Aperture's Blog, page 176

August 16, 2014

The Lives of the Saints by Charles Bowden

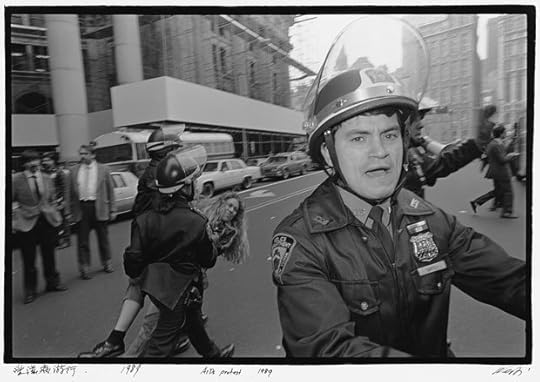

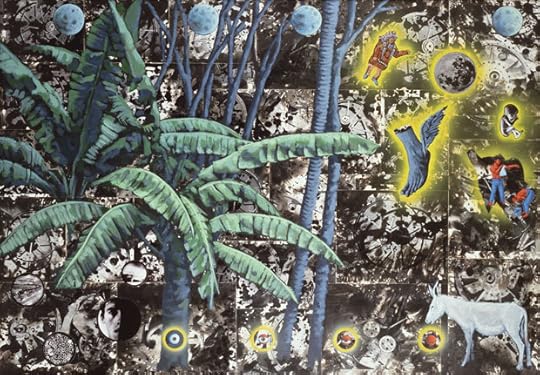

David Wojnarowicz, Where I’ll Go After I’m Gone, 1988-89, courtesy the estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

Hummingbirds appear before dawn, a whirring and darting at the feeders. Black silhouettes maneuver in the faint gray. The great blue heron alights on the power pole, the sun slips over the mountain.

Delphiniums begin to glow with faint lavender and intense blues. The zinnias come on cheap and crass.

I am just up the river, fifty miles from the killing ground of Ciudad Juárez.

The dead follow me. I sit at a table and put secret graveyards on a map, one I cannot publish because such an act would lead to the murder of my sources.

I listen to the birds, the dead slowly drown out the songs.

I hear stories.

Everything seems normal here with miles of pecan groves lining the river under a blue sky.

But I hear stories.

I read old things with fresh eyes. “People travel to wonder at the height of the mountains, at the huge waves of the seas, at the long course of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motion of the stars,” says St. Augustine, “and yet they pass by themselves without wondering.”

The hummingbirds near Patagonia, Arizona, sip almost two gallons at the feeder, then, vanish at dusk. I have come here to erase Juárez from my mind.

I have failed.

The moon rises late in the night hunting through a veil of clouds. Music joins the purl of water wandering the creek and around eight p.m. four men in hoods line up eighteen people in a drug clinic in Ciudad Juárez and kill them. The authorities describe the scene as a river of blood coating the hallway. A chained dog was killed also. Visitors report there is a smell of death in the air.

To the east of me, a rancher is slaughtered.

To the west of me, a border-patrol agent is slaughtered.

And pretty much to the south of me, a seventeen-year-old Mexican guy is slaughtered on the line—the agents say he was throwing rocks.

I listen to songs of New Orleans and plan my exit to the bayous and the brown, sullen waters of the big river. I want to stop hearing the stories, I want to forget, or at the very least, I want to cease to learn.

The river and delta are drugs I need.

Upstream in Arkansas, I am talking to a man painting a wall in an elementary school on the delta. The June air burns. He went up to Detroit in the ’80s, after Nam, after his wars on native ground for civil rights, went up and got into the crack trade and after a while his organization was doing $50 million a year. He wants to write this down, get the killing in Nam down too.

I ask him if he is clean.

He says: “I won’t lie to you, no sir, I am not clean.”

I ask him what he is using.

He says: “Everything.”

I know the feeling. That is why I am on the delta, that is why Juárez seems to keep me on a leash. That is why I keep wanting to hit someone. That is why I just want some peace.

The man keeps painting the wall in the school.

Everything.

But just before dawn as I watch a mouse wander the patio, I realize there is really no way to leave. What I seek is where I am and where I will arrive after all the miles of highway.

One of the hummingbirds at the feeder, a blazing species called Rufous, migrates twelve thousand miles each year, and yet every place it alights finds what it just left behind—insects and nectar to devour. The bird lives in motion to stay where it begins and ends.

The waters of the sea evaporate and wander back to the headwaters as clouds and then the rain falls and the journey down the river renews.

In an hour, the gray light will seep into the sky and a roar will come as they return to the feeders.

Maybe I will wander past myself, full of wonder.

There is the matter of food and drink, also.

There has been a delay because a man sits in front of me and he says that people are sometimes hard to kill.

I feel the door closing behind me and I know it will not be easy to get out of this room.

Once, he explains, he took a contract to murder a very tall and fat man. So when that man entered the room, he hit him in the back of the head with a hammer.

But the man did not go down. He simply turned and said, “Is that any way to greet someone?”

It took a lot of blows to kill him.

The other day I cut catfish fillets, very thin, in the style of southern Louisiana. I washed them in a bath of egg and buttermilk, then dredged them through cornmeal and seasoning.

Another day I rolled out noodles, cut an inch wide with ragged edges. The sauce is made from crushed red pepper, oil, uncured bacon, garlic, tomatoes, cream, pecorino cheese shredded fine.

The need rises. I slice fresh ciabatta, douse with good olive oil, cover with diced tomatoes, anchovies, garlic, garlic, sea salt, and basil. An explosion on the tongue, I uncork the bottle and watch the moss draping down from the trees by the swamp slowly sway.

Such things are not details if you go down by the river.

You must learn to say yes before you can endure the people who say no.

The other day a man told me my problem was simple: I had never been tortured.

When I started out, I planned to farm and eventually die surrounded by the fields and fat cattle. The raw smell of red clover in the meadow has been the fragrance I wished to wash over my life.

In the third or fourth century A.D. an old man dies in North Africa and leaves this epitaph: “Here lies Dion, a pious man; he lived eighty years and planted four thousand trees.”

I wanted to be like that man. He almost certainly planted olive trees, a featured crop of the region. The early fathers of the African church had abundant light for their lamps and could write the mysteries of the faith all night long to the envy of their Italian colleagues.

But there was a chance in the air at the same moment when Dion left his summary of his life. St. Jerome, looking out at a small child, sketched this view of that world: “In such a world Pacatula has been born. Disasters surround her as she plays. She will know of weeping before laughter. . . . She forgets the past; she flees the present; she awaits with eagerness the life to come.”

I live between my Rome and my Jerusalem: my Ciudad Juárez and my New Orleans. Except that neither one is a holy city. And both cities are dying and both cities kill and both cities draw me toward them. And both cities have been written off and in both cities faces without names are writing the future with blood.

I have ignored God or the questions about God since I first walked into the forest and desert. The saints I spent time with in my twenties, when I inhaled drugs and for a spell thought the saints were the fellow outcasts and outlaws of their time. I swallowed whole St. Augustine and St. Jerome, also St. Anselm, St. Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, St. Teresa, St. John of the Cross. And the little flowers of St. Frances of Assisi, especially his time with the wolf. I paid no attention to Christ and Jehovah.

Now in the bright light of a new day as the killing comes down and the ground cracks underfoot, I return to these holy bones stored on dusty shelves in scorned libraries. I blow the cobwebs off, and St. Augustine tumbles down and rests in my hand again.

In an earlier time: The light falls golden, the air sags with moisture and the bayou is still, the waters green and placid. There is a war in Korea, and willing dead men leave this place to join that war. There is always a war during my time on earth, and always a ready supply of willing dead men. Bird cries shred the sky. Food floats from the kitchen: a gumbo with shrimp, andouille, celery, onion, bell pepper, filé, and a very dark roux. The blackened-iron kettle rests on the stove as my aunt stirs, a cotton wrapper clinging to her abundant body. Scents fill the air: her perfume, the gumbo, the swamp smells coming through the screen door.

The land here is flat and mainly underwater. The flatness, a land form I will later learn is called a delta, extends upriver almost to my birthplace in Illinois. Clay at the top, black mud at the bottom. Nasal speech in Illinois, and a mixture of Irish dock accents and rich southern vowels where the waters begin to break free and taste the salt of the sea.

I remember all the furniture in the house on the bayou is veneered with rounded corners and the mirrors are oval. The bedsteads are also veneer, the cigarettes have no filters, and the women leave the red imprint of their lips on the spent stubs. Salt, cayenne, garlic, and green scum on the water. I have always welcomed the night, that darkness rich and stuffed with hidden things. The dawn, also, and the early morning. The rest sometimes seems too bright for seeing things.

I never asked questions. My aunt in the swamps, I don’t know her maiden name. She had a twin sister who died. There was no money, and my earliest memory is of her doing piecework at a sewing machine in a sweatshop. She also held a soft-shelled crab up to my eyes and then later at home pan-fried it and I held it in my child’s hands and ate it like a large cookie.

There have been some questions. I will answer.

What possible link is there between the great delta of the Mississippi River and the poverty and violence of Ciudad Juárez?

Answer: The delta of the Mississippi River is the richest land on earth and for two centuries it has produced the poorest people in the United States. Ciudad Juárez was to be the model for American free-trade theories and for decades it has produced corruption, poverty, and violence.

If you ask what food and cooking has to do with all this, then you do not understand appetite and if you do not understand appetite you will be baffled by love, violence, and death.

I have always been interested in how things get done and so people tell me of their skills and trades and toils and the hazards of their work. The man I spoke of worked at killing people and burying them in Juárez. Sometimes, rotten bodies must be dug up and moved in order to preserve public order and respect for the state.

The skin blisters and the doctors try to understand. They wonder if it comes from work in the chemical industry or some other kind of intense contact. When asked, the patients pause. There is no way to discuss the matter. When a body has been underground a while, the rot advances, especially when lime accelerates decay. And then an order comes to move the bodies, sometimes without any reason. Sometimes because it is discovered that the house has been leased from a significant political figure. And for the owner to have his patio returned with corpses underneath the dirt as he sips his morning coffee and goes over the newspapers, that would be an insult. Despite the best efforts—deep holes, lime, layers of concrete—there is often a seepage of gases through sudden fissures in the soil. It might be evening, a beer cold in the hand, the patio inviting and suddenly there is a layer of odor floating and it is death. This cannot be allowed. Decorum must be observed. The owners, when they occupy their fine houses, should not have to smell death. Such an experience would upend the meaning of money and privilege.

So the bodies must be moved. There is not always time to round up the Hazmat suits. There are chemicals. And then, over time, an intolerance, maybe something called an allergy, that visit to the doctors, the question: Have you worked with chemicals?

This question can be awkward.

Last night, the creek rose and the water went brown with runoff from the hills. Drops fell softly from leaves, the clouds parted after the storm and a waning moon wandered among the stars. The bats hunted insects and came close to my face.

I was twenty miles from the border in Arizona at that exact moment. I felt I was going to where I belonged.

This afternoon, during a brief break in the storm, the sun streamed down on the sunflowers, some yellow, some red and bronze, and the dirt rose up like incense. Yellow, black, and blue butterflies fluttered around and did not fear me.

These are surely signs and I must learn to read them.

St. Augustine became a Christian when he heard a child’s voice singing as he sat in a garden on the edge of the Alps. He raced into the villa, opened St. Paul’s Epistles and saw the line “Not in reveling and drunkenness, not in lust and wantonness, not in quarrels and rivalries. Rather, arm yourself with the Lord Jesus Christ, spend no more thought on nature and nature’s appetites.”

I would not wish his fate on a dog. I cannot imagine what it is like to spurn nature and nature’s appetites.

A young bobcat lives in the bamboo, kills doves in the yard and is willing to look into my face.

In the light rain, a javelina crosses the road in front of me.

Two buck deer emerge from the tall grass by the lane.

The great blue heron fishes the waters and pays me no mind.

Spiders now live over the stove and hang down when I make coffee.

I can sit in public cafés and not be noticed.

When I shop in the market, no one calls the police.

A black bear and cub scavenge the abandoned apple orchard in the bottomland.

There are fireflies after the night falls down.

All the saints seem to see the world as a barrier to their spiritual lives and personal salvation. They find personal salvation more important than the world itself. And they find women to be a menace to their souls.

This is clearly the best case that can be made for seeking damnation. Heaven and Hell do not concern me, nor does the state of my soul. Scorning the world is beyond my understanding. Why be here then?

A faint shower last evening brings up the raw scent of the grass come morning. The sun rises as a disk of gold, the hummingbirds descend with lust in their hearts, acorn woodpeckers pillage the feeders and a vulture sits high in the cottonwood across the wash and basks in the early light. A great blue heron flaps across the sky.

I am always puzzled when I am told life is meaningless.

I am always puzzled when I am told the meaning of life.

I have decided to take all the theories of violence, snap them across my knee and toss the fragments away. All this because my hands are rank with the strong scent of tomato leaves and the sunflowers have seared golden circles into my eyes. The hummingbirds let me stand two feet from the feeder and pay me no never mind.

I have decided to learn from appetites. I will slobber and drool and chew and inhale. I am done with dainty feeding. The quick and the dead share one thing: appetites. They both want to consume things. The theories assume there is a normal world where violence is absent. I see a world of appetites where the thing called violence answers yet one more hunger. Maybe it is the new fast food for those who do not have time for fine dining.

I have decided to drink cold water, eat black pepper, and listen to the stars on black nights.

I have decided.

I am not a camera.

I am not a theory.

I am a hunger.

St. Augustine says: “Some people, in order to discover God, read books. But there is a great book: the very appearance of created things. Look above you! Look below you! Read it. God, whom you want to discover, never wrote that book with ink. Instead, He set before your eyes the thing that He had made. Can you ask for a louder voice than that?”

The saints must keep up appearances.

I have decided.

_____

“The Lives of the Saints” was originally published in Aperture magazine issue #205, Winter 2011.

The post The Lives of the Saints

by Charles Bowden appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 1, 2014

Open Road Test Post

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

The post Open Road Test Post appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

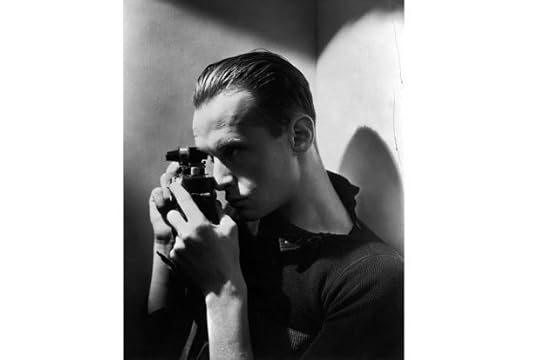

The Other Life of Photographs

by Charles Bowden

The pile of Aperture issues rests on the clean table as cool north light seeps into the old brownstones. I tell myself to think of the half century of issues, sequencings, arguments, and folios as nothing more than flash cards flaming past the eye. I let this blur burn my face and then, I start to understand a little bit.

I seem to die a little bit every time I look at photographs. The woman in the tight dress now can’t wear it, that war is over, we don’t sport hats these days, I don’t play baseball anymore, and wasn’t he famous once? The photos are always then, and I’m always now.

Paul Strand, The White Fence, Port Kent, New York, 1916

There are two other things: I always believe photographs, no matter what I might claim. And I am never intimidated by them. A painting, a poem can face me down as some kind of test. But snapshots have made the output of cameras safe for me. I suspect this feeling of comfort with photographs is common.

As a boy, I found an old photograph in my aunt’s attic and when I looked at it I inhaled a world: I smelled the zinnias, snap-dragons with coarse leaves, blue hydrangeas drooping on the lawn, insects thrumming, the early morning coolness. The dirt smells rich and rank. Morning still hangs in the shadows, and the world is cool like a stone milk-house. All those white chickens by those red wheelbarrows in the yard promising a hard, sure reality where everything is deliberate and nothing is a mystery. Paul Strand points his camera at a white picket fence in Port Kent, New York in 1915 and nails this same chord of visual music that I stumble on in my aunt’s attic, this insistence on the physical reality of the moment.

I can tell. Always, when I look at photographs, I know I can tell what is going on. There is something about photographs that makes us look.

Aperture begins by insisting on an actual world. Lisette Model orders a drink in the blue air of Sammy’s bar in Manhattan, Dorothea Lange captures a signpost at the crossroads, that first cover. Beaumont and Nancy Newhall help prop up this early Aperture, and Nancy lances the tissue of the early issues with essays that cut through artspeak like a scalpel. Barbara Morgan flings dance on the page. Minor White is the soul of the magazine for more than a decade.

The magazine is a tiny thing, and at first it offers a kind of editorial clearing of the throat with fragments of photojournalism—Lange’s embattled America, Lewis Hine with those immigrants shuffling up a staircase at Ellis Island, Ansel Adams’s West, Frida Kahlo, and there’s Marlene Dietrich looking just so in those portraits, early shots of the Pyramids, the waters rising to slaughter a farm valley in California. And then it shifts and amid the little essays in the fifties, the essays that said here is what a professional photographer must do and be, here is how to run that camera, amid these didactic teach-ins, White seeks a kind of deep imagery that signals a connection with an imagined eternal world. One issue has an offhand shot by Barbara Morgan of a girl sitting on a rock playing a recorder. The image is as ancient as a shepherd on a hillside in the Greece of Homer and as recent as the date in the caption: 1945.

I am sitting in Oregon almost a half-century after finding that old snapshot in the attic and I’m talking with my sister on the deck of her house against the mountain. She is taking a hundred pills a day because of the illness and all of her hair has fallen out. I guzzle a glass of wine she is forbidden. I mention the image I found as a child and she is suddenly alert. She goes into the kitchen and fetches an old snapshot taken on the farm: she is maybe seven, in a dress, blond hair, eyes squinting in the sun, I am four, hair cropped like a convict in the uniform style favored after the end of that war.

I tell her of the eerie quality of that old photo I once found, the one that has triggered our conversation. I tell her it had no aesthetic merit, and no explanation but that when I stumbled upon it as a child, I instantly knew what it was and could move beyond its borders and wander the world it came from. There was no date on it, nor handwriting explaining any circumstance. Almost fifty years ago, I climbed up into the attic of my aunt’s farmhouse in Minnesota. I was eight or nine or ten; it was late morning. Dust floated in the air and lay deep on every object, a menagerie of broken chairs, old chests, trunks suitcases, cheap novels. I remember I was looking for hard goods, maybe an old pistol or decommissioned shotgun.

I found the photograph.

A man and a woman sit on the grass. They are very close and stare at the camera. The man wears slacks, suspenders, a white shirt, and glasses with round frames. The woman has a print dress, her hair up in something like a bun. The man is my father, the woman I do not know. But instantly, in the dust and light and shadow of the attic, I know this is my father’s woman. I have never heard of her. Or of much else in his life. Nor will I ever hear much, he was not that kind of man. But at that age in that attic, I instantly knew what was going on in that photo, right down to the flowers blooming outside the frame and time of year and the sounds and smells that have just been in the air, and I knew the woman was no stranger to my father.

I think much of the history and frustration of photography is in that cheap, off-handed image. Photographs convince us.

Minor White explains that there are Seven Levels of Light. He gives out the task: “Illuminate the mind and cast shadows on the psyche.” Minor White cannot be escaped. He is the tortured man who survived World War II better than he did the iron peace of the Cold War. He infused the first decade or more of Aperture with both his faith and his inner turmoil.

“It was a one-man show,” he later noted, “an outlet for my own photographs . . . My own photographs, but other people did them.”

In the early sixties, Minor White decides to end Aperture. He listens to some internal clock in these matters. The thing he has nurtured has a circulation of about 450. And Aperture, an idea fomented by a handful of people in the early fifties and nursed into life and form by White, goes into a free fall, like a drying print that slips loose of the clothespins in a darkroom, flutters off the line and slowly floats to the floor. Michael Hoffman, a student and product of White in Rochester, bounced around the West for a spell, rode the rodeo, and most importantly, Hoffman had the kind of energy and focus required to make something work. It is as if a slumbering volcano suddenly erupted. Aperture becomes a foundation, prints, hundreds of books, and a menu for those curious about what to see and how to see and why to see. Paul Strand, at the end of his career, becomes part of the springboard for this new Aperture when he leaves his archive to the foundation. Aperture finds its way to the future by walking on the photographic bones of the past: Strand’s stark, loving studies of other places, White’s distillation of a lifetime of sequencing in his final testament of books.

I find this Aperture in a small bookstore in Arizona, when I pick up a small volume on Roger Fenton, part of some “Masters of Photography” series, the cover claims, and begin to teach myself how to see by looking at the world through the eyes of people who saw what I missed. A woman shrouded in the yards of requisite Victorian clothing walks the path at Windsor and this world looks so spacious and empty and lonely that I can hear the rustle of her long skirt against the gravel walk. I’d never heard of Aperture and pretty much thought photography was about picnics, weddings, newspapers, and magazines. Michael Hoffman’s Aperture opened up a new world to me. As it happens, the very world I’d always lived in but could not see.

As I write this, Michael Hoffman has just died at age fifty-nine in a New York hospital. I never met him or spoke with him and so I am in a position that most readers of this magazine share: I knew him by his works. He’s the guy who introduced me to Diane Arbus, Edward Weston, W. Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, and a long list of other wizards with cameras. He dragged the poor into my house in books by Sebastião Salgado and Eugene Richards, he made me look at the Chinese hand in Tibet, and the mafia slaughter of Sicily. The Aperture I stumbled upon in a bookstore in Arizona was the face and voice of the man I never met. I used to sit around at night browsing Aperture’s catalog like it was a candy store with open stock. Whatever Aperture now becomes is up to us. But what it is now is what Michael Hoffman created. A lens that could penetrate even my desert hut in Arizona.

You just can’t get to the life of photography without facing all the death in photography. The image is always about the past and this knell of the past is what keeps forcing us to listen to photographs, including those that only trace the evolution of our own faces. Fossils are created in the darkroom.

This is how it goes: I am driving across Nevada at eighty miles an hour, the miscellanies of Minor White flashing across my mind, when I succumb once again to the power of the dead.

I know the sea is down and they are writhing as the sun torches their sensitive skin. There are forty of them marooned in a small mud flat as the waters pull away and decline and this retreat is fatal for them, this retreat of the sea that will leave them dry-docked for two hundred million years. The jaws are powerful for ripping flesh, the body long and firm, running to sixty feet, the fins propel them at twenty-five miles an hour. They fit uneasily into categories, half-fish, half-reptile. They are on the path towards being fossils and the mud will catch every detail of their bodies, the minerals will slowly leach into their bones, gold and quartz filling them cell by cell, making them rock, and the imprint will be so exact that my kind will glance at this negative imprint of their lives and know that they gave live birth, know this fact two hundred million years after the collision of their sexual congress has ended.

In 1977 they are declared the official state fossil of Nevada. They now exist seven hundred thousand feet above sea level in the Shoshone Mountains of central Nevada. They are called Ichthyosaurus Shonisaurus popularis and scholars explain their doom by tectonic-plate movement and uplift and a scale of time that terrifies most people. They look up from stone and I blink and think, Christ, this half-fish-half-reptile has just made one of the first negatives.

I always seem to wind up driving along a lonely highway, storming north at eighty miles an hour toward that visit with my sister in Oregon and in my head I have this heavily plotted conversation I’m going to have with her about the image I glimpsed fifty years ago in my aunt’s attic. I sip stale coffee as the Shoshone Mountains huddle to the north, the sky is overcast, the desert rich in soil color under filtered light. There are few signs of people save the occasional whorehouse that pops up as a cluster of trailers. Fossils everywhere, including in that next frame to be shot.

I pull off at Goldfield, Nevada, a mining town that around 1906 was home to thirty thousand people. The major saloon then required eighty men to tend what was called “the world’s longest bar.” By 1910, this was ending; by 1920, the whole county of Esmeralda held only 2,148 and today it harbors a little over a thousand. Goldfield itself struggles on as a friendly ruin.

I was here once before, in 1959, at age fourteen on my way to Seattle with my father. I was driving so that he could sprawl on the bunk he’d build in a converted bread van and drink without worry. We pulled off in Goldfield because he knew Wyatt Earp had once frequented the area during the boom when he had a liquor and tobacco store. The old man was a fount of such details. We walked past the ancient hotel, a sturdy building, and when I looked in the tables were still set in the dining room, the silver right by the old china.

The old man was in his early sixties, beer-bellied, the stubble of a three-day beard on his face, a baseball cap on his gray head, tri-focals taking in the scene and he looked nothing like the yearning figure in that photo in my aunt’s attic who seemed attached to the woman beside him on the grass. He did not know that I knew of that image or of that woman. I would never bring it up. My father did not answer questions or care what anyone living or dead thought of him. Six years later, when my sister married, he told her that he had been married before and that the marriage did not work and he got a divorce. He told her this, and nothing more, in an effort to comfort her in his clumsy way, so that she would not worry should her marriage fail. And he revealed this just before the wedding. He never told my brother, who is nine years my senior. And of course, no one ever asked him anything about it.

So in 1959, we walked the empty streets of the dead town and came upon a saloon, Silver Dollar Kirby’s. The old man went in and the bar was a plank on two sawhorses, the stock one or two bottles and some shot glasses. He ordered a double and threw it down.

He asked the bearded ancient—Silver Dollar Kirby—“How is it going?”

The graybeard answered, “I get by,” and then paused in deep thought and added, “Well, I’m setting a little aside, too.”

Now I am back, a little over forty years later. The old man is dead, Silver Dollar Kirby long gone. And when I ask at the tiny Goldfield chamber of commerce for the local population figure, I’m told, “They say it is two hundred.”

The town, whatever its numbers, still hosts five saloons.

I can see my father walking down the empty street to a bar, I can see the photograph in the attic, I can hear the sounds of the dying Ichthyosaurus. If you want to talk about where photographs come from and where they go and what they are about you will, in the end, come to the Goldfield, Nevada of your life. And there you will find a sequencing that escapes the shackles of prose. You will look at the fossil of the dying fish/reptile and right before your eyes will appear the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky who is busy killing himself as the sullen weight of Stalin’s Soviet Union fell on his shoulders in the 1930s. There, quite near the body, he has left a final note: “The love boat has crashed against the everyday. . . .”

The emotional response to a photograph is very close to feeling the breath of a prehistoric beast on your neck.

Photography has moved past the debate about whether or not it is an art. Photography has ceased to be a debate about what is and what is not a photograph.

But photographs cannot escape their fate as fossils, as moments of life frozen on paper. And viewers cannot escape their appetite for the content of photographs, an appetite so severe that it often overwhelms standards of aesthetics. O. Winston Link’s ancient steam locomotives look beautiful. But bad photographs of steam locomotives are also oddly compelling because the things within such prints have disappeared. Photography seems to hate borders and consumes just about everything with relish.

In the seventies, and more especially in the eighties and nineties, Aperture gave up on the tutorial and started ranging widely, a beast feeding off the past, then shredding that past with folios of images that had been written on, cut up, had things pasted on them, were held down to the floor while all these new computers had their way with them. Aperture became a place with all kinds of things claiming to be photographs and a lot of people, myself included, kind of get miffed at these antics from time to time. But mainly I think I got upset with such experiments because photographs have content, and in my hidebound way, I didn’t want this content tinkered with by the comments of the photographer—a strange position since the photographer has already scribbled a comment by picking up the camera and framing the shot.

Basically, photographs, cause debate because they incite belief. People want beauty and then, when they get something they’ve heard rumored on the front pages of newspapers, now made solid by images, they want to turn away from these visual reports. And what really upsets most of us, and this is the curse of photographs, is that it is so hard to turn away. Once I see a powerful photograph I cannot seem to erase it, try as I may. But after I’ve enjoyed my tantrum what I like is this: photography can now be damn near anything; the coal miner black as he comes out of the shaft, the spray of pigment in a landscape, a swirling form made with, say, a long exposure and blasts of colored lights. Photographs can be that beauty thing. And they can be that other thing, the thing that sent Kurtz reeling out of the Congo and into the imagination forever: the horror. There is still that tug of Ansel Adams and his shots of some Eden, but my mind cannot help placing them next to Richard Misrach and his nuclear cows dead on the Yucca Flats of our new West.

I have been staring at the work of Tina Modotti as I sit in the wet sun of Oregon. I have looked at the early shots of Talbot and Daguerre and Fenton and others. I believe in Atget’s streets, all 8,500 shots of his imaginary Paris freed from modern machines. I stare into the hard sharp surfaces of f.64, the early flowerings of Aperture as Minor White plunges like an Ichthyosaurus into deeper waters where he senses something eternal hides beneath the waves of life. I have taken to eating pears from the Oregon orchards.

My sister says she heard the woman in the photograph was crazy. Neither of us can remember her name now.

I say that she was a heroin addict, that I know this for a fact but I cannot remember if my aunt said this, or the old man once told me. I have other scraps: once, after our father remarried, our mother recalls the woman’s brother came by the farm. The woman was dead then, of course. And our father and the visitor went out in the farmyard and talked and then the brother left. That is all our mother knows. She could not hear what they said and she did not ask. She tells me the woman’s name was Lillian and I roll it around on my tongue like a jewel.

My sister has a cup full of pills before her on the table and as we talk she steadily takes them, one by one.

“There was something about breaking dishes,” she recalls, “how she would throw the dishes against the wall, or they would both throw them. I think our aunt told me this. I can’t remember. She was also put in an institution once or twice, I remember something about an institution.”

My sister looks at me and says with a smile, “I can deal with anything but the future. Now I have trouble with the future.”

I have seen a photograph of the fossil of the Ichthyosaurus—it looks exactly like a negative: the beast is flattened and yet every detail is there, the teeth, the long porpoiselike mouth, the big body and flippers and fins, the immediate sense that it is a voyager from another time but yet an actual thing, not imaginary, as real as Lillian breaking dishes or loading that syringe or sitting with my father on the grass that promises an endless summer under the sheltering trees with red zinnias nearby.

My mother once told me my father would not remarry until his first wife was dead. I don’t know, I just know about the red zinnias and the snapdragons that are not even physically present in the old photograph. And I know the trapped beasts on Shoshone Mountain writhed as the sun ate their dying skin.

A few days ago, a friend stopped by and I was lost in photographs, staring at vanished worlds and worlds that keep returning. He mentioned a time long ago when we’d both run amuck and stuffed ourselves with drugs and how this experience, now long past, had opened up his mind.

I said this had not happened to me, that I must be some kind of mutant, that when I was young and swam for a season in a sea of chemicals the experience simply confirmed my day-to-day world. I seem to have been born stoned, I mused. I always heard colors, walked through photographs and went around corners and up blind alleys; every window I saw in an image I could enter, like a burglar, and then prowl the inner domains. The nudes always had scent for me, the tumult of the photojournalist was home, the serene rocks and frost on glass panes of Minor White were surfaces I knew before I was born. I had lived a life of déjà vu, and drugs, like photography, seem to enforce this sensation. I have no theory for this, no beliefs, no secret bottle of Carl Jung I keep on the side and toss down under a full moon. Some things simply are.

Homo sapiens is a haunted species. I cannot imagine Ichthyosaurus, even when dying on what would become the Shoshone Mountains, wailing over its fate. But people do and they reach for the camera to capture this sense of their lives passing—passing even though they seem to have just arrived. People are love boats filming their collisions. When their time as lovers has ended, and Tina Modotti slept alone in the house she had shared with Edward Weston in Mexico City, she wrote him, “. . . I accept the tragic conflict between life which continually changes and form which fixes it immutable.”

Minor White once wrote a strange phrase, “Circumambulation of the Light.” And then he advised, “It’s but another step into the dark room.” Yes, I must go now to the dark room. I must go to the old snapshot in the attic and admit this image is not very good, not well exposed, indifferently framed and lacking attention to contrast. The Ichthyosaurus isn’t really art, isn’t really a photograph, isn’t really a negative outside of my clever claims, but like the snapshot it does capture my attention. I look and look hard. Lewis Hine’s immigrants shuffle up that stairway, and I feel some chord struck within me. Dietrich stares up in her pantsuit and top hat and my God I can’t take my eyes away. It’s her, I know it. Charis is naked and Weston captures all those curves, a storm is lifting off the Yosemite Valley and Adams waits for the right instant, Stieglitz hunts the clouds, Lange keeps insisting on stories within every single shot she makes, White is mesmerized by the steam forming frost on the winter windowpane in Rochester, then come all those wars and demonstrations and bluesy nights and someone on a mattress in the East Village is shooting up, Mary Ellen Mark is flinging a teen prostitute into my face and strange visual reports arrive from mysterious continents of the earth. There is an endless roll call of powerful image makers, Sebastião Salgado, Richard Misrach, Sally Mann, Eugene Richards, William Eggleston, Graciela Iturbide, Don McCullin, Cindy Sherman, Robert Frank, Imogen Cunningham, Eugene Smith—who the hell am I forgetting?—and so many themes to explore and rend apart and return to and try to understand again. And I believe it all.

I may like paintings but I seldom believe them—that’s why hotels hang paintings in the rooms and never dare hang a photograph over the bed. I always believe photographs, no matter how fake or inept they are. My father sitting on the grass, the woman is by his side, and they have to be lovers—don’t try to say different—and just outside the frame those red zinnias thrive, the cattle low, and morning coolness hides in the shadows.

I can tell.

And so can you.

______

“The Other Life of Photographs” was originally published in Aperture magazine, issue #167, Summer 2002.

The post The Other Life of Photographs appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

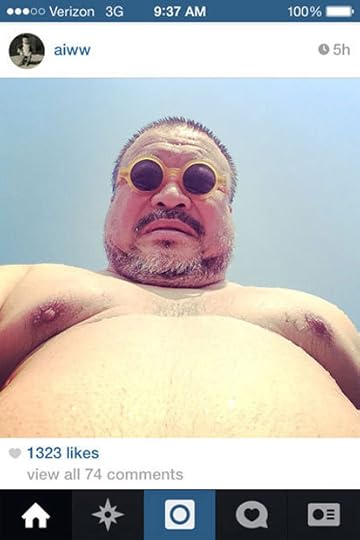

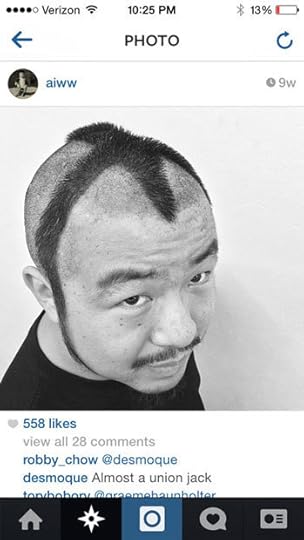

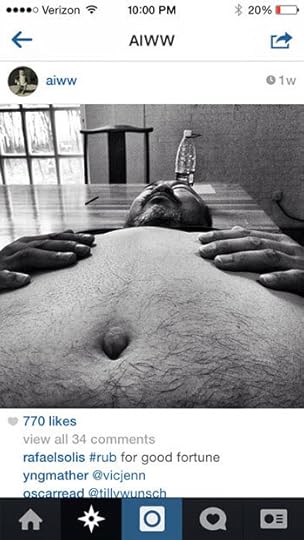

#FF: 13 Aperture Summer Open Photographers on Instagram

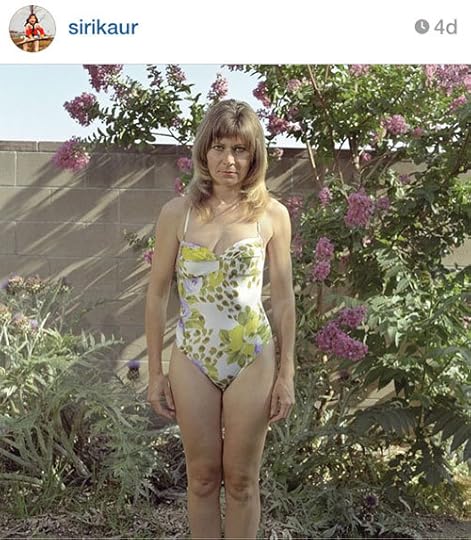

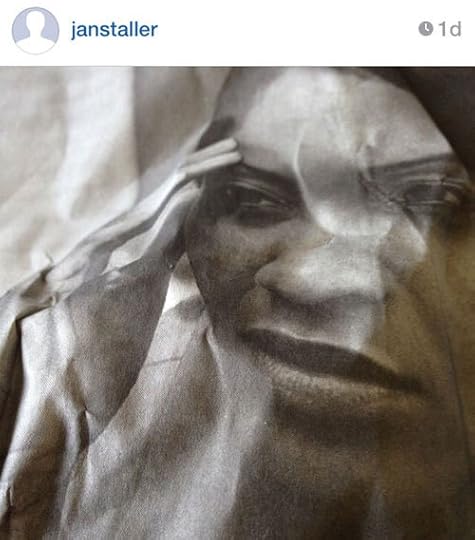

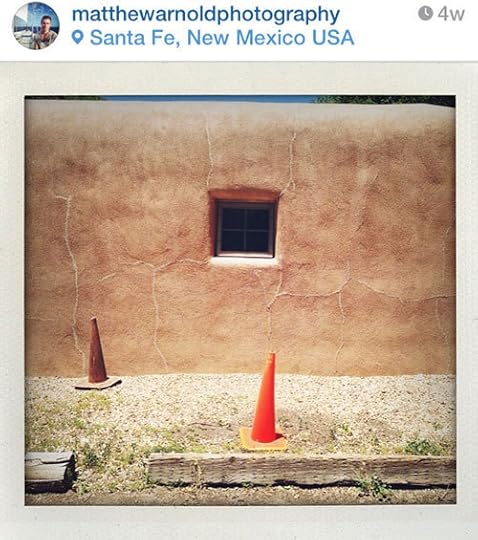

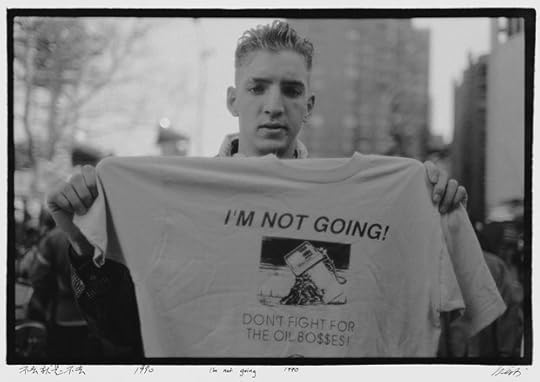

On July 17, we welcomed the public to our first-ever Aperture Summer Open exhibition. The exhibition is a way to show work by a wider group of photographers on our walls, and in doing so, to take the temperature of contemporary photographic practice. Of his selections for the exhibition, Aperture executive director Chris Boot writes, “The work submitted for the exhibition left me with one overwhelming impression that caught me by surprise: that serious photography today, for all its self-awareness and sophistication, is characterized above all by a sense of joy.” The Summer Open is on view until August 14.

We’ve had the pleasure of meeting many of the photographers featured in the Summer Open, both in person and online through social media. We’re delighted to see the ways in which many engage with platforms such as Instagram. We’ve selected a few accounts that we think are worth following:

1. Yijun Liao, @bloodypixy or on Facebook

2. Claire Rosen, @clairerosenphoto. (Image by Ron Haviv.)

3. Ricky Adam, @rickyadam

4. Juan Cristóbal Cobo, @juancristobalcobo

7. Melissa Eder, @melissaederart

8. Joseph Michael Lopez, @josephmlopez. (This image is part of Dear New Yorker, an ongoing body of work intended to be published as a book.)

10. Anna Beeke, @abeeke

11. Matthew Arnold, @matthewarnoldphotography. Arnold recently published a monograph titled Topography is Fate.

12. Mark Steigelman, @msteigelman

13. Beth Galton, @bgalton

The post #FF: 13 Aperture Summer Open

Photographers on Instagram appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 28, 2014

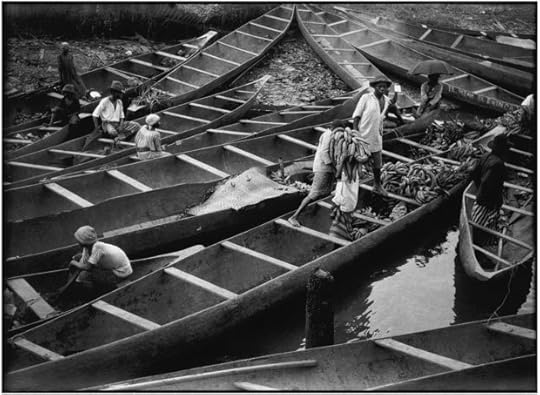

Light Writing in the Tropics: The Story of Hercule Florence

In the 1830s, an adventurer and inventor named Hercule Florence sought to score the Amazon’s abundant birdsong. When attempting to print his peculiar manuscript about nature’s sound archive, he also invented an early form of photography.

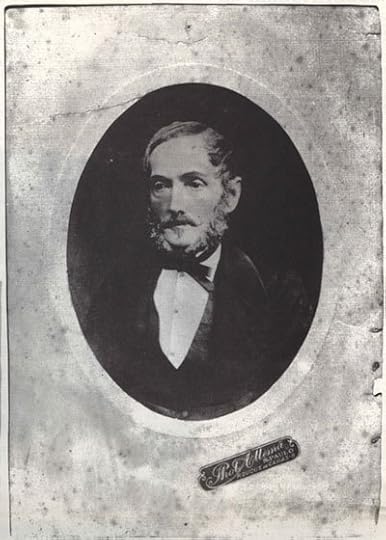

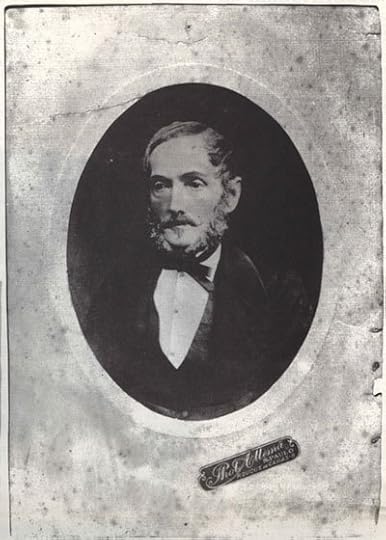

Portrait of Hercule Florence, ca. 1875. Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence (Arnaldo Machado Florence Archive), São Paulo

In a letter dated June 1839, William Henry Fox Talbot wrote to a botanist living in Italy that his “photogenic” drawings, as he named his first proto-photographs made with the aid of a solar microscope, would be “a big help to botanists.” In a later letter Talbot insisted that his invention would be “useful especially to the naturalists, since one can copy the most difficult things with much ease, for example crystallizations, tiny parts of plants, etc. etc.” Little did Talbot, largely credited as one of photography’s inventors, know that six years earlier a twenty-nine-year-old man in Brazil, far removed from the conversations happening in Europe about how to fix light and shadow (including French scientist and politician François Arago’s presentation of the daguerreotype at the Academy of Sciences in Paris in 1839, and British scientist Sir John Herschel’s supposed coining of the word photography the same year with his now-famous phrase “picture obtained by photography” at the Royal Society in London), had invented his own form of “photogenic” writing aimed to aid naturalists.

In 1833, Hercule Florence, a Frenchman who settled on the outskirts of São Paulo after surviving a four-year stint as a draftsman for a Russian Naturalist expedition up the Amazon River basin in the 1820s, invented a mode of reproduction that he called photographie (light writing)—the same words Fox Talbot used years later to describe his invention. Florence arrived at his form of light writing somewhat accidentally. In contrast to the narrative typically used to describe photography’s invention in Europe, it was not the joint achievement of nineteenth- century chemists and artists experimenting with light and silver compounds, nor that of Romantic poets desiring to apprehend that unruly living organism called nature. Instead it was the end result of a long search for a mode of printing. Specifically, Florence wanted to print and distribute a transcription method he had developed to organize and systematize the sounds of nature found in the Amazon region.

Florence was twenty when he arrived in the newly proclaimed Brazilian Empire in the early 1820s, living first in Rio de Janeiro, where he worked at a bookstore and printing press, before settling down some years later in the small village of São Carlos (Campinas), outside of São Paulo, for the remainder of his life. He hadn’t been living in his adopted country for long before he responded to an advertisement for an expedition led by Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff and was hired to be the group’s second draftsman (along with the well-known German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas and a younger artist named Aimé Adrien Taunay, although Rugendas would be dismissed before the journey began, after falling out with Langsdorff ). The expedition’s aim was to reach Pará, in the Amazon basin, through a fluvial route, while engaging in botanical, astronomical, and cartographic observations typical of such ventures. Close reading of Florence’s sporadic diary entries from these years reveals that despite his penchant for travel and adventure—a trait that brought him to Brazil—he found the expedition tiresome, describing the journey as a “grueling, anguished, and unfortunate peregrination” and noting time and again that “to see one Brazilian village is to see almost all of them.” These observations are not surprising for a man who often commented on the lack of culture and excess of nature in his adopted homeland. The watercolor views and landscapes that Florence produced as a hired painter bored him. What was the purpose, he asked in his diary, of visually reproducing the natural world, of composing collections that could only imitate existing collections and inventories gathered and archived throughout Europe? Was there nothing uncharted and original left to continue expanding the inventory of the world? Had nature been turned, in this way, into nothing more than a dead still life—obvious and trivial, predictable, lifeless?

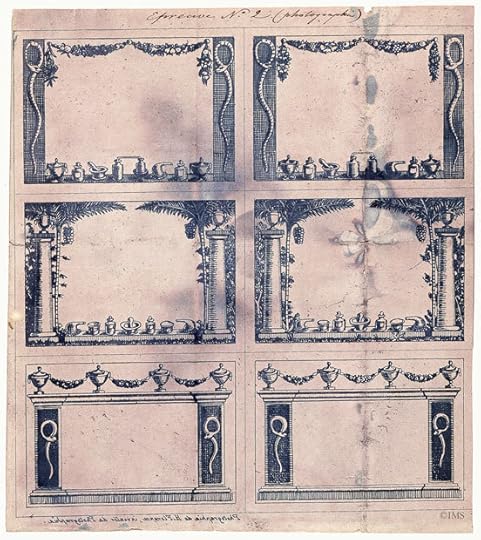

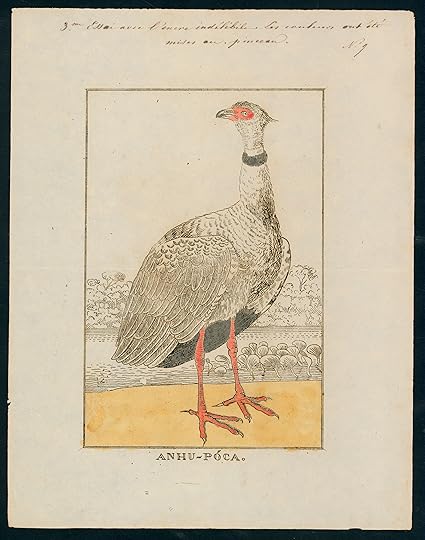

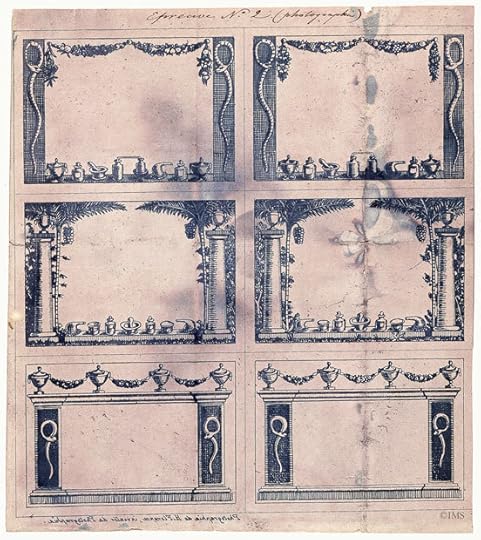

Hercule Florence, Photographic copy of pharmacy labels obtained through direct contact with photosensitive paper under the action of sunlight, ca. 1833. The lower left margin reads (in reverse): “Photography by H. Florence, inventor of photography.” © Instituto Moreira Salles

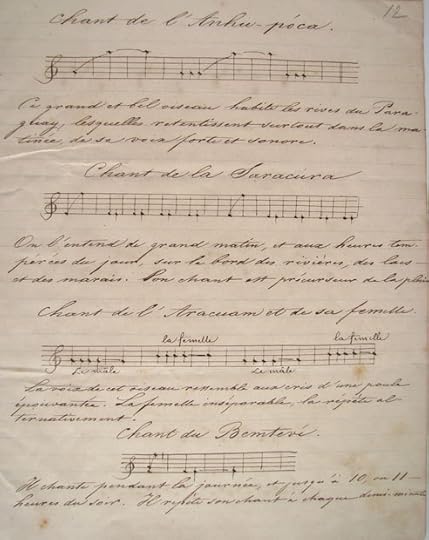

Craving a recording of the natural world that offered infinite uniqueness, singularity, and power, Florence fixated on the idea that while the naturalist expeditions of the first decades of the nineteenth century had created encyclopedic and cartographic knowledge, they never contemplated the possibility of a sonic inventory. “With great zeal we have tried to, and continue to try to, learn everything that is known about animals,” Florence wrote. “Even the most minimal details have not been ignored; for this reason expensive and arduous voyages have been made to almost every point on the globe; collections of animals were thus made at an enormous cost to the museums of the great cities; the descriptions and drawings allow them to become known throughout the world.” Ironically, Florence would have more opportunities to indulge his theories about sound as the expedition ran into grave problems, derailing hopes of becoming the most scientifically important journey of its kind in the region: Taunay would drown crossing a river; the group’s astronomer came down with beriberi, a tropical disease that afflicted many slaves in colonial Brazil; Langsdorff, as well as half of the team, was stricken with malaria and suffered high, debilitating fevers, resulting in his complete insanity and loss of memory. Amid this chaos, Florence sidelined his official work and turned his attentions to the universe of sounds enveloping him. He began a series of notations recording the calls of birds, the croaks of frogs, and noises made by other animals. Of a bird called araponga, Florence writes that “it is beautiful…it makes a sound that imitates well the banging of a hammer on an anvil,” and of the singing of the anhu-póca: “it is big, its voice strong and euphonious; repeats this sound every fourth of a minute.” Florence approximated the corresponding notations to the sounds he heard and then produced musical scores, a method he dubbed zoophonie. The outsized ambition of his desire to catalogue all the jungle’s birdsong was not lost on Florence: “when one considers how much animals’ voices vary to infinity, one tends to think that it is almost impossible to transcribe them without using an infinite number of signs … the method that I am here giving is only a first attempt … .”

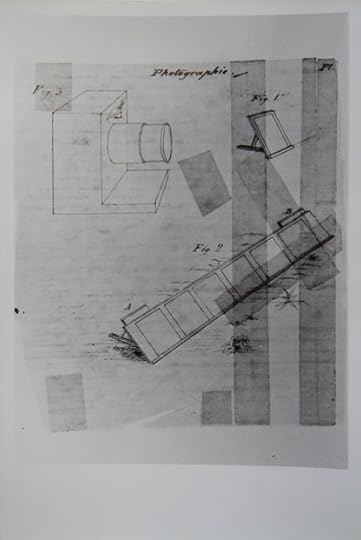

In 1831, after returning home from his journeys, Florence attempted to print and circulate his notes and manuscript outlining his zoophonie. The cumbersomely titled text, Research on the Voice of Animals or Essay on a New Subject of Study Offered to the Friends of Nature, detailed his discovery of nature’s potential sound archive and proposed his novel method of capturing and recording the immaterial, enchanted animal sounds of the Brazilian tropical forests. Florence, however, ran into difficulties finding a printer for his manuscript—a struggle that reveals how his experimentation with photography belongs to the story of a fragile, emerging early-nineteenth-century print culture. Few printing presses then existed in Brazil because the Portuguese Crown sought to control the spread of anti-colonial propaganda. But Florence would not be deterred. This obstacle motivated him to find a more accessible and democratic mode of reproduction, one that utilized a resource available to all, sunlight. Unlike the European figures credited with the invention of the medium, Florence used photography to reproduce symbols and written artifacts, not the visible world. His first attempts with the process resulted in a print made around 1833 of pharmacy labels, likely produced for his friend and collaborator Joaquim Corrêa de Mello, a chemist who at the time lived in Campinas, the same village as Florence, and helped him learn the properties of silver nitrate. These six pharmacy labels on a single sheet of paper demonstrate how, for Florence, photography functioned as a mode of reproduction analogous to printing. His method worked much like a modern-day photocopy—and, significantly, these labels reveal how seriality was ingrained in his work, something that standard accounts of photography’s history attribute to the invention of the carte-de-visite decades later. His notebooks and diaries also reveal that he worked on other photographs: a photographic copy of a Masonic Diploma and one of his own hand-drawn designs for a camera obscura and other items needed for the photographic process. Ultimately, Florence did not use this method to print his manuscript, as he finally convinced a printing press in Rio de Janeiro to publish his findings, though there is no record of how his zoophonie was received.

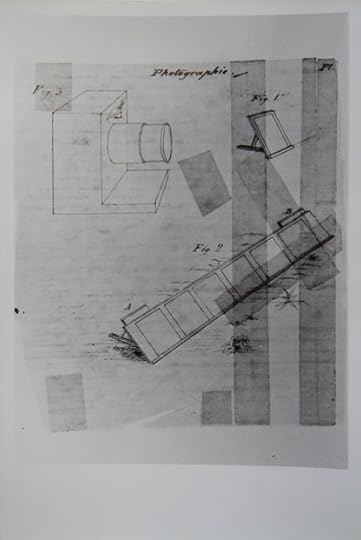

“Equipment used for photography,” originally appeared in Florence’s manuscript, L’Ami des Arts…, 1837. Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence (Arnaldo Machado Florence Archive)

On May 1, 1839, the Rio de Janeiro–based newspaper Jornal do Commercio announced the invention of what would become known as the daguerreotype, calling the invention a “revolution in the arts of design,” in which “nature appears portraying itself, copying its works as well as works of art…. Light, light itself was the painter.” Six months later, in response to the announcement of Louis Daguerre’s method, Florence published a press release in the São Paulo–based newspaper A Phenix in which he stated that he had already been working on photographic printing methods for nine years and that these experiments led him first to the invention of polygraphy (a form of printing that used sunlight, stencils, and chemistry to reproduce texts or graphics) and then to the “discovery” of “fixing of images in the camera obscura through the action of light.” He continued, “I will not dispute anyone’s discoveries, because one same idea can come to two persons, and because I always considered my findings precarious.” When Florence’s press release was reprinted in Rio two months later, it was prefaced by a journalist’s note stating, “Let the readers compare the dates and decide if the world owes the discovery of Photography, or at the very least of Polygraphy, to Europe or to Brazil.”

Daguerre had received a life pension from the French government, and Florence hoped to obtain the same. He wrote letters and made his case to the French Academy of Sciences but never received any serious response, and his diary entries from this time convey his resentment at being overlooked. “Photography is the wonder of the century. I had also already established the grounds, foreseen this art in all its majesty. I did it [photography] before Daguerre’s process, but I worked in exile. I printed by means of sunlight seven years before photography was first talked about. I had already given it that name; however, all honors to Daguerre.” The French invention caught on and became popular in Brazil; in 1840, fourteen-year-old Pedro II, about to be crowned Second Emperor of Brazil, had the daguerreotype technique demonstrated to him. The young emperor became enamored with the invention, turning into the first promoter of official photography within a monarchy, introducing the title of “Crown Photographer” before Queen Victoria in England.

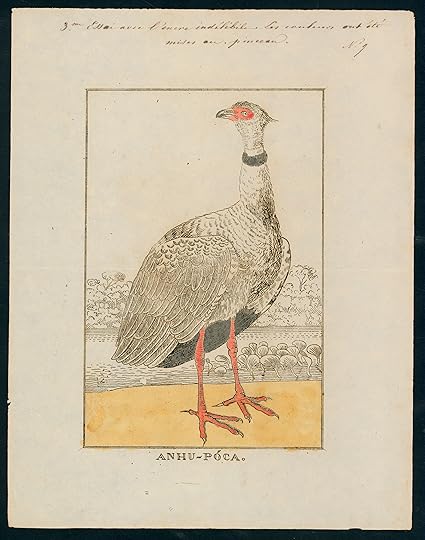

Hercule Florence, Anhu-póca, n.d. (polygraphic drawing). © Instituto Moreira Salles

A tireless inventor despite lack of fame, fortune, or even credit, Florence continued to experiment with reproduction. In the late 1830s, he purchased a typography machine, obtained the necessary license to operate it, and printed advertisements and the short-lived revolutionary newspaper O Paulista that became the “fuel of the liberal movement” until the anti- monarchical revolt had been squashed, forcing Florence to disappear his machine after printing only four editions. In the early 1840s, about a decade after his first experiments with photography, Florence invented unique and inimitable paper money. The move from photography to money might seem a stretch, but both share an inherent seriality. A banking crisis of 1864 that resulted in a reconfiguration of the banking and commerce system made it evident that money, both paper and coin, were difficult to authenticate. Florence seized on the economic tumult by introducing paper that, because of the “sharpness” it allowed in printing, the “microscopic traces,” and the “indelible” quality of the printed colors and patterns could, as his 1842 advertisement claimed, “guarantee … against forgeries.” But this, too, failed to catch on. Yet Florence never gave up: In 1859 he patented a reproduction technique he called “stereopainting” and, soon thereafter “solar painting,” though we don’t know much about what these intriguing projects entailed. His last known “invention” was what he called “The Sixth Order of Architecture, or Brazilian Order.” This order consisted of columns, pediments, and other architectural details inspired by Brazilian palm trees, already an icon of the country. Greece produced the three known orders of architectural style—the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—that symbolized the roots of Western architecture. Florence seems to have wanted to put Brazil on the cultural map by inventing a style or order that reflected the country’s tropical environs.

Hercule Florence, Tête et pate de l’anhu-póca (Head and feet of anhu-póca bird, or Southern screamer), Paraguay river, 1826, from Expedição Langsdorff ao Brasil 1821–1829. Volume 3: Aquarelas e desenhos de Florence (Langsdorff expedition to Brazil 1821–1829. Volume 3: Watercolors and drawings). Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence, Saõ Paulo, and Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg

Why didn’t any of Florence’s ideas and inventions flourish? Most likely his status as an outsider within the highly structured political and class system in nineteenth-century Brazil, with its strong monarchy and organized cultural centers clustered in Rio de Janeiro and the northern city of Recife, is to blame for his lack of recognition. Though his name would fall into obscurity rather than becoming canonized in photography histories, he seems to have passed his later years rather contentedly in the small town of Campinas, where he fathered twenty children and lived on a beautiful fazenda (ranch).

A century passed before Florence’s remarkable achievements were discovered. In the early 1970s, Boris Kossoy, a Brazilian photographer and photography historian who came across Florence’s “alleged” invention through mentions in specialized Brazilian publications, began his research on what he called the “isolated discovery of photography in Brazil.” To build his case Kossoy traveled to the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, to test, with the aid of technicians, the notations made by Florence about his photographic experiments. His tests proved that Florence had indeed invented a photographic process in 1833. Around the same time his photographic discoveries were being at last acknowledged, his studies of Amazon sounds were also finding new supporters in the emerging field of bioacoustics, or animal communications. In 1978, the world-famous French ornithologist Jacques Vielliard was invited by the University of Campinas, on the outskirts of the city of São Paulo, in Florence’s hometown, to establish what would become the most important bioacoustics lab in the Americas. Vielliard amassed an enormous collection of tropical sounds, creating the “Neotropical Sound Archive,” and in 2005 set up a second archive called the “Amazonian Sound Archive,” housed at the Federal University of Pará.

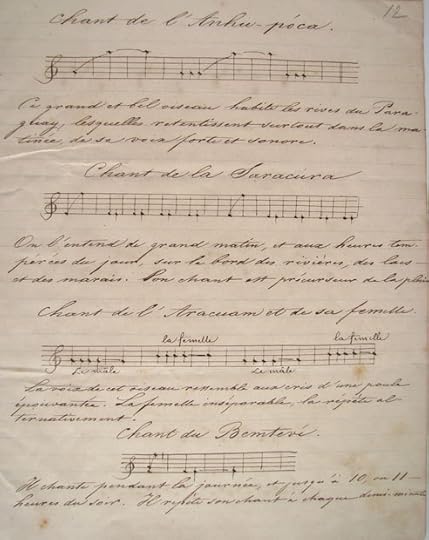

Page from Hercule Florence’s manuscript Voyage fluvial du Tieté a l’Amazone (Fluvial voyage from the Tieté to the Amazon river), 1831, which included many examples of his zoophonie notations. Courtesy Archive of the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, and Instituto Hercule Florence, São Paulo

More recently, contemporary artists have found Florence a source of inspiration. In the nineties, German sound artist Michael Fahres, working with a group of artists from Russia, Germany, and Brazil, retraced Florence’s journey with the Langsdorff expedition and reinterpreted his zoophonie. Italian photographer Linda Nagler is preparing a multimedia art exhibition around Florence’s many artistic and scientific explorations for the New National Museum of Monaco in 2015. An Argentine trio including writer Pola Oloixarac, photographer Luna Paiva, and composer Esteban Insinger wrote a contemporary opera called “Hercule Florence in Mato Grosso,” which will premiere in Buenos Aires this October. Perhaps Florence was neither a naturalist nor an inventor but rather a conceptual artist who was ahead of his time.

______

Natalia Brizuela is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Fotografia e império: Paisagens de um Brasil moderno (Photography and Empire: Landscapes of a modern Brazil) (Companhia das Letras, 2012) and the forthcoming Uma literatura fora de si. Escrita e fotografia (A literature beside itself: Writing and photography) (Rocco, 2014).

The post Light Writing in the Tropics:

The Story of Hercule Florence appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Light Writing in the Tropics: The Story of Hercule Florence by Natalia Brizuela

In the 1830s, an adventurer and inventor named Hercule Florence sought to score the Amazon’s abundant birdsong. When attempting to print his peculiar manuscript about nature’s sound archive, he also invented an early form of photography.

Portrait of Hercule Florence, ca. 1875. Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence (Arnaldo Machado Florence Archive), São Paulo

In a letter dated June 1839, William Henry Fox Talbot wrote to a botanist living in Italy that his “photogenic” drawings, as he named his first proto-photographs made with the aid of a solar microscope, would be “a big help to botanists.” In a later letter Talbot insisted that his invention would be “useful especially to the naturalists, since one can copy the most difficult things with much ease, for example crystallizations, tiny parts of plants, etc. etc.” Little did Talbot, largely credited as one of photography’s inventors, know that six years earlier a twenty-nine-year-old man in Brazil, far removed from the conversations happening in Europe about how to fix light and shadow (including French scientist and politician François Arago’s presentation of the daguerreotype at the Academy of Sciences in Paris in 1839, and British scientist Sir John Herschel’s supposed coining of the word photography the same year with his now-famous phrase “picture obtained by photography” at the Royal Society in London), had invented his own form of “photogenic” writing aimed to aid naturalists.

In 1833, Hercule Florence, a Frenchman who settled on the outskirts of São Paulo after surviving a four-year stint as a draftsman for a Russian Naturalist expedition up the Amazon River basin in the 1820s, invented a mode of reproduction that he called photographie (light writing)—the same words Fox Talbot used years later to describe his invention. Florence arrived at his form of light writing somewhat accidentally. In contrast to the narrative typically used to describe photography’s invention in Europe, it was not the joint achievement of nineteenth- century chemists and artists experimenting with light and silver compounds, nor that of Romantic poets desiring to apprehend that unruly living organism called nature. Instead it was the end result of a long search for a mode of printing. Specifically, Florence wanted to print and distribute a transcription method he had developed to organize and systematize the sounds of nature found in the Amazon region.

Florence was twenty when he arrived in the newly proclaimed Brazilian Empire in the early 1820s, living first in Rio de Janeiro, where he worked at a bookstore and printing press, before settling down some years later in the small village of São Carlos (Campinas), outside of São Paulo, for the remainder of his life. He hadn’t been living in his adopted country for long before he responded to an advertisement for an expedition led by Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff and was hired to be the group’s second draftsman (along with the well-known German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas and a younger artist named Aimé Adrien Taunay, although Rugendas would be dismissed before the journey began, after falling out with Langsdorff ). The expedition’s aim was to reach Pará, in the Amazon basin, through a fluvial route, while engaging in botanical, astronomical, and cartographic observations typical of such ventures. Close reading of Florence’s sporadic diary entries from these years reveals that despite his penchant for travel and adventure—a trait that brought him to Brazil—he found the expedition tiresome, describing the journey as a “grueling, anguished, and unfortunate peregrination” and noting time and again that “to see one Brazilian village is to see almost all of them.” These observations are not surprising for a man who often commented on the lack of culture and excess of nature in his adopted homeland. The watercolor views and landscapes that Florence produced as a hired painter bored him. What was the purpose, he asked in his diary, of visually reproducing the natural world, of composing collections that could only imitate existing collections and inventories gathered and archived throughout Europe? Was there nothing uncharted and original left to continue expanding the inventory of the world? Had nature been turned, in this way, into nothing more than a dead still life—obvious and trivial, predictable, lifeless?

Hercule Florence, Photographic copy of pharmacy labels obtained through direct contact with photosensitive paper under the action of sunlight, ca. 1833. The lower left margin reads (in reverse): “Photography by H. Florence, inventor of photography.” © Instituto Moreira Salles

Craving a recording of the natural world that offered infinite uniqueness, singularity, and power, Florence fixated on the idea that while the naturalist expeditions of the first decades of the nineteenth century had created encyclopedic and cartographic knowledge, they never contemplated the possibility of a sonic inventory. “With great zeal we have tried to, and continue to try to, learn everything that is known about animals,” Florence wrote. “Even the most minimal details have not been ignored; for this reason expensive and arduous voyages have been made to almost every point on the globe; collections of animals were thus made at an enormous cost to the museums of the great cities; the descriptions and drawings allow them to become known throughout the world.” Ironically, Florence would have more opportunities to indulge his theories about sound as the expedition ran into grave problems, derailing hopes of becoming the most scientifically important journey of its kind in the region: Taunay would drown crossing a river; the group’s astronomer came down with beriberi, a tropical disease that afflicted many slaves in colonial Brazil; Langsdorff, as well as half of the team, was stricken with malaria and suffered high, debilitating fevers, resulting in his complete insanity and loss of memory. Amid this chaos, Florence sidelined his official work and turned his attentions to the universe of sounds enveloping him. He began a series of notations recording the calls of birds, the croaks of frogs, and noises made by other animals. Of a bird called araponga, Florence writes that “it is beautiful…it makes a sound that imitates well the banging of a hammer on an anvil,” and of the singing of the anhu-póca: “it is big, its voice strong and euphonious; repeats this sound every fourth of a minute.” Florence approximated the corresponding notations to the sounds he heard and then produced musical scores, a method he dubbed zoophonie. The outsized ambition of his desire to catalogue all the jungle’s birdsong was not lost on Florence: “when one considers how much animals’ voices vary to infinity, one tends to think that it is almost impossible to transcribe them without using an infinite number of signs … the method that I am here giving is only a first attempt … .”

In 1831, after returning home from his journeys, Florence attempted to print and circulate his notes and manuscript outlining his zoophonie. The cumbersomely titled text, Research on the Voice of Animals or Essay on a New Subject of Study Offered to the Friends of Nature, detailed his discovery of nature’s potential sound archive and proposed his novel method of capturing and recording the immaterial, enchanted animal sounds of the Brazilian tropical forests. Florence, however, ran into difficulties finding a printer for his manuscript—a struggle that reveals how his experimentation with photography belongs to the story of a fragile, emerging early-nineteenth-century print culture. Few printing presses then existed in Brazil because the Portuguese Crown sought to control the spread of anti-colonial propaganda. But Florence would not be deterred. This obstacle motivated him to find a more accessible and democratic mode of reproduction, one that utilized a resource available to all, sunlight. Unlike the European figures credited with the invention of the medium, Florence used photography to reproduce symbols and written artifacts, not the visible world. His first attempts with the process resulted in a print made around 1833 of pharmacy labels, likely produced for his friend and collaborator Joaquim Corrêa de Mello, a chemist who at the time lived in Campinas, the same village as Florence, and helped him learn the properties of silver nitrate. These six pharmacy labels on a single sheet of paper demonstrate how, for Florence, photography functioned as a mode of reproduction analogous to printing. His method worked much like a modern-day photocopy—and, significantly, these labels reveal how seriality was ingrained in his work, something that standard accounts of photography’s history attribute to the invention of the carte-de-visite decades later. His notebooks and diaries also reveal that he worked on other photographs: a photographic copy of a Masonic Diploma and one of his own hand-drawn designs for a camera obscura and other items needed for the photographic process. Ultimately, Florence did not use this method to print his manuscript, as he finally convinced a printing press in Rio de Janeiro to publish his findings, though there is no record of how his zoophonie was received.

“Equipment used for photography,” originally appeared in Florence’s manuscript, L’Ami des Arts…, 1837. Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence (Arnaldo Machado Florence Archive)

On May 1, 1839, the Rio de Janeiro–based newspaper Jornal do Commercio announced the invention of what would become known as the daguerreotype, calling the invention a “revolution in the arts of design,” in which “nature appears portraying itself, copying its works as well as works of art…. Light, light itself was the painter.” Six months later, in response to the announcement of Louis Daguerre’s method, Florence published a press release in the São Paulo–based newspaper A Phenix in which he stated that he had already been working on photographic printing methods for nine years and that these experiments led him first to the invention of polygraphy (a form of printing that used sunlight, stencils, and chemistry to reproduce texts or graphics) and then to the “discovery” of “fixing of images in the camera obscura through the action of light.” He continued, “I will not dispute anyone’s discoveries, because one same idea can come to two persons, and because I always considered my findings precarious.” When Florence’s press release was reprinted in Rio two months later, it was prefaced by a journalist’s note stating, “Let the readers compare the dates and decide if the world owes the discovery of Photography, or at the very least of Polygraphy, to Europe or to Brazil.”

Daguerre had received a life pension from the French government, and Florence hoped to obtain the same. He wrote letters and made his case to the French Academy of Sciences but never received any serious response, and his diary entries from this time convey his resentment at being overlooked. “Photography is the wonder of the century. I had also already established the grounds, foreseen this art in all its majesty. I did it [photography] before Daguerre’s process, but I worked in exile. I printed by means of sunlight seven years before photography was first talked about. I had already given it that name; however, all honors to Daguerre.” The French invention caught on and became popular in Brazil; in 1840, fourteen-year-old Pedro II, about to be crowned Second Emperor of Brazil, had the daguerreotype technique demonstrated to him. The young emperor became enamored with the invention, turning into the first promoter of official photography within a monarchy, introducing the title of “Crown Photographer” before Queen Victoria in England.

Hercule Florence, Anhu-póca, n.d. (polygraphic drawing). © Instituto Moreira Salles

A tireless inventor despite lack of fame, fortune, or even credit, Florence continued to experiment with reproduction. In the late 1830s, he purchased a typography machine, obtained the necessary license to operate it, and printed advertisements and the short-lived revolutionary newspaper O Paulista that became the “fuel of the liberal movement” until the anti- monarchical revolt had been squashed, forcing Florence to disappear his machine after printing only four editions. In the early 1840s, about a decade after his first experiments with photography, Florence invented unique and inimitable paper money. The move from photography to money might seem a stretch, but both share an inherent seriality. A banking crisis of 1864 that resulted in a reconfiguration of the banking and commerce system made it evident that money, both paper and coin, were difficult to authenticate. Florence seized on the economic tumult by introducing paper that, because of the “sharpness” it allowed in printing, the “microscopic traces,” and the “indelible” quality of the printed colors and patterns could, as his 1842 advertisement claimed, “guarantee … against forgeries.” But this, too, failed to catch on. Yet Florence never gave up: In 1859 he patented a reproduction technique he called “stereopainting” and, soon thereafter “solar painting,” though we don’t know much about what these intriguing projects entailed. His last known “invention” was what he called “The Sixth Order of Architecture, or Brazilian Order.” This order consisted of columns, pediments, and other architectural details inspired by Brazilian palm trees, already an icon of the country. Greece produced the three known orders of architectural style—the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—that symbolized the roots of Western architecture. Florence seems to have wanted to put Brazil on the cultural map by inventing a style or order that reflected the country’s tropical environs.

Hercule Florence, Tête et pate de l’anhu-póca (Head and feet of anhu-póca bird, or Southern screamer), Paraguay river, 1826, from Expedição Langsdorff ao Brasil 1821–1829. Volume 3: Aquarelas e desenhos de Florence (Langsdorff expedition to Brazil 1821–1829. Volume 3: Watercolors and drawings). Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence, Saõ Paulo, and Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg

Why didn’t any of Florence’s ideas and inventions flourish? Most likely his status as an outsider within the highly structured political and class system in nineteenth-century Brazil, with its strong monarchy and organized cultural centers clustered in Rio de Janeiro and the northern city of Recife, is to blame for his lack of recognition. Though his name would fall into obscurity rather than becoming canonized in photography histories, he seems to have passed his later years rather contentedly in the small town of Campinas, where he fathered twenty children and lived on a beautiful fazenda (ranch).

A century passed before Florence’s remarkable achievements were discovered. In the early 1970s, Boris Kossoy, a Brazilian photographer and photography historian who came across Florence’s “alleged” invention through mentions in specialized Brazilian publications, began his research on what he called the “isolated discovery of photography in Brazil.” To build his case Kossoy traveled to the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, to test, with the aid of technicians, the notations made by Florence about his photographic experiments. His tests proved that Florence had indeed invented a photographic process in 1833. Around the same time his photographic discoveries were being at last acknowledged, his studies of Amazon sounds were also finding new supporters in the emerging field of bioacoustics, or animal communications. In 1978, the world-famous French ornithologist Jacques Vielliard was invited by the University of Campinas, on the outskirts of the city of São Paulo, in Florence’s hometown, to establish what would become the most important bioacoustics lab in the Americas. Vielliard amassed an enormous collection of tropical sounds, creating the “Neotropical Sound Archive,” and in 2005 set up a second archive called the “Amazonian Sound Archive,” housed at the Federal University of Pará.

Page from Hercule Florence’s manuscript Voyage fluvial du Tieté a l’Amazone (Fluvial voyage from the Tieté to the Amazon river), 1831, which included many examples of his zoophonie notations. Courtesy Archive of the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, and Instituto Hercule Florence, São Paulo

More recently, contemporary artists have found Florence a source of inspiration. In the nineties, German sound artist Michael Fahres, working with a group of artists from Russia, Germany, and Brazil, retraced Florence’s journey with the Langsdorff expedition and reinterpreted his zoophonie. Italian photographer Linda Nagler is preparing a multimedia art exhibition around Florence’s many artistic and scientific explorations for the New National Museum of Monaco in 2015. An Argentine trio including writer Pola Oloixarac, photographer Luna Paiva, and composer Esteban Insinger wrote a contemporary opera called “Hercule Florence in Mato Grosso,” which will premiere in Buenos Aires this October. Perhaps Florence was neither a naturalist nor an inventor but rather a conceptual artist who was ahead of his time.

______

Natalia Brizuela is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Fotografia e império: Paisagens de um Brasil moderno (Photography and Empire: Landscapes of a modern Brazil) (Companhia das Letras, 2012) and the forthcoming Uma literatura fora de si. Escrita e fotografia (A literature beside itself: Writing and photography) (Rocco, 2014).

The post Light Writing in the Tropics:

The Story of Hercule Florence

by Natalia Brizuela appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 25, 2014

Elaine Goldman and Julie Saul Host Aperture Members

Image © Gabrielle Pasternak

Image © Gabrielle Pasternak

Image © Gabrielle Pasternak

On Monday, July 21, Aperture Foundation trustee Elaine Goldman hosted an intimate evening for Aperture Members at the Friend level and above at her home in Greenwich Village, including a private tour of her photography collection as well as a conversation and Q&A session with gallerist Julie Saul. Guests enjoyed learning about personal approaches to collecting, and exchanged ideas on the changing medium and market of photography. A wonderful spokesperson for the medium, Elaine encouraged the nascent collector to have courage, buy with passion, and accept “mistakes” and “successes” as part of the learning process.

A very special thanks to Elaine and Julie for the inspiring conversation!

More than ever before, Aperture is a defining voice in photographic scholarship and criticism, leading the debate about the art and culture of photography for over sixty years.

For more information about Aperture’s membership programs please visit aperture.org/join.

The post Elaine Goldman and Julie Saul Host Aperture Members appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 24, 2014

Recap: Aperture Summer Open Opening Reception