Aperture's Blog, page 139

May 23, 2016

Upcoming Workshops, Fall 2016

Upcoming Workshops for Fall 2016 include:

Jason Fulford

Friday, August 19–Tuesday, August 23

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb

Artist Talk: Friday, September 23

Workshop: Saturday and Sunday, September 24–25

Shelby Lee Adams

Saturday, October 8–Monday, October 10

John DeMerritt

Saturday and Sunday, October 15–16

Matthew Connors

Saturday and Sunday, November 19–20

More information and details coming soon! Contact us at education@aperture.org.

The post Upcoming Workshops, Fall 2016 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 17, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Ming Smith and the Kamoinge Workshop

Routinely excluded from the mainstream art world, in the 1960s, a group of African American photographers formed a collective to promote and exhibit their work. For one promising young artist, the experience was transformative.

By LeRonn P. Brooks

Anthony Barboza, The Founders of Kamoinge, 1973. Ming Smith pictured first row, second from left. Courtesy the artist and Schiffer Publishing

In the early 1970s, Ming Smith was working as a model in New York City but becoming serious about photography. While on a go-see, she made an acquaintance that would change the course of her artistic development: one with Anthony Barboza, a member of the Kamoinge group and currently the group’s director. In due course, Barboza invited Smith to join Kamoinge and she began exhibiting with the group. Through Kamoinge, an association of black photographers formed in New York in the 1960s, Smith began developing her craft, eventually exhibiting with the group as its first female member.

Kamoinge itself began when two separate groups of young black photographers—including Louis Draper, Earl James, and Calvin Mercer, among others—gathered in 1963 to discuss ways of using their work to address the civil rights movement and the troubling conditions of black people in their communities. It was concurrent with other progressively minded black artist groups such as Spiral, also based in New York, which included painters Romare Bearden (whom Smith would photograph in 1977), Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, and Emma Amos, among others. Kamoinge was initially mentored by more established photographers such as Larry Stewart and Roy DeCarava served as its first director. More than just a photography collective, Kamoinge (named for a word from the Kikuyu language meaning “a group of people acting together”) was an important forum for creative political activity.

Ming Smith, Pass the Plate, Harlem, 1972. Courtesy the artist

Kamoinge was not as much an organization, strictly speaking, as it was an informal circle of trust, affirmation, and career development. For Smith, just at the start of her practice, the group provided important forms of peer-to-peer discourse, meaningful critiques, and exhibitions. It also provided what can only be described as a methodology of feeling. Draper, in particular, routinely asked to see Smith’s images and offered insightful notes and suggestions. During an era in which black artists were routinely excluded from the mainstream art world, Kamoinge—from one generation to next—exemplified the principle that black artists could not afford to dismiss, or be blind to, important realities within their communities.

The influence of Kamoinge, and specifically of the group’s aspirations for political change, can be clearly seen in Smith’s work. Her photographs reveal the underlying tensions between citizens and communities. She positions her subjects as intimates feeling their way through specific conditions and circumstances, and deliberately invokes this exchange in her images. “The magic of photography,” Smith told me recently, “is seeing and capturing the moment.”

Ming Smith, Brown Skinned Model and Steeple, New York, 1971. Courtesy the artist

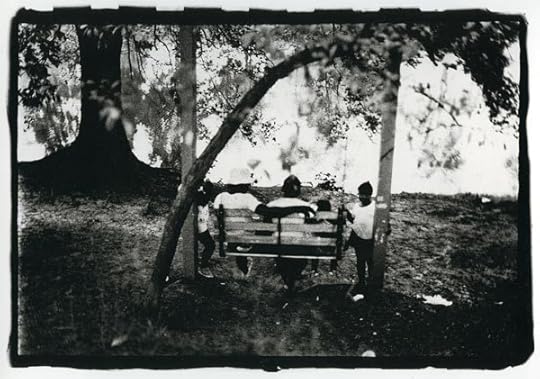

Her photograph Family Free Time in the Park (1982), made in Piedmont Park, Atlanta, exemplifies this feeling, and is characteristic of her work. The viewer who examines this image hoping to find life as the accumulation of cold and pointed denotations will perhaps be disappointed that the photograph does not submit the totality of its implications to those who lack imagination. It is a startling interpretation of a black family placed between hard formal contrasts. There was jazz in the park. It was summer. The black and white clash like thrusts of heat and cold, sounds and silences. Smith, on an afternoon stroll, synced these impressions into an image of feeling and an uneasy beauty, and this treatment correlates with larger societal tensions in Atlanta.

When Smith made Family Free Time in the Park, Atlanta was in mourning. Twenty-eight black citizens—many of them children—had been murdered there between 1979 and 1981, and the city was preoccupied by a pervasive terror. Although Wayne Williams had recently been sentenced for the murders, questions lingered about the credibility of the evidence presented against him. President Reagan had met with city officials and allocated funds for the investigation; the FBI committed nearly forty agents to the effort. Psychics, bounty hunters, and the Guardian Angels had marched into the city offering their services, but left without verifiable clues or a suspect. The city was turned out, and nothing. Centuries’ worth of layers of systemic racism had rendered Atlanta’s black communities vulnerable to the kind of terror that thrives in the darkness. It was clear that invisibility had its consequences.

Ming Smith, Family Free Time in the Park, Atlanta, Ga., 1982. Courtesy the artist

In 1982, Atlanta had yet to shed the unease, and here a black family attempts triage as the terror of the recent past slumbers. They are present but semi-legible. Veils of partial social erasure cover their lives. Their skins, shaded by darkness, and the children’s eyes, also shaded, are plausible metaphors. Just above, light bristles through the leaves’ stillness and peters out in long edges. The parents have their backs to us. The arch of the father’s arm is a fragile covenant. Traces of sun extend from the large pool of light in the background; the light paces toward the viewer, carrying with it the impression of a nearness that does not exist. This psychological distancing persists even in such an overwhelming light. Ming Smith learned much from Kamoinge, but her photographic vision and this image have lives of their own.

LeRonn P. Brooks is a writer, art historian, and recipient of poetry fellowships from the journal Callaloo and the Cave Canem Foundation.

Timeless: Photographs by Kamoinge was published by Schiffer in 2015.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Ming Smith and the Kamoinge Workshop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 16, 2016

2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards Shortlist Exhibition on view at Scotiabank CONTACT Festival

The post 2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation Photobook Awards Shortlist Exhibition on view at Scotiabank CONTACT Festival appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 15, 2016

Tim Davis: About About

Tim Davis, The Collector, 2015

Join visual artist, poet, and photographer Tim Davis for this two-day workshop, About About, which is intended to help photographic artists understand, discuss, conceptualize, and write about their work. Photography has become so ubiquitous, and digital culture offers such easy receptacles for pictures, but it also allows artists to make work without thinking through what it really amounts to. This workshop is designed to help photographers craft their work into a meaningful project—whether a publication or an exhibition—that makes sense for their inner directives. While making photographs is a way to understand yourself, developing those photographs into a successful project is a way to communicate how you see the world.

The first day will be a series of discussions, as each participant gives a short presentation of his or her work, either in print or digital form. Davis will guide a critical analysis of each participant’s project, with an emphasis on how to make the work more relevant, true, comprehensible, and pointed. The afternoon will be left free for making new work using the new guidelines.

During the second day, participants will present their images created on the previous day, and discuss how to write about one’s own work. An artist’s statement will be crafted by each participant, to capture the ideas the workshop has generated.

Light refreshments and lunch will be served both days. Please contact Aperture staff regarding any dietary requirements and/or restrictions at least one week prior to the workshop.

Tim Davis is a photographer, writer, and musician living in upstate New York and teaching photography at Bard College. His recent exhibitions include a sound installation at the Tang Museum, Saratoga Springs, Unphotographable, for which he sampled the word unphotographable from dozens of versions of “My Funny Valentine” into a single composition. He is hard at work on a project called Cartoons, inspired by the cartoonist B. Kliban, in which he is turning jokes and comedic observances into photographs. His books include My Life in Politics (Aperture, 2006).

Tuition: $500 ($450 for currently enrolled photography students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above)

DEADLINE EXTENDED!

Register by Thursday, May 12.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

The post Tim Davis: About About appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 12, 2016

Aperture Celebrates the Launch of Vision & Justice

Sarah Lewis, Guest Editor of “Vision & Justice,” introduces Aperture’s summer 2016 issue at the Ford Foundation in New York. Photograph by Margarita Corporan

On Tuesday, May 10, Aperture celebrated the release of “Vision & Justice,” the magazine’s summer issue. Guest edited by writer, curator, and art historian Sarah Lewis, “Vision & Justice” explores the role of photography in the African American experience, from Frederick Douglass to the rise of #BlackLivesMatter. “American citizenship,” Lewis writes in her foreword, “has long been a project of vision and justice.”

Hank Willis Thomas, Sarah Lewis, Darren Walker, and Sarah Jones at the launch of “Vision & Justice.” Photograph by Margarita Corporan

Hosted by Darren Walker, President of the Ford Foundation, the event had a centerpiece of a series of vibrant and moving readings by contributors and friends, staged in the Ford Foundation’s East River Room and framed by wide-angle views of the United Nations. Aperture’s editor, Michael Famighetti, welcomed the audience and recounted his first conversations with Sarah Lewis about the issue, before inviting Lewis herself to introduce the themes and images to be found in the pages of “Vision & Justice.”

Chelsea Clinton reads from an essay by James Baldwin at the launch of “Vision & Justice.” Photograph by Margarita Corporan

The acclaimed actress and performer Sarah Jones opened the readings with a passage on Frederick Douglass from Sarah Lewis’s book The Rise. Artist Hank Willis Thomas, who said he likes to “shake things up,” asked everyone present to photograph the person seated beside them and post their pictures to social media with the hashtag #VisionJustice. Thomas then offered a tribute to his mother, Deborah Willis, the visionary photography historian and author of numerous books on African American photography and visual culture.

Diane Lewis and Deborah Willis at the launch of “Vision & Justice.” Photograph by Margarita Corporan

Writer and critic Margo Jefferson read from her essay in “Vision & Justice” on Lorna Simpson’s collages, which draw upon imagery from vintage issues of Jet and Ebony magazines. “I like to imagine that in the old world of black periodicals she might have been featured as Madame Lorna, designer extraordinaire, her creations sought for the top balls and fashion shows,” she said. Carrie Mae Weems, after reading a passage from her new book Kitchen Table Series, spoke of the artist as inventor, honoring all of the artists in the room, including Julie Mehretu, Deana Lawson, and Lyle Ashton Harris, among many others.

Garnette Cadogan introduces the work of Radcliffe (Ruddy) Roye at the launch of “Vision & Justice.” Photograph by Margarita Corporan

Garnette Cadogan read a profile of Radcliffe (Ruddy) Roye, the prolific street photographer who has accumulated thousands of images on his popular Instagram feed. Chelsea Clinton shared a passage from The Creative Process by James Baldwin. And the evening concluded with Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s stirring homage to the great New York street photographer Jamel Shabazz. “Present in [his] work is a fierce commitment to visibility,” Muhammad said. “His lens has always seen more joy, more life, more blackness than our own eyes are capable of.” A testament to the power of the artistic community in New York and beyond, the launch of Vision & Justice teemed with joy.

Margo Jefferson at the launch of “Vision & Justice.” Photograph by Margarita Corporan

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Aperture Celebrates the Launch of Vision & Justice appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Vision & Justice Online: She Walked in Beauty

Amid the racial tensions of the 1960s, Jet magazine captured African American life with grace and power. For an influential screenwriter, one cover was personal.

By Susan Fales-Hill

Cover of Jet magazine, May 27, 1965

This is a picture that masks a thousand indignities. The year was 1965. The country was in turmoil in the wake of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The Vietnam War raged and the South was on fire with the civil rights movement. My family had recently returned to the United States from Rome, Italy, where my white Anglo-Saxon Protestant father, Timothy Fales, and Haitian American mother, Josephine Premice, hounded by a racist press and relentless hate mail in the wake of their “scandalous” marriage in 1958, had taken refuge. As punishment for his “misalliance,” my father was fired from his job at a shipping company and his name was permanently expunged from the Social Register, America’s answer to Debrett’s Peerage. In “deigning” to wed a black woman, he had forfeited his place in our country’s Brahmin caste.

At three, I was blissfully oblivious to my parents’ struggles in our “pigmentocracy,” as well as to the turbulence around me. My mother, a brilliantly gifted actress, singer, and dancer—and the family’s pied piper—created an oasis of love, beauty, and limitless possibility. This photograph, taken for the cover of the black-owned weekly magazine Jet, captures her indomitable spirit and mesmerizing influence. In this image, as in life, my brother and I looked to her to see our true selves and learn the way forward. She taught us by example never to let life’s circumstances break our stride.

Though upon returning to New York my mother spent her days being denied rental apartments in a city of de facto segregation, she refused to be defined by the willfully ignorant and blind. Each morning, she donned full makeup and an exquisite ensemble, her armor in a business that reduced nearly all black actresses to playing maids or prostitutes on-screen and in a world that treated her as a second-class citizen. In a land of injustice, “she walked in beauty.”

No mainstream publication at the time would have featured a black actress and her children on its cover, and even to this day such images are cause for jubilation. In the latter half of the twentieth century, Jet and its sister magazine, Ebony, captured the dimensions of black life and achievement the mainstream media rendered invisible, and thus gave black America a vital mirror in which to see itself. Through this family portrait, my ridiculous Minnie Pearl hat notwithstanding, Jet offered my mother the opportunity to remind her own children, as well as the larger black community, to heed the words of champion prizefighter Jack Johnson: “I was a brunette in a blonde town, but gentlemen, I did not stop steppin’.” We walk on.

Susan Fales-Hill is an author, screenwriter, and television producer.

Read more from Vision & Justice or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: She Walked in Beauty appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 11, 2016

Recap of Connect Member Meetup

On May 3, Aperture Connect Members came together for the group’s second meetup at the private home of archivist and former documentary filmmaker Patrick Montgomery. Montgomery’s The History of Photography Archive is an impressive collection of more than ten thousand objects, including photographs and ephemera, relating to the first hundred years of photography’s history.

Connect Members handled rare albums and photographic works, including early carbon and salt prints, and the first documented school portraits, such as a daguerreotype of the class of 1861 from Paris’s École Polytechnique. Also noted was the important role Aperture’s founders Ansel Adams and Beaumont Newhall played in photography’s development as an artistic medium.

Amelia Lang, executive managing editor of Aperture Foundation’s book program, spoke to Connect Members about the foundation’s unique position in the publishing field, emphasizing that photography and the photobook is a platform for both photographers and photography enthusiasts to learn about the unfamiliar.

Aperture Connect is a dynamic group of supporters (ages 21 to 37), residing in the New York Tri-state area, who seek to further their knowledge and understanding of photography, publishing, and the international photo community.

Click here to become an Aperture Connect Member today and to receive an invite to the next meetup on June 28!

The post Recap of Connect Member Meetup appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 7, 2016

Mary Virginia Swanson: Business of Photography Series

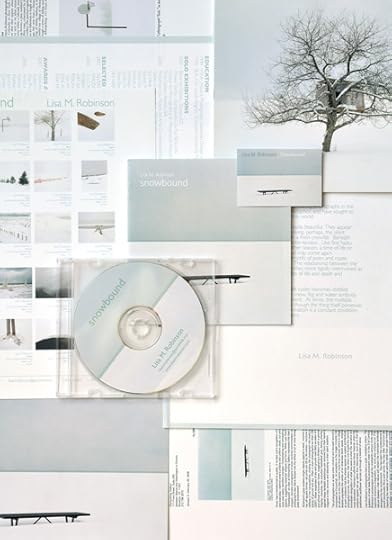

Promotional pieces for artist Lisa M. Robinson

Join Mary Virginia Swanson for one or both of the remaining sessions of the Business of Photography workshop series. Participants can register for the seminars individually, or as a package of two for a reduced price. Light refreshments and lunch will be provided.

Introduction to Multiple Markets

Saturday, April 23, 2016, 11:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m.

One of the most exciting recent developments for photographers is the growth of new markets for their work. Whether a fine print is shown in a museum or in a corporate office, reproduced as a book cover illustration or featured in product advertising, the value of that photograph is different for each buyer. In this seminar, Swanson will provide an overview of the opportunities for, and the value of, your work within today’s diverse photography marketplace. This session is sold out. Please fill out the form below to be added to the waiting list.

Your Work, Your Brand

Saturday, May 7, 2016, 11:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m.

In today’s world, making meaningful contact with industry professionals is challenging. A photographer’s work may speak for itself, but how can you effectively present your work in a productive and memorable way? During this session, you will learn what components comprise a successful brand, and learn how combining and even integrating your print and social media tools can make the strongest first impression with your targeted audience. Registration ends Sunday, May 1.

Mary Virginia Swanson is an author, educator, and consultant who helps artists find the strengths in their work, identify appreciative audiences, and present their work in an informed, professional manner. Her seminars and lectures on marketing opportunities aid photographers in moving their careers to the next level. Swanson is the recipient of the 2013 Focus Lifetime Achievement Award from the Griffin Museum of Photography, and the 2014 Susan Carr Award for Education from the American Society of Media Photographers. The Society for Photographic Education named her the 2015 Honored Educator. Swanson coauthored Publish Your Photography Book (revised edition, 2014) with Darius Himes. Swanson is currently working on a new publication, Finding Your Audience: An Introduction to Marketing Your Photographs.

To register, please complete the form below.

Please note: your registration is not complete until Aperture has received payment. An Aperture staff member will send you a confirmation e-mail with additional information regarding what to bring how and how to prepare for the workshop.

Fill out my online form.

Fill out my Wufoo form!

If you have any questions please contact us at education@aperture.org.

General Terms and Conditions

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements.

Release and Waiver of Liability

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

Refund/Cancellation Policy for Aperture Workshops

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

Lost, Stolen, or Damaged Equipment, Books, Prints Etc.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Mary Virginia Swanson: Business of Photography Series appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 5, 2016

Revisiting Seydou Keïta

Celebrated for his studio portraiture in the 1950s, Bamako’s most prominent photographer mastered the elements of style.

By Julie Crenn

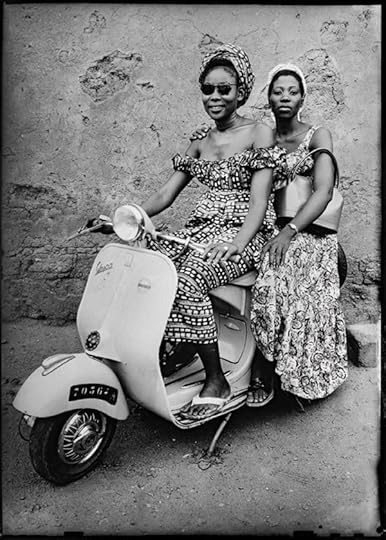

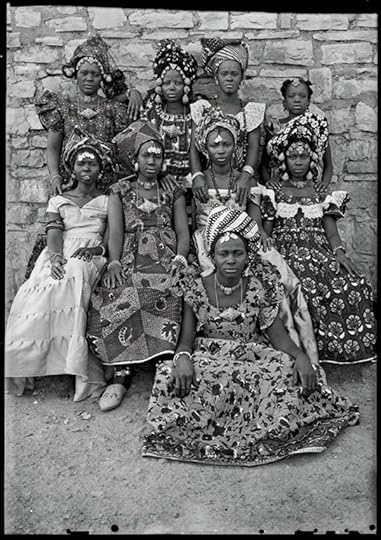

Seydou Keïta, Sans titre, 1949. © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC. Courtesy CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Genève

This spring, Paris pays tribute to Seydou Keïta, a pioneering figure in West African and international photography. Along with Malick Sidibé, J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, Jean Depara, Philippe Koudjina, and many others, Keïta embodies the foundations of portrait photography in Africa. He belongs to the family of twentieth-century masters of photography, along with August Sander, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Helen Levitt. Even though his work has been included, since the 1990s, in major surveys connected to photography or African art at large, the Grand Palais currently presents his second Parisian retrospective exhibition. Organized by Yves Aupetitallot, the selection of works comes primarily from the Contemporary African Art Collection, as well as from the personal collection of André Magnin. By making the choice to exhibit both original vintage photographs and larger prints, the exhibition underlines the memorial dimension of an oeuvre both personal and collective.

Seydou Keïta, Sans titre, May 21, 1954. © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / photo collection Alexis Fabry, Paris

For Keïta, a self-taught artist, portraiture became a passion. Born in 1921, he worked independently in his studio between 1948 and 1963, photographing all of Bamako with great inventiveness. (From 1963 to 1977, he was requisitioned by the Republic of Mali as an official photographer.) “Having your portrait taken was a big deal, it was really important to give the best possible image of each person,” Keïta stated in 1997. “Often they took on a serious air, but I think it was probably because they were intimidated—it was new.” The result, across thousands of portraits, reflects careful staging with various elements: the decor is set thanks to the arrangement of wax fabrics, hung, folded, or draped. Their motifs participate actively in the image composition. The poses were meant to define the sitter—nothing was left to chance. As odalisques, standing, hieratic, sitting, three-quarter length, on a scooter, the poses are taken from paintings and engravings or cinema.

Seydou Keïta, Sans titre, 1953 © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC. Courtesy CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Genève

At the center of this exhibition are black-and-white portraits of women, men, couples, and families, forming a gallery where characters of competing elegance parade in front of our eyes. Large-format prints give way to the smaller, vintage images, which generate more intimate and precious relations. The subjects stare us in the eye and draw us in. Through these images, the face of a society that has been independent since 1960 is forged. They reflect dynamism, emancipation, and claims to identity. The clothes, accessories, and objects give a personal, and even intimate, dimension to the portraits. They account for a personality, a group, who they are and how they want to be seen.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1949-1951. © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC. Courtesy CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Genève

During colonization, photography was anthropometric; it was used to identify, classify, and sometimes humiliate the colonized peoples. Individuals were reduced to being objects of study, even sometimes photographed frontally in the most neutral manner. Keïta’s portraits have managed to free themselves from racist stereotypes, returning beauty and individual personality to Malian people. These photographs constitute a visual heritage imbued with great personal and collective wealth.

Seydou Keïta, Sans titre, 1959-60 © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC. Courtesy CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection, Genève

Keïta’s portraiture has had an immeasurable influence not only on African photography, but throughout the world. Following Keïta’s heritage and his will to return a form of dignity to the subject in the image are artists such as Zanele Muholi, who presents the face of black LGBT citizens, often subjected to outrageous violence, and Leila Alaoui, the Franco-Moroccan photographer who died as a victim of a terrorist attack in Ouagadougou in January, and whose series The Moroccans, begun in 2011, allowed for the meeting of different tribes and generations that make up the Moroccan identity. Rather like in Keïta’s work, a critical and even political dimension can be found in the adornment of fabrics, play of traditional and modern clothing, ornamentation, and highly designed staging in the work of Samuel Fosso, Omar Victor Diop, Kehinde Wiley, and Baudouin Mouanda. There are countless others. As a consequence, this exhibition on Seydou Keïta instills the decisive legacy of his work and showcases the commitment of the next generation of artists on the African continent and in the diaspora.

Julie Crenn is an art critic and curator based in Paris. Translated from the French by Caroline Hancock.

Seydou Keïta is on view at the Grand Palais, Paris, through July 11, 2016.

The post Revisiting Seydou Keïta appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

May 4, 2016

Promised Lands

Are Israel and the West Bank an oasis, homeland, or colonial state? Twelve photographers set out to describe a contested territory.

By Ian Bourland

This Place, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum curated by photographer Frédéric Brenner, opens with a monumental tableau by Jeff Wall. Daybreak (2011) restages a happenstance encounter with vividly garbed bedouin olive pickers, found sleeping on the ground near a prison in the Negev. Typically, for Wall, the scene juxtaposes the immediacy of documentary with the precision of cinematic postproduction. In spite of its artifice—Wall used a team of assistants over the course of several weeks to make the image—Daybreak isolates the uncanny moments and parallax of vision that This Place seeks to draw into view.

Frédéric Brenner, The Aslan Levi Family, 2012. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York © the artist

The exhibition is an elaboration of a long-term project through which Brenner has charted the global Jewish diaspora—often by way of staged family portraiture that calls to mind both August Sander and Tina Barney. Brenner’s own work is included here, but complemented by and resituated amidst the projects of the eleven other photographers he invited to immerse themselves in Israel and the West Bank between 2009 and 2012. Recognizing the contested realities of quotidian life there, his ambition was to enact “une parole poétique,” attempting to transcend the stale binaries through which this landscape is often figured. Such a “poetic” approach risks a retreat into sentimentality, eliding the high stakes of a land inscribed by seemingly intractable conflict. But, taken as a whole, the discrete practices brought together in This Place are more than the sum of their parts: the resulting six hundred photographs on display produce a humane and at times revelatory counterarchive of a place known, by turns, as an oasis, a homeland, a colonial state, or a utopian site of return.

Martin Kollar, Untitled, from the series Field Trip, 2009–11. Courtesy the artist

With its telescoping levels of magnification, and its emphasis on the taxonomic or seemingly banal environments, This Place might trace its conceptual roots to the landmark 1975–76 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, at the George Eastman House. There are, in fact, overlaps in personnel from that earlier project, such as Stephen Shore and Thomas Struth. In This Place, Shore provides a suite of majestic desert landscapes. Struth contributes large-scale inkjet prints that oscillate between moody interiors, vernacular architecture, and crisp family portraiture; his Basilica of the Annunciation, Nazareth (2014) is at once hauntingly intimate and disconcertingly inert. The aesthetic virtuosity of such photographs might, as standalone images, either distance or romanticize contemporary Israel, but in the context of the exhibition’s larger framework, they underscore the ways in which the same topographies and streetscapes can be filtered or repurposed—say from Shore’s sublime promontories, or under Struth’s clinical scrutiny.

In a more explicitly conceptual register, Fazal Sheikh reprises the surveillance investigations of Ed Ruscha and Robert Smithson, strafing the open desert for signs of life. Desert Bloom (2015) is the most subtle and textually reliant work on display, comprising a large grid of beige imagery—denuded landscapes bearing scars of human intervention. Sheikh provides a brochure describing the coordinates of each photograph and detailed field notes researched upon return from his travels. The approach is systematic but not deadpan, and parlays the colonial logic of the aerial survey into a sustained psychogeographic history of seemingly “empty” space.

Gilles Peress, Contact Sheet, Palestinian Jerusalem, 2013. Installation view, detail © the artist

Throughout the exhibition, sustained looking on the part of both the photographer and viewer is counterbalanced with more documentary immediacy. For instance, for This Is Where I Live (2012–15), Wendy Ewald put the camera in the hands of constituencies—urbanites and villagers, children and elders—reproducing dozens of the results at roughly 5 by 7 inches. Ewald’s project is sociologically complex and politically audacious, but, like Gilles Peress’s grid of medium-scale street scenes in Palestinian Jerusalem (2013)—handheld, off-kilter shots that capture a cosmopolitan bustle—it lends itself less to museum viewing than to a more asynchronous, digital interface. Still, Ewald and Peress draw into sharp relief the subtle boundary between the archive as framework and as formal structure.

Jungjin Lee, Unnamed Road 083, 2011 © the artist

Such taxonomic intensity is, in turn, complemented by moments of old-school formalism and blunt humanism. Jungjin Lee’s panoramic registration of natural forms on handmade paper is gauzy and surreal, bearing uncanny traces, like latter-day rayograms. Celebrated Czech photographer Josef Koudelka frames the bleak surfaces of the partition wall being built by Israelis in the West Bank, which in high-contrast black and white evokes the carceral realities of his youth in Eastern Europe. Koudelka’s works literally partition the exhibition—the wide expanse of his panoramic shot is displayed faceup on an elongated wall in miniature. And THEM (2010–11), Rosalind Fox Solomon’s square format series, hearkens to a bygone golden age of street photography. Unabashedly lyrical and intimate, Solomon’s images would not be out of place in the great midcentury photography exhibitions organized by Edward Steichen or John Szarkowski.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Jerusalem, 2011 © the artist

In many ways, Brenner’s project is of a piece with such vintage curatorial modes, which prioritized modernist finish and a roseate universalism, but also with the later work of Allan Sekula, who merged metaphor and unflinching realism. This Place is aware of the confounding nuance and high stakes of representing even the most banal scenes of everyday life in Israel and the West Bank, but the exhibition makes a confident claim for the capacity of art to address public debates in ways that photojournalism cannot. The danger, as curator T. Z. Toukan has noted, is in aestheticizing rather than confronting the complexity of this contested terrain. Speaking of art in Palestine in 2010, he wondered, “Does trauma—presented in an art context—become aesthetically appealing, telegenic so to speak, and, if so, can the telegenic aspect be a productive thing?” This Place, a compelling and dissonant experiment, leaves that question unanswered.

Ian Bourland, a historian of photography and critic of the global contemporary, is an assistant professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

This Place is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through June 5, 2016.

The post Promised Lands appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers