Aperture's Blog, page 95

November 29, 2018

The Spirits of Fire Island

Matthew Leifheit conjures history and fantasy in the fabled gay enclave.

By Will Matsuda

Matthew Leifheit, Adam, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Fire Island, the legendary barrier isle that hangs precariously off the southern shore of New York’s Long Island, is a place where the past mingles with the present, where desires and bodies blur with the pounding surf. For his recent exhibition Fire Island Night, Matthew Leifheit walked for miles—the island has no cars or paved roads—to make his haunting compositions of men amid dark dunes. Or he stayed in, posing his subjects in repose in a clothes-optional Cherry Grove hotel. I recently spoke with Leifheit about the fantasies of Fire Island, unexpectedly living in a cottage where Peter Hujar and Paul Thek spent time in the 1970s, and preserving gay legacies against a shifting landscape.

Matthew Leifheit, Cherry Grove, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Will Matsuda: What led you to make Fire Island Night? Did it feel urgent?

Matthew Leifheit: Fire Island is a landscape in transition. It changes with the tides, and it’s changing with climate change. The island represents a gay history and a culture that is also in transition. Often, photographs that I love encapsulate the past and the present. I want these photos to do that as well.

My past work has always included historical materials because of my background; I’ve worked as a photo editor, which includes image research. While I was on the island, I started finding these pottery shards on the beach, which I’ve included in the show. I think about the work as a collection of fragments edited into a sequence.

Matthew Leifheit, Gabe, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Are you thinking about this as a documentary project? A fantasy? An escape?

Leifheit: I hope it’s all three. Guy Maddin, the Canadian filmmaker who did My Winnipeg, uses the word “docu-fantasia,” which I like. My friend Susan Howe calls it “factual telepathy,” which is an idea that archival facts from different points in time and place can talk to each other. I’m interested in the idea of poetic documentary. I think poetry is often a way to get closer to the truth.

Fire Island holds this cultural fantasy associated with gay culture. A friend, who recently transitioned to become a man, described a trip to the island as a “gay rite of passage.” It’s an escape because queer people can go there to express themselves when they can’t in straight society. But I’m interested in that idea now because more often people don’t have to go to geographical extremes to express their sexuality. Hopefully not in New York. So I’m asking, what is the role of this place? And how will it change?

Matthew Leifheit, Gustavo, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: And what is the role of these pictures in this cultural transition? Your photographs appear to be all of men, and I’m wondering how you frame this as our notions of gender and queerness are expanding?

Leifheit: I don’t want to speak for people, but yes, almost all the pictures in the show contain male-identified subjects. But I think I’m not necessarily making that look like a good thing, and hopefully that’s evident in the way I am looking at the place photographically. The series is also a dramatization of the world that exists there. I have exaggerated its homosocial qualities. Still, I hear it called an “only space,” which I take to mean an exclusive space where people of a particular marginalized group such as gays can be the vast majority rather than the minority, the rule instead of the exception. Historically for our community that kind of space has been essential, and in my opinion it still is. But now that people are having less use for gender boundaries, or would rather define their sexuality as queer, rather than gay or straight, what will the legacy be of this place that we are inheriting?

The artist Barbara Hammer recently established a grant for lesbian experimental filmmakers. I went to hear her give a talk and during the Q&A, I asked her about the purpose of a lesbian-only grant in a world where people are having less use for these kind of exclusive terms. She said something like, “There is a slippage now, absolutely, but in the slippage I don’t want a group of people to be lost. I want the tradition and the culture of being a woman-identified woman to continue in artwork as well as in history. It’s a different culture than a queer culture. It’s a different culture than a gay male culture . . .” She talked about specifically wanting to preserve a history of butch lesbians, and I appreciated that.

I think that a lot of the history that I’m talking about here, although not all of it, is a history of fags. It’s not necessarily queer by nature, because it has been an exclusive place. Fire Island is rumored to be this place only for muscle gays and advertising executives, but I think that was another time. Alongside the island’s history, I am trying to show the world that exists there now. There’s a wider range of people.

Matthew Leifheit, Ivy Walk, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: What drew you to Fire Island originally?

Leifheit: I first went to Fire Island in 2014 for a VICE story about underwear parties. Part of the reason I fell in love with it was that it represented this world that I didn’t really know existed. I had read about what it was like in the ’70s before the beginning of the AIDS pandemic. I was fascinated and excited to see that these parties with back rooms and wild group sex still existed. Since I first went there, PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] has become much more widely used, which is amazing. It has also brought on a new permissiveness. People are willing to have riskier sex and more sex, as I perceive it. I think that is really exciting because the AIDS crisis silenced the voices of so many great minds, ending for many this era of extreme creativity, what seems to have been an amazing time where people finally had some sexual freedom. I think that with the rise in PrEP use, there’s been a revival of this hedonism on Fire Island. Maybe it never left.

Matthew Leifheit, Ice Palace IV, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: I recently read a piece about the resurgence of Symbolism, a movement in the late nineteenth century where artists, poets, and writers were pushing back against Realism and responding to a chaotic world heading towards war as well as rapid technological acceleration. The work is otherworldly, moody, erotic, and it’s pretty morbid. It’s not hard to compare that historical moment with ours. Do you think Fire Island Night has any relation to this?

Leifheit: Oh, I like that. I do see these photographs as symbols that I’ve arranged into sentences of sorts. I believe that beautiful form has the potential to comfort people in times when it seems like the world makes no sense at all. The fact that the chaos of the world can be organized in a way that is beautiful and makes sense in a photograph can be very powerful, and it can give people hope. There are certainly other more direct ways of being an activist in your work, but I do believe that beauty is essential, and can be an escape. Earlier you used the word urgent, and I think that this is an urgent thing to show. At this particular moment, it’s of the utmost importance.

I had received a grant to research George Platt Lynes’s love letters and his scrapbooks leading up to World War II. The scrapbooks contain a lot of imagery that I’ve nearly re-created in some of these photographs. He posed for PaJaMa [Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret Hoening French] on Fire Island in these dark surrealist images. I don’t know if you would call it Symbolism, but Lynes was combining images of the male form with death on the battlefield and drownings. Photography is inherently mournful, we know. I do a lot of portraiture and I can’t help but think about the subject’s inevitable death.

I want to show how things wear away. Fire Island is almost a sandbar. It’s a barrier island that changes with the tides. I felt extremely exposed to the elements while I was there, living in a shack in the woods where Peter Hujar and Paul Thek used to go in the ’70s.

Matthew Leifheit, The Spiral Staircase, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Wow . . . really?

Leifheit: My friend Marcell Yáñez, who wrote a thesis on Hujar’s circle, heard that there was this town in the middle of the dunes on the island where Thek and Hujar went in the ’70s. Susan Sontag, Vince Aletti, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono, too. It was this really remote place with artists and writers. It’s only maybe ten houses. Marcell had heard that Paul Thek had made lifecasts of his body on the island and had left pieces of himself around the town. Some neighbors had found a hand with a bunch of extra fingers. So we went looking for body parts there, and it turned out there was a house available for the summer. I spoke with the person who owned it, and their mother had rented to Hujar and Thek in the ’70s and liked the idea of an artist being there.

Weirdly, the cottage is right across from the death site of Margaret Fuller, who wrote America’s first major feminist work. It’s this low spot on the beach where things are always washing up. There was one point when a funeral wreath washed up right in front of me. There were also prayer balloons that came in from Long Island, I think. People had written the names of their loved ones on them and they drifted to this spot. History was really on the surface there.

Matthew Leifheit, Cleophas, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: How did living in that space affect this work?

Leifheit: Hujar is one of my favorite artists. Hujar waited until his subjects showed their truest form, whether they were a cow, a person, or a rock. It’s a process of waiting for a signal, of receiving. It’s the opposite of the way people think of Magnum photography. Until the commercialization of photography, photographs were not talked about as being “shot” or “taken.” All that photographic materials are capable of doing is receiving. In that way they are, like, inherently bottoms [laughs].

In preparation for a class I’m teaching at Yale, I read Kaja Silverman’s The Miracle of Analogy (2015), which is about the invention of photography. She quotes the part of Walter Benjamin’s Little History of Photography (1931) about long exposures in old portraits causing the subject to “focus his life in the moment rather than hurrying on past,” thereby capturing more of the sitter’s essence or aura or something. I’ve been working with longer exposures lately.

Peter Hujar worked in this way—its anti-aggressive. It’s empathic. I would like to be that way towards humans, but also towards the landscape. This is the first time I’ve ever photographed landscapes before, or even really been outside in this way. It’s amazing how you have to wait for the landscape. I had to wait for a supermoon for it to be bright enough for a photo. You have to wait for the mist to be in the air so that the light spreads in the right way. I also spent a lot of time trying to photograph that flash of blue light that happens after the sun goes down in the summer, just before darkness.

Matthew Leifheit, Mohamed, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: Taking a step back from this work, you recently graduated from Yale; you spent the summer on Fire Island, and now you’re showing this work in Brooklyn. What’s next?

Leifheit: Since graduating in 2017, I spent the last year teaching as an adjunct at four different schools, which was wild! It was too many classes to take on but I learned a lot. I spent a whole summer and probably the next six months making color studies. I photographed a million sunsets. When I graduated school I just needed something nice to do. I thought, maybe I’ll just do sunsets in Kodak Gold and it will be about, like, the death of analog or something. Eventually I woke up and realized I made a bunch of ombré gradients. It was so bad. You have to go through those phases, though.

Matthew Leifheit, Wave (Hudson and MeHow), 2018

Courtesy the artist and Deli Gallery, New York

Matsuda: You really do.

Leifheit: I just finished production on my first documentary, but it’s really more of an erotic docu-fantasy, like we were talking about earlier. It’s about George Platt Lynes’s love letters. And I just started a second film about a female impersonator who lost his voice on stage one night in 1982. It’s about the absence of his voice. I’m going to do a residency in Oaxaca this winter to start editing that documentary.

I’ve worked as a photojournalist and that’s so fast, but this video work has been slower. Film editing is exciting to me because I can just keep doing it forever. I’m going to continue working on these photographs of Fire Island this winter, as well. Eventually I want to publish them in a book, whenever it’s ready.

I’m just going to keep my work alive. I saw this TV interview with Harry Callahan from the ’80s where he said, “I felt that what I had to do was to live strongly, and to keep my photographs alive. As a result, I would have a lifetime of experience, from beginning to end.” That’s the only way I know how to proceed. I used to think I would die young but now I think I might outlive everyone, just lingering around and taking photographs while people and things slip away. I just want to make a masterpiece before I go.

Fire Island Night is on view at Deli Gallery, Brooklyn, through December 2, 2018.

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer based in New York.

The post The Spirits of Fire Island appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 20, 2018

On the Cover: Aperture’s “Family” Issue

Liz Johnson Artur, Johnny’s wedding guests, London, 2002

Courtesy the artist

Since the early 1990s, Liz Johnson Artur has been photographing individuals of the African diaspora throughout London, Kingston, Brooklyn, and beyond, capturing moments of joy and community in a colorful, intimate style. The cover of Aperture’s Winter 2018 issue, “Family” is a collage by Johnson Artur featuring a photograph from 2002 overlaid on a page of braille text. “Johnny Sapong invited me to his wedding,” Johnson Artur told Aperture. “It was a Ghanaian–English wedding. I took my camera with me. There was a tent in the garden for the ‘official’ photographer to take formal pictures. I took this picture while the couple were getting ready for the ‘formal’ picture.”

Johnson Artur frequently collects her images into notebooks and workbooks, and sometimes incorporates these materials in the presentation of her archives, including the picture of Johnny’s weddings guests. “Many years ago, I found an Iris Murdoch novel in a charity shop,” she said. “It was printed in six large braille volumes. I have been using them ever since to put words and pictures closer together.”

The family portrait, in all of its permutations and possibilities, is about making history. Aperture’s “Family” issue, which includes photography and writing by David Armstrong, Tammy Rae Carland, Masahisa Fukase, Justine Kurland, Diana Markosian, Lynne Tillman, Stefan Ruiz, John Jeremiah Sullivan, and Deborah Willis, also features a profile of Liz Johnson Artur by the London-based curator and writer Ekow Eshun. “What I do is people,” Johnson Artur said. “But it’s those people who are my neighbors.” At first, Johnson Artur didn’t see those lives represented anywhere. So, like many of the photographers in this issue, she pictured them herself. She made a world and a family of her own.

Read more in Aperture 233, “Family,” now available for pre-order.

The post On the Cover: Aperture’s “Family” Issue appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 14, 2018

Fashion, Politics, and the Black Imagination

Theaster Gates revisits the legendary archives of the Johnson Publishing Company.

By Violaine Boutet de Monvel

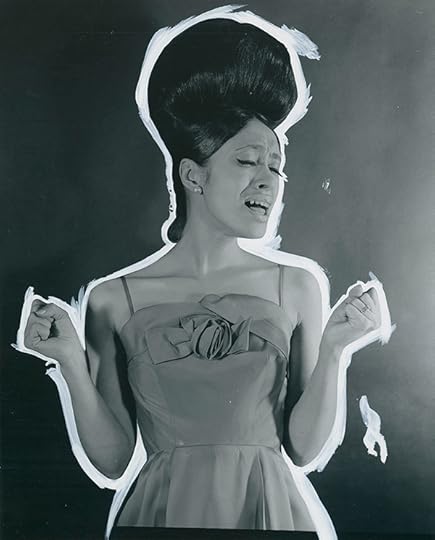

Isaac Sutton, Untitled, 1965

Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company

In 1942, when John H. Johnson founded the Johnson Publishing Company, the national press in the United States hadn’t made much space for addressing the lives of black citizens in a proactive way. Life magazine was really more about white life. Starting with the monthly Ebony and its weekly sister Jet, created in 1945 and 1951 respectively, Johnson’s magazines were designed to fill the void left open by institutionalized racial segregation. A void creates an opportunity, and the renowned Chicago-based publishing house would cover and celebrate, over the next seventy years, the breadth and wisdom of African American culture, eventually becoming one of the most influential black-owned businesses in postwar America.

In addition to the distinct upbeat tone and entrepreneurial spirit that Ebony and Jet cultivated through news, entertainment, and fashion coverage, as well as their plethora of critical essays regarding African American history and achievements, the magazines are notable for having thoroughly chronicled the nascent civil rights movement from the early 1950s on. At the same time, the Johnson Publishing Company also launched the Ebony Fashion Fair, an annual show that ran for five decades and featured black female models across the United States, as well as the eponymous brand Fashion Fair Cosmetics, which still exists to this day.

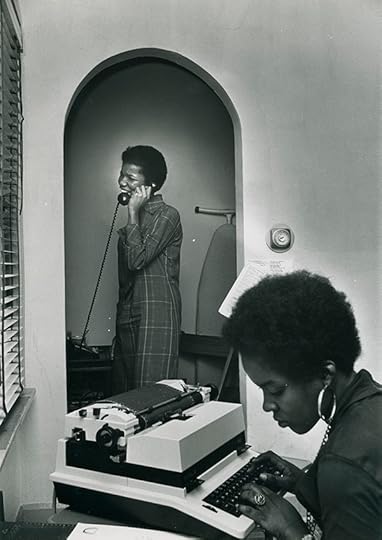

Isaac Sutton, Untitled, n.d.

Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company

With print media finally giving in to the digital world in the early 2010s, Linda Johnson Rice—the heir and current CEO of the Johnson Publishing Company—sold Ebony and Jet in 2016 to concentrate the whole business on the cosmetics line. She has nevertheless preserved and made available to the public the photo archive of her parents’ former press empire: approximately four million images documenting African American life since the mid-1940s, the vast majority of which have never seen daylight.

This exceptional profusion of black images is the starting point of an exhibition and publication conceived by Theaster Gates for the Osservatorio of the Fondazione Prada in Milan, The Black Image Corporation. It touches upon notions of beauty, power, and the diversity of blackness through the work of two African American press photographers in particular, Moneta Sleet Jr. (1926–1996) and Isaac Sutton (1923–1995), who were once employed by the Johnson Publishing Company.

Moneta Sleet Jr., Coretta Scott King and Bernice King practicing the piano and violin, Atlanta, 1972

Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company

Born in 1973, Gates, a Chicago-native artist and urban planner, has gained international recognition for his multifaceted, often-collaborative practice committed to social change. Deploring how the African American community is still too often reduced into a mere handful of negative stereotypes, he decided to focus on beauty through the lenses of Sleet and Sutton. “They both had the responsibility of fashion and politics,” Gates told me in September. “They could shoot a fashion show during the day, and join a political rally at night, so in some ways, I think they were both using fashion to be political.”

From over twenty thousand photographs by Sleet and Sutton, Gates selected 366 for The Black Image Corporation, whose title is a direct nod to the Johnson Publishing Company’s crucial role in giving black excellence a visible outlet. “While it’s probably the simplest presentation I’ve ever done, the hardest part was deciding the images,” he noted. Scattered on two light tables at the entrance of the Osservatorio, 120 contact prints of original transparencies and photo films represent the enormity of the task. Visitors are invited to handle them with a pair of white gloves and illuminate what they wish. Ebony and Jet’s art directors used such materials to review countless pictures from photo shoots, only to publish but a few. This participatory display thus offers a subtle mise en abyme of both the editorial work that went into the conception of the magazines, as well as the curatorial work factoring into this exhibition.

The Black Image Corporation, 2018. Installation at the Fondazione Prada Osservatorio, Milan

Courtesy Fondazione Prada

Instead of a traditional exhibition catalogue, Gates has conceived a box set in collaboration with the Fondazione Prada. It contains a booklet with an essay, and the entire collection of 366 photographs in the form of double-sided cards, which can be taken out and hung with a fastener on the box; the gesture recalls an action that visitors are also encouraged to do at the Osservatorio, where a third of Sleet and Sutton’s selected work is stored for viewers to pull from a series of four wooden cabinets. “It would be lovely just to present all the photographs on the walls, but if you want to see them, you have to work. These cabinets function like a sanctum and what I hope,” Gates said, “is that there will be an intimate encounter with the images.”

In the absence of any official cataloging from the Johnson Publishing Company, Gates assigned to all the selected photographs by Sleet and Sutton a number from 1 to 366, and created six archival codes to characterize their subjects, without further identifying or contextualizing them apart from the photographer’s name and the year of realization: MDL for model, EDP for everyday people, ENT for entertainer, PRO for professional, M&C for mother and child, and FEI for female impersonator. While fashion photography and model headshots count for more than half of the ensemble, the other categories prompt viewers to question the notions of beauty beyond glamour. “What I want to convey through these images is perhaps a sensitivity to the power of everyday women to be both beautiful and maybe world-changing,” Gates noted.

Moneta Sleet Jr., Martin Luther King Jr., surrounded by his family, holding the Nobel Peace Prize medal, 1964

Courtesy Johnson Publishing Company

Unfurling throughout the selection, Sleet and Sutton’s avalanche of beauty and power includes a model sporting a sleek bob haircut with a Mondrian cocktail dress (68 SLEET 1966 MDL); a drag queen parading with sweat pearl headgear and a little black purse (43 SUTTON N.D. FEI); Ann Lowe flaunting her legendary top hat (126 SLEET 1966 PRO); Eartha Kitt posing in a swimsuit at the pool (48 SUTTON N.D. EDP); and last but not least, Martin Luther King Jr. surrounded by his wife, Coretta, and his family, holding the Nobel Peace Prize medal that he had just been awarded (176 SLEET 1964 EDP). Sleet was later awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his picture of Coretta Scott King at her husband’s funeral, following King’s assassination in 1968.

The presentation of all these individuals, whether iconic or not, in complete anonymity and therefore in equality—particularly before a European audience, who may be less familiar with African American culture and history—is very humbling. The Black Image Corporation poses no hierarchy, but allows for the young models who won the “Beauty of the Week” contest of Jet magazine to count as much as King himself, no matter how well- or little-known their respective contribution to this world is. As Gates concludes in his essay for the booklet that accompanies the exhibition, “Black is Beautiful. Black is Enterprising. Black is complicated and … I hope this set of images offers us all blank pages for the formulation of a new atlas.”

Violaine Boutet de Monvel is an art critic and translator living in Paris.

The Black Image Corporation is on view at the Osservatorio of the Fondazione Prada, Milan, through January 14, 2019.

The post Fashion, Politics, and the Black Imagination appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 13, 2018

Carleton Watkins and the Image of Manifest Destiny

In his new book, Tyler Green considers a pioneering photographer of the American West.

By Maika Pollack

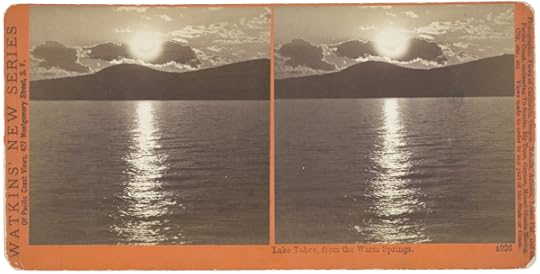

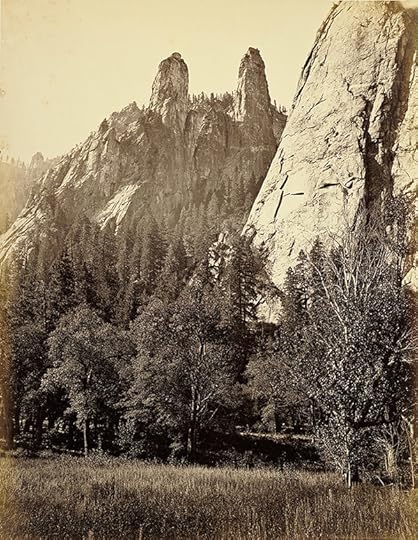

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley from the Best General View, 1865–66

Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum

I’ve always been curious about Carleton Watkins. Manifest Destiny personified, his collodian landscapes extended the Wheeler and King surveys, post-Civil War expeditions that photographed the American West, to the very shores of the Pacific. But there is also something transcendent to Watkins’s pictures of Yosemite. They have absolutely no visible grain; they are lush, immersive, even prescient, creating as much as capturing Northern California. His Lake Tahoe, from the Warm Springs (1878–1882)—all shining lake contained by rolling black hills—seems to contain the spores of a Northern California yet to be, the roiling sublimity of Allen Ginsberg or the Grateful Dead. Much like other entrepreneurial American photographers of the nineteenth century (Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner), Watkins opened his own gallery, the Yosemite Art Gallery, in San Francisco to sell his work to the public. Unlike them, though, his photographs were also sold by Goupil & Cie, the Parisian art prints dealer, at an age before photographs could stake much claim as high art. What was going on?

Carleton Watkins, Lake Tahoe, from the Warm Springs, 1878–1882

Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

Mainly thanks to the destruction of Watkins’s records—along with nearly everything else in San Francisco—wrought by the massive earthquake of 1906, Tyler Green’s new book Carleton Watkins: Making the West American is not a biography. Although Watkins’s life, like that of many commercially successful nineteenth-century photographers, is a rags-to-riches-back-to-rags story (it’s still surprising Rebecca Solnit’s 2003 book River of Shadows about the cinematic rapscallion Eadweard Muybridge hasn’t yet been made into a film), Watkins remains an enigmatic character in this account. What Green has done instead, with success, is to create a detailed picture of the intellectual geography of Watkins’s photographs. From the paintings of Albert Bierstadt to the Transcendentalism of Henry David Thoreau and the geology of Louis Agassiz, Green maps out the American scientific, financial, and artistic worlds Watkins worked within, and convincingly argues for his unique place in them. This book is a thoughtfully researched meditation on a photographer’s complex contribution to the formation of our national identity.

Carleton Watkins, Cape Horn, Columbia River, Washington Territory, 1867

Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum

Green, the pull-no-punches host and producer of the Modern Art Notes podcast, is a born skeptic, and as such he is wonderfully meticulous about his archival research. Watkins’s work, unlike Timothy O’Sullivan’s, was not government-funded. His commissions connect dozens of California’s oligarch founders, and Green’s deep dive into letters and contracts convincingly demonstrates how Watkins’s photographs contain within their grainless surfaces complex considerations of property, geology, capital, the politics of natural resources, and the ownership of water.

Yet Green is also a Watkins enthusiast, and out of love for the photographs he shows how Watkins’s own ambition went far beyond the task of taking pictures: “Detractors who, in recent decades, have argued that Watkins was a mere photographer in an era of painters, or that he merely made the pictures that were in front of him and thus gets credit for being there but not for doing anything special, must reckon with [his work],” he writes. That Watkins’s pictures of the natural landscape influenced John Muir and Frederick Law Olmsted’s conception of Yosemite National Park is well-known. But that the Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson hung Watkins’s Cathedral Spires (1865–66) and Mount Shasta (1867) in his living room in Concord, Massachusetts, next to a Julia Margaret Cameron portrait of Thomas Carlyle, tells volumes about Watkins’s intellectual context—and why his images are at once so precise and so otherworldly.

Carleton Watkins, Cathedral Spires, Yosemite, California, 1865–66

Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum

Green is engagingly technical, going into detail about exhibition practices (sequoia wood frames!), copyright issues (why you should never buy a Watkins print featuring clouds—it was probably printed by a competitor), sales practices, and the political and legal uses of photography during Watkins’s time. He unearths a gripping bit of his own family’s history in relation to a Watkins photograph; in the nineteenth century, a direct relative commissioned a Watkins. We learn that Watkins’s collodian plates were some of the largest negatives in the history of photography: one glass plate weighed four pounds and was 17 by 21 inches—no other analog method even comes close to the sheer information that contains. I would have loved a little more on Watkins’s darkroom technique. How did dodging and burning function with those mammoth glass-plate negatives? What might comparing different prints of the same photograph tell us?

Carleton Watkins, Mount Shasta, Siskiyou County, California, 1867

Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum

I found the book’s first chapter, about where Watkins was born, his early life before he became a photographer, and the history of Oneonta, New York, far from illuminating Watkins’s mysterious images of California, and I was highly skeptical of Green’s attempts to narrate what people in the past were thinking—this seemed to lend a needless “historical fiction” tone to the book’s earliest pages. Harvard photo scholar Robin Kelsey’s noted history of U.S. surveys is conspicuously absent from the bibliography, which seems an omission. But the book is convincing in its central argument, relating the sublimity of Watkins’s photography to American Transcendentalism, particularly the poetry of Emerson. It is also quite beautiful on the meanings of early Californian culture. In this sense Green’s research is not just about Watkins, but about the significance of the American West, and in some ways the definition of America itself. Ultimately, the book makes a strong case for photography as the first and most American art: much like Watkins’s work, Making the West American is at once technical and transcendent.

Maika Pollack teaches the history of photography in the MFA program at the Pratt Institute.

Carleton Watkins: Making the West American was published by University of California Press in October 2018.

The post Carleton Watkins and the Image of Manifest Destiny appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 9, 2018

Announcing the Winners of the 2018 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of the 2018 edition of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. “The choices we made reflect the chaotic and changing world in which we are living,” said final juror Hervé Digne. “I think both the shortlist selection and the final award winners offer a window on the world at large and on the world of photography and photographic books today.”

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year

The Land in Between

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Publisher: MACK, London

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s The Land in Between was selected for providing a strong platform for interviews, portfolios, and essays about an artist less well-known outside of her native country. The minimalist, elegant design and form are well matched to the content, emphasizing what Batia Suter describes as “the artist’s sharp vision.”

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year

Laia Abril

On Abortion

Publisher: Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, UK

“In choosing Laia Abril’s On Abortion, the jury felt it was important to recognize a well-crafted statement on a topical and timely issue. The book offers a strong commentary on women’s reproductive choices, and uniquely visualizes the topic using archival imagery, contemporary photographs, and text.” —Azu Nwagbogu

Winner of First PhotoBook ($10,000 prize)

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

One Wall a Web

Publisher: Roma Publications, Amsterdam

“It’s a serious moment in history, and it felt urgent amongst the jury that we choose books that have gravity to them but also maybe a glimmer of hope, as in the selection of Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s One Wall a Web. This is a book that has complexity and embeds race in a larger narrative and a larger system—it demonstrates, if not a solution, at least a direction for further dialogue.” —Kevin Moore

Juror’s Special Mention

Pixy Liao

Experimental Relationship Vol. 1

Publisher: Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China

“In this current situation of post-#MeToo, and the ongoing debate around the binary opposition between the male and female gaze, Pixy Liao’s Experimental Relationship Vol. 1 is a very refreshing and blissful vision of intimacy, complicity, and collaboration between the sexes.” —Federica Chiocchetti

A final jury at Paris Photo selected this year’s winners. The jury included: Federica Chiocchetti, curator and founder of the Photocaptionist; Hervé Digne, president of Manifesto and the Odeon Circle; Kevin Moore, curator; Azu Nwagbogu, director of African Artists’ Foundation (AAF) and LagosPhoto Festival; and Batia Suter, artist.

This year’s shortlist selection was made by Lucy Gallun, associate curator in the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art; Kristen Lubben, executive director of the Magnum Foundation; Yasufumi Nakamori, PhD, incoming senior curator of international art (photography) at Tate Modern, London; Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review; and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

The shortlist was first announced at the New York Art Book Fair. The thirty-five selected photobooks are profiled in issue 015 of The PhotoBook Review, Aperture Foundation’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook. Copies will be available at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore. Subscribers to Aperture magazine receive free copies of The PhotoBook Review with their summer and winter issues.

The post Announcing the Winners of the 2018 PhotoBook Awards appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 5, 2018

Speak Loud and Embrace the Protest

In Los Angeles, an exhibition revisits the images and struggles of the Chicano Movement.

By Yxta Maya Murray

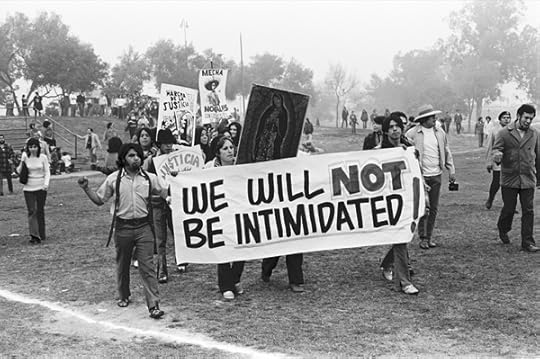

Luis C. Garza, La Marcha por la Justicia, Celia Luna Rodriguez (with mic) and Rosalío Muñoz (Chair of the National Chicano Moratorium Committee) at Belvedere Park, East LA, January 31, 1971

© Luis C. Garza and courtesy the photographer and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

An image of a Latina yelling into a microphone while raising her fist marks the entrance to LA RAZA, an exhibition of Brown Power photographs currently occupying the ground floor of the Autry Museum of the American West, with the boldness of a late-1960s Chicano Blowout. LA RAZA (“The Race”) celebrates the boundary-smashing photography of the activist newspaper and magazine of the same name, which was published in East Los Angeles from 1967 to 1977. In each of the exhibition’s thematic suites are stunning images of protesters waving signs that say Aztlán es mi Tierra, police officers aiming weapons into the infamous Silver Dollar Bar and Café, and the resplendent Latina demanding that her voice be heard.

Why is it shocking to see Brown history here?

La Raza staff, Deputy with shotgun at the ready, National Chicano Moratorium, East LA, August 29, 1970

© La Raza staff photographers and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

The Autry Museum has not always been first on the list of Latinx-friendly art venues. Founded in the height of the Reagan Era, the Autry is named after Gene Autry, the famous “singing cowboy” star of such history-erasing insults as 1939’s South of the Border and the 1940 classic Gaucho Serenade. The Autry’s nerve-rattling exhibits of Manifest Destiny romanticists like W. H. D. Koerner once earned the museum a boycott by the American Indian Movement in 2001: “Indians are not for sale,” AIM said.

Hope arrived in the form of the Autry’s current director, Rick West, who helped found the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), and is a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nation of Oklahoma. West has initiated a host of inclusive programs, including shows of Pomo basket maker Mabel McKay, Wiyot artist Rick Bartow, Chicano photographer Harry Gamboa Jr., and the Aztlán-tastic photo-feast that is LA RAZA.

Luis C. Garza, Youth from South Central LA arrive at Belvedere Park for La Marcha por la Justicia, January 31, 1971

© Luis C. Garza and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

A bit of digging reveals that the Latina yelling into the microphone is Celia Luna Rodriguez, the 1970s leader of the Barrio Defense Committee. The photograph, taken by Luis C. Garza, then a staff photographer for La Raza and now an independent curator who co-organized the show, is a heady mix of star-making charisma and community solidarity. Garza’s black-and-white image situates Rodriguez dead center, in the midst of an outdoor crowd; a film camera at the bottom left corner shoots out a ley line of pure energy that leaps toward Rodriguez and up to a few observers perched high on rooftops to see her better. This icon of Latina political leadership was culled for La Raza out of more than twenty-six thousand images that Garza, as well as Maria Varela, Pedro Arias, Manuel G. Barrera, Raul Ruiz, and others, took during the publication’s all-too-short run.

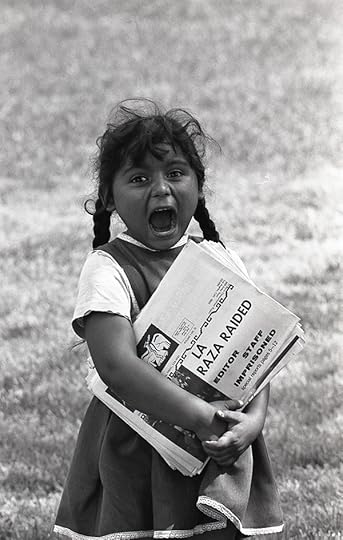

LA RAZA brings back all of those exciting and harsh memories from the late 1960s and ’70s, when Latinx students exited their LA high schools en masse in order to protest unequal education. On the Autry’s floor spreads a relic of what became known as “blowouts.” Visitors to the exhibition step over an enlarged copy of a photo of a sidewalk sprinkled with pine needles and the spray-painted phrase WALK OUT. Up on the walls, in both enlarged, back-lit images and black-and-white prints made from the original negatives, a bouffanted lady gets hauled off by a tall white man, next to a fallen sign reading Viva La Raza. A squad of brown-bereted women takes back the streets in matching trench coats and black pants. A tiny, hollering Chicanita in pigtails grasps copies of the newspaper, whose banner headline reads La Raza Raided.

Maria Varela, A young Chicanita hawks La Raza newspapers at the Poor People’s Campaign, Washington, D.C., May–July 1968

© Maria Varela

But it’s the photographs of the Chicano Moratorium March, which took place in LA on August 29, 1970, that really tear into old wounds. The march was led by Chicano rebels who protested the Vietnam War, but the peaceful walkers who set out from Laguna Park were met by hundreds of helmeted police from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s office. Soon, physical clashes between the activists and law enforcement sent shocks through the crowd, and the melee deteriorated into a frenzy of tear gassings.

Watching the fracas was Ruben Salazar, the Chicano columnist for the Los Angeles Times and a director of the Spanish-language TV station KMEX. Soon after, he retired to the nearby Silver Dollar Bar and Café. But a police officer shot tear gas canisters into the restaurant, and one hit Salazar in the head and killed him. In LA RAZA, images on display show the police attacking the poky-looking Silver Dollar. In one photograph, an officer aims his gun at two unarmed men, while two women hold up their hands in terror. Directly above it presides the last known picture taken of Salazar while he lived. He walks down a street crowded with marchers, wearing a white shirt and longish hair. You can barely see his face.

Pedro Arias, César Chávez (center) with United Farm Workers of America members, ca. 1970

© Pedro Arias and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

This image and the one of Celia Luna Rodriguez form two lodestars within LA RAZA’s constellation. The exhibition has been on view during a period in contemporary history that unfortunately recalls the era of the Autry’s origins, as the current president of the United States characterizes Latinos as drug dealers and rapists, police killings of Black people continue to traumatize people of color and result in scandalously low conviction rates, and Trump now threatens to end birthright citizenship through the illegal means of an Executive Order. In such a climate, it’s hard not to feel dragged down by your losses. It’s better, though, to follow the lead of Rodriguez, as pictured so beautifully by Garza, and the exemplars of the other La Raza photographers and their subjects: we have to embrace our struggle and speak out loud our protest.

Yxta Maya Murray is Professor of Law at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, and a contributor to Aperture, issue 232, “Los Angeles.”

LA RAZA is on view at the Autry Museum, Los Angeles, through February 10, 2019.

The post Speak Loud and Embrace the Protest appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 2, 2018

She Captured the Face of Modern Iran

Remembering the life Shirin Aliabadi, whose photography provided a sharp commentary on the lives of Iranian women.

By Haleh Anvari

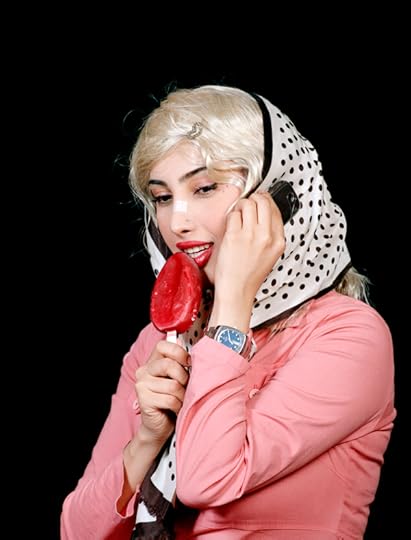

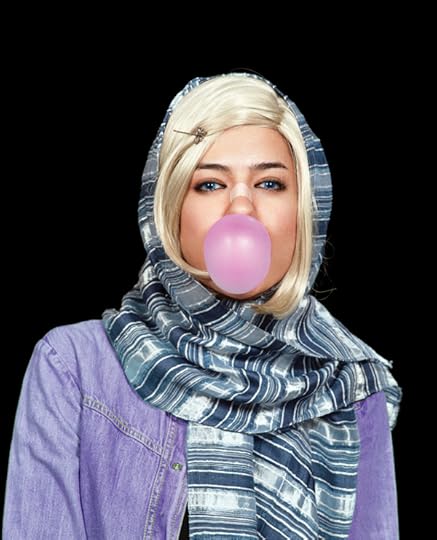

Shirin Aliabadi, Miss Hybrid, 2008

Courtesy The Third Line, Dubai

Shirin Aliabadi, an Iranian multidisciplinary artist known for her colorful portraits of young women breaking the stereotypes associated with the country’s strict moral and dress codes, passed away in her native Tehran in October. She was forty-five. Trained as an archaeologist and art historian at the University of Paris, Aliabadi had a returnee expat’s quizzical eye, which gave her a fresh point of view to survey the changes in her native country during the reform years of Mohammad Khatami’s presidency. At a time when Iran was experiencing a respite from the zeal of its early revolutionary days and the austerity of an elongated war with its neighboring Iraq, a growing younger population had helped elect Khatami for a second term in 2001, and began the process of changing the landscape of the country, especially in the capital, Tehran.

Shirin Aliabadi, Girls in Cars, 2005

Courtesy The Third Line, Dubai

In Aliabadi’s Girls in Cars (2005), the artist recorded the urban phenomenon of nocturnal cruising in cars as a pastime of young Tehranis. Restricted in their interactions with the opposite sex in the public space, the middle-class youth used their cars to engage in a vehicular mating dance fueled by unspent hormones and cheap petrol, causing massive traffic jams in the streets in the north of Tehran. In an interview with Deutsche Bank’s ArtMag, Aliabadi recalled her time capturing the images of young women all dressed up to be seen through the windows of their cars “as the best time I ever had stuck in traffic.” Commenting in 2005 on this series of snatched photographs, she elaborated: “Every time my flash would go off in the street I would attract a lot of attention. The girls in cars were very curious and we would start a long friendly conversation about why I was taking the pictures, what was I going to do with them, where were they going to be published, etc.” The photographs show a range of reactions from the women: some are playful, others tentative.

Shirin Aliabadi, Miss Hybrid, 2008

Courtesy The Third Line, Dubai

While Girls in Cars is essentially journalistic in style, Aliabadi’s best-known work, Miss Hybrid (2007), is a selection of staged portraits of young Iranian women with bleached-blonde wigs wearing lurid blue contact lenses over their naturally brown eyes, proudly sporting nose-job plasters. Nose jobs, hugely popular in Iran, where women prize upturned European noses, had become a staple topic in the media coverage of Iran at that time. Aliabadi’s blonde babes were staged to look defiant, blowing bubblegum or coquettishly nibbling at giant lollipops. By the time she created this series, foreign media had already discovered the lure of images of Iranian women licking ice cream or handling a dripping petrol nuzzle to accompany news about the country.

Shirin Aliabadi in an undated photograph

Courtesy The Third Line, Dubai

Miss Hybrid is regarded by Western critics as a celebration of resistance in the face of oppression in a country where, for over a century, the wrangling over modernity and tradition has been played out on the bodies of its women and their style of dress. Aliabadi herself was aware that this interpretation of fashion as resistance may be simplistic.” I don’t believe that you automatically become a rebel with a Hermès scarf around your neck, but in the context of the society in which we grew up, within an educational system that has different values to those in the West, the phenomenon of fashion turns into an interesting paradox,” she said in 2013. “But ultimately, these young women’s concern is not to overthrow the government but to have fun.”

Shirin Aliabadi, City Girl, 2010

Courtesy The Third Line, Dubai

With Miss Hybrid, Aliabadi did more than point to a playful form of rebellion; she highlighted the painful truth that forced values may engender unexpected reactions. Her “Miss Hybrids” are the forerunners to the new subculture of palang (“leopard”) women in Iran, who alter their faces through extensive surgery to mimic an exaggerated idea of beauty reminiscent, at best, of Barbie. In Miss Hybrid, Aliabadi successfully captured the dilemma of young Iranian women who, in an attempt to free themselves of their social restraints, manage to take refuge in another trap, that of consumerism and objectification.

Haleh Anvari is a writer based in Iran.

The post She Captured the Face of Modern Iran appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 1, 2018

Aperture Celebrates Family at the 2018 Gala

Michael Hoeh, Chelsea Clinton, and Elizabeth Kahane

Sean Zanni/PMC

Marilyn Minter and Nan Goldin

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Catherine Opie, and Carrie Mae Weem

Sean Zanni/PMC

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Stuart Cooper, R. L. Besson, Chris Boot, Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas, and Cheryl Finley

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Tanya Selvaratnam, Hank Willis Thomas, Alice Walton, Chris Boot, and Alvin Hall

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Alvin Hall, Jessica Nagle, Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas, and Cheryl Finley

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Vinoodh Matadin, Ethan James Green, and Inez Van Lamsweerde

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Mickalene Thomas, Racquel Chevremont, Rujeko Hockley, Julie Mehretu, and Catherine Gund

Sean Zanni/PMC

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis

Sean Zanni/PMC

Dr. Deborah Willis

Sean Zanni/PMC

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Agnes Gund, and Catherine Gund

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Naina Lavakre, Hemant Kanakia, Sonal DesaiPatrick McMullan/PMC

Vinoodh Matadin, Inez van Lamsweerde, Chris Boot, Marilyn Minter, Jane McCarthy, and Kathy Ryan

Patrick McMullan/PMC

David Gilbert, Alice Razmesson, Sara Cwynar, and Sam Contis

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Rujeko Hockley and Hank Willis Thomas

Sean Zanni/PMC

Hank Willis Thomas, Catherine Opie, Alvin Hall, Agnes Gund, Catherine Gund, Rujeko Hockley, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Dr. Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas, and Carrie Mae Weems

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Agnes Gund and Sarah Arison

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Alexa Dilworth, Tim Doody, Kati Doody, Peter Barbur, and Leah Ettensohn

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Helen Nitkin and Joel Rosenkrantz

Sean Zanni/PMC

Anne Stark Locher and Zoe Bergeron

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Bob Gruen and Elizabeth Gregory Gruen

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Gavin Shiminski, Elaine Goldman, and Ruben Natal-San Miguel

Mary Ellen Goeke and Thomas R. Schiff

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Carrie Mae Weems, Julie Mehretu, Agnes Gund, Catherine Gund, and Catherine Opie

Patrick McMullan/PMC

William Kahane and Elizabeth Kahane

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Robyn Stein, Agnes Gund, Catherine Gund, and Catherine Opie

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Daphne Takahashi, Chris Berntsen, Karen Benik, Hank Willis Thomas, and Rujeko Hockley

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Roland Hartley, Jessica Nagle, Pepper Nagle, and Dwight Greenhouse

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Carl Xtravaganza and Sarah Anne McNear

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Vinoodh Matadin and Inez van Lamsweerde

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Gail Albert Halaban, Steven Rifkin, and LaVon Kellner

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Matthew Pillsbury and Ferratti Valerio

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Agnes Gund and Catherine Gund

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Alvin Hall

Sean Zanni/PMC

Chris Boot

Sean Zanni/PMC

Hank Willis Thomas and Dr. Deborah Willis

Sean Zanni/PMC

Terry Nathan, Marilyn Kanter, Elizabeth Kahane, and William Kahane

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Gala cochair Sir Elton John

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Rori Grenert and Dominique Silver

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Missy O'Shaughnessy and Daniel Foster

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Balarama Heller, Lynne Tillman, and Richard Renaldi

Patrick McMullan/PMC

William Kahane, Gavin Shiminski, and Elizabeth Kahane

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Eddie Cooper and Remy Holwick

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Dr. Deborah Willis, Hank Thomas and Cathy Kaplan

Alvin Hall and guests

Anja Schwarzer © Aperture Foundation

Ethan James Green

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Nicole Fleetwood, Cheryl Finley, Deborah Willis, Lisa Coleman, and Kalia Brooks Nelson

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Marisa Cardinale, Peter Kunhardt Jr., Susan Gutfreund, and Chris Boot

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Marilyn Minter, Howard Greenberg, and Kathy Ryan

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Stuart Cooper, Becky Besson, and Matthew Pillsbury

Patrick McMullan/PMC

LaVon Kellner and Darius Himes

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Hannah Whitaker and Matthew Porter

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Hank Willis Thomas and Dr. Deborah Willis

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Jared Olivo, Lisa Rosenblum, Nina Rosenblum, and Brian Ellner

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Eve Lyons, Daniel Arnold, and Joanna Nikas

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Cathy Kaplan, Catherine Opie, Jane McCarthy, and Lynne Tillman

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Sara Cwynar, Elise Rasmussen, Lisa Seischab, and LaVon Kellner

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Steve Zuckerman, Cathy Kaplan, Darlene Kaplan, Ren Martin, Esther Zuckerman, Bob Marshall, and Vivian Yee

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Jane McCarthy, Catherine Opie, Eric Johnson, and Michael Stout

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Anne Huntington, Sarah Arison, and Noreen Ahmad

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Daniel Gerard, Severn Taylor, Olivia Birkelund Gerard, and Scott Switzer

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Chelsea Clinton, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, and Catherine Gund

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Sacha Yanow and Catherine Gund

Patrick McMullan/PMC

David Dechman and Clarissa Bronfman

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Cathy Kaplan, Alice Walton, Julian She, Liz Swig, and Michael Hoeh

Sean Zanni/PMC

Dwight Greenhouse and Pepper Nagle

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Stefano Tonchi, Catherine Opie, and Eric Johnson

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Catherine Gund, Rujeko Hockley, Lacy Austin, and Hank Willis Thomas

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Rujeko Hockley and Hank Willis Thomas

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Michi Jigarjian, Zoe Buckman, Michael Hoeh, and Sarah Haimes

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Marilyn Minter and Catherine Opie

Sean Zanni/PMC

Lyle Ashton Harris and Lesley A. Martin

Sean Zanni/PMC

Russell Craig and Nicole Fleetwood

Patrick McMullan/PMC

Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas

Sean Zanni/PMC

Susan Gutfreund and Rushka Bergman

Sean Zanni/PMC

Cathy Kaplan and guests

Sean Zanni/PMC

Kathy Sledge performs at the Aperture Gala

Sean Zanni/PMC

Coco and Breezy

Sean Zanni/PMC

The House of Xtravaganza

Sean Zanni/PMC

The House of Xravaganza

Sean Zanni/PMC

Kathy Sledge performs with The House of Xtravaganza at the Aperture Gala

Sean Zanni/PMC

Kathy Sledge performs with The House of Xtravaganza at the Aperture Gala

Sean Zanni/PMC

The House of Xtravaganza

Sean Zanni/PMC

On October 30, Aperture celebrated the family—the human family and the Aperture family—by honoring five outstanding artists and philanthropists at the foundation’s annual gala: Agnes Gund, Catherine Gund, Catherine Opie, Hank Willis Thomas, and Dr. Deborah Willis. Centered around the launch of Aperture magazine’s winter 2018 issue, “Family,” the Aperture Gala brought together leading artists, curators, writers, and public figures including Carrie Mae Weems, Julie Mehretu, Rujeko Hockley, David Dechman, Alvin Hall, Sarah Lewis, Marilyn Minter, Chelsea Clinton, Nan Goldin, Mickalene Thomas, Lisa Rosenblum, Kathy Ryan, Elliot Erwitt, Inez & Vinoodh, Ethan James Green, Quentin Bajac, Liz Swig, and Alice Walton. “We could not have a group that better exemplifies what Aperture cares about and stands for,” Cathy Kaplan, Aperture’s board of trustees chair, said. “Community, great art, great writing, and great philanthropy.”

Throughout the evening, special guests gave moving tributes to each of the honorees. Marilyn Minter spoke of Catherine Opie’s pathbreaking photographs about queer life in the U.S. Opie documented her community with dignity, Minter said. “Her portraits stare right back at you. Her portraits become the royal family.” Sarah Elizabeth Lewis honored philanthropist Agnes Gund and her daughter, the filmmaker and activist Catherine Gund. “When others relax, you press onwards,” Lewis said. “When others think of personal gain, you consider what good can come for all of us.”

Lewis joined the artist Carrie Mae Weems in praising the scholar and photographer Deborah Willis and her son, the artist Hank Willis Thomas. “You have been the world of insight, information, leading us out of darkness into light. Always asking questions that few others dare to ask,” Weems said.

Accepting her tribute, Catherine Gund spoke on behalf of her mother. “For us, Aperture Foundation fills a unique place in our little, and very big world,” she said. “And it’s such a crazy time. One of my thoughts to live by comes from Toni Morrison, who said that at some point in life, the world’s beauty becomes enough. You don’t need to photograph, paint, or even to remember it. It is enough. And I feel like until that time comes, we have Aperture.”

The evening ended to the classic “We Are Family” performed by Kathy Sledge, of Sister Sledge, joined by members of New York’s legendary House of Xtravaganza.

Leading up to the gala, patrons enjoyed a weekend full of studio visits, gallery talks, and collection tours with Chloe Dewe Mathews, Sara Cwynar, Lehmann Mapuin, and Bernard Lumpkin and Carmine Boccuzzi. On the evening of the gala, Robbie Gordy of Christie’s auctioned works by Todd Hido, Dawoud Bey, Gordon Parks, Hank Willis Thomas, and Richard Mosse. For the second year in a row, Aperture partnered with Magnum on the Square Print Sale, presenting 6-by-6-inch prints by artists such as Nan Goldin, Bruce Davidson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Kwame Brathwaite, and Mary Ellen Mark. The prints are available for sale online through Friday, November 2, 2018, at 6:00 p.m. EST.

Aperture’s endeavors are made possible with contributions from gala patrons and Aperture trustees and Members. Click here to donate to Aperture’s Annual Fund or join our community as an Aperture Member.

The 2018 Aperture Gala and Auction was made

possible with the generous support of:

Sponsors

Adobe, Christie’s, and Ingram Content Group

Cochairs

Sir Elton John

Judy and Leonard Lauder

Nion McEvoy

Jessica Nagle

Leader Committee

David Dechman and Michel Mercure

Agnes Gund

Elizabeth* and William Kahane

Hemant Kanakia* and Sonalde Desai

Cathy M. Kaplan* and Renwick D. Martin

Judy and Leonard Lauder

Anne Stark Locher* and Kurt Locher

Nion McEvoy*

Jessica Nagle* and Roland Hartley-Urquhart

Lisa Rosenblum

Thomas R. Schiff*

Gala Committee

Adobe

Malú Alvarez

Anonymous (2)

Peter Barbur* and Tim Doody

Elyse and Lawrence B. Benenson

Dawoud Bey*

Allan Chapin* and Anna Rachminov

Sb Cooper* and R. L. Besson

Fine Art Frameworks

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Elaine Goldman* and John Benis

Mrs. John Gutfreund

Hermès of Paris

Darius Himes, Christie’s

Jeff Hirsch, Foto Care

Michael Hoeh*

Inez and Vinoodh

Jack Shainman Gallery

Darlene Kaplan and Steve Zuckerman

Deana Lawson

Lehmann Maupin and Regen Projects

Susana Torruella Leval and Hon. Pierre Leval

Marina and Andrew* Lewin

Patrick McMullan

Sarah Anne McNear*

Helen Nitkin* and Joel Rosenkranz

Philip C. Ollila, Ingram Content Group

Missy* and Jim O’Shaughnessy

Lisa S. Pritzker

The Rosenstiel Foundation

Sheri Sandler and Mark Schneider

Melissa Schiff Soros

Severn Taylor* and Scott Switzer

Willard Taylor* and Virginia Davies

Alice L. Walton

Whit Williams

*Aperture trustee

The post Aperture Celebrates Family at the 2018 Gala appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Protected: Aperture Celebrates Family at the 2018 Gala

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: Aperture Celebrates Family at the 2018 Gala appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 29, 2018

Fifteen Photographers at a Crossroads

How can a photograph transform us?

A crossing implies movement across a physical border, but a photograph can also depict personal crossroads that lead to growth and change. Pictures can be transformative in their ability to deepen one’s sense of selfhood, or expand their understanding of identity. From Joel Meyerowitz to Susan Meiselas, Aperture and Magnum photographers have long demonstrated how photographs can spark change, both literal and metaphoric.

This week, for five days only, get signed and estate-stamped, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by acclaimed Aperture and Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase and a percentage of each sale will support Aperture Foundation. Visit Aperture Gallery through November 2 to view Crossings, a special exhibition hosted by Airbnb Magazine, featuring photographs from the sale.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Belinda de Gaucho, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alessandra Sanguinetti

“Back in 1998 when I started taking pictures of Belinda and Guillermina, I asked Belinda what she thought she would have been like had she been a boy. She didn’t hesitate. She painted a mustache with a burnt cork, took off her shirt and looked straight at the camera.” —Alessandra Sanguinetti

Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Sikolo with Carolee Prince Designs), 1968

© the artist and courtesy Philip Martin Gallery

Kwame Brathwaite

“This is a picture of Sikolo Brathwaite, my wife and muse. The headpiece, inspired by South African beadwork, was designed by Carolee Prince, whose exquisite beadwork was also worn by Nina Simone and can be seen in many of my photos. This picture is part of the ‘Black Is Beautiful’ narrative—an embrace of African ancestry and unifying the black experience around the globe.” —Kwame Brathwaite

Nan Goldin, Drugs on the Rug. New York, 2016

© the artist

Nan Goldin

“I was addicted to OxyContin for four years. I overdosed but I came back. I decided to make the personal political. I’ve started a group called P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) to address the opioid crisis. We are a group of artists, activists and addicts that believe in direct action. We target the Sackler family, who manufactured and pushed OxyContin, through the museums and universities that carry their name. We speak for the 250,000 bodies that no longer can.” —Nan Goldin

The photographer’s proceeds from the sale of this print will help fund the work of P.A.I.N.

Joel Meyerowitz, New York, 1965

© the artist

Joel Meyerowitz

“A girl on a Vespa on her way to ‘who knows where,’ when the light stopped her at the 72nd street crossing near the Dakota, where John Lennon would one day cross paths with his fate. She takes this moment to finesse a fingernail before she resumes her downtown journey, while I, stopping at the same crossing, but on foot, leap into the street to capture this vision of a dream girl before time takes her on her way.” —Joel Meyerowitz

Mary Ellen Mark, Hippopotamus and Performer, Great Rayman Circus. Madras, India, 1989

© the artist

Mary Ellen Mark

“Photographing the Indian circus was one of the most beautiful, joyous, and special times of my career. I was allowed to document a magic fantasy that was, at the same time, all so real. It was full of ironies, often humorous and sometimes sad, beautiful and ugly, loving and at times cruel, but always human. The Indian circus is a metaphor for everything that has always fascinated me visually.” —Mary Ellen Mark, excerpt from Indian Circus (1993)

Pete Souza, Million Man March. Washington, D.C., 1995

© the artist

Pete Souza

“I had covered numerous protests and rallies on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. But the Million Man March surpassed all of those as an unforgettable experience. Hundreds of thousands of African American men gathered en masse for a peaceful rally, stretching from the U.S. Capitol to the Washington Monument. . . . I saw these two adult men with their sons, the golden light illuminating the Capitol. It was a symbolic moment of reflection, for them but also for me, on what this day meant.” —Pete Souza

Bruce Davidson, Brooklyn Gang, Backseat of a car, New York City, USA, 1959

©the artist/Magnum Photos

Bruce Davidson

“You’re looking at Lefty and his girlfriend, members of a Brooklyn gang who referred to themselves as ‘The Jokers,’ on a trip to Bear Mountain State Park. This photograph is not meant to be risqué. These were young, teenage kids who had a great deal of spirit, energy and love in lives that were reckless, unstable and oftentimes dangerous. . . .

The gang was completely out of their element. No mean streets, not a worry on their minds, just time to explore themselves and their surroundings. They were free, and it was captivating.”

—Bruce Davidson

Bieke Depoorter, Agata, Paris, France, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Bieke Depoorter

“October 2017: I wandered around at night in Paris, looking for . . . someone that could help me translate the atmosphere in my mind with a story that would partially be theirs as well. The result, ‘Agata,’ is an ongoing project about a young woman I met at a striptease bar one of those nights, in which I explore my interest in collaborative portraiture. . . .

As Agata once wrote to me: ‘I am going to give you myself, and you will wrap it with Bieke, and I believe something beautiful can be created.’” —Bieke Depoorter

Chien-Chi Chang, A newly arrived immigrant eats noodles on a fire escape, New York, USA, 1998

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Chien-Chi Chang

“Humans need to hold hope in their hands. This man was willing to live in poverty in hope of prosperity. . . . A few years later, this man was able to bring his family to New York, and today they are living the American dream. He is now a grandfather! But is economic prosperity worth the social cost? Perhaps the answers to such questions can be found in the lives of the people left behind in China and in those of the second and third generations who are growing up in the United States. Look at them and listen to their voices. You may not understand their language, but you can feel their longing.” —Chien-Chi Chang

Olivia Arthur, Bombay, India, 2016

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Olivia Arthur

“I photographed Nikhil for my project ‘In Private, Bombay,’ an exploration of privacy, sexuality and the changing atmosphere in the city of Mumbai. . . . At the time there was a contradictory atmosphere in the city. At once an opening up of voices, boldness and desire to talk about sexuality. Yet, at the same time, there was growing Hindu conservatism and seeming regression across the country. The combination of audacity and intolerance made for a feeling of friction as well as excitement.” —Olivia Arthur

Susan Meiselas, Fifth Avenue, New York, 1977. From the series, “Volunteers of America”

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“In 1977, I followed the men who performed as Santa Claus to raise funds for the Volunteers of America. They were recovering alcoholics, ringing bells on the street all day long. On Fifth Avenue, they crossed the lives of those who would never look at them otherwise.” —Susan Meiselas

Justine Kurland, Tonguing BQE, 1997

© the artist

Justine Kurland

“The first condition of freedom is the ability to move at will, and sometimes that means getting into a car rather than getting out of one. It’s difficult to describe the joy of a carload of girls, going somewhere with the radio turned up and the windows rolled down. . . . At last we arrive at a view, a place where the landscape opens up—a place to plant a garden, build a home, picture a world. They spill out of the car along with candy wrappers and crushed soda cans, bounding into the frame, already becoming a photograph.” —Justine Kurland

Ethan James Green, Three Boys in Maheshwar, India, 2018

© the artist

Ethan James Green

“I was drawn to these three guys together. There was something alternative about them. They reminded me of myself when I was younger, all serious about doing the hair and the clothes. . . . I found it interesting the way they threw their arms around each other, in a place where male friendships seem to be expressed much more intimately than they are in the United States. I like this picture too because, when you look for a moment, you see that they all have smartphones in their hands. This detail seems right. Boys the same age all over the world who see this picture will understand exactly what’s going on and relate to it.” —Ethan James Green

The photographer’s proceeds from the sale of this print will be donated to Operation Smile.

Graciela Iturbide, Pájaros en el poste, carretera a Guanajuato (Birds on the post, highway to Guanajuato), Mexico, 1990

© the artist

Graciela Iturbide

“I was in my car on the highway to Guanajuato, and suddenly I saw this flock of birds. I love birds, for me they represent freedom.” —Graciela Iturbide

Alex Webb, Maquilla worker housing being built, Outskirts of Tijuana, B.C., 1995

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Webb

“I’ve long been fascinated by the transience and paradoxes of the U.S.-Mexico border. Even though these two countries were culturally worlds apart, it sometimes seemed that the border region was a kind of third country between them—2,000 miles long and 10 miles wide, a place where two countries meet, sometimes easily, sometimes roughly, and often with a confounding note of surrealism. . . .

In 1995, while walking through the outskirts of Tijuana, I was surprised to find this box of brightly colored shoes, which seemed so out of place on this dusty, isolated embankment. . . . Was there a market here earlier—and these shoes left behind? . . . In my bad Spanish, I asked a passer-by if he knew. The old man just shrugged his shoulders.

To this day, this surreal scene remains a mystery.” —Alex Webb

This week, for five days only, get signed and estate-stamped, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by acclaimed Aperture and Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase and a percentage of each sale will support Aperture Foundation. Visit Aperture Gallery through November 2 to view Crossings, a special exhibition hosted by Airbnb Magazine, featuring photographs from the sale.

The post Fifteen Photographers at a Crossroads appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers