David Gessner's Blog, page 16

July 8, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Get Up The Wall

I’ve written in this space before about how long, steep bike rides are good metaphors for writing a book. But yesterday, as I pushed and slogged up a ride that once seemed everyday but is now monumental, I thought that what I was doing was also a fairly apt metaphor for a writing career.

I’ve written in this space before about how long, steep bike rides are good metaphors for writing a book. But yesterday, as I pushed and slogged up a ride that once seemed everyday but is now monumental, I thought that what I was doing was also a fairly apt metaphor for a writing career.

It seems to me important to make a clear distinction between the writing itself and the attempt to get the writing out in the world. Obviously, both skill sets are needed to become a published writer in the first place, and also needed to publish books over the course of a career. The writing itself is what we usually talk about here, but for today let’s stick to this other thing. Unless you are insanely lucky, the getting of the work into the world takes almost as much persistence and commitment as the work itself. This is understandably frustrating to a young writer—“But my writing is good”—and remains to some degree frustrating to many published and not-so-young writers. I will not go as far as to say I am in control when I am at my writing desk,but I almost never feel as out of control as I do when I try to negotiate the world of publishing.

Of course the hill seems steepest from the bottom. I am full of admiration for the young writers I know who have been trying for years to get published, working at it every day despite the world’s indifference. By extension this means I’m full of admiration for my younger self, since I labored without any positive feedback, let alone publication, for over twelve years. At the time I didn’t regard what I was doing as heroic, but now, seeing others doing the same thing, I understand that there is at least some heroism involved.

The hardest part of yesterday’s ride was a section we used to call The Wall. It’s brutal and goes on forever. But having conquered it you pretty much feel you can do anything. It would be easy to suggest that The Wall represents that early unpublished stage of the career-ride. Easy but not entirely true. Because, while a young writer might not want to hear it, there are many Walls ahead. And while you may feel indomitable one day when you get up it, you still have to get up it again the next.

One thing you do gain, however—as my wife has pointed out to me—is the knowledge that it is possible to climb the thing. And those past climbs do give you some toughness, mental and otherwise, that will come in handy during the next ascent.

This admittedly has not been the most uplifting of Bad Advices. But I think I can muster a positive, if not ringing, conclusion. Because there is a sort of strange pleasure in trying to do the impossible, or at least the very large, on a regular basis. My former teacher, Reg Saner, a poet, essayist and mountaineer, calls it “the pleasure of the difficult.” As pleasure goes, it may feel a lot like pain. But it is if not a good pain then a necessary one. Without it there is no movement forward. Without it there can be no ascent.

July 5, 2015

June 25, 2015

Guy at the Bar: Vince Passaro on Post-Racial Life

It now seems undeniable to me that we have been living in a 50 year semi-coordinated backlash against the civil rights movement. There is no other way to explain how the conditions of economic and political life of African-Americans gets worse, while “racism” putatively wears away, and we become (laughs here) post-racial. I remember my working class white relations (largely but not entirely the males), furious throughout my childhood at the claims of African-Americans, the demands for equality. I remember the combined total of votes for Richard Nixon and George Wallace in 1968: 60 percent — even McGovern did better than Humphrey did that year, only four years after Lyndon Johnson’s landslide.

I remember the assassinations. I remember the de-toothing of HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development, created to enforce the fair housing laws that flowed from the Civil Rights Act of 1965) after Nixon fired George Romney, it’s first head. I remember the mothers, the mothers! turning over a school bus in Boston… I remember how short-lived busing was, how disparities in the funding of public schools grew worse and worse, how the schools in most of America remained segregated or grew more so. I remember how the massive expansion of the penal system was followed by systematic criminalization of being a young black male, how the prison population went up to near 2 million by the end of the Reagan years (it’s now well more than 2 million). I remember Reagan: his fantasy that a woman on welfare bought a few oranges with her $20 food stamp and then took the change and bought a bottle of vodka… fantasy because actually it isn’t possible to do what he said and he and his staff knew it – you didn’t get cash back for food stamps, you got other denominations of food stamps, which liquor stores do not accept. But I remember how the story felt so good to so many people. It felt SO good. I remember the Willie Horton ad in 1988 — the transparency of it, the crudeness — and I remember Clinton, early in 1992, abandoning for two days the New Hampshire primary campaign, where he was slipping badly and which he couldn’t really *afford* to abandon, just so that he could be sure to be in Little Rock when they executed a black man who’d lost half his brain in the shoot out that led to his capture. I remember this particular prisoner was reported to have asked if the guards could “save” the dessert from his last meal, so he could eat it “tomorrow.” Thus were Clinton’s “I’m no Dukakis, I Kill Negroes” bona fides established. (Why he was popular in the black community remains a mystery to me, as his policies did nothing but hurt that community). I remember when it became clear that there was no way a black man arrested for a minor crime (no matter his previous record, the dubiousness of the charges, or any other mitigating factor) would get a fair trial, would not serve time. I remember that black unemployment in the cities has steadily exceeded what its traditional levels had been prior to, say, 1965, when the Civil Rights Act passed and the “War on Poverty” got underway. I remember how mysteriously the Reagan era “war on drugs” somehow led to plentiful cheap cocaine and shortages and skyrocketing prices for marijuana, the relatively harmless drug of choice before crack. I remember crack. I remember the CIA assisting in and taking cash profits from cocaine trafficking out of Central America, and pouring cheap cocaine into American cities, so that they could give the money, illegally, to the contras. I remember more than this, but I’ll spare you. They did give us all a day off in honor of Martin Luther King (well, except in a couple of states) so what am I complaining about? I remember every implicitly self congratulatory (for whites) PBS special on the glorious victories of the civil rights movement while gerrymandering and bogus new voter ID legislation has further restricted black people’s abilities to vote. We made sure the civil rights movement succeeded in public and failed in private. We have made, since then, poverty invisible, created a numbing celebrity culture that makes the poor invisible even to themselves. It’s a masterful job. I congratulate us. They arrested the white guy for shooting nine black humans and put a bullet proof vest on him, lest anyone try to shoot him. They stopped at Burger King to get him some food. See? They care.

I remember the assassinations. I remember the de-toothing of HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development, created to enforce the fair housing laws that flowed from the Civil Rights Act of 1965) after Nixon fired George Romney, it’s first head. I remember the mothers, the mothers! turning over a school bus in Boston… I remember how short-lived busing was, how disparities in the funding of public schools grew worse and worse, how the schools in most of America remained segregated or grew more so. I remember how the massive expansion of the penal system was followed by systematic criminalization of being a young black male, how the prison population went up to near 2 million by the end of the Reagan years (it’s now well more than 2 million). I remember Reagan: his fantasy that a woman on welfare bought a few oranges with her $20 food stamp and then took the change and bought a bottle of vodka… fantasy because actually it isn’t possible to do what he said and he and his staff knew it – you didn’t get cash back for food stamps, you got other denominations of food stamps, which liquor stores do not accept. But I remember how the story felt so good to so many people. It felt SO good. I remember the Willie Horton ad in 1988 — the transparency of it, the crudeness — and I remember Clinton, early in 1992, abandoning for two days the New Hampshire primary campaign, where he was slipping badly and which he couldn’t really *afford* to abandon, just so that he could be sure to be in Little Rock when they executed a black man who’d lost half his brain in the shoot out that led to his capture. I remember this particular prisoner was reported to have asked if the guards could “save” the dessert from his last meal, so he could eat it “tomorrow.” Thus were Clinton’s “I’m no Dukakis, I Kill Negroes” bona fides established. (Why he was popular in the black community remains a mystery to me, as his policies did nothing but hurt that community). I remember when it became clear that there was no way a black man arrested for a minor crime (no matter his previous record, the dubiousness of the charges, or any other mitigating factor) would get a fair trial, would not serve time. I remember that black unemployment in the cities has steadily exceeded what its traditional levels had been prior to, say, 1965, when the Civil Rights Act passed and the “War on Poverty” got underway. I remember how mysteriously the Reagan era “war on drugs” somehow led to plentiful cheap cocaine and shortages and skyrocketing prices for marijuana, the relatively harmless drug of choice before crack. I remember crack. I remember the CIA assisting in and taking cash profits from cocaine trafficking out of Central America, and pouring cheap cocaine into American cities, so that they could give the money, illegally, to the contras. I remember more than this, but I’ll spare you. They did give us all a day off in honor of Martin Luther King (well, except in a couple of states) so what am I complaining about? I remember every implicitly self congratulatory (for whites) PBS special on the glorious victories of the civil rights movement while gerrymandering and bogus new voter ID legislation has further restricted black people’s abilities to vote. We made sure the civil rights movement succeeded in public and failed in private. We have made, since then, poverty invisible, created a numbing celebrity culture that makes the poor invisible even to themselves. It’s a masterful job. I congratulate us. They arrested the white guy for shooting nine black humans and put a bullet proof vest on him, lest anyone try to shoot him. They stopped at Burger King to get him some food. See? They care.

###

Meanwhile… since the assassinations in Charleston there’s been a feeble but persistent debate about racism vs. gun control vs. insanity: to which we can simply say, yes. It’s not portions of each. Racism is insanity, but not the excusable kind: it’s the denial of an inescapable human truth. Empathy, sympathy, love and community all were essential parts of daily human existence before we find evidence in human history of any detectable, coherent religion. To fail to recognize and *feel* the obligations of this element of our humanity is to be radically broken. So yes, it’s insane.

And gun control? Racism is the REASON we don’t have and we never will have constitutional and reasonable control on guns in this country. Looked at from the perspective of any other developed nation our failures in this arena also appear to be willful and insane. We monitor dogs and mopeds more than we monitor guns. We are — to get back to the human idea — tribal, yes. But the reason we have racism against African-Americans (by putative whites, though guess what boys, who knows where your mama mighta snuck around….) that goes so much deeper and lasts interminably longer, generation upon generation upon generation, than any hostility we manifest toward Latinos or any other immigrant group is because none of those “others,” as “other” as they may be, represent to us our own crimes and none of the others refuse so utterly to submit to our narratives. None of the others frighten us with the haunting notion of revenge. We (white Americans) are living with the all-too knowing children of our rapacity. They were our property but now they talk back. They do not wish to be like us, to emulate us or assimilate with us. They are generally willing to get along but it will be many, many more years before they trust us or think we’re sane.

There is so much more than this element of insanity and violence to our racism — its economic imperatives primary among them. But the unmoneyed white guys with the lame-brained ideologies and major ordinance are not the same as the men and women in suits who have decided year after year, decade after decade, to skew the system, to evade or neglect to enforce school and housing desegregation laws, to use the penal code as the new chains of slavery, to turn the police into paramilitaries. The one group is a product of the other, the one feeds off the other, but they are not the same. (Go out with a perfectly nice real estate agent somewhere, anywhere in America where black and white live in some proximity to each other, and listen to her or him talk about the “good” schools and the necessity of living where one’s children will attend them. Real money rides on these completely unnecessary and criminal distinctions. Do you dare to contradict her?) Our cynicism and resignation regarding these matters are a form of evil and every day that evil corrupts us.

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

June 24, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: A Lot at a Time

Okay, this one is the opposite of last week’s Bad Advice, “A Little at a Time,” in which I suggested celebrating incremental writing, since that’s mostly what we get time for. “We” being we humans… But let’s say you’ve got a novel started, or other book (or really any project humans get involved in, though hold off on the mass killings, please)… At some point, it’s going to be time to blast out a rough draft. So accrete as you will, but when you’re well in, I suggest a draft vacation.

It’s no vacation, that’s for sure. But what you do is steal two weeks or one or whatever you can from your life and family, go stay in that pal’s cabin or in the worst motel ever (no TV, for example, and people moaning nonsexually in the next room), and finish a draft of your book. This can be rough beyond rough–the idea is to get a draft out there to work on when the blocks of time are small. It’s not a draft to show anyone, but a true rough draft. Later for first drafts and show drafts–this is the pile of lumber from which you’re going to build your castle.

So. You know your character is going to marry Mary and kill his father and go on the run and thereby lose Mary but meet Eleanor, who will later befriend Mary and bring together a rapprochement between your protagonist and his beloved wife, leaving Eleanor, um, where?

You can answer that question in your motel room two weeks from now. But answer it you must, even if it’s to be changed later. You wake, you fight off depression, you work till lunch, you eat take out, you nap, you drink coffee, you write until an unusually late dinner, maybe dinner out for a brain break, then home to the Blueberry Motel and write some more unto sleep. But stay up till all hours–nothing normal. Sleep till you wake, and start again. Write and write and write some more. Leave your phone in your car till dinner time. Then leave it there again. Masturbate frequently, but only when your work inspires it (and not till you’re sore!).

Phone calls at dinner. I already said that. But don’t talk about the work. And don’t talk to people who occupy too much brain space after. You’ve already apologized to them before you left, no worries. If they don’t understand, dump them forever.

And work. And work.

If you finish early, good. Go back to the beginning and fix all the messes you’ve inevitably left. Because one of the features of desperate drafting is sentences like this: “Here, Eleanor refuses to accompany him to Detroit because she knows his parents are destructive. And so he thinks twice. Dramatize.”

You should leave a day or two at the end to go to like the St. Regis in New York and not write but luxuriate in having done so: massages, fine meals, all the things that monks don’t do.

And then go home and back to the incremental art life.

Bill Roorbach gives advice he himself could never follow, and yet he means it, and hopes you listen. He lives in Maine among trees and chickens.

June 17, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: A Little at a Time

A few years back–can we do it again? Yes.

Every year it’s the same–I look out over my garden and wonder how on earth I’m going to get it ready and then planted in time to have any chance of food from it at all. And every year, an hour here and five minutes there, a morning next week and an hour last week, the thing gets done. And all the other things. Including, like, parenting. And novels.

If a novel’s not a garden, I don’t know what is, except a garden of course, which is a novel of a different kind, the same old story. A novel has to be tended, a novel proceeds from all the years of gardening that came before, writing being gardening. The best thing being that stuff grows even when you’re not looking, and even because you’re not looking.

People like to say to me, well, I’m going to write a novel one of these days. Or a book. Or screenplay. And I always reply, start it right now. Take five minutes after you leave this conversation, and just start. And then tomorrow, take five more. This, you can do no matter how busy. This, you can do even in the midst of your own wedding, or in the midst of a family illness and subsequent funeral, or in in the midst of your pummeling career, whatever your career might be, and no matter how trying, how time-consuming. Emergency-room doctors write novels, for heaven’s sake. They put in a half hour today, five minutes tomorrow, that’s how, finding the gaps between disasters.

Waiting for that big unbroken block of time just means waiting forever. Finding five minutes means you can get going today. In fact, I just wrote this post in several five-minute excursions in the interstices between a hike, making a script deadline, making lunch for my daughter, and cleaning the house before the housekeeper arrives (if you know what I mean).

Later, while the girl’s at her piano lesson, I’ll sit in the car on this very laptop and turn back to my novel in progress, hundreds of pages now, written at all times of day, in every form of transportation, in dozens of houses and hotels, but also at my desk. My desk, my desk, how I miss thee! When I get back there, finally, and because I’ve been working incrementally, I’ll know just what to do, and that unbroken block of time won’t become an unbroken block of despair.

See you in five!

Bill Roorbach is a walker in the woods, a noticer, and an amateur short-order cook, among other things.

June 15, 2015

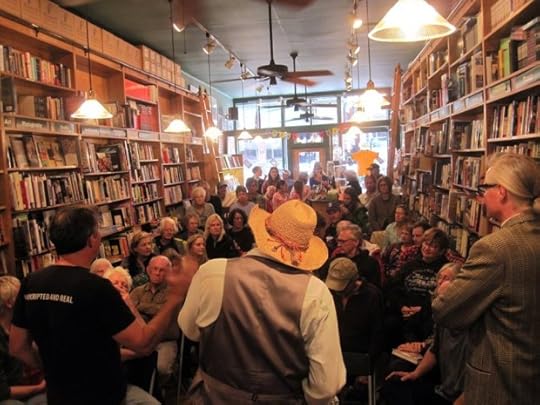

A Reading with Ed and Wally

Been a packed month of readings–one almost every other day. The most recent was a great event at Between the Covers in Telluride with Ed and Wally in the flesh. Thanks Daiva Chesonis. And special thanks to Terry Tice as Ed and Ashley Boling as Wallace Stegner. Next up is the Bookworm in Edwards, Colorado on Thursday the 18th.

June 14, 2015

June 9, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “H is for Hawk,” by Helen Macdonald

Helen Macdonald

Living with a bird is an education. I recently heard an ornithologist point out that, regardless of how long a bird has been a member of your household, that bird will always remain a wild animal. I was reminded of this one Sunday last winter when our morning coffee was interrupted by a wild cacophony of screams and shrieks from Ruby’s cage in the kitchen (Ruby is an umbrella cockatoo that we adopted years ago); rushing out we were astonished to come face to face with a hawk, perched on the railing of our deck peering in at Ruby. The hawk was magnificent–breathtakingly majestic and with both talons firmly planted in a world of unfettered wildness far beyond our limited and merely human comprehension.

All this is by way of introducing H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald. The book is a memoir, sort of.. a memoir of bereavement, natural history, the personal travails of the author, but mostly it is a paean of wonderment and praise to the pure and unsullied wildness of a goshawk that author Macdonald decides to ‘train.’ Partly her gesture is an attempt to deal with the sudden and crippling loss of her beloved father, partly it is the continuation of her lifelong fascination with raptors. Along the way MacDonald, an academic by trade, enlarges her story by sharing the parallel tale of T. H. White’s calamitous attempts to similarly ‘train‘ a hawk as recounted in his early work, The Goshawk.

All this is by way of introducing H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald. The book is a memoir, sort of.. a memoir of bereavement, natural history, the personal travails of the author, but mostly it is a paean of wonderment and praise to the pure and unsullied wildness of a goshawk that author Macdonald decides to ‘train.’ Partly her gesture is an attempt to deal with the sudden and crippling loss of her beloved father, partly it is the continuation of her lifelong fascination with raptors. Along the way MacDonald, an academic by trade, enlarges her story by sharing the parallel tale of T. H. White’s calamitous attempts to similarly ‘train‘ a hawk as recounted in his early work, The Goshawk.

Goshawks are notoriously difficult to train, the most unrelentingly wild of the raptors. H is for Hawk slowly develops into a narrative of the relationship between the ferocious wildness of Mabel, Macdonald’s goshawk, and the author’s own stop and start attempts to tame the wildness of the grief over her father’s death that threatens to consume her. The dance that ensues is both literarily unique and spellbinding. The matter of whom is truly controlling the ‘training‘ remains very much in doubt and the author’s descriptive ability allows the reader to brush up against the wildness that is both at the heart of the natural world and an undeniable element of those dark corners of the human psyche where we most often choose not to go. Here’s a sample, Macdonald describing a hawk: “She was smokier and darker and much, much bigger, and instead of twittering, she wailed; great, awful gouts of sound… the sound was unbearable… and it was all I could do to breathe.”

Reviewers have been rapturous in their praise: “Breathtaking… an indelible impression of a raptor’s fierce essence…” “a soaring wonder of a book…” and “One part memoir, one part gorgeous evocation of the natural world, and one part literary evocation.” You will never look up into the sky with the same perspective after meeting Mabel and if you are like me, you will be consumed with the notion of ‘training‘ a hawk of one’s own.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

June 6, 2015

A Talk with Jack Loeffler (And Another Talk this Coming Wednesday)

Next Wednesday night I’ll be at Collected Works in Santa Fe at 6pm. It’s a long drive so we are starting tomorrow (Sunday) morning so we get there on time!

Next Wednesday night I’ll be at Collected Works in Santa Fe at 6pm. It’s a long drive so we are starting tomorrow (Sunday) morning so we get there on time!

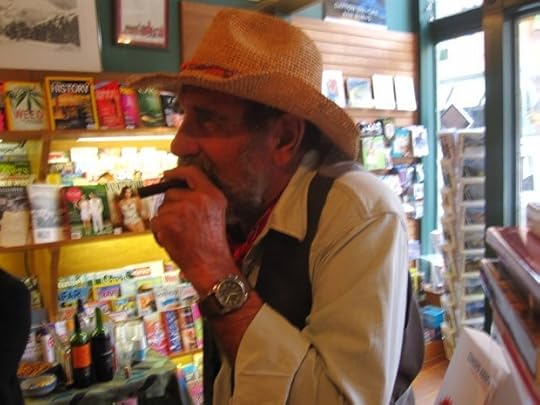

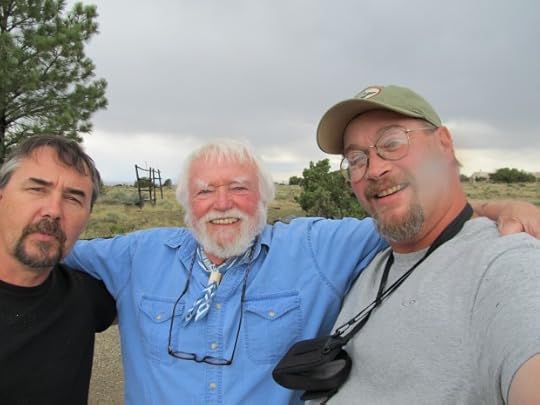

I will be introduced by, and in conversation with, Jack Loeffler, one of Edward Abbey’s closest friends. Loeffler lives in the hills outside of Santa Fe,and when I was traveling for the book my friend Mark Honerkamp and I dropped by and spoke with Loeffler in the open, book-filled study of his single-story adobe home. (These are the pictures Mark took while we spoke.)

“What Ed and I knew, on some fundamental level, is that once you’ve been out in it long enough, it becomes the top priority,” he told us as we settled into the study. “When you’re out in it fully, you recognize it’s where you belong. We concluded that it took a good ten days in the wilderness. Until you began to change. You need to live in the spirit of nature, so that it’s totally and intuitively in your system. Then you don’t have any choice but to defend it.”

A handsome, fit 74 year old man with a big smile and white beard, Loeffler was innately theatrical. He wore an open Western shirt, kerchief and khaki shorts. His whole demeanor was what I can only describe as oddly joyful.

“Ed was a tortured man,” he told us at one point. “He was no stranger to despair.”

“Ed was a tortured man,” he told us at one point. “He was no stranger to despair.”

That jibed with what I had read and thought. Though Loeffller spoke those melancholic words with a beaming smile.

“I think that is one of the reasons we got along so well,” he continued. “I am a stranger to despair.”

He exploded in a wild burst of a laugh after he said this, a noise we would grow used to by the end of the interview. I can only describe it as being like the upward yodeling of a pileated woodpecker.

I agreed that he seemed to be a sunnier spirit than his friend.

“I’m a happy dude, man,” he said.

I confessed to him that I was feeling guilty about all the driving I had been doing.

“Ed and I drove all over the Southwest,” he said. “And worse we took both of our trucks. I don’t think we had a single trip when we didn’t get stuck. As a matter of fact we even got stuck when he was dead. We had made a vow to each other that whoever went first, the other wouldn’t let them die in a hospital bed. Ed died well but when I went to bury him in the desert, with his body in the back of the truck, we got stuck in the sand. It was inevitable, I guess.”

Dead bodies in the back of the truck were just one way that their camping trips were not like yours or mine. I mentioned this.

“Not only did we take two vehicles much of the time we camped, but we always brought matching .357 Magnums. So we were ready.”

“For what?” I asked.

“Well, I have to be careful here. For Ed the statute of limitations has run out. Not necessarily for me. Let’s just say that one of the reasons we had them—not that I would really use it for this—is that ostensibly a .357 can crack an engine block in a big piece of machinery.”

This was what I wanted to know. How much of Abbey’s monkeywrenching was real, how much legend or fiction? Was he just good with words or did he get his hands dirty?

“Ed did his night work,” Loeffler told me. “It started with cutting down billboards in college. What you’ve got to understand is that rebellion was part of him, in his blood. Look, his father, Paul Revere Abbey, named one of Ed’s brothers William Tell Abbey. Paul had met Eugene Debbs who was a huge influence on him. From his father’s side Ed got that strong, individualistic point of view.”

What became clear to me, as Loeffler kept talking, was that Ed Abbey did a lot more than pay lip service to monkeywrenching. Loefller described the early fights of the Black Mesa Defense Fund and the battles against the Peabody Coal Company.

“We had a rule of three,” he said. They did their work in small groups, preferably two but three at most, and never confided in anyone else about that they’d done.

Both men had come to believe that American culture was “lodged completely in an economically dominated paradigm” and that those who opposed it would be punished.

“Law is created to define and defend the economic system,” Loffler said. But fighting was a moral imperative the two friends came to agree: as obvious a case of self-defense as repelling someone who has broken into your home. That said, they would only push it so far. Abbey and Loefller made vows of nonviolence. Doing harm to machines was one thing, human beings another.

Loeffler believed that too many people underplayed his friend’s belief in anarchy, which Abbey called “democracy taken seriously.” (FN: 26 One Life at as Time Please) Government, any government, should be rightly feared: “Like a bulldozer, government serves the caprice of any man or group who succeeds in seizing the controls” (27) For this reason Abbey was adamantly opposed to any control of guns. (One wonders if recent events might have led to a softening of this position, though softening, as a rule, was not in Abbey’s nature.)

And there is something else in Abbey that Jack Loefller was suggesting we not take lightly. Abbey fought the prevailing power, but he also knew why most people didn’t fight the prevailing power. Comfort was a large part of it. For most of us there is a lot to lose. It was, and is, Abbey’s job to make us feel uncomfortable in our comfort. He wrote: “Never before in history have slaves been so well fed, thoroughly medicated, lavishly entertained—but we are slaves nonetheless.” And this was even before they gave us slaves our cell phones and computers.

Right before we were ready to say goodbye, a huge crack of thunder got us jumping out of our seats. The rain pounded on the roof, a significant percentage of the rain that Santa Fe would see that year. When it stopped, Jack walked us out to the car. We hugged goodbye, which seemed in no way unnatural.

There was something a little groovy about Jack Loeffler, the kind of grooviness that usually sets my bullshit detector off. But the detector stayed quiet during our visit. If his book had been slightly tone deaf, Jack Loeffler in person was anything but. I was both charmed and impressed by the man. He was a force: voluble, smart, dynamic.

We left reluctantly and when we finally did, after knowing him for three hours, we felt we were leaving a friend.

The last thing he said to me was a directive regarding his own friend, Edward Abbey.

“Bring him alive,” he said as we climbed in the car. “Farewell!”

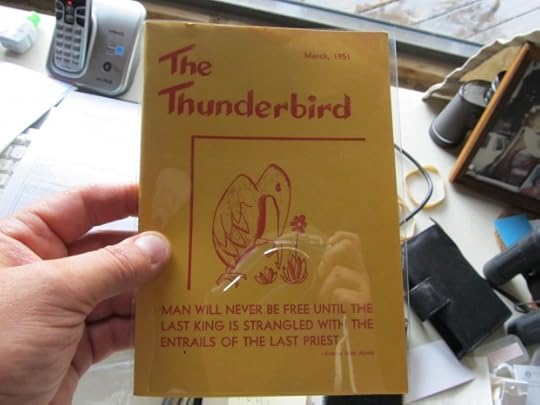

The University of New Mexico magazine Abbey edited.

Old Guys’ Selfie

June 2, 2015

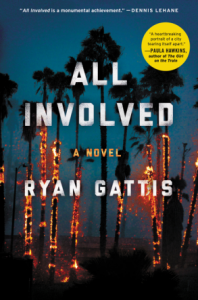

Lundgren’s Lounge: “All Involved,” by Ryan Gattis

All Involved, despite its rather pedestrian title, is an astonishing work of fiction chronicling the events around and in Los Angeles in the six days following the Rodney King verdict. Over two decades after the riots that ensued following the acquittal of the three white LAPD officers, author Ryan Gattis offers up a riveting, nuanced, multi-perspective account of the six days of rage. In the aftermath of recent civil unrest in Ferguson, MO and Baltimore and the inevitable question (raised by mostly white pundits and talking heads), regarding why “these people” would destroy their own neighborhoods as a form of protest, Gattis provides some possible insights… regardless of whether or not it’s what we want to hear.

As the riots began most people hunkered down in their homes, waiting to see what would happen. But gradually the total state of anarchy that prevailed on the streets began to present itself as an opportunity to the gangs whose activities were normally kept in check by the presence of the police. Gattis does not glorify the gangs or their actions: rather he offers a quasi-documentary feel to their thinking and their subsequent reactions. The charismatic leader of one gang, Big Fate, reflects as he watches the news:

As the riots began most people hunkered down in their homes, waiting to see what would happen. But gradually the total state of anarchy that prevailed on the streets began to present itself as an opportunity to the gangs whose activities were normally kept in check by the presence of the police. Gattis does not glorify the gangs or their actions: rather he offers a quasi-documentary feel to their thinking and their subsequent reactions. The charismatic leader of one gang, Big Fate, reflects as he watches the news:

“The news switches to a camera on a helicopter, and the sky–man, the sky isn’t even blue or that halfway kind of gray we get on the worst smog days. It looks like wet concrete. A gray so dark it’s almost black. It looks heavy as fuck.

That’s when it hits me I’m staring at a war zone. In South Central…

And this whole entire scene says to me… now’s your fucking day, homie. Felicidades, you won the lottery! Go out there and get wild, it says. Come and take what you can… If you’re bad enough, if you’re strong enough, come out and take it… Cuz the world’s completely flipped, up’s down, down’s up, and badges don’t mean shit…”

Many of the interwoven vignettes are told from the perspective of various gang members. And while Gattis does not shy away from depicting the violent ethos that rules gang culture, he also makes it clear that for many, many members, the gangs are a refuge from the dysfunction that inevitably results from institutionalized racism, poverty and socially-sanctioned police brutality. Most notable among the narrators is Lupe, A.K.A. as Payasa, a 15 year old girl for whom the gang is the only family she knows. Lupe’s brother, Ernesto, a true innocent, is savagely tortured and killed in the novel’s opening scene as retaliation for another brother’s transgressions. But the gang code of honor deems outsiders, like Ernesto, to be off limits, and this violation of that code unleashes a series of escalating reprisals and counterattacks that occur in a wild world ruled solely by the ancient sentiment that “might makes right.”

Most impressive of Gattis’ writing is the verisimilitude and air of authenticity that suffuses the sixteen stories that propel the novel forward. Gattis, quite dispassionately and painstakingly offers a perspective that can help outsiders comprehend the rage that erupts after an event like the Rodney King verdict or the murder of Freddie Gray and the subsequent burning down of neighborhoods. Once you open the first pages and begin reading, you will be transfixed and transported and perhaps a bit more knowing after you turn the final page.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]