Aperture's Blog, page 91

March 15, 2019

A Filmmaker’s Journeys Across the African Diaspora

Throughout his career, photographs and family narratives have been at the center of Thomas Allen Harris’s films.

By Serubiri Moses

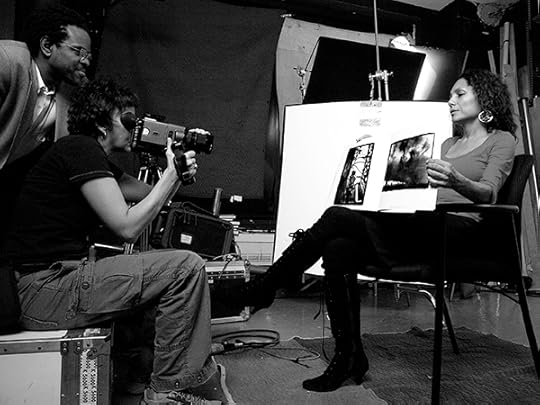

Production still from Through A Lens Darkly, 2014

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

I first came across the work of artist, writer, and filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris in an article for California Newsreel by curator Rhea L. Combs, in which she calls Harris’s documentary É Minha Cara (That’s My Face) (2001) “a queer mythopoetic journey through the African Diaspora.” Currently, Harris is known for his recent appointment as a senior lecturer at Yale School of Art, but early in his career, in the 1980s, he was known as television producer. He also gained recognition for his participation in the 1995 Whitney Biennial, and as a member of the experimental video-film and postconceptual art scene in SoHo and Lower East Side of Manhattan during the same period. Yet I have come to understand his work as being located in the cultural triangulation about the Atlantic: Africa, South America, and North America. In this interview, Harris speaks about four works: VINTAGE – Families of Value (1995), É Minha Cara/That’s My Face (2001), Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela (2006), and Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People (2014).

Through a discussion of his creative process, Harris engages with the notion of the “circle” when thinking about photographic archives. He not only advances the circular as a thematic through which to view the archive, but he equally reveals the importance of archives in building stories, narratives, or history. This might not appear unique—that is, until one considers Harris as being proximate to the 1990s efforts by New York–based artists and writers who intervened in histories within which they had yet to be adequately represented. Such an effort is illustrated in the Black Gay and Lesbian Archive, which focuses on the correspondence and personal papers of several Black and queer figures, at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the New York Public Library.

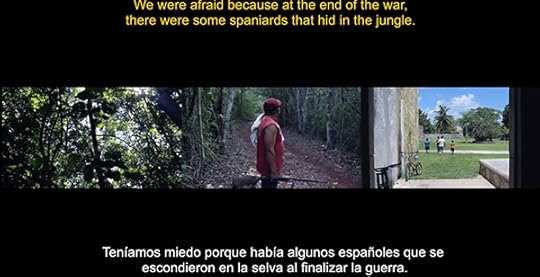

Production still fromTwelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela, 2005

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

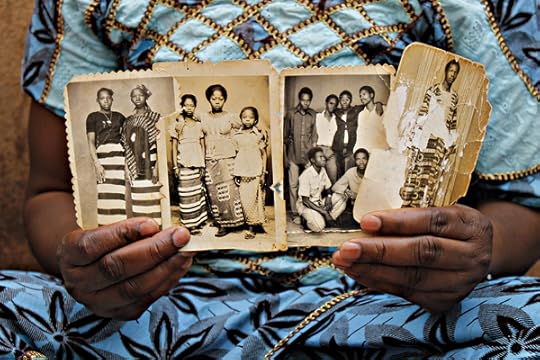

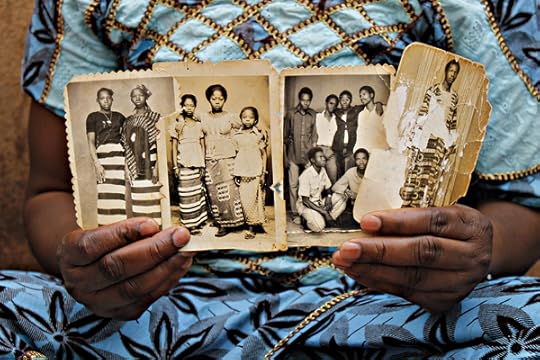

Because of the precarity of historical records, personal letters and photographs are liable to go missing. Often, these are the missing parts of the “circle” or of a story. Completing this story can be challenging, if not exhausting. And as such, for Harris, the search for historical and personal archival documents is one of self-determination and conviction. Harris’s filmic process has consisted of making journeys across both time and space in Bahia, Brazil; Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; Bloemfontein, South Africa; and Harlem, New York.

While the photo album can be the concrete container of personal family portraits—listing dates and events in one family—it can also be a metaphor for a larger cultural and political history. In Through a Lens Darkly, Harris demonstrates how connections can be made between his own family and a larger American story through the juxtaposition of Frederick Douglass’s portrait with his childhood portraits taken by his grandfather, thus revealing the power of archives as mediums of storytelling.

Production still from É a Minha Cara (That’s My Face), 2001

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Serubiri Moses: In all your films, there is a recurring moment at which the first person “I” becomes emancipated through photography. In É Minha Cara, this happens through a filming process during which the narrator “sees himself” in the cultural process of the Yoruba festivals in Bahia, Brazil. What does a photographic liberation mean to you?

Thomas Allen Harris: I think it’s the relationship of photography to the mirror. In the sense that it can give another kind of a reflection, and not a posed reflection. It’s more about how one is seen within one’s community. It is this reflection-refraction. This sense of being present and seeing oneself across time, through photography.

I was raised in front of the camera. In the course of making my films, I realized the extent to which my grandfather documented the family. I had lived there growing up, and I was the first grandchild, the first of four that lived with them. My grandmother principally took care of me and my grandfather photographed me. And so I was the model. Just finding those images shows that the camera can be, in the context of family, this gift of love.

Moses: That’s incredible. Can you describe this more?

Harris: It means that you can actually be present with someone, engage, take pride in, and encourage. Subconsciously I have that awareness. It’s something that my brother has as well: Lyle Ashton Harris, who turns it into his own work and trajectory.

The camera has been a very reassuring presence in our lives. As opposed to some situations where people want to avoid the camera: “Don’t take a picture of me.” The way in which they are seen, they must have encountered a vision of themselves, photographically, that was about a kind of denial of beauty and power. It might be a projection. But the camera has been an affirmative tool, an emancipatory tool, growing up in a country in which the stereotype looms so large.

Production still from Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela, 2005

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Moses: The family album becomes this method to examine photographic history but also national history. It is America’s photographic history, but it’s also a family history. I was interested in that, and you just affirmed it. But what other containers or structures exist beyond the family album?

Harris: For me, the archive has been clues left on a path to help me realize certain aspects of identity—whether diasporic identity or personal identity—and tools to be able to create. So much of my work is inspired by the archive, or kind of rubbing up against the archive and creating something alongside it, another narrative that’s both personal but also in the service of a collective or community building. In terms of my work, it is about socially engaged practice. As I am engaging these journeys around filmmaking, the films are really rubbing up against these individuals and changing certain things, and inviting people in. Each of them has been a participatory practice, and community building.

Moses: You have the family album as this strong container, that you can refer to; you have your own pictures, you know the people who have taken the pictures, you have seen yourself in the album change over time, you can reference it.

Harris: If I had not embarked on the films that I’ve embarked upon, it would not have set me on a journey to find these archives—they were not readily available. They were not readily available in the way that I could use them. They weren’t in my consciousness.

Production still from VINTAGE – Families of Value, 1995

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Moses: When you worked as a film producer in the late ’80s into the early ’90s, how did you transition into that kind of performative photographic work that you were making? It looks very much connected to the artists who were working around you at that time—no doubt your brother Lyle Ashton Harris is among them, as well. And what structures were available to you to do that work before you actually found the archives?

Harris: The first film is called VINTAGE – Families of Value. And that film I started in the late ’80s. It looks at three African American families through the lives of LGBT siblings. So with three different sibling sets, I gave them cameras and asked them to interview each other. In part it started when my brother tested HIV positive, and I introduced the camera into our dialogue, and we start speaking across the camera. And so that became this kind of family conversation that was happening. I was also directing these non-actors to perform, including myself, to perform their identities in a certain kind of way. I started to look for archival material to support that film. At the time, I wasn’t looking at the archival materials in this intense kind of way that I would later on in the next three films. They came to me: they were like gifts. In my bed, underneath the bed that my stepfather made for us, I found these three reels of Super 8 film. They were the films I used in that film VINTAGE – Families of Value. That’s when I started.

Production still from VINTAGE – Families of Value, 1995

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Moses: Can you tell me the story of É Minha Cara?

Harris: After we finished VINTAGE – Families of Value, I started traveling. First place I traveled with that film was Brazil. I decided to go and make a film in Brazil, I had always wanted to. I left with two Super 8 cameras to just document this journey, but also was aware—as I had done the stuff with Vintage Families—that I wanted to pass on the camera, and empower others, towards an inter-collaborative filmmaking process with me, and to film me if they wanted to. I was there for three months in Salvador da Bahia, documenting the Brazilian festivals that climax in carnival. The religious festivals, based on West African, but more specifically Yoruba deities—Oshun, the pantheon of deities that migrated from Western Africa to the New World. When I came back, I got a call that my film VINTAGE – Families of Value, even though it was rejected by almost all African American festivals in America, was selected to screen at the Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de Ouagadougou (FESPACO) in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. This was 1997. They flew me from Salvador da Bahia all the way to Ouagadougou. I screened there and continued to shoot. I took my camera there as well.

So I came back from Ouagadougou directly to Salvador da Bahia. I got to see this place in Brazil, essentially Africa in America, the largest concentration of black folks in the Americas. I got to see in that one trip both through an American perspective, coming from North America to South America, but also from West Africa to Salvador, before I came home. I had this experience. It changed the way I thought about things, but also the way I was filming. And I came back, I was filming with Super 8, because when I went to Brazil—in VINTAGE – Families of Value I had used Super 8 with a lot of the fantasy material. I didn’t use footage of people talking, because there had been a lot of talking between the siblings. I decided to move forward with this nonverbal kind of performative narrative. I grew up in Tanzania, we didn’t know Swahili very well, I traveled all around. The Chinese were coming in and building. British were leaving. There was all this dialogue happening even though it wasn’t always linguistic.

Moses: What do you mean by that?

Harris: Without it having to be human dialogue, I wanted to explore this kind of communication, cross-culturally. A visual kind of investigation. And I came back with the Super 8 film, all silent. And then started writing my script. I didn’t know what the script was going to be. And then I struggled and struggled and struggled. And then at last, I had a waking dream.

Production still from É a Minha Cara (That’s My Face), 2001

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Moses: When did you have the waking dream?

Harris: This is two years later. In 1997 my grandfather died. In 1999 I had a waking dream, I went to his basement, I found more Super 8 material. Because I had just had two reels, after I’d been trying to edit this film, trying to figure out what this film is about, and I knew that it was É Minha Cara. It’s a colloquial expression that means: “That’s my face.” If we look alike and could be part of a family—É Minha Cara—we look similar. It could be familiarity, similarity, or attraction. You could see someone on the street—É Minha Cara—cruising someone. I had this kind of thing that’s all about that filming without the sound. It was about what am I attracted to and why. My face. What am I looking for and why?

I came back and tried to put this into a coherent argument in the film and a script. And I realized that my mom made a similar journey when she took us to Tanzania in the 1970s. And that my grandfather also had wanted to go to Africa, but he was never able to go. And so I was trying to write about these three generations, but I didn’t have any visuals. Then I had a waking dream. I was living in San Diego, I was teaching at the University of California in San Diego as an assistant professor, and I came back to the Bronx and I went to my grandfather’s basement and I found hours and hours of Super 8 that documented our family as we went from being “colored” to embracing a Pan-African aesthetic with my stepdad, who followed us to Tanzania. And so if I had not gone to Brazil, I would not have looked for the material. And I looked for it for two years. And boom! It happened.

Moses: What happened after you found the hours of footage?

Harris: I was basically able to tell my story through my grandfather’s archive. And then I found my stepdad’s archive. I thought he had thrown it away, because something had happened. They transferred the material to this awful video, and then threw out the Super 8. But he hadn’t! And so I was able to transfer all of the Super 8 and tell the story. I didn’t know that when I was doing my Super 8 that I would be even remotely thinking about going back to my family’s material.

Production still from Through A Lens Darkly, 2014

Courtesy Chimpanzee Productions, Inc.

Moses: How did your work with archives emerge?

Harris: Over three generations. Multiple stories. Me and my grandfather and my mother on one hand, with the auditory story, and then me, my stepfather, and my grandfather in terms of the visual story, because we were shooting. So that’s how that emerged. I also found some other material there as well. I still need to go look for some others. That’s typically how my work with the archive emerges. With the exception of Through a Lens Darkly—it’s a little bit different. In Through a Lens Darkly, I was starting with the national archive—or not so much the national but rather the Black photographic archive. I was aware of my family archive, started with that, but went back to look at things in a completely different way. For instance, with Through a Lens Darkly I juxtapose the abundance of images that my grandfather had taken with the paucity of images that my father had taken.

Moses: Returning to an earlier point in the interview, the family album as a literal object can be stored in a place: a house; a suitcase. It is dated by names, marginalia, or timestamps printed with the photographs. It can defined by the cameras and what printing paper was used. How well or how badly it was stored. However, through our conversation, you present another understanding of the family album. Can you say more about it?

Harris: One way of framing it is the album is a metaphor as opposed to being literal. It is an archive. It is what one chooses to produce. What one chooses to keep. How one creates one’s archive. And all those things both physical and invisible. [In Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela] the story is told through an expanded concept of family. It’s a literal family: Lee’s [Harris’s stepfather B. Pule Leinaeng] family, including us in Harlem, and in Johannesburg. The family of twelve Bloemfontein comrades that he left South Africa with to meet Nelson Mandela in Tanzania. Then the larger South African family. The land, diaspora, and family between South Africa and America. In order to strengthen that circle, I had to fill my part of the circle.

Serubiri Moses has written and published internationally. His research, curation, and programming have taken place in Accra, Berlin, Cali, Kampala, and Nairobi.

The post A Filmmaker’s Journeys Across the African Diaspora appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Kummer & Herrman: Designing Your Story

Kummer & Herrman is a Dutch design agency that has built an acclaimed international portfolio of designs for photobooks. Join cofounder and designer Jeroen Kummer for a two-day workshop intended for photographers who are ready to transition their work to book form. This workshop will challenge participants to think about how to tell their photographic story in the most convincing and effective way. Participants will work with Jeroen on ways to develop their work and strategize on what materials, typography, and design elements are necessary for their project. The goal of the workshop is to determine what the work is about and how to strongly convey that idea to the public. The work brought in by participants can be either a finalized project or in development.

Kummer & Herrman (K&H) was founded in 1998 by Jeroen Kummer and Arthur Herrman. While their roots stem from the renowned Dutch tradition of graphic design for print, K&H has since grown into a multidisciplinary creative office that develops publications, exhibitions, visual identities, and campaigns over a wide range of media. Over the years K&H has built long-standing collaborations with individuals and organizations operating within the field of photography, leading to an internationally acclaimed portfolio of designs for photobooks, including Raphaël Dallaporta, Antipersonnel (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2011); Robert Knoth and Antoinette de Jong, Poppy: Trails of Afghan Heroin (Hatje Cantz, 2012); Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen, The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (Aperture, 2014); Martin Parr, We Love Britain! (Schirmer/Mosel, 2014); and Vasantha Yogananthan, A Myth of Two Souls (Chose Commune, 2016–19). In 2014, Kummer & Herrman won the prestigious Dutch Design Award.

Jeroen Kummer was born in Amsterdam in 1969. He is cofounder, designer, and creative director of K&H. In addition to his work at K&H, he currently teaches graphic design and storytelling at the Photography Department of the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Determine the best design and format for your project

Develop a strategy on how to transition your project into book form

Gain insight, advice, and best practices for book design

Materials to bring:

One photographic project that you’d like to bring to book form

Tuition:

Tuition for this two-day workshop is $500 and includes lunch and light refreshments for both days.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Wednesday, May 15, 2019

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.

If participants choose to purchase Aperture publications during the workshop they will receive a 20% discount. Aperture Members of all levels will receive a 30% discount.

RELEASE AND WAIVER OF LIABILITY

Aperture reserves the right to take photographs or videos during the operation of any educational course or part thereof, and to use the resulting photographs and videos for promotional purposes.

By booking a workshop with Aperture Foundation, participants agree to allow their likenesses to be used for promotional purposes and in media; participants who prefer that their likenesses not be used are asked to identify themselves to Aperture staff.

REFUND AND CANCELLATION

Aperture workshops must be paid for in advance by credit card, cash, or debit card. All fees are non-refundable if you should choose to withdraw from a workshop less than one month prior to its start date, unless we are able to fill your seat. In the event of a medical emergency, please provide a physician’s note stating the nature of the emergency, and Aperture will issue you a credit that can be applied to future workshops. Aperture reserves the right to cancel any workshop up to one week prior to the start date, in which case a full refund will be issued. A minimum of eight students is required to run a workshop.

LOST, STOLEN, OR DAMAGED EQUIPMENT, BOOKS, PRINTS, ETC.

Please act responsibly when using any equipment provided by Aperture or when in the presence of books, prints etc. belonging to other participants or the instructor(s). We recommend that refreshments be kept at a safe distance from all such objects.

The post Kummer & Herrman: Designing Your Story appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 13, 2019

Who Can Tell the Story of an Indigenous Community?

Twenty years after his first visit to New Zealand, photographer Martin Toft makes a photobook about—and for—the Māori.

By Will Matsuda

Martin Toft, Celebrating Christmas at the home of Te Tawhero Haitana and whanau in Raetih, 2016

© the artist

Te Ahi Kā: The Fires of Occupation is a record of the Danish photographer Martin Toft’s time living with a Māori community in New Zealand in 1996, as well as his return twenty years later. Toft’s deep connection to the land and the community is largely a result of his participation in an illegal occupation of Mangapapapa, an ancestral land inside Whanganui National Park, in 1996. During this time, Toft was adopted into a Māori family. They even gave him a Māori name—Pouma Pokai-Whenua. But, as photographers and critics reckon with the medium’s colonial, often racist history when it comes to representing non-Western people, who can tell the story of a community? Do we really need another white man representing Indigenous life? I recently spoke with Toft to understand Te Ahi Kā against the backdrop of decolonization, climate change, and Māori spiritualism.

Martin Toft, Descendants of female members of the family of Te Utamate Tauri, also known as Mrs. Waetford, 2016

© the artist

Will Matsuda: I’m interested to know the origins of this project. How did it begin?

Martin Toft: I lived in Auckland in 1995 while backpacking around the world. In 1996, when I was twenty-five, I returned to New Zealand on the recommendation by my mentor, a Danish photographer and photobook collector. He suggested I should begin a project about the Māori. I was very young and naive and I had no connection to Māori. I also had very little knowledge of white men using photography to explore Indigenous cultures and I knew very little about New Zealand’s colonial history.

I ended up living in a Māori community for six months in the King Country, the central plateau of the north island of New Zealand. This is where the Whanganui River runs. The river is the border between three major tribes. I spent my first two months in this area speaking with people in the community and not taking any photographs. I realized that I needed to learn to speak the language to really present who I was, as well as explain my intentions.

I met a Māori elder who taught me how to deliver a formal speech to the tribe. And when I gave a speech the first time, the elders who were listening told me that they could see my ancestors behind me when I was speaking. I had never experienced anyone talking like this. I think they saw me as someone who had come from another place, but someone whose ancestors had been there before. That’s why they welcomed me into the community.

Martin Toft, Catholic missionaries in the mid-19th century converted many Māori settlements along the Whanganui River and Jerusalem (in Māori, Hiruhārama) is still home to the religious order, The Sisters of Compassion and their historical convent and church, 2016

© the artist

Matsuda: And once you were part of the community, you became involved in their political actions as well?

Toft: After the initial ceremonies, I got integrated pretty seriously into the community. I took part in their occupation of a piece of ancestral land, Mangapapapa, deep inside Whanganui National Park, which surrounds the Whanganui River. It’s a very politically charged landscape. Many Māori tribes since the 1870s have been fighting the New Zealand government for ownership of this land and the river itself.

When the Europeans began colonizing New Zealand, they followed Western codes of land ownership; they began to portion off sections of the river and sold off pieces of land to new landowners. For the Māori, the river is a single living being, a whole thing. The tribes of Whanganui often refer to their river as an ancestor and talk about their river from the mountain to the sea. You cannot take one portion of the river, and seperate it from the rest.

In 2017, the government finally gave the customary rights and ownership of the river back to the Māori. Even more, the river has the same legal rights as a human. Before, if the Māori wanted to go fishing, travel by boat, establish a community, there were always legal disputes about how they could do this. With this new development in a settlement between the government and Whanganui tribes, it seemed a good time to return and finish the book. The book is about the time I spent with them in ’96, as well as my time there twenty years later, reestablishing the kinship that we had on a physical and spiritual level.

Martin Toft, The Whanganui River is surrounded by steep gorges covered in native bush and trees, 2016

© the artist

Matsuda: The Whanganui River appears throughout the book. In a white, Western framework, we think of a portrait of a person and a landscape photograph as two very different things. But if you’re thinking about this river as a spiritual being, as an ancestor, how does that change the way you photograph it?

Toft: I traveled up and down the river on numerous occasions. It’s a major tourist destination, and I didn’t want to take the clichéd photos that everyone else was taking. I wanted the book to mimic what it’s like when you’re traveling the river. All you can see is water and the bush on the riverbanks. In the book you never see any images of the river from above. Instead, it’s dense and dark.

The river has 239 rapids and each one has a Māori name and story attached to it. For people who never have been there, it just looks like water. But for the Māori, they see the water and the rapid and it may inspire them to recite a poem or incantation. So I wanted to photograph these rapids for that reason.

But how do you photograph something that is not physical? I’m not sure if photography can do that and I’m certainly not claiming that I’ve done that. But I am interested in exploring how a photograph can have a third dimension, a spiritual dimension.

Martin Toft, Once an animal is killed the heart is cut out and given back to the forest with a blessing, 2016

© the artist

Matsuda: This interview is published online in conjunction with the “Earth” issue of Aperture magazine. In the issue, Wanda Nanibush, a curator of Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, argues that Indigenous people need what she calls “visual sovereignty”—the idea that native people should be the ones in control of their image. A lot of people question if we need another white man photographing an Indigenous community. I’m curious as to how you worked through this idea yourself.

Toft: It’s a very important question. As I said at the beginning, I was naive when I first arrived, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have any respect for the culture. I arrived with an open mind and open heart wanting to learn from Māori and their unique way of life. In retrospect I think this naivete helped me make connections and form relationships, because I didn’t carry any historical burden that may have influenced my approach then. But of course now, twenty-some years later, having studied and gone to university, and teaching photography, I have a much better understanding of photography’s role in colonial history.

When I decided to finish the book, I did a lot of research about how Indigenous people in New Zealand had been photographed, especially in this particular region. In that research, I came across an expedition made by a white photographer in 1885, named Alfred Burton. His works now are held in national collections and some of his images are well-known within photographic history of that time, especially in the South Pacific regions. But he decided to go upriver, similar to me, to make photographs of the Māori at home. In 1921 there was another big ethnographic expedition to the river by a photographer named James Ingram McDonald, another white man. I wanted to make sure that the work that I produced recognized that history and context. I then began to think about how I could involve and collaborate with my Māori friends and family. I wanted them to have some creative ownership, and I wanted them to have input in the ways their images would be used.

Research in New Zealand archives was also an important element of the development of the book’s narrative and structure, and allowed images of ancestors from national collections to be seen by the descendants of those featured in nineteenth- and twentieth-century portraits. An important aspiration of the book is to reconnect people to their tribal treasures (taonga), and in the broadest sense to assist in wider reclamation of Māori knowledge, language, and customs.

Consultation to use the images was sought from living members of the Māori family, and permission was granted according to Māori taonga policies held in New Zealand museums, that acknowledge the guardianship (kaitiaki) and copyright of any Māori cultural treasures, including photographs that belong to tribes.

Martin Toft, The Haitana family photographed outside their home in Raetihi arranged in a similar photographic pose as Alfred Burton’s image Taumarunui – King Country, 2016

© the artist

Matsuda: How did you involve the Māori in the project?

Toft: When I returned to New Zealand in 2016, I took ten book dummies with me. I presented them to the tribe and explained to everyone, especially the elders, what my intentions were. I gave them the book dummies, which were more like family albums. It really showed the community and it was quite personal. It was far less abstract than the final book. So I wanted it to be a gift. Some of the people in those photographs from 1996 have since died, so I knew the photos would be valuable to the tribe.

I wanted to make sure that I had their permission to continue. This was partially what the trip was for, but it was also to make new work, now that I had much more background knowledge about my position as a photographer from outside the community. This time the images were mainly of the natural landscape. There were very few portraits.

After I transcribed all the interviews, I checked with members of the tribe to make sure that they made sense and that the information was correct. I wanted to make sure they were happy with the narrative.

Another reason I returned after twenty years was to ask why they had given me a Māori name, Pouma Pokai-Whenua. What exactly did that mean for them? This book also explores what it means for me.

But of course, I totally understand what your question is. I’m not trying to shy away from it; I still understand my position in the sense that they haven’t made the images, although in some of the images we collaborated on how we set them up, and how they posed. But essentially it is my interpretation. And, of course, I am a big advocate for Māori people themselves to be their own visual storytellers.

Martin Toft, A hāngi is a traditional Māori method of cooking food using heated rocks buried in a pit oven. It is still used for large groups on special occasions such as this tangihanga at Ngāpuwaiwaha Marare in Taumarunui, 1996

© the artist

Matsuda: I want to return to your Māori name. I think that gesture is key to this work. In one of the interviews about this in the book, you say, “I was young then and I didn’t fully understand the honour that was bestowed upon me. It is something that brought me back here 20 years later because I knew you had given me this privilege of being allowed to make these images. I do feel that there is a sense of responsibility to do something with this before I pass on.” Can you describe that responsibility? Is this book the “something”?

Toft: The group that I lived with was known in the area as being very politically active. They had been doing protests before, had been on television, and people had read about them in national media. I didn’t go there specifically to get involved politically with them, but that’s what ended up happening.

After I became accepted into the community, I was given the responsibility to talk to the media. It sounds very strange now. They knew that by doing the protests, and illegally occupying the land in the national park, that the media would be there. And of course they were. I was given the task to facilitate and mediate that side of things, while other members of the tribe had other responsibilities. It was my responsibility to make sure the story was handled in a proper way. I told them from the very beginning, even in the first formal meeting that I had with them, that I wanted to make a book.

I left in ’96, due to visa complications. My family (whānau) believe in Māori sovereignty and self-determination (tino rangatiratanga) and did not recognize the authority of the New Zealand immigration authorities. I persuaded them to not go forward with a legal challenge, and so I had to leave the country. And when I left, they told me that they trusted me entirely to use the material how I see fit. That was a very big responsibility that they gave me—to look after these photographs and stories of the community. I went back in 2016 to make sure that they still felt this way.

Martin Toft, Hunting for deer at night in the steep hills and forests surrounding the Whanganui River, 2016

© the artist

Matsuda: Now that the book is out, what are your hopes for it and the stories it contains?

Toft: I hope that this book is used within the community as a resource for future generations about what happened during the occupation in ’96. Those protests have now changed the law. The rights to the river have been given back to the people. There are still many claims on the land that surround the river, and those are now in the process of being settled too between Māori people and the New Zealand government.

I want this book to be part of that story. The book first and foremost is for them. I am, of course, not denying that it is for myself, too. But I am more interested in how it is received by them, and the wider Māori community, more than anything else. It’s great that a place like Aperture will write about it, or that the book will go to Paris Photo, but it’s for the Māori, first and foremost.

Right now we live in a world where the biggest issue is climate change and the environment. As Westerners, we have destroyed the natural world. We can learn so much from Indigenous communities, not just the Māori, about their relationship with the natural world. I hope we listen.

Te Ahi Kā was published by Dewi Lewis in 2018.

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer based in New York.

The post Who Can Tell the Story of an Indigenous Community? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 6, 2019

Will America’s National Monuments Survive the Trump Administration?

David Benjamin Sherry’s spectacular photographs of contested lands.

By Bill McKibben

David Benjamin Sherry, Río Grande del Norte National Monument, New Mexico, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

Before you’ve seen the West, you’ve seen the West—landscape photographs of the region, especially those by Ansel Adams, are so deep in our nation’s collective imagination that you have to work to actually see Half Dome, in California, or Shiprock, in New Mexico, even when you’re standing there with your hiking boots on.

David Benjamin Sherry’s recent pictures help us see again. Sherry is known for his fascination with color, for his analog techniques, and for what some have called his “queer revision” of the rugged and macho legacy of western landscape photography. His images of several national monuments, photographed last year, carry the same level of detail as Adams’s iconic pictures, the sublime clarity of the haze-free western summer afternoon. But drenched in unexpected and unreal color, they get you to take a second look.

And in this case, a second look is helpful for any number of reasons.

David Benjamin Sherry, Muley Point I, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

For one, looking backward, the great protected areas of the nation are not simply blank slates, empty wastes. They were often the homelands of this continent’s original inhabitants, and so they tell, among other things, the stories of our nation’s original shame. Their very emptiness is a reminder of what we did—all the more telling when the petroglyphs left behind at places like Bears Ears, the national monument in Utah, make clear what a bustling place it once was. These lands are as sacred to Indigenous cultures as they ever were, but there’s a tragic quality to that reverence now.

David Benjamin Sherry, Muley Point II, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

For another, looking forward, these same lands are no longer as sacred to the colonizing tradition as they once were. One of the great boasts of its legacy was the protected landscape: in the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, we felt ourselves rich enough to methodically put aside large tracts of land for the benefit of the rest of creation, or the future, or our idea that there was something lovely about wildernesses, even ones we might not see. Congress never got more poetic than with the Wilderness Act of 1964, with its commitment to protecting places “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Aside from the questions already raised about who was there originally, and aside from the obnoxious use of man that belies the text’s birthdate, the statute still marks something powerful: even in the middle of America’s great postwar boom, the understanding that we needed something more than we had.

David Benjamin Sherry, Sotol cactus, Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument, New Mexico, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

But we don’t think that anymore. Or at least, at the moment, those in charge don’t think that. President Donald Trump, among his endless provocations, has begun trying to roll back the protections of an earlier era, beginning with the national monuments pictured in Sherry’s images. For no reason other than to undo the work of the bigger souls who came before him, the petulant boy king has begun to take apart the network of protected areas that is one of the country’s great legacies. Actually, of course, there is another reason: the fossil fuel industry covets these lands, just as it covets the Arctic, and the offshore lease holdings along the North American coasts, and pretty much every other piece of real estate on the continent. Not content with merely destroying the planet’s climate, it must also do what it can to wreck the loveliness that has been set aside.

David Benjamin Sherry, Looking toward Valley of the Gods, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

Somehow the saturated and unsettling colors of Sherry’s photographs of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, in Utah, and the Río Grande del Norte National Monument, in New Mexico, among other western vistas, help us see all that splendor, all that history, and all those politics more clearly, or at least glimpse that something has gone wrong and is now going wronger in these places that have long been a comforting part of the landscape of the mind. No longer retreats or redoubts from the overwhelming bleat of our wired world, they are contested places. We must fight to make sense of them, and we must fight to preserve them, and we must fight to make sure that in their preservation they connect us back to the people who wandered them originally.

Iconic images have their place—but iconoclasm has its place too.

Bill McKibben, a writer and environmentalist, is the author, most recently, of Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? (2019).

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Will America’s National Monuments Survive the Trump Administration? appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

March 1, 2019

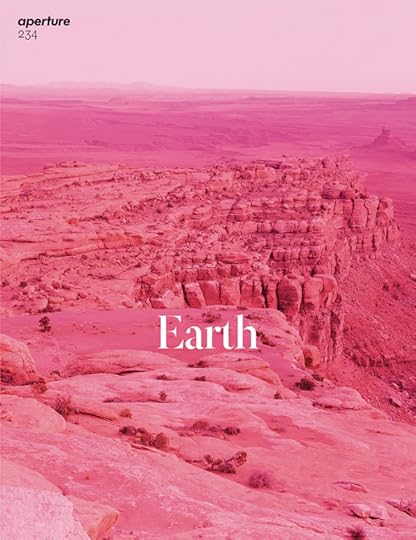

On the Cover: Aperture’s “Earth” Issue

David Benjamin Sherry, Looking toward Valley of the Gods, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah (detail), 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

“I first happened upon this remote area of southeast Utah in 2007, not realizing where I was until I found myself staring up at Comb Ridge,” says the photographer David Benjamin Sherry, whose photograph of Bears Ears National Monument is on the cover of Aperture’s spring 2019 issue, “Earth.” “This was my first photographic trip to the southwest, and I was in awe.”

In 2016, President Obama declared the 1,351,849 acres of Bears Ears, what Sherry calls “holy land,” a protected monument—an achievement for the five Native American tribes who have ancestral ties to the region, as well as for environmentalists who were seeking protected status of the area for decades. But only one year later, in December 2017, President Trump rolled back Bears Ears by eighty-five percent, making way for the possibility for oil extraction and mining.

“This was the point when I packed my car and headed directly back to Bears Ears to create this work,” Sherry says. “I remember thinking, on my drive, that everyone should be able to experience this place and have access to it.”

With his arresting, analog images, saturated in spectacular colors, Sherry is reclaiming the idea of the historic American landscape and making, as the environmentalist Bill McKibben writes in Aperture, a “‘queer revision’ of the rugged and macho legacy” of photographing the West. The warmth of the pink shade for his photograph from Bears Ears, in particular, “is emblematic of my intensified connection to the natural world and simultaneously connotes a sense of my ‘otherness’ as a queer person,” Sherry says. “Dramatic color is a way to entice viewers and also aid them in thinking about landscape differently.”

Throughout the “Earth” issue, photographers, artists, and writers from Carolyn Drake and Gideon Mendel to William Finnegan and Eva Díaz grapple with the reality of climate change and the age of the “Anthropocene,” in which human actions determine the factors shaping Earth’s geology and ecosystems. “We are losing our deep connection to the natural world and hastening our own demise in the destruction of places like Bears Ears,” Sherry says. “My aim with these pictures is to raise awareness about the fight for the reclamation of this National Monument and others being threatened.”

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post On the Cover: Aperture’s “Earth” Issue appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

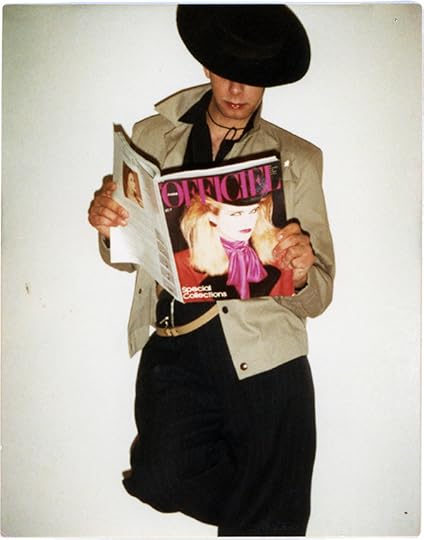

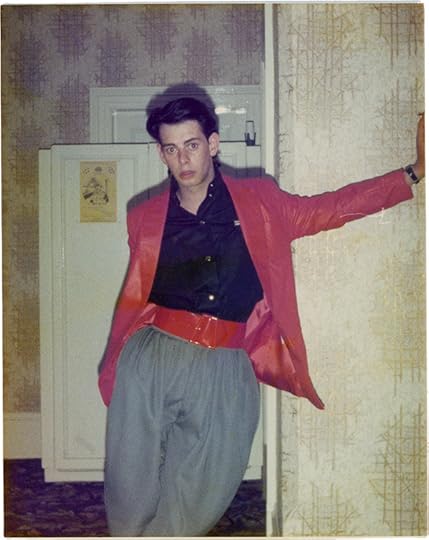

Looking Back at the New Romantics

A British photographer’s fashion-forward family pictures.

By Adam Murray

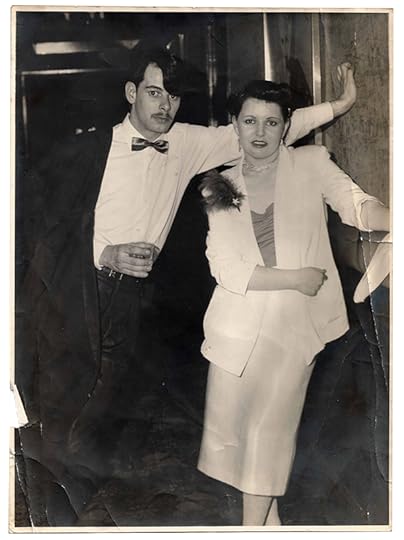

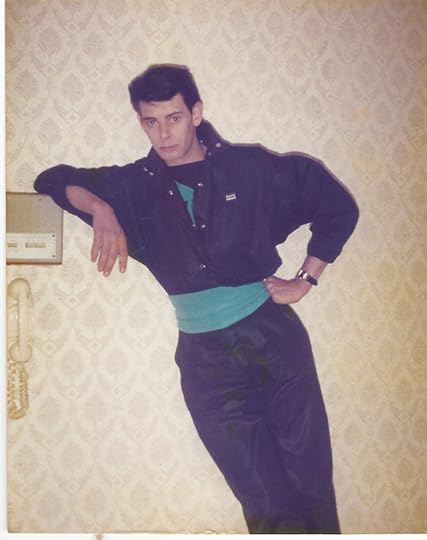

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Yvonne Taylor and her daughter Amelia Lonsdale are from Doncaster, a town in Yorkshire, northern England. I first encountered Taylor’s archive of photographs as a visiting lecturer at Leeds Arts University, where Amelia was studying photography. This personal archive consists of photographs predominantly featuring Yvonne and her partner at the time, Dennis Shedrick, produced while they were both living in the north east of England. The following are excerpts from a conversation I had with Amelia and Yvonne; I am currently working with them both to include the work in a group exhibition that I am curating with Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool, scheduled to open in spring 2020.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Adam Murray: Can you explain the story behind this collection of photographs?

Yvonne Taylor: The photographs are from the period around 1977–84. At the time I was living in Doncaster, living at home with my mum in a mining village, and worked at Doncaster Council.

At the end of 1977 I started going out to Outlook Club in Doncaster, which on Monday nights featured different kinds of bands. This became a really important club in my life, as it changed the way I looked at fashion and music. The love of music and dance and fashion was what inspired me to start sourcing clothes that were different. At the time, there was no fashion shops like there is now—there was only things like C&A and Chelsea Girl. The main source of my clothes came from jumble sales, or from raiding my mum’s and my grandma’s wardrobe.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: When did you first start becoming aware of the importance of photography to you?

Taylor: I don’t have a lot of photographs from the early days, because basically I didn’t own a camera. Not everybody had cameras of their own and we certainly didn’t take them with us when we went out. But something that did make me start thinking more about image and how you looked was the emergence of fanzines. I’d made friends with a lad called Stephen Singleton, from Sheffield, who was in a band at the time and later became part of ABC. He wrote a fanzine and used to put photographs in of his friends. They were all in black and white, just printed on a local printer. But it made us start to think about how we looked. We would be inspired by other people and how they looked in magazines, which were starting to documenting real people, not celebrities or film stars and pop stars that we’d seen in magazines before then.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: What was your relationship with Dennis?

Taylor: I met Dennis in 1978, when punk was slowly dying and we needed something to take its place, and along came what is now called New Romantics. That was very fashion-focused; it was important to look different, to be as unique as possible, so I started making clothes. Sometimes I only adapted things, or changed the buttons or added a bit of fur to make it look different. We wanted to keep a record of that, so I bought Dennis a camera. Dennis was really into fashion and it was important to him how he looked, and he loved taking photographs of me. He liked to have photographs in his room of me. We didn’t live near each other—he lived in Scunthorpe, he worked on the steelworks, got grotty and dirty, came home, changed into somebody different, and it was documented in the photographs. There was photographs all over his room; he was an artist, he liked drawing, and he’d get inspired by taking photographs and then making them into drawings.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Did you take a lot of photographs?

Taylor: Later on, when I got my own camera, I’d set up little sets, scenes, and I took photographs of my friend Carol modeling some of the outfits that I’d made. I wanted to be able to look back and think, this was me then. The photographs represent a really happy time in my life, a time that was filled with love, when I first met Dennis, and the excitement of going to new places and meeting new people.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Amelia, when did you first become aware of Yvonne’s and Dennis’s archive?

Amelia Lonsdale: Mum and Dennis both took a lot of photographs, and until Dennis passed away in the late 1990s, they were kept separately. When a friend was clearing Dennis’s house, he came across a box labeled “In result of my death please return to Yvonne Taylor.” So, he took them back to my mum, and there were old pictures of her, love letters that they’d sent to each other. Until that point there were a lot of pictures that she hadn’t seen for fifteen to twenty years, so that was really special for her.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Has the archive changed since you became more involved with it?

Lonsdale: I don’t think my mum has understood herself how special the archive is until now, since I’ve started talking to her about the photographs and other people have shown an interest. So for me to be able to provide a platform for her to realize that is the most important thing for me. I would like to make a publication, but I really want to do it justice. I don’t want to rush into anything. It’s important to me that I do it right because it’s such a big responsibility. Even more so than my own photographs that I’ve actually taken.

I’ve taken pictures for as long as I can remember, and I ended up studying photography and becoming a photographer, so the archive has had an influence on me that way. In the last five years, as I’ve started really looking into the pictures, they’ve helped me understand why people take pictures, and that’s become more interesting to me than actually taking photographs.

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: How do you feel about the archive being displayed in public?

Lonsdale: It makes me really proud of my mum. It’s crazy because, while obviously there’s elements of the woman I know now in the photos, and although she’s always been the life of the party and she’s always been into fashion, it still feels when I look at them like I’m looking at someone I don’t know.

Adam Murray is a lecturer at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, and Manchester Metropolitan University.

The post Looking Back at the New Romantics appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Surrogate for Love

What can the doll community tell us about relationships today?

By Melissa Harris

Elena Dorfman, CJ 3, 2002

© and courtesy the artist

Artists Jamie Diamond and Elena Dorfman picture the intimate familial, and at times romantic and sexual relationships between people and synthetic human dolls. On the occasion of their joint exhibition in Milan, Surrogati. Un amore ideale, they spoke with curator Melissa Harris about stigma, the doll community, and redefining love.

Melissa Harris: Based on my conversations with some of your respective subjects, they seem to accumulate, to embrace many dolls in their lives. Where does the collecting impulse play into this, do you think?

Elena Dorfman: I think it’s about making a community, a family. And, in the case of the people I photograph, also about attaining a sexual partner or partners.

Jamie Diamond: When I say, “collecting,” I think that word is being appropriated from history—from the idea of doll collecting. It’s changed considerably within this community: It’s the creation and gathering together of surrogates. Take for example the terminology of “portrait babies”— dolls made based on old photographs of a childhood past. Essentially when a child has died—that’s a big part of the idea of surrogacy. Or there are women who can’t have any more children because of illness or age, or women who for various reasons can never have children.

Jamie Diamond, 4.12.12, 2012

© and courtesy the artist

Dorfman: In the doll community I focus on, they were generally surrogates for flesh and blood women that for whatever reason eluded the men. They were also fantasy women and muses. In the case of the image of the doll in the church, Rob was writing a novel, and Lily was his muse. His novel had to do with the church and spirituality, so I asked if he was willing to take her to church. That was always my process—I asked the men what they did with the dolls on a day-to-day basis, or what they would like to do with them. Taking her to church, however, was nearly a disaster. These dolls are very heavy, and complicated and cumbersome to move, so physically navigating her into a house of worship was challenging.

Harris: Were there other people in the church at the time?

Dorfman: Yes, there were.

Harris: Did anybody know this was a part of his life?

Dorfman: Absolutely not. But he was willing to take her out of the house in order to try to overcome the stigma that doll owners face, to move beyond the walls of his house.

Elena Dorfman, Ginger Brook 4, 2001

© and courtesy the artist

Harris: Jamie, do those with reborn dolls feel similarly stigmatized?

Diamond: Outsiders make assumptions and may think that these women are crazy. But I’ve never met a woman in this community who thinks their doll is real, regardless of her behavior. The women might treat it as if it’s real, but they know the difference. In fact, most of the women I’ve met are kind, generous, nurturing, and very much in touch with reality. There is genuine feeling here, far beyond fantasy or role-play.

Harris: There seems to be a certain amount of common ground shared by your two projects, synergy between their emotional and psychological underpinnings. Many of your subjects I spoke with made an analogy to having a pet. We use that word “anthropomorphize”—the way people converse with or refer to animals and their emotional lives as if they are human, but even in these instances, they’re still interacting with a living creature. How does all this happen with synthetic creatures? How do we bestow human qualities, a type of life itself, on the inorganic?

Dorfman: In the case of the sex dolls, they are so lifelike that they fall into the uncanny valley. My experience was that in order to live with a silicone surrogate over an extended period of time, to devote so much of your life, energy, and finances to her (these dolls are expensive), she has to be given a life story, which nearly every man conjured.

Diamond: It’s the same for my subjects on so many levels. What’s interesting to me is while making the dolls, I knew I was done when I had that visceral response … when I felt the urge to hold it. Something gets triggered. It’s hard to articulate because it’s just something that you feel so deeply within yourself, that it feels real.

Jamie Diamond,5.28.12, 2012

© and courtesy the artist

Dorfman: But this fantasy is also a reflection of technology and artistry. The dolls look so realistic it makes it easier for them to “pass” as real women. This wasn’t so true when I began nearly twenty years ago. The world we live in today, where the norms of beauty are shifting and the demand that women stay eternally youthful becomes increasingly urgent—this, combined with medical and technological advances, and more sophisticated techniques applied to the creation of plastic women, blur the line between flesh and silicone even more.

Harris: What’s interesting to me about both of your projects is that they challenge so many preconceptions about sex and love and relationships, family and motherhood. They are remarkably open-ended emotionally and psychologically.

Dorfman: For the most part, the doll owners I worked with had a certain level of emotional depth, self-awareness, and self-knowledge. I was often surprised and constantly rubbing up against my own ideas of what constitutes love—and what kind of person lives with a love doll as his or her domestic partner. My preconceptions were regularly shattered.

Elena Dorfman,Sidore 4, 2001

© and courtesy the artist

Harris: Do you consider these projects documentary in nature?

Dorfman: Yes. For this series, I documented the domestic lives of men and women who live with life-sized, anatomically correct, sex dolls.

Diamond: My work has always been rooted in fiction while examining the disparity between image and reality. I use photography and staged intimacy as a vehicle to question existing values regarding inherited social and gender expectations. “Forever Mothers” is interesting for me in that there is a level of reality that never existed before in my work. Everything prior to this was very much a construction that I was producing for the camera.

Jamie Diamond, Mother Marilyn, 2012

© and courtesy the artist

Harris: Let’s talk about the history of the arts and literature—dolls are omnipresent. Why is that? There’s something about not being quite sure what you’re looking at, that is fascinating. Both of you, I know, have various references, visual references—not even necessarily for your own work, but in terms of how you contextualize your subject.

Diamond: Think of Morton Bartlett. Part of what I find interesting is his fetishization of the doll. He’s basing them on children, but there’s something maybe a little perverse about how he’s representing them. But his obsession—the fact that he’s sculpting these anatomically complete dolls, dressing them and then photographing them (although sometimes they are naked in the photographs)—is fascinating. You don’t know exactly what you are looking at.

Dorfman: While making “Still Lovers,” I became aware of the role that automatons and dolls have played throughout mythology and art history. Of particular intrigue was Thomas Edison’s Phonograph Doll, from 1877—a twenty-two-inch doll that played a single nursery rhyme; Oskar Kokoshka’s 1918 stuffed replica of Alma, his estranged lover; the contorted, life-sized pubescent figures and photographs by Hans Bellmer; and, the myths of Pygmalion, and Pandora—the perfect woman created by the Gods, with the purpose of destroying mankind. Women’s roles have always been complicated, as they embody both the expression of and end to Paradise.

Elena Dorfman, Rebecca 1, 2001

© and courtesy the artist

Diamond: Regarding our projects, there are parallel narratives here that are intriguing, each involving genuine human emotion, but within a shifting set of parameters, as the dolls become more and more lifelike, and what they represent shifts.

Dorfman: At first glance, it may be easy for viewers to characterize our subjects as peculiar, or in some way deviant. But, while their chosen lifestyles or hobbies might be out of the ordinary, they pose myriad and fascinating questions about the intersection of fantasy and reality, and shed light on the human condition now—and in the future.

Melissa Harris is editor at large of Aperture Foundation and the author of A Wild Life: A Visual Biography of Photographer Michael Nichols (Aperture, 2017).

This interview is excerpted from Surrogati: Un Amore Ideale (Surrogate: A Love Ideal), in Quaderno #23, Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2019, in conjunction with an exhibition on view at Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio, in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, Milan, from February 21–July 22, 2019.

The post A Surrogate for Love appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

February 21, 2019

Bisi Silva Changed the Way We See African Photography

Through her ambitious curating, writing, and teaching in Africa and beyond, Silva was a force for change in contemporary art.

By Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Bisi Silva, New York, 2016

Photograph by Gabriela Herman/The New York Times/Redux

When the time comes to reflect on the titans who shaped the course of photographic practice in Africa during the early twenty-first century, the name Bisi Silva, who died last week in Lagos, will be writ large, emphasized in bold. Over more than twenty-five years in the field of contemporary art and photography, her remarkable vision and indefatigable spirit instigated tectonic shifts in editorial, curatorial, and institutional frameworks in Nigeria and across the African continent. A curator trained at the Royal College of Art in London, and a contributor to publications including Artforum, Third Text, and Art Africa, Silva responded to the flows of the global, but was ultimately grounded in a granular treatment of the local, which she defined as “an expanded field of practice and engagement.” Situating her curatorial practice within Nigeria, Silva founded the nimble, impactful organization that is the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) Lagos in 2007, which provides a platform for the development, presentation, and discussion of visual art and culture. Her CCA Lagos exhibitions included Democrazy (2007–8), Lucy Azubuike and Zanele Muholi: Like a Virgin (2009), and Kelani Abass: If I Could Save Time (2016–17), among many others.

In 2011 Silva organized Moments of Beauty, the first comprehensive survey exhibition of Nigerian photographer J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (1930–2014), at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Kiasma, Helsinki, initiating a period of long-term engagement with Ojeikere’s dynamic body of work. During 2012–13, she initiated The Progress of Love, a transcontinental collaboration between Houston’s Menil Collection, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in Missouri, and CCA Lagos, which explored evolving modes and significations of love through work by artists from across Africa, Europe, and the United States. The year 2014 found Silva curating Playing with Chance, an in-depth solo exhibition on El Anatsui at CCA Lagos, which drew deeply on archival and photographic material from Anatsui’s studio. She also served as a member of the international jury for the 2013 Venice Biennale, the Pinchuk Art Centre’s 2014 Future Generation Art Prize, and the 2018 Hugo Boss Prize.

A tireless tour de force, Silva organized the Second Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, Greece (2009), cocurated the seventh Dak’Art Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain, Senegal (2006), and served as the artistic director of the tenth Rencontres de Bamako, Biennale Africaine de la Photographie (2015). Entitled Telling Time, Silva positioned the biennale—in collaboration with associate curators Yves Chatap and Antawan I. Byrd—as a space to explore the multiple valences of temporality within a Malian context, featuring a dizzying number of experimental and exciting approaches from artists based across the African continent and throughout the African diaspora. Including a focus on Lusophone African photography, a core engagement with Malian studio photography archives, and ambitious visual literacy initiatives, she amplified the scope of what kinds of curatorial, programmatic, pedagogical, and artistic modes could be engaged through a photography biennale’s mandate.

Yet beyond these direct interventions and contributions, what Silva has done for the fields of contemporary art and photographic practice might be felt in the most embodied manner through the six cohorts of curators, photographers, and artists that she cultivated from 2010 to 2016 through the Àsìkò International Art Programme, a pioneering pedagogical model that employs a nomadic framework to stage intensive workshops for artists and curators across the African continent. Nurturing dialogues between emerging practitioners as well as invited international guest artists, scholars, curators, and cultural administrators, Àsìkò stimulates critical and conceptual thought, while also spurring meaningful dialogue, exchange, and collaboration. It also provides a vital space within the field of contemporary artistic practice where the perspectives of those working within the African continent are foregrounded first and foremost.

Moussa Kalapo, Métaphore du temps, 2015

© the artist

Silva was also a record keeper—a librarian, an archivist, an editor. As an extension and constitutive element of her curating, she concentrated on the importance of accumulating and caring for visual histories through publications. At CCA Lagos she accrued what is now the largest photographic and visual arts library in Nigeria, a collection of photobooks, artist monographs, theoretical texts, exhibition catalogues, historical accounts, and journals numbering in the hundreds. Silva’s 2015 monographic publication on Ojeikere stands as a rich tome of photographic research, featuring more than two hundred images taken over more than sixty years, ranging from his typological survey of Nigerian hairstyles to his architectural studies of Lagos. The accompanying catalogue for Silva’s iteration of the Bamako Biennale featured not only original texts and beautifully executed spreads for each of the artists in the festival, but also a detailed timeline and complete reprint of the catalogue for the biennale’s inaugural 1994 edition. With an editorial team of twenty contributors, Silva offered a cogent point of entry for considering the historical framework of the biennale and contemporary photographic practice within Africa.

In 2017 Silva published Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa, a volume that documented the six iterations of the program and indexed the reflections of the seventy cultural producers that participated in the program. Edited and designed in collaboration with Stephanie Baptist, Nontsikelelo Mutiti, and Julia Novitch, the book emulated the multivalent nature of the program by incorporating archival materials and documentation from each edition alongside a number of critical and theoretical essays, interviews, and artistic works. The same year, Silva was also a guest editor for Aperture’s “Platform Africa” issue, where, alongside coeditors John Fleetwood and Aïcha Diallo, she tracked the various sites and spaces across the continent that inform contemporary photography in Africa. A true luminary, she enriched and sustained the field of contemporary art and photography tenfold.

In the process of writing this piece, I returned to old notebooks, catalogues and exhibition leaflets, saved bookmarks, program ephemera, and extended email threads—all in an attempt to pinpoint precisely when Bisi Silva entered my life. As often is the Nigerian way, we were connected through family. She was generous from the start, and through her guidance, I learned the importance of retaining an astute eye, an ambitious scope, a sensitivity to tracking artistic growth, and a set of standards predicated on asking the hard questions—of myself, my collaborators, and the photographic medium itself. It is a point of pride to note that this experience of being mentored by Silva is not particularly unique to me. She has equipped countless individuals with the tools to make room in this field for thoughtful, critical consideration of photographic practice on the African continent. Across varied contexts, time zones, and geographic spaces, Silva pursued her work with rigor and care, with an exuberance for the present and a deep respect for history. Writing in Telling Time in 2015, Silva quoted the griot Kouyaté: “I teach kings the history of their ancestors so that the lives of the ancients might serve them as an example, for the world is old, but the future springs from the past.”

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is a curator and scholar of photography and the arts of Africa. The former director of exhibitions and collections at the Walther Collection, she is a doctoral candidate in art history at Columbia University.

The post Bisi Silva Changed the Way We See African Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Bamako Revisited

The legacy of Mali’s influential photography biennial.

By Bisi Silva

Oumou Diarra, Les Chasseuses de Bazin, 2016

Courtesy the artist

In 1998, I traveled to Bamako for the first time to attend the third edition of Bamako Encounters: African Biennale of Photography. At the time, I was an independent curator based in London, and was thus humbled and refreshed to learn that a space existed on the continent for presenting the work of photographers of African descent—many of whom had yet to gain recognition in the West. Since that eye-opening experience, I’ve followed the evolution of the Bamako Biennale, the longest running platform for photography in Africa, by attending nearly every subsequent edition in various capacities—as a spectator, presenter, curator, and, most recently, in 2015, as the artistic director for the tenth edition.

Titled Telling Time, this edition marked a milestone in the Biennale’s history on a number of levels. Not only was it celebrating the tenth anniversary of the event, but Telling Time also heralded the Biennale’s return after a four-year period of absence due to the political instability and threats to Mali’s sovereignty brought about by the jihadist insurgency of 2012. This confluence of political upheaval and cultural expression dates back to the very conception of the event. Mali’s first democratically elected president, Alpha Oumar Konare, staunchly supported the Biennale’s founding in 1994, envisioning it as an opportunity to test the capacity of culture to rehabilitate the nation’s image and restore international confidence following decades of violent authoritarian rule under Moussa Traore. For the tenth edition, local stakeholders renewed their investments in the power of culture by once again positioning the Biennale as a tool for strengthening Mali’s fragile democracy and increasing its international visibility.

Youcef Krache, Untitled, March 13, 2015

Courtesy the artist and Collective 220

I view my role in the tenth edition as part of the efforts to reinvigorate the local, insofar as the responsibilities granted to me marked the first time in the Biennale’s history that a curator based in the region (in 2007 I founded the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos) was chosen as the artistic director. Intimately familiar with the Biennale’s history and evolution, I accepted the challenge of devising an expansive program that would honor the event’s influence, question its place and relevance to current lens-based practices and discourses in Africa, and proffer possibilities for the Biennale’s future. This multiplicity of perspectives animated the conception and execution of the tenth edition’s focus on questions of time and of the local.

The coexistence of different temporalities is a defining characteristic of Bamakois urbanism. Bamako is a place where the past unavoidably engenders a symbiotic meeting with the present, a place where tradition and heritage are at one with modernity. From these perspectives, I consider Bamako a “city village” where tall modern buildings rise in close proximity to modest residential dwellings of neotraditional design, and modern cars mingle, at times, with animal-driven carts. While these characteristics make Bamako an ideal site for discursive exhibition platforms, it should be noted that Mali is one of the least economically prosperous countries in the region. On first sight it lacks the infrastructure to host international art happenings: there exist no degree-granting educational establishments providing photography courses at any level; there is virtually no collector base; and there are no major art-publishing initiatives, to name a few enabling prerequisites.

Moussa Kalapo, Métaphore du temps, 2015

© the artist

But Mali has a deep cultural past with a long and strategic history. By the fourteenth century, the University of Sankore in Timbuktu had established Mali as an internationally renowned site for Islamic study, with ancient manuscript traditions dating back to the eleventh century. It is the land of the griots and the country of the Dogon people, and of the fourteenth-century magnificent mud mosque in Djenne. Its empires and its emperors, such as Sundiata Keita and Mansa Kankan Musa, are legendary. Malians today remain fiercely proud as well as protective of this cultural heritage. Even in the absence of purpose-built contemporary art venues in Bamako, the Biennale benefits from adequate venues like the Palais de la Culture, the main site of the Biennale before its transition to the National Museum of Mali; the Musée du District de Bamako; the Modibo Keita Memorial Centre; and smaller informal spaces around the city. With this structure, it is no surprise that Bamako would stake a claim as the “capital of photography” on the continent, a status that endures but that may be undermined by increasingly inadequate official support.

The Bamako Biennale started in 1994—founded by French photographers Françoise Huguier and Bernard Descamps—two years after the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal positioned itself as a forum dedicated to contemporary art. Both can be considered the result of the proliferation of mega-exhibitions and biennials that were springing up in so-called margin locations around the world in the 1980s and 1990s. But most importantly, these two events were responding to the absence of platforms for African artists within and outside of the continent, and to the visibility of the growing number of artists working in Africa and the diaspora. They provided important meeting points for artists, curators, writers, editors, and other art professionals to meet, interact, and exchange.

Alpha Oumar Konare, opening ceremony at the first Bamako Biennale of African Photography, 1994

© Archives de l’Agence Malienne de Presse et de Publicité, Bamako (AMAP)

Consequently, the Bamako Biennale, through its focus on photography, has directly and indirectly spurred a plethora of lens-based platforms and smaller initiatives across the continent. One of the earliest, though short-lived, was the Rencontres du Sud (Southern Encounters), started by Ivorian photographer Ananias Léki Dago in 2000. Other events included Rencontres Picha, in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, started by Congolese artist Sammy Baloji in 2008; Addis Foto Fest, founded by Ethiopian photographer Aida Muluneh in 2010; and LagosPhoto, developed by Nigerian cultural entrepreneur Azu Nwagbogu, also in 2010. These events have been supplemented by new artist collectives such as Invisible Borders, a pan-African collective of photographers and writers who travel by road across Africa, as well as new educational programs and workshops that have manifested

Unlike the major biennials, which often become instruments of governmental politics, the foregoing artist-led initiatives are grassroots organizations that have been cultivated from the ground up, providing training and professional development—in the absence of appropriate education initiatives—with exhibition-making. In addition, they impose no geographical limitations to participation, arguing that international or transnational integration takes cognizance of global parameters.

Despite the profusion of platforms in Africa, which are poised to continue, it becomes necessary to question whose interests are ultimately served through the development of these initiatives, and how, if at all, they harness local infrastructural growth with international visibility. When the Bamako Biennale began, it had a local premise. It symbolized the nation’s embrace of democracy and was supported by President Konare, who understood the role culture could play after the end of a prolonged dictatorship. However, there were tensions from the beginning as to what a French-Malian partnership might look like. From the outset, France played an integral role in the production of the Biennale. Although Mali is now more involved in management decisions, the French have been criticized for their neocolonial relationship regarding the event. Nevertheless, the original aims, which sought to foster collaborations and develop the embryonic field of African photography, as well as the local scene, have seen tremendous success.

Aboubacar Traore, Inchallah, 2015

Courtesy the artist

There have been many local beneficiaries of the Biennale, some more successful than others. In the early editions, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, already with burgeoning international careers, were catapulted into foreign museums, galleries, and collections. In 1994, the Malian government announced its intention to found the Maison Africaine de la Photographie—finally created in 2004—to strengthen the presentation and dissemination of photography across Mali and neighboring countries. Education centers, especially the Cadre de Promotion pour la Formation en Photographie (CFP), established in 1998 and generously funded by Helvetas Mali, produced a new generation of photographers. Promo-femme: Center for Audio Visual Education for Young Women was created in 1996 to develop and nurture the first generation of women photographers, including Fatoumata Diabate, Amsatou Diallo, Alimata Traore, and Penda Diakite (who opened her own studio in 2002, considered the first by a woman in Mali). Over the course of its existence, numerous women were trained and some participated in the Biennale, such as Diabate, who won the Afrique en Création prize during the 2005 edition and has since gone on to develop her career internationally.

Seydou Keïta at the opening of his first solo exhibition in Mali, Bamako Biennale, December 1994

© Érika Nimis