Aperture's Blog, page 180

May 19, 2014

“Eyes on the Street”: Street Photography in the 21st Century (Video)

On Saturday, May 10, 2014, Aperture hosted a panel discussion addressing street photography in the twenty-first century, featuring Philip-Lorca diCorcia, James Nares, and Katherine A. Bussard. The panel was moderated by Brian Sholis, associate curator of photography at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

At a moment when public discussion of cameras in public spaces revolves around policing and First Amendment rights, can artists and photographers use photography and film to reveal new facets of the urban environment? Can artworks remind us that urban public places are also home to unequaled creative and imaginative possibilities? Philip-Lorca diCorcia and James Nares are both artists whose work was included in an exhibition on street photography at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Katherine A. Bussard is curator of photography at Princeton University Art Museum and author of Unfamiliar Streets (Yale, 2014).

View “‘Eyes on the Street’: Street Photography in the Twenty-First Century” Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 on Vimeo.

The post “Eyes on the Street”: Street Photography in the 21st Century (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 15, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Sean O’Hagan on Ed van der Elsken, Love on the Left Bank

This is part of the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in The PhotoBook Review 006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

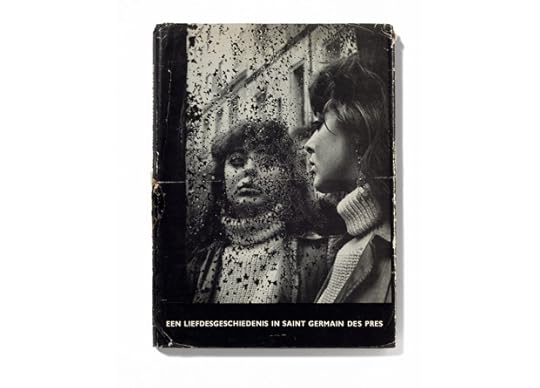

Ed van der Elsken

Love on the Left Bank

André Deutsch

London, 1954

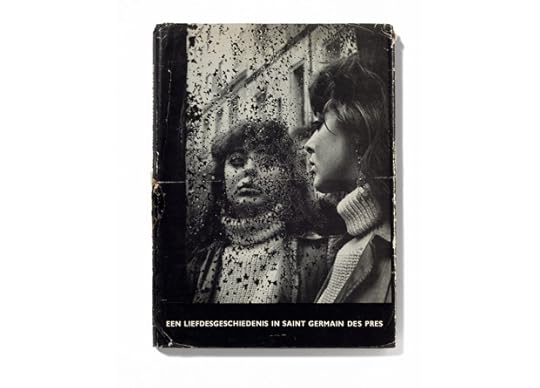

Ed van der Elsken’s Love on the Left Bank was the first present I received from the woman who is now my wife. We had not known each other long, so in retrospect her choice of gift seems almost telepathically inspired. I was not writing about photography then the way I do now, so I initially responded to the book purely as a work of visual poetry. It seemed a mirror of a world both real and created, actual and semimythical: a glimpse of the bohemian demimonde of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in the early 1950s, a place informed by the Beats as much as by Sartre and de Beauvoir.

Van der Elsken was instinctively drawn to one of the great characters of that time and place: Vali Myers, an Australian artist-in-exile who was friends with Cocteau and Genet and later became a muse for the young Patti Smith. (Myers was responsible for the lightning bolt tattoo on Smith’s knee.) Van der Elsken cast the long-haired, enigmatically beautiful, and mercurial Myers as the book’s main character, Ann, whose wild life he evokes through the nighttime streets and after-hours bars and jazz clubs of the Left Bank. The book’s fictional love story brings to mind the energy and anarchy of that lost time.

First published in 1954, Love on the Left Bank is a profane hymn to a time and a place, and to the people who created it in their own image. Among its real-life characters is Jean-Michel, a member of the collective Letterist International, to which the Situationist activist and thinker Guy Debord also belonged. (Apparently, the back of Debord’s head is visible in one photograph.) Van der Elsken snapped Jean-Michel as he instructed a girl how to “smoke hashish in the right way . . . the cigarette not held in the mouth, the smoke inhaled together with air from the cupped hands.” Here, fiction and reality, documentary and staged narrative meet, and one can sense the unruly beginnings of the youth culture of rebellion, rule-breaking, and left-wing activism that would so define the following decade.

As one gets older, one realizes that, as the musician Brian Wilson once told me in an interview, “everything is beautiful at the beginning.” Those words have haunted me in the long winter of global capitalism, where Debord’s “society of the spectacle” has become an unreal and relatively unquestioned reality. Love on the Left Bank now seems like a report back from another impossibly distant time when, to paraphrase Debord, it seemed reasonable to demand the impossible. It makes me feel I was born too late and in the wrong place. “I report on young, rebellious scum with pleasure,” van der Elsken once said. Who would not wish to have been one of those rebellious scum?

—

Sean O’Hagan writes about photography for the Guardian and the Observer, and is also a general feature writer.

The post PhotoBook Lust: Sean O’Hagan on Ed van der Elsken, Love on the Left Bank appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 13, 2014

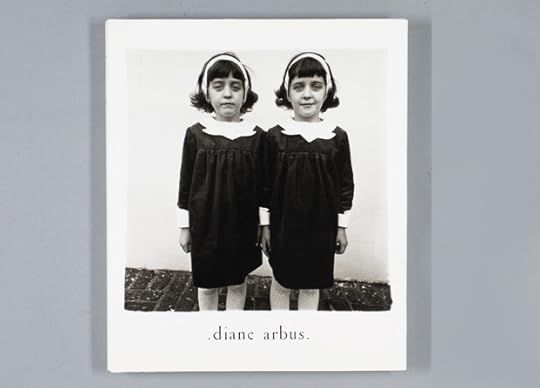

PhotoBook Lust: Laurel Nakadate on Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

This is part of the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in The PhotoBook Review 006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

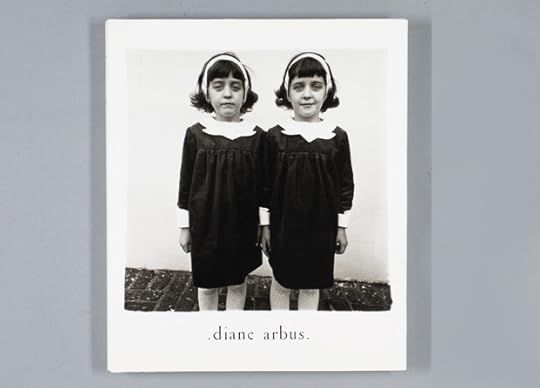

Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

Fortieth Anniversary Edition

Aperture

New York, 2012

Everything that needs to be said has already been said about this book, this record, this heartache, this brave account, this body of evidence. I didn’t choose to write about this book because I feel that I can say anything more eloquent than what has already been said. For example, on the inside flap of the fortieth-anniversary edition, John Szarkowski, Richard Lacayo, and Peter Schjeldahl say it all, with precision, humility, and compassion. So I will not try to tell you what this book means to the world. I will attempt to tell you what it means to me, or rather, what it meant to a fourteen-year-old me.

In 1990, I was a freshman in high school in Ames, Iowa. I had never held a genuine art book in my hands. It was Ms. Gugel, the art teacher, who changed that. A former student of hers, who’d moved to New York City, had mailed the Arbus monograph to her after seeing the posthumous retrospective at MoMA in 1972. And so: Arbus’s book was a message in a bottle sent from a giant, mythic city, somewhere in the East, very far from Iowa, and that message contained portraits so rich with ache and hopelessness and psychological high-wire acts and death defiance that after I turned each page and reached the end, I knew I would never be the same. I was obligated to go through the usual routine that day after seeing the Arbus monograph. But how could homeroom, pep rallies, and the eight periods of my high-school life mean anything after looking into the world of Arbus? How could I not make immediate plans to find my way to this world that she described? If someone else, some other kid from my town, had made it to New York and found this book and sent it back, how could I not try to get there too?

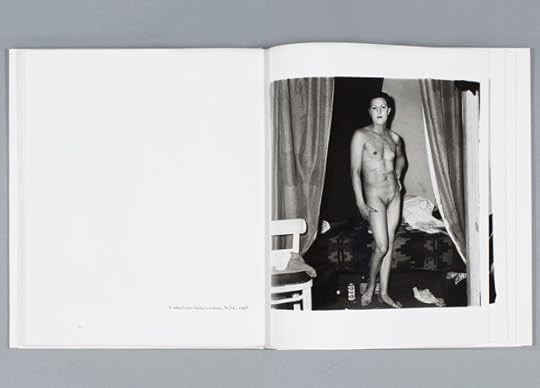

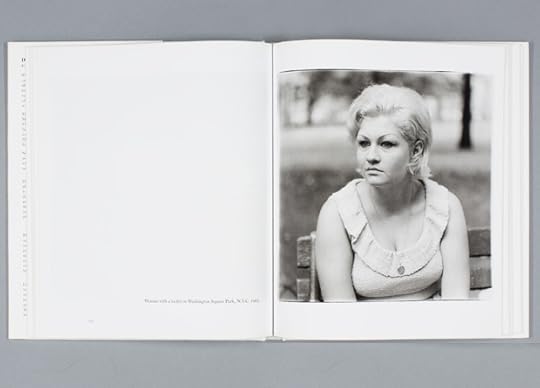

The young couple on the bench in Washington Square Park, the boy not really in love anymore but the girl still using the label, and all the babies are crying babies, the middle-aged women with their faces framed tightly and wrinkling in the sun, nudists in a living room on a sunny morning, a young Brooklyn family called a family only because that’s what you call two adults with children, and a woman with her baby monkey—it should be so funny this woman with this monkey, but it isn’t, and so it hurts more than it would have had we never expected happiness. How is it that Arbus is able to tell us all how much we want and how much we will have and will not have? And how does she manage it in the pages of one book, one monograph, bound after she was already gone? Had I never seen this book, I might never have made it to New York.

—

Laurel Nakadate is a photographer, filmmaker, and video artist based in New York.

The post PhotoBook Lust:

Laurel Nakadate on Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 12, 2014

Recap: Looking at Me, Looking at You, Looking at Us

Looking at Me, Looking at You, Looking at Us, an exhibition of photographs made by elementary and middle school students, and the culmination of the visual-literacy curriculum implemented by Aperture Community Educational Partnerships, was on view at Aperture Gallery from April 26 to May 3. The exhibit consisted of photographs and photobooks by students from the Grand St. Settlement and Hudson Guild Beacon Community Centers in grades four to eight. Over the course of the academic year, Aperture teaching artists introduced students to photographic techniques, vocabulary, and masterworks. The students were then asked to apply what they had learned to their own personalized photobook projects.

We were continually impressed with the imagination, wit, and adventurous natures of these young people once they had cameras in their hands. Several themes the students were especially interested in were street portraits, light, architecture, food, graffiti, and cityscapes.

A group of students stopped by Aperture Gallery during the exhibition, where they excitedly and proudly pointed out the photographs they had made. It was very “official,” in their words, to see their work on our gallery walls.

See the online exhibition here.

Learn more about Aperture Community Educational Partnerships.

The post Recap: Looking at Me, Looking at You, Looking at Us appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 5, 2014

PhotoBook Awards 2014: Open for Entries

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the 2014 edition of The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the book’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. We are excited to reveal the introduction of a third award category, Photography Catalogue of the Year, which joins the PhotoBook of the Year and First PhotoBook categories.

Call for entries is May 5 – September 12, 2014. Enter here.

The post PhotoBook Awards 2014: Open for Entries appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 2, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Olivier Richon on Paul Nougé, Subversion des Images

This is a web exclusive from the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in

The PhotoBook Review

006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

Paul Nougé

Subversion des Images

Les Lèvres Nues

Brussels, 1968

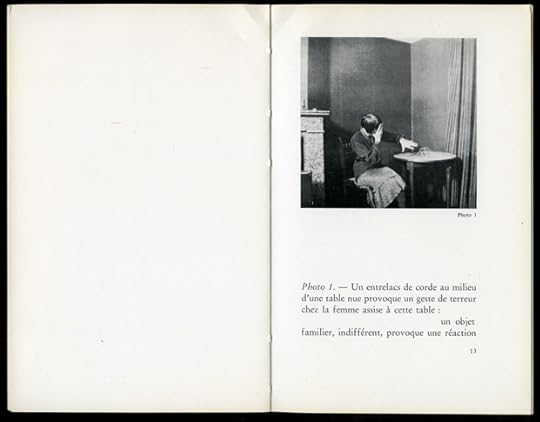

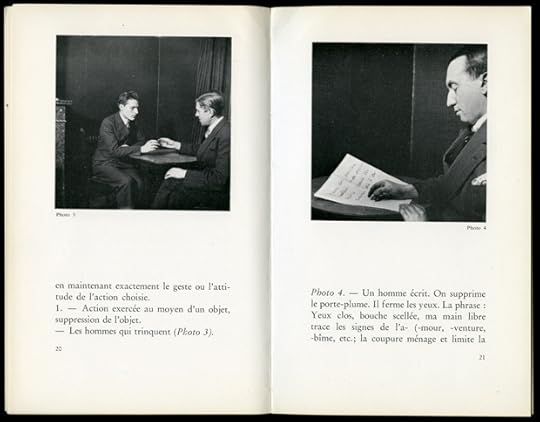

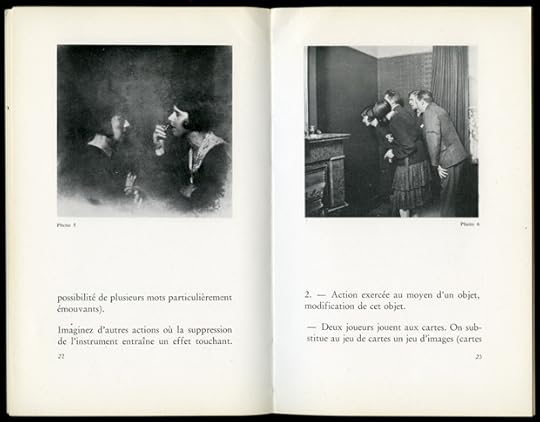

Paul Nougé was a writer, a poet, and an intellectual. The nineteen square photographs in this small book were all made over the course of three months, from December 1929 to February 1930, with a simple amateur camera.

I first discovered Subversion des Images, this Surrealist manifesto for a different use of photography, in an exhibition of twentieth-century Belgian art at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1991. I did not know at the time that the work had been produced as a book by the Belgian publishing house Les Lèvres Nues—“the naked lips.” No wonder then that these lips would encourage slips of the tongue, the pen, and the camera. Ten years later I finally managed to get a copy of the book, not without difficulty. It has now acquired the value of a fetish object.

My copy of the book still has its rice-paper wrap, so the cover looks like an image seen through frosted glass. The quality of the printing is basic; only the thickness of the paper indicates that it is a picture book as much as an essay. Although the work appeared in Surrealist journals, it was published as a book much later, in 1968. Only 230 copies were made.

For me, this book is exemplary for many reasons. It fits into a jacket pocket and its content is, as the title indicates, subversive. Photography is not here in the service of realism, documentary, or the morbid rituals of family life, but instead is in the service of dreamwork where image and language are intertwined, arguing for the rhetoric of objects.

Here, the camera is akin to a typewriter, used to produce a visual manifesto about the appearance and disappearance of objects. Nougé was a close friend of René Magritte, who figures in some of the photographs. He was also responsible for many of the titles of Magritte’s paintings. (For Nougé, as for Magritte, the title always came after the image, and therefore could always be revoked.) It is clear that there is a visual conversation going on between the two artists in Subversion des Images, more marked in some images than in others. All the pictures are scenes from inside a home. Most of the subjects look like they’re sleepwalking or hypnotized, and objects have an uncanny presence. This is the world of the inside, of interiority. Photography, in the words of Dalí, is conceived as a creation of the mind.

In these photographs, we have a condensed version of Nougé’s conception of the object: it must be separated from the thick universe of things. When objects are isolated and lose their functions they become signs, images; even something as banal as a piece of string can be turned into an incomprehensible thing. The same could go for words, which can be equally isolated from the mass of language that obscures their objectness. Alternatively, as with ellipses in a sentence, the object can be removed entirely, like the “glasses” in the photograph of two drinkers at a table: holding the air in the shape of two missing vessels, their hands appear to be living things, attempting to touch each other.

The back cover of the book shows an arm coming from behind an almost-closed door. The index finger points toward the edge of the frame, which cuts and isolates the visual field to turn it into an image. But this pointing also brings us back into the book, inviting us to read it again from the end—as if walking backward to get ahead.

—

Olivier Richon lives in London, where he is a professor of photography at the Royal College of Art. He is currently writing a book about a photograph by Walker Evans for Afterall Books’ One Work series.

The post PhotoBook Lust: Olivier Richon on Paul Nougé, Subversion des Images appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 30, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Brad Feuerhelm on Richard Peter, Dresden: eine Kamera klagt an

This is a web exclusive from the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in

The PhotoBook Review

006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

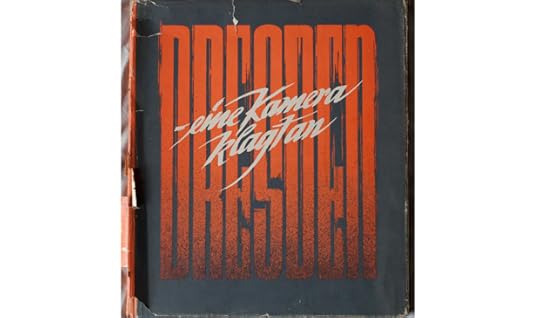

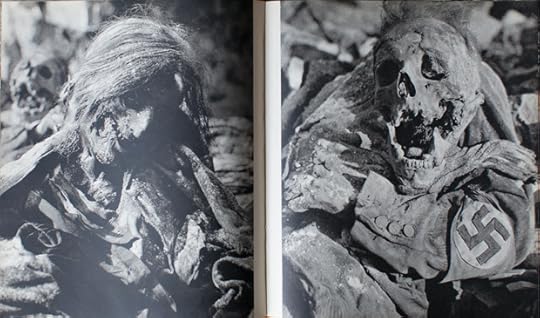

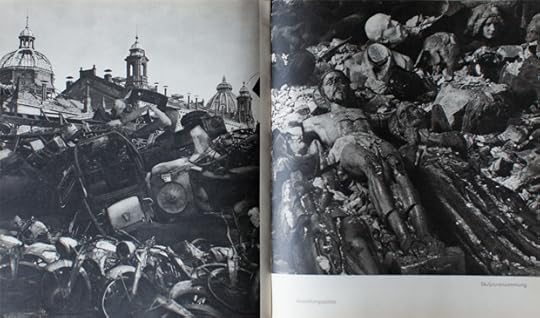

Richard Peter

Dresden: eine Kamera klagt an

Dresdener Verlagsgesellschaft

Dresden, Germany, 1949

I can imagine what it is to wake up in a city like Dresden the morning after being carpet bombed by Allied forces in 1945, and to understand much of what Richard Peter’s Dresden: eine Kamera klagt an may have felt like to create. This book, when I discovered it in Germany in 2004, sent me reeling with inexplicable loss, but also a longing, a desire, to speak and see through that same leveling dust. I couldn’t help it—couldn’t stop the thought that, if I am honest with myself . . .

I desire the end of all things; I desire to become an unholy spectator striding amongst incalculable ruins with my only companions gleaming at me through hollowed eye sockets, strained grins pulled taut from their last gasping breaths. It is this aesthetic dysphoria that I desire. I desire to walk as a seer through a sprawling forest of gloom.

I seek to enumerate and catalogue all that will never be again through my own eyes, seeing and recreating a taxonomy of that which can never be sought by the world at large, and, in doing so, to feel truly alive in a world rent asunder by flame and fury. To be the only entity capable of speaking in tongues, to ears that cannot possibly listen. My desire is not orgiastic; my desire is eschatological, illogical in a quest to understand the end of all things. Somehow I have been here before . . . and I know that I will be here again. In this ecstasy I am able to navigate a rebirth negated by truant hope.

—

Brad Feuerhelm collects, deals, and writes about photography. His first book, a volume of the SPBH Book Club, was published in 2012 with Self Publish, Be Happy.

The post PhotoBook Lust: Brad Feuerhelm on Richard Peter, Dresden: eine Kamera klagt an appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 28, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Guido Guidi on Paul Strand, Un Paese

This is a web exclusive from the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in

The PhotoBook Review

006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

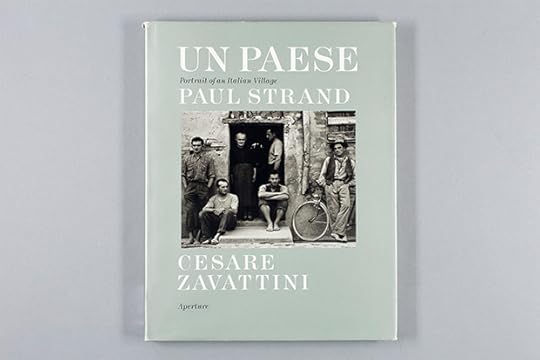

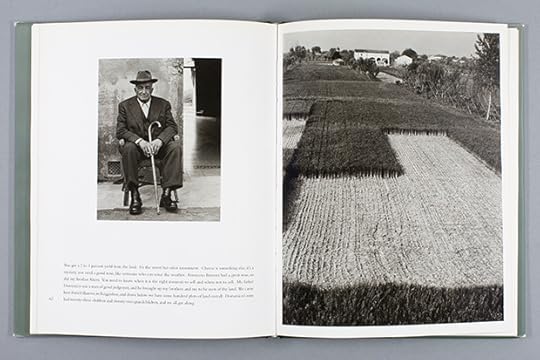

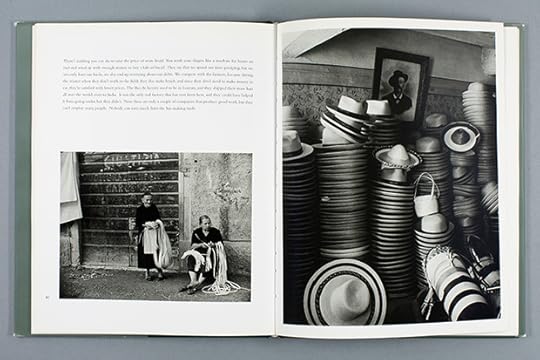

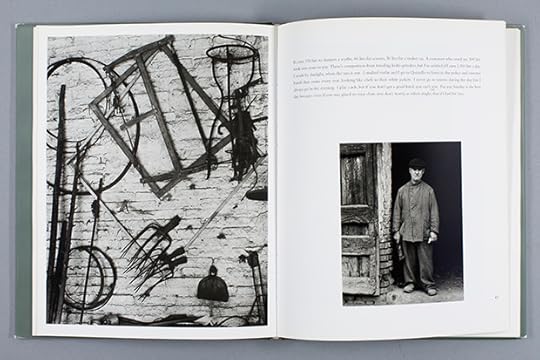

Paul Strand

Text by Cesare Zavattini

Un Paese

Giulio Einaudi

Milan, 1955*

Un Paese by Paul Strand was one of the first photobooks I ever looked at persistently. I remember that at school Italo Zannier had long spoken about it. It was published by Einaudi in 1955, and I was lucky enough to find a copy on sale for not that much at the end of the ’60s. What a pleasure to finally have a copy in my hands! The jacket has a photograph glued on a gray-green background, as was the fashion at the time. Underneath, there was the spartan cloth binding; inside, the coated paper was not too white, and the ink was greenish brown.

Strand looked after every single phase of the making of this book, from the creation of the dummy to the rotogravure printing. For him the book had to be a sort of “movie on paper,” and so the photographs follow one another as in a film, supported at times by short interviews by Cesare Zavattini that give voice to the people in the photographs.

I mostly didn’t read the text. I was all too interested in the “silence” of the photographs, in which the people were emanations of the places, and the face of things offered to me, as a gift of the page.

—

Guido Guidi (born in Cesena, Italy) is a photographer who has shown his work internationally, included at Centre Georges Pompidou and the Venice Biennale.

*Book pictured above is the English-language edition of Un Paese (Aperture, 1997).

The post PhotoBook Lust:

Guido Guidi on Paul Strand, Un Paese appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Mark Steinmetz: Photographing Civilization

On April 5 and 6, Mark Steinmetz led an insightful workshop at Aperture Foundation, grounded in the tradition of American photography. The workshop began with a seminar on the history of the medium, critically examining the works of Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Robert Adams, and Stephen Shore. Steinmetz highlighted composition, lighting, and thematic narratives, and shared many personal anecdotes from his experiences working with some of these photographers. He also presented his own photographs, discussing his experiences, inspirations, and publications. Each student was able to present his or her portfolio to the group and receive feedback related to the techniques and themes discussed in the lectures. It was a fun and enlightening weekend!

From the students:

“Mark is my favorite photographer, and having the opportunity to talk to and learn from him was an amazing experience.”

“Mark’s presentation of his own work and the presentation of other great photographers’ work enabled me to look at images that I was familiar with in a new way.”

The post Mark Steinmetz: Photographing Civilization appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 25, 2014

Artist Talk: James Bridle (Video)

On Tuesday, April 15, 2014, artist James Bridle joined us at Aperture Gallery to discuss his latest project, Dronestagram, featured in the Spring 2014 issue of Aperture magazine. Sourcing cartographic images and metadata from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, an independent news organization in the UK, Bridle posts on Instagram aerial views of the approximate locations of airstrikes carried out by the United States government in countries such as Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia.

Embracing the accessibility of social media, Bridle creates a visual record of the invisible war being waged overseas. Each caption details the casualties and location of the attack. This clever and chilling project has garnered a lot of attention; the Dronestagram account now has over 10,000 followers and has sparked debate over the moral and political implications of anonymous warfare.

View “James Bridle: Artist Talk” Part 2 and Part 3 on Vimeo.

The post Artist Talk: James Bridle (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers