David Gessner's Blog, page 11

January 27, 2016

Bad Advice Wednesday: Need a Job? Be a Writer First (from the archives)

Do not listen to this man…

Oh, I’ve seen such anguish on FB and elsewhere about the thin market in college jobs for writers. More jobs will turn up, of course, and somewhere, right now, someone’s writing up a job description that sounds a lot like you. But that September job list really is depressing. Then again, if you’ve set out to be a writer, why let the job statistics for teachers bother you? Yes, you need a way to make money, but what difference does it make how you get there, if the whole point is to buy time to write?

I always thought it was best to do work that had nothing to do with writing. So I put in kitchens and bathrooms. I bartended. I rode a horse and chased Simmental cattle around. I painted apartments in NYC. I played in bands (famously!). And when I got home from these generally lucrative activities (well, not the ranch stuff), or while I lay on the beach during all the time my night work opened up, I wrote. I didn’t really get that I was in an apprenticeship. But what I did get was that what I meant to be was a writer. Not a bartender, for example. So I didn’t take that too seriously (though I often made a teacher’s weekly salary in a night–tips). When I was done, I was done.

And not a contractor. No, I hadn’t set out to do that! Though construction got fairly serious at times… But then I’d remind myself: you, my friend are a writer. And so I’d finish up the bathroom I was working on, pinch the large wad of cash, and take as many months off as that cash would buy. And I’d write. Preferably someplace nice…

Practice novels, sure. And then stuff that was getting published. And that got me into grad school. My MFA program (Columbia U.) was wonderful as a way to focus on reading and writing among like-minded souls. I taught the undergrads (Logic and Rhetoric), and that paid my way. No different than the other work I’d done: my teaching assistantship bought me time to write. Also, grad school taught me to be poor, which was good preparation for teaching in the academy, or teaching anywhere.

After grad school, and largely because of it, I published a book, and with the degree, that made me employable. I applied for jobs and got some of them. I taught 25 years in all, promoted, tenured, endowed chair, the whole shebang. All so I could write, I didn’t forget. And when at long last I could rely on writing to pay the way, I quit teaching. Just like that.

Because I’d never set out to be a teacher.

Don’t get me wrong. I love teaching!

But I love not teaching more…

And I’m way busier than I ever was teaching, go figure…

I know it’s no fun to contemplate, but if you want to be a writer, it doesn’t really matter what else you do to get along. X dollars is X dollars, no matter where they came from.

Jesus, if you believe that, you’ll believe anything.

Be a writer first at least. Can you do that for me? Thanks.

January 26, 2016

January 22, 2016

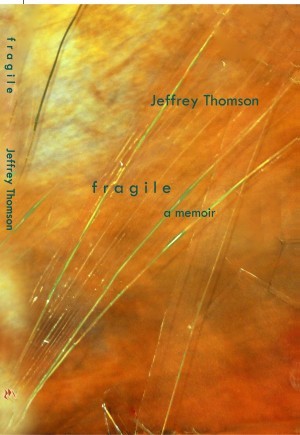

Table for Two: An Interview with Jeff Thomson, Poet and Memoirist

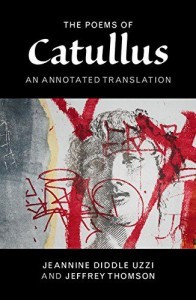

Jeff Thomson is a friend of mine, and lives in the same small town in Maine, which is Farmington. His poetry and now his memoir echo out into the world, however. Jeff spent a Fulbright year in Ireland, and returns to Costa Rica frequently both for surfing with his son and teaching a college course in the rain and cloud forests there. He’s a birder and athlete and likes a pint of beer. He’s a translator, too, and has published a juicy edition of the poetry of Catullus, rendered from the Latin. For our Table for Two meal—a fantasy, of course—he suggests the deck of the Corcovado Tent Camps adjacent to the back entrance of the Corcovado National Park (which is little more than a tapir path). So we’ll sip a couple of boozy drinks while looking over the Pacific, the primordial green of the Pacific coastline running for miles in both directions. Scarlet Macaws overhead. Spider monkeys in the wild almond. Crocodiles lying on the beach like distant logs, ceviche and patacones and margaritas made from fresh mandarina juice.

Jeff: Welcome to the Osa Peninsula.

Bill: I like. And I’ve been near here once with my family at Luna Lodge, which you kindly suggested, too. Extraordinary place. Meanwhile, warm congratulations on your memoir, Fragile. Could you tell us a little about it?

Jeff: The short answer is that fragile is about all the times I almost died. Seriously. The longer answer is that it starts with a mountain biking trip I took to Costa Rica when I was 22—I rode up the Mountain of Death, literally—and then it ends with my heart surgery and recovery a few years ago. In between the are a number of different, dangerous adventures in the rainforest and in the deserts of the American West. I also spend a lot of time wandering and thinking and teaching and learning about place and landscape and language. Discovering that these ideas are all far more complicated than we think they are and even more so how they are all tied together. And each adventure—each encounter with mortality—complicates the narrative further. In some ways, it is a typical American nature story—guy goes out into the wild and learns about the world and himself in the process of his adventures. But, I am also trying to complicate that kind of narrative, since I also talk about the return to the city and my home, and the real danger of my life—which was my own heart and the damage I was walking around with, unknowingly.

Jeff: The short answer is that fragile is about all the times I almost died. Seriously. The longer answer is that it starts with a mountain biking trip I took to Costa Rica when I was 22—I rode up the Mountain of Death, literally—and then it ends with my heart surgery and recovery a few years ago. In between the are a number of different, dangerous adventures in the rainforest and in the deserts of the American West. I also spend a lot of time wandering and thinking and teaching and learning about place and landscape and language. Discovering that these ideas are all far more complicated than we think they are and even more so how they are all tied together. And each adventure—each encounter with mortality—complicates the narrative further. In some ways, it is a typical American nature story—guy goes out into the wild and learns about the world and himself in the process of his adventures. But, I am also trying to complicate that kind of narrative, since I also talk about the return to the city and my home, and the real danger of my life—which was my own heart and the damage I was walking around with, unknowingly.

Bill: Your heart plays a large role in the book, both figurative and actual. Did your heart operation change the way you see the world? The way you see yourself? The way you gauge the human condition?

Jeff: We talked once, I remember, before my surgery, and you said that heart problems are very emoitional in a way that other physical problems aren’t. And I think that’s right. I mean, our hearts are so protected, there, right there, behind that thick wall of bone in pretty much the center of our bodies. To have that cover removed and allow someone into the center of your self is a terrifying feeling. Metaphorically of course, but also in this case very physically. There was a part of me that seriously thought I wasn’t going to wake up from the surgery. The rational part of me understood the odds. It knew the surgeon was very skilled. It knew that the surgery is not as dangerous, really, as driving down to the hospital itself. But, still, it had to drag that scared, weepy part of me down to Boston and to the hospital.

So, yes, it did change the way I see myself. There’s obviously this very real fragility to our daily, walking-around selves that I am conscious of, but at the same time there is a tremendous resiliency in us. In these remarkable machines we live inside and inhabit. And I think that you have to see both those traits at once if you want to see us clearly as a species. We are tough and frail at the same time, robust and brittle. Our own negative capability, if you will. I’m trying to make this not into a cliché—young poet becomes aware of his own mortality, right?—but it is a little bit cliché and I am becoming ok with that. Maybe that’s part of the process too. Accepting one role in a larger, repeating story.

Bill: You’re well known and successful as a poet–why the memoir at this time? Does your poetry inform your approach to memoir?

Jeff: It is all our friend Wes McNair’s fault. He and I were sitting drinking whiskey and eating peanuts at his camp one summer—maybe six years ago now—and he was talking about his memoir and told me that the next step for me was a book of prose—essays or memoir. And I resisted that idea. Immediately, and then for a while afterward. But after a few months of holding that idea in my head, and after I allowed the reality of it to sink in, I realized I was resisting out of fear. I was scared of the scale. I was scared of the challenge. So I took a few essays I had written already, mostly about landscape, and started to develop and re-write and expand them.

Jeff: It is all our friend Wes McNair’s fault. He and I were sitting drinking whiskey and eating peanuts at his camp one summer—maybe six years ago now—and he was talking about his memoir and told me that the next step for me was a book of prose—essays or memoir. And I resisted that idea. Immediately, and then for a while afterward. But after a few months of holding that idea in my head, and after I allowed the reality of it to sink in, I realized I was resisting out of fear. I was scared of the scale. I was scared of the challenge. So I took a few essays I had written already, mostly about landscape, and started to develop and re-write and expand them.

Then, I started to write the first of many, many drafts of this project. It was a long time coming into being and that’s in some way because of poetry. Honestly, at first the book was more like a long prose poem—fragmented and lyric—far more so than it is, even now. And the work of writing it and shaping it into a readable and honest memoir became—really—a process of learning how to write prose well. How to write scene and define character, how to keep the reader in the moment and stay out of my own head (I don’t entirely succeed in that, I know). But that process was incredibly rich for me and fulfilling. I imagine it is something like learning a new instrument when you already play music. New possibilities in tone and sound and timbre.

Bill: How did you handle the question of others in your memoir? Have you had any reaction from people in your life that you’ve turned into characters here? Were there any portraits that worried you as the book became public?

Jeff: I haven’t had any reaction, yet. I changed a few names to protect people’s identities, but other than that, no. I think the only person in the book who might have cause to complain about his portrayal is me. I try to hold myself up for a close inspection, and in some cases I end up looking pretty silly. But that’s ok, I think, I was a pretty silly young man.

Bill: What’s your best writing day like? What’s a real writing day like?

Jeff: My best day is when the words come like water and flow unimpeded and hours go by like minutes because I am in the world that I am writing so fully that it seems to be the real world and our day-to-day world is only a dream. But that doesn’t happen every time. It doesn’t even happen most days. Most days I put some words down and sit back and look and try to see what it is I am doing with them. And then repeat. Slowly. So slowly. Word by word, paragraph by paragraph. Like building a very deliberate wall out of very heavy bricks. Or I go back into something I have already written—revision is so much more enjoyable for me, now—and try to find the gaps or the places where I need more depth or where I am vague and unclear. This is part of the process, too, learning to read myself with the eyes of others and not assume anything on the part of the reader. To try and be willing to see my words in her eyes and understand what I need to do to evoke the emotion I am working towards in her.

Bill: What are you working on now?

Jeff: I am working on a novel called Self Portrait in Nine Generations. It’s a historical story told in alternating, personal voices and historical whispers based around my ancestors’ experience leaving Scotland and Ireland and advancing into this novel concept called America. This story is fiction, but based on the real lives of two of my people, Anne and William Thomson, who emigrated from Scotland to the colonies by way of Northern Ireland. I spent a time in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and at a library at Brown University doing tons of background research. I have finished a second draft. The end of the year was the deadline I gave myself—and now I’m going to show it to a few people and get some feedback and see if it is worth anything at all.

Bill: Surely it is! Poetry, translation, nonfiction, and now fiction. You’ve reached home base. Could you talk about the differences and similarities among the forms as you approach them? What comes easy? What’s difficult? What’s impossible.

[A blue morpho butterfly floats past. We sip our margaritas]

[A blue morpho butterfly floats past. We sip our margaritas]

Jeff: I don’t know if I am on home base yet. Maybe if the novel really turns into something. Poetry has always been my first love and comes the easiest. I trust myself and understand—sometimes, most of the time—the moves I am making and why. It’s about crossing the gap between what cannot be said and what needs to be said. Getting to that charged place of ruin we all carry within us. There’s an electricity to it when it feels right. And translation is another form of that. Taking someone else’s finished words and trying to find their equal in English. It’s a bit more like working out a complicated puzzle, but it’s also pretty thrilling when I get it right.

Prose, as I said, is different. Poetry is compact. It demands intensity. Prose takes more patience. Things unfold slowly—both in terms of the length but also the very idea of the paragraph and the narrative arc. I wrote prose before the memoir, obviously, but it was analytical and scholarly, or rhetorical. It wasn’t artistic prose, which follows different rules and demands a different approach. A different kind of eye. Writing fragile taught me a lot about working in this kind of prose and I was able to translate those skills—luckily—into the novel. I don’t think I could have finished a first draft of a novel without having gone through that very steep learning curve that I encountered writing the memoir.

Bill: What other arts and activities inform your vision?

Jeff: Music and visual art are really important for me—especially in my poetry—I try to bring them into the world of the poem on a regular basis. The sound of word and the power of the visual image feel equally necessary for me in my work, and those qualities that I find in visual arts and music translate most fully into my poems—poetry has more elasticity to take other media into its realm.

The physicality of the natural world is important, too. Being out in it. Traveling. Thinking about the vast layering of history and myth and story that lives in inside and below our consciousness. I think in my prose I am really invested in evoking place and landscape and the feel of the physical world. Not just the surface sense of things, but some deep and essential there-ness about the world and what we make of its particulars. And those particulars and both human and non, geographic and historic. There is so much there there, and finding it and bringing it into the mind of the reader is a pretty remarkable and lucky way to spend a life.

Bill: Is that an anteater?

Jeff: That’s an anteater.

January 18, 2016

Table for Two: An Interview with Julianna Baggott

You’ve never heard of Harriet Wolf, one of the 20th Century’s great American writers. But don’t feel too bad — neither had an unnamed faculty member in the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program.

“I gave a reading at VCFA to a bunch of writers,” says Julianna Baggott, whose novel, Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, imagines the existence of a seventh book in the Wolf oeuvre, a memoir that exposes the “true stories” behind Wolf’s six other classics. “And a couple of writers, well-known writers, came up to me afterwards, and said, ‘you know, I’m really not familiar with Harriet Wolf’s work.’

“And I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t think I made that clear — she doesn’t exist.’ So, then I thought, well, let’s not make that clear, let’s build a little bit of her lore…”

Part of building lore included a website for the “Harriet Wolf Society,” comprising academics and others devoted to the study of Wolf’s six novels, a series of books that follow the characters Daisy and Weldon from childhood to death. The genres age with the characters from children’s novel to magic realism to realism to apocalyptic dystopia to a meta-fiction.

Part of building lore included a website for the “Harriet Wolf Society,” comprising academics and others devoted to the study of Wolf’s six novels, a series of books that follow the characters Daisy and Weldon from childhood to death. The genres age with the characters from children’s novel to magic realism to realism to apocalyptic dystopia to a meta-fiction.

In Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, we follow four different narrators: Harriet herself, as she presented herself in her until-now “lost” seventh book, a memoir detailing the real-life love story behind her successful series; Harriet’s lone daughter — Eleanor — who hated the books that, she intuited, kept her from ever knowing her father and gave the world a claim on her mother; Eleanor’s two daughters, the rebellious Ruth and the sheltered Tilton.

Though it centers on a reclusive Great American Writer and her descendents, none of whom exist, the book is full of real-life places and incidents from the Maryland School for the Feeble-Minded (where Harriet spent a big chunk of her childhood) to a plane crash on the Eastern Shore of Maryland (which precipitates the abandonment of Eleanor and her daughters by their husband and father).

This all sounds exceedingly complicated, but Baggott builds a complicated world full of convincing coincidence and conflicts. In The New York Times Book Review, Dominique Browning called the book “a post-and-beam structure, a framework of sturdy supports locked into place with no nails, just fine, firm dovetail joints.”

That sturdy structure is doubtless one of the reasons Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders was named to the Book Review’s list of 100 Notable Books for 2015.

A novelist, essayist, and poet, Julianna Baggott has written 18 novels under her own name as well as the pen names N.E. Bode and Bridget Asher. She has published volumes of poetry and work for young adults. She’s so prolific that it seemed imperative to ask about the time it took her to write the intricate and affecting Harriet Wolf.

Sebastian Stockman: You say in the acknowledgments that you worked on this novel for 18 years, and that it went through lots of different drafts. Is the gestation period always that long for your books? What made this one more difficult, or what made it take so long?

Julianna Baggott: I’d published my first three novels, literary novels, under my own name. And as The Madam was coming out, things were going badly for that book, and … really I thought it was probably the best of the novels that I’d written. But honestly I think what happened was I just got kicked off my game as that book was coming out, and not only kind of lost confidence in myself as a writer — actually, I don’t know that I lost confidence in myself as a writer of literary novels, I lost heart, I suppose.

And, I needed to keep writing, because I’m a writer and it’s how I process the world. It’s how I breathe. And so, from there on out I really tried to create all these different ways to not put myself out, and not put my most literary ambitions out into the world.

SS: Oh wow. That’s really interesting.

JB: Yeah, so I mean, I might have already been writing for kids by that point, but N.E. Bode existed by that point. Bridget Asher was born shortly thereafter. I would collaborate with others. Honestly … the Pure Trilogy ended up literary and had good critical success, but that was for me definitely another way to disguise myself to myself. That was me writing what I thought was a thriller. I think it ended up to be a poetic thriller, or something.

But, I really had an incredibly specific kind of writer’s block. I couldn’t come to do the job that I really thought I was meant to do. … But, I found all these other ways to continue to write.

SS: In any case, it sounds like you put Harriet Wolf aside for quite awhile.

JB: Yeah, well, I would come back to it, and every time I came back to it, I would fall into it, but I was a slightly different writer.

You know I would come back to it, and it was Eppitt’s story for a long time, and I actually had the beginning of the novel published in 2001 from his perspective.

I would come back to it in all these different forms and all these different ways. And every time I came back I would figure out a new way in, and I would bring with me my slightly different ambitions with language, and my slightly different obsessions and what was important to me. And then I would walk away from it because I would say ‘well, I don’t actually want to publish this.’ ….

So I would write something else — happily so … . Writing those other novels taught me an incredible amount. I love those novels. I stand by them.

But then I would come back, and I would come back again. And once I came back I was collaborating not with just my initial attempt at the novel, I was collaborating with the person who came before me — who was me but a different version of me. And it just got more and more layered. And then of course it kind of became too big in my head to tackle.

I’d written a screenplay, actually, that’s kind of the present day — not present day, but set in 2000 — from Tilton’s perspective. And at that point Tilton was a male character. Then I kind of figured out that piece of it, that the historical novel was set against this present-day narrative. And then I figured out that they were all women. Then, I eventually just sat down and wrote it.

It’s funny because people have been writing to me saying “it’s such a relief to hear it took you 18 years.” And I say, “No no no no no no no, you misunderstand. Do not — this is not a good way to write a novel. There’s nothing to learn here, look away.”

SS:

Although, I would say, I think the layering effect you talk about shows up in these Rashomon-like versions of the same events from various perspectives.

But it’s not — it feels so organic, I guess is the word I’m going to use even though I wanted something better.

We get these certain concordances where it all feels really natural. One of the things that struck me was between Chapters 9 and 10 when Harriet is going home. The young Harriet is leaving the Home for the Feeble-Minded, and chapter 10 starts with Ruth, Harriet’s granddaughter, arriving decades later, at that same house, after years of her own estrangement from her family.

Things like this made the coincidences feel right without feeling overdetermined.

JB:

I don’t think I understood that the house was a character until long after. … In my head it wasn’t until I rewrote the book that I really thought ‘this is the same house. … You have to make this the same house.’

There’s this Tom Stoppard play called “Arcadia” which ends with multiple time periods, and the actors are all on stage at the same time. There’s one present-day narrative and one past narrative.

And the actors being on stage through time and at the same time was so resonant with me. And by the end of the final draft I really did want the reader to feel that things were happening at the house almost at the same time, even though they were in different time periods. I wanted you to feel this character moving through this room even though it was many many years before this [other] character was sitting at the dining room table that [the first character] is passing.

SS: The house is almost a member of the family.

JB: Well, it has an umbilical cord. It squats over them like a bird in a dream that one of them remembers the other one had. It has a lung. It is very alive.

SS: The other thing I love about this book are its convincingly complicated family relations. When each woman in turn becomes a mother, Harriet and then Eleanor and then Ruthie, it’s almost as though they’re fighting the last war in some way, you know?

It’s about the ways our parents mess us up despite the best of intentions. Or — no matter their intentions, there are always unintended consequences.

JB: And that sometimes your parents are in an argument with their parents. And sometimes you’re arguing with them in daily life, ‘I’m going to parent in contrast to you.’

SS: There’s also the way Eleanor fails to protect Ruthie, her older daughter, and then overcompensates with her younger daughter, Tilton. This is what I mean about the structure’s seeming so natural without being forced. Eleanor overparents Tilton, and that gives Harriet and Tilton something in common because they were both overly-sheltered people.

And what about this photo in the frontispiece? It’s captioned “Harriet Wolf with the man presumed to be Eppitt Clapp. (date unkown).

JB: My daughter, my 20-year-old … went back to my parents’ house and spent a month one summer scanning old photographs; she’s an artist.

And so when she came back she had these photos all scanned, and I saw this photo, there were a couple of them, and they’d say “Ruth and Rosebud.” Who the hell is Rosebud?

Ruth, I figured out, was my Aunt Ruth, who never had children and whose sofa we were probably sitting on when we were looking at the photographs. But I was like ‘Damn… Rosebud is fine.” Who the hell is he?

I asked my mom, and she said, ‘That’s your Uncle Jesse.’ Ruth and Jesse married. I only knew Rosebud, my Uncle Jesse, as an old man, not as … this gorgeous gangster.

SS: And the decision to use it in the book? It really does the job of smudging that line between fact and fiction, because that photo and I knew you’d done a bunch of research, and I thought “Wait, these people she definitely made up. I know this.”

But it put this little seed of ‘I’m not sure’ in the back of my head. Like, ‘is there a Harriet Wolf?’

JB: Right as the book was going to press I sent this photograph to my editor and I said this is the photo we’re going to put on the [Harriet Wolf Society] website — you know, a “found” photo of Harriet and possibly Eppitt, we’re not sure who this guy is — and he’s like ‘Let’s put it in the book.’ So we put it in the book

SS: Well, yeah, I think it totally works, because it did throw me.

Also, it made me wonder, this photo is something your daughter found after you were well on your way to finishing. But you made up another artifact we don’t see, but that Harriet describes — one photograph of her family.

But I’m also wondering: because you did research, and because this book was with you for so long, were there any sort of artifacts or talismans that you used or carried with you to help orient you to the world of the book?

JB: Yeah, there is a big fat envelope. And we’ve moved six or seven times in the last 10 years …

SS: That’s not fun!

JB: It’s not fun. But I’ve kept this — Eppitt was the name of the book, and it has “Eppitt” written on it. Inside there’s a plane crash article … and just a number of different artifacts. One is that 1911 biennial report which I had gotten a copy of when I went and visited [The Maryland School for the Feeble-Minded].

I had that for so long. As soon as this book was coming out we moved again last October, and that’s the one envelope I can’t find. The universe sucked it up.

But there’s one photo [Harriet] talks about, of the children on the lawn, and she feels like that’s her. There are pictures in that 1911 report, of children working and children in classrooms weaving. So that might actually be a photograph, the one of children running on the lawn. It’s so vivid to me, it might actually be a real photograph.

SS: In Harriet Wolf you’ve created this fixture in American letters, sort of a J.D. Salinger-type, or maybe Fitzgerald, somebody who had an influence on generations of schoolkids or generations of readers.

And, while we get some plot summaries, we don’t see much of her own words. Because you went through so many drafts, how much of Harriet Wolf’s oeuvre did you write, or did you just sketch out plots?

It seems like there’s a tricky thing there, right, of telling the reader this is a classic of American literature and —without seeing much of the prose — we sort of have to take the author’s word for it.

JB: Right, and in the previous draft, before Ben edited it, there was much more. He wanted me to cut. My first job was just to cut 9,000 words. But even then, he felt like less was more in terms of the books behind this book. So I knew that I was going to have to trim those back, but previously there was much more of them.

I can’t say that I know the plots; it’s not that I plotted them. It’s much more like I imagined things.

SS: The arc. We don’t get plots, I guess, but we get the flavor of each book, as the series moves through genres and sort of grows up with the American reader. It grows up with the 20th Century, almost.

JB: Right.

SS: When you did write more of the Harriet Wolf stuff, was that also pressure, or was it more like donning one of your pseudonyms?

Because obviously we don’t sit down and consciously try to write a classic of American literature unless you have a character who has written one.

JB: Right, The last book is memoir, so she’s in a different genre again. The final genre is memoir.

I think that my main thing was just to have the images sustained for the reader. And also there’s a line that goes throughout the whole thing, her most famous line, and you figure out who said that line in real life and what it meant to her in the moment.

SS: Some of her secrets are revealed, in a way…

JB: And I think that’s one of my kind of great sadnesses as a writer. … I don’t get to tell you guys where the great lines come from.

My own life, I’m never going to share with the reader. I’m not. I’m never going to write memoir. I mean if I could barely write this, I’m certainly not going to have the courage — I can barely hand myself over as an author; I’m certainly not going to be able to hand myself over as a human being —

And so, you know, there are so many times when it’s really like this incredible love affair that I have with my husband, this incredible life that I have with four kids that’s just like, amazing and hard and I love them so much and

SS: Did I lose you?

JB: No, …

SS: [belatedly and thickheadedly realizes she is crying] Oh, goodness, I’m sorry, take your time. Take your time, I’m sorry.

JB: Anyway, it’s just a privilege to be alive.

ME: Yeah, absolutely. Gosh.

JB: And I never get to… I never get to share that part, you know? And so in some ways, I am a liar. You know, as a writer.

And I’m not courageous. So, in some ways I’d love to hand over some secret book of the truth of how messed up and painful and incredibly gorgeous and heartbreaking my own life is. But I never will and so I guess maybe that’s the main wish fulfillment of this book.

In other interviews I’ve said that the wish fulfillment of this book is that she gets to be a hermit. God, I’d love to be a hermit. I’d love to make enough royalties to be a hermit. But in fact maybe the real wish fulfillment is that she got to be honest.

As a fiction writer I’ll never be that honest. Maybe to my kids or whatever. But each book I write, in almost every line, every place on every page, I write from memory.

So every. single. thing — is my life. It’s what happened that day, what happened that morning, y’know? It’s me as a child; it’s my mother. It’s my own daughter. It’s just such a strange—I guess that is the wish fulfillment — that I will never be able to express that to readers, to explain how intimate we’ve been.

We’ve been intimate for all these books and all these pages. And they’ll only think I made it up.

SS: You have those hints through Harriet: “I would like to say that I made up all of the books, invented everything. But really I’m more like the addled priest who wakes up each morning and picks up his wicker basket to fill with every dirty thing he finds and then spends his nights hunched over polishing buttons and spoons.”

I thought that was a beautiful image of fiction-writing. It made me think of something the poet Kay Ryan said how she spends her days gathering string.

JB: That works. I mean this book is about a knot.

ME: I was trying to avoid that hacky interviewer question of “how much of this book is you?” But really I like that notion of Harriet’s manuscript as wish fulfillment. So, Eleanor hates fiction, or maybe that’s too harsh?

JB: No, I think she hates fiction.

SS: So Harriet loves fiction because it’s her chance to sort of fix the world she’s been handed. But for Eleanor fiction is what’s keeping her father from her, in some ways?

JB: She hates fiction like one might hate a stepfather because he takes up so much time and attention, and because he’s not the truth.

SS: And is there — since we’re on this idea of taking things from your own life — is that a sort of not wish fulfillment, but is Eleanor saying something there that you sometimes maybe want to say, too?

JB: Oh, my feelings about fiction, or about my father? I have this incredibly lovely father.

But yeah, about fiction, I hate it, too. I got to say a lot of things that I wanted to say about writing. The first version was much harsher, much harsher. And that was another thing, Ben was like ‘maybe you shouldn’t quite hate the reader so much’?

But I think that I’m a writer who very much loves the reader. And I dote on them and I think about them and I adore them. It’s definitely my worst flaw as a writer: I completely over-love the reader.

SS: Why is that necessarily a flaw?

JB: I don’t know — where do their desires start and where do they end? And where do my instincts and desires start and end? And do I sometimes discount my needs as a storyteller and my stylistic needs…?

And sometimes I write a draft for me and say “OK, that was for me, now actually translate it for the reader.” …

That overlove — they [the readers] have too much of my attention sometimes. I bow to them instead of what might be to my needs. … Steven Spielberg talks about this: “My early films are all about my relationship to the person seeing them.”

He’ll never give up on the viewer. He’ll always overlove the person who’s watching his films. In writing my goal is to try to find ways to be of service to my characters … and those are the best writing days, when they take charge. And sometimes the reader is not the best person to be bowing to.

Definitely I have a love relationship to the reader and I certainly think about them, but also there’s the counterpoint to that. My relationship to the reader is not an easy one. I don’t know what book they’re reading.

If this is a collaboration… the St. Louis Arch was off by a few inches when they built it. I’m building the St. Louis Arch, hoping to meet them perfectly. There’s no way our arches can meet in the middle.

That’s a very, very strange collaboration. And also, because I’m a writer, I’m someone who is the composer who never hears the audience clap. They’re just not there. There is no audience. I write in a vacuum. It’s a strange thing to think so much about someone who is so imagined.

SS: They’re not there and you love them too much.

JB: Right. Exactly. That seems doomed!

Sebastian Stockman is a Lecturer in English at Northeastern University. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he’s at work on a memoir.

January 5, 2016

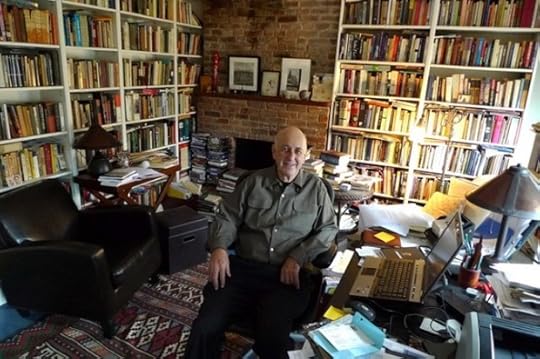

Table for Two–An Interview with Philip Lopate

GLANCING BACK

Your essay, The Poetry Years (from Portrait Inside My Head) looks back at where and how you started writing professionally. You say you had no ambitions toward writing poetry until you were a student at Columbia and suddenly doing it, kind of by accident. What experiences drew you in?

PHILLIP: When I was an undergraduate at Columbia, my writer-friends were mostly poets. A few fiction writers, not a single nonfiction writer in the batch. Monkey see, monkey do: I started reading and writing poetry.

You carried with you a creeping sense of insecurity about your ability as a poet, yet that community was receiving you, and you were publishing your writing. During this period, did you ever face any feelings of severe doubt or despair over your ability or progress as an artist, or was it mostly clear to you that you had enough talent and a momentum within the literary world, and you would find your way?

PHILLIP: I was in doubt from the first that I had enough talent or enough to say to be a successful writer, but I figured what the hell, let’s give it a shot. I did not despair, but neither did I think when I was starting out in my twenties that I would ever be as successful as I have become. What made me stay the course was finally a propensity to generate questions and try to come up with answers–experimentation, rather than certainty.

THE INTERIOR

What is your overall agenda or literary aim as an essayist?

PHILLIP: My literary aim as an essayist is to champion the form and extend the conversation that so many great, dead essayists who preceded me have started. I want to please the dead, as well as living readers.

I love your piece, Howl and Me—in which you discuss the complicated ways as a young man you were considering your own position in the world. You had deep-seated yearnings for success. Established writers often tell new writers that publishing doesn’t matter. But isn’t it more complex than that?

PHILLIP: Of course publishing matters, because the world’s approval of you is finally one of the ways that you can convince yourself that you are not merely a bluff artist but, possibly, just possibly, a writer. Plus it may help to pay the rent along the way.

As one who has made the study of the literary essay, the practice of it, the teaching of it his life’s work, do you ever question its evolving form? Are there any rules to insist on?

PHILLIP: The essay today is going through many mutations, as it borrows from other literary forms, such as poetry (lyric essay), fiction (the short storyish essay, like Joanne Beard’s Fourth State of Matter), comix (the graphic essay), cinema (the essay film), the mosaic essay, the appropriation piece. Anything goes, and should go, as long as the results are stimulating and well done.

AT THE WORKSHOP

You recently led a Creative Nonfiction workshop at The Lighthouse in Denver. Someone asked how to get her writing to transform into something beyond plain words and sentences on the page? Since the question garnered so much participation, anguish, and mental sweat, I thought it was worth revisiting. Will you speak on what is involved in getting down the sort of writing that hits a deeper mark?

PHILLIP: Good writing has intriguing linguistic texture (wide vocabulary, complex syntax, syncopated rhythm) and density of thought. It also seeks the deepest, wisest, most honest formulations.

After the workshop I was waiting outside for my ride, and having just purchased your craft book, To Show and To Tell, I opened it and read this first sentence: “I should explain straight out that I consider myself to be as much a teacher as a writer.” What do you value about teaching—and, noting the slight confession in your sentence, what accounts for the impulse to explain?

PHILLIP: Teaching can be a lot like writing. When I am “explaining” something in the classroom, I listen to my thoughts the same way I would when I am alone at my desk. I like the improvisatory jazz possibilities of teaching. Something comes up and provides the opportunity for a spark of humor. The comic helps loosen the mood of the classroom, especially in graduate programs, which can be so dour.

POLITICAL MATTERS

Along with your ventures into the personal, you take your writing to the political, cultural, and social. You’ve written that you have had the occasional change of heart over some of your former views. In what ways has your political perspective evolved over the years?

PHILLIP: I’m not sure my political perspective has evolved that much over the years. I was always on the left, always a skeptic. The difference is that now I am less inclined to mimic group-speech and more apt to ask myself: Do I really believe this or that? Also, I have been forced to become more pessimistic in the face of the Republican Party’s increasing lunacy.

There seems to be a good deal of discontent on college campuses these days. In one example, student activists at various schools have been demanding the silencing of any speech that might be considered hurtful to others. We used to call this censorship, and most of us opposed it. Is there now a difference? What do you think about this idea of regulating language to the degree that opposing viewpoints are not to be expressed?

PHILLIP: I am not on the side of censoring speech, or renaming dormitories because John Calhoun or Jeffrey Amherst or Woodrow Wilson turned out to have done some bad stuff. I think history should be respected, not suppressed. I don’t mean we need to revere racists or bad guys, just recognize that they had an historical impact. Also, I wish that students would be less inclined to expend their energies of this whitewashing of vocabularies and symbols, and more inclined to protest for a more equitable economy, full employment, affordable housing, health care for all.

Phillip Lopate lives in Brooklyn, New York and teaches at Columbia University where he is also the director of the graduate nonfiction program. He has written 3 books of poetry, 2 novels, 3 personal essay collections and much more

His most recent books include: To Show and To Tell, The Craft of Literary Nonfiction and Portrait Inside My Head, Essays.

January 1, 2016

Tree Hugger Dave on Nat Geo’s Born to be Wild

I have often been accused of being a tree hugger. Well, here is the proof. On Sunday January 10 at 8 pm I will be hosting an episode of National Geographic’s Explorer series called “Born to be Wild.” Check out this clip and the links below. (Quite proud of myself for figuring out how to embed these. Hadley would be proud of me too even though this whole show is about trying get her off screens–though,as she likes to point out, you need a screen to watch it.)

A couple of pics from the show:

And a couple links if the last two embeds don’t work:

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com...

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com...

December 23, 2015

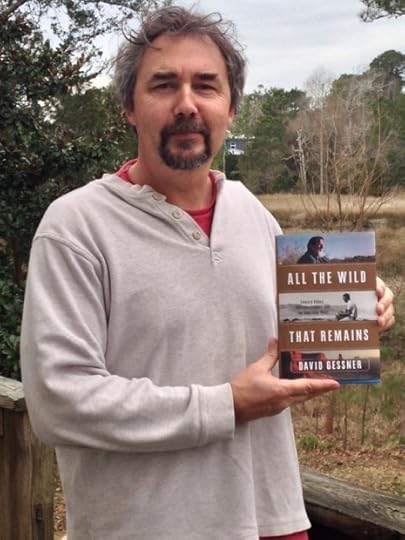

All the Wild That Remains: A Year End Report

Here is a wrap up of some of the stuff that has happened with All the Wild That Remains since its release in April.

Here is a wrap up of some of the stuff that has happened with All the Wild That Remains since its release in April.

The downside? No New York Times review. But considering how the NYTBR treated Abbey and especially Stegner, I suppose that is not a huge shock. Despite the fact that the Washington Post ended their review “Perhaps now even Easterners will take notice,” that has not always happened.

The upside? Pretty much everything else…..

All the Wild That Remains:

Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West

By David Gessner

A New York Times Bestseller

An Amazon Best Nonfiction Book of 2015

A Kirkus Best Book of 2015 and Best Book about Significant Figures in the Arts and Humanities

A Christian Science Monitor’s Top Ten Nonfiction Book of the Year

A Southwest Book of the Year

A Smithsonian Best History Book

To the Best of Our Knowledge Top Ten Book

“If Stegner and Abbey are like rivers, then Gessner is the smart, funny, well-informed river guide who can tell a good story and interpret what you’re seeing.” The Los Angeles Review of Books.

As western rivers dry up and western land cracks from aridity, the voices of Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey have never been more important. Those voices can be heard, loud and clear, in All the Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West. The book takes the long view of the land, and of the importance of having deep conversations with our literary ancestors, and speaks to the crisis of climate and drought that is occurring right now. Stegner and Abbey put what is happening in historical perspective, but they were not detached scholars who sat back in a crisis. They both acted. They understood the land the land they loved, sure, but also fought for it. And of course they also wrote beautifully about it.

Some nice things people have said about:

ALL THE WILD THAT REMAINS

W.W. Norton 2015

““David Gessner has been a font of creativity ever since the 1980s, when he published provocative political cartoons in that famous campus magazine, the Harvard Crimson. These days he’s a naturalist, a professor and a master of the art of telling humorous and thought-provoking narratives about unusual people in out-of-the way-places. To his highly original body of work, he brings a sense of awe for the untamed universe and a profound appreciation for the raucous literature of the West. “All the Wild That Remains” ought to be devoured by everyone who cares about the Earth and its future. “For me there is no wild life without a moral life,” Gessner writes with all the force that Henry David Thoreau might have expressed. All the Wild That Remains” offers a contemporary call of the wild that resonates loudly and clearly from one coast to the other ” —The San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/books/article/All-the-Wild-That-Remains-by-David-Gessner-6305677.php

“As I was reading “All the Wild That Remains,” I found myself wondering if Gessner too had not written a book that would make people act. And I wondered how this so-called biography could deliver such an emotional punch. I was expecting to be educated, but not inspired, not for the raw spirit of these two men to rise from the language into my consciousness….The loose but artful weave of the two narratives gives the book a rare creative tension. But it is deepened by a third narrative line, that of Gessner himself, the first-person storyteller, whose honest voice is full of insight and humor.”—The Chicago Tribune http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/books/ct-prj-all-the-wild-that-remains-20150514-story.html

“These two men are the contrasting heroes of a profoundly relevant and readable new book by David Gessner: All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. In this artful combination of nature writing, biography, literary criticism, and cultural history, Gessner studies two fascinating characters who fought through prose and politics to defend the fragile ecologies and transcendent beauties of the West.” —The Christian Science Monitor (The CSM picked All the Wild as their number one book of April.)

Gessner’s book serves as an excellent primer to readers new to Abbey and Stegner, and an insightful explanation of their continuing relevance. Gessner, an important nature writer and editor in his own right, also uses the writers’ lives as a template for his exploration of the Western landscape they lived in and wrote about. He visits places that were important to Abbey and Stegner, and draws trenchant conclusions about the current state of affairs in a region still battling over how to best protect and exploit its fragile resources.

Gessner’s reporting, whether profiling Stegner and Abbey’s acolyte Wendell Berry or observing the consequences of Vernal, Utah’s fracking boom, is vivid and personable. In his able hands, Abbey and Stegner’s legacy is refreshed for a new generation of readers. Perhaps now even the Easterners will take notice. The Washington Post http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/westerners-with-sharp-pens/2015/05/21/3b4193e2-e1fe-11e4-b510-962fcfabc310_story.html

“If Stegner and Abbey are like rivers, then Gessner is the smart, funny, well-informed river guide who can tell a good story and interpret what you’re seeing.” Justin Wadland The Los Angeles Review of Books:

http://lareviewofbooks.org/review/which-one-was-truly-radical

“[Gessner] never reduces either man to simplistic categories, but sees in both personalities possible life models.” –David Mason, Wall Street Journal http://www.wsj.com/articles/book-review-all-the-wild-that-remains-by-david-gessner-finding-abbey-by-sean-prentiss-1430515926

“They are legends, Abbey and Stegner, and bringing them together in a book like this, in the manner chosen by Gessner, was a stroke of genius. If you know and love the work of these two authors, read All the Wild That Remains and then re-read at least parts of Abbey and Stegner. If not, read Abbey and Stegner first, at least one book by each man, and then read All the Wild That Remains.” Dallas Morning News. http://www.dallasnews.com/lifestyles/books/20150417-review-all-the-wild-that-remains-edward-abbey-wallace-stegner-and-the-american-west-by-david-gessner.ece

Gessner’s wacky sense of humor and rigorous mind, his delight in, as he calls it, “an antidote to the virtual age,” and, especially, “the lost art of lounging” — have never been more evident than in his beautifully conceived new book, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. This timely mash-up of environmental journalism, biography, travel writing, and literary criticism has Gessner hitting the road in search of the real story behind “two of the most effective environmental fighters of the 20th century.”

What emerges is a joyful adventure in geography and in reading — and in coming to terms with how the domestic and the wild can co-exist over time.

Joy Horowitz The Los Angeles Review of Books http://lareviewofbooks.org/review/wild-literary-geographies-david-gessner

“These revelations, and Gessner’s subtle humor, make for an absorbing read. Abbey’s and Stegner’s lives, Gessner says, ‘are creative possibilities for living a life both good and wild.’ That’s something that many in the West still seek–and what makes this book such a great read for anyone living there.”—Outside Magazine http://www.outsideonline.com/1962281/new-reads-following-two-iconic-authors-west

“All the Wild That Remains” is a cut above all those “in search of” books. David Gessner not only walks the walk but seeks out those who knew the two icons. He gives an insightful comparison of the two and applies their ideas to today’s environmental problems.–Sandra Dallas The Denver Post http://www.denverpost.com/books/ci_28341164/non-fiction-works-reviewed-by-sandra-dallas-highlight

[All the Wild That Remains is] an incredibly enjoyable read. You’ll feel like a co-conspirator on a great road trip through the West with not two, but three, great nature writers, sitting in the back seat, reveling in their stories….f Gessner isn’t careful, one of these days he might just find himself in the same pantheon as Stegner, Abbey, Barry Lopez, Berry, Williams and our other invaluable chroniclers and seers of the West.”–Clay Evans, The Boulder Daily Camera

“Gessner writes with a vividness that brings the serious ecological issues and the beauty of the land into to sharp relief. This urgent and engrossing work of journalism is sure to raise ecological awareness and steer readers to books by the authors whom it references.”—Publishers’ Weekly. Starred Review. Here’s the full review: http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-393-08999-8

“Stegner and Abbey ‘are two who have lighted my way,’ nature writer Wendell Berry admitted. They have lighted the way for Gessner, as well, as he conveys in this graceful, insightful homage to their work and to the region they loved.”—Kirkus Review. Starred Review.

“This engaging book provides an intimate look at Edward Abbey (1927–89) and Wallace Stegner (1909–93), two of America’s finest authors, both of whom chafed at being pigeonholed as regional writers. Certainly their fond, passionate focus was the American West, but there is much universality in their concerns. Gessner (Return of the Osprey) traveled to places they haunted, read all he could of their writings, and spoke with people who knew them well. His smooth, literate text is enhanced by photographs of Stegner and Abbey as well as chapter notes that read well. Stegner authored 46 works, including 13 novels, and won a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Abbey wrote 28 books, was a Fulbright Scholar at Edinburgh University, and may be best known for his book Desert Solitaire, which is often said to be as worthy as Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. Stegner, clean cut, traditional, with a PhD, and Abbey, an uncompromising anarchist and atheist with a 1960s-ish appearance and lifestyle, provide rich grist for Gessner’s mill, which he fully exploits for the benefit of any reader. Gessner himself has penned nine books. All three authors qualify as important environmentalists and writers. VERDICT Highly recommended for everyone interested in literature, environmentalism, and the American West.”—Library Journal

ATWTR is now an editor’s pick at Amazon and a staff pick at Powell’s where Shawn writes: “All the Wild That Remains is a fascinating portrait of the American West told through the lives of two of its most famous writers, Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner. This book champions their unique styles and will make you want to read (or reread) all of their work. It will also inspire you to get your car and head out on an extended road trip through this beautiful western landscape.”

“Two extraordinary men, and one remarkable book. To understand how we understand the natural world, you need to read this book.” –Bill McKibben, author of Eaarth

“An excellent study of two difficult men.”

— Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove and The Last Kind Words Saloon

“A travel book, yes, a literary memoir, yes, and a profound meditation on our myths and shadows. Anyone who loves the American west will be enraptured by this book. It is a wonderful piece of work.”

— Luis Alberto Urrea, author of The Hummingbird’s Daughter and Queen of America

“This book rubs Abbey and Stegner’s history in the dust and sand so beloved to them, posing these two late icons among voices, landscapes, and arguments that endure in western wilderness, deftly creating a larger geographic chronicle.” — Craig Childs, author of House of Rain and

“Praise David Gessner for reminding us that the words of our two most venerated literary grandfathers of the American West, to remind us of our wilder longings, to incite in us a fury, that we might act–even now–to defend all the wild that remains.” — Pam Houston, author of Cowboys are My Weakness and Contents May Have Shifted

“To understand the truth of the Desert West, read Stegner. To understand one writer’s emotional response to that desert and to our thoughtless destruction of wilderness, read Abbey. To understand the two writers as men of their times—and ours—read Gessner: for his honesty, compassion, humility, scholarship, and sensibility.”––Stephen Trimble, author of Bargaining for Eden

December 18, 2015

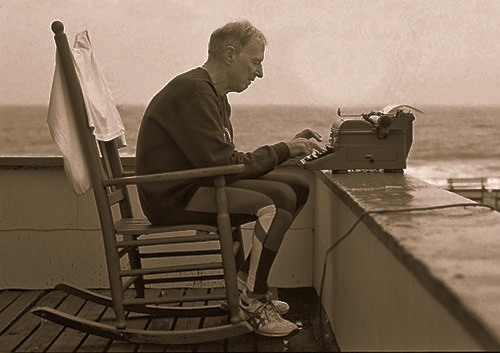

George Sheehan on Being a Writer-Athlete

As a teacher, my reading is circumscribed during the parts of the year I call “terms,” restricted for the most part to the books I’ve assigned and the writing of my students. For the most part. The exception comes during the hour or two I spend in my writing shack each night around cocktail hour, a period of time during which I read whatever the hell I want. Often, as I’ve described in here before, I jump from book to book, looking for chunks of words—sometimes mere snippets, sometimes whole chapters–that inspire me or make me think about my life and work a little differently and that, hopefully, quicken my pulse.

As a teacher, my reading is circumscribed during the parts of the year I call “terms,” restricted for the most part to the books I’ve assigned and the writing of my students. For the most part. The exception comes during the hour or two I spend in my writing shack each night around cocktail hour, a period of time during which I read whatever the hell I want. Often, as I’ve described in here before, I jump from book to book, looking for chunks of words—sometimes mere snippets, sometimes whole chapters–that inspire me or make me think about my life and work a little differently and that, hopefully, quicken my pulse.

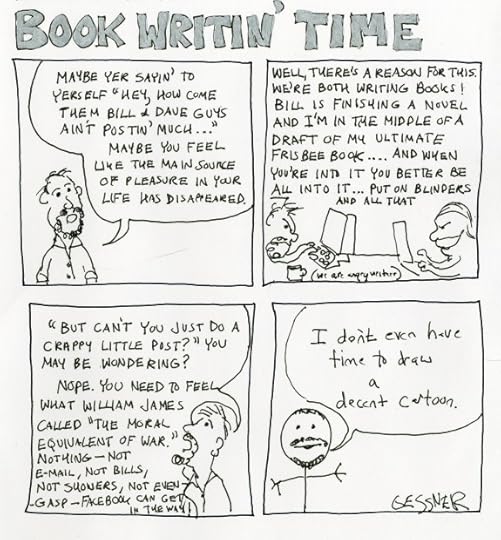

The exception to this rough schedule is the termless times, the periods when school mercifully slackens. Then all reading time becomes shack reading time. Sometimes I read specifically for my own writing. For instance, I’m just now starting to write Ultimate Glory, my memoir and history of Ultimate Frisbee, and so to get my energy up and get in the right frame of mind I’ve been re-reading David Halberstam’s The Amateurs and Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, which is a fantastic example not just of high energy writing but of the sort of deep reporting I hope to do. But a lot of my shack reading is less conscious, more ragtag, and I read, as Johnson put it, “by inclination.” This doesn’t always work and when it doesn’t I sit there bored, uninspired.

But occasionally there is some random magic. This happened last week when I dug into an old box of books and came up with Dr. Sheehan on Fitness. George Sheehan was a doctor, runner and a writer who wrote regular essays for Runner’s World magazine during the ‘70s and ‘80s. I got into his work back in my twenties, when I lived mostly in Boston or on Cape Cod, and began running pretty regularly. Though I had stopped reading him by the time I moved to Boulder in 1991, I suspect his words had a residue effect on me as I began to bike in Colorado. What Sheehan said about fitness I still say to my writing students: make it a priority, do it every day, invest in it with your whole self.

If that last sentence seems a tad more upbeat, inspirational and groovy than my usual ones then that may be the good doctor’s influence as well. His essays are casual and personal, but they are also consciously meant to inspire, and, for my money, they do. At times they read like Emerson Lite (there are those who say that Emerson reads like Emerson Lite but I disagree), but more often they create the kind of internal excitement that gets you running for your sneakers or your pen, ready to enter a 5 k or write a chapter. He writes: “The search for meaning needs more. It needs a challenge, a test, and experience for the self in extremity. It needs, as William James says, a theater for heroism, a moral equivalent of war.” And: “If we are going to be heroes, and heroes we must be, sports offers us the preeminent arena in which to achieve this status.”

Which fires me up. Not just for jogging but for writing. And for living a more consciously elevated life, too, since the subtitle of almost all of Sheehan’s books and essays could be “The Art of Living.”

Today’s bad advice then is listen to your doctor, or at least to this doctor.

As it turns out, there is a good way to do just this. The book I read first was Dr. Sheehan on Fitness (published as a hardcover as How to Feel Great 24 Hours a Day) but this led to The Essential Sheehan, a hardcover compilation that Rodale put out a couple of years ago. If you are feeling blasé about your sentences or your self you could do worse than checking it out.

December 8, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Fifteen Things for When the World is Shitty and Terrifying

Laquan MacDonald was seventeen and murdered by a Chicago police officer in cold blood. I watched a video of his murder, along with most of America, right in between reading about how Americans are terrified of letting refugees from war-torn Syria into the country, and reading about how a man with a rifle opened fire at a Planned Parenthood in Colorado, and now hearing about San Bernadino.

I can’t think of anything else to say that hasn’t already been said about how horrible and sad and awful and bleak and shitty and unfathomable all of those things are. I can’t. I don’t have the words for that today. So instead, here are fifteen things that you can do to make your world just the tiniest bit less shitty and terrible.

Open your closet. Find one warm piece of clothing that you haven’t worn in awhile. Bring it to a place that will give it away, for free, to someone who needs it.

2. Go to a public park or playground. Sit on a bench. Watch some kids running around playing. Don’t get up and try to engage with them, don’t depress yourself further, don’t go down a sadhole if you want kids but don’t have them, or if your own relationship with your kids/parents isn’t perfect. Just… sit and watch. Turn your brain off for a bit. If your brain has to work, picture the way that kid’s body works: the air filling the lungs and expelling laughter, the tiny heartbeat pulsing and racing, the immense amount of neurons firing to process the information that keeps eyes blinking and ears listening and skin tingling and lungs expanding and contracting.

running around playing. Don’t get up and try to engage with them, don’t depress yourself further, don’t go down a sadhole if you want kids but don’t have them, or if your own relationship with your kids/parents isn’t perfect. Just… sit and watch. Turn your brain off for a bit. If your brain has to work, picture the way that kid’s body works: the air filling the lungs and expelling laughter, the tiny heartbeat pulsing and racing, the immense amount of neurons firing to process the information that keeps eyes blinking and ears listening and skin tingling and lungs expanding and contracting.

If you see a parent looking stressed out, give them an encouraging smile, as if to say, “You’re doing a great job.”

3. Google a small-business florist near the site of any recent tragedy. Call and explain that you’d like to pay for flowers to be sent to, say, the staff of the Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs (3480 Centennial Boulevard, Colorado Springs, CO 80907), or to Hope Church (5740 Academy Blvd N, Colorado Springs, CO 80918), where slain police officer Garrett Swasey and his family were members. When you leave a note, don’t make it about you, or your political or religious beliefs. Leave it anonymous, or simply say, “From a stranger who thought you might be sad today.”

3. Google a small-business florist near the site of any recent tragedy. Call and explain that you’d like to pay for flowers to be sent to, say, the staff of the Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs (3480 Centennial Boulevard, Colorado Springs, CO 80907), or to Hope Church (5740 Academy Blvd N, Colorado Springs, CO 80918), where slain police officer Garrett Swasey and his family were members. When you leave a note, don’t make it about you, or your political or religious beliefs. Leave it anonymous, or simply say, “From a stranger who thought you might be sad today.”

4. Think of a song you love, preferably by a non-super-famous musician. Even if you already own it, download it  again. Think about how that 99 cents is actually telling that musician that their work has value.

again. Think about how that 99 cents is actually telling that musician that their work has value.

5. There are several Dunkin’ Donuts within the general area of Sullivan House High School, the alternative school in Chicago’s South Side where Laquan MacDonald was enrolled. It’s probably a tough week for teachers and students both. Buy an e-gift card. Send the link to the faculty. Tell them a stranger bought them coffee.

5. There are several Dunkin’ Donuts within the general area of Sullivan House High School, the alternative school in Chicago’s South Side where Laquan MacDonald was enrolled. It’s probably a tough week for teachers and students both. Buy an e-gift card. Send the link to the faculty. Tell them a stranger bought them coffee.

6. Leave a copy of your favorite book in a public place. Trust that the right person will find it.

7. Locate your nearest animal shelter. You don’t need to adopt a pet, and you don’t need go in and volunteer, although that’s a really nice thing you can do, too. You can just look at the puppies and kittens playing for awhile, or feel what it’s like to hold a tiny, furry, purring creature in your arms for a bit.

7. Locate your nearest animal shelter. You don’t need to adopt a pet, and you don’t need go in and volunteer, although that’s a really nice thing you can do, too. You can just look at the puppies and kittens playing for awhile, or feel what it’s like to hold a tiny, furry, purring creature in your arms for a bit.

8. Here’s a link to Amazon, where you can buy a ten-pack of socks for $9.99. Click the link. When you are asked for your shipping address, find the address of a homeless shelter in your community. If you don’t have a homeless shelter in your community, here’s mine.

8. Here’s a link to Amazon, where you can buy a ten-pack of socks for $9.99. Click the link. When you are asked for your shipping address, find the address of a homeless shelter in your community. If you don’t have a homeless shelter in your community, here’s mine.

9. Think of the kindest person you personally know. Then write her/him an email, letting them know that you thought of them and hope they are doing well.

10. Buy an extra box of tampons the next time you’re out shopping. Leave them in the ladies’ room of your workplace for anyone to take. (If you’re a dude and this weirds you out, talk to this fifteen-year-old kid about it).

11. Think about the people that you frequently interact with in your daily life but know very little about: the barista who works at your coffee shop, the janitor in your building, your mailperson. Introduce yourself. Call them by name whenever you see them again.

12. Go to a diner. Order a milkshake. Tip ten dollars.

13. Get a pile of index cards and a sharpie. Write down, “You are Important,” or “Breathe.” Carry them with you as you go about your day, leaving them in waiting room magazines, on car windshields, in elevators, in bathroom stalls. Keep one for yourself. We all need the reminder sometimes, too.

14. Dig up an embarrassing photo of yourself from your teenaged years. Post it online. Laugh gently at the person you were, and celebrate the human you are now. If you’re still in the process of living through your teenaged years, take lots of pictures. You’re doing great.

14. Dig up an embarrassing photo of yourself from your teenaged years. Post it online. Laugh gently at the person you were, and celebrate the human you are now. If you’re still in the process of living through your teenaged years, take lots of pictures. You’re doing great.

15. Think about the fact that the world can feel like a flaming cesspool of dog shit, over and over and over again. Think about bodies being blown up over insignificant cultural and political differences, think about blood being spilled out of human limbs for reasons that you will never fully understand. Think about everyone in your zip code who is homeless and hungry, cold, terrified, and lonely. Think about global warming, handguns and assault rifles, violence on television, rape statistics, domestic abuse. Think about terrorism, both domestic and abroad. Think about petty cruelty. Think about your childhood schoolyard bully. Think about the times that you won the argument but lost the friendship.

Think about all the times you got busy, and didn’t visit your relatives like you said you would, or didn’t give the dollar in the checkout line because times are rough and who even knows what the March of Dimes is. Think about how you don’t want to think about who grows your food or makes your clothes or pieces your iPhone together, because in the world we inhabit, it’s virtually impossible to exist without making some kind of ethical compromises. Think about how you were a turd in some small, stupid way this week alone, to your partner or sibling or parent, because it was simply easier to be a turd than to be selfless or kind in that moment.

Think about seven billion people out there in the world. Think about the statistical three hundred and eighteen thousand births today, or the one hundred and thirty-three thousand deaths.

Think about how enormously complicated all of this is.

Think about how Mother Theresa accepted funds from corrupt embezzlers, how George Bush is an oil painter, a husband, a father, and a war criminal. Think about Princess Diana’s life’s work of charity and goodwill; remember also that she was depressed, lived through bulimia, self-harmed. Name five celebrities, and then imagine them in the morning, with horse breath and red-rimmed eyes, stumbling to splash water on their face, wiping their ass with toilet paper, just like you and me.

Acknowledge that you’re probably going to just close this browser tab without actually doing any of those things. You’re probably not going to drop your clothes off at a homeless shelter, or donate to a struggling artist, or buy coffee for teachers in Chicago. I get it. I probably won’t, either. You’ve got limited funds and bills to pay and a life to live. I know. I do, too.

Accept that there are tons of incredibly easy ways to make the world a slightly less shitty place for everyone, and that you probably won’t do any of them, or at least not very many of them, and that while it’s not ideal, it doesn’t make you a terrible person. It just makes you a human.

Take a deep breath of gratitude for the people out there who actually do make the world a better place. Challenge yourself to be that person, in whatever small way you can manage right now.

Close your browser window. Shut down your laptop, silence your cell phone. Just for a minute, before you go back to Netflix, before you text someone, before you answer more emails or meet friends for drinks or order a pizza or whatever it is that you’re doing tonight: just for a second, take a moment to remember that the world is also pretty fucking magical, and you’re really lucky to be alive in it.

Do what you can.

Oh, and: return the shopping carts in the parking lot that others have abandoned, or mop up the spilled creamer at the Starbucks. It takes like ten extra seconds and it’s not that big of a deal.

#

Katherine Fritz is a woman in her twenties who lives in Philadelphia. She has a blog about that.

December 7, 2015

Bad Santa

So a few of my grad students asked me to join them last Friday for their holiday reading at our local radio station. In return they would give me a six-pack of IPA. The catch? I had to dress up as Santa. And not the nice, jolly Santa either. That other Santa…..Ho Ho Ho….