Aperture's Blog, page 183

March 15, 2014

Robert Heinecken: Paraphotographer

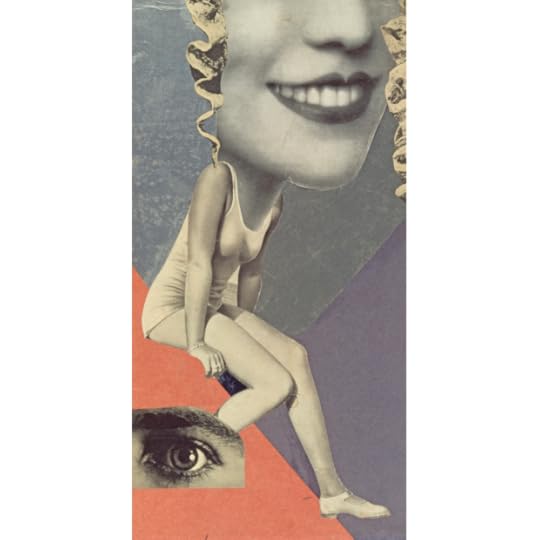

Robert Heinecken. Cybill Shepherd/Phone Sex. 1992. The Robert Heinecken Trust, Chicago; courtesy Petzel Gallery, New York. © 2014 The Robert Heinecken Trust

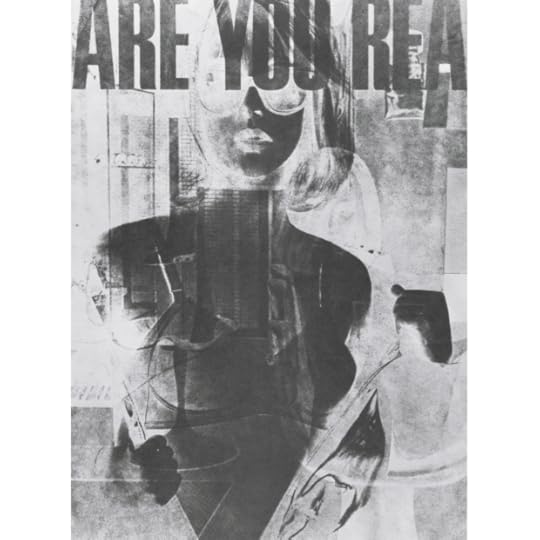

Robert Heinecken. Are You Rea #1. 1964–68. Collection Jeffrey Leifer, Los Angeles. © 2013 The Robert Heinecken Trust

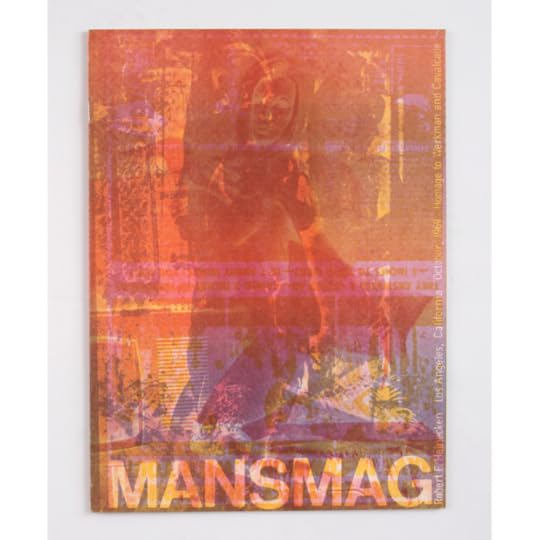

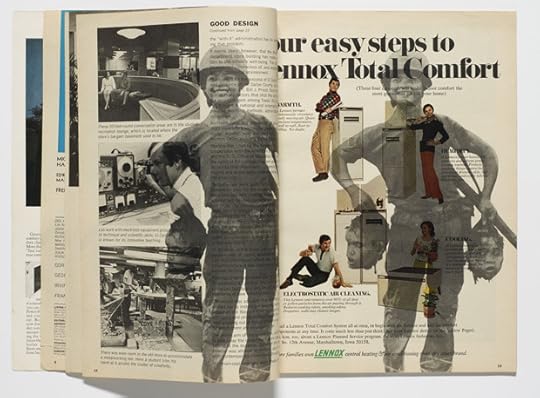

Robert Heinecken. Periodical #5. 1971. Collection Philip Aarons, New York. © 2014 The Robert Heinecken Trust.

Los Angeles-based conceptualist Robert Heinecken (1931-2006) worked primarily with photography but rarely used a camera. His cross-disciplinary work employed found images culled from mass media that were then reanimated through a variety of materials and techniques—gelatin-silver prints, collage, photo-sculpture, canvases covered with photographic emulsion, among them. A self-described “paraphotographer,” Heinecken’s expanded notion of photography is evident in his oft-cited comment: “The photograph is not a picture, but an object about something.” A comprehensive exhibition of Heinecken’s output, spanning the early 1960s through the 1990s, has just opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Aperture asked artist Arthur Ou to speak with Eva Respini, curator of Robert Heinecken: Object Matter, about this restless artist’s pioneering work and how his capacious definition of photography feels especially relevant today.

—The Editors

Arthur Ou: Why a Robert Heinecken show now?

Eva Respini: I realized that there hadn’t been a large-scale Heinecken retrospective on the East Coast since 1976, at the George Eastman House. He’s certainly been in group and gallery shows. He’s one of these figures with a cult following. But there are many people that don’t know his work, especially on the East Coast. It seemed like a good opportunity to show the larger scope of his career. Even if people know some of the work, they certainly don’t know everything.

AO: His career overlaps with many other art historical movements, such as the Pictures Generation. Can you speak to those connections and how his influence may have been delayed? Are you trying to bring his work into the present discourse on image making?

ER: Yes, I definitely am, or I do hope that the show will bring his practice with images more into the dialogue of contemporary art. In the Los Angeles area he’s known because of his legacy in teaching, which is very important, but I think where people don’t know him is in the realm of contemporary art. A lot of what he was doing in terms of using found images from magazines, newspapers, and television, certainly predated what we now call the Pictures Generation, but it also came out of the context in which he was working, post-Pop in Los Angeles, under the specter of the film industry. He certainly wasn’t alone. Think of Wallace Berman. You can go even further back to Warhol and Rauschenberg.

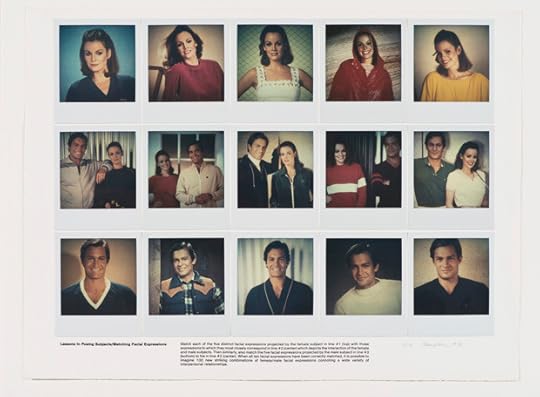

Robert Heinecken. Lessons in Posing Subjects/Matching Facial Expressions, 1981.

© 2014 The Robert Heinecken Trust

AO: What kind influence did he have on his students and the Los Angeles photography community?

ER: I think he was a huge presence. He was a deeply respected teacher. He was also an outsized personality and, from anecdotal accounts, a gregarious kind of guy. And I think it’s a testament to him that his former students are diverse in their practice; he didn’t just turn out many Heineckens. He seemed to encourage critical thinking about images, but that didn’t necessarily mean working in the way that he did. In fact, many of the students (especially the early ones) that I spoke to weren’t even aware of his practice and how pioneering or experimental it was (that he basically never made his own images, or used a camera in the traditional sense). Now, of course, things are different with access to the Internet; everybody knows immediately what you’re doing.

. Robert Heinecken. Periodical #5, 1971. © 2014 The Robert Heinecken Trust

AO: What was it like working with his archive? Was it challenging to construct a narrative that would make sense as a portrait of an artist?

ER: Well, it was really fun, sort of like archaeological work. But it was certainly a challenge, because one of the things that defined how Heinecken thought about making artwork was his training as a printmaker. All of his work exists in multiple iterations: one set of images were made as lithographs, then he would make them as gelatin-silver prints, then he would use the same source material and put that on photo emulsion on canvas, then he would use some of that as a preparatory work in collage form, and it goes on and on. So the challenge was deciding, well, what is the work?

And after some time, I realized that’s actually the wrong question to ask about Heinecken. He wasn’t an artist who would make one masterpiece, one that is clearly the work that we should have in the show. Obviously, we have very important works in the show that were influential in their time and continue to be influential now, but he was very iterative in his thinking and art-making; there are moments in the exhibition where we also accumulate a number of works that are related, where you see this iterative process and see him literally working through different materials. It is a way of working that was very much against the fine-art tradition of photography. If you think about that tradition and giants of West Coast photography, like Edward Weston or Ansel Adams, there is one master print. Heinecken worked completely against that idea.

With this realization, my work became less challenging. But there’s a lot of material out there and he was very prolific, working until the end of his life, even though he was ill. It’s amazing how much he produced.

AO: Variation, or multiple iterations of one work, seems to connect with our digital experience of photographs now.

ER: It’s a very contemporary idea that an image can be anything and be translated into any medium. Now we think, “oh yeah, it’s an image on my phone, it’s an image on my screen, it’s an image on the wall, it’s an image in a magazine.” He was just thinking of photography in the mediums of his time period. But the attitude, I think, is utterly contemporary.

Robert Heinecken. Figure in Six Sections, 1965. © 2014 The Robert Heinecken Trust

Installation view, Robert Heinecken: Object Matter, The Museum of Modern Art, March 15 – September 7, 2014. Photograph by Jonathan Muzikar. © The Museum of Modern Art.

AO: Throughout his career he was continually drawn to the female figure. Could you speak about that aspect of his work?

ER: When you see the whole body of work this is a consistent thread, not just the female figure but female sexuality. He was very interested in addressing sexuality in mass media and pornography, and how sex was basically used to sell practically anything. In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, his use of pornographic material becomes quite problematic and he was attacked by a number of feminists. Martha Rosler famously dismissed his work as “pussy porn.” There was a push back to his brazen use of the pornographic image. Even though he intended it as a critique, it wasn’t necessarily read that way. Hopefully, this show will be an opportunity for us to reassess that work. Our relationship to pornography is now very different than it was, even in the ‘80s, just because pornographic images are so much more widely available. And when I look at the images he was using, they seem very tame by today’s standards. In conjunction with the show, we’re having a panel on art and pornography. I’ve invited a number of artists who have dealt with related issues in their work to speak, and I plan to be quite open about my own issues with Heinecken and the subject, which is not 100% resolved for me.

AO: There will be interesting overlaps with the Heinecken show and MoMA’s two concurrent shows: the retrospective exhibition of Sigmar Polke, who worked across media, including photography, and A World of One’s Own: Photographic Practices in the Studio, Quentin Bajac’s survey exhibition of photographers working in the studio environment.

ER: We’re all looking forward to having all three on view. It’s great when these things happen, and they’re not always planned. Schedules in the museum are a very complicated thing. But when these synergies happen, it’s really great, because looking at Heinecken with Polke, it’s sort of what I was saying in the beginning here, where what I hope the show will do is to place Heinecken within a larger discussion of art since the ’60s.

—

Arthur Ou is Assistant Professor at Parsons the New School for Design.

The post Robert Heinecken: Paraphotographer appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 10, 2014

Live Stream: Bearing Witness, hosted by SFMOMA

Given the power and pervasiveness of photography in both art and everyday life, what is the significance of the rapid and fundamental changes that the field is undergoing? How have social media, digital cameras, and amateur photojournalism altered the way photographs capture the everyday, define current events, and steer social and political movements? How have photographers responded to these shifting conditions, as well as to the new ways in which images are understood, shared, and consumed? How have our expectations of photography changed?

These questions, central to the conversations presented in the current issue of Aperture magazine, “Documentary, Expanded”, will be explored this weekend during a one-day symposium hosted by SFMOMA, assessing the ways in which photography matters now more than ever.

“Bearing Witness”, organized by Erin O’Toole, SFMOMA associate curator of photography and Dominic Willsdon, SFMOMA Curator of Education and Public Programs, will be streaming live from the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Theater, Sunday, March 16, 2014, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Participants include Pete Brook, editor of prisonphotography.org, blogger for Wired, freelance writer and curator; Mike Krieger, cofounder, Instagram; Benjamin Lowy, photographer; Susan Meiselas, photographer, Magnum Photos; Margaret Olin, senior research scholar, Yale University; Doug Rickard, artist and founder of americansuburbx.com and theseamericans.com; Kathy Ryan, director of photography, The New York Times Magazine; Zoe Strauss, artist, Magnum Photos; and additional participants to be announced.

Tune in on Sunday for a free live stream of the sold out event (RSVP to add your name to the waitlist), and follow the conversation on Twitter with #bearingwitness.

—

The Spring 2014 issue of Aperture magazine, “Documentary, Expanded”, guest edited by Susan Meiselas, is now available. Aperture 214$19.95

Aperture 214$19.95

The post Live Stream: Bearing Witness, hosted by SFMOMA appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Subversive Desires

Kleine Sonne (Little Sun), 1969. Landesbank Berlin AG

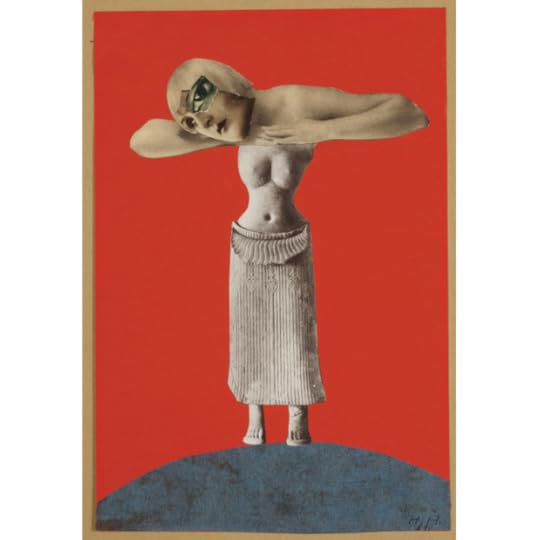

In the early twentieth century, photo and text snippets could be found everywhere, from film posters and political propaganda to magazine covers and artworks. Dadaists were most taken with intervening with photography specifically: photomontage was the closest thing to visual anarchy and in their eyes, the perfect tool for satire and social commentary. With so many artists mocking society with scissors and scalpels, what makes the photo scraps of German artist Hannah Höch so radical, even now, ninety-odd years later?

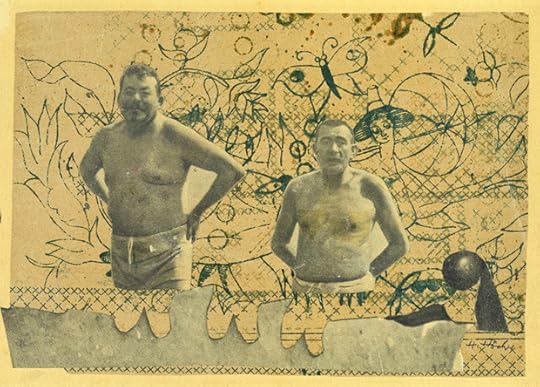

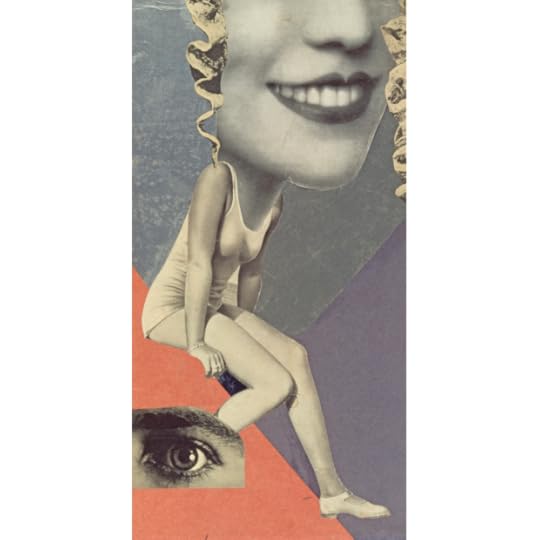

As the Whitechapel Gallery’s outstanding retrospective makes clear, she too was a provocateur, intent on destabilizing dominant viewpoints and opinions: she took aim at bankers’ collusion with the military and ridiculed politicians. In Heads of State (1918–20), Weimar president Friedrich Ebert is seen in trunks at a fantasy beach resort; in Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919–20), she fuses his head with the body of a topless female performer. While fellow Dadaists treated figures in a more forensic, impersonal manner, Höch’s delicate assemblages have people at their center, and addressed especially women and their role in society. Collage was her act of liberation: images of women in traditional feminine roles were rescued from fashion weeklies and given subversive desires and identities. Her most challenging series, From an Ethnographic Museum (1924–30), questioned narrow definitions of beauty by mixing together pale and dark-skinned bodies (although her gleeful appropriation of tribal objects demonstrates an uncomfortable fascination with exoticism).

Staatshäupter (Heads of State), 1918-20. Collection of IFA, Stuttgart

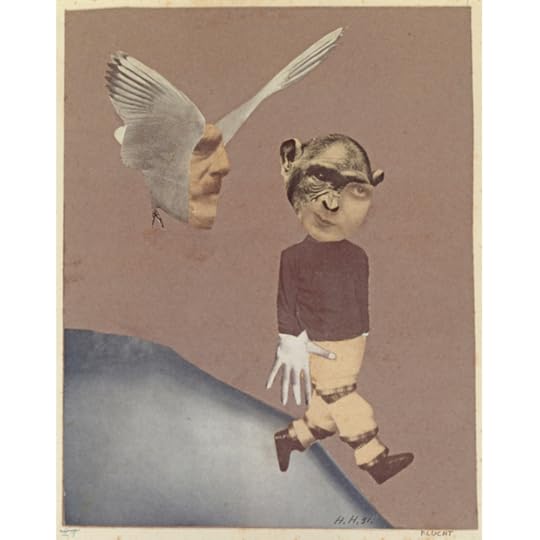

Feeling and emotion in Höch’s work also set it apart. Yes, there’s humor, particularly in her more Surrealist human-animal hybrids. But many of her figures from the ’20s and ’30s possess a melancholy air, their large, out-of-place eyes (one of Höch’s favorite body parts) full of longing and life-weariness. The many screaming faces she assembled convey an acute sense of anxiety and desperation. It’s easy to trace a lineage from Höch to contemporary photo-compositors like John Stezaker and Wangechi Mutu.

Although her work was reappraised during her lifetime, none of the recent retrospectives have taken place in the United Kingdom, where many male avant-gardists of the 1920s have been the subjects of recent major solo exhibitions (Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Alexander Rodchenko, Kurt Schwitters, and Theo Van Doesburg among them). Indeed, had some of Höch’s male Dada colleagues had their way, her work would have been totally forgotten: the artist herself recalled how they often regarded her as a “charming and gifted amateur” (Schwitters and Van Doesburg were the exceptions). Many, including rather shockingly her one-time lover Raoul Hausmann, excluded her from their memoirs of the Dada years. “A good girl” was Hans Richter’s patronizing description while George Grosz and John Heartfield opposed her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair in 1920. She responded with her largest photo collage, at 44.9 x 35.4 inches (114 x 90 cm), Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic (1919–20), where the heads of Grosz and fellow Dadaist Wilhelm Herzfelde appear skewered onto women’s bodies. The one disappointment of the show is that only a small study of this massive work is on view.

Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party), 1936. Collection of IFA, Stuttgart.

Ohne Titel (Aus einem ethnographischen Museum) (Untitled [From an Ethnographic Museum]), 1930. Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. Photo: courtesy of Maria Thrun.

Ohne Titel, aus der Serie: aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Untitled, from the series: From an Ethnographic Museum), 1929. Federal Republic of Germany - Collection of Contemporary Art. Image: bpk / Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Jörg P. Anders.

Rohrfeder Collage (Reed Pen Collage), 1922. Landesbank Berlin AG

The Whitechapel exhibition makes clear that Höch was not interested in photomontage as a means to an end, but as a craft, “a new magical territory” that she experimented with throughout her life. In 1934, as many artists abandoned the technique, Höch created a long, loose personal collage of sorts called Album. This scrapbook is one of the exhibition’s highlights, including expected motifs such as posed starlets and distorted body parts, but also architectural forms and aerial landscape views that demonstrated her growing interest in abstraction.

Of her work in the post-war decades it is not her abstract collages but the psychologically charged fantasies, often made with images of nature or everyday household objects, that are most beguiling: a flying sea serpent made of photographs of leaves, images of water lillies soaring through the sky like alien spaceships. Flight and escape were perpetual concerns. Höch spent the war living as a recluse on the outskirts of Berlin hoping that the Gestapo would never discover her hidden collection of misshaped women, dreamy beings who had no place in Nazi Germany. After seeing her world fall apart, she built strange, imaginary replacements, testaments to her unwavering faith in the power of art to unsettle, and her belief that you should “never keep two feet on the ground.”

Flucht (Flight), 1931. Collection of IFA, Stuttgart

—

Isabel Stevens works at Sight & Sound magazine. Her writing on film and photography has appeared in numerous publications, including The Guardian, Icon, Source, and World of Interiors. Follow her on Twitter @IsStevens

The post Subversive Desires appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 7, 2014

The Fine Art of Making Things

In The Photobook Review 005, Guest Editor Darius Himes and Publisher Lesley Martin spoke to a handful of people who have collectively (and many, individually) spent decades working with artists to help manifest, in physical form, the ideal book that is in their imaginations. For ease of discussion, three micro-stages have been identified: the consideration of materials, preparation of files, and what happens (or goes wrong) on press, when the images are finally made real.

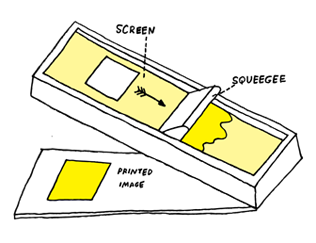

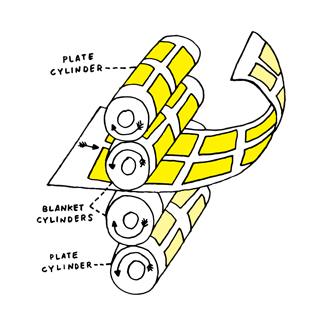

Part C: Putting Ink on Paper

The on-press experience

Do you think it is critical for someone to oversee the printing to achieve a successful photobook? Should an artist go on press?

Kimi Himeno (AKAAKA): Yes, it is definitely important. Printing is a critical component that determines how the images are presented to an audience. I work as both a publisher and a production expert; in relation to the artist, I am a kind of me- dium between them and the photobook—I try to channel their needs. In order to translate the creativity and originality of the work itself into an object (a photobook), I develop an intense dialogue with the artist. Sometimes my ideas can be more extreme than the artist’s. I think it is useful for the artist to be on press in most cases. Many Japanese artists continue to think of the photobook as the best way to show their works. From this view, having someone oversee the printing can be the key to the success of the final work.

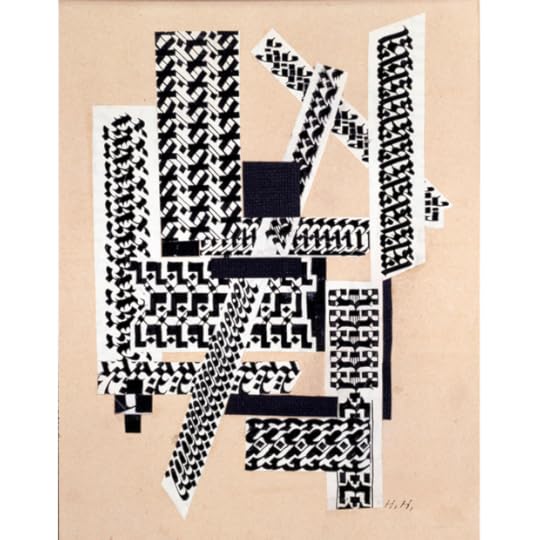

Maggie Prendergast, Production Illustrations, maggieprendergast.com

Danny Frank (Meridian Printing): Artist, production expert, curator, publisher—all of these roles contribute to the success or lack of success of any photobook. I have worked with the least “knowledgeable”—in the technical sense—clients who have contributed the most to the overall quality of the book. The professional roles people have are often less important than their particular vision. If an artist wants to be on press, then I always encourage them to come. It is always surprising to me when artists don’t want to see what happens when their work is translated into ink. My role is to understand what the artist is expecting and then to come up with the appropriate technical solutions.

David Skolkin (Skolkin + Chickey): Critical, no. Preferred, yes. Often the ability to go on press is dictated by the budget the book has. Simply stated, in my experience, I have always found that being on press produced a better book. Being there gives me the chance to fine-tune the images, troubleshoot anything that may come up, and work closely with the pressmen, which often adds that touch of magic that really allows the book to sing. It can make a good-looking book a great-looking book. I have long and good relationships with printers I like to work with, so I often feel confident that when budget or schedule doesn’t allow I will still get a good result. But, when possible, being on press is the best way to go. I really like to have the artist with me. Not only can it be tremendously helpful when a decision needs to be made instantly, but it also adds so much to the whole “texture” of the press check.

Matthew Harvey (Aperture): Printing is a constant push and pull, always taking one thing in exchange for another. For photography, printing in CMYK is like translating language. The two languages might not always share the same words, but a good translation can express the sense of the original words. The decisions that are made on press about that translation are never made by one person, but are a collective effort made with a group of (usually) incredibly skilled and perceptive pressmen. For me, having the photographer involved in that conversation makes all the difference. It is ultimately their work that is being reproduced and they have the most intimate knowledge of the images, but it’s my job to help them get to that translation.

How much control does one have over the final result at the printing stage?

Frank: Offset printing is still not “scientific.” Perhaps the question should be how little control one has at the final stage. The basic decisions have already been made. You are not going to change the design, paper (although that has happened), number of colors, or type of separations. However, final interpretation of the separations and proofs can vary greatly from one person to another. Whatever the proofing system being used, there is never an exact match to what has been approved. Looking at wet ink, in various lighting conditions, in your particular state of mind, will change the decisions you make. The same applies to the pressman, who may have no artist or production person present.

Maggie Prendergast, Production Illustrations, maggieprendergast.com

I remember working with Richard Avedon during the printing of The Sixties at Meridian. Initially the printing was being supervised by the studio manager, who didn’t have any experience with offset printing. The manager noticed an almost imperceptible tonal break in the highlights. He refused to let us continue printing because of something that you could only see with a hight-powered loop. I called Avedon and explained to him that the quality of the book was going to be compromised because all our efforts were being directed to something that wasn’t really a problem. Avedon took the train up here, looked at the sheet in question, and told the studio manager to go home so we could continue printing. He was not interested in the tiniest electronic blip. He just wanted his images to look right.

Nicole Katz (Paper Chase Press): You have very little control at the final stage. You can make slight overall shifts in color or density, but anything specific will require resubmitting files and/or creating new plates. This can very quickly eat through a project’s budget and your patience!

Your time is best spent working with your printing com- pany’s prepress department to ensure files are submitted correctly, and definitely get an accurate printed proof to make corrections from. We did a project recently with a big corporate client of ours. We’d just finished getting the press up to color to match their proof when our client arrived for his press check. Instead of approving the press sheet as we thought he would, he showed us the artwork on his cell phone and said the color didn’t match! He (mistakenly!) thought that viewing the image on his phone was more reliable than our printed proof, so he hadn’t bothered making changes to the proof when it had arrived in his office the week before. It all worked out in the end, but that’s not the ideal way to achieve the results we all wanted!

Himeno: One of our recent books, Jin Ohashi’s Surrendered Myself to the Chair of Life, is A3 size (16 1⁄2 x 11 1⁄2 in.) and four hundred pages—a monster book. We spent thirty-eight days (and nights) printing it. Actually, the printing machine broke down during the process, so, including its maintenance, the printing took about two months! I can tell you that our printer (Onoue Printing) is one of the best in Japan, but, still, it took so much time and energy (even before going on press, we had conducted tests of many different types of paper and many proofs). Even though we had at least one person on press at all times, we ended up having to reprint 20 percent of the pages. One of the issues was that printing at such a large size frequently incurs small roller marks—streaks of ink on the pages. It was a serious problem on this book. The printing house decided to change all the rollers to brand-new ones just to try to keep this from happening. I remember that a man from Heidelberg, the press manufacturer, spent nights adjusting the machine. I can’t thank everybody enough!

—

Contributors include: Xavier Barral, Publisher and designer, Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris; Alexa Becker, Acquisitions editor, Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany; Danny Frank, Project director, Meridian Printing, East Greenwich, R.I.; Tricia Gabriel, Publisher, The Ice Plant, Los Angeles; Matthew Harvey, Production manager, Aperture, New York; Kimi Himeno, Publisher, AKAAKA, Tokyo; Nicole Katz, Cofounder, Paper Chase Press, Los Angeles; Christina Labey, Cofounder, Conveyor Arts, Hoboken, N.J.; Michael Mack, Publisher, MACK Books, London; Sue Medlicott, Founder, The Production Department, Whately, Mass.; Thomas Palmer, Separator, New Haven, Conn.; Paul Schiek, Photographer and publisher, TBW Books, Oakland, Calif.; David Skolkin, Cofounder, Skolkin + Chickey Design and Radius Books, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; David Strettel, Owner and publisher, Dashwood Books, New York

The post The Fine Art of Making Things appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 5, 2014

Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media (Video)

The Spring 2014 issue of Aperture magazine, produced in collaboration with guest editor Susan Meiselas and Magnum Foundation, explores how the ground for socially engaged documentary storytelling has radically shifted over the last decade and how photographers might adapt. On February 25th, 2014, Aperture hosted Susan Meiselas in conversation with Lev Manovich and Teru Kuwayama, two practitioners who extend the language of documentary by harnessing social media in novel ways. The audience was then invited to ask questions.

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the board and members of Aperture Foundation.Moderated by Susan Meiselas, Manovich and Kuwayama discussed opportunities for rethinking contemporary documentary practice. After, the audience joined in a brief Q&A.

View “Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media” Part 1 and Part 3 on Vimeo.

Aperture 214$19.95

Aperture 214$19.95The post Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media

The Spring 2014 issue of Aperture magazine, produced in collaboration with guest editor Susan Meiselas and Magnum Foundation, explores how the ground for socially engaged documentary storytelling has radically shifted over the last decade and how photographers might adapt. On February 25th, 2014, Aperture hosted Susan Meiselas in conversation with Lev Manovich and Teru Kuwayama, two practitioners who extend the language of documentary by harnessing social media in novel ways. The audience was then invited to ask questions.

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the board and members of Aperture Foundation.Moderated by Susan Meiselas, Manovich and Kuwayama discussed opportunities for rethinking contemporary documentary practice. After, the audience joined in a brief Q&A.

View “Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media” Part 1 and Part 3 on Vimeo.

Aperture 214$19.95

Aperture 214$19.95The post Documentary Expanded: Interventions in Social Media appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Elinor Carucci: Mother (Video)

�On Wednesday, March 6 2014, Aperture Foundation in collaboration with the Department of Photography at Parsons the New School for Design presented a talk and book signing with artist Elinor Carucci. A longtime artisan of the personal documentary image, Carucci’s photographs delve into the fissures and camaraderie of family. In an early series, Comfort, Carucci turned the lens on her parents, describing the hereditary aspects of her own identity. Another series, Closer, depicts a marriage fraught with infidelity and addiction. Carucci’s recent publication Mother (2013) documents the lives of her children, in a collection of images wrought using Carucci’s characteristic tactility with delicately personal subjects. After presenting, Carucci answered questions from the audience, and was available for a book signing.

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the board and members of Aperture Foundation.

View “Elinor Carucci: Mother” Part 2 and Part 3 on Vimeo.

The post Elinor Carucci: Mother (Video) appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Elinor Carucci: Mother

�On Wednesday, March 6 2014, Aperture Foundation in collaboration with the Department of Photography at Parsons the New School for Design presented a talk and book signing with artist Elinor Carucci. A longtime artisan of the personal documentary image, Carucci’s photographs delve into the fissures and camaraderie of family. In an early series, Comfort, Carucci turned the lens on her parents, describing the hereditary aspects of her own identity. Another series, Closer, depicts a marriage fraught with infidelity and addiction. Carucci’s recent publication Mother (2013) documents the lives of her children, in a collection of images wrought using Carucci’s characteristic tactility with delicately personal subjects. After presenting, Carucci answered questions from the audience, and was available for a book signing.

This program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the board and members of Aperture Foundation.

View “Elinor Carucci: Mother” Part 2 and Part 3 on Vimeo.

The post Elinor Carucci: Mother appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 21, 2014

Basetrack: Conversation with Teru Kuwayama

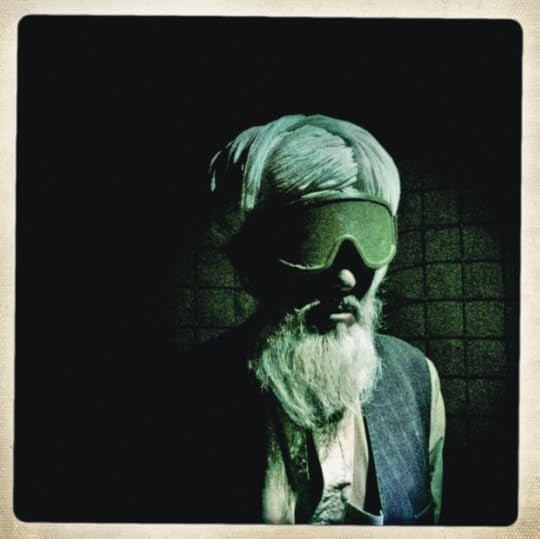

Balazs Gardi, Afghan detainee at Patrol Base Talibjan, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, November 7, 2010

In 2010, after many years of covering the war in Afghanistan, freelance photojournalist Teru Kuwayama received an invitation to embed with the First Battalion of the Eighth Marine Regiment in Helmand Province. Although it was only the start of the counterinsurgency campaign, it was the tenth year of a long and costly war that carried on at a far remove of the daily lives of Americans in the United States. Along with four other photographers, Balazs Gardi, Tivadar Domaniczky, Omar Mullick, and Rita Leistner, Kuwayama decided to approach the embed differently, and started Basetrack, a social-media reporting project conceived to connect Marines and their families and to target the social network—friends, family, and online presence—surrounding the battalion. Most of the pictures were taken with mobile phones or inexpensive consumer-grade cameras and distributed through Basetrack’s WordPress website, Flickr, and Facebook, the main Basetrack channel.

Last November, Kuwayama corresponded with Aperture about the experience of building Basetrack, the advantages of social media, and the misconceptions surrounding the early termination of their embed with the battalion.

—The Editors

Aperture: What was the nature of the partnership among contributing photographers?

Teru Kuwayama: It was a network operation. Photographers who had never worked in Afghanistan or who had never embedded with Marines were partnered up with the experienced operators. Two-person teams rotated in and out, to maintain a constant presence with the battalion.

The forward operators—the photographers on the ground—had extremely limited Internet access, so rear operators were tasked with maintaining the conversation online.

Aperture: Did you have any ideas, prior to the embed, of what you wanted to show or photograph?

TK: I avoid expectations or preconceived notions, but at the time we launched the project, counterinsurgency (or “COIN,” its military abbreviation) had been introduced as the new strategy in Afghanistan. One of the goals of Basetrack was to show the public what that counterinsurgency actually meant and looked like in practice. Ultimately it wasn’t about photography; it was about opening lines of communication. Photographs weren’t the product; they were the tactic.

Aperture: The project’s homepage featured a Google Maps interface. Why was a mapping component important?

TK: Basetrack was designed for a desktop user experience, focused on a mobile team traveling from outpost to outpost in southern Afghanistan. Map-based navigation was an intuitive approach. A core piece of the mission of the project was to tackle the abstraction of “over there” and to speak to the distance and the separation between the Marines and their families. Another piece was to provide some basic training in geography for those who might not have found Afghanistan on a map. Markers on the map were scrambled, so they reflected approximate but imprecise locations so as not to provide geolocation coordinates that could be used for targeting. The locations of the bases weren’t secret in any case.

Faces of vulnerable individuals, like Afghan interpreters working for the military, were blacked out. We did those redactions ourselves, at our own initiative, unlike a lot of major news organizations that don’t always demonstrate much concern for the fate of fixers and translators—but we also created custom software that allowed a designated military officer to black out any imagery or text that concerned them for any reason. The caveat was that the system also required them to articulate a justification for the redaction in a pop-up text window. Any redacted images or text were published, showing the blacked-out areas, making the redaction completely obvious. Unlike the hidden self-censorship typical in the mainstream media, we put the power and responsibility for withholding images or information squarely in the court of the military. Effectively, we facilitated unlimited censorship as long as it was done openly. In principle, it was very similar to the “transparent censorship” system that Twitter rolled out a year or two later.

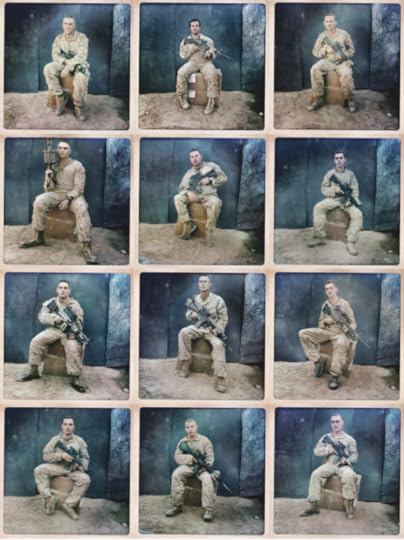

Tattooed U.S. Marines, First Battalion, Eighth Marine Regiment, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2010–11. First row: photographs by Balazs Gardi; second row: photographs by Teru Kuwayama; third row, from left to right: two photographs by Teru Kuwayama, last photograph by Monica Campbell.

Aperture: What were the images, or kinds of images, that engendered the most active conversations?

TK: Portraits of the Marines, but any kind of glimpse into the deployment triggered intense reactions. Our core audience was made up of family members who desperately wanted a glimpse of their Marines—any evidence that they were alive and well, any insight into the world they were living in.

Aperture: Was there any content that was controversial or produced a reaction that was unexpected?

TK: What was interesting was the banality of the controversies. For civilians, it can be hard to fathom that in some quarters of the military there’s a remarkable level of fastidiousness about seemingly trivial rules and regulations, down to the “authorized color” of socks or the length of sideburns or mustaches. The greatest scorn is reserved for “uniform Nazis,” referring to the kind of cultural bureaucracy where troops are punished for infractions such as not shaving properly, rolling their sleeves up, or not “blousing” their trousers according to regulation.

One Marine told me about being punished because a superior officer had found a photograph, posted on Facebook by his sister, where he appeared with minor infractions of the uniform standards. We found ourselves in a curious position when we sometimes had to withhold photographs that had no real “operational security” issues, effectively to protect Marines from their own officers. We approached this with the same transparency as we did with image and text redaction.

When families asked for photographs of their Marines and learned that some were being withheld for such seemingly absurd reasons, it generated a lot of debate on our Facebook page, and on some level, probably undermined the faith that family members might have had in the judgment of “command,” and along with it, the underlying logic of the “operational security” mantra that they were so familiar with.

First row, from left to right: 1st Lt. Robert Rain, age 26, from Dallas, Texas; LCpl. Richard Giligen, age 19, from Bellefonte, Pennsylvania; Sgt. Derek Charles Schwartz, age 28, from Tyler, Texas. Second row: LCpl. Sam Coley, age 21, from Campobello, South Carolina; Sgt. Justin M. Schuh, age 29, from Milford, Ohio; LCpl. Christopher Crowley, age 19, from Henderson, Kentucky. Third row: LCpl. Justin Syvinski, age 19, from Middleton, Connecticut; Cpl. Tristan Rorie, age 28, from Charlotte, North Carolina; LCpl. Chad Hughes, age 19, from West Virginia. Fourth row: Corpsman Zack Penner, age 19, from Sacramento, California; LCpl. Joe Titus, age unknown, from East Windsor, Connecticut; Cpl. Jonathan D. Sappington, age 23, from Blue Mountain, Mississippi. All photographs by Balazs Gardi, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, October 30, 2010.

Balazs Gardi, Cpl. Gretchn, IED detector dog with First Battalion, Eighth Marine Regiment Bravo Company, First Platoon, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, October 30, 2010

Aperture: Why was the website shut down?

TK: It wasn’t shut down. The project was funded [by the Knight Foundation] to chronicle a seven-month deployment, and we kept the website running for more than two years. Like any complex website, it was built on the shifting ground of hosting platforms that are constantly being updated. We didn’t have experienced developers or the resources to maintain the patchwork of code indefinitely, so the site would periodically crash, and eventually we rebuilt it.

At one point, six months into the deployment, I received an email from U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) public affairs noting claims that the Google Maps interface posed an “operational security” risk to the battalion. There was never a request to shut down the website, though, or alter the maps in any way. When I suggested working together to mitigate security issues, there was no response. In face-to-face discussions with Marine officers, it became clear that the Basetrack.org website and Google Maps weren’t the real concern. It was the Basetrack Facebook page—and the unfiltered conversations between family members—that were rattling some nerves. I was given an ultimatum to shut down the Facebook page or have the plug pulled on the embed—but no one was willing or able to articulate a rationale for doing so. The page stayed live, and the last team of embeds had their travel orders canceled. As I predicted to the battalion commanders, turning off the embeds didn’t turn off the community or the conversation. It had quite the opposite effect. There was an explosion of debate within the military community about the ejection of the embeds and a huge spike in media attention to the project.

Aperture: Was the platform used in the way you had originally intended? If not, how did Marines and family members use the site differently than you expected?

TK: The project dovetailed with a stated change in the U.S. Marine Corps that allowed deployed Marines to use social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, but as it turned out, the Marines had very limited Internet access and weren’t encouraged to express themselves online by their commanding officers. The conversation wasn’t driven by twenty-year-old Marines in Afghanistan; it was driven by their wives and mothers in the United States.

Aperture: If you were to do it over, what would you do differently?

TK: To [paraphrase] Donald Rumsfeld: “You go to war with the Army you have. They’re not the Army you might want or wish to have at a later time.” It would have been nice to have more funding, more time, and more experienced coders, but as the Marines say, “Improvise, adapt, overcome.” We maneuvered pretty well out there.

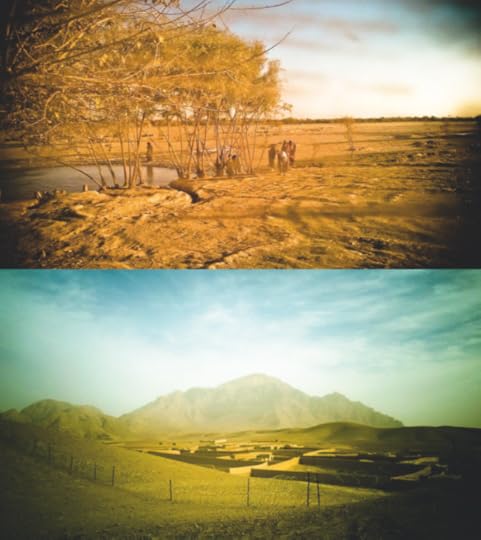

Tivadar Domaniczky, Musa Qala, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2010

Tivadar Domaniczky, Musa Qala, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2010

Balazs Gardi, Afghan National Army soldier shelters his face with a plastic bag against a dust storm at Combat Outpost 7171, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, October 28, 2010

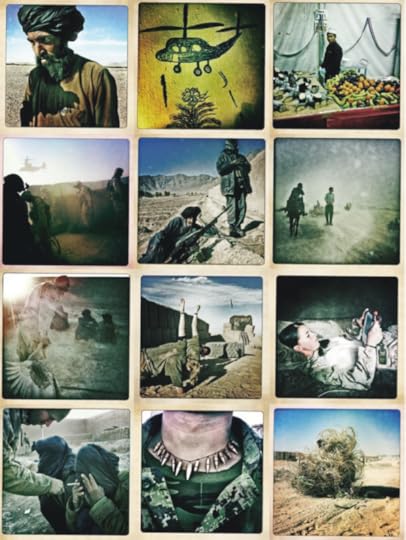

All photographs of U.S. Marine First Battalion, Eighth Marine Regiment, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2010–11. Photographers, from left to right, first row: Balazs Gardi, Teru Kuwayama, Teru Kuwayama; second row: Teru Kuwayama, Teru Kuwayama, Omar Mullick; third row: Teru Kuwayama, Rita Leistner, Rita Leistner; fourth row: Teru Kuwayama, Balazs Gardi, Monica Campbell. All photographs © and courtesy the photographers.

The post Basetrack: Conversation with Teru Kuwayama appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Matthew Pillsbury: City Stages

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

Photographer Matthew Pillsbury and guest, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

Photographer Richard Renaldi and Aperture Foundation Executive Director Chris Boot, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

Tom Atwood and Larry Siegal, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

Andrea Fernandez and Martin Adolffson, Image © Katie Booth

Michael Foley of Michael Foley Gallery, Daniel Cooney of Daniel Cooney Fine Art, and Patrick Keefe, Image © Katie Booth

City Stages by Matthew Pillsbury opening reception at Aperture Gallery, February 19, 2014, Image © Katie Booth

Photographer Richard Renaldi and guests, Image © Katie Booth

Aperture Editor Denise Wolff and guest, Image © Katie Booth

On Wednesday, February 19, Aperture Members and friends were the first to view photographer Matthew Pillsbury’s exhibition City Stages at Aperture Gallery. Pillsbury and Aperture books publisher Lesley A. Martin gave Members an exclusive tour. In introducing his work, Pillsbury noted:

What I love most about photography is its ability to show us our world. We know it has a connection to the real, but it is capable of transforming and revealing something surprising to us. For instance, it’s astonishing what has happened in the last decade since I started taking these pictures of screens. It’s no longer just about looking at televisions and computers, which were the dominant objects at the time these photographs were made. Now, the minute we have a few spare moments we pull out our phones and engage with others through e-mail, apps, and social media. Art offers us the means to process the changes that are going on in our lives and to take measure of those changes while they are happening.

View the exhibition through March 27, 2014, presented in collaboration with Bonni Benrubi Gallery. The accompanying publication, City Stages, was published by Aperture in 2013.

Membership at Aperture is about seeing it first. Engage with our talented photographers and publishers at a variety of events like these by becoming an Aperture Member today! For more information, e-mail membership@aperture.org.

— City StagesMatthew Pillsbury’s first monograph City Stages captures the vibrancy of urban landscapes in large-format, black-and-white photographs.

City StagesMatthew Pillsbury’s first monograph City Stages captures the vibrancy of urban landscapes in large-format, black-and-white photographs.

$65.00

Matthew Pillsbury City Stages Portfolio

Matthew Pillsbury City Stages Portfolio

$8,000.00

The post Matthew Pillsbury: City Stages appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers