Aperture's Blog, page 161

April 27, 2015

Doug DuBois: The Intimate Photograph

Doug DuBois, Lise and Spencer, Ithaca, NY, 2004

“In the end, we may come to the conclusion that intimacy cannot be photographed directly (as we experience it) because, quite simply, the camera is always in the way. The trick, perhaps, is to understand intimacy as an imaginary space—an illusion that exploits our very real longing for a profound and authentic encounter with another.”

—Doug DuBois

Join photographer Doug DuBois for a two-part workshop through which students will gain a better understanding of how to articulate intimacy and explore ways of creating photographs that demonstrate a certain closeness between photographer, subject, and viewer. Students will work with DuBois to assemble a rhetorical rather than purely emotional guide to photography’s intimate claims.

The first day will consist of both group and individual critiques of each other’s photographs, as well as a discussion of specific photographers and images which offer insight into the challenges, tropes, and problems of making intimate photographs. Some discussion topics and photographers include: “The Bad and the Beautiful” (Hiromix, Corinne Day, Lise Sarfati, and Juergen Teller); “Dirty Old Men” (Larry Clark and Nobuyoshi Araki); “Family Business” (Larry Sultan, Elinor Carucci, Mitch Epstein and Leigh Ledare); and “Intimate Pairs” (Alessandra Sanguinetti, Kelli Connell, and Laura Letinsky).

At the end of the first day, DuBois will offer students a selection of specifically designed assignments to test theories of intimacy as discussed. On the second meeting, three weeks later, students will present their work created from the assignments given during the first session, and discuss their experiences of responding to the assignment and creating new work.

Doug DuBois (born in Dearborn, Michigan, 1960) has photographs in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He has received fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and National Endowment for the Arts. DuBois has exhibited at the J. Paul Getty Museum and MoMA, The Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin and the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma in Italy. He has photographed for magazines, including the New York Times Magazine, Time, Details, and GQ. He has published two books with Aperture: All the Days and Nights in 2009 and My Last Day at Seventeen, which will be available in the fall of 2015. DuBois teaches in the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University and in the Limited Residency MFA program at Hartford Art School.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Register here

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Doug DuBois: The Intimate Photograph appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 24, 2015

Late April Readings on Photography

Penelope Umbrico’s photographs installed at Aperture’s Spring Party on April 17. Photograph by Max Mikulecky

Editors and staff at Aperture Foundation share what we’ve been reading recently.

“The April issue of Frieze has two compelling articles on contemporary photography by two Aperture magazine regulars: curator Brian Sholis unpacks Lucas Blalock’s beguiling still lifes, and writer Aaron Schuman looks at a cohort of photographers, who, like Blalock, playfully experiment with picture making. Yes, yes, we may be close to reaching a saturation point on the recent discourse about process-based photographs and pictures about pictures, but Sholis and Schuman, both insightful writers eager to engage a broad spectrum of photography, offer unique insights. The issue’s cover, featuring a neat stack of glinting red hot dogs—an image by Blalock—will make readers hungry for the conversation, or send them searching for a different meal.”

–Michael Famighetti, editor of Aperture magazine

“I’m currently reading ‘In the Holocene,’ the catalog released on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name held at MIT List Arts Center from October 19, 2012, to January 6, 2013. The catalog features essays from an intergenerational groups of artists, exploring art as an ‘investigative and experimental form inquiry, addressing or amending what is explained through traditional scientific or mathematical means: entropy, matter, time (cosmic, geological), energy, topology, mimicry, perception, consciousness, etc.’ The reference to ‘Man in the Holocene,’ drew me in first, it refers to the novella written by Max Frisch, which traces the trials of a man prone to categorize thunder types into a taxonomy out of boredom.”

–Sarah Dansberger, assistant archivist

“I read Teju Cole’s New York Times Magazine article ‘A Visual Remix’ — it’s an interesting discussion of our culture’s surplus of digital imagery and the increasingly common artistic practice of collecting, cataloging, and arranging these images. As our processes of creating and viewing photographs change, so does the idea of reappropriation. He also discusses Penelope Umbrico, who headlined last week’s Spring Party, as well as my new favorite Instagram project, ‘Craigslist mirrors.'”

–Taia Kwinter, Aperture magazine Work Scholar

The post Late April Readings on Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Announcing the New Issue of The PhotoBook Review

The latest issue of The PhotoBook Review, Aperture’s biannual journal dedicated to the consideration of the photobook, is out now. PBR 008 launches this coming week on both coasts: in New York at Shashin, the festival of photography from Japan, and at Paris Photo Los Angeles. Subscribers to Aperture magazine will receive it with the Summer issue, “Tokyo,” or you can pick it up for free in New York at the Aperture Gallery and Bookstore.

PBR 008 was guest edited by Ivan Vartanian, a Tokyo-based independent curator and author, as well as the founder of the imprint Goliga. In concert with Aperture magazine’s “Tokyo” issue, this issue of PBR focuses on both the young and established photographers making books in Japan today. It also shines a light on the connections between two seemingly independent areas of art production: photobook-making and performance. As Vartanian writes in his Editor’s Note, “I am driven by the questions of what defines a photobook and how those parameters can be stretched to the point that ‘book’ may no longer be an appropriate appellation for thing in question.”

Inside this issue:

Photobook as Performance as Photobook: Artists, curators, and publishers Bruno Ceschel, Sebastian Hau, Melinda Gison, Aron Mörel, Katja Stuke, and Anouk Kruithof on the relationship between photobooks and performance—whether they’re making a book or expanding upon one

If You Came Here to Have Fun, You Will: Denise Wolff interviews Jason Fulford—artist, publisher, and master of the experimental book launch—about “the parallel lives of a book through its events,” and more

Collecting the Japanese Photobook: Conversations with curators and photobook collectors Ryuichi Kaneko and Manfred Heiting, on the evolution of both the Japanese photobook and the photobook market

A centerfold by Anouk Kruithof, in collaboration with Lieko Shiga

Photobooks After 3/11: The 2011 tsunami, its aftermath, and how Japanese photographers—and those from the West—responded to the disaster via the photobook

Profiles of designer Yoshihisa Tanaka and Tokyo-based publisher Sokyusha

How to Move a Book: Publishers and distributors Tricia Gabriel and Mike Slack of The Ice Plant get real about what it takes to get a photobook out of the warehouse—or your garage—and into the hands of the people you want to see it

Plus reviews of books by Nobuyoshi Araki, William Klein, Ryuichi Ishikawa, Bohnchang Koo, Takashi Homma, Philip Gefter, and Max Pinckers

Read the Publisher’s Note from Lesley A. Martin and the Editor’s Note from Ivan Vartanian.

Double your fun: The PhotoBook Review is free with every Summer and Winter issue of Aperture magazine—but only if you subscribe. Click here to subscribe now.

The post Announcing the New Issue of The PhotoBook Review appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 22, 2015

Editor’s Note: Ivan Vartanian

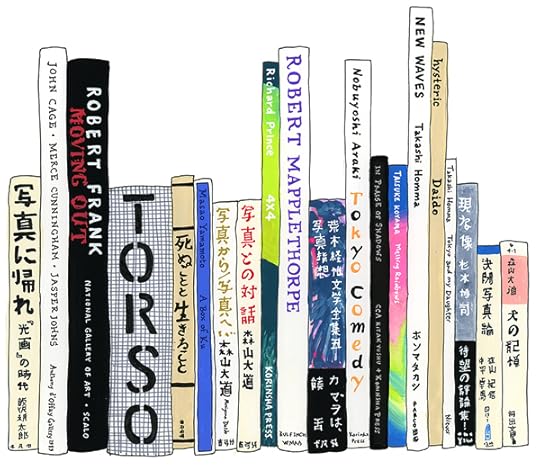

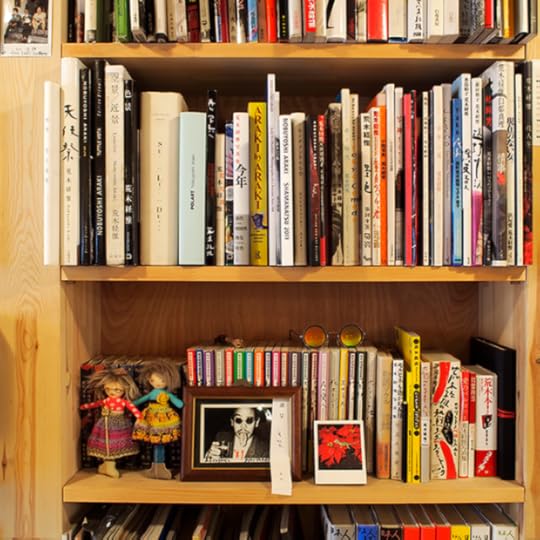

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #845: Ivan Vartanian, 2015

In 1995, I began an editorial internship at Aperture. (Just one week before, Lesley Martin had started one, too). While I was there, Daido Moriyama sent in a copy of his publication Hysteric Daido. It was the most bizarre specimen of a photobook I had ever seen: large and softcover, with magazine-like paper, black ink everywhere, and a putrid purple bar on the cover. The images were presented in a scattershot fashion, running into the gutter carelessly without white margins, captions, or any other type of structure. It did not in any way, shape, or form resemble the organized bookmaking style I had been exposed to until then. I had no clue what I was looking at. And I was hooked! That wibbly-wobbly book seemed so alive to me, and completely beguiling.

Seeing that book that day eventually led me to look at more photobooks from Japan, like those of Nobuyoshi Araki, Eikoh Hosoe (including the 1985 Aperture edition of Barakei, originally published in 1963), and Shomei Tomatsu. To my good fortune, about a year later I was given an opportunity to work in Tokyo. What was supposed to be a one-year sojourn working for a Japanese publisher, Korinsha, turned into a permanent move.

The components of this issue of The PhotoBook Review reflect the last eighteen or so years of my time in Japan. The books appearing in my Ideal Bookshelf, for example, are a partial representation of my work anthologizing and translating writing by Japanese photographers, which evolved into Setting Sun: Writings by Japanese Photographers (2006). Immediately after that book was completed, I turned my attention to the photobooks I had scoured to find those texts, which led me to meet and work with Ryuichi Kaneko. I am deeply indebted to him, my guide to Japanese photo history and the books that tell its story. To honor that massive influence and represent the heart that goes into serious scholarship, an interview about his collection was essential for this issue. Sitting with him once again in his warehouse, surrounded by his collection, rain pouring down outside, I felt transported again to that time when I first encountered photobooks from Japan and was gobsmacked by the sheer intensity and alienness of the images, and by their accompanying texts.

I am driven by the questions of what defines a photobook and how those parameters can be stretched to such a point that “book” may no longer be an appropriate appellation for the thing in question—which we consider in a section on the relationship between photobooks and performance. Many of the ideas that I am dealing with now germinated in the research I did for Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s (2009). It taught me this: research leads to experimentation; looking back leads to making something new. Much of that material was more contemporary and synchronous with my everyday life than many of the photobooks I was looking at in the early 2000s.

As Lesley mentions in her Publisher’s Note[link to pub note], this publication is a companion to both the “Tokyo” issue of Aperture magazine and the Shashin Festival, held in New York this April. My goal and involvement in each of these activities is to present photography from Japan to the widest possible audience. It is my hope that this assemblage of activity will serve as an entry point for many more to enjoy the wide spectrum of the exciting photography, writings, and design that I have been fortunate enough to savor all these years.

Ivan Vartanian is a writer, curator, and publisher based in Tokyo. Under the imprint Goliga, he has collaborated on and produced many projects—books, exhibitions, installations, performances, events, and limited editions—with Japanese photographers. Vartanian is the coauthor of Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s (Aperture, 2009) and Setting Sun: Writings by Japanese Photographers (Aperture, 2006). He is the founder and program director of the Shashin Festival: Photography from Japan. Vartanian is also the director of the Amana Collection. goliga.com

Jane Mount (illustration) published My Ideal Bookshelf, a collection of the favorite books of one hundred creative thinkers, with Little, Brown in 2012. idealbookshelf.com

The post Editor’s Note: Ivan Vartanian appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin

The PhotoBook Review 008 coincides with the Summer 2015 issue of Aperture magazine, “Tokyo” (#219), as well as with Shashin, a symposium and festival for Japanese photography that takes place on April 24 and 25 at the New York Public Library. All three have been shaped, in part, through consultation with Our Man in Tokyo and this issue’s guest editor, Ivan Vartanian of Goliga.

Several threads in these pages wend their way back to an event that took place at Aperture Gallery in November 2011, Printing Show—TKY, by the Japanese master bookmaker and photographer Daido Moriyama. This event, organized by Goliga, invited participants to create their own edit from a selection of fifty double-sided, gatefold spreads, and has now been restaged around the world. It was challenging to pull off. We had no idea what to expect. But once the doors opened, with Mr. Moriyama in place at the center of the gallery, surrounded by silk-screening equipment, photocopiers, and a stalwart crew of staplers, paper-runners, and other assistants, the energy was palpable. Four years later, it still resonates with me as a rare and magical occasion during which the usually insular act of bookmaking became a communal, externalized celebration. I’d never seen visitors in the gallery as engaged with the idea of editing a set of pictures, or of selecting, sequencing, and bringing together a collection of printed (in this case, photocopied) pages.

That essential idea—of redrawing the boundaries of the photobook via events and performances, in order to engage audiences at earlier stages of a book’s creation or more inclusively at the time of its launch—has its own history. But it has also become an important part of our present. This issue includes commentary from contemporary artists such as Melinda Gibson, Katja Stuke of BöhmKobayashi, and Jason Fulford, as well as curators and publishers such as Bruno Ceschel and Aron Mörel, on the intersection of performance, bookmaking, and audience engagement. Later in the issue, the critical (and rarely discussed) final component of publishing, which is getting finished books into readers’ hands and homes, is addressed by Mike Slack and Tricia Gabriel, who are both bookmakers and booksellers under the imprint The Ice Plant.

One important targeted audience in the ecosystem of the photobook is the collector. The current state of connoisseurship and the knowledge base regarding in-depth photobook history would not exist without their commitment and obsessions. It is a treat to have the commentary of two veteran collectors in this issue, Ryuichi Kaneko and Manfred Heiting, focusing specifically on their interest in the Japanese photobook. And finally, we are delighted to have a centerfold by the ever-performative Anouk Kruithof, who brings us a long-distance, collaborative reading of Lieko Shiga’s photobooks, in dialogue with that artist.

All of this has come together, as always, with the generous input of time and brain power from our guest editor and many contributors, who we thank for being part of the ongoing experiment that is The PhotoBook Review. Last, but never least, this effort to publish is not yet complete until it is open and in your hands, the PhotoBook Reader. Thank you, as always, for your interest and support.

—Lesley A. Martin

Publisher, The PhotoBook Review, and Director of Special Projects, Aperture Foundation

The post Publisher’s Note: Lesley A. Martin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 21, 2015

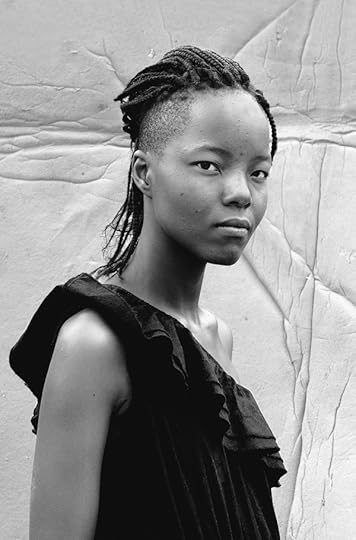

Zanele Muholi’s Faces & Phases

Eva Mofokeng, Somizy Sincwala, and Katiso Kgope, Parktown, 2014

For more than a decade, South African photographer Zanele Muholi created a visual record of black lesbians in her home country. Although South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006, discrimination and violence against queer women remain widespread. In 2006, Muholi began her Faces and Phases project, an ambitious series of bold, undeniably powerful portraits of lesbians made against plain or patterned backgrounds—now numbering around three hundred—and often exhibited in tightly arranged grids. Faces and Phases is the subject of an extensive book, published by Steidl last fall, that forms a monumental chapter in Muholi’s mission to remedy black queer invisibility. Muholi’s work has been exhibited globally and she will have her first large-scale museum exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence, on May 1. Last November, Deborah Willis—author, curator, and prominent historian of photography—spoke via Skype with Muholi, who is based in Johannesburg, about photography and activism, her latest series Black Beauties, and her influences. This interview appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App:click here to read more and download the app.

Deborah Willis: Let’s begin with Faces and Phases. When and where did this project begin?

Zanele Muholi: It started in 2006 and I dedicated it to a good friend of mine who died from HIV complications in 2007, at the age of twenty-five. I just realized that as black South Africans, especially lesbians, we don’t have much visual history that speaks to pressing issues, both current and also in the past. South Africa has the best constitution on the African continent and, dare I say, world—when it comes to recognizing LGBTI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex) persons and other sexual minorities. It is the only country on the continent that legalized same-sex marriage in 2006. I thought to myself that if you have remarkable women in America and around the globe, you equally have remarkable lesbian women in South Africa.

We should be counted and certainly counted on to write our own history and validate our existence. We should not feel that somebody owes us these liberties. So, it’s another way in which I personally claim my full citizenship as a South African photographer, as a South African female in this space, as a South African who identifies as black, and also as a lesbian. I’m basically saying we deserve recognition, respect, validation, and to have publications that mark and trace our existence.

Lesedi Modise, Mafikeng, North West, 2010

DW: That’s a beautiful introduction to the project, which offers a wonderful way of reading bodies and faces and new identities. When’s the first time you remember seeing a photograph, or knowing a photograph, of a black lesbian in South Africa?

ZM: The early images I remember are black-and-white images of apartheid-era South Africa. Most were captured by male photographers like Ernest Cole or Alf Kumalo. Early images I saw depicted black women crying, images of pain, of struggle. Before black lesbian imagery clouded my mind, the first images I remember are of domestic workers, which were captured mainly by men. I looked at the work of David Goldblatt, who I regard as one of the forefathers of photography in South Africa, and the work of Jürgen Schadeberg. Those are some of the male photographers who captured apartheid South Africa.

I was born at the height of apartheid. I learned about South African women photographers very, very late. A friend gave me a book called Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (1993), which was produced in America. I liked that book very much.

Tumi Nkopane, KwaThema, Springs, Johannesburg, 2010

DW: Viewfinders was written by the photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

ZM: Yes, her book changed my life in so many ways. I just thought to myself that photography has to become a lifetime thing in which I deal with my own issues, my own personal issues. I quoted Joan E. Biren (JEB), an American photographer, in my thesis. Her work related to what I wanted to achieve, and it still means so much to me in ways that you won’t believe. You look at Biren’s images and you think that someone has done what I’m trying to capture now, except I’m doing it from a South African point of view.

I understood the South African struggle of being forcefully removed from your own space, a space you thought belonged to you, where women were regarded as working machines. My mom was a domestic worker and the images of domestic workers, and the images of women crying, struggling, with children on their backs, those became my daily consumption.

Teekay Khumalo, BB Section, Umlazi, Durban, 2012

DW: Did you start off by photographing your mother, early on?

ZM: I photographed my mom very, very late, around the time she started getting ill. It’s often very difficult for us to confront our own issues. I mention in my film Difficult Love (2010) that it’s a pity we don’t tend to look at ourselves and our immediate spaces and how the outside world becomes familiar and easier for us to deal with than our own personal issues. She had cancer of the liver, and she passed on in 2009. But I do have images that I took of her.

Yonela Nyumbeka, Makhaza, Khayelitsha, Cape Town, 2011

DW: How did she feel about the photographs?

ZM: She was always quite supportive of what I was trying to achieve, and I was out to my mom. I delayed the whole process of photographing her and missed her as a beautiful young woman. Looking at our family album, of images that were either dated, without the photographer’s name, or that had some strange names at the back, you think, Who has taken those images? What was their intention? Why are they not captured in this and that way?

The photograph that I eventually took later was of her wearing a church uniform. She was sick but allowed me to take that particular photograph. But I regret very much not having photographed her in her coffin. She looked so beautiful. But that meant negotiating with my family members, who didn’t understand the importance of documentation, so I let go of that photograph. In my imagination, I have this beautiful woman who did not look sick in her coffin.

Zukiswa Gaca, Grand Parade, Cape Town, 2011, Courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

DW: Your photography has been described as work that “mourns and celebrates.” What do you think about such labeling?

ZM: It depends on the context. I’m reclaiming photography as a black female being. I’m calling myself a visual activist, whether I am included in a show or not, whether I am published or not. That’s my stance as a person, before anything else, before my sexuality and gender, because photography doesn’t have a gender.

Ernest Cole, for instance, captured the men in the mines. The mineworkers were humiliated to nothing, captured naked, discounted to nothing, nameless. He showed an unjust system that dehumanized workers. All we see, all we remember, are those black men and their bodies facing the wall. That was visual activism, but at that time people did not regard it as anything of that sort, even if people at that time were killed and forcibly removed. Today, lesbians in South Africa are brutally murdered. “Curative rape” is used on us. That forces me to redefine what visual activism is. If I were to reduce myself to the label “visual artist,” it would mean that what I’m doing is just for play, that our identities, as black female beings who are queer or are lesbian, is just art. Art needs to be political—or let me say that my art is political. It’s not for show. It’s not for play.

Click here to subscribe to Aperture magazine and read more of Issue #218, Spring 2015, “Queer.”

The post Zanele Muholi’s Faces & Phases appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Lucas Foglia on “Human-Altered Landscapes”

George Chasing Wildfires, Eureka, Nevada, 2012

Last year, photographer Lucas Foglia published Frontcountry, his second book with Nazraeli Press. Like its predecessor, A Natural Order (2012), Frontcountry chronicles an American community with unusual depth and feeling. Blending portraits, landscapes, and interior scenes, Foglia offers “a photographic account of people living in the midst of a boom in mining and energy development that is transforming the contemporary American West.” Foglia’s work is included in “Human-Altered Landscapes,” a display of landscape pictures made during the past forty years that is drawn from the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection. The display remains on view in Cincinnati until July 19. –Brian Sholis

This interivew first appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Brian Sholis: You’ve completed two long-term projects documenting specific American communities. The first, A Natural Order, features photographs of people in the American Southeast who have chosen to live off the grid. The latest, Frontcountry, chronicles people living in the midst of a mining and energy boom in the American West. How did you decide to photograph these people and places, and how did you make initial inroads into these communities?

Lucas Foglia: Both projects started from a friend. In 2006, I visited Doug Elliott and his family in rural North Carolina. They live in a house built into a hillside, grow most of their food, and get their water from a nearby spring. I asked Doug if he knew other families who had left cities or suburbs to live like him, and he drew me a map.

In 2009, I visited Addie Goss, who worked for Wyoming Public Radio. She introduced me to people living in small communities next to the biggest tracts of open land that I had ever seen. I went to the rural American West expecting to meet cowboys. I did meet cowboys, but everyone was talking about jobs in the natural gas fields, or in the gold mines. I went back to visit those areas again and again because I wanted to learn more about the place, and the people I met there. Because I was introduced to the people I photographed by their friends, they trusted me and guided me.

Moving Cattle to Spring Pasture, Boulder, Wyoming, 2011

BS: This daisy-chain progression differs from how we think of photographers on their quintessential American road trips. You’re meeting people and getting to know them, sometimes closely, rather than rolling into town, snapping away, and continuing down the highway. Can you explain how this familiarity shapes the portraits you take? And how does your subjects’ local knowledge affect your choice of locations for your landscape pictures?

LF: I do use roads to get places, but I don’t think of myself as a quintessential road-trip photographer. People I meet tend to know more about their home and community than I do, and so I stay and listen, and look for scenes in everyday life that seem extraordinary.

For instance, a friend of a friend, named Richard, worked as a safety inspector in the natural gas fields in Wyoming. He gave me a red Halliburton helmet and took me out to the drilling rigs on the Pinedale Anticline, where I met Roger. Roger worked as a welder, one of the most dangerous jobs in the country because of the sparks his tools gave off in areas filled with flammable gas. Roger is also a former bodybuilder and United States Army Special Forces soldier. He and the other welders lifted weights in the welding shop tool shed.

Mia and Burgundy, Cokeville, Wyoming, 2010

Or, for instance, I was introduced to an activist named Deb, who drove with me to Thermopolis, Wyoming. Thermopolis is locally famous for its hot springs. Just outside of town we visited a ranch and watched cows drink from a creek. Then we followed the creek up into the Hamilton Dome Oil Field. In an oil field, a good amount of water is pumped out of the ground along with the oil. The water contains salts, oil droplets, chemicals, gases, and bacteria. At Hamilton Dome Oil Field the produced water is discharged, steaming, into the local river system. The pipes and the flood of water from deep underground looked surprisingly beautiful.

Produced Water, Hamilton Dome Oil Field, Owl Creek, Wyoming, 2013

BS: If the affinity you feel isn’t necessarily with road-trip photographers, what do you make of the legacy of the “New Topographics” exhibition featuring Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel, Jr.? These artists, beginning in the early 1970s, ushered in a new view of the American landscape. Their attention to the ways in which humans used the land, and how a society can be understood from pictures of places, seems congruent with your own careful attention to present-day land use.

LF: Most of the people in the places I photograph know who Ansel Adams is. He had a moral mission to inspire conservation by photographing nature in a pristine form. The photographers in “New Topographics,” on the other hand, were more objective. Their photographs said, “Here is what people are doing; make what you will of it.”

Coal Storage, TS Power Plant, Newmont Mining Corporation, Dunphy, Nevada, 2012

I have a moral mission. I want my photographs to bring attention to people and places that, in my opinion, deserve attention. A wild West is part of our American story, and I think it’s important to conserve the open land we have left. In small towns, agriculture can be sustainable, while mining is boom-to-bust.

I also want my photographs to be complex. I want to compel viewers to think and feel without telling them what to think or feel. I hope Frontcountry is a portrait, not an indictment, of the contemporary, rural American West, because everyone I photographed talked about caring about the landscape they live in.

Surface Mining, Newmont Mining Corporation, Carlin, Nevada , 2012

BS: Your photographs are not only exhibited in galleries and museums, but also often reproduced in newspapers and periodicals. Do you believe these expanded audiences amplify or broaden your “moral mission”? How do such opportunities to present your work in print, as well as online, affect your thinking about what you do?

LF: I love the fact that a photograph can be used in so many different ways. A book, to me, is the sum and the completion of a project. I exhibit editioned prints of my photographs in galleries and museums, and publish the images in newspapers and magazines. I also post the images online, give copies back to the people I photograph, and give copies to local and national organizations to use for advocacy. All are different methods of storytelling. I’m grateful for them, and I think there is art in each of them.

Lucas Foglia, Roger Weightlifting, Jonah Natural Gas Field, Boulder, Wyoming, 2010. Courtesy the artist and Fredericks & Freiser, New York.

“Human-Altered Landscapes” is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum through July 19.

The post Lucas Foglia on “Human-Altered Landscapes” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 17, 2015

Five Photography Exhibitions to See in New York this April

William Klein, West Indian Street Parade, Brooklyn, 2013. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

William Klein + Brooklyn at Howard Greenberg Gallery (through May 2): Simply titled William Klein + Brooklyn, the iconic photographer and filmmaker’s new show at Howard Greenberg Gallery collects nearly 50 photographs taken in the summer of 2013. Commissioned by Sony as part of the corporation’s Global Imaging Ambassadors program—an initiative that unites image-makers around the globe with the aim of storytelling—Klein was asked to explore Brooklyn using a digital camera provided by Sony, a surprising first for the artist, who has preferred film and a wide-angle lens throughout his career. In Klein’s visual interpretation of Brooklyn, the atmosphere is frenzied and confrontational. Presented large scale and unframed, the photographs are mostly displayed in grids, pressed against each other to create one object containing a variety of moments. A quiet shot of the Brooklyn Bridge is sandwiched between a dance performance by children and a street scene of Hasidic men gesturing emphatically to each other in evening light. An extreme close-up of two sunbathers reveals a bright floral swimsuit and a Kate Spade beach bag; right next to it is a photograph of the dilapidated yet still vibrant and bold Coney Island storefronts. Except for some discernible sights, the distinctions between neighborhood and place become secondary; looking at the closely organized grids, the viewer feels all sights and sounds at once, an effect that echoes Klein’s reflections in the accompanying publication by Contrasto: “Brooklyn for me, a Manhattanite, has always been a mystery. This year, it became a photographic discovery.” — Taia Kwinter

Pavel Acosta, Poker Face, from the series Stolen Talent, 2009-10. Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

The Light in Cuban Eyes at Robert Mann Gallery (through May 23): As the U.S. opens up relations with Cuba, the gallery presents an exhibition devoted to photographs made before and after the country’s “Special Period,” which followed the Soviet Union pullout in the early 1990s. Stark black-and-white documentary photography is complemented by images of untouched landscapes, as in Lissette Solórzano’s epic shots. And there’s ample humor, too, in the posed portraits of Adrián Fernández and René Peña.

Installation view of Alison Rossiter’s Paper Wait, Yossi Milo Gallery.

© Thomas Seely and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Alison Rossiter: Paper Wait at Yossi Milo Gallery (through May 2): In these camera-less photographs, Rossiter uses expired photographic paper that she then augments with liquid developer– but what develops on the film is in fact a visual record of the life of the papers themselves, which date from the 1890s to the 1960s.

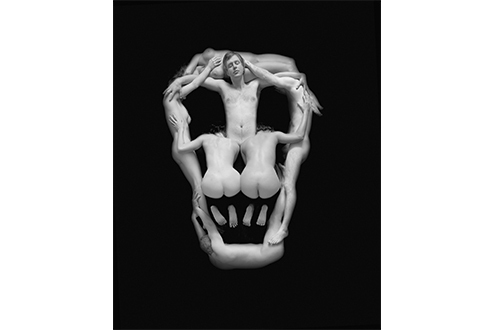

Piotr Uklanski, Untitled (Skull), 2000. Courtesy the artist

Fatal Attraction: Piotr Uklanski Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (through August 16): Polish artist Piotr Uklanski was given free rein among the Met’s archives as well in its grandiose entry, and true to form he brings a sense of provocation to the staid institution. For the “Selects” portion of the exhibition, he chose a compendium of objects from the museum’s vast holdings that illuminate his own practice, from Henri Cartier-Bresson to Laurie Simmons to ancient Egyptian relics. His selections complement his own solo show of photographs, bright and glossy imitations of Kodak’s Joy of Photography as well as an excerpt from his infamous series The Nazis (1998), a grid surveying Nazi pop culture. In the main entry to the museum, a diptych of two large-scale banners hang from the ceiling. In the second one, a mass of 3,000 soldiers cloaked in red coalesce to form the word “solidarity” in Polish, calling on the name of the first trade union in a Warsaw Pact country that escaped Communist Party control. Uklanski brings the personal as well as the political into inspiring play.

Barbara Kasten, Transposition 3, 2014. Courtesy Bortolami Gallery, New York

Barbara Kasten: Set Motion at Bortolami Gallery (through May 30): Kasten’s first solo show with the gallery coincides with the artist’s survey exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art, Philadelphia. The exhibition centers on two series of photo-based work: Kasten’s Amalgams–gelatin-silver prints created without a camera where the artist placed objects on photographic paper, then magnified the results–were made in the 1970s. Her new series, Transpositions, presents photographs made with colored sheets of Plexiglas to create sculptural, geometric shapes, inspired by Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France.

The post Five Photography Exhibitions to See in New York this April appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

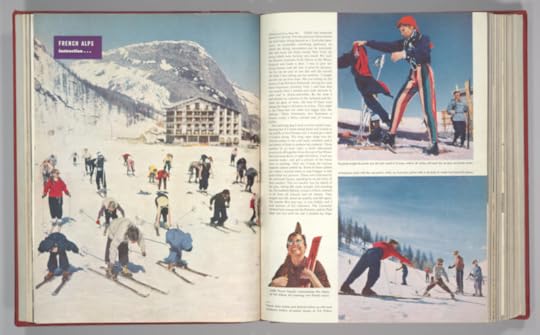

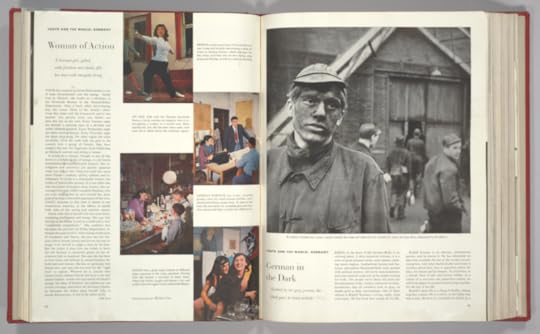

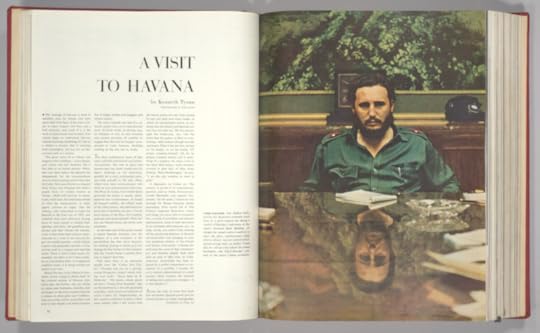

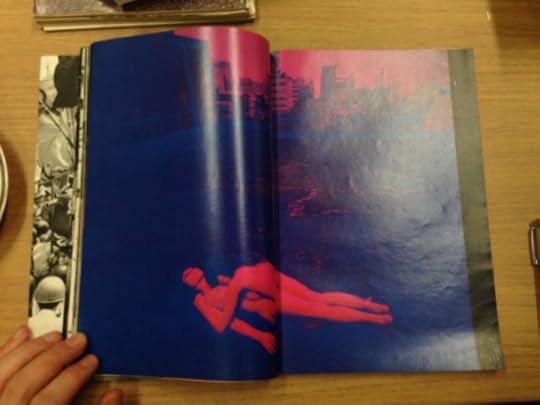

On Holiday

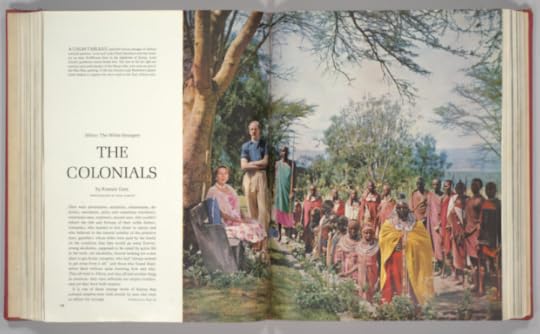

By Mary Panzer

As spring begins we revisit the pages of vintage magazine Holiday, a luxury title launched in the 1950s and became widely known for its ambitious and opulent photographic spreads. In this excerpt from Aperture magazine issue #198, Mary Panzer, a historian of photography and American culture as well as curator, tours us through the history of the former magazine, which featured photo stories spanning everywhere from Japan to Havana, by photographers among the likes of Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Elliot Erwitt. This excerpt first appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Cover photograph by Slim Aarons

Holiday magazine was launched in 1946 and appeared monthly until 1977. It was the first postwar project of Curtis Publications, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies’ Home Journal, and corporate rival of Time/Life. Holiday preserves a clear document of the growth of the American photojournalism in an era of flux. When the magazine started, there was no Cold War, no rock ‘n’ roll, no civil rights movement, and fewer than 10 percent of families in the United Sates owned a television; in just the next fifteen years, that world would be turned upside-down.

Photograph by Slim Aarons

During its best years– roughly 1951-64– Holiday regularly reported on American culture, European recovery, traditional travel spots, exotic places, playgrounds of the rich, and popular culture, including food, movies, and television. Part-Fortune, part–National Geographic, part-New Yorker and Gourmet, Holiday reflected the vision of founding editor Ted Patrick, a self-made man, a risk-taker, and an intellectual who enjoyed the good things in life. Patrick spent his early career in advertising, and served as the director of publications at the Office of War Information (OWI) during World War II before being hired by Curtis. In 1951 Patrick brought in Frank Zachary (also a OWI veteran) to be art director of Holiday. Zachary was a talented writer and graphic designer who, in the 1940s, turned the “how” magazine Minicam into Modern Photography, a lively journal for professionals and serious amateurs. Zachary was also a follower of Alexey Brodovich.

Photographs by Robert Capa

Through Holiday. Patrick promoted his belief that those lucky Americans who had survived the war had a responsibility to make something of their prosperity, productivity, and leisure. As he wrote in the pages of Holiday’s tenth-anniversary issue (March 1956): “We now have the means, money and products by which to achieve the fullest, richest life ever known to mankind, and we now have the unprecedented time of our own, which might be the greatest gift of all. What we do with that gift will decide the quality and the place in history of American Civilization.” Patrick’s confidence in the power and potential of his fellow Americans now seems like a scrap of early science fiction: a bit prescient, a bit quaint, and largely wrong.

Left: photographs by Herbert List; right: photograph by Robert Capa

Despite the magazine’s title, Holiday was not simply a guide to new vacation spots. The articles were meant to educate and enlighten. A story on Wales, for example, included gorgeous scenery, a trip through a coal mine, and a visit to a small village where music formed an important part of everyday life. Patrick seemed unconcerned by the paradox of teaching readers to seek out places and people who were not for sale, while his magazine was supported by ads for luxury commodities like cars, liquor, cigarettes, cruises, and cameras . . .

Photographs by Elliott Erwitt

From the start, photography comprised an essential element of the magazine. Patrick gave photographers generous budgets and deadlines, and very little direction. Photographers Tom and Jean Hollyman, who often worked as a pair, received these typical instructions from the managing editor: “Go to the French Riviera, Portugal, Lichtenstein, and one or two other places (we haven’t made up our minds which). Go in whatever order appeals to you. And let us know what you need in the way of research or dough.” They stayed away for a year. Burt Glinn reported the same casual generosity for his trips to Japan, the Soviet Union, and the South Seas, though his trips were shorter– only four to six months. . . .

In the early years of Holiday, color images were largely conceived and utilized in the same ways that black-and-white pictures of the 1930s had been. After Zachary arrived, the quality of photography and layout grew more sophisticated: bigger pictures, more white space, more telling details, and fewer generic vistas. Outside the magazine’s staff– which included such names as John Lewis Strange, George Leavens, Ray Atkeson, Ernest Kleinberg, Bob Smallman, Ike Vern, and Rosa Harvan– Zachary gave assignments to photographers who had special experience or access: Dan Weiner in South Africa, Bill Brandt in Scotland, Hans Namuth for art world portraits. He incorporated the cartoons of Ludwig Bemelmans, Ronald Searle, and George Giusti. Zachary claims credit for inventing a new photographic genre– the “environmental portrait,” in which a subject poses in the setting from which is power comes– as when Robert Moses stands on a steel I-beam suspended high above New York City, or Edward R. Murrow poses inside a control booth at CBS Zachary’s frequent favorites Slim Aarons and Arnold Newman used this approach on every possible occasion, even to the point of parody, as when an assignment in Africa sent Aarons to photograph white colonial rulers dressed for safari on their luxurious estates, while Newman photographed newly elected African politicians in business suits, or in remote locations, surrounded by their tribal family.

Photograph by Burt Glinn

Ted Patrick met Robert Capa around 1949, and soon after, Holiday became on of the Magnum agency’s steadiest clients. Beginning in January 1951, nearly every issue of the magazine included at least one story by a Magnum photographer. Burt Glinn, Elliot Erwitt, Dennis Stock, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and Ernst Haas contributed dozens of stories over the following two decades. On the surface, Holiday seems an uneasy match for Magnum’s mythic commitment to justice, the common people, and black-and-white photography. But Holiday suited Capa’s taste for travel and glamour, as well as his determination to create lucrative assignments for photographers. In Patrick he found an ideal patron– and poker partner. Patrick admired Capa, and in fact the entire organization, describing them in the pages of Holiday as “truly international, truly modern men… [who] had the world not only as their beat but as their living room. They were at home, sympathetically at home, wherever they opened their cameras and suitcases.”

—

Mary Panzer is a photography writer and historian. She lives in New York.

The post On Holiday appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

April 14, 2015

Tokyo Diary

Last December, Aperture magazine’s editors spent three weeks in Tokyo researching and assembling our upcoming Summer issue of the magazine, dedicated entirely to photography from Japan. This is Aperture’s second issue to be researched abroad; regular readers may remember last year’s Sao Paulo issue. Producing an international issue is an immersive process, of collecting information, of listening to local stakeholders—art historians, curators, publishers, and of course photographers—to learn about curatorial work and research underway, as well as which ideas are central to the discourse. In meetings we often ask, “What do you think we should publish, or reflect in our pages?” We then try to distill the most exciting work we’ve encountered. Tokyo’s photography scene is vast, diverse, and a little daunting, like the megalopolis. Here, we introduce some of the behind-the-scenes cast, the experts who, often very literally, sagaciously pointed the way. This article first appeared in Issue 5 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

A street in Shibuya, early in the morning, December, 2014.

Ivan Vartanian

Ivan is a former Aperture editor, who has lived in Tokyo for more than eighteen years. As an independent publisher and producer, working under the imprint Goliga, he’s worked with legends such as Daido Moriyama as well as the younger generation of image-makers. Originally our “Tokyo” issue was meant to be a modest article on the city’s independent exhibition spaces. But when Ivan described his plans to organize an ambitious conference, in New York, this spring about photography from Japan this spring, and with a number of major U.S. institutions mounting important exhibitions of Japanese photography around the same time, we knew that it was the right moment for this issue. (A grant from the Japan-United States Friendship Commission made the research-trip possible.)

Ivan, an energetic multitasker with a sardonic wit, opened many doors, sharpened our business-card etiquette, and helped introduce us to key fixtures in the Tokyo scene. While discussing possible content for the issue, Ivan mentioned his interest in Japanese photography magazines from the 1960s and ‘70s (not surprising, since he wrote a book on Japanese photography books of the era era—Aperture’s Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s, 2009). Look out for his article in this issue on the secret history of Japanese publishing, as told through tech-minded, and sometimes prurient, vintage magazines. In Japan, photography resides on the printed page.

A meeting at the Asahi Camera office. The editors kindly pulled vintage issues for us to review.

A spread from a 1969 issue of Asahi Camera, featuring a photograph by Kishin Shinoyama.

Yoko Sawada

Yoko Sawada’s cramped Ebisu office overflows with books and publishing ephemera; a vintage Nobuyoshi Araki exhibition poster welcomes visitors, once they’ve removed their shoes. If we didn’t know better, we might have suspected Sawada was publishing radical pamphlets. Formerly an editor of Déjà-Vu, a seminal photography magazine published in the 1990s, Sawada now runs an imprint, Osiris, which produces excellent photobooks, including those by Mikiko Hara and, of course, the stunning 2010 reissue of Takuma Nakahira’s For a Language to Come. Sawada helped us coordinate two features on Nakahira, in which we explore the influential Provoke-era photographer and prolific writer on images and media.

A Polaroid collage by Nobuyoshi Araki, 2014. © Nobuyoshi Araki and Eyesencia, Tokyo.

Shigeo Goto

Goto runs G/P Gallery, which has two spaces in Tokyo. One more modest space is situated in Ebisu above an excellent bookshop, and a second more capacious space is located in a peripheral warehouse area, where an exhibition of work by rising star Daisuke Yokota was on view when we visited. Goto, who works with a fresh mix of young photographers, spoke at length about photography in Japan, highlighting the idea that schools don’t play a major role in Japan (there’s no equivalent of Yale or Düsseldorf), and walked us through his thinking on photography and animism. Goto emphasized the idea that mutation was a key concept for many Japanese photographers—especially in Tokyo, where the cityscape itself is a shape shifter.

A meeting with Aperture’s editors, Daisuke Yokota, Shigeo Goto, and Ivan Vartanian, at G/P Gallery.

Hisako Motoo

As a publisher, curator, and editor, Motoo is a seasoned player in the Tokyo photo world. She has worked closely with big names like Araki and Daido Moriyama, and recently founded AM Project Space. In this gallery’s dimly lit, cavernous space we saw a dense installation of Araki’s recent collaged Polaroids, featured in the upcoming Aperture issue.

Taka Ishii

Taka Ishii Gallery is a powerhouse in the Tokyo art world, representing an impressive roster of international artists (Christopher Wool, Thomas Demand, and many others) as well as icons of Japanese photography. Ishii generously spent an afternoon with us, pulling books from his library, including a slim red volume on Minoru Hirata, who documented performance-based art in the late 1960s. Hirata’s book got us thinking about Japan’s history of photography and conceptual practice, during an era of student protest and social unrest—an underexplored area in the United States—and led us to commission an article by Yasufumi Nakamori, who has just curated a landmark exhibition For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968-79, for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which will, thankfully, travel to New York this fall.

Kotaro Iizawa

We had lunch with Iizawa, a scholar of Japanese photography, in his library/café, an elegant, minimal space built of natural wood that houses a

massive library of thousands of photobooks. Iizawa has been building his collection for decades and it is now open to the public. This incredible resource is really a gift: who needs schools, when you can learn the history of Japanese photography in Iizawa’s café?

The Araki section of Kotaro Iizawa’s photobook library. Photograph by Mie Morimoto.

Mutsuko Ota

As the editorial director of IMA, which publishes a photography magazine as well as books, Ota offered a great deal of helpful advice. We also happened to be in Tokyo at the time when IMA’s concept store in Roppongi was opening Aperture’s exhibition of books short-listed for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. Three photographers from Japan were among the finalists for the prize.

The book is the form for photography from Japan, and there’s no better place to look for books than in Jimbocho, a bibliophile’s dream neighborhood. Among other gems of ink-on-paper, we found, in a store specializing in rare maps, an early edition of Issei Suda’s beguiling, square-format photographs exploring folk traditions in late-1970s Tokyo. This reminded us that Suda, a master who was recently the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, should be introduced (or reintroduced) to Aperture’s readers.

Issei Suda, Asakusa, 1987. Courtesy Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery.

Shashin: Photography from Japan, a symposium, will be held at the New York Public Library on April 24–25. Aperture’s “Tokyo” issue, and the new issue of The Photobook Review, also focused on Japan, will be available there. Additionally, Aperture will be releasing a series of articles on Japanese photography from our archive in the weeks to come.

The post Tokyo Diary appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers