Aperture's Blog, page 135

July 14, 2016

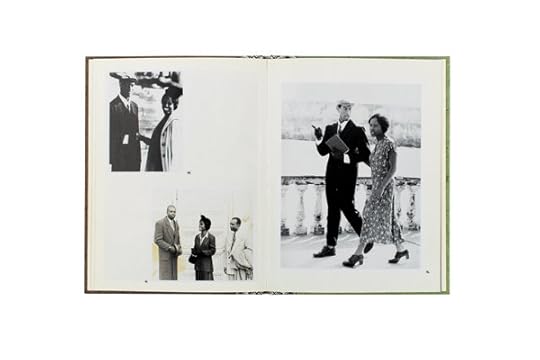

Kristen Lubben on Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye The Fae Richards Photo Archive

The Fae Richards Photo Archive is a collection of glamour shots, stills from movie sets, photobooth portraits, family snapshots, and typewritten captions that tell the story of a forgotten black actress and singer whose career was sabotaged by racial typecasting, and whose relationships with other women marginalized her even further in mid-twentieth-century America. While eminently plausible, the book (and the character of Richards) are the creations of filmmaker Cheryl Dunye and photographer Zoe Leonard. A fictional archive that could easily have been real, it stands in for women’s lives and stories that surely existed but were never documented. Serving as homage, fantasy, and corrective, this speculative archive challenges the incompleteness of what gets passed down as archive and history.

Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye, The Fae Richards Photo Archive, San Francisoco, 1996

The photographs were created in collaboration with Dunye as props for her 1996 film The Watermelon Woman. In the film, Dunye plays a character (also called Cheryl) who works in a video store and is trying to make a film about stereotypical roles for black women in 1930s and ’40s Hollywood. Her research leads her to track down an actress identified in a film’s credits only as “the watermelon woman,” who she discovers was also a singer in butch-femme bars in Philadelphia. Cheryl hunts through the CLIT lesbian archive (presumably a reference to the real-life Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn) and finds a trove of photographs of the actress, who turns out to be named Fae Richards.

This book plays with fact and fiction, artifice and authenticity. It echoes the form of a found notebook, with a handwritten label, a pulp cardboard cover, Fae Richards’s “autograph” on the frontispiece, aged and distressed photographs, and captions typed on an old-fashioned typewriter. Although created to conjure up the golden age of Hollywood, Richards is actually a product of the 1990s and its shifting attitudes about and within the gay community. In the wake of a decade of AIDS activism (Leonard herself was an active member of ACT UP), mainstream acceptance of gay rights was beginning to emerge in the U.S. This growing recognition was attended with some ambivalence: would normalization leech queerness of its radical, subversive potential? Against this backdrop, there was a resurgence of interest in pre-Stonewall-era gay life and illicit bar culture, butch-femme dynamics, and the thrill of an outlaw, underground community—countered by a recognition that the price of that outsider status was repression.

For viewers who have rarely seen themselves represented in official histories or mainstream entertainment, or are represented only as caricatures, Richards’s archive stands in for the lives we know existed but weren’t recorded. Who cares if it is technically fictional? It retroactively materializes a history and a lineage for us that we want and need.

KRISTEN LUBBEN is a curator and the recently appointed executive director of the Magnum Foundation.

The post Kristen Lubben on Zoe Leonard and Cheryl Dunye The Fae Richards Photo Archive appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 13, 2016

In Experimental Photography, Is There Ever a Decisive Moment?

In Aperture’s new exhibition Summer Open: Photography is Magic, curator Charlotte Cotton highlights the work of contemporary artists who employ a diverse scope of magical approaches to photography. The practices and techniques of the artists vary immensely. While some find their images in everyday life, others create intricate sets and stages, while still others rely primarily on digital techniques. Ahead of the exhibition, Aperture asked a group of the participating artists: “In experimental photography, is there ever a decisive moment?” Here’s what they have to say.

Anastasia Samoylova, Desert Mirages, 2014 © the artist

“The ‘decisive moment’ is a beautiful fiction: the idea that a single decision of the artist is responsible for the creation of the picture. Each set that I photograph takes hours of pre-conceptualization and physical construction, yet is captured in a fraction of second—right before everything falls apart.” —Anastasia Samoylova

Tabitha Soren, Untitled 023224, 2016 © the artist

“When I’m making marks on the fragile photo paper, I try to approach the point where it seems reckless to keep going, or until the paper breaks. That is the decisive moment for me—and it is very often where the piece begins. The images so far have turned out much more serene, even though I often use pellet guns, razors, and bow and arrows to allow for the possibility of accident to influence the piece. And yet, the violence and anger often gives way, in the end, to tranquility.” —Tabitha Soren

Adam Ekberg, Eclipse, 2012 © the artist

“If we’re talking about moments, I see myself as generating them rather than merely recording them. In my practice, there’s always a moment where everything comes together for the camera, but ‘decisive moment’ is a loaded term and a bit incongruous with my practice of planning my images. First, I begin with sketches of improbable actions or phenomena. Recently, I wanted to generate an eclipse with a commonplace object. On my bicycle, I passed a fruit stand and a prominently displayed pineapple caught my eye as the perfect item to obscure the sun. I set up my camera in my front yard and—to the amusement of my neighbors—began throwing pineapples in the air.” —Adam Ekberg

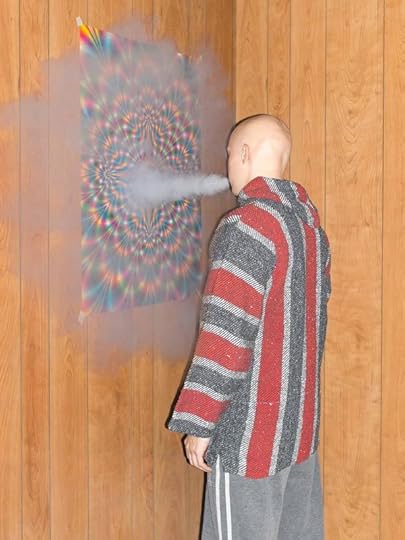

Bubi Canal, Beautiful Mystery, 2015 © the artist

“For me, the process of taking a photo is like going through a forest looking for the unknown . . . standing by a river and listening. Something unexpected and magical happens—that is my decisive moment.” —Bubi Canal

Joseph Desler Costa, Layered Guitars, 2015 © the artist

“The ‘decisive moment’ has always been a slippery concept for me, a term that can be loosely applied to any and every image. In my process, and as I compose, frame, and reframe, there are multiple ‘decisive moments’ happening as current imaging processes allow us infinite possibilities. I try to make pictures and compositions of moments and material the eye doesn’t see, but still recognizes, reflecting how much of our contemporary lives are virtual, rather than physical.” —Joseph Desler Costa

Chris Maggio, Untitled, 2014 © the artist

“Just because a photograph is alternative in its technique, doesn’t mean that it is absent of that fleeting instant where one’s creativity, worldview, and technological skills coalesce. As the photographic field continues to evolve, the meaning of Cartier-Bresson’s celebrated concept has only expanded. Now, whenever it strikes, that moment is when a concept just ‘clicks’—be it with the click of your shutter, the clicks of your mouse in Photoshop, or simply when the idea for a composition suddenly comes into focus. Whether you’re planning an image for months or composing it in 1/100th of a second, there’s always that personal, inexplicable, and sudden energy that informs you that this is it.” —Chris Maggio

Megan Paetzhold, Amblyopia triptych, 2015 © the artist

“I’m skeptical about the division between ‘experimental’ and ‘traditional’ photography. Experimentation has always been stitched into the fabric of photography’s nature. The ‘decisive moment’ is typified by waiting—waiting for reality to align perfectly in front of the lense—a mixture of luck, happenstance, and the photographer’s intuition. In my work, the definition of the ‘reality’ being represented may be fluid, but the structure of the Decisive Moment remains; luck, happenstance, and intuition are all essential to my image making process.” —Megan Paetzhold

Deepanjan Mukhopadhyay, Interview, 2015 © the artist

“For a lot of contemporary photographers, including me, who experiment with the magical, that is to say, the deceiving properties of the photographic medium in our studios, the ‘decisive moment’ takes a backseat. However, it does linger in the studio and works its magic from time to time, less in the form of aesthetics and more in the form of luck, inspiration, and breakthroughs.” —Deepanjan Mukhopadhyay

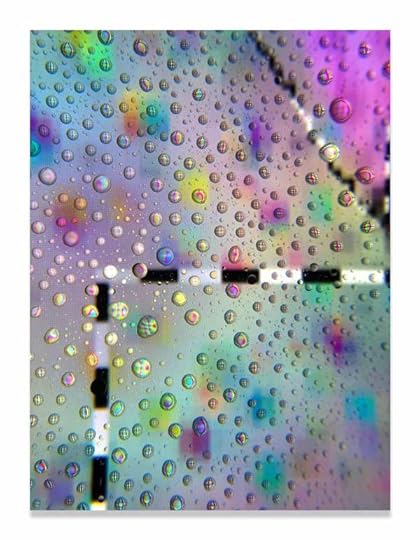

Valerie Green, IMG6411, 2016 © the artist

“The ‘decisive moment’ in my work expands beyond Bresson’s notion of the ‘creative fraction of a second.’ I utilize both chance and choice to capture not only a singular moment, but a multitude of moments that are layered on top of each other.” —Valerie Green

Hyounsang Yoo, how to be invisible, 2015 © the artist

“I think artists and photographers interpret their own way to make a decisive moment. My work is often heavily manipulated, staged, and stripped of contextual information. I do not take a photographs; I make them. However, I work on them until I am satisfied, which is my own decisive moment.” —Hyounsang Yoo

Radek Brousil, Hands Clasped, 2015 © the artist

“Experimental photography is horizonless. It allows me to escape and explore undetected. Photography in general went through a certain revolution of the medium during last decade. From this cataclysm it became a medium that can be anything we fantasize.” —

Irene Mamiye, No Use in Crying 3939, 2015 © the artist

“While twentieth century artists like Henri Cartier-Bresson were concerned with formalist ideals, twenty-first century artists are ‘on the run,’ seizing tools as they become available. The shift from an analogue to a digital ‘darkroom’ has extended the decisive moment so that it can be frozen in time in an ever-growing field of discovery. This fearless spirit is afforded to us in part by the impermanent nature of our decisions, which can be undone in a click, confounding photographers with a myriad of possible ‘decisive moments.’” —Irene Mamiye

Amelia Bauer, A Ghost (Portrait), 2015 © the artist

“I’ve never thought of my image making as capturing a moment, but rather each image as a stop on a continuous journey through various lines of thought. There are decisive moments along these paths during which certain ideas synthesize, and the way forward becomes crystalized. These ‘aha’ moments happen both before I embark on a new series in the moment, when I conceptualize the next body of work, and when I’m playing with images I’ve already taken, unsure of where they will end up. Henri Cartier-Bresson believed that photography is ‘an immediate reaction,’ whereas ‘drawing is a meditation.’ It is my belief that photography as it functions today rejects this premise and exists with fluidity between these two opposing characterizations.” —Amelia Bauer

![Oskin_000656_844843_003848_3271[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1468498771i/19714081._SY540_.jpg)

Ryan Oskin, Stacked Glass, 2015 © the artist

“Even at its most experimental, photography always has a ‘decisive moment.’ The original ‘decisive moment’ was the clicking of the shutter, but could also be the moment you expose pigment to a substrate, or the moment you think and act on a new idea. In my work, I try to prolong the process after photographic capture to intervene in my own imagery. By moving beyond a straight photograph, I question the possibilities of the image’s materiality and expand on our collective perception of what a photograph is and can be today.” —Ryan Oskin

The Aperture Summer Open: Photography Is Magic is on view at the Aperture Gallery through August 11, 2016.

The post In Experimental Photography, Is There Ever a Decisive Moment? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 12, 2016

The Camera Selects the Man

Gerard Petrus Fieret was obsessed with women’s legs, street scenes, and pigeons. In a new retrospective, the Dutch photographer’s subversive images reveal the libertine atmosphere of 1960s Europe.

By Wilco Versteeg

Gerard P. Fieret, Untitled, 1965–75 © Estate of Gerard Petrus Fieret and courtesy Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Dutch postwar avant-garde art—whether it was poetry, painting, or photography—traveled a familiar trajectory: misunderstanding from pre-war critics and audiences was typically followed by rapid acceptance into established institutional circles. Artists born in the 1920s, such as Karel Appel, Armando, and Jan Wolkers, were influenced in many cases by personal experiences in German labor camps, and the Holocaust was pivotal in their work. A telling example is Lucebert, the self-proclaimed Emperor of Movement in the 1950s, whose verses were described as the SS marching into Dutch poetry.

Enter Gerald Petrus Fieret. Born in 1924, he too was interned in a German labor camp and participated in many of the new forms and methods of expression introduced by his peers. However, the war is surprisingly absent from his work, setting him apart from his generation of Dutch artists. Insistently experimental, personal, and documentary, most of his work was taken in his basement or in other confined spaces. His portraits and self-portraits show a changing society without showing much of the outside world.

Gerard P. Fieret, Untitled, 1965–75 © Estate of Gerard Petrus Fieret and courtesy Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Fieret gained little renown in his lifetime. He only came to photography in 1965, at the age of 45, and worked for about ten years, after which he returned to draughts work and poetry. (He died in 2009, paranoid and bitter, in a dilapidated room surrounded by his pet pigeons.) The first international exhibition of Fieret’s work, currently on view at LE BAL in Paris, is well deserved attention for this radical outsider. The exhibition is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalog, published by LE BAL and Éditions Xavier Barral, with essays by Wim van Sinderen, Violette Gillet, Francesco Zanot, Hripsimé Visser. The catalog, especially where it touches on Fieret’s Dutch reception, provides essential context in drawing further international attention to his work.

Fieret did not refer to himself as a photographer but rather as a fotographicus—a photographic draughtsman; for him, each print is unique and bears traces of the hand of the master. His photos show a remarkable intimacy in their portrayal of his unpaid models. But those moments are only the start of Fieret’s practice: he also experimented with developing, enlarging, printing (and sometimes re-photographing). His prints are often scratched, dusty, or otherwise touched by the destructive working of time or sheer recklessness. Most of his prints also bear the mark of paranoia—he stamped his work “Photo and Copyright G.P. Fieret,” in addition to his extraordinary signature, to make sure that no one could claim authorship.

Gerard P. Fieret, Untitled, 1965–75 © Estate of Gerard Petrus Fieret and courtesy Leiden University Libraries Collection

Fieret plays a serious, almost psychotic game in his self-portraits. A short 1971 documentary by Jacques Meijer, screened in the exhibition, states that Fieret was on a quest for himself in his work, but that “the camera selects a different man” each time the shutter is pressed. Indeed, Fieret is often on the verge of disappearing in even his most self-reflexive works. In one self-portrait with a nude, for example, Fieret carelessly obscures himself in the final print, effacing the intimacy that created the image in the first place. In other self-portraits, Fieret is expressive, but seems to rely on the camera for his very existence.

Another important theme is his portraits of women in the nude, which, for the time, exhibit a rare equality between photographer and model. Fieret’s struggle with his own sexual identity is manifest in these images. While he was fascinated by female legs, most of the legs in his photos are crossed or closed. The possibility of a sexual relationship is precluded, but the women’s erotic presence is not lost. Too artful to be pornographic, the snapshots show a concern for the sexual expression of women—a counter-image of sexuality in a society in which liberation was quickly becoming equated with exploitation.

While he does not address political and societal upheavals as a documentarian, Fieret’s photographs reflect the evolving social attitudes of the sexual revolution in the 1960s: sex as a possibility instead of a problem; the body as image of pleasure; and the freedom to express sexuality in art and in life. For a Calvinistic country such as The Netherlands, this is no small feat, even though Fieret appears, at times, reluctant to fully explore such newfound liberation. Fieret’s works will baffle audiences: he created, on his own, a visual language that was out of step with his time. Now, thanks to LE BAL, it can be appreciated for what it is: the work of a great voice in Dutch and European photography.

Wilco Versteeg is a PhD candidate at Université Paris Diderot.

Gerard Petrus Fieret is on view at LE BAL, Paris, through August 28, 2016.

The post The Camera Selects the Man appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

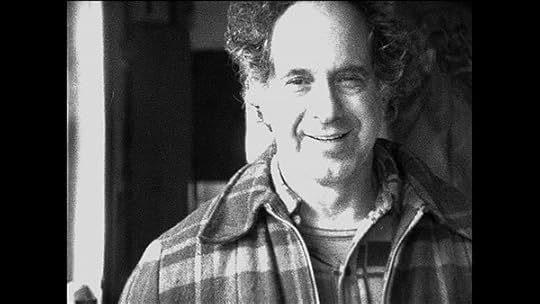

A New Documentary Turns the Lens on Robert Frank

In Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, Laura Israel delivers an intimate portrait of the artist who revolutionized photography with his trenchant 1958 book The Americans. Israel, who has worked with Frank since the 1990s, recently spoke with Aperture about the making of Don’t Blink, which opens this week at Film Forum in New York.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph: Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Nicole Maturo: You’ve worked with Robert Frank on his films for a long time. How did you first meet him?

Laura Israel: It was through Run (1989), a music video for New Order. I used to edit a lot of music videos and a friend of mine who worked for Factory Records and New Order told me on this one I’d be working with Robert Frank. I remember the first day Robert came to my studio. At that time, we used to work in tapes, which you had to rewind and fast forward. It got really boring. So we used to make these little selects. I turned around to Robert and I said, “Once we make these selects, are we going to want to go back and change our minds? I’ll set up for that.” And he said, “No. Once we make a choice, it’s fate. First thought, best thought. We don’t go back. We only move forward.” And I remember thinking, This is my kind of director. That’s one of the things that’s so great about working with Robert: he’s so decisive. I admire that.

Also, I’m a big postcard collector, so after we worked together for the first time, whenever I got a good postcard, I would walk past his house on my way to my studio and I’d just throw a little postcard and a note in the door. And I think, in the end, that cemented our friendship.

Still from Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Frank is a postcard collector, too.

Israel: I didn’t even know that he collected postcards. I had some really good ones that I had been saving up. There was one in particular of a flamingo, beautifully hand painted. And that was one of the first ones that I put in his door. A few years later he came out with a book called Flamingo (1997)—it wasn’t based on the postcard, it was based on this photograph he had taken of a flamingo in a bottle. But it was little things like that that were kind of like fate, for both of us.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Frank is notoriously anti-fame. Did this make it difficult for you during the making of the film? How did you convince him to go in front of the camera?

Israel: It was a little odd for me because I’m so used to sitting next to him, rather than sitting in front of him and putting a camera in his face. But I also told him it would be a really small crew. We kept the crew down to three people, which was really difficult under those circumstances, but we thought it was important because we were going into his house, going into his life. It was important we that we tread lightly. And sometimes we went there and we said, Oh, you want to take a break, and we all had tea and cookies and hung out. And I found out later on that that’s how Robert got the Rolling Stones to agree to Cocksucker Blues (1979): he said he would only bring one other person to shoot. The other thing that I did was I invited friends of his, so it was more of a conversation. So Robert and his friend Ed Lachman both look at the book together, or we go out on these photo trips so it’s more of an activity. And it was more fun that way. I hope it comes out in the film how much fun we had shooting the film.

But very early on we found that he didn’t take direction very well. He kept me on my toes, which made the shooting more organic. It was also a little nerve-racking to have three different plans for every day we shot. But I know why he did it. He did it so that it didn’t become one of those really staged interviews.

Still from Robert Frank’s film About Me: A Musical, 1971

Maturo: I was curious to see how the film handled the tragic loss of Frank’s children, Andrea and Pablo. When did it become necessary to include these details so that we can understand Robert Frank the man vs. Robert Frank the artist? Is there even such a divide?

Israel: One of the biggest strengths of Robert’s work, and people have remarked about it, is his embrace of creative work as the antidote to personal tragedy. I hope that comes off in Don’t Blink. That’s one thing that I’ve really learned from Robert: your life and your work can go together, and you can actually use your work to really help you through a lot periods in your life that are difficult. I think that’s what he was trying to say, after Andrea died, with Keep Busy (1975); that was the theme of that period of his life. He had to keep moving and keep working.

That was the hardest thing in the film to edit. I ended up using Robert expressing it through his work quite a bit because those are his innermost feelings, which are more poignant than someone sticking a camera in his face and asking, “How do you feel about this horrible thing that happened to you?” His work really expresses it much better.

When it comes including him directly talking about it, less is more. In a documentary, the most poignant thing that someone says is good to include. It hits me every time I hear Frank say, “Maybe to be in Mabou, it was more difficult to deal with Andrea’s death.” I know it’s this cold, lonely place and he’s in the middle of nowhere and going through that loss. It conjures up a feeling in me that is probably similar to the feeling that Robert had. I hope that I could do that with the film—make people feel what Robert was feeling. Not just have them hear what he was saying, but also to feel it in the film through the visuals. Which is what he tries to do with his photographs—to really convey what he’s feeling through his photographs not just portray what he’s seeing. I think that’s more in line with the feeling of Robert.

Detail from contact sheet, 1971. Photographs by Sid Kaplan

Maturo: Throughout your film, the use of jump-cuts is reminiscent of Frank’s filmography. Was there a particular Frank film that inspired your editing?

Israel: My editor, Alex Bingham, and I envisioned the film in three parts, and it had to do with Robert’s work, so I tried to have the film change. There was the more formal work, The Americans, black-and-white, very beautifully composed, very rough around the edges but also kind of lush. Then there was the period where he started to get into filmmaking but it was still film, it wasn’t video, and he also started scratching and painting words on photos and negatives. From the 1980s onward, he started shooting with polaroid, Super 8, and video cameras more often. The work sometimes resembled a personal diary, especially when he used his own voice to narrate. So I tried to see each part a little bit differently within the editing.

I had worked with Robert on The Present (1996). We had talked about editing the film as if you’re rummaging through drawers, looking for a photograph, or looking through old correspondence and memories. And you’re looking for something, but along the way you find other things that you’re looking through, so it’s seemingly random, but actually is has order. That’s what I was thinking about as the motivation of Don’t Blink as well. The other thing I tried to convey, which is true to Robert’s spirit, is the feeling of traveling along a road and then take a little detour but return to the road again, only to detour again and then go back. Nobody gets completely lost because of the signposts, yet you can take a little detour. That also was my motivation for the editing.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Many photography students are surprised when they learn that Frank gave up photography for a time in order to devote himself to film.

Israel: That was hard to portray in the film, but I understand why he did it because if you look at the sequencing of his work, as in the series From the Bus (1958), you can see he was practically shooting film, everything was movement, everything was this caught moment that was just about to move—you got this feeling he was going to move into film. That would be the natural next step. But also he has said, “I love difficulties and difficulties love me.” I think it was more difficult for him to pursue film. There’s one part of the film, it’s black-and-white footage from Frank at a conference at New York University in 1971. People were really giving him a hard time because he wanted to show his films, and they wanted to talk about The Americans. And he got really visibly annoyed with them. He said, “At least I’m trying to do something new and different, I’m not resting on my laurels. I’m not doing the same thing over and over again, I’m looking for something new.” I really respond to that, and I really respect that about him.

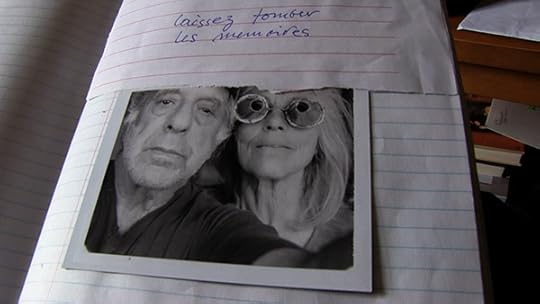

Robert Frank’s photograph of himself and wife, June Leaf, from Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: What’s the essential film that every Frank fan should see, a primer for his cinematic style?

Israel: Well it has to be Pull My Daisy (1959), although I have a certain love for the documentary shorts because they have a personal quality about them that I really like. The diaristic quality about the videos—it’s something that I really respond to. I can’t pick one, but I can say Conversations in Vermont (1969) is also a film that I really love; Me and My Brother (1969), I think, was really the first music video ever made. Pieces of that are so groundbreaking. I started out working in music videos and I saw that film and I was like, Wow, those are techniques we thought we were discovering and Robert had already done them. Like running the film back in the camera, there’s some amazing stuff in that film, and there’s some amazing stuff in Pull My Daisy as well, as far as music videos go.

Robert Frank in Don’t Blink–Robert Frank, 2015, directed by Laura Israel. Photograph by Lisa Rinzler. Courtesy Grasshopper Film

Maturo: Do you have any future projects scheduled with Frank?

Israel: I don’t know. I’m going to visit him this summer, or it might be early fall. So, we’ll see. To be continued. I don’t know if it will be a film, but it might be a little something. I would work with Robert on anything.

Nicole Maturo is an executive assistant at the Aperture Foundation.

Robert Frank–Don’t Blink will be screened beginning July 13, 2016 at Film Forum in New York.

The post A New Documentary Turns the Lens on Robert Frank appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 11, 2016

The PhotoBook and the Archive

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

In what ways is the photobook a useful framing device for archival projects? If we restrict ourselves merely to archives of photographs, the sequential succession of the book seems inherently opposed to the archive’s static taxonomy of images. An archive of categories presents its user with a map of instances, without a narrative trajectory, yet the book form implicitly suggests—and inevitably produces—a sense of progression from beginning to end. How are these opposing dynamics reconciled and transformed when the archive is rendered in the form of the photobook?

It might be that the photobook, as a physical object, reenacts the processes of interpretation implicit in the organization of the archive itself, reflecting an instinct common to the breadth of photographic practice: a need to order, and thus make sense of the changing world. Looked at this way, the photobook functions as a means to give us some purchase on what Gerry Badger describes as photography’s “endless image bank,” allowing us to revisit and rearrange history in the face of modern life’s constant flux.

The photograph’s affinity with everything from criminology to space exploration makes editors and archivists of the countless millions of us who use it. Photographs themselves have become emblematic of the flux of modern life, in both their physical and digital form. In attics and airport databases; in albums, auction houses, and super-cooled server arrays; in corporate and governmental institutions; at black sites and on the deep web, they are continually aggregated, appropriated, arranged, and abandoned at an inconceivable pace.

If it is typical of photographs to accumulate, their circulation and transfor-mation are no less intrinsic to their nature. They migrate from the low resolution of the Internet to newsprint halftone to 42-by-78-inch gelatin-silver prints; they enter new systems of collection and revaluation, eloping from the pages of pulp novels to memory sticks to the uncoated surfaces of photobooks, only to be archived all over again. The single photograph, or the original file, eventually lives on in a multiplicity of forms. The volume of photographic images in the world proves, as Adrian Searle has written, “just how much we like to look, that looking drives us where it will, that we keep on looking.” Thus, it is through the considered articulation of the archival photobook that we are able to look again at our history of seeing the world.

In this issue, various artists, publishers, critics, and art historians examine archival photobooks that span both the history and contemporary shape of this resurgent form of photographic activity. While limitations of space make a full accounting of this history impractical here, we are delighted to have been able to include contributions from seminal figures and relatively new practitioners, as well as show a meaningful fraction of the wide range of books produced in this vein. From works of collage to re-photography, from typological strategies to cinematic modes of appropriation, these projects celebrate the plasticity of the photographic image, and the perennially open-ended nature of those meanings, which can be reconstructed from the orderly depths of the archive itself.

It is through the considered articulation of the archival photobook that we are able to look again at our history of seeing the world.

Giorgio Agamben writes in his essay “What Is the Contemporary?” that “the entry point to the present necessarily takes the form of an archaeology; an archaeology that does not, however, regress to a historical past, but that returns to that part within the present that we are absolutely incapable of living.” The resurgence of archival projects in the photobook suggests an eagerness on the part of many artists to explore the intersections, or indeed presences, of the past in the present tense. Whether these works take the form of “an allegorizing of the past by the present, or . . . an allegorizing of the present by a past it now claims as its own,” as David Campany has written, the works shown in this issue demonstrate that the photobook is an extraordinarily adaptable form with which to reexamine the temporality of the photographic image, in all its poetic strangeness and fascinating complexity. They show us that photographs have a multiplicity of irreducibly social lives, that our histories are malleable, and that those histories might be shored up against forgetting through the patient labor of rearticulating experience in the form of the photographic book.

STANLEY WOLUKAU-WANAMBWA, a photographer,

writer, and editor of The Great Leap Sideways, is a faculty member in the photography department at Purchase College, SUNY. www.thegreatleapsideways.com

The post The PhotoBook and the Archive appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Marco Breuer on Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s Evidence

In 1977, Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan self-published Evidence (the imprint, Clatworthy Colorvues, was a joke: Mandel found that name on the back of a postcard). To better understand the context of this publication, I met with the wonderful Kelly Sultan, Larry’s widow. We went through boxes of prints from Larry’s archive. I called Mandel with a long list of questions. He mentioned a number of interesting influences—E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits (1970), John Szarkowski’s From the Picture Press (1973), and Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip (1973), among others.

Starting at a local NASA office in California, Mandel and Sultan went to over one hundred archives across the country. They worked from opposite ends of the files and met in the middle. At the end of the day, they handed over a list of numbers. A couple of weeks later, they would get 8-by-10 prints in the mail.

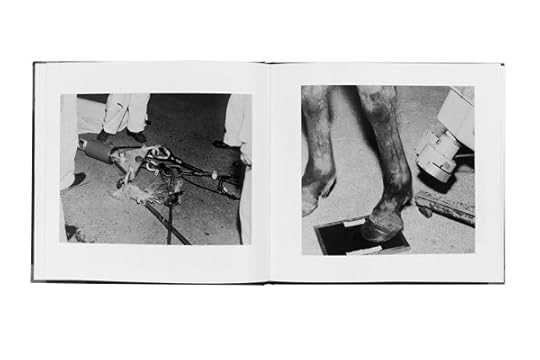

Looking at the many outtakes in Sultan’s archive now, I began to understand why many standout images didn’t make the final cut. They were clearly chosen for their visual strength, but in the end they turned out to be too strong. Take the images of animal experiments: they are powerful but hard to look at, and, most problematically, they are too easy to connect to.

As the project progressed, Mandel and Sultan honed in on what it was they were looking for. They had an ongoing conversation about “hot” and “cold” images, about juxtaposition and sequencing, about which images can live next to each other without pushing too much onto the others. They were looking for photographs dealing with a particular paradox: you should be able to figure out what the image is about, but you can’t. It does not reveal what it should. Mandel and Sultan were able to find this singular quality again and again.

For me, the images in the book have always produced a powerful sensation: I see, but I do not comprehend. Looking through the book again this week made me think about how we process photographs. I picture the inside of my brain as a library card catalogue. Most images I encounter during the course of the day are swiftly filed away in the appropriate categories. Unclassifiable images like the ones in Evidence, however, create a strange delay: they seem to float in your head, stay with you longer.

But something is different now. My relationship to one of the images in the book has changed: a horse’s hoof being placed on a portable x-ray machine by a veterinarian. Not too long ago, I stood next to a vet during this procedure. It was an emotionally charged event—it was my horse. I now know too much about this scenario to appreciate the image for its other qualities. The sensation of encountering this newly familiar image is visceral and peculiar, a soap bubble bursting in front of my eyes.

I do not feel that I have gained something. Instead, I seem to have actually lost something.

MARCO BREUER is a German photographer and the inaugural recipient of this year’s Larry Sultan Photography Award. He is the author of Marco Breuer: Co*lor (Black Dog, 2015) and Early Recordings

(Aperture, 2005).

The post Marco Breuer on Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s Evidence appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 8, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: The People’s Justice Murals

On the streets of New York, murals strike back against police brutality.

By Emily Raboteau

Nelson Rivas, aka Cekis, Washington Heights, Upper Manhattan, Wadsworth Avenue and 174th Street, 2009. “If you are detained or arrested by a police officer, demand to speak with an attorney and don’t tell them anything until an attorney is present.” “Ud. no tiene que estar de acuerdo con un chequeo de si mismo, su carro o su casa. No trate fisicamente de parar la policia. Solo diga que ud. no da permiso para el chequeo. Tienes el derecho de no aceptarlo.” “Ud. tiene el derecho de observar y filmar actividades policiales.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

I pass this mural next to a laundromat every day on the way to my kids’ daycare in Washington Heights. It pops out from the gritty gray buildings surrounding it—a vision of blues. The mural is hard to ignore. Huge letters trumpet “Know Your Rights!” followed by basic information about what to do if arrested or stopped and frisked. Because I so appreciated the integrity of that message, and the beauty of the mural in my neighborhood, I took a picture of it. After that I set out to find others. There are currently ten (and counting) “Know Your Rights!” murals spread across four boroughs in New York City, typically in poor neighborhoods plagued by police misconduct. In the summer of 2015, I traveled to Harlem, Bushwick, Long Island City, Bedford Stuyvesant, and Hunt’s Point, to photograph them.

Dasic Fernández, Know Your Rights, Bushwick, Brooklyn, Irving Avenue and Gates Avenue, 2011. “If you are harassed by police, write down the officer’s badge number, name, and/or other identifying information. Get medical attention if you need it and take pictures of any injuries.” “All students have the right to attend school in a safe, secure, non-threatening and respectful learning environment in which they are free from harassment.” “No tenant can be evicted from their apartment without being taken to housing court.” “Si ud. es detenido o arrestado por un policia, pida hablar con un abogado immediatamente. No diga nada hasta tiene un abogado presente.” “Owners are required by law to keep their buildings safe, well maintained and in good repair. If not, call 911.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

The murals were commissioned by a coalition of grassroots organizations called People’s Justice for Community Control and Police Accountability and financed by the Center for Constitutional Rights. Yul-san Liem, who works for the Justice Committee, explained to me that the murals are part of a broader project to counteract police brutality: “Our original goal was to highlight the systemic nature of police violence in communities of color.” People’s Justice formed in 2007 in the wake of the New York Police Department killing of Sean Bell, an unarmed black man, the day before his wedding. “It wasn’t an isolated incident,” Liem lamented, recalling the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo, who was also an unarmed black man, and who was shot forty-one times by police, as well as the assault of Abner Louima, sodomized by police with a broomstick in 1997, among others. In response to this pattern of misconduct, Liem said, “We’ve taken a proactive approach to empowerment that includes organizing neighborhood-based Cop Watch teams and outreach that uses public arts as a means of education.”

Trust Your Struggle (collective), Trust Your Struggle, Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, Marcus Garvey Boulevard and MacDonough Street, 2010. “Justice or Just Us.” “LOVE/HATE.” “Stay calm and in control. Don’t get into an argument. Remember officer’s badge and patrol car number. Don’t resist, even if you believe you’re innocent. You don’t have to consent to be searched. Try to find a witness & get their name & contact. Anything you say can be used against you. Know Your Rights. Trust Your Struggle. Spread love. It’s the Brooklyn way. Didn’t pass the bar, but know a little bit; enough that you won’t illegally search N.Y.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

As with protests organized via the Black Lives Matter movement since 2013, these works of public art convey how people on the street are responding to police brutality now. The deaths in recent years of Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile, and Alton Sterling (to name but a few) have shown us the necessity of art like this, which attempts to save actual lives at risk. When I remarked to Liem that the murals struck me as an act of love for and by the people living in the neighborhoods in which they exist, she agreed. “Visual art communicates differently than the written or spoken word,” Liem told me. “By creating these murals, we seek to bring important information directly to the streets where it’s needed the most, and in a way that’s memorable and visually striking.”

Dasic Fernández, Know Your Rights, Long Island City, Queens, Thirty-fifth Avenue and Twelfth Street, 2012. “If you are HARRASSED by police, write down the officer BADGE number, name and/or other identifying information. Take PICTURES of any INJURIES.” “Ud no tiene que estar de aquerdo con un chequeo de si mismo, su carro o su casa. No pare fisicamente a la policia. Diga que ud. no da permiso para el chequeo.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

Indeed, the murals are huge, colorful, and graphic. In each photo, I captured a local resident in the frame, walking past the mural to give a sense of its scale. I chose to respect that person’s anonymity in case they didn’t wish to be photographed by a stranger. Their face may be hidden by their phone, or turned toward the mural, or silhouetted by the angle of light. Sometimes it took hours to get the right shot; hundreds of photos for the one photo that worked.

Dasic Fernández, Know Your Rights, Hunts Point, Bronx, Barretto Street and Garrison Avenue, 2012. “You have the right to watch & film police activities.” “If you are detained or arrested by a police officer, demand to speak with an attorney and don’t say anything until attorney is present.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

I shot these images with my iPhone 5s. Many of the subjects in the murals themselves are depicted shooting with their phones, too. The muralists meant to convey that we have the right to record police activity. These days our phones are crucial weapons in the fight for social justice. Over the course of this project, I was struck by how many of the murals figure cell phone technology as an agent of social change. When a bystander captured Rodney King being beaten by LAPD officers, prompting the Los Angeles Riots in 1992, that kind of footage was rare. People didn’t walk around with video cameras in their pockets. But as the footage of Michael Brown—who was murdered by officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, and his body left for hours in the street—showed us in 2014, instant and widespread exposure via social media has the power to initiate nationwide protest. While it remains true that the police may still brutalize and kill us with impunity in this country, it is also true that we now have the ability to lift our cell phone cameras and shoot back.

Sophia Dawson, Know Your Rights, Harlem, Upper Manhattan, 138th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, 2013. “Write down the officer’s badge #, name, and/or other identifying info.” “Get medical attention if needed and take pictures of injuries.” “You don’t have to answer any questions from police. When they approach, say, ‘Am I being detained, or am I free to go?’ If they detain you, stay silent + demand a lawyer. A frisk is only a pat down. If police try to do more than that say loudly, ‘I do not consent to this search.’” “You have the right to observe, photograph, record, and film police activity.” Photograph © Emily Raboteau

Emily Raboteau is a writer and street photographer living in uptown Manhattan. Her books include The Professor’s Daughter (2006) and Searching for Zion (2014), and her photographs have appeared in Apogee, Callaloo, Kweli, Buzzfeed, and Aster(ix). These pictures are part of a photo essay that will appear in The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks Out About Race in America, forthcoming in August 2016. They were documented by the photographer with the permission of People’s Justice for Community Control and Police Accountability.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: The People’s Justice Murals appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 6, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Nothing Personal

At the height of the civil rights movement, Richard Avedon and James Baldwin collaborated on a controversial photobook. But, was Nothing Personal a luxury object or a ruthless indictment of American culture?

By Brian Wallis

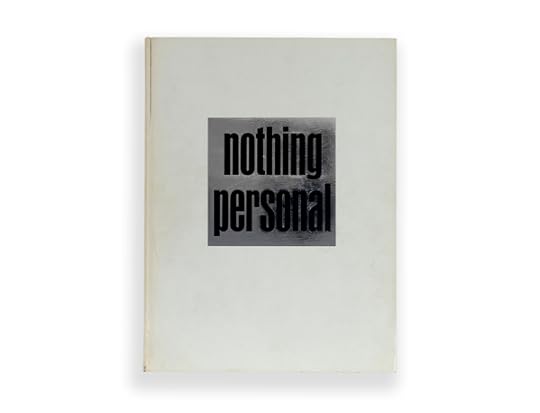

Cover of Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Nothing Personal (New York: Atheneum, 1964)

When it was first published in 1964, just months after passage of the Civil Rights Act, Nothing Personal promised to be a major statement on what was then called “the Negro problem.” Combining the fiery prose of James Baldwin, the nation’s most celebrated African American author, with the electric photographs of Richard Avedon, America’s leading fashion photographer, Nothing Personal was a Mad Men–era, pop-culture phenomenon. The book’s elegant design, by Marvin Israel, was meant to underscore its importance: Nothing Personal is an oversize, slipcased white album that alternates four brief texts with four thematic sections of lush gravure photographs. And yet the hot topic of the day, civil rights, is barely mentioned.

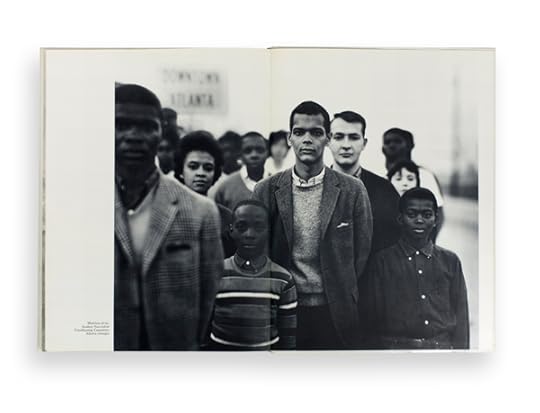

Richard Avedon, Julian Bond and members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Atlanta, Georgia, March 23, 1963. Spread from Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Nothing Personal (New York: Atheneum, 1964)

Avedon described the photographs in Nothing Personal as “some of my very best work,” and they include, among other things, his unforgettable portraits of a naked Allen Ginsberg, a dejected Marilyn Monroe, and an unflinching William Casby (born into slavery one hundred years earlier), often provocatively juxtaposed with one another. But the real surprise is Baldwin’s largely overlooked texts, an incisive series of short bursts that have seemingly little to do with Avedon’s photographs. Instead, Baldwin writes deeply personal ruminations and perspectives on the American psyche: its penchant for hollow myths and easy escapism; its aggravated assault on strangers and difference; its cultivated loneliness and constant self-renewal; its unbelievable ignorance and passion for violence; its suicide-inducing despair. These reflections, though coming on the heels of President Kennedy’s assassination and preceding Baldwin’s own exile from America, seem remarkably prescient today and have renewed urgency as we face a new plague of racial and sexual violence.

Fifty years on, it is easy to see why Nothing Personal was in 1964 as an elitist misfire, especially as compared to earlier politically charged photographic examinations of African American injustice such as Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941), Ernest Withers’s Emmett Till pamphlet (1955), or Danny Lyon’s The Movement (1964). But Nothing Personal aimed to go beyond stark observations of documentary photography and prose to experiment with a new notion of equality, and to reach for a more abstract, humanistic, or even philosophical take on the “unspeakable loneliness,” as articulated by Baldwin, of an increasingly depersonalized America.

Brian Wallis is a curator based in New York.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Nothing Personal appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

July 5, 2016

5 Photography Exhibitions to See This Summer

From dream states to Russian decadence, here are this summer’s must-see photography exhibitions in New York.

By Genevieve Allison

Sasha Rudensky, Purple Suit, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Sasha Wolf Gallery

Sasha Rudensky: Tinsel and Blue

Sasha Wolf Gallery, 70 Orchard Street, New York

Through July 16, 2016

Since 2009, the Russian-born photographer Sasha Rudensky, who immigrated to the United States as a child, has traveled to Russia and the Ukraine to explore post-Soviet culture. In a stylized, quasi-documentary mode, Rudensky isolates figures amidst landscapes or settings meant to signify the effects of materialism. The predominance of the color blue unifies the work, which includes images of an exotic dancer (Snow Queen, 2014), a businessman being fitted in a suit (Purple Suit, 2014), and a lone grocery store squatting amongst dim residential towers (Night Market, 2010). Throughout these pictures, a cool, flinty atmosphere pervades scenes of bourgeois lifestyle in the former USSR, suggesting a pact between economic development and social cohesion defined largely by shiny surfaces. Indeed, the high gloss finish of the photographs—evocative of the work of Philip-Lorca diCorcia—amplifies the role mass media play in the construction of cultural narratives in postcommunist Russia and the figuration of stereotypes, commonly held in the West, of the country’s materialistic consumer class. In their sparseness, the scenes probe themes of isolation and distance. As with the outdated modernist high rises on a faded development sign (New Development, 2009), Rudensky ponders the anachronistically futuristic visions that still appear to frame the cultural landscape of post-communist Russia.

RongRong & inri, Tsumari Story No. 11-5, 2014. Courtesy the artists and Chambers Fine Art

Tsumari Story: RongRong & inri

Chambers Fine Art, 522 West 19th Street, New York

Through August 20, 2016

Most family photo albums confirm Eugène Atget’s lament that the snapshot works faster than we can think: not a whole lot of time, nor a significant amount of thought, goes into the creation of the images that illustrate a family’s life together. That is, of course, unless Mom and Dad are RongRong & inri. As husband and wife, the duo delicately explores their life as a couple and the growth of their family. In this joint exhibition, Chinese-born RongRong and Japanese-born inri present a series of black-and-white photographs created during the family’s extended stay in the rural area of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Transported from their home in Beijing to an empty, snow-covered landscape, they embraced a traditional Japanese lifestyle. There, we follow the couple’s response to an environment that seems at once new and timeless. Using elaborate darkroom processes such as hand tinting and layering effects, the photographers manipulate the texture of the images to imbue intimate subjects with an atmosphere of detachment. In a notably poetic image, Tsumari Story No. 7-1 (2012), mother and child look out over a distant valley of stepped fields. In other photographs, the family gazes through windows and doorways toward the elsewhere that they are now a part of. These quiet images are less interested in telling us a story than in articulating the silent language of bodies as they communicate together in a room, or as they exist alone in the landscape.

Paul Graham, Senami, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2011 © the artist and courtesy Pace and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Dream States: Contemporary Photographs and Video

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York

Through October 30, 2016

The entanglement between photography and the dream world, central to Surrealist experiments inaugurated nearly a century ago, is the deceptive subject in this exhibition of contemporary photographs and video drawn from the Met’s permanent collection. Jack Goldstein’s triptych The Pull (1976), suspends minuscule figures in an empty expanse of sky or water or some other unknown medium. Fred Tomaselli made the photogram Portrait of Laura (2015) by charting the eponymous subject’s astrological sign with pills on photosensitive paper. Such pieces, proposing to map states of interiority, stand in contrast to images by Robert Frank, Peter Hujar, Sophie Calle, Paul Graham, and Nan Goldin, among others, which dwell in a typology of sleeping figures. Darren Almond’s single channel digital video, Schwebebahn (1995) is a curious anomaly in the otherwise all-photography exhibition, but like some of the still images—such as Jim Shaw’s Dream Object (I Was Working on an Undersea Landscape) (1997)—the piece explores the world from its underside. Filmed on Super-8 on the Wuppertal Suspension Railway, Almond slowed, flipped, and reversed the footage to affect an inverted reality. Together, these works illustrate sensations of dreaming as defined by subconscious experience, as well as conscious fantasies of alternate states.

![S. J. Moodley, [Two women wearing party dresses], ca. 1978 Courtesy The Walther Collection](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1467839730i/19636822._SY540_.jpg)

S. J. Moodley, Two women wearing party dresses, ca. 1978. Courtesy The Walther Collection

Who I Am: Rediscovered Portraits from Apartheid South Africa

The Walther Collection Project Space, 526 West 26th Street, New York

Through September 3, 2016

In 1957, Singarum Jeevaruthnam “Kitty” Moodley opened a photography studio in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, where he produced government passbook photos as well as studio portraits for the nonwhite community. Moodley, a South African Indian and ardent antiapartheid activist, opened his studio to poor and working class sitters, who would have been classified by apartheid legislation as “Black,” “Indian,” or “Coloured.” Dating from the 1970’s and early ’80s, this selection presents a uniquely personal portrait of life in South Africa at a time of momentous social and cultural change. Deadpan and playful, the portraits are evidently self-styled by the sitters, who express themselves in different guises, attitudes, and modes of dress. In contrast to more familiar depictions of South Africa from the same period, in particular the accounts of violence and political turmoil by photojournalists seeking to reach an international audience, the Kitty Studio photographs capture the mood of everyday life. Following Moodley’s death, thousands of portraits from Kitty’s Studio were bought by the Campbell Collections in Durban. But, deemed too contemporary for their archive, which focuses on the history of southern Africa and KwaZulu-Natal, the negatives were discarded before being salvaged from the trash by an intern. After fifteen years of storage in a residential garage in Johannesburg, the collection was ultimately acquired by the sociologist and Columbia University professor Steven Dubin. Like the photographs of his great contemporary, Malick Sidibé, who captured the exuberant youth culture of Mali embracing the rock ’n’ roll age, Moodley’s images present us with a window into the transformations of South African culture in the second half of the twentieth century.

Erin O’Keefe, Things as They Are #11, 2015. Courtesy Denny Gallery

Sous Les Etoiles Gallery, 560 Broadway, New York

Through August 19, 2016

Since Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy first succeeded in severing photography from its figurative and narrative conventions, abstract and cameraless photography has become a field unto itself. In this elegant group exhibition, organized by the photographer Richard Caldicott, six artists display their concern for technical and material process in generating “concrete” or nonobjective photography, from Karl Martin Holzhäuser’s Lichtmalerei (Painting with light) (2002) to the computer-generated pinhole work of Gottfried Jäger. Ellen Carey’s photograms and paper negatives explore the relationship between the aperture and the frame. A series of small works by Erin O’Keefe (Things as They Are, 2015–16), which appear at first to be finely rendered paintings, are in fact photographs of painted and translucent materials that the artist, who trained in architecture, has carefully arranged. Inverting historical techniques, Luuk de Haan experiments with light sources such as digital screens to create his grainy, amorphous prints. Although some of the cameraless techniques exemplified in this exhibition date to the earliest innovations of the medium, they appear fresh in an era of photographic culture shaped by mobile camera phones and a relentless stream of digital images.

Genevieve Allison is a writer and editor based in New York.

The post 5 Photography Exhibitions to See This Summer appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

June 29, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Nicole R. Fleetwood on Prison Portraits

In America’s sprawling correctional system, where more than 2.2 million people are behind bars, prison studio portraits can hold a family together.

By Nicole R. Fleetwood

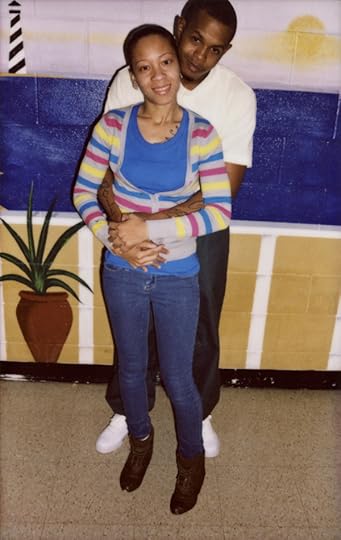

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family, 2012–14. Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery

One of the most voluminous sites for the production of contemporary black photography takes place in the visiting room of U.S. prisons. Makeshift photographic studios exist in jails and prisons across the nation and are an important, often the primary, arena for documenting incarcerated people and the loved ones—mothers, spouses, lovers, children, sibling, childhood friends—who visit them. Generally, prison photo studios are provisional spaces in the visiting room, or a waiting area, and are operated by incarcerated men and women whose job in prison is to serve as studio photographer. The studios are typically located near the guard booth and remain under the watchful eye of prison staff who monitor for suspicious activity, such as exchanging confiscated material or engaging in “inappropriate” physical contact.

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family, 2012–14. Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery

In Deana Lawson’s series Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family (2012–14), we see the power of prison studio portraits to document familial and intimate attachments for black Americans, who are disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex. Lawson’s images, which she appropriated from photographs originally taken by a prison photographer, document her cousin Jazmin’s visits to her partner, Erik, who was incarcerated at Mohawk Correctional Facility in Rome, New York. In some of the photographs, Jazmin and Erik hold each other affectionately. They kiss and hug. In others, they stand together as a family with their young children in the frame. The composition of these portraits follows the tradition of family portraiture in which the patriarch stands at center with wife, or maternal figure, and children at his side. Keeping in line with conventions of the genre, prison portraits also incorporate fantasy backdrops, which are often painted by incarcerated artists.

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family, 2012–14. Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery

Taken together, prison portraits become a powerful archive representing the enduring struggles of black Americans to claim citizenship, kinship, love, and even hope in the face of multiple forms of racial injustice—poverty, profiling, failed economic policies, and mass incarceration. They also document important forms of self-expression for the many millions who have been locked away and whose images and profiles are otherwise strictly managed by bureaucracies enforcing criminalization and incarceration. Moreover, prison portraits, which are often sent between incarcerated and non-incarcerated loved ones, are important material objects to maintain connection and to communicate love in some of the most dire and punitive conditions, that is, the modern U.S. prison system.

Nicole R. Fleetwood is Associate Professor in the Department of American Studies and Director of the Institute on Women at Rutgers University. Her research into visual art practices in prison life is the subject of her forthcoming book Carceral Aesthetics: Prison Art and Public Culture.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Nicole R. Fleetwood on Prison Portraits appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers