Aperture's Blog, page 163

March 18, 2015

Richard Meyer On the Term “Queer”

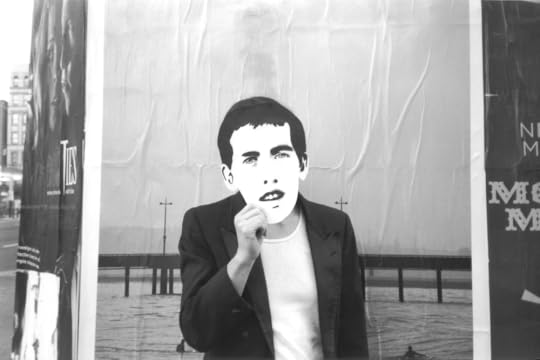

Untitled (Pier, David Wojnarowicz project), 2001–07

For the “Queer” issue, Aperture magazine asked Vince Aletti, Richard Meyer, and Catherine Opie to reflect on the term queer and its relationship with photography. Here, we run an excerpt from Meyer’s response, in which the Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor in Art History at Stanford University discusses Emily Roysdon’s restaging of David Wojnarowicz’s photographs as well as German aristocrat Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden’s carefully crafted scenes of classical homoeroticism. Tonight, Meyer will moderate Aperture’s panel discussion “Queer Genealogies” at the New School, with writer and critic Vince Aletti, associate curator of photography at the Art Gallery of Ontario Sophie Hackett, and artist K8 Hardy. The panel will explore how contemporary photographers have cast their attention backward to draw upon and engage the visual record of gay, lesbian, trans, and nonnormative sexualities. This article first appeared in Issue 3 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Although it may seem hopelessly “nineties” to some, the word queer continues to provide a crucial means of opposition. In the recent book Art and Queer Culture, written by Catherine Lord and myself [Richard Meyer], we wrote, “We have chosen the term “queer” in the knowledge that no single word can accommodate the sheer expanse of cultural practices that oppose normative heterosexuality. In its shifting connotation from everyday parlance to phobic epithet to defiant self-identification, “queer” offers more generous rewards than any simple inventory of sexual practices or erotic object choices. It makes more sumptuous the space between best fantasy and worst fear.” The last line of this passage was a reference to an early 1970s gay liberation slogan proclaiming “I am your worst fear. I am your best fantasy.” By citing this slogan within a book on queer art published in 2013, Lord and I suggest that recursive power and expansive history of queer culture.

For many years the work of queer photographers has been necessarily—if sometimes unwittingly—indebted to the sexual and subcultural imagery long preceding it. In some of the most exciting examples of such work, the photographer’s debt to queer history is openly, at times even extravagantly, acknowledged. For example, in 1991, Canadian photographer Nina Levitt partially erased a reprint of an 1891 picture by Staten Island–based amateur photographer Alice Austen of two female couples embracing, one of which includes Austen herself. The title of Austen’s original picture, That Darned Club, parrots the voice of an exasperated man excluded from the women’s intimacy while alluding, however lightheartedly, to the damnation of late nineteenth-century women who rejected the company and authority of men. Retrieving the photograph a century later, Levitt asks us to consider the visual record of lesbian life: what has been submerged that might yet be excavated or allowed to emerge. Like Levitt’s image, titled Submerged (for Alice Austen), the history of lesbian culture hovers between visibility and erasure, resolution and apparition.

Artist Emily Roysdon has initiated an equally vivid dialogue with the photographic work of a queer predecessor, in this case the late David Wojnarowicz. Across a series of twelve photographs, Roysdon both reimagines and restages Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York series (1978–79) in which a man wearing a face mask of fin-de-siècle poet Arthur Rimbaud surfaces at different locations in 1970s New York City—riding the subway, shooting up at the piers, outside an X-rated movie theater in Times Square. Although many assume the project to be self-portraiture, in fact Wojnarowicz asked a friend to wear the Rimbaud mask and then followed him to different sites throughout the city. Wearing a paper mask bearing the likeness of Wojnarowicz, Roysdon produces a touchingly inexact restaging of Rimbaud in New York. Where, for example, the original series featured “Rimbaud” masturbating on a hotel bed, we now see Roysdon pleasuring herself with a dildo. Untitled (David Wojnarowicz), 2001–2007, bespeaks both an embodied lesbian difference and a desire to create queer art across the divides of both gender and generation. Central to the logic of Roysdon’s “surrogacy” of the earlier series is the double displacement Wojnarowicz performed in the late 1970s—asking a friend, masked as a queer poet from the previous century, to stand in for the photographer’s own journey through the urban landscape.

Throughout the history of photography, queers have sought out real or fictive archives on which to base—and from which to stage—their own sexual imaginings. Living in Sicily at the end of the nineteenth century, German aristocrat Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden, for example, choreographed scenes of classical homoeroticism by photographing toga-clad (and unclad) adolescent boys and young men among fluted columns and other faux-antique props. Von Gloeden’s photographs— collected by the writer Oscar Wilde, the sexologist Alfred Kinsey, and later, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe—reveal as much about the homoerotic imagination of the late nineteenth century as about the sexual culture or customs of Greco-Roman antiquity.

Emily Roysdon, Untitled (Three Girls, David Wojnarowicz project), 2001–07. Courtesy the artist

Von Gloeden’s photographs are now hawked on the Internet as representing a lost “golden age of pornography.” Mapplethorpe’s interest in Von Gloeden was part of the former’s broader embrace of the history of pornography. Before Mapplethorpe took up photography exclusively, he was over-painting pages from gay (and occasionally straight) porn magazines. In some cases, Mapplethorpe would impose a bull’s-eye over the figure’s genitals or a black rectangular bar over the eyes, thereby referencing the criminalization and censorship of homoerotic desire as well as its persistence in the face of such threats. In other cases, such as the heretofore unpublished collage . . . the over-painting functions to focus the viewer more insistently on points of sexual exchange and homo-affection. Although Mapplethorpe’s early collages remain little known, they reflect the queer archival imagination that helped launch his photographic career.

Queer photographers working today are likewise mining the long history of gay, lesbian, trans, and otherwise nonnormative sexualities. That history reaches back to the practice of photography from its earliest moments in the nineteenth century and further still, to premodern histories of art and sexuality. As contemporary photographers continue to experiment with new forms of affiliation and technologies of representation, they simultaneously return to and reimagine the visual archives of the queer past.

Click here to subscribe to Aperture magazine and read more of Issue #218, Spring 2015, “Queer.”

The post Richard Meyer On the Term “Queer” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 17, 2015

Doug DuBois on Kickstarting My Last Day at Seventeen

Mary, Cobh, Ireland, 2011

This month Aperture launched a Kickstarter campaign to ensure the publication of My Last Day at Seventeen by Doug DuBois. When DuBois first went to Ireland, what began as a month-long residency grew into a five-year project about an exceptional group of young people from a few blocks of a housing estate in Russell Heights, in Cobh, Ireland. DuBois gained entry to the community when two of its residents took him to a local hangout spot, opening his eyes, “to a world of the not-quite adults, struggling—publicly and privately—through the last moments of their childhood.” Over the course of many summers, DuBois returned to Russell Heights to make portraits and capture spontaneous encounters and collaborative performances. If the related Kickstarter campaign is successful, in fall 2015, Aperture Foundation will publish My Last Day at Seventeen as well as a unique “community edition,” produced especially for the individuals featured in the book. Robyn Taylor, editorial consultant to the Aperture books program, spoke with DuBois about the project and how he plans to make the book a reality. This article first appeared in Issue 3 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Robyn Taylor: For those of us who don’t know, can you give us a little background on how this project began?

Doug DuBois: I came to Ireland in 2009 at the invitation of the Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh. The director of the arts center, Peggy Sue Amison, connected me with a group of young people who were interested in photography and during the course of my stay we made a Blurb book together.

A few weeks into my residency, I asked the group of kids to take me to their neighborhoods and show me around. One couple, Kevin and Eirn, who were inseparable at the time, offered to take me to “the steps,” which, as it turned out, was a drinking spot frequented by underage kids that goes back generations. Later that night, I wound up at Kevin’s house in Russell Heights, a working-class housing estate only a short walk up the hill from the steps.

I went back to Russell Heights every day after that night. I was met with a mix of curiosity and disdain; occasionally the local Garda were called out to check my ID. Since Kevin and Eirn could vouch for me, I was never seriously considered a threat or a nuisance—but that first summer was a little rough. Years later, I asked Kevin’s sister, Roisin, what people thought of me that first summer—she laughed and said. “We all thought you were a perv.”

Lenny on the Steps, Cobh, Ireland, 2009

RT: How long did it take to build a level of trust that would allow you to return each summer? Have your intentions for the project always been clear to both you and your subjects, and at what point did you decide the work should be made into a book?

DD: Kevin and Eirn were born one day apart and at the end of that first summer in Cobh, I was invited to their eighteenth birthday party. The night before, I took some photographs of Eirn in her parent’s back garden wearing a new dress—a birthday present from her father. She said at one point, “It’s my last day at seventeen,” and I knew then I had a title for the project.

When I left the party, I told everyone I’d come back the next summer with the photographs. I doubt any one expected me to live up to that promise, but when I appeared the following year with stacks of prints, a tenuous sense of trust began to develop. When people asked me what the photographs were for, I always told them there would be an exhibition at the Sirius Arts Centre and, if I was lucky, maybe a book.

Jordan up the Pole, Russell Heights, Cobh, Ireland, 2010

RT: All the images in the My Last Day at Seventeen were taken during your summer residencies. Did you ever feel like you were missing pivotal moments in the community or the kids’ lives throughout the rest of the year? How did it feel returning each year?

DD: The book depicts an eternal summer—there’s no school and the weather is mostly sunny and warm. I never set out to document, in the traditional sense of that word, the life of the community. My idea was to contemplate the threshold that marks the time between childhood and the advent of adult responsibilities. While this somewhat lyrical framework involves, at least in part, creating a portrait of these kids and their community, the end result, like an eternal summer, makes use of the fictions and metaphors about youth and coming of age.

I was excited and anxious when I returned each year—nervous, I think, for the inevitable time when I would wear out my welcome. Some of the kids changed so much from one year to the next that I didn’t recognize them; and others, who were happy to be photographed the previous summer, made it clear they had had enough.

Padjoe in his Father’s Kitchen, Cobh, Ireland, 2011

RT: Instead of a traditional text, the book will contain a short comic by Dublin-based illustrator Patrick Lynch. Can you explain how this idea came about and what you think it adds to the project? What has been your experience of working with an illustrator?

DD: I originally wanted to commission a short story from an Irish author to accompany the photographs. After I complained about getting turned down by several writers, [Aperture publisher] Lesley Martin suggested a short, graphic novel instead. I did a little research and discovered Paddy Lynch, who runs a small press and writes and illustrates these wonderful stories of life in Dublin. Nothing much happens, which I liked, but they hold a world of detail and emotional nuance.

Paddy came up to Russell Heights with me last summer to record stories as people looked at the book maquette. He made sketches and I made photographs for him to take home to Dublin. We promised everyone involved that we would combine and change details so no one person is easily recognized through their story. There are only two, unnamed characters in the comic—simply, “the girl and the boy.”

My hope for the comic is, more or less, the same as for the short story: to create a narrative that runs parallel to the sequence of photographs. The trick is to avoid any direct, illustrative relationship that shuts down or limits meaning in and between the photographs and the comic.

Doug DuBois, Dean Shows his Tat, Russell Heights, Cobh, Ireland, 2009 © Doug DuBois

RT: In the Kickstarter video, you talk about the book as being a final stage in the exchange or “gesture” of giving something back to the community. Can you talk a bit more about the importance of this gesture and how readers can help to make it a reality?

DD: Every summer, we were routinely mobbed the first day we appeared in the neighborhood with boxes of prints. We’d see them later in the summer taped up on bedroom walls and occasionally blowing about the alleys.

In the fall of 2012, I had an exhibition of the work, as promised, at the Sirius Arts Centre. There wasn’t a framed photograph in the gallery that hadn’t been given back to the person in the picture, but many people were hesitant about coming to the opening. I got questions, like “will there be posh people there?” and “will they laugh at us?” It’s one thing to look at your photograph alone or with family and friends, but it’s another to see it in public.

At the opening I taped small prints from photographs made that previous summer under the framed photographs. People who came that night could take a print off the wall and bring it home. The opening was packed with people from Cobh, Cork, Dublin, and even Belfast, but enough made the walk down from Russell Heights that most of the small prints were gone by the end of the evening. There was a steady stream during the weeks that followed —Roisin came three or four times to show off in front of her picture, and Eirn did a walkthrough at the gallery for Irish TV.

The community edition of the book is like the photographs I gave away every summer: it’s just for them to keep and share with friends, safely attached to the meanings, stories, and memories that make sense to them—no posh people allowed. The book jacket is designed to hold a single unique print, so everyone in the book gets to be on the cover.

Doug DuBois has worked as a photographer since the mid 1980s. DuBois is best known for his first monograph All the Days and Nights (Aperture, 2009)—a twenty-five year project examining the complex realm of family. He has photographed for magazines including the New York Times Magazine, Time, Details, and GQ. Doug teaches in the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University.

Robyn Taylor is an editorial consultant to the Aperture books program. Hailing from Bristol, England, she holds a BA in Documentary Photography from the University of Wales, Newport.

Tap here to support My Last Day at Seventeen on Kickstarter.

The post Doug DuBois on Kickstarting My Last Day at Seventeen appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 16, 2015

Aperture Beat: Aperture magazine “Queer” Issue Launches with Ren Hang Solo Show

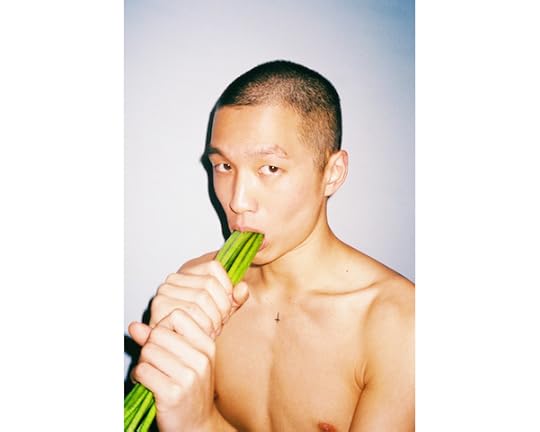

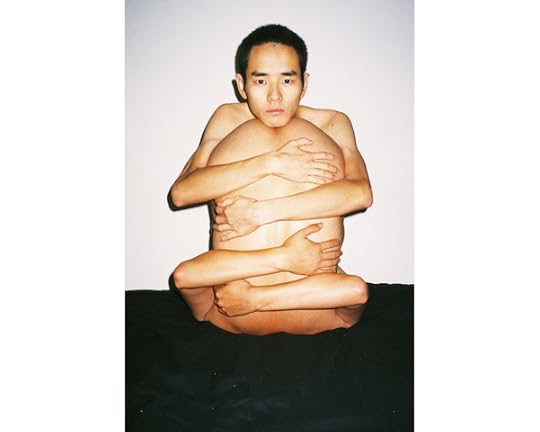

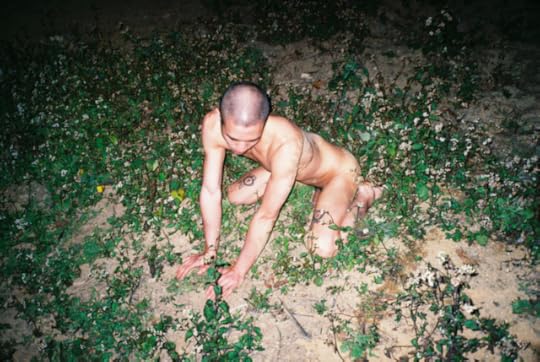

Ren Hang at Capricious 88, Photograph by Max Mikulecky

Ren Hang, whose work is featured on the cover of Aperture magazine #218, Spring 2015, “Queer,” is one of the most provocative young photographers working today in China. His photographs capture playful scenes of naked, intertwined bodies arranged into odd but elegant forms, and often his subjects’ gender is not only ambiguous but often feels beside the point. Ren Hang has published a series of photobooks that are distributed in cardboard cases that warn Chinese audiences in loud type of their explicit content. “Prominently featuring red lips, black hair, and supple flesh, his photography creates a world where sex, desire, and the joy of voyeurism create a visceral effect,” writes Stephanie H. Tung in the text accompanying his portfolio in Aperture magazine. Ren Hang is now garnering international attention and he recently opened his first exhibition in New York at Capricious 88, where Aperture also celebrated the release of Issue #218. Online editor Alexandra Pechman spoke to Ren Hang at the March 6 opening. This article first appeared in Issue 3 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Ren Hang at the opening of “Night and Day” at Capricious 88. Photograph by Max Mikulecky

Ren Hang’s first New York solo exhibition, Night and Day, may seem ironically titled, as distinctions such as darkness and light, male or female, human or landscape, often melt away in his tightly composed images of bodies at play. Limbs blend into limbs, and bodies into water, grass, or trees. In these bright, high-contrast images of hands over genitals and heads stacked on backs, Hang gives little indication of the world outside the pictures, neither physically nor politically. For the show, the gallery Capricious 88 made a selection of the Beijing-based photographer’s prolific output of untitled works, which continually gather a large following on Instagram; so continually, in fact, that despite the routine deletion of his accounts for graphic content, he currently has nearly five thousand. The opening on March 6 gave a sense of that popularity as more than a hundred gallery-goers packed the Lower East Side gallery for the dual opening and launch for Aperture magazine’s Queer issue, which features Ren Hang’s work on the cover. (At one point during the event, a broken elevator caused a line to form around the block.)

Courtesy of the artist and Capricious 88

Ren Hang was born in 1987, in northern China, and as an advertising student in Beijing, he started taking pictures of his friends. Though his photographs can often appear spontaneous— for instance, a nude man squatting animal-like in a field, a nude woman hanging off a branch while balanced on a man’s back—they are anything but. “I control the models and I tell them what to do,” Ren Hang explained at the opening, referring to his carefully directed images in which he poses and places flora and human bodies alike. He pointed out, for example, the staging the exhibition’s main image, of a naked man laying balanced on the edge of a white building, about to tip into darkness. While his models find themselves in unlikely positions as directed by the photographer, he’s developed a sense of trust with friends and strangers alike. “In the beginning when I was photographing it was all my friends,” he said. “Then when I started photographing people I didn’t know, after I had been photographing them for a while they became my friends anyway. It’s all good.”

Courtesy of the artist and Capricious 88

Such uninhibited views of friendship, sexuality, and youth are often not well received in China, where Ren Hang’s work risks censorship and obscenity charges. He has been harassed online on blogs and in person, at galleries where his exhibited works were also vandalized. This, however, doesn’t faze him. “I don’t have any particular feelings about taking photographs in China,” he said. “They limit me, but it’s not a lot. Even if they try and limit me, I’m still going to take pictures. Because I don’t care, I don’t feel it as much when I’m photographing.”

Courtesy of the artist and Capricious 88

Although bodies crowd the frame, often with bright red lips and nails, contorted, hanging, or piled on top of one another, he says he lets the images happen organically. “I never really have an idea,” Ren Hang said. “When I click, I see it, and it becomes real to me.”

Click here to subscribe to Aperture magazine and read more of Issue #218, Spring 2015, “Queer.”

The post Aperture Beat: Aperture magazine “Queer” Issue Launches with Ren Hang Solo Show appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 13, 2015

Sama Alshaibi: Sand Rushes In

Sama Alshaibi talks about her newest book, Sand Rushes In. Alshaibi’s lyrical multimedia work explores the landscape of conflict: the ongoing competition for land, resources, and power in North Africa and West Asia, and the internal battle for control between fear and fearlessness. Alshaibi uses the desert, borders, and the body as overarching symbols of the geopolitical and environmental issues and histories linking the Arab-speaking world.

The post Sama Alshaibi: Sand Rushes In appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 12, 2015

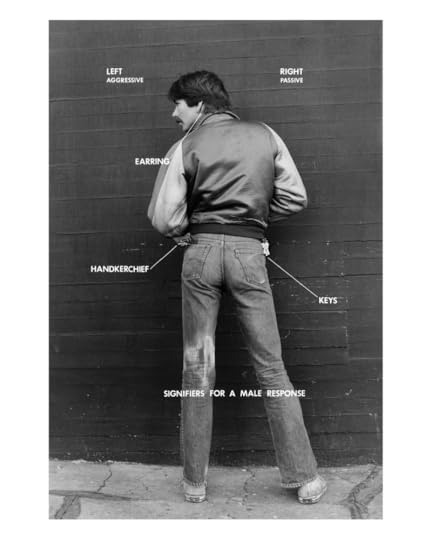

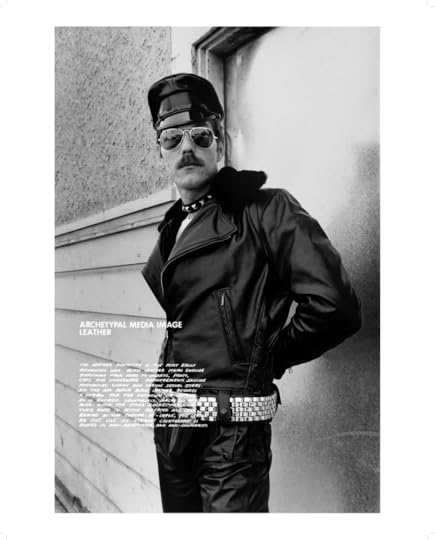

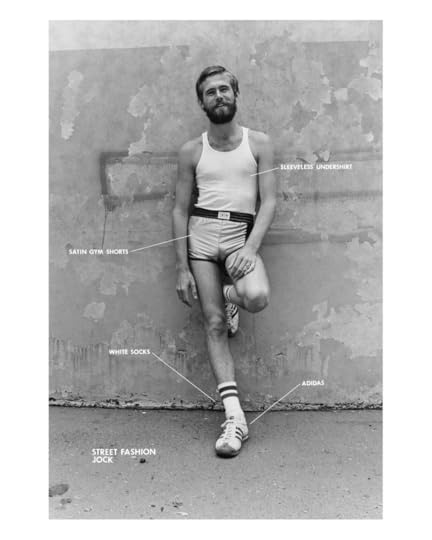

Gay Semiotics Revisited

In 1977, San Francisco photographer Hal Fischer produced his photo-text project Gay Semiotics, a seminal examination of the “hanky code” used to signal sexual preferences of cruising gay men in the Castro district of San Francisco. Fischer’s pictures dissected the significance of colored bandanas worn in jeans pockets, as well as how the placement of keys and earrings might telegraph passive or active roles. He also photographed a series of “gay looks”—from hippie to leather to cowboy to jock—with text that pointed out key elements of queer street-style. For Aperture magazine #218, Spring 2015, “Queer,” art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson spoke with Fischer about the origins of Gay Semiotics and how it has aged, excerpted below. This article also appears in Issue 2 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the free app.

Julia Bryan-Wilson: You initially trained as a photographer at the University of Illinois. What brought you to the Bay Area, and what impact did that move have on your work?

Hal Fischer: I came here for graduate school in photography at San Francisco State in 1975. I really wanted to study with Jack Fulton, but I didn’t want to pay the money to go to the Art Institute. I figured that I could probably work with him as long as I was here. After I moved to the Bay Area, two pivotal things happened. One was that I began writing for Artweek three months after I arrived, so I immediately got into the fray, so to speak. The second pivotal thing was meeting Lew Thomas [cofounder of NFS Press]. That was incredibly critical.

JBW: What strikes me now about Gay Semiotics is how conceptual it is, how important the photo-text relationship is.

HF: When I applied to State, I applied with traditional photography, gelatin-silver prints mainly of the landscape. Then I got out here, and the first thing I started doing was crazy alternative work, predominantly 20-by-24-inch bleached prints with inked-on text and diagrammatic drawings. But I met Lew through my writing, because I reviewed a show of his, and he was at the center of a movement focused on connecting photography and language.

JBW: What was the Bay Area like in terms of a photography scene in the mid to late 1970s?

HF: There was a huge discourse here. You’d have an opening, and there would be two hundred people there. People talked about photography. They were really interested, and it was passionate.

JBW: Gay Semiotics is an attempt to map some of the discourse of structuralism onto the visual codes of male queer life in the Castro. How did you come to structuralism?

HF: Thanks to Lew Thomas, in graduate school I began reading things like Jack Burnham’s The Structure of Art and Ursula Meyer’s Conceptual Art. Those were two key texts. Of course, structuralism came late to photography, when you consider that Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation came out in 1966. Reading Burnham, going on to read Claude Lévi-Strauss, all that was crucial. I learned about signifiers, and thought, This is going on all around me.

JBW: In your bibliography for Gay Semiotics, you cite Walter Benjamin, but not Roland Barthes. Who else were you influenced by?

HF: I did read some Roland Barthes, but it’s almost like I read just enough. The signifiers were the first pictures to come out of this thinking. It was like, Oh my God, these handkerchiefs . . . this is exactly what they are writing about. Of course, that made for five pictures, and then I had to figure something out from there.

All photographs by Hal Fischer from Gay Semiotics, 1977 © and courtesy Hal Fischer, and Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles

JBW: You’re doing several things in Gay Semiotics. On the one hand, you’re parsing a signification system that arose out of a nonverbal, erotic exchange, and you’re also deconstructing gay male self-fashioning and photographing “archetypes.” It is thus a photo-project about the history of photography and its long legacy of ethnographic typing.

HF: I can’t say I was conscious of it at the time, but one of the first photographers who influenced me was August Sander. I mean, I LOVED Sander. I still do. I probably was a fascist in an earlier life, because I’m definitely into types, and I’m definitely into archetyping. I don’t really think it’s that awful a thing to do; it can be very informative. I was also interested in the Bechers and the notion of repetition.

JBW: So the work is also about genre.

HF: Yes. It’s also about personal desire; it’s a lexicon of attraction.

The post Gay Semiotics Revisited appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 10, 2015

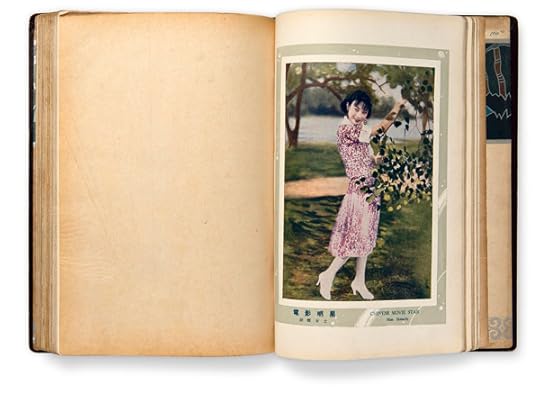

A Look Inside The Chinese Photobook

Aperture’s new exhibition The Chinese Photobook reveals for the first time the richness and diversity of the photobook’s heritage in China, drawing on publications from over a century of Chinese history. From imperial China to the Cultural Revolution to the present day, Chinese photobooks have reflected the dramatic changes of China’s twentieth century. Based on a collection compiled by Martin Parr and Beijing- and London-based Dutch photographer team WassinkLundgren, to be published this spring from Aperture. The Chinese Photobook embodies the dramatic changes in China in the twentieth century. Here, we present a look inside the exhibition with some of the key figures involved in the making of the book, who led a private tour at the Member’s Preview before the exhibition opening on February 11.

The Chinese photobook reveals as much about Chinese photography as about China itself, and the country’s dramatic twists and turns during the last one hundred years. Divided into six sections, the exhibition now on view at the Aperture Gallery in New York, through April 2, chronologically traces the development of the form in China since 1900, from imperial souvenirs, to government propaganda, to the contemporary avant-garde. “Each book is a microcapsule of history,” said Aperture publisher Lesley A. Martin. Just before the exhibition’s opening, three of the book’s contributors— Raymond Lum, Stephanie H. Tung, and Ruben Lundgren—spoke about their contributions to the exhibition. Lum, librarian for Western languages in the Harvard-Yenching Library, wrote about the book’s first chapter, which explores how the imperial agendas in China in the early twentieth century gave way to the People’s Republic of China. For example, French forces sent during the Boxer Rebellion of 1901 took some of the earliest aerial photographs of China, adorned with Art Deco and Art Nouveau flourishes in a loosely bound and “clever” book, as Lum described, which could be taken apart and rearranged.

Slipcase and folio from La Chine à terre et en ballon (Paris: Berger-Levrault & Cie., 1902)

Interior selection from The Living China: A Pictorial Record (Shanghai: Liang You Publishing Co., 1930)

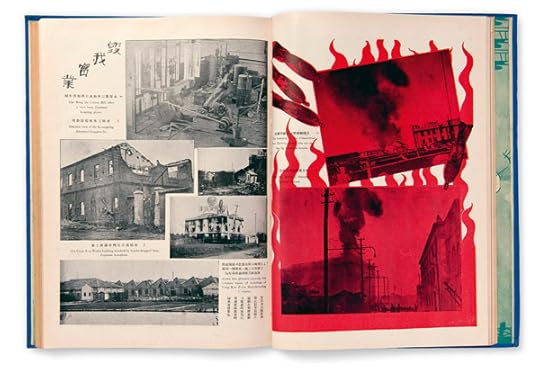

Tung, who is working toward a dissertation on the history of photography in China, spoke about the period between 1931 and 1947, which alternately produced photobooks reflecting more artistic practices as well as the effects of the Sino-Japanese war. Tung highlighted the work of Lang Jiangshan, arguably one of the most famous photographers in Chinese history, who pushed limits of representation in the 1930s and 1940s. Of his layered negatives of landscapes and nudes, Tung remarked that the photographer aimed to evoke the texture of classical Chinese landscape paintings: “He’s trying to express a Chinese essence through photography.” The Japanese occupation introduced some of the first propaganda-style photobooks, in praise of Manchuria, made by Japanese publishers; meanwhile, books of response by Chinese publishers depicted a nation torn apart by war.

Interior selection from Pictorial Review of the Sino-Japanese Conflict in Shanghai (Shanghai: Wen Hwa Fine Arts Press, Ltd., 1932)

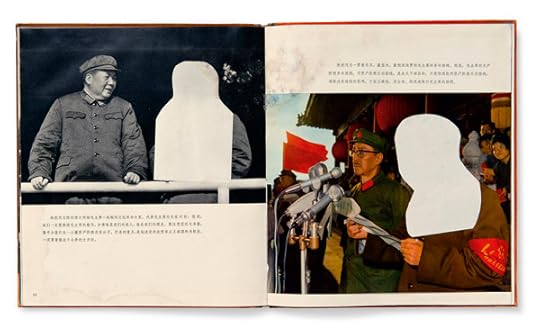

Lundgren, of WassinkLundgren, illuminated Chinese Communist propaganda in the post-1943 period that preceded the rise of Mao. Photography remained extremely important to the image of a prosperous China; Mao later had his own personal photographer. Joyous, but largely anonymous, images of progress characterize the period. The Cultural Revolution of 1966 brought about its own unique style of imagery, emblazoned with portraits of the communist leader. “What you’ll see is, I collect these books, all different times of censorship, especially crosses,” Lundgren added, pointing to an image of Mao and another man, who has been cut out of the image. “It’s a very good example of the craziness of its time.”

Interior selection from Chairman Mao is the Red Sun in Our Hearts (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1967)

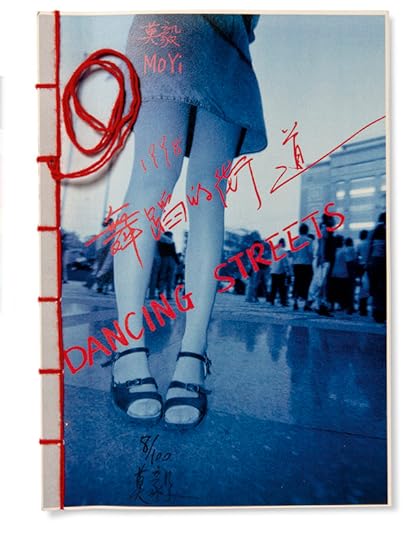

After the death of Mao, these books changed dramatically, even as photographers began to capture scenes of public grief. “You see the first instances of young photographers not working within a particular political ideology, not on political assignments, creating their own photobooks,” Tung said. Also on view is the catalog from China’s first free photography exhibition during this period. “We see photobooks go from completely commercial to experimental to die-hard journalism,” Lundgren added. “It goes in every single direction imaginable.”

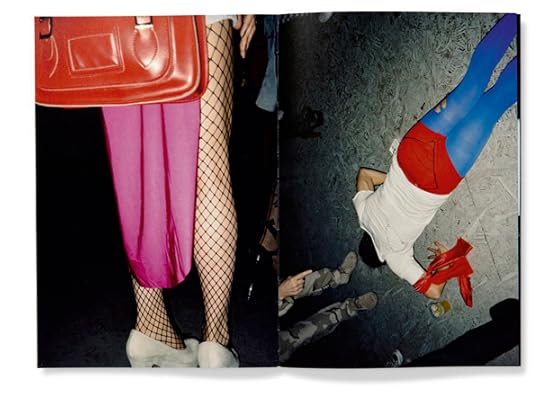

Interior selection from No. 223 by Lin Zhipeng (Taipei: Revolution-Star Publishing and Creation Co., Ltd., 2012)

Cover from Dancing Streets by Mo Yi (self published,1998)

The contemporary selection of photobooks in particular gives a sense of the range of what might be uncovered between these photobooks’ covers, from photojournalism that exocitizes the West to the provocative work of Ren Hang. Through the project, Aperture magazine’s editors discovered Ren’s photobooks, which are distributed in cardboard cases warning readers of their content. Not only did the work end up in the pages of the magazine’s new spring issue, “Queer,” but, in an apt reversal, it’s on the cover.

The post A Look Inside The Chinese Photobook appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 9, 2015

Artist Talk: Erica Baum

On Tuesday, February 24th photographer Erica Baum gave an artist talk at Aperture gallery. Drawing inspiration from contemporary artists who utilize text, such as Ed Ruscha and Lawrence Weiner, along with documentary-style photographers such as Walker Evans and Eugène Atget, Baum creates what have been called “subliminal narratives” using found words and images from paperback books, card catalogues, and paper rolls from player pianos, among other literary artifacts. Baum’s work is featured in Aperture magazine’s “Lit.” issue.

The post Artist Talk: Erica Baum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 6, 2015

The Armory Show: 11 Photography Picks

The Armory Show officially kicks off this week at Piers 92 and 94 in Manhattan, with 199 galleries from over twenty-eight countries participating in this year’s edition. Below, we highlight some standout photography from around the fair, ranging from documentary photographs from the Civil Rights movement to abstraction, including a series of portraits featured in the newest issue of Aperture magazine. Be sure to also check out Aperture Foundation at Booth 827 on Pier 94.

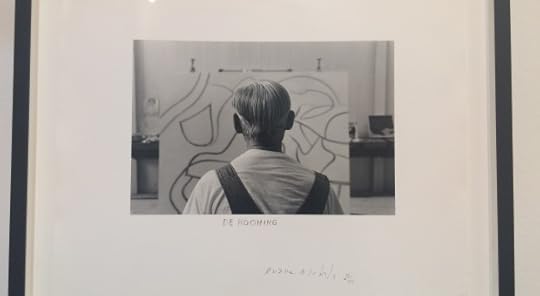

Duane Michals, Willem de Kooning, 1985

DC Moore Gallery devoted a wall of its booth to the work of Duane Michals, recently the subject of a retrospective at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Among the works featured are Michals’s portraits of artists, from Willem de Kooning to Rene Magritte to Andy Warhol.

Gordon Parks, Outside Looking In, 1956

The presentation at at Howard Greenberg Gallery focused on color photography from the Civil Rights movement as well as the work of prominent African-American photographers such as Gordon Parks, whose work for the Time photo-essay “Back to Fort Scott” is currently on view at the MFA Boston.

Thomas Ruff, ch.phg.06, 2014

In the contemporary wing of the show, David Zwirner Gallery has a major focus on photography at the fair this year, featuring large-scale photographs by Thomas Ruff from his Photograms and Stars series as well as smaller work from his Negatives series. (Read a recent review of Ruff’s exhibition in Düsseldorf.)

Work from Chris McCaw’s Sunburned series.

Yossi Milo also has abstract photography on view, with selections from Chris McCaw’s Sunburned series, for which the artist allows hours of sun exposure onto light-sensitive negatives, causing solarization—they are literally holes burnt into the image.

Photographs by Zanele Muholi at Yancey Richardson’s booth.

At Yancey Richardson, portraits by the South African photographer Zanele Muholi are on view—many of the works appear in the new issue of Aperture magazine, “Queer,” alongside an interview with Muholi about her depictions of the gay and lesbian community in South Africa. She will have her first large-scale exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in May this year.

Alfredo Jaar, Angel, 2007

At Lia Rumma from Milan, Italy, a large-scale Alfredo Jaar photograph dominated the booth.

Alec Soth, Crazy Legs Saloon. Watertown, New York, 2012

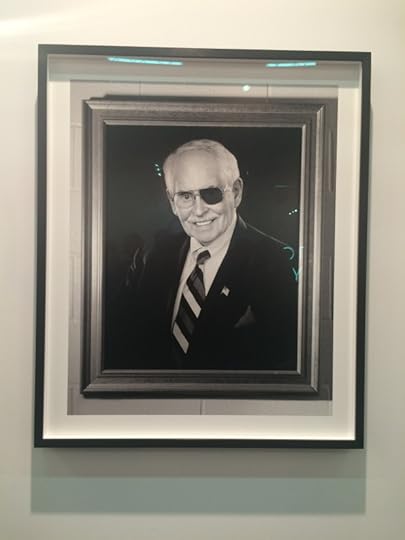

Alec Soth, Robert E. “Bob” Waitt. College Station, Texas, 2013

Sean Kelly is showing multiple photographs by Alec Soth, who headlined Aperture’s 2014 Benefit.

Mona Hatoum, Four Birds (Baalback), 1998.

At Alexander and Bonin, Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum’s art and photography rounded out the Armory Focus section, which this year centers on the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean (MENAM).

Talia Chetrit, parents in the sun #1, 2014

Sies + Höke from Düsseldorf showed the work of Talia Chetrit at their booth. The New York–based artist often repurposes photographs from her family archives, re-cropping, zooming, and rearranging them to create new juxtapositions of past and present.

The post The Armory Show: 11 Photography Picks appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In Memoriam: Albert Maysles

In memory of legendary documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles, who died today at age 88, we revisit his tribute to friend Henri Cartier-Bresson, originally published in Aperture magazine issue 191, Summer 2008.

Henri Matisse at his home, villa “Le Rêve” in Vence, France, February 1944 © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

This famous photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson—of Matisse with white doves—is my favorite. Cartier-Bresson was an old friend whom I met through Bruce Davidson. When Bruce invited us both to his studio, he asked me to bring along a projector and a scene from one of my films. The scene I had filmed was of a train coming into the Moscow station, from which trains go off to Siberia. As the train pulled in alongside the empty platform I stood with my camera mounted with an extreme 300mm telephoto lens. As I began shooting—because it was illegal to film in train stations in the USSR—an angry Soviet army officer came rushing over to stop me. I grabbed him by the back of the neck and stuck his eye to the viewfinder. At that moment, with the camera still rolling, the train came to a stop and hundreds of people came rushing out of the doors. With a big smile on his face, the officer congratulated me. He had been converted. When Henri saw the film he too got excited, and leapt up and applauded.

Some years later when I was about to get married, Henri offered any one of his photographs as a wedding present. I chose this Matisse photograph. To me it was as if Henri were expressing in his own way Robert Capa’s advice to get close—get very close. Henri’s special talent in getting close was to stay far enough away to include the doves, which brought the viewer that much closer to the peaceful and sublime nature of Matisse himself—so superior to a shot of Matisse’s face in isolation.

And so film and the photograph brought me that much closer to both Matisse and Henri.

The post In Memoriam: Albert Maysles appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Archive: “Photography, Pornography, and Sexual Politics”

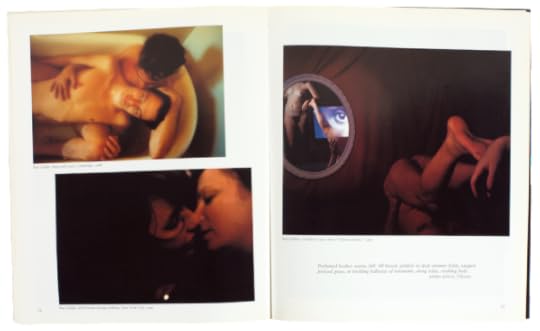

Interior pages from Aperture magazine #121, “The Body in Question,” 1990

The following excerpt comes from Aperture #121, “The Body in Question,” 1990, an issue that explored depictions of the body in photography in the face of “a powerful effort…to define and control expressions of sex and sexuality.” In one of the defining moments of the Culture Wars, conservative politicians sought to defund the National Endowment for the Arts after it supported an exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center, in Cincinnati, of works by Robert Mapplethorpe that included graphic sexual content. In conjunction with the release of Aperture #218, “Queer,” we revisit a piece written in response to this cultural flashpoint by Carole S. Vance, associate clinical professor of socio-medical sciences at Columbia University, who has written widely on sexuality and human rights. While the Culture Wars happened twenty-five years ago, debates surrounding depictions of the body and sexuality continue today. This article also appears in Issue 2 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

The art world was taken by surprise by the furor over the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) funding of exhibitions containing photographs by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, which began in the summer of 1989, and, more recently, by the indictment of Dennis Barrie, director of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Ohio and the CAC itself in conjunction with the opening of Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment last April. Observers were then startled to find fine-arts photography the target of attack, called pornographic, even “obscene,” because of its sexual or erotic content. Some wondered if a time-machine had catapulted them back to the late nineteenth century, when moral crusaders assailed museums and galleries for displaying nude statues and paintings. This new campaign against photography and sexual imagery is far from an anachronism, however. It is the systematic extensions of conservative and fundamentalist cultural politics to the world of “high culture,” a domain that had previously been exempt from their carefully organized public crusades.

In the past ten years, conservatives and fundamentalists have crafted and deployed techniques of grass-roots and mass mobilization around issues of sexuality, gender and religion. In these campaigns, symbols figure prominently, both as highly condensed statements of moral concern and as powerful spurs to emotion and action. In moral campaigns, fundamentalists select a negative symbol that is highly inflammatory to their own constituency and that is difficult or problematic for their opponents to defend, for example, exaggerated and distorted fetal images in anti-abortion propaganda. These groups have orchestrated major actions in the realm of popular culture—the protests against Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ motivated by the Reverend Donald E. Wildmon, campaigns against rock music led by Tipper Gore and the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center), and the Meese Commission’s war against pornography. Ironically, these growing crusades come at a time when fundamentalist victories in electoral politics are decreasing and perhaps signal the conservatives’ recognition that social programs, which could not be attained through conventional politics, could still succeed through more long-term, though admittedly slower, attempts to change the cultural environment.

The recent attacks on photography mark the first time that such mobilizations have been so overtly directed at “high” culture. The targeting of photography by right-wing religious and political leaders like Wildmon and Jesse Helms is not accidental: it is probably the weakest brick in the fine-arts edifice. A relatively recent historical arrival, photography does not yet have the prestige surrounding painting or sculpture, and photography’s institutions, also comparative newcomers, have fewer resources and less authority. In addition, a significant amount of photography circulates through galleries, without the imprimatur of museums. Contemporary photographers and their works remain unprotected, since there has been less time in which to develop a consensus about their value—financial, artistic, and cultural.

Photography is also less privileged than other fine arts because of its ubiquity. The proliferation of of photographic images in everyday life and mass culture—in advertising and photojournalism—makes it more difficult to shelter photography, even if one wanted to, under the protective umbrella of seemingly rarified and prestigious high culture. Finally, the realistic quality of photographic representation makes it especially vulnerable to the conservative analysis of representation, which is characterized by extreme literalism. For all these reasons, the choice of photography in a newly launched conservative movement against the fine arts was shrewd. Indeed, it may have been the only plausible target: imagine, for example, public response to a campaign to remove The Origin of the World, 1866, from the Brooklyn Museum’s 1988 Courbet retrospective.

The post Archive: “Photography, Pornography, and Sexual Politics” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers