Aperture's Blog, page 132

September 20, 2016

Vision & Justice Online: Mark Bradford’s Pride of Place

The multidisciplinary artist investigates myths of black masculinity through costume, performance, and an iconic basketball jersey.

By Antwaun Sargent

Mark Bradford, Pride of Place, 2009. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Mark Bradford’s photographs, like his grid-based abstract paintings, are maps. They always seem to be charting the ways identity spreads across the different territories of the body. In Pride of Place (2009), a series of twenty chromogenic prints, Bradford becomes a cartographer of the body’s failure. The individual photographs show the limitations of the myth that the body is a neat container of race, sex, and gender performance.

Bradford, a very tall, black, gay man, was born in inner city Los Angeles in 1961. For Pride of Place, he transforms himself into an NBA star in drag, fashioning himself in a vintage Los Angeles Lakers jersey on top of a voluminous purple and gold dress. Against a warm, orange backdrop, he engages in a performance, playing up the physical expectations of height, weight, and appearance. In the foreground, the camera catches Bradford’s back as he rolls and falls. Arms failing, it seems as if he has lost his balance trying to be someone he’s not.

Mark Bradford, Pride of Place (detail), 2009. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

“Working within this landscape, for me, a 6’7” black male, is likened to Madonna (the singer, that is) being allowed to give a concert in Vatican City,” Bradford told Christopher Bedford in a catalogue interview for the 2010 exhibition Hard Targets at the Wexner Center for the Arts. “It’s just too good to pass up, and what is too good to pass up is the questioning of my maleness and the black body. So many times in America we think we know the black body, enough to understand and draw formal conclusions about it. I wanted to mix it up a little, to peek under the dress.”

Pride of Place was inspired by Bradford’s 2003 single-channel video performance Practice. For three minutes, Bradford’s moving image can be seen on a basketball court running, dribbling, and clumsily negotiating space and desire. At some point, he shoots—swoosh—nothing but net. The artist’s static and moving body in Pride of Place and Practice gesture toward what success looks like, even in failure.

Mark Bradford, Still from Practice, 2003. Single-channel video, 3 minutes, color, sound. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Antwaun Sargent is a writer based in New York. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Nation.

Mark Bradford will represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2017.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Vision & Justice Online: Mark Bradford’s Pride of Place appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 15, 2016

Wild Sync: Lucy Raven in Conversation with Drew Sawyer

In advance of the New York debut of her video installation Tales of Love and Fear at the Park Avenue Armory, Lucy Raven spoke with Drew Sawyer about sonic journeys near and far.

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015. Stereoscopic photograph, custom-built projection rig, and sound. Installation view, Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York. Courtesy the artist

Lucy Raven wanted to get wired. Searching for the networks of power that hold up global communications and commerce, she traveled from a pit mine in Nevada to a smelter in China to trace the transformation of raw ore into copper wire, the conduit for transmitting energy. China Town (2009), the resulting photographic animation, combines thousands of still images with on-location ambient sounds, locked together by wild sync—sounds that correspond to an image, but are not actually synchronized. For Raven, a New York–based artist whose practice incorporates photography, video, installation, and performance, the research becomes the work itself. Following China Town, Raven used test patterns for film and sound as both raw material and subject matter, turning the spotlight on standards for picture and audio quality developed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. Her experiments in 3D filmmaking yielded video installations that place stereoscopic photographs within immersive surround-sound environments. Connecting all of these disparate strands is the artist’s continuing exploration into the effects of technology and labor in the production of movies, as well as the poetic relationship between sound and image.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009. Photographic animation. Courtesy the artist

Drew Sawyer: Let’s start with your work China Town, which consists of thousands of still photographs and a sound track, and explores the production of copper from a pit in Nevada to a smelter in China. It’s not a typical film. I’m curious about your choice to use still images with a separate sound track rather than working in a more traditional video format.

Lucy Raven: The choice to use stills came first. I’d been working on stop-action animations and exploring ideas of work and exhaustion. When I had the initial ideas that led to China Town, I was still thinking about those questions. I had a residency with the Center for Land Use Interpretation at their site in Wendover, Utah, in the middle of the Great Basin. I became interested in a copper mine called Bingham Pit, where Robert Smithson had proposed, but never completed, a reclamation project.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009. Photographic animation. Courtesy the artist

The other impetus comes from Paul Valéry, who suggested that just as we receive water and gas and electricity into the home from far off with a very minimal effort, one day we’ll be receiving images and sounds into the home, appearing and disappearing with barely a signal of the hand, hardly more than a sign. Now that Valéry’s idea has become commonplace, and wireless technology has made images and sounds coming into the home ubiquitous, the part of his construction that I found more abstract was how water, gas, and, in this case, electricity get into the home.

So I had an idea from the beginning that the images and sounds would “appear and disappear” using some form of animation. As I began to work on the edit, with my editor Mike Olenick, it started to become clear that the sound would need to be continuous alongside the disjunctive imagery. It becomes a means of orientation. Each recording was made at the same location where I took the images.

Sawyer: How did you go about recording? Obviously, when you were going to these different locations, you were taking the still photographs. Were you simultaneously recording sound?

Raven: I couldn’t do both at the same time, because my camera made an audible shutter sound, so I had to switch between the two modes. Luckily, most every process I recorded in the film happens twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, so even though it sometimes required revisiting a site I hadn’t intended to return to, I was able to rerecord when necessary. I became very interested in experimenting with wild sync, which is when the sound corresponds to the image, but is not actually synchronized.

Lucy Raven, RP31, 2012. 35mm film. Installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Sawyer: Which is why your term animation makes so much sense, because in a way the sound is animating the images. That film makes me think of this idea of the “disassembled movie,” which Allan Sekula used to describe his piece Aerospace Folktales, from 1973. The work consisted of 142 photographs installed in a gallery like a filmstrip, and then four audio tracks played separately. This idea of the disassembled movie also relates to your work in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, RP47, and projects you’ve done at the Hammer Museum, like RP31, using test patterns, as well as purely audio works that are related, like 29Hz. What led you in the direction of looking into cinema?

Raven: Working on China Town prompted a number of questions having to do with the relationship between still and moving images, and, more basically, how movies are made today.

The works you’re referring to started with an interest in motion capture that I saw as related to—in some ways the inverse of—how I’d shot China Town. I had a research residency at the Hammer, and I visited one of the motion capture studios used for big Hollywood films. The day I showed up, everyone had just found out that a huge amount of the work they were doing would be outsourced to India, specifically the backdrops and landscapes for the figures developed through motion capture. They would also be sending over films shot in 2D to be converted into 3D through a very elaborate process that involves the digital creation of a synthetic second-eye view for every frame in the film. I found myself confronted with what seemed like a twenty-first-century version of China Town. Here, though, the raw materials being exported from the American West to overseas were images—literally raw files, one for every frame of film. In the case of 3D conversion, what was being outsourced was actually the lab or to produce the illusion of spatial depth.

Lucy Raven, Curtains, 2014. Anaglyph video installation, 5.1 sound, 50 minutes (loop). Courtesy the artist

I began trying to understand how 3D film works, and how it has developed technologically since its quite early invention. I found myself looking at 3D calibration charts, used to align dual 35mm projectors for 3D projection. The images were beautiful—the first ones I saw were clearly photographed from handmade paper maquettes that read “See with Left Eye” and “See with Right Eye.” I searched out more of these charts, and soon realized that there were charts used to calibrate and test most every type and gauge of film projector. This then led me to their sonic equivalent—test tones meant to play in an empty theater before showtime to calibrate the theater’s sound.

While I was researching and beginning production on the works having to do with Hollywood’s outsourcing of its images—the pieces that later became Curtains (2014) and then Tales of Love and Fear (2015)—I became interested in these charts as logging a history of the standardization of perception that was developed for optimal viewing and listening standards, yet born of economic, cultural, and technological conditions as much as for some notion of pristine image or sound.

Lucy Raven, 29Hz, 2012. Randomized audio samples from optical and magnetic

film sound track test material. Courtesy the artist

Sawyer: So 29Hz is the audio for test sounds.

Raven: Yes. I used twenty-nine different test tones in the work, and Hz is the abbreviation for hertz, which is the unit of frequency for sound. The RP in the filmic work titles is borrowed from the most common test pattern for 35mm film, RP40, where RP stands for recommended practices. In RP47, I included forty-seven different test patterns, and in RP31 there are thirty-one.

Sawyer: Does RP31 also have a sound track?

Raven: For RP31, you hear the sound of the 35mm projector that is running constantly, in tandem with a film looper, in the room. The presence and the sound of the projector is an important part of the installation. For RP47, I asked two genius friends, Jesse Stiles and Rob Ray, to design a software program for the work that would also enable me to add more images and sounds as I continued to find and archive them. The pairing of images and sounds in that piece is randomized, and the image stays up for as long as the duration of the sound file.

Sawyer: But they wouldn’t be related otherwise.

Raven: No, they are two different types of tests—one for sound, one for images.

Sawyer: So those projects led to Curtains, and then Tales of Love and Fear the following year, which both involve 3D images and surround sound.

Lucy Raven, Curtains, 2014. Anaglyph video installation, 5.1 sound, 50 minutes (loop). Courtesy the artist

Raven: Curtains consists of ten different scenes, each of which animates a stereoscopic photograph that I took in one of ten different post production facilities around the globe—from cities in Asia with very low labor costs to some of the most expensive cities in the world, such as London and Vancouver, where local governments offer studios massive tax breaks and incentives—that convert Hollywood films from 2D to 3D. In the piece, the stereoscopic image is split into left- and right-eye images using old-school anaglyph red-cyan separations. The two images come together from offscreen, briefly converge, then diverge again, passing through some strange intermediate zones of overlap that the eyes struggle, nearly involuntarily, to resolve. I recorded the sound in much the same way I approached it in China Town. The sound for each section is based on field recordings from each facility. They’re all office spaces, but the subtle differences between them register substantial differences in location, culture, and activity.

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015. Courtesy the artist

Tales of Love and Fear is a piece I worked on through a residency at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute up in Troy, New York. The idea was to make a cinema for a stereoscopic photograph. In collaboration with EMPAC’s amazing production team, we built a rig that enables 360-degree rotation of two projectors over the forty-minute duration of the work. The rig acts as both 3D film projection apparatus and as a kinetic sculpture performing the architecture of the space.

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015. Courtesy the artist

DS: How are the image and sound related?

Raven: The image comes from a stereo photograph I took of bas-relief carvings at a site in India. One of the first sounds you hear in the piece is from a field recording I’d made while seeing a Bollywood horror film with a few friends. One of them, an actress, was translating to me in real time from Hindi to English—the film’s sound was pulpy and totally overblown.

So my friend is doing different voices while whispering the translations, people are screaming, and we’re eating popcorn and laughing. Paul Corley, a composer and sound engineer, worked with me to shape a score, a sonic journey from the Mumbai movie theater, into the film itself, and out the other side into a very different, nearly meditative drone state.

Lucy Raven, Fatal Act, 2016. Promotional image. Courtesy Thirteen Black Cats

Sawyer: Your most recent project, Fatal Act, involves, in part, the history of one sound in particular.

Raven: Yes, sound is an important aspect of Fatal Act, a new moving-image work I’m currently at work on with my research and production collective Thirteen Black Cats. The eventual film centers on the difficulty of imaging and recording the atomic. One scene includes the description of a CBS sound engineer tasked with providing sound for a nuclear-bomb test detonation in Frenchman Flat, Nevada, in 1951. Camera crews had been invited to film the explosion for television broadcast, but to escape fallout, they were necessarily positioned too far away to record sound. Given three turntables, twenty minutes, and the CBS sound library, the engineer improvised, using the slowed-down roar of an African waterfall to make the now iconic sound of an atomic chemical fireball.

To read more, buy Aperture Issue 224, “Sounds,”or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Drew Sawyer is William J. and Sarah Ross Soter Associate Curator of Photography at the Columbus Museum of Art, where he organized the exhibition Lucy Raven: Low Relief, on view April 29–November 27, 2016.

Lucy Raven’s Tales of Love and Fear is presented at the Park Avenue Armory on September 29–30, 2016.

The post Wild Sync: Lucy Raven in Conversation with Drew Sawyer appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 14, 2016

Jason Fulford Can’t Be Contained

Jason Fulford, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

When encountering Jason Fulford’s work, just remember, “If you came here to have fun, you will. If not, you won’t.” His photographs and, in particular, his photobooks, are enigmatic, ambiguous, and profound. By embracing these qualities, he has expanded the possibilities for his practice and for the photographic medium. A photographer, publisher, and designer, Fulford has also previously appended his print work and exhibitions with interventions and events.

His new publication, Contains: 3 Books (forthcoming from The Soon Institute in October), offers another opportunity to be open-minded. For the extensively researched book, funded by a Guggenheim Fellowship, Fulford traveled to fifteen countries. Within the publication are three funny, strange, and stimulating volumes—I Am Napoleon, Mild Moderate Severe Profound, and &&—in no particular order. Contains: 3 Books will fascinate and delight, but it won’t answer all of your questions. —Ashley McNelis

Jason Fulford, Time to Re-Order, 2016. Courtesy the artist

Jason Fulford: I’m glad we’re in Gowanus because after this I need to do some silk-screening two blocks from here.

Ashley McNelis: What are you printing?

Fulford: It’s for a little show down in Philadelphia. I’m making a postcard rack, like the ones you see in a tourist store. It’ll be filled with cards that you can take that say “TIME TO RE-ORDER.”

McNelis: Oh, I like that! Where in Philadelphia?

Fulford: At Crane Art’s Icebox Project Space. Christopher Gianunzio is curating a photography section with pieces by Lucas Blalock, Carmen Winant, Whitney Hubbs, and others, along with several other local curators in one big space.

McNelis. It sounds like a good excuse to take a trip to Philly! Let’s start by talking about literature. The first time I went through Contains: 3 Books, I almost paid more attention to the text than the images. You’ve published several books of your work, designed covers for fiction books, and you’re a big reader. Can you speak to the connection between the image and the word in your work?

Fulford: It’s played out in a lot of different ways over the years, and also in each of these three books. In I Am Napoleon, the texts are excerpts from books I was reading at the time, sequenced into a narrative. The pictures and the words play off each other in an associative way. In &&, the only text is on the cover and in the colophon. It’s a book of single images, so I put a full white spread in between each picture so you wouldn’t naturally think of it as a sequence. Mild Moderate Severe Profound has a caption for each picture, and they are all true stories.

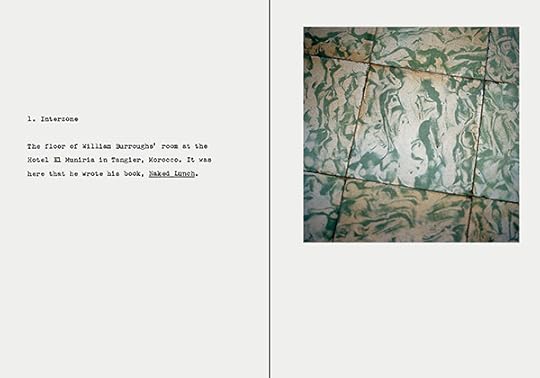

In that book, the captions work in a traditional way, to directly explain the images. I’ve never done that before except in magazine assignments. The texts have a literal connection that adds meaning to the images. For example, take the first picture of the floor tiles in Mild Moderate Severe Profound. It might not have much significance to you, except for maybe it’s graphic quality. But when you find out that William Burroughs stayed in that room when he wrote Naked Lunch (1959), then it means something more. In my book Hotel Oracle (2014), one of main themes is the idea that you can add meaning to places or to objects through storytelling. In this group of three books, I see Mild Moderate Severe Profound as one of the grounding elements. It gives you a clue to what the whole project is about.

Jason Fulford, spread from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: Where did you find the inspiration to pair photographs and texts in this manner?

Fulford: One book that may have played a role, subconsciously, is A Forgotten Kingdom by Mike Nelson—the British artist who creates big, realistic-looking installations—for his show at the ICA in London in 2001. He reproduced a dozen or so chapters and excerpts from different books where there was some connection to the theme, and sequenced them to form a new book. It was published on cheap, yellow paper so it felt like a pulp paperback.

When designing a book, I go back and forth between a macro view and a micro view. In Mild Moderate Severe Profound, each spread is an independent unit with text and image, but there is also an overall arc to the book. One big influence in terms of that structure is a book from the nineties by German artist Ute Behrend called Girls, Some Boys and Other Cookies (1996).

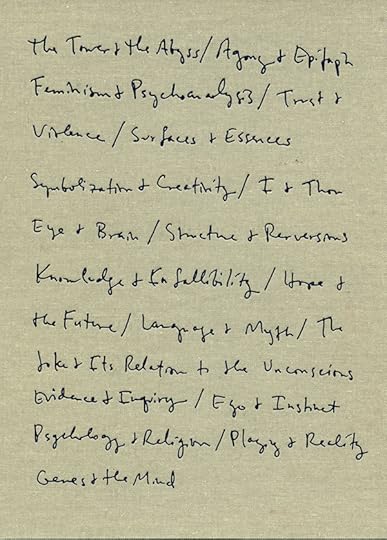

McNelis: What else were you reading?

Fulford: I’ve been working on a series of upcoming workshops and re-reading old texts from college like Entropy and Art (1971) by Rudolf Arnheim. I got the same headache I did the first time I read it! It’s so worth it in the end though. He explains two different interpretations of entropy and the second law of thermodynamics. One focuses on the idea of maximum disorder, and the other on equilibrium—that a closed system reaches equilibrium when no other action can happen without an outside force. When I didn’t know if my book The Mushroom Collector (2010) was finished, my friend Stuart said, “You’ll know when it’s ready because it will come to a place where it can’t possibly be anything other than what it is.” It’s the point in editing where everything, like the macro/micro view, locks into place.

Jason Fulford, image from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: I definitely perceived both the individual and overarching elements in the books. I remember you mentioning Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon, ambiguity, mysterious places, and open metaphors. Do you internalize what you find in literature and develop those ideas in your work?

Fulford: Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon were really early influences on me. Books, conversations, films, art, and music all feed into your subconscious. Those ideas affect what and how you see. That’s the best thing about art, I think. If you and I went out and made pictures on this block, we would make very different pictures because we would be looking at different things.

There’s a quote by Goethe that was supposedly found in Edward Hopper’s wallet when he died that I love: “The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me, all things being grasped, related, recreated, molded, and reconstructed in a personal form and original manner.” Think of every person as a filter taking in similar stimuli and then working it through their own life experience before putting it back out there.

McNelis: This would be a good place to transition into talking about ambiguity. You’ve read William Empson, who wrote that ambiguous language makes poetry more interesting. Do you think that that concept of ambiguity can be applied to photography?

Fulford: Yes, and it’s one of my favorite things about photography. When you embrace the fact that pictures are inherently ambiguous, the possibilities open up in terms of using images as language.

I was just down in Atlanta for a week with my mom. I brought a copy of Contains: 3 Books to show her. She admitted that she always wants to be spoon-fed, which is the opposite of anything I usually try and do. We had a good time talking about it. We love each other a lot, but we can be very different.

John Cowper Powys, The Inmates, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: That tends to happen with family. The prefatory note in I Am Napoleon—“I think that any book or picture or composition of any sort, once out into the world, so to say, produces a different effect on each person who seriously tries to follow it. I certainly do not think that the author of it has any monopoly in its interpretation”—was a perfectly apt way to begin the project and introduce how you want the reader to approach it.

Fulford: It was written by John Cowper Powys in a book called The Inmates (1952). He was a (literally) crazy British writer and mystic that Tod Papageorge recommended to me. He moved to the United States and made a living by impersonating famous writers from history and touring to give lectures as them. He then married a New Yorker and moved upstate to a small town that reminded him of the countryside in England where he grew up. He wrote some of his most famous novels from there. I had an idea with Aaron Schuman, who actually lives in the area where Cowper Powys was from in England, that I would take pictures in upstate New York and he would shoot in England, then we would mix them together and make a book. Somehow it never panned out but we still like to talk about it.

The Inmates had a beautiful green cover with the title written in black in sign painter’s casual font. I bought it for the cover, and later found out that it’s worth reading. It takes place in an insane asylum in England. In the preface he talks about how he’d read a lot of books about insanity and that none of them seemed to acknowledge the humor and the humanity in these places. The story is funny and deep.

McNelis: How did you approach organizing such a large topic?

Fulford: I read a lot of both fiction and non-fiction related to madness over three years and made many notes in the margins. At the same time, I was shooting pictures as I traveled, letting the reading guide my eye. I tried organizing the results in different ways. At one point I literally categorized the pictures as disorders and phobias, and it felt too contrived. A friend gave me a box of psychological tests that are given to children. It contains a lot of little differently sized, spiral-bound books. One is a small book of drawings where there’s one thing wrong in each that you have to identify, like a hand where one finger doesn’t have a nail. At first I wanted to make book that felt like these tests, but it ended up feeling too serious. I wanted my book to feel more open and playful. I hope the reader gets some pleasure from it, rather than feeling like they’ve been lectured to.

Jason Fulford, image from I am Napoleon, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: How do you hope that the viewer will view or interpret Contains: 3 Books?

Fulford: I’m wary of directing the reader too much, especially since a topic like the one these books deals with comes with a lot of preconceptions. I mean we all have some connection to it whether it’s mild or moderate or severe or profound. I ended up focusing on a middle range, somewhere between mild and profound; it’s a range in which there’s a humanity, an imperfection that is potentially valuable. One thing people may think about while reading the books is the subjectivity of the term “madness”—how it changes depending on each person’s culture or peer group. I always say that I don’t want people to think about me when they read these books. You’re going to think about yourself anyway, but I actually want you to think about yourself.

McNelis: It must be challenging to produce a work that’s so open-ended.

Fulford: I’m really comfortable with unanswered questions. I think you have to be game for that to enjoy any of these books. I saw a sign once at a spot where normal laws of gravity don’t apply; strange things like optical illusions happen in areas like that. The sign at the entrance to the spot said, “If you came here to have fun, you will. If not, you won’t.” You have to be open to playing the game to get anything out of it. Otherwise it’s only frustration or cynicism, depending on your personality.

McNelis: I’d be curious to hear more about your photobook practice. I’ve always thought it was very distinct, particularly because of the events and happenings you do for their launches. Do you know the Rosalind Krauss essay, “Sculpture in the Expanding Field,” from 1979? In it, she questions sculpture and discusses its new elasticity. Photography, like sculpture in the mid-twentieth century, has expanded to become a very transitional and fluid medium. Photographs and photobooks can be anything now. The nature of having events—like what you did with The Mushroom Collector and Hotel Oracle—actively sends these objects and ideas out into the world.

Fulford: Those events came about almost by chance, the way one thing leads to the next. It started in collaboration with my editor, Lorenzo de Rita. We wanted to release my books to the world, but we didn’t want to just have normal book parties. We wanted to pick up on ideas in the books, and communicate them in a different way. The events are an excuse for me to use different tools, and they’re fun. I’m also a graphic designer, and I like to build things. The events run parallel to the books and work almost like appendixes. We’ll be planning some for Contains: 3 Books in the fall and winter.

Jason Fulford, cover of &&, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: I can’t wait! Lorenzo’s collective, The Soon Institute, sounds like an incredibly flexible and ambiguous practice. I can’t imagine some of his projects in physical form.

Fulford: Ambiguity defines his life. I love working with him, in part because he always makes sure that everything stays very open until the last possible moment. He’s a bit of a procrastinator, and that’s part of the deal. It’s a good way to make books.

McNelis: Definitely. In addition to working with Lorenzo, you’ve done work with author, illustrator, and designer Tamara Shopsin, and published books with author and illustrator Leanne Shapton through J&L Books. Have you always been open to collaboration?

Fulford: I’ve been lucky to have found great collaborators—where we each bring something that complements the other. When that happens, the final product is always so much better than anything I could have done by myself. And I respect good editors. They each have their own way. Lorenzo, for example, never says, “no.” Instead he just gently suggests—puts ideas into your mind that eat at you until you make a revision. But Tamara will say, “NO,” a lot, and that’s also useful sometimes.

The Photographer’s Playbook (2014) was a big collaboration—not only with Greg Halpern and the staff at Aperture, but with all 307 contributors. Everybody brought totally different things to it. Like a dictionary, it’s a book you can read over the rest of your life. I also love the feeling of kinship that arose from the fact that we all care about photography even though we come at it from our different points of view.

McNelis: Can you talk about your editing process?

Fulford: These days I scan my negatives and edit in InDesign. But I used to work with two sets of contact prints which allowed chance to play a big role. I was just reading about the Jean Arp collages where he would drop cut paper onto paper and glue them down. Or how William Burroughs wrote on multiple sheets of paper and then rearranged them. I work in a similar way, using chance combinations to find unintentional connections between pictures.

McNelis: I read somewhere that you like jazz, which made me think of your sequencing as composing and the individual elements in terms of polyphony and harmony. It’s as though each diptych is a stanza within the whole arrangement.

Fulford: Around the time I made my book Raising Frogs for $$$ (2006), I was listening to and reading a lot about polyphony—from Bach to György Ligeti to African drums—with a little Gestalt theory mixed in. Those ideas transfer well to book design and photo sequencing.

I’ve also been re-reading Alain Robbe-Grillet and Roland Barthes, who both liked to talk in big circles. It’s a fun ride but you often end up in the same place you started. I relate that to a larger philosophy on life where, maybe it’s a cliché idea, but it’s more about the process than the final goal.

Jason Fulford, image from I am Napoleon, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: Whenever I read theory, I’m never looking for just one answer. It’s more of a lens through which to look at everything. There’s too much to contain.

Fulford: Agreed. I grew up with religion, so for me, theory is like church on Sunday—the abstract day where things are talked about as pure ideals, whereas the rest of the week is messy.

McNelis: Speaking of the abstract versus the concrete, one of my favorite images in the book featured the bizarre legends of the Brno Wheel and Dragon.

Fulford: The Brno City Hall entrance is truly surreal. When I was in Brno, there also happened to be a traveling exhibition in town on the topic of Surrealism in graphic design, put together by Rick Poyner. That was the perfect town to have that show.

McNelis: The Czech Republic is kind of surreal. There’s a lot of great art, too. Do you like Fluxus?

Fulford: Yes, though I’ve only learned about it piecemeal. There’s a great library of artist’s books in Chicago called the John Flaxman Library, part of the Art Institute. I spent some time there last year and was able to see a lot of incredible Fluxus originals.

Jason Fulford, image from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: They really loved their happenings. Can you talk about the events you’re planning for the book?

Fulford: I think it’s going to be somehow related to the word “Contains.” The website we made for the book has that word as its structure, with a list of contents to the right of it. I think we’ll keep adding to the list of contents as we plan events. The first one, in New York City on September 16, is actually three simultaneous events—“Contains: 3 Events”—all in the Lower East Side. Each one will have a sort of performance that happens in a loop, so you can go see them all.

The overarching idea is that the book contains the three books, but it also contains other things, like three years of traveling, a Guggenheim fellowship, research, etc. There’s that famous Walt Whitman quote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” I like it as a reminder to appreciate that you can have multiple views at the same time. Though I’m not sure I would like to have multiple personalities. Did you see the obituary in The New York Times recently for the woman who inspired the 1957 film The Three Faces of Eve? That was an extreme case; there are milder versions of multiple personality disorder that can be inspiring. I think of Martin Kippenberger as having extremes of punk and respectability.

McNelis: How did you come to publish Martin Kippenberger’s biography by his sister?

Fulford: I was a fan of his work, mostly from books. I hadn’t seen much of it in real life. Leanne (the L of the imprint J&L) was in Germany having dinner with her editor and Susanne Kippenberger. At dinner, Leanne sent me a text that Susanne was looking for an English language publisher for the biography of her brother, Martin Kippenberger! I just wrote back, “Let’s do it!” It was happenstance.

McNelis: The publishing company and your practice work very well together. I look forward to seeing what else you publish!

Fulford: Well, on the topic of books, I’m really excited about my next, next book. But I have to try to hold off until I get Contains: 3 Books out into the world!

Ashley McNelis is a writer, curator, and art historian based in New York.

Jason Fulford’s book launch for Contains: 3 Books takes place as three simultaneous happenings on the Lower East Side on Friday, September 16, 2016.

The post Jason Fulford Can’t Be Contained appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 13, 2016

Viral Images Ignite Calls for Social Change

In the wake of this summer’s violent shootings caught on camera, an exhibition at the Bronx Documentary Center considers the impact of citizen journalism.

By Amelia Rina

On August 6, 1988, New York City police attempted to enforce a curfew during a rally held at Tompkins Square Park. Clayton Patterson filmed the event on his VHS camcorder and his footage captured multiple incidents of police brutality, leading to the indictment of six police officers. Courtesy Clayton Patterson

On the Internet, there’s power in numbers. Viral images, videos, and even live feeds posted by ordinary people can upend mainstream media and drive political dialogue. But, the impact of citizen journalists isn’t a phenomenon unique to our hyperconnected era. When photojournalist and Bronx Documentary Center (BDC) cofounder Michael Kamber first conceived of the exhibition New Documents, he began with what he describes as the “disintegration of the traditional media and professional journalism [into] citizen journalism,” propagated on social media. “Increasingly,” Kamber explained to me recently, “ordinary citizens who happen to be on the scene with cell phones are not just influencing, but really controlling our national conversations and agendas.” Kamber worked with Danielle Jackson, former cultural director of Magnum Photos, to compile a selection of photographs and videos made between 1904 and the present. The images and their associated texts in New Documents, on view through September 18, demonstrate the indispensable role citizen journalists have played in the documentation of violence and social injustice, and, perhaps most importantly, the widespread circulation of evidence.

Videos recorded on mobile phones show the first protests in response to the suicide of 26-year-old Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, who set himself on fire in front of a government building after his produce had been confiscated by the police. Bouazizi’s public suicide marked the beginning of the Arab Spring. Courtesy YouTube

The installation, like the cameras used to create its contents, boasts no extravagant bells or whistles. Situated in the 1,000 square-foot storefront of the BDC’s West 151st Street building, the exhibition chronicles the recent history of image capturing and sharing technology, from early cameras to Facebook Live. Along one gray wall, punctuated with recessed displays, visitors encounter photographs and magazines, as well as videos playing on a variety of devices. This combination of materials produces a potent contrast between the unspeakable, yet chillingly familiar horrors enacted by humans, and an invigorating optimism, offering a concentrated perspective on nonprofessional media and a sense that positive change is possible through visual activism.

One of four photographs secretly taken in August 1944 at the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz by a special unit of prisoners known as sonderkommandos. They were charged with disposing corpses of gas chamber victims, and documented their activity using what an eyewitness has described as a Leica. Alberto Errera, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Poland, August, 1944

Originally slated to open in mid-July, Kamber realized he needed to reevaluate New Documents after the first eight days of July saw the deaths of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minnesota, and the shooting of five police officers by a sniper in Dallas. Kamber reached out to Jackson to steer a new curatorial agenda. (The exhibition later opened on July 28.) Together, revising the original criteria, they decided that each document in the exhibition must have been made by bystanders witnessing socially charged events—as opposed to state-owned cameras, perpetrators’ cameras, or surveillance cameras—and the distribution of the images must have been intended as a means of exposing injustice.

Nsala of Wala with the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter, who was murdered by an ABIR (Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company) militia, a result of King Leopold of Belgium’s brutal colonial rule, ca. 1904. Courtesy Alice Seeley Harris/Anti-Slavery International and Autograph ABP

New Documents begins with a 1904 image by the English missionary Alice Seeley Harris depicting a Congolese man, Nsala of Wala, sitting next to the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter. Nsala’s daughter, son, and wife were killed and dismembered by sentries of the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company as punishment when the village did not meet the required rubber production quota. Seeley, who documented the shocking brutality of Belgian colonialism and the rubber trade in the Congo Free State, ignited social indignation when her photographs were published in Europe and the United States. One of the first examples of a human rights campaign in which photography was deployed as evidence, Seeley’s photographs greatly contributed to King Leopold II relinquishing his tyrannical control of the Congo to the Belgian government in 1908. The New Documents timeline ends with the video live streamed to Facebook by Diamond Reynolds as she recorded the death of her partner, Philando Castile, who was shot by a police officer after being pulled over in a suburb of St. Paul. By the next morning, the video was the lead story across media outlets in the U.S. and abroad, resulting in widespread protest, both online and in the streets.

From the front seat of a car, Diamond Reynolds livestreams to Facebook as her partner, Philando Castile, lays dying next to her from a policeman’s bullet. Reynolds confronts the police officer as she talks into the camera and recounts the moments earlier when the police officer fired on Mr. Castile. St. Paul, Minnesota, July 2016. Courtesy Diamond Reynolds/Facebook

Between these bookends, New Documents includes photographs such as the only existing images of Auschwitz taken by a prisoner, which show Jews being led to a gas chamber and their bodies being burned, and a 2004 photograph of the coffins of American service members killed in Iraq, extending far down the cargo hold of a plane returning to the U.S. The U.S. government had maintained a 1991 ban on the publication of images of military caskets, making this image, at the time, one of the few media representations of deceased soldiers. (The ban was lifted in 2009.) The videos on view range from infamous citizen recordings such as the 1963 assassination of president John F. Kennedy and the 1991 beating of Rodney King, to the 1978 secret dumping of nuclear waste by the British ship Gem, 400 miles off the coast of Spain, and the 2009 death of Neda Agha-Soltan, an innocent bystander passing through a protest in Tehran, Iran against then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

The coffins of American service members killed in Iraq sit aboard a cargo plane waiting to be sent back to the United States. Kuwait City, Kuwait, 2004. Courtesy Tami Silicio/Zuma Press

Though each of the many images alone carries tremendous weight, the most affecting element of New Documents is the illuminating dialogue between image and text. Apart from date and location, the texts accompanying each document describe the result of the image, effectively elevating the photographs and videos to a level of social relevance and accessibility. In her 2013 essay “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?” the filmmaker and artist Hito Steyerl argues against the notion that images are objective or even subjective representations of human experience. Instead, she writes that they are “nodes of energy and matter that migrate across different supports, shaping and affecting people, landscapes, politics, and social systems.” New Documents activates the energetic potential of photography—whether analog or digital—and encourages viewers to play an active role in the fight for individual autonomy and freedom.

Amelia Rina is a writer, critic, and editor based in Brooklyn.

New Documents is on view at the Bronx Documentary Center through September 18, 2016.

The post Viral Images Ignite Calls for Social Change appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 12, 2016

Alex Webb’s La Calle Gives Voice to Mexico’s Streets

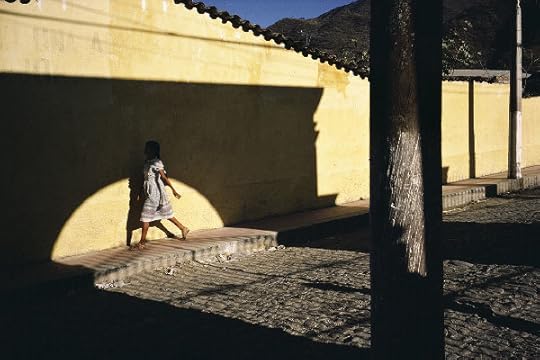

When photographer Alex Webb first visited Mexico in 1975, he was immediately captivated by the intense light, color, and energy of its streets. Over the next few decades, he would return numerous times, drawn to the U.S.-Mexico border, and then into southern Mexico in the 1980s and ’90s. Casting his preconceptions aside, he allowed his camera to lead him.

“I work extremely intuitively,” Webb said in a recent interview at the Aperture Gallery, where his exhibition La Calle is currently on view. “I wander, I respond. I don’t work rationally at all. Am I aware of certain elements rationally at times? Sure. But I think that often when I am more aware of them, it usually means that the picture falls flat.”

The resulting images are multilayered and evocative. In each of his street photographs, Webb distills gesture, light, and cultural tensions into single, mesmerizing frames that convey mystery, irony, and humor. Now, La Calle, a photobook and corresponding exhibition, bring together over thirty years of Webb’s images. The work commemorates the Mexican street as a sociopolitical bellwether—albeit one that has undergone significant transformation since Webb’s first trips to the country.

Throughout the photobook, commissioned texts by noted Mexican and Mexican-American authors Guillermo Arriaga, Álvaro Enrigue, Valeria Luiselli, Guadalupe Nettel, and Mónica de la Torre lend further insight into the roles the streets have played for generations, reflecting Mexico’s past, projecting into its future, and providing a stage for the theatre of everyday life.

“I think that their words, on some level, give voice to the streets of Mexico, specifically Mexican voices, which is distinctly different, and hence complimentary to what my photographs do,” Webb said. “I love the fact that Valeria Luiselli’s piece refers to the hideousness of a street, but how she loves the street because it’s hideous. I thought that was kind of wonderful.”

Alex Webb, Ajijic, Jalisco, 1983; from Alex Webb: La Calle (Aperture/Televisa Foundation, 2016) © Alex Webb / Magnum Photos

Alex Webb: La Calle, Photographs from Mexico is available here. The corresponding exhibition will be on view at Aperture Gallery through October 26, 2016.

Alex Webb: La CalleLa Calle brings together more than thirty years of photography from the streets of Mexico by Alex Webb, spanning 1975 to 2007. Whether in black and white or color, Webb’s richly layered and complex compositions touch on multiple genres. As Geoff Dyer writes, “Wherever he goes, Webb always ends up in a Bermuda-shaped triangle where the distinctions between photojournalism, documentary, and art blur and disappear.” Webb’s ability to distill gesture, light, and cultural tensions into single, beguiling frames results in evocative images that convey a sense of mystery, irony, and humor.

Alex Webb: La CalleLa Calle brings together more than thirty years of photography from the streets of Mexico by Alex Webb, spanning 1975 to 2007. Whether in black and white or color, Webb’s richly layered and complex compositions touch on multiple genres. As Geoff Dyer writes, “Wherever he goes, Webb always ends up in a Bermuda-shaped triangle where the distinctions between photojournalism, documentary, and art blur and disappear.” Webb’s ability to distill gesture, light, and cultural tensions into single, beguiling frames results in evocative images that convey a sense of mystery, irony, and humor.Following an initial trip in the mid-1970s, Webb returned frequently to Mexico, working intensely on the U.S.–Mexico border and into southern Mexico throughout the 1980s and ’90s, inspired by what poet Octavio Paz calls “Mexicanism—delight in decorations, carelessness and pomp, negligence, passion, and reserve.” La Calle presents a commemoration of the Mexican street as a sociopolitical bellwether—albeit one that has undergone significant transformation since Webb’s first trips to the country. Newly commissioned pieces from noted Mexican and Mexican American authors lend further insight into the roles the streets have played for generations: part arterial network, part historical palimpsest, and part absurdist theater of the everyday.

$60.00

The post Alex Webb’s La Calle Gives Voice to Mexico’s Streets appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

In Amsterdam, Predicting the Future of Photography

Christto & Andrew, The Rumble in the Jungle, 2016 © the artists

Aperture: Since its first edition in 2012, Unseen Photo Festival has set out to present unknown talents and unknown works by major, established artists. Or, as the campaign artist duo Christto & Andrew put it, to “‘predict’ the future of photography.” Now in its fifth year, what has changed? What can audiences expect from this year’s Unseen? Are there still unknown images to discover?

Emilia van Lynden: From its inception, Unseen has indeed aimed to show what is currently happening within the world of contemporary photography, to look to the future of the medium instead of focusing on its past. To predict the future of photography is, however, impossible as its future has many paths: there are multiple directions in which photography is moving and many of these futures are visible at Unseen.

One of them is the notion of embracing the history of the medium in completely new ways. We have seen more emerging artists who maintain the analog elements of photography: artists who reject the need to move completely into the digital realm, artists who instead step back into the darkroom to experiment with historical tools or methods. It is these artists who still primarily see the photograph as an independent object and want to focus on the craftsmanship of photography. This is why we have chosen to curate a show with the photographer and film director Anton Corbijn in this year’s Unseen Photo Festival, which highlights a range of artists who still believe in the intrinsic value of the photograph as an object. The exhibition will include artists such as Antony Cairns, Thomas Mailaender, Daisuke Yokota, and Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs. Additionally, the works of Nerhol, Adam Jeppesen, and Paul Kooiker will be included.

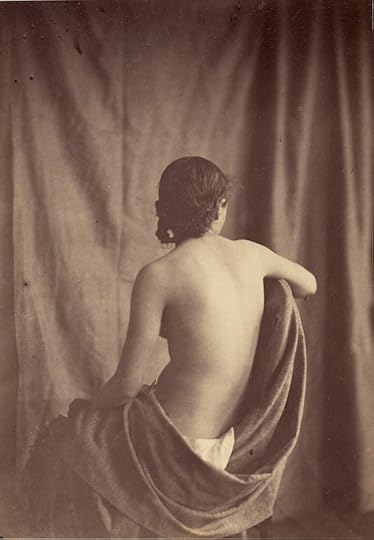

Paul Kooiker, History X (hxgfghv), 2016 © the artist and courtesy tegenboschvanvreden

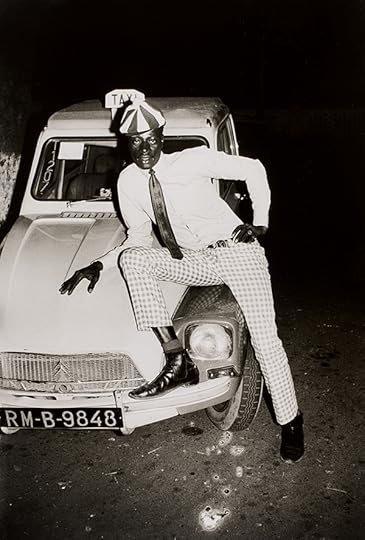

We are also creating a project at the fair site that hones in on the future of African portraiture. There has been a recent resurgence in the presentation of African portraiture within the photography community, especially through the work of masters such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta. We want to show what emerging artists on the African continent are currently doing with portraiture. Some of these artists, such as Pierre-Christophe Gam, reference African photographic heritage but interpret it in their own completely different ways. Others have looked at the portrait in novel ways, not looking back at past practitioners. Their work raises the question: Is there such as thing as “African portraiture”? The project Face to Face, cocurated by the magazine OFF the wall, invites seven artists to Unseen to run a pop-up studio, including Atong Atem, Delphine Diallo, Laila Hida, Lebohang Kganye, Louis Philippe de Gagoue, Pierre-Christophe Gam, and Zanele Muholi, who will take portraits of visitors.

Unseen Festival visitors and Unseen Magazine readers can also look forward to discovering brand new work through Unseen Premieres, which we introduced three years ago. These are works that have never been seen before in a gallery, institution, or at an art fair. We are overjoyed to be able to premiere seventy-nine artists at this year’s edition of Unseen. This means that people will be viewing works that have never been physically seen before and this is, of course, a hugely exciting moment for us.

Atong Atem, fruit of the earth, 2016 © the artist and courtesy Red Hook Labs

Aperture: Each year, the location of the Unseen Photo Festival within Amsterdam changes in order to introduce audiences to different neighborhoods. Why was Spaarndammer chosen for this year and what does the neighborhood have to offer?

van Lynden: Spaarndammer has a fascinating social history. Renowned for being heavily socialist during the twentieth century, the neighborhood was extremely community-led and there was, and in many ways still is, a great sense of helping one another within the entire neighborhood which has made the community very close. Additionally, this geographical area is where the architectural style of the Amsterdam School was born in order to increase social housing opportunities for local families. Many of the breadwinners within these families were craftsmen and they were housed in what is now Het Schip, the neighborhood’s main museum. Having researched the history of Spaarndammer, we thought it was the perfect place to host our exhibition TOUCHED: Craftsmanship in Photography, curated by Anton Corbijn. This year we are also celebrating the 100-year anniversary of the architectural style, so the timing couldn’t be better.

Antony Cairns, LA-LV 45, 2015 © the artist and courtesy Roman Road

Aperture: In addition to the fair, what are the other events around photography taking place in Amsterdam, either at museums, bookshops, or pop-up spaces? What are some of the highlights of the public programs?

van Lynden: Unseen Photo Festival has an extensive program of pop-up exhibitions and workshops throughout Amsterdam. In one of Amsterdam’s public libraries, Zines of the Zone, which hails from France, will set up an exhibition showcasing the scope and variety of photography zines. They will also be leading a zine-making workshop introducing the public to the extensive possibilities of what you can do with recycled materials. This collaboration links to one of the Unseen Niches—presentations given over to artist-run initiatives or collectivest the fair, the New York-based 8 Ball Zines, will create an exhibition based on zine swapping. Christto & Andrew are inhabiting an outdoor public swimming pool, Het Brediusbad, to put on an exhibition entitled The Politics of Sport, which focuses on absurdities of the sports industry, particularly in countries that host major sports events despite having no tradition of this form of recreation. Another highlight is Artist Recipes that takes place in a community restaurant in the Spaarndammer neighborhood where visitors can have a three-course dinner curated and hosted by emerging artists. Lastly, Unseen is collaborating with sixteen of Amsterdam’s public institutions, ranging from the Stedelijk Museum to Foam and Huis Marseilles.

Thomas Albdorf, I Made This For You, 2016 © the artist

Aperture: The ING Unseen Talent Award spotlights young European photographers. What is special about this award and could you give us a preview of this year’s nominees?

van Lynden: This year we decided to make the ING Unseen Talent Award a fully European award, selecting scouts from across the continent to nominate their favorite young artists.

I think the most important aspect of the award is the coaching trajectory, which we set up with the nominees in the months leading up to Unseen. This year, American photographer Todd Hido is the coach of the award, guiding the five nominees over a four-month period to make one specific work to be presented at the fair. The nominees are also given advice from other photography professionals and therefore get a range of insights to which they might not have previously had access. The nominees also get the chance to give feedback to their peers, which I think is an exceptional way of working with artists who are at the same stage in their careers.

This year’s nominees are Thomas Albdorf, Felicity Hammond, Laurianne Bixhain, Miren Pastor, and Tereza Zelenkova. They all have approached the theme of this year’s award “Fool for Love” from completely different angles ranging from human relationships and the foolish side of adolescence to being fooled by the love we have for our urban surroundings.

Femke Dekkers, Vaas (1), 2016 © the artist and courtesy Galerie Bart

Aperture: What artists are you particularly excited to see participating in Unseen this year?

van Lynden: We present the work of over 150 artists and will be exhibiting more than seventy Unseen Premieres at the fair. I am looking forward to seeing all of our premieres, but to name a few, I am hugely excited about the newest work of emerging artists Juno Calypso, Femke Dekkers, and Jonny Briggs, as well as new or previously unexhibited work of more established artists Roger Ballen, Isaac Julien, and Christiane Feser.

Christiane Feser, Partition 48, 2016 © the artist and courtesy Anita Beckers

Aperture: Unlike most of the major art fairs in Europe and the U.S., Unseen is only focused on photography. Even though lens-based media has become integrated into so many contemporary, interdisciplinary art practices today, why do you think it’s still important to celebrate photography as it’s own art form?

van Lynden: Unseen is a niche fair in the sense that we only work with photography and, on top of that, we only show work created in the last three years, with a definite focus on emerging talent. We put photography in the limelight because there are so many artists working within this medium and creating phenomenal works of art, tackling global issues, and telling relevant stories. Photography is moving at such a rapid pace—and we applaud and welcome new forms of interdisciplinary practice—but we believe it’s essential to come together once a year and focus solely on what is happening right now within the medium.

Unseen Photo Festival takes place in Amsterdam from September 16–25, 2016.

The post In Amsterdam, Predicting the Future of Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 8, 2016

No System

On the road with Vinca Petersen, who chronicled the raves, free parties, and traveling sound systems of ’90s-era Europe.

By Sheryl Garratt

Vinca Petersen, No System, 1999. Courtesy the artist

Vinca Petersen didn’t set out to be a photographer. Her pictures began as a visual diary, documenting her leaving home at the age of seventeen, moving into a London squat, and becoming involved in the free party scene that blossomed across Europe in the 1990s. She has built up an impressive archive that records the techno-fueled raves and the lives of the travelers who organized them, but she started taking pictures primarily as a way of recording her own life, preserving her memories of the parties, memories which otherwise—as anyone who has danced all night will know—tend to become a bit blurry.

In the U.K., free parties grew out of the rave explosion of 1989, when crowds of up to twenty-five thousand people would gather in the English countryside for illegal all-night events fueled by MDMA and techno music. Although the primary impetus was hedonism, it developed into an exhilarating wave of mass civil disobedience in which Britain’s young briefly united and partied in defiance of the Conservative government, which throughout the 1980s had thrived on divide and rule. When the authorities finally realized this was a battle they couldn’t win and consequently relaxed restrictions on dancing and drinking, most of these revelers returned to the cities and to newly legal, all-night dance clubs. But a marginalized minority—with no jobs to fund expensive nightclubs, and a liking for the vagabond lifestyle—took to the road and continued putting on free techno parties in the countryside. They organized themselves as sound systems—a term taken from reggae music that encompasses DJs, rappers, huge speakers, and all of the technology needed to put on a party anywhere, indoors or outdoors.

Vinca Petersen, No System, 1999. Courtesy the artist

Petersen had become involved in this scene while still in her teens in London. She did some modeling and as a result met the renowned fashion and documentary photographer Corinne Day, whose work had reacted against the gloss and artifice of the 1980s by exploring a different kind of beauty: young and edgy, but also awkward and flawed. The raw, personal style of Petersen’s photographs fit into this new aesthetic, and Day encouraged her to make more, giving her protégée film and even cameras. In 1994, when new, draconian laws were passed to suppress free parties in the U.K., most of the sound systems Petersen knew fled to mainland Europe. She followed soon after, taking her camera with her, and remained on the road for nearly a decade. Everyone in the free party scene had their own stories, their own reasons for staying on the move, from ideology to a simple lack of money to a yearning for freedom. Petersen enjoyed the lifestyle: “I liked the earthiness of it all, and the traveling. I loved the practicalities, like finding somewhere to park for the night, finding water, going to a new supermarket to buy food, and cooking together. For me it was about a desperate need for community, I think.”

Life on the road wasn’t easy. They wandered through France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany, banding together with other sound systems to put on huge parties in remote countryside locations in the summer, then separating to seek out smaller, more urban venues, such as empty warehouses, when the weather got colder. The travelers played what Petersen describes as a constant game of cat and mouse with the police. As a result, they were wary of outsiders, especially those taking pictures. Cameras were routinely confiscated at parties, or film was removed. Of the few pictures by other photographers that exist of this scene, most were taken surreptitiously, and seem distant. Petersen’s images, by contrast, have been taken by an insider. Working with small, inconspicuous cameras, she sometimes didn’t even look through the viewfinder before clicking the shutter; other times she’d leave a camera on a bar overnight and retrieve it in the morning to see what had been recorded.

Vinca Petersen, No System, 1999. Courtesy the artist

The resulting pictures are intimate, warm, but also unflinching, celebrating the travelers without romanticizing them. Petersen shows the damage as well as the highs of drug use, the litter and destruction the travelers left in their wake, as well as the euphoria of their parties. It’s a time and place that already feels distant: a world without cellphones and distracting screens.

Petersen’s fellow travelers often criticized her for hiding behind a lens, saying that it stopped her from being fully present in the moment. “A photograph, especially if it’s not a digital one,” Petersen remarks, “is a recording of the moment for another point in time. I used to struggle with that. But then over the years, of course everyone started asking me for copies.”

Eventually she put together a book, No System (1999), going back on the road for another year in order to obtain permission from everyone featured before it was published. A second edition is due out this fall, and Petersen hopes that a new generation will see her pictures as a guide to an alternative way of life.

To read more, buy Aperture Issue 224, “Sounds,”or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Sheryl Garratt has edited The Face and The Observer Magazine, and documented the rise of rave culture in her book Adventures in Wonderland: A Decade of Club Culture (1998).

The post No System appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 1, 2016

Noisy Pictures

What does a photograph sound like? In this sonic sequence, a group of leading curators, writers, and historians reflect on images that won’t stay quiet.

Robert W. Kelley, Teenagers screaming and yelling during Elvis Presley’s personal appearance at the Florida Theatre, Jacksonville, FL, August 1956 © the artist/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

They’re on their own Tilt-a-Whirl. The sound coming out of their mouths is deafening. There is so much spinning movement in the picture that the fact that you actually can’t hear anything, because you’re looking at a photograph, can feel like proof that the sound they’re making has overwhelmed your senses.

— Greil Marcus, music journalist and cultural critic

Wojciech Zamecznik, Light drawing, study for the design of an album cover, 1963. Courtesy the Archaeology of Photography Foundation

Light shining in black on a white ground; black circles, which leave a white trace on paper—transformations that Zamecznik developed to create a visual equivalent of contemporary music. Two great passions of this architect and graphic designer meet: music and photography, which, in dialogue with graphic design, became his trademark. What can we see under half-closed eyes while listening to Penderecki, Lutosławski, or Bacewicz? A thing becomes its opposite, a single line transforms into fog, a sequence of rhythms.

— Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, Curator of Photographs, Centre Pompidou

Harold E. Edgerton, Antique Gun Firing, 1936. Courtesy Palm Press

Science during wartime changes art during peacetime. Such is the history of the electronic strobe light in the hands of artist-engineer Harold E. Edgerton, who made iconic photographs of bullets caught in midflight, bursting balloons, and exploding apples. The art and science of depicting loud, noisy, and murderous booms and bangs was Cold War business at its best—and Antique Gun Firing was a quaint prelude of what was to come. New cameras developed by Edgerton’s defense-contract company EGG would permit us to see some of the first hydrogen bomb explosions, not as deafening and deadly but as silent and cold.

— Jimena Canales, Thomas M. Siebel Chair in the History of Science, University of Illinois

Eliot Porter, Spotted Towhee in Flight, Tesuque, New Mexico, March 1952 © Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, and courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

“The camera offers a way of sublimating the indefinable longing that is aroused in me by close association with birds,” Eliot Porter once said. Sublimate: from the (medieval) Latin limare, to polish or perfect. Perfection must have meant stillness to Porter. That stillness mutes his scenes of woodlands and water, invariably enveloped in a deathly hush. Porter’s bird pictures convey instead the thudding whisper of air currents beaten into eddies by outspread wings. What Porter longed to possess, I imagine, is avian alertness. I can conjure that attentive state not by what I see—too fully or easily—but by the whoosh I almost picture myself hearing.

— Matthew Witkovsky, Curator and Chair, Department of Photography, the Art Institute of Chicago

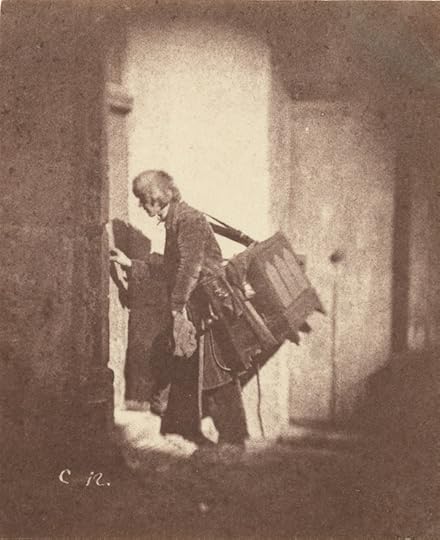

Bruno Braquehais, National Guards and Communards at the Vendôme Column, 1871 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Chantons la liberté, / Défendons la cité! Deaf photographer Bruno Braquehais did not hear the special version of “La Marseillaise”—or the gunfire—that punctuated preparations for the destruction of the Vendôme Column in Paris on May 16, 1871. His picture exudes a dreadful silence that portends the suppression of the Commune during the Bloody Week that commenced five days later.

— Stephen Pinson, Curator, Photographs, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Andreas Feininger, The Light Trail of a Helicopter, Anacostia Naval Air Station, Washington, D.C., February 1949 © the artist/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

Andreas Feininger sketches in the darkness using the light-tipped wings of a U.S. Navy helicopter. It’s a slinky tipped over the stairs by a three-year-old. It’s a single note, holding steady, wavering down to a flat, then ascending through the scale in joyous uplift. It’s a drone whose timbre changes, resonating first in your ear then in your chest. Light becomes line becomes sound, all in the space between eye and mind.

— Brian Sholis, Curator of Photography, Cincinnati Art Museum

Man Ray, The City, 1931 © Man Ray Trust/ARS, New York/ADAGP and courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The City—one of ten photogravures that Man Ray produced for a portfolio commissioned by La Compagnie Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité to promote domestic uses of electricity—pulses with energy. An illuminated Eiffel Tower is overlaid with neon advertisements, creating a visual cacophony of “voices” that compete for our attention.

— Virginia Heckert, Curator, Photographs, the J. Paul Getty Museum

Hatakeyama Naoya, Blast, 2005 © Naoya Hatakeyama and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Confronted by Hatakeyama’s Blast, I can’t help but imagine the deafening explosion of dynamite that sent this barrage of limestone hurtling toward us and the impenetrable ear-ringing silence left in its wake. Blast is part of a series that traced the journey of limestone from quarry to cement works to Tokyo towers.

— Malcolm Daniel, Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Charles David Winter, Éclair électrique produit par l’appareil de Ruhmkorff, ca. 1865. Courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg

Crackling with potential, capturing a discharge equally capable of initiating life or dealing death, this photograph from about 1865, by French photographer Charles David Winter, records a spark of electricity generated at high voltage. An image much like this one was chosen by André Breton as an example of automatic writing to illustrate his essay “Beauty Will Be Convulsive,” published in the Surrealist magazine Minotaure in 1934. Here, science and art join forces in a cacophony of elemental visual static.

— Geoffrey Batchen, author, most recently, of Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, 2016

Unknown photographer, Musical instrument from French Guiana, ca. 1910s. Courtesy Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

This instrument, from French Guiana, is made from part of a calabash and three strings or cords. Henry Balfour, in The Natural History of the Musical Bow (1899) discusses the musical bow as being derived from the archer’s bow, a weapon of war: “We need not even despise the time-honored legend of the invention of the zither or lyre by Hermes, and we may still give to the son of Zeus and Maia due credit for originality in having discovered latent musical qualities in the sinews of a dead tortoise, stretched, in drying, across the animal’s carapace.”

— Philip Grover, Curator of Photograph and Manuscript Collection, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

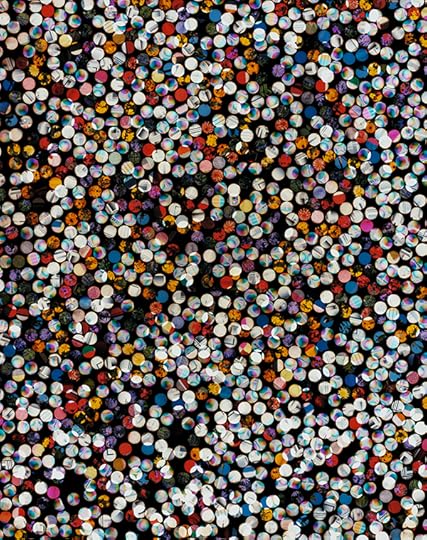

Jason Evans, There Is Love in You, 2009. Courtesy the artist

Color spectrums, flowers, and fine grids. Digital labs use such images to test their printers. Jason Evans gathered some, pinned them up, photographed them on color film, hole-punched the film, arranged the tiny disks on glass, put the glass in a photographic enlarger, and made a C-print. It’s the cover of Four Tet’s 2010 album There Is Love in You. A digital/analog image for electronic/analog music.

— David Campany, author, most recently, of Adventures in the Lea Valley, 2016

Suzanne Dworsky, Sea Breeze, Cape Cod, MA, 1978 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

While its title, Sea Breeze, conjures one specific sound, this picture suggests many others. They are faintly in the background, but just as vivid. There might be waves breaking, seagulls crying, and children’s voices. We are so close that there is also her breath. And overall, the indescribable sound of sunlight.

— Martin Barnes, Senior Curator, Photographs, the Victoria and Albert Museum

Al Vandenberg, Untitled, from the series On a Good Day, ca. 1980 © Al Vandenberg and courtesy Tate

Al Vandenberg’s series On a Good Day was made in Notting Hill in West London in the mid-1970s. His pictures look super cool in retrospect, and none cooler than this totally stylish girl with her portable cassette player. Music lovers of this generation will remember these things, how they sounded, and how quickly the batteries ran out!

— Simon Baker, Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), Tate, London

Christian Marclay, Untitled (R.E.M. and Sonic Youth), 2008. Courtesy the artist, Paula Cooper Gallery, and White Cube

Despite the title, the sounds that emanate from this picture are not the wailing chords of the eponymous rock bands. Whatever music was recorded on those magnetic tapes left no trace in Marclay’s cameraless cyanotype. Instead, it is the cracking of the plastic cassettes, the yanking of the tape, and the rustling of debris that still resonates. In a word: noise.

— Noam M. Elcott, Associate Professor, Department of Art History

To read more, buy Aperture Issue 224, “Sounds,”or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Noisy Pictures appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 30, 2016

The Getty Sheds New Light on the Early History of Photography

Gustave Le Gray, Mollien Pavilion, the Louvre, 1859. Albumen silver print. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

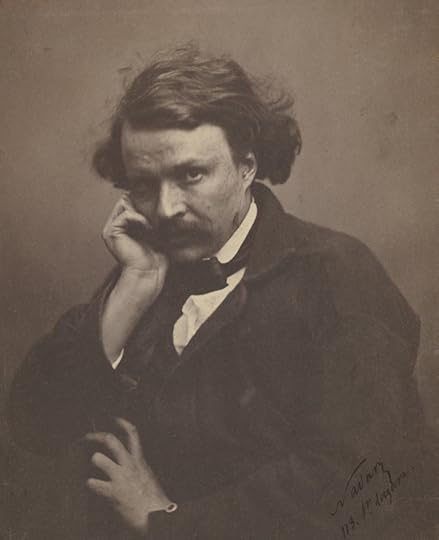

The Getty Museum’s new exhibition Real/Ideal: Photography in France, 1847–1860 delves into the early history of photography at a moment when French photographers were making enormous strides in developing the medium’s technical and aesthetic possibilities. Drawn largely from the Getty’s significant collection of nineteenth-century photography—including an important recent acquisition of thirty-nine works of French and British photographs—Real/Ideal presents the work of four photographers: Édouard Baldus, Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq, and Charles Nègre. In advance of the opening, Nicholas Robbins spoke with Karen Hellman, Assistant Curator in the Getty’s Department of Photographs and the organizer of Real/Ideal, about the genesis and themes of the show.

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon), Self-Portrait, ca. 1855. Salted paper print. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Nicholas Robbins: How did the idea for Real/Ideal come about?

Karen Hellman: I’ve always been interested in the idea of realism, in art and in literature. The era of realism in the mid-nineteenth century was an extremely important period in photography, following the “invention era” (1830s to the mid-1840s), but preceding the moment when more systematic and commercial means (paper, format, negatives, cameras, and lenses) became common in the 1860s. In her catalogue essay, Sylvie Aubenas calls the moment an “interregnum.” I’m also interested in questions about photography as opposed to other art forms. In mid-nineteenth-century France, photography was developed and debated as an art form at the same time that the realist writers and painters, such as Balzac and Jean-François Millet, were creating novels and canvases dealing with contemporary protagonists, whether Parisians or farmworkers. Such approaches to representing life seemed like the right framework for this exhibition.

Robbins: Given the Getty’s rich holdings of work from this period, I imagine it was difficult to edit the selection of photographs for the show. How did you choose to organize the show—thematically, or by maker?

Hellman: It was challenging to edit the selection for the show because it couldn’t be a comprehensive survey of the period—there were many photographers working at this time who were exploring the medium before there were established practices. To select four photographers that the Getty holds in depth was a way to compare four different approaches to the same subjects. For example, Baldus and Nègre both photographed the Cloister at St. Trophime in Arles, but while Baldus experimented with using multiple negatives to gain a wider perspective of the medieval corridor, Nègre photographed a vertical slice of the cloister with a greater interest in the dynamics of alternation between light and shadow than in a comprehensive view.

Charles Nègre, Tarascon, 1852. Waxed paper negative. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Robbins: I’m excited to see that the exhibition includes a number of paper negatives, which were part of a recent acquisition by the Getty. What drove the museum to bring these negatives into the collection? And how does seeing the “positives” with the “negatives” change our experience of the images or our understanding of their technical innovations?

Hellman: Negatives have, particularly in more recent years, been given short shrift in photography studies even though they were some of the earliest forms of photography. It’s harder to look at and read a negative image—we have to work a little harder to understand it—rather than the relatively straightforward ways we read the positive image. But I think that’s a good thing. The negative is an essential part of the history of photography and it is important for museum collections, particularly a collection like that of the Getty Museum, which holds a great deal of early photography, to recognize this and to preserve early paper negatives.

Charles Nègre, Organ Grinder at 21, quai Bourbon, Ile Saint-Louis, Paris, ca. 1853. Salted paper print from a paper negative. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Robbins: The exhibition has a compelling historical frame—looking at the paper negative’s invention and popularity between 1847 and 1860, a period of great social and political change in France. How do political and social histories, whether the revolutions of 1848 or the policies of Napoléon III, enter into the photographs? Or into the projects these photographers undertook?

Hellman: Nothing historically, artistically, or photographically works within perfect frames, of course, but this period in photography and in France was one that seemed to provide a good structure for a general audience to consider photography in a particular way. Political and social histories do and do not enter into these photographs. The photographic processes were too slow to create the photo-journalistic documents of, for example, the revolutions of 1848 in the way we are used to today. What I find interesting is that photographers of the 1850s explored many of the same social subjects as realist painters and writers—mostly because they had to. Those were the people around them or on the street, in quiet city squares, or in farm scenes. They also photographed the great historical architectural monuments of France for patrimony and were commissioned, under both the Republic and the government of Napoléon III, to photograph honorific views of France and French architecture. So they were capturing both the real and the ideal and in both endeavors they had great challenges to overcome.

Gustave Le Gray and Auguste Mestral, West Facade of the Cathedral of Saint-Gatien, Tours, 1851. Waxed paper negative. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY