What Is Gen Z’s Influence on Photography?

“There is no work of art in our age so attentively viewed as the portrait photograph of oneself, one’s closest friends and relatives, one’s beloved,” wrote the art historian Alfred Lichtwark in 1907. More than a century later, with the newfound ubiquity of the camera, Lichtwark’s prescience can be felt all around: the empty streets and cafés so tenderly photographed by Eugène Atget at that time are no longer empty in modern pictures. Today’s young photographers predominantly cite Cindy Sherman, dressed up as different characters in her eerie and melancholic self-portraits, as their greatest inspiration.

For twenty years, Photo Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, has sought to give a platform to young artists—and explore what defines their generation’s artistic output—first with the exhibition ReGeneration: 50 Photographers of Tomorrow in 2005 and, most recently, with Gen-Z: Shaping a New Gaze, which opened in September and brings together sixty-six image makers from around the world. Curators Nathalie Herschdorfer, Julie Dayer, and Hannah Pröbsting decided to shape the show in collaboration with the photographers, allowing each to include a statement that is showcased alongside their work. It was important, Pröbsting says, to create a show that includes the artists’ perspectives, rather than leaving them outside the process, which might have resulted in an anthropological approach. Instead, distinctive themes emerge from the photographers’ words as much as from their images.

What connects this group of emerging artists is their use of the camera as a tool for self-expression. Not much traditional documentary work is found on the walls; instead, interiority abounds. But this is not a study in myopia. Rather, the exhibition provides insight into how young artists are using photography to grapple with self-understanding and rebelling against the crushing weight of conformity imposed by various cultural norms and expectations. I recently spoke with artists Isabella Madrid (Colombia), Fatimazohra Serri (Morocco), Ben Hubert (United Kingdom), and exhibition curator Hannah Pröbsting to discuss this new generation of image makers, how growing up in a digital landscape has shaped their work, and their outspoken approach to identity.

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Faja as Myself During My First Communion, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Faja as Myself During My First Communion, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata© the artist

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Horse, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata

Isabella Madrid, Self-portrait with Horse, 2024, from the series Buena, Bonita, y Barata© the artist

Christina Cacouris: Self-portraiture was a predominant motif of the exhibition; the word identity came up a lot in the artistic statements. What role do you see identity playing within your work?

Isabella Madrid: Self-portraiture has been a tool since I was thirteen years old. It’s the window that allowed me to begin making art. It shaped how I understand my identity. It’s this combination of so many stories that are mine but also don’t only belong to me—this whole universe of Colombian women, how my mother’s identity has been shaped by her upbringing, my grandma’s, my friends’—how all of these stories come together. I take little pieces from everything and make the image and make my own identity. I think that plays into my relationship with social media and building these characters, storylines, plays where you have all these elements coming from so many different places.

Fatimazohra Serri: I grew up in a conservative community in Morocco. I was forced to wear a hijab at the age of fourteen. I grew up in that community not having my whole freedom, so photography was the thing that helped me to express myself, my struggles, and the women that were in the same community as me. I didn’t study art; I was an autodidact. I started with my phone at first. I tried to express my anger and my denial for my situation in pictures and turn them into a narrative that speaks for itself.

Ben Hubert: The project that I’ve been doing recently is an observation on social shifts. It’s still quite personal to me. Self-portraiture also just lends itself to the way that I work. I go into a studio without much of an idea of what I’m aiming to get out of it.

Hannah Pröbsting: I think that identity is always at the center of an awful lot of people’s work. What I think was really different about this generation of work was the strong number of artists in particular presenting their work as self-portraiture in a very performative way. There is this very performative nature of not just saying this work is about identity, but this work is a self portrait, and I am completely in control of how I am reappropriating something.

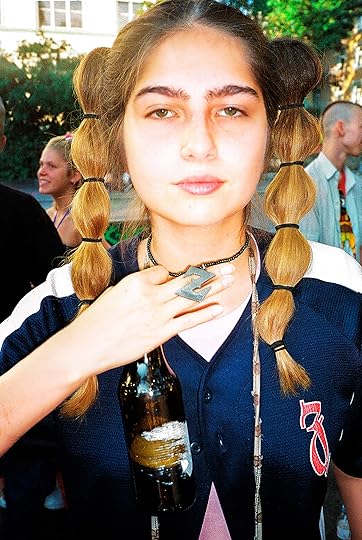

Ziyu Wang, Lads, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boys, 2022

Ziyu Wang, Lads, from the series Go Get ‘Em Boys, 2022© the artist

Cacouris: Building off the theme of performance, the concept of gender as a type of performance felt inherent in a lot of the work. How do you see gender in terms of a performance? How did you want to relate that in your work?

Madrid: In this project specifically, I was looking into what being a woman in Colombia meant. And that’s a whole universe that I had to really dissect and translate into visual codes and have a reading of gender in Colombia. It was very tied into how you look physically, what your body is supposed to look like, what your role in society is supposed to be, and tied into religion, into violence with your own body, subjecting your body to very violent procedures like plastic surgery.

Serri: As I mentioned before, my work is centered around women, especially in the conservative community. Ironically, when I wanted to work with males, I couldn’t; in my city, you can’t go into an apartment or somewhere with a man and do that. Someone would call the police. So I was limited to shooting on the roof of my house with my sister. Even when I wanted to talk about women and how they are oppressed, I couldn’t include men to express those things. I was even oppressed in speaking about these women.

This generation, they are not afraid of anything. They are more courageous, they are more bold, more creative.

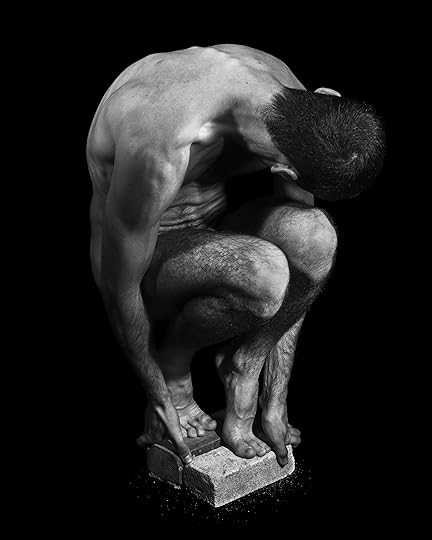

Hubert: Initially, there was some part of me that wanted to fight or at least push in the right direction for a general representation of men in terms of their ability to be vulnerable, to be comfortable and confident with what their sexualities are. The work took more of a quiet observatory approach on that subject, but within that, I was definitely using history in art as a way to try and tackle gender.

In a sense of sculptures of the male form throughout history—if you’re looking maybe at the Renaissance period or even ancient Greek—there’s this femininity and vulnerability that you see in some of these sculptures, and I’ve always found it interesting how idolized they are and how people look up to those. But in the present day, where I’m from, people have something against the idea of a naked man, predominantly straight men, that is probably homophobic. Photography for me was a way to bridge the gap between the male form within art and the actual male form, and find a space for it to exist comfortably.

Noah Noyan Wenzinger, from the series Noyan, 2015–22

Noah Noyan Wenzinger, from the series Noyan, 2015–22© the artist

River Claure, Yatiri, Puma-Punku, Bolivia, 2019, from the series Warawar Wawa (Son of The Stars), 2019–20

River Claure, Yatiri, Puma-Punku, Bolivia, 2019, from the series Warawar Wawa (Son of The Stars), 2019–20© the artist

Cacouris: How did your upbringings in a digital world impact your decisions to make photographs as an artistic practice?

Madrid: For me, there’s no photography without social media. Around eleven or twelve I started getting access to digital devices, and all I was doing was looking at images. I had already tried drawing, I had tried painting, but it never felt interesting because it was a kind of replication. And I think it was missing a subject, a person. I wanted a face, I wanted an expression, I wanted a character from the beginning. And I wanted to play into these social media websites, like Tumblr, where my visual collective was born. So it’s completely connected, and I’ve been sharing my self-portraits from when I was thirteen.

Serri: I was introduced to photography by friends. I had a lot of Moroccan friends who were doing photography online. I grabbed my phone, and I started shooting street photography for a few months just with my phone, and I was posting them on Instagram. Then I thought about experimenting in conceptual photography. And I didn’t think about it as art; I didn’t say I was doing something artistic. I was just posting on social media. Then people started liking my work. The algorithm was boosting pictures and art, so it reached a lot of people.

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos© the aritst

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos

Ben Hubert, Untitled, 2024, from the series Plinthos© the aritst

Cacouris: Something I found interesting in your work was the idea of the masks we wear. Ben, in one of your images you’re holding a plaster mask in front of your face; Isabella, you’ve painted your face in gold; and Fatimazohra, you’re concealing your face with the camera. I’d love to know more about the interplay between revealing yourself through self-portraiture and simultaneously obscuring a part of yourself.

Hubert: With a lot of the images that I’ve taken, I’m avoiding my face being in the work. I wanted a sense of it being about more than just myself, with the subjects that I’m tackling. Putting the mask into it, because it’s molded on my face, it empowered me slightly while also giving me a space personally within the project, which I don’t think otherwise would have been there. There’s something theatrical about it as well—the performance aspect—it feels like the old theater masks, in some ways. Also, a little bit like a death mask. The material has sculptural qualities, in a decaying way, and a level of that idea of the man crumbling.

Madrid: For me, it started with gold as a material because I wanted to think of different representations of Colombian bodies in history, and then my mind went to pre-Columbian Indigenous artifacts, and how we are known for these sculptures and masks made in gold, which were stolen through colonization. But it’s still a big part of our culture, this material and what it represents, also this shiny object to be commercialized—that was the starting point to turn it into this mask, this way of commercializing my own body, and then it became this drag thing. In each photo I wanted to have these drag characters, and that helped me understand what each mask was doing for each character. But it started with the material itself.

Serri: For me, it was for protection. As in most of my earliest works, you can see that the face is always hidden under the burka, or the camera, because back then I was only shooting myself, my sister, or some friends. I was living in Nador, and taking a picture of yourself and posting it online was a terrifying idea. My family had no idea I was doing that, and I couldn’t risk putting my friends’ faces online. It was a way to protect me, my sister, my friends, from the society, because the pictures were a bit controversial in my community. But since I moved from Nador—I’m in Marrakesh—I have more freedom to work with male, female models, I’m free to show faces. The situation has changed a lot, but back then it was for protection.

Fatimazohra Serri, L’origine du monde, 2018, from the series Shades of Black

Fatimazohra Serri, L’origine du monde, 2018, from the series Shades of Black © the artist

Cacouris: I understand. It makes sense why you were making pictures, and what it did for you, but why do you think your sister and friends wanted to participate? What do you think being photographed offered them?

Serri: I’ve never thought about it, but I think my sister did it because it was an exciting idea; maybe she wanted to support me. I assured them their faces were not going to be online, and they felt it was safe, but I appreciated that from them. Maybe because they wanted to do something new, something different. They believed in what I was doing.

Cacouris: I noticed that remote releases are prevalent in a lot of the work in the exhibition, including yours, Isabella. It almost feels like an anachronism to see them in photographs today. I’m curious why you decided to include it.

Madrid: I had always done digital photography, and I had also used a digital remote control. But I hid it. I was always trying to hide it and to contort my body so you wouldn’t see it. And then starting to study photography and studying photographers who actively reveal the device gave me another layer of understanding of what it means to build a self-portrait.

Pröbsting: So many of the projects that are in the exhibition are about reappropriating different things. Some are reappropriating words that have been used as slurs against them or reappropriating expectations that have been forced upon people. This is about saying, I am in complete control of this. No one is making me take this picture. I’m in this position. And this is me putting myself in this position to tell you something.

Fatimazohra Serri, Half Seen, Half Imagined, 2023, from the series Shades of Black

Fatimazohra Serri, Half Seen, Half Imagined, 2023, from the series Shades of Black© the artist

Cacouris: In response to the title of the exhibition, how would you each define the “new gaze” this generation is creating?

Madrid: It’s just so honest. I love the honesty and the rawness of it all. We’re not afraid to be greedy anymore. We’re not afraid of anything, really. Because the situation right now feels so hopeless, in a way, it’s like, we have nothing else to lose.

Hubert: Thinking about the future, there are so many common goals and topics being tackled across so many cultures and so many countries. The world’s never been as connected as it is now, online and in real life.

Serri: I agree with Isabella. This generation, I think they are not afraid of anything. They are more courageous, they are more bold, more creative.

Pröbsting: Photography has offered this generation a platform to speak for themselves, and maybe that comes from platforms like Instagram, maybe it comes from the fact that many, many young people even from an early age have a camera with them. But no longer are we relying on people from the outside to go in and represent different cultures, different communities, different voices. Through photography, this generation is able to advocate for themselves and have their own voice.

Gen Z: Shaping a New Gaze is on view at Photo Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland, through January 2, 2026.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers