David Gessner's Blog, page 15

August 26, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: How Not to Write a Fan Letter

As anyone who has ever been in a writing workshop knows, you say the nice stuff first and slide in the criticism in later. Apparently, this is not common knowledge in the world beyond workshop walls. At least not based on some of the letters I’ve gotten about my new book this summer. Purportedly these are “fan letters,” though some of them stretch that definition.

As anyone who has ever been in a writing workshop knows, you say the nice stuff first and slide in the criticism in later. Apparently, this is not common knowledge in the world beyond workshop walls. At least not based on some of the letters I’ve gotten about my new book this summer. Purportedly these are “fan letters,” though some of them stretch that definition.

Here’s an example from a letter I got last week:

Dear David,

I recently bought a copy of “All the Wild that Remains.” Although I thought it got off-track and dragged a bit in spots (sorry!), overall I enjoyed it…”

How exactly should I respond to that? Well, I can tell you how I did respond: I stopped reading (sorry!). Which brings me back to my point about the workshop model being a good one here. If your real reason for writing an author is to criticize their work, then maybe at least Trojan-horse that in later and say some nice stuff first. It’s a Miss Manners kind of thing.

For the purpose of this blog post, which I know is kind of off-track and draggy in spots, I did go back and skim the entire letter. It turns out our letter-writer went on to add that my book was “well-written and well-researched” (thanks!). Then: “That is, except for one glaring omission, about which I hope you’ll let me have my say.”

The next four paragraphs explained that my omission was spending too few pages on the damage that ranching has done to western lands. Which is actually a valid point, (and one I might have been more open to had he not begun his letter with an insult). Of course it turned out that our ill-mannered letter writer had a self-published book on this very subject…..

I need to stress that this guy’s letter was not a mean or spiteful. This guy is no Dobyx. He was just a little weak in the tact department. So that’s this week’s bad advice. Say it with flowers first. Then slip in the arsenic.

August 25, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “Cloudsplitter,” by Russell Banks

Russell Banks

Upon recently finishing Cloudsplitter, by Russell Banks, I began to think about who are the best living American novelists. My reflections led to the Internet where, surprise, surprise, there were endless and varied lists. There was unanimity only regarding the upper echelon: Pynchon, Roth, and Morrison. Russell Bankswas nowhere to be found on any of these lists, an egregious and inexplicable omission.

Over a career spanning four decades, Russell Banks has produced a body of work startling in its diversity and relentless brilliance. After early short story collections he published Continental Drift, a Pulitzer nominated novel describing the sense of ennui and uprootedness in contemporary America. With Affliction and The Sweet Hereafter, both made into major motion pictures, he captured the claustrophobic xenophobia at the heart of New England culture more devastatingly than any writer since Hawthorne and with Rule of the Bone he offered a classic bildungsroman for the stoner age. More recently he published Under the Skin, a heartbreaking depiction of the way that contemporary America deals with an often unjustly marginalized underclass. But his masterpiece is Cloudsplitter, an historical novel depicting the life of the abolitionist John Brown as told by his son, Owen.

The ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 has been credited with forcing many Americans to stop straddling the fence on the issue of slavery, opening the path for the Civil War. In the aftermath of that raid, mainstream historians embarked upon a concerted re-imaging of John Brown. While Brown had previously been considered a hero by millions for his abolitionist stance, that hero image was problematical; after all, we can’t count among our heroes a man who tried to seize control of a federal armory as part of an attempt to foment a national slave rebellion. And so the propaganda machine went into overdrive, depicting John Brown as a terrorist and a madman, a rewriting of history that persists in many accounts to this day (this process is brilliantly recounted by historian James Loewen in Lies My Teacher Told Me).

The ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 has been credited with forcing many Americans to stop straddling the fence on the issue of slavery, opening the path for the Civil War. In the aftermath of that raid, mainstream historians embarked upon a concerted re-imaging of John Brown. While Brown had previously been considered a hero by millions for his abolitionist stance, that hero image was problematical; after all, we can’t count among our heroes a man who tried to seize control of a federal armory as part of an attempt to foment a national slave rebellion. And so the propaganda machine went into overdrive, depicting John Brown as a terrorist and a madman, a rewriting of history that persists in many accounts to this day (this process is brilliantly recounted by historian James Loewen in Lies My Teacher Told Me).

The John Brown of Cloudsplitter however, is a man driven by the twin engines of religious fervor (which some would argue is a form of insanity) and a moral abhorrence of the institution of slavery. Our narrator, Brown’s third eldest son Owen, is not so much unreliable as unsettled, but as a narrative device to plumb the depths of his father’s enormously complex character, he offers the perfect perspective. Tortured by his own perceived shortcomings, Owen eventually comes to accept and embrace that his and his father’s destinies are irrevocably entwined. He argues fiercely and persuasively that his father was not insane; rather he was a man of uncompromising passion in an era when many preferred to pretend that compromise might yet staunch the bloodletting that seemed increasingly inevitable.

Banks portrays John Brown as a man concerned with doing what he perceived as morally right, while also being fully aware that his passions and practices placed him at odds with mainstream white society. As Banks said in a 1998 Paris Review interview: “I’m a white man in a white-dominated, racialized society; therefore, if I want to I can live my whole life in a racial fantasy. Most white Americans do just that. Because we can. In a color-defined society we are invited to think that white is not a color. We are invited to fantasize and we act accordingly.”

John Brown resisted that fantasy and Cloudsplitter masterfully recounts the power of that resistance, while displaying the prodigious gifts of one of America’s finest living novelists.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

August 24, 2015

Night at the Movies: “The End of the Tour”

Just came from “The End of the Tour,” the new movie based on a failed Rolling Stone story by David Lipsky, who joined the end of David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” tour 12 years before Wallace’s terrible suicide. It’s movie of little movement, mostly two guys talking, one in the throes of huge new fame, the other not there or ever going to be, and jealous, and yet it’s more gripping than the thriller we saw next in our Monday thunder double header, no need to mention. It’s funny, charming, dark, and portrays two layered and unequal men jousting. As the decades pass, only one of them gets to live and tell the story. A great movie, especially for the writers among us, so much to think about, though no doubt aficionados of the late great savant will find plenty to complain about, while his haters will continue to hate. But that should be even more fun. Go see it.

The actual DFW

August 18, 2015

Table For Two: An Interview with T.C. Boyle

Debora Black: You always seem to be having a really good time writing your characters and their situations—even when the subject matter wouldn’t suggest a good time. But you like to toy with things, amp up a situation and play it out. In your latest novel, The Harder They Come, you transform sunny California, its middle-class inhabitants, and their American ideals into a war zone. What compelled you to write this story?

T.C. Boyle: What prompted me to write this novel is the Mad Max warzone of gun violence this country has become. Sadly, I could have chosen any number of real-life incidents to write about, but this one is based on a series of occurrences in Ft. Bragg, California, in 201l. Many of the details of Adam’s story derive from the extensive police report of the case.

Debora: The Harder They Come—great title! Does the book have anything to do with Jimmy Cliff?

T.C. Boyle: Very much so. I am referencing song and film both, which celebrate gangster life in Jamaica, and, of course, I am making use of the same expression Jimmy Cliff used: “The harder they come, the harder they fall.” That’s a proposition. The novel wants to find out if it’s true and what it means below the surface.

Debora: For me, your characters made for a pins-and-needles experience, start to finish. It’s not just your principals, Sten, Adam, and Sara, who are tightly wound and in conflict with their worlds. Christabel, the Mexicans, Carey, Carolee, the police, the entire community of characters have something to protect and are, at varying degrees, ready to roll when threatened. Was it difficult to carry the tension and suspense through the entire book?

Debora: For me, your characters made for a pins-and-needles experience, start to finish. It’s not just your principals, Sten, Adam, and Sara, who are tightly wound and in conflict with their worlds. Christabel, the Mexicans, Carey, Carolee, the police, the entire community of characters have something to protect and are, at varying degrees, ready to roll when threatened. Was it difficult to carry the tension and suspense through the entire book?

T.C. Boyle: Aw, shucks, I’m just doing what comes natural. I see a vision and try to translate it into words. All the complexity and interweaving you find in the book derives from this organic process of writing.

Debora: Adam lives inside a haze of alcohol and drug intoxication that exacerbates his departures into increasingly severe schizophrenic episodes. In the way you deliver him, his thought processes and behaviors seem authentic. And the way everyone reacts to him, misinterpreting his problem and trying to fix symptoms, seems authentic. Is his character invented out of personal experience of any sort, or is he entirely imagined?

T.C. Boyle: I wrote about a schizophrenic (Stanley McCormick) in Riven Rock, so I had that experience to draw from. Plus, as you will know from my article, “The Dark Times,” on Buzzfeed, one of my very closest boyhood friends spiraled downward into severe schizophrenia. I am channeling him.

Debora: At the Steamboat Springs reading, you mentioned that you don’t collaborate with editors and never have. You said that you begin each writing day by re-writing what you wrote the day before. So the writing is done when you reach the final pages. Your stance seemed to shock a lot of the audience. Will you define the role of the writer and the role of the editor?

T.C. Boyle: Each to his own. Many writers need and want to collaborate with their editors. I have never felt the need. Which is not to say that I don’t listen to what my editors have to say once the ms. is delivered, just that what I deliver is in finished form. I work in isolation and have never felt the need to bounce ideas (or chapters) off of anyone.

Debora: You have written so many beloved and awarded books—The Tortilla Curtain, Drop City, World’s End are only a few. Aside from talent and commitment, what has enabled your writing success along the way?

T.C. Boyle: I have been very fortunate to have attracted a devoted following of readers both here and abroad, without compromising my artistic vision or ever attempting to calculate what might or might not appeal. I do my thing. Readers have embraced it. Happy story. Period.

Debora: Who are some of your favorite writers, and how have they influenced you?

T.C. Boyle: I love the absurdist playwrights (Beckett, Ionesco, Genet), satirists like Evelyn Waugh and Kingsley Amis, fantasists like Calvino and Garcia-Marquez, wildmen (and women) like Robert Coover, Thomas Pynchon, Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner. All literary work is an amalgam of influences. Look deep and ye shall find.

Debora: I love following you on Twitter—you’re always up to something kind of strange, like relocating rats and messing around with leeches. And there’s the fear of toilet flushing, and other water concerns. Do your tweets connect to the book you’re working on—The Terranauts? You say, science fiction—but not really. Will you tell us anything more?

T.C. Boyle: Thanks. I recently discovered Tweeting (my publisher set up an account when I went off on the recent tour). I’d never felt the need for social media since my website (and blog), invented by my son Milo when he was a high-schooler, is now in its seventeenth year and flourishing. But now the Twitter feed appears on the blog page, so the two are combined. I see the website as a fan site, as well as an educational site for journalists, students writing papers, etc. The Twitter feed is a place for quips, as I snapshot my way through my daily life. People seem to like seeing something of how I go about my day and what I’m thinking (which is primarily a reflection of my twelve-year-old’s brain, always chock full of wonderment). What great fun it is to tweet. Will it last? We shall see.

Debora: Thanks so much for spending some of your summer with us. It’s been a busy time for you, and we appreciate that you were able to fit us in. I’m looking forward to The Terranauts.

Debora Black lives in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

August 13, 2015

Good Advice Thursday: Authors, Keep your Copyrights!

Most agents and many writers know to strike any clause in a contract that gives away copyright, but not all. Here, from the Author’s Guild (which you might want to join if you’re not already a member) is the straight poop on a terrible practice that seems to be growing. And ask your university press to cut it out. You can also read it here, on the Author’s Guild website. [Used by permission.]

Authors should not assign their copyrights to publishers. As our Model Contract emphasizes:

“CAUTION: Do not allow the publisher to take your copyright or to publish the copyright notice in any name other than yours. Except in very unusual circumstances, this practice is not standard in the industry and harms your economic interests. No reputable publisher should demand that you allow it to do so.”

Most trade publishers do not ask for an outright assignment of all exclusive rights under copyright; their contracts usually call for copyright to be in the author’s name. But it’s another story in the world of university presses. Most scholarly publishers routinely present their authors with the single most draconian, unfair clause we routinely encounter, taking all the exclusive rights to an author’s work as if the press itself authored the work: “The Author assigns to Publisher all right, title and interests, including all rights under copyright, in and to the work…”

Bad idea. As Cornell University’s Copyright Information Center advises, “When you assign copyright to publishers, you lose control over your scholarly output. Assignment of copyright ownership may limit your ability to incorporate elements into future articles and books or to use your own work in teaching at the University.” And those are by no means the only potential problems. That’s why we admonish authors never to assign a copyright to a publisher or to allow a book’s copyright to be registered in any name but the author’s.

Yet the copyright grab remains endemic among university presses. To find out why, we recently canvassed several academic authors. Every form agreement that a university press had initially offered these authors contained the copyright grab clause. And yet every author we know of who requested to retain copyright was able to get the publisher to change the agreement.

The problem is that most academic authors—particularly first-time authors feeling the flames of “publish or perish”—don’t even ask. They do not have agents, do not seek legal advice, and often don’t understand that publishing contracts can be modified. So they don’t ask to keep their copyrights—or for any changes at all. Many academic authors tell us they were afraid to request changes to the standard agreements for fear that the publisher would pull the plug on their books. One said that when his first book was published in 1976, he never even read the contract and would (and did) sign anything to get published.

So we asked several university press representatives “Why is a clause granting copyright to the publisher the default language in university press agreements?” Here’s what they said (sometimes after consulting with their lawyers):

“We are a non-profit press and we can’t do things that commercial trade presses do.”

“The press is better positioned than the author to defend the copyright by use of premium outside counsel, as well as by use of an anti-piracy service to curb piracy.”

“Having the copyright in the press’s name allows us to work freely to maintain the integrity of the work and maximize its publishing life.”

“We’re close enough to the work to do the best job and we have incentive to protect the publishing mission.”

“It makes it easier for the press because it doesn’t have to ask for an author’s approval when permission uses are granted.”

“It eliminates any confusion as to which party should be contacted regarding re-use and sub-rights, etc. and it simplifies things in regards to piracy as well. Trade authors are more likely to have agents who may retain certain sub-rights and exploit them independent of any publisher relationship.”

Not one of these rationalizations passes the giggle test. While we recognize that most academic presses are non-profits and have narrow margins (the books tend to be scholarly and noncommercial), and many do indeed struggle to make ends meet, we take issue with the notion that taking an author’s copyright is necessary. The fact is that it simply isn’t necessary to own the entire copyright in a book (rather than licensing rights a la carte) to defend the copyright and bring a lawsuit, nor is outright ownership necessary to grant third-party licenses and permissions or to “maintain the integrity of the work and maximize its publishing life,” much less to “protect the publishing mission” (whatever that means). And when pressed, most of the editors we talked to sheepishly admitted that they always gave in when authors asked to retain their copyrights. Indeed, they confessed that they really had no clue why the default was the other way around.

University presses, we ask you to do the right thing: Revise your default boilerplate language so that the author keeps the copyright in his or her book without having to ask. Oppressive copyright grabs are routinely negotiated out of agreements by knowledgeable authors and agents, and there is no credible justification for their existence. It’s time for them to go.

Authors, keep your copyrights. You earned them.

August 9, 2015

July 29, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Summer Writing

Americans who weren’t rich started taking vacations before the civil war, and by the turn of the 20th Century, the middle class vacation had been perfected to an art form. Already at that time there were newspaper articles and library recommendations for summer reading, and already the summer reading recommendations were for fiction, preferably light, plot-driven, no “heavy biographies.” But let me propose something I’ve been trying to perfect into an art form: summer writing.

No heavy sitting at the desk all day, or beating toward miserable deadlines. Instead, a notebook at the beach, a laptop in the shade, notes during a movie on an iPhone (darkened display!), napkins at the lobster shack, a pad of paper and pencil on a hike, gin and tonics and sonnets.

I try to fit in a littl e around other summer activities, too, the way I might obsessively read a great novel, fitting it in everywhere, a few minutes whenever possible, charging toward the end of my own novel, which in conception at least is great, too. A leisurely charge, purposefully low stakes, high excitement. So, drop my daughter at dance rehearsal (her team dances at the Skowhegan Fair every summer), and head to the Old Mill Pub over the Kennebec River dam, 75 minutes exactly to eat some salmon and not just write a little, but to attack the most exciting chapter ahead, that climactic moment I know is coming, scratch scratch scratch with the pencil as the waitress scratches her head. Later, in the industrious fall, when I get to that scene, I’ll have a few good paragraphs waiting for me, paragraphs imbued with that summer mood.

e around other summer activities, too, the way I might obsessively read a great novel, fitting it in everywhere, a few minutes whenever possible, charging toward the end of my own novel, which in conception at least is great, too. A leisurely charge, purposefully low stakes, high excitement. So, drop my daughter at dance rehearsal (her team dances at the Skowhegan Fair every summer), and head to the Old Mill Pub over the Kennebec River dam, 75 minutes exactly to eat some salmon and not just write a little, but to attack the most exciting chapter ahead, that climactic moment I know is coming, scratch scratch scratch with the pencil as the waitress scratches her head. Later, in the industrious fall, when I get to that scene, I’ll have a few good paragraphs waiting for me, paragraphs imbued with that summer mood.

Another characteristic of summer reading is eclecticism, a little of this, a little of that, guilty pleasures, new authors. Summer writing means trying out poems if you’re prosaic, or trying scenes you thought you’d never write–spies, kids in trouble, haikus, seance transcriptions, I don’t know… But I’m the guy who stands in the stream an hour staring and calls it writing.

Bill Roorbach is a writer and gardener of weeds finally estivating after a winter and spring of hard travel and tough writing.

July 28, 2015

Guy at the Bar: Vince Passaro on the Passing of E. L. Doctorow

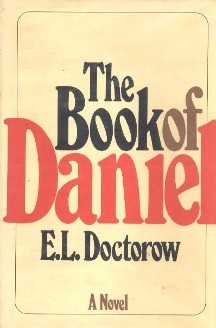

E. L. Doctorow

E.L. Doctorow departed from us this week, succumbing to lung cancer complications at the age of 84. It was my good fortune to meet him in the early 1990s and share a few brief conversations with him in the years that followed. There was an expression used among the elders on my Italian side: mal’ a visage, mal’ di cuore, buon’ a visage, buon’ di cuore, which means basically that the heart shows on the face. Doctorow – Ed to his friends – had that kind of expressive face; a moment’s engagement with him and you knew you were dealing with a thoughtful, polite, supremely gentle human being. A tall man, he never loomed, always stooped a little for those of us who couldn’t breathe the air up there where he was.

He was also one of the half dozen biggest literary stars of his generation. The best of his novels – The Book of Daniel, Ragtime, World’s Fair, City of God, Billy Bathgate, and The March – all composed in the mode of lyrical realism, some political, some historical, more than one philosophical, told through varying and sometimes experimental narrative devices – are major works of fiction and will remain so for a good time to come. (Then likely they will disappear for a while and then, I bet, they will come back. That’s how it usually works. Very few writers make it into the next century without a revival.)

A few of Doctorow’s books sold enormously, a few were made into very good films. His was, in short, a very important literary career. Yet it’s hard to imagine (though of course it could be true) that Doctorow as a writer influenced anyone, in the literary sense, stylistically. Young writers of my time were influenced by James Baldwin and Norman Mailer, by Flannery O’Connor and John Updike. By Nathanael West or William Burroughs. Nowadays, I don’t know. I’d guess George Saunders, David Wallace and Miranda July. I say the names, you can almost hear the authorial voices. But Doctorow’s style was invisible, as a great carpenter’s style can be invisible. And while politics and American history are never far from his mind, his books are radically different from each other, to a degree not true of any other well known author of his time.

A few of Doctorow’s books sold enormously, a few were made into very good films. His was, in short, a very important literary career. Yet it’s hard to imagine (though of course it could be true) that Doctorow as a writer influenced anyone, in the literary sense, stylistically. Young writers of my time were influenced by James Baldwin and Norman Mailer, by Flannery O’Connor and John Updike. By Nathanael West or William Burroughs. Nowadays, I don’t know. I’d guess George Saunders, David Wallace and Miranda July. I say the names, you can almost hear the authorial voices. But Doctorow’s style was invisible, as a great carpenter’s style can be invisible. And while politics and American history are never far from his mind, his books are radically different from each other, to a degree not true of any other well known author of his time.

I once heard him say, during the q-and-a after a reading, that he could never get far in a book, in “trying to write” a book, until a voice came to him: the voice of the book. This voice gave him entry: snuck him in. It would, he said, take over, and then he knew he was irrefutably on the way. Keep in mind, unlike with Mailer, say: it was not Doctorow’s voice: it was another voice as if from outside him. This description provided vital confirmation for me, as a young writer at the time, and for a few others whom I knew, that the process has no formula, that it is a mystery, and that in creating characters we must give them freedom to act and speak as they will, not as we plan for them to do. Otherwise they are soon dead, and to push dead characters around to get a facsimile of a story or a novel out of them is like taking a blue whale for a walk in the park. A lot of writers do it; they are proud of their work ethic. But it is of little benefit.

At the same time, Doctorow’s work is intensely cinematic. The March, (2005), a late novel about the Civil War and one of my favorites of his, unrolls at you like one of those Cinerama films of the early 60s, shot wide and with a hell of a lot of action on the screen at any one time. Frequently in The March you can see the entire landscape (this is a tradition, almost, in Civil War novels: take a look at the opening of The Red Badge of Courage from more than a century prior). I can’t recall a scene in Doctorow that was not absolutely visible to the reader, effortlessly available to the eye, with foreground, background, frames left right above and below all sensible and clear. You never doubt the shape of his barrooms or the orientation of his building’s facades. It is never unclear to you which side of the car someone is getting into or out of, whether the movement is to the left or right. You encounter no labor in his work to show you these minor but crucial details: it’s all there, smooth, tight, and ready, like a hotel bed. You’d never notice the skill of it because you never noticed the IT. He was a careful writer, a traditional and flawless craftsman with a very interesting experimental side. It strikes me now, thinking on the matter, as no wonder that the film versions of his novels – Ragtime, notoriously – irritated and even horrified him. He SAW these things as completely as they can be seen, heard them as God hears his creation; most good writers do, but Doctorow I suspect remained attached to the particularity of the structures and faces and voices and insistent tactile realities of his books. What director and screenwriter could do anything but spoil them?

At the same time, Doctorow’s work is intensely cinematic. The March, (2005), a late novel about the Civil War and one of my favorites of his, unrolls at you like one of those Cinerama films of the early 60s, shot wide and with a hell of a lot of action on the screen at any one time. Frequently in The March you can see the entire landscape (this is a tradition, almost, in Civil War novels: take a look at the opening of The Red Badge of Courage from more than a century prior). I can’t recall a scene in Doctorow that was not absolutely visible to the reader, effortlessly available to the eye, with foreground, background, frames left right above and below all sensible and clear. You never doubt the shape of his barrooms or the orientation of his building’s facades. It is never unclear to you which side of the car someone is getting into or out of, whether the movement is to the left or right. You encounter no labor in his work to show you these minor but crucial details: it’s all there, smooth, tight, and ready, like a hotel bed. You’d never notice the skill of it because you never noticed the IT. He was a careful writer, a traditional and flawless craftsman with a very interesting experimental side. It strikes me now, thinking on the matter, as no wonder that the film versions of his novels – Ragtime, notoriously – irritated and even horrified him. He SAW these things as completely as they can be seen, heard them as God hears his creation; most good writers do, but Doctorow I suspect remained attached to the particularity of the structures and faces and voices and insistent tactile realities of his books. What director and screenwriter could do anything but spoil them?

Doctorow, born and raised in the Bronx of the 1930s and 40s, was of that fortunate generation that ended up with big apartments on the West Side and houses out east for summer and a maze of professional connections in Doctorow’s case going back to 1959 when he started as an editor for New American Library (NAL). He was later editor in chief and publisher of Dial Press, a very distinguished and successful imprint. He had that soft-spoken, uninsistent intelligence that marks a great editor. He quit in 1969 to finish his book about the Rosenbergs and their children, The Book of Daniel — which many of us oldsters consider his best work, because the subject feels so vulnerable and so close, and the politics so important. He knew everybody, everybody knew him, he didn’t have to move to Laramie or State College to find a $38,000 teaching job. He was a passionate leftist, and got in trouble with two scorchingly political commencement addresses, one in 1989 at Brandeis, attacking the senseless brutalities of the Reagan years, and one at Hofstra University in 2004, attacking the even less sensible brutalities of George W. Bush. In the Brandeis speech he cited Sherwood Anderson to put his finger on the biggest problem traditionally in American culture and politics: it was Anderson’s conception, he said, that you could take any good idea, like patriotism or thrift or self reliance, and squeeze it too hard, hold it too far apart from other good ideas that modify it, until it becomes a lie, and you, the holder, become a grotesque. This, to him, was what had happened to America. He never stopped fighting against it.

[This piece originally appeared, in slightly different form, in the New York Observer.]

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

July 27, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “The Brothers: The Road To An American Tragedy,” by Masha Gessen

The universal response to the Boston Marathon bombings was revulsion, horror and incomprehension. The media’s talking heads incessantly characterized the Tsarnev brothers as Islamic terrorists/jihadists. In her account of the circumstances leading up to and the emotional aftermath of the bombing, journalist Masha Gessen offers up a more thoughtful and nuanced perspective on the causes of the tragedy and its broader implications in, The Brothers: The Road To An American Tragedy.

Masha Gessen

Gessen spends very little time discussing the actual bombing; she refuses to serve as judge, jury and executioner. Rather, she offers a narrative of the modern American immigration saga in an increasingly paranoid, post 9-11 world. Today’s newly arrived immigrants, like the Tsarnaev family, quickly discover that the streets are not paved with gold and any notion of a meritocracy is laughable, particularly when one is from a part of the world perceived to be a breeding ground for terrorism. There is a sense of inevitability as Gessen recounts the slow dissolution of the American Dream for the brothers and the role that this disillusionment plays in the bombing. She absolutely does not exonerate the brothers; but she does suggest that a more critical examination of the role that Homeland Security and U.S. immigration policy and the FBI have played in Islamic ‘terrorist‘ attacks launched on U.S. soil since 9-11, might be enlightening.

Despite FBI denials, Gessen provides compelling evidence of a relationship between the bureau and the elder Tsarnaev brother long before the bombing occurred. And while the FBI denies knowledge of the brothers’ role in the bombing until after the shootout when Tamerlan died, Gessen characterizes this as “… an explanation of incompetence that strains the imagination”, pointing to tips to the FBI hotline, including one from the brothers’ lawyer-aunt who explicitly identifies her nephews from the pictures released to the media. Additionally, Gessen (and local law enforcement) wondered why FBI personnel swarmed the area around the Tsarnaev apartment after the bombing, well before the FBI had identified any suspects. Gessen writes: “Another explanation makes infinitely more sense: The FBI was setting up an operation without notifying its local partners because it needed to ensure that no other law enforcement got to Tamerlan Tsarnaev before the FBI had captured–or killed–him. In other words, the explanation that best fits the facts is a cover-up.”

So what was the nature of the relationship between Tamerlan and the FBI? In the aftermath of Tamerlan’s death, that is a question that will remain, perhaps, forever unanswered. Gessen points to the FBI’s role in ‘catching’ (entrapping?) alleged Islamic terrorist conspirators. The question becomes, would these alleged plots even have come close to fruition without the FBI’s involvement? Gessen quotes a former FBI agent who says, “When the FBI undercover agent or informant is the only purported link to a real terrorist group, supplies the motive, designs the plot and provides all the weapons, one has to question whether they are combatting terrorism or creating it…”

In the aftermath of 9-11 we have witnessed the construction of a trillion dollar security industry and the creation of a U.S. Cabinet department that are both dependent upon the specter of a boogieman and the resultant collective societal paranoia. Yet as Gessen points out in her conclusion to this fascinating and convincing work of journalism, “The rhetoric and actions of the U.S. government and its agents, in their outsize response and their targeting of specific communities, have probably done as much to create an imagined community of jihadists as have the efforts of Al-Qaida and its allies.”

While our paranoia may or may not be justified, the question must be raised, who or what should we really be afraid of?

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

July 14, 2015

“Love and Mercy” Rocks

I cried through most of “Love and Mercy” a film about the incredible Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. Partly the tears were for my own youth, but this is a sad tale–of misunderstood genius, of mental illness, of abuse. The directer is Bill Pohlad, who produced the enigmatic Bob Dylan biopic “I’m Not There” in 2007. That film used a number of actors to portray Dylan, including Kate Blanchett. This film uses two actors to portray Brian Wilson, and lets us see the actual man during the credits. And it works beautifully, an embodiment of the changes the man went through, the eras of his life. We’re all played by different actors as we grow older, aren’t we.

The music is great. That’s a case the movie makes, and decisively wins, great scenes of Brian in the studio, and Brian in his head, and Brian at his piano at home.

As a kid I adored the beach boys. In high school though, they became uncool, too sweet, perhaps, too clean. I used my Beach Boys albums as frisbees. Wish I hadn’t now. When Pet Sounds came out, early college, I didn’t know what to make of it, though some of my stoner friends swore by it. But now those songs are among my favorites. And the movie has inspired me to make a YouTube journey through the oeuvre…

It also explained my disaffection to me in a way that took me entirely by surprise, thus the tears.

See it.