Aperture's Blog, page 181

April 25, 2014

PhotoBook Lust

In putting together this issue, I reached out to a wide range of bibliophiles and artists and asked them to discuss their personal relationship with a specific photobook. I asked them not to approach this as a book review, but rather as a personal account of a photobook that had provoked (or still provokes) the feelings of lust, desire, or arousal. I was interested less in an intellectual engagement, and more in something that each person has been unaccountably drawn to: a book that has obsessed them, whose pages have been pored over, consumed, loved; a book that has been very significant to each person’s life, which brought them into a world they would like to be part of. The results range from covetous reactions to books that triggered new ways of thinking about photography, to those that inspired outright salacious responses. You’ll find these contributions contaminating the whole issue, wrapping themselves around and between pages—an uncontainable account of PhotoBook Lust.

—Bruno Ceschel, guest editor of The PhotoBook Review 006

Web exclusives

Ed Templeton on 61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler

Guido Guidi on Paul Strand, Un Paese (coming soon)

Brad Feuerhelm on Richard Peter, Dresden: eine Kamera klagt an (coming soon)

Olivier Richon on Paul Nougé, Subversion des Images (coming soon)

From the print edition

Vince Aletti on Peter Hujar, Peter Hujar

Justine Kurland on Nicholas Muellner, The Amnesia Pavilions

Anouk Kruithof on Justin James Reed, 2013

Adam Broomberg on Our Bodies, Ourselves

Lise Sarfati on Mike Kelley, Photographs/Sculptures

Lucas Blalock on Elmer Batters, Elmer Batters

Paul Kooiker on Boris Mikhailov, Case History

Colby Keller on Iron Eyes Cody, Indian Talk

Roxana Marcoci on Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach, Ringlpitis

Paul Graham on William Eggleston, Election Eve

Sean O’Hagan on Ed van der Elsken, Love on the Left Bank

Michael Mack on Collier Schorr, Jens F.

Laurel Nakadate on Diane Arbus, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

Ron Jude on Joachim Brohm, Industriezeit

George Pitts on Russ Meyer, A Clean Breast: The Life and Loves of Russ Meyer

JH Engström on Daido Moriyama, Bye Bye Photography

Mariah Robertson on photography instructional manuals

The post PhotoBook Lust appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin

Dear PhotoBook Review Reader,

You’ll find many of the following pages are guided by one particular idea as a loose organizational frame: the photobook and desire. For those of you who know guest editor Bruno Ceschel as the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy, a curatorial project committed to the celebration and study of the self-published photobook, you may also be aware of SPBH’s id-driven alter ego, Self Publish, Be Naughty, a series of monographs about love, lust, sex, and taboos. It is eclectically promiscuous in its approach to desire and, as is pointed out in The Photobook: A History, Vol. III (Phaidon, 2014), to photography itself. A giddy, mischievous ethos infuses most of Bruno’s projects, and this one is no different. His vision is ultimately utopian at its core, in which confession of our desires sets us free and connects us to communities of shared and overlapping interests.

This utopian bent is particularly appropriate as this is also the second time we will be launching the spring issue on the dreamy West Coast, during Paris Photo Los Angeles. Last spring, in issue 004, guest editor Charlotte Cotton gave us a blueprint for intertwining personal experience with intellectual analysis, a challenge which has been consciously picked up by Bruno and many of the contributors selected by him and his team. In “PhotoBook Lust” and other writings in these pages, you will find an unruly garden of thrills and delights, filled with books that can seduce us into taking them home for private enjoyment.

I was especially gratified to have the opportunity to engage Miyako Ishiuchi and Yurie Nagashima in a conversation about the ways the female body has been depicted in Japanese photography—both in their own work and in that of other photographers, some of whom have gained international recognition for their frank, possibly exploitative depictions of the eroticized nude. Also in this issue, instead of a standard Publisher’s Profile, Bruno has interviewed David Senior, bibliographer of the MoMA Library, about the increasingly blurred lines between publisher, designer, artist, and other once-discrete roles. In this interview, Senior proposes that one new application of the book form itself is as a self-run artist’s space, particularly as it applies to self-published works.

Finally, I’d like to bring attention to the launch of a new category of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. While it has become a bit of a truism that a “true photobook” is almost exclusively the authorship of an individual artist or editor, it became evident during last year’s jurying process that many excellent contributions to the field decidedly do not fall into the aforementioned framework, as they are focused more on the presentation of scholarship and curatorial thinking. We realized we ought to find a way to recognize these efforts to bring innovation and new knowledge to the world of photobooks. With this in mind, this spring we launch a new, third category of prize: Photography Catalogue of the Year. More details on this can be found here.

As always, we thank our guest editor and contributors (of whom there are so many in this issue!), whose ideas and words are the backbone of The PhotoBook Review. The collected wisdom and opinions of so many participants reshaping the landscape of the photobook today are continually inspiring to me, as they hopefully are to you, the PhotoBook Reader, as well.

—Lesley A. Martin

Publisher, The PhotoBook Review and Aperture Foundation book program

The post Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Editor’s Note: Bruno Ceschel

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #706 Bruno Ceschel / idealbookshelf.com

I was sitting in my doctor’s waiting room with my mom like I did every Wednesday when I was ten years old—I had developed an allergy to house dust and was getting weekly injections as treatment. From among the publications piled up in the waiting room that afternoon, I picked up one about maritime activities. I remember it like it was yesterday: suddenly, flipping through the book’s pages, I noticed a feature about a yacht sailing in a tropical sea with a crew of teenage boys. In some of the photographs the boys were naked, and in one photo in particular, you could see part of one of the boys’ pubescent genitals. It was probably the first time I had seen the cock of an older guy. That photo caused a hormonal earthquake inside of me that forced me to secretly rip those pages from their place and take them with me. I kept them for a very long time, hidden in my room.

That day, now nearly thirty years ago, I consciously encountered the power of desire and photography for the first time. Those carefully hidden pages offered me a portal to an otherworldly place of ecstasy, a place I didn’t know existed until then: a paradise that those photos made “real.” Those pages have long since disappeared, but for years they were my loyal companions, my promise to happiness. Those photographs were my only escape from a small conservative village in the Italian countryside.

Paradise often lies between the covers of (photo)books. The binary desire to have or to be is the key to revealing such a paradise to our own eyes. Desire is like those glasses needed to see a 3-D movie: without them, the film just looks dark and out of focus.

This issue of The PhotoBook Review endeavors to explore the nuanced relationship between pleasure, photography, and the photobook—a very powerful triangulation which has always been the foundation of my own interest in photography. (It is no accident that the organization I founded, Self Publish, Be Happy, uses happy and naughty as programmatic names.) As Lesley A. Martin mentions in her publisher’s note, I am indebted to Charlotte Cotton, a previous guest editor, and to her assessment that a meaningful creative culture has to take into account each actor’s personal experience.

The issue is organized as one would a big party. The contributors are a mix of friends and my ideal party guests, most of whom were invited to bring along a photobook that has been a tool of lust and arousal, or otherwise a giver of pleasure—from the platonic to the lascivious. The result, in the form of the feature “PhotoBook Lust” (including special web exclusives), is a cacophony of beautifully confusing, heartfelt personal testimonies mapping the idea of desire, in its many forms and inclinations. Such a knot of desires untangles to reveal a touching testament to our times.

Of course, it would be difficult not to look at the desire around the book as an object itself, and who better than photographer Todd Hido to talk about his own extensive collection of photobooks and what prompts him to possess them. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find editor Simon Bainbridge rallying for artists and publishers to create new digital forms for photobooks. He points toward a promised land that is, to many such as myself, hard to imagine. Such a promise is darkened by the question of whether the misfortune of digital editions so far can be attributed to their lack of tactile pleasure (and uncollectibility).

To further explore the relationship between the tangible and intangible, I asked artist Lorenzo Vitturi to produce a three-dimensional manifestation of his own idea of pleasure and photobooks for the publication centerfold. His photograph, titled Candyfloss Ballad (2014), is a naughty take on hide-and-seek, pleasure, and eroticism.

This issue of The PhotoBook Review is sublimely unresolved, confusing, and queering. The chaos of this photobook orgy is exciting and pleasurable. I feel it’s a slightly frantic but successful gathering, and I’m really grateful to all who decided so generously and carefreely to take part. (A special thank you to Joanna Cresswell, who assisted me in the development of the project.) If this issue cannot be conclusive in mapping the complex relationship between pleasure and the photobook, I hope that it prompts you, the reader, to reconsider your own relationship with books, freed from the idiosyncratic diktats of the collector market, art-world hype, and prevailing academic discourses.

Jacques Lacan wrote, “That the subject should come to recognize and to name his/her desire, that is the efficacious action of analysis. But it is not a question of recognizing something which would be entirely given, ready to be coopted. In naming it, the subject creates, brings forth, a new presence in the world.” In my conversation with David Senior, he praises the bravery and tenaciousness of the artist/publisher. I heartily urge such artists to think about the photobook as a catalyst for a new presence in the world—as a new way of thinking and living. After all, this could be paradise.

—

BRUNO CESCHEL is a writer, curator, and lecturer at the University of the Arts London. He is the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy (SPBH), an organization that supports and promotes the work of emerging photographers. SPBH has organized events at a number of institutions around the world, including at the Photographers’ Gallery, Institute of Contemporary Arts, and Serpentine Galleries, London; C/O Berlin; Aperture Foundation, New York; and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, among others. Ceschel is also the director of SPBH Editions, which has most recently published books by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Cristina De Middel, Mariah Robertson, and Lorenzo Vitturi. Ceschel writes regularly for a number of publications, including Foam, British Journal of Photography, and Aperture, and has also guest-edited issues of Photography & Culture and OjodePez.

The post Editor’s Note: Bruno Ceschel appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 17, 2014

PhotoBook Lust: Ed Templeton on 61 Pimlico

This is a web exclusive from the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in

The PhotoBook Review

006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

Bill Jay

Photographs by Henry Hayler

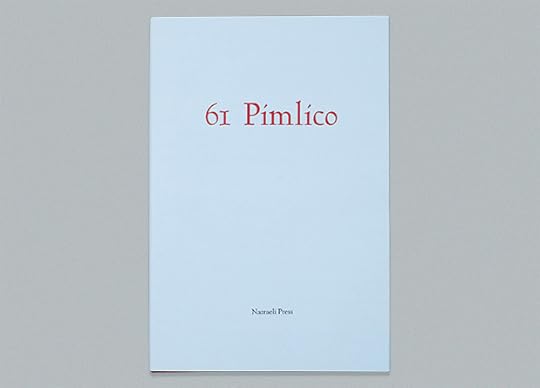

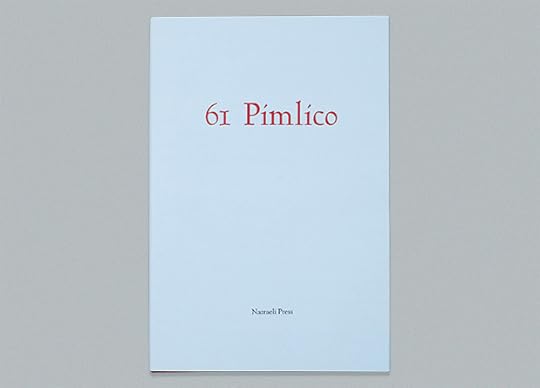

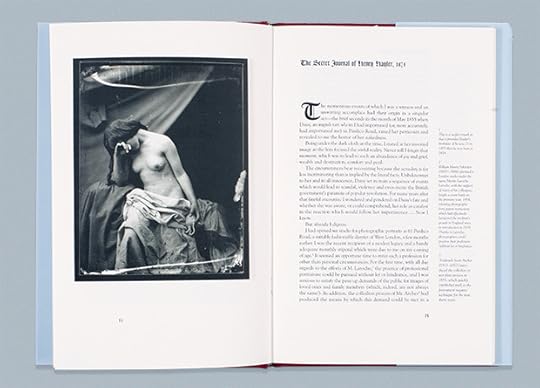

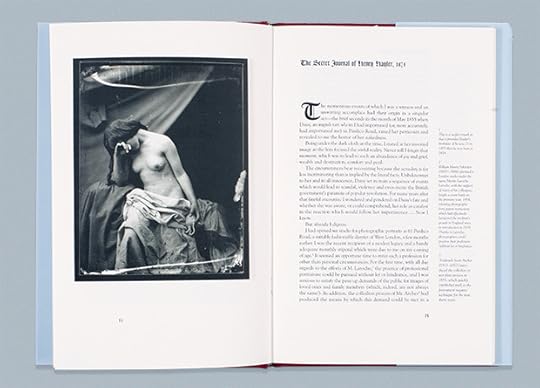

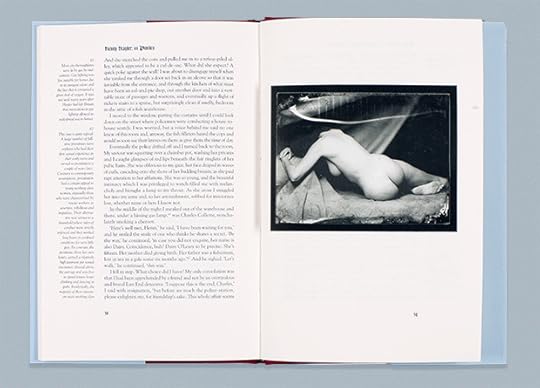

61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler

Nazraeli Press

Portland, Oregon, 1998

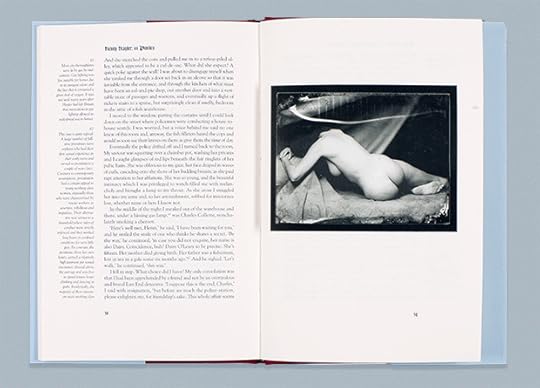

I was in Sydney, Australia in the year 2000, and while in the Museum of Contemporary Art on Circular Quay, I stumbled upon the beautiful volume 61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler. It’s the story of a Victorian-era photographer who shot nudes that were a scandal in his day; the photographs were mostly destroyed until Bill Jay found a precious few images hidden in an old journal at a car-boot sale in Maidenhead, England. I couldn’t stop looking at the images, devouring the story of how they were made and the sex Hayler was having with his subjects. They are reminiscent of E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville portraits, but the faces are all hidden or obscured with framing or a turn of the head, as if the sitter suddenly looked away as the shutter was released. Many of Hayler’s sitters, it turns out, were society ladies who wished to be photographed anonymously in the nude, to what purpose I do not know. There are only nine images handsomely tipped into the book, and each one is oozing with a sort of clandestine naughtiness, seen through eyes that are new with discovery of the female form and the pleasures of the flesh.

I would return to this book often back home in California; the images haunted me. They still do. There is so much sex and nudity available at the click of a button now—any act or type one could conceive of is there, if you only search—making these glass-plate negatives and the time and effort that went into each one a thousand times more erotic, in my opinion. The social mores surrounding the time in which they were created make these nude photos a special kind of contraband. They continue to cause an ache in my loins that cannot be found on the Internet.

—

Ed Templeton is a California-based artist, professional skateboarder, and the owner of Toy Machine skateboard company.

The post PhotoBook Lust:

Ed Templeton on 61 Pimlico appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

PhotoBook Lust: Ed Templeton

From the upcoming PhotoBook Review 006, we are featuring a web exclusive from the PhotoBook Lust section: Ed Templeton remembers 61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler, edited by Bill Jay. Below is a short intro to the PhotoBook Lust section of the PBR by guest editor Bruno Ceschel

In putting together this issue, I reached out to a wide range of bibliophiles and artists and asked them to discuss their personal relationship with a specific photobook.I asked them not to approach this as a book review, but rather as a personal account of a photobook that had provoked (or still provokes) the feelings of lust, desire, or arousal. I was interested less in an intellectual engagement, and more in something that each person has been unaccountably drawn to: a book that has obsessed them, whose pages have been pored over, consumed, loved; a book that has been very significant to each person’s life, which brought them into the world they would like to be a part of. The results range from covetous reactions to books that triggered new ways of thinking about photography, to those that inspired outright salacious responses. You’ll find these contributions contaminating the whole issue, wrapping themselves around and between pages—an uncontainable account of Photobook Lust.

—Bruno Ceschel

Bill Jay

Photographs by Henry Hayler

61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler

Nazraeli Press

Portland, Oregon, 1998

I was in Sydney, Australia in the year 2000, and while in the Museum of Contemporary Art on Circular Quay, I stumbled upon the beautiful volume 61 Pimlico: The Secret Journal of Henry Hayler. It’s the story of a Victorian-era photographer who shot nudes that were a scandal in his day; the photographs were mostly destroyed until Bill Jay found a precious few images hidden in an old journal at a car-boot sale in Maidenhead, England. I couldn’t stop looking at the images, devouring the story of how they were made and the sex Hayler was having with his subjects. They are reminiscent of E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville portraits, but the faces are all hidden or obscured with framing or a turn of the head, as if the sitter suddenly looked away as the shutter was released. Many of Hayler’s sitters, it turns out, were society ladies who wished to be photographed anonymously in the nude, to what purpose I do not know. There are only nine images handsomely tipped into the book, and each one is oozing with a sort of clandestine naughtiness, seen through eyes that are new with discovery of the female form and the pleasures of the flesh.

I would return to this book often back home in California; the images haunted me. They still do. There is so much sex and nudity available at the click of a button now—any act or type one could conceive of is there, if you only search—making these glass-plate negatives and the time and effort that went into each one a thousand times more erotic, in my opinion. The social mores surrounding the time in which they were created make these nude photos a special kind of contraband. They continue to cause an ache in my loins that cannot be found on the Internet.

—

Ed Templeton is a California-based artist, professional skateboarder, and the owner of Toy Machine skateboard company.

The post PhotoBook Lust:

Ed Templeton appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 16, 2014

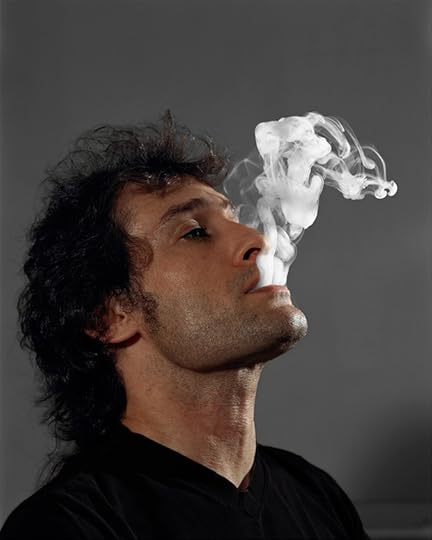

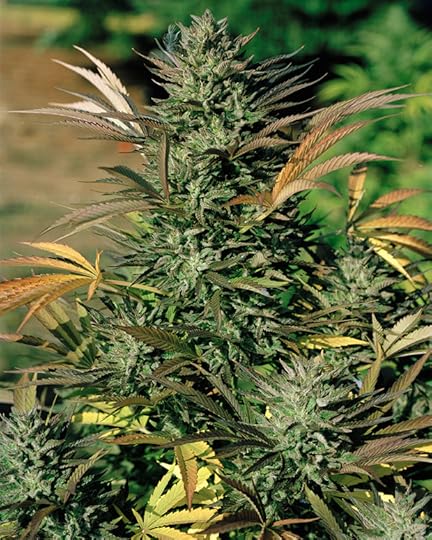

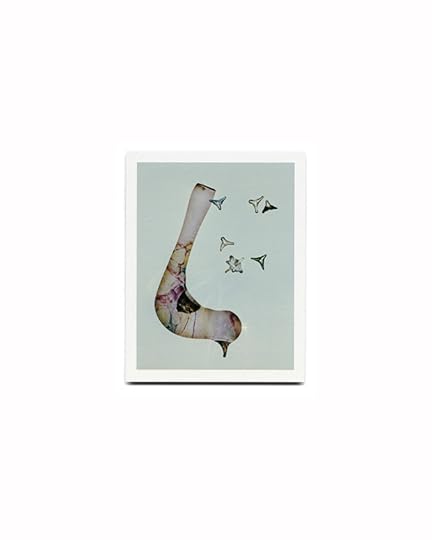

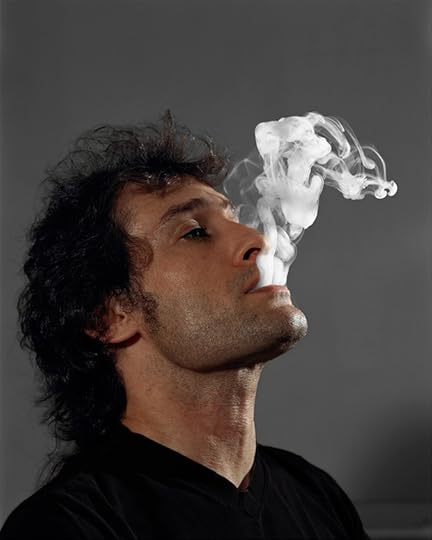

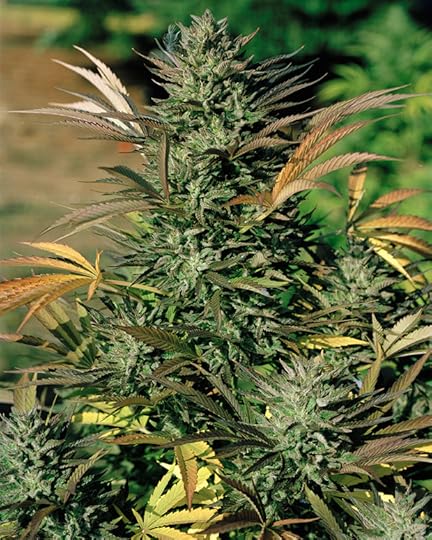

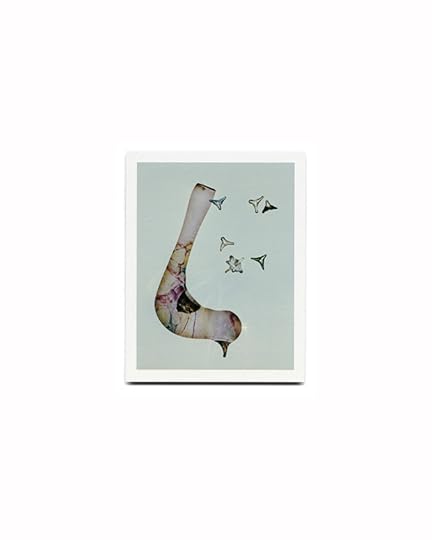

Pipe and Tie-Dye

A portfolio of images by Matthew Spiegelman from his new artist’s book Officioné.

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

In Matthew Spiegelman’s new self-published artist’s book Officioné the artist directs the lens of his large-format camera onto the world of Marijuana, presenting a lucid examination of the controlled substances’ contested mythos. The close-cropped photos in Spiegelman’s book focus in on the glass pipes, smoke, clothing, and the tropical plants themselves. Clean and precise, the photos do not attempt to get to the essence of what the drug is, but rather take a knowing look at the fascinating vernacular created by its users. Officioné comes in a hand-bound edition of 10, and though the book was published in an extremely limited quantity, it also lives as a photo-animated video here.

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

The post Pipe and Tie-Dye appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

From the Pipe to Exhalation

A portfolio of images by Matthew Spiegelman from his new artist’s book Officioné.

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

Image © and courtesy Matthew Spiegelman

In Matthew Spiegelman’s new self-published artist’s book Officioné the artist directs the lens of his large-format camera onto the world of Marijuana, presenting a lucid examination of the controlled substances’ contested mythos. The close-cropped photos in Spiegelman’s book focus in on the glass pipes, smoke, clothing, and the tropical plants themselves. Clean and precise, the photos do not attempt to get to the essence of what the drug is, but rather take a knowing look at the fascinating vernacular created by its users. Officioné comes in a hand-bound edition of 10, and though the book is made in an extremely limited quantity, it also lives as a photo-animated video here.

The post From the Pipe to Exhalation appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 14, 2014

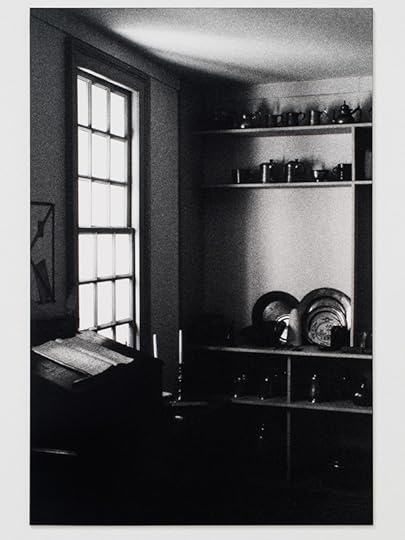

Into the Museum

Adam O’Reilly sits down with Pierre Le Hors to discuss his residency and exhibit at the Camera Club of New York, March 19-April 12, 2014.

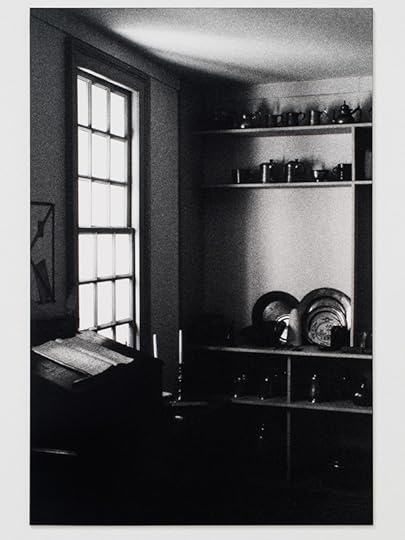

Pierre Le Hors, Vermeer 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

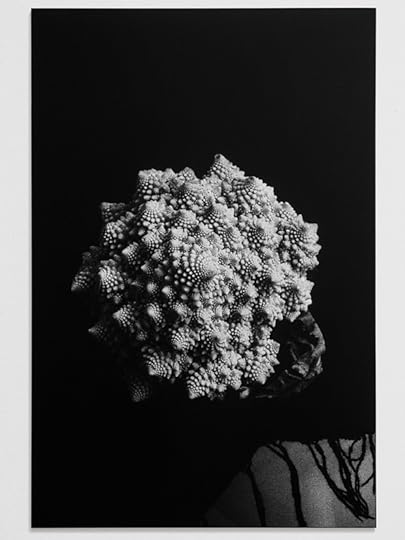

Pierre Le Hors, Romanesco 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

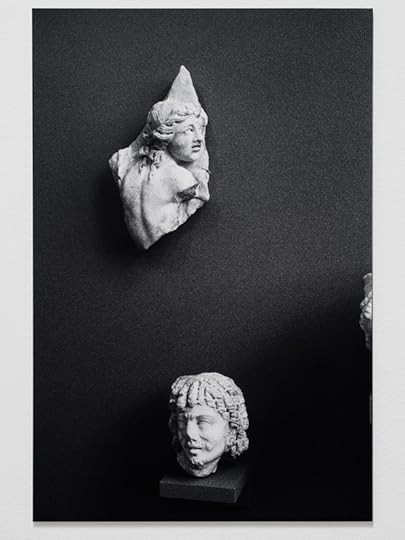

Pierre Le Hors, Regroupings 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

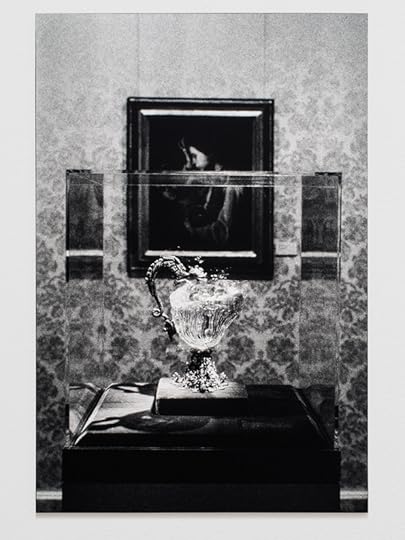

Pierre Le Hors, Ewer 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

As one of the 2013 Darkroom residents at the Camera Club of New York, Pierre Le Hors’ solo exhibition, Period Act, presents a selection of work he produced using exclusively CCNY’s darkroom. The exhibition uses the museum as its point of departure; specifically, it interprets the viewing experience one has when walking amongst hundreds of vitrines and displays at a museum like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Through a series of black-and-white interior photos, still lifes, studio shots, and photograms, Le Hors’ photographs invite the viewer to follow him in his research, poetic tangents, and darkroom mastery.

Adam O’Reilly: Where did the title of the show, Period Act, originate?

Pierre Le Hors: The title initially came from a photo of a period room at the Brooklyn Museum—in the show it’s the one that looks a bit like a Vermeer painting. That photo was a jumping off point for me, and from there I became interested in thinking about the experience of walking through a museum. The American Wing photos in the show were taken at the Met, and to me that museum in particular is a place where time and geography seem to collapse. The longer one spends in such a vast place, the more the objects on display become formalized, and their historical specificity becomes secondary. Of course you can read the wall text and become engaged with each object—but overall, the experience I am interested in is about considering all of these objects from different cultures and eras on a level playing field. I mean not only the art objects themselves, but also the display structures that house them, and the architecture of the museum itself.

AO: The American Wing photos are a formal investigation of the space, there is almost this total disregard for the objects on display in their composition.

PLH: Even though they are photos of objects on display, they are not about the American nature of these objects, or even just about the objects themselves. It’s more about trying to resolve that entire space—the objects, the glass vitrines framing the central courtyard, the vitrines framing other vitrines, the light that comes through the side windows, the way it reflects and plays off all those surfaces. I wanted to find out how that entire space could be activated in the pictures, and broken down on a formal level.

Pierre Le Hors, American Wing (1 – 10) 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

AO: I find it easy to walk through the Met and not look at anything specifically, just enjoying the objects piecemeal; taking some things in, ignoring others. I take it this is similar to your own experience?

PLH: To me that is indicative of wandering around a museum, when things are no longer specific, and become more about display and arrangements. There is pleasure in that. However, I realize this is tied to my own position and experience, I don’t mean to say that is true of everyone who walks through there. People go to museums for many reasons, of course—to see something specific, or sometimes to just be surrounded by these cultural artifacts.

Pierre Le Hors, Untitled 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

AO: Aside from being familiar with your work, my point of entry for this show was your press release for the show. The first paragraph is a reflection on the Met, and then in the next paragraph you refer specifically to a painting by Juan Dò, which in your show, you have a reproduction taped to the wall. Of all the paintings in the Met, why that one specifically?

PLH: When I started taking pictures at the Met, I noticed that painting in the background of one of my pictures. After sitting with that image for a while, I came back to the museum and actually looked at the painting in person. What is this painting? I was curious about it, so I found it on the Met’s website, in their catalog. It is a seventeenth-century Spanish painting, originally one of a suite of five paintings meant to depict the five senses, this one was the sense of sight [the Met only owns this one]. The girl in the painting is holding the mirror, and her other hand is up by her face, like she might be fixing her hair. It’s a strange pose. But the tension in the painting lies in her gaze, you can see her face in the mirror and she is looking off frame, to the right, at something we can’t see. This was interesting to me on multiple levels, first that this is a photographic device, this notion of “cropping” only existed only after photography. Secondly that the subject of the painting, ostensibly, is visual perception itself—in some way it seemed to focus the whole show around visual perception. I mean not only the black-and-white works, but also the color photograms which are given equal weight in the show. I don’t know if that comes through clearly, but I am ok with a little ambiguity, and leaving the viewer to bring the pieces together.

Pierre Le Hors, Slow Chance 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

Pierre Le Hors, In Time, Nico Line, and Still Life with To Go Cup 2014. Courtesy the artist and The Camera Club of NY

AO: The other black-and-white photos in the exhibit look like studio shots, how do they fit together with the Juan Dò painting?

PLH: The studio photos play off various art-historical or photographic conventions, but they’re a little messed up: the cauliflower image relates to photography’s use in documenting natural forms, but also has this psychedelic quality. There is a very staged renaissance-type still life with an extra coffee cup, something someone might have left on the set by accident. The picture of the cat jumping is somewhere between a staged shot and a “decisive-moment” instant, while the photo of the sculpture seems at first to be a studio picture but is actually taken at the Brooklyn Museum.

AO: The counterpoint in the show is the photograms that you made in the darkroom. Rather then giving the viewer’s eye something to rest on between the high contrast black-and-white photos, you’ve done the opposite.

PLH: I am interested in how the eye takes in those surfaces, what exactly they do visually, and how they push against the black-and-white photos, almost like noise or static. Your eye can’t fully rest on them, because there is no focal point and no depth, only surface and pattern. Each part of the image is allowed equal compositional weight, so the gaze is dispersed rather than focused, which enhances their flatness.

AO: In your artist statement on the CCNY website you write, “I want these images to speak to a certain loss of innocence for the young medium of photography, as it enters an age still grappling with notions of subjectivity and photographic truth.” I imagine you wrote that before you started the residency, but I was thinking about that statement while looking at the show where you approach a wide range of photographic styles.

PLH: This is not an original thought by any means, but we are in a phase where photography is both very self-reflective and self-reflexive. I think it’s easy to lose sight that photography is a young medium, it’s only been about 160 years if you want to trace it back the very beginning. And that feels like a long time to us, but it is an incredibly short time in relation to the span of pictorial representation. In photography’s infancy, the so-called “pictorialist” photographers were referring directly to painting, a system of representation they were familiar with. That early period seems so fertile with ideas and is still interesting territory to explore, but at the same time we are no longer so naive. Obviously, photography has totally diversified—it’s everywhere at once. I suppose I want to deal with photography’s role as a system among many others. But I don’t think we are at any end point, quite the contrary: we are only contributing to the medium’s language and long history.

—

Adam O’Reilly is the Online Editor at Aperture Magazine.

The post Into the Museum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 11, 2014

2014 Guggenheim Fellows Announced

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, from the series Notion of Family, 2008

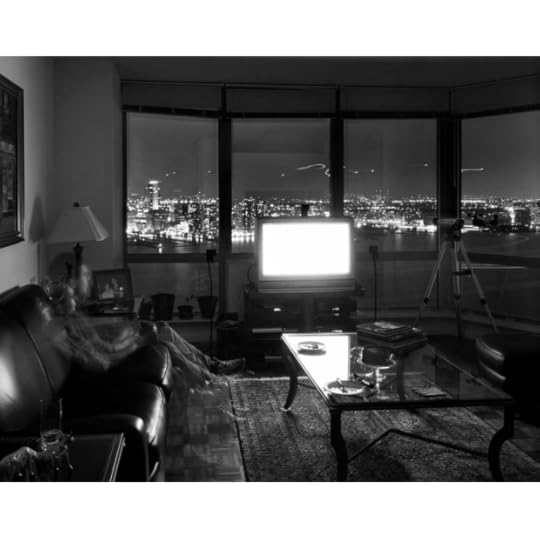

Matthew Pillsbury, Tanya and Taj, CSI Miami, November 25th 2002 10-11pm, from the series Screen Lives

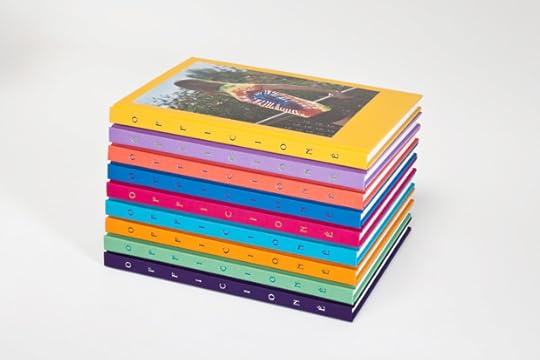

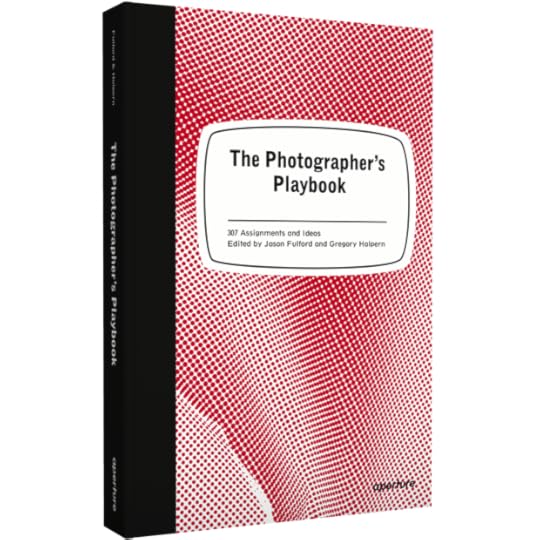

Cover, The Photographer’s Playbook: 307 Assignments and Ideas, edited by Jason Fulford and Gregory Halpern

From This Equals That, by Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin.

From This Equals That, by Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin.

Aperture would like to congratulate all of the recently announced 2014 Guggenheim Fellows! We are especially excited that four of this year’s fellows have recently published or will soon publish books with Aperture: Matthew Pillsbury, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jason Fulford, and Gregory Halpern.

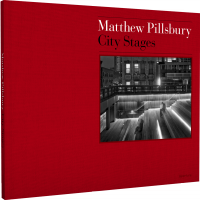

In Fall 2013, we published Matthew Pillsbury’s first monograph City Stages, and last month exhibited same body of work at the Aperture Gallery.

LaToya Ruby Frazier was a Aperture Foundation Portfolio Prize finalist in 2006, and we will be publishing her first book The Notion of Family in Fall 2014.

In June, we will be releasing The Photographer’s Playbook: 307 Assignments and Ideas edited by Jason Fulford and Gregory Halpern. See more upcoming Aperture titles here.

And in Fall 2014, we will be releasing Aperture’s first photobook for children, This Equals That, by Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin.

— City StagesMatthew Pillsbury’s first monograph City Stages captures the vibrancy of urban landscapes in large-format, black-and-white photographs.

City StagesMatthew Pillsbury’s first monograph City Stages captures the vibrancy of urban landscapes in large-format, black-and-white photographs.

$65.00

The post 2014 Guggenheim Fellows Announced appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 10, 2014

After Monet’s Garden

Aperture spoke with Miranda Lichtenstein about her upcoming exhibit of Polaroids on view at the Gallery at Hermès, April 11–May 5, 2014

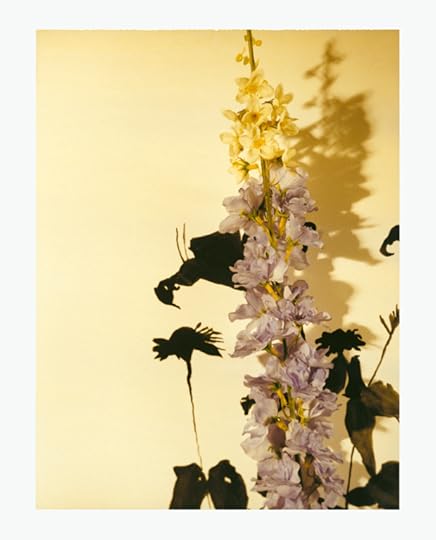

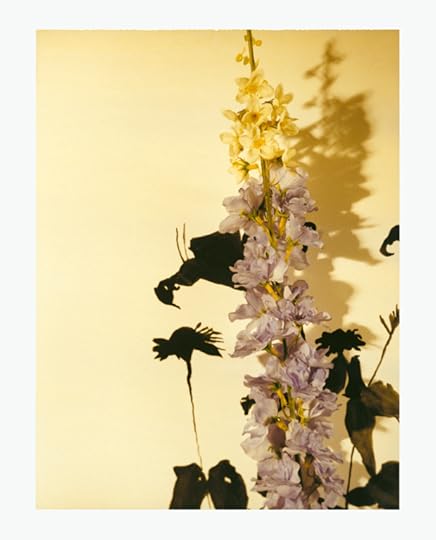

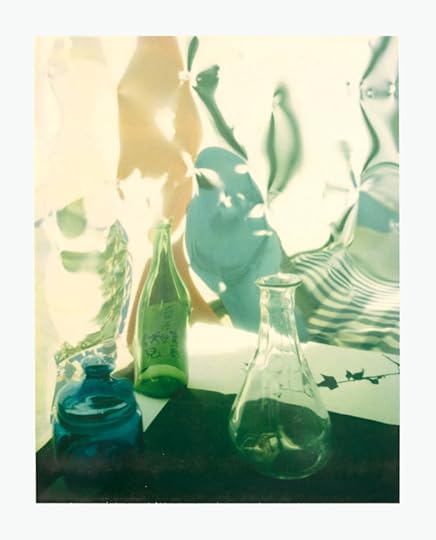

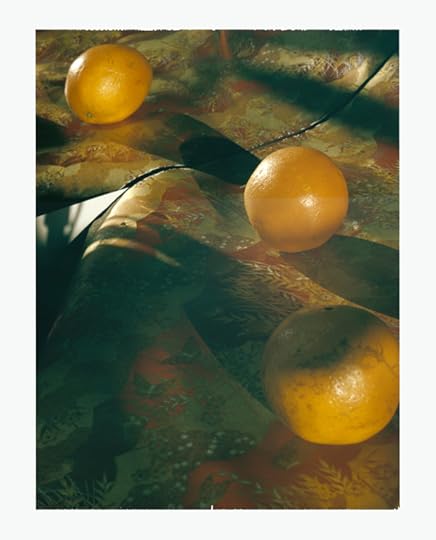

Miranda Lichtenstein, Steep Rock #2, 2006

Miranda Lichtenstein, Untitled #15 , 2002-2005

Miranda Lichtenstein, Ito #5 , 2008-2009

Starting tomorrow, April 11, Miranda Lichtenstein presents a career-spanning exhibit of her Polaroids at the Gallery at Hermès. Culled from eleven years of residencies all over the world, Lichtenstein’s photographs in the show are reflective of her surroundings, capturing the light and shadows of each locale using the serialized format of the Polaroid camera. Aperture caught up with the artist to discuss the editing process, and the self-discovery that resulted from considering a decade’s worth of images.

Aperture: How did this exhibition and collaboration with Hermès begin?

Miranda Lichtenstein: The exhibition was put together by Cory Jacobs, whom I’ve know for years. I had been to a number of the shows she has curated at the Hermès gallery. She approached me about doing a show a year ago; she had seen some of my Polaroids at the Hammer Museum in 2006. I thought Cory’s idea to look back at my Polaroid work over the past eleven years would be a great opportunity, and I was also interested to show in a space that is dedicated to photography, a new context for me. We decided that I would go through my work from the very beginning, when I first start shooting with a 4-by-5 Polaroid back, up until the present.

A: What prompted you to first use the Polaroid camera in your work?

ML: It began with a residency at Giverny, which was the first time I shot 4-by-5 film. Roe Ethridge gave me his 4-by-5 with a Polaroid back to take with me to France. I shot with that to learn how to shoot 4-by-5 film, as a test. The more I shot,the more I became interested in considering the Polaroid as the final object.

A: This exhibit is a departure from the non-indexical photographs you made for last solo exhibit at Elizabeth Dee in 2010. How do the Polaroids in this show relate to the rest of your work?

ML: There are a few images in the show that are Polaroid versions of the suites I showed at Elizabeth’s. However, that exhibition does differ; it was a great mix of scale and genre. I was exploring different strategies of image making, which involved distorting or refracting the images. I would say that approach is in play now as well; all the images deal with shadow play, refracted light, and elements of misrepresentation.

Miranda Lichtenstein, Civitella #5, 2009

A: The photos in the exhibit are from your travels and residencies over the years—are they a response to those different environments?

ML: Yes, it has a great impact. There is a clearer formal thread as the photographs are all still lifes, but I am definitely responding to the environment. I use the light in each place, and shoot using what’s around me. In Giverny, where the whole project began, I was pulling the clipped plants and flowers the gardeners cut at the end of the day and bringing them into the studio. In Japan, I discovered washi paper, and used it to make the paper screens I shot my compositions through.

A: It must have been a long editing process, going over eleven years of work. What is it like to see all this work in one place?

ML: It’s exciting. When I looked at the work from 2006, I realized both how much it’s had evolved and what consistencies exist throughout. The first Polaroids that I shot in Monet’s Garden were made thinking about how to photograph those ubiquitously photographed things in a different way. The newest works are entirely abstract and don’t deal with place at all in the same way. But it’s been interesting to see how I have worked with light and shadows throughout. I hadn’t considered it all together before. My own trajectory is much more clear to me now.

A: You mentioned there is new work in this show, can you describe it to us?

ML: The new work for the show is made from the screen-shadow photographs that I have been shooting for the past few years. I used the Polaroid to photograph my current digitally shot work, making a one-of-a-kind image of something out of something infinitely reproducible.

-

The post After Monet’s Garden appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers