, they live in three different countries and only photograph together several times a year, and all three have different professions: Krasnoshchok is a maxillofacial surgeon in Kharkiv, Lebednyskyy is finishing a PhD in particle technology in Germany, and Trykoz is an adhesive engineer in Austria. (I was told that this kind of cross-country art collaboration is relatively common in Eastern Europe, most commonly when people who are citizens of different nations work together) The Shilo-Group shares ideas about photography and, evidently, attitudes to the contemporary life around them. Their individual styles all bear a strong family resemblance to each other.

They have previously written that they joined forces when they “felt stuck in a big swamp of played out and constrained local photography environment.” In Kharkiv independent photography began tentatively in the early 1970s, when the first unofficial photo clubs began meeting informally and irregularly. Today the best known of those photographers is Boris Mikhailov, who has continued to photograph a social documentary of life after communism fell, often seeing it at its worst, as in his unblinking pictures of the homeless. In the mid 1980s he made Unfinished Dissertation, a book of his own images glued onto the back of his uncle’s lecture notes, with short handwritten texts on most pages. The Shilo-Group’s book project is called Finished Dissertation: they cut Mikhailov’s pictures out of a published copy of his book, replaced them with their own, and also erased and replaced his texts. This could be seen as appropriation disguised as obliteration, but it is appropriation at a basic structural level: Barbara Kruger’s catalog illustrations have been removed from catalogs and Richard Prince’s Marlborough men from ads, but no matter how transmuted Finished Dissertation is, it remains a book, in fact, still the original book which was itself appropriated from another man’s notes.

The defaced and refaced use of an earlier book is a logical expansion of appropriation. London-based photographers Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin bought 100 copies of the 1998 edition of Berthold Brecht’s War Primer, first published in 1955, and in 2011 issued War Primer 2, their profoundly revised version. Brecht’s book reprinted black-and-white mass-media photographs of World War II; Broomberg and Chanarin superimposed media photographs of the “War on Terror,” in color, over the earlier images. (Their book, which in a new edition won the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize this year, was shown in the New Photography show at MoMA in New York last year.) War Primer 2 not only comments on the earlier publication but also on earlier photojournalism and war photography itself as well as the means of its dissemination. War photography is as continuous as war itself but as variable as circumstances, technologies, and the changing media, a family lineage that is inevitably reshaped by new generations.

The Shilo-Group calls its book a diary of “the creative life of the emergent photographic generation” and of friends and colleagues as well as both a prank and a serious work: “‘Finished Dissertation’ is a play in impudence,” they said. It’s a kind of furtive social documentary at a distance, observed through sunglasses at night and tinged with apprehension and a sense of dislocation that lingers from long after 1989, when so much fell apart and so many left Ukraine. A prank it may be, but one couched in a contemporary idiom that is at once faintly plaintive, quietly melancholy even when it laughs, and consistently, raggedly, expressive. As of today, of course, the constant stream of photographs from Ukraine might make one nostalgic for mere dislocation.

The Shilo-Group’s revisions of Mikhailov could hardly be a more direct reference to their local photographic history, and in their own way the members of the group are as intent on telling the story of their period and place as their Ukrainian forebear. But like inheritors mindful of their family’s success yet determined to make their own mark, they have changed both the approach and the ambience. Their images are black and white, gritty, dark with sudden flares of light, sometimes purposefully outrageous, other times simply off kilter. Their street photography is determinedly half legible, the people anonymous, the streets more atmospheric than descriptive, the message hovering on the edge of ambiguity. They develop by lith printing, a process that invites accidents and unpredictability and is, therefore, not reproducible. No two prints are exactly the same, and the group uses Soviet-era paper, which is hard to find and, inevitably, altered by time.

In the Shilo-Group’s kit bag there are also some painted-over and written-over color photographs and a pointed political fantasy called “Timoshenko’s escape or the first step to the exhibition on Mars.” The escape rewrites the fate of Yuliya Tymoschenko, the imprisoned former prime minister of Ukraine, who was released during this year’s revolution. In this narrative, where a mostly naked woman takes the role of Tymoschenko, she escapes and finds Kharkiv, an old industrial city free of excessive charm, so beautiful she decides to stay. That’s current history seen through Alice’s looking glass – or perhaps a grim fairy tale: as of this writing, Tymoschenko is free, has run for election once more, and lost.

Vicki Goldberg is a writer on photography and author of the Aperture book Light Matters.

The post Vicki Goldberg: History in Contemporary Ukrainian Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers