Aperture's Blog, page 144

February 13, 2016

Photography at the Altar: A Conversation about Diversity in Athens

A Greek photographer’s account of migrant communities in Athens reveals a new vision of multicultural Europe.

Tassos Vrettos, Hindu Sewa Sangh Mandir, Dilessi, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

Amid the anxious media coverage of the migrant crisis in Europe, the Greek photographer Tassos Vrettos pursued an alternative vision. In 2012, he began an immersive account of faith-based communities in Athens, embedding himself in the spaces where followers of Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, and various other spiritual denominations congregate to worship. He collaborated with subjects originally from Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Senegal, determined not to represent the trials of arrival and departure associated with migration, but instead the intensely collective, sometimes improvised sites of religious experience. The resulting compendium of images, presented at the Benaki Museum, in Athens, in the exhibition Wor(th)ship. Tassos Vrettos, and collected in an expansive catalogue, is remarkable for its sustained balance between closeness and objectivity. Vrettos, known for his work in fashion and advertising, is neither a participant nor a voyeur. As Wor(th)ship spans a diverse spiritual network, Vrettos’s photographs invite viewers to consider Athens—considered the birthplace of Western civilization—as a cosmopolitan city of the future. I spoke with Vrettos and the curator Nadja Argyropoulou shortly after the closing of Wor(th)ship, on January 30, 2016, an event of testimony and song by many of the migrants and refugees pictured throughout Vrettos’s project. —Brendan Wattenberg

Tassos Vrettos, Bethel Divine Healing Ministry – House of God (Ghanese), Aiolou Street, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

Brendan Wattenberg: How did this project begin? Why were you compelled to make a portrait of religious communities in contemporary Athens?

Tassos Vrettos: “Compelled” is a very good word, I think. I began this fieldwork, coincidentally, during Easter of 2012. I had read in a newspaper that a particularly beautiful Resurrection service was held at the Ethiopian church in Athens and I decided to attend. On Holy Saturday, following a rather eventful search, I found the place and walked into this wonderfully incongruous space. The paradoxical context created by the transitory lives of immigrants and refugees in Athens—both people who have been here for years and those who come and go—involves ecstasy, beauty, and accessibility in the same measure as their opposites. I realized I wanted to think about these spaces more widely, and most importantly, to show what matters to the people who inhabit them. I looked for a way in, and these communities were generous enough to welcome me—in garages and DIY field constructions, in derelict apartments and basements, in public fields, rented hotels, discos closed by crisis, courtyards, gardens, and pop-up temples. I have always worked with people in states of displacement, in borderline, precarious, or ambivalent situations. So, to conjure the familiar from within the foreign is what photography is for me.

Tassos Vrettos, Cultural Center – Sri Lanka, Neo Psychiko, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

BW: In the catalogue, you write about maintaining a respectful distance to your subjects, while also immersing yourself, so as to produce a genuine and authentic representation. How did you gain access to these private sites of worship? Have you made long-term connections to your subjects?

TV: Wor(th)ship has been, and still is, a commitment-in-progress. This project is about storytelling, rather than methodical or exhaustive cataloguing. Yet it’s storytelling in a state of urgency and crisis. My explanations to the communities I approached were straightforward and genuine. I had no grand goal or complicated aesthetic-conceptual scenarios. We had ongoing conversations about how people navigate their lives. We had to trust each other. I showed them my photos as I was making them. I explained that I would try to make a book and an exhibition, and in maybe only two, out of more than sixty places, I received permission to photograph but not to use my material publicly.

Tassos Vrettos, Dahiraa Mouhabina Fillahi – Athens (Senegalese), Koliatsou Square, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

My camera was a small and cheap one; I disappeared so that the worshipping people appeared; I became part of each church’s collective body, and by doing that I knew instinctively which line I should not cross, which photograph was given and which would have been stolen, forced. Some of the most interesting relationships, even friendships were forged in the process. I am invited to private ceremonies now, birthdays and weddings and major meetings of most of the communities.

Tassos Vrettos, Singh Shaba Gurudwara, Marathon, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

BW: What was one of your most memorable encounters during the course of this project?

TV: I can hardly separate one from so many. I was in complete awe during the graceful Ethiopian and Eritrean ceremonies and exhilarated through the Nigerian Evangelical worshipping, with all its pure joy and phantasmagoria. I was deeply shaken while photographing a night during Muharram at the Shiite Afghani mosque, when I found myself in a forest of people crying, singing, undressing, and hitting their bodies with their fists or chains (the Matham). It was a collective burst of faith, sorrow and lament carried through centuries to their contemporary lives and experiences. Smells and sounds have also been very important since the beginning. I asked the musician Mihalis Kalkanis to accompany me and record them. We now have a material that extends the very fabric of the photographic experience.

Tassos Vrettos, Father Solomon Mesein Eritrean Orthodox Church Athens, Pangrati, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

BW: Wor(th)ship appears similar to a work of ethnography, not unlike the long-term studies social scientists undertake to describe a particular community. How do your photographs, which in some cases concern ancient practices, also contribute to the photojournalism of the moment—and to our understanding of the politics of multicultural Europe?

TV: I did not chose my subject as a photojournalist and I do not possess the tools of an ethnographer. I cannot claim to be able to help understand, let alone change European politics. My practice is of a “threshold” nature. I want to know and I need to share. I yield and thus I see. I am ashamed by exoticism and folklore, so I have been very concerned about presenting this work during the recent media frenzy around the immigrant and refugee issues. I am content now because this material, as I’ve said, is about storytelling that goes beyond “happenings” and “episodes” and therefore I think it has escaped many such traps of sensationalism.

Tassos Vrettos, Fatima – Zahra Mosque, Marathon, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

The reaction of Greek people, the residents of Athens who visited the exhibition and purchased the book, was a big reward. They were silent and bewildered; some cried, and then talked for a long time outside the exhibition space; some shared unaccounted for stories about their past or their own experience with immigrants. Some returned to the exhibition several times. I think people considered this project a revelation, one that is relevant to their lives and future, perhaps even in a positive way. Strangely enough, as the project threw light onto foreign societies, it also illuminated another aspect of Greek life.

Tassos Vrettos, Egyptian Orthodox Christian Copts – Church of Virgin Mary and Mark the Evangelist, Menidi, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

BW: Nadja, why were you drawn to this project? How did you decide to organize the exhibition and catalogue, as you describe, in the form of a “narrative rhythm”?

Nadja Argyropoulou: The unknown material and raw process of this project inspired my interest. In my work as a curator, I have thought frequently about shifting identities and how Greece has recently become a “stage” for such transformations. I followed Tassos’s project from the start. I visited some of the spaces of worship with him, I participated in seeking them out, I met the people, I listened and then learned the dialogue on faith, aesthetics, politics. To speak “with” others—instead of “for” others—became a guiding principle in curating both the exhibition and editing the catalogue. There is rhythm in this exchange, a kind of tidal flow, as multiple visual narrations, mental images, and sensual content speak above the tyranny of language towards deep engagement and actual change.

Tassos Vrettos, Singh Shaba Gurudwara, Marathon, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

Together with Tassos, co-curator Yorgos Tzirtzilakis, and the other collaborators, we decided to bring this material into one of the great and most open Greek museums, the Benaki. We prompted the organizing institution, as well as our major sponsoring partner, the Onassis Foundation, to think out of the box while avoiding the “spectacle” of representing refugees. We treated the communities involved as equals without the patronizing political correctness and over-protectiveness of current discourse. The exhibition is one of the most visited at the Benaki—and foreign communities, immigrants, and refugee groups attended in unprecedented numbers and diversity.

Tassos Vrettos, Safeena Puntjan Pak. (Pakistani Muslims), Peristeri, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

BW: What do you hope for the future of this project?

NA: To continue being true to itself, the people in it, photographed or not. To travel the exhibition and to circulate the catalogue widely.

TV: For me, the most important part of the presentation of this project was January 30th, the closing day, when members of the communities—Senegalese, Nigerians, Syrians, Pakistani, Afghan, Indonesian, Christians, Muslims, Hindu, Buddhists, and many more—accepted my invitation to speak in public, at the Benaki museum, about their experience of this project, their view on the show and the book, and about their lives in Athens and their current status as citizens. The experience was overwhelming in its immediacy and uncharted qualities.

Tassos Vrettos, Angladeshis, New Year’s Eve, Koumoundourou Square, 2012–15 © Tassos Vrettos

Wor(th)ship. Tassos Vrettos was presented from November 20, 2015 to January 31, 2016 at the Benaki Museum in Athens.

The post Photography at the Altar: A Conversation about Diversity in Athens appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 11, 2016

An Interview with Rosalind Fox Solomon

Rosalind Fox Solomon’s photographic career has been defined by an itch for travel and a desire to use the camera as a means of self-discovery, or, as she puts it, as a way of “talking to myself.” A student of photographer Lisette Model, who was known for her confrontational images of New York City’s street life, Solomon, over many decades, has photographed extensively in South and Central America, India, and Poland—as well as in places closer to home, like New York and the American South. Her work, however, is often metaphorical, transcending mere descriptions of place. For Aperture’s recent Interview Issue, novelist and critic Francine Prose met with Solomon last April at her Manhattan home, where the two spoke about the trajectory of Solomon’s career, her leitmotifs of ritual, religion, gender, and travel, and her relationship with Model.

Interview by Francine Prose

After 9/11, MacDowell Colony, New Hampshire, 2002, from the series Self-portraits

FP: How did you start working with Lisette Model?

RFS: Modernage lab led me to Lisette Model. Though I worked in the darkroom, I didn’t know what I was doing. So when I got to New York, I took my film to the Modernage photo-lab and had prints made. I went to their Christmas party in 1971 or ’72, and I met a photography agent, Henrietta Brackman. She made an appointment with me, saying, “Bring everything you’ve ever done.” I said, “I can’t. There’s too much.” She said, “You have to bring everything you’ve ever done.” I brought two huge suitcases full of things, and after she looked at my pictures, she said, “You have talent but you need help. You should study with Lisette Model. She was Diane Arbus’s teacher.” Diane Arbus and Ansel Adams were the only photographers I had heard of at that time. I got in touch with Lisette and she said, “The next time you come, meet me and bring everything you’ve ever done.”

Untitled, Oregon, 1985, from the series, Ritual

FP: You already had it packed in the suitcases.

RFS: The next time I got to New York, I brought everything I’d ever done. Lisette came to my hotel room, and she looked at my pictures from six o’clock until midnight. Finally, she was too tired to go on, but she told me that I could study with her. Whenever my husband came to New York on business, I came with him and brought my pictures to show to Lisette.

Engaged, near Jenin, 2011, from the series THEM

FP: And what did “studying” mean?

RFS: Before we began, Lisette spent a half hour talking about herself and her career. She was blunt and though she had much success early on, getting her work out had become more difficult. She talked about the work of other photographers—the ones she considered authentic and the ones whose work she did not like because it was commercial or derivative. I got impatient as I listened to her, but eventually, I realized that all of what she said was instructive. Finally, she would look at what I had done and critique the prints. Then she looked at my contact sheets to see what I had not chosen. She said to always go for the extreme. By this I think she meant, Be true to yourself as an artist. Don’t censor yourself. Don’t do your work to please others. She advised, Always make one picture you can give to a subject; otherwise be free in what you do. One of the most important things I learned from her was to take risks.

Untitled, Tokyo, 1985, from the series Ritual

FP: Did things change radically when you started working with her?

RFS: I was in my early forties when I met her. Lisette was a strong influence. She was my mother in art. My birth mother was overly concerned about convention and propriety. Lisette was the opposite. She convinced me that the most important thing in my life was my work. She would say, “You need a close-up lens.” And I’d say, “But that costs so much money.” She’d say, “Can’t you afford it, dahling?” She always pushed me to upgrade my darkroom, to get any kind of camera equipment that I needed, to keep moving ahead. And since my husband always felt it was important for me to buy modish clothes—he really cared about that—I knew that I could certainly afford to buy some camera equipment. I still remember a camera shop salesman who tried to convince me that I did not need to upgrade to a more professional enlarger. Lisette encouraged me to be oblivious to what people thought about me or my work.

White House Gates, Washington D.C. , 1977, from the series Outside the White House

FP: You start off taking pictures of dolls. They don’t talk. But when you begin to take pictures of the living, especially during festivals and rituals, what do you say to your subjects?

RFS: I don’t say very much.

FP: You just started shooting?

RFS: In the spring of 1978, I planned a week’s trip to Guatemala with my husband. It was a vacation for him, and an opportunity for me to speak Spanish and take pictures in an environment far removed from life in Washington. After the initial trip, I went back a number of times. I traveled alone with a driver guide. This enabled me to get deeper into my work.

Even though I speak Spanish, I didn’t say very much. I soon learned that if you engage very

much, you lose a certain tension in the picture. Rather than make people feel at ease, I find that

some tension between me and the person I am photographing yields something more complex. I always traveled with a local driver who spoke to people on my behalf as I began shooting. I carried a Polaroid always and took pictures to give to people after I finished making my pictures. I also brought back proof prints on subsequent trips and gave them to people I had photographed.

I photographed shamans in Guatemala. There was a personal connection. My husband had

a progressive congenital disease. Knowing that his mother, aunts, and an uncle had died of the disease, from the time that he found out during the first year of our marriage, I thought about this. I was interested in how other people dealt with sadness. In Guatemala, they coped with the help of shamans, ritual, religion. I encountered people who were in much more difficult circumstances than I could ever imagine. Once I was in a séance in Peru with two shamans, a man and a woman who were reputedly lovers. We were sitting around a little fire in a little hut for a coca séance. They incanted and sang, “Smoke your cigarette and cha-cha your coca.” I told them that my husband was sick. I mean, I didn’t really believe in this. I didn’t believe in it but I just—

Untitled, Guatemala, 1979, from the series Landscapes

FP: Everybody sort of believes in it.

RFS: I thought maybe it would be helpful. So I told them about my husband and they took it very, very seriously. They told me that I had to get a guinea pig and rub the guinea pig on the body part that was injured or sick, and presumably the illness would pass into the guinea pig. So they told me to get a guinea pig and rub it over his body.

FP: How did that play out when you got home?

RFS: Well—

Transformation, Bahia, Brazil, 1980, from the series Ritual

FP: So when you found these drivers, you would say, “Do you know any shamans?”

RFS: Yes. I photographed a lot of shamans in Guatemala. I also photographed landscapes,

farmers, and Easter processions. In Peru, my driver was a twenty-two-year-old Chilean named Pablo. His parents had been supporters of Allende and they had gone to live in Germany after Allende was assassinated. Pablo went to Peru and married a Peruvian. Our first trip was idyllic. I had a lot of fun with him. The road up into the Andes was beautiful and untouched. We encountered women carrying spindles and weavers on the side of the road. In reality, people were living hard lives in a subsistence economy, but what was going on then was from another time. On my next trip with Pablo, I planned to photograph carnival celebrations. He sang revolutionary songs and stopped to use binoculars to look up into caves in the mountains. I began to think that he must be involved with the Shining Path [a Maoist guerrilla group]. We got rooms for the night in a pension in a small village. I got up in the middle of the night and went out into the van. I was scared.

At dawn, I went out in the street and talked to a woman, saying, “I’m with a driver and I don’t

have confidence in him.” I was afraid to say anything more. She said, “Go to see the bishop.” I told the bishop that I had come to photograph carnival, but I had to leave my guide. He said, “Stay and take your pictures. We will help you.” He introduced me to Madre Rosa Cedro. For a few weeks, I lived in a house belonging to the church that was near the convent and had meals with the nuns.

A Heart Tattoo, Tel Aviv, 2011, from the series THEM

FP: Is there a photo of her? Standing by a horse?

RFS: Yes, I went with her on an overnight horseback trip to a remote area. I went back a number of times to that village.

To read the complete interview, click here to buy issue #220. Subscribe and never miss an issue.

The post An Interview with Rosalind Fox Solomon appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Thank You, and Come Again: Robert Frank in a New York Minute

The legendary photographer’s retrospective is here today, gone tomorrow.

By Nicole Maturo

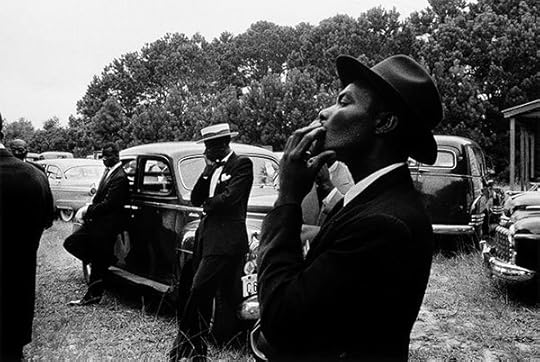

Robert Frank, Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina, from The Americans, 1959 © Robert Frank

“Don’t you think your gallerist will hate you?” Gerhard Steidl asked his longtime friend and collaborator, the acclaimed photographer Robert Frank, at the recent opening of Robert Frank Books and Films, 1947–2016, currently on view at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. All of Frank’s prints in this show will be destroyed at the end, on February 11, 2016, leaving nothing to be sold afterward. Frank didn’t seem to mind. The exhibition, created by Frank and Steidl Verlag in Germany specifically for academies and universities, presents the entirety of Frank’s photographic and film career on disposable newsprint—an ingenious concept designed to avoid the prohibitively expensive insurance fees that would be attached to edition prints by the ninety-one year old photographer, which command upwards of $600,000 apiece. The freedom afforded by displaying unsigned prints, crinkled from a buzz of students leaning against the prints between classes, allows viewers to finally see the breadth of Frank’s incredible career—rather than a reduced selection of his greatest hits.

Installation view of Robert Frank, Books and Films, 1947–2016, New York University, January 2016

Selections of photographs from each of Frank’s publications are printed on long horizontal sheets of newsprint, while a mobile of his photobooks swings gently from the ceiling. Some of these works are well known; others are obscure collectibles like Zero Mostel Reads a Book (Steidl, 2008). Frank’s legacy goes beyond the material; his work lives on in the minds of photographers and filmmakers everywhere. In producing an exhibition that ostensibly leaves nothing behind for resale value, Frank and Steidl have even extended the highly economical, pop-up concept to the catalogue. Together with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, Steidl produced a special broadsheet for the exhibition in the same format as the German daily newspaper, down to the very last detail including the opening day’s weather and date: January 28, “The forecast: splendid.”

Robert Frank, Books and Films, 1947-2016, Steidl, 2015–16

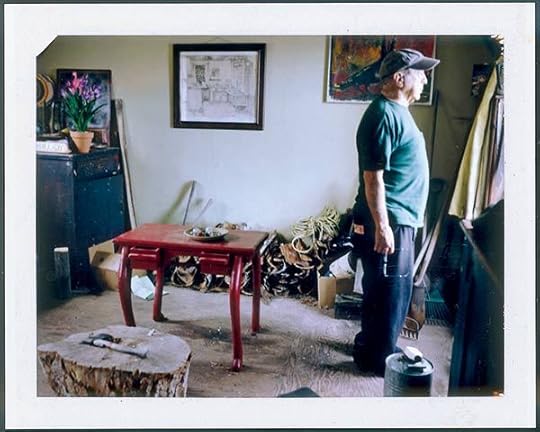

The exhibition affords a rare opportunity to trace the trajectory of Frank’s early empathetic black-and-white documentary images, to his later interweaving of color and black-and-white domestic vignettes. Wall-length contact sheets reveal Frank’s legendary American road trip, complete with grease pencil marks across blown-out frames, question marks, and boxes around the perfect shot. Those now iconic images, filling the pages of the The Americans (Grove Press, 1959), were often a single frame, or one of two at most. In his later Polaroid works, we see his rushed modus operandi turned on himself, as in his two Polaroid self portraits dated September 2001. Mouth agape, glare on his glasses, no presumption—this is the unsentimental Frank after all these years of acclaim untouched by the lure of fame and fortune.

Robert Frank, 2009 Mabou, from the book Household Inventory Record, 2013 © Robert Frank

To the question about whether Steidl’s exhibition would displease his gallery, Frank answered, “I don’t think so. I’m happy to see the photographs live again and to be appreciated.” As if Frank hasn’t done enough for posterity, his latest enterprise is a reminder that all art is ephemeral. “Sometimes the photographs can live longer because it becomes an image that will live longer in people’s minds,” he said, by way of wrapping up his remarks at the opening. “And that probably is the best thing about my photography. So I’m here to say thank you, and come again.”

Nicole Maturo is the Aperture Magazine Work Scholar.

After closing at New York University, Robert Frank: Books and Films, 1947–2016 will be presented at Bergamot Station, Los Angeles, beginning March 31, 2016.

The post Thank You, and Come Again: Robert Frank in a New York Minute appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 10, 2016

Torbjørn Rødland: Inducing Wonder

Exploring the symbolism of cultural mythologies and human nature, Torbjørn Rødland is a modern-day surrealist. Ahead of his artist talk at the Aperture Gallery and Bookstore on February 16, 2016, here’s a preview of the Norwegian photographer’s recent work.

By Brian Sholis

Torbjørn Rødland, Last Blue Yodel, 2010–14

“Who poured the paint?” I asked Torbjørn Rødland recently over Skype, referring to Pump (2008–10). “I did,” he replied, adding, “I cannot delegate important tasks like these.” The Los Angeles–based Norwegian artist’s answer, an assertion of control over a situation governed by chance, hints at the tension that characterizes many of his photographs. It is similar to the tension of live performance, in which a structure or script comes to life through people who bring to it their interpretive prejudices and their frailties—and who can’t always control environmental factors. At another moment in our conversation, Rødland elaborates, “I’ve learned to trust that what I’m handed is better than what I could possibly plan for. This is, of course, after having planned certain things, or initiated a situation, or set a stage for invited performers.”

Torbjørn Rødland, Pump, 2008–10

Rødland’s stage sets are often nondescript—a domestic interior, a clearing in the forest, a blank studio wall—and thus allow viewers to concentrate on the action occurring within them. A young woman in a leotard and saddle shoes lies prone on a kitchen countertop, contorting her body as she holds her feet near her ears. Another wears high-top sneakers on her hands, which rest on the ground in a pose that gives her the appearance of an animal standing upright, delicately and awkwardly, for the first time. A colorful heap of marker strokes, made by an unknown hand, cover a preteen boy whose arm is in a cast. These events are so unusual they seem to occur solely for the camera’s gaze; their absurd specificity removes them from the flow of everyday life. Put another way, his photographs are not “decisive moments” but dispatches from another realm, one that exists in parallel to our world. That sense of separateness is heightened by how absorbed Rødland’s subjects are in their inscrutable rituals. They rarely gaze directly into the lens, and therefore seem unwilling or unable to acknowledge us.

Torbjørn Rødland, Golden Lager, 2007

The artist’s midcareer survey, presented earlier this year at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Oslo, outlined significant changes in his art over the last twenty years. He no longer appears in his own pictures, as he did during the mid-1990s. He collaborates with friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. Now he often photographs two or more people, rather than individuals. He no longer works in series. These developments, though seemingly small, tangibly affected his photographic process. “It made me more productive,” he says. By choosing not to place his pictures into predetermined categories, Rødland is free to create whatever “tragically vague inner image” comes to his mind. At any given moment he has dozens of completed photographs waiting for an appropriate context in which to be published or exhibited. (A date like 2011–15 indicates the gap between when the negative was exposed and when the first print was made.) When a batch of Rødland’s photographs is gathered together, then, the connections among them are suggestive, aleatory, wonder inducing.

Torbjørn Rødland, Goldene Tränen, 2002. All images courtesy the artist and STANDARD (OSLO), Oslo; Air de Paris, Paris; Algus Greenspan, New York; and Nils Stærk, Copenhagen

In our conversation, Rødland used the word weak in several contexts: “There’s no need to do a weaker version of something one has already made.” The language suggests art making as athleticism, and successful pictures as mastery over countervailing forces. Perhaps the greatest forces to overcome are social and pictorial conventions: genre clichés and good manners. When I asked if the camera gives him license to do—and reveal—things that would otherwise seem unacceptably strange, his response neatly summarized the disquieting appeal of his photographs. “Having to convince strangers to give physical shape to ‘unacceptable’ situations is harder than just moving a pencil. But there’s also an enormous reward.”

Brian Sholis is Associate Curator of Photography at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

This article was originally published in Aperture issue 221, Winter 2015, available for purchase or in the Aperture Digital Archive.

The post Torbjørn Rødland: Inducing Wonder appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 8, 2016

The Call Begins: The 2016 Summer Open

The call officially begins for the 2016 Summer Open, Aperture’s third annual open-submission exhibition! The theme for this year’s competition, inspired by Photography is Magic, will be curated by Charlotte Cotton. Entries will be accepted through April 6, 2016 at 12:00 noon, eastern standard time. All photographers are eligible to apply, but entrants must be a current Aperture Foundation Member.

To learn more, click here.

The post The Call Begins: The 2016 Summer Open appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 5, 2016

Jürgen Klauke: Transformer

With provocative self-portraits from the 1970s, a pioneer of Body Art makes his New York debut.

By William J. Simmons

Jürgen Klauke, Transformer, 1973. Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

Born of the experimental intermingling of 1970s activist identity politics and performance art, Jürgen Klauke appears to be the gleefully strange lovechild of Judy Chicago and Mary Kelly. Appropriately, visitors to Transformer: Photoworks from the 1970s, Klauke’s first solo exhibition in New York, should consider the ethics of photographic performance, and of the dichotomy between body and selfhood. At Koenig & Clinton, he presents photographic series completed between 1970 and 1976, mostly self-portraits, which create an intimate but masked explication of body politics. Though Klauke emerged from a desolate youth in postwar Germany, these images do not remain hinged to a particular moment, but instead further contemporary conversations about changing visions of self-definition—from the postmodern turn, to third-wave feminism, to transgender critiques currently broaching the shores of popular magazines and boutique television.

Jürgen Klauke, Masculin/Feminin, 1974 (detail). Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

Consider Klauke’s thirteen-part series Masculin/Feminin (Masculine/Feminine) (1974), an exemplar of his career-long interest in Surrealism and performance art beginning in the 1960s. He starts with five self-portraits with his genitals obscured, though his masculinity is certainly present even as he fondles a phallic snake—or yoke. (I can’t help but recall Alexander McQueen’s often faux-primitive designs, such as Widows of Culloden, of Autumn/Winter 2006–7.) Klauke is then joined by a female figure, whose breasts are the only signals of her gender. The remaining photographs of the twosome posing and variously entwined with a black veil are reminiscent of a Jack Smith-inspired photo booth at the mall—suburban camp made delightfully glamorous with self-aware gaudiness, akin, perhaps, to the feigned trans-manliness of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle.

Jürgen Klauke, Verschleierung (Veiling), 1973. Installation photo: Jeffrey Sturges. Courtesy Koenig & Clinton, New York

In its resemblance to the focusing cloth for an 8-x-10 view camera, the veil unites the variously gendered agents in Klauke’s photographs in a shroud of beautiful obsolescence. In this way, Klauke signals the materiality of the images, which is compounded by a blur that results from his internegative process, a method of film duplication that preserves the original negative and creates a slightly unfocused shimmer. These photographs, to be sure, are not meant to be fully digestible, even in their self-aware and unabashed flamboyance. A formal process blocks the complete absorption of the image, just as Klauke does with gender, as if the androgyny molded by Klauke has become dispersed throughout the photograph itself.

Installation view of Jürgen Klauke: Transformer: Photoworks from the 1970s. Photo: Jeffrey Sturges. Courtesy Koenig & Clinton, New York

Even so, Klauke’s photographs ask if a “queered” formalist approach is sufficient. Klauke presents, as a cisgender man, performances that must be connected to real bodies and often endangered, queer lives. Even with female artists working in this vein, such as Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing, gender play on camera has serious, real-world implications that require constant investigation. Transformer (1973) and Illusion (1972), which seem to be precursors to the affected, culture industry-driven androgyny made fashionable by David Bowie and, presently, by Lady Gaga, suggest penile breasts and vaginal allusions that radically eliminate the virile male artist persona so present during their making. While such mainstream appropriations lack introspection, Klauke’s medium-specificity and self-referentiality willingly expose the critiques—photographic and sexual—that could be levied against his gender performances. Though the ethics of his bodily and photographic manipulations are of a distinctly different time, to see his work as retrograde would be like disregarding Womanhouse, one of the originators of feminist performance, for its Second Wave underpinnings. It’s impossible to understand our present state without understanding the transgressive acts of yesteryear.

William J. Simmons is an adjunct lecturer in art history at the City College of New York, and a PhD student in art history and women’s studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

Jürgen Klauke, Transformer: Photoworks from the 1970s is on view at Koenig & Clinton, New York, through February 27, 2016.

The post Jürgen Klauke: Transformer appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 4, 2016

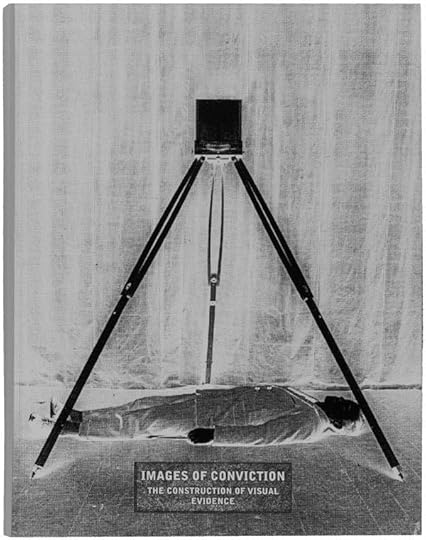

Images of Conviction: A Conversation with Diane Dufour and Xavier Barral

Through eleven case studies from Alphonse Bertillon’s Parisian crime scenes to aerial views of drone strikes in Afghanistan, Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence probes one of the central impulses in photography: portraying the truth. Aperture recently spoke with Diane Dufour, director of Le BAL, where the exhibition Images of Conviction was presented in Paris last year, and Xavier Barral, publisher of the catalogue, about their collaboration and the enduring fascination with forensic photography. —The Editors

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence (Paris: Éditions Xavier Barral, 2015)

Aperture: Images of Conviction, winner of the Photography Catalogue of the Year at the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, examines the power of photography in representing crime, war, and acts of violence. What was the origin of this exhibition? At an institution more commonly known for presenting contemporary photography, how has the exhibition enriched your program at Le BAL?

Diane Dufour: Our mission at Le BAL is to think about the role of images in society as well as in our understanding of history. Too often the status of the image oscillates between those who believe the immediate reality represented by the image and those who consistently challenge the validity of the image as too fragmented, too subjective, too manipulated. In Images of Conviction, we wanted to examine how experts or historians investigating crimes of violence must build a case in which the image “becomes” a form of evidence. Photography can document a scene of action and return a set of visible results—but what can we really learn from what we see in a picture?

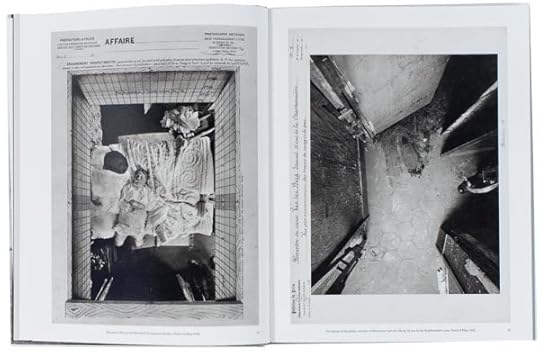

Spreads from Images of Conviction, including murder scene images by Alphonse Bertillon, Préfecture de Police de Paris, 1908 and 1916

Aperture: The catalogue contains case studies that took place in such varied locations as France and Kurdistan and span more than a century. How did you select these studies? Were there others you would have liked to explore if you had more space in the exhibition and catalogue?

Dufour: Over the course of three years, we identified eleven historical and contemporary cases. We persuaded museums, foundations, collectors, and photographers to offer us images, and we then invited an expert to decipher each case for the public at Le BAL.

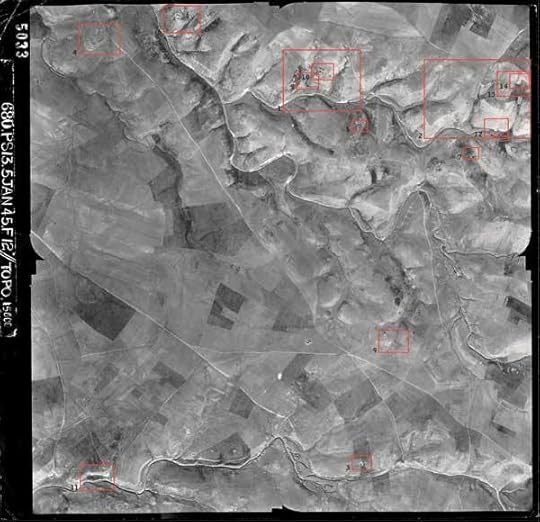

In the eleven cases, the device of presentation for the book and exhibition—mounting, assembly, expansion, accumulation—reveals at the same time the gesture of the criminal and the investigation of the expert. Criminologist Alphonse Bertillon built the metric space of the scene; forensic scientist Richard Helmer superimposed images of the skull and face of Josef Mengele; the book of the destruction of Gaza is an inventory of the buildings destroyed after the Israeli attacks there in 2009. Sometimes it’s the very material of the image that is probed: Are the silhouettes of the victims of a drone attack in Miranshah, North Waziristan, actually embedded in the pixels of the video image? Is the trace of a Bedouin cemetery readable in the silver grain of a photograph of Palestinian land taken by the Royal Air Force in 1945?

I wish I had been able to include the amateur film footage of the Rodney King case in 1991. During the trial, the prosecutors played the video at normal running speed (in “real time”), whereas the lawyers defending the police showed slow-motion replays. The same images were summoned by the prosecution and defense, brandished each time as irrefutable evidence of contradictory facts!

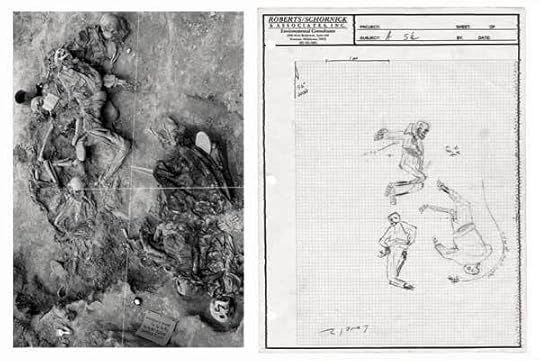

Left: Grave A-South, Koreme, North of Iraq, June 1992. Photo: Susan Meiselas; Right: Drawing with scale and orientation of Grave A-South, Level 2. Drawing by James Briscoe, forensic team archaeologist Grave A-South, Koreme, North of Iraq, June 1992. Photo: Susan Meiselas for Middle East Watch and Physicians for Human Rights mission, May–June 1992. © James Briscoe for Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights

Aperture: Xavier, as a publisher, why were you drawn to these images and studies?

Xavier Barral: This project interested me immediately because the photographs posed a question about the meaning of images in time and space. To confront the meaning of images is a daily exercise for publishers, yet the cases studies in Images of Conviction cover all spectrums of the image at different times. The same questions come up about the role of the image in constructing our thoughts. Whatever the space that separates us from the subject, the photograph provides distance, correlating elements, from micro to macro, in the case of police images, the X-rays of the Shroud of Turin, aerial photographs, and so on.

Images produced using photographs of Mengele and images of his skull in Richard Helmer’s face/skull superimposition demonstration, Medico-Legal Institute labs, São Paulo, Brazil, June 1985. © Richard Helmer, Courtesy Maja Helmer, 1985

Aperture: Images of Conviction is sober, minimal, fact based, and privileges informative captions and scholarly essays. When you first began working with Diane on the project, how did you intend to translate the idea of the exhibition into the book?

Barral: Often the final edition of the book develops upstream—the book becomes the study of the raw elements of the exhibition. With Diane, we realized very quickly that we had to create a graphic design that would allow the images to be truly legible. Hence the choice of a graphic form that’s factual, that’s as sober as possible. Coline Aguettaz, graphic designer for Éditions Xavier Barral, knew remarkably well how to translate this idea.

The N4005-02 building after destruction, from the archive A Verification of Building–Destruction Resulting from Attacks by the Israeli Occupation, 2009 © Palestinian National Authority Ministry of Public Works and Housing

Aperture: Éditions Xavier Barral has now published a number of books related to archives—This is Mars (2013), L’esprit des hommes de la Terre de Feu (2015)—that bridge the fields of science and art. How do such books fit into your mission as a publisher?

Barral: I have always been interested in new forms of reading and language, and how to find the link between them. The concept of time, and its operations, has always obsessed me—the past and what comes next. When looking at pictures of Mars (in This is Mars), we project ourselves in time. How we look today at the Tierra del Fuego peoples Martin Gusinde photographed in South America in the 1920s (in L’esprit des hommes de la Terre de Feu), how Magellan discovered them in the sixteenth century, how they saw Magellan and Westerners … all these issues there, who saw what and how, through the ages. This prompts a reflection that I’ve fed into the books on time and understanding of forms. One is never able to walk back in time as the photograph invites us to do so. In the book Evolution (2007), the understanding of the vertebrates’ evolution happens through time and demonstrates an evolution of the mind.

“Using a collage pieced together from individual video-frames extracted from the footage we try and locate the building within a satellite image of Miranshah.” Image and caption from the video Decoding Video Testimony, Miranshah, Pakistan, March 30, 2012 © Forensic Architecture in collaboration with SITU Research

Aperture: Many images from the early and mid-twentieth-century studies—Bertillon’s metric crime scenes and the portraits from the archive of Russia’s Federal Security Service—show the faces of victims. You mention the Abu Ghraib photographs in your introduction, but few of the recent case studies from Pakistan and Gaza show faces with the same intimacy or detail. Is it easier to “consume” mug shots, criminal studies, and similar types of forensic portraiture with the distance of time?

Dufour: In the book and the exhibition, each image is inhabited by death. And yet, I think they exude the feeling of being relatively detached from the emotional and the personal dimension of the crimes.

I believe this can be explained through three reasons. First, the exhibition focuses more on image as a means of establishing proof of a crime than the crime itself. Regarding the well-known images of the concentration camps made and shown in 1945 by the U.S., Christian Delage’s film Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing Their Crimes (2007) focuses on the how film directors including John Ford assembled footage of Nazi atrocities. As early as 1942, Roosevelt wanted to gather evidence, “credible facts of the incredible” of the “barbarous acts” committed by the Nazis against civilians in the context of judgment for their crimes. Similarly, when the Nuremberg courtroom was reconfigured for the trials, the screen occupied a central place between the accused and the judge, confirming the dominant position of the images presented in the charge of accusing crimes against humanity.

Christian Delage, Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing their Crimes, 2006 (Still: The courtroom during the screening) © Compagnie des phares et balises

Second, the device of investigation induces a “clinical” visual form, which sets the viewer at a remote distance. Emotional distance is required by jurors to judge the facts in court. The image, as produced or presented by the expert, must be free of any effects. In Bertillon’s images, graduations that line the pictures of the scene deliver mathematical deductions. The book of the destruction of Gaza takes the form of a rigorous inventory, resulting in a “cold” finding of the extent of the destruction (in this case, the destruction or damage of fifteen thousand buildings) following the Israeli attacks of 2009.

Finally, the device dehumanizes both the image and the reality of the crime. Streamlining the extreme visual data of the scene, the image produced by the expert often obscures the personal dimension of the crime, while the image is aimed precisely to identify the victim of violence—and the culprit. For example, in an aerial photograph, it’s impossible to distinguish a man on the ground. Bertillon adopts an overhead perspective, but much closer to the body of the victim, far beyond what can be seen by an investigator: the entire field of the crime scene. The terrifying accumulation of portraits of victims of the Great Purge in the former USSR, between 1937 and 1938, does not focus our attention on the tragedy of every individual, every family, but instead reveals the extent of state collective crime (750,000 people murdered in fifteen months) and dismantles the random and unstoppable mechanism of executions.

The area of al-‘Araqib, image 5033, RAF Palestine Survey series, 5 January 1945 © A British Survey of Palestine, 1947

Aperture: Images of Conviction is a scientific and social document, as well as a beautiful object. Even though the “images of conviction” are not decontextualized, some are nevertheless transformed into highly aesthetic pictures, both in the gallery and in the publication. What are the ethical debates about reproducing these archives today? What would you most like for readers to learn from this project?

Dufour: Neither the exhibition nor the catalogue is voyeuristic. On the contrary, the focus is on the device of investigation and the construction of the evidence by the expert. The exhibition shows that the image is not proof in itself, but instead depends on expert interpretation and mediation to establish the facts.

Barral: These reflections on the image allow us to situate ourselves in relation to actions in the world. Because if something isn’t situated in the world, it disappears. These images are used to define our thinking.

Images of Conviction: The Construction of Visual Evidence is part of the 2015 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist exhibition on view at the Aperture Gallery, New York, through February 8 and Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, through February 14.

The post Images of Conviction: A Conversation with Diane Dufour and Xavier Barral appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 3, 2016

Lartigue: Life in Color

Renowned for his vivacious snapshots of friends and family, a new exhibition in Amsterdam showcases the early color photographs of a bon vivant.

By Hinde Haest

J. H. Lartigue, Florette, Vence, May 1954 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

From the age of seven, Jacques Henri Lartigue photographed his wealthy friends and family flying homemade gliders, somersaulting, and racing bobsleds. Apart from occasional publication in the sports magazine La vie au grand air, these images did not make it beyond the family albums until 1963, when Museum of Modern Art curator John Szarkowski exhibited them as curious objects from the annals of modernity. Fame followed the same year with the publication of Lartigue’s work in Life magazine, and later in Boyhood Photos of J. H. Lartigue: The Family Album of a Gilded Age (1966), and Diary of a Century (1970), a collection of Lartigue’s photographs and diary entries edited by Richard Avedon. The belated discovery of Lartigue mirrors the trajectory of the snapshot into the fine arts canon, where it is by now comfortably nested.

J. H. Lartigue, Sylvana Empain, Juan-les-Pins, August 1961 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

Not so for Lartigue’s color photographs, which represent an astounding 40 percent of the 117,577 images in the estate held by the Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue. It would be another seventeen years before the publication of The Autochromes of J. H. Lartigue, 1912–1927 (1980), by Georges Herscher, solely devoted to Lartigue’s experiments with this pioneering, early twentieth-century color process. Another thirty-five years later, both his autochromes and Ektachromes have made it to the walls of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, in Paris, and Foam, in Amsterdam, respectively. Lartigue: Life in Colour, an exhibition currently on view at Foam, features some 140 color reproductions ranging in date from 1912 to 1983. The selection is largely sourced from Lartigue’s personal albums, and exhibited in roughly chronological chapters: autochromes, seasons, portraits, and travel.

J. H. Lartigue, Bibi in the Île Saint-Honorat, Cannes, 1927 © Ministère de la Culture France/AAJHL

Lartigue’s autochromes comprise a colorful reunion with all our favorite characters. We recognize Lartigue’s older brother Zissou with his glider (1914), and his beloved cousin Simone in her (blue!) bobsled wearing a stylish green ensemble (1913). But the plane is no longer airborne. And Simone is keeping still not to ruin the picture, instead of crashing down a gravel road with her tongue out, like she would in sepia. Due to the long exposure time dictated by the autochrome, Lartigue’s relatives are stalled in their playful banter to accommodate the sluggishness of the early color process.

J. H. Lartigue, Florette, Megève, March 1965 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

“Is this still Lartigue? Are we disfiguring an artist?” curator Martine Ravache asks in the accompanying exhibition catalogue Lartigue: Life in Color, recently published by Abrams. Apart from the occasional leaping dog or bobsled, the subject matter is often quaint, even sentimental. The color prints display exactly the pictorial quality for which Lartigue’s black-and-white work had been deemed antithetical. This realization, which is as fascinating as it is uncomfortable, is downplayed by presenting Lartigue as a painter at heart who proclaimed to “see everything with my painter’s eye.”

J. H. Lartigue, Brittany, 1965 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

Yet the picturesque subject matter is not enough to undermine his status as the lovechild of modernity—on the contrary. From the pink pastel of Bibi’s dainty hands (1921) to the fiery red nails of Florette and her glossy magazine (1961), the prints testify to Lartigue’s eagerness to experiment with any new photographic process he could get his hands on. The color work constitutes more than the diaristic musings of a man in love. Marcelle “Coco” Paolucci is conspicuous by her absence, a hiatus that speaks more to the stalled development of color photography than disaffection for his second wife. Discouraged by the sluggishness of the autochrome process, Lartigue stopped photographing in color in 1927. He did not start again until 1949, after two world wars and the development of Ektachrome film.

J. H. Lartigue, Florette’s hands, Brie-le-Néflier, 1961 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

In Lartigue’s unrelenting quest to stall time with whatever medium, color photography would prove his worst ally. The unique glass plates of the autochromes are too fragile to exhibit; his Ektachromes demanded intense restoration before reproduction. Albeit prescribed by preservation, the grainy enlargements fail to communicate the refined brilliance of an actual autochrome, or the three-dimensional experience of a stereoscopic image. Even the albums, diaries, and logs kept by Lartigue have not made it into the showcase. They are represented by facsimiles on museum board that do little but emphasize the absence of the originals.

J. H. Lartigue, Jacqueline Roque and Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Francine and Carole Weisweiller, and sitting in front, Florette, bullfight, Vallauris, 1955 © Ministère de la Culture–France/AAJHL

In the spirit of Lartigue, the battle against oblivion is waged with the reproductive means of our time. Other exhibitions at Foam, such as Vivian Maier: Street Photographer (2015) and Francesca Woodman: On Being an Angel (on view concurrently with Lartigue) display a curatorial concern for rediscovery and reproduction of the archive. Tracing the incremental disclosure of Lartigue’s albums since Szarkowski reveals the making of an artist through careful curation. And so the exhibition texts about Lartigue’s love for the seasons or his relationship with God sidestep the more uneasy subtext: the jerky trajectory of Lartigue’s color photographs from the amateur album to the museum wall.

Hinde Haest is a photography curator based in Amsterdam.

Lartigue: Life in Colour is on view at Foam, Amsterdam, through April 3, 2016.

The post Lartigue: Life in Color appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 29, 2016

Yasuhiro Ishimoto: Katsura

At a seventeenth-century villa in Kyoto, a young photographer merged modernist vision with exquisite design. Thirty years later, he returned for a second look.

By Russet Lederman

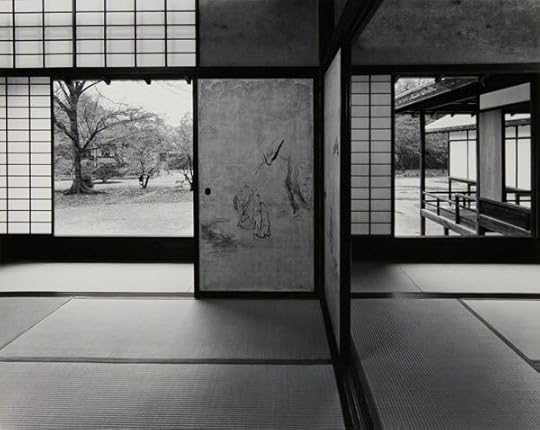

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Katsura Villa, 1953–1982. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York

As a young man, the American-born Japanese photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto first visited Kyoto’s Katsura Imperial Villa in 1953. Edward Steichen, at the time the photography curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, had asked Ishimoto to escort the museum’s design curator for his research on Japanese shrines, temples, and gardens for a forthcoming architectural exhibition. Ishimoto was the perfect guide. A recent graduate of Chicago’s Institute of Design, where his studies under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind merged modern American photography with Bauhaus design theory, Ishimoto immediately recognized Katsura as a modern subject. Five decades later, his two major studies of Katsura are the subject of a solo exhibition at Peter Blum Gallery, which together describe shifts in perception, the transitory nature of place, and the maturation of a photographer.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Katsura Villa / Main Room, right, and the Second Room left, of the Middle Shoin, viewed from the north-east, 1981–82. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Profoundly impressed by the beauty of Katsura’s traditional Japanese architecture and gardens, Ishimoto could not help photographing in a manner that filtered it through his Western training. (He developed an early interest in photography while he was interned at the Granada [“Amache”] Relocation Center in Colorado during World War II.) In 1954, armed with his 4 x 5 German Linhof camera, Ishimoto returned to Katsura for a month-long stay. His attention to form, shape, and light are evident in the four black-and-white photographs from this visit on view in the show (taken in 1954 and printed in 1980). Focusing on the stepping-stone paths that snake through Katsura’s gardens and the clean geometric lines of the stark interior and exterior spaces, Ishimoto’s images emphasize texture and abstract pattern within the minimalism of Katsura’s traditional Japanese design.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Katsura Villa, 1981–82. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Constructed in the seventeenth century, Katsura is only open to visitors through specially requested tours organized by the Imperial Household Agency, which oversees the estate. Because few photographers were admitted in the 1950s, Ishimoto’s 1953–54 photographs received broad attention when first published in Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese Architecture (1960), a book that also includes writings by architects Kenzo Tange and Walter Gropius. This original edit of the book, however, which would be followed by several reedits and reinterpretations, was a bit of a disappointment for Ishimoto due to Tange’s unauthorized cropping of his original images. On view in this exhibition, uncropped as initially intended, Ishimoto’s early black-and-white images of Katsura show a prerenovation villa with little focus on ornamentation.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Tea Room of the Shokintei Pavilion, viewed from the north-east. Kneeling Entrance, 1981–82. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York

In the early 1980s, Ishimoto revisited Katsura with the same 4 x 5 camera. However, this time he shot the villa and its grounds using both color and black-and-white film. In the intervening years, the villa had been restored; Ishimoto’s five larger scale 1981–82 color images show nuanced differences in both photographer and location. The addition of color noticeably transforms Ishimoto’s images of Katsura. Where in earlier images there was a quiet, subdued approach, these later photographs reveal pockets of bright color in small stones that fill crevices in the garden paths, fall foliage that peeks through windows and beyond terraces, and patterned expanses that fill interior doors and walls. The restoration had reinstated much of Katsura’s original decoration and ornamentation. As a mature photographer, Ishimoto was able to embrace a broader visual sensibility that depicts flourishes that were mostly omitted in his 1950s black-and-white photographs. A significant group of these color images comprise Ishimoto’s 1983 book on Katsura, entitled Katsura Villa: Space and Form.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Garden view from the North Veranda of the Shokintei Pavilion. Earthen Hearths in the foreground, 1981–82. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York

In several of his images from the 1980s, Ishimoto photographed specific locations from relatively similar vantage points. Although this exhibition does not allow for a one-to-one comparison of images of specific sites, the ability to see the overall transformation of both place and photographic vision is strongly apparent. These distinctions are also explored—but not as overtly, due to the absence of color—within the third component on view, a limited-edition portfolio of Katsura images printed in 1989 and published by Photo Gallery International in Tokyo. Mixing black-and-white images from the 1950s and 1980s series, the fifteen photographs that form the Katsura Villa Portfolio are of similar size and tonality. Five of the prints hang on the wall, with an unframed print and the portfolio box in a gallery vitrine. (Another framed print can be seen in the back office.) Perhaps due to the portfolio’s uniform image measurements, paper stock, and print tones, a closer inspection is required to detect the subtle differences between the 1953–54 and 1981–82 black-and-white prints of Katsura’s pre- and postrestoration gardens and buildings. But looking closely is what Yasuhiro Ishimoto’s photography is about. These images invite viewers to slow down as they observe the transitory and evolving nature of a particular place photographed during two distinct periods in Ishimoto’s career.

Russet Lederman, a researcher and writer, teaches art writing at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto: Katsura is on view at Peter Blum Gallery in New York through February 20, 2016.

The post Yasuhiro Ishimoto: Katsura appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 28, 2016

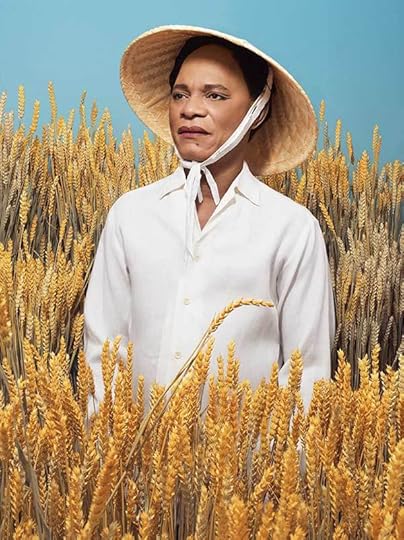

Samuel Fosso: Emperor of Africa

A master of theatrical self-portraiture turns toward China.

By Olu Oguibe

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013 © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

As a teenage photographer and commercial portrait–studio owner in Bangui, Central African Republic, in the 1970s, Samuel Fosso took turns between client sittings in his studio to reel off self-portrait after self-portrait, modeling the fashion of the day: colorful platform shoes, bell-bottomed pants, huge dark sunglasses, tight-fitted shirts, and blowout Jimmy Cliff rude-boy fisherman hats typical of postcolonial African urban youth of the period. Using his own body and the nonchalant, adventurous power that only a teenage studio proprietor could wield, Fosso produced a formidable look book of African urban youth style in the wealthy, immediate postindependence decade.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013 © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

After those images were discovered in the 1990s, their cultural significance brought Fosso into a vibrant circle of young African intellectuals: writers, international curators, and artists like Simon Njami and Bili Bidjocka, Okwui Enwezor, Iké Udé, Yinka Shonibare and this author, and Congolese urban chronicler Chéri Samba, among others. He inadvertently became part of a larger conversation, an emerging postcolonial African cultural movement, no less, that was searching for new languages and meanings, and engaged in deeper historical preoccupations relevant not just to the youthful, curious ego, but even more so to that great task that Frantz Fanon posed their generation: to discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013 © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

The matrix of social, historical, and conceptual investigations that this movement engaged in began to steer Fosso’s application of the self in front of the camera beyond his earlier preoccupation with the adolescent ego. Before him, Udé was also using self-portraiture, or what he referred to as “the regarded self,” in even more diverse ways—to not only construct critiques of race and representation but rediscover and reinvent the complexities and subtleties of traditional West African ideas of beauty, gender fluidity and role reversal, and theater. Udé’s engagement with his native Igbo traditions of body art and performance, especially Igbo masquerade traditions, certainly held profound meaning for Fosso, who shares the same Igbo heritage, and it was by performing the persona of his late grandfather, an Igbo deity priest, in his series Le rêve de mon grand-père (The dream of my grandfather) in 2003 that Fosso completed his conceptual transition.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013 © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

Subsequently, in the series African Spirits (2008), in which he reenacts iconic images of African independence and liberation struggle leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Samora Machel, Haile Selassie, and Nelson Mandela, Fosso in fact created a parallel to the Igbo tradition in which adepts or community members don masquerade costumes to channel ancestral spirits during festive seasons. By donning the costume and transforming oneself into a masking figure, one took on the persona of a visiting ancestor and served as a symbolic or ritual bridge between the past and the present, and even between the sacred and the quotidian. In African Spirits, Fosso transformed himself into a masquerade of sorts, through which the spirits of the guardians of African liberation were made manifest.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series Emperor of Africa, 2013 © Samuel Fosso. Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

In Emperor of Africa (2013), his most recent series, Fosso channels a different spirit by restaging iconic images of Chinese leader Chairman Mao not only as a liberator who, like the subjects of Fosso’s African Spirits series, is highly admired in Africa, but also as the founder and symbol of a modern imperial behemoth that is currently engaged in an expansive long march across Africa. Though China’s growing economic and cultural presence is eagerly embraced by many African leaders, it has raised concerns, especially among the continent’s intellectuals. In a complex, richly layered performance worthy of an African masquerade, Fosso’s Mao is both ancestral figure and absent dictator, almost like the patriarchal leader in Gabriel García Márquez’s 1975 novel Autumn of the Patriarch, who’s never seen yet looms large over his dominion. Fosso, as performer, is both subject and inquisitor, the man behind the mask who interrogates empire and postcolony alike, the ultimate Fanonian “man who questions.”

Olu Oguibe is a professor of art at the University of Connecticut.

This article was originally published in Aperture issue 221, Winter 2015, available for purchase or in the Aperture Digital Archive.

The post Samuel Fosso: Emperor of Africa appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers