David Gessner's Blog, page 12

November 23, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “City on Fire,” by Garth Risk Hallberg

During the 3 or 4 days that I was immersed in this novel it was like an appendage, a siren that summoned me from the depths of sleep at 3 a.m: ‘Oh, yes, the book.’ And reach over to turn on the reading light, dive back into the tumultuous world of New York City during a few months in 1976-1977.

By the time I was living and studying and teaching in NYC, during the nineties, much of the city had been thoroughly scrubbed and sanitized by Guliani and his minions until it gleamed. Times Square had been Disneyfied and one of my neighborhoods on the upper West Side felt distinctly like a gated community. What a contrast with the New York of City on Fire. Hallberg, who intriguingly is too young to have actually lived it, describes a time of fire and foment and the meteoric rise of punk culture. Gerald Ford’s famous response to the city’s plea for bailout money during this time was, “Drop Dead,” as this most iconic of American megalopolises teetered on the brink of both insolvency and total anarchy. The subway was to be avoided and the notion of entering Central Park after dark was considered sheer lunacy. Yet amongst the lawlessness and the sense of things abjectly out of control there was a parallel mood of wild, unfettered, limitless possibil  ity–after all, if everything was falling apart, why worry about consequences?

ity–after all, if everything was falling apart, why worry about consequences?

The strands of the narrative are woven mostly by the young or youngish; there is Sam and Charlie, two suburba n Long Islanders drawn to the downtown punk scene, she a young beauty with an artist’s eye and an enthusiastic fanzine and Charlie, her gawky, endearing lovestruck sidekick who is up for anything. Then there are the sister and brother, Regan and William Hamilton-Sweeney, estranged heirs to one of the city’s great fortunes and their respective partners, Regan’s husband Keith, seduced into the Sweeney business empire and, Mercer, a transplanted Southern black m an lured to the city to teach, who falls in love with William. Add a cynical reporter, a jaded detective trying to hold on to the last vestiges of idealism and a shooting on New Year’s Eve in Central Park and you have all the ingredients for 900 pages of mesmerizing fiction.

Oh and lest I forget, there is anarchist punk rock band collective that aspires, with one dramatic act, to remind New Yorkers of the precariousness of existence, a flamboyantly eccentric art dealer and Sam’s father, one of the last of the firework artistes, as they are being slowly and inexorably replaced by digital technology.

At the heart of Hallberg’s accomplishment here is how deeply he makes us care about the city and its denizens without ever resorting to sentimentality. When I read that one of the novel’s main characters had died, my grief was profound and visceral and when I discovered that the character had, after all, somehow miraculously survived, the rush of relief was just as genuine. On reflection I realized that these emotions were dual-faceted: on one hand I became inordinately fond of the characters and on the other, I am stupefied and bedazzled that the author could foster such readerly affection for a fictional creation.

The morning after a late night spent devouring the final pages of City on Fire, my wife asked me, “So, ready to return to the land of the living?” And that’s sort of the point: these people and this story are and always will be alive for me. Having been introduced, I feel stronger and better equipped to survive in the land of the living.

And if anyone tries to tell you that the novel is dead, simply point them towards City of Fire.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

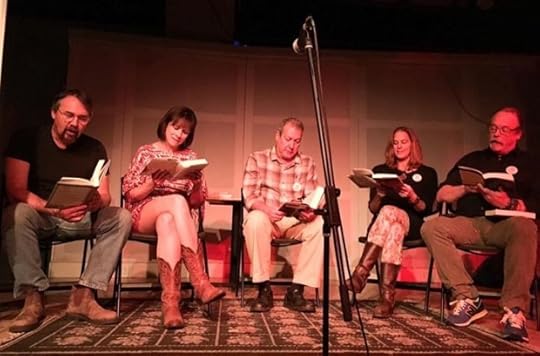

Bill and Dave’s Live at Space Gallery in Portland

We had a great night in Portland featuring Bill, Dave, Bill Lundgren, Kate Miles, Kate Christensen and Dave’s eyebrows.

November 18, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Get Thrown Out of Libraries

By special guest Ginger Strand:

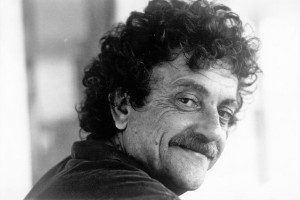

I only cried twice at the Lilly Library while researching my new book The Brothers Vonnegut. Indiana University’s beautiful archive has most of Kurt Vonnegut’s early drafts and letters, and I visited it several times while working on the book. The first time I cried was when I was going through a box of miscellaneous stuff and Kurt Vonnegut’s passport popped out. There he was, smiling up at me with that self-ironic grin. Overwhelmed with a sudden sense of loss, as if I had known him personally, I burst into tears. This never fails to draw furtive glances from fellow readers and concerned stares from reading room staff fearful you might do some harm to the paper.

The second time was on another visit, when I was reading letters Kurt wrote to his daughter Nanette during his separation from her mother. The letters were so raw, so real, so filled with the agony of failed marriage and the confounding anxieties of parenthood, that I couldn’t help weeping as I read them. I soldiered on that way for a while, reading and sniffling, but eventually I did step outside to collect myself. I myself feared I might do some harm to the paper.

I always seem to be the only one weeping in the archive. Or doing a happy dance when I discover something great. (I try to disguise it as standing up to stretch.) Or giggling. There was one point when I was researching my first book of nonfiction, Inventing Niagara, when I thought I might be forcibly ejected from the American Antiquarian Society for giggling. I was reading some very early accounts of explorers in the New World, and they were hilarious. Other readers were glancing over. The American Antiquarian Society, a national research library housed in a Colonial revival building in Worcester, Mass., is a rather formal archive, with scads of rare books and periodicals, and scads more rules and regulations about how you may interact with them. You sit in a grand, paneled reading room with portraits—founders presumably—glaring down on you. You wear white gloves if you’re handling anything delicate and you can’t so much as go to the bathroom without getting what amounts to a hallway pass from the reading room staff.

None of this is unusual. In fact, the AAS insists they are actually rather relaxed in their protocols. Whatever. All I know is that when I read an account of two French explorers actually running into each other in the woods—as if the so-called undiscovered continent was so lousy with French explorers you couldn’t toss a beaver without hitting one—I laughed out loud. And the historian sitting at the desk next to mine threw down his regulation pencil in disgust and said, “I give up. Just tell me what’s so damn funny.”

I remain unrepentant. Archives look and act like dry, stuffy, hidebound places, mausoleums for stashing history’s corpse. But in fact, they are wild, glorious places packed with drama and intrigue and sex and scandal—in short, with stories. And not enough writers take advantage of them. Archives are the backrooms of history’s rave—the place where you get to rub up against total strangers and dive blindly into uncharted territories. And we writers have pretty much ceded this party to scholars and academics. Well we shouldn’t.

Wade into the archive, I say, and though you have to check your snacks and pens and coffee cups and coats and backpacks at the door, don’t check your emotions. The richness of human life deserves your empathy. Laugh, sigh, groan, weep, marvel. Make a spectacle of yourself. Get kicked out. Get walked to the door. Stagger out, still marveling, into the daylight with a story clenched in your teeth. Then share it with the rest of us, so we can marvel too.

November 16, 2015

Why Wildness Matters

This past weekend the Wall Street Journal ran this review I wrote of Jason Mark’s “Satellites in the High Country.”

This past weekend the Wall Street Journal ran this review I wrote of Jason Mark’s “Satellites in the High Country.”

Wildness, that important but often vague word, is at the heart of

Jason Mark’s “Satellites in the High Country.” As is this question:

Have we been Googled and GPSed, Facebooked and fracked and generally over-computerized into such domesticated creatures—living in a minutely mapped world of diminished species, diminished biodiversity and diminished space—that experiencing wildness is no longer possible?

Good question, Mr. Mark. Ten years ago I followed the osprey migration

from Cape Cod to Cuba and marveled that, since I was carrying a

cellphone for the first time, I could be tracked just like the

radio-tagged birds I was chasing. As everyone knows, the changes in

the decade since have been head-spinning, but what continues to amaze

me, as a professor, is how technology and its uses change from year to

year, as if a whole new species of Homo sapiens were coming back to

school each fall.

One of the pleasures of “Satellites in the High Country” is that Mr.

Mark does not follow the usual nature writer’s path and just throw the

word “wild” out there, waving it like a flag, before carrying on with

his own happy tramps into the wilderness. His approach to decoding the

word is comprehensive, and he begins logically with etymology, laying

out all the definitions but focusing on “self-willed” and

“uncontrolled.”

“There’s simply something tougher about wild things,” he writes.

Wilderness and wildness are not synonymous, but Mr. Mark argues that

wilderness, especially big wilderness, is where wildness most often

happens. The reasons we need to continue to protect large swaths of

wilderness are many: because wilderness is where evolution occurs;

because it is where we can find an alternative to, and solace from,

our cluttered virtual lives; because it is simply moral to allow other

creatures their rights on this planet instead of carrying on like

anthropocentric bullies.

These arguments will sound familiar, but as Mr. Mark notes, the very

concept of wilderness has recently been under intellectual assault: We

are told by contemporary environmental thinkers that we have entered

the Anthropocene, the age of man. And since there really are no

pristine, untouched lands, we should move on and treat the Earth like

the human garden it is, embracing our role as gardeners and

benevolently guiding the fate of wild things.

Mr. Mark, who was the co-founder of San Francisco’s largest urban

farm, knows a thing or two about gardening, and he gives it its due.

He acknowledges that to be a gardener is a noble ambition. But he

argues that in the United States our wilderness areas, which

constitute less than 5% of our land, should be kept truly wild—that

is, “free from our intentions,” including the intentions of those

mostly benign control freaks known as conservation biologists.

This is a hard argument to make as many conservationists wrestle with

climate change, and most environmentalists prefer what Mr. Mark

rightly calls “the Pottery Barn mentality”—that is, “you broke it, you

fix it.” We need to right our environmental wrongs, the argument goes,

moving marmots north, for instance, as the their habitats warm. Mr.

Mark is hardly anti-marmot, but he makes a strong case that we need at

least some places that we keep our meddling hands off of.

You will notice that so far I have focused on the ideas in “Satellites

in the High Country,” and to my mind the ideas are the best part of

the book. I am slightly less thrilled with the more conventional,

journalistic presentation of these ideas, braided as they are into

trips to wild places like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the

Black Hills, Yosemite and the Olympic Wilderness in the Pacific

Northwest. These trips are well-described and linked clearly to the

book’s intellectual lessons, but the book’s genre conventions leave it

feeling a bit, well, tame. “Satellites in the High Country” never

achieves the electric heights of Jack Turner’s “The Abstract Wild”

(1996), a work full of revolutionary verve that, in its thorny

intractability, was as self-willed and uncontrolled as its subject.

What Mr. Mark’s book does that earlier books did not is to

intelligently place the cry for wildness inside a time when the end of

nature and the rise of the virtual have been almost universally

declared. He never fails to acknowledge just what a predicament we are

in, both environmentally and intellectually. The planet is tamed and

all is known, we are told, so why not accept our fates, take our

numbers and do our best as we trudge through this unwild world?

Mr. Mark argues the opposite: that we have never needed the wild more

than we do now. “Big Data in the backcountry? No thanks. Wifi in the

woods? I think I’ll pass.” Someone could write these sentences

blithely, but he does not. He knows that it will be a nearly

impossible thing to respect the rights of other species and continue

to place lands beyond human hands, and that it will require what many

would consider the opposite of wildness: discipline. But if difficult,

it is also necessary and, Mr. Marks believes, both morally and

practically imperative. Because if we do not we will sever a lifeline

to the place we came from and to any lives beyond our own.

November 13, 2015

“At Sea,” an excerpt from SUPERSTORM, by Kathryn Miles

Superstorm Sandy began its genesis as a typical late season tropical storm. However, as the hurricane marched up the east coast of the United States, it collided with a powerful nor’easter and morphed into a monstrous hybrid. The storm charged across open ocean, picking up strength with every step, baffling meteorologists and scientists, officials and emergency managers, even the traditional maritime wisdom of sailors and seamen: What exactly was this thing?

Hurricane Sandy was not just enormous, it was also unprecedented. As a result, the entire nation was left flat-footed. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration couldn’t issue reliable warnings; the Coast Guard didn’t know what to do. In Superstorm, journalist Kathryn Miles takes readers inside the maelstrom, detailing the stories of dedicated professionals at the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service. The characters include a forecaster who risked his job to sound the alarm in New Jersey, the crew of the ill-fated tall ship Bounty, Mayor Bloomberg, Governor Christie, and countless coastal residents whose homes—and lives—were torn apart and then left to wonder . . . When is the next superstorm coming?

For the crew of the tall ship Bounty, the answer to that question came far too late. Four days earlier, the ship had set sail from New London, Connecticut, bound for Florida. As they made their way southward, the sea state worsened: 40-foot waves slammed against the ship’s wooden hull; winds topped 80 miles per hour. Late in the evening on Sunday, 28 October, the crew of the Bounty was forced to accept the inevitable: their ship was taking on a dangerous amount of water. Abandoning ship seemed all but inevitable. The only question that remained was whether the 16 people on board would survive what happened next.

Monday, 29 October

2:28 a.m.

Elizabeth City, North Carolina

62˚F

Barometer: 29.31 inches (dropping)

Winds: 27 mph (NW)

Precipitation: Rain

Joseph Kelly was pacing around his house, stopping every few minutes to check the weather. Storm surge in Maryland was more than four feet. Waves tore through the pier in Ocean City, Maryland. Twenty-foot waves were being recorded as far north as Islip, on Long Island, New York. Sandy’s predicted change in direction was happening. “The turn toward the coast has begun,” tweeted the Weather Channel. Kelly’s phone rang just after he read that. It was the Coast Guard base, saying that McIntosh’s C-130 crew hadn’t been able to drop dewatering pumps for the Bounty.

Kelly was incredulous. And more than a little mad. “What do you mean they tried to drop pumps? I said establish comms. That’s it.”

The operations chief on the other end didn’t know what to say to that. He stammered a little. Kelly hung up and got dressed. There was no way he was going to sleep now. He’d always told his pilots that he would support them even if he disagreed with their decision, so long as they could demonstrate a logical thought process. He was really hoping that McIntosh had one now.

3:40 a.m.

130 miles off Cape Hatteras

62°F

Barometer: 29.21 inches (falling)

Winds: 57 mph (N)

Waves: 38 feet

Precipitation: Rain

They were the only two planes in the sky for hundreds of miles. That struck both crews as eerie. Wes McIntosh and his Coast Guard crew continued to circle over the Bounty, ducking down to make radio contact with John Svendsen, then returning to a safer cruising pattern. His crew was sick and getting pretty banged up. That worried him. Not far from him, the Hurricane Hunters had their own concerns. Jon Talbot didn’t like what the data was telling them. Dropsondes on board found a small surface area where winds were registering above 90 miles per hour. Thunderstorms were continuing to build around the storm’s center. They flew through a perfectly round eye 28 miles across and made note of that, too. “#Sandy is still a fully tropical cyclone at this time,” tweeted the Weather Channel. “No doubt about it.”

One 150 miles off of Hatteras, the Bounty crew was huddled in the great cabin. Some of the headlamps had started to flicker out. They were waiting, but for what they didn’t know. Captain Robin Walbridge had thought they could make it until morning. Now he wasn’t so sure. Josh Scornavacchi had snagged a guitar out of the lazarette. He was hoping there’d be time for Claudene Christian to sing one last song. But they didn’t get a chance. Their captain told them it was time to go. They struggled to climb into their survival suits. Claudene Christian had never practiced getting into one. Jess Hewitt showed her how and cracked a few jokes. “Remember the number of your suit,” she told Christian. “That way you’ll know where to put it back.” That made her friend smile.

Walbridge always warned his crew never to take anything with them in an emergency. “You can’t go back for anything,” he would say. “Anything.” But he did, somehow. Even injured, he managed to make his way down to his cluttered little cabin. He took Claudia’s picture off the wall and stuffed it into his suit. Doug Faunt grabbed his teddy bear. Jess Hewitt took the medallion given to her by the crew of the Mississippi: by valor and arms, pride runs deep. She also grabbed a hair tie and a cigarette lighter: She planned on having a smoke as soon as they made it back to shore. She went back down for a couple of other things, too: Prokosh’s captain’s license—it was a bitch to get a replacement one, she’d always heard—and his pea coat. He had to be freezing. Claudene asked her to go back again. She really wanted her journal, she said.

An hour later, and they were all up on deck. The ship was listing. The skies were clearing. Every once in a while, they could pick out the lights of the C-130 directly overhead. McIntosh and his crew had done exactly what their commander had told them not to do: They flew in and tried to help. When conditions there got too bad, they’d fly back to their safe holding space on the side of the storm.

“It was important. We were holding their hands,” says Mike Myers. “We were trying to say, ‘You’re not alone. Keep fighting.’”

Somewhere off in the distance, the Hurricane Hunters’ C-130 was struggling through its own flight pattern.

4:28 a.m.

130 miles off Cape Hatteras

On board the Bounty, the crew congregated into two groups, braced against whatever they could find to keep from tumbling down the steeply pitched deck. Jess Hewitt thought about capsizing and tried to reassure herself: I just need to keep breathing. If I can keep breathing, I’ll be okay. She and Drew Salapatak clipped their climbing harnesses together. You better not leave me, she told him. Meanwhile, Claudene looked around: Matt wasn’t nearby. She caught sight of him up near the mast. She smiled and darted to him. Even in the storm, Anna Sprague remembered thinking it was “a cool move.”

Claudene never wanted to be alone. Especially in the dark. She nestled in with Sanders. “It’s going to be okay, baby girl,” he said. That was his nickname for her: baby girl. He kept saying it over and over again: “It’s going to be okay. It’s going to be okay.”

Above them, the C-130 kept circling, ducking down just long enough to check on the status of the ship. Every time they did, the turbulence became unbearable. The crew in the back were vomiting. The cargo bay door was covered in it.

Everything appeared to be in stasis. Until suddenly, it wasn’t. A wave—bigger than the rest—struck the side of the ship. The vessel screamed and rolled from a 45° angle to a 90° one. They were dangling over the water now. Debris rained down around them. A few crew members jumped. Some tried to hold on. Matt Sanders caught his foot—it was pinched and he was stuck. Claudene panicked. “What do I do?” she screamed. “What do I do?”

“Claudene, you just have to go for it,” Sanders replied. “You have to make your way aft and get clear of the boat.”

So she did. Or tried to, anyway. The last he saw of her, she had worked her back to the mizzen—back to where her original group had been crouching. She was standing on a rail, looking as if she was trying to decide whether or not she should jump. There was no more singing. He never saw her again.

The human body will do anything to avoid drowning. It begins with an involuntary desire to gasp. Go ahead, your cells plead, take a breath. The pulse accelerates. Carbon dioxide levels in the blood rise, creating first heightened alertness, and then anxiety. Once that carbon dioxide reaches a pressure of 55 mm in your arteries, there is no longer any reasoning with your nonthinking self. It will force you to take a breath. If you are still underwater when this decision is made, that is what you will inhale. And if you do, your larynx will spasm—violently—again and again as it attempts to divert the water to your stomach instead of your lungs. In the process, this spasm will also force you to exhale any last remaining air that you didn’t even know you had. Your body will do anything—everything—to keep your lungs safe. And this commitment will work, up until the very last second. No matter what, your nonthinking brain will preserve your lungs, the place where air converts into life. Autopsies of drowning victims reveal gallons of water in their stomachs, bellies distended in a last-ditch effort to preserve their lungs. So long as it is conscious, the brain will drink until it can breathe.

In the storm-churned sea, the Bounty crew was gulping down gallons of oily seawater as they tried to thrash away from the ship. No matter how hard they tried, they could not find enough air. They flailed against debris, trying to grab anything that might save instead of kill them. Most of them were quickly separated. Not Jess Hewitt and Drew Salapatak. They were still tethered together and now trapped underwater. Jess struggled and writhed and bit at her harness, all too aware of what was happening. But still she was pulled down, down, down. She felt like she had become a giant weight. She began to give up. I can’t fight this, she thought. She prepared to give up. And just then, she popped to the surface. Somehow, Drew had wriggled out of his harness and saved them both.

For now.

Jess faced the Bounty, now lying on its side. Each time a wave rolled by, it would possess the ship, raising its enormous masts and spars high into the air before slamming them down again. One of her crew mates got caught on the mizzen mast and was lifted 20 feet in the air. He thought he heard a voice say Jump, Jump! So he did, into the recirculating suction caused by the vessel. Svendsen was there, too. Jess watched in horror as the rigging slammed down again, one of the spars smashing against the first mate’s head. She turned away and tried to swim; she didn’t want to see any more.

Kathryn Miles is the author of Superstorm: Nine Days Inside Hurricane Sandy, All Standing, and Adventures with Ari. Her articles and essays have appeared in dozens of publications including Best American Essays, Ecotone, History, The New York Times, Outside, Popular Mechanics, and Time. She currently serves as writer-in-residence at Green Mountain College and is on the editorial board of Terrain.org.

“At Sea” is an excerpt from Superstorm: Nine Days Inside Hurricane Sandy by Kathryn Miles.

Read an interview with Kathryn Miles appearing in Terrain.org Issue 31.

November 11, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: This is Your Life, Harriet Chance, by Jonathan Evison

Harriet Chance is a true mensch. Mensch as in, “someone to admire and emulate, someone of noble character.” And though some might question the characterization of Harriet as being worthy of emulation, there can be no dispute that she is of noble character.

Harriet is at the center of Jonathan Evison’s delightful romp of a novel, This Is Your Life, Harriet Chance. Harriet’s story is gradually told through a series of episodes that pinwheel through time and are recounted by a third person narrator; these straightforward vignettes are interspersed with the narrative intrusions of a game-show host modeled after Ralph Edwards and his show from a half century past, “This Is Your Life.” A precursor to today’s reality TV shows, “This Is Your Life,” involved the host surprising his subjects on air and then recounting their lives in a quasi-documentary format, replete with reunions with significant persons from the subject’s past.

Harriet is recently widowed and living comfortably in the house she shared with Bernard, the deceased husband who spiraled down the black hole of dementia in his final years. To describe Harriet as ‘long-suffering’ merely scratches the surface of her domestic servitude. As the game-show stand-in intones, “Yes Harriet, for the next 50 years you’ll eat what Bernard eats, vote how Bernard votes, love how Bernard loves and ultimately learn to want out of life what Bernard wants out of life.”

Harriet is recently widowed and living comfortably in the house she shared with Bernard, the deceased husband who spiraled down the black hole of dementia in his final years. To describe Harriet as ‘long-suffering’ merely scratches the surface of her domestic servitude. As the game-show stand-in intones, “Yes Harriet, for the next 50 years you’ll eat what Bernard eats, vote how Bernard votes, love how Bernard loves and ultimately learn to want out of life what Bernard wants out of life.”

Harriet is surprised to learn that before Bernard died he bought an Alaskan cruise for two… oh, and did I forget to mention that Bernard is still very much a part of Harriet’s life as a ghost seeking an opportunity to explain himself? Harriet decides to go on the cruise and is undeterred even when her best friend Mildred backs out. Once on board, Harriet finds out that she may not have been Bernard’s intended companion and the revealed infidelity threatens to finally overwhelm her. But Harriet endures, because as Evison makes clear, that is what the ‘long suffering’ women of this generation did. In the interest of keeping the family intact and safe, they endured whatever life threw at them with the ferocity and single-mindedness of a lioness defending her cubs.

The surprises continue, as one of Harriet’s cubs, her estranged daughter Caroline, appears on board. Amidst the endless buffets and lounge acts, the two begin to tenuously try to rebuild a frayed relationship. Though sometimes the stop and start flashbacks threaten to overwhelm the narrative, Evison is a crafty writer who knows exactly what he is doing. He writes with great affection for his characters and a devastating sense of humor. In the end, he is creating a tribute to Harriet, a woman who symbolizes the entire generation of American women that quietly shouldered the slings and arrows of life’s fortunes and misfortunes so that those around them might blithely sail through life, safely protected and largely unaware.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

November 6, 2015

The Meal of a Lifetime

In August of 2010, Brendan and I lived at a three-week artists’ residency in southern Germany. “You’ll live in a castle,” the organizer who’d invited us had promised. So we arrived at the Schloss School, a former monastery turned castle turned boarding school, with visions of candlelit dinners in a grand medieval hall (at least I did) to find that we were to eat three meals a day in a side room of the school cafeteria, with no wine served, with thirty other artists from various countries. (We also slept in dorm rooms, in kiddie beds.)

The food was heavy and bland, since this was, after all, a boarding school, and a German one at that. But worse, the administrators in charge of the residency regularly forgot to tell the kitchen staff about field trips or bonfire suppers, and likewise, to inform us residents about mealtime changes. This created a constant state of war between artists and cooks: When we showed up late or early, they spat at us. When we came to a meal having failed to notify them that we wouldn’t be at the one prior, they threatened not to feed us. I have never been yelled at as much as I was during those three weeks in the Bodensee. And it was all in German. It was terrible. It made me lose my appetite, which is nearly impossible.

After the residency, Brendan and I hightailed it (in other words, took a train) to Brittany, to visit friends of his family. Jean-Louis and his wife, Marie, and their son live in an old stone house in a small, insanely picturesque village called Saint-Briac-sur-Mer. Jean-Louis is a real cook, whereas Marie, by her own admission, can’t boil an egg. They’re both French, but Marie is also Russian, which gives her personality a tragic depth. She has olive skin, wide blue eyes, and short, curly hair, and is a few years younger than I am. Jean-Louis is an energetic, handsome man twenty-five years older than she is, which beats Brendan’s and my age difference by five years. As a foursome, we all seemed to be about the same age, which proves something, maybe.

After the residency, Brendan and I hightailed it (in other words, took a train) to Brittany, to visit friends of his family. Jean-Louis and his wife, Marie, and their son live in an old stone house in a small, insanely picturesque village called Saint-Briac-sur-Mer. Jean-Louis is a real cook, whereas Marie, by her own admission, can’t boil an egg. They’re both French, but Marie is also Russian, which gives her personality a tragic depth. She has olive skin, wide blue eyes, and short, curly hair, and is a few years younger than I am. Jean-Louis is an energetic, handsome man twenty-five years older than she is, which beats Brendan’s and my age difference by five years. As a foursome, we all seemed to be about the same age, which proves something, maybe.

As if he sensed the Sturm und Drang of our recent culinary experience, Jean-Louis fed us, to put it mildly. On our first morning there, before lunch, he sauntered out in his espadrilles to the village market, which camped outside their front door once a week (it was like a movie set, missing only an accordion player and Audrey Tautou), and bought a dozen oysters, each, for everyone. He came home and shucked them all and rested each dozen on a bed of fresh wet seaweed, and then he opened a bottle of cold Pouilly-Fuissé.

As if he sensed the Sturm und Drang of our recent culinary experience, Jean-Louis fed us, to put it mildly. On our first morning there, before lunch, he sauntered out in his espadrilles to the village market, which camped outside their front door once a week (it was like a movie set, missing only an accordion player and Audrey Tautou), and bought a dozen oysters, each, for everyone. He came home and shucked them all and rested each dozen on a bed of fresh wet seaweed, and then he opened a bottle of cold Pouilly-Fuissé.

We gathered around the table; lunch began. Those oysters were plump and robust but awesomely weird, unlike any I’d ever had: mineral, flinty-tasting, zinc mixed with succulence. Their deep, shaggy shells were filled with brine. The flat tops of their shells, like caps, contained nuggets of oyster meat we chewed off before emptying each oyster body down our gullets, seawater and all. With these, we ate buttered bread, even gluten-intolerant me, because fuck it, that was the best lunch of my whole life.

Afterwards, we all staggered off for naps. I slept so deeply I had no idea where I was when I woke up. Those oysters had a narcotic quality, like the poppies in “The Wizard of Oz.”

[Kate Christensen is a novelist, memoirist, journalist, and bon vivant who lives in Portland, Maine, not far from Space Gallery, where she will be appearing with the actual Bill and Dave and fellow guests Bill Lundgren and Kate Miles for Bill and Dave’s Live!on Friday, November 13, 7:00 p.m. It turns out, amazingly, that the Belon oysters of Brittany also live in Maine, where they’re more accurately called the “European flat oyster,” since only true “Belons” come from the Belon River estuary. Call them what you will, Belons were transplanted to Maine decades ago.]

November 4, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Walk a Mile in their Shoes

Ooh, those people and groups and activities and works of art and parts of the country and professions and foods and music and movies we hate. Musicals! Someone said to me recently, just the one word, meaning how awful. But I like musicals. Always have. And here’s an acquaintance assuming I agree with her–because who in their right mind wouldn’t? These days I’m always ready to answer with the truth, and did, trying to sound affronted: “I like musicals.” I like lots of stuff that you don’t like. That doesn’t make me crazy. Anyway, bad advice for writers this week is to like something you hate. Danny Kaye movies? Sushi? HipHop? Camping? Cats?The method is to immerse yourself in the hated subject or subculture, giving all of your attention and none of your judgement, all in order to understand a character who isn’t like you in whatever specific regard. If you’re a hater, you’re not going to get to some of the richest corners of a character’s (villain or hero, doesn’t matter) inner life unless you find a way to appreciate the things your character (who’s nothing like you), loves.

This works in nonfiction, too. And it works as a tool of reportage. Before you go talk with the gun advocate, study up, even go to a shooting range and rent a Glock or whatever they’re called and blast some paper targets. That makes you someone your source is going to talk to, and not just talk, but spill the beans, baby. Or memoirist, listen. Your sister loved punk rock while you abhored it. But get some records, punk, punk, punk, listen till you’re hooked. Call up articles and videos and images on the web on the subject and the history, and fit all you learn into your own timeline. Then write your piece. You know how actors go work in a mine for a month to get their portrayal right?

Do that as a writer.

November 1, 2015

What is Perfect? This Short Film by a Couple of Awesome Teens, That’s What!

My daughter and her friend Maeve made this short film for their summer English project when they were both fourteen. At last their classes have seen it, they’re fifteen, and I can finally share! Maeve wrote the music and sings it with a little help from Elysia, who choreographed the dance. Together they wrote, directed, edited, and absolutely everything else. Assignment was to address a social problem. Please feel free to share it around!

October 28, 2015

Great Minds, Little Minds

One of the deepest pleasures of reading literature is being in the presence of great minds. Please note that I didn’t say socially-responsible minds or consistent minds or minds that are exactly in step with how we are told we should think in the year 2015. I said great.

One of the deepest pleasures of reading literature is being in the presence of great minds. Please note that I didn’t say socially-responsible minds or consistent minds or minds that are exactly in step with how we are told we should think in the year 2015. I said great.

Conversely, one of the frustrations of the present is what you might call the tyranny of the small and rigid-minded. To be honest I’m not a big reader of magazine articles, though I sometimes write them, and I especially avoid pieces where I know I’ll end up feeling like I’ve been dragged down into the muck. “Largeness is a lifelong matter,” said Wallace Stegner. For some people so is smallness.

All this to say that I tried to avoid the recent New Yorker piece on Henry David Thoreau, despite the fact that more than a few people pushed it on me. With a title that seemed more suited for reality TV than a New Yorker piece–“Pond Scum”–you pretty much knew what you were going to get before reading it: a straight take-down piece that was meant to get hits and attention (look–it worked!).

The piece is consistently unpleasant, dragging out the boring old Thoreau laundry crap that we thought Rebecca Solnit had finally swept away years ago, but it is also, in its own strange way, kind of funny. Funny in that its author seems to be completely unaware that she embodies exactly what she criticizes in Thoreau. This is a writer (Schulz not Thoreau) who seems to love broad statements about what humans are and what they should be, who speaks with an apparently never-wavering sense of certainty, and who is always insisting on consistency in the way of the humorless. She tells us that Walden is “an unnavigable thicket of contradiction and caprice,” while at the same time seeming to believe that what Thoreau intended in his great book was a kind of Miss Manners’-style outline of how he thought we should really live. For those of us who keep going back to Walden, not as high school kids but as adults looking for both great lit and alternative ways to live in this crapped-out society, the books is a thicket, and that is part of the fun. It is not a set of rules, but a series of fantastic sentences (no mention of HDT’s writing in this piece except a paragraph on how–surprise, surprise–he was good at describing nature) that gnarl and twist, varying from the blunt to the circumlocutious, from the earnest to the briskly dismissive. Kathryn Schulz, we are told in her bio, is a New Yorker staff writer but she seems to miss the fact that what Thoreau mainly was was a writer. That he went to Walden to hang out in nature, sure, but also to get his work done, that is to find the time and space to create. Joseph Wood Krutch’s brilliant biography of Thoreau reminds us that going to Walden was both a symbol (not just of retreat but of commitment) and a practical solution to his writerly problems. (Unlike his critics, he really didn’t give a shit just how far or close he was to town.)

But back to humor. I mentioned the New Yorker article is funny. Particularly amusing is in the way Ms. Schultz holds up what she imagines to be Thoreau’s character to her own contemporary moral checklist to show us all his failings. Thoreau jokes about his edible religion and how little food he can get by on. Our writer’s response? “No slouch at public shaming, Thoreau did his part to sustain the irrational equation,so robust in America, between eating habits and moral worth.” Really? I could write a funny line but I think I’ll just suggest you re-read the sentence and let it incriminate itself.

There’s lots more to say here but here’s the biggest thing: Ms. Schultz just doesn’t get the joke. She tells us that “Thoreau regarded humor as he regarded salt,and did without.” She then quotes as an example of his humorlessness a famous passage about how Thoreau decides against having a doormat because it is “best to avoid the beginnings of evil.” The only problem is that Thoreau was obviously joking in those lines. He knew it was a doormat he was talking about. In fact, hyperbole is is a favorite technique of his and can be demonstrated in another famous line: “When sometimes I am reminded that the mechanics and shopkeepers stay in their shops not only all the forenoon, but all the afternoon too, sitting with crossed legs, so many of them—as if the legs were made to sit upon, and not to stand or walk upon—I think that they deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago.” A literal mind respond to that sentence by saying: Thoreau is bad. A looser, happier mind would say: Thoreau is kind of funny. Hyperbole and word-choice were two of his chief writerly tools, two reasons we remember him. He spoke loudly, he told us, because most people are hard of hearing. He admitted that if he repented anything it was “his own goodness.”

But enough. I knew I’d get worked up if I actually sat down and read the article and sure enough I did. It’s time to get out of here and go for a walk. I get that the writer of this article might not be as full of surety and humorlessness as she appears; maybe she just wanted to get some attention and so threw some rocks in the pond to see the ripples. No doubt this will be the most attention she will ever get, at least until she tries to take down her next great mind. The good news is that her work will soon be forgotten while Thoreau’s will be read as long as there are books.