Aperture's Blog, page 152

September 23, 2015

Report: On Hugh Mangum

By Sarah Stacke

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Hugh Mangum, self-portrait. Mangum grasped the power of photography to communicate information or a narrative. He’s using this series to express his identity and personality, and understood that many clients would be seeking the same.

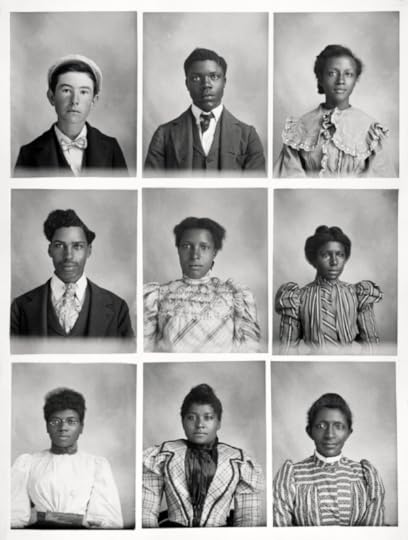

Inside or outside his photo studio, Hugh Mangum created an atmosphere—respectful and often playful— in which hundreds of men, women, and children genuinely revealed their spirits. Born and raised in Durham, North Carolina, Mangum began establishing studios and working as an itinerant photographer in the early 1890s, traveling by rail through his home state, Virginia, and West Virginia. Mangum attracted and cultivated a clientele that drew heavily from both black and white communities. Though the early-twentieth-century American South in which he worked was marked by disenfranchisement, segregation, and inequality—between black and white, men and women, rich and poor—Mangum portrayed all of his sitters with candor, humor, and spirit. Above all, he showed them as individuals, and for that, his work—largely unknown—is mesmerizing. Each client appears as valuable as the next, no story less significant.

Mangum’s life was brief, yet it encompassed momentous shifts amid a turbulent period in American history. Born in 1877, the year the Civil War’s Reconstruction period ended, Mangum died from influenza in 1922, only three years after the end of the First World War and two years after women gained the right to vote. The personalities in Mangum’s images collectively, and often majestically, symbolize the triumphs and struggles of this pivotal era.

A century after their making, Mangum’s images allow us a penetrating gaze into individual faces of the past, and in a larger sense, they offer an unusually insightful glimpse of the early-twentieth-century American South. What follows are facets of this rich collection.

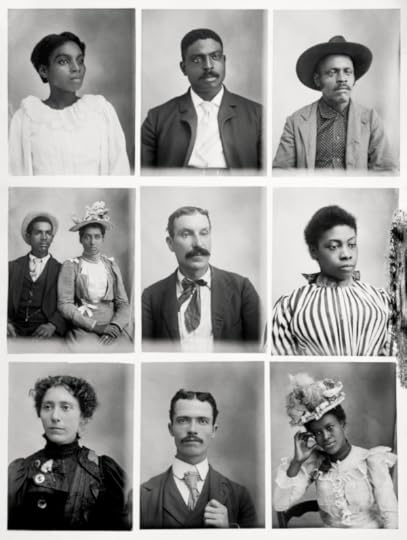

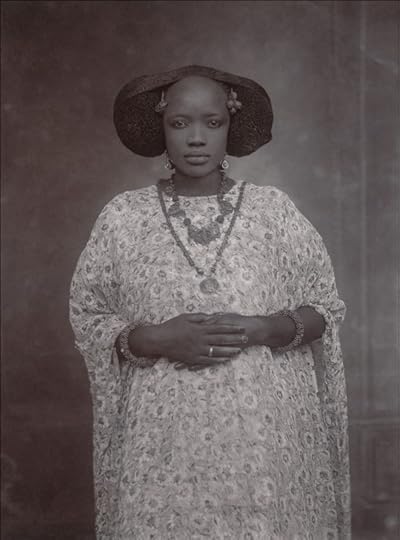

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Durham was known to have an unusually prosperous black community. Black-owned businesses included the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, Mechanics and Farmers Bank, furniture, cigar, and tobacco factories, textile and lumber mills, brickyards, churches, a library, schools, and a hospital. North Carolina Central University, an institution that throughout the Jim Crow era provided professional development for black residents of Durham and beyond, was founded in 1910.

Women

Near the end of the nineteenth century, women on both sides of the color line began to dismantle the barriers that separated the male and female worlds. As the New Woman of the 1890s emerged, the terms of masculinity and femininity were questioned, causing considerable debate and self-reflection. Women claimed the right to education, found employment in positions that were previously reserved for men, and demanded the right to vote. Many women earned their own wages; some lived independently. Political, religious, educational, social, and work-related clubs, both private and public, were formed by women from all walks of life as they redefined their roles in society and as individuals.

The bicycle played a considerable role in female emancipation and subsequently in fashion, as women preferred clothing that allowed more movement. The bicycle embodied the freedom, independence, and mobility of the New Woman. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony exclaimed, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel . . . the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: In this image a young woman balances precariously on her bicycle. The instability captured here perhaps brings her back to the first time she rode a bike, exploring the freedom and mobility it bestowed.

Technology

Over the course of thirty years, Mangum used several types of cameras and formats.

He often used a Penny Picture Camera, which allowed multiple and distinct exposures on a single glass plate negative. Depending on the circular or square template, one glass plate might contain anywhere from six to twenty-four images. This was ideal for creating inexpensive novelty pictures as multiple sitters could be photographed on one negative, reducing cost and labor.

Notably, the Penny Picture Camera worked in a step-and-repeat process in which the negative holder was repositioned behind the lens after each exposure. As a result, the order of the images on the negatives represents the order in which Mangum’s diverse clientele rotated through the studio, the negatives reasonably representing an afternoon or day’s work for this gregarious photographer.

Black Community

There are no indications that Hugh Mangum intended his photographs to serve any political purposes, but it is likely that for many of his sitters, in fact they did. By the turn of the twentieth century, African Americans had long engaged the power of photography in order to challenge racial ideas, as well as to visually create and celebrate black identity. Mangum’s sitters used the images to emphasize accomplishments, prosperity, beauty, and individuality. They shared them with friends and made them the foundation of family photo albums, ultimately shaping their own identities and those of future generations.

Mangum lived during the same period as acclaimed black thinkers like Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Zora Neale Hurston. These were some of the most difficult years in African American history. Although there are no tidy dates separating the phases and forms of racial discrimination, the removal of federal troops at the end of Reconstruction was arguably the advent of Jim Crow laws, and lynching peaked in the 1890s. Yet at the same time Mangum was making portraits, members of the black community were building on the strength of their own values and institutions, and cultivating resistance to laws and customs that excluded them.

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Durham was known to have an unusually prosperous black community. Black-owned businesses included the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, Mechanics and Farmers Bank, furniture, cigar, and tobacco factories, textile and lumber mills, brickyards, churches, a library, schools, and a hospital. North Carolina Central University, an institution that throughout the Jim Crow era provided professional development for black residents of Durham and beyond, was founded in 1910.

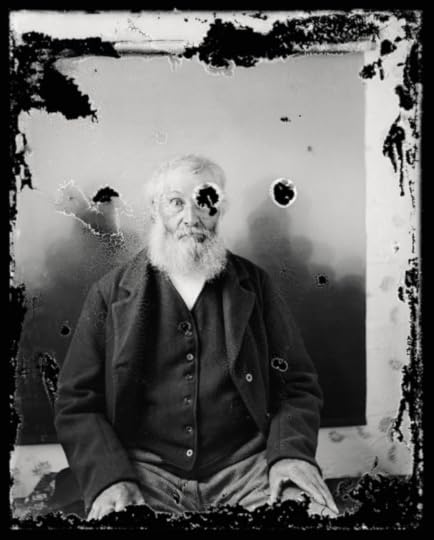

Deterioration

During Mangum’s lifetime he likely exposed thousands of glass plate negatives. Most of them were destroyed through benign neglect after his death or are now lost, as were almost all records of the names and dates associated with them. The images that survived—nearly eight hundred glass plate negatives—were salvaged from the tobacco pack house where Mangum built his first darkroom. For decades, the negatives caught the droppings of chickens and other creatures living in the pack house. Today they are in various states of an ongoing deterioration; even the most controlled environment cannot halt the creeping decay. The effect can be poetic, adding a layer of meaning to the image that would otherwise be absent. Some plates are broken and on others the emulsion is peeling away, but the hundreds of vibrant personalities in the photographs prevail, engaging our emotions, intellect, and imagination.

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: In this image, the surprised expression on the man’s face fits perfectly with the position of the deterioration that befell the negative on which he is photographically etched.

Sarah Stacke is writing a book about Hugh Mangum’s life and work.

The post Report: On Hugh Mangum appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 18, 2015

The 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

On Friday evening, September 18, at the New York Art Book Fair, the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist was announced after two days of deliberation by the short list jury, consisting of Yannick Bouillis, founder of Offprint Projects; Julien Frydman, director of development at the LUMA Foundation; Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation; Mustuko Ota, editor-in-chief of IMA magazine; and Christophe Weisner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

The thirty-five books—plus one special jury mention for a facsimile reproduction of the classic Japanese book, Chizu (The Map) by Kikuji Kawada—are listed below. Thank you to everyone who entered! There was an overwhelming response, with over 1,000 books from over sixty countries submitted. More information on all the titles to come soon, here on-line and in the next issue of The PhotoBook Review.

PHOTOGRAPHY CATALOGUE OF THE YEAR

Beastly/Tierisch

Duncan Forbes, Matthias Gabi, and Daniela Janser

Spector Books/Fotomuseum Winterthur

A Guide for the Protection of the Public in Peacetime

Timothy Prus, Ed Jones, and David Alan Mellor

Archive of Modern Conflict

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence

Diane Dufour and Xavier Barral

Le Bal/Éditions Xavier Barral

TR Ericsson: Crackle & Drag

TR Ericsson, Arnaud Gerspacher, and Barbara Tannenbaum

Yale University Press/Cleveland Museum of Art

William Eggleston: A Cor Americana

Thyago Noguiera

Instituto Moreira Salles

FIRST PHOTOBOOK OF THE YEAR

Annette Behrens

(in matters of) Karl

Fw:Books

Noa Ben-Shalom

Hush: Israel Palestine 2000–2014

Sternthal Books

Sophie Bramly

Walk This Way

Galerie 213

Matthew Connors

Fire In Cairo

SPBH Editions

Iñaki Domingo

Ser Sangre

RM Verlag/La Kursala/Here Press

J. W. Fisher and J. T. Leonard

Landmark

Daylight

Dominic Forde

Ramps, Pools, Ponds and Pipes

Self-published

Siegfried Hansen

Hold the Line

Verlag Kettler

Lucy Helton

Transmission

Silas Finch

Benoît Jeannet

A Geological Index of the Landscape

Self-published

Sjoerd Knibbeler

Paper Planes

Fw:Books

Madeleine Kotte and Cornelius de Bill Baboul

5 PTOHOGRAHPIES—40 × 28 CM

The Ptohograhpies

Daniel Mayrit

You Haven’t Seen Their Faces

Riot Books

Katarzyna Mazur

Anna Konda

dienacht Publishing

Gilles Raynald

Jean-Jaurès

Purpose Éditions

Paweł Szypulski

Greetings from Auschwitz

Edition Patrick Frey/Foundation for Visual Arts

Hiroshi Takizawa

Mass

Newfave

Maurice van Es

Now Will Not Be With Us Forever

RVB Books

Adrian Octavius Walker

My Lens, Our Ferguson

Self-published

Akihito Yoshida

Brick Yard

Self-published

PHOTOBOOK OF THE YEAR

Anthony Cairns

LDN EI

Self-published

Dana Lixenberg

Imperial Courts 1993–2015

Roma Publications

Thomas Mailaender

Illustrated People

Archive of Modern Conflict/RVB Books

Mike Mandel

Good 70s

J&L Books/D.A.P.

Tod Papageorge

Studio 54

Stanley/Barker

Christian Patterson

Bottom of the Lake

Walther König

Fazal Sheikh

Erasure

Steidl

Will Steacy

Deadline

b.frank books

Daisuke Yokota

Taratine

Session Press

Xu Yong

Negatives

New Century Press

JURORS’ SPECIAL MENTION

Kikuji Kawada

Chizu (The Map)

Akio Nagasawa

The post The 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Announcing the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

On Friday evening, September 18, at the New York Art Book Fair, the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards shortlist was announced after two days of deliberation by the short list jury, consisting of Yannick Bouillis, founder of Offprint Projects; Julien Frydman, director of development at the LUMA Foundation; Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation; Mustuko Ota, editor-in-chief of IMA magazine; and Christophe Weisner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

The thirty-five books—plus one special jury mention for a facsimile reproduction of the classic Japanese book, Chizu (The Map) by Kikuji Kawada—are listed below. Thank you to everyone who entered! There was an overwhelming response, with over 1,000 books from over sixty countries submitted. More information on all the titles to come soon, here on-line and in the next issue of The PhotoBook Review.

PHOTOGRAPHY CATALOGUE OF THE YEAR

Beastly/Tierisch

Duncan Forbes, Matthias Gabi, and Daniela Janser

Spector Books/Fotomuseum Winterthur

A Guide for the Protection of the Public in Peacetime

Timothy Prus, Ed Jones, and David Alan Mellor

Archive of Modern Conflict

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence

Diane Dufour, with Émilie Hanmer

Le Bal/Éditions Xavier Barral

TR Ericsson: Crackle & Drag

TR Ericsson, Arnaud Gerspacher, and Barbara Tannenbaum

Yale University Press/Cleveland Museum of Art

William Eggleston: A Cor Americana

Thyago Noguiera

Instituto Moreira Salles

FIRST PHOTOBOOK OF THE YEAR

Annette Behrens

(in matters of) Karl

Fw:Books

Noa Ben-Shalom

Hush: Israel Palestine 2000–2014

Sternthal Books

Sophie Bramly

Walk This Way

Galerie 213

Matthew Connors

Fire In Cairo

SPBH Editions

Iñaki Domingo

Ser Sangre

RM Verlag/La Kursala/Here Press

J. W. Fisher and J. T. Leonard

Landmark

Daylight

Dominic Forde

Ramps, Pools, Ponds and Pipes

Self-published

Siegfried Hansen

Hold the Line

Verlag Kettler

Lucy Helton

Transmission

Silas Finch

Benoît Jeannet

A Geological Index of the Landscape

Self-published

Sjoerd Knibbeler

Paper Planes

Fw:Books

Madeleine Kotte and Cornelius de Bill Baboul

5 PTOHOGRAHPIES—40 × 28 CM

The Ptohograhpies

Daniel Mayrit

You Haven’t Seen Their Faces

Riot Books

Katarzyna Mazur

Anna Konda

dienacht Publishing

Gilles Raynald

Jean-Jaurès

Purpose Éditions

Paweł Szypulski

Greetings from Auschwitz

Edition Patrick Frey/Foundation for Visual Arts

Hiroshi Takizawa

Mass

Newfave

Maurice van Es

Now Will Not Be With Us Forever

RVB Books

Adrian Octavius Walker

My Lens, Our Ferguson

Self-published

Akihito Yoshida

Brick Yard

Self-published

PHOTOBOOK OF THE YEAR

Anthony Cairns

LDN EI

Self-published

Dana Lixenberg

Imperial Courts 1993–2015

Roma Publications

Thomas Mailaender

Illustrated People

Archive of Modern Conflict/RVB Books

Mike Mandel

Good 70s

J&L Books/D.A.P.

Tod Papageorge

Studio 54

Stanley/Barker

Christian Patterson

Bottom of the Lake

Walther König

Fazal Sheikh

Erasure

Steidl

Will Steacy

Deadline

b.frank books

Daisuke Yokota

Taratine

Session Press

Xu Yong

Negatives

New Century Press

JURORS’ SPECIAL MENTION

Kikuji Kawada

Chizu (The Map)

Akio Nagasawa

The post Announcing the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 16, 2015

Patrick Faigenbaum: Kolkata/Calcutta at Aperture Gallery

Kolkata/Calcutta, an exhibition of new photographs by Patrick Faigenbaum, inaugurates the newly founded alliance between the Hermès Foundation and Aperture Foundation. The opening reception will be held September 16, 7:00–8:30 p.m. Faigenbaum will appear in conversation with Chris Boot at the gallery on September 22 at 6:30 p.m.

In the Santiniketan Express, the train that connects the station in Howrah, Kolkata, with the city of Bolpur, May 2014. All photographs © Patrick Faigenbaum

Dover Lane, Ballygunge, south Kolkata, October 2014

The great crossroads of Gariahat, which is straddled by the city highway, south Kolkata, October 2014

The folk singer Saurav Moni at home with his group, Dum Dum, north Kolkata, July 2014

New Market (a British construction) seen from room 239 of the second floor of the Oberoi Grand Hotel, during the monsoon, central Kolkata, July 2014

Mrs. Kalyani Ghosh, Banamali Sarkar Street, north Kolkata, October 2014

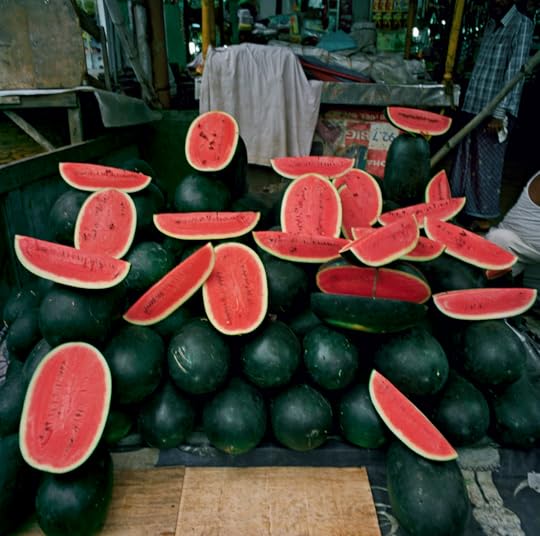

Display of watermelons, neighborhood of Rajabazar, north Kolkata, July 2014

View of the Lake Town neighborhood (in the north of the city) from the apartment of Shreyasi Chatterjee and her husband, Mrityunjoy Mitra, Kolkata, March 2011

By Imogen Prus

Paris-based photographer Patrick Faigenbaum pushes and stretches the limits of documentary photography in his work by entangling many parallels: reality and fiction, memory and possibility, object and transience. In 2013 Faigenbaum won the Henri Cartier-Bresson Award, enabling him to create a major photographic project in India, titled Kolkata/Calcutta. This body of work will be the subject of an upcoming exhibition at Aperture Gallery, curated by Jean-François Chevrier, marking the first joint project of the newly formed alliance between Aperture Foundation and the Hermès Foundation.

Kolkata/Calcutta was previously shown at the Fondation Henri-Cartier-Bresson in Paris. As well as playing host to Faigenbaum’s exhibition this fall, Aperture Gallery will become the American venue for the Henri Cartier-Bresson International Award, as the Hermès Foundation partnership bridges the photographic communities in the United States and France. Future plans include a set of exchanges, residencies, and publishing projects for contemporary working photographers, bridging the photographic communities in the United States and France.

Faigenbaum’s first trip to India was in 1995; on his departure he hoped to return, and this project records his first trip back in 2011. In Bengali, Calcutta has always been pronounced “kol-kata,” but over time this was tailored to the English tongue. The Anglicized name was replaced in 2001 when the Bengali pronunciation became endorsed. This decision highlights the pivotal shifts that have occurred in India over the past decade, where national identity has been renegotiated with rapid modernization and an economic boom. The dual name of Faigenbaum’s exhibition, Kolkata/Calcutta, refers to both India’s colonial past and also to the country’s detachment from it.

During his stay, Faigenbaum set out to capture the life of artist Shreyasi Chatterjee in her neighborhood and in the local countryside. Faigenbaum was inspired by Chatterjee’s work, which includes painting, collage, and embroidery. “As a whole, the images will constitute both a portrait of this artist in her family and professional settings and a free description of her larger urban environment,” he writes. “In this way, I intend to produce a complex image of one region of the Indian subcontinent which renders both its historical depth and its most vivid features.”

In linking up with the artist and her family, Faigenbaum was fortunate enough to gain access to sessions of folk musicians, jazz guitarists, and an elderly singer from the Bengali school of dhrupad song. Saurav Moni, a folk singer from North Kolkata, relaxes in his home, an instrument resting lightly on his knee.

The exhibition leads us through the city streets, but the compositions speak directly to the trajectory of Western aesthetics. In one street scene, a display of watermelons’ sharp geometric cuts reveals the pink flesh acutely counterpoised with deep green rind. The composition lends itself to the polished fruits of Western still life painting. We move on, through a set of images that mimic the grand portraits of colonial and military history: a seated woman draped in an armor of richly patterned fabric, hands loosely folded in her lap stares out past the photographer. A set of images taken from the window of a Grand Hotel surveying the street scene below is a direct nod to Pissarro’s evening scenes of rainy Paris. Faigenbaum, and, by proxy, the viewer, take on the role of the Baudelairean flâneur, simultaneously enchanted by, as well as at a remove from, the city. These images are the products of the experience of place, where dialogues are set up and cultures fuse.

Patrick Faigenbaum: Kolkata/Calcutta will be on view at Aperture Gallery September 17–November 7.

The post Patrick Faigenbaum: Kolkata/Calcutta at Aperture Gallery appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

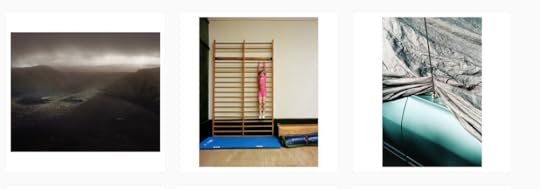

Unboxing the 2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Award Entries

The 2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards closed on Friday, September 11, with over 1,000 entries from over 60 countries. We’d like to thank everyone who sent in their books!

The shortlist will be announced on Friday, September 18 at 6:15 p.m. at the NY Art Book Fair. All thirty-five shortlisted books will be exhibited in Paris, New York, and Tokyo. The final winners from each category will be announced at Paris Photo on Friday, November 13 at 1 p.m. For more information, visit the PhotoBook Awards page.

The post Unboxing the 2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Award Entries appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 15, 2015

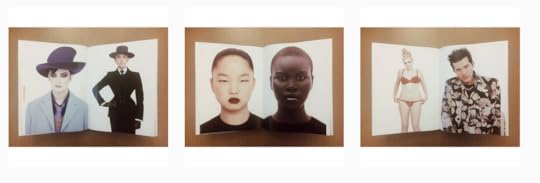

Magazine: An Interview with William Klein

When writer Aaron Schuman first arrived at William Klein’s apartment, five stories above Paris’s rue de Médicis, he was ushered into Klein’s living room by his assistant. Klein, eighty-seven, had been up until four thirty in the morning the night before and was having a rest. After an hour or so of thumbing through this Aladdin’s cave of trophies and treasures, Schuman heard Klein stirring in the rooms at the back of the apartment. “By the tone of his voice, I could tell that he had just woken up, and was reluctant to join me,” Schuman said. “His assistant pleaded, ‘But he’s come all the way from England!’”

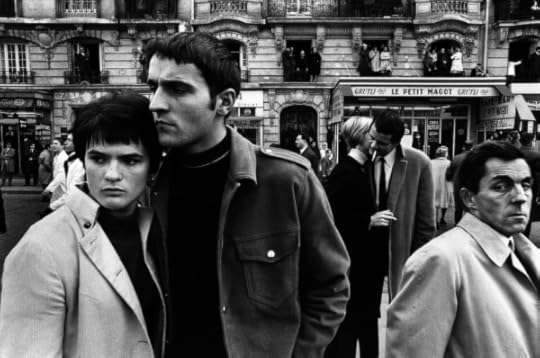

Finally, Klein entered the room, eyes wide and shining. This would be the first of two visits with Klein for this interview, which touches on the course of his remarkable career: his now-classic books on cities, including his hometown in Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (1956), Rome (1958–59), Tokyo (1964), Moscow (1964), and Paris (2003), all alive with Klein’s signature kineticism; his 1960s fashion work for Alexander Liberman, the celebrated art director at Vogue. This was the era in which Klein turned to moving images, having just made his first film, Broadway by Light, in 1958: he would become known for his fashion-world satire Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), starring model Dorothy McGowan, and Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1974), his cinema verité documentary on the fighter, among others. Recently, Klein has been revisiting some of his first experiments with still photography, abstractions from the early 1950s, some of which were exhibited at his London gallery last fall.

In this excerpted portion of their conversation, he speaks about his remarkable career, now in its seventh decade, about dreaming in black-and-white, and his celebrated fashion photography.

Atom Bomb Sky, New York, 1955

Aaron Schuman: Do you dream in black and white or color?

William Klein: Black and white, of course.

AS: What else do you dream about?

WK: I dream about a million things. It’s incredible. I had a dream recently, and I still don’t know whether it was a dream or not. It was about New York. Jean-Luc Godard was there, it was a Saturday, and there was an art opening. The people there were very friendly, and Godard was so, so nice, and also friendly. He was exhibiting his paintings, and people were saying, “Oh Jean-Luc, you have to come to my studio—I have some nice paintings to show you.” And he would say, “Of course!” which is so little like him. It was so precise, and everybody was the way that they should be. It was Godard being a nice New Yorker. He’s a prick, actually; I know him pretty well.

AS: So how did you go from making abstract black-and-white images in the darkroom to taking photographs on the streets of New York?

WK: Well, once I had the possibility of enlarging in a darkroom, I realized that the other photographs I’d been taking at the time were not as bad as all that. I was a primitive, and the photographs I was taking for myself were at the level of zero in terms of the evolution of photography. But once I had the opportunity to take the negatives and print them my way, I realized that I could use what I had learned—about graphic art, painting, and charcoal drawings, and so on—in my printing. So when I went back to New York, I had an idea of doing a book. I was twenty-four or twenty-five, something like that, and when you’re twenty-five you can do that sort of thing; if you decide to do it, you just do it. So I turned the bathroom in the hotel I was living in into a darkroom, and had access to a darkroom in my apartment. I washed the prints in the bathtub, and now these prints are considered “vintage prints”—they’re worth a lot of money.

Le Petit Magot, Armistice Day, Paris, 1968

AS: I was just looking through some of your old magazines, and saw that the first body of work you published in Vogue was selections from Black and Light.

WK: Yeah, I was participating in a show called Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris (1953), and Alexander Liberman—who was the art director of Vogue, and then became the art director for all of Conde Nast—left me a note asking me to come and see him. So I did, and he said, “How would you like to work for Vogue?” And I said, “Doing what?” and he said, “Well, we’ll see. You can be assistant art director or something.” We ended up deciding that I would do photographs, but I had no idea what kind of photographs I could do for Vogue. I looked at the fashion magazines, and I was really convinced that I couldn’t do anything like what the fashion photographers were doing; I mean, I thought their technique was beyond my reach. But when I looked more closely, I thought they weren’t so hot as all that, and the only photographers that impressed me were [Irving] Penn and [Richard] Avedon. The rest were just part of a system, and the more I looked at their photographs, the more I felt that there weren’t any really interesting ideas behind them.

Black Barn + White Lines, Island of Walcheren, 1952

AS: Before shooting any fashion photographs for the magazine, you also published a series called “Mondrian Real Life: Zeeland Farms” in Vogue in 1954.

WK: Yes, my wife inherited a house on the Dutch and Belgian frontier. One day we took our car and drove to the nearby island of Walcheren, and I saw these barns. They reminded me a little bit of the Dutch houses in Pennsylvania, and I learned that Mondrian had lived there during World War I. I thought that there must be some relationship between what he saw there and what he was doing later, so I photographed them. Then, when I met with Liberman again, he asked to see some of the stuff that I was doing, and when he saw those photographs he decided to publish a little portfolio of them in Vogue, which was unusual because it was a fashion magazine. But you know, fashion magazines at that time were the monthly dose of culture that women would get—theater, painting, exhibitions of all kinds—so those photographs fit in with the philosophy of Liberman.

AS: Did you enjoy working for such magazines at that time, when they had an important cultural influence as well as being about fashion?

WK: Why not? It was a way of making a living. The only things that were salable or publishable at the time were fashion photographs.

AS: Was that a concern of yours?

WK: It wasn’t a problem, just an observation I had to make. I thought that the other photographs that I was doing—the abstract photographs, the realistic photographs, the New York photographs, and so on—were more interesting. But nobody else was really interested in them.

Klein’s wife Janine with painted turning panels, Milan, 1952

AS: Were you frustrated by the fact that people were more interested in your fashion photography than in your art or street photography?

WK: I thought it was kind of bullshit photographing a dress, because I couldn’t care less. I was interested in photography and in photographic ideas. When I would do a session of fashion photographs my wife would ask, “What was the fashion like?” and I would say, “I have no idea.”

Read the complete interview in Aperture magazine.

The post Magazine: An Interview with William Klein appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 14, 2015

11 Photography Exhibitions to See This September

Markus Brunetti, Orvieto, Duomo di Santa Maria Assunta, 2006–2014, from the series FACADES. Archival Pigment Print © Markus Brunetti, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

FACADES at Yossi Milo Gallery (through October 17):

In 2005, after a twenty-year-long career in photography, the German artist Markus Brunetti went on a grand tour through Europe. Over a decade of traveling, he exhaustively recorded the facades of historic cathedrals, churches, and cloisters. For FACADES, Brunetti’s first U.S. exhibition, Yossi Milo Gallery presents fifteen of these works. Each image has been expertly assembled from hundreds, even thousands, of frames, that took weeks to years to complete. They are large-scale (five measure ten feet tall) and interpretive—modern day elements have been stripped away and reassembled according to Brunetti’s own designs. While large in scope, they also offer a full view of details otherwise overlooked in confidently performed architecture.

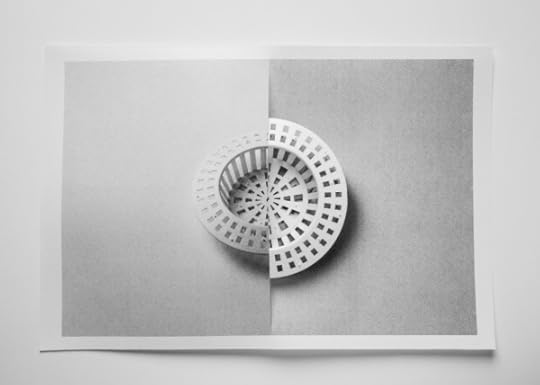

Delphine Burtin, Untitled, 2013, from the Encouble series. Archival pigment print © Delphine Burtin, Courtesy Benrubi Gallery, New York

Encouble at Benrubi Gallery (through October 24):

The Switzerland-based artist Delphine Burtin makes her U.S. debut at Benrubi Gallery. For Encouble, the gallery shows images that blur the line between photograph and sculpture. Working from cut-ups and re-photographed collages, the work is filled with optical illusions and subtle manipulations.

Left: Pierre Bonnard, Group de Pins, c.1938 Pencil on paper, mounted to board © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Right: Lee Friedlander, Nyack, 2000. Gelatin Silver Print © Lee Friedlander

Lee Friedlander & Pierre Bonnard: Photographs & Drawings at Pace/MacGill Gallery (through October 24):

Lee Friedlander had been photographing the social landscape of the United States for forty-two years before he decided to shift his camera to the natural landscape in 1990. With a newly acquired Hasselblad, Friedlander saw the natural world’s unyielding parade of line, light, and form as elegant patterns “deeply rooted in perceptual experience.” For this exhibition, Pace/MacGill couples Friedlander’s landscapes with the drawings of French Post-Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard. Like the legendary American photographer, Bonnard also recorded the natural world with seamless immediacy. Here their works are viewed together to illustrate how an artistic language can be shared across time and media.

Unknown Artist (Senegal). Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1910. Gelatin silver print from glass negative, 1975; 6 x 4 in. (16.5 x 11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Susan Mullin Vogel, 2015

In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (through January 3, 2016):

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York presents nearly eighty portraits taken by both professionals and amateurs taken between the 1870s and the 1970s in West Africa. “In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa” puts forward a broad variety of practices and aesthetics, juxtaposing photographs, postcards, and original negatives taken from photographers active in Senegal, Cameroon, and Mali, among others. The hundred-year survey explores the rich visual languages seen in the vast region, and much of the work is being shown for the first time alongside the work of renowned artists such as Seydou Keita, J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, and Samuel Fosso.

Deborah Turbeville, Rainy Day People, 1995 © Courtesy the Estate of Deborah Turbeville, New York and Foxy Production, New York

Deborah Turbeville: Rainy Day People at Foxy Production (through October 17):

The American photographer Deborah Turbeville widened the narrative boundaries of fashion photography before she passed away, in 2013. Incorporating portraiture, architecture, and landscape, Turbeville infused multiple stylistic flourishes with enigmatic psychological portraits. In 1995, L’Uomo Vogue commissioned Turbeville to create a series of photographs that portrayed fashion in a more mysterious, moody, and ethereal light. At once suspenseful and sensual, the photographs on view had a profound influence on fashion, editorial, and advertising.

Ralph Gibson, Untitled, 2015 © Ralph Gibson, Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Political Abstraction at Mary Boone Gallery (through October 31):

This new exhibition opening at Mary Boone Gallery at Fifth Avenue shares its name with a Lustrum Press monograph of color and black-and-white diptychs from the veteran photographer Ralph Gibson. The photographer, who began his career working alongside Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank, has developed a unique visual style that favors isolated, shadowy, and cropped images of everyday objects. The coinciding exhibition and publication gathers images that seek to complicate the act of looking, through sequencing shape, pattern, or shadow in a crudely bounded diptych.

Adam Fuss, LOGOS, 2015. Unique gelatin silver print photogram, 114 x 63 inches 289.6 x 160 centimeters © Adam Fuss

λόγος at Cheim & Read Gallery (through October 17):

The title of Cheim & Read’s exhibition of new cameraless photograms and linen-printed scans by the eBritish photographer Adam Fuss is a reference to a principle of connectedness understood by ancient Stoic philosophers. λόγος was said to be the uniting force between the rational and the spiritual, which inspired Fuss’s large-scale photograms, measuring between seven and nine feet tall, of falling water are captured with a flash of light on light-sensitive paper, and his scans of slithering snakes.

Wolfgang Tillmans, water melon still life, 2011. Color photograph © Wolfgang Tillmans Courtesy David Zwirner, New York, Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin, and Maureen Paley, London

PCR at David Zwirner Gallery (through October 24):

Wolfgang Tillmans’s first exhibition at David Zwirner is a comprehensive survey of the most important themes and processes in his career. Viewing an “exhibition [as] a medium to itself,” Tillmans installed more than seventy recent works, varying greatly in size, to allow for “a multitude of aesthetic as well as social relationships to crystallize.” Included are portraits of friends and strangers, landscapes and built environments, still lifes, and a sixteen-foot print suspended from the ceiling, among many other glimpses into the artist’s practice (look for revelatory portraits of himself and his studio).

Kazuo Kitai, Itakuramachi, Gunma, 1974, from the To the Villages series © Kazuo Kitai

Kazuo Kitai: Students, Workers, Villagers 1964-1978 at Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery (through October 24):

The Japanese documentarian photographer Kazuo Kitai, who began his career shooting student protests, will have over thirty photographs exhibited at Miyako Yoshinaga. Kazuo Kitai: Students, Workers, Villagers 1964–1978 presents modern and vintage silver-gelatin prints, selected by Kitai, from six different series made in his career from 1964 to 1978, including selections from his first photobook, Resistance, as well as Kobe Dockers, Barricade, Sanrizuka, Somehow Familiar Places, and To the Villages.

PaJaMa, Jensen Yow, Jack Fontan and Bill Harris, Fire Island, 1950

PaJaMa at Gitterman Gallery (through November 7):

Starting in the 1930s, the artists Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French collaborated together as PaJaMa to make photographs on the beaches around New York and New Jersey, including Fire Island and Nantucket. Originally considered “socially deviant,” the work was often erotic and took a range of expression from symbolic to surreal. Now highly revered, their vintage silver gelatin prints, on view at Gitterman Gallery, explore a psychological and symbolic tension between body and landscape.

Toshio Matsumo, For the Damaged Right Eye, 1968. Originally three 16mm color films; transferred to single-channel digital video, color, sound, 12:09 min. Courtesy the artist © Toshio Matsumoto

For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979 at Grey Art Gallery (through December 5)/ Japan Society (October 9 through January 10)

In selecting nearly 250 art objects made by twenty-nine photographers and other artists, For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979 features a wide range of postwar Japanese art practices. The selected art, on view concurrently at Grey Art Gallery and Japan Society, includes documentary photography, photographic installations, photobooks, and 16mm film projects made in the years between 1968–1979. Looking at how these works were made in a period “marked by political apathy, a weakened avant-garde, and a severe economic downturn,” the exhibition displays work that signaled a radical shift in Japanese photography and art.

The post 11 Photography Exhibitions to See This September appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Issue 15 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available

The new issue of the Aperture Photography App is now available to download on your iOS device. Here’s a look inside Issue 15:

● A look at the newly launched Aperture Archive which includes every issue of Aperture magazine dating back to 1952

● An excerpt of William Klein’s talk with Aaron Schuman from “The Interview Issue” of Aperture magazine

● A preview of the upcoming Patrick Faigenbaum Kolkata/Calcutta exhibition at Aperture Gallery

● A report on Hugh Mangum’s photographs of the American South

● More information about Aperture’s release of Bruno Ceschel’s Self Publish, Be Happy

Every issue of the Aperture Photography App is free– subscribers have new issues delivered to their device automatically. Select articles later appear here, on the Aperture blog. Click here to download the app today!

The post Issue 15 of the Aperture Photography App is Now Available appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 12, 2015

Mary Virginia Swanson: Securing Support for Your Long-Term Project

Jamey Stillings, Nevada Arch Segment, April 29, 2009; from the series The Bridge at Hoover Dam

Join Mary Virginia Swanson for a two-part workshop designed for photographers who would like to learn how to secure funding for a long-term personal project through drafting a successful proposal and budget, as well as learn how to build awareness for that project. The workshop will also explore various types of funding, as well as different approaches to expanding your audience.

On the first day, Swanson will present an extensive illustrated lecture, which provides an overview of public, private, and corporate support; the role of a fiscal agent; and how to navigate funding data. In addition, participants will learn about the importance of broadening awareness for their projects via public presentations, websites, and print and social-media marketing. At the end of the first session, participants will be assigned the task of producing a statement about their project, a budget, and a short list of potential funding sources.

During the second session, the group will discuss each participant’s project documents. The websites of each participant will be projected for discussion on enhancing project presence. Lunch will be served both days.

Mary Virginia Swanson is an author, educator, and consultant who helps artists find the strengths in their work, identify appreciative audiences, and present their work in an informed, professional manner. Her seminars and lectures on marketing opportunities aid photographers in moving their careers to the next level.

Swanson is the recipient of the 2013 Focus Lifetime Achievement Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography, and the 2014 Susan Carr Award for Education from the American Society of Media Photographers. The Society for Photographic Education named her the 2015 Honored Educator. Swanson coauthored Publish Your Photography Book (revised edition, 2014) with Darius Himes. Her latest publication, Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs, will be released in 2015.

The featured image, Nevada Arch Segment, April 29, 2009 is from Jamey Stillings’ exhibition and book of the same name, The Bridge at Hoover Dam, a project that is featured as a case study in Swanson’s upcoming publication, Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs.

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

Registration is now closed. Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Mary Virginia Swanson: Securing Support for Your Long-Term Project appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 11, 2015

Staff Picks: 6 Instagram Accounts to Follow

Members of the Aperture Foundation staff selected our favorite photography-related Instagram accounts of the moment, ranging from photographers to editors to public collections. Follow the Aperture Beat column on the Aperture Photograph App and online for regular staff picks about favorite readings, social media, and exhibitions.

You might recognize Brian Huskey from Veep, Childrens Hospital, or Comedy Central’s hilariously offensive new series, Another Period, but did you know he is just as comfortable behind the camera? A self-described “former photographer,” Huskey’s account mixes cleverly captioned selfies on set with his own color photographs and moody black-and-white images. My favorite is series of abandoned shopping carts, from a richly textured scene of two shopping carts doubled, to an image of one filled slightly with plastic bags, captioned “Mating,” to a lonely cart stuck in a hedge that is captioned “crashed.” –Nicole Maturo, Editorial Work Scholar

Laura Boushnak is a member of the Rawiya Collective, the first all-female Muslim/Middle Eastern photography collective. She has covered news for the Associated Press, Agence-Presse France, and the New York Times, mainly in the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Her Instagram, however, is full of quieter moments. These photographs run the gamut from incredibly simple, as in her photograph of a barely visible kite in the sky in Amman, Jordan, to the chaotic, as in an image of a man resting in an antique shop. Her photos manage to convey a stillness and simplicity to everyday life that I, personally, find incredibly calming. –Melissa McCabe, Circulation & Advertising Work Scholar

Aint-Bad is a bi-annual photography magazine that was founded in 2011 by 5 students from SCAD. The magazine’s manifesto is established around accessibility, so their Instagram feed is a great place to gain exposure to emerging photographers, as well as see perspectives from new editors. The editors often work directly to support photographers, many of whom are fresh out of school and have never been published before. –Becca Imrich, Education Work Scholar

This account features selections from The Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute appointment-only reference library, a collection of over 25,000 hard-to-find fashion and photography books from all over the world from as early as the 16th century. –Elena Tarchi, Publicity and Events Associate

Kalen Holloman is not only cool and funny but also inspiring. The New York–based artist creates collages on Instagram that riff on art and fashion, often in the form of pieced-together, faux advertisements for luxury brands. –Lauren Bouton, Sales and Operations Assosciate

Ian C. Bates is a Seattle based photographer with an Instagram feed largely consisting of small town America, old Chevy Novas and complete isolation. I’m a big fan of the color palates and diverse subject matter he brings to my endless scrolling. –Max Mikulecky, Digital Marketing Assistant

The post Staff Picks: 6 Instagram Accounts to Follow appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers