Aperture's Blog, page 82

September 20, 2019

The 2019 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

Aperture and Paris Photo are pleased to announce the shortlist for the 2019 PhotoBook Awards.

Marwan Bassiouni, New Dutch Views (Lecturis) Eindhoven, Netherlands

Marwan Bassiouni, New Dutch Views (Lecturis) Eindhoven, Netherlands

Michele Borzoni, Workforce (L’Artiere) Bologna, Italy

Michele Borzoni, Workforce (L’Artiere) Bologna, Italy

Juan Brenner, Tonatiuh (Editorial RM) Barcelona

Juan Brenner, Tonatiuh (Editorial RM) Barcelona

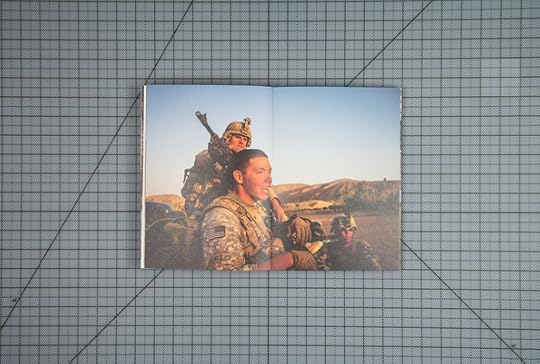

Ben Brody, Attention Servicemember (Red Hook Editions) Brooklyn

Ben Brody, Attention Servicemember (Red Hook Editions) Brooklyn

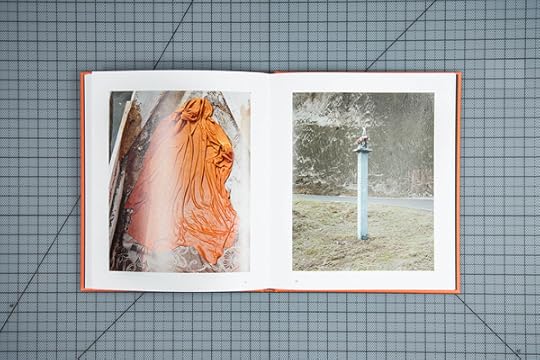

Maisie Cousins, Rubbish, Dipping Sauce, Grass Peonie Bum (Trolley Books) London

Maisie Cousins, Rubbish, Dipping Sauce, Grass Peonie Bum (Trolley Books) London

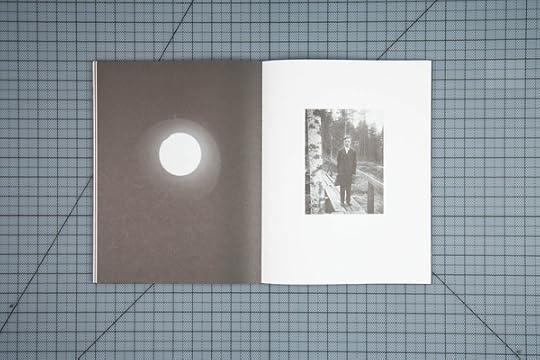

Maja Daniels, Elf Dalia (MACK) London

Maja Daniels, Elf Dalia (MACK) London

Federico Estol, Héroes del Brillo (Hormigón Armado and El Ministerio Ediciones) La Paz, Bolivia

Federico Estol, Héroes del Brillo (Hormigón Armado and El Ministerio Ediciones) La Paz, Bolivia

Tania Franco Klein, Positive Disintegration (Editions Bessard) Paris

Tania Franco Klein, Positive Disintegration (Editions Bessard) Paris

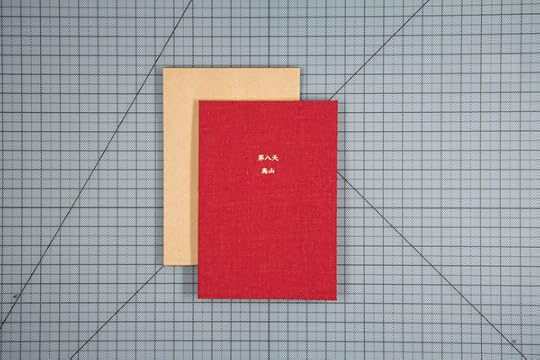

Gao Shan, The Eighth Day (Imageless, Wuxi) China

Gao Shan, The Eighth Day (Imageless, Wuxi) China

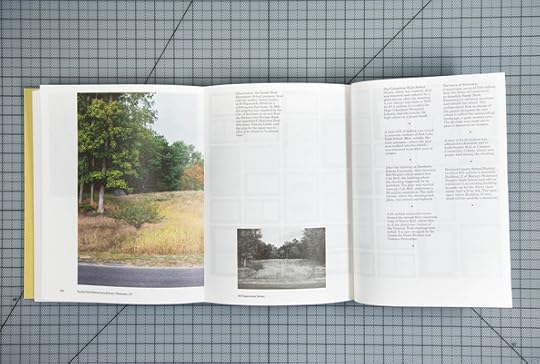

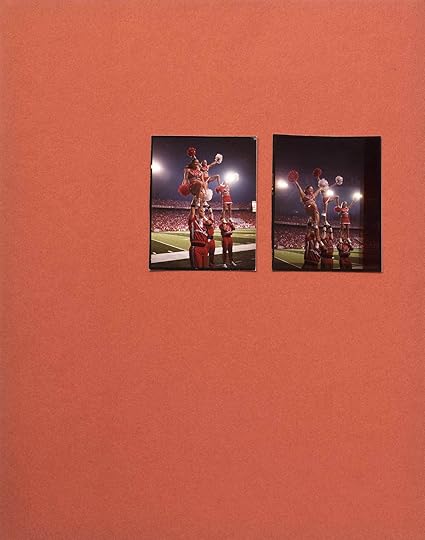

Andres Gonzalez, American Origami (Fw:Books) Amsterdam

Andres Gonzalez, American Origami (Fw:Books) Amsterdam

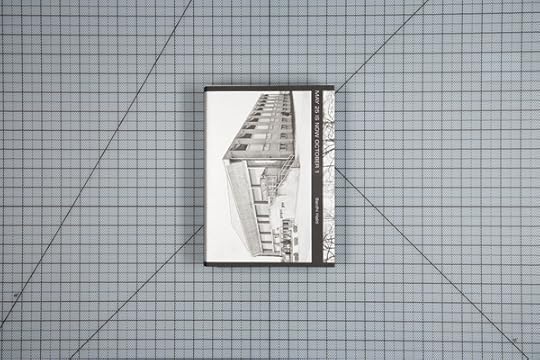

Bardhi Haliti, May 25 is now October 1 (Cpress) Zürich

Bardhi Haliti, May 25 is now October 1 (Cpress) Zürich

Csilla Klenyanszki, Pillars of Home (Self-published) Amsterdam

Csilla Klenyanszki, Pillars of Home (Self-published) Amsterdam

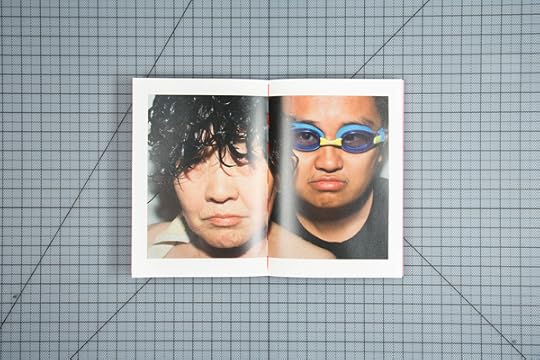

Lam Pok Yin & Chong Ng, The Untimely Apparatus of Two Amateur Photographers (Jiazazhi) Ningbo, China

Lam Pok Yin & Chong Ng, The Untimely Apparatus of Two Amateur Photographers (Jiazazhi) Ningbo, China

Guy Martin, The Parallel State (GOST Books) London

Guy Martin, The Parallel State (GOST Books) London

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, A Ukraine Runs Through It (Pix.house) Poznań, Poland, and Tbilisi, Georgia

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, A Ukraine Runs Through It (Pix.house) Poznań, Poland, and Tbilisi, Georgia

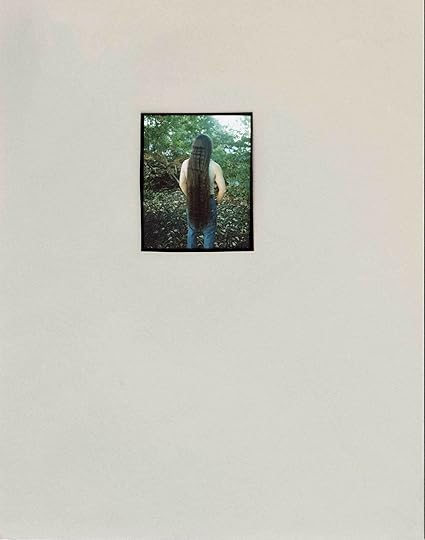

Drew Nikonowicz, This World and Others Like It (Fw:Books & Yoffy Press) Amsterdam & Atlanta

Drew Nikonowicz, This World and Others Like It (Fw:Books & Yoffy Press) Amsterdam & Atlanta

Adam Pape, Dyckman Haze (MACK) London

Adam Pape, Dyckman Haze (MACK) London

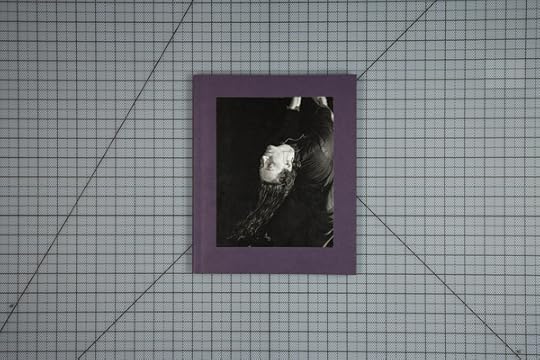

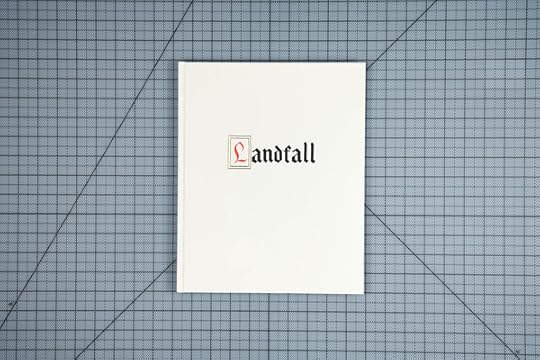

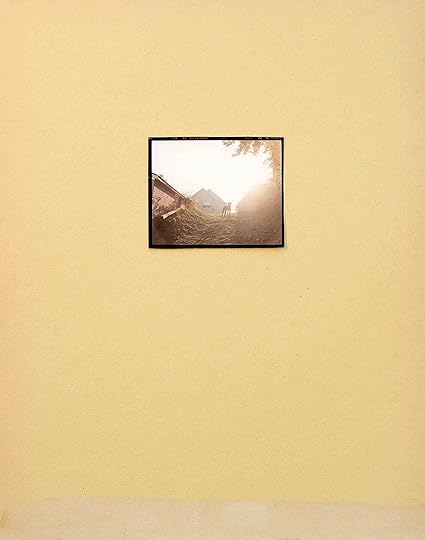

Mimi Plumb, Landfall (TBW Books) Oakland, California

Mimi Plumb, Landfall (TBW Books) Oakland, California

Guadalupe Rosales, Map Pointz (Little Big Man Books) Los Angeles

Guadalupe Rosales, Map Pointz (Little Big Man Books) Los Angeles

Karla Hiraldo Voleau, Hola Mi Amol (SPBH Editions & ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne) London & Renens, Switzerland

Karla Hiraldo Voleau, Hola Mi Amol (SPBH Editions & ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne) London & Renens, Switzerland

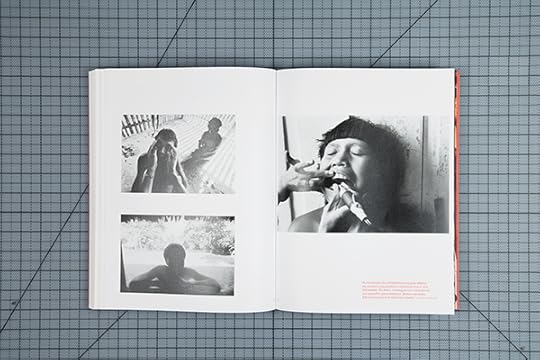

Claudia Andujar, Claudia Andujar: a luta Yanomami (Instituto Moreira Salles) São Paulo

Claudia Andujar, Claudia Andujar: a luta Yanomami (Instituto Moreira Salles) São Paulo

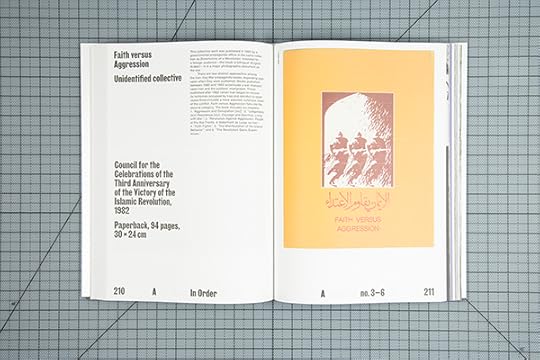

Hannah Darabi, Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, and LE BAL, Paris)

Hannah Darabi, Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, and LE BAL, Paris)

Michael Jang, Who is Michael Jang? (Atelier Éditions) Los Angeles

Michael Jang, Who is Michael Jang? (Atelier Éditions) Los Angeles

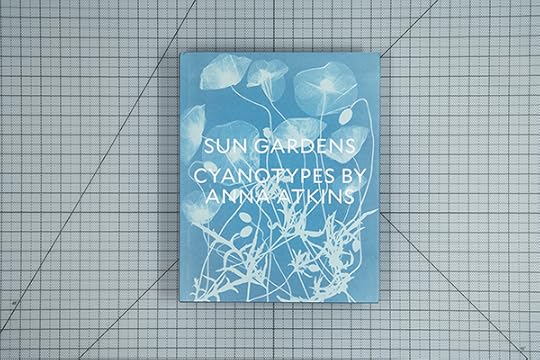

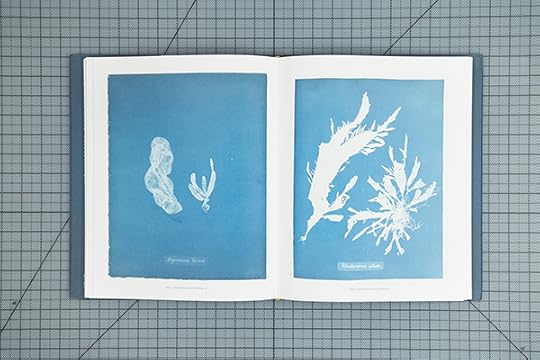

Larry J. Shaaf, Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins (Prestel Publishing) New York

Larry J. Shaaf, Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins (Prestel Publishing) New York

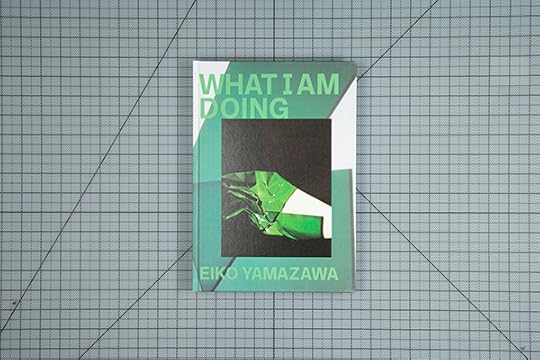

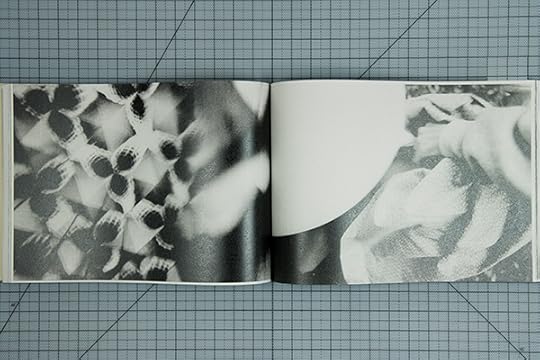

Eiko Yamazawa, What I Am Doing (AKAAKA Art Publishing) Kyoto

Eiko Yamazawa, What I Am Doing (AKAAKA Art Publishing) Kyoto

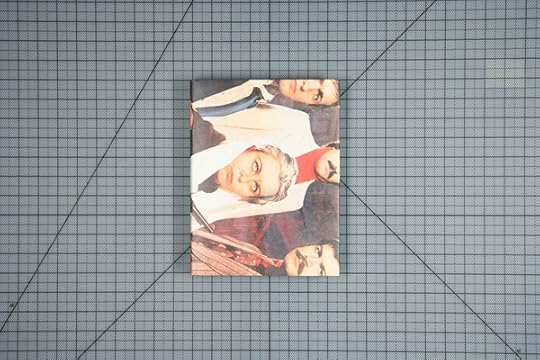

Vince Aletti, Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines (Phaidon) New York

Vince Aletti, Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines (Phaidon) New York

Emi Anrakuji, Balloon Position (AKAAKA Art Publishing) Kyoto

Emi Anrakuji, Balloon Position (AKAAKA Art Publishing) Kyoto

![Cover, George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1508432571i/24213365.png)

![Cover, George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1569072613i/28181901._SX540_.jpg)

George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom

![Spread, George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1508432571i/24213365.png)

![Spread, George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1569072613i/28181902._SX540_.jpg)

George Georgiou, Americans Parade [BB Editions (Self-published)] Folkestone, United Kingdom

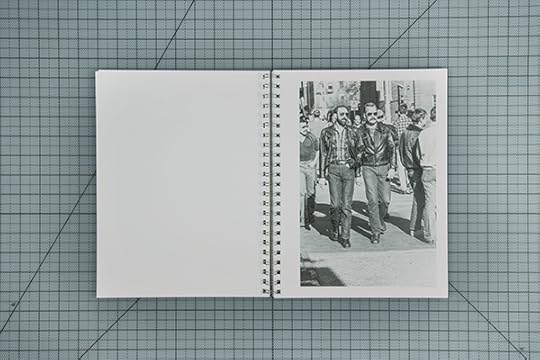

Sunil Gupta, Christopher Street, 1976 (STANLEY/BARKER) London

Sunil Gupta, Christopher Street, 1976 (STANLEY/BARKER) London

![Cover, Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1508432571i/24213365.png)

![Cover, Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1569072613i/28181905._SX540_.jpg)

Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India

![Spread, Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1508432571i/24213365.png)

![Spread, Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1569072613i/28181906._SX540_.jpg)

Sohrab Hura, The Coast [Ugly Dog (Self-published)] New Delhi, India

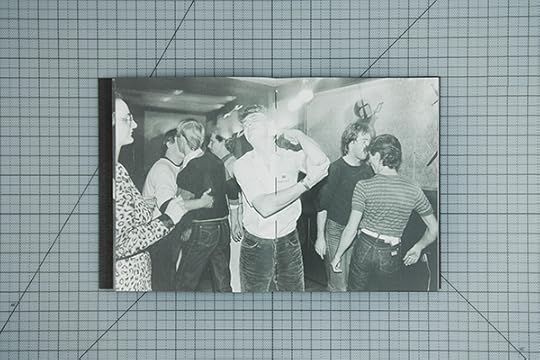

Libuše Jarcovjáková, EVOKATIV (Untitled) Prague

Libuše Jarcovjáková, EVOKATIV (Untitled) Prague

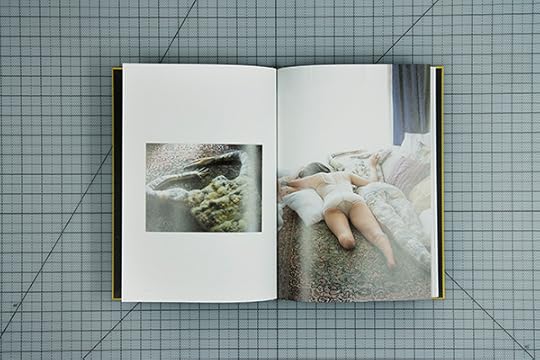

Mari Katayama Gift (United Vagabonds) Tokyo

Mari Katayama Gift (United Vagabonds) Tokyo

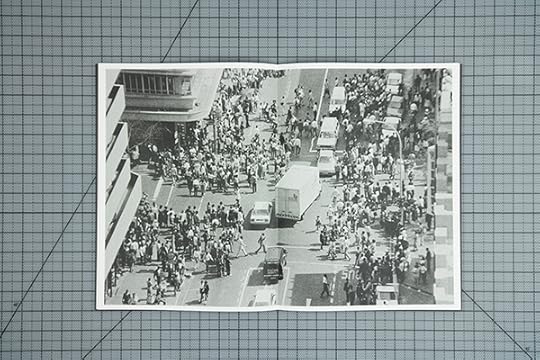

Santu Mofokeng, Stories (Steidl) Göttingen, Germany

Santu Mofokeng, Stories (Steidl) Göttingen, Germany

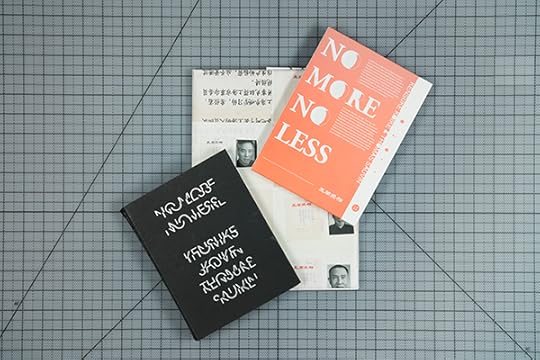

Thomas Sauvin and Kensuke Koike, No More No Less (the(M) éditions, Paris; Skinnerboox, Jesi, Italy; and Jiazazhi, Ningbo, China

Thomas Sauvin and Kensuke Koike, No More No Less (the(M) éditions, Paris; Skinnerboox, Jesi, Italy; and Jiazazhi, Ningbo, China

Henk Wildschut, Rooted (Self-published) Amsterdam

Henk Wildschut, Rooted (Self-published) Amsterdam

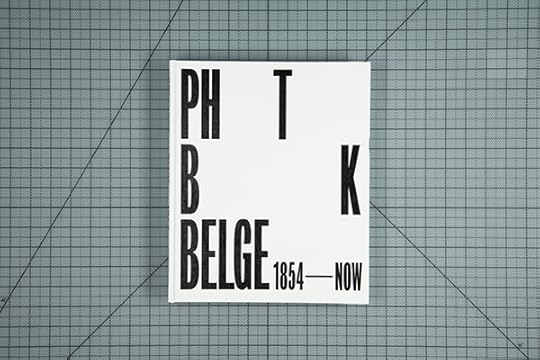

Tamara Berghmans, ed., Photobook Belge: 1954–Now (Hannibal Publishing) Belgium

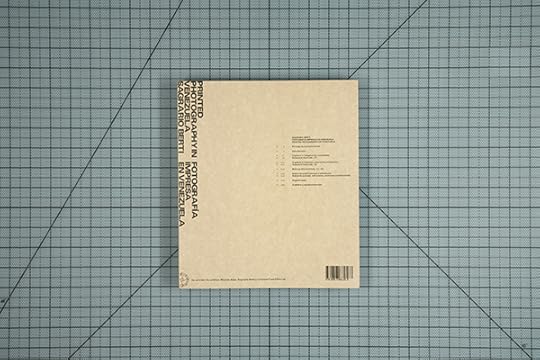

Sagrario Berti, Printed Photography in Venezuela (Ricardo Báez, Sagrario Berti, and La Cueva Casa Editorial) Venezuela

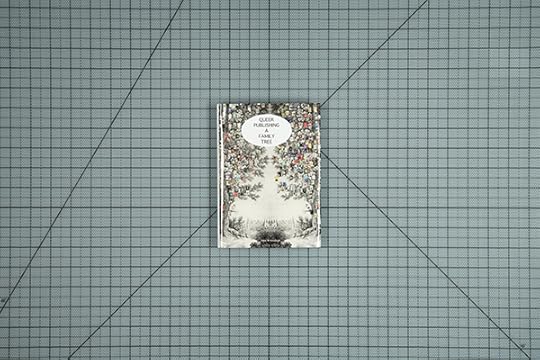

Bernhard Cella and Orlando Pescatore, Queer Publishing: A Family Tree (Salon für Kunstbuch) Vienna

Manfred Heiting, ed., Czech and Slovak Photo Publications, 1918–1989 (Steidl Publishers) Germany

Russet Lederman, Olga Yatskevich, and Michael Lang, eds., How We See: Photobooks by Women (10x10 Photobooks) New York

Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Camera Austria International: Laboratory for Photography and Theory (Spector Books) Leipzig, Germany

Paul Wolff and Alfred Tritschler, Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler: Light and Shadow—Photographs 1920 to 1950 (Kehrer Verlag) Germany

Facundo de Zuviría, Inner World: Modern Argentine Photography 1927–1962 (Fundación Malba) Buenos Aires

The shortlist selection was made Amanda Maddox, associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Joanna Milter, director of photography at the New Yorker, Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum, Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review, and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

Established in 2012, the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards celebrate the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography, with three major categories: First PhotoBook, Photography Catalogue of the Year, and PhotoBook of the Year.

First PhotoBook

Marwan Bassiouni

New Dutch Views

Lecturis, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Michele Borzoni

Workforce

L’Artiere, Bologna, Italy

Juan Brenner

Tonatiuh

Editorial RM, Barcelona

Ben Brody

Attention Servicemember

Red Hook Editions, Brooklyn

Maisie Cousins

Rubbish, Dipping Sauce, Grass Peonie Bum

Trolley Books, London

Maja Daniels

Elf Dalia

MACK, London

Federico Estol

Héroes del Brillo

Hormigón Armado and El Ministerio Ediciones, La Paz, Bolivia

Tania Franco Klein

Positive Disintegration

Editions Bessard, Paris

Gao Shan

The Eighth Day

Imageless, Wuxi, China

Andres Gonzalez

American Origami

Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Bardhi Haliti

May 25 is now October 1

Cpress, Zürich

Csilla Klenyanszki

Pillars of Home

Self-published, Amsterdam

Lam Pok Yin and Chong Ng

The Untimely Apparatus of Two Amateur Photographers

Jiazazhi, Ningbo, China

Guy Martin

The Parallel State

GOST Books, London

Justyna Mielnikiewicz

A Ukraine Runs Through It

Pix.house, Poznań, Poland, and Tbilisi, Georgia

Drew Nikonowicz

This World and Others Like It

Fw:Books, Amsterdam, and Yoffy Press, Atlanta

Adam Pape

Dyckman Haze

MACK, London

Mimi Plumb

Landfall

TBW Books, Oakland, California

Guadalupe Rosales

Map Pointz

Little Big Man Books, Los Angeles

Karla Hiraldo Voleau

Hola Mi Amol

SPBH Editions, London, and ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne, Renens, Switzerland

Photography Catalogue of the Year

Claudia Andujar: a luta Yanomami

Claudia Andujar

Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo

Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983

Hannah Darabi

Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, and LE BAL, Paris

Who is Michael Jang?

Michael Jang

Atelier Éditions, Los Angeles

Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins

Larry J. Shaaf

Prestel Publishing, New York

What I Am Doing

Eiko Yamazawa

AKAAKA Art Publishing, Kyoto

PhotoBook of the Year

Vince Aletti

Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines

Phaidon, New York

Emi Anrakuji

Balloon Position

AKAAKA Art Publishing, Kyoto

George Georgiou

Americans Parade

BB Editions (self-published), Folkestone, United Kingdom

Sunil Gupta

Christopher Street, 1976

STANLEY/BARKER, London

Sohrab Hura

The Coast

Ugly Dog (self-published), New Delhi, India

Libuše Jarcovjáková

EVOKATIV

Untitled, Prague

Mari Katayama

Gift

United Vagabonds, Tokyo

Santu Mofokeng

Stories

Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Thomas Sauvin and Kensuke Koike

No More No Less

the(M) éditions, Paris; Skinnerboox, Jesi, Italy (NYABF booth X01); and Jiazazhi, Ningbo, China

Henk Wildschut

Rooted

Self-published, Amsterdam

Jurors’ Special Mention–Books About Books

The jury remarked on the extremely strong showing of books about photobooks and magazines—a now established genre in itself. Instead of selecting a single “book about books,” they chose to highlight the following eight books as excellent examples of this type of publishing.

Photobook Belge: 1954–Now

Tamara Berghmans, ed.

Hannibal Publishing, Belgium

Printed Photography in Venezuela

Sagrario Berti

Ricardo Báez, Sagrario Berti, and La Cueva Casa Editorial, Venezuela

Queer Publishing: A Family Tree

Bernhard Cella and Orlando Pescatore

Salon für Kunstbuch, Vienna

Czech and Slovak Photo Publications, 1918–1989

Manfred Heiting, ed.

Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

How We See: Photobooks by Women

Russet Lederman, Olga Yatskevich, and Michael Lang, eds.

10×10 Photobooks, New York

Camera Austria International: Laboratory for Photography and Theory

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany

Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler: Light and Shadow—Photographs 1920 to 1950

Hans-Michael Koetzle, ed.

Kehrer Verlag, Germany

Inner World: Modern Argentine Photography 1927–1962

Facundo de Zuviría

Fundación Malba, Buenos Aires

The post The 2019 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

A Chronicle of Midwestern Masculinity

Gregory Halpern’s newest photobook is a nuanced portrait of golden-hour Omaha.

By Brian Wallis

Gregory Halpern, detail from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Gregory Halpern exemplifies a new generation of documentary photography, less bound by the instrumental ends of activism and more determined to capture the conditions of American life through a lush, lyrical humanism that is simultaneously ominous and optimistic. In his newest volume of photographs, Omaha Sketchbook, published this month by MACK, Halpern offers an intuitive, nuanced portrait of the Midwestern city, mostly through shots of people and buildings captured elusively at dusk or bathed in honeyed golden-hour sunlight. Halpern’s purposeful meanderings through Omaha unspool as a rich meditation on the strangely threatening nature of American masculinity in all its expressions—or disfigurations. In fragile and unsettling images of male football players, prisoners, wrestlers, hunters, butchers, soldiers, and worshippers, Halpern seems to suggest that their hyperbolic posturing reflects the deep-seated anxiety around race and gender that fuels the country’s current political conflagrations.

Gregory Halpern, image from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Brian Wallis: Your earlier photographs and photobooks—such as A (2011), East of the Sun, West of the Moon (2014), or ZZYXZ (2016)—have often used a kind of lyrical documentary approach to examine different regions of American culture. Your new book, Omaha Sketchbook, chronicles a fifteen-year engagement with one Midwestern city. What drew you to Omaha, what made you return, and what did you learn over that time?

Gregory Halpern: I wound up there by chance. I had just finished graduate school, had applied for a handful of residencies, and was given one by the Bemis Center in Omaha. I knew very little about Omaha, but I was feeling a bit aimless at that point in my life, and I was thrilled to go there. I wound up staying in Omaha after the residency was over—I took a job teaching photography at a community college there. Altogether, I was there for about half a year. Somewhere along the way, I started to feel like I had something to say, and a somewhat clear voice/vision was emerging.

Wallis: I was struck by the fact that the work in Omaha Sketchbook spans an extraordinary political arc, from the post-9/11 presidency of George W. Bush through Obama to Trump. Do you feel that your photographs record a change in the attitudes of Midwestern Americans?

Halpern: The period of time is crucial. I moved to Omaha in 2005, early on in the Iraq War. In 2003, then-President George W. Bush gave Saddam Hussein a forty-eight-hour ultimatum to leave Iraq, or else the US would invade. There was a picture on the cover of the New York Times the next day, a still from W’s speech. What struck me was that the still captured something in W’s face that spoke to his supreme (if wounded) confidence, while also capturing something fearful. It exemplified that connection that’s visible often in men between inadequacy and aggression. And weirdly, it was also an encapsulation of how when portraiture (or art in general) accepts contradiction into its form, it becomes all the more compelling. All of that is to say that I moved to Omaha with the Iraq War and that portrait on my mind, and with W’s sense of cowboy masculinity darkening my understanding of America. I returned to Omaha sporadically over the years, but I didn’t pick the project up and aggressively try to finish it until my daughters were born and Trump was elected. So, I suppose working on the sketchbook was a way for me to work through some of this over the course of fifteen years in a relatively private way.

Wallis: How did you go about collecting these images? At times, they seem casual or random, but you must have had a plan at other times to gain access to certain locations or institutions. Does your process require extensive research and planning?

Halpern: It’s a mix of random or casual moments, along with occasionally elaborate planning and research. Phone calls to get access. Stopping someone on the street or meeting someone online and making an appointment to photograph them, for example. I don’t have rules to the methodology.

Gregory Halpern, image from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Your work recalls earlier photographic projects, from the road trips of Robert Frank and Stephen Shore to the reconfigured American landscape of the New Topographics photographers. At the same time, you allude to the loose narrative structure of the vernacular photo album, the casualness of certain independent films, and the happenstance observations of digital photography and Instagram. What visual models influenced your shaping of this project?

Halpern: I love all the work and genres you mention, but there aren’t honestly any specific “models” I could point to. I don’t think Instagram or digital photography influenced this work, though I started my sketchbook before those were part of my life. And I might add music to your list, because some of the pages, or the structure of the book itself, seem to be a visualization of certain musical forms for me.

Wallis: In your first book, Harvard Works Because We Do (2003), you used a very traditional social documentary approach—black-and-white photographs of workers, interviews and oral histories, statistical information—to support an activist campaign seeking higher wages for Harvard University service workers. That type of photography seems very different from the documentary approach you apply in Omaha Sketchbook. How would you characterize the differences in approach? And do you recall how you made that transition in your own work and why?

Halpern: The transition is because of my discomfort with the idea of speaking for, or on behalf of, the people pictured in Harvard Works Because We Do. I still believe in that project’s politics, but not in its artistic integrity. It’s useful as a tool of education or activism, but it’s too aggressively certain of itself to be a decent work of art. I no longer want to look at art that’s sure of itself and tells me how to think; I want work that respects the intelligence of its viewer, that’s driven by a sense of inquiry, curiosity, wonder, attraction, disgust, and an openness to contradiction.

Gregory Halpern, image from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Your approach in Omaha Sketchbook clearly relates to that of other contemporary photographers who use large-format color photography to document social conditions in the United States, but without direct reference to specific political issues or social conditions. Do you feel an affinity to or sense of collaboration with other photographers working in this vein? Do you see this as a new form of social documentary photography? And if so, what is the potential political impact on individual viewers?

Halpern: I don’t really see this as a new form of social documentary photography. I even hesitate whether or not the work is documentary. That term is a tough one for me. I’m not really sure what it means anymore. In a way, I think of everything I do as fiction, and yet I know that everything I do is also somehow rooted in reality or realism.

As for what the political impact of this work on viewers is, I really can’t say. I’m sort of cynical about the idea of photography having a profound political impact. Certain work breaks my heart. Judith Joy Ross, Milton Rogovin, Raymond Meeks, Mark Steinmetz. The work speaks to the fragility of life, the vulnerability of being human, and perhaps in that sense it’s political, or radical, in that it reminds us to be kind. But I’m skeptical of work that has an overtly political activist agenda. I sadly don’t think art is the best place to put your energy if you’re interested in social change. In a way, I’m wrong because, if you express yourself politically though art, you are presumably starting a conversation, and conversation is, in a way, the starting point for change. I’m just bothered by how isolated a bubble most of the art world exists within. Art is driven too often by capitalism, and exists too often within the circles of the uber-rich to have any teeth as a political tool. Photobooks and the internet are relatively free, but commercial galleries still drive so much of what happens within the art world, perhaps even more than museums, and to me, that’s a somewhat perverse kind of measuring stick for artists to be using on ourselves.

Wallis: One of the characteristics of a lot of this new documentary photography is a divorce of image from information, a deliberate ambiguity and a refusal of specific historical or political grounding. How do you account for this? And how do you think it relates to earlier forms of social documentary photography?

Halpern: I’m not sure, but I wonder if it’s part of a desire on photographers’ parts to distance themselves from that tradition, and from the idea of photojournalism. “Art photographers” often strive to be closer to painters, further from photojournalists. It’s funny, because there are so many great writers who move between the novel, poetry, essays, and journalism almost seamlessly, but maybe it’s harder sometimes, mentally, for photographers. But I think there’s the sense that some “social documentary” photography is naive, or pities its subjects, or creeps into didactic or sanctimonious territory. Not all, of course, and sometimes divorcing the images from the text or overt agenda would have done the work a service. I think perhaps audiences are just more visually literate now, because everyone is a photographer with their phones, and perhaps they need and want less direction from the photographer. The documentary aesthetic has profoundly compelling qualities, but in my mind, it’s strongest when a sense of realism is combined with a sense of wonder, or that exploratory, question-asking spirit of art-making, as opposed to a sense of lecturing or crusading.

Gregory Halpern, image from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Many of your pictures in Omaha Sketchbook are of people, often portraits of workers, occasionally incarcerated folks, and sometimes individuals in some degree of distress. Did you seek out certain types or professions? Do you feel an ethical responsibility to the individuals you photograph?

Halpern: I think my responsibility to my subject is to make the most interesting and complicated portrait of them possible. To simplify or to caricature them would be to insult them.

Wallis: Certain ominous themes or issues are quite apparent in your sequencing of Omaha Sketchbook—the challenges of masculine identity, the threat of poverty and underemployment, the destruction and desolation of the Midwestern urban landscape—and yet your book seems to me quite hopeful. Does this assessment seem accurate to you?

Halpern: I love that you felt those two things about the work simultaneously. It does seem accurate, and it’s a sense that I think drives me, and almost all my work. Those are all

things I feel simultaneously about the world, and in a way, that’s what reality is—chaos and contradictions. I think to edit the world visually only for signs of hope, or only for, say, omens, would be a distortion and uninteresting to make or to look at.

Brian Wallis is a writer and curator based in New York.

Omaha Sketchbook was published by MACK in September 2019.

The post A Chronicle of Midwestern Masculinity appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Landscape Photography Through the Female Gaze

An exhibition explores how women photographers are upending gendered views of the landscape—and reveling in the sublime.

By Katie Booth

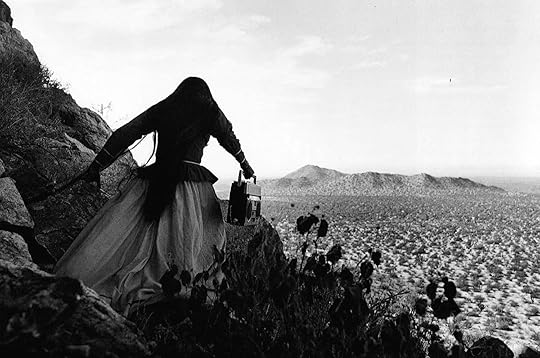

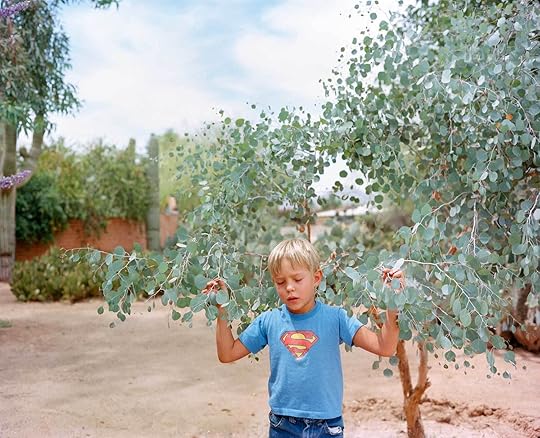

Graciela Iturbide, Mujer Àngel, Desierto de Sonora (Angel Woman, Sonoran Desert), 1979

© the artist and courtesy Throckmorton Fine Art, New York

In 1979, Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta traced her silhouette on a mound of earth, dug a volcano-like crater filled with live coals, and set the shape of herself on fire. Her visionary film Volcán and the corresponding photographs are evidence of her symbolic claiming of the earth, sexuality, and power.

Mendieta is among twelve artists included in the exhibition Live Dangerously, which opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, on September 19. Ranging from Xaviera Simmons’s portraits interrogating fiction and truth, to Justine Kurland’s lush chronicle of girlhood and adolescence, each of the works on display explores the female body in nature. Rather than historically passive portrayals of women in landscape, here, women are dynamic—running, setting off fireworks, climbing trees, and reveling in the sublime. The exhibition spans back to Louise Dahl-Wolfe’s work for Harper’s Bazaar in the 1940s and ’50s, when she insisted her models interact with the arid dunes of the California and Mojave deserts.

Ana Mendieta, Volcán, 1979

© The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC, and courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

Louise Dahl-Wolfe, California Desert, 1948

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Justine Kurland, Jungle Gym, 2001

© the artist and courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Live Dangerously aims to offer a fresh perspective not only on the American landscape, but on other global landscapes as well. “Historically, artists from diverse backgrounds and hybrid identities have frequently been the subjects of Eurocentric representations in landscape,” says curator Orin Zahra. “Here, they are the ones tackling their surroundings and shaping their own narratives.”

In her floor-to-ceiling installation 100 Little Deaths (2002), German-born artist Janaina Tschäpe inserts herself, horizontal and face down, into a variety of settings, exploring the interplay between the real and the imagined, darkness and humor. Meanwhile, Lebanese photographer Rania Matar’s portraits explore the interconnectedness between the landscape and personal and collective identities.

Rania Matar, Yara, Cairo, Egypt, from the series She, 2019

© the artist and courtesy Robert Klein Gallery

Laurie Simmons, Water Ballet (Vertical), 1981

© the artist

Also included in the exhibition is work by Anna Gaskell, Dana Hoey, Mwangi Hutter, Graciela Iturbide, Kirsten Justesen, and Laurie Simmons. “There is really no one ‘feminine’ style, as has often been argued in art historical discourse,” remarks Zahra. “Contemporary artists take the idea of nature as primitive or gendered, and expand it so the relationship between women and the environment can signify so much more.”

Katie Booth is the digital manager at Aperture Foundation.

Live Dangerously is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, September 19, 2019–January 20, 2020.

The post Landscape Photography Through the Female Gaze appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 18, 2019

Bad Cop

Heji Shin aims her penetrating gaze at newborn babies and gay policemen.

By Evan Moffitt

Heji Shin, Basic Precinct, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

The miracle of birth has never looked so gruesome as in Heji Shin’s Baby (2016), a series of portraits currently on display in the Whitney Biennial. The newborns’ oxygen-starved faces are bruised deep purple and dripping with blood. Their squashed, elongated crania—the result of soft skull tissue being squeezed by the cervix—resemble grapes fit to burst. Some have been captured between cries, as if stillborn, while others stare straight at us, mouths cracked open in anguish or relief, as they complete their violent escape from the womb. They may not remember this moment, but it’s eerie to think that the first thing these kids will have seen is the dull, unblinking eye of Shin’s camera.

“The procedure of birth is very similar to death,” Shin said in a brief audio didactic recorded by the Whitney. “It is excluded from social life, from public life—because it’s violent, it includes a lot of aggression.” Shin connected with midwives and expectant mothers, who invited her to shoot on delivery day. Shin considers herself a classical portraitist, and all of these babies are centered in the frame, their mothers’ thighs and labia cradling them like starched collars, pale against the muddy slick of blood and amniotic fluid.

Heji Shin, Baby 5, 2016

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

The works are a far cry from Carmen Winant’s My Birth (2018), the star work in last year’s Being: New Photography 2018 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. There, two thousand archival photographs of women giving birth spanned a long corridor wall, where Winant pasted them with blue painter’s tape. The fine-grained detail of Shin’s photographs was absent: instead, mothers themselves were foregrounded, in tender scenes of intimacy and elation. By contrast, we can’t see the mothers’ faces in Shin’s work; our attention has been focused on the slightly warped, seemingly alien bodies they’re ejecting from between their legs.

In her latest book, Motherhood (2019), Sheila Heti spends 304 pages reconciling with her desire not to have children—what she ultimately considers “a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.” Shin’s photographs have no room for such sentimentality. She loves to trash the stereotypes we use to simplify our many cultural contradictions. The more removed from her own experience these subjects are, the better she seems to maintain a critical distance in depicting them. In a presentation at the February 2019 Engadin Art Talks, Shin explained her decision to shoot a gay pornographic film in Reena Spaulings Fine Art for her 2018 show there: “For two months I tried to become a gay man as much as possible.” A statement like that might raise the specter of Rachel Dolezal, the woman who claimed to be “transracial,” but the photographs that emerged are a beautiful, highly explicit indictment of fascism and misogyny in the gay community.

Heji Shin, We Live in a Society, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

Through a Craigslist ad, Shin found two male models and posed them in the starched navy uniforms of the NYPD. Embodiments of “New York’s Finest,” these hot cops recline on a casting couch in nothing but their caps and gun holsters, and fornicate on a table lit by the glare of a policeman’s flashlight held just outside the frame. In remarkable close-crops, including one cyanotype, their anal penetration resembles birth: a cheeky nod to gay barebacking culture and its vulgar references to “breeding.”

With PrEP use increasingly widespread in the gay community, and the historic precedent of Robert Mapplethorpe’s S&M photographs now forty years past, it’s not the barebacking that offends in these images, but the uniforms. The NYPD is infamous for its brutality, from the death of Eric Garner to the “broken windows” policing that has torn apart communities of color across the city since the 1980s. (On the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, a splinter queer march was held parallel to the city’s official pride parade; its organizers noted the perversity of allowing cops to march in the main celebration of an uprising against police violence.) This perversity is what directs Shin to her subjects—what she shoots must be difficult; good art is anything but easy—and indeed, these bootblacks are irresistible.

Heji Shin, Book ’em, Danny 2, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

“Bad cop” is a familiar role-play fetish, handcuffs a common bedside prop. Shin based at least one of her photographs directly on a drawing by Tom of Finland, who worshipped uniformed men and cruised Nazi soldiers in the parks of Helsinki during World War II. While associations to power, especially military force, have become less salient in queer circles lately, Tom still enjoys his spot in the gay pantheon uncontested. In two of the photographs, one of Shin’s boys in blue is reading Arthur Schopenhauer’s On Women (1851): a misogynistic screed whose racist authoritarian author, obsessed with ancient India and its Vedic culture of spiritual self-conquest, influenced the Aryan nationalism that gave rise to Hitler. Shin’s police porn also owes a debt to Collier Schorr’s many photographs of young men dressed as Nazis, which Schorr took in Southern Germany in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As Theodor Adorno observed in Minima Moralia (1951), “Totalitarianism and homosexuality belong together.”

Heji Shin, KW5, 2018

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

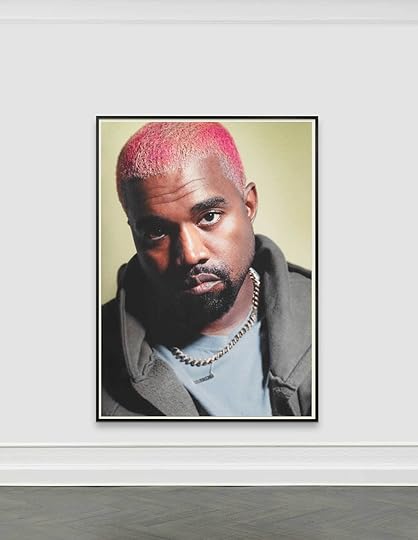

The theme of penetration, well, penetrates Shin’s work: from a child’s rupturing of her mother’s birth canal to the probes of an X-ray. Shin’s photographs pry deep into our individual and cultural subconscious, stripping bare contradictory layers that, once exposed, can’t be unseen. In 2018, Shin chose her toughest—and, incidentally, most notorious—subject for her show at Kunsthalle Zürich, which presented earlier this year. Billboard-sized prints of Kanye West filled the galleries of the Swiss museum. The resulting photographs—two of which adjoin the Whitney cloakroom as part of the Biennial—are a study in celebrity cool. Their hypersaturated yellows and reds seem fit for a punchy album cover. Accompanying the portraits were X-rays Shin had taken of herself, holding small dogs. “I thought I could suggest to the viewer that, when you see these very huge Kanyes that show only surface, and are very impenetrable, then you see my self-portrait, with complete transparency,” she said at Engadin. “It raises the question that, if you see much more, you may see even less.”

Evan Moffitt is associate editor of frieze.

The post Bad Cop appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 12, 2019

Michael Jang’s American Dream

The photographer revisits his deeply funny and idiosyncratic images of suburbs, celebrities, and California in the 1970s.

By Will Matsuda

Michael Jang, Lucy Watering at Night, 1973

© the artist

Michael Jang has kept much of his work hidden in a box at his home in San Francisco for the last forty years. Luckily for us, he decided to drop a selection of photographs off at SFMOMA for consideration in 2002. His early photographs from the 1970s, especially the ones of his very suburban, extended Chinese American family, made an impression on the curators at the time. Deeply funny and idiosyncratic, Jang’s images feel relevant to many of the national conversations happening right now about immigration, assimilation, and the elusive American dream.

Ahead of the publication of his first monograph and a major retrospective exhibition opening at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts in San Francisco in September, I spoke with Jang about photographing his family, the restrictions of intentionality in photography, and what it takes to sneak into Hollywood parties.

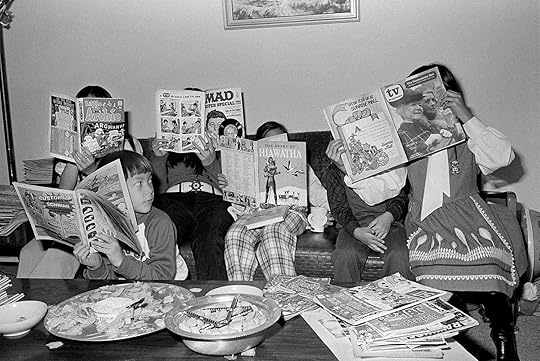

Michael Jang, Living Room Scene, 1973

© the artist

Will Matsuda: I want to start with your series The Jangs, which you made in the summer of 1973. Why did you make those pictures then, and how do you feel about them now?

Michael Jang: Old pictures often just look like old pictures. So what is it that makes these photos interesting still? The vintage rugs? I honestly don’t know. Erik Kessels, in the intro to my book, Who Is Michael Jang?, talks about the humor in the work, and how that’s somewhat of a rarity in the fine-art photography world. Humor wasn’t totally intentional in these photos.

I felt out of place in art school because in critiques, you are supposed to put up your work and talk about your intentions. I was uncomfortable with that. Someone thirty years later told me, “Michael, you’re just a responder.” That’s what I do, I respond. Let’s suppose you have an idea for a photo, and then you go out and make it. Then the photo is only as good as the idea. It’s missing magic.

Michael Jang, Study Hall, 1973

© the artist

Matsuda: That’s interesting for me to hear, because I work in the complete opposite way. I spend a long time thinking about my intentions with a photograph, and then I set out and it either meets those intentions or it doesn’t. That’s what makes a photo successful for me. But it is agonizing sometimes.

Jang: That’s the limitation. In movies, too, if a filmmaker captures an unscripted scene, there’s the magic. Same with music and improvisation, like in jazz. That’s what I’m looking for.

Michael Jang, Onlookers at the George Moscone funeral, 1978

© the artist

Matsuda: Can’t a preplanned photo, or one with a clear intention behind it, have magic too? It doesn’t matter how much you plan, a photograph never happens perfectly. It doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

Jang: I’ll meet you halfway on this one. Yes, you’re right, it’s good to have an outline of a plan. But it’s also about having an open mind to allow yourself to see what is actually there. Seeing can be done with the heart as well as the eyes.

I respond to pools of energy. It’s sort of a parallel way to look at the world. You shoot without looking through the camera. Robert Frank shot from the hip in that photo of the cowboys (Bar, Gallup, New Mexico, 1955) in The Americans. That’s feeling something. You’re feeling energy. There’s juice in the picture.

Michael Jang, Aunts and Uncles, 1973

© the artist

Matsuda: I think the reason your photographs are successful and timely is that there are serious implications in them, even if you didn’t intend it.

Jang: Well, I didn’t think these pictures were very good when I took them in the ’70s. I put them away in boxes. A few decades later, I dropped them off at SFMOMA and they liked them. Over the last ten years, I’ve brought them out in little pieces in zines or do-it-yourself pop-up exhibitions. So I’ve been testing the water in San Francisco, but it’s kind of like if your mom likes your pictures. It’s not really a test; this book and exhibition are a real test. I have no idea what people are going to think. I will be just as surprised as anybody if someone has a special interest in them. It feels kind of like a miracle that the pictures aren’t still in boxes.

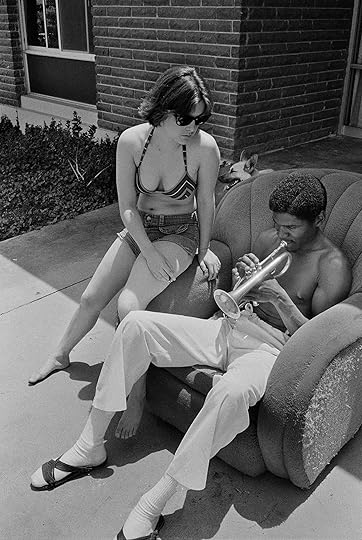

Michael Jang, Kylo Kylo playing trumpet with Sami Campbell watching outside the CalArts Dorm, 1973

© the artist

Matsuda: If you didn’t think they were very good and you had them boxed up, what made you bring them to SFMOMA?

Jang: When you’re young, you are very sensitive to critiques. Your work gets torn apart. It doesn’t take much to think, “These pictures probably have no future.” I wanted to move on and try to make a living off of photography. I never was in the game either. You’re supposed to get your MFA, then become a teacher, then get a National Endowment for the Arts or Guggenheim grant, and make some coffee-table books. In a way, my career is happening in reverse. Here I am in my late sixties and just now gaining some notice. It’s a gift. A lot of people my age are done and forgotten about.

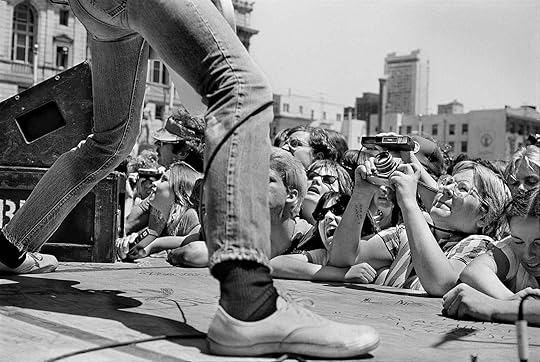

Michael Jang, Ramones Free Concert, Civic Center Plaza, 1979

© the artist

Matsuda: The reason these photos are meaningful in this moment, to me at least, is that you are directly questioning the exclusivity of who gets to be American and who can live out the American dream. There’s a sort of jaded irreverence in the photos, and I think therein lies their power.

Jang: People have said we look like the Chinese Brady Bunch.

Matsuda: Right, and when you talk about these photos not being serious, I disagree. I think they are totally serious.

Jang: You’re right. Sometimes artists deflect questions, because they don’t want people to get too close. But please understand, when I made them I wasn’t serious. It was pure fun. It is only now that they are being looked at critically. Others have deemed them “serious,” not me.

One gallerist was looking at the photos, and told me, “You have David Carradine on the TV in a photo, who was a white guy playing a Chinese guy in the show Kung Fu. I mean c’mon. You knew what you were doing.” I had to laugh. Subconsciously, yes, but at the time it was done without thinking. And also done without planning to show it to anyone. But I think when you put pressure on yourself to have a statement about your family, it could become a problem. It might be a little boring even.

Michael Jang, Self-Portrait, Financial District, San Francisco, 1973

© the artist

Matsuda: I also want to talk about your self-portraits, which are peppered throughout the book. These were some of my favorite pictures. We get an idea of the type of person you are from the type of photographs you take, but it really comes across in the self-portraits. The slyness, the smirk. Are you still making self-portraits? What do you think about them now?

Jang: I’d like to plead the fifth, but also bad memory. It’s been forty years!

Well, actually, one of the self-portraits is on the cover, and there are six people spread across the frame. That’s hard to do when you are composing the shot by looking through the camera. But I was just hand-holding it and hoping for the best. That’s the game of it, as well as the beauty.

In school, I wasn’t really interested in academics talking to me about what a photograph should do. Lee Friedlander said to go out and shoot, to have fun, and that it is just a game. That resonated with me.

I still have my notes from Friedlander’s class at CalArts in 1973. One of them says, “My pictures have no use for anything except my own pleasure. It’s not their function whether you like them or not. If I exhibit, that’s someone else’s problem. They ask me.”

Michael Jang, David Bowie Signing Autographs, 1973

© the artist

Matsuda: While you were at CalArts, you were fabricating press passes to get into parties with the Hollywood elite. You must have some wild stories from that time.

Jang: I checked out a Leica from school and took it into town, and I saw Bowie at the Beverly Hilton. I found out that every Saturday night, there was a major Hollywood party or event, so I kept going back.

The events are all the same. The stars arrive, the paparazzi are there waiting outside, they pose for a picture, and then they go in. I thought, hold on, that’s where the pictures are. So I had to get inside. I did that any way I could. I dressed up in a suit and snuck in through the back door, but I usually got kicked out.

The series was about the adrenaline rush of sneaking in just as much as it was an essay on parties in Hollywood. I know that now these pictures are impossible. If Jay-Z was at the Beverly Hilton in 2019, would you be able to sneak in?

Matsuda: Probably not . . .

Jang: But could I sneak in? Maybe.

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer based in Portland, Oregon.

Michael Jang’s California is on view at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts, San Francisco, from September 27, 2019–January 18, 2020.

The post Michael Jang’s American Dream appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

September 5, 2019

Graciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions

The life and work of Latin America’s most revered photographer.

By Ramón Reverté

Graciela Iturbide, Self-Portrait at My House, 1974

Courtesy the artist

For more than fifty years, Graciela Iturbide, recognized today as the greatest living photographer in Latin America, has envisioned the diversity of life in her native Mexico. Her lyrical, black-and-white images of street scenes in Mexico City, of Seri women in the Sonoran Desert, of political rallies in Juchitán, and of details inside Frida Kahlo’s bathroom are revered throughout the world. At the age of twenty-seven, aspiring to be a filmmaker, she enrolled in a university class with the maestro of modern Mexican photography, Manuel Álvarez Bravo. The experience was formative. “More than being my teacher of photography,” she recalls, “Don Manuel taught me about life.”

Earlier this year, the editor and publisher Ramón Reverté visited Iturbide at her home in the Mexico City neighborhood of Coyoacán. One wall of her living room is lined with soaring shelves full of beloved photography books. In her studio located across the street—built by her son Mauricio Rocha, a noted architect—she keeps altars of objects and books that belonged to Álvarez Bravo and Josef Koudelka. At the time of Reverté’s visit, Iturbide had recently opened two major solo exhibitions, one at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and another at the , in Mexico City’s historic center, which drew hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Here, Iturbide speaks intimately about her beginnings, her passion for photography and books, her long-standing interest in Mexico’s Indigenous cultures, and her favorite photographers, including Álvarez Bravo, who has been, as she says, “her guru.” On one occasion, Iturbide told Álvarez Bravo that she was traveling to Paris to visit museums. “But why,” he replied, “if you can see it all in books!” Iturbide, a relentless reader, took his advice, but only partly: she has never stopped traveling.

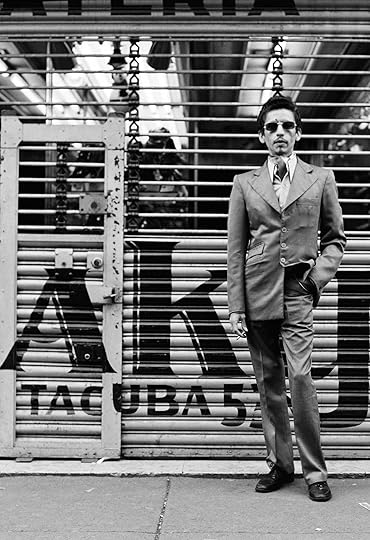

Graciela Iturbide, Aky, Mexico City, 1972

Courtesy the artist

Ramón Reverté: I’d like to ask about the beginning of your career—I’m sure you’ve probably gotten the same question a thousand times—how did you come to photography? And I’m curious whether from an early age you enjoyed painting and photography, or is it an interest that was ignited as a result of your meeting Manuel Álvarez Bravo?

Graciela Iturbide: In my family, there wasn’t an affinity for any of those things. I wanted to be a writer from a young age. My father, who was very conservative, wouldn’t let me attend university because women were supposed to stay at home. I married very young. I quickly had three children. I wanted to study philosophy and literature, but I couldn’t because, with three children, I had no time.

At an early age, I had a camera, and I took photographs because my father was an amateur photographer. I loved to go into his closet and steal his photographs, which led to various punishments, but my father should have been proud I was stealing his photographs.

In 1969, when I was already married and twenty-seven years old, I heard on the radio that there was a university where you could study film, and I enrolled. It was very easy to get admitted; everyone got in because it was when the film school was just getting started. That’s where I met Manuel Álvarez Bravo, who was giving photography classes. I had the book he had published during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico and brought it to him so he could sign it. I asked if I could take his classes, and he said yes. No one went to his classes because everyone wanted to be film directors. After two days, he said, “Listen, I’d like you to be my achichincle,” and I said, “Of course.” An achichincle in Mexico is the person who assists the construction worker and does a bit of everything.

That’s how my life changed. We spoke a lot about painting. We listened to a lot of music. It was my salvation in life because he had a very different way of thinking than my family. On one occasion, he told me, “You know what, Graciela, divorces help because one can start anew.” It was like he was opening me to life. Within a year, I was divorced, without any struggle, without any issue.

Reverté: Tell me about your parents. Did you go to exhibitions when you were little?

Iturbide: Not so much to exhibitions, but we went to concerts, to the opera, to musical things. Sometimes my father would take us to the Cervantino Festival. I was very young then and was somewhat interested in cultural things. My parents’ parents had haciendas. With the revolution, and then under President Lázaro Cárdenas, they lost everything. My father had to work from a young age to support his family. At the age of sixteen, he started working in Oaxaca with the archaeologist Alfonso Caso, strangely enough, as his assistant. He never had a formal profession. My mother played piano recitals when she was young, and she loved classical music. She also drew. She was more sensitive to those kinds of things. But I wouldn’t say it was a cultured family. It was a bourgeois family.

Graciela Iturbide, Carro (Car), 1972

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: When you decided to study film, was it because you liked film, or because you saw some kind of escape? Was it a conscious decision?

Iturbide: Yes, because I wanted to. I told myself, In film, there is a script, and I want to study literature, so I might as well study film and see what I can do from there. I did it out of my need to study something because I had never been allowed to. It was an urgent need within myself.

Reverté: So photography wasn’t an interest of yours at that time?

Iturbide: I took photographs as a child because my father gave me a camera when I was eleven years old. But I took photographs of things like churches, from the bottom up, stranger things than my cousins and siblings photographed. I always saw my father taking photographs, and he did a bit of film, but just as a hobby.

Reverté: So it’s really Don Manuel who introduced you to the world of photography?

Iturbide: More than being my teacher of photography, Don Manuel taught me about life. I was already developing my own film because I had taken some photography classes before taking lessons with Manuel. So one time I asked him, “Maestro, how do you properly develop a roll of black-and-white film?” And he responded, “You know, Graciela, go to the photography store, buy yourself a roll of film, read the instructions, and that’s how you do it.” He never told me whether my photographs were good or bad. Never. But he spoke to me a lot about painting. He spoke to me about literature. We listened to opera in the afternoons.

He made me see life in a different way than I had lived it as a child. When I lived with the father of my children, who was a more liberal man than others I had known, it also helped a bit in my development. In my time, it was unlikely for husbands to say, “Yes, yes, of course, go study.” It wasn’t very easy.

Graciela Iturbide, Mexico City, 1969

Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Reverté: How long were you working with Don Manuel?

Iturbide: I worked with Don Manuel for about two years. But I stayed near him all my life, that’s why I live here. When I separated from my partner, I came to live here [the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City] because Álvarez Bravo told me, “They’re selling a little plot of land over there, Graciela. Come here to Coyoacán.”

Reverté: Photography wasn’t an easy path to making a living.

Iturbide: I’ve had money, I’ve had no money, but when I didn’t have money, there were rolls of film in my refrigerator. I’ve always been taking pictures. At the very beginning, and when I got divorced, the only work I had was for hire for magazines like Mundo médico (Medical world) and Médico moderno (Modern doctor) to go photograph operations.

Reverté: And what did you photograph?

Iturbide: Births. Once I won an award for a cover that I shot. They paid me monthly. I didn’t have to be there the whole time, only when they commissioned things. It’s the only work I’ve ever had for hire, and I loved it.

Reverté: What was your first contact with the photography world? Was it at the INI [National Institute of Indigenous Peoples] that you first began?

Iturbide: I only did a project with the ethnographic archive at the INI. They made various films and published seven books about this archive under the direction of Pablo Ortíz Monasterio. It was my job to go to the desert with the Seri, and I was fascinated.

Graciela Iturbide, Carnaval (Carnival), Tlaxcala, 1974

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: The first exhibition you had was in Mexico, and then it traveled to New York.

Iturbide: My first exhibition was at the Orozco Gallery with Paulina Lavista and Colette Álvarez Urbajtel. And then it traveled to New York, with a photographer named Larry Siegel, who had been my teacher here in Mexico before I went to study with Álvarez Bravo. He was the director of the gallery in New York.

Reverté: So that exhibition had nothing to do with Don Manuel?

Iturbide: Yes, that exhibition came about thanks to Manuel because Larry spoke with him and Manuel decided that it should be three women: Paulina Lavista, Colette, and me. After that, I started to have solo exhibitions.

Reverté: How did you manage to maintain a family at such a complicated time, in addition to being a woman on your own, in that era in Mexico, with three children?

Iturbide: At the beginning, I had the help of my husband, then I worked for Médico moderno, and then I worked taking photographs of people who asked me to take photographs.

Reverté: Portraits?

Iturbide: Lots of portraits, even weddings. I managed. I made money, but I never stopped taking my own photographs. I loved going to the country to be with Álvarez Bravo.

Reverté: You continually saw Manuel Álvarez Bravo?

Iturbide: Always. Until the end. I always went to see him to speak with him, to listen to music. The thing is that I didn’t want to be his assistant anymore because I didn’t want him to influence me. I had to cut the umbilical cord.

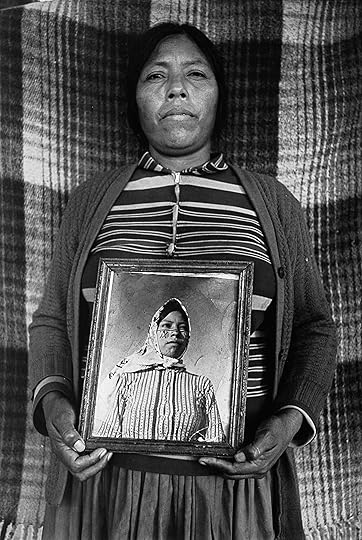

Graciela Iturbide, Seri Woman with Her Portrait, Sonoran Desert, 1979

Courtesy the artist

Reverté: Even though Don Manuel’s influence is present in your work, in the most positive sense, you had a personality all your own in your photography from the very beginning. What is it that truly moves you to take photographs? If you go somewhere now, what motivates you? What is it you want to photograph immediately?

Iturbide: It’s never clear to me what I want to photograph. I always go out walking, even when I’m asked to go photograph something in particular. Surprise is what gets me to pull the trigger on the camera. If I say, “Ay! What a wonder!”—then I press the trigger.

Reverté: Do you take lots of photographs?

Iturbide: A normal amount. I’m not like the people who came from Magnum. When I took them to Manuel’s house, they saw a dog on the rooftop and started to take a ton of photographs. Manuel always said to me, “Chaca chaca chaca chaca, why so much junk, Graciela? For what?” I learned a different way of taking photographs from Álvarez Bravo, because he always took one or two shots. If, by chance, he took two, it was already too many. In my case, if I come across something and I like it, I could even take three or four photographs, but I’m not a compulsive photographer. Sometimes I’d take more than one shot in case the negative gets scratched. I always took photographs calmly and enthusiastically and with surprise.

Reverté: If I were to go with you to photograph for two days in Oaxaca, what would the process be like?

Iturbide: I went to these villages with my camera so that people would know that I was a photographer, and I lived with them, which created solidarity. If I go to a festival where photography is allowed, then I take photographs because it’s allowed. If I see that it isn’t allowed, that people don’t want me to take photographs, I don’t. I don’t have a telephoto lens, nor a tripod, nor flash. It’s how I’ve always worked, with a handheld camera but always with people’s complicity. Sometimes, people ask me to take their photographs, like with Magnolia [the iconic photograph from the 1979–89 series Juchitán de las Mujeres]. I was at a cantina, and she was there, and she saw me with my camera and said, “Ay, ay, my love, take my photo.” I went upstairs with him, or with her, to the room, he got dressed, he made himself up, and I went on taking photographs as he wished, exactly as he wished.

Reverté: It’s obvious that you share empathy with people.

Iturbide: Yes, it’s beautiful when people ask you to take their photograph. When I go to Juchitán or when I am with the Seri, for me they are not “the other” because they also come to visit me at my house, the same with the Mayo [the people of Sinaloa] as with the Juchiteco. These are people of my country, just like me.

And yes, I have a capacity to feel empathy. I try not to hurt people. That’s why I just have a normal lens that allows me to come close to people, and somehow they accept me even if I don’t ask permission. In some way, with the camera, I am asking. There is an implicit permission.

To continue reading, buy Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Graciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Agenda: 4 Photography Exhibitions to See in Fall 2019

From Duane Michals’s first New York retrospective to the swinging nightlife of London’s Soho, here are this fall’s must-see exhibitions.

Alinka Echeverría, Fieldnotes for Nicephora, from the series Nicephora, 2015–ongoing

© the artist

Alinka Echeverría

During a 2015 research residency at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce—a French museum devoted to Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce, who is often credited as the inventor of photography—Mexican British artist Alinka Echeverría employed an intersectional feminist lens to recontextualize the museum’s colonial archives. With a background in social anthropology, she studies historical representations of women in photography, using collage to liberate and reframe these images. Echeverría’s upcoming show at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Simulacres, revisits her work on Niépce to pose critical conversations between archival images of women and vases from the museum’s collection. “Alinka’s work not only addresses questions of the feminine but also the question of the ‘other’ as objects of colonial study,” says María Wills Londoño, curator of the exhibition. “She works in collages—tearing images, taking objects, and making fragmentations—to question the semiotics of the feminine and how society and history are constructed.”

Simulacres: Alinka Echevarría at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, September 5–December 1, 2019

Duane Michals, Warren Beatty, 1966

© the artist and courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals

Duane Michals never really studied photography. When he started experimenting with pictures in the 1960s, he felt free to live and make work any way he wanted. He began to explore cinematic devices and multiple exposures, staging multipart photographic sequences that consider mortality and desire. He embraced technical errors. And he wrote in the margins of his prints. “Writing allowed Michals to find his voice in photography,” says Joel Smith, curator of photography at the Morgan Library & Museum, which is presenting Illusions of the Photographer, Michals’s first full-scale New York museum retrospective. Covering five decades of Michals’s photography and short films, the exhibition will be accompanied by an artist’s-choice show, selected by Michals from the Morgan’s collection, featuring works by Eugène Atget, Auguste Rodin, and Joseph Cornell. “Illusions,” Smith says of Michals’s work, “allow a photographer to believe in the vision of the world he’s got and make it real.”

Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, October 25, 2019–February 2, 2020

Jan Groover, Untitled, ca. 1978

© Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne/Jan Groover Archive

Jan Groover

“Formalism is everything for Jan Groover. It is a motto, true from the first work to the last work,” says Tatyana Franck, director of the Musée de l’Elysée. Groover is best known for her kitchen still lifes from the 1970s and ’80s, a body of work that became a postmodern classic and helped make the case for color photography as art. Two years after Groover’s death in 2012, Franck visited the house in rural France that the artist had shared with her husband and was astonished to discover forty years of Groover’s work there. In 2017, the museum acquired the archive, which contains some twenty thousand objects: sketches, Polaroids, negatives, contact sheets, test prints, technical equipment, and Groover’s own photography collection. Laboratory of Forms, curated by Franck, is Groover’s first survey in over thirty years and includes portraits, still lifes, and landscapes from 1967 to the very last negative Groover printed.

Laboratory of Forms: Photographs by Jan Groover at the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland, September 18, 2019–January 5, 2020

Anders Petersen, London 150, 2012

© the artist

Shot in Soho

P. D. James once said that London’s Soho district was a “cosmopolitan village” with good food, great shopping, and sordid crime. Before its more recent polished incarnation with boutique hotels and a new Crossrail transit line, Soho was a magnet for disobedience and debauchery, yet it still remains a destination for artists of all types. Shot in Soho presents images by photographers such as Anders Petersen, William Klein, and Corinne Day, who profiled the infamous neighborhood. Not simply an exercise in nostalgia, the exhibition also looks at present-day Soho through images of romantic connections in a new commission by the emerging Irish photographer Daragh Soden. Together, Shot in Soho celebrates an ever-changing, one-square-mile enclave that contains, as James noted, “all things to all men, catering comprehensively for those needs which money can buy.”

Shot in Soho at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, October 18, 2019–February 9, 2020

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Agenda: 4 Photography Exhibitions to See in Fall 2019 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 29, 2019

The Publisher at the Forefront of Photographic Literature

Image Text Ithaca is leading the way in experimental and hybrid image-text photobooks.

By Olga Yatskevich

Jo Ann Walters, Holly Springs, Mississippi, 1988, from Wood River Blue Pool (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2018)

© the artist, courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

The Image Text Ithaca (ITI) Press at Ithaca College is a publisher with a unique vision that brings together, in an innovative and experimental form, writing and photography. It was founded in 2015 in Ithaca, New York (as the name suggests), by Nicholas Muellner and Catherine Taylor, both of whom feel that literary and photographic visual worlds run parallel in certain ways but rarely speak to each other well. Muellner and Taylor have different backgrounds, areas of expertise, communities, and insights, yet their roots are shared and their differences turn into strengths. Taylor is at the forefront of experimental literature, the world she has been immersed in for a long time, and the same is true in regard to Muellner’s involvement with photography. As they work on publications, they equally participate in both aspects of the books while respecting each other’s larger field of knowledge. The press is an integral part of a broader Image Text Ithaca initiative at Ithaca College, which includes an MFA program, workshops, and symposia.

Jodie Herbage, Untitled, 2015, from Tessex? (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2015)

© the artist and courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

Nicholas Muellner has been experimenting with text and images for over a decade now, finding innovative ways to initiate conversation between these two artistic fields. He has authored five of his own photobooks, and each of them offers a thoughtful body of work where visual and textual narratives overlap, creating exciting layers and dialogue. Muellner’s latest book, In Most Tides an Island (SPBH Editions, 2017), is a clever example of photographic literature, bringing together an interlocking set of short stories and images. He also eagerly plays with form, as in the Self Publish, Be Happy Pamphlet series he curated and edited. Each pamphlet, designed by Antonio de Luca and published by Bruno Ceschel, combines a commissioned photographic work with a short original text. For one of them, photographer Jason Fulford and writer Chris Mills separately visited the apartment of a photobook collector. Their photographs and text on the visit, published on a single sheet, provide an example of a simple yet effective platform for a conversation between the two forms. Muellner also organizes performance-like book launches that mix readings with visual slideshows, expanding viewers’ experience of image and text-based work.

Words are Taylor’s territory. She is a writer and editor working in a wide range of nonfiction forms, including journalism, lyrical essays, poetics, and other hybrid-genre writing. At the beginning of her career, Taylor worked as a producer and writer on a number of documentary film projects in New York City. She completed a PhD at Duke University, and her time there had a profound influence on her work; her book Apart (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012) mixes archives, history, family memoirs, and personal reflections in a complex discussion of the political history of South Africa (where she and her family are from). In 2017 she released her third book, You, Me, and the Violence (Ohio State University Press), a memoir and analytical essay on “drones, power, and feelings of powerlessness.”

Bobby Scheidemann, Untitled, 2015, from Tessex? (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2015)

© the artist, courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

When Muellner and Taylor were introduced, both were teaching at Ithaca College; they immediately discovered a mutual interest in each other’s work. Initially they planned to work together on a book, but their collaboration ended up going way beyond that: in 2014 they started an experimental workshop, held in a restored barn in Ithaca, as they decided more conversation was needed around the intersection of photography and writing. They brought together an inspiring group of both established and emerging photographers, publishers, writers, editors, and artists. It was a unique opportunity for these groups to engage in a meaningful dialogue, as the two fields rarely intersect, especially in the academic world. It was a collaborative exercise and participants were each asked to come up with an idea for a publication; the workshop thus served as the first step in the foundation of the Image Text Ithaca initiative.

ITI Press was officially launched during the 2015 LA Art Book Fair with the release of a limited-edition poster, an adaptation of the 2014 video poem Zidane produced by poet Claudia Rankine and filmmaker John Lucas. The poster’s concept, which was also conceived during the workshop, set the relationship between text and image to boldly reflect Rankine’s poetic pace in the video.

Andre Bradley, Untitled, 2015, from Dark Archives (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2015)

© the artist, courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

Now in its fourth year, ITI Press has published ten titles to date, ranging from monographs and posters to pocket-size series of image-text collaborations, collective titles, and a thesis sampler. ITI Press works with Elana Schlenker, whose vision and sensitivity help successfully unite writings and photography in the book format. In 2015, ITI published Dark Archives by Andre Bradley, a book that brings together the personal and the private as Bradley revisits childhood memories through writings, photographs, and the family photo archive. Another title, Tessex? (by Emma Kemp and Daniel Wroe, Bobby Scheidemann, Analicia Sotelo, and Thomas Whittle), was the first collaborative publication that evolved from the 2014 workshop, described as “equal parts manifesto, fiction and travelogue, wrapped in a glossy tabloid package.” Grind (2016) is an art-text collaboration between Muellner and poet John Keene, which takes as its foundation found text and images from the queer online dating scene. Muellner and Taylor mindfully consider the people and projects ITI Press takes on. Their recent publication Wood River Blue Pool (2018) brought together photographer Jo Ann Walters; Laura Wexler, a cultural historian; and Emma Kemp, a young experimental nonfiction writer. Walters’s photographs, taken between the late 1980s and 2016, pay nuanced attention to the overlooked lives of women and children in small, working-class towns; the text by Wexler provides a contemporary take on the historical and social context of the photographs. For this project Kemp was sent on a writing assignment to Alton, Illinois, Walters’s hometown. She was given complete freedom, and her text, which integrates art criticism with a murder mystery, couldn’t be more exciting. It has been published in a companion volume Blue Pool Cecilia; the two books complement each other while functioning as individual publications, a type of collaboration that brings together diverse voices and invites multiple audiences into conversation.

Another ITI book released in 2018 is My Birth by Carmen Winant, copublished with Self Publish, Be Happy. Winant’s work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s Being: New Photography 2018 exhibit, as an archive of images installed on two facing walls with strips of ripped blue painter’s tape. While the floor-to-ceiling installation created a visually striking experience, the book treats the material quite differently, deliberately intertwining images and texts in a format that allows for a more intimate and engaged experience. Taylor, who herself has published a book on a related subject, Giving Birth: A Journey into the World of Mothers and Midwives (2002), was excited to work closely with Winant on the text. Winant’s spare but impactful writing sets a powerful and engaging tone for the photobook narrative: it opens with a number of direct questions, instantly grabbing our attention and then pushing us into the visual sequence. The text is also used to break up the intense visual narrative, bringing in a pause and a continuation of the verbal conversation about the experience of giving birth.

Carmen Winant, Untitled, 2018, from My Birth (Image Text Ithaca Press and SPBH Editions, 2018)

© the artist, courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

From the very beginning, collaboration has been vital to the ITI philosophy, which was essentially born out of a collaborative experience. Taylor and Muellner always envisioned their publishing enterprise being closely connected to the Image Text Ithaca MFA Program, which was established in 2016 as an exploratory and innovative program focusing on the cross-disciplinary and experimental integration of creative writing and photography. While the program takes advantage of the academic environment, it is not constrained by academic models, creating a unique learning space. Every year Taylor and Muellner invite additional faculty members, artists whose practice complements the ITI vision, among them Lucas Blalock, Bruno Ceschel, Justine Kurland, Tisa Bryant, Melissa Catanese, and Ed Panar. While students don’t necessarily have to work in both fields all the time, they learn how to operate with and share a common language. The MFA program works closely with ITI Press, allowing students to get involved in and learn certain stages of the publishing process. The first class graduated in the summer of 2018, and as a part of their graduation project, students jointly released a publication including eight booklets, housed inside a fabric-wrapped case, showcasing the work of each student.

ITI Press sees its mission as opening up the audience across visual and literary spaces, creating new vibrations and expressive possibilities across reading and seeing. As they work on publications, Muellner and Taylor keep asking: “How do you ensure language is not an afterthought to image, and image is not an afterthought to language? How do you make them interdependent and stronger than the sum of their parts?” This is the challenge. Considering that three of their monographs were shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards (by Andre Bradley, Jo Ann Walters and Emma Kemp, and Carmen Winant), and that Bradley’s book was also shortlisted for the 2016 Photo-Text Book Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles, ITI appears to be meeting that challenge, by bringing publications to the photobook community that are urgent and new.

Jo Ann Walters, Brandford, Connecticut, 2001, from Wood River Blue Pool (Image Text Ithaca Press, 2018)

© the artist, courtesy Image Text Ithaca Press

Ultimately, Image Text Ithaca Press wants people to look at what they publish and feel like “I haven’t seen this before,” “I haven’t felt this before.” On their to-do list is to publish a novel with no pictures, and a book of images with no text at all; Muellner says that they want to prove that thinking about language and images together can also mean that sometimes you may decide that one of them is unnecessary. With its continuous push to find innovative approaches to integrating words and photos in thoughtful and bold ways, and to collaborate with both established and emerging artists, ITI Press is one of the publishers that not only sets a particular and focused agenda for the bookmaking scene, but also uses its resources to create an engaged community around its practice.

Olga Yatskevich is a cofounder of 10×10 Photobooks, a multiplatform project that highlights photobooks and engages the photobook community. She coedited the most recent 10×10 publication, How We See: Photobooks by Women (2018).

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Publisher at the Forefront of Photographic Literature appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 28, 2019

Aperture Capital Campaign Auction, presented by Christie’s, Wednesday, October 2, 2019

Lot 229

Paolo Ventura, Domenica Pomeriggio, 2019 Courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

Lot 221

Richard Misrach, Untitled (20402#FC), 2011Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York; and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

Lot 203

Imogen Cunningham, Banana Plant in Garden, late 1920s

Courtesy the Imogen Cunningham Trust

Lot 227

Judy Glickman Lauder, Bird Migration, Quebec, 1998

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Lot 231

Todd Hido#2319-b, 1999, from House Hunting

Courtesy the artist and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Lot 230

Matthew Brandt, 000263751, Demolition of L.A. High School, 2013, from DustCourtesy the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Lot 241

William Wegman, On and On, 2015 Courtesy the artist

Lot 243

Laurie Simmons, How We See/Anmari (Pink/Black Shirt), 2015

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Internationally acclaimed artists, collectors, and gallerists have generously donated works for a special photography auction, to be presented by Christie’s New York on October 2, 2019. All proceeds support Aperture’s 20/20: A Bold Vision capital campaign, directly funding Aperture’s purchase of a new space in Manhattan—a flexible meeting, education, and event space and HQ for its global publishing operations.

Since its founding in 1952, Aperture has propelled the vision and dialogue that have shaped the course of photography, and your support will enable Aperture to serve the next generation of artists and thinkers, driving the medium forward. The auction features fifty-four lots, including photographs by Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Imogen Cunningham, Walker Evans, Nan Goldin, Todd Hido, Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao, William Klein, Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Joel Meyerowitz, Richard Misrach, Vik Muniz, Paul Outerbridge, Herb Ritts, Stephen Shore, Laurie Simmons, Paul Strand, and Hank Willis Thomas.

View a catalogue of photographs offered by Christie’s to benefit Aperture here.

View the full details of the Christie’s sale here.

The post Aperture Capital Campaign Auction, presented by Christie’s, Wednesday, October 2, 2019 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

August 22, 2019

Announcing the 2019 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Jury

We are happy to announce the jury of the 2019 Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist:

Amanda Maddox is associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum. She has curated or cocurated numerous exhibitions, most recently Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story and Dora Maar. Her publications include Thomas Annan: Photographer of Glasgow (Getty, 2017) and Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows (Getty, 2015).

Joanna Milter is the director of photography at the New Yorker, overseeing all photography for the print and digital versions of the magazine, in addition to Photo Booth, the magazine’s photography blog. Previously, Milter spent eleven years as a photo editor at the New York Times Magazine; for the last four of those years, she was the deputy photo editor.

Drew Sawyer is the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum, where he recently organized the exhibitions Garry Winogrand: Color and Liz Johnson Artur: Dusha (both 2019). Previously, he served as associate curator of photography at the Columbus Museum of Art.

Lesley A. Martin is the creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review. In 2012, she cofounded the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.